27Bismillah bird (morgh-e bismillah)

Iran, ca. 1955 Calligraphy by Ahmad Najafi Zanjani (1908–82), dated Rabiʿ al-Awwal 1372/December 1952 Engraving on paper, in a wood frame 7 1/2 × 8 11/16 in. (19 × 22 cm) Wereldmuseum, Amsterdam, TM-4136-11 Photograph courtesy of the museum

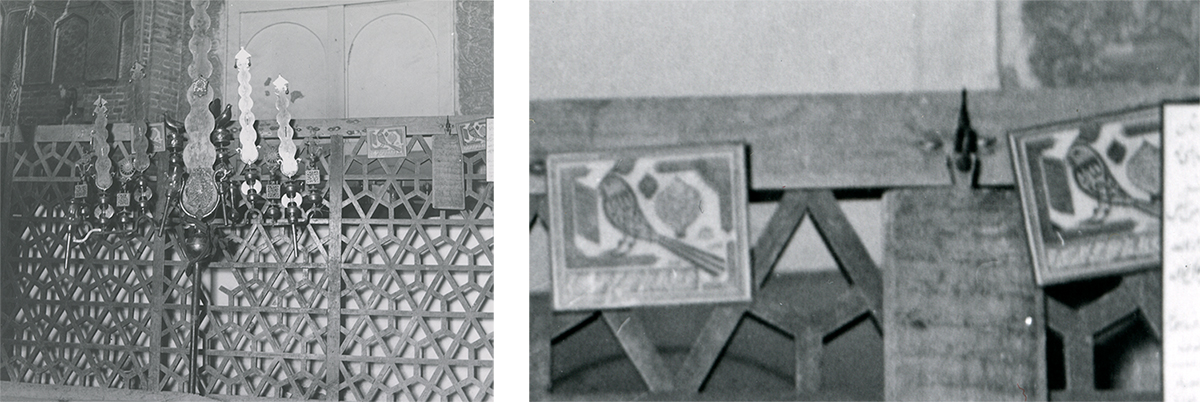

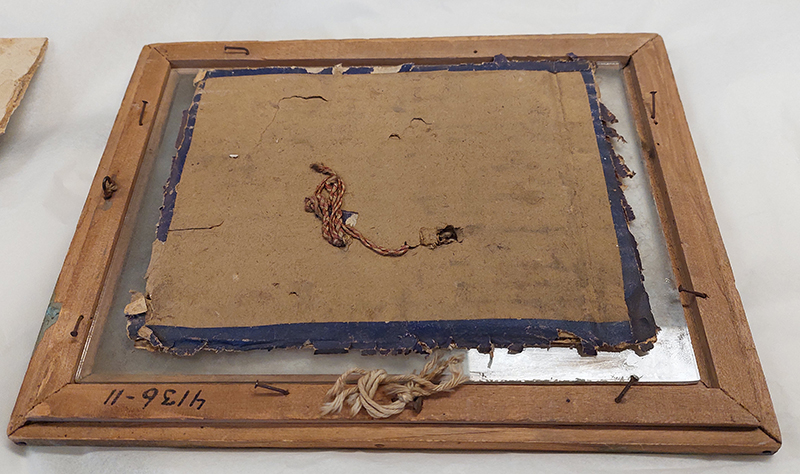

A photograph taken in 1958 inside the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya shows three copies of a bird print suspended to the wood screen in front of the mihrab void (fig. 1; see Overton 2024 [fig. 12], Photo Timeline and Ritual Objects). This similar print in the Wereldmuseum also used to be suspended, as can be seen from the cardboard it is mounted on and the string attached through a hole at the back (fig. 2).

The machine-printed engraving depicts a calligram blending the shape of a hoopoe bird and the words of the basmala (bi-smillahi r-rahmani r-rahimi, or In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful), one of the most important phrases in Islam. From the Persian inscriptions around the bird’s tail, we know that the calligraphy was designed in Tehran in Rabiʿ al-Awwal 1372/December 1952 by the master calligrapher and Shiʿi scholar Ahmad Najafi Zanjani (1908–82) and reworked for printing by the engraving company (gravursazi) Omid (fig. 3). There is no date given for the printing process.

The bird is surrounded by various Arabic texts in frames, written in naskh script, which affirm the Shiʿi nature of the image. Another recurrent theme is protecting the reader from harm. For example, inside the rectangular frame touching the bird’s beak is chapter 114 (surah al-Nas) from the Qur’an, one of the muʿawwidhatayn, the two surahs that are known for offering protection. The large onion-shaped frame on the left contains a hadith, a saying of Prophet Mohammad: “God has said: ‘The friendship of ʿAli ibn Abi Talib is my fortress. The one who enters my fortress is safe from my wrath.’” This hadith is known as the hadith of the golden chain (al-silsilah al-dhahab) and is important to Twelver Shiʿism because it affirms the status of Emam ʿAli. The smaller onion shape to the left of the bird and the text along the right edge are blessings to Prophet Mohammad and his family members.

During the Qajar period (1789–1925), Shiʿi themes previously available only to the elite became available in large print runs, and this continued into the twentieth century. Printed images were popular because they were cheaper to produce than handwritten calligraphy while retaining much of the sophistication of calligraphy. Initially, the images were produced using lithography, but this was replaced by other printing techniques in the middle of the twentieth century (Marzolph 2009). Prints with pious depictions, like this one, were sold in the bazaar and near Shiʿi mosques and sanctuaries and occupied a significant place between Persian miniature art and more popular art forms, such as reverse glass paintings and coffeehouse paintings.

Sources:

- Marzolph, Ulrich. “Lithography iv. Lithographed Illustrations.” Encyclopædia Iranica, August 15, 2009, https://iranicaonline.org/articles/lithography-iv-lithographed-illustrations-.

- Overton, Keelan. “Jane Dieulafoy in Varamin: The Emamzadeh Yahya through a Nineteenth-Century Lens.” Getty Research Journal 19 (2024): 57–91. [Getty]

Citation: Pooyan Tamimi Arab and Mirjam Shatanawi, “Bismillah bird (morgh-e bismillah).” Catalog entry in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.