Introduction to the Emamzadeh Yahya Project and Online Exhibition

Keelan Overtonترجمه فارسی

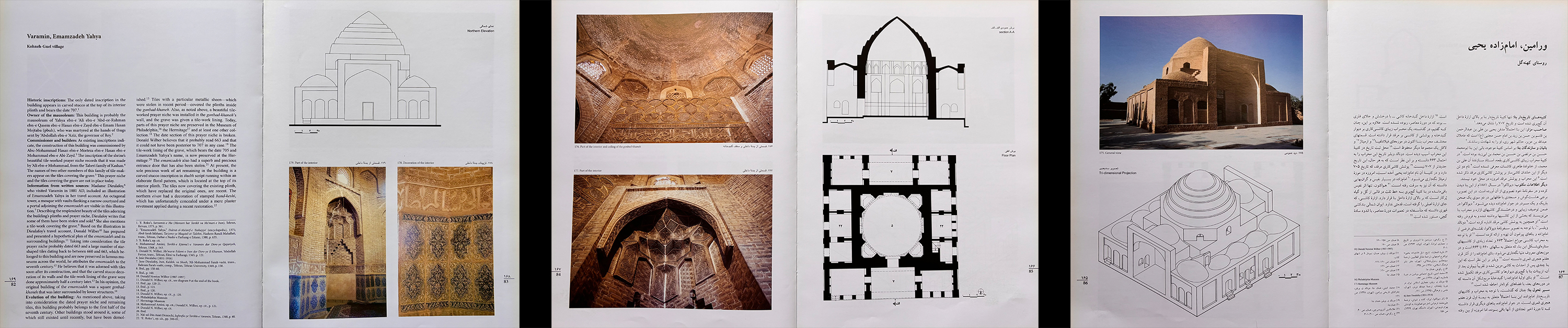

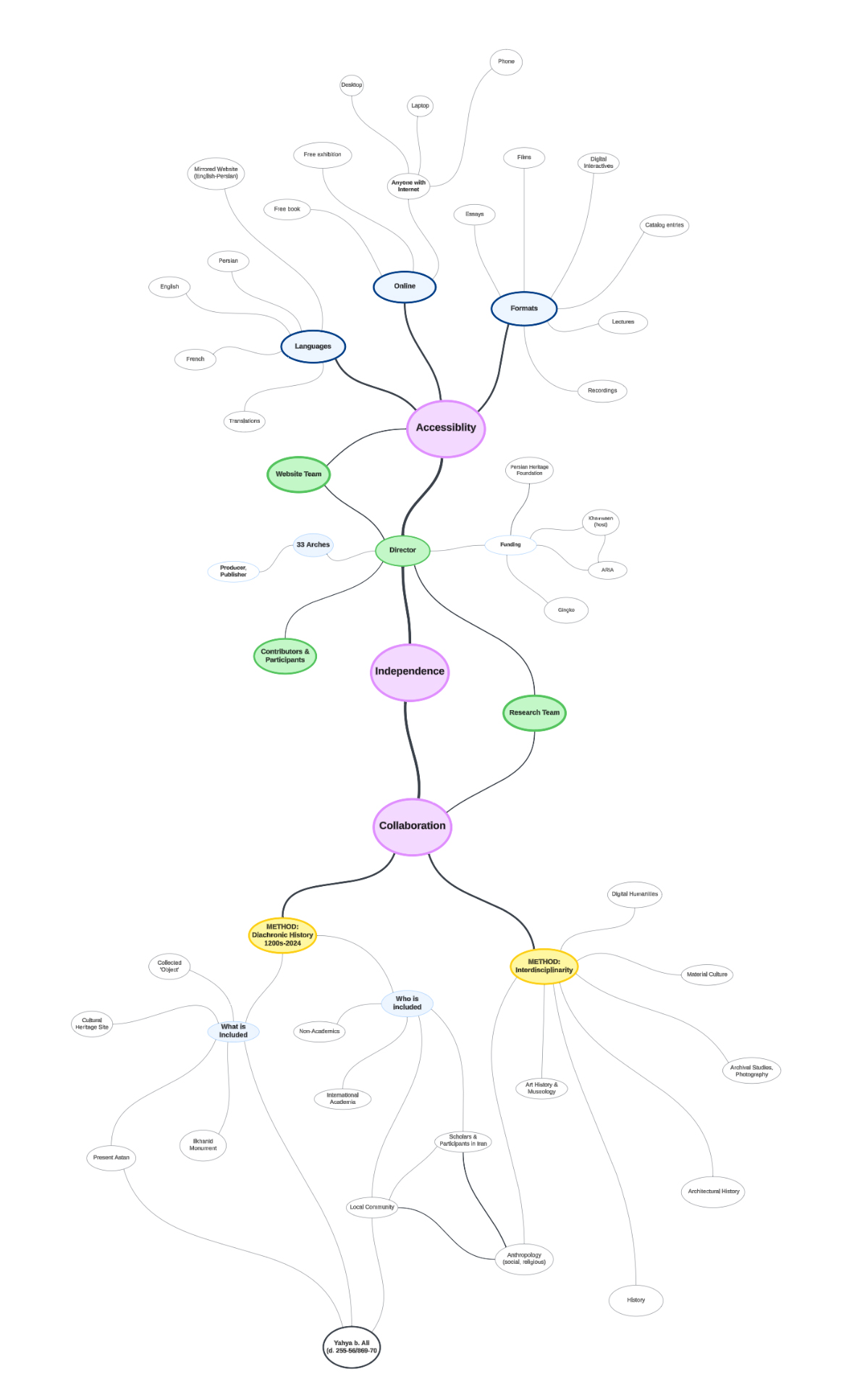

The first questions that many people ask about this project are: Why did you do this as a website, why have you framed this as an online exhibition, and why the Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin of all sites (fig. 1)? The last question will likely be answered with a quick click around the website and realization of the amount of scholarship that the shrine has inspired. The former two are more complex, and I provide some answers here. Since it can be difficult to articulate the many layers and complexities of this large project, I pair this text with two additional tools. The first is a visual diagram of the project centering on its three key values: independence, collaboration, and accessibility (jump ahead to fig. 4). The second is a brief curator’s walk-through of the website, which is an online exhibition, exhibition catalog, and academic edited volume in one (coming soon).

Missions and Methods

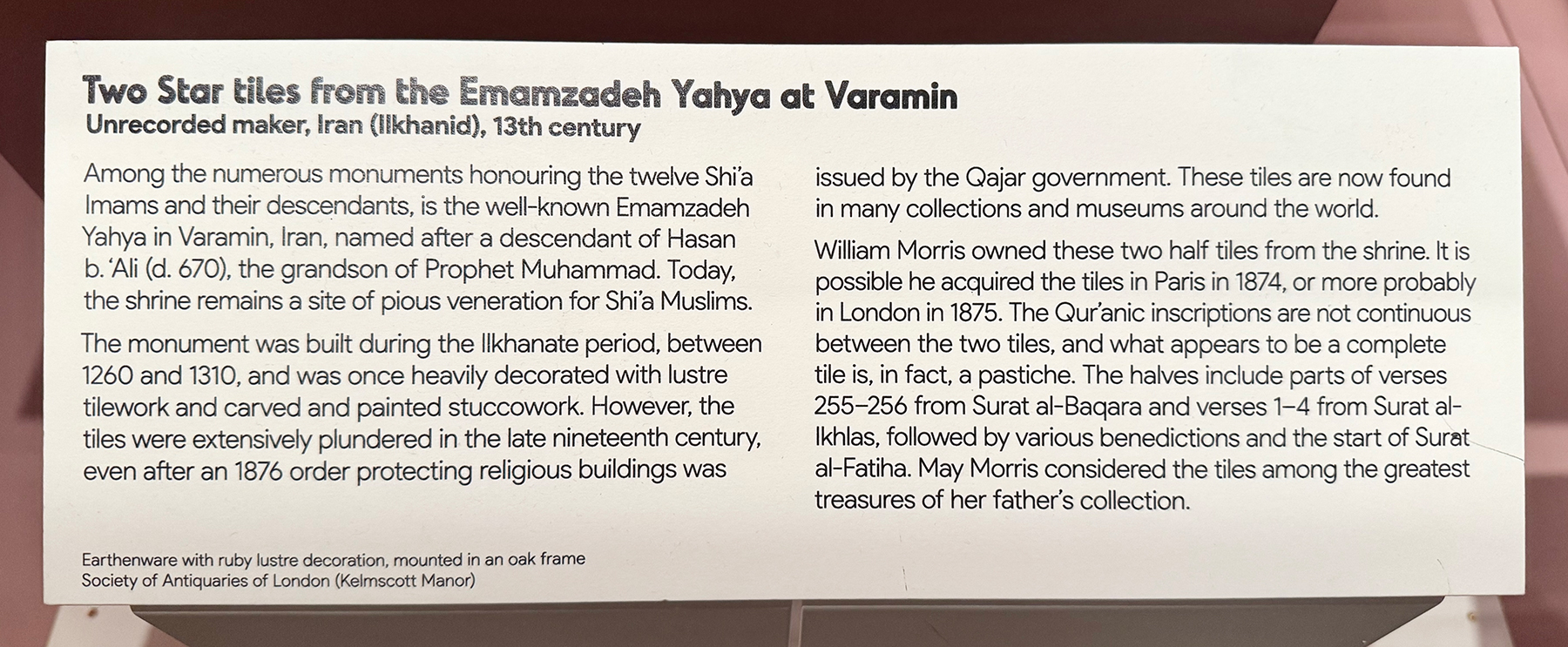

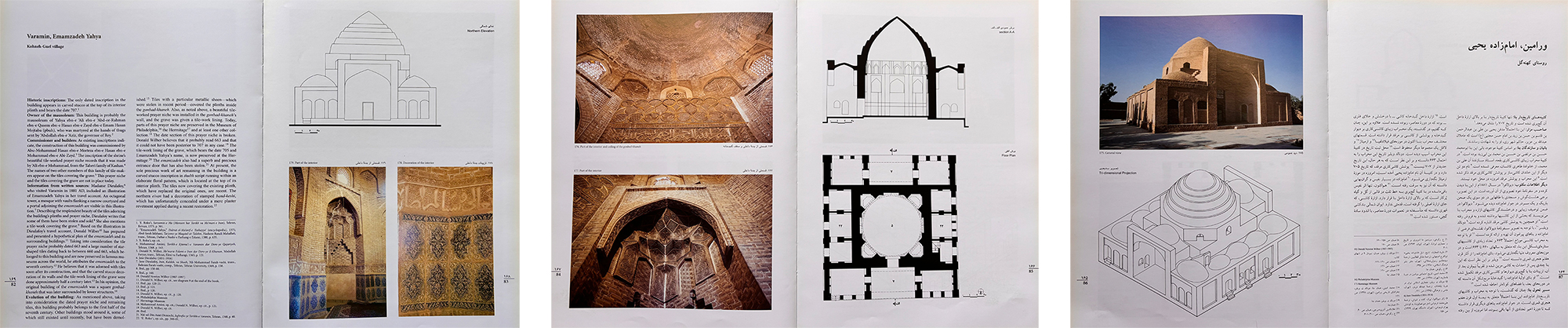

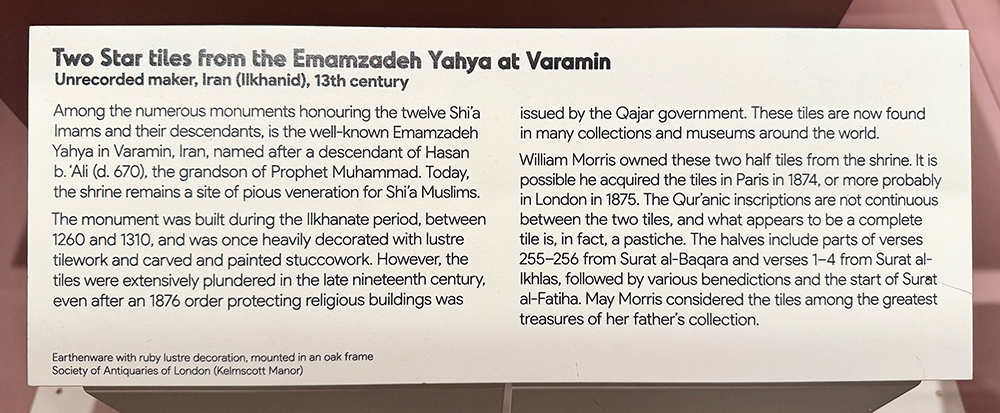

The Emamzadeh Yahya is a relatively well-known shrine complex in the history of Persian art. It appears in such encyclopedic architectural compilations as Archnet, the Ganjnameh, and Iranarchpedia, and its luster tiles are displayed in around fifty museums worldwide (fig. 2). Despite this degree of familiarity, the shrine is not necessarily a staple of the Iranian architecture and art history curricula, and museum displays of its tiles generally offer little information about the site and some even intimate that it was destroyed.1 Within the field of Islamic art history, the Emamzadeh Yahya is typically studied as a historical monument of the Ilkhanid period (1265–1353) or in relation to the production and collecting of luster ceramics. While these approaches are important and necessary, they neglect to account for the site’s other layers and histories, including its evolution over time, present-day existence, and actual use as a sacred space on many levels.

The mission of this four-year independent project (2021–25) can be divided into two general categories: how we frame the Emamzadeh Yahya and how we present our findings.2 This framing of the Emamzadeh Yahya is rooted in an expansive and fluid approach to time, knowledge, and perception. Instead of categorizing the shrine solely as an Ilkhanid monument (ca. 1260–1307), we adopt the method of diachronic history and explore its continuous history over seven hundred years (1200s–2024). In doing so, we acknowledge its many functions and meanings, depending on the eye of the beholder. While the Emamzadeh Yahya is certainly an important Ilkhanid monument and the source of luster tiles in many museums worldwide, it is first and foremost the burial place of Yahya b. ʿAli (d. 255–56/869–70), a descendant of Emam Hasan (d. 50/670), the second Shiʿi Emam, and also a destination for ziyarat (زیارت, pious visitation), the main community center and cemetery of the Kohneh Gel neighborhood, a cultural heritage site, and a tourist destination (fig. 3).

In order to explore the Emamzadeh Yahya in this holistic way, interdisciplinary collaboration has been essential. Over the last few years, many strands of research have been ongoing between scholars inside and outside Iran, and this website ultimately weaves them all together. The result is that we can begin to appreciate the site through many eyes—the pilgrim, resident, caretaker, anthropologist, curator, conservator, architectural historian, and photographer—and consider its resonance between the academy, museum, community, individual, and cultural heritage organization. Depending on what perspective and point of entrée you choose, chances are you will see the site in a new way. We do not claim to cover all perspectives, and we realize that this website’s users will have diverse sets of interests and knowledge.

The second part of this project’s mission is to share our research in the most accessible ways possible. This scholarship is intended to be used and enjoyed by many, including colleagues in the museum and academia, general publics of all kinds, students and professors across the humanities, heritage professionals, and readers of three languages (English, Persian, and French). The work presented here is a mix of public facing (what you would expect in an exhibition catalog), rigorously academic (what you would read in a Brill or Muqarnas article), and experimental (something you may not have seen before). As such, the website not only offers an alternative for exhibiting and experiencing Persian art and architecture but also publishing it. While this project operates within the academic rigor of the Euromerican system, it also challenges many of its exclusions, biases, and limitations and charts its own course (see Editorial Notes).

Figure 4. Diagram of the Emamzadeh Yahya Project highlighting its three key values through the visual analogy of a tree: independence (trunk), collaboration (roots), and accessibility (fruits). Lucid Chart designed by Keelan Overton, December 2024.

Why a website?

The answer to this question is practical: a website is simply the best way to achieve our two-fold mission of holistic exploration of the Emamzadeh Yahya and accessible sharing of scholarship. From the onset of this project in early 2021, my goal was to counter a fundamental conundrum and disconnect: the majority of people who see the tomb’s luster tiles in museums worldwide will never be able to visit the emamzadeh, and the majority of people who use, visit, and care for the shrine on a regular basis will never be able to see its tiles and archives abroad. This physical gulf has often translated into an intellectual gulf. Many museums have ignored the site in their galleries and collections online, and some have intimated that it is ruined or abandoned.3 In order to counter this problem, I originally included ‘living’ in the title: ‘an online exhibition of a living Iranian shrine.’4 In the opposite direction, many of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s constituents do not have access to the archives required to accurately narrate some of its histories, especially the plunder and collecting of its tiles. That said, someone who lives in Varamin and Kohneh Gel does not need to be told that the site is alive and well. A website was identified as the best path to bridge these seismic gulfs in access and understanding, since it would be theoretically available to anyone with an internet connection.

A website also offered the most dynamic and flexible platform to showcase the star of this show: the Emamzadeh Yahya complex. It is the central argument here that understanding, or at least attempting to understand, the Emamzadeh Yahya rests first and foremost on perceiving the site through diverse frames. In many academic and museological circles, the emamzadeh has suffered from a one-dimensional presentation through a limited number of photographs representing one angle and one moment in time.5 The root cause of this limited visuality is often the print book and its limitations: a certain number of pages and figures, extra costs for color, and often a preference for professional-level images alone.

The multi-media presentation of the Emamzadeh Yahya on this website features over 150 photographs taken over 140 years (1881–2024) as well as films, audio recordings, and digital recreations. In curating the visual contents, I have prioritized including a large number of photographs and videos, some of which might not meet the highest standards of quality; sequential viewing of the site over time; and seeing the complex as a whole and in relation to its surroundings, versus just the domed tomb at the center of the courtyard (vid. 1). An exciting aspect of this presentation is its balancing of the eyes of the architect and architectural historian, often gazing up at inanimate squinches and domes, and that of the anthropologist, often seated firmly on the ground with the shrine’s community (figs. 5–6). Participants in Iran have also helped to animate the complex beyond sight alone, considering taste and sound especially.6

Video 1. Looking at the north façade of the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya and then across the courtyard to the main entrance of the complex. Video by Hamid Abhari, October 2024.

While following the standards of academic print publication, this website packages scholarship in other formats that are both better suited to the material and more effective at bridging the physical and intellectual gaps noted above. Films on the site and neighborhood and city of Varamin offer international audiences a spatial experience that should resolve the problem of ‘Emamzadeh Yahya’ and ‘Varamin’ just being empty words on a label. Concurrently, films in the Louvre, V&A, and Museum of Islamic Art in Doha help make these collections more accessible to audiences in Iran. Eight major features—Architectural Heritage, Photo Album, Photo Timeline, Textual Source, Ritual Objects, Luster Market, Photographers, the Checklist—were built from scratch or created with external softwares to facilitate deeper interaction. In some cases, we have done the work and then asked ourselves, what is the best format to present this? When it came time to create the Persian translation of Sepideh Parsapajouh’s short piece in French about the power of touch, she graciously accepted to read the piece aloud, offering a sort of podcast of her touching observations (pun intended). All essays read like conventional print articles, but many include video and audio (for example, Stucco Inscription, Community, History of Evolution).

Like all scholarship, this one is a product of its time, and our time is defined by its digital nature. Since its inception in 2021, this project has been inspired by a number of digital initiatives devoted to preservation, architectural history, and museological revision, including The Archaeological Gazetteer of Iran, Ghazni, Paris Past and Present, Multaka, Digital Benin, 100 Histories 100 Worlds, Medieval Kāshi Online (focused on Persian luster tiles), and MAVCOR Digital Spaces Project. While the digitalscape has opened many doors and allowed the project to meet its goals of accessibility on many levels, it has also presented its own set of challenges. The open-access nature of the project has also been a double-edged sword and sometimes necessitated the deliberate exclusion of content and visuals (see Sites for example). The sustainability of the website is also a major concern—namely, how to preserve and protect a four-year project that comes with a sizeable price tag and whose physical form might exceed a 400-page book, and that is excluding what could never be put on a page.7 While some would call it a major risk to devote so much time, effort, and expense to a website, we must also remember that physical exhibitions are not always a sure thing.

The COVID-19 pandemic inspired many museums to think twice about the sustainability of physical exhibitions and to develop digital efforts, including digitization and online exhibitions.8 The scale of online exhibitions can vary dramatically from museums putting a sampling of images online to a fully bilingual website (consider the Getty’s Return to Palmyra) to something crafted in Google Arts & Culture (consider this MFA Houston project). The last two projects emerged within each museum and focus on their respective collections, with an attempt to make them more accessible. This online exhibition is likewise committed to accessibility, but because it was created independently, it is not based on or inspired by any institution or collection.

Why an Online Exhibition?

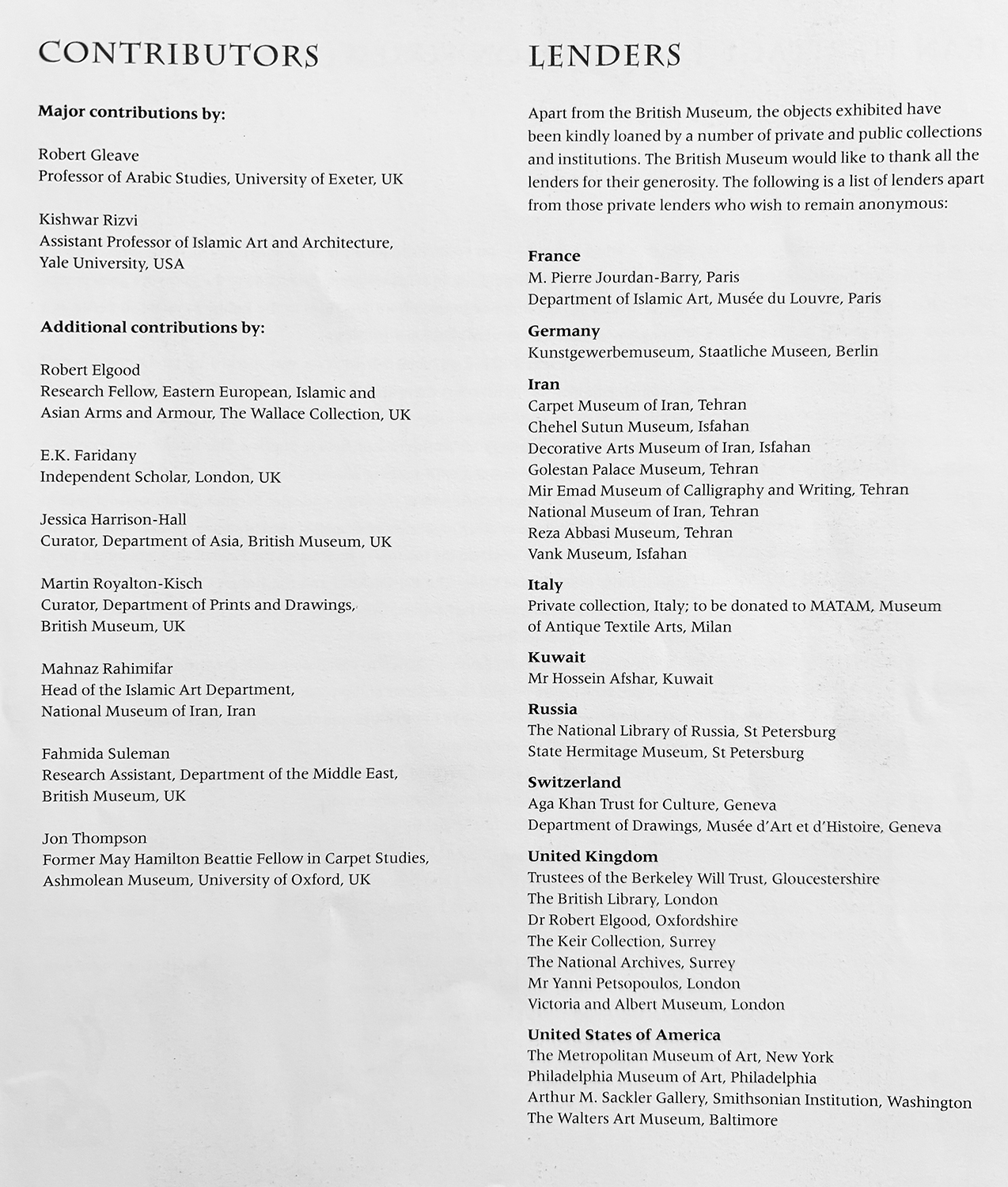

The reason for making this project a website is hopefully clear, but why make it an online exhibition specifically? What explains this museological emphasis? The answer rests in another set of conundrums: only a handful of recent exhibitions of Persian and Islamic art have included loans from Iran, and most recent exhibitions of Persian art outside of Iran are largely inaccessible to people in Iran. The implications of these disconnects are significant on many levels, including which collections shape the field’s narratives and canons and who gets to appreciate the cultural heritage at hand.

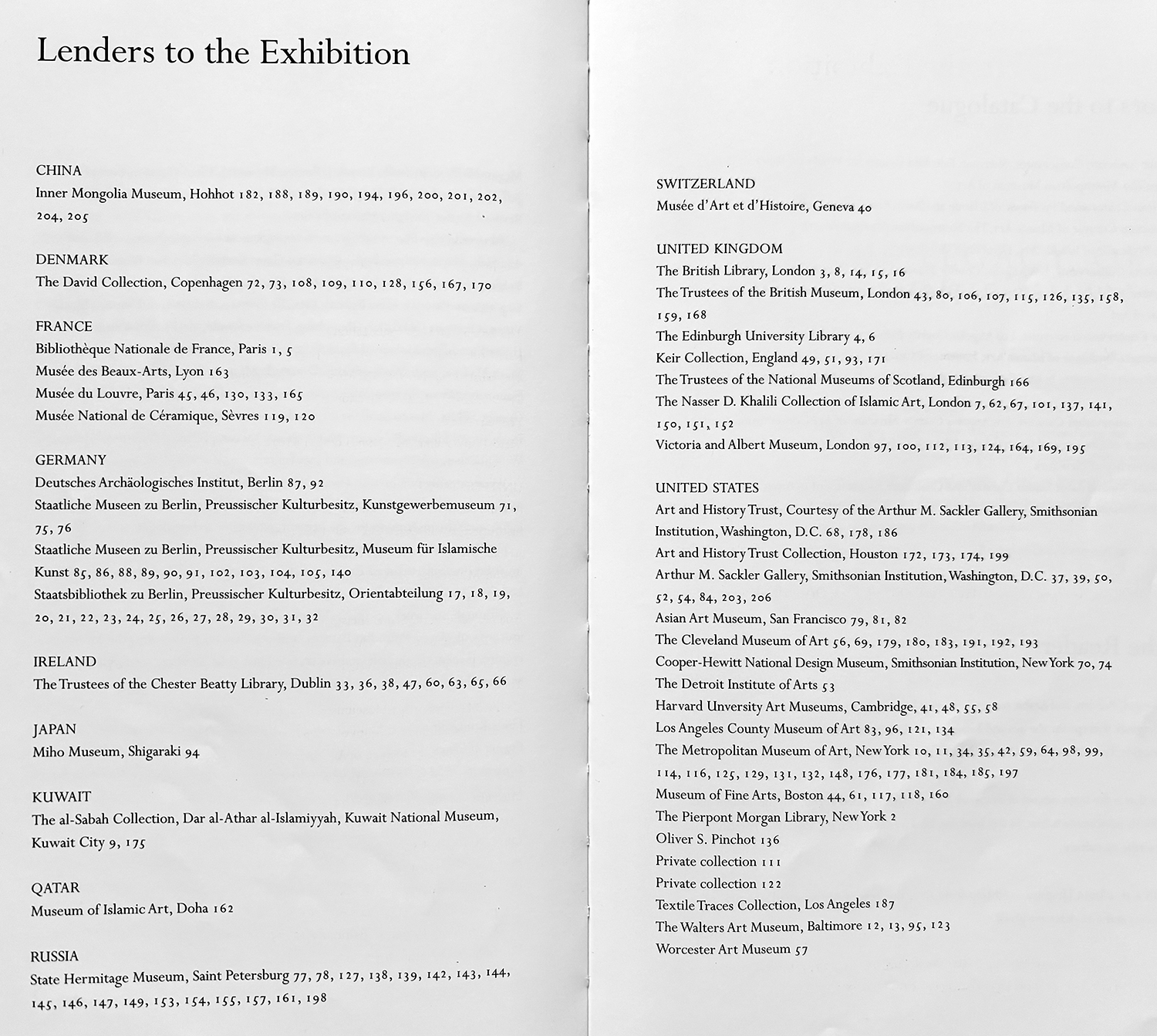

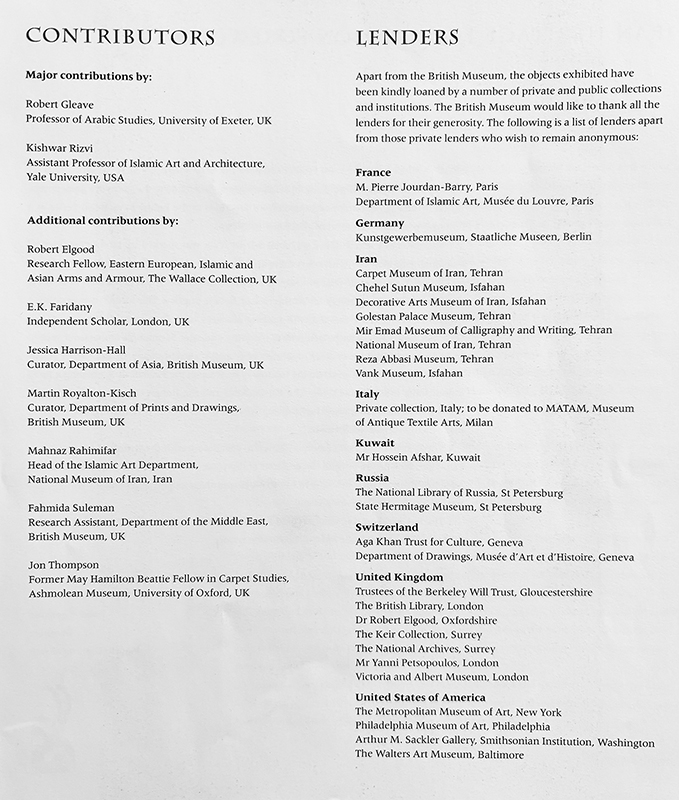

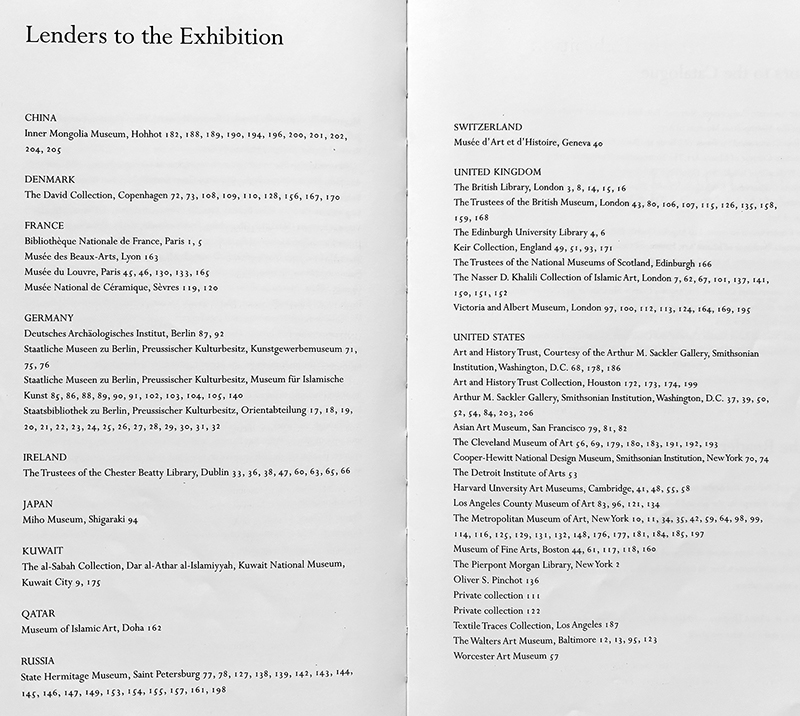

Iran’s isolation in the recent international museumscape has not always been the case. About one hundred years ago, in 1931, Iran lent many objects to the “International Exhibition of Persian Art” held in London. This exhibition showcased over 2,000 works of art, including the Emamzadeh Yahya’s luster mihrab, then in the possession of Hagop Kevorkian (d. 1962) (fig. 7).9 Major international congresses on historical Persian art followed in Leningrad (St. Petersburg) in 1935, New York in 1960, and Shiraz in 1968, and Iran also became a major player in the international contemporary art scene, culminating in the founding of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tehran in 1977.10 With the advent of the Islamic Republic in 1979, the country’s museumscape underwent major shifts, and it became increasingly more absent in the list of lenders found at the start of catalogs.11 Two of the last instances of loans were to the 2009 Shah ʿAbbas exhibition at the British Museum, which included materials from eight Iranian museums, and the 2018 L’Empire des Roses at Louvre-Lens, which borrowed from the National Museum of Iran and Golestan Palace (fig. 8).

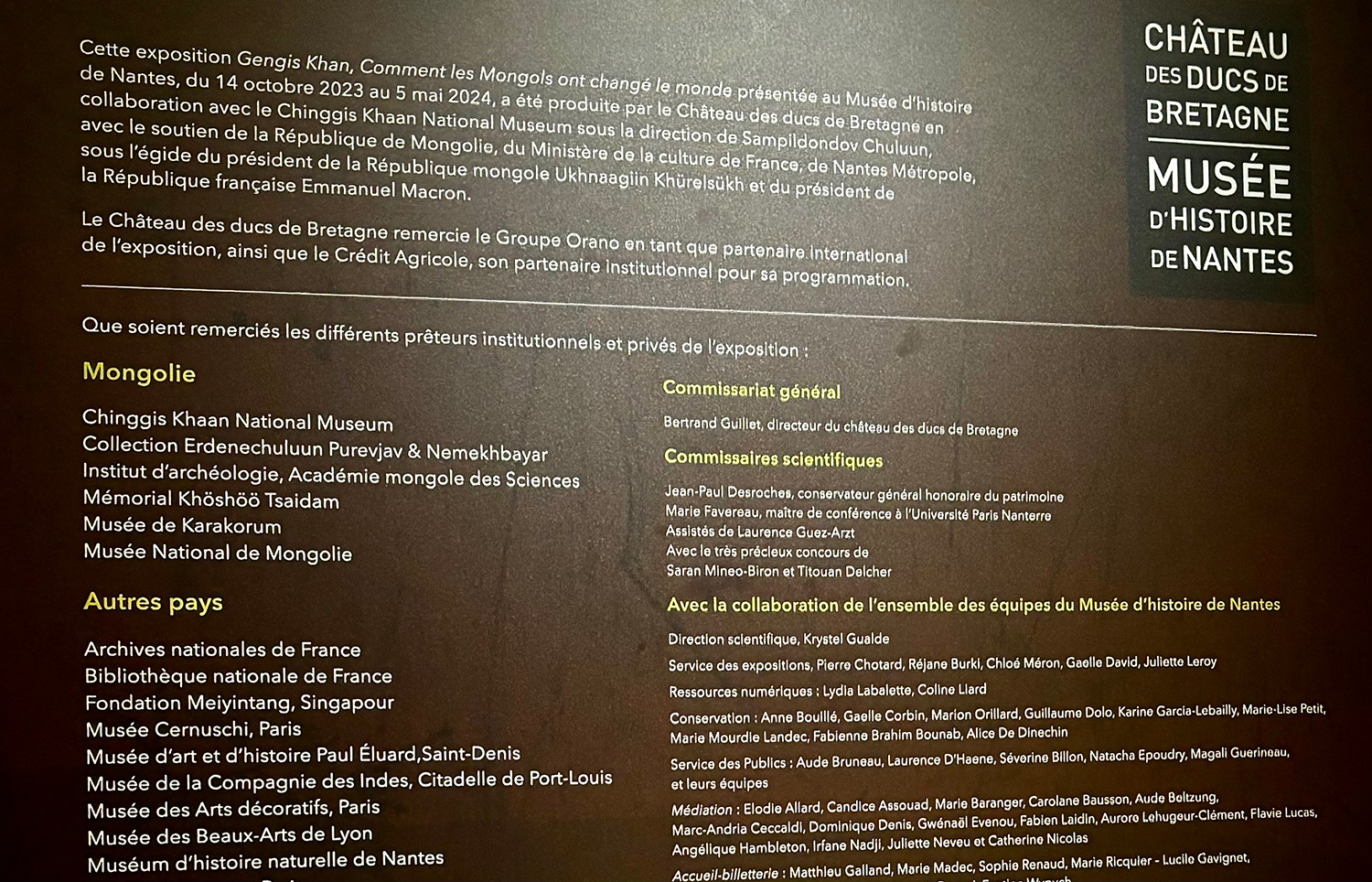

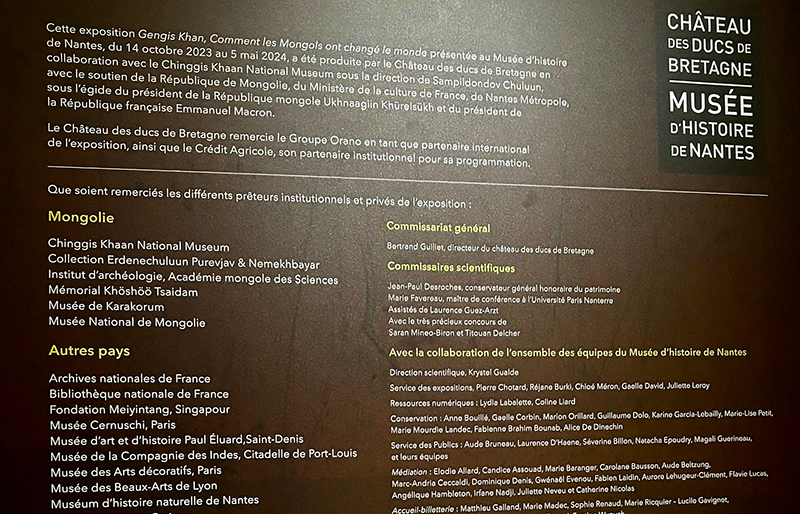

While the international museumscape of Persian and Iranian art faces distinct challenges, we can also observe a general politicization of the broader field of ‘Islamic art.’12 State politics can play a major role in what we see, and do not see, in many museums and exhibitions, especially larger ones. One example is the recent Chinggis Khaan: How Mongols changed the world (2023–24) in Nantes, which reflected a major partnership between the Republics of Mongolia and France and included star and cross tiles attributed to the Emamzadeh Yahya (fig. 9, vid. 2). A comparison of this exhibition’s patrons and frames to those of The Legacy of Genghis Khan (2002–3) in Los Angeles and New York underscores how exhibitions can be significantly shaped by politics (figs. 10–11).13

Video 2. The luster display in the Nantes exhibition. Video by Keelan Overton, May 2024.

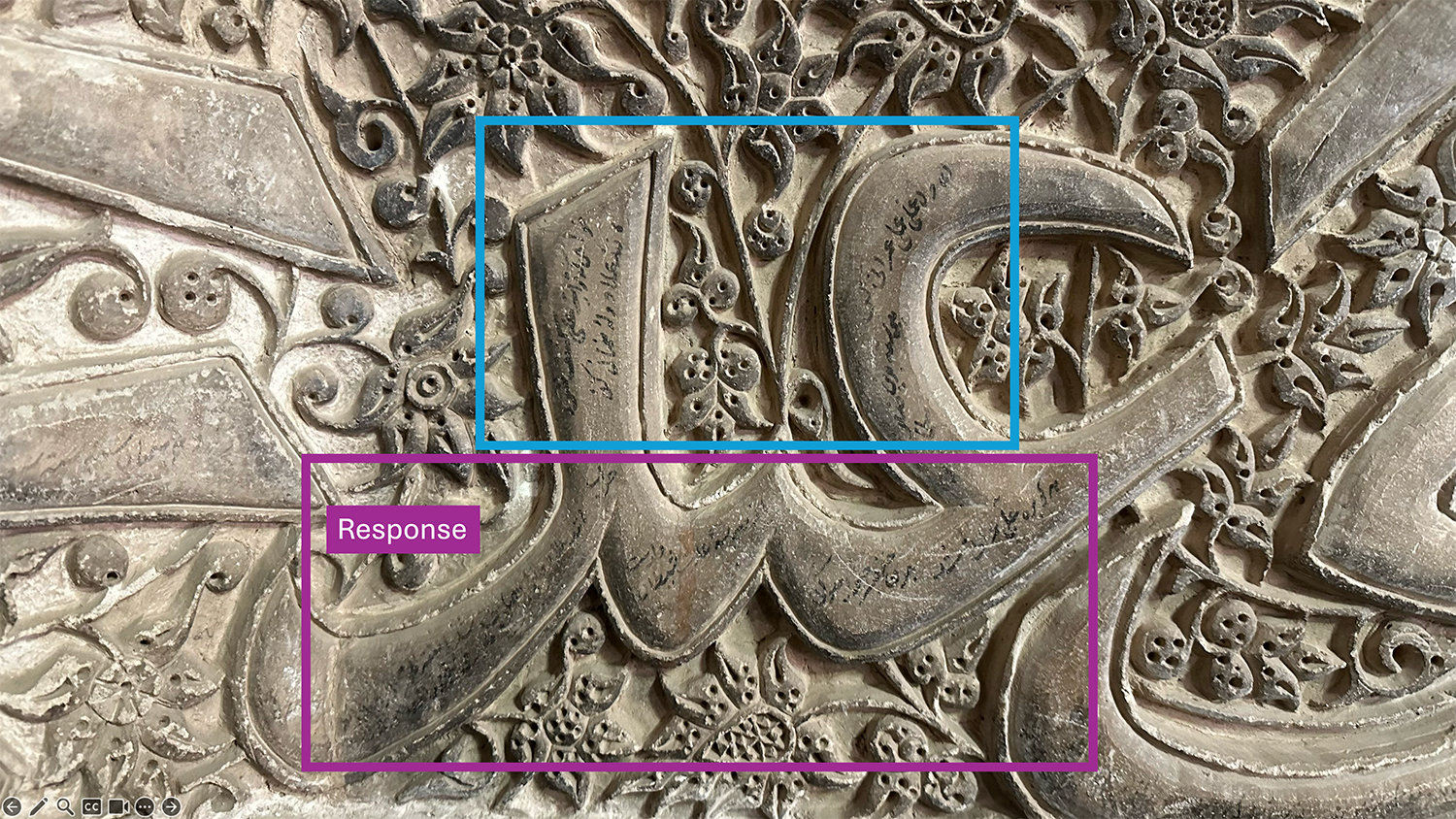

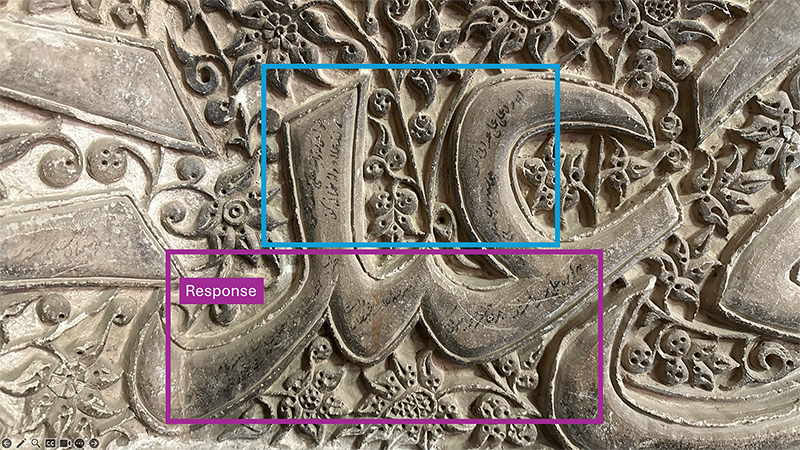

As an independent grassroots project that has attempted to steer clear of various physical, intellectual, and institutional confines, this online exhibition has sought to create an alternative museological space for exhibiting and experiencing Persian art.14 Inspired by a yadegari (یادگاری, inscription memorializing visitation) written in the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya in response (جواب) to one above it, I outline some general patterns in physical exhibitions of Persian and Islamic art and this online exhibition’s response or alternative (fig. 12). These flippings of the script are only possible because of the project’s online format and, in some cases, its independence.

Pattern 1: Most recent exhibitions of Persian art outside of Iran are generally inaccessible to people in Iran. This includes not only the physical exhibition but also the catalog, which cannot be easily ordered online or distributed in Iran.15

Response 1: Create an open-access website theoretically available to anyone with internet. Make the website navigable in Persian (a mirrored website), offer some English and French contributions in Persian translation, and design the website for use on multiple devices (desktop, laptop, phone). Bear in mind and often prioritize audiences in Iran.

Pattern 2: Only a handful of recent exhibitions of Persian and Islamic art outside of Iran have included loans from Iran. The ‘lenders to the exhibition’ are usually a familiar set of institutions and collectors in Europe, Russia, the United States, and sometimes a few countries in the ‘Middle East.’

Response 2: Build a hypothetical checklist that imagines what it would be like to include loans from Iran. How would the selected materials change, and how would this impact the generated scholarship and narratives? Include some museum lenders but widen the typical cast and prioritize the shrines themselves and their materials in situ. Moreover, do not focus on physical things alone but also consider ephemeral experiences and intangible heritage. Build a checklist based first and foremost on the topic at hand, versus who would lend and what could be packed up and put into the white cube.

Pattern 3: Most exhibitions and galleries of Islamic art outside of Iran do not offer substantive information on Twelver Shiʿism, the majority form of Islam practiced in Iran. When Iranian Twelver Shiʿism is considered, the transnational complexes at Mashhad and Qom typically shape the narrative.16

Response 3: Avoid the generalist Islam/Islamic art paradigm altogether and attempt to offer a variety of resources that facilitate an understanding of Twelver Shiʿism as a religious practice and a cultural tradition. In addition to addressing transnational and national patterns, consider some personal, tribal, and local iterations specific to the Emamzadeh Yahya and Varamin.

Pattern 4: Many exhibitions of Persian art outside of Iran are created by what are generally termed ‘fine art’ museums. The result is often a framing of the field through elite patronage and the highest quality of artistic production.17

Response 4: Explore examples of ‘luxury objects’ of the ‘great Islamic courts’ alongside those that illuminate everyday use and the more common ground realities of Iranian emamzadehs. In other words, try to balance the frames of art and architectural history with those of anthropology and ethnology.18

Pattern 5: Most exhibitions of Persian art outside of Iran do not interrogate what is included and why. Notably, they do not consider the provenances and contexts of architectural elements on display and the present realities of their original sites.

Response 5: Offer some detailed information on the collecting histories of some architectural elements turned musealized ‘objects.’19 Concurrently, balance the study of museum collections with the sites themselves, considering them as both living cultural heritage and their own form of curated space.

Pattern 6: The majority of physical exhibitions coined ‘blockbuster’ or ‘international’ have short lifespans (a few months, a few venues) and are limited to the people who live near the museum and/or can travel there.20 Many are framed as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity (Frick, NMAA, National Gallery London, Fondation Louis Vuitton) and charge significant entrance fees. The catalog remains the permanent product and is often priced between $50-$200.21

Response 6: Create a website that will have a long lifespan, combines the exhibition experience and catalog (book) into a single free platform, and encourages repeat visitation and use, including in the classroom, museum, and maybe even the site itself (fig. 13). Like a ‘blockbuster’ exhibition, attempt international reach but make the project actually accessible to international audiences, especially those in Iran.

Roots, Process, and Collaboration

The root of this project is a co-authored article written with Kimia Maleki on the Emamzadeh Yahya between 2018 and 2020. In this piece, we experimented with four methods: present history, or thinking about the current realities of the shrine; collaboration between two art historians who had each been called to the site through its displaced tiles in museums; observational fieldwork, what I termed “amateur anthropology;” and writing with a degree of personal voice, which can be common in anthropology but less so in art history.22 Our writing unfolded during COVID-19 and a wave of new publications and platforms devoted to expanding the geographical, temporal, and material frames of Islamic art and rethinking how scholarship is published and shared.23

While writing this piece, it became clear that collaboration and interdisciplinarity were key to the study of the Emamzadeh Yahya and that we had hardly scratched the surface of understanding the site. I concluded, “In the future, it would be ideal for an anthropologist to explore local archives and conduct a series of formal interviews and oral histories in order to learn more about these layers of response.”24 Some of this work has been accomplished in this project, thanks to the efforts of Maryam Rafeienezhad, who conducted sustained participant observation at the site over six months. Several other colleagues also conducted critical work at the shrine and in Varamin. Hamid Abhari built a robust portfolio of photography and videography over three visits (October 2021, January 2024, October 2024); Jabbar Rahmani led a series of important interviews with local scholar Mohammad Amini; Nazanin Shahidi Marnani studied the tomb’s yadegari; and Ahmad Khamehyar contextualized the saint and site in relation to other Emamzadehs and emamzadehs.

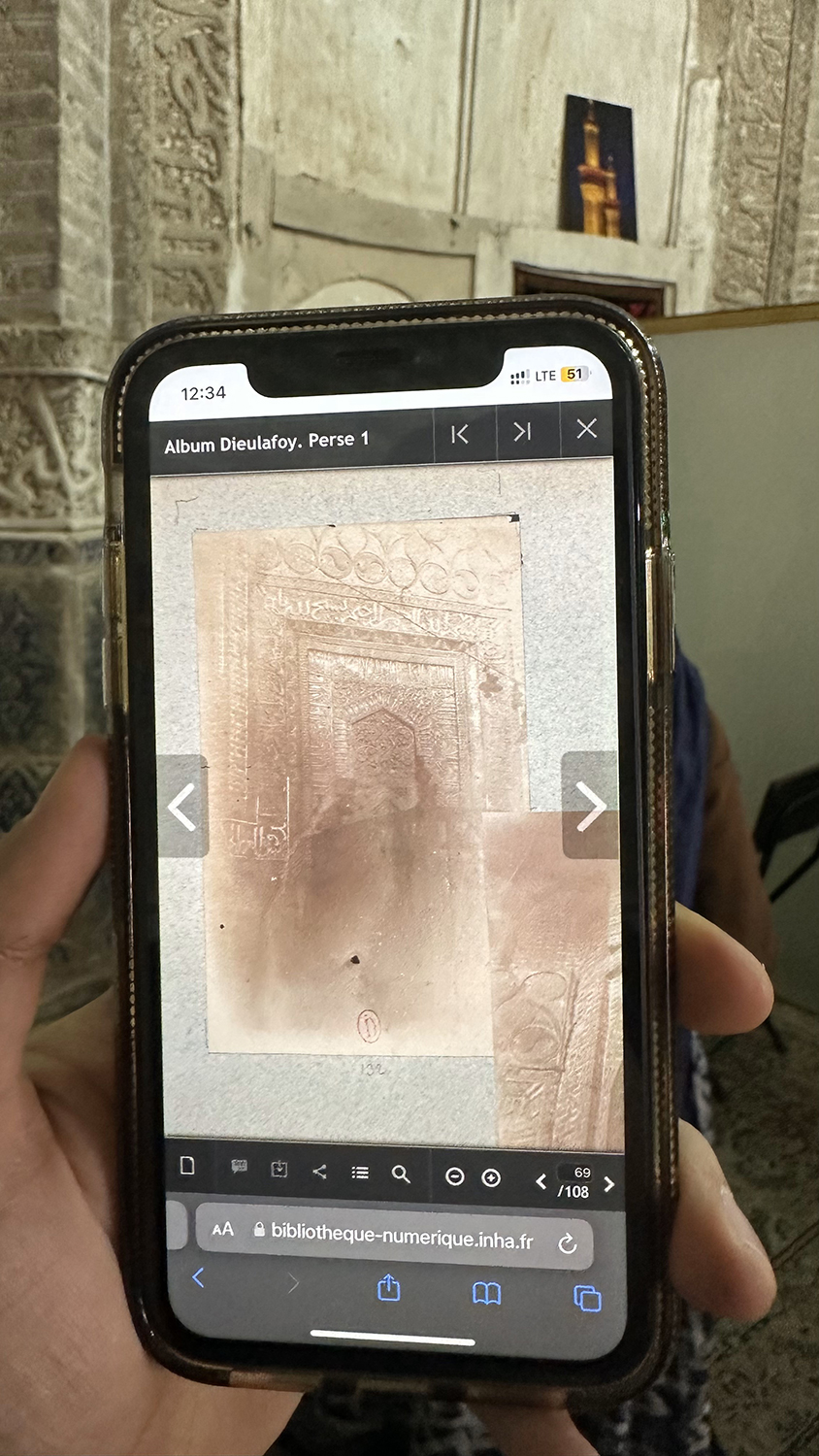

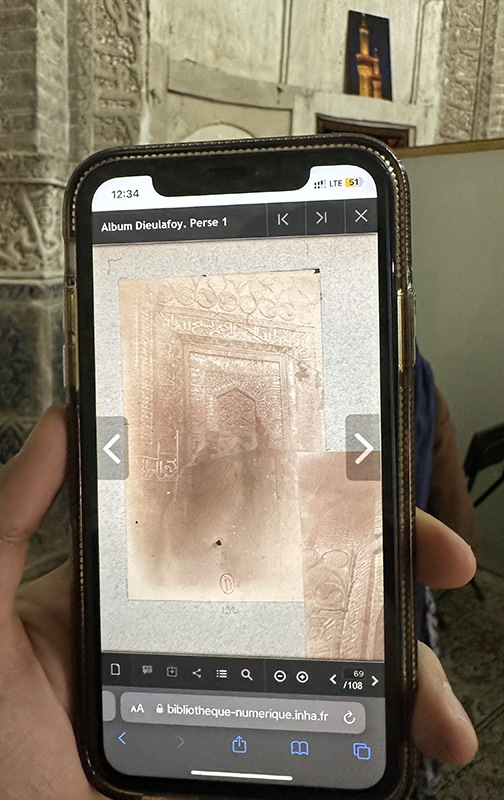

Alongside these site-based efforts, Hossein Nakhaei and I continued to mine texts, archives, and museum collections from afar, a slow burn for both of us. A single text was often an interpretive game changer, as in the accounts of Qajar officials ʿAliqoli Mirza Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh (1863, 1877) and Mohammad Hasan Khan Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh (1876). The same was true for photographs like Jane Dieulafoy’s 1881 image of the mihrab in situ (see fig. 13). The site’s photographic archive expanded steadily over time, culminating in this timeline, and in turn played a pivotal role in another form of sharpened perception: digital recreations.

The fruits of these interdisciplinary research collaborations are considerable: a true present history (ethnography) of the shrine; films that make the site and city accessible to international audiences; a fascinating oral history; catalog entries that lead us into related spaces in Kohneh Gel (nos. 48, 49); a survey of the tomb’s yadegari illuminating continuous ziyarat; a study of the shrine rooted in the saint himself; and six collaborations between me and Nakhaei. All of these collaborations were driven by a mutual commitment to the work, not by Euromerican, and especially art historical, value systems rooted in single authorship.25

[Update May 2025: Emadaldin Sheikhalhokamaee’s study of four historical tombstones in the Emamzadeh Yahya complex has been added to the website.]

Contents and Galleries

Unlike most physical exhibitions, which are rooted in the curation of physical objects, this exhibition is rooted in the curation of knowledge. As already noted, the project’s intellectual frames were opened as widely as possible: an interdisciplinary diachronic history of the Emamzadeh Yahya over seven hundred years (1200s to 2024), combined with related contextual material and acts of alternative museology (the responses outlined above). Thereafter began the process of reaching out to many ‘lenders’ (lenders of knowledge in this case) to fill gaps and needs in content. In some cases, my commissions were driven by my ability to collaborate directly with archivists and curators.26 In others, they were propelled by four general goals: to create truly interdisciplinary contents, capture a variety of perspectives, include scholars in Iran, and mix big picture contributions (overviews, summaries) with focused pieces.

Like any physical exhibition, this one has a distinct design and organization. The six galleries are each devoted to a theme. Varamin explores the city-village-suburb over the long durée, much like our framing of the Emamzadeh Yahya. Building focuses on the Emamzadeh Yahya itself and has an architectural and art historical bent. Ritual considers the sites, rituals, and material cultures of Twelver Shiʿism across many contexts. Luster focuses on the ceramic technique used to make the tiles associated with the Emamzadeh Yahya and many other medieval sites. Museum explores collecting and museology across a variety of institutions and materials, including luster tiles, photographic archives, and ritual objects. People illuminates the individuals who have visited, preserved, documented, and used the Emamzadeh Yahya over many centuries. Each gallery offers research in several formats, including essays, films, and interactives. There are many overlaps in content, and the galleries should be considered a fluid organizational frame, not a firm taxonomy.

All told, the website includes over 70 contributions between the Galleries and Checklist. The contributors are a mix of anthropologists, historians, architectural historians, art historians, curators, potters, archivists, architects, and non-academics. There are of course some gaps in content. Some research plans were thwarted, some commissions were never completed, some features required more time and are coming soon, and some work had to be stopped due to a lack of funding.

The Future

During this project, some people have asked: Do you plan to a do a physical version of this, and what is your stance on repatriation? The first question is difficult to answer. A physical exhibition would naturally fall short in many categories and potentially reinforce some of the museological infrastructures that this project has sought to avoid. However, a physical exhibition need not reinvent this wheel but instead offer what this website cannot: the actual physical materials and a firsthand experience with them, which can leave quite an impression. Many museums that own the tomb’s luster tiles keep them hidden away in storage, often because they are broken or in fragments and hence deemed not good enough for display. It would be ideal to see these fragments prioritized, much like the single tiny tip of a cross remounted at the top of the mihrab void in the tomb (figs. 15–16).27 It would also be refreshing to see more tiles displayed in ways that enable their textured appreciation in the flesh: in the round, in shifting light (jump ahead to vid. 3), and in relation to other similar examples. Each museum and curator will have to decide if and how they wish to display, re-display, and/or re-interpret the displaced tiles now in their care.

As for repatriation, this is a very important topic, but our priority has been to do the work and research first, and to do it accurately. In Mihrab: Essay, we will answer many questions about the trials and tribulations of this iconic luster ensemble, repairing a great deal of misinformation in the process. In his forthcoming Digital Tools, Hossein Nakhaei will digitally reunite the Emamzadeh Yahya’s displaced tiles with their original walls in the tomb. This act of ‘digital reparation,’ as he likes to call it, will significantly improve how the tiles are understood and remembered, shifting their perception from isolated objects in the white cube to architectural revetment in the tomb.

Some of this research has already impacted the physical museum. Inquiries on luster tiles in the Boijmans collection in Rotterdam played a role in their inclusion in a display devoted to provenance (fig. 17). A display in the National Museum of Scotland deliberately included a photograph showing the tomb in use, offering an important contrast to the frozen façade shot (fig. 18). Some curators have asked if I can provide a QR code to put on physical labels (available here), and some research conducted for catalog entries here (no. 17) has been paralleled on physical labels (figs. 19–20). It is hoped that this website will fill various interpretative and visual gaps in physical museums and be a useful resource for curators, education departments, and museumgoers alike. The dialogue between physical museums and independent digital projects can be productive and mutually beneficial, as attested by some of the collaborations here.

Video 3. Using movement to animate the luster surface of star A 3872 [KN&V] (see fig. 17). Video by Keelan Overton, 2022.

For the study of Persian architecture, websites present a promising future, whether framed as archaeological databases (Gazetteer, Ghazni), collections of virtual experiences (Paris, MAVCOR), or online exhibitions/books like this one. It is of course impossible to conduct a project of this scope for every historical monument in Iran, and it is not always necessary. However, for sites like the Emamzadeh Yahya that have been irreparably damaged by collecting, conceptually effaced in many institutions worldwide, and which retain significance far beyond academia and the museum, the website offers a suitable bridge.

At the end of this project, I am pleased that it has partially resolved some of the seismic disconnects identified from the start. Audiences in Iran will now have better access to some of the shrine’s archives and tiles, and the phrase ‘Emamzadeh Yahya’ on museum labels worldwide will hopefully no longer be in one ear out the other. The project has achieved many of its goals of accessibility and created many bridges: between languages, disciplines, scholars, bibliographies, audiences, perspectives, and methodologies. It may also contribute to some larger conversations in the humanities about the future of comparable independent projects beyond the academic gilded cage.28

***

هو العلی

هرکه درین روضه دراید ز صدق / هست دعایش به یقین مستجاب

He is the Exalted

Anyone who enters this garden sincerely / His prayers will certainly be answered.29

Audio 1. Recitation of the likely Ilkhanid-period (ca. 1330–50) yadegari in the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya by Nazanin Shahidi Marnani (see her essay, no. 2).

The yadegari that pilgrims have written in the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya convey their belief in the saint and calling (talabideh shodan) to the site. As researchers, we have likewise been called to the shrine, albeit as a topic of scientific and academic inquiry. Put simply, the subject of study did not disappoint. The Emamzadeh Yahya has propelled a tremendous amount of research across disciplines, inspired many meaningful collaborations, posed formidable challenges and questions, and led us down many unexpected paths. While this may not be a once-in-a-lifetime exhibition with a red carpet and gift shop, this may be a once-in-a-lifetime project. For this research opportunity, we owe our gratitude to the builders of the Emamzadeh Yahya and the centuries of pilgrims, residents, caretakers, visitors, and preservationists who have helped to keep it alive and well through their beliefs, care, labor, records, and photographs.

Much of the project ultimately boils down to time. Instead of approaching the Emamzadeh Yahya as an Ilkhanid monument alone, we have considered it over the long durée. We have weaved between its centuries, decades, days, calendars, and seasons. The result is an ever-shifting perception of the complex, depending on which time you choose to explore. Time has also been integral to our research: the time to search through many archives and collections, develop new methods and tools, and build collaborations. The way we have packaged our findings in this website is also the product of time—of this Digital Age—but the experience we offer here is not one of instant gratification. We hope you will enjoy wandering through this garden of collaborative knowledge and be called back to it many times.

Please join me for a brief tour of the website (coming soon).

Thank you to Hossein Nakhaei, Peyvand Firouzeh, Moya Carey, and Kimia Maleki for their feedback on this essay.

Acknowledgments (for the project)

This long and complex project has been filled with many meaningful and wonderful collaborations. Most of all, I thank Julia Falkovitch-Khain and Hossein Nakhaei, the consistent rocks without whom this website would not exist. Hossein: thank you for opening my eyes to digital tools and always revising, expanding, and heading in new directions in architectural history. Julia: thank you for being the best possible partner for building this website and always figuring out how to materialize ideas. I was very fortunate to work closely with two such kind, creative, and sage individuals. Maryam Rafeienezhad and Jabbar Rahmani: thank you for the privilege of seeing the shrine and city through your eyes and for helping us bring the project into the present and beyond art history. Hamid Abhari: thank you for the invaluable photography and videography and for creating the three films that are sure to be favorites.

Two personal fellowships were critical bookends to my work: a Getty Scholar fellowship at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles in fall 2021 and a residency at the Institut national d’histoire de l’art in Paris in spring 2024. The former provided the only source of substantive personal funding, and the latter gave me the chance to complete final research. Thank you to Sepideh Parsapajouh, Thomas Galifot, Delphine Miroudot, Martina Massullo, and many other colleagues and friends for the special experiences that spring. During the last five months of production, I was able to bring on Hoda Nedaiefar and Alisala Nunes, each of whom played critical roles and helped to complete our website dream team, as well as copyeditor Maryam Momeni. I am grateful to all contributors and participants for sharing their expertise and talents, the large cast of translators and copyeditors, and all curators and archivists who opened doors for research. Thank you to those who shared images and waved permission fees for this open-access project.

On behalf of everyone involved in the project, I sincerely thank our financial supporters, our host Khamseen, and the University of Michigan’s IT and LSA, especially Josh Simon and Tony Winkler, for the critical efforts to secure the website’s protection, migration, and future. I am grateful to Christiane Gruber for being open to my initial pitch, giving me the blank slate, and respecting the intellectual independence of the project while simultaneously offering it support. At Team Khamseen, thanks also to Mira Xenia Schwerda, Bihter Esener, and Deniz Vural. To all the friends and colleagues who provided advice, opinions, critiques, eyes, and expertise along the way: thank you, you know who you are. Above all, I thank the life partner who supported this project more than anyone or any institution and ultimately made it possible. Thank you for your patience, keeping the lights on, providing endless perspective, not wanting to be named, and inspiring 33 Arches.

Citation: Keelan Overton, “Introduction to the Emamzadeh Yahya Project and Online Exhibition.” Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.

Notes

Author’s note: This essay is aimed at the exhibition’s international audiences and has been written with multi-lingual readability and Persian translation in mind. The Emamzadeh Yahya is defined as an astan-e moqaddas (holy shrine) on its entrance gate. In English, I use the terms ‘emamzadeh,’ ‘shrine,’ and ‘site’ interchangeably to describe the complex. Some of the methods and experiments undertaken in this project raise larger questions for the fields of Persian and Islamic art (as defined in Euromerican circles) and the humanities generally. I place these comments in the notes so as not to distract from the focus on the shrine.

- See Kimia Maleki’s comments in our co-authored article, “The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: A Present History,” 134. Comparable observations have been expressed to me by other students in Tehran or those who have been trained there. Some museum displays are discussed in our article as well as my later “Framing, Performing, Forgetting” and “Jane Dieulafoy in Varamin.” ↩

- This is an independent project, because it was created and governed by individuals beyond institutions. I am an independent scholar (not an employee of a university or museum) and have directed all aspects of the Emamzadeh Yahya Project in this independent capacity. The project has been built from scratch, follows its own systems and objectives (not those of an institution), and is rooted in the collaborations of its small research and website teams. I began planning the project in early 2021, in the wake of the co-authored article with Kimia Maleki. When it was well developed, I presented it to international colleagues for feedback (Karen Ruffle’s Sensing Shiʿism Working Group, July 2021; meetings I organized with potential contributors, September 2021 and February 2022). The consensus was that I should try to find an institutional host for the website to ensure its technical security and maintenance. In early 2023, Khamseen agreed to host the website and the Department of the History of Art at the University of Michigan provided a seed grant (a start-up grant used for initial costs). I ultimately secured four additional competitive grants for the project, but this funding did not cover everything. Most of the extensive labor required to manage and complete the project was not financially supported (see note 28). ↩

- I have discussed these issues in “Framing, Performing, Forgetting” and “Jane Dieulafoy in Varamin.” ↩

- The term ‘living’ was ultimately removed from the title, because it was inherent to the Persian term selected for ‘shrine:’ ziyaratgah, or place of pilgrimage. This project uses the terms ‘Iranian’ and ‘Persian’ relatively fluidly while acknowledging debates about their usage. In English academic circles, the term ‘Persian’ is used to refer to the language (فارسی) and often as a cultural adjective (for example, ‘Persian art’). The Persian language and Persian cultural traditions are not limited to the borders of modern-day Iran, and phrases like ‘Persianate world’ and ‘Indo-Persian culture’ encompass more expansive geographies (for example, the Caucasus, Central Asia, and the Indian subcontinent). In this project, I generally use the term ‘Iranian’ to describe things specific to modern-day Iran (for example, an ‘Iranian shrine’). ↩

- See my earlier discussions in “The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: A Present History,” and “Framing, Performing, Forgetting.” ↩

- As in many other fields, the multi-sensory is becoming popular in Islamic art and studies. Consider Engaging the Senses: Arts of the Islamic World (NMAA, ongoing), Dining with the Sultan: The Fine Art of Feasting (LACMA, 2023), Sensory history of the Islamic world, a special issue of The Senses and Society (2022), and SENSIS: The senses of Islam. On Khamseen, see Patricia Blessing’s lecture Water and Sound in Islamic Architecture. ↩

- About one fourth of the existing budget has been devoted to the construction of the hand coded website. This cost is comparable to a major subvention for a print book in art history. Thank you to Julia Falkovitch-Khain, University of Michigan’s LSA TS and ITS, Bihter Esener, Christiane Gruber, and Mira Xenia Schwerda for efforts to secure the website’s longevity. ↩

- Among many articles on this topic, see Jurčišinová, Wilders, and Visser, “The Future of Blockbuster Exhibitions After the Covid-19 Crisis.” ↩

- For an analysis of the 1931 exhibition, see Wood, “A Great Symphony” and Rizvi, “Art History and the Nation.” ↩

- On the international congresses, see Frye, “Asia Institute.” ↩

- For some literature on these shifts, see Mozaffari, “The (Unfinished) Museum at Pasargadae” and Mozaffari, Forming National Identity in Iran. ↩

- My use of the phrase ‘Islamic art’ refers to the globalized discipline that shapes curricula and galleries from Kuala Lumpur to Doha, Oxford, and New York. The term is highly (and rightly) debated, and the field has an immense historiography devoted to its problematic origins, definitions, semantics, and collections. For some literature on the field’s museumscape, see Roxburgh, “After Munich,” Junod et al., Islamic Art and the Museum, and Norton-Wright, Curating Islamic Art Worldwide. Given its focus on one Iranian shrine and its related traditions, this project has been able to steer clear of this generalist rubric. ↩

- The Legacy of Genghis Khan catalog includes substantive scholarly research and is available for free on MetPublications. This kind of catalog appears on many English-language university syllabi. ↩

- This independent path has not been automatic or easy, especially given funding restrictions and the complex nature of the project. ↩

- Some museums do invest significant resources into 3D experiences that give international audiences a chance to ‘visit’ the exhibition. Consider the Chester Beatty’s Meeting in Isfahan 3D Space. A few museums, like the Metropolitan, also put their catalogs online for free (see note 13). ↩

- One example is the 2009 Shah ʿAbbas exhibition in London. See Canby, Shah ʿAbbas: The Remaking of Iran, chapters 3 and 4, on Mashhad and Qom respectively. These are excellent chapters. ↩

- This paradigm is changing. The British Museum has taken a lead in integrating ‘art’ and ‘material culture,’ which is not surprising given its substantive archaeological collections. Consider the 2012 exhibition curated by Venetia Porter Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam and the renovated (2018) Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic world. See Porter, Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam and Porter and Greenwood, “Displaying the Cultures of Islam.” On this dichotomy, see also Julia Gonnella, “Islamic Art Versus Material Culture.” ↩

- Ethnographic museums naturally have a different take. Consider the chapter on Iran in the catalog of the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam (now part of Wereldmuseum). See Shatanawi, Islam at the Tropenmuseum, 154–81. ↩

- In English, the term ‘object’ is often used in museums to refer to the things in the collection. For my discussion of a kiosk in the British Museum showing photographs of some sites in relation to their displayed tiles, including the Emamzadeh Yahya, see “Framing, Performing, Forgetting.” There are some examples of museum publications that delve deeply into their collections’ histories. Consider, for example, Carey, Persian Art: Collecting the Arts of Iran for the V&A, especially chapter 2, with important information on luster tiles. ↩

- The definition of a ‘blockbuster’ exhibition varies but generally refers to temporary exhibitions that include international loans, often travel to other institutions and sometimes other countries, and/or contribute to the museum’s international reputation. Many have a significant marketing and promotional layer. See Jurčišinová, Wilders, and Visser, “The Future of Blockbuster Exhibitions After the Covid-19 Crisis.” A few examples of twenty-first century exhibitions that can be described as blockbuster include Legacy of Genghis Khan (2002–3), Shah ʿAbbas: The Remaking of Iran (2009), Gifts of the Sultan (2011), Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam (2012), The Art of the Qur’an (2016–17), Epic Iran (2021), Dining with the Sultan (2023–24), and Wonders of Creation: Art, Science, and Innovation (2024–25). In the United States, many of these exhibitions are funded by sizeable grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities. ↩

- For some exceptions, see notes 13 and 15. ↩

- Overton and Maleki, “The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: A Present History,” 143n3. I first learned about the Emamzadeh Yahya through its luster mihrab preserved in Shangri La in Honolulu. An example of self-reflexive work in the field of Islamic art history is Rizvi, “The Other Side of Paradise.” ↩

- Consider the Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World (MCMW), published by Brill (2020) and the digital platforms Platform (2019), Khamseen (2020), Asmaneh (new website 2021), and Nowruzgan. ↩

- Overton and Maleki, “The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: A Present History,” 146n51. ↩

- It is a good sign that some in art history are beginning to challenge this paradigm. Consider the Editor’s Note in the July 2023 issue of The Art Bulletin: “Tenure and promotion committees still tend to regard joint projects, even when interdisciplinary and innovative, as less significant than the scholarship produced by a single author. Such entrenched biases overlook the innovative conceptualization of research undertaken by scholars when they seek to find common ground with others or, indeed, the extra labor that they must undertake to develop and coordinate collaborative research and writing projects.” See Christy Anderson, “The Collaborative Essay,” 6. The trick will be to create more funding infrastructures that support collaborative research and labor undertaken beyond the university. Eligibility requirements that require institutions to administer grants (for example) exclude many projects, including this one. ↩

- This was the case during a spring 2024 fellowship at the Institut national d’histoire de l’art (INHA) in Paris, during which I also visited London. ↩

- For Abbas Akbari’s creative take on fragments, see his essay here, fig. 16. ↩

- One of the biggest challenges of this project was securing funding as an independent scholar. This is a large topic, but for now, I simply pose some questions: Should grants be based on merit or one’s title in an institution? In the global field of Islamic art, in which many scholars do not even have the option of institutional support, how can we create more systems for supporting individuals? What is the future of collaborative grassroots projects that are really only possible because of their independence? What is at stake when independent projects must ‘institutionalize’ to secure funding? ↩

- Shahidi Marnani, “If some day,” yadegari no. 2. ↩

Bibliography

- Anderson, Christy. “The Collaborative Essay” (Editor’s Note). The Art Bulletin 105, 3 (September 2023): 6–7. [Taylor and Francis]

- Canby, Sheila R., ed. Shah ʿAbbas: The Remaking of Iran. London: British Museum Press, 2009. [Internet Archive] [WorldCat]

- Carey, Moya. Persian Art: Collecting the Arts of Iran for the V&A. London: V&A Publishing, 2017. [WorldCat]

- Favereau, Marie, ed. Les Mongols et le monde: L’autre visage de l’empire de Gengis Khan. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2023. [WorldCat]

- Fellinger, Gwenaëlle, ed. L’Empire des roses: Chefs-d’œuvre de l’art persane du XIXe siècle. Ghent: Snoeck, 2018. [WorldCat]

- Frye, Richard N. “Asia Institute.” Encyclopædia Iranica, July 20, 2003, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/asia-institute-the-1.

- Gonnella, Julia. “Islamic Art Versus Material Culture.” In Islamic Art and the Museum: Approaches to Art and Archeology of the Muslim World in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Junod Benoît, Georges Khalil, Stefan Weber, and Gerhard Wolf, 144–48. London: Saqi, 2012. [WorldCat]

- Haji-Qassemi, Kambiz, ed. Ganjnameh: Cyclopaedia of Iranian Islamic Architecture, vol. 13, Emamzadehs and Mausoleums (Part III). Tehran: Shahid Beheshti University Press, 2010. [WorldCat]

- Junod, Benoît, Georges Khalil, Stefan Weber, and Gerhard Wolf, eds. Islamic Art and the Museum: Approaches to Art and Archeology of the Muslim World in the Twenty-First Century. London: Saqi, 2012. [WorldCat]

- Jurčišinová, Kaja, Marline Lisette Wilders, and Janneke Visser. “The Future of Blockbuster Exhibitions After the Covid-19 Crisis: The Case of the Dutch Museum Sector. Museum International 73, 3–4 (2021): 20–31. [Taylor & Francis]

- Komaroff, Linda, and Stefano Carboni, eds. The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256–1353. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2002. [MetPublications]

- Mozaffari, Ali, and Nigel Westbrook. “The (Unfinished) Museum at Pasargadae. In World Heritage in Iran: Perspectives on Pasargadae, edited by Ali Mozaffari, 197–224. Surrey, UK: Ashgate, 2014. [WorldCat]

- Mozaffari, Ali. Forming National Identity in Iran: The Idea of Homeland Derived from Ancient Persian and Islamic Imaginations of Place. London: I.B. Tauris, 2014. [WorldCat]

- Norton-Wright, Jenny, ed. Curating Islamic Art Worldwide: From Malacca to Manchester. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020. [WorldCat]

- Overton, Keelan. “Framing, Performing, Forgetting: The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin.” Platform, September 19, 2022, https://www.platformspace.net/home/framing-performing-forgetting-the-emamzadeh-yahya-at-varamin.

- Overton, Keelan, and Kimia Maleki. “The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: A Present History of a Living Shrine, 2018–20.” Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World 1 (2020): 82–111. [Brill]

- Porter, Venetia, and William Greenwood, “Displaying the Cultures of Islam.” In Curating Islamic Art Worldwide: From Malacca to Manchester, edited by Jenny Norton-Wright, 107–16. Curating Islamic Art Worldwide: From Malacca to Manchester. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

- Rizvi, Kishwar. “The Other Side of Paradise, or ‘Islamic’ Architectures of Containment and Erasure.” Platform, June 24, 2019, https://www.platformspace.net/home/the-other-side-of-paradise-or-islamic-architectures-of-containment-and-erasure.

- Rizvi, Kishwar. “Art History and the Nation: Arthur Upham Pope and the Discourse on ‘Persian Art’ in the Early Twentieth Century.” Muqarnas 24 (2007): 45–65. [JSTOR]

- Roxburgh, David J. “After Munich: Reflections on Recent Exhibitions.” In After One Hundred Years: The 1910 Exhibition “Meisterwerke muhammedanischer Kunst” Reconsidered, edited by Andrea Lerner and Avinoam Shalem, 357–86. Leiden: Brill, 2010. [Brill]

- Shahidi Marnani, Nazanin. “If some day a noble soul reads this... Documenting the yadegari of the Tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin.” Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton, 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online. [this website: Persian and English translation]

- Shatanawi, Mirjam. Islam at the Tropenmuseum. Arnhem: LM Publishers, 2014. [WorldCat]

- Wood, Barry. “‘A Great Symphony of Pure Form’: The 1931 International Exhibition of Persian Art and Its Influence.” Ars Orientalis 30 (2000): 113–30. [JSTOR]