Introduction to the Checklist: A Curatorial Experiment

Keelan Overton

When I visited the Getty’s Lumen: The Art and Science of Light (September 10–December 8, 2024), an exhibition focused on the science of light over the long medieval period, I immediately gravitated toward the corner displaying fragments of muqarnas. As typical in many galleries, these historical elements from modern-day Iran, Uzbekistan, Turkey, and Spain were displayed with an example of contemporary art.1 An enormous piece of wing-like mirrorwork spanned the corner of the room and was immediately recognizable as Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian (d. 2019). Walking up to the piece, I reappreciated the act of visiting exhibitions in the flesh. As I moved across its sparkling surface, I could see my reflection and immediately thought of a video sent to me by checklist contributor Reza Daftarian of him doing the same in the Shrine of Shah Cheragh in Shiraz (no. 12). Walking over to the label on the right, I was pleased to see a photograph of a mirrored interior of Shah Cheragh, mentioning the space as one of Farmanfarmaian’s inspirations.

Video 1. Panning over Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian’s “Untitled (Muqarnas)” in “Lumen: The Art and Science of Light,” The Getty Center, Los Angeles. Video by Keelan Overton, September 2024.

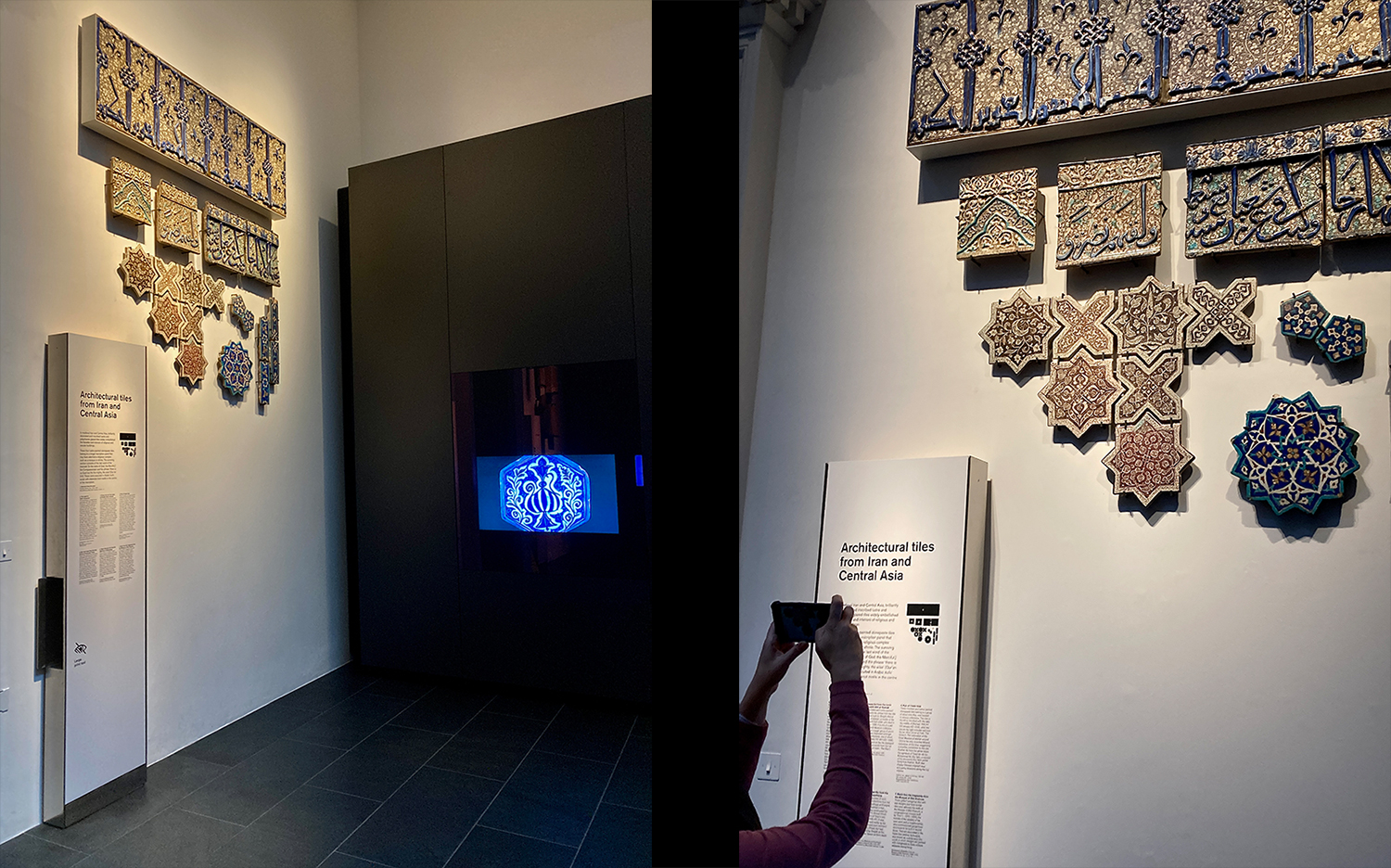

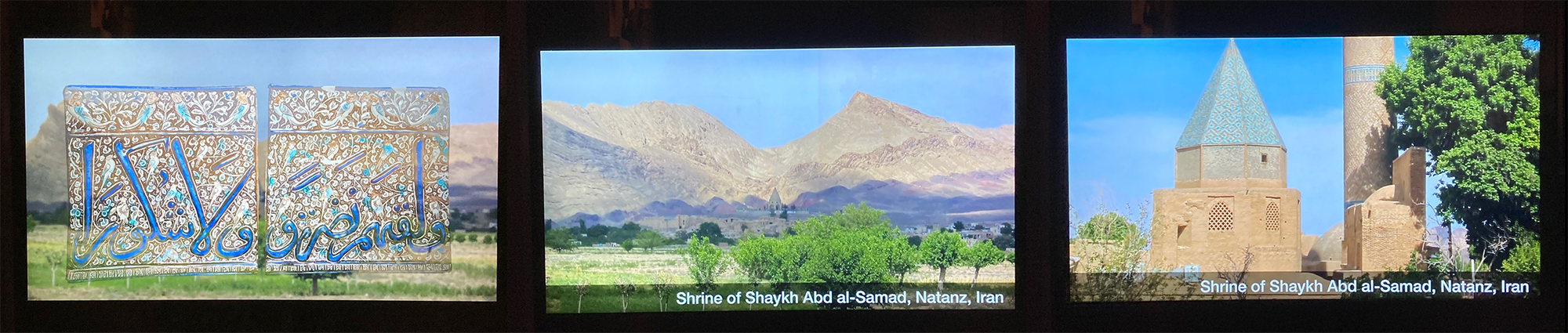

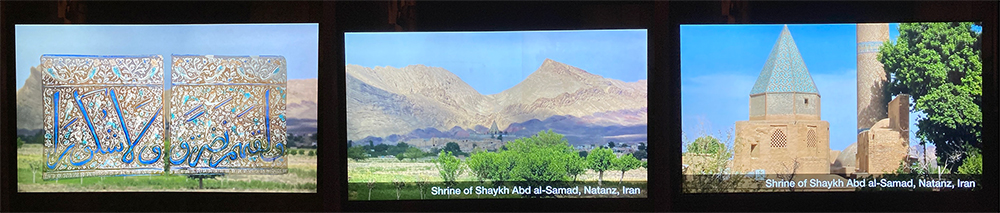

I then took in the fragments to the left and their label, located far below. It included one photograph: the muqarnas ceiling in the tomb of Shaykh ʿAbd al-Samad at Natanz, a commonly reproduced view. What the label did not show is the rest of the small interior that one sees as the eye trails down (watch this video): the many imprints left behind when the tomb’s luster tiles were systematically stolen from the walls in the late nineteenth century. Left uncovered for posterity to see and protected behind plexiglass, these imprints are a veritable frozen crime scene and an important form of site-based remembrance of a tremendous loss.

The label’s focus on the tomb’s beauty (its muqarnas ceiling) at the expense of its reality (the lower walls) reminded me of a similar situation in the Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic world in the British Museum, where the shrine’s stunning landscape and exterior were chosen as representative views, but this time in relation to a display mixing one of its luster tiles with many others (fig. 2).2 The selection of these beautiful photographs is not surprising in a museum context, and discussing the plunder of the Natanz tomb would have been distracting in the Getty’s display focused on muqarnas and light. However, it would have made more sense to show a photograph of a building that actually or likely supplied some of the fragments on view.3

Seeing the Farmanfarmaian was an example of the pleasure, and even necessity, of experiencing works of art in the flesh, but this positive experience contrasted the fragments to the left, which were never intended to be displayed as isolated ‘objects.’ As in many museum galleries, they were mounted high to convey architectural context, but a corner of a gallery in Los Angeles combining five fragments from drastically different sites is never going to achieve context. As in the British Museum, where the tiles were also mounted high (see fig. 2), I wished these muqarnas would have been displayed low on the wall, or even in a case, so that I could look at them closely. This can be an irony in the museum: the attempt to convey architectural context through elevated mounting sometimes undermines the very reason for the display: to see the thing.

This little corner of “Lumen” encapsulated many museological patterns. The trend to combine the historical with the contemporary in displays of Islamic art; to include a single ideal photograph of an interior to convey context; to mix individual fragments from different sites on the wall; and to explore sensory perception and its impact in religious space. As I looked at the label for the Farmanfarmaian, I was pleased that the catalog entry in this online exhibition (no. 12) would provide additional resources on Shah Cheragh’s mirrorwork. The entry would not replace the experience of walking into the tomb, but through its combination of excellent photographs and video, it would translate some aspects of the spatial and sensory experience.

An Imaginary Checklist

This curatorial experiment imagines what it would be like to build a checklist liberated from the contingencies that often shape physical exhibitions. These include the condition of the object (if it can travel, how long it can be displayed), politics of all sorts (between states, institutions, curators), and the significant finances required to pack up, ship, and insure the objects. If these contingencies were off the table, what would a checklist devoted to Iranian shrines look like? Who would we ‘borrow’ from? What would we want to include? Which stories would we tell, and how would those narratives shift or shape the scholarship?

The goal of this checklist is to explore the material cultures of Iranian shrines first and foremost through the sites themselves. An attempt has been made to cover the typical things that one might see and experience in Iranian tomb-shrines of Emams and their descendants (Emamzadehs). This includes the broader setting, the architectural decoration and portable objects inside the tomb, and the variety of ephemeral and sensory experiences that animate the space. A very important caveat is that Iran includes over 10,000 emamzadehs, and like any type of sacred space, they can vary dramatically (jump below to Variations on a Theme).4 Creating a complete picture in 50 entries would be impossible, and holes can be rightly poked in any generalist rubric. The goal of this checklist is to provide useful context and comparison for our focus on the Emamzadeh Yahya, and a goal of this essay is to stitch some of the entries back to the site. Like any checklist, this one has been shaped by some contingencies, including networks of colleagues and access to materials.

This hypothetical checklist includes responses to some of the prevailing patterns in the international museumscape of Persian and Islamic art (see my general introduction). It includes many loans from Iran (pattern/response 2), substantive information on Twelver Shiʿism (pattern/response 3), and a mix of luxury artworks and ordinary things (pattern/response 4). Over half of the physical things on the checklist are in situ and offer an important contrast to checklists rooted in musealized objects. The imaginary ‘lenders’ to this grouping include the Emamzadeh Yahya itself, the hosayniyeh of Kohneh Gel, some other Iranian emamzadehs, the major shrine museums at Qom and Mashhad, anthropology museums in Europe, the Victoria and Albert and Hermitages of the world, and some perhaps lesser-known private collections. This mix of lenders would never be achievable in a physical exhibition, and certainly not one outside of Iran. Moreover, many of the things on this list could never be put in any white cube, including in Iran.

This curatorial experiment comes with some obvious tradeoffs. You will not see anything in the flesh, but you will hopefully gain a more holistic understanding of the represented shrines and related contexts that is relatively free of museological baggage. Our digital format also enables us to share much more information than what would typically be included on a label or even in the printed catalog. Entries range in length from 500 to 2000 words (no. 7, 19, 45), and most are richly illustrated. Many include video and audio that show objects in the round (no. 9, 21, 36), animate the context (no. 25, 45, 47), or provide a general sense of the setting (no. 12, 16, 21, 31). Two entries are filmed and show the curator handling the object while speaking her entry aloud (no. 32, 38).5

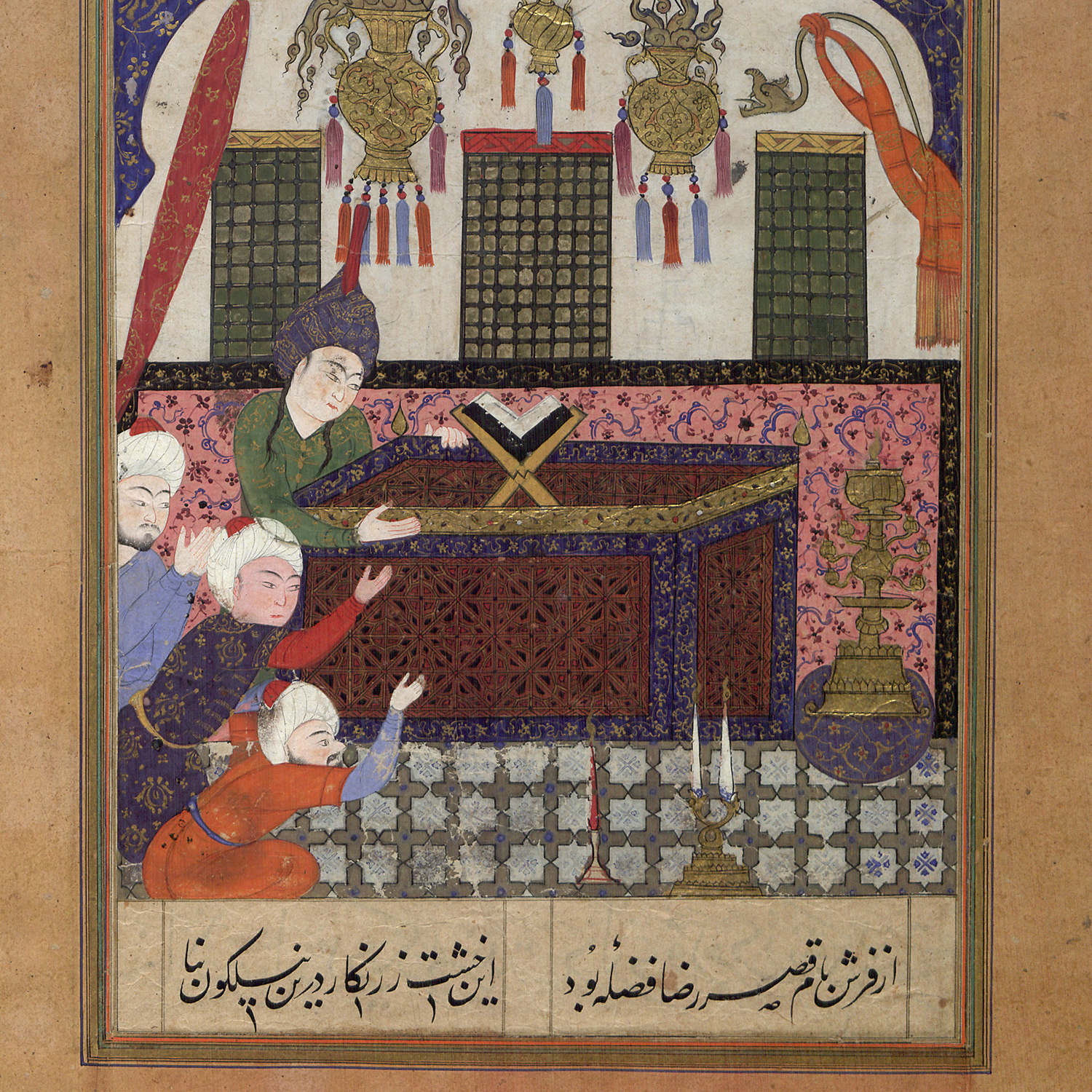

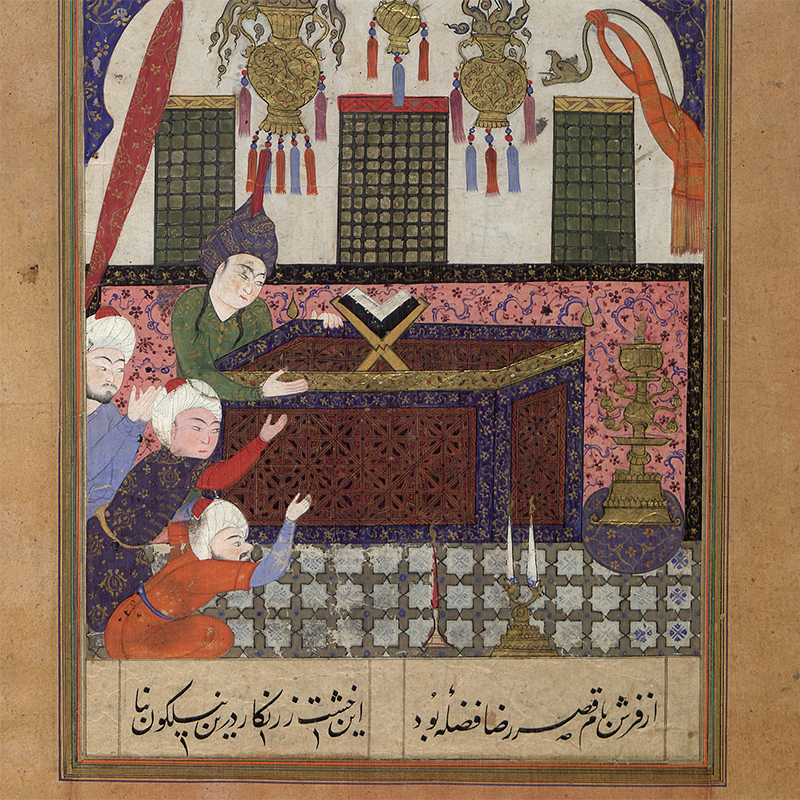

Variations on a Theme

As discussed in many places in this exhibition (see Twelver Shiʿism, Yahya b. ʿAli, Sites), the tombs of Emams and Emamzadehs vary considerably in form, scale, location, level of visitation, financial resources, and patronage. A freestanding small tomb in a village is very different from an enclosed courtyard complex like the Emamzadeh Yahya which is in turn distinct from a large neighborhood shrine in Tehran and in turn the sprawling city-shrine at Mashhad. Despite these differences, all shrines of Emams and Emamzadehs center around one element: the tomb of the saint, marked by a cenotaph. Certain treatments of the cenotaph are centuries long traditions—for example, its covering with a piece of fabric and other objects, including Qur’an manuscripts and lighting devices. At a certain point, it also became common to place a screen around the cenotaph, thereby protecting it from the immediate touches of pilgrims seeking its influx or baraka (compare figs. 4–5).

The physical forms of these furnishings and objects are likewise contingent on various factors and can range from the simple and mass-produced to the finest examples of artistic production. A comparison of three emamzadehs in Varamin illuminates this variety. Whereas the Emamzadeh Sakineh Banu and Emamzadeh ʿAli have simple rectangular screens (zarih) with no ornamentation, the Emamzadeh Yahya has an elaborate, gilded hexagonal zarih given to the shrine in 1389 Sh/2010–11 (figs. 6–8). The former two screens are covered in a green textile, but Emamzadeh Yahya’s zarih (no. 5) is left uncovered to show the Qur’anic inscriptions on its top edge. In the Emamzadeh ʿAli and Emamzadeh Sakineh Banu, sacred texts are applied to the zarih in a different way, via portable posters mounted to the screen, which is also a longstanding tradition with luxury iterations (no. 2, 26). A shared feature across the three zarihs is their beautification with flowers on the corners (no. 6).

When we zoom out and compare these three interiors generally, we see more examples of variations on a theme. All three distinguish the lower dado from the upper walls. In the case of the Emamzadeh Yahya, this was originally star and cross luster tiles dateable between 660–61/1262–63 (nos. 17, 18, 19). In the Ilkhanid-period Emamzadeh Sakineh Banu, we see a pattern of new (2003) hexagonal turquoise tiles that mimics historical revetment like that in the Emamzadeh Mohammad b. Jaʿfar Sadeq at Bastam (figs. 11–12). In the Emamzadeh ʿAli, the dado seems to mimic marbled stonework and is capped by its own version of an epigraphic frieze, in this case, green paint on a black background.

Whereas the plastered brickwork walls of the Emamzadeh Yahya luckily remain uncovered, those of the Emamzadeh ʿAli and Emamzadeh Sakineh Banu have been covered in new mirrorwork (ayeneh-kari). This new mirrorwork can be compared to the finest examples of nineteenth-century Qajar-period production, including in the Shrine of Shah Cheragh (no. 12) and Emamzadeh Shahzadeh Hosayn in Qazvin (map) (vid. 2).

Video 2. Interior of the Emamzadeh Shahzadeh Hosayn, Qazvin. Video by Keelan Overton, 2018.

When we turn to the tombs of the Emams, we observe similar traditions albeit on a much larger and more luxurious scale. Plastic flowers become real, and zarihs become major works of art whose patronage and production can be a national (no. 1) and even translational event. An example of the latter is the construction of the zarih of Emam Hosayn (d. 60/680), a five-year project undertaken in the Qom shrine and involving the famous painter Mahmoud Farshchian (no. 29) and dozens of artists and craftsmen. Upon completion in 2012, the 12,000 kg zarih was transported by caravan to Karbala, inspiring its own form of ‘on the road’ pilgrimage during its forty-five-day procession.6

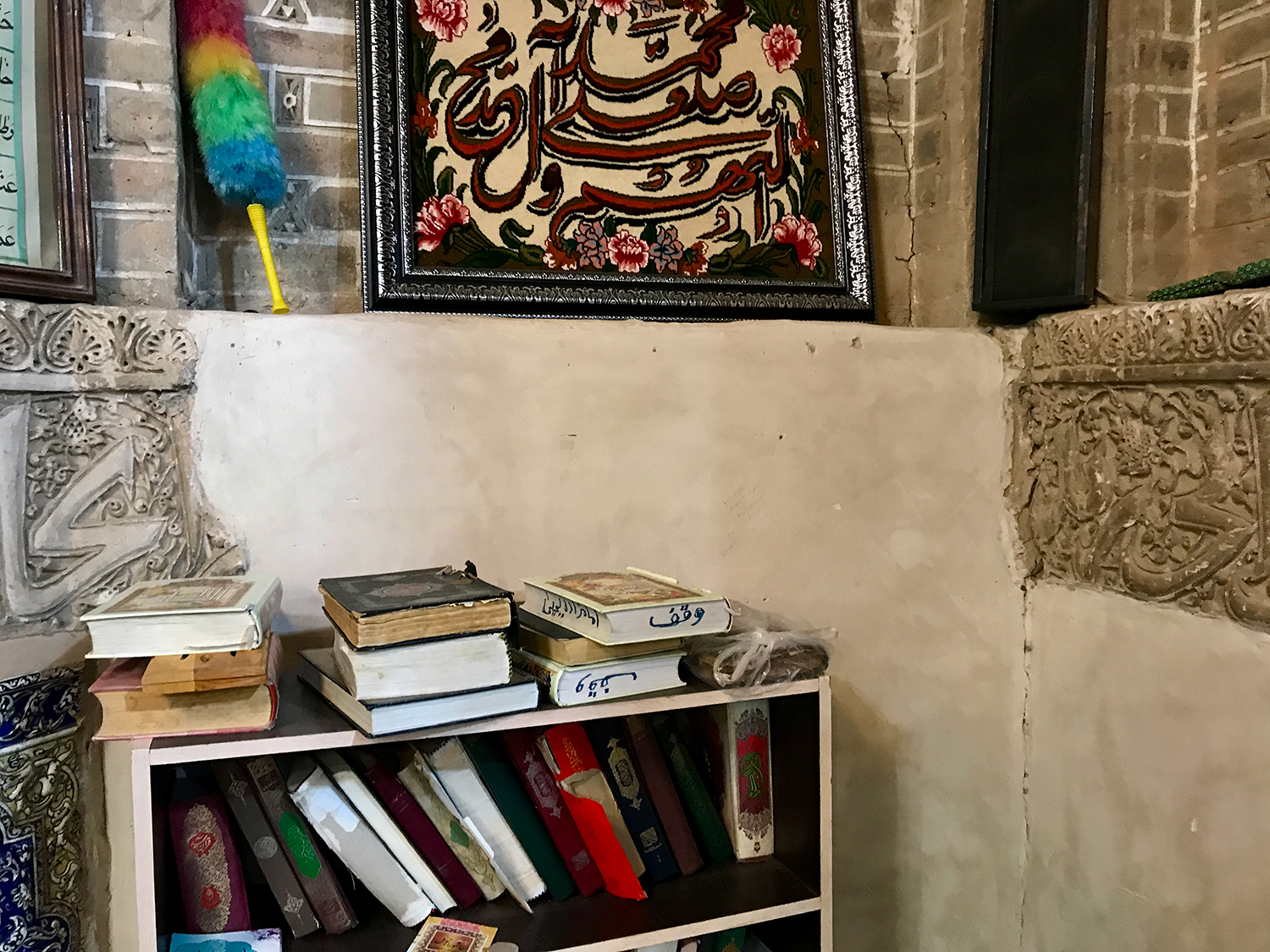

Shrines as Collections and Curated Spaces

Receiving gifts over time from different donors and through various formal and informal channels, Iranian shrines can become collections in their own right. One form of gifting to shrines is waqf, or charitable endowment. These endowments can be offered in many forms, including physical objects and furnishings that are critical to the shrine’s routine and sacred functions. Over the course of history, the largest shrines in Iran (for example, Mashhad, Qom, and Rey) have been the recipients of works of art intended to be used, including candlesticks, Qur’an manuscripts, signs with sacred texts, zarihs, mihrabs, cenotaphs, and doors. This explains why the collections of shrine museums are so relevant to the study of Persian art history, especially when the focus is on the ‘luxury’ production of the court.7

The fates of materials gifted to shrines can vary tremendously. A comparison of the trajectories of a parchment Qur’an manuscript endowed by Shah ʿAbbas to the Shrine of Emam Reza in 1008/1599 (no. 8) and a candlestick endowed by a named but as yet unidentified individual to the tomb of Emam Musa Kazem at Kazemayn in modern-day Iraq around the same time (no. 9) illuminates this point. The former remained in the shrine and ultimately became part of the complex’s formal museum system established in the 1930s (see no. 21). The latter was removed from the shrine, despite its endowment inscription warning against such a violation, and ultimately entered a private collection and in turn the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha.

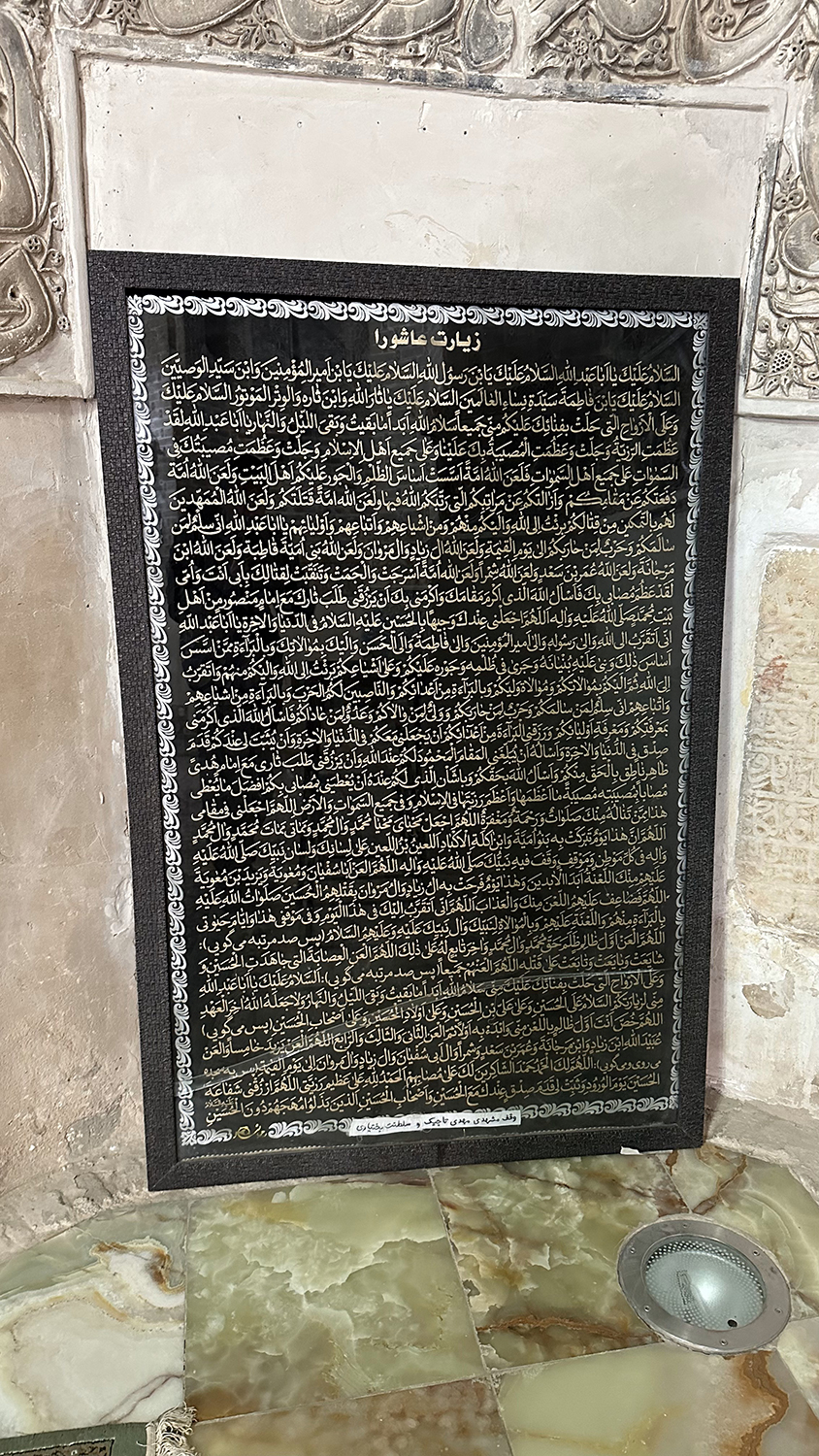

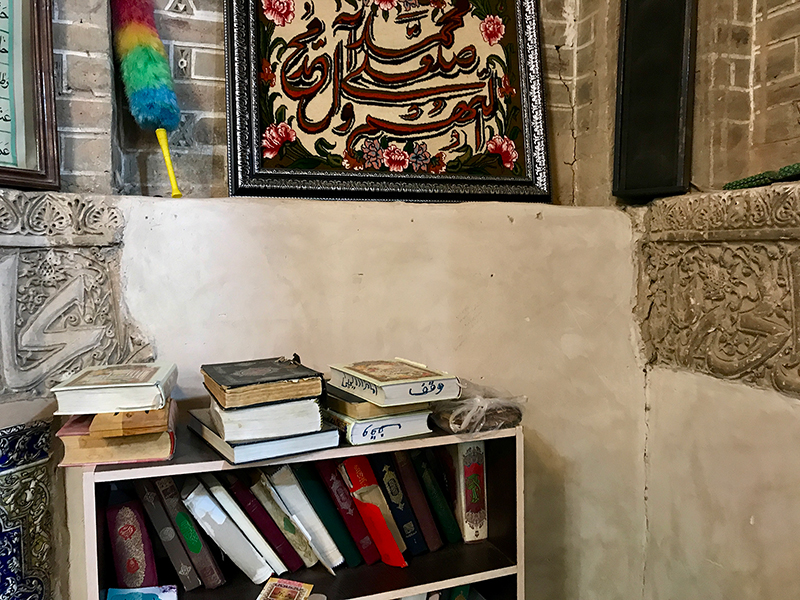

Like these large shrines, the Emamzadeh Yahya has also been the recipient of gifts of all kinds over the centuries. A wooden door endowed to the tomb in 971/1563 appears to have also been a finely crafted work of functional art and was likewise inscribed with a warning against its theft that was ultimately ineffective (no. 15). The only known image of the door was reproduced in a 1915 catalog of its sale in New York, but we hope its inclusion here might spark an identification. As a living sacred site, the shrine continues to receive endowments, including the current zarih (no. 5), books on the shelves, and pilgrimage texts (figs. 11–12).

Like a museum, a shrine must care for its collection through activities like inventorying, periodic cleaning and upkeep, and storage management. These tasks are the purview of its caretakers, the exact makeup of which again depends on the size, location, and resources of the site.8 Like museum curators, caretakers also decide what to display and what to store, and these choices can shift depending on the climate, the individual or institution in charge, the rarity and significance of the given thing, and whether or not it is a holiday in the Islamic or Iranian calendar or a relatively ordinary day.

When Myron Bement Smith took his photograph looking toward the screened cenotaph of Emamzadeh Yahya in 1958, the shrine was the main ritual space of the Kangarlu tribes and Kohneh Gel neighborhood. The large ʿalamat (ceremonial standard with multiple vertical finials) propped up against the screen appears to have been stored inside the tomb through the 1970s. Once the hosayniyeh was built to the south of the complex, just off the site of Yahya b. ʿAli’s martyrdom (qatlgah), this large hall became the place to store the community’s ceremonial standards and associated ritual objects, including banners (parcham) and drums.

Examples of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s historical material culture are still preserved at the site. Some of this important heritage, including a portion of the wooden screen used in the tomb for at least one hundred years, was included in a 1399 Sh/2020 photo article, a form of visual documentation that contributes to the shrine’s archive.9 Other still functional materials are ‘rotated out’ of storage at certain times of the year.10 During the month of Moharram, for example, the tomb is cloaked with textiles on the outside and inside (fig. 13). On temperate spring days, carpets dress the eyvan leading into the tomb and provide a suitable surface for communal meals (nazri) and taking in the courtyard.

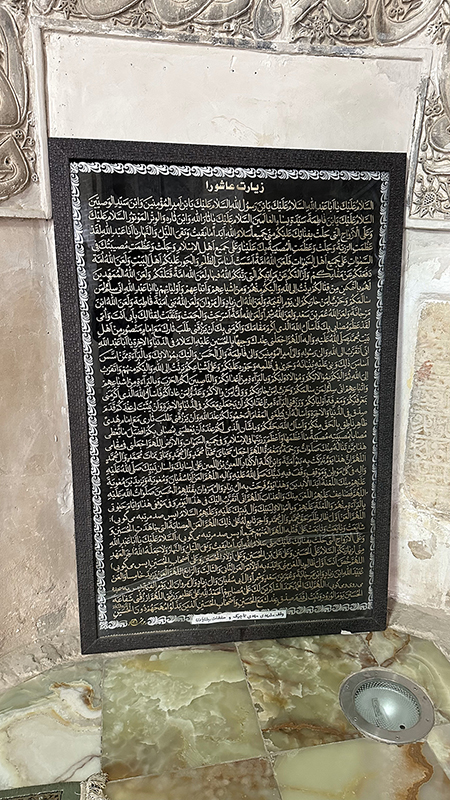

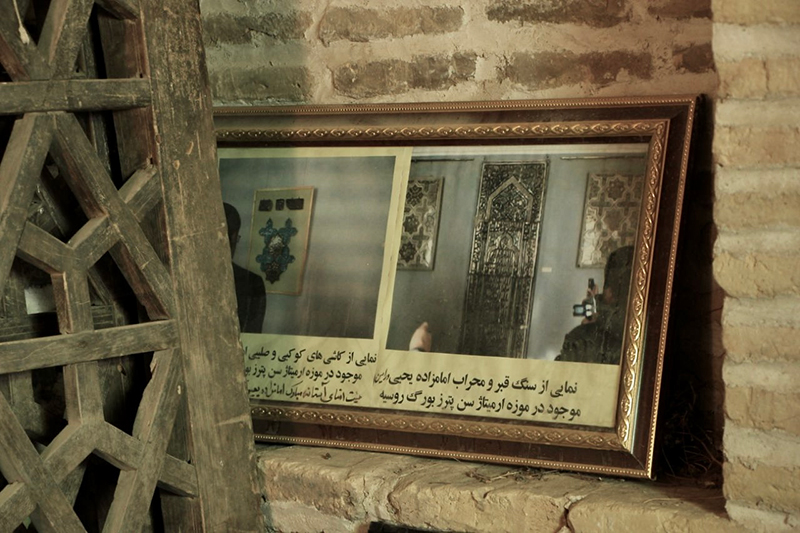

A prominent space inside the tomb for the display of meaningful materials is the void left behind after the plunder of its 663/1265 luster mihrab. This large white surface has been in place since at least April 1958 (recall Smith’s photograph) and provides a suitable zone for ‘rotating displays,’ to again use museum speak. The collage of images below shows some of the materials that have been mounted in this space over the last two decades, all of which served distinct needs (fig. 14). These visuals have included portraits of the Emams, a genealogy of Yahya b. ʿAli (fig. 16 in this article), a collage related to the tomb’s luster tiles and nineteenth-century perception, banners specific to Moharram (fig. 21 in this article), and verses of religious poetry.

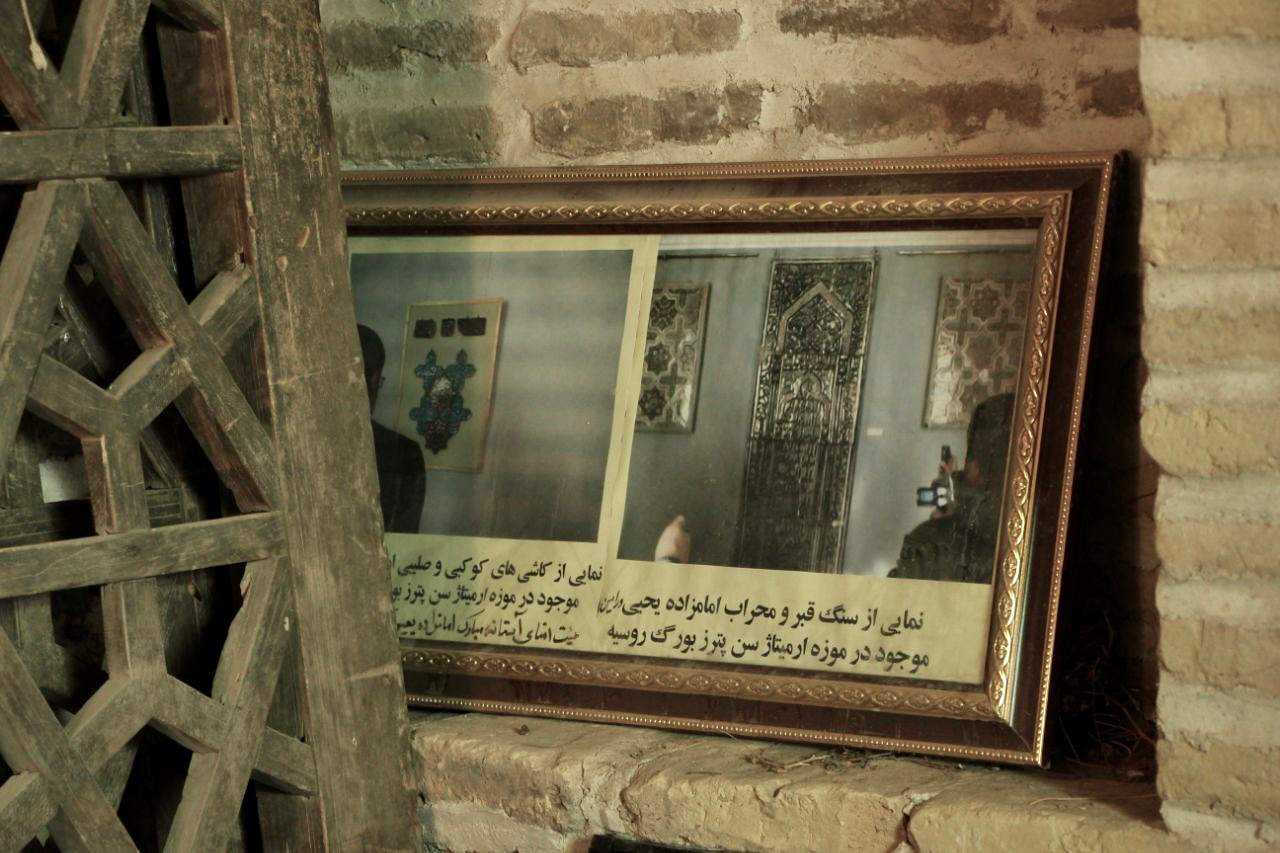

The collage mixing prints from Jane Dieulafoy’s La Perse (1887) and photographs of the tomb’s luster tiles on display in the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg is preserved throughout the site in different iterations (fig. 15). The large didactic dated Mordad 1399 Sh/August 2020 that currently faces the visitor upon entrance provides information on the saint (his genealogy and martyrdom) and the site (its year of registration and stolen materials, including tiles in the Hermitage) (fig. 16).

The Checklist

This checklist is divided into five thematic sections with some fluid overlap. The Tomb explores the most sacred space within any tomb chamber: the tomb of the saint. The first five entries are devoted to the zarih, one of the most commonly refurbished or replaced elements given its importance and high volume of touch. The musealized zarih of Emam Reza (no. 1) is an interesting example of a display that hints at its original sacred context: notice the green lighting and rectangular mock cenotaph. The second five entries consider the adornment of the zarih and the materials preserved inside. The tombstone of Fath ʿAli Shah (no. 10) is included at the end of the section for several reasons: it is a reminder of the fact that some large shrines house the tomb chambers of rulers and elites wishing to be buried near the saint; this shah was a major patron of tombs of the Emams; and this stone panel is an example of internal transfer to the shrine’s museum.

Architectural Features and Furnishings considers fixed and portable elements found in many tombs and shrines that served functional needs while also facilitating the sacred experience. Mirrorwork and windows heightened the senses, tiles cloaked the space in Qur’anic verses, doors served as sacred thresholds to be touched and kissed, basins provided water, and mihrabs indicated the qibla (fig. 17). When choosing the luster tiles for this section, I had many options but decided to favor the mihrabs once in the tomb of Emam Reza (no. 16), given their significance as the earliest known luster mihrabs and transfer from the tomb to the shrine museum.11 When it came to star and cross tiles attributed to the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya, I favored lesser-known collections (no. 17, 18) and examples with Persian verses (no. 19). The latter remain an open question: Were they indeed from the Emamzadeh Yahya? Did the tomb’s dado potentially mix mostly Qur’anic verses with some Persian ones? This is possible, and we can remember that Persian poetry infused the walls in other ways, namely, the inscriptions (yadegari) written by pilgrims over the centuries (see Shahidi Marnani’s essay).

Sacred Atmosphere considers the natural wonders, soundscapes, and visuals that contribute further sacred ambiance to shrines. The entry on sound (no. 25) adds a critical auditory dimension, and the soundscapes considered, belonging to mostly larger shrines, provide a useful contrast to those of the Emamzadeh Yahya, as recorded in Maryam Rafeienezhad’s essay.12 Some of the popular visual materials in this section were relatively affordable and could have been purchased at shrines to bring home as souvenirs (no. 30) or given to an emamzadeh in gratitude for a wish fulfilled and mediated by the Emamzadeh, hence part of the reciprocal process known as nazr kardan (to vow or dedicate). The bismillah bird (no. 27) in the Wereldmuseum in Amsterdam is of the type of image known to have once hung on the screen shielding Emamzadeh Yahya’s cenotaph, as documented in Smith’s 1958 photograph, and may have been a personal votive offering, or nazri.13 Many of the works in this section are figural portraits that inspire reverence of the holy family and/or remembrance of the tragedy of Karbala (no. 29).

Personal Piety explores the physical things that are directly used, read, touched, and held by the pilgrim during ziyarat. The objects are small and portable, and most are preserved in ethnographic collections. The mirror case from the Victoria and Albert Museum offers a good contrast to the example in the Wereldmuseum (nos. 37, 38). While these depictions of Emam ʿAli were intended for close personal contemplation, as illuminated in the filmed entry, comparable images would have been displayed in shrines as framed images and even painted on the walls (circle back to no. 30). The entry on curator-ethnologist Teresa Battesti (d. 2015) offers an important window into collecting and her relatively untapped archival photographs (no. 36).14 The last three entries devoted to the Shrine of Emam Reza in Mashhad underscore the pervasiveness of the Emam’s iconography, especially as the protector of the gazelles (nos. 40, 42). We can again loop back to the Emamzadeh Yahya, which a decade ago (2013) displayed a large carpet with this imagery above the entrance of the tomb (fig. 18). Much like “Asr-e Ashura” (Evening of Ashura) by Mahmoud Farshchian (no. 29), this composition was frequently replicated across media, including posters.

Collective Practices is perhaps the most lively section of the checklist and focuses on the collective traditions that bind people to shrines, including the visiting of graves of loved ones on the last day of the year (no. 43) and the sharing of communal food (nazri) (no. 44). While many of the materials pertain directly to Karbala and related performances and processions between the emamzadeh, hosayniyeh, and street, the entry on coffeehouse painting (no. 45) illustrates how these stories entered other public spaces and were sometimes combined with tales about the heroes of the Persian literary canon. Like the bismillah bird (no. 27), the calligraphic finial (tigheh) (no. 51) is another example of a musealized object that can be directly tied to the Emamzadeh Yahya, specifically, the ʿalamat with a dozen such finials once kept inside the tomb. Closing the checklist for now, this now isolated and highly decontextualized ‘object’ raises many questions about how the ritual objects, material supports (things that mediate/facilitate ziyarat), furnishings, and architectural revetments of Iranian Shiʿi shrines, and many other sacred spaces for that matter, reach museums and the implications of their objectification and secularization. It also returns us to the Getty’s “Lumen” exhibition and the problem of the fragment.

***

How to use this checklist: The checklist is divided into five thematic sections of about ten things (or experiences) each. The collection of thumbnails in each section allows you to appreciate the full contents, and clicking on any image leads you into the catalog entry. All entries open with a ‘tombstone,’ which is museum speak for the object’s salient information. The entries vary in length and style, and this variety has been encouraged. Some entries consider things/experiences that are discussed in many other areas of the exhibition (for example, no. 33). In such cases, the page simply provides related links. A few entries are in progress and coming soon.

Citation: Keelan Overton, “Introduction to the Checklist: A Curatorial Experiment.” Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.

Notes

- Collins and Turner, eds., Lumen: The Art and Science of Light, 800–1600, nos. 108–113. The catalog also illustrated (fig. 51) the three-tiled panel that likely sat on the top of ʿAbd al-Samad’s cenotaph. See Blair’s essay here, fig. 14. ↩

- See my earlier discussion in “Framing, Performing, Forgetting.” ↩

- These pointed critiques aside, the exhibition was an enjoyable and informative global survey of light with many merits, including creative installations and some important loans of ‘Islamic art.’ ↩

- A useful resource on Iranian tombs and emamzadehs are the three volumes of the Ganjnameh, “Emamzadehs and Mausoleums,” vols. 10–13. Emamzadehs in Tehran are included in volume 3. ↩

- I had hoped to include some more filmed entries, but some plans fell through. ↩

- Parsapajouh, « La châsse de l’imam Husayn, » 47. ↩

- For exhibition catalogs that consider gifts to large shrines, see Canby, ed., Shah ʿAbbas and Komaroff, ed. Gifts of the Sultan. In some instances of royal gifting, entire collections of works of art, including manuscripts and porcelains, were endowed to shrines (see no. 8 here). ↩

- These roles can include the manager of endowments, motevalli (main supervisor of the shrine), khadem (servant or custodian), and a board of trustees. ↩

- IRNA, “The tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya is a historical attraction,” December 19, 2020. The title of a more recent newspaper article likens the Emamzadeh Yahya to a museum (امامزادهای شبیه موزه). This long article mentions its many stolen materials, including tiles (the luster mihrab is incorrectly noted as being in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York). Hamshahri Online, “An emamzadeh similar to a museum,” May 20, 2023. ↩

- A ‘rotation’ is museum speak for the changing of objects on display in the galleries, often light-sensitive materials like works on paper and textiles. ↩

- For further information on these two mihrabs, and a third kept in the adjacent mosque, see Kafili, “The Luster Mihrabs.” ↩

- For a recent volume on Shiʿi material and sensorial traditions beyond Iran and beyond Karbala (that is, beyond the prevailing emphasis on the large transnational shrines) that came to my attention near the end of this project, and which includes several essays on sound, see Marei, Shanneik, Funke, eds., Beyond Karbala. ↩

- Thank you to Mirjam Shatanawi for alerting me to the Wereldmuseum piece. On votive images, see Flaskerud, “The Votive Image in Iranian Shi‘ism.” These gifts can be variously labeled taqdimi (offering), hediyeh (gift), or waqf, and sometimes in combination. ↩

- For a case of experimental collecting conducted for an exhibition on the hajj, see this talk by Luitgard Mols (“Collecting Hajj and Mecca items”), in which she discusses the 2013–14 exhibition “Longing for Mecca: The Pilgrim’s Journey,” held at the Rijksmuseum Volkenkunde in Leiden. ↩

Bibliography

This bibliography includes a small selection of resources on Twelver Shiʿism. For other bibliographies and discussions, please see the contributions of Amini, Parsapajouh, Khamehyar, Rafeienezhad, Shahidi Marnani, and Rahmani.

- ایرنا. «بقعه امامزاده یحیی (ع) ورامین جاذبهای تاریخی، میراثی گرانقدر از گذشتگان.» ۲۹ آذر ۱۳۹۹ش. [IRNA, “The Tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin is a historical attraction, precious heritage from the past.” December 19, 2020.] [IRNA]

- کفیلی، حشمت. «محرابهای زرینفام حرم مطهر در موزه مرکزی آستان قدس رضوی.» در: شمسه، شمارهی ۱۸ (بهار ۱۳۹۲): ۱- ۲۸. [Kafili, Heshmat. “Luster mihrabs of the Holy Shrine in the Central Museum of Astan Quds Razavi.” Shamseh 18 (2013): 1–28.] [Shamseh]

- همشهری آنلاین. «امامزادهای شبیه موزه.» ۳۰ اردیبهشت ۱۴۰۲ ش. [Hamshahri Online, “An emamzadeh similar to a museum.” 30 Ordibehesht 1402/20 May 2023.] [Hamshahri Online]

- Allan, James W. The Art and Architecture of Twelver Shiʻism: Iraq, Iran and the Indian Sub-Continent. London: Azimuth Editions, 2012. [WorldCat]

- Canby, Sheila R., ed. Shah ʿAbbas: The Remaking of Iran. London: British Museum Press, 2009. [Internet Archive] [WorldCat]

- Collinet, Annabelle. “Performance Objects of Muḥarram in Iran: A Story through Steel.” Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World 1, 1–2 (2021): 226–47. [Brill]

- Collins, Kristen M., and Nancy Turner, eds. Lumen: The Art and Science of Light, 800-1600. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2024. [Muse]

- Flaskerud, Ingvild. Visualizing Belief and Piety in Iranian Shiism. London: Continuum, 2010. [WorldCat]

- Flaskerud, Ingvild. “The Votive Image in Iranian Shi’ism.” In The Art and Material Culture of Iranian Shiism: Iconography and Religious Devotion in Shii Islam, edited by Pedram Khosronejad, 161–78. London: I.B. Tauris, 2014. [WorldCat]

- Gruber, Christiane. “Nazr Necessities: Votive Practices and Objects in Iranian Muharram Ceremonies.” In Ex Voto: Votive Giving Across Cultures, edited by Ittai Weinryb, 246–75. Bard Graduate Center, 2016. [Academia]

- Haji-Qassemi, Kambiz, ed. Ganjnameh: Cyclopaedia of Iranian Islamic Architecture, vol. 13, Emamzadehs and Mausoleums (Part III). Tehran: Shahid Beheshti University Press, 2010. [WorldCat] [the volume with the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin]

- Komaroff, Linda, ed. Gifts of the Sultan: The Arts of Giving at the Islamic Courts. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2011. [Internet Archive] [WorldCat]

- Marei, Fouad Gehad, Yafa Shanneik, and Christian Funke, eds. Beyond Karbala: New Approaches to Shi’i Materiality and Material Religion. Leiden: Brill, 2024. [WorldCat]

- Newid, Mehr Ali. Der schiitische Islam in Bildern: Rituale und Heilige. München: Edition Avicenna, 2006. [WorldCat]

- Overton, Keelan. “Framing, Performing, Forgetting: “The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin.” Platform, September 12, 2022, https://www.platformspace.net/home/framing-performing-forgetting-the-emamzadeh-yahya-at-varamin.

- Parsapajouh, Sepideh. « La châsse de l’imam Husayn. Fabrique et parcours politique d’un objet religieux de Qom à Karbala. » Archives des sciences sociales des religions. La force des objets. Matières à expériences 174 (avril–juin 2016): 49–74. [Open Edition Journals]

- Parsapajouh, Sepideh. “The Topography of Corporal Relics in Twelver Shiʿism. Some Anthropological Reflections on the Places of Ziyāra.” Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World 1, 1–2 (2020): 199–225. [Brill]