43Sabzeh (sprouted wheat grass)

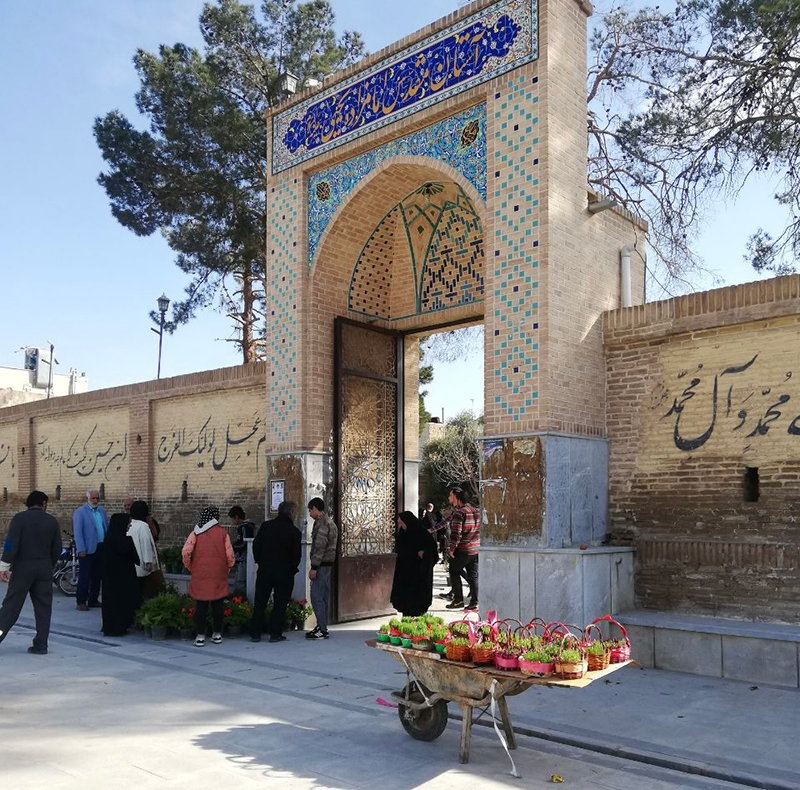

Iran, each spring, on the occasion of Nowruz This photograph: Wheelbarrow with sabzeh in front of the Emamzadeh Yahya, Varamin Photograph by Maryam Rafeienezhad, Esfand 1402/March 2024

Spring marks the beginning of a new year for many cultures including Iranians. During this time, nature starts transitioning from winter blues to warmer temperatures, greener trees, and colorful blossoms. Longer days encourage people to spend more time with loved ones enjoying the crisp spring breeze as nature renews. To commemorate new beginnings through nature, Iranians celebrate Nowruz (نوروز, literally ‘new day’) alongside loved ones both past and present.

Iranians start preparing for Nowruz from mid-March by spring cleaning, buying new clothes, and planning their Haft-Sin (هَفت سین) (figs. 1–2). This spread is comprised of seven items derived from nature starting with the letter sin (س, s) in Persian, each of which signifies a concept related to rebirth and prosperity. The seven items include, with some variation: sib (سیب, apple), sabzeh (سَبزه, sprouted wheat grass), samanu (سَمَنو, sweet wheat pudding), sir (سیر, garlic), sumaq (سُماق, sumac), senjed (سِنجد, sweet dried fruit), and serkeh (سِرکه, vinegar). For most families, sabzeh is the centerpiece of the Haft-Sin table.

While some Iranians opt to purchase ready-made sabzeh from their local corner store or Nowruz bazaars, others grow their own (figs. 3–4). Growing sabzeh requires preparation as some seeds need more time to sprout. Traditionally, sabzeh is made with wheat, but other seeds such as mung beans, lentils, and chia seeds can also be used. Once the sabzeh has sprouted, it is placed in decorative earthenware on the Haft-Sin and adorned with ribbons. It remains there during the two-week Nowruz celebrations as families host visiting relatives.

At the end of its life cycle, when it is usually overgrown, sabzeh is returned to nature on the thirteenth day of the new year or Sizdeh-be-dar (سیزده به در). Officially the last day of the Nowruz celebrations, Iranians spend this day enjoying an outdoor picnic with family and friends, thus escaping the superstition that staying indoors on the thirteenth day of the new year will bring misfortune. The day’s menu usually includes different types of kebabs, ash reshteh (آش رِشته, a thick soup made with noodles, beans, and herbs), lettuce with sekanjabin (سِکَنجبین, a sweet and sour syrup made with sugar and vinegar), and other shareable dishes. At the end of the picnic, sabzeh is left behind in nature to decompose and return to the cycle of regrowth.

In tune with the communal culture of the country, Iranians spend Nowruz visiting the elderly and extended family to wish them well for the upcoming year. During the first days, the younger generation honors their elders by visiting them at their homes. Even though this gathering is short in duration, the hospitality of the host is on full display. The generous hosts spoil the guests with ʿeidi (عِیدی, monetary gift for children), confectionary, and freshly made tea. It is worth noting that the visit will be reciprocated during the Nowruz holidays.

The tradition of visitation also extends to visiting the burial place of loved ones in cemeteries, holy shrines, and local emamzadehs, and it is customary to visit the deceased on the last Thursday before the beginning of the new year (figs. 5–6). To share the rituals of a new year, family members bring flowers (in some case an extra sabzeh), refresh the tombstone with water (or rosewater), and distribute food offerings as blessings for the passed soul. It is not uncommon for families to exchange condolences and offer their prayers for the deceased, but the overall sentiment of such visits is celebratory. The occasion is considered “a celebration of life and a good future, not of death and the past” (Loeffler and Freidl 2022, p. 33).

Nowruz is not only about celebrating renewal but also about remembering the natural cycle of life. The occasion reinforces the importance of family, community, and nature. That includes picking elements from nature for the Haft-Sin table, growing sabzeh, and spending time with loved ones. The celebration of Nowruz over 3,000 years is a testament to the importance of these rituals in strengthening our communal connection to nature and life.

Sources:

- Loeffler, Reinhold L. and Erika Friedl. “Mourning at New Year’s Day (Nowruz): Cultural Practice against Ideology.” Anthropology of the Middle East 17, 1 (2022): 19–34. [Berghahn]

- Sociedad Espanola de Iranologia – SEI, “How do Iranians Celebrate Nowruz,” February 2022, https://iranologia.es/en/how-do-iranians-celebrate-nowruz/.

Citation: Mehrnaz Fazel, “Sabzeh (sprouted wheat grass).” Catalog entry in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.