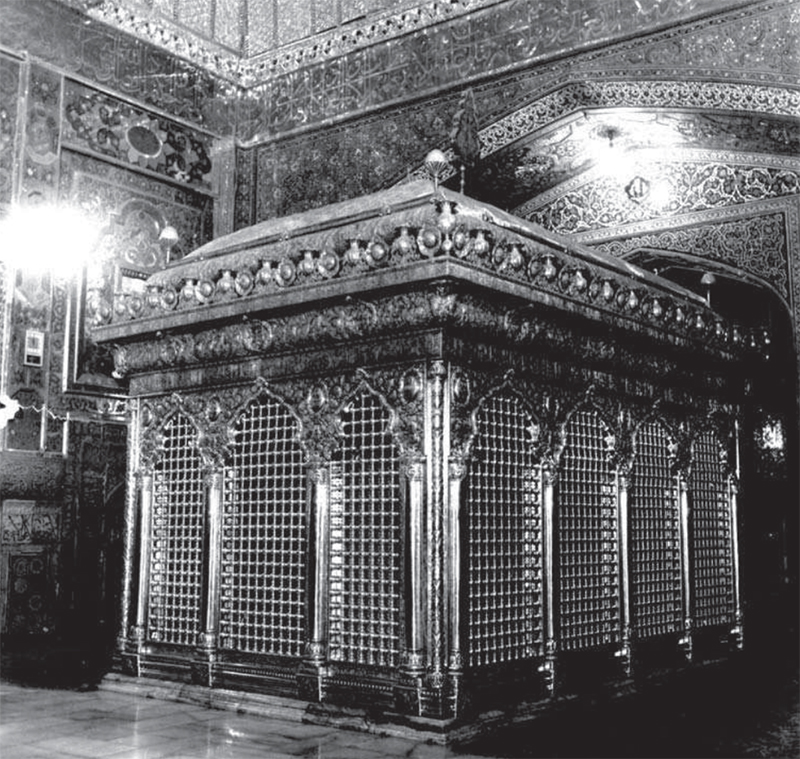

1Zarih (screen) of Emam Reza, known as Zarih-e shir o shekar (The Lion and Sugar Zarih), for his tomb at Mashhad

Iran, dated Shaʿban 1379/February 1960 Designed by Mohammad Taqi Zoufan Esfahani, under the supervision of Seyyed Abolhasan Hafezian Calligraphy by Habibollah Fazaeli, Mohammad Hassan Rizvan, and Ahmad Zanjan Silver, gold, iron, copper, wood, brass, casting, electroplating, hammering, brushwork, inlay work, and enameling 13.1 × 11.8 × 12.8 ft. (4 × 3.6 × 3.9 m); 7 tons (14,000 lbs) Astan-e Qods-e Razavi Museum, Mashhad, no. 9205112 Photograph by Reza Daftarian, 2024

While Shiʿi Muslims, like their Sunni counterparts, consider hajj (the pilgrimage to the Kaba in Mecca) to be religiously obligatory (vajib), visiting the shrines of the Emams and their descendants is not a religious obligation. Nevertheless, such pilgrimages within Shiʿi Islam have in practice reached a status that exceeds being simply recommended (mustahhab). Indeed, one of the paramount distinguishing features of Twelver Shiʿi ideology is the prodigious value afforded to the visitation (ziyarat) of these sites. Given the blessings (baraka) vested onto the Emams, and by extension emamzadehs, visitations to their tombs are popularly believed to have the ability to enact miracles (ke ramat), or “events that cannot be caused by human abilities or natural agency” (Betteridge 1992, p. 195). As such, the tomb-shrines of Emams and emamzadehs are fittingly seen as thresholds into sacred realms that are imbued with blessings and powers.

The latticed structure that encloses a cenotaph—the zarih—carries profound symbolic significance during pilgrimage and serves as a tangible representation of the spiritual presence of the revered entombed figure. Upon prostrating at the threshold of the tomb chamber (haram) and pronouncing their submission to God, pilgrims perform a sequence of devotional acts to demonstrate their earnest piety before and after making their requests to the Emam. If one is lucky enough to make it through the sea of bodies in a busy tomb like that of Emam Reza and reach the zarih, it is customary to touch, rub, and even kiss the screen as an expression of respect for the Emam and to absorb the blessings (baraka) that radiates from his place of burial (fig. 1). By becoming physically closer to the Emam, the pilgrim becomes spiritually closer to him and God.

This zarih, known as ‘The Lion and Sugar Zarih’ (ضريح شير و شکر), was completed under the stewardship of Seyyed Fakhr al-Din Shadman (d. 1967), a custodian of Astan-e Qods-e Razavi (the Shrine of Emam Reza) and statesman during the reign of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (r. 1941–79). It functioned as the zarih of Emam Reza from 1960 to 1995 (fig. 2).

This zarih includes fourteen filigreed apertures separated by golden roundels bearing the names of the Fourteen Infallibles (the Prophet, his daughter Fatemeh, and the Twelve Emams). Its foundation is meticulously clad in embossed silver sheets that served as a canvas upon which gilded sheets were then applied, each intricately etched with elaborate patterns comprised of polygons and vegetal motifs (fig. 3). These gold and silver elements were acquired through the melting of various items from the treasury of the shrine. Originally atop each corner of the zarih were ovoid orbs made of turquoise (see fig. 2).

Circumscribing the upper edges of the zarih are two perpendicular Qurʾanic inscriptions in thuluth (sols) bearing verses from sura Ya Sin, often referred to as the ‘Heart of the Qurʾan,’ and sura al-Insan. The former articulates the central tenets of Islam regarding monotheism, prophethood, and eschatology, while the latter deals with the rewards of piety. Other important inscriptions include the ninety-nine names of God, each of which refers to an attribute of the Divine, and hadiths (traditions) that emphasize the status and virtues of Emam Reza.

Based on new scientific research carried out at the shrine, it is possible to gain deeper insight into how these inscriptions were actually produced. According to restoration experts, they were initially written to scale on paper by the calligrapher before a goldsmith applied a powder derived from lapis lazuli to transfer them onto a gilded sheet placed on a frame filled with soda ash. Finally, an assortment of engraving tools was employed to chisel out the negative spaces (Salehi et al 1395 Sh/2016).

The zarih-e shir o shekar is currently on display in the shrine’s Central Museum (map). Due to its dynamic setting in the middle of a sky-lighted atrium, one is able to circumambulate it and even view it from above from a second-story balcony. Part of the zarih is draped in a velvet brocade embroidered with the name of the Prophet’s family (ahl al-bayt), Emam Reza, and a list of his miracles (see no. 40). Such brocades were customarily produced annually and draped over the zarih (fig. 4).

Sources:

- Betteridge, Anne. “Specialists in Miraculous Action: Some Shrines in Shiraz.” In Sacred Journeys : The Anthropology of Pilgrimage, edited by Alan Morinis, 189–209. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1992. [WorldCat]

- Ghasabian, Mohammad Reza. “Tārīkhcheh-ye Żarīḥ-e Moṭahar-e Emām Reżā (AS).” Meshkat 68/69 (1379 Sh/2000): 251–33. [Noormags.ir]

- Muʾtaman, ʿAli. Rāhnamā ya Tārīkh va Towṣīf-e Darbār-e Velāyatmadār-e Rażavī. Mashhad: Astan-e Qods Razavi, 1348 Sh/1969. [Lib.ir]

- Saheli, Esra, Abol-Qasem Dadvar, and Mehdi Makinezhad. “Katībeh-hā-ye Żarīḥ-e Shīr o Shekar Emām Reżā (pbuh): Manẓar-e Mabāni-ye Eʿteghādī-ye Shīʿeh.” Faslnameh-ye Elmi, Pazhuheshi-ye Negareh 40 (1395 Sh/2016): 16–31. [Ensani.ir]

Citation: Reza Daftarian, “Zarih (screen) of Emam Reza, known as Zarih-e shir o shekar (The Lion and Sugar Zarih), for his tomb at Mashhad.” Catalog entry in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.