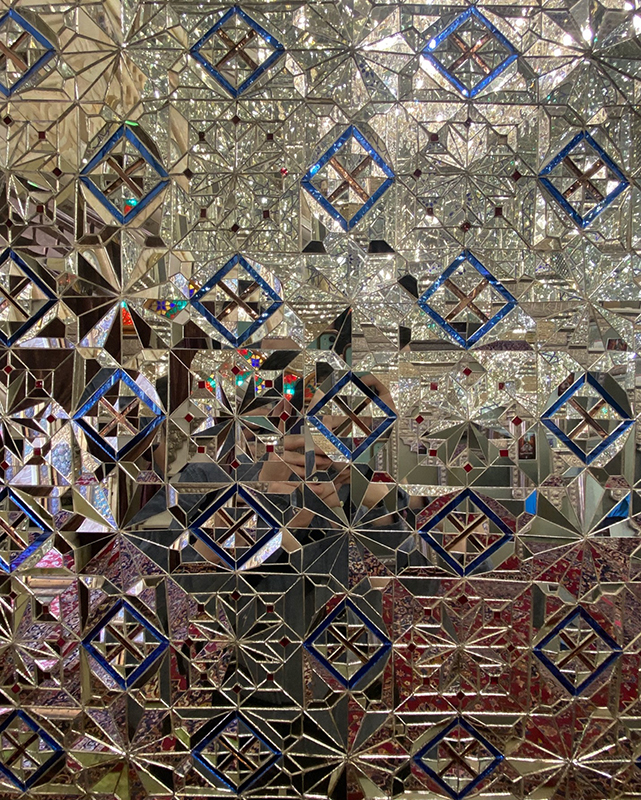

12Ayeneh-kari (mirror-work) in the tomb of Shah Cheragh at Shiraz

Shrine of Shah Cheragh, Shiraz 12th century onward Mirror-work: Qajar period, 1883–onwards Glass, crystal, brass Photograph by Reza Daftarian, 2024

Shah Cheragh, located in the heart of Shiraz (map), is one of the most significant pilgrimage sites in Iran. The origin of the name ‘Shah Cheragh’ (King of the Light) is attributed to the discovery of a radiant tomb in the early twelfth century. According to tradition, the tomb belonged to Ahmad ibn Musa (d. ca. 819), the brother of Emam Reza and Fatemeh Maʿsumeh and son of Emam Musa Kazem. Ahmad ibn Musa is believed to have been killed by Abbasid soldiers while en route from Medina to Khorasan, and after his martyrdom in the early ninth century, his burial site remained hidden for more than a century.

The story of the shrine’s rediscovery is integral to its identity. It is said that a miraculous light emitted from the burial site led to its discovery by a pious man. This light, considered a divine sign, gave the shrine its name and established it as a place of spiritual significance. Over the centuries, the shrine has undergone numerous renovations and expansions, reflecting the devotion of various rulers and the continuing reverence of the faithful (fig. 1). At present, the sacred complex is comprised of several indoor and outdoor spaces. The most important is the central domed tomb chamber (gonbad-khaneh) of Ahmad ibn Musa, which is enclosed by four extended shah-neshins (literally, ‘seat of the shah’), or vaulted alcoves. The tomb’s exterior has two minarets and a colonnaded veranda facing a large courtyard (fig. 2). The complex also includes a congressional mosque, museum, madrasa (religious seminary), library, and the shrine of Seyyed Mir Mohammad, Ahmad ibn Musa’s brother.

One of the most striking features of Shah Cheragh is its profuse employment of mirror-work (ayeneh-kari), a traditional Persian form of architectural revetment wherein small pieces of mirror and colored glass are cut and meticulously arranged atop of surfaces according to various designs in order to create dazzling, reflective spaces (fig. 3). When ayeneh-kari first emerged in seventeenth-century Iran, it was solely reserved for select surfaces of the talar (columned porch) palaces of Safavid Esfahan. Within a span of only a century, however, ayeneh-kari transformed from being a peripheral component of the decorative program to becoming the preeminent element within Shiʿi shrines. While the addition of ayeneh-kari to these holy structures is believed to have begun during the later Safavid (1501–1736), Afsharid (1736–96), and Zand (1751–94) periods, it was only under the Qajars (1789–1925) that it became a principal element of architectural programs.

Upon entering the tomb (haram) of Shah Cheragh, one is transported into what feels like a different universe. The ayeneh-kari adorning its walls and monumental muqarnas dome is transformed from a static form into a dynamic spectacle (figs. 3–5). The three-dimensionality of the muqarnas, in tandem with the grandiose Qajar-era chandelier suspended from the center of the space, activates the sensorial properties of the ayeneh-kari. With rays of light reflected and refracted, images fractured and dissolved, and space in perpetual motion, the haram is nothing less than architecture ablaze.

Weighing over three hundred pounds, the multi-tiered chandelier commissioned by Naser al-Din Shah (r. 1831–86) consists of a central brass body with arms extending outwards towards tulip lamps housing dimmed lightbulbs (fig. 6). In his account of the tomb based on his visit in 1883, the Qajar poet Forsat-e Shirazi (d. 1929) waxes lyrical about the lighting fixture: “The year one thousand two hundred and seventy-six [or 1859–60] is when the crystal chandeliers and abundant candles, each containing the essence of light and brightness, illuminated the eyes of the world and the spheres” (Forsat ol-Dowleh Shirazi, p. 445–46). Beyond its melodious poetry and confirmation of the chandelier’s date of installation, this observation reiterates the crucial role of lighting devices in sacred spaces and their interdependent relationship with ayeneh-kari.

One cannot help but feel utterly humbled in the presence of the tomb’s larger-than-life dome, whose majestic ayeneh-kari casts a radiant light upon the visual and symbolic nexus of the sanctuary, the silver zarih (see main image above). This powerful sentiment of humility is further augmented by the actual fragmentation of the mirrors, which through obscuring our own reflection, summon us to lose attachment to our physical selves (fig. 7). In this regard, the ayeneh-kari of shrines like Shah Cheragh entirely destabilizes traditional western connotations of mirrors as emblems of vanity, superficial beauty, and even narcissism.

By activating the embodied nature of ziyarat, mirror-work, perhaps more than any other form of architectural revetment, makes sense in a place like an emamzadeh. To experience a space in which light is diffused at every angle, sounds of mourning and devotion reverberate, and fluid surfaces melt into one is nothing short of disorienting (vid. 1). It is precisely in this haze of disorientation that the fragility of physical existence becomes apparent, and one is reminded of the intimacy of their relationship with the Emams and the Divine. In its ability to aid in making one feel simultaneously small and large, hidden and seen, solitary and convivial, ayeneh-kari ultimately reflects the paradox of ziyarat: it both curtails our connection to our physical forms and strengthens our ties to our spiritual selves.

Video 1. The tomb and its surrounding spaces. Note that the zarih is not directly under the chandelier. Video by Reza Daftarian, 2024.

Sources:

- Daftarian, Reza. “Monumentalizing Monarchy: The Codification of Ayeneh-Kari in Qajar Palaces.” Immediations 21 (forthcoming, 2024).

- Forsat-od-Dowleh Shirazi. Āsār-e ʿAjam, edited by Mansur Rastegar Fasa’i. Tehran: Amir Kabir, 1377 Sh/1998. [Lib.ir]

- Haji-Qassemi, Kambiz, ed. “Shīrāz, Emāmzādeh Seyyed Mīr-Aḥmad (Shāh-e Cherāgh).” In Ganjnāmeh-ye Farhang-e Āsār-e Meʿmāri-ye Eslāmi, 12:230–37. Emāmzadeh-hā va Maghaber (II). Tehran: Markaz-e Asnad va Tahghighat-e Daneshkadeh-ye Meʿmari va Shahrsazi, Daneshgah-e Shahid Beheshti, 1389 Sh/2010. [Lib.ir] [WorldCat]

Citation: Reza Daftarian, “Ayeneh-kari (mirror-work) in the tomb of Shah Cheragh at Shiraz.” Catalog entry in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.