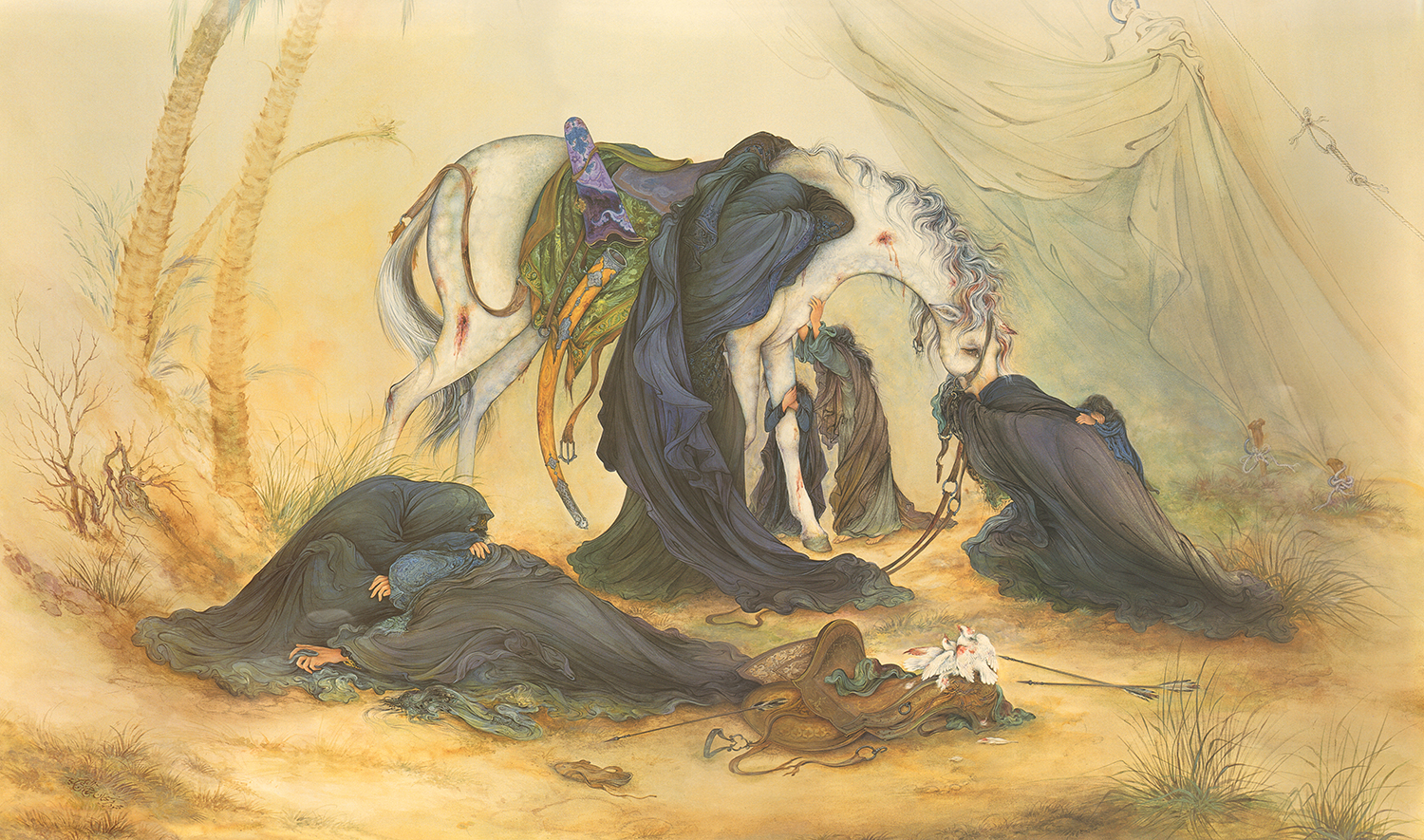

29Asr-e Ashura (Evening of Ashura)

Mahmoud Farshchian (b. 1308 Sh/1930) Iran, 1355 Sh/1976 Acrylic painting on acid-free cardboard 38.5 × 28.7 in. (98 × 73 cm) Astan-e Qods-e Razavi Museum, Mashhad, no. 93081, donated in 1369 Sh/1990 Source: Wikishia

Known as ‘The Evening of Ashura’ (عصر عاشورا, ʿasr-e ʿAshura, henceforth simply “Asr-e Ashura”), this painting depicts the afternoon of 10 Moharram 61/10 October 680, the day when Hosayn b. ʿAli, the third Emam, was martyred in the Battle of Karbala (modern Iraq). Created in 1355 Sh/1976 by the renowned painter and master designer Mahmoud Farshchian, the painting illustrates the moment when Hosayn’s horse Zoljanah (ذوالجناح) returns to the tents of the Ahl-e Beyt (اهل بیت, the family of the Prophet Mohammad) without him. Wearied and wounded, as shown by the two punctures on its body, blood-stained mane, and visible tear in its eye, the horse is surrounded by four women and three children. Zoljanah carries the green ʿabaʾ (a traditional loose-fitting garment) of Hosayn and his empty scabbard, both symbolizing the Emam’s presence in the scene’s center (fig. 1). Although the faces of the women and children are not shown, they are presumably members of Hosayn’s family, probably Zeynab (his sister), Umm-e Kulthum (his sister), Sakineh (his daughter), and others. The outlines of tents flank the figures on the right, while vividly drawn palm trees on the left and sparse desert vegetation in the foreground evoke the geography of the hot and arid desert of Karbala.

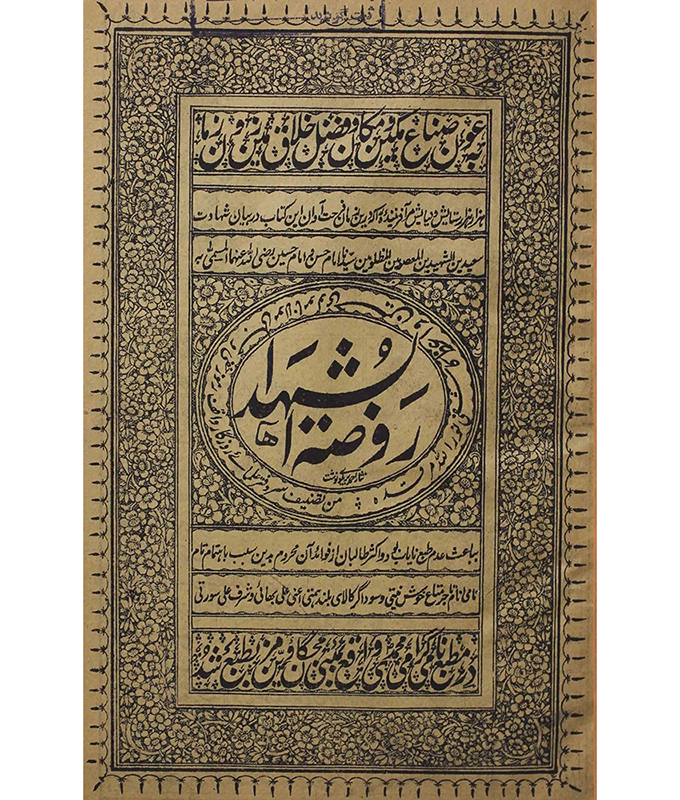

The painting visualizes an episode described in maqtal-namehs (مقتلنامه, written accounts of the martyrdoms of Emams and holy figures) and rowzeh (روضه, lamentations for Emams and holy figures), most notably the Rowzat al-Shohada (روضة الشهدا, Garden of the Martyrs) by Molla Hosayn Vaʿez-e Kashefi (d. 1504) (fig. 2). These writings, which have been recounted from medieval times to the present, are used in contemporary Moharram ceremonies, including rowzeh-khani (sessions when these lamentations are performed). Farshchian later described the inspiration for “Asr-e Ashura” as a conversation with his mother in which she encouraged him to attend rowzeh. Moved by her words, he went to his studio and began painting while mourning for Emam Hosayn. In this video, he explains the moment of inspiration and the creation of the work.

Born and raised in Esfahan, Farshchian was surrounded by various traditional designs and forms (Welch 1991; see also this documentary on his early life) (fig. 3). He was also an acute observer of carpet designs, owing to his father’s job as a carpet dealer. After training in traditional art in Esfahan under the Iranian master designer Eisa Bahadori (d. 1986), Farshchian left to study at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, where he explored European museums. As a result of this background, his style reflects both traditional manuscript painting, known as negargari (نگارگری) in Iran, and western artistic traditions. In “Asr-e Ashura,” his use of color, dispersal of light, swirling and twisting lines, and circular composition are reminiscent of manuscript painting and carpet designs. On the other hand, the layered depictions of drapery and soft gradations of color echo the techniques of western painting. The fusion of these qualities forms his distinct style, sometimes referred to as ‘neo-traditional painting’ (نگارگری جدید, negargari-ye jadid) or ‘the new Persian painting’ (Rezaeinabard 2016).

In 1369 Sh/1990, Farshchian donated “Asr-e Ashura” to the Astan-e Qods-e Razavi Museum, part of the immense shrine complex in Mashhad home to the tomb of Emam Reza (see cat. nos. 16, 21, among others). A large collection of his other works is also permanently exhibited in a museum dedicated to him and inaugurated in 1380 Sh/2001 in one of the buildings of the Saʿdabad Palace in northern Tehran (map) (fig. 4).

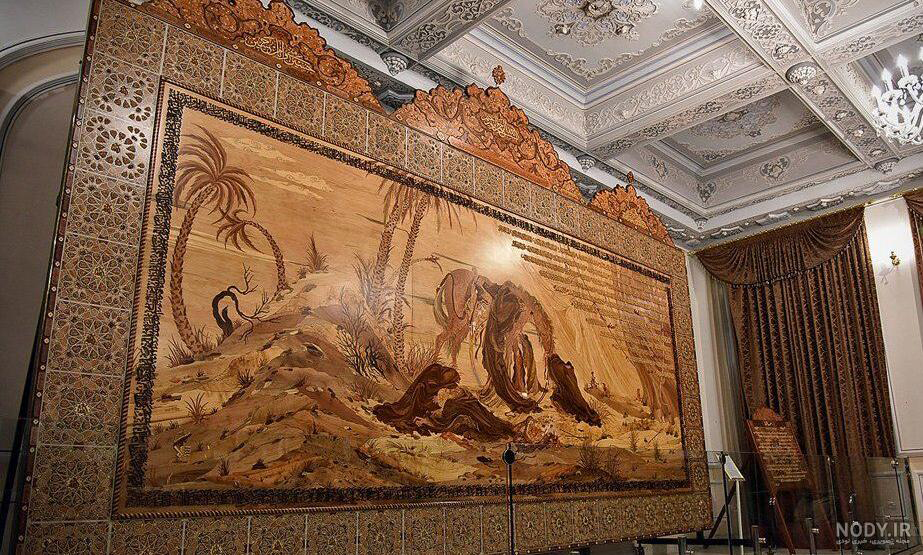

Beyond his original works in these two museums and others worldwide (see this list), Farshchian’s paintings have achieved widespread recognition through reproductions. “Asr-e Ashura,” in particular, has been widely copied, appropriated, and reproduced across various media, particularly during its extended popularity after the Iranian Revolution in 1979. Alongside the original painting, the Astan-e Qods-e Razavi Museum preserves several replicas, including a moʿaragh-kari (معرقکاری, wood inlay) and carpet tableau (تابلو فرش), each labeled with the artist’s name and year of donation (see this link) (fig. 5).

The act of reproduction has made “Asr-e Ashura” more accessible and enabled it to become a versatile presence in many Iranian streetscapes and sacred spaces. Murals in Tehran and Rasht modify and enlarge the painting for visibility in urban space, allowing it to reach a broader audience (fig. 6). Portable versions are also common sights in emamzadehs and other religious spaces. At the Emamzadeh ʿAli in Varamin, a small replica is propped up against the dado of the tomb (fig. 7, vid. 1) (also see City Tour). This gobelin needlepoint tapestry preserves the painting’s outline and composition, making it immediately recognizable to Shiʿi mourners and pilgrims. Posters and reproductions of “Asr-e Ashura” are also part of global collections, including two examples in the V&A Museum in London (ME.6-2011 version A; ME.6-2011 version B). While the proliferation of replicas has popularized Farshchian’s “Asr-e Ashura,” it has inevitably compromised the original work’s details and medium.

Video 1. Interior of the Emamzadeh ʿAli in Varamin. The “Asr-e Ashura” replica is visible at the beginning and end of the video, propped up against the dado. Video by Hamid Abhari, 2024.

The popularity of Farshchian’s “Asr-e Ashura,” both as an original and in many copies, can be attributed to several factors. The artist’s decision to depict the pivotal moment when the news of Hosayn’s martyrdom reaches the camp marks a critical point in the formation of Shiʿi mourning culture. Moreover, Farshchian’s innovative approach to the subject, particularly his inclusion of female figures, distinguishes his work from traditional coffeehouse paintings created by masters such as Hossein Qullar Aqasi (d. 1966) and Mohammad Modabber (d. 1966) (no. 45). This departure from male-centric, heroic narratives of Karbala challenges conventional depictions and offers a fresh perspective on the tragedy (Rahmani 2018). The widespread propagation of martyrdom culture following the Iranian Revolution and war with Iraq (1980–88) further contributed to the dissemination of Karbala iconography. Finally, the painting’s alignment with the revival of traditional Persian painting styles in post-revolutionary Iran helped solidify its place within the national cultural discourse. In 1403 Sh/2024, “Asr-e Ashura” was registered as national heritage. The painting continues to live on as an iconic image and remains a significant part of the collective memory of Shiʿi Muslims.

Sources:

- Calmard, Jean. “Ḏu’l-Janāh” [Zoljanah]. Encyclopædia Iranica, December 15, 1996 (last modified December 1, 2011), https://iranicaonline.org/articles/dul-janah

- Karimi, Fatemeh. “Naqqashī-ye ʿAsr-e ʿAshura sabt-e mellī shod (The ʿAsr-e ʿAshura painting was registered as a national [treasure]).” Mehr News Agency, 23 Tir 1403/13 July 2024, https://www.mehrnews.com/news/6166907/

- Rahmani, Jabbar. “Naqqāshī-ye ʿAsr-e ʿAshura: Zanānegī va tahavvol-e farhangī dar edrāk-e mazhabī dar Iran-e moʿaser (The ʿAsr-e ʿAshura painting: Femininity and the cultural transformation in religious perception in contemporary Iran).” Motāleʿāt-e Jāmeʿeh Shenākhtī (Sociological Studies) 26, 1 (1398 Sh/2018): 91–113. [JSR.UT]

- Rezaeinabard, Amir. “Barresī-ye sabk va āsār-e Maḥmūd Farshchīan: Mabānī nazarī va ʿamalī (An introduction to Mahmoud Farshchian’s style and work: Theoretical and practical foundation).” Mabanī Nazarī Honar-hāye Tajassomī (Visual Arts Theories), 2 (1395 Sh/2016): 23–40. [SID.ir]

- Rolston, Bill. “When Everywhere is Karbala: Murals, Martyrdom and Propaganda in Iran.” Memory Studies 13, 1 (2020): 2–23.

- Shomeili, Abtin (dir.). “Mostanad-e zendegī-nāmeh-ye Ostād Mahmoud Farshchian (Documentary of the life of Master Mahmoud Farshchian),” first broadcasted on Iranian National TV, Mostanad channel, winter 1400 Sh/2021. [watch on Aparat]

- Welch, Stuart Cary. “Introduction,” translated by Hamid Dabbashi. Irānshenāsī (Iranology) 7, 1: (1374 Sh/1995): 171–81. [originally published in Mahmoud Farshchian UNESCO, New York: Homai, 1991] [Noormags]

Citation: Hoda Nedaeifar, “Asr-e Ashura (Evening of Ashura).” Catalog entry in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.