45Naqqashi-ye qahveh-khaneh (coffeehouse painting)

“Journey of Moslem b. Aqil to Kufeh (Kufa)” Signed by Mohammad Modabber (d. 1967), by the order of Mashhadi Safar Eskandariyan Iran, ca. 1950 Oil painting on stretched canvas 80.3 × 99.6 in. (204 × 253 cm) Muzeh-ye Melli-ye Iran (National Museum of Iran), Tehran, 20533 Photograph by Keelan Overton, 2016

Naqqashi-ye qahveh-khaneh (نقاشی قهوهخانه, coffeehouse painting) is a modern genre of narrative painting depicting scenes from Shiʿi martyrology as well as epics and romances from the Persian literary tradition. This painting was carried out by Mohammad Modabber (d. 1967) for Mashhadi Safar Eskandariyan’s coffeehouse located in the Sayyed Esmaʿil Bazaarcheh (map) (Aslani 2022). Modabber made multiple works depicting the story of Moslem b. ʿAqil’s ill-fated journey to Kufeh (Kufa), which ultimately resulted in his death in September 680 and the tragedy of Karbala the following month. Modabber is known to have stated, “Until one, like the honorable Moslem, has had the bitter taste of cowardice and betrayal […] one would not be able to hold a finger of astonishment to one’s lips” (Seyf 1990, p. 112).

The painting is divided into thirty rectangular panels of varying sizes that are numbered consecutively. The narrative begins in the upper right corner with the meeting of Moslem b. ʿAqil with his cousin Emam Hosayn in Mecca and proceeds counterclockwise. The panels wind inwards to the largest central panel, numbered ‘12,’ which may be a symbolic reference to the twelve Shiʿi Emams. The scene represents the climactic moment of Moslem b. ʿAqil’s death at the hands of the Kufan governor ʿObayd Allah b. Ziyad and his men (fig. 1). Having been ambushed, Moslem’s helplessly outnumbered conflict foreshadows a similarly disastrous battle awaiting Emam Hosayn at Karbala. The painting ends the story with a scene of retribution: the public immolation of the man who killed Moslem’s two young innocent sons for a monetary reward offered by ʿObayd Allah b. Ziyad.

Mohammad Modabber and his teacher Hosayn Qullar Aqasi (d. 1966) are viewed as the two great masters of the coffeehouse painting tradition (for biographies of both, see Seyf 1990, p. 23–39 and 43–56). Since the Safavid period (1501–1722), the coffeehouse was an important gathering space for artists, poets, intellectuals, and statesmen. In the month of Moharram, the coffeehouse would host special recitations and reenactments of the events leading up to the martyrdom of Emam Hosayn (Al-e Dawud 1992.)

Coffeehouse painting is grounded in much older traditions of recitation (روضه خوانی, rowzeh-khani) and storytelling (نقالی, naqqali) in Iran and is particularly linked in visual terms with pardehs (پرده, curtains or canvases), portable large-scale paintings that a subset of professional storytellers used to facilitate their performance (fig. 2). The canvas was covered with a white cloth that the storyteller or his storytelling partner would gradually uncover while recounting the tale, pointing to the relevant pictorial figure with his cane (see both the cloth and cane in fig. 2) (Lashkari and Kalantari 2015, p. 253). Coffeehouse paintings also stimulate a similarly dynamic engagement with the painted surface, thanks to their large-scale formats and complex multi-scene compositions. In contrast to pardehs, however, coffeehouse paintings are inscribed with the names of each historical figure and event and hence do not require the verbal activation of the storyteller. These inscriptions are helpful narrative prompts and interpretive entryways for the viewer.

The tragic events of Karbala also found dramatic expression in taʿziyeh (تعزیه), Shiʿi devotional drama that takes place in special buildings called tekiyeh (تکیه) or hosayniyeh (حسینیه) (see cat. nos. 46–47). The practice of decorating the walls of tekiyehs with wall paintings can be traced back to the Tekiyeh Dowlat, the royal amphitheater inaugurated in 1867 in the Golestan Palace (Chelkowski 1989, p. 99–100). A recent example can be seen in the tekiyeh of the Tajrish bazaar in Tehran (figs. 3–4).

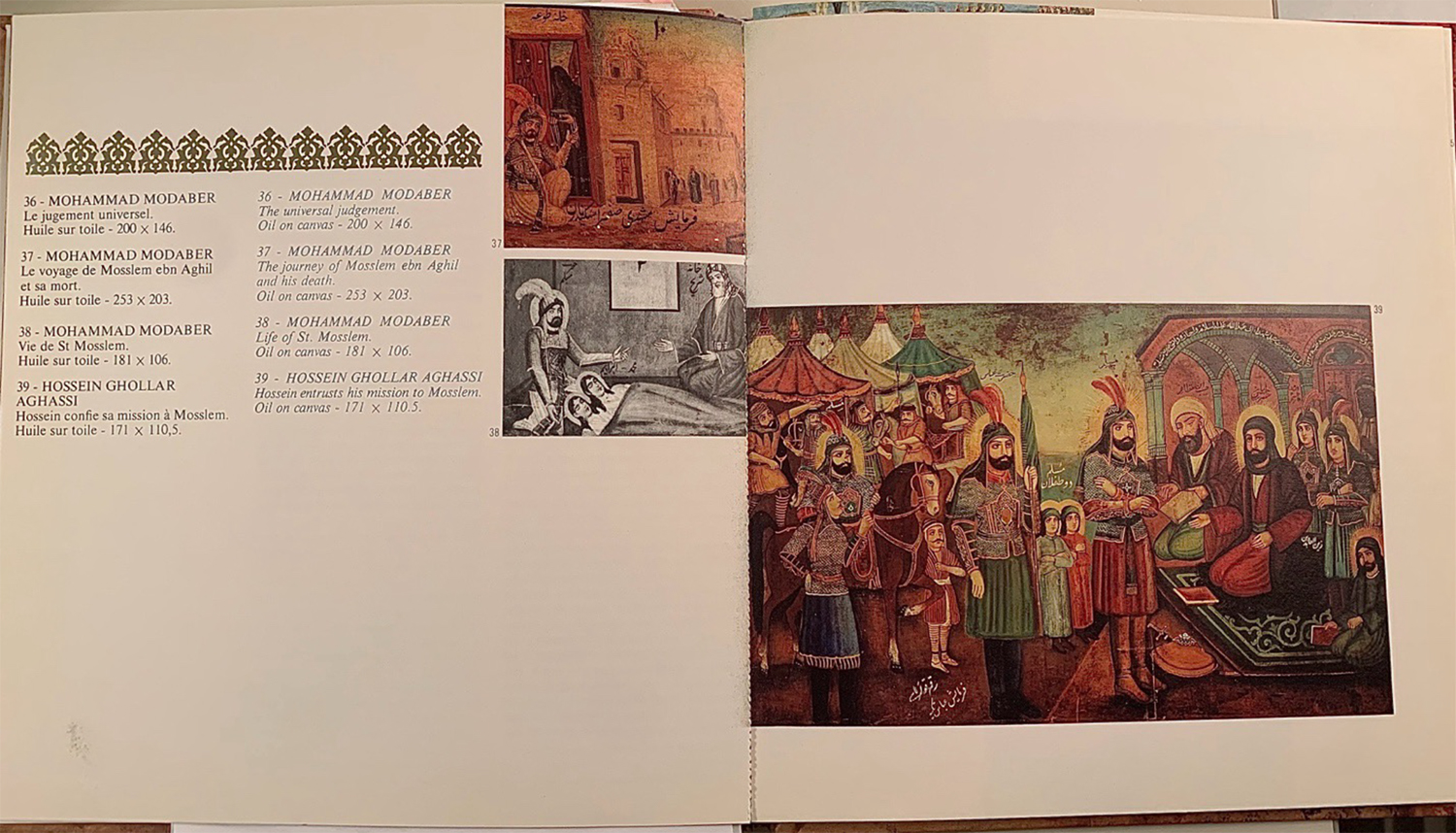

Often described by its makers as khayal-pardazi (خیال پردازی), or dream-work, and noted for its imaginative qualities, coffeehouse painting gained a newfound appreciation during Modabber and Qullar Aqasi’s lifetime (Diba 2013, p. 52). Iranian modernist artists such as Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian (1922–2019) and Marcos Grigorian (1925–2007) were avid collectors of coffeehouse paintings and brought them to the attention of Queen Farah Diba (b. 1938), who incorporated them into national collections. In 1970, this painting and several other coffeehouse paintings travelled to Paris for an exhibition titled “Les Peintres Populaires de la Legende Persane” (Popular Painters of the Persian Legend) held at the Maison de l’Iran, a student residence on the campus of Cité Internationale Universitaire designed in the early 1960s (Zeinstra 2014, p. 133). The catalog presented Iranian coffeehouse painting as intended for those who could be moved emotionally “beyond the appearance of a formal rigidity [and rather by] an intense human deepness […] appealing to a candid eye and not to the specialist” (Groupe 7/Animation 1970, p. 1) (fig. 5). Coffeehouse painters were characterized as naïve autodidacts, “sons of the people,” who “created for the people, with the people” (Groupe 7/Animation 1970, p. 2). The exhibition coincided with the 1970 Shiraz Arts Festival patronized by Queen Farah Diba, and the Maison de l’Iran facilitated the travel of eighty French students to Shiraz to attend the festival (Temkine 1970, p. 129).

Today, coffeehouse paintings gain a renewed significance during the month of Moharram. Displayed in museums and public spaces, they engage an arguably larger audience than in their own period of creation, especially since traditional coffeehouses typically catered to a male clientele. Many traditional restaurants and coffeehouses in Tehran have chosen to decorate their walls with copies of coffeehouse paintings, showing that they continue to play an important role in Iranian popular visual culture (figs. 6–7).

An intriguing series of nested allusions to the coffeehouse experience can be found in the coffeehouse of a sofreh-khaneh (سفرهخانه, traditional restaurant) in Tehran (map) (fig. 8). A large tiled panel near a small kitchen area depicts a naqqali (storytelling) gathering in a coffeehouse. In the background (see the middle arch), a coffeehouse painting of the battle of Rostam and Asbolus, a legendary scene from Ferdowsi’s (d. 1020) Shahnameh (Book of Kings), can be seen. In an interview recorded in this space, a morshed (teacher) who was active as a storyteller in the post-revolutionary years, describes how he would lay out his pardeh and draw in his audience (audio 1). At the end of our discussion, he points to the tiled panel to help set the scene, confirming the central link between Iranian storytelling and its visual mediums.

Audio 1. Interview with a morshed in a sofreh-khaneh in Tehran. Recording by Chaeri Lee, 2016.

Transcription of the interview

Q: What was the people’s reaction? Of the audience, when you told these stories?

Mashdi: ما یک پرده میزدیم، پردهی بزرگ. عکس حرمله و جوانی علی اکبر و قاسم و امام حسین، اینها را یکی یکی می خواندیم تا میرسیدیم به رستم و سهراب. We put up a pardeh (curtain), a big pardeh. Pictures of Hurmala [ibn Kahil], and the young ʿAli Akbar, Qasem, and Emam Hosayn. We would recite them one by one until we got to Rostam and Sohrab.

[The first references are to Emam Hosayn and members of his camp who were martyred at Karbala in September 680. Rostam and Sohrab are heroes from the Shahnameh. In a tragic turn of events, Rostam meets his son Sohrab on the battlefield, neither recognizing the other. Rostam eventually fatally wounds Sohrab and only realizes his son’s identity in his last moments.]

Q: اول پس از امام حسین می گفتید و بعد می رفتید به رستم و سهراب؟ So, first you would speak of Emam Hosayn and then you would go to Rostam and Sohrab?

Mashdi: آره، پرده اول [امام حسین] بعد رستم و سهراب. فرهاد. شیرین و فرهاد، فهمیدی؟ اینها را بعد یکی یکی زیرش توضیح میدادیم به اینها مثلا چه کار میکردند، چه کار میکردند. [...] Yes, we would begin with the first pardeh. Rostam and Sohrab. Farhad. Shirin and Farhad, you understand? We would explain each of these one by one, like what they did and so on. [gap in trascription]

[Shirin and Farhad are star-crossed lovers whose story is narrated in the Shahnameh and also the second poem of the Khamseh (Quintet) of Nezami Ganjavi (d. 1209). Farhad, a highly-skilled sculptor, falls in love with the beautiful Armenian princess Shirin, who is betrothed to Khosrow II, the last great Sasanian ruler.]

Q: بعد شما چه میکردید؟ مردم واکنششون چه بود؟ قشنگ گوش میکردند؟ So what would you do then? How would the people react? Would they listen carefully?

Mashdi: قیامت میشد! ببین! میگویم اندازه ده هزار نفر بیشتر جمع میشد. دختر و پسر. میگویم هر قدر پول میریختند... It was like Judgement Day! Look! I say, more than the extent of ten thousand people were gathering. Boys and girls. I say, they would throw so much money…

Q: این مدت که پرده خوانی می کردید، فقط تو قهوهخانهها بود یا میرفتید تو میدانها می زدید؟ During this time that you were doing pardeh-khani, was it only in coffeehouses, or would you perform it in public squares too?

Mashdi: آره، مثل اون. آنها را می ببینی؟ نقال دیگه. اون نقال است. Yes, [just] like them [pointing to the tiled panel; fig. 8]. Do you see them? A narrator, right? He’s a storyteller.

Sources:

- Al-e Dawud, Ali. “Coffeehouse.” Encyclopædia Iranica, December 15, 1992 (last modified October 26, 2011), https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/coffeehouse-qahva-kana

- Aslani, Leila. “Chay-khāneh-hā avalīn gālerī-hā-ye Tehrān būdand!” (Teahouses were the first galleries in Tehran!). IRNA News Agency, 31 Mordad 1401/22 August 2022, https://life.irna.ir/news/84861499/چایخانه-ها-اولین-گالری-های-تهران-بودند

- Chelkowski, Peter. “Narrative Painting and Recitation in Qajar Iran.” Muqarnas 6 (1989): 98–111. [Archnet]

- Dehghanpour, Hamid. “Naqqali, Iranian Dramatic Story-telling,” Iranian Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organization, 2010. [watch the film on UNESCO]

- Diba, Layla. “The Formation of Modern Iranian Art: From Kamal-Al-Molk to Zenderoudi.” In Iran Modern, edited by Fereshteh Daftari and Layla Diba, 45–65. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013.

- Groupe 7/Animation, Les peintres populaires de la légende persane. Paris: Maison de l’Iran, 1970. [WorldCat]

- Lashkari, Amir and Mojde Kalantari. “Pardeh Khani: A Dramatic Form of Storytelling in Iran.” Asian Theatre Journal 32, 1 (2015): 245–58. [JSTOR]

- Seyf, Hadi. Naqqāshī-ye qahveh-khāneh (Coffee-House Paintings). Tehran: Reza Abbasi Museum, 1990.

- Temkine, Raymonde. “Festival du Theatre Rituel: Chiraz Persepolis (27 Août–6 Septembre 1970).” La Pensée: revue du rationalisme moderne 156 (December 1970): 129–33.

- Zeinstra, Jurjen. “Maison de l’Iran Paris: Claude Parent, André Bloc, Moshen Foroughi & Heydar Ghiaï-Chamlou.” DASH | Delft Architectural Studies on Housing 6, 10 (2014): 132–39. [TU Delft OPEN]

Citation: Chaeri Lee , “Naqqashi-ye qahveh-khaneh (coffeehouse painting).” Catalog entry in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.