19Two cross tiles with Persian verses attributed to the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin

Iran, probably Kashan, one probably dated 660/1262 Fritware (stonepaste), luster-painted on opaque white glaze 12 1/5 in. (31 cm) The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia, IR-1052 (left) and IR-75 (right) Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum/photo by Dmitry Sadofeev

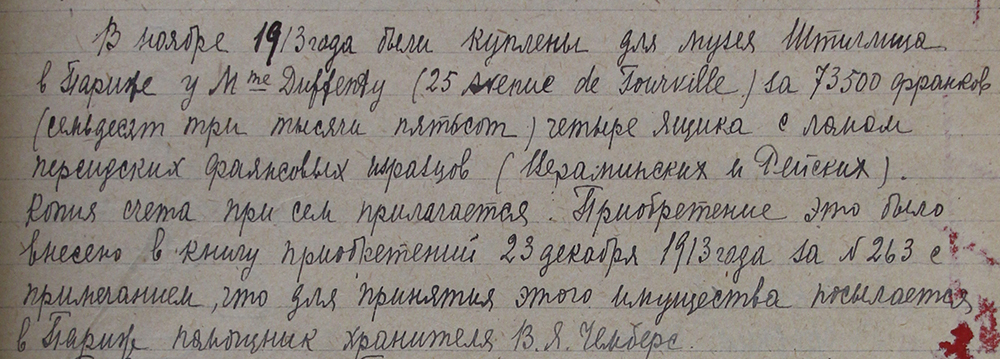

The State Hermitage Museum’s collection contains more than 950 luster tiles, complete and in fragments, presumed to have come from the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin. Most are stars and crosses that would have decorated the tomb’s dado. The majority of these tiles were acquired in 1913 for the museum of the Stieglitz Central School of Technical Drawing from Clotilde Duffeuty, a French dealer based at 25, Avenue de Tourville in Paris. In the early 1920s, the Stieglitz Museum was attached to the State Hermitage Museum, and in 1924–27, all objects connected to Asian and African art and history were transferred to the Oriental Department of the Hermitage. In 1925, Ernest K. Querfeld (d. 1949), then curator and director of the Stieglitz Museum, wrote a report to Joseph A. Orbeli (d. 1961), then curator of the Near Eastern collections at the Hermitage, providing information about the 1913 acquisition (fig. 1):

Transcription: В ноябре 1913 года были куплены для музея Штиглица в Париже у Mme Duffenty [sic] (25 Avenue de Tourville) за 73500 франков (семьдесят три тысячи пятьсот) четыре ящика с ломом персидских фаянсовых изразцов (Вераминских и Рейских). Копия счета при сём прилагается. Приобретение это было внесено в книгу приобретений 23 декабря 1913 года за №263 с примечанием, что для принятия этого имущества посылается в Париж помощник хранителя В.Я. Чемберс.

Translation: Four boxes with broken pieces of Persian faience tiles (Varamin-type and Rey-type) were acquired for the Stieglitz Museum for 73500 francs (seventy-three thousand five hundred) in November 1913 in Paris from Mme Duffenty [sic] (25 Avenue de Tourville). Copy of the bill is attached hereby. This acquisition was recorded into the book of acquisitions on December 23, 1913 with #263 with a note that assistant keeper V. Y. Chambers was sent to Paris to accept this property.

The star and cross tiles attributed to the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya are bordered by inscriptions generally containing verses from the Qur’an. Some of these tiles are displayed in the museum’s Iran gallery on the third floor of the Winter Palace in the main museum complex (map), next to the tombstone cover belonging to ‘Emam Yahya’ (IR-1594, fig. 2) (see Blair’s essay here).

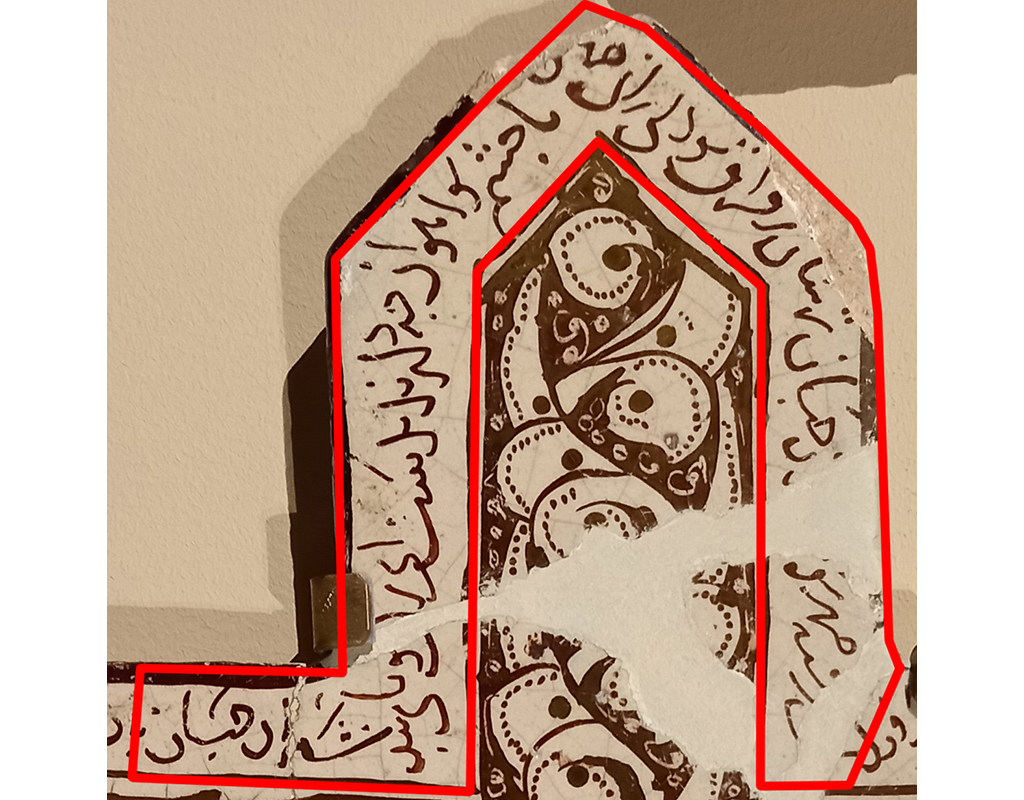

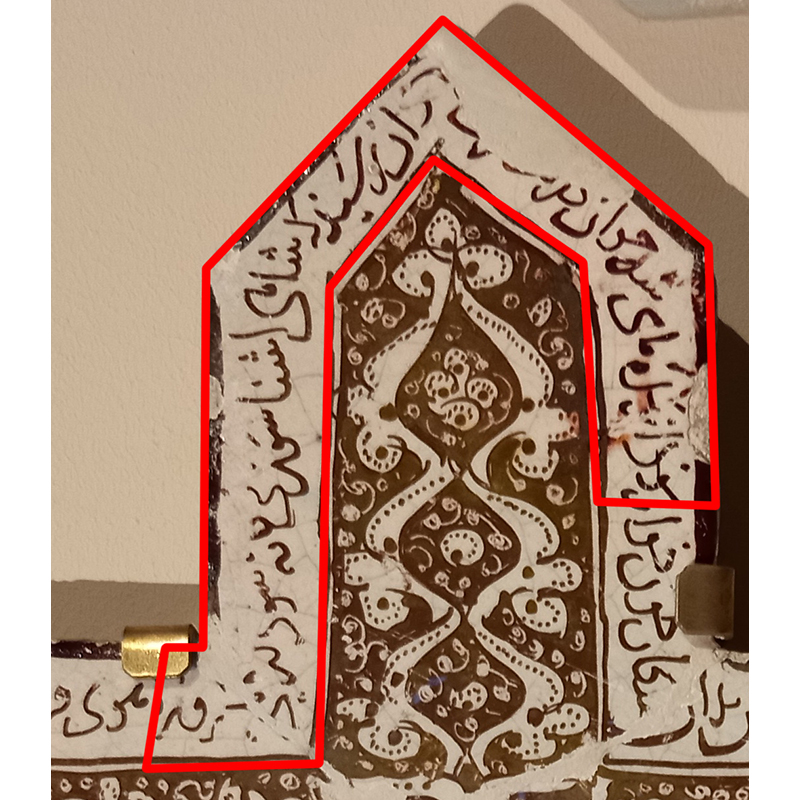

In this catalog entry, I focus on tiles attributable to the tomb that are lesser known: two cross tiles with Persian verses. Persian verses on tiles of the ‘Varamin-type’ (see fig. 1) are not very common. Of the more than 950 tiles in the Hermitage collection, less than ten have Persian verses. The two crosses considered here are displayed in the gallery next to the main Iran one (fig. 3, vid. 1).

Video 1. Walking from the Iran gallery to room 393. Video by Dmitry Sadofeev, 2024.

The eminent scholar Leon Tigranovich Gyuzalian (d. 1994) studied Persian poems on various objects in Soviet museums for many years (Adamova and Rogers 2003). He came to the conclusion that inscriptions on tiles were often closer to the original poems than those recorded in manuscripts (Gyuzalian 1951a, 1951b). Persian verses began to appear on Iranian ceramic vessels and tiles in the late twelfth century. The earliest known object featuring Persian verses is a luster-painted bottle dated 575/1179 (British Museum, 1920,0326.1). Persian verses were commonly found on ceramics and tiles through the mid-fourteenth century, at which time production declined. By the fifteenth century, Persian verses became more prevalent on copper and bronze objects, including this famous jug (Hermitage, IR-2044) with verses by Qasem-e Anvar Tabrizi (1356–1433). Persian verses were not as common on fifteenth through eighteenth-century ceramics, but some important examples are known, including a large Timurid dish dated 878/1473–74 and made in Mashhad (Hermitage, VG-2650) and a base of a water pipe (nargileh or hookah, Hermitage, VG-366) (Ivanov 1980; Kanda 2024).

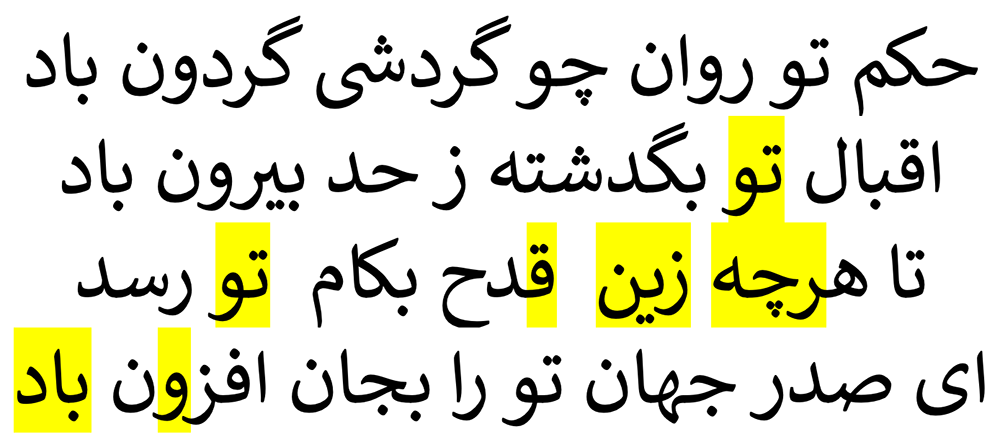

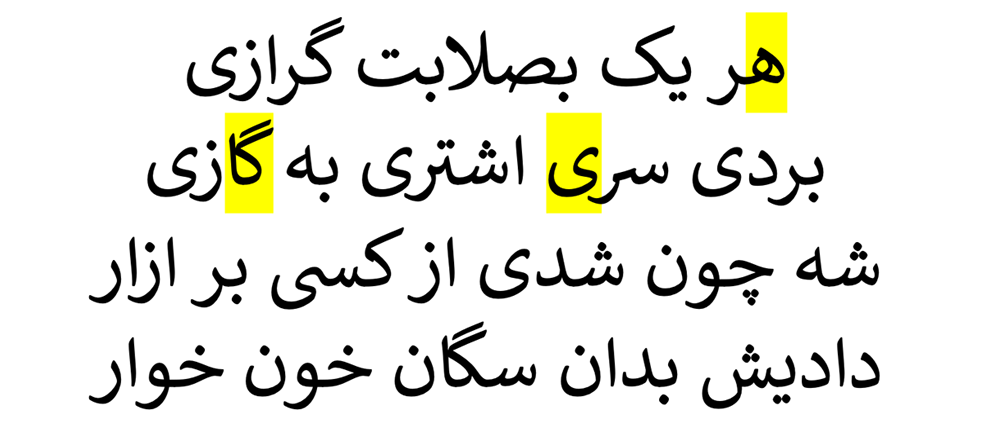

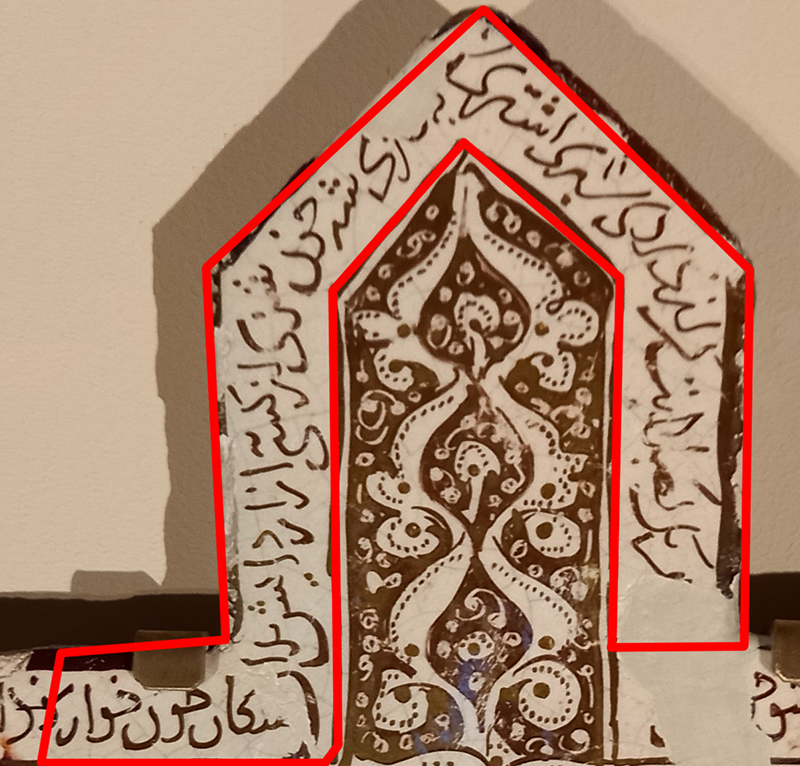

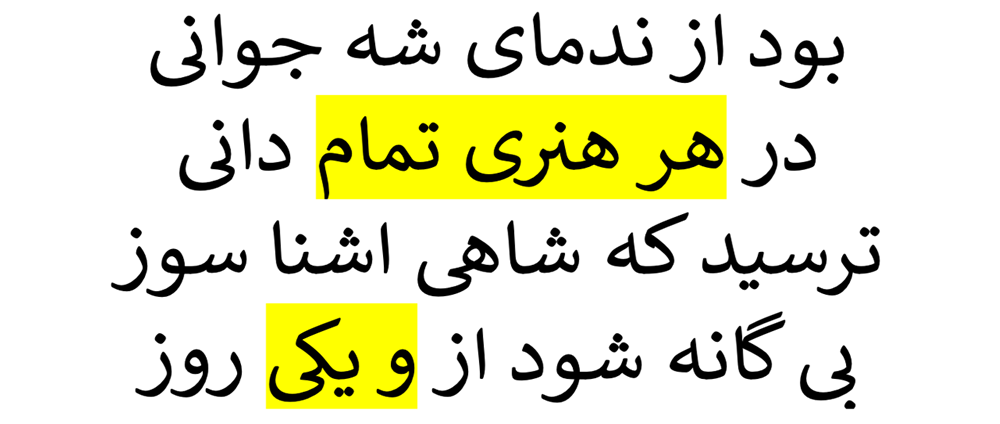

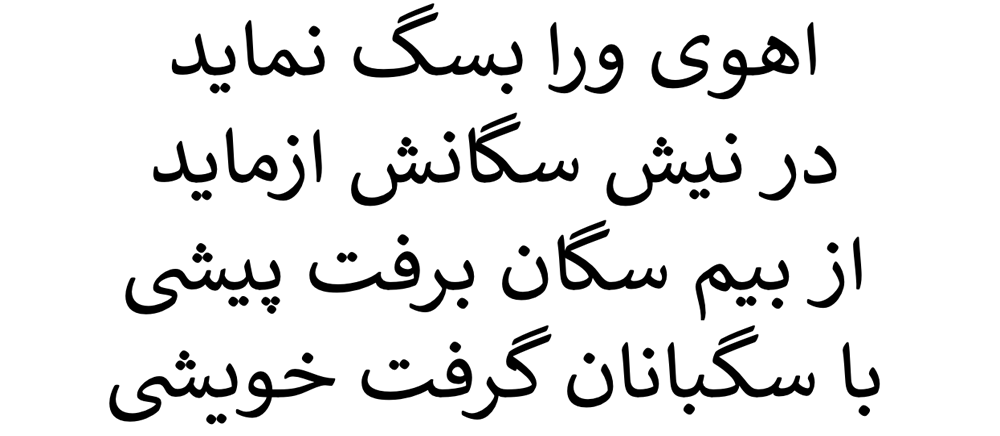

Tile IR-75

This inscription is four independent poetic texts with similar romantic imagery and generic good wishes (Gyuzalian, 1961, p. 39–41). The first text is a robaʿi (رباعی, quatrain) by Jalaluddin (Jalal al-Din) Mohammad Balkhi (1207–73), a Persian-language poet from Balkh in modern Afghanistan. Before the Mongol invasions of Iran, his family left their native city and settled in Anatolia (Rum in the historical tradition). His later life and work are associated with Konya, and he became famous as Mevlana Jalaluddin Rumi.

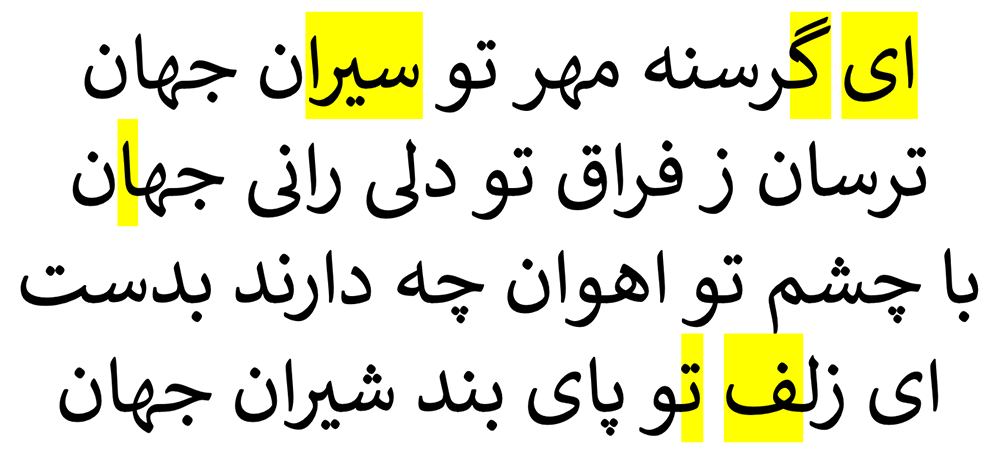

The quatrain occupies about one fourth of the tile:

(yellow highlights indicate losses)

O, those who are fed up with the world are hungry for your love,

And those who rule the world are afraid of separation from you!

What can gazelles oppose to your eyes?

O, whose locks of hair like fetters have bound all the lions of the world!

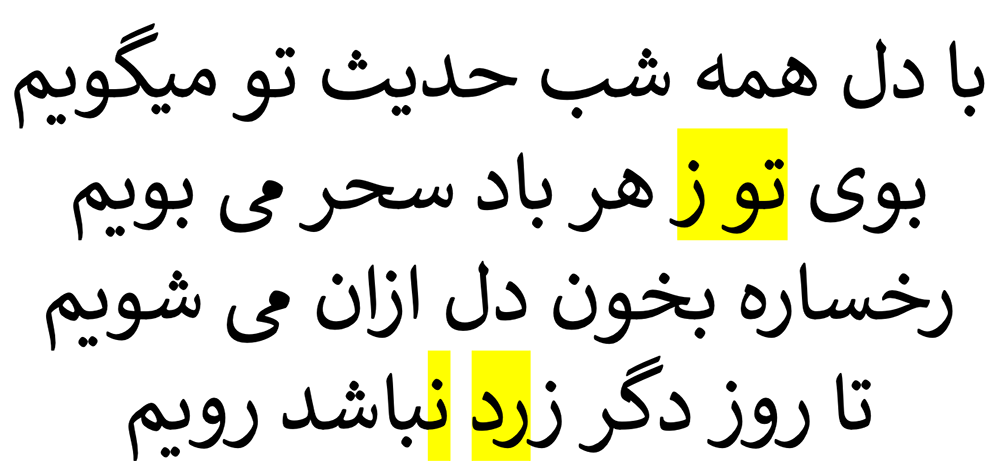

The second text is less common on ceramics but thematically related to the first rubaʿi:

All night long I talk about you with my heart

And inhale your scent from every breath of the morning breeze.

That is why I wash my cheeks with the blood of my heart,

So that the next day my face will not be yellow.

The third text wishes the owner well and is associated with the first text through rhyme:

May your orders be clear like spinning sky.

May your good fortune surpass all limits.

So that everything in this bowl brings you enjoyment

O, minister of the world—may it prolong your life.

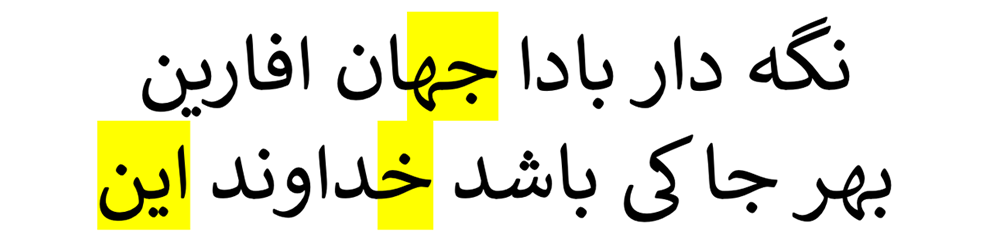

The fourth text is a couplet found on many different ceramic objects, including this star tile (Hermitage, IR-1195), and wishes the owner well:

May the Creator protect the owner wherever he may be.

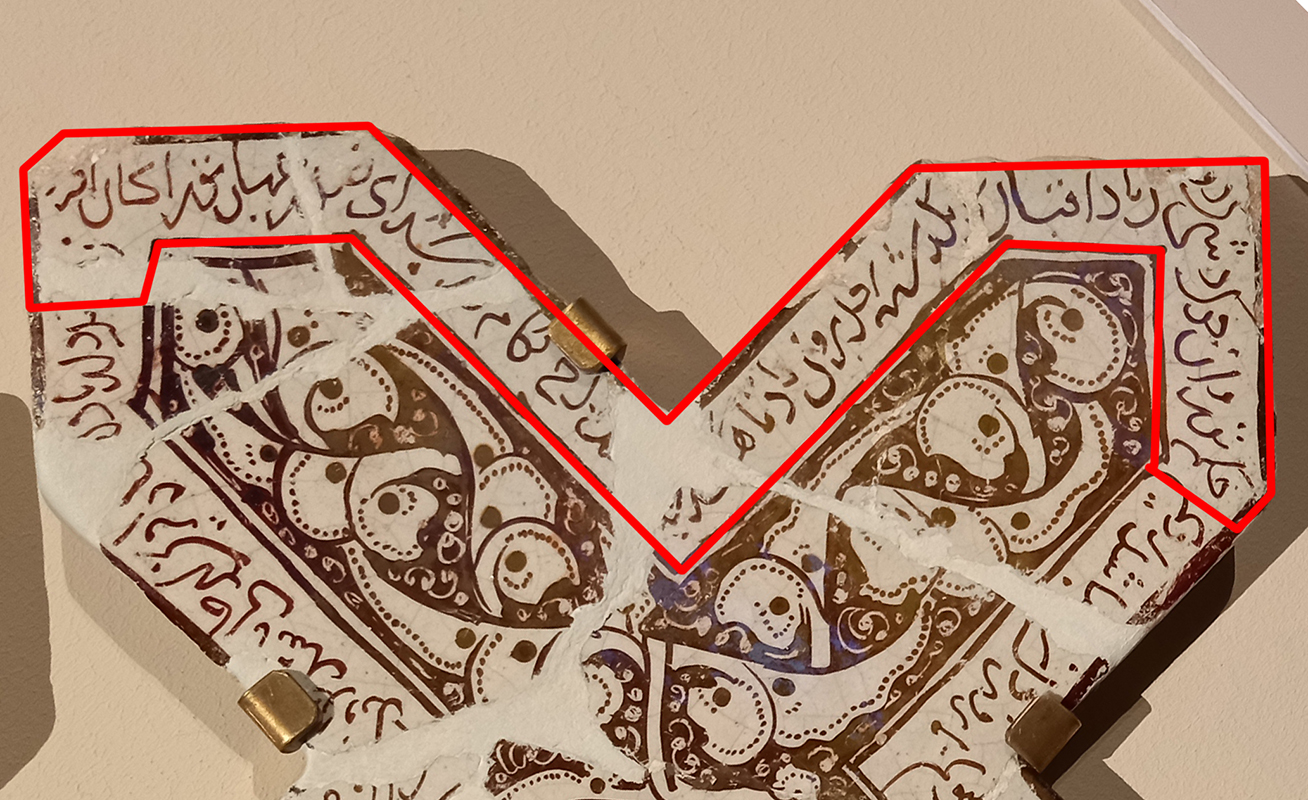

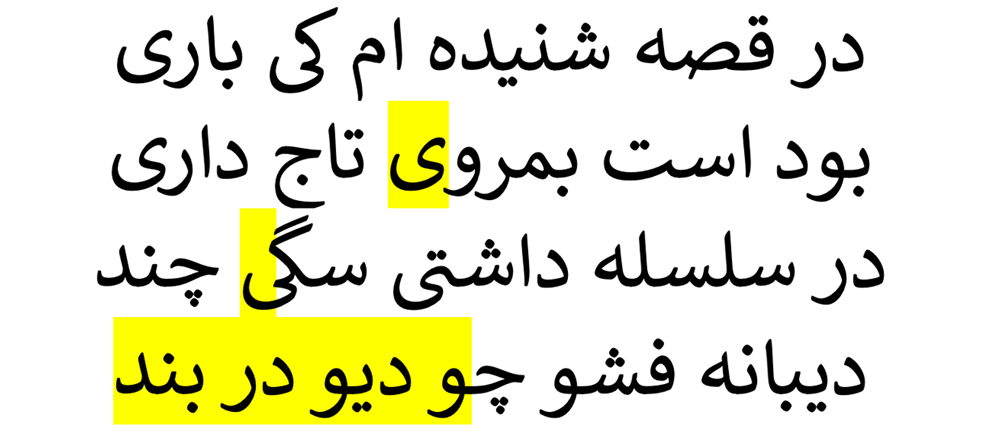

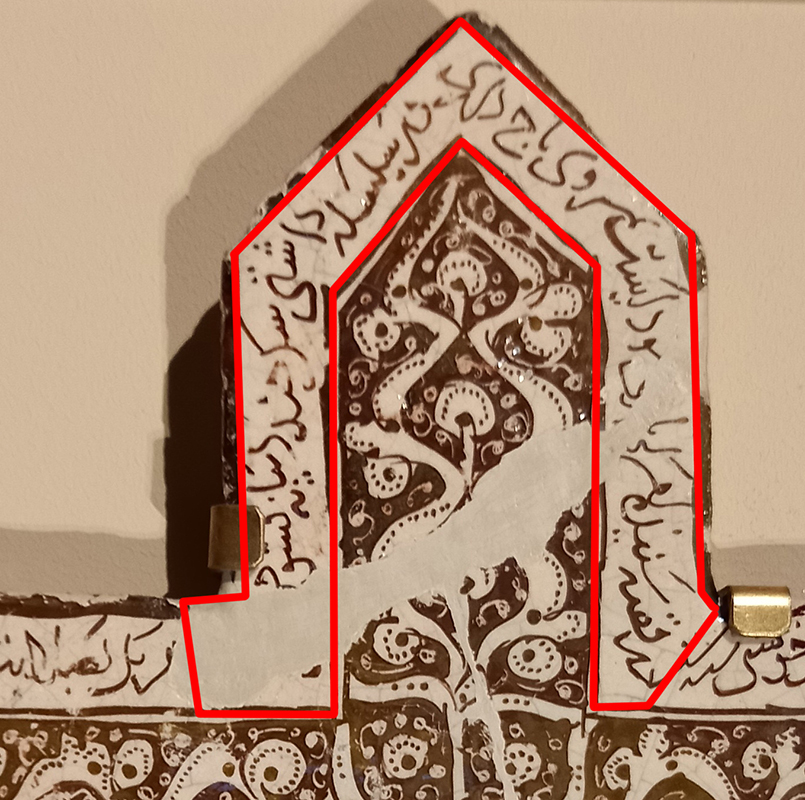

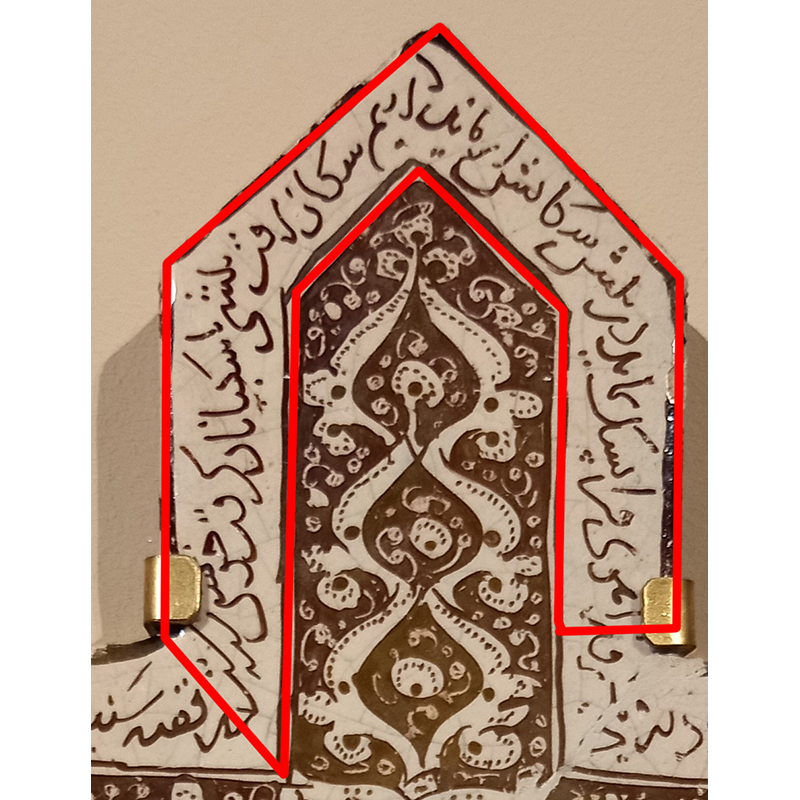

Tile IR-1052

This inscription is an excerpt from one of the parenthetical stories (told by one character to another or to compare and describe different characters, circumstances, and ideas) in Nezami Ganjavi’s “Layla and Majnun” (لیلی و مجنون) (Gyuzalian 1953, p. 20). Nezami Ganjavi (1141–1209) lived in the city of Ganja (modern Azerbaijan) and wrote in Persian, and “Layla and Majnun” is the third of five narrative poems in his Khamseh (خمسه, Khamsa, Quintet). This tile is the earliest known object on which verses of Nezami’s “Layla and Majnun” have been preserved. The earliest known manuscript of the Khamseh is dated 763/1361 and kept in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris (Supplément Persan 1817). A famous manuscript in the State Hermitage Museum (VP-1000) is dated 835/1431 and was created for Sultan Shahrukh (r. 1405–47), son of Timur (Tamerlane, r. 1370–1405).

This excerpt comes from an instructive story (cautionary tale or parable) in which Nezami compares Majnun’s kindness to the animals in the desert where he lived and the kindness of a young man from the town of Merv to the bloodthirsty dogs in the kennel of Merv’s ruler. It begins:

I heard a story that there was a ruler in [the town of] Merv.

He had a number of chained watchdogs, similar to those possessed by divs, and similar to divs in chains.

It continues:

Each of them possessed the ferocity of a boar and could bite off a camel’s head at once.

When the Shah happened to be dissatisfied with someone, he would hand him over to those bloodthirsty dogs.

It continues:

Among the Shah’s courtiers there was a young man, well versed in all arts.

He was afraid that one day the Shah, who had destroyed his loved ones, would become unfamiliar to him.

It continues:

So the Shah would show his faults to the dogs and the dogs would torture and savage him.

Because of his fear of dogs, he succeeded and made friends with the kennel keepers.

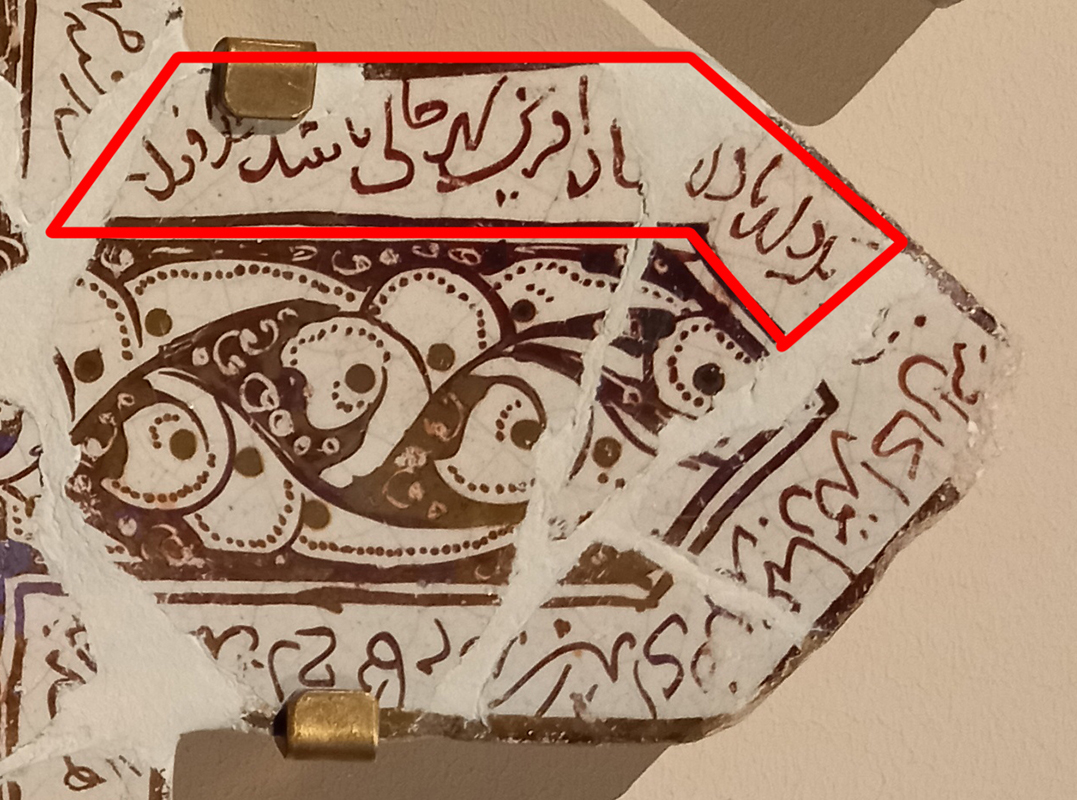

At the end of the band, there was not enough space to write the date properly, so the calligrapher wrote it briefly. This date can be interpretated as ‘year six hundred and sixty’ of the Islamic calendar, which coincides with dated tiles (660–63/1262–65) attributed to the Emamzadeh Yahya.

Year six (sixty?)

All translations are by the author.

Sources:

- Adamova A.T., Rogers J.M. “Leon Tigranovich Gyuzalian, on the Centenary of His Birth (15 March 1900).” Iran 41 (2003): 309–13. [JSTOR]

- Gyuzalian, L.T. “Verses from the Shahname on thirteenth and fourteenth-century ceramics (I).” Epigrafika Vostoka 4 (1951): 39–55. (in Russian)

- Gyuzalian, L.T. “Verses from the Shahname on thirteenth and fourteenth-century ceramics (II).” Epigrafika Vostoka 5 (1951): 33–50. (in Russian)

- Gyuzalian, L.T. “Two verse inscriptions from Nizami on thirteenth and fourteenth-century tiles.” Epigrafika Vostoka 7 (1953): 17–25. (in Russian)

- Gyuzalian, L.T. “Some verse inscriptions on tiles from Varamin in the Hermitage collection.” Epigrafika Vostoka 14 (1961): 36–43. (in Russian)

- Ivanov A.A. “A Fifteenth-century faience dish from Mashhad.” Soobscheniya Gosudarstvennogo Ermitaja 45 (1980): 64–65. (in Russian)

- Kanda, Yui. “Iranian Blue-and-White Ceramic Vessels and Tombstones Inscribed with Persian Verses, c. 1450–1725.” In The Routledge Companion to Global Renaissance Art, edited by Stephen J. Campbell and Stephanie Porras, 363–77. New York: Routledge, 2024. [Taylor & Francis]

- Yuzbashian, Karen. “Orbeli, Iosef Abgarovich.” Encylopaedia Iranica, December 6, 2016, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/orbeli-iosif.

Citation: Dmitry Sadofeev, “Two cross tiles with Persian verses attributed to the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin.” Catalog entry in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.