The Luster Cenotaph from the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin

Sheila Blair

The term cenotaph (from the Greek ‘empty tomb’) denotes the large rectangular box used in the Islamic lands to mark the graves of Muslims, Jews, and others who, according to tradition, must be buried (fig. 1).1 A cenotaph thus differs from a sarcophagus (from the Greek ‘flesh eating’), which contains a corpse. Cenotaphs set outdoors in cemeteries in Iran where they were exposed to inclement weather were typically made of stone, but those within tombs were often constructed of fancier materials such as carved wood or glazed ceramic.2 Some of the finest examples produced in Iran during the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries were covered with luster tiles, costly because of the metallic oxides for glazing, extra fuel for double firing, and special expertise for the complicated manufacturing process, a skill known only to a handful of potting families working mainly at Kashan in central Iran.3

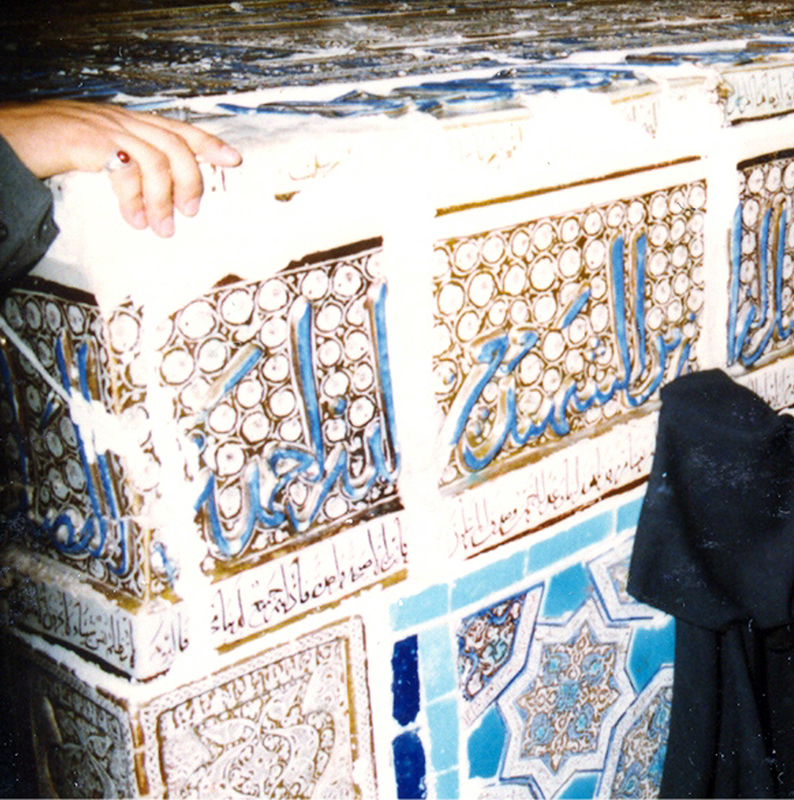

Usually placed in the center of a tomb to allow for veneration and circumambulation, the indoor cenotaph was often surrounded by a pierced screen or grill (zarih), a tradition that can be traced back to the grave of the Prophet Mohammad, who was buried in his house in Medina after his death in 11/632. The screen protected the cenotaph but also provided a handhold for pilgrims to connect to the deceased’s spiritual powers or baraka emanating from the ground below. With repeated contact, the screens wore out. Patrons and rulers took advantage of the opportunity to endow more elaborate ones, thereby underscoring their own authority and legitimacy by association with revered religious figures. The Safavids, for example, often replaced the screen around the cenotaph for Emam Reza in his tomb chamber within the shrine at Mashhad (Shrine of Emam Reza, Haram-e Emam Reza, Astan-e Quds-e Razavi; map) to mark their role as propagators of Twelver Shiʿism (fig. 2).4

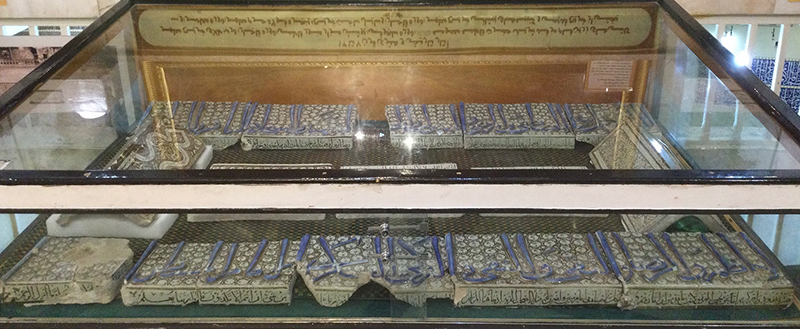

The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin now houses a boxlike cenotaph inside a large screened enclosure (zarih) with a foundation text recording that the work was done during the vilayat (literally ‘guardianship’) of Grand Ayatollah Khamenei in 1389 Sh/2010, an action clearly modeled on precedent (fig. 3).5 While the current screen and cenotaph are modern additions, by combining three types of evidence—descriptions by nineteenth-century travelers, extant tiles with inscriptions, and comparison with contemporary examples—we can partially reconstruct a cenotaph covered with luster tiles that dates from medieval times.

The best-known traveler to the site is the Frenchwoman Jean Dieulafoy (d. 1916), who visited the shrine on June 18, 1881 during a week-long visit to Varamin.6 Noting that it was one of the most interesting monuments in the country but also the only one that was closed and guarded, she described in some detail the extensive luster tiling on the tomb’s interior, all of the finest quality. She mentioned first the luster tiles on the mihrab, dado (lambris), and tomb (tombeau) and then two paragraphs later the ones on the dado, sarcophagus (sarcophage), and mihrab. Presumably both tombeau and sarcophage refer to the cenotaph, as it is the third area of a tomb, along with the mihrab and dado, that was typically covered with luster tiles (see Leone). The tomb of Shaykh ʿAbdosamad within the shrine at Natanz (map) provides a good comparison (see Leone 2021 and Sites with Luster).

Dieulafoy was not the first to discuss the cenotaph in the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin. Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh (d. 1896), a Qajar historian who had visited the tomb a few years earlier in 1876, mentioned a wooden marqad set in the middle of the tomb (see Overton and Nakhaei).7 The term he used, marqad (literally ‘place of sleep’), is the one used for cenotaph in medieval texts, inscriptions in various media, and modern art historical literature.8 As he specified this marqad was of wood and quite large (giving dimensions equivalent to 1.82 x 3.38 m/5.97 x 11.09 ft), scholars have suggested that he might have been referring to a surrounding screen rather than the cenotaph itself.9

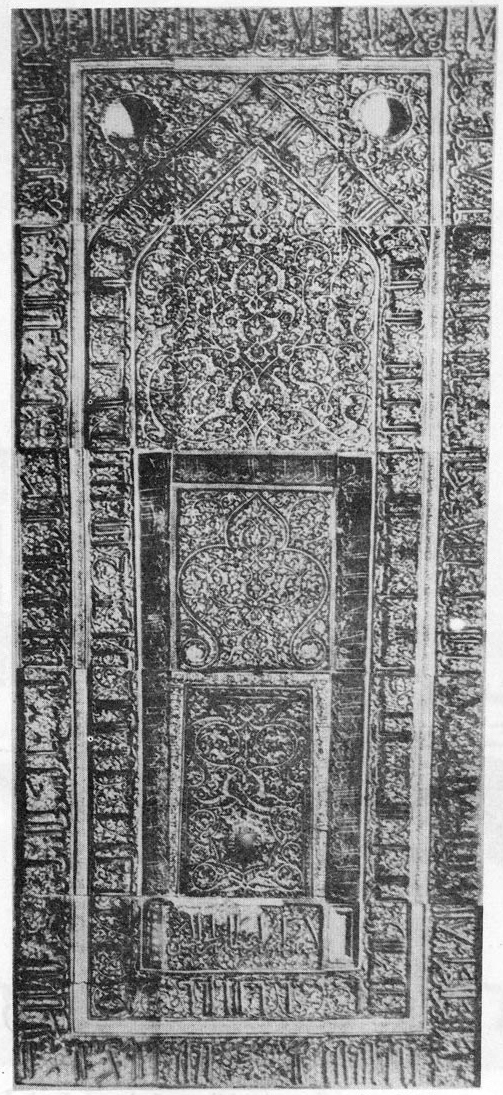

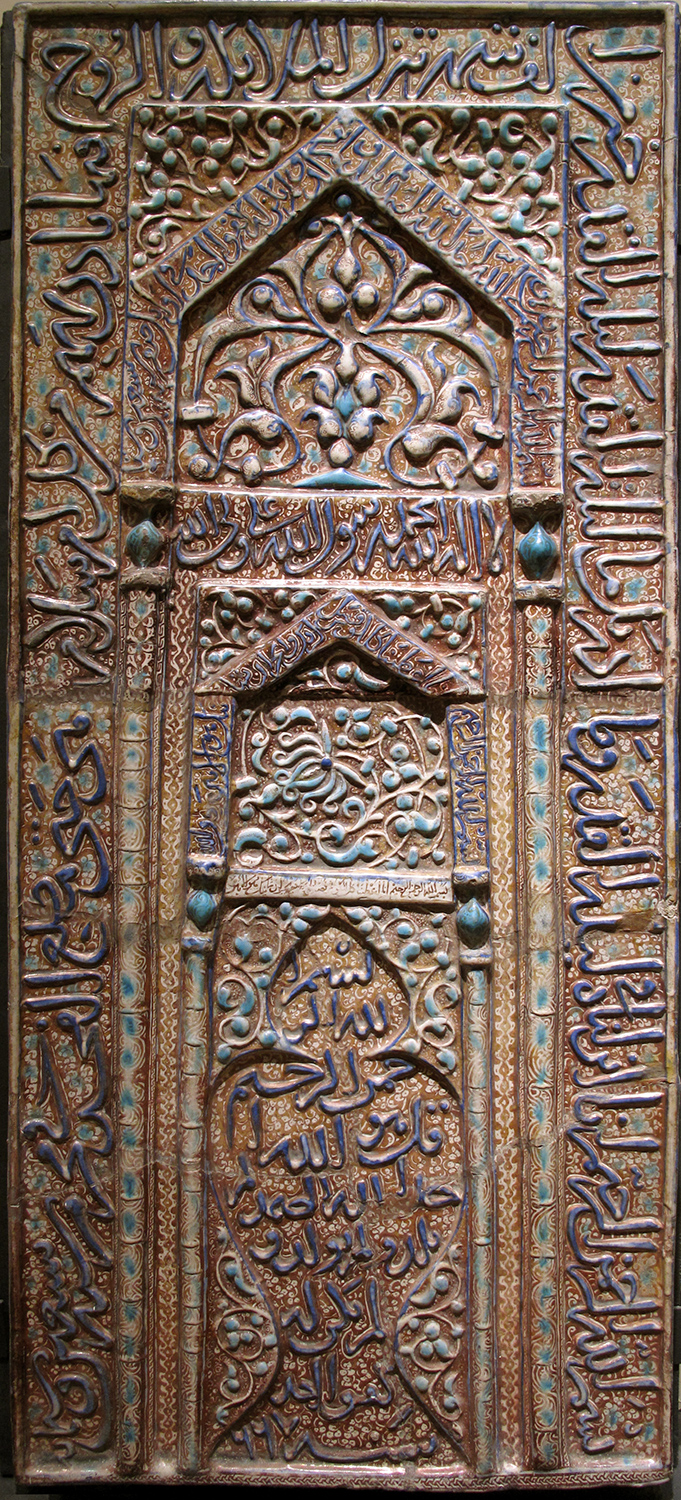

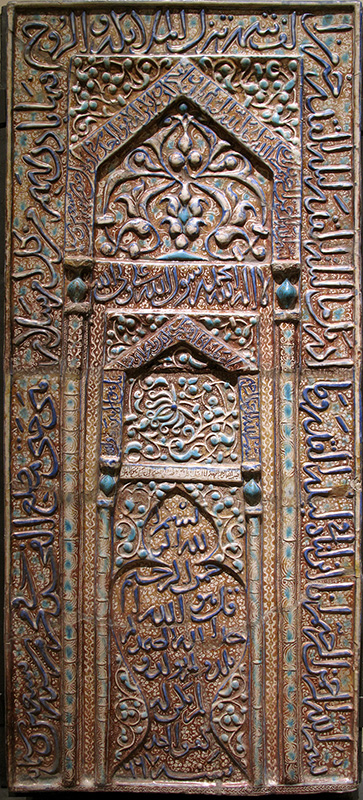

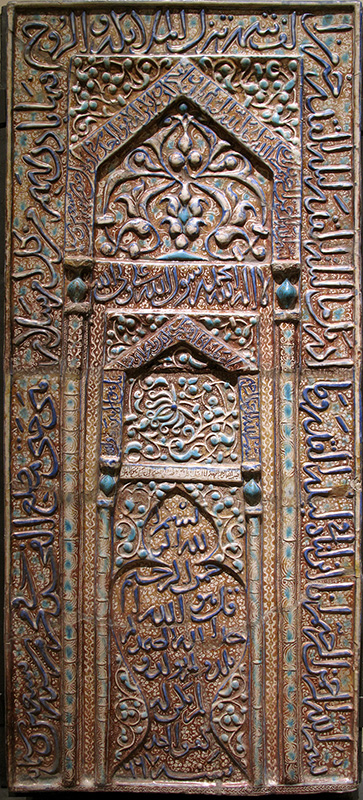

Several surviving luster tiles may well have belonged to the cenotaph mentioned by Dieulafoy in the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin. The best possibility is the set (221 x 87 cm) of four large tiles in the State Hermitage Museum (IR-1594) in St. Petersburg that displays two nested niches framed on three sides with an inscription band (fig. 4).10 The relief inscription on the lintel (horizontal bar) of the outer arch reports that “This is the grave (qabr) of the wise Emam Yahya, may God bless him.” There were several emamzadehs in the region for people named Yahya (see the list here), but the one at Varamin is the only one known to have had luster decoration, and virtually all scholars have assumed that the set comes from this site.

The other relief inscriptions on the set of four luster tiles in the Hermitage give us more information about when they were made and by whom. The outer frame band contains the well-known Throne Verse (Qurʾan 2:255), followed by the date and a potter’s signature: “written (kutiba) on 10 Moharram 705/2 August 1305; work (ʿamal) of Yusof b. ʿAli b. Mohammad.” The fifteen-lined inscription inside the inner arch contains another Qurʾanic passage appropriate for a funerary context (41:30-32, about angels and the promise of Paradise), followed by the name of a second potter: “decoration (ṣanaʿat) of ʿAli b. Ahmad b. ʿAli al-Hosayni katibi (the scribe).”

The date of 705/1305 inscribed on the Hermitage set shows that the luster cenotaph was part of the renovations of the Emamzadeh Yahya ordered by the local ruler of the area, Malek Fakhroddin (Fakhr al-Din, d. 707/1307-8) (see my 2016 article), an action intended to bolster his political legitimacy and religious affiliation, as patrons to other emamzadehs and shrines had done. The relief inscriptions on the tiles in the Hermitage also tell us that the set was made by two of the most famous potters of their day. Yusof was a fourth-generation member of the best-known family of potters from Kashan, the Abu Tahers. He left several other signed and dated works, including the band framing the mihrab in the tomb of ʿAbdosamad at Natanz completed a few years later in Shaʿban 709/January 1310.11 Yusof’s father ʿAli b. Mohammad had made luster tiles for the Emamzadeh Yahya four decades earlier: he signed the large mihrab dated Shaʿban 663/May 1265 now in the Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art in Honolulu (DDFIA, 48.327; see my 2014 essay). The second potter named on the Hermitage tiles, ʿAli b. Ahmad b. ʿAli, also left several other signed works, including a pair of small plaques with arched designs, the so-called Salting mihrab and its mate (V&A, C1977-1910 and 1527-1876), and a large set of three tiles dated Rabiʿ II 713/July 1313 that likely covered the top of the cenotaph in the tomb for Khadijeh Sultan at Qom (DDFIA, 48.348).12

We do not know precisely the different roles played by the two potters Yusof b. ʿAli b. Mohammad and ʿAli b. Ahmad b. ʿAli al-Hosayni in making the set of luster tiles in the Hermitage. Luster potters signed their works in various ways, using versions of at least three verbs on some luster and enameled wares (minaʾi). The clearest examples come from the work of Abu Zayd (fl. c. 1180-1220), the potter who left more signed works than anyone else and the only potter known to have worked in both luster and enamel.13 Abu Zayd often signed his wares saying that he wrote (kataba) it [the inscription] in his own hand (bi-khatthi) after he had made (ʿamila) and decorated (ṣanaʿa) it [the object].14 The simplest way to explain this sentence in the complex context of making lusterwares is to imagine that the potter Abu Zayd first made (ʿamila) the object, either throwing a vessel on a potter’s wheel or shaping a tile in a mold. In the case of relief inscriptions on tiles, the potter then formed the letters separately and affixed (the technical word is luted) them to the surface. After allowing the object to air dry, the potter next decorated it (ṣanaʿa) with an opaque glaze before firing it in a hot kiln (under 1000°C). Once the object had cooled, the potter finally wrote (kataba) inscriptions in metallic oxide or scratched them through the metallic oxide before re-firing the object in a reducing kiln.15 The signatures on the set of tiles in the Hermitage contain variants of the same three verbs, ʿamila (to make), ṣanaʿa (to decorate), and kataba (to write), but the distinctions are less clear than in Abu Zayd’s signatures on a single object. Presumably the two potters collaborated in a workshop that made this set of luster tiles, but we cannot specify exactly what each potter did.

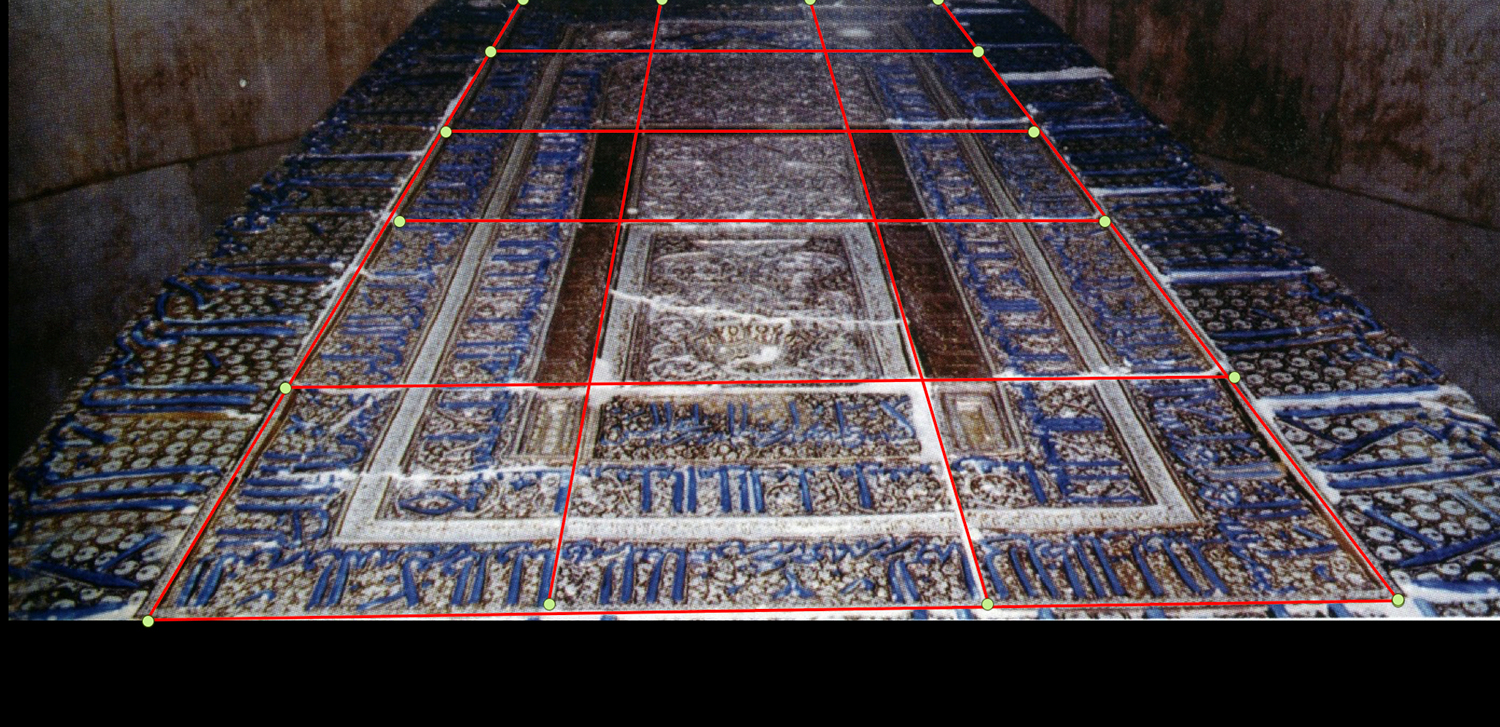

Comparison with three other luster cenotaphs that survive from the period (see Table 1) can help us understand where the set of four tiles in the Hermitage fit on the cenotaph for ‘Emam Yahya’. The most extraordinary and earliest known example of a luster-tiled cenotaph is the one for Fatemeh Maʿsumeh in her tomb within the shrine at Qom (map) (fig. 5).16 The large cenotaph has recently been revamped but originally measured approximately 3.5 x 1.7 x 1.2 m.17

Table 1. Datable Luster Cenotaphs with ‘Tombstones’ on the Top (discussed in this essay)

| Tombstone | Date | Recipient | City | Estimated dimensions of cenotaph (cm) | Location of tombstone | Tiles in tombstone | Dimensions of tombstone (cm) | Potters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Fig. 9

Fig. 9 |

2 Rajab 602/12 February 1206 | Fatemeh Maʿsumeh | Qom | 350 x 170 x 120 | In situ | 15 | 300 x 120 | Abu Zayd; Mohammad b. Abi Taher b. Abi’l-Hosayn; additions by ʿAli b. Mohammad b. Abi Taher |

Fig. 12

Fig. 12 |

667-70/1268-71 | Emam Habib b. Musa | Kashan | ? | National Museum of Iran, Tehran, 3289 | 2 or 3 | 137 x 57 | |

Fig. 4

Fig. 4 |

10 Moharram705/2 August1305 | ‘Emam Yahya’ [Emamzadeh Yahya] | Varamin | 271 x 137 | State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, IR-1594 | 4 | 221 x 87 | Yusof b. ʿAli b. Mohammad; ʿAli b. Ahmad b. ʿAli al-Hosayni |

Fig. 14

Fig. 14 |

Shawwal 709/March 1310 | Shaykh ʿAbdosamad | Natanz | 346 x 246 | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 09.87 | 3 | 123 x 60 | ʿAli b. Mohammad b. Fazlallah al-… |

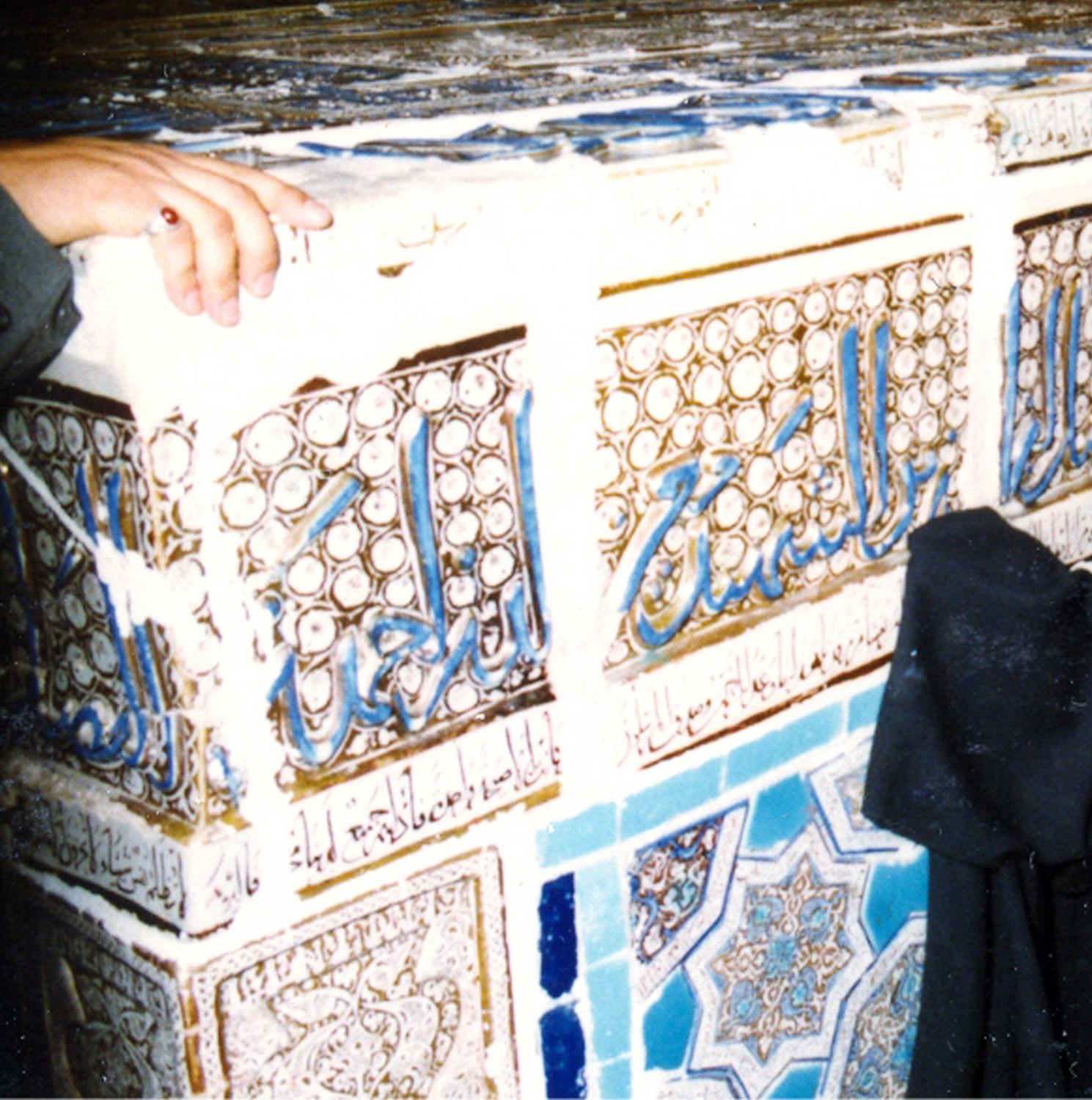

A large band of twenty-three L-shaped tiles once encircled the top of the cenotaph (fig. 6), but has been removed to the shrine’s site museum (fig. 7). The large upper surface of the tiles, measuring 24 centimeters high, contains a large relief inscription in blue with prayers to the Fourteen Innocent Ones (Mohammad, Fatemeh, and the Twelve Emams), while the much smaller overhanging lip (visible in fig. 5 and fig. 7) includes an inscription written in luster containing verses 16-38 from sura Ya Sin (chapter 36) of the Qurʾan.

On the original cenotaph, this outer band surrounded a central section, sometimes called a ‘tombstone’ (luh-e mazar), comprising fifteen luster tiles set in five superposed rows, with three tiles (60 x 40 cm) in each row (fig. 8). The tombstone, still in situ, displays three nested niches with different profiles (keel-shaped, lobed and pointed, and lobed and flat-topped) (fig. 9). A relief band across the bottom below the innermost niche says that Mohammad b. Abi Taher b. Abi’l-Hosayn wrote (kataba) and made (ʿamila) it.18

The sides of the original cenotaph for Fatemeh in her tomb at Qom were also covered in luster tiles. Large inscription bands once encircled the sides at the top and bottom, but they too have been taken to the shrine museum (fig. 10). The large relief text in blue around the top, beginning in the right (northwest) corner, contains the foundation inscription saying that Mozaffar b. Ahmad b. Esmaʿil, son of the deceased vizier Moʿin al-Din Ahmad b. Fazl b. Mahmud, ordered the arrangement of this “Chinese” inscription (tartīb hadha al-kitāba al-ṣīniyya).19 It ends with the information that Abu Zayd wrote (kataba) it on the second of Rajab of the year 602/12 February 1206 (fig. 10, right). The band around the bottom has a relief inscription with Qurʾan 2:285-86 about God and His Prophet. These large bands also have smaller border inscriptions written in luster. The band at the top has a luster inscription band along the bottom, whereas the band at the bottom has two smaller bands at both top and bottom. These inscriptions contain Qurʾanic verses and again end with the information that Abu Zayd wrote (kataba) it.

The four corners of the cenotaph were once filled with tall V-shaped panels (each face measuring about 21 centimeters wide), inscribed with more Qurʾanic verses and prayers written in luster. One panel is intact; the other three are composed of two pieces. Two of these tall V-shaped corner panels display lobed and pointed niches (fig. 11); the other two display a different design with lobed and flat-top niches (one is shown upside down on the right in figure 10, left). One with a flat-top niche has an inscription ending with the phrase that ʿAli b. Mohammad b. Abi Taher wrote (kataba) it; the other has an illegible date.20 These two corner panels with lobed and flat-top niches were likely replacements, since other work by ʿAli b. Mohammad b. Abi Taher, such as the mihrab removed from the Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin and now in Honolulu, dates from the 1240s to the 1260s.21

Sandwiched between the two encircling bands of inscriptions and still in situ on the sides of the cenotaph are five rows of small luster tiles alternating with monochrome blue-glazed tiles shaped like bow ties or the Italian pasta called farfalle (see fig. 5). The luster tiles in the center row are octagonal, while those in the bottom and top rows are half octagons. These two alternating rows of luster tiles contain eight-pointed stars.

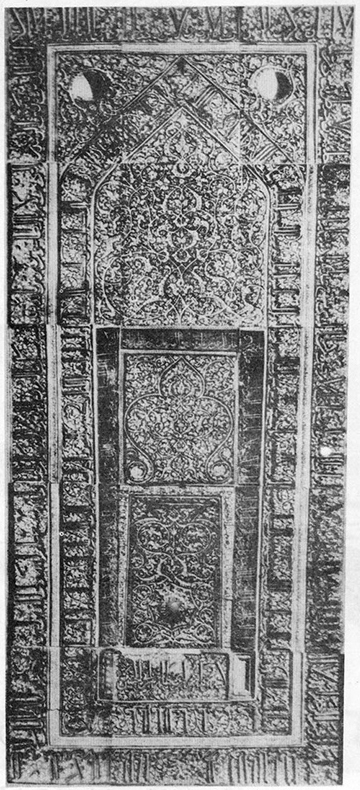

In addition to the cenotaph for Fatemeh, the largest and most elaborate luster example to survive from the period, two other examples provide comparative material. A large rectangular cenotaph is still in situ in the Emamzadeh Habib b. Musa (map) in Kashan inside a heavy metal and wooden screen.22 The luster tombstone once on the top and now removed to the National Museum of Iran in Tehran (no. 3289) comprises a large set of two or three tiles (133 x 57 cm) displaying nested niches and containing several dates spanning 667-70/1268-71 (fig. 12).23

The sides of the cenotaph are covered in panels of luster tiles (small hexagons and six-pointed stars) alternating with monochrome tiles of various shapes (fig. 13). The small luster hexagons are particularly interesting as they display not only birds and animals, but also depictions of people, including a seated male holding an open book.24 Recent photographs of the cenotaph in situ shared by Maryam Kolbadinejad show a luster frieze with Qurʾan 76:1-10 in jumbled order around the top of the reconstructed cenotaph.25

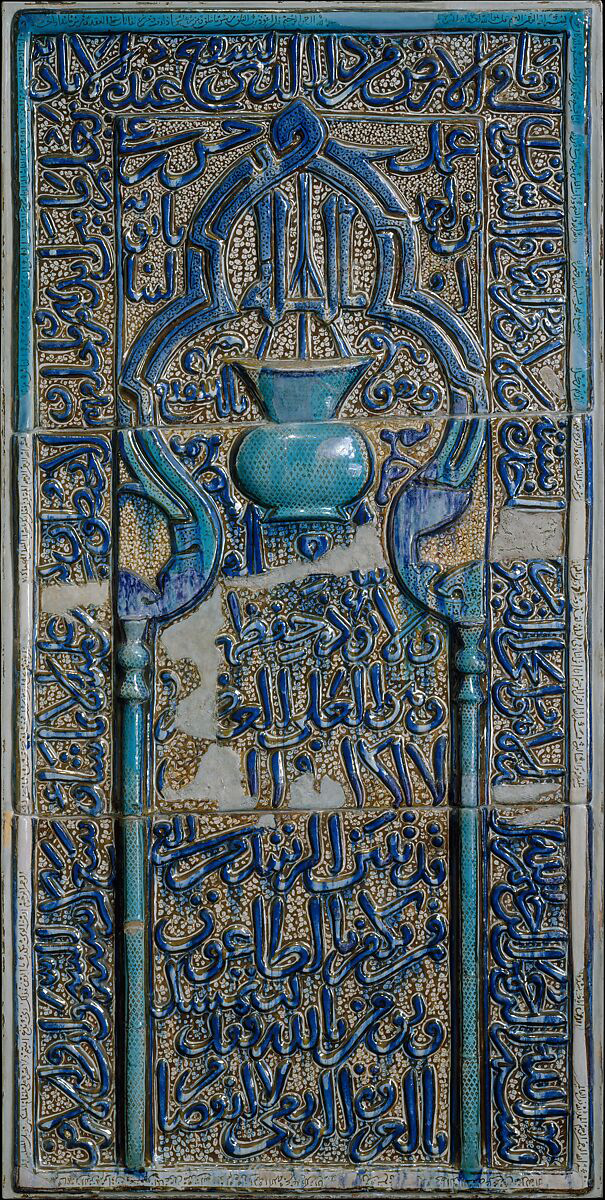

The third luster-tiled cenotaph that bears useful comparison to the one from the Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin is the example once in the tomb for the Sufi shaykh ʿAbdosamad in the shrine at Natanz.26 This cenotaph dates from the period in the early fourteenth century when most of the shrine was reconstructed and the luster revetment added. It was thus made only a few years after the one for the Emamzadeh Yahya dated 705/1305. Anaïs Leone, who has written extensively on the luster tiles from this period, estimated that the original luster-tiled cenotaph for ʿAbdosamad measured 3.46 x 2.46 meters, based on the length of the text in the frieze that once encircled it.27 Several tiles now dispersed to various museums likely belonged to this cenotaph. One is the three-tile tombstone (123.2 x 59.7 cm) displaying an epigraphic arch with suspended lamp now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (09.87; fig. 14). The relief inscription in the spandrels says that “Hasan b. ʿAli b. Ahmad Babawayh, the builder (al-bannaʾ) made (ʿamila) it.” He was the builder responsible for the renovations.28 A small inscription in luster added at the bottom says that “it was written (kutiba) in Shawwal of the year [70]9/March 1310 by the hand of the poor servant ʿAli b. Mohammad b. Fazlallah al-.… (the rest of the inscription is illegible).” He is an otherwise unknown luster potter.

Several tall (43.5 cm) corner panels, including two in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (40.181.8 and 40.181.9; fig. 15), likely belonged to this cenotaph, as did several frieze tiles from a long framing band (Metropolitan Museum of Art 15.76.4; fig. 16).

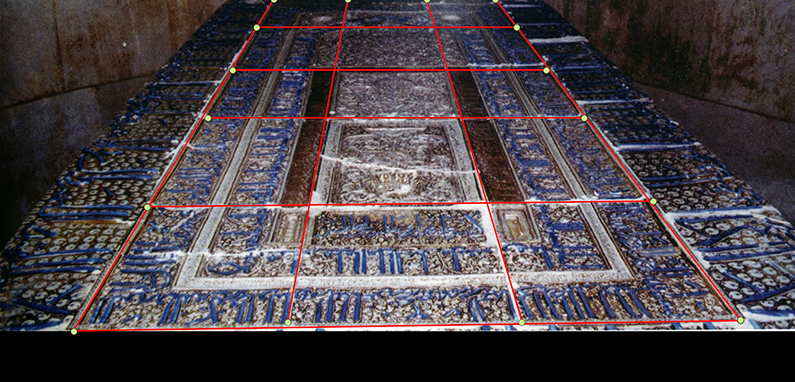

The three luster-tiled cenotaphs for Fatemeh Maʿsumeh in Qom, Habib b. Musa in Kashan, and ʿAbdosamad in Natanz, in addition to some ten sets of luster tombstones that once covered cenotaphs and remain in situ or have been removed to museums, help us to reconstruct the luster-tiled cenotaph for Emamzadeh Yahya once in the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin.29 All are cuboids, or solids with six faces. The flat upper surface has a central set of tiles (the so-called tombstone), displaying a niche or nested niches. The typical set contains three tiles set one atop the other. The one for Yahya is larger with four tiles (fig. 4), and the one for Fatemeh is exceptional in having fifteen tiles arranged in five rows (fig. 8).

The central tombstone on the cenotaph for Emamzadeh Yahya was likely encircled by an inscription band, as on the surviving cenotaphs for Fatemeh and Habib b. Musa and hypothesized for the one for ʿAbdosamad. Assuming that the luster cenotaph in the Emamzadeh Yahya had a similar border surrounding the central panel, the complete top would have measured around 2.71 x 1.37 meters (8.89 x 4.49 ft), and thus would have fit comfortably inside the wooden screen (marqad) observed by Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh.30 The sides of the cenotaph for Yahya likely had tall panels on the corners, as on the cenotaphs for Fatemeh at Qom and ʿAbdosamad at Natanz, and sides decorated with rows of luster-tiles alternating with monochrome-glazed tiles, as on those for Fatemeh in Qom and Habib b. Musa in Kashan. Unfortunately, we cannot identify any of the individual luster tiles from the cenotaph for Emamzadeh Yahya beyond the tombstone in the Hermitage, but we know that they must have been of the highest quality.31

These luster tiles attracted the attention of European and American collectors from the late nineteenth century when they were stripped from mosques and shrines during a two-phase process well documented in a 2000 essay by the Japanese scholar Tomoko Masuya. During a first phase from 1862 to 1875, most of the looted tiles comprised individual pieces from a few sites. A few tiles were already missing from the dado of the Emamzadeh Yahya by the time of Dieulafoy’s visit in 1881 (see the Timeline).32 During a second phase from 1881 to 1900, when European purses and appetites were growing, the looted tiles comprised larger ensembles from more sites. The two mihrabs and the cenotaph from the shrine at Natanz, for instance, seem to have been dismantled in the 1880s.33 The mihrab was stripped from the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin at this time as well. According to various sources, it was removed from the tomb at some point after Dieulafoy’s visit in 1881 and certainly before Friedrich Sarre’s visit in early 1900 and taken to Paris.34

The cenotaph from the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin may have been dismantled in the late nineteenth century at the same time as the mihrab in the tomb. According to museum records, the set of tiles from the cenotaph came to the Hermitage in 1925 from the Central Museum of the Technical Drawings of Baron A. L. Stieglitz (or the Stieglitz Central Museum of Decorative and Applied Arts), but had been acquired in Paris in 1913 from Madame Duffeuty.35 Clotilde Duffeuty was an important French dealer in Persian and Indian art at the turn of the twentieth century who sold many objects to the Musée Guimet and the Louvre in Paris.36 She owned several Persian luster tiles, including one from the beginning of the framing inscription around the mihrab dated Shaʿban 665/May 1265 taken from the Emamzadeh Yahya and now in Honolulu.37 She might have acquired the tombstone tiles from the same shrine at the same time.

Although all of the luster tiles have been stripped from the Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin, reconstructing the luster-tiled cenotaph dated 705/1305 confirms the shrine’s vibrancy in the early fourteenth century. As on the cenotaph in the tomb for Fatemeh at Qom, the tiles were designed to engage believers and enhance their religious experience by evoking many of the senses. Pilgrims would have recited the well-known Qurʾanic verses traced out with their fingers on the relief letters of the cenotaph as they circumambulated (see fig. 5).38 Several of the sets of tombstone tiles, including the one from the cenotaph for Fatemeh in Qom (see fig. 9), have round cavities or projecting roundels in the corners and elsewhere.39 The function of these small bowls and bosses is unknown, but they would have added visual engagement and might have encouraged pilgrims to reach out and touch them. The tomb would have been lit by hanging oil lamps that would have flickered, and incense burners may well have perfumed the air, as in the scene from a contemporary manuscript of Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh illustrating the funeral of Alexander (Iskandar) but likely representing the mourning for the Mongol ruler Oljaytu around the cenotaph in his tomb at Soltaniyeh (map).40 The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin would have reverberated and glowed with sound, sight, touch, and even smell.

Citation: Sheila Blair, “The Luster Cenotaph from the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin.” Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.

Notes

- Campo, “Burial.” ↩

- Good examples dating from the tenth century survive at Siraf on the Persian Gulf. See Lowick, Coins and Monumental Inscriptions, 90-97. ↩

- Watson, Persian Lustre Ware, is the best survey of the material, especially chapter 3 on technique. ↩

- Canby, Shah Abbas, 189. ↩

- Overton and Maleki, “The Emamzadeh Yahya,” 128. ↩

- Dieulafoy, La Perse, 148-49. ↩

- Overton, “Jane Dieulafoy in Varamin,” 16-17 (draft of article shared in advance of publication). ↩

- Blair, “Tiles for Tombs.” Many examples are cited on the Thesaurus d’Epigraphie Islamique under the search term marqad, including several from the Shah-i Zinda in Samarqand. ↩

- Overton, “Jane Dieulafoy in Varamin,” 17. ↩

- The inscriptions are recorded in Thesaurus d’Epigraphie Islamique, no. 34435, which also includes a long bibliography about the set. See also Blair, “Architecture as a Source,” 4-7 and fig. 3. ↩

- Watson, Persian Lustre Ware, 179; Leone, “New Data,” 342. ↩

- Watson, Persian Lustre Ware, 179; Blair, “Tiles for Tombs.” ↩

- Watson, Persian Lustre Ware, 179-80; Blair, “Tiles for Tombs.” On Abu Zayd, see most recently Quchani, Ahadith, 29-52, where he argues that the potter’s full name should be reconstructed as Sayyid Shams al-Din Abu Zayd Mohammad b. Abi Taher al-Hosayn b. Abi’l-Hosayn Zayd al-muqri al-Hasani al-Kashani al-Nishapuri and that he should be identified with the poet Baba Afzal. ↩

- Blair, “Luted letters,” 615 and note 16. ↩

- Blair, “Luted letters,” 614-15, discusses the different stages of adding inscriptions on luster tiles and vessels. ↩

- Modarresi-Tabatabaʾi, Torbat, vol.1, 46-50; Motaghedi, Hundred Thirty Years, figs. 12-14; Ghanooni and Sadeqhimehr, “Barrasī;” Blair, “Tiles for Tombs.” ↩

- I do not know exactly when the cenotaph was remodeled. It was in its original state when it was photographed in 1999 (see figs. 5–6), but the friezes have since been removed, as shown by Kianoosh Motaghedi’s 2023 photographs. I thank him warmly for providing me with this invaluable documentation. The cenotaph’s dimensions are often given erroneously. Modaressi-Tabatabaʾi (Torbat, vol. 1, 46) gave the dimensions as 2.95 x 1.20 x 1.20 m (repeated in Ghanooni and Sadeghimehr, “Barrasī,” 81, as 3 x 1.2 x 1.2 m), but then stated that the central panel comprised fifteen tiles, each 40 x 60 cm. Tabatabaʾi’s dimensions therefore refer only to the central panel, which Ghanooni and Sadeghimehr call the tombstone (luh-e mazar). This central tombstone is surrounded by a border of tiles measuring 24 cm high, so it is necessary to add some 50 cm to the length and width of the top to calculate the correct dimensions of the original cenotaph. ↩

- Modarresi-Tabatabaʾi, Torbat, vol. 1, 49, read the name of Mohammad’s grandfather as Abi’l-Hosayn, but Ghanooni and Sadeghimehr (“Barrasī,” 82, no. 2) suggested Abi’l-Hasan. A close look at their figure 4 shows that Modarresi-Tabatabaʾi’s reading of Abi’l-Hosayn is indisputably correct. ↩

- The adjective ṣīniyya meaning Chinese is sometimes used for porcelain. Here it means simply glazed ceramic. ↩

- Ghanooni and Sadeghimehr, “Barrasī,” figs. 8 and 9 show details of these inscriptions. ↩

- On his works, see Watson, Persian Lustre Ware, 179; updated in Blair, “Art as Text,” 413-14. ↩

- Pope, “New Findings,” 155-56 and fig. 7; Watson, Persian Lustre Ware, 136 and pl. 114. ↩

- Motaghedi, Hundred Thirty Years, fig. 35 and 40-45; Blair, “Tiles for Tombs.” ↩

- The tomb for Pir-e Bakran outside Esfahan also had tiles with animate beings. See Grbanovic, “Lost and Found,” 2 and note 230, where she lists other examples as well. ↩

- Unpublished lecture by Maryam Kolbadinejad, “The Ilkhanid Luster Tiles from the Imamzadeh Habib ibn-Musa,” presented to the 13th Colloquium of the Ernst Herzfeld Society University of Vienna, Department of Art History, July 6-9, 2017. ↩

- Leone, “New Data,” 348-53; Blair, “Medieval Persian Builder,” 394; Blair, “A Half Century of (Unanswered) Questions.” ↩

- Leone, “New Data,” 351. ↩

- Blair, “Stucco workers” and “A Half Century of Unanswered Questions.” ↩

- These luster tombstones are the subject of Blair, “Tiles for Tombs.” ↩

- The inscribed border runs around all four sides of the top so it is necessary to add 50 cm to both height and width of the 221 x 87 cm set in the Hermitage. ↩

- Many individual luster tiles are now available on the database Medieval Kashi Online, but it is impossible to trace any specific ones to the Emamzadeh Yahya. ↩

- Blair, “Luted Letters,” 634-35, distinguished the two types of tiles looted in the two phases. Dieulafoy, La Perse, 148, noted the ones missing from the Emamzadeh Yahya. ↩

- Leone, “New Data,” 346; Blair, “Luted Letters,” 634-35. ↩

- Blair, “Art as Text,” 416 and note 48. In the account of his travels in Iran published in 1911, the French librarian and collector Henry-René d’Allemagne, who himself owned luster tiles including one from the frieze at Natanz (illustrated in his Du Khorassan, vol. 2, 120), recounted that in a somewhat shady arrangement made in the last years of the late nineteenth century, one of Mozaffar al-Din Shah’s ministers found a way to acquire the tiles, which he brought to Paris in crates hidden in his master’s luggage. For several months they were displayed in a shop in the Rue du 4 Septembre. Collectors flocked to see them, but because of the owner’s demands, no one could buy them so they were eventually repacked in their crates and deposited in a stable in the Marbeuf quarter, where they were still a few months ago (Du Khorassan, vol. 2, 130-31). ↩

- Information supplied by Dmitry Sadofeev, Curator at the Hermitage, in an email of March 3, 2021. He noted that the museum inventories listed the original donor as Mme Duffenty but that he had realized this was a misspelling or misreading of Duffeuty. ↩

- The 81 works Duffeuty sold or gave (only a very few were donations) to the Louvre between 1889 and 1905, including many of their luster tiles, are available at https://collections.louvre.fr/en/recherche?q=duffeuty. ↩

- Blair, “Art as Text,” 418 and note 61, discusses her luster tile from the Emamzadeh Yahya mihrab. Duffeuty also owned a luster tile with a dragon likely from Takht-e Soleyman, sold at Christie’s on 5 March 2008, lot 4. ↩

- Donaldson, “Significant Mihrabs,” 118, noted how pilgrims in the tomb of Emam Reza at Mashhad paused to recite prayers when circumambulating the cenotaph. See Blair, “Luted Letters,” 633-38 and note 77. ↩

- Modarresi-Tabatabaʾi, Torbat, vol. 1, 90-91, calls them balls (guyi). ↩

- On the many connections between the illustration and the tomb at Soltaniyeh, see Blair and Thackston, “A Mongol Historian.” ↩

Bibliography

- Algar, Hamid and Parviz Varjāvand. “EMĀMZĀDA.” Encyclopaedia Iranica, 2020, https://dx.doi.org/10.1163/2330-4804_EIRO_COM_9042.

- Allemagne, Henry-René d’. Du Khorassan au Pays des Backhtiaris: Trois Mois de Voyage en Perse. 4 vols. Paris: Hachette, 1911.

- Blair, Sheila. “Architecture as a Source for Local History in the Mongol Period: The Example of Warāmīn.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, special issue: The Mongols and Post-Mongol Asia: Studies in Honour of David O. Morgan, 3rd series, 26, 1-2 (2016): 215-29.

- Blair, Sheila. “Art as Text: The Luster Mihrab in the Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art.” In ‘No Tapping around Philology’: A Festschrift in celebration and honor of Wheeler McIntosh Thackston’s 70th Birthday, edited by Alireza Korangy and Daniel Sheffield, 407-36. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2014.

- Blair, Sheila. “Cenotaph.” In Encyclopedia of Islam, 3rd ed., edited by Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, and Devin J. Stewart. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 2010/2, 129-40.

- Blair, Sheila. “A Half Century of (Unanswered) Questions.” Paper presented at the conference, “Le complexe de ‘Abd al-Samad à Natanz: contextes et décors/The complex of ‘Abd al-Samad, Natanz: contexts & décors,” Aix-en-Provence, 30 March 2023.

- Blair, Sheila. “Luted letters: The relief inscriptions on Kashan luster mihrabs.” In Inscriptions from the Islamic World, edited by Bernard O’Kane, Andrew Peacock and Mark Muehlhaeusler, 606-41. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2023.

- Blair, Sheila. “Stucco workers, luster potters, and builders: the case of Hasan ibn ʿAli ibn Ahmad Babawayh al-Vidguli.” In Stucco in the Architecture of Iran and Neighboring Countries: New Research – New Horizons, ed. Lorenz Korn, Studies in Islamic Art and Archaeology series, edited by Markus Ritter and Oya Pancaroğlu. Wiesbaden: Reichart Verlag, in press.

- Blair, Sheila. “Tiles for Tombs: Mihrab or Cenotaph Cover?” In Meaning in Islamic Art: Studies in Honour of Bernard O’Kane, edited by Heba Mostafa. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, in press.

- Blair, Sheila and Wheeler Thackston. “A Mongol Historian Looks at Art: Abu’l-Qasim Qashani’s description of Sultaniyya.” In Iranian Art from the Sasanians to the Islamic Republic: Essays in Honor of Linda Komaroff, edited by Sheila Blair, Jonathan Bloom and Sandra Williams. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, forthcoming 2024.

- Campo, Juan. “Burial.” Encyclopedia of the Qurʾan, edited by Jane McAuliffe, vol. 1, 263-65. Leiden: Brill, 2001.

- Canby, Sheila. Shah Abbas: The Remaking of Iran. London: British Museum Press, 2009.

- Dieulafoy, Jane. La Perse, La Chaldée et la Susiane: relation du voyage. Paris: Hachette, 1887.

- Donaldson, Dwight. “Significant Mihrabs in the Haram at Mashhad.” Ars Islamica 2, 1 (1935): 118-27.

- Fondation Max van Berchem. Thesaurus d’épigraphie islamique, https://maxvanberchem.org/fr/thesaurus-d-epigraphie-islamique.

- Ghanooni, Mohsen and Samaneh Sadeghimehr. “Barrasī-ye katībeh-ye kāshīhā-ye zarrīnfām-e mazār-e hażrat-e faṭemeh-ye maʿṣūmeh (s) dar qom [Study of the inscriptions on the Luster Tiles of the Shrine of Hazrat Fatemeh (s) in Qom].” Honarha-ye ziba 22, 2 (1396 Sh/ 2018): 77-88. [University of Tehran, JFAVA]

- Grbanovic, Ana Marija. “Lost and Found: The Ilkhanid Tiles of the Pir-i Bakran Mausoleum (Linjan, Isfahan).” Iran: Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies (2021): 235-54.

- Institut national d’histoire de l’art, Medieval Kashi Online, launched 2023, https://agorha.inha.fr/database/86.

- Leone, Anaïs. “New Data on the Luster Tiles of ʿAbd al-Samad Shrine in Natanz, Iran.” Muqarnas 38 (2021): 331-56.

- Lowick, Nicholas M. The Coins and Monumental Inscriptions. London: British Institute of Persian Studies, 1985.

- Masuya, Tomoko. “Persian tiles on European walls: Collecting Ilkhanid tiles in Nineteenth-Century Europe.” Ars Orientalis 30 (2000): 39-54.

- Modarresi-Tabatabaʾi, Hossein. Torbat-e Pākān. 2 vols. Qom: Chapkhaneh-ye Mehr, [25]25/1976.

- Motaghedi, Kianoosh. Hundred Thirty Years of Persian Luster Ware Studies. Tehran: Research Institute of Cultural Heritage & Tourism, 2018.

- Overton, Keelan. “Framing, Performing, Forgetting: The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin.” Platform, September 19, 2022, https://www.platformspace.net/home/framing-performing-forgetting-the-emamzadeh-yahya-at-varamin.

- Overton, Keelan. “Jane Dieulafoy in Varamin: The Emamzadeh Yahya through a Nineteenth-Century Lens.” Getty Research Journal 19 (spring 2024). [draft of article shared during writing; since published]

- Overton, Keelan and Kimia Maleki. “The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: A Present History of a Living Shrine, 2018-20.” Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World 1 (2020): 82-111.

- Pope, A. U. “New findings in Persian ceramics of the Islamic period.” Bulletin of the American Institute for Iranian Art and Archaeology 5, 2 (December 1937): 149-69.

- Quchani [Ghouchani], Abdullah. Aḥādīth-e kāshīhā-ye zarrīnfām-e ḥaram-e moṭahhar-e emām reżā [Discussion of the Luster Tiles in the Blessed Shrine of Emam Reza]. Mashhad: Sazman-e Ketabkhanehha, 1397 Sh/2018.

- Watson, Oliver. Persian Lustre Tiles. London: Faber & Faber, 1985.