8Kufic Qurʾan manuscript with an alleged signature of Emam ʿAli endowed to the tomb of Emam Reza at Mashhad

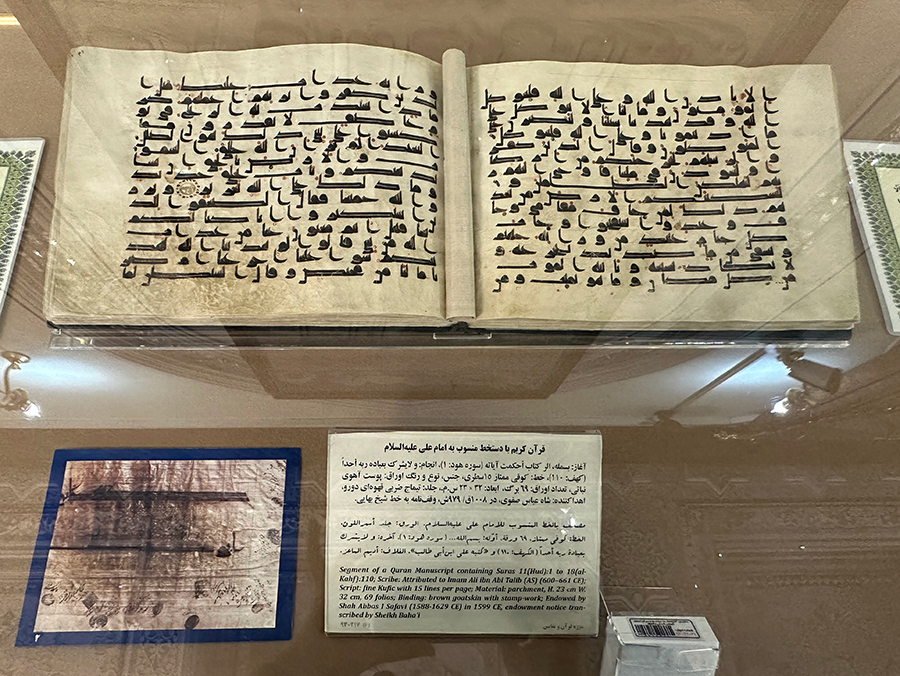

Near East, 9–10th century Ink and gold on parchment H. 9.1 in. x W. 12.6 in. (H. 23 cm x W. 32 cm) Astan-e Qods-e Razavi Library, inv. no. 6 Photograph by Yui Kanda, May 2023

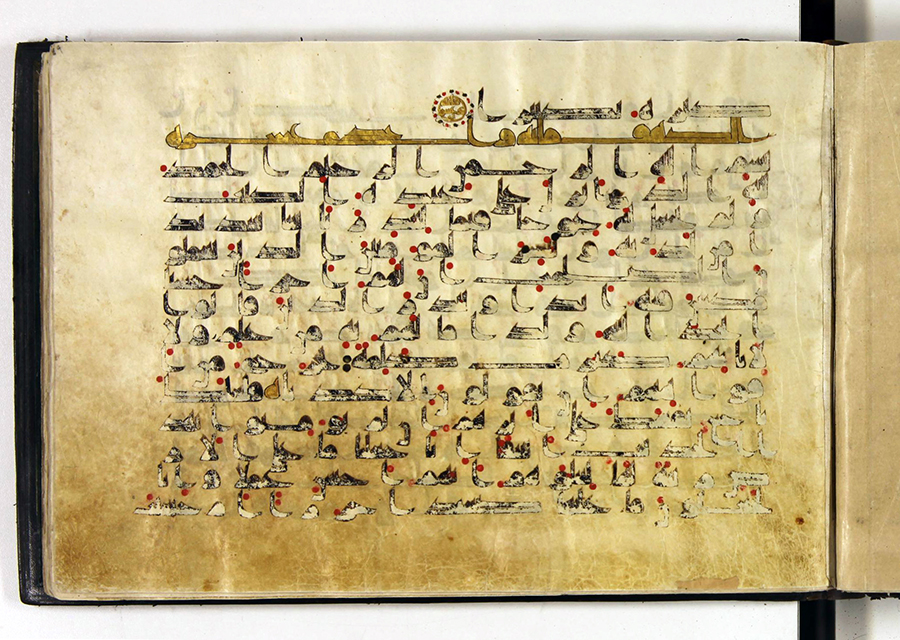

A highlight of the collection of the Astan-e Qods-e Razavi Library in Mashhad (map) is a horizontal format, partial Qurʾan manuscript on parchment. This volume would have been part of a multi-volume set, and the majority of its 68 folios (1b–68a) date to the ninth–tenth century. It begins with an ornate double frontispiece (fols. 1b–2a), and the text pages that follow (fols. 2b–68a) contain 15 lines of Kufic in a script classification known in scholarship as D.1 (Déroche 1992, 36–37, 43–45). The text is transcribed in black ink, vocalized with red dots, and spans from the beginning of sura Hud (11) to the end of sura al-Kahf (18).

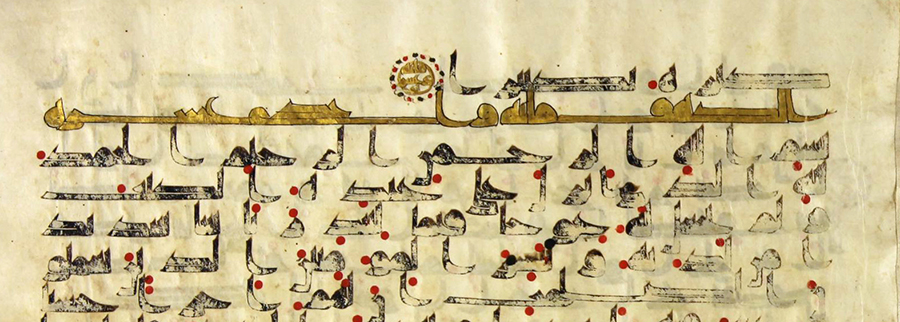

Each chapter heading is in gold outlined in black ink (fig. 2). Verse markers in the shape of a stylized letter ha indicate groups of five verses, whereas rosettes with gold letters, surrounded by black and red dots, mark either groups of ten verses or the ending of a sura (fig. 2).

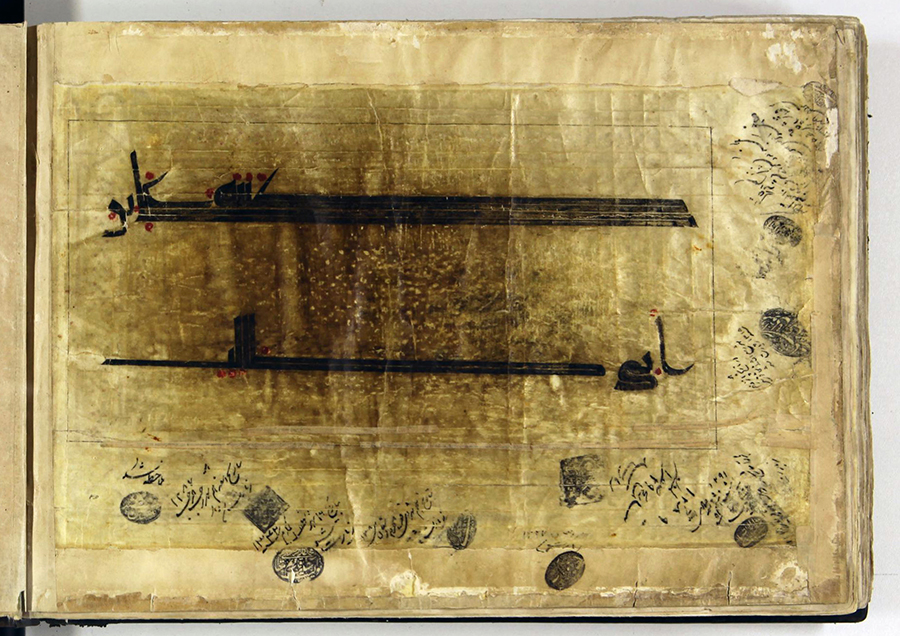

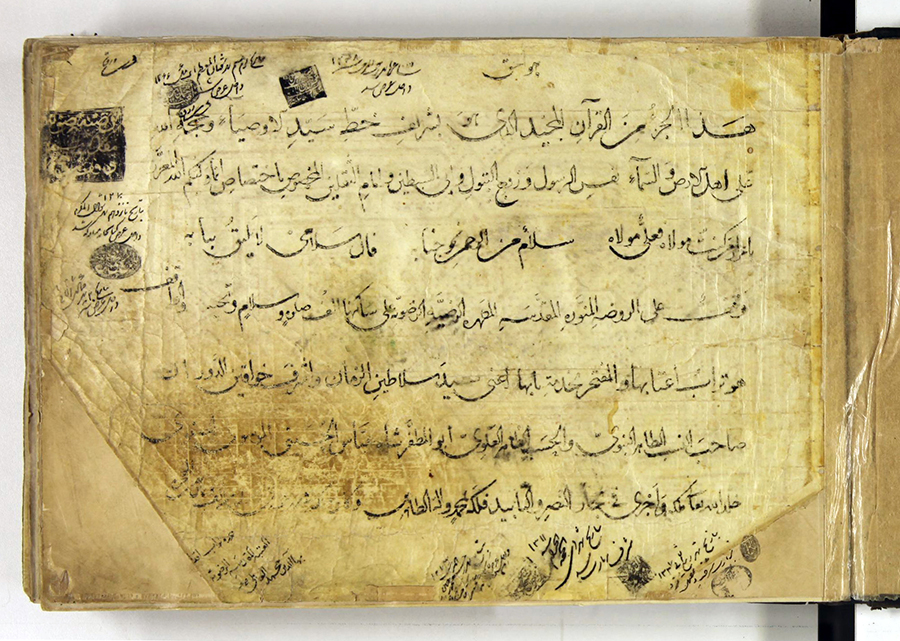

In contrast to the majority of the textblock, the first and last pages contain later additions, including many inscriptions and seals executed on various occasions. The last page features a fake colophon inscribed in two large lines of Kufic script across the page (fig. 3). It reads:

كتبه علي بن

ابي طالب

ʿAli, the son of Abu Taleb, wrote it

According to this fake colophon, the scribe was the first Shiʿi Emam, ʿAli (d. 661), the son-in-law of the Prophet Mohammad. A recent study by Morteza Karimi-Nia identifies forty manuscripts signed by or attributed to Shiʿi Emams, including this example, in the collection of the Astan-e Qods-e Razavi Library (Karimi-Nia 2023, p. 410–13).

On the first page, there is an attestation of the manuscript’s transcription by Emam ʿAli, followed by information about the endower and the year it was endowed to the tomb of Emam Reza (d. 818), the eighth Shiʿi Emam, in Mashhad (fig. 4). This information was written by the prominent Shiʿi scholar Bahaʾ al-Din ʿAmeli (d. 1621). According to this waqf (endowment) note, the manuscript was gifted to the tomb by Shah ʿAbbas I (r. 1588–1629), the fifth shah of the Safavid dynasty, in Jumada I 1008/November–December 1599. It should be emphasized that this represents one of the earliest donations of books made by Shah ʿAbbas I to Shiʿi and Sufi tombs in Iran and Iraq. The shah is best known for his large-scale endowment of Persian manuscripts in 1017/1608–9 to the shrine of Shaykh Safi in Ardabil (see, for example, the Mantiq al-tayr of 892/1487).

After reclaiming Mashhad from a decade-long Uzbek occupation in 1598, Shah ʿAbbas I began making regular pilgrimages on foot to the tomb of Emam Reza (Melville 1996). His visit to the tomb in the same month that this Kufic Qurʾan was endowed may suggest that his donation of the manuscript aimed not only to reinforce the religious significance of the tomb but also to legitimize his own pilgrimage.

The exact details of how, where, and when Shah ʿAbbas I acquired this codex remain unclear. However, its ‘afterlife’ can be partially reconstructed through an analysis of primary sources and the codex itself. In his Arabic biography of Sunni and Shiʿi scholars, ʿAbdallah Afandi al-Esfahani (d. 1717–18) claims to have seen two Qurʾans in the treasury of the tomb of Emam Reza. According to him, one was inscribed with “كتبه علي بن ابي طالب” and the other with “كتبه علي بن ابو طالب.” He states that these were among the Kufic Qurʾans in the handwriting of the Emams that were endowed to the tomb (Afandi al-Esfahani 1401–15/1980–95, 3:157). It is possible that the first Qurʾan is the manuscript discussed here.

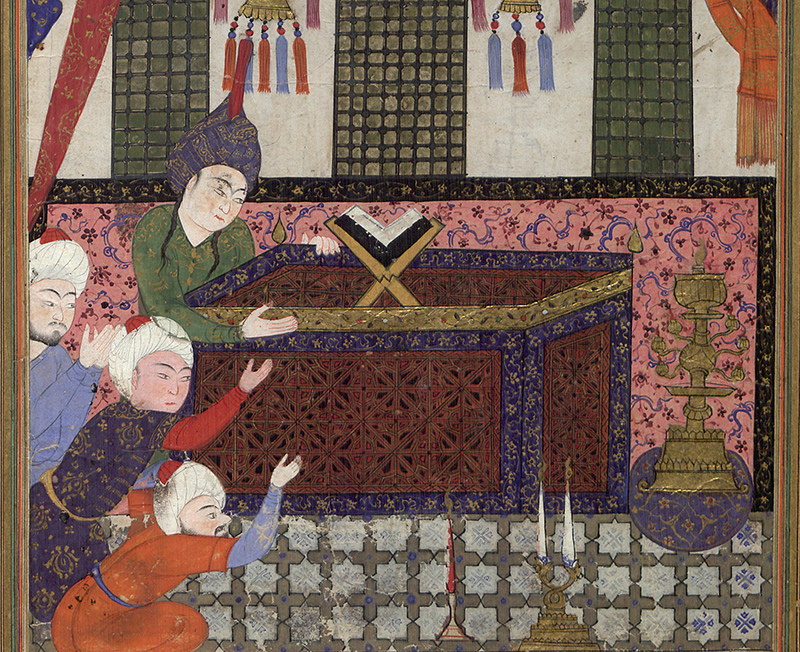

The damaged surface of the page with the fake colophon (see fig. 3), which is noticeably different from the other pages, suggests that it may have been handled by visitors to the grave, as if it were a relic. To envision how the manuscript might have been displayed and used, we can consider a contemporaneous Safavid illustration depicting pilgrims at the tomb of Emam Reza (figs. 5–6).

Frequent inspection records on the first and last pages of this volume (see figs. 3–4) indicate the importance of inspecting manuscripts preserved in the Shrine of Emam Reza over the decades and centuries. Today, Qurʾan manuscript no. 6 is on display in the Museum of Qurʾan and Exquisite Objects, situated on the west side of the Kawsar courtyard (map). It is displayed in a case in front of a large Qurʾan folio in muhaqqaq script attributed to the Timurid prince Baysonghor b. Shah Rokh (d. 1433) (fig. 7).

Sources:

- Afandi al-Esfahani, ʿAbdallah. Riyāḍ al-ʿulamāʾ wa ḥiyāḍ al-fuḍalāʾ. Edited by al-Sayyed Ahmad al-Hosayni. Qom: Maktabat Ayat Allah al-Marʿashi al-Najafi. 7 vols. 1401–15/1980–95.

- Déroche, François. The Abbasid Tradition: Qurʾans of the 8th to 10th Centuries AD. New York: Nour Foundation in association with Azimuth Editions and Oxford University Press, 1992. [WorldCat]

- Karimi-Nia, Morteza. “The Qurʾānic Codices and Fragments Ascribed to Imām ʿAlī and Other Shīʿa Imāms: Forged Colophons or Historical Truths?” Journal of Islamic Manuscripts 14 (2023): 396–441. [Brill]

- Melville, Charles P. “Shah ʿAbbas and the Pilgrimage to Mashhad.” In Safavid Persia: The History and Politics of an Islamic Society, Pembroke Persian Papers 4, edited by Charles P. Melville, 191–229. London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 1996.

Citation: Yui Kanda, “Kufic Qurʾan manuscript with an alleged signature of Emam ʿAli endowed to the tomb of Emam Reza at Mashhad.” Catalog entry in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.