7Tomb covers (qabr-push)

Many emamzadehs and shrines in Iran, and beyond

This photograph:

Tomb cover of Yahya b. ʿAli

Emamzadeh Yahya, Varamin

Iran, contemporary period

Embroidery on unknown fabric

Photograph by Hamid Abhari, 2021

Tomb covers (قبرپوش, qabr-push; also known as pushesh-e qabr) encompass a range of textiles used to clothe the cenotaphs of venerated figures in emamzadehs, Sufi shrines, and other funerary sites. Some were made to function specifically as a tomb cover, while others could be luxury textiles, carpets, or fragments of the kiswa (textiles made to cover the Kaʿba) used occasionally for this purpose. Many textiles labeled as tomb covers in museum and exhibition catalogs may have been multi-purpose objects used as floor carpets, coffin covers, or banners for mourning ceremonies, such as those held during the month of Moharram (see no. 5). Textiles used as tomb covers range from plain cloths to finely knotted, elaborately designed, and densely inscribed complex weaves made of wool, cotton, silk, and gold and silver threads. Alongside floor carpets, tomb covers comprise an important but understudied category of devotional objects commissioned for, and endowed to, significant sites of pilgrimage and veneration.

Tomb covers can sit directly on the cenotaph or clothe a larger structure built around the cenotaph usually made of wood (known as sanduq, صندوق) (fig. 1). In the latter case, the textile cover can be referred to as a sanduq-push (صندوق پوش). The act of veiling the cenotaph in multiple layers was simultaneously protective (shielding it from harm and pollution), devotional (as a way to venerate the deceased), and symbolic (as a marker of the status of revered figures among their followers). The most luxurious covers were likely displayed on cenotaphs mainly during special religious occasions.

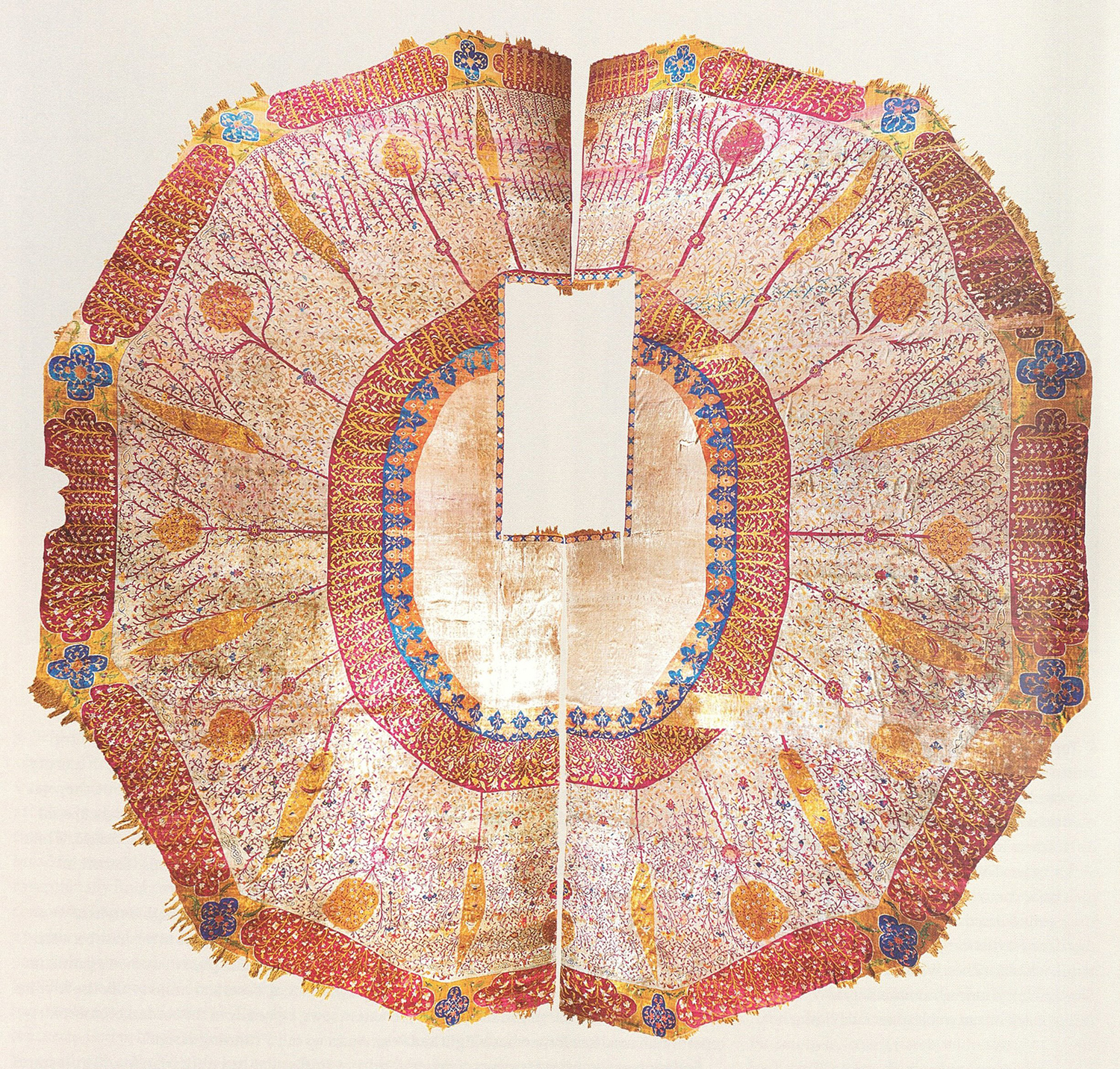

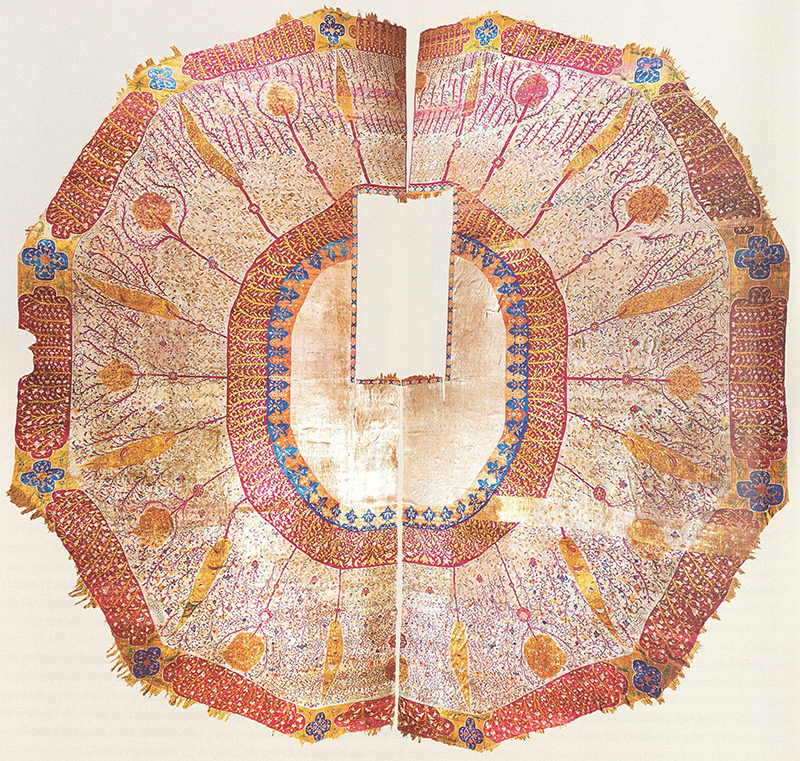

Some covers, like that made for the tomb of Emam Reza (map) were designed to closely fit the shape and dimensions of the sanduq (fig. 2). Others were (and still are) shaped as a simple rectangle to sit on top or hang freely on the sides of a stone cenotaph or wooden sanduq. While heavier textiles and qalichehs (قالیچه, small carpet) are held in place by their own weight, thinner rectangular covers are held in place by ritual and votive objects placed on top of the grave, such as metal candlesticks or manuscripts, as is in the Emamzadeh Yahya or the Astaneh (shrine) of Shah Neʿmatollah-e Vali (d. 1431) in Mahan (figs. 3–4). Rocks can also be used in the corners, as in the tomb of Shah Khalilollah-e Neʿmatollahi in India, which I include here to underscore the commonality of this tradition (fig. 5).

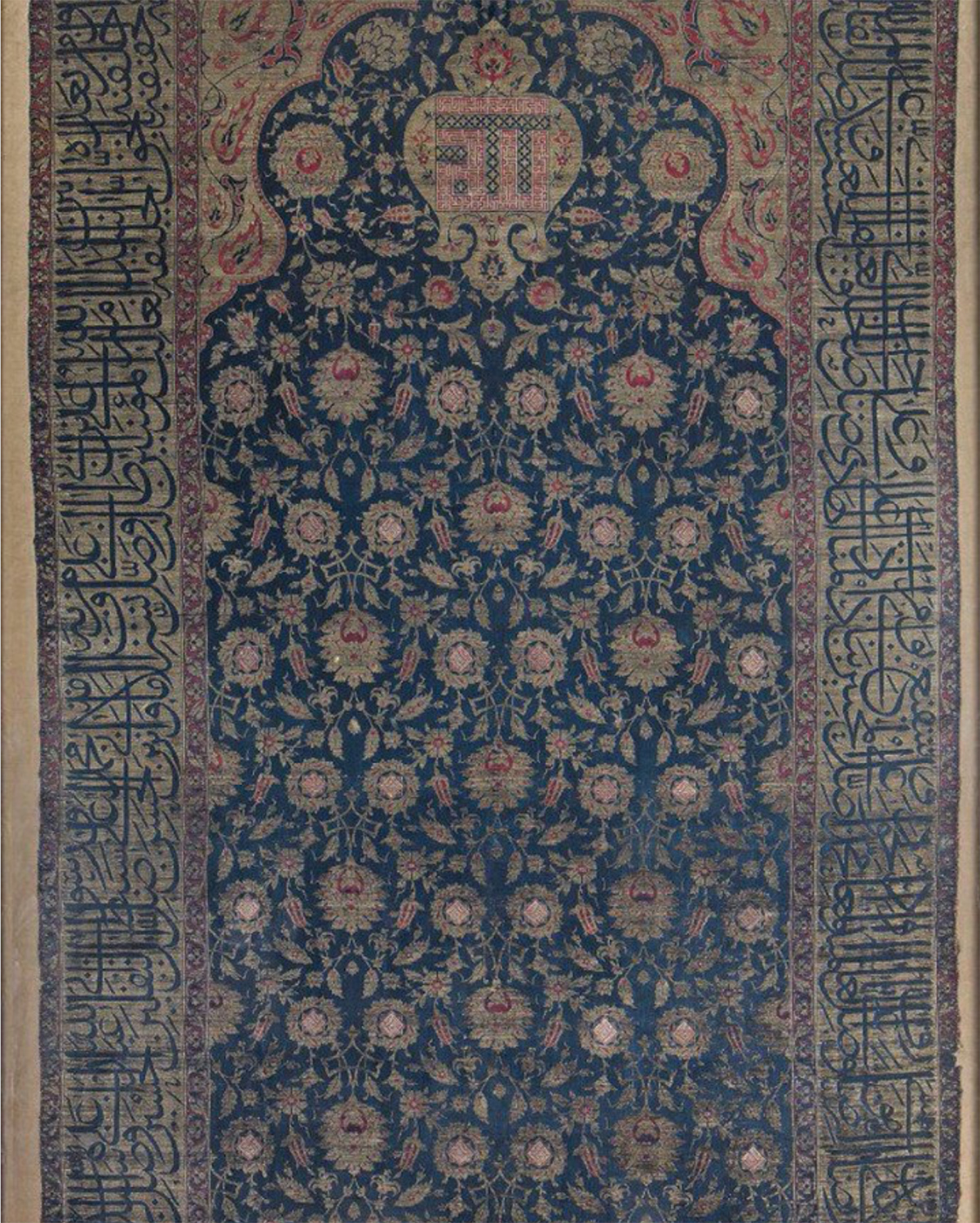

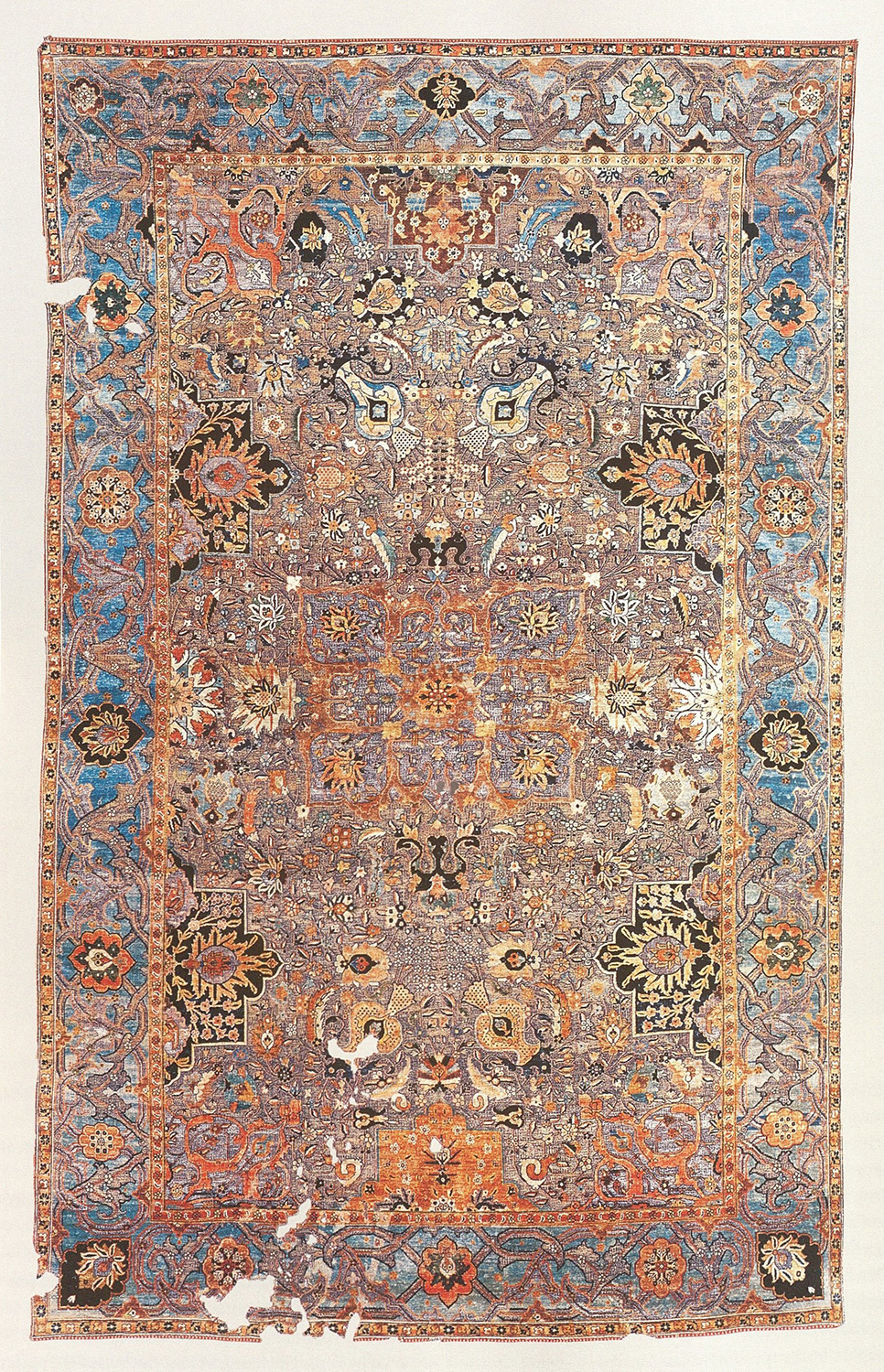

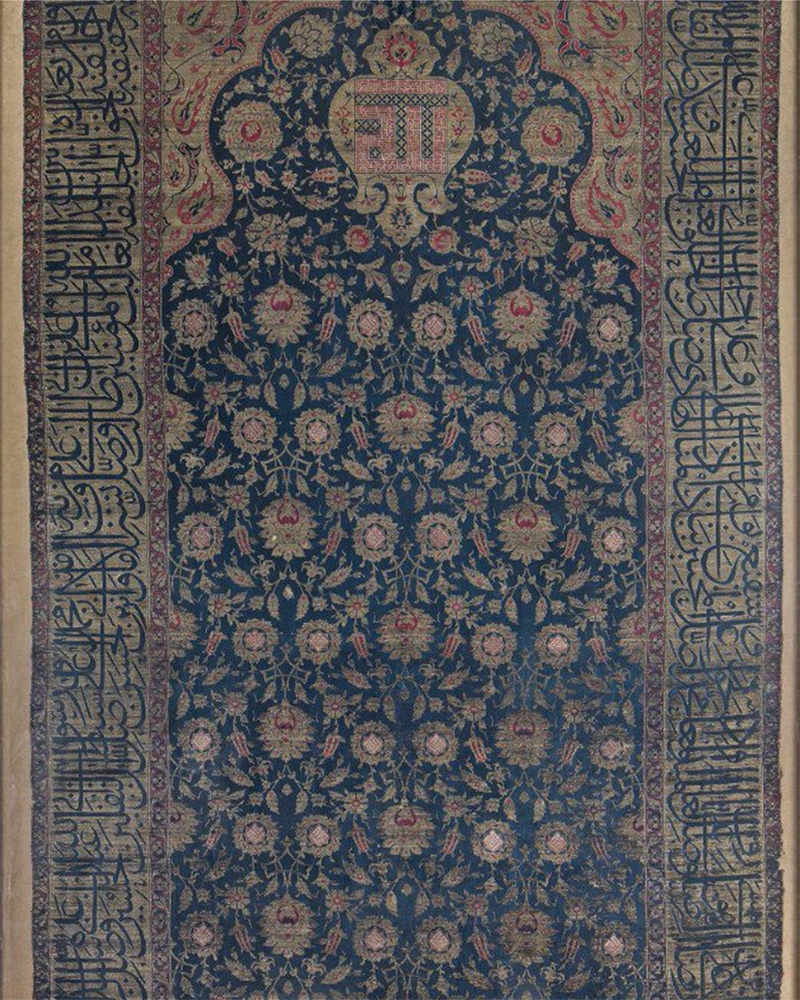

The designs and layouts of tomb covers vary widely. Mihrab motifs (fig. 6), floral scrolls, and landscape and garden designs are featured on textiles believed to have been used as tomb covers. A silk pile tomb cover now in the Gulbenkian Museum (T.113) and a carpet in the Cincinnati Museum of Art (fig. 7) are distinguished by so-called Vaq Vaq motifs comprised of floating heads of humans, animals, and beasts among a meandering scroll design (Cohen 2001, p. 85; Melikian-Chirvani 2007, p. 266–69). Speculated to be products of the sixteenth or twentieth centuries, both have been attributed to the shrine of Emam Reza in Mashhad, perhaps as a result of suggestions by Arthur Upham Pope (d. 1969), but this attribution remains unconfirmed.

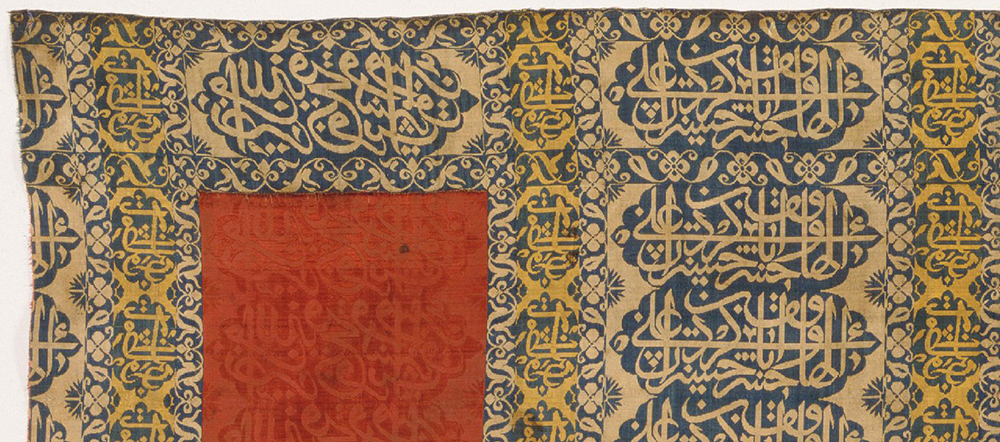

Several surviving Safavid (1501–1722), Ottoman (ca. 1299–1922), and Qajar (1779–1924) textiles attributed as tomb covers are characterized by their complex and dense patterns of epigraphy, and many of them may have been designed as banners (Mashhadi Noosh Abadi and Ghiasian 2024; Blair 1998, p. 179–80; The Arts of Islam 1976, p. 109). Repeated bands of inscriptions arranged in stripes, zigzags, and around or inside cartouches contain Qur’anic citations, prayers to the Prophet and Shiʿi Emams, and at times commissioned poetry, historical information about the endowment, or signatures of craftspeople (figs. 8–9; see fig. 2). Mirror writing was also common, as can be seen in a silk textile attributed to the 1600s that may have been used as a tomb cover (fig. 9) and a similar Qajar-period example found in Esfahan and preserved in Iran’s National Museum (no. 20223) (Mashhadi Noosh Abadi and Ghiasian 2024, p. 53–54). Both contain repeated bands of the verse ‘help from Allah and an imminent victory’ (نصر من الله و فتح قریب; Q 61:13), and invocations to Emam Hosayn, among other inscriptions.

Musealization and colonial practices of collecting have resulted in the dispersal of many carpets and textiles endowed to shrines across international collections. Due to fragmentary or unknown provenances and the frequent absence of site-specific formal or epigraphic features, it remains impossible to determine the original contexts of many tomb covers removed from their architectural settings. Some luxury tomb covers, however, still remain in situ or in museums attached to major shrines, and as a result can be better understood in their context. Examples include the aforementioned sanduq-push in Mashhad (fig. 2) and a so-called Polonaise carpet believed to have covered the cenotaph of Shah ʿAbbas II (r. 1642–66) in his tomb in the Shrine of Fatemeh Maʿsumeh in Qom (map) (Zuleh 2019) (fig. 10).

Textual and photographic sources can remedy some of the gaps created by the removal of these objects from their original settings. Frequent mention of these textiles by European travelers indicates their widespread use and aesthetic significance. Among such examples are Sir John Chardin’s (1643–1713) account of the textiles in the tomb of Shah ʿAbbas II in the Shrine of Fatemeh Maʿsumeh at Qom in which he describes a gold brocaded cloth covering the cenotaph. He also seems to indicate that this cover was attached to the carpets covering the floor by silk strings that ran through golden rings (Chardin 1686, p. 399). This brocaded cover was likely in place before the aforementioned carpet used as a tomb cover (fig. 10) and the making of the famed twelve-sided carpet covering the immediate floor around Shah ʿAbbas II’s cenotaph (Zuleh 2019, p. 154–55) (see no. 20) (fig. 11).

In his account of the Ardabil shrine (map), Adam Olearius (1599–1671) noted the crimson velvet textiles covering the sanduq of the Sufi Shaykh Safi al-Din (d. 1334) (Olearius 1662, p. 172; Rizvi 2011, p. 52). A nineteenth-century photograph taken from the entrance to the domed tomb of Shaykh Safi shows inscribed textiles covering the top of his elaborately carved and large wooden sanduq, while the smaller cenotaphs of his descendants are covered by numerous candlesticks and what looks like a finely knotted carpet (fig. 12).

Inventories of shrines and emamzadehs are another significant source. The Athar al-razawiyyah (آثار الرضویه), a catalogue of endowments and deeds to the shrine of Emam Reza in Mashhad compiled in 1899, contains a list of the textiles with their sizes and qualities but does not describe them in detail (Morikawa and Werner 2017, p. 148, 205, 215, 224–25, 236; Kanda 2020, p. 127). Another inventory is of the furnishings, books, utensils, and other such objects belonging to the Ardabil shrine, compiled on the basis of an inspection carried out in 1172/1795. This inventory lists a group of fifty-five “sanduq-pushs and other textiles,” including silk and velvet covers, several of which featured inscriptions and designs of trees and figures, and a group of qalichehs in sizes that may have been appropriate for their use as tomb covers (Mashkur 1971, p. 371–78; Morton 1977, p. 471).

Sources:

- Blair, Sheila. Islamic Inscriptions. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998.

- Chardin, John. The travels of Sir John Chardin into Persia and the East Indies: the first volume, containing the author's voyage from Paris to Ispahan: to which is added, The coronation of this present King of Persia, Solyman the Third. London: Printed for Moses Pitt in Duke-Street Westminster, 1686.

- Cohen, Steven. “Safavid and Mughal Carpets at the Gulbenkian Museum.” Hali 114 (2001): 75–88, 99.

- Kanda, Yui. “Persian Verses and Crafts in the Late Timurid and Safavid Periods.” PhD diss., The University of Tokyo, 2020.

- Mashhadi Noosh Abadi, Mohammad and Mohammad Reza Ghiasian. “Tajalli-ye mazamin-e ʿAshura-yi dar mansujat-e abrishami-ye avakher-e dore-ye Safavi” (The Emergence of ʿAshura Themes in the Silk Textiles of the Late Safavid Period). Iranian Journal for the History of Islamic Civilization 56, 1 (2024): 37–62. [JHIC] [Academia.edu]

- Mashkur, Javad. Nazari be tarikh-e Azarbaijan va athar-e Bastani va jamiyat shenasi-ye an (Perspectives on the History of Azerbaijan, its Monuments and Demographics). Tehran: Bahman, 1971 [1349]. [WorldCat]

- Melikian-Chirvani, Assadullah S. Le chant du monde, l’art de l’Iran safavide: 1501-1736. Somogy, Paris, 2007.

- Morikawa, Tomoko and Christoph Werner, eds. Vestiges of the Razavi Shrine: Āthār al-Rażavīya: A Catalogue of Endowments and Deeds to the Shrine of Imam Riza in Mashhad. Tokyo: Toyo Bunko, 2017.

- Morton, A. H. “Vase-Technique Carpets and Kirman: Carpets at Ardabil in the 18th Century.” Oriental Art 23, 4 (1977): 470–71.

- Olearius, Adam. The Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors sent by Frederick, Duke of Holstein. Translated by J. Davies. London: J. Starkey, 1662.

- Rizvi, Kishwar. The Safavid Dynastic Shrine: Architecture, Religion and Power in Early Modern Iran. London: I. B. Tauris, 2011.

- The Arts of Islam: Hayward Gallery, 8 April-4 July 1976. London: The Arts Council of Great Britain, 1976. (exhibition catalog)

- Zuleh, Turaj. “Carpets from the Tomb of Shah Abbas II.” Hali 200 (2019): 152–59.

Citation: Peyvand Firouzeh, “Tomb covers (qabr-push).” Catalog entry in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.