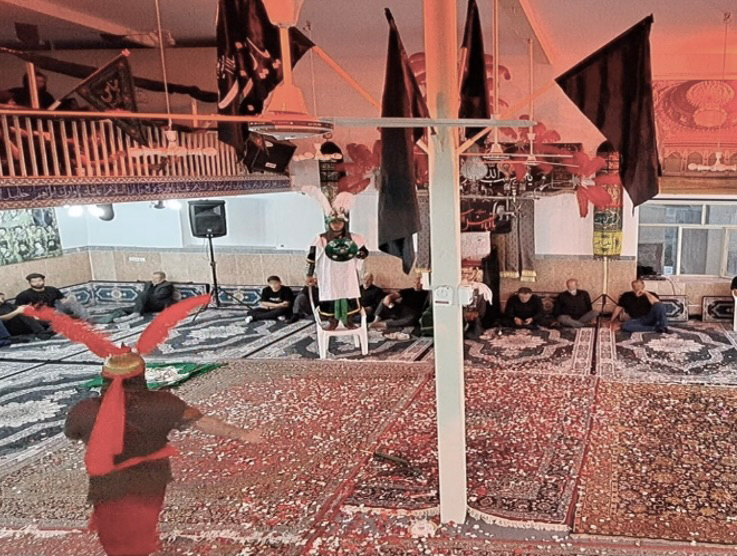

47Performance of the martyrdom of ʿAli Akbar in the Payambar-e Azam Mosque at Darbandsar

Payambar-e Azam Mosque, Darbandsar, Tehran Province (map) Moharram 1446/Tir 1403/July 2024 Screenshot from a video by Sara Khalili Jahromi, 2024

The martyrdom of ʿAli Akbar is one of the most popular episodes from the Karbala story performed during Moharram (see no. 46). In this entry, I describe a performance that took place at the Payambar-e Azam Mosque in Darbandsar, a village in the Rudbar-e Qasran Rural District of Shemiranat County, just north of Tehran. Although taʿziyeh is typically staged on a saku (a raised central platform), the Darbandsar performance occurs on a carpeted flat floor within the hosayniyeh. Men sit on the floor around the stage on the ground level, and women sit on the upper level.

The figure of ʿAli Akbar holds a significant place in the narrative of Karbala, symbolizing the tragic loss of a young son. Some sources describe ʿAli Akbar as Emam Hosayn’s eldest son, while others consider him younger than Zayn al-Abidin. In taʿziyeh, he is portrayed as a handsome adolescent or young man who closely resembles the Prophet Mohammad. His resemblance is so striking that, on the battlefield, Shemr (the killer of Emam Hosayn) mistakes him for the Prophet.

The performance of the martyrdom of ʿAli Akbar typically begins with a pishkhani, a dirge or song performed collectively by the taʿziyeh actors shortly before the start of the play. In the Darbandsar performance, it is sung solo by the actor playing ʿAli Akbar, a young man well-trained in singing, accompanied by the other actors in a chorus (aud. 1). The actors use microphones, and a group seated in the corner plays drums, cymbals, and trumpets.

Audio 1. Listen to the prelude. Recording by Sara Khalili Jahromi, 2024.

After a short chant by ʿAli Akbar’s mother, Layla or Umm-e Layla, the play opens with Umar Ebn-e Saʿd (the commander of the opposing forces) challenging Hosayn to the battlefield, mocking him as a king without an army. In response to his father’s cry “Is there anyone to help me?” (هل من ناصر ینصرنی؟), ʿAli Akbar volunteers to fight. To seek his father’s consent, he invokes the binding of Esmaʿil and asks his father to sacrifice him as Ebrahim (Abraham) did with his son. Permission is not granted. This dialogue is followed by a dramatic scene in which Zaynab (Emam Hosayn’s sister) sends her two sons to the battlefield. She implores her brother to accept this sacrifice that she presents as trivial, comparing it to Solomon’s acceptance of the ant’s offering, which was merely a locust’s leg.

After his cousins’ death, ʿAli Akbar again seeks Hosayn’s permission (fig. 2). The lengthy dialogue culminates in a poignant moment when, upon ʿAli Akbar’s insistence, Hosayn dresses him in a shroud but sends him to his mother for her permission. This scene is the most emotionally charged of the performance and begins with ʿAli Akbar calling to his mother:

از خیمهگه بیرون بیا با چشم تر لیلا! ای بی پسر لیلا! ای خونجگر لیلا

آرام جانت میرود، آرام جانت میرود، سوی سفر لیلا! ای خونجگر لیلا! ای تاج سر لیلا!

Come out of the tent with tearful eyes, Layla, mother bereft of her son, grief-stricken Layla.

Look how the balm of your soul departs, balm of your soul departs, grief-stricken Layla, crown of my head Layla.

The performance lasts about three hours and focuses on the sorrowful, extended farewell between ʿAli Akbar and his family (fig. 3). The most dramatic scene in this interpretation is the dialogue between ʿAli Akbar and his mother. After reluctantly consenting to ʿAli Akbar’s decision to go to war, Layla asks him to delay his departure so she can hold symbolic marriage rites for him. She wishes to fulfill her long-held desire to see him wed, although some historical sources (Majlesi, Beḥār al-ʾAnwār 46:163–64) indicate that ʿAli Akbar was not single at the time of his martyrdom.

The marriage celebration involves singing, ʿAli Akbar’s mother combing his hair, and men arriving with large trays on their heads filled with presents, fruits, and sweets known as khoncheh in Persian. They also throw rose petals on the groom’s head and sing:

آرید گلاب و شانه بهر اکبر یگانه، ای خدا علی جوانه، ای خدا علی جوانه.

زاده لیلا، سرو دلآرا، زاده لیلا، سرو دلآرا، ای شه گردون تبارک، شادیات علی مبارک.

Bring rose water and a comb for the peerless Akbar; Oh my God, ʿAli is young.

Layla’s son, charming cypress, you, the king of the world, be blessed by God, joyful be your happiness.

ʿAli Akbar’s traits foreshadow those of his cousin Qasem, and the concept of javan-e nakam or ‘unmarried youth,’ is further developed in Qasem’s marriage play. After this lengthy scene, accompanied by the spectators’ sobs and cries, ʿAli Akbar sends letters of farewell to his sister and fiancée and says goodbye to his baby brother. He then goes to the battlefield, a significant moment depicted in the main photograph above (he stands on the chair). He is ultimately killed, and his body is carried on the shoulders of the youth of Banu Hashim to the tent (fig. 4).

By extending the farewell scene to about three hours and highlighting instinctive parental emotions and evoking unfulfilled conjugal desires (recall the symbolic marriage), this performance deeply engages the audience and makes it one of their favorites. In this portrayal, Hosayn is depicted more as a grieving father than a spiritual superhero, profoundly affected by the death of his son and suffering like anyone in the audience who has lost a loved one.

Sources:

- Majlesi, Muhammad Baqir. Beḥār al-ʾAnwār, vol. 46. Beirut: Dar Ihya al-Turath al-Arabi, 1361 Sh/1403 AH/1983.

Citation: Sara Khalili Jahromi, “Performance of the martyrdom of ʿAli Akbar in the Payambar-e Azam Mosque at Darbandsar.” Catalog entry in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.