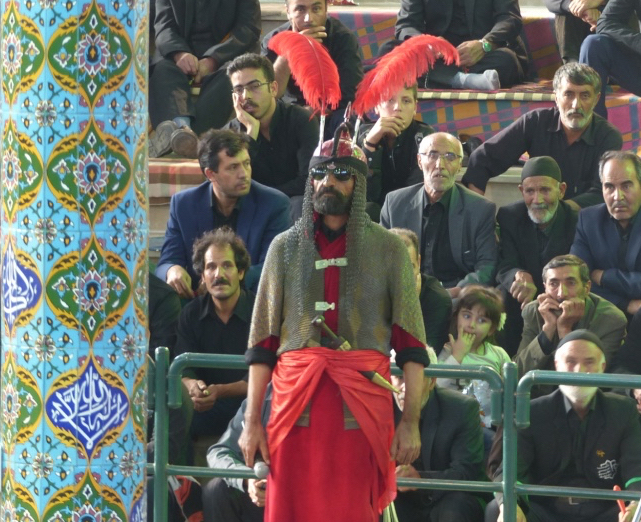

46Taʿziyeh-khani

Shemr-khan: taʿziyeh performer portraying the arch-antagonist Shamer ‘Shemr’ b. zil-Jawshan, killer of Emam Hosayn Hosayniyeh-ye ʿAzam, Armaghankhaneh, Zanjan Province (map) 8 Moharram 1439/29 September 2017 Photograph by Lucy Deacon and Mathilde Wilkens

Taʿziyeh-khani also known as shabih-khani, is a Shiʿi form of devotional drama. At the heart of the repertoire is a cycle of plays performed during the month of Moharram to commemorate the martyrdoms of the third Emam of Shiʿi Islam, Hosayn b. ʿAli b. Abi Taleb, and his supporters on the plain of Karbala in the year 61/680. Hosayn and his family’s journey to Karbala, the siege of their camp, the valiant combat of the men and boys before martyrdom, and the journey of the captives (women, girls, and the fourth Emam Zayn al-ʿAbedin) to the court of Yazid b. Moʿawiyyah in Damascus are dramatized in episodic form. These plays are performed daily during the first ten to twelve days of Moharram. While much of their plot concurs with the reports of historical sources, interventions by angels, dervishes, and foreigners, the apparition of jinn (genies), and the significant treatment of the perspective of the women enrich the narrative texture.

The taʿziyeh tradition dates back more than three centuries. The oldest extant script of a taʿziyeh play, a rendition of Gharat-e khaymeh-ha (The Plunder of the Camp), is dated 1136/1724 (for an edition and photographs, see Fath-Ali Baygi and Daryai 1394 Sh/2015, p. 19–81). The scribe states that the composer, one ‘Fanaʾi’, was ‘late’ by the time of his transcribing the copy in question, on which basis Fanaʾi appears to have been a Safavid-era composer. The script’s origin is not known, but Fanaʾi’s full name (Ahmad Molla Mohammad ʿAli Vaʿez Khansari) suggests that he likely hailed from Khansar in Esfahan province (map), an area where the taʿziyeh tradition thrives in the present. One of the earliest eyewitness accounts of a relatively fully-formed taʿziyeh performance is found in the travelogue of German cartographer Carsten Niebuhr and describes an enactment that took place on Kharg Island (map) in 1179/1765 (Niebuhr 1778, vol. 2, p. 199–201).

Today, performances remain a highly important element of devotional culture for the many communities who stage them. Through replaying the events at Karbala, the performers and audiences preserve the memory of the martyrs, seek proximity to them, mourn their suffering, and hope for intercession. Many performances take place in tekiyehs (also called hosayniyehs), spaces designed to house the genre that include a saku (raised central platform) (fig. 1–2). Some of these are historical buildings, such as the those of Baraghan in Alborz province (map) and Deligan in Markazi province (map), while others are modern yet replicate traditional staging conventions. Performances also take place in buildings temporarily repurposed during Moharram, or outdoors (fig. 3). They are often staged in proximity to shrines and in the courtyards of emamzadehs.

The plays are scripted in verse, and the protagonists deliver their lines in song while the antagonists declaim. There is a tradition of female taʿziyeh-khanan (performers) playing in private for women-only audiences, but at the large public performances, where the audiences are mixed, all adult performers are male, and the roles of women are played by veiled men with the appropriate vocal range (fig. 3). If staging conditions permit, the performances often include an equestrian element. These choreographed short scenes are a remnant of the pitched battles that took place during the Safavid period to commemorate the Karbala martyrdoms and that played an important role in the evolution of the taʿziyeh tradition (Deacon 2019). The presence of the horse also allows for the portrayal of Hosayn’s steed Zuljanah returning riderless to camp after his death, a vision that plays heavily in the iconography relating to Karbala (see, for example, this poster in the Victoria and Albert Museum).

Attendance at a taʿziyeh performance is an intense sonic experience, and the taʿziyeh-khanan (performers) are trained in a special range of vocal techniques, some bordering on the operatic. Modern day performances use amplification, and the declamatory style of the antagonists is exaggerated with an echo effect. While singing is usually a cappella, drums and trumpets accompany scenic movements such as battle scenes, journeys, and the arrival of new characters. The voices of the audience—calling in support of the protagonists, for blessings upon them, and audibly weeping at moments of sadness—are an integral part of the soundscape.

In this clip (audio 1), two boy performers playing Moslem’s sons Mohammad and Ebrahim sing together in conversation with a shepherd who has offered them shelter while they evade capture (Moslem b. ʿAqil, Hosayn’s cousin, was sent as a messenger to Kufa and killed there shortly before the battle of Karbala). The drums and trumpet that follow the exchange accompany the arrival of another visitor to the shepherd’s house.

Audio 1. Performance of Shahadat-e do teflan-e Moslem (The Martyrdoms of the Two Children of Moslem), temporary hosayniyeh (repurposed mechanic’s workshop), Khiyaban-e Kargar, Gomrok, Tehran (map). 5 Moharram 1439/26 September 2017. Recording by Lucy Deacon.

Sources:

- Deacon, Lucy E. “Remembering Through Re-Enacting: Revisiting the Emergence of the Iranian Taʿzia Tradition.” Medieval English Theatre 41 (2019): 58–83, [Crossref]

- Deacon, Lucy E. Karbala in the Taʿziyeh Episode: Shiʿi Devotional Drama in Iran. Leiden: De Gruyter Brill, 2024 [in press].

- Fath-Ali Baygi, Davod and Mehdi Daryai. Daftar-e taʿziyeh 13. Tehran: Entesharat-e Namayesh, 1394 Sh/2015.

- Niebuhr, Carsten. Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegenden Ländern, 2 vols. Copenhagen: Nicholaus Möller, 1778.

Citation: Lucy Deacon, “Taʿziyeh-khani.” Catalog entry in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.