*This is an English translation of the original catalog entry in Persian

5Current zarih (screen) of Emamzadeh Yahya and the objects inside

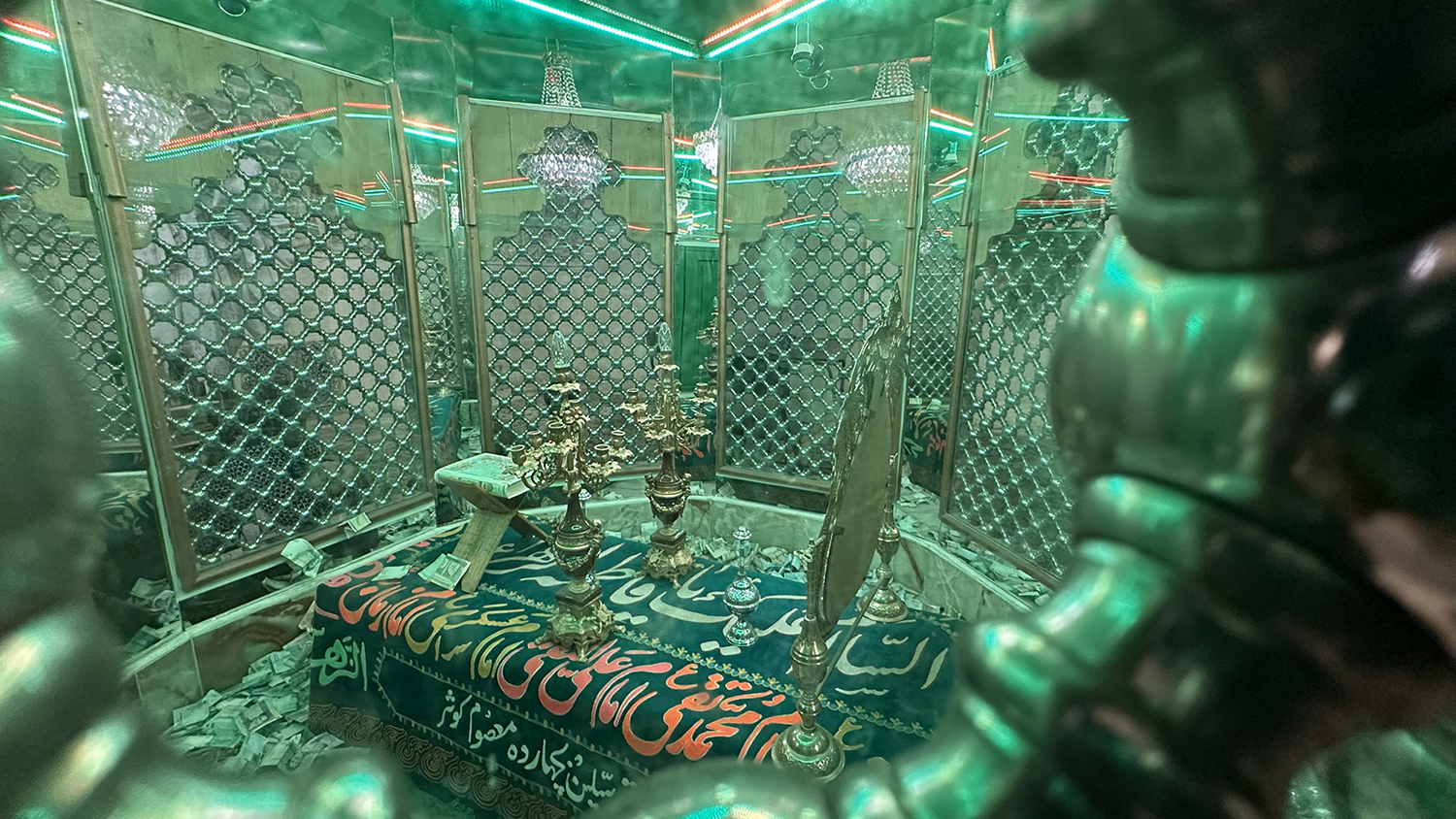

Emamzadeh Yahya, Varamin Zarih: Iran, 1389 Sh/2010–11 Photographs by Hamid Abhari, 2024

A zarih (ضریح, screen) is the focal point of emamzadehs in Iran, and its placement around and over the tomb is a significant sign of its sanctity and blessing. On the one hand, the interior space of the screen protects the cenotaph (سنگ قبر, sang-e qabr), and on the other, it is a kind of tangible expansion of the space around the main tomb (قبر, qabr) of the holy sanctuary (بارگاه مقدس, bargah-e moqaddas). Pilgrims circumambulate the zarih, touching it with their hands and faces, looking through its metal grills, and reciting supplications, thus performing the rituals of pilgrimage (زیارت, ziyarat). The current zarih of Emamzadeh Yahya was prepared and installed by the Owqaf (endowment organization) in 1389 Sh/2010–11 (video 1). This zarih replaced an earlier screen (see History of Evolution).

Video 1. View of the zarih of Emamzadeh Yahya. Video by Hamid Abhari, 2024.

Traditionally, in small and local emamzadehs, gender segregation within the interior of the emamzadeh is not enforced. However, in shrines with larger halls, this gender segregation is established. In the last three decades, there has been a greater emphasis on this segregation in shrines, and when possible, separate entrances are provided for women and men. In the photograph below, we can see the division of the interior of the Emamzadeh Yahya into two sections: the men’s section (on the right) and the women’s section (on the left), from a common entrance (fig. 1).

In addition to its own decoration and screened windows, two groups of objects further sanctify the zarih and in turn the tomb and sanctuary. The first group includes decorations above the zarih such as chandeliers, which emit abundant light downward onto the screen, and natural or artificial flowers in vases, which are symbols of Paradise’s gardens and flowers (fig. 2).

The second group comprises the elements inside the zarih, which signify the focal point of the tomb and are typically inaccessible to the general public. The most important of these sanctified objects is the grave of the Emamzadeh [marked by a cenotaph], around which everything is centered (fig. 3). The cenotaph is covered by a parcham (textile) bearing the Shiʿi sacred names, especially those of the Ahl-e Beyt (اهل بیت, the family of the Prophet Mohammad), and for this reason, people usually do not have a clear view of it. Among the other internal elements are candlesticks, which in recent times have been equipped with electric lamps instead of candles, a copy of the Qurʾan and its stand (رحل, rahl), a mirror (آینه, ayeneh), and a green lamp, symbolizing the sacred lineage of the Emams and the Prophet of Islam. Another element is money, a votive offering (نذر, nazr) that pilgrims throw into the zarih hoping that their wishes come true. The mirror is a multi-dimensional symbol in sacred places. On the one hand, it is a means of multiplying the light and images of sacred objects, and on the other, it is a metaphor for a window to another world. According to some pilgrims, looking into a mirror is an opportunity for the pilgrim to reflect on their faith by seeing their own reflection (see no. 38). However, the mirror inside the zarih of Emamzadeh Yahya primarily signifies the combination of light (from the candlesticks) and the desire to multiply it through reflection.

Traditionally, in Shiʿi pilgrimage culture, touching sacred elements within sacred spaces is a key, and even central, part of the sensory perception of ziyarat and gaining blessings (see Parsapajouh’s essay). For this reason, believers touch the main doors and walls, sometimes the floor of the shrine, and the zarih itself with their hands. They sometimes kiss it or place their face and eyes on it as a sign of respect and reverence. One way of connecting with the zarih is to tie a thread, tasbih (تسبیح, prayer beads), or green ribbon to it, or even to the windows of the emamzadeh or a tree in the courtyard (see no. 23) (fig. 4). In some traditions, a padlock (قفل, qofl) is also used (see no. 39). This tying or locking signifies a major difficulty in the believer’s life and the expectation that the saint or Emamzadeh will solve the problem and untie the knot. It also indicates the pilgrim’s commitment to fulfil the vow if their wish is granted.

A very important point about the objects inside the zarih is that believers cannot touch them during ziyarat. While their presence signifies sanctity, they are not intermediaries during pilgrimage. They are part of the symbolic decoration of the zarih and are also influenced by the financial conditions of the emamzadeh’s custodians. The type and price of the cenotaph, the parcham covering it, the candlesticks, and even the design of the zarih indicate the importance of the emamzadeh and its symbolic and economic power (fig. 5). Entering the zarih to collect votive offerings and clean it is a symbolic act that only individuals with religious influence and a high position in the management of the emamzadeh have the right to perform.

During the month of Moharram, black shawls and banners are used to decorate the interior of the emamzadeh, its entrance, the walls, and even the zarih as a sign of mourning for this month and even as a sign of the Emamzadeh mourning (fig. 6). The only figural image (شمایل, shamayel) that currently exists in the interior of the Emamzadeh Yahya is on a black shawl displayed on the zarih during the mourning period. This portrait is usually attributed to Hazrat-e ʿAbbas, the brother of Emam Hosayn, who played a very important role on the day of Ashura. In Shiʿi beliefs, the Prophet and his daughter Fatemeh and the Twelve Emams are considered infallible and without any sin, and other humans are certainly fallible. From the Shiʿi perspective, among mankind, Hazrat-e ʿAbbas has the highest importance and sacred status. Even in popular religion, the votive offerings dedicated to Hazrat-e ʿAbbas are sometimes more important than all other votive offerings dedicated to other sacred figures.

Sources:

- مظاهری، محسن حسام (ویراستار). فرهنگ سوگ شیعی. اصفهان: نشر آرما، ۱۳۹۵ش. [Mazaheri, ed., Shiʿi Mourning Culture, 2016] [Lib.ir, different edition]

- منتظرالقائم، اصغر، احمد شرفخانی و محمد مهرابی. امامزادگان و حیات فرهنگی: مروری بر نقش فرهنگی امامزادگان. تهران: سازمان اوقاف و امور خیریه سازمان چاپ و انتشارات، ۱۳۹۳ش. [Montazerol Qaem et al., Emamzadehs and Cultural Life: An Overview of the Cultural Role of Emamzadehs, 2014] [Lib.ir]

Citation: Jabbar Rahmani, “Current zarih (screen) of Emamzadeh Yahya and the objects inside,” translated by Hoda Nedaeifar. Catalog entry in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.