23Sacred trees

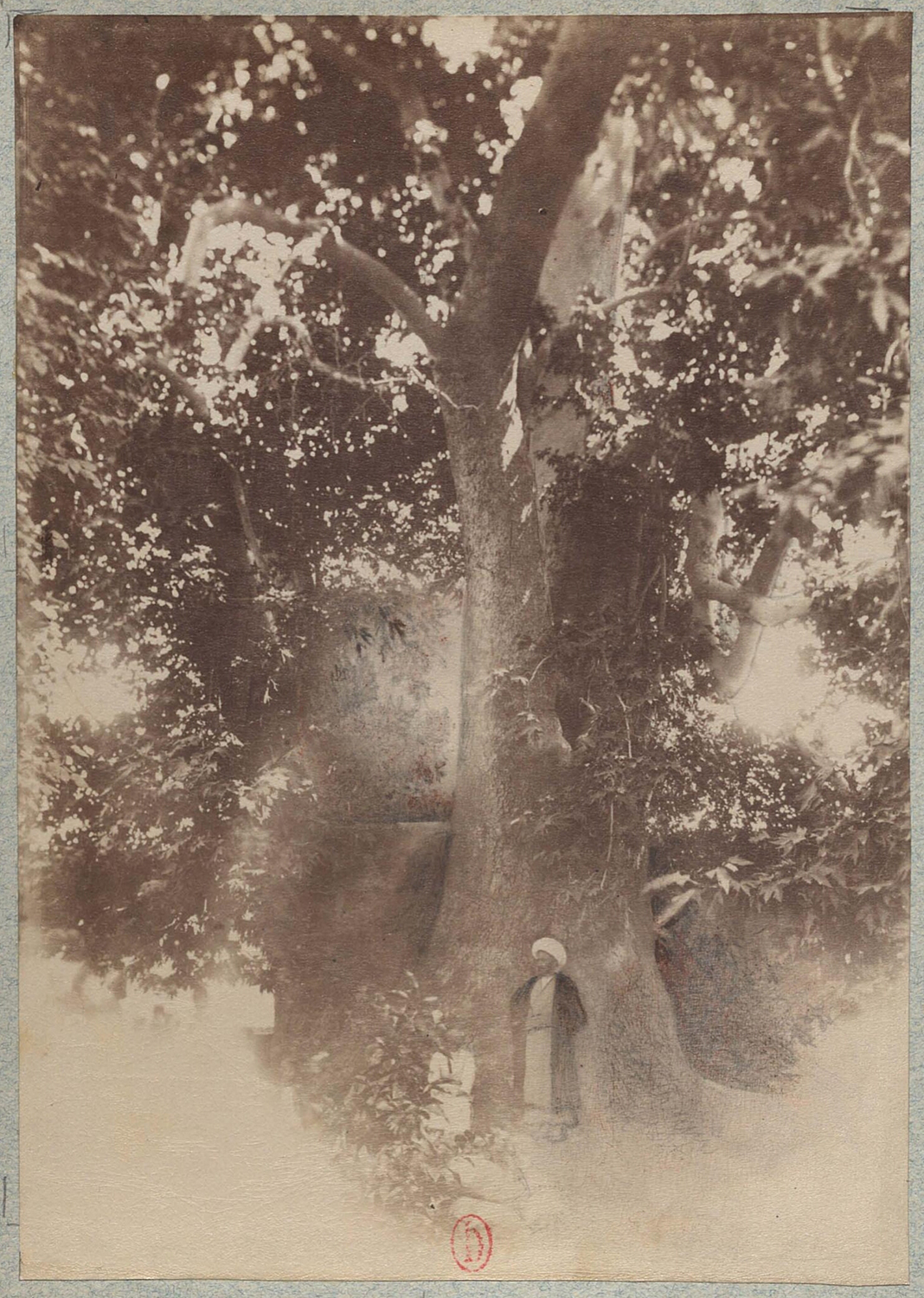

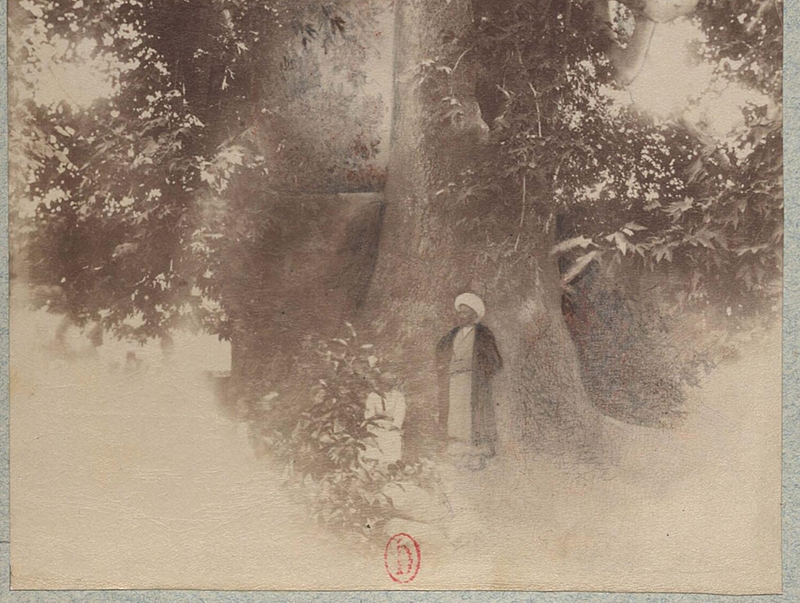

The chenar tree of the Emamzadeh Saleh, Tajrish, Tehran No longer standing Photograph by Jane Dieulafoy, June 1881. Bibliothèque de l’Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art, Paris, 4 Phot 18 (1), no. 135, p. 67.

The sacred atmospheres of some Iranian shrines are closely intertwined with a tree. Some of these trees are sanctified by saints in dreams, and then inspire the construction of a shrine, while others lend a general sacredness through their age. At the Emamzadeh Abdolvafi in Kelarabad in rural coastal Mazandaran (map), a yew tree (sorkhdar) believed to be 800 to 1000 years old stands on the southeast side of the tomb set in a lush forest. Much further south in central Iran, a massive chenar (plane) tree with a root said to be 2,000 years old shades the entrance of the Ilkhanid-period shrine of Shaykh ʿAbdosamad at Natanz (map). This tree was one of several in the area registered as national living heritage (miras-e zendeh) in 2018 (fig. 1).

Video 1. The chenar tree and entrance portal of the Shrine of Shaykh ʿAbdosamad, Natanz. Video by Keelan Overton, 2018.

Some trees in emamzadehs become the focus of the pilgrim’s nazr, or vow. In such cases, ribbons and other materials are tied to the tree, much like the process typically directed toward the zarih in the tomb proper. In some rarer cases, trees can become associated with the tragedy of Ashura (no. 29). The tree next to the Emamzadeh ʿAli Asghar (map) in the village of Zarabad near Alamut (Qazvin province) is known as the ‘bloody tree of Zarabad,’ because it is believed to ooze a red substance during this period of mourning. Ribbons and fabrics of all kinds are tied to it during the village’s male-dominated mourning ceremonies (Mehr, Google Maps). A tree in Karafestan in Amlash district in Gilan (map) apparently ‘mourns’ in the same way (Khakpour 2017, p. 67). In this rural region and others, sacred trees can resonate among women especially and often beyond the confines of normative Twelver Shiʿism. The phenomenon of visiting an auspicious tree to express a wish is by no means unique to Iran and common in many cultures, many of which have an explicit term for ‘wishing tree’ (Gruber).

In this entry and the following one (no. 24), we focus on two famous trees associated with emamzadehs in Tehran: the now lost tree of the Emamzadeh Saleh in the northern neighborhood of Tajrish (map) (figs. 2–3; see this essay) and the still standing example at the Emamzadeh Yahya in the south (map).

The chenar tree of the Emamzadeh Saleh no longer stands but is memorialized in many photographs, texts, and memories. According to a 1394 Sh/2016 newspaper article based on interviews with residents, the tree was said to have been over 1000 years old and contemporary to the tomb of Emamzadeh Saleh, a son of the Seventh Emam Musa al-Kazem (d. 799). The tree was the heart of the neighbourhood and served as a gathering space for refreshment, a playground, the shop of a cobbler, and an extended prayer space (fig. 3). The tree caught fire in 1336 Sh/1958, was reduced to the trunk, and eventually uprooted despite local protests. According to one resident, “The name of the chenar tree of Emamzadeh Yahya is still fresh (lit. green) in the memory of the people of Shemiranat.”

In June 1881, just before departing for Varamin, Jane Dieulafoy photographed the Tajrish tree (main image, fig. 4). A mullah stands at the base of the tree while a seated man gazes up at him. In La Perse, where this photograph was highly doctored up as a woodcut, Dieulafoy paints the scene:

One of these trees, included in the grounds of the Tadjrich [Tajrish] mosque, is known throughout Persia as tchanarè Tadjrich (platane de Tadjrich) [chenar or plane tree of Tajrish]. Figures cannot give an idea of its extraordinary size, and especially of the development of its trunk, which measures fifteen meters in circumference. Unfortunately, its height is impossible to estimate: the branches, as big as huge trees, extend over buildings high enough to hide them. The Tadjrich tree is in fact the real mosque; the faithful pray under its shade, the mollahs gather the children there for instruction, and the merchants of tea and fresh water find a place to set up their cups, samovars, and jugs between its large roots.

It remains to be seen if the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin has ever been associated with a sacred tree, but we can say that the site’s natural setting has shaped its identity in both the past and the present. Today, the trees in the east side of the courtyard provide shade for funerals, and on some days, the sounds of chirping birds fill the courtyard.

Sources:

- Alam, Hoshang. “Derakt.” Encyclopædia Iranica, December 15, 1994 (last updated November 22, 2011), https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/derakt.

- Dieulafoy, Jane. La Perse, la Chaldée et la Susiane: relation de voyage contenant 336 gravures sur bois d’après les photographies de l’auteur et deux cortes. Paris: Librairie Hachette et Cie, 1887. [Internet Archive]

- Gruber, Christiane. “Back to Nature: The Votive in Islamic Visual and Material Cultures.” Material Religion 13, 1 (2017): 99–101. [Taylor & Francis]

- Hamshahri. “Dāstān-e derakht-e Emāmzādeh Sāleh (AS) Tajrīsh: Chenāri keh dar yādhā sabz ast” (The Story of the tree of the Emamzadeh Saleh (AS) of Tajrish: A Chenar that is fresh in memory). 1 Bahman 1394/21 January 2016. [Hamshahri]

- Khakpour, Minoo. “Aghadar, a belief of revering trees in Gilan.” Arts and Humanities Open Access Journal 1, 2 (2017): 63–70.

- Mehr News. “Derakht-e khūnbār-e Zarābād dar ʿĀshūrā sūgvār ast” (The bloody tree of Zarabad mourns on Ashura). 8 Mehr 1396/30 September 2017. [Mehr News]

Citation: Keelan Overton, “Sacred trees.” Catalog entry in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.