Chronological Overview of the Emamzadeh Yahya Complex, ca. 1200–2024

Keelan Overton and Hossein Nakhaei

Contents:

- The Medieval Complex Through Nineteenth-Century Frames

- Dated Ilkhanid-period Architectural Elements in the Domed Tomb, 1262–1349

- Stuccowork and Plastered Brickwork: The Most Extensive and Well-Preserved Features

- Conclusions about the Domed Tomb: Irreparable Damage and Unresolved Historical Evolution

- Safavid-period Features and Resonance, ca. 1500s–1600s

- Qajar-period Historiography and Consumption, ca. 1860–1910

- A Period of Uncertainties and Mysteries, ca. 1897–1923

- New Configuration and Registration as National Heritage, 1930s

- Comprehensive Restoration, Refurbishment, and Urban Renewal: early 1980s to the present

The Emamzadeh Yahya is a shrine complex located in the Kohneh Gel neighborhood of southeast Varamin (map). In the middle of the rectangular courtyard is a domed tomb (gonbad-khaneh) marking the burial place of Yahya b. ʿAli b. ʿAbd al-Rahman (d. 255–56/869–70), a sixth-generation descendant of Emam Hasan (d. 50/670), the second Shiʿi Emam.1 Yahya is believed to have been martyred at the order of ʿAbdollah b. ʿAziz, the Taherid governor of Rey.2 There is a discrepancy among tenth- and eleventh-century sources regarding the precise location of Yahya’s assassination, but the majority agree that it occurred in a village in the Rey region (see Khamehyar’s essay in Persian and English translation).

The field of art history has tended to focus on the Emamzadeh Yahya’s identity and history during the Ilkhanid period (1256–1353), devoting particular attention to its luster (zarrinfam) tilework.3 In this essay, we approach the shrine as a dynamic, living complex whose history spans over seven hundred years. Using all currently known accessible sources, including displaced luster tiles, inscriptions by pilgrims, tombstones, visitor accounts, restoration reports, and the site itself, we trace the shrine’s many layers of use, transformation, preservation, and resonance. In doing so, we acknowledge the Emamzadeh Yahya’s simultaneous identities as a sacred tomb, destination for ziyarat (pious visitation), cemetery, historical monument, cultural heritage site, tourist destination, and the main community center and heart of the Kohneh Gel neighborhood.

Note on content and terminology: This essay attempts to summarize seven centuries of history in about 10,000 words and is accordingly brief and schematic in some areas. In many cases, we refer readers to other features in the exhibition, including the Photo Timeline with 55 images of the Emamzadeh Yahya and the filmed Site Tour, which provides a spatial sense of the complex and Kohneh Gel neighborhood, previously a village. Throughout this essay, we use the terms ‘reconfiguration’ and ‘alteration’ to refer to the significant physical transformation of the site at the end of the Qajar period. We do not employ the term ‘renovation,’ because we doubt that this was a conventional act of neutral preservation. We use the term ‘restoration’ to refer to the site’s upkeep and preservation over time, which ranged from the relatively ad hoc (for example, light cleaning by caretakers) to the comprehensive and professional (for example, the major multi-year restoration in the early 1980s). Some efforts, including recent focused work on the stucco inscription, might also be described in English as ‘conservation.’

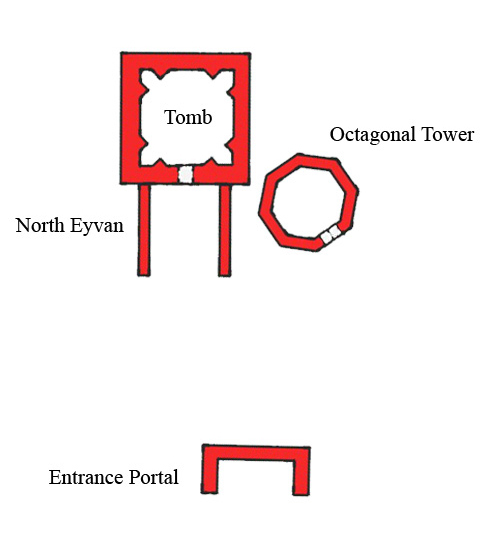

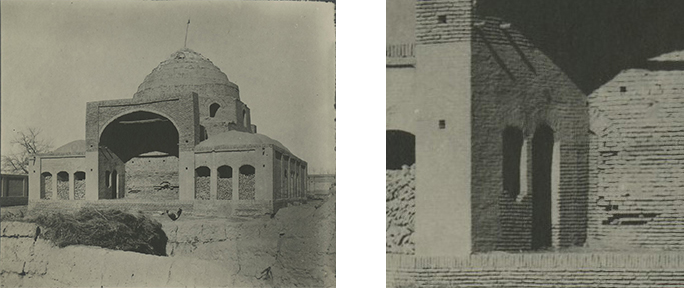

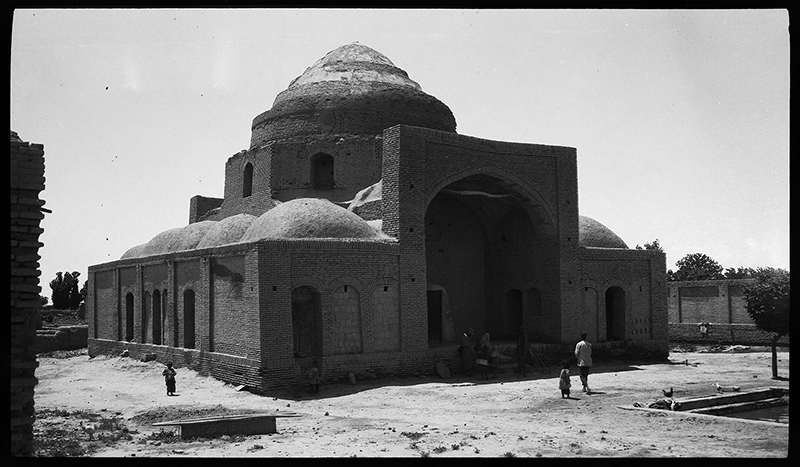

The Medieval Complex Through Nineteenth-Century Frames

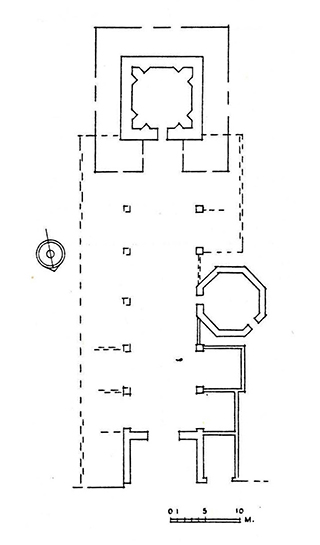

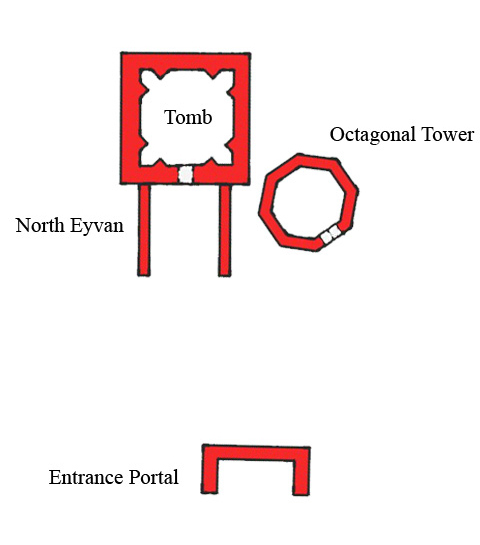

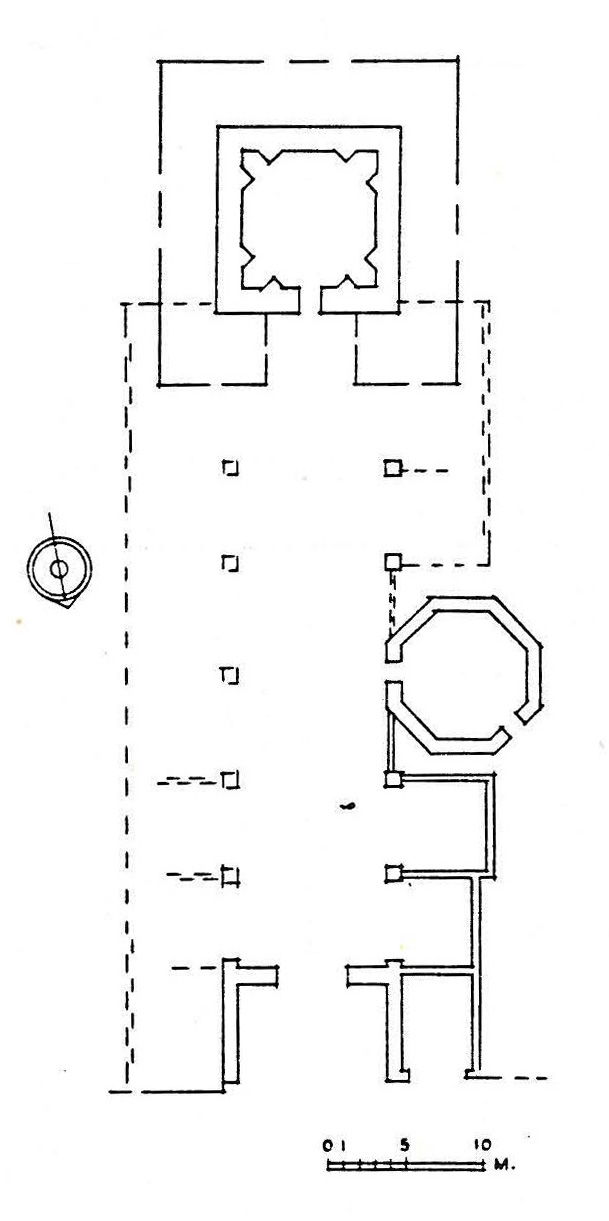

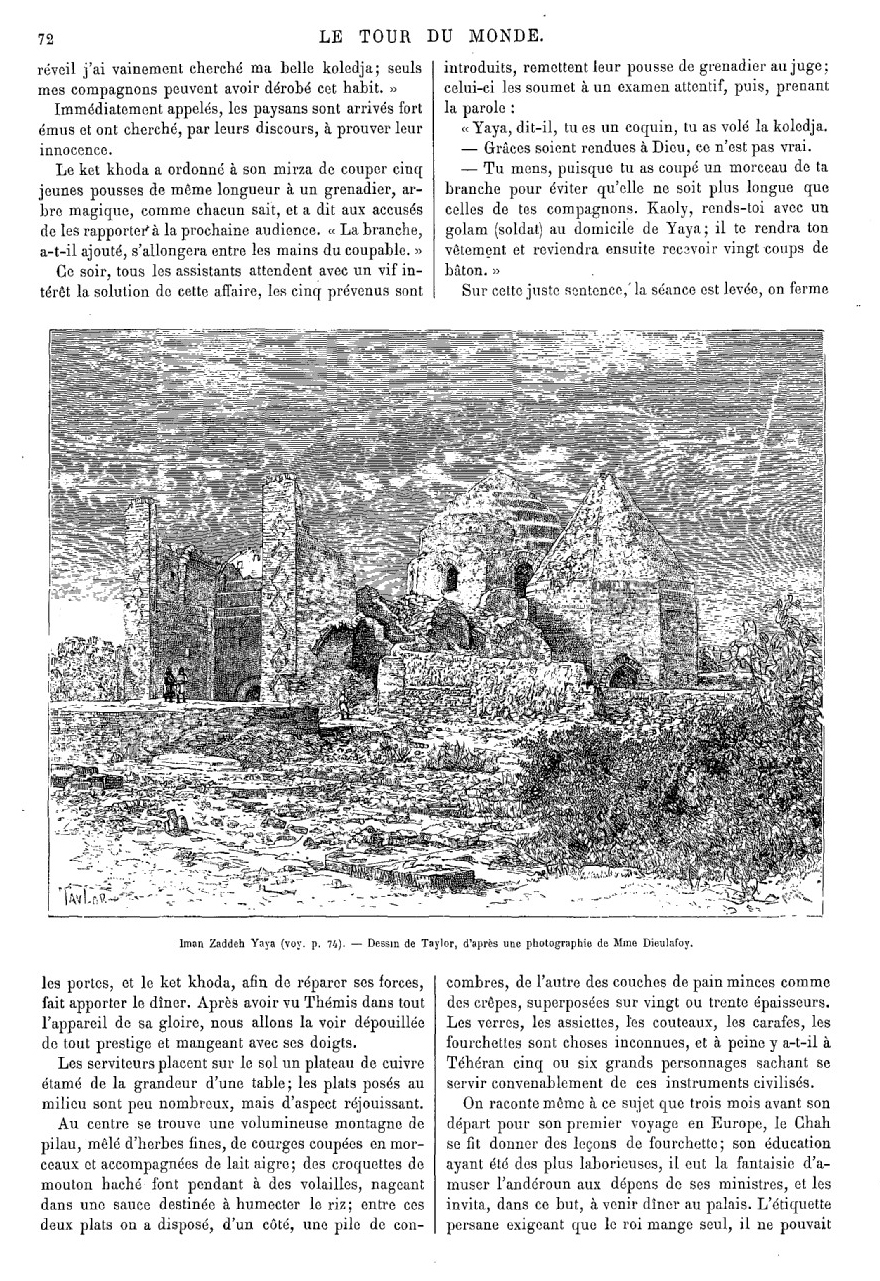

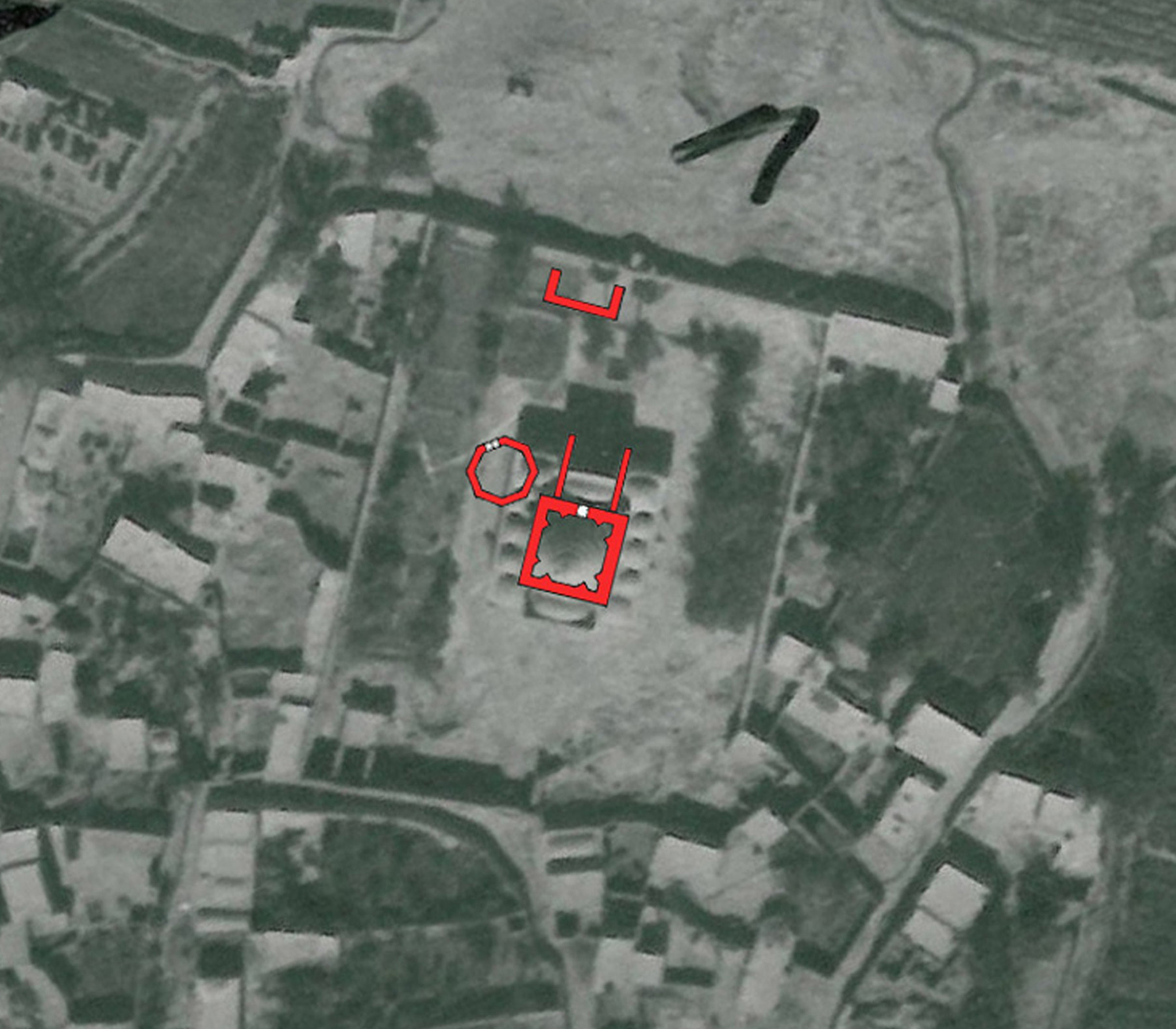

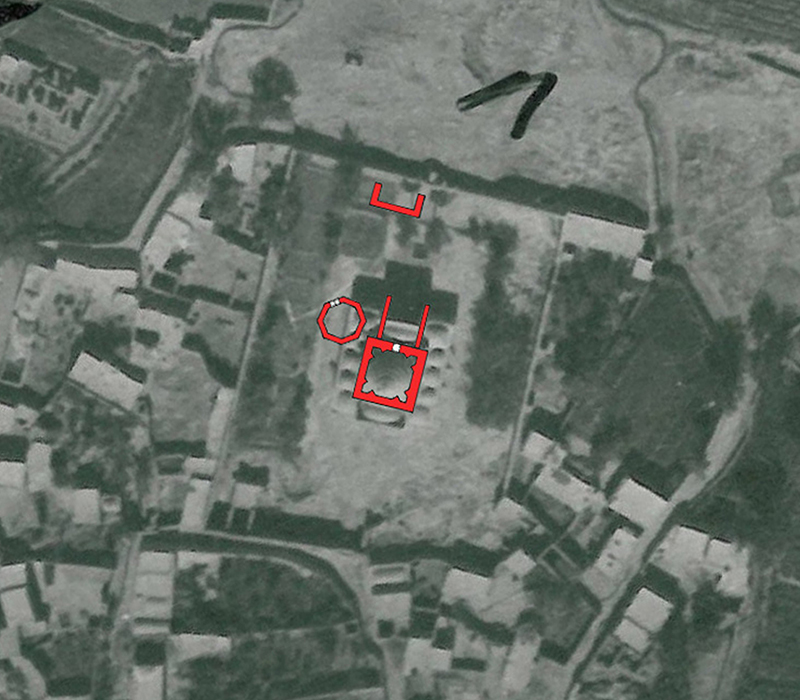

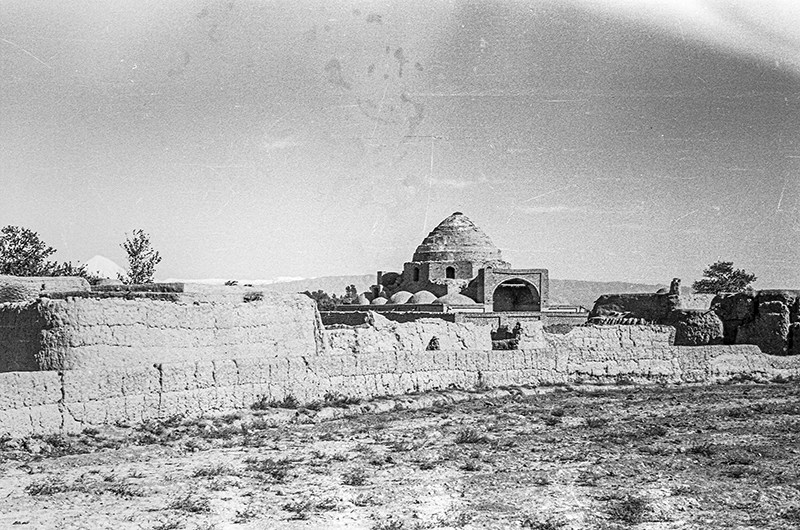

The Emamzadeh Yahya complex that stands today reflects a major reconfiguration that transpired at the end of the Qajar period (1789–1925), likely around the turn of the twentieth century. In order to peel back the layers of the medieval monument, we must turn to nineteenth-century texts and photographs. The best source for the shrine’s presumably Ilkhanid-period plan is a 1881 photograph by French traveler, author, and amateur archaeologist Jane Dieulafoy (d. 1916) (fig. 1). The complex included a pishtaq (monumental entrance portal) on the north, an octagonal tower capped by a conical roof on the west, and the main tomb (gonbad-khaneh) at the south (rear), with a stepped dome fronted by a long eyvan. There were also some unidentifiable small spaces and rooms between the entrance and tomb. At the time of Dieulafoy’s visit, parts of a low perimeter wall were still standing.

In her January 1883 article in the Le tour du monde and subsequent 1887 travelogue La Perse, Dieulafoy describes the Emamzadeh Yahya as built in three different eras.4 According to her, “La mosquée est seljoucide et date du douzième siècle, mais elle comprend dans son ensemble un petit pavillon très ancien à toit pointu…remonte sans doute au temps de Guiznevides” (The mosque is Seljuk [ca. 1040–1157] and dates to the twelfth century, but it includes in its ensemble a very old little pavilion with a pointed roof…probably dating to the Ghaznavid period [976–1186]).5 It is unclear what she means by ‘the mosque,’ but this term was often used interchangeably with emamzadeh, likely due to the presence of mihrabs in these tombs.6 The second part of Dieulafoy’s description refers to the now lost tower with a conical dome on the west.

Dieulafoy also mentions the tomb’s tilework: “Toutes les faïences à reflets métalliques du mihrab, du lambris et du tombeau ont été posées bien après la construction due deuxième imamzaddè, et l’on a dû, afin de les placer, détruire une partie de la décoration primitive” (All of the luster tiles of the mihrab, the walls and the ‘tombeau’ [in reference to the cenotaph] were installed well after the construction of the second emamzadeh, and part of the original decoration had to be destroyed to install them).7 Today, we must read Dieulafoy’s account with a grain of salt, but the possibility of expansion over time, multiple tombs, and shifting functions is consistent with many other Iranian shrines. It also accords with genealogical sources focused on the descendants of Emams, a genre known as kotob-e ansab, which confirm the existence of Yahya b. ʿAli’s tomb or mashhad (place of martyrdom) in Varamin between the tenth and twelfth centuries, hence predating the Ilkhanid period (see Khamehyar’s essay).

While aspects of Dieulafoy’s text remain ambiguous, her photograph allows us to revise the plan of the complex that American art historian Donald Wilber (d. 1997) published in 1955 based on his visit in May 1939 and Dieulafoy’s published woodcut (jump ahead to fig. 31) (fig. 3).8 Using Dieulafoy’s photograph and the one taken from the opposite angle by German art historian Friedrich Sarre (d. 1945) in 1897 (fig. 2), we can propose a more compact plan with the main tomb and conical tower closely positioned (fig. 4).9 Nakhaei’s detailed analysis and drawings are forthcoming in Digital Tools.

Dated Ilkhanid-period Architectural Elements in the Domed Tomb, 1262–1349

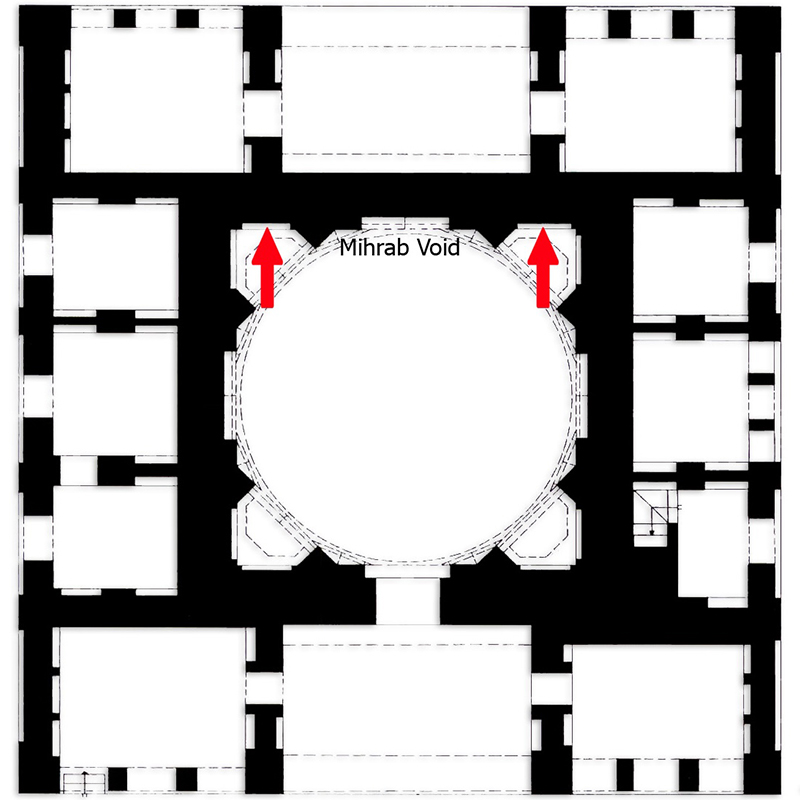

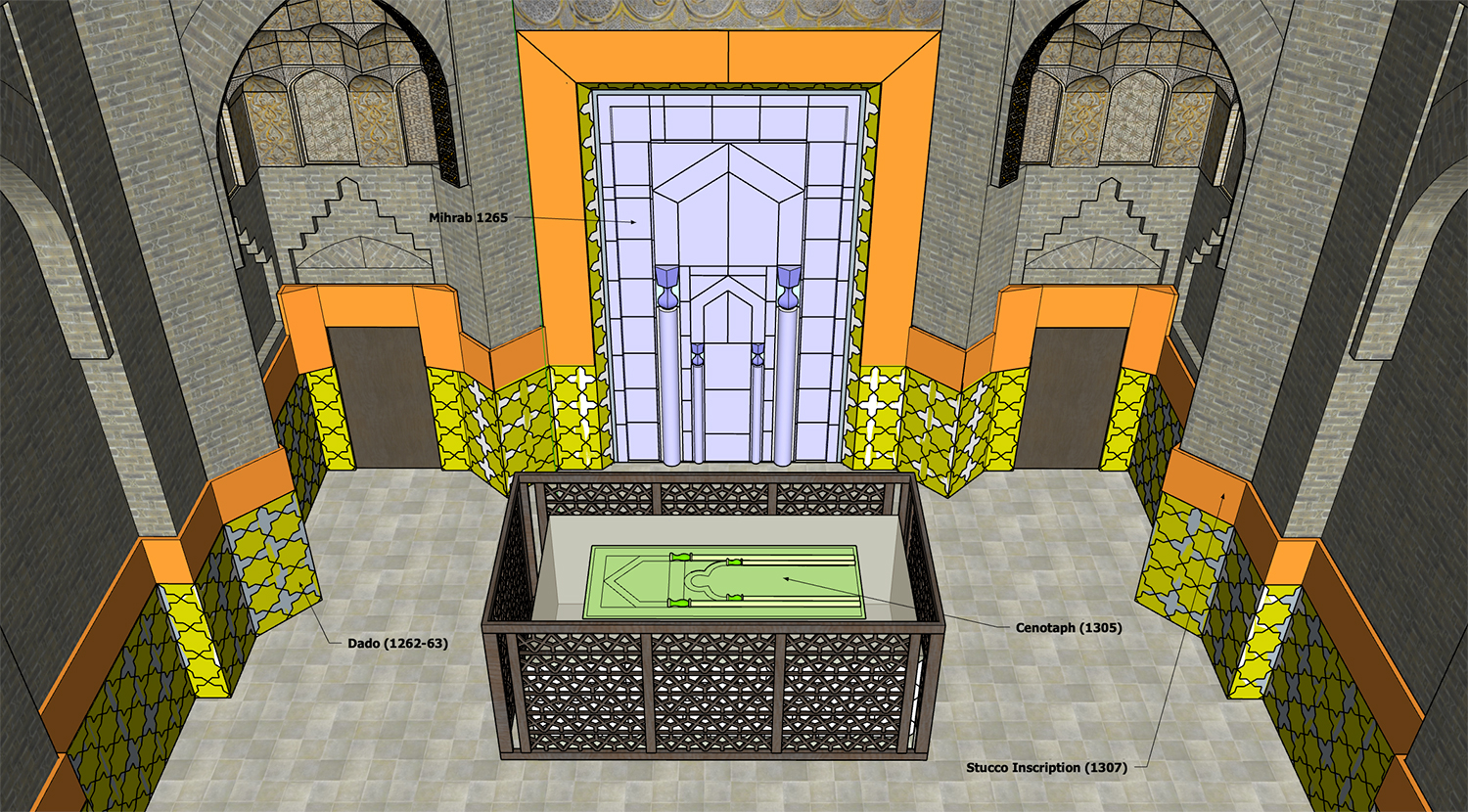

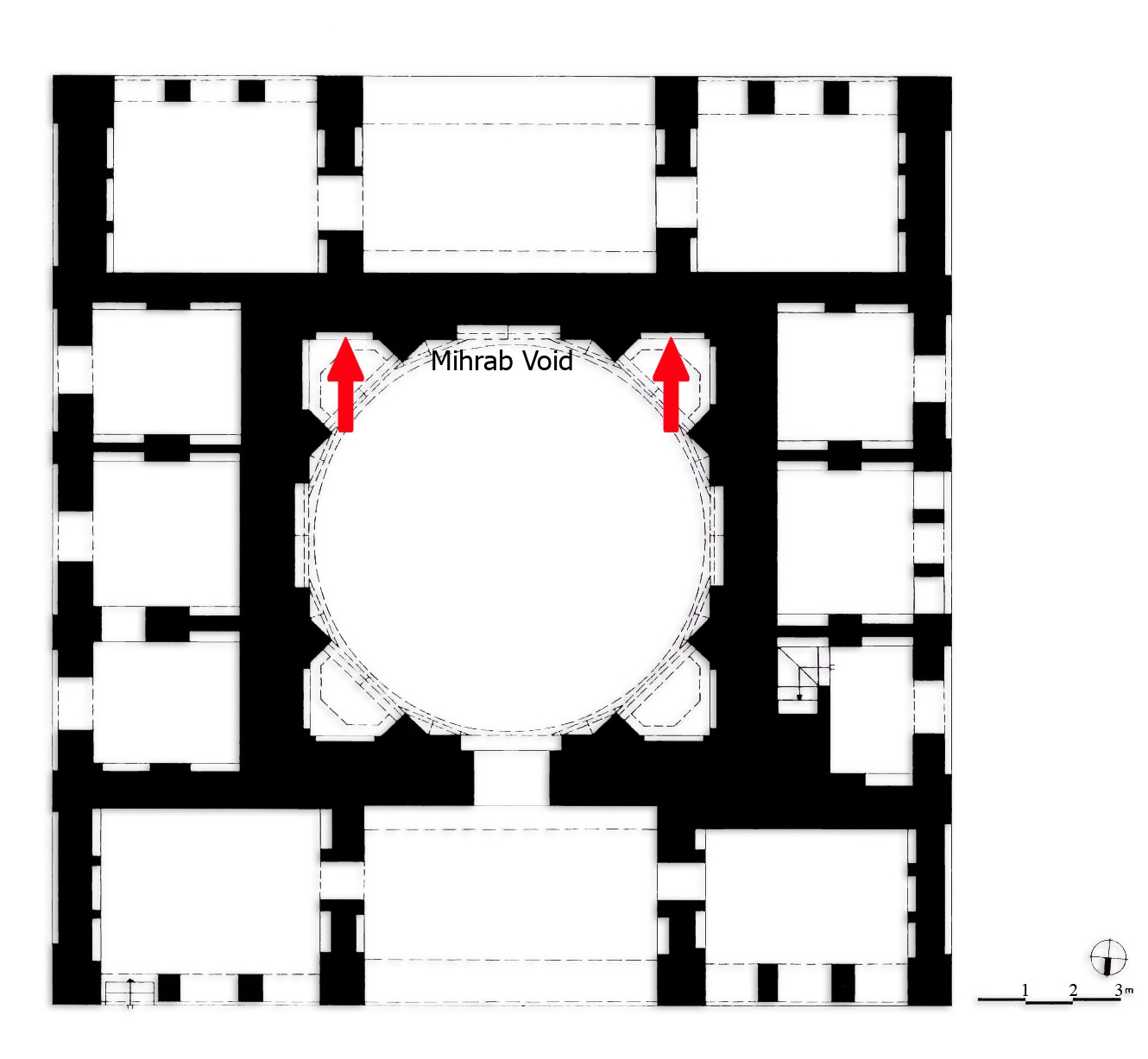

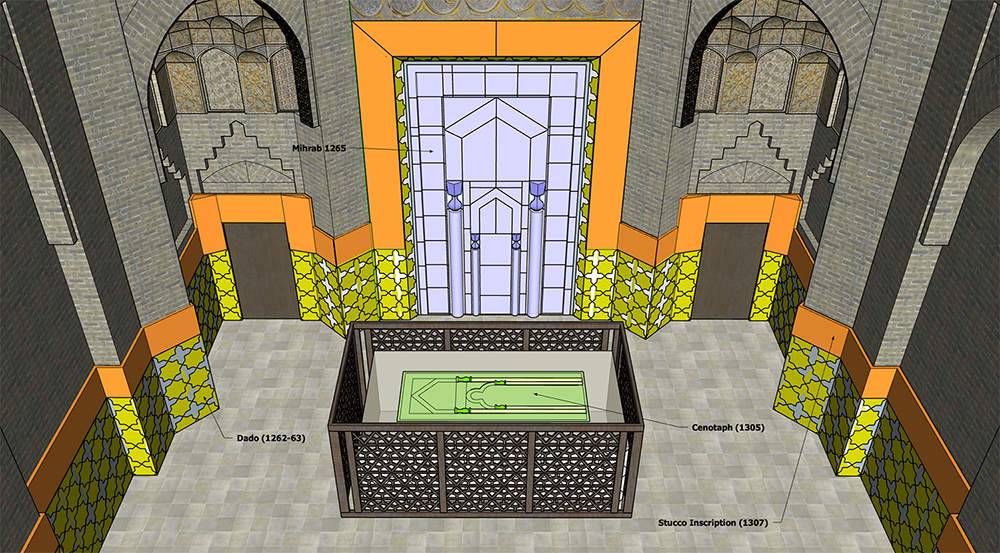

The best sources for documenting the Ilkhanid-period architectural patronage of the Emamzadeh Yahya are four sets of dated inscriptions in the domed tomb (gonbad-khaneh), an octagonal interior measuring 27.5 feet across (vid. 1, figs. 5–6).10 These inscriptions are dated between 660/1262 and 707/1307 and suggest that the site was likely patronized over at least five decades. Only one remains in situ: the stucco inscription wrapping around the entire space. The rest—all luster tiles—were removed, leaving only their vacant locations or imprints as evidence of their prior existence.

Video 1. Interior of the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya from the mihrab wall (south) to the entrance (north), standing on the east side. Video by Hamid Abhari, October 2024.

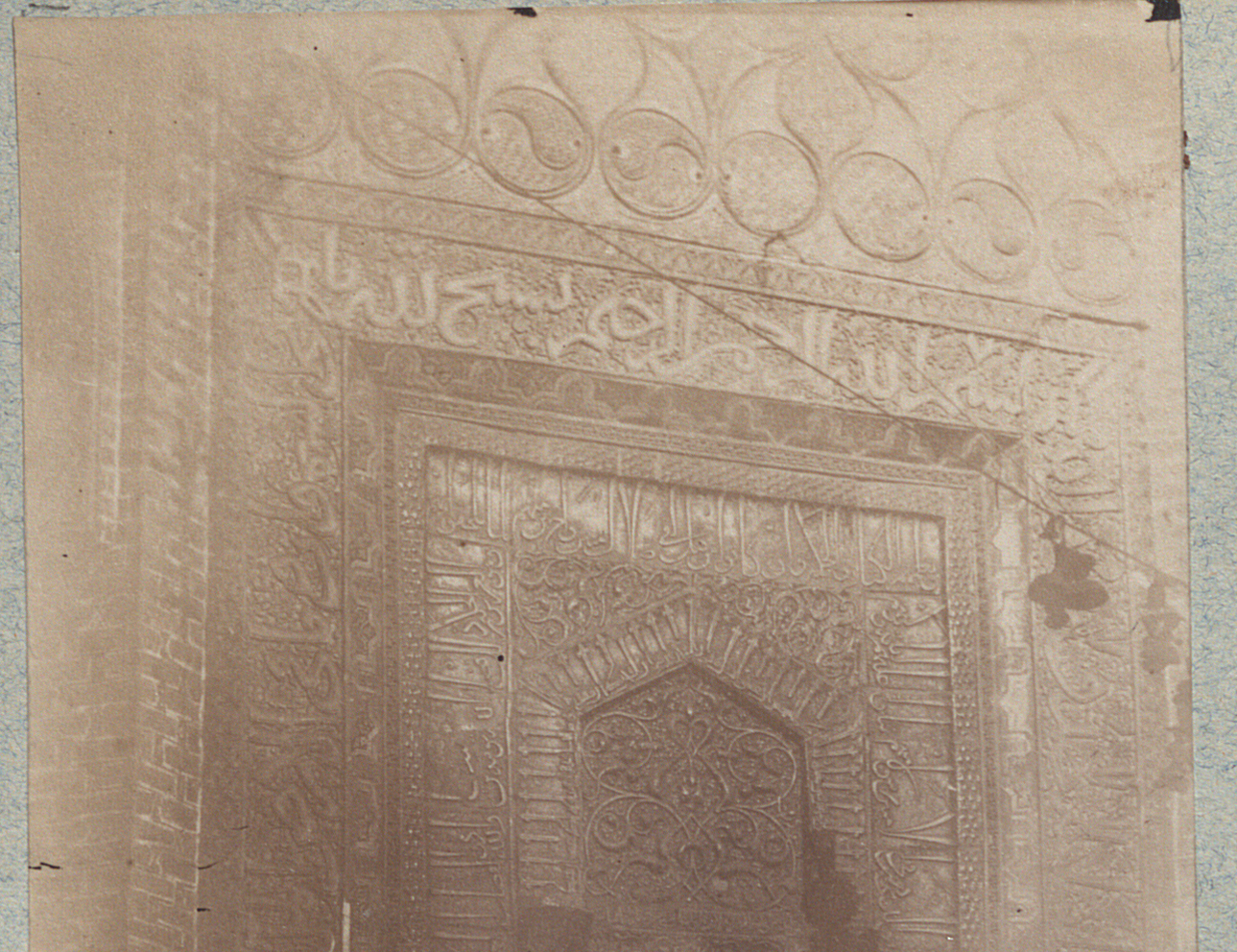

The earliest dated inscriptions appear on the luster star and cross tiles measuring 30–31.5 centimeters (11.8–12.4 in.) that once clad the lower walls of the tomb (dado) and also framed the mihrab in half versions (fig. 7). These tiles carry Qur’anic verses sometimes dated between Dhu al-Hijja 660/October 1262 and Rabiʿ II 661/March 1263, hence just at the beginning of the Ilkhanid period.

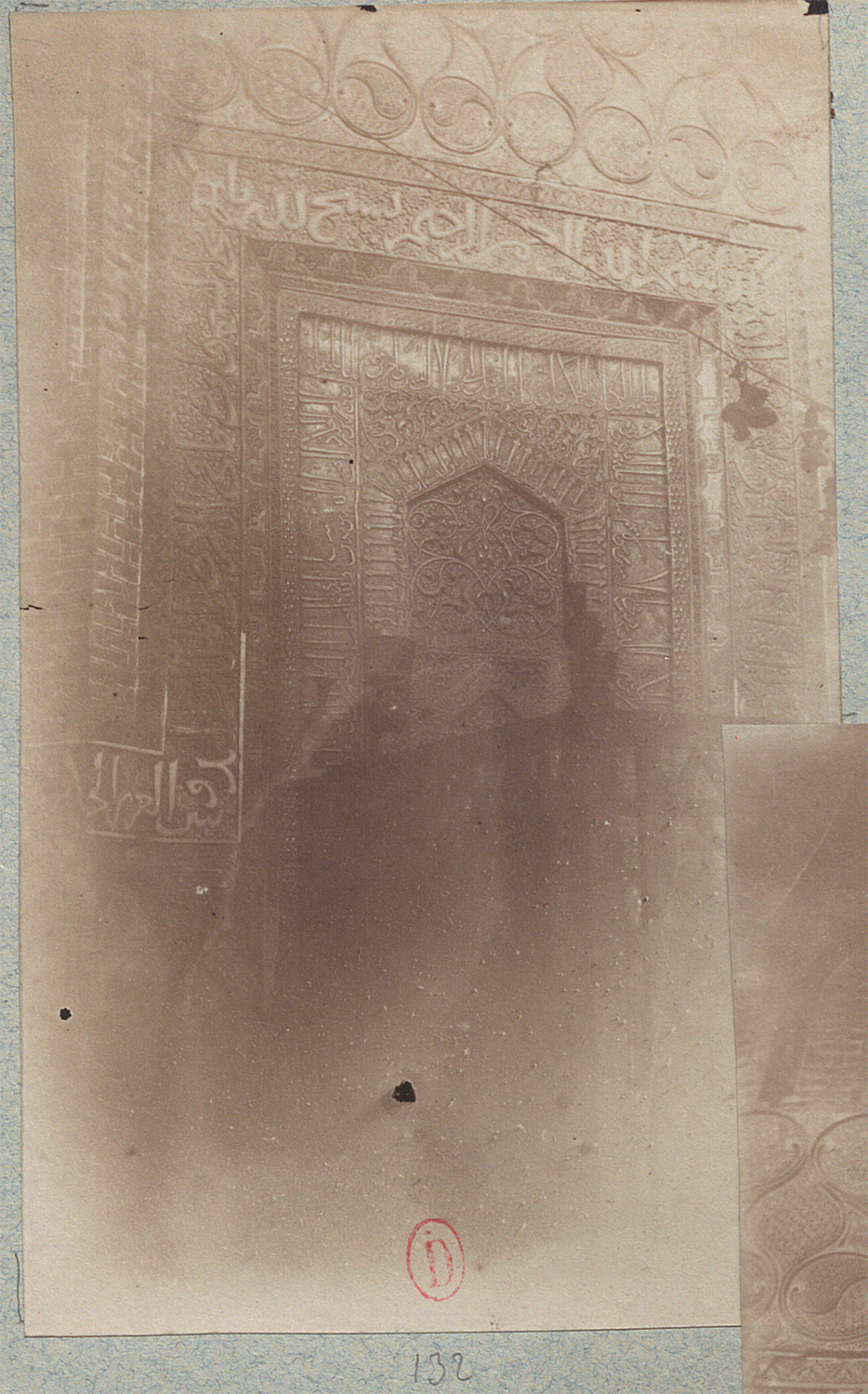

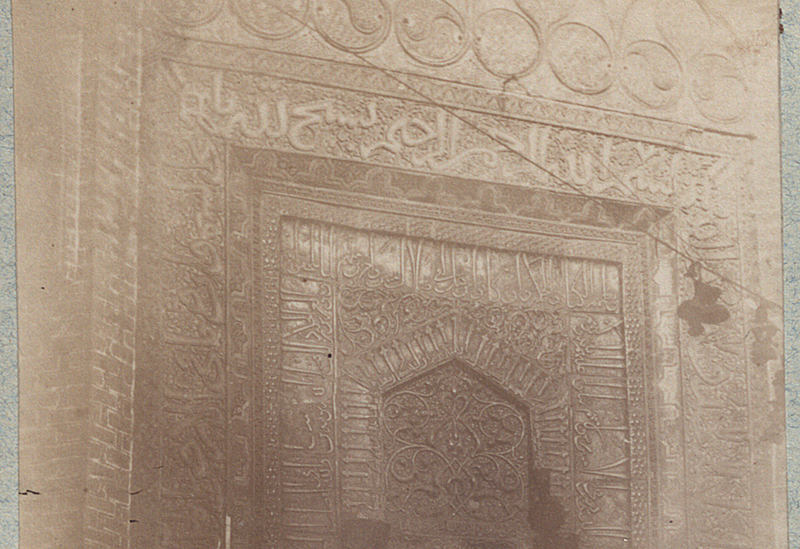

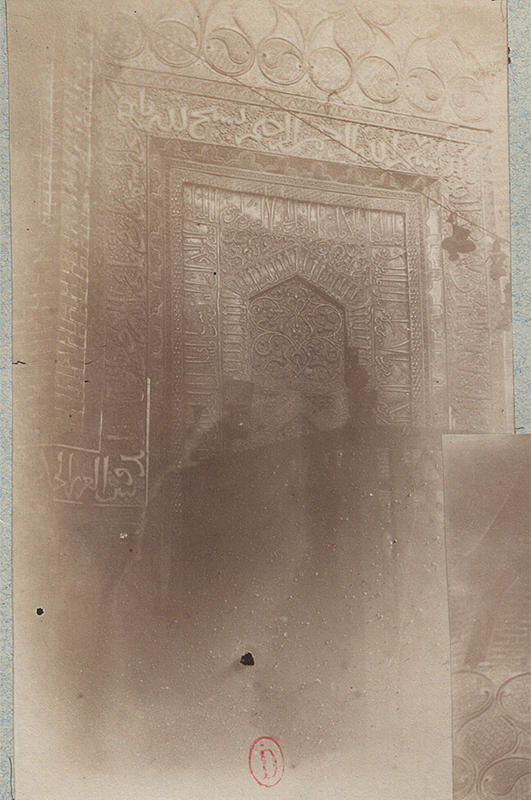

Likely all of these tiles were incrementally stolen from the tomb between circa 1860–1900. Fortunately, select zones of imprints (the shapes created when the tiles were adhered to the wall) confirm their exact placement in some areas (figs. 8–9). In the case of the border framing the mihrab, we have the added benefit of seeing the tiles in situ, thanks to a second important photograph taken by Dieulafoy (figs. 10–11).

Several ambiguities surround these star and cross tiles. While they are routinely described as bearing Qur’anic verses, some examples attributed to the tomb are inscribed with Persian poetry (Checklist, no. 19), suggesting a possible mix of languages and texts on the wall.11 The question of attribution is itself a major one, and we must leave open the possibility that some tiles attributed to the tomb could originate from other sites with similarly sized tiles. Nineteenth-century acquisition records tend to describe these tiles vaguely as ‘Varamin-type’ or ‘from Varamin,’ which complicates matters (no. 19 and Handling Session). Finally, while the tiles are assumed to have been made in Kashan, they are not signed, and we cannot be sure where they were produced.12

The second Ilkhanid-period dated inscription is found at the base of the approximately seventy-tiled mihrab now in the Shangri La Museum of Islamic Art, Culture, & Design in Honolulu (vids. 2–3) (see Mihrab: Essay). It reads:

العمل هذا المحراب و کتبه علی بن محمد بن ابیطاهر تحریرا فی شعبان المعظم سنه ۶۶۳

The work of this mihrab and ʿAlī b. Muḥammad b. Abī Ṭāhir wrote it; composed in Shaʿbān the Great of the year 663 [May–June 1265].13

Video 2. Panning up the luster mihrab of the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya. The panel with the date and signature is at the bottom center of the mihrab. Shangri La Museum of Islamic Art, Culture, & Design, Honolulu, 48.327. Video by Aiden Khazeni, September 2023.

Video 3. Panning over the luster mihrab of the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya. Shangri La Museum of Islamic Art, Culture, & Design, Honolulu, 48.327. Video by Aiden Khazeni, September 2023.

The third dated inscription appears on a panel presumed to have been part of Emamzadeh Yahya’s cenotaph. Cenotaphs are conventionally empty boxes used to mark the grave (see Cenotaphs), and in tombs, they symbolize the presence of the saint and are the focus of ziyarat. The cenotaph of Emamzadeh Yahya was unfortunately broken up, but it would have been a very large rectangular box (9.84 by 5.41 ft) with all four sides probably covered in tilework.

A four-tiled panel dated 10 Moharram 705/2 August 1305 is presumed to have sat on the top of Emamzadeh Yahya’s cenotaph, because it reads: هذا القبر امام العالم یحیی صل الله علیه (This is the grave [qabr] of the knowledgeable Emam Yahya, may God bless him) (fig. 12). The inscription does not include the saint’s genealogy, however, and we do not have any photographs of the cenotaph in situ. As such, this tombstone’s (لوح مزار) association with the Yahya b. ʿAli in question, and hence the Emamzadeh Yahya complex, remains somewhat tenuous.14 Evidence in favor of this attribution includes the fact that the panel was purchased by the Stieglitz Central School of Technical Drawing in St. Petersburg in Paris in 1913 with hundreds of stars and crosses attributed to the tomb (Checklist, no. 19). The panel is signed by Yusof b. ʿAli b. Mohammad Abi Tahir, the son of the potter who signed the mihrab, and ʿAli b. Ahmad b. ʿAli al-Hosayni (for more on these potters, see Blair’s essay). It is now in the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.

The fourth dated inscription is the only one in situ: the stucco inscription wrapping around the entire tomb and containing three texts: the first four verses of sura al-Jumuʿah (Qur’an 62), the foundation inscription naming the patron Fakhr al-Din Hasan (Fakhroddin, d. 1308) and dated Moharram 707/July 1307, and a hadith (fig. 13) (for a diagram of their placement, see Stucco Inscription, fig. 3). Fakhroddin Hasan was the local ruler (malek) of the province of Rey and Varamin and a member of the powerful Shiʿi Hosayni Varamini family, descendants of Emam Hosayn who had lived in the region for at least three centuries (see Nakhaei’s essay). Fakhroddin probably also patronized the city’s tower of ʿAlaoddin, the burial place of his father ʿAla al-Din Morteza (ʿAlaoddin Mortaza). A Kufic band in glazed turquoise at the top of this tower names the deceased and provides his date of death (4 Safar 675/18 July 1276) and the tower’s completion (688/1289–90) (Architectural Heritage).15 These dates fall between those of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab (663/1265) and the stucco band naming Fakhroddin (707/1307). We will return to the interpretation of these dates shortly.

A fifth Ilkhanid-period inscription warrants mention but, unlike those above, pertains not to the tomb’s architectural decoration but rather its function as a destination for ziyarat. Scattered throughout the large letters of the stucco inscription are minute inscriptions written by pilgrims. These yadegari (inscriptions memorializing visitation) are common in Iranian tombs and sites of all kinds and memorialize visitation by ordinary people. In her essay here (in Persian and English translation), Nazanin Shahidi Marnani documents seventeen readable yadegari on the stucco inscription. Seven are dated, and the earliest example is dated 750/1349 or possibly 730/1329, hence a few decades after the presumed completion of the stucco inscription (Shahidi Marnani, no. 3) (fig. 14).

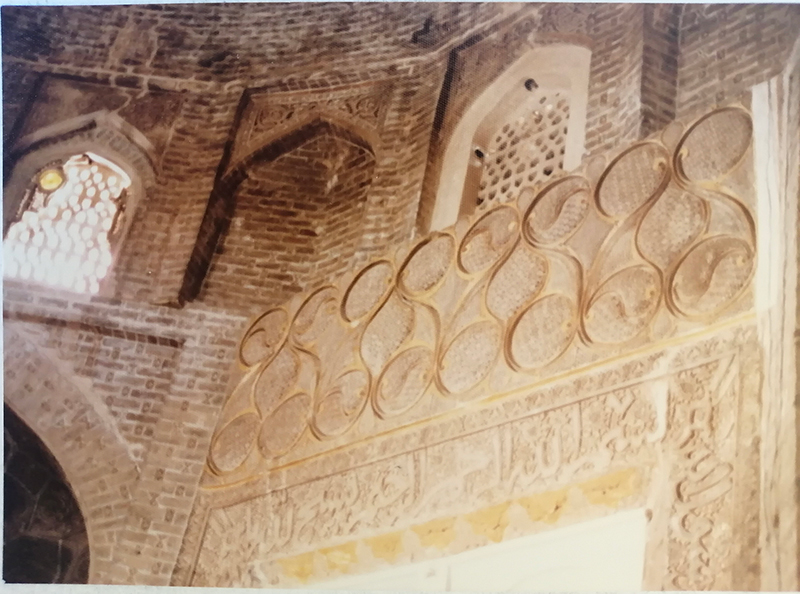

Stuccowork and Plastered Brickwork: The Most Extensive and Well-Preserved Features

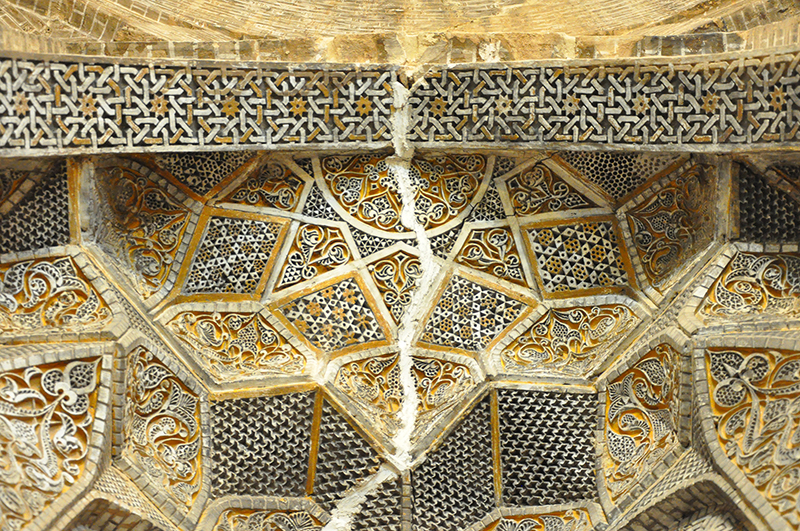

The tomb’s stuccowork is as important and significant as its luster tilework and remains in situ, largely because it was not possible to remove it. It is visible throughout the tomb and includes the 707/1307 epigraphic band, the elaborate squinches in the four corners (fig. 15), a large decorative panel above the mihrab (fig. 16), the sixteen spandrels in the zone of transition, and small epigraphic roundels throughout the dome (fig. 17).16 Although smoke and soot from candles and oil lamps appear to have gradually darkened many of the stucco surfaces, traces of pigment are still visible in some of the squinches, the panel above the mihrab, the spandrels in the zone of transition, and the roundels in the dome. These colors, which likely once covered larger surfaces, would have significantly enhanced the visual impact of the space.

The eight windows in the zone of transition would have also cast dynamic plays of color and light throughout the space (vid. 4, fig. 18). They included an internal stucco trellis inset with round pieces of colored glass and an external screen composed of a denser geometric pattern.17 While the latter remain intact, the stucco trellises are mostly lost, but archival photographs allow us to reappreciate some of their original colored glass (jump ahead to fig. 47). Before reaching these double-layered windows, light would have filtered through the deep outer arches of the zone of transition (fig. 19).

Video 4. View from the zarih up to the apex of the dome. Video by Hamid Abhari, October 2024.

Video 5. View of the dome and courtyard while standing on the roof of the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya. Video by Maryam Rafeienezhad, 2024.

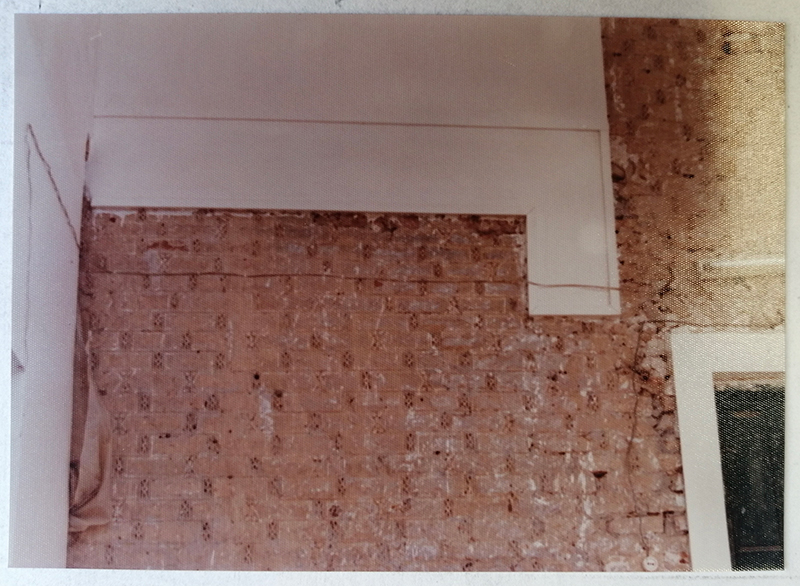

The tomb’s stuccowork must be considered in relation to its original walls, which are in good condition and fortunately have not been covered in new ayeneh-kari (mirrorwork) or paint, as is the case in some nearby emamzadehs (see City Tour). Composed of fired bricks, these walls were covered in a thin layer of plaster, stucco plugs were then carved out of this plaster, and white outlines were added to imitate the pattern of bricks (figs. 20–21).18

In the southeast and southwest corners of the tomb, the stucco inscription band was placed over previous openings (figs. 22–23). The curved upper arches of these previous openings are just visible above the stucco inscription, indicating that it lowered the openings. A photograph of this wall from the exterior shows how these arched openings were at some point blocked up (fig. 24).

Conclusions about the Domed Tomb: Irreparable Damage and Unresolved Historical Evolution

Many questions surround the construction and internal decoration of the gonbad-khaneh. Below is a synthesis of what is known and unknown based on the state of the site as it survives today. While separating a building’s structure and decoration can be problematic, we do so here to make the material digestible and because aspects of their relationship remain unclear.

What we know about the structure:

- It had three openings: two on the south (qibla) wall (each approximately 90 cm/35.4 in. wide) and one wider (almost 145 cm/57 in. wide) on the north wall, directly facing the south wall. The latter still functions as the main entrance of the tomb.

- The two southern openings were filled with bricks, blocked, and no longer function (see fig. 22).

Outstanding questions:

- When was the structure built? Was it built before the Ilkhanid period and then decorated during that time, or was it both constructed and decorated during the Ilkhanid period?

- How did the tomb relate to other buildings in the complex, especially the nearby octagonal tower?

- When were the openings on the south (qibla) wall blocked? Were they functioning prior to the stealing of the luster tiles (ca. 1860–1900) and the early twentieth-century reconfiguration of the tomb and complex?

Two lines of evidence are relevant to the tomb’s construction. The first are genealogical sources that document Yahya’s mashhad in Varamin between the tenth and twelfth centuries (see Khamehyar’s essay). The second is found in the tomb itself: the foundation inscription dated 707/1307. As discussed in our essay on the stucco band, the inscription begins with سعی بانشا هذه العمارة (Efforts were made to construct this building). Sheila Blair suggests that the term العمارة was typically used in Ilkhanid Iran to refer to structures that were restored or rebuilt.19 If we agree with her interpretation, in the case of the Emamzadeh Yahya, this term might refer to a new building constructed on the site of an older structure, likely with a similar function. In other words, the inscription might memorialize a new building that replaced an older shrine, possibly the one mentioned in genealogical books.

What we know about the stucco and luster decoration:

- The four sets of dates summarized above

- The plastered brickwork (see figs. 20–21) appears to have been completed at the same time as the stucco inscription dated 707/1307. In other words, the stucco inscription was not applied over an earlier layer of plastered brickwork.20

Outstanding questions:

- How did the luster and stucco commissions impact the structure, and vice versa?

- When exactly were the luster tiles installed? We do not interpret the dates on the tiles as reflective of actual installation. In other words, just because the mihrab is dated 663/1265 does not mean it was installed then. The dates on all three sets of luster tiles (stars and crosses, mihrab, cenotaph tombstone panel) are vague and likely reflect different stages of production. The mihrab’s date may have been sketched out by the calligrapher at the beginning of the process, before the tiles were made.21 By contrast, the dates written on the stars and crosses are the potters’ direct hands and likely reflect the final steps of painting with luster pigment before firing.

- What did Dieulafoy mean by this phrase: “Toutes les faïences à reflets métalliques du mihrab, du lambris et du tombeau ont été posées bien après la construction du deuxième imamzaddè, et l’on a dû, afin de les placer, détruire une partie de la décoration primitive” (All of the luster tiles of the mihrab, walls, and tomb [cenotaph] were installed well after the construction of the second emamzadeh and part of the original decoration had to be destroyed in order to install them)?22 Was she referring to the changes made around the openings on the qibla wall?

The evidence currently available to us (December 2024) and at a distance (unable to re-inspect physical features in the tomb directly) is insufficient to provide definitive answers to these questions. What we can emphasize here is that the wholesale removal of the tomb’s tiles caused irreparable damage to the building and our ability to reconstruct its historical narrative. In other words, the plundering of the luster tiles, along with significant alterations to the site in the early twentieth century (see A Period of Uncertainties), has made it nearly impossible to trace the building’s evolution with certainty. At present, we generally favor the hypothesis that the gonbad-khaneh was a new structure built and decorated during the Ilkhanid period, instead of a renovation to a pre-existing building. Similar to the ʿAlaoddin tower (dated 688/1289–90), this process seems to have unfolded in stages and possibly experienced delays.23 Moving forward, it is hoped that the emergence of new evidence and continued non-destructive structural analysis will help to resolve some of these questions about the building’s formative stages.

Safavid-period Features and Resonance, ca. 1500s–1600s

Our knowledge of the Emamzadeh Yahya during the Timurid period (ca. 1370–1507) is very limited, but from the Safavid period (1501–1722), we have at least three sets of important primary sources. The first reveals the tomb’s continued vibrancy for ziyarat. At least three of the seventeen surviving yadegari are dated to the Safavid period (988/1577, 997/1589, 998/1590), as read by Nazanin Shahidi Marnani (fig. 25).

The second type of dated Safavid source are several historical tombstones (sang-e qabr-e tarikhi) scattered throughout the complex that attest an ongoing desire to be buried at the site. One example is a marble tombstone dated 963/1555–56, now remounted vertically in the southwest corner of the tomb (fig. 26).24 Another, dated 1086/1676 and belonging to a woman, was previously located in the courtyard but is now in the shrine’s storage (see Nakhaei’s essay, fig. 12).

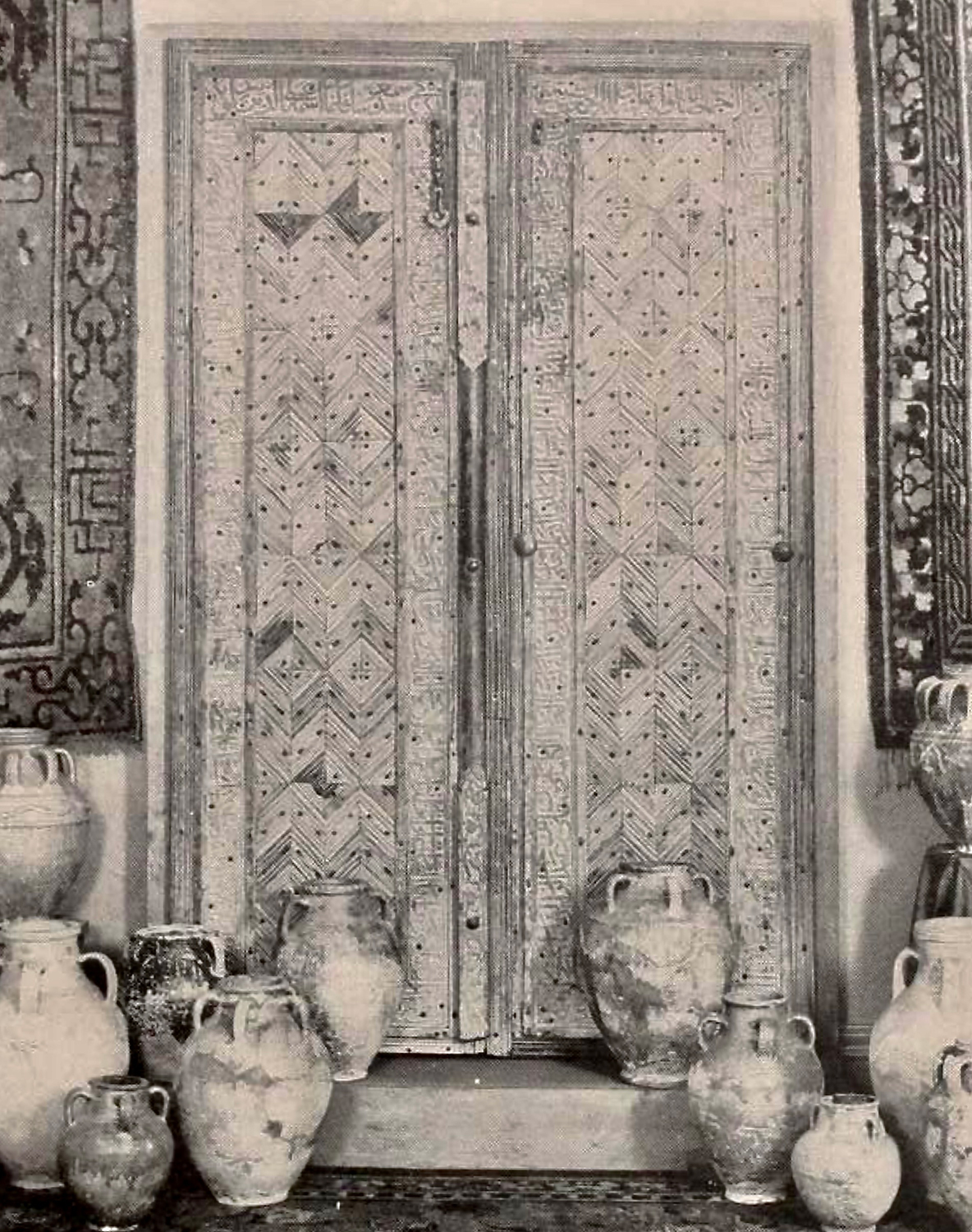

The last type of source is the tomb’s wooden door (Checklist, no. 15). Dated Safar 971/September 1563, this door illuminates Yahya’s lineage and confirms his descent from Emam Hasan: یحیی بن علی بن عبدالرحمن بن قاسم بن حسن بن زید بن حسن بن علی بن ابیطالب (Yahya b. ʿAli b. ʿAbd al-Rahman b. Qasem b. Hasan b. Zayd b. Hasan b. ʿAli b. Abi Taleb). It also names the Safavid donor (waqif) and craftsman: ʿAbd al-Emam al-Ahmar va al-Asvad b. Mowlana Mohammad al-marhum al-mabrur (the deceased, the blessed) Mowlana Jahangir Mohtaseb Varamini, probably the official enforcer of public morality (mohtaseb), and Maʿsum Najjar (najjar for woodworker). Finally, it records the door’s endowment as waqf, prohibits its sale, gifting, or inheritance, and warns against any modification of the endowment’s conditions. Despite this warning, the door was stolen at some point after 1863.25 Given its absence, the reader might wonder how we know of its existence...

Qajar-period Historiography and Consumption, ca. 1860–1910

Our knowledge of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s Safavid door stems from transcriptions recorded during a Qajar royal visit and hunting trip to Varamin in Shaʿban 1279/January 1863. This documentation, which pertains both to the Emamzadeh Yahya and the congregational mosque, was recorded at the order of Qajar prince ʿAliqoli Mirza Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh (d. 1880), the first minister of sciences (vazir-e ʿolum).26 The different terms used to describe the visits to the mosque and Emamzadeh Yahya are notable. For the mosque, which was then in a ruinous state and out of use, tamasha (تماشا) is used, suggesting a touristic visit for pleasure. For the Emamzadeh Yahya, ziyarat (زیارت, pious visitation) is used, indicating that the building was not only active but maintained its status as a place of respect and reverence.27

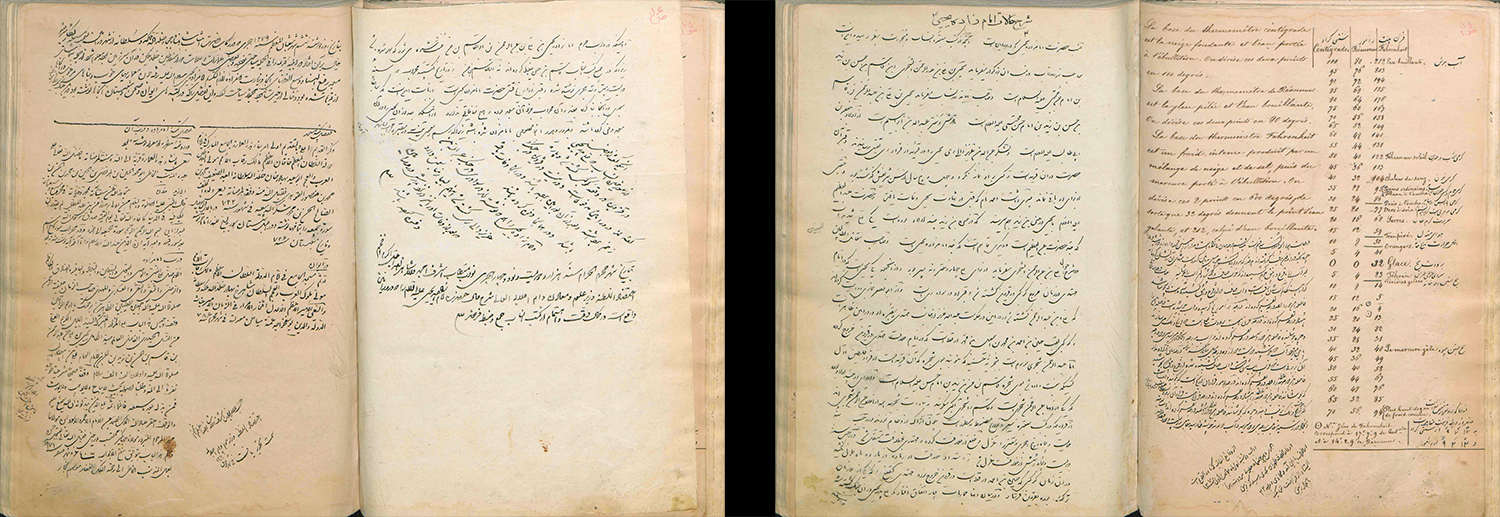

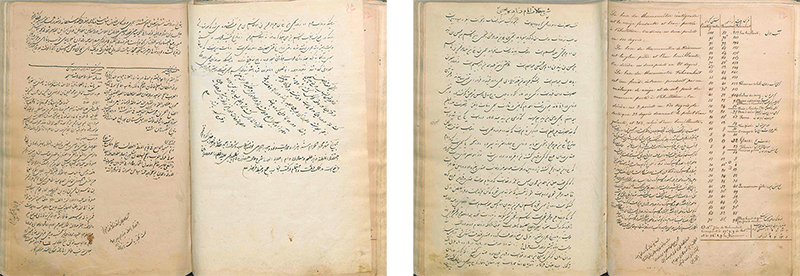

The 1863 field notes were ultimately appended to the end of a biography of Emamzadeh Yahya dated Moharram 1294/January 1877 and bound into a jong (miscellany of prose and poetry) compiled for Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh (fig. 27) (see Textual Source).28 For Qajar officials like Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh, the most important topic of study was Emamzadeh Yahya himself and his lineage from an Emam. This biographical research entailed the careful mining of genealogy books (kotob-e ansab) from the tenth century onwards.

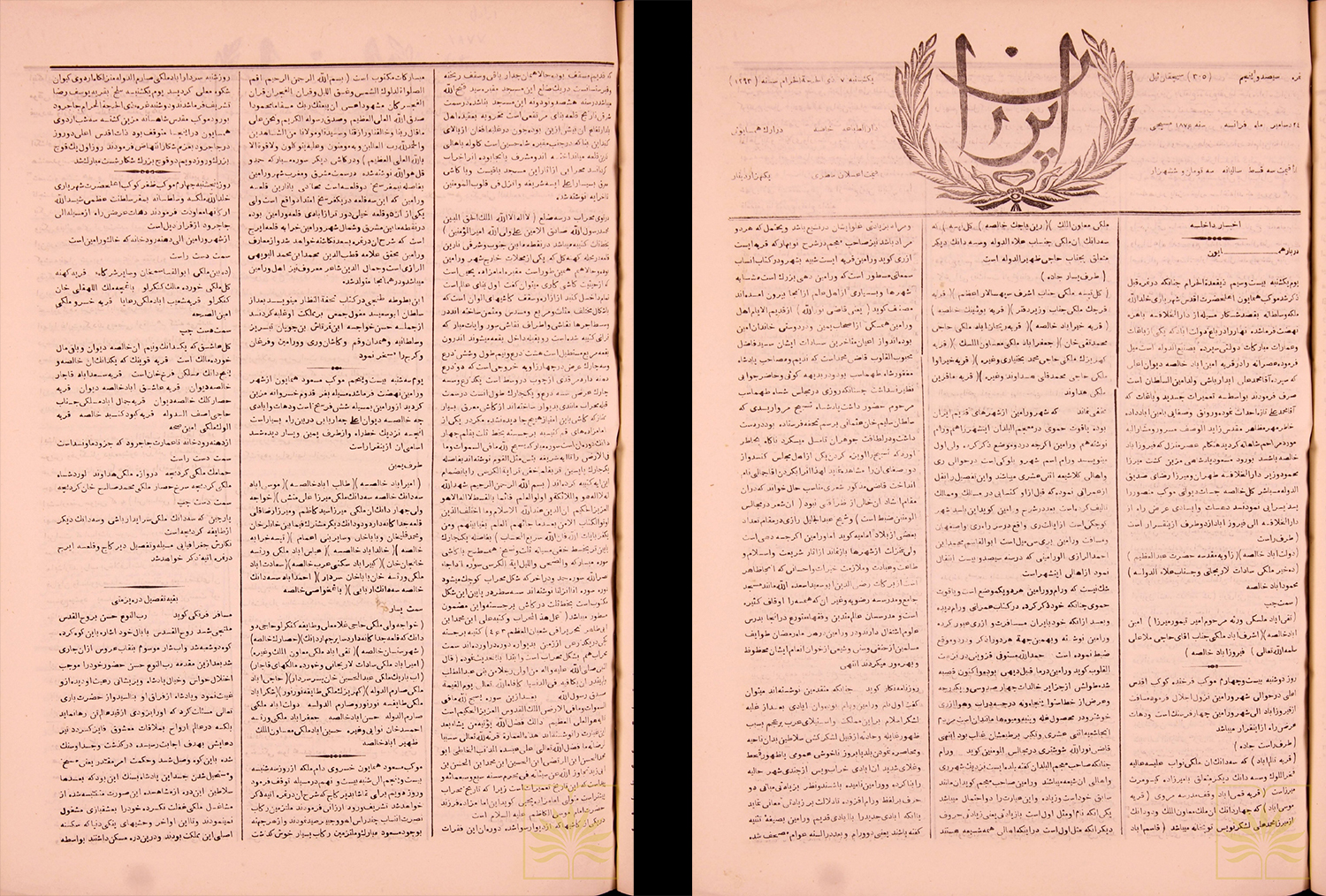

A second important Qajar court visit occurred thirteen years later. In December 1876, Mohammad Hasan Khan Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh (d. 1896) traveled to Varamin as part of a royal delegation bound for Masileh, a favorite hunting ground in the Dasht-e Kavir. At the time, he was titled Saniʿ al-Dowleh (only later to be titled Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh) and was the director of several newspapers.29 He published his account of Varamin in one such newspaper—Iran—just twelve days after his visit (fig. 28).30

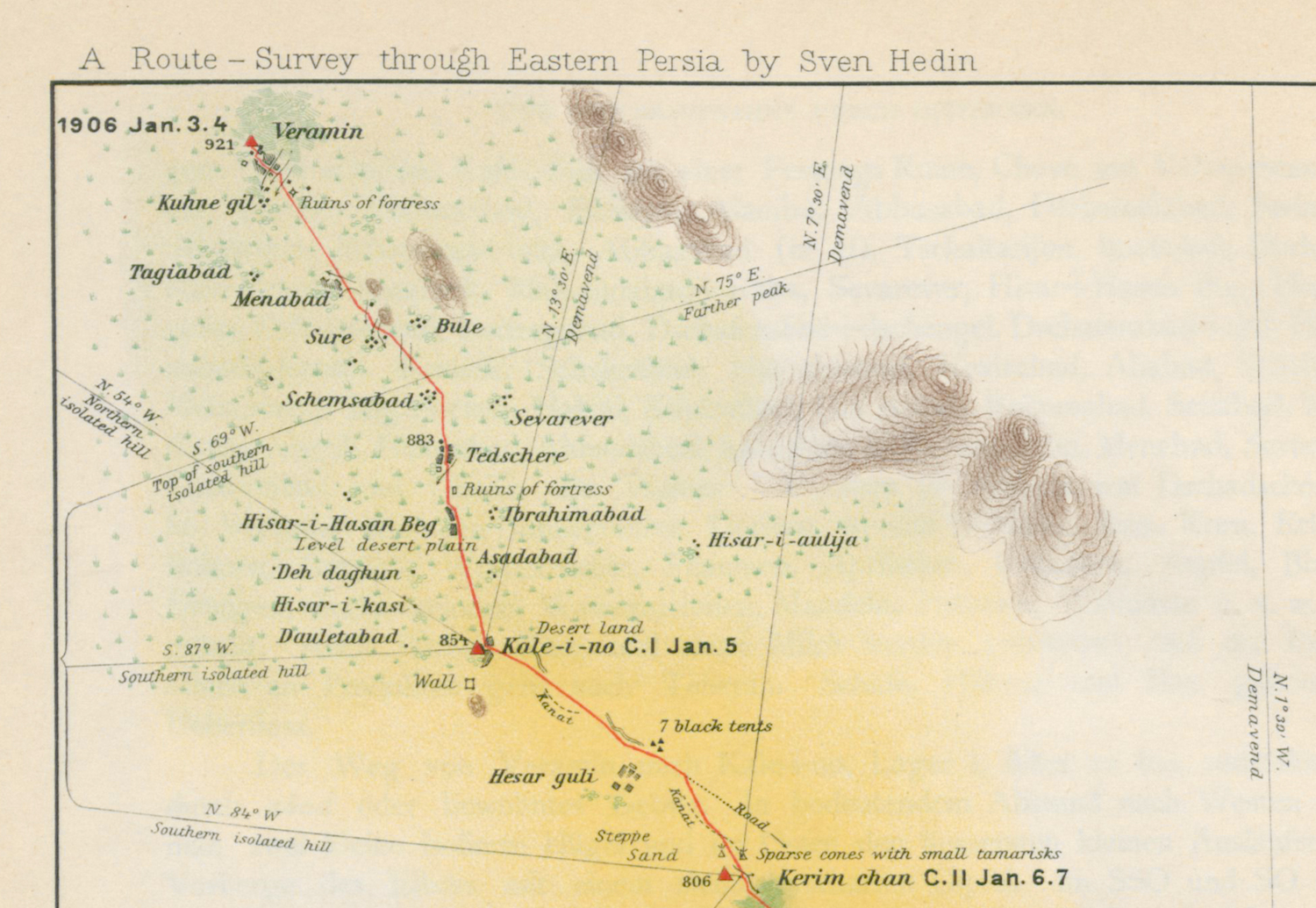

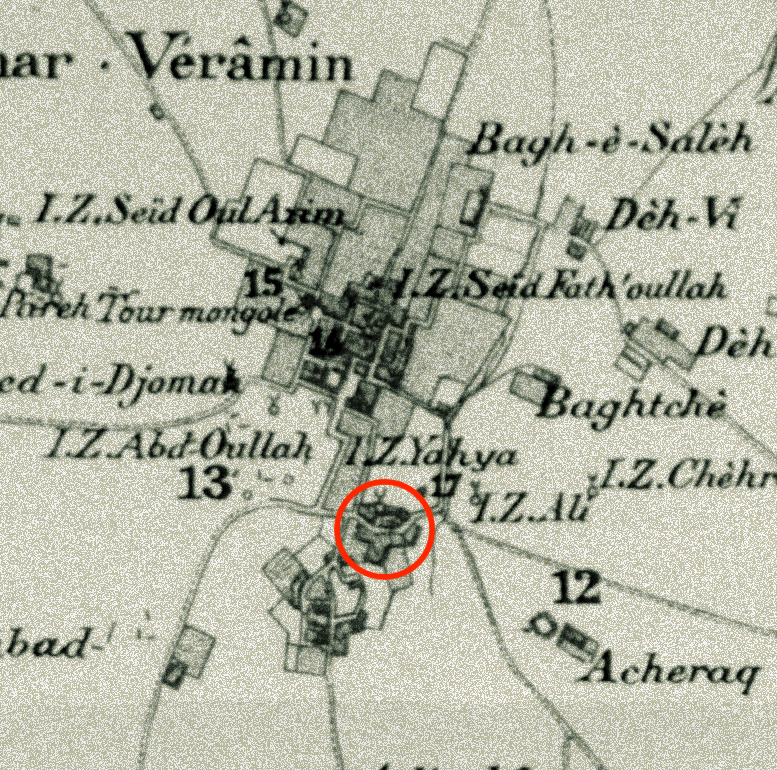

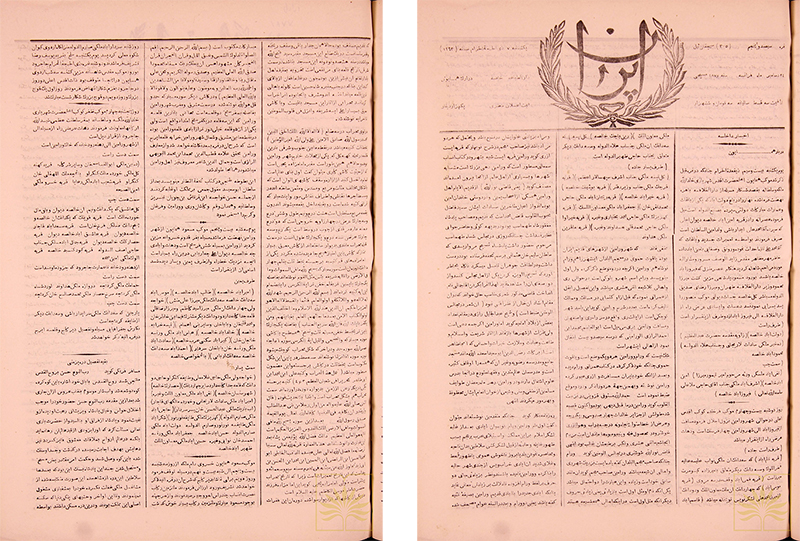

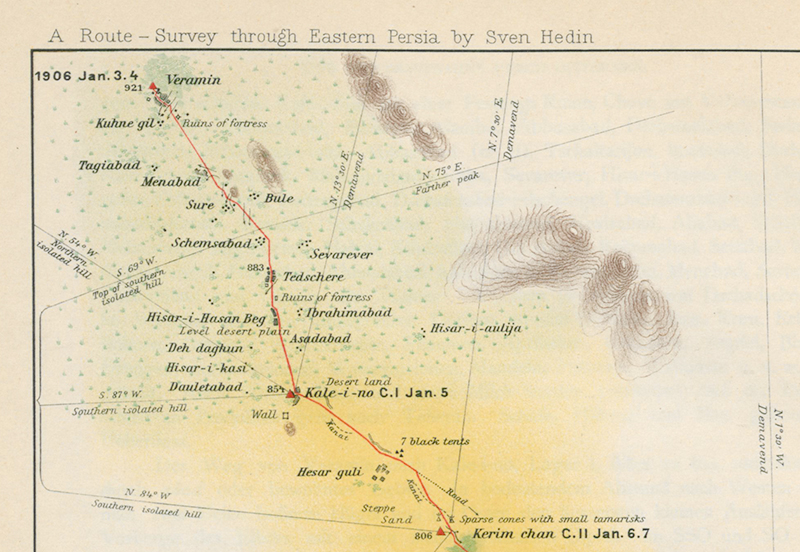

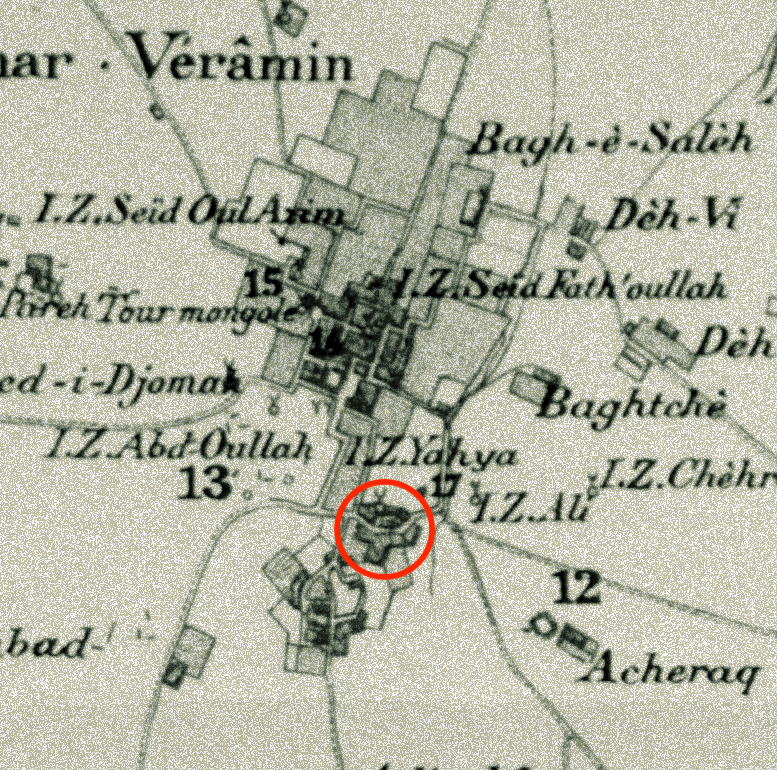

According to Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, the tomb (مقبره, maqbareh) of Emamzadeh Yahya was located southeast of Varamin’s central citadel (نارین قلعه, Narin qaʿleh) in a neighborhood called Kohneh Gel. This area, an external quarter (محلات خارج, mahalat-e kharej) of the medieval city, was separated from the large village (بزرگ قریه) of Varamin to the north, near the ʿAlaoddin tower.31 In order to visualize this relationship, we can refer to two maps produced in the opening decade of the twentieth century. The first is the map of Swedish explorer Sven Hedin (d. 1952), who passed through Varamin in January 1906 (fig. 29). His map indicates “Kuhne gil” (Kohneh Gel) next to “Veramin,” and his account reads: “In Kohneh-gel, a village to the south, is Imamsadeh-Yahiya [sic], a mosque-mausoleum, from which a mushtehid [mojtahed] states that valuable tiles have been stolen to be sold to Europeans in Tehran. Such plundering is a greater disgrace to the purchasers than the act of stealing itself.”32 The second is the planimetric sketch prepared by French archaeologist Lieutenant Georges Pézard in the fall of 1909 (fig. 30). Although this map does not name Kohneh Gel, it identifies the Emamzadeh Yahya (‘Imam Zadèh,’ 17) and shows the village’s scale in relation to Varamin to the north (note the ʿAlaoddin tower or ‘Tour mongole,’ 15). The space between Kohneh Gel and Varamin is filled with farmland.

While inside the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya in 1876, Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh took careful measurements (to which we shall soon return) and recorded inscriptions. He correctly identified most of the mihrab’s twelve sets of Qur’anic inscriptions but incorrectly read its date as 463/۴۶۳.33 He also read the Qur’anic inscriptions on two star tiles that had become dislodged from the wall (از دیوار سوا شده), thus confirming that some of these tiles still remained in the tomb.34 A few months before his visit, the South Kensington Museum in London (later V&A) had received a large number of tiles attributed to the tomb (see Handling Session).

Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh did not discuss the cenotaph, which could have been covered by tomb covers (Checklist, no. 7) and/or inaccessible behind the screen. As such, it is unclear if the luster cenotaph was still present. The Qajar historian was impressed by the tomb’s zarrinfam and concluded: که از حیثیت کاشیکاری میتوان گفت اول بنای عالم است (In terms of tilework, we can say that it [the Emamzadeh Yahya] is the most celebrated [lit. first] building of the world).35 The last statement likely contributed to the target on the tomb’s back among Tehran-based collectors and dealers, especially since it was published in a newspaper.

Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh’s newspaper article also seems to have redrawn attention to Yahya b. ʿAli. Just a month later, Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh completed his biography of the saint (see fig. 27). The conclusion of his research might have been inspired by Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh’s published assertation that Yahya was a descendant of Emam Musa, a point he learned from the the tomb’s motevalli.36 In his biography of Emamzadeh Yahya, Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh presented an alternative lineage from Emam Hasan based on his reading of genealogical sources and the tomb’s door (see Textual Source).

The next most significant sources for the study of the Emamzadeh Yahya are Jane Dieulafoy’s photographs taken during her week-long visit to Varamin in June 1881, as well as her related published accounts. Like Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh before her, Dieulafoy published her account of Varamin in a public forum; in her case, the January 1883 issue of the travel weekly Le tour du monde. She illustrated her article with two woodcuts after her photographs—her general view of the complex (see fig. 1) and a group of men seated at the entrance—and praised the tomb’s luster tilework as follows: “Il n’est effectivement pas possible d’obtenir des émaux plus purs et plus brillants, des teintes plus égales, que ceux des revêtements de l’iman Zaddeh Yaya” (It is not possible to obtain glazes that are purer and brighter, of more even shades, than those of the Emamzadeh Yahya) (fig. 31).37 She also emphasized how the tiles had been stolen and sold in Tehran for high prices.38

Dieulafoy took twenty-nine photographs in Varamin and four at the Emamzadeh Yahya (see Photo Timeline, Photo Album). One of her most important photographs is the aforementioned view of the luster mihrab showing it framed on three sides by three borders: a thin border likely of tiles, the border of luster half stars and crosses, and finally, the 707/1307 stucco inscription, dated forty-four years after the mihrab (fig. 32). This view is the critical contrast to, and context for, the current white void (fig. 33).

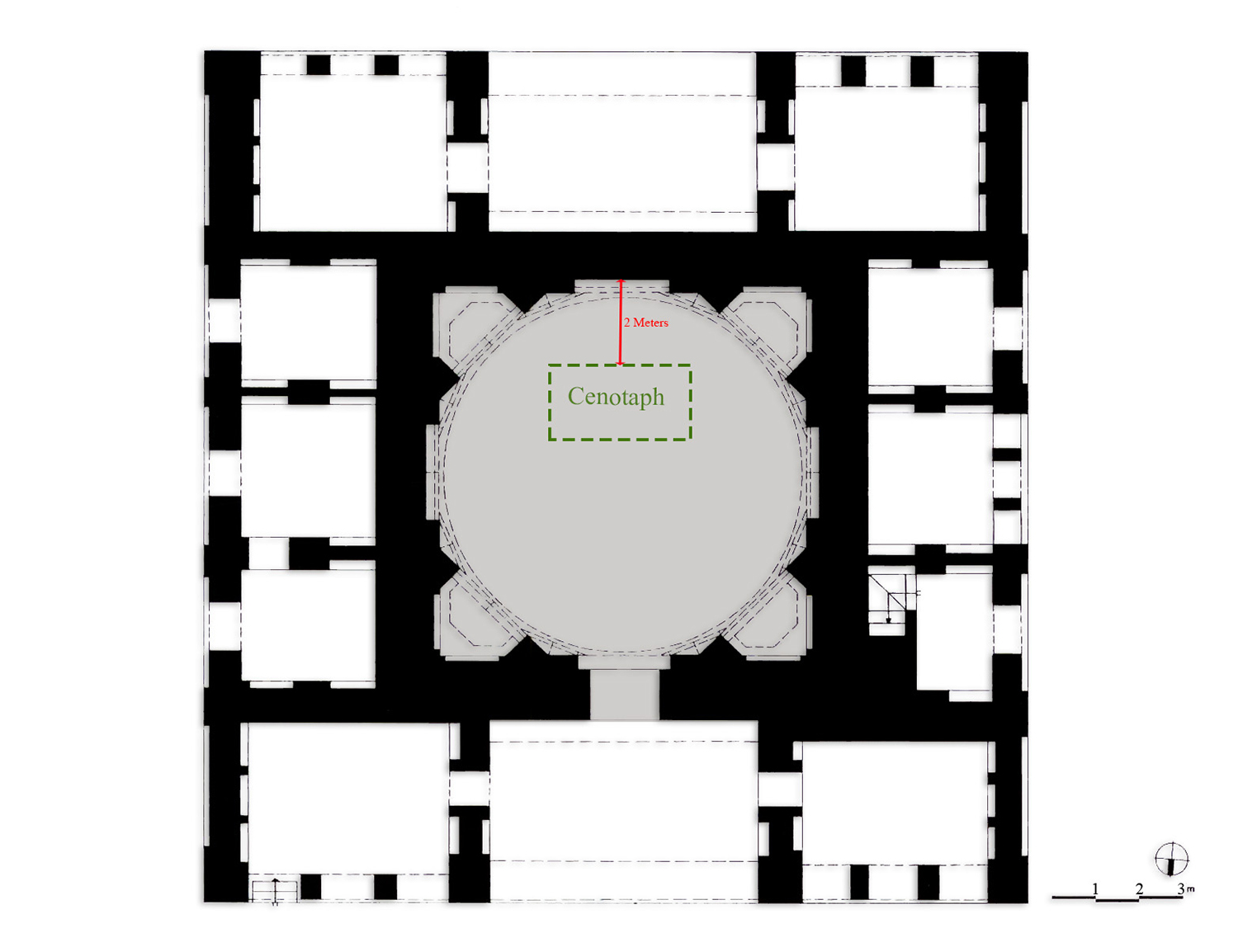

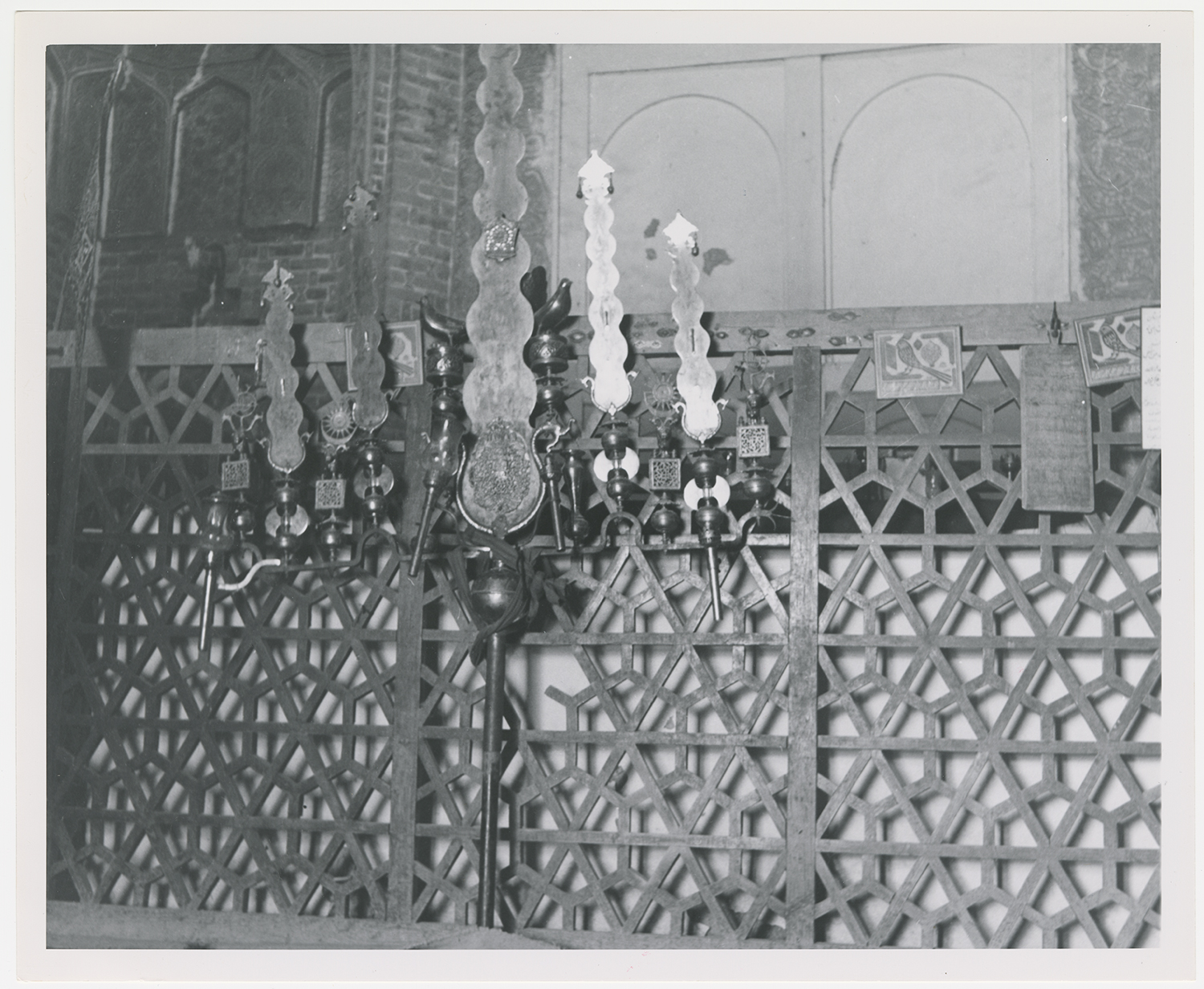

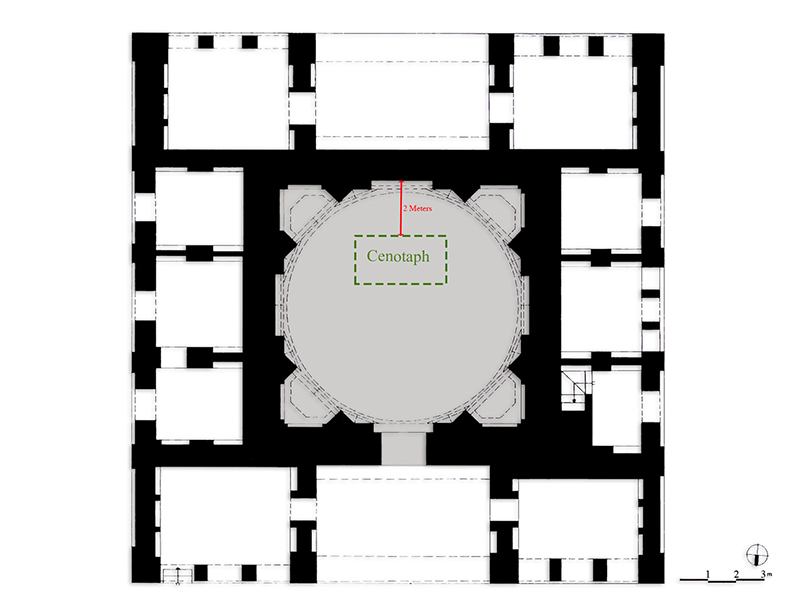

During the mihrab’s afterlife in Europe and the United States (ca. 1900–40), some of its over seventy tiles were lost or jumbled (see Mihrab: Essay). Thanks to Dieulafoy’s photograph, we can now appreciate many tiles in their correct place and also see the wooden screen that once enclosed the cenotaph, the most sacred area of the tomb. Using Dieulafoy’s 1881 photograph, Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh’s 1876 measurements of the same screen (338 × 182 cm; 11.09 × 5.97 ft), and computer simulation, we estimate that the screen was positioned approximately 2 meters (6.56 ft) north of the mihrab (fig. 34).39

Between the 1860s and 1900, all of the tomb’s luster tilework was stolen and primarily exported abroad through Tehran-based Europeans and Qajar dignitaries. The shrine’s proximity to Tehran and rising stream of visitation by Qajar officials and foreigners alike contributed to this steady plunder. Equally important were the public newspaper articles of Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh (December 1876) and Dieulafoy (January 1883), both of which praised the tomb’s luster tilework, named the site specifically, and would have contributed to this ‘tile grab’ (see Luster Market).

A Period of Uncertainties and Mysteries, ca. 1897–1923

The next chapter of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s history—the last years of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth century—remains largely a mystery. The last known photograph of the site in its original configuration was taken by Friedrich Sarre in December 1897 (see fig. 2). The poor quality of the published photograph limits our ability to identify certain details, but the monumental entrance portal, the main tomb, and the tip of the octagonal tower are clearly visible. Unlike Dieulafoy, Sarre did not obtain permission to enter the emamzadeh and hence did not photograph the tomb’s interior.40 In a later article, at which point he knew that the mihrab had been transported to Paris, he linked his restricted entrance to the ongoing plundering of the site.41 The person responsible for taking the mihrab to Paris for the purpose of sale and on the occasion of the Exposition Universelle (14 April–12 November 1900) was former chief state accountant and later war and prime minister Mirza Hasan Mostowfi al-Mamalek (d. 1932) (fig. 35).42

The exact timing of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s significant transformation into its current form—a single domed tomb at the center of a rectangular courtyard—is unknown. Evidence suggests that some of the major components of the complex (the entrance portal, the tomb tower) may have been gone by the early years of the twentieth century. In their account of Varamin based on their 1909 visit (see fig. 30), Georges Pézard and Georges Bondoux compare the Emamzadeh Yahya to the nearby Emamzadeh ʿAli (see City Tour), which consisted of only a domed tomb and an eyvan: “L’Iman [Imam] Zadeh Yaya est ancien, mais il n’a pas grand caractère. Il en est de même de l’Imam Zadeh ʿAli” (The [Emam]zadeh Yahya is old but does not have much character. The same is true of the Emamzadeh ʿAli).43 If the monumental entrance portal and tomb tower remained, they likely would have commented on them.

The next known evidence of the site’s condition was recorded in 1923 by German archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld (d. 1948). After Dieulafoy, he was the second European to document the tomb’s interior, but unlike Dieulafoy, his record is not visual. Instead, he wrote a relatively complete transcription of the stucco inscription in his sketchbook, indicating that he spent some time inside the tomb. In an article published in 1926, he stated, “Die andere Moschee, die einst den wundervollen, gestohlenen Goldlüster Mihrāb besaß, ist verschwunden” (the mosque which once had the wonderful stolen golden luster mihrab had disappeared).44 Herzfeld’s confusion—his failure to realize that the remaining tomb was indeed the original home of the mihrab—may be due to the major changes in the site’s overall configuration. Moreover, his inability to recognize the mihrab’s original location on the qibla wall of the tomb might be attributed to interventions in the interior, such as the addition of new underglaze rectangular tiles to replace the stolen luster ones (see figs. 8–9).45 We must leave open the possibility that the empty space of the mihrab might have been covered in some way, potentially leading to Herzfeld’s misinterpretation.

The addition of the Qajar-period replacement tiles indicates that the reconfiguration of the Emamzadeh Yahya to its current plan might not have been a typical case of renovation (in the sense of being a neutral or standard physical preservation of a site). Instead, it could have been part of a larger plan to conceal the systematic plunder of the tomb’s tiles. Among the 42 known sites associated with luster tiles, the Emamzadeh Yahya stands out as a rare example of new tiles being added to the walls soon after the originals were stolen. In other cases, the stripped walls were either left untouched (for example, the shrine of ʿAbd al-Samad in Natanz), covered with a layer of plaster (for example, the Mir Emad Mosque in Kashan), or redecorated with tiles much later as part of beautification efforts by their managing institutions (for example, the Emamzadeh ʿAli b. Jaʿfar in Qom) (see Sites). It is also important to emphasize that the adding of the Qajar-period tiles was a significant intervention and one that would have been orchestrated by someone with means. This leads us back to the individual responsible for the removal of the luster mihrab before 1900: Mirza Hasan Mostowfi al-Mamalek. In addition to taking the mihrab (and possibly other luster tiles) to Paris, could Mostowfi al-Mamalek have also ordered the major reconfiguration of the site, including the destruction of all structures except for the tomb, the renovation of the tomb with new external features (discussed further below), and the cladding of its interior with new tiles?46

Despite the plunder of likely all of its luster tilework by 1900, the Emamzadeh Yahya continued to be the focus of ziyarat. On 10 Moharram 1332/9 December 1913, a pilgrim wrote a yadegari at the beginning of the hadith on the west wall recording his visit “on the morning of the day of Ashura” to “this pure shrine” (این مرقد مطهر) (fig. 36; see also Shahidi Marnani’s essay, no. 14). While pilgrims continued to visit the tomb, its tiles were purveyed abroad. Two weeks later, on 23 December 1913, the Stieglitz Central School of Technical Drawing in St. Petersburg accessioned a large shipment of luster tiles from the tomb, including the cenotaph tombstone and many stars and crosses (Checklist, no. 19). A few months earlier, in August 1913, Armenian-American dealer Hagop Kevorkian (d. 1962) tried to sell the mihrab, which he had acquired from Mirza Hasan Mostowfi al-Mamalek, to Detroit-based industrialist-collector Charles Freer (d. 1919).47

New Configuration and Registration as National Heritage, 1930s

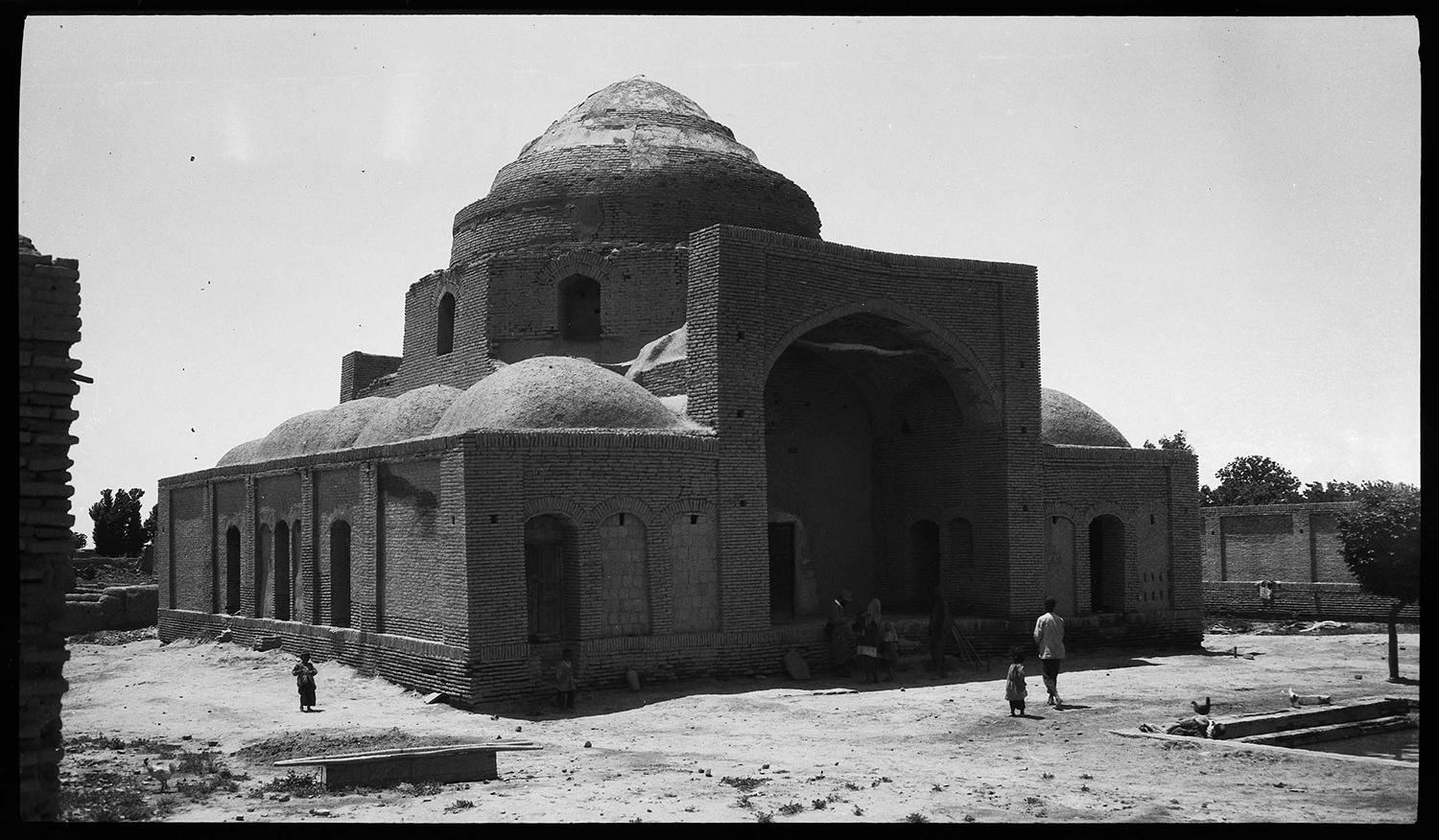

A photograph taken by French architect and archaeologist Albert Gabriel (d. 1972) in 1934 is the earliest known dated image of the complex following its major alterations. It captures the northeast side of the tomb and nine people in the courtyard, including small children and a baby (fig. 37).48 There is no longer any trace of the monumental entrance, conical tower, and the walls connecting parts of the shrine (see fig. 1), and the tomb (gonbad-khaneh) is now a solitary building set in the middle of a rectangular courtyard. On the east and west, it is ringed by a series of lower domed rooms likely intended to reinforce the structural integrity of the damaged and now isolated tomb and to facilitate the daily functions of the complex (storage, cooking, administration, lodging). There is also an eyvan on the north, repeated by a just visible example on the south. While the latter appears to have been a new intervention, the north example replicated, on a smaller scale, the pre-existing eyvan just visible in Dieulafoy’s photograph (see fig. 1).

In addition to the tomb, the site’s walls and surrounding spaces were also altered. The new wall on the north was constructed close to the location of the original entrance, and some previous structures, including an ab anbar (water reservoir or cistern), and numerous graves were impacted in the process (fig. 38). A photograph of the complex taken from the northeast shows a roofed structure abutting the new wall and a doorway leading into an adjacent space (fig. 39).

The clearing of the south (back) side of the complex seems to have taken longer. On the far left of Gabriel’s frame, some low walls still stand in this area of the courtyard (see fig. 37). The same walls are visible in the foreground of Godard’s photograph of the back of the tomb (see fig. 24). A photograph taken by Donald Wilber further away in a field to the southwest captures the many mud walls and remnants of ruined structures behind the reconfigured complex (fig. 40).

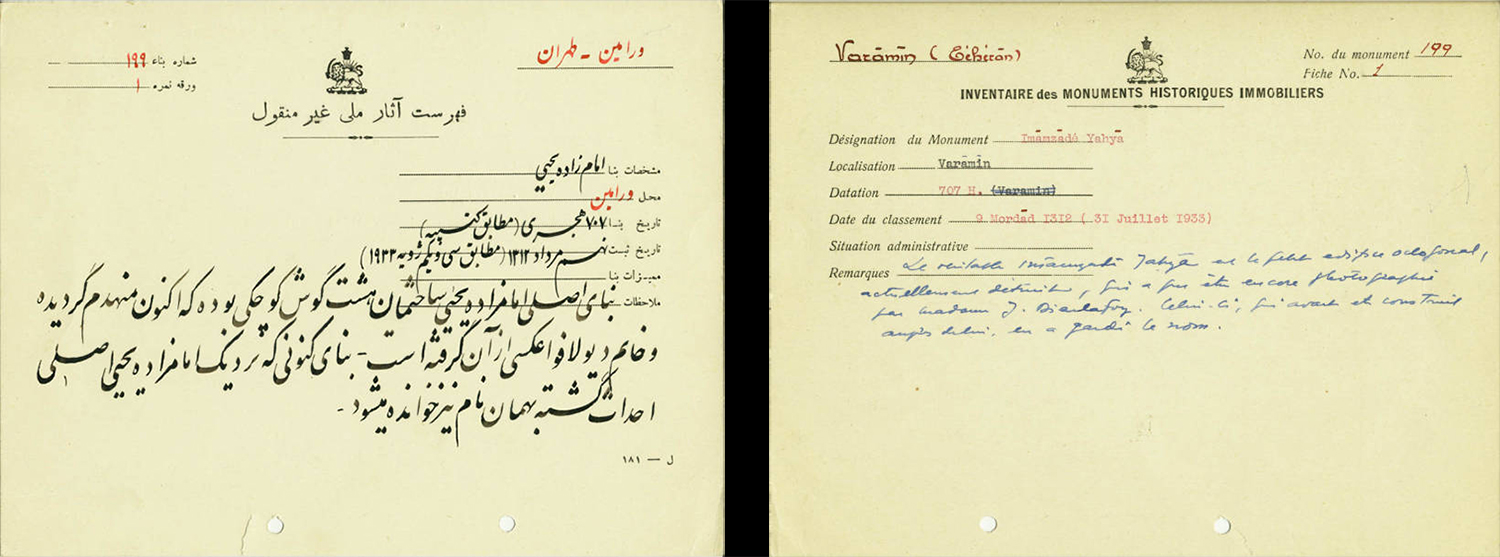

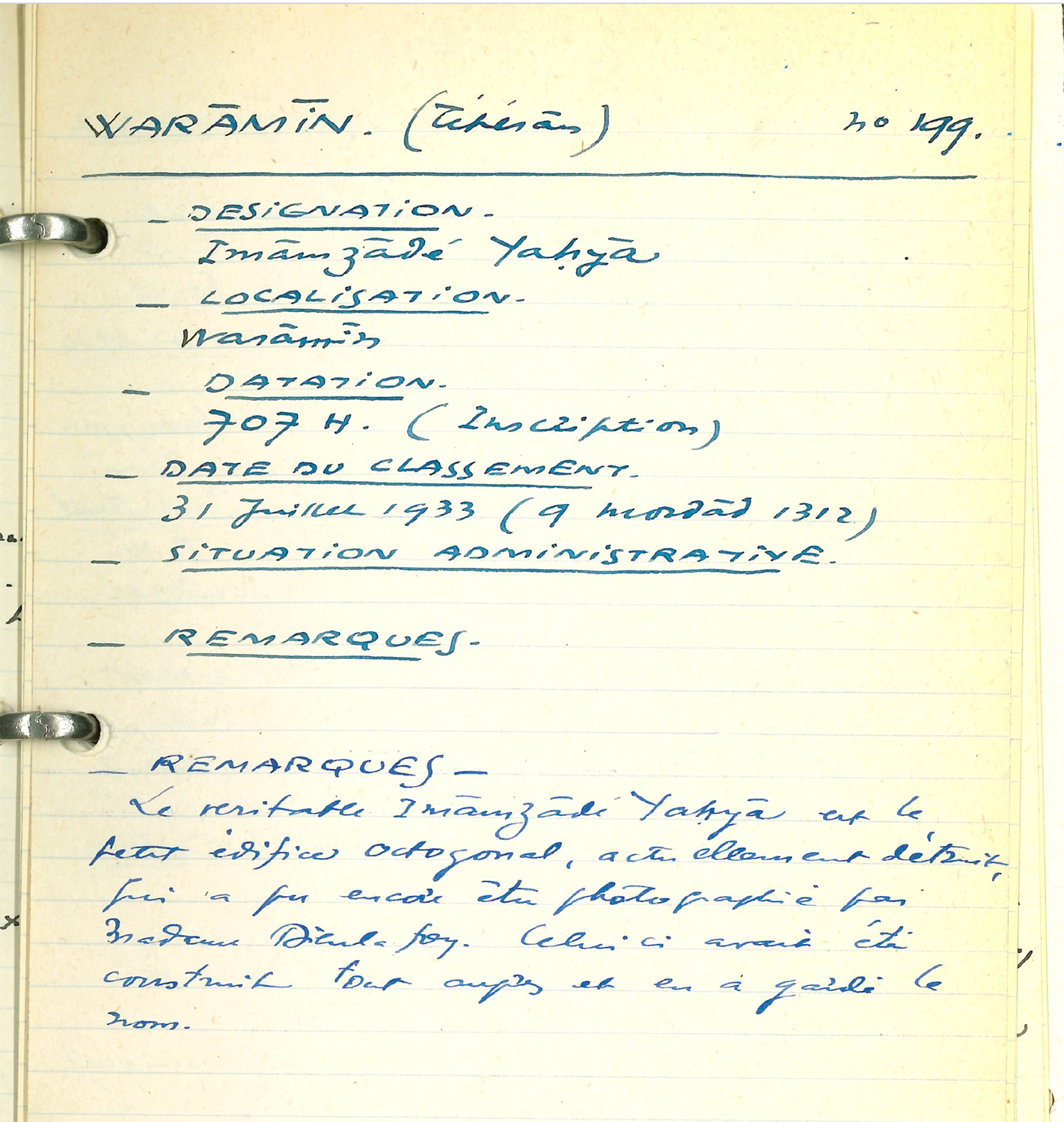

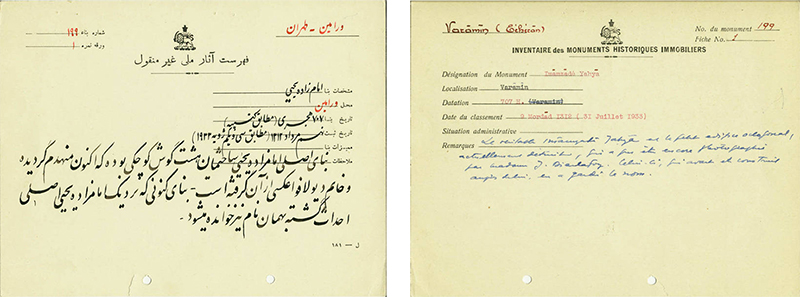

In 1933, one year before Gabriel’s photograph, the Emamzadeh Yahya was registered as a national heritage site.49 A reference to the site’s major alteration appears in its bilingual registration cards, which describe the conical tower as destroyed and as ‘the original Emamzadeh Yahya’ (fig. 41):

بنای اصلی امامزاده یحیی ساختمان هشتگوش کوچکی بوده که اکنون منهدم گردیده و خانم دیولافوا عکسی از آن گرفته است. بنای کنونی که نزدیک امامزاده یحیی اصلی احداث گشته بهمان نام نیز خوانده میشود.

Le veritable Imāmzadé Yahyā est le petit édifice octogonal, actuellement détruit, qui a pu être encore photographié par Madame J. Dieulafoy. Celui-ci, qui avait été construit auprès [?], en a gardé le nom.

The original building of the Emamzadeh Yahya was a small octagon, now destroyed, and Madame Dieulafoy took a photograph of it. The current building, constructed near the original Emamzadeh Yahya, is also known by the same name. [translated from the Persian]

The French version of this note was written by Godard, the then newly appointed director of the Archaeological Services of Iran, and parallels an almost verbatim note written in his field notebook (fig. 42). Like Herzfeld, on whom he likely based his claims, Godard did not recognize the standing domed tomb as the main tomb.50

At the time of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s registration, Kohneh Gel was still a remote village separated from central Varamin by vast agricultural fields. An aerial photograph taken in 1956–57 confirms that it remained relatively isolated into the middle of the twentieth century (fig. 43).51

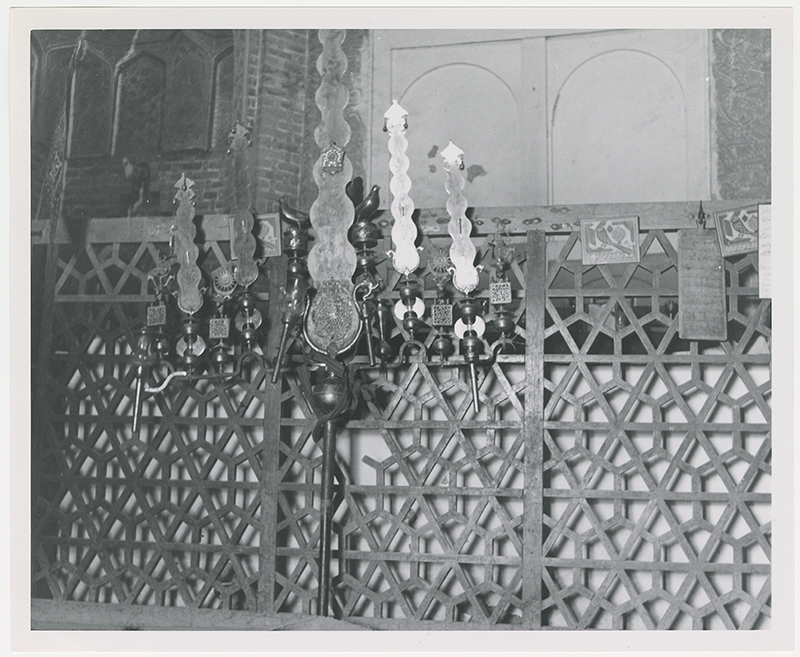

In April 1958, American architectural historian Myron Bement Smith (d. 1970) and a companion visited the Emamzadeh Yahya and took an important photograph of the screen shielding the cenotaph, the same example photographed by Dieulafoy eighty years earlier (fig. 44; see Ritual Objects). In this photograph, the screen is covered in ritual objects, the mihrab is just a white void in the distance with two round arches, and the cenotaph is also plastered white.

At the time, the Emamzadeh Yahya was the central ritual space of the Kangarlu tribe and a significant hub for Moharram ceremonies. As recalled by local historian Mohammad Amini (see Oral History) and documented in a film taken by a resident in 1967, the shrine served as a destination, starting point, and stopover for various processions (dasteh) (fig. 45). The open spaces surrounding the Emamzadeh Yahya could accommodate these large crowds, and an aerial photograph taken around the same time helps us to appreciate the shrine’s prominence in the village (fig. 46).

Comprehensive Restoration, Refurbishment, and Urban Renewal: early 1980s to the present

During the Islamic Republic (1979–present), the shrine has continued to experience refurbishment. Between 1983 and 1985, Mohammad Hasan Moheb-Ali oversaw the systematic restoration of the site under the auspices of the National Organization for the Preservation of the Historic Monuments of Iran (سازمان ملی حفاظت آثار باستانی ایران) (see Preservationists). These efforts consolidated many of the architectural elements discussed here, including the stucco windows (see fig. 18) and the large stucco panel above the mihrab (see fig. 16). It also revealed other important surfaces and elements, including the imprints of the half stars and crosses once bordering the mihrab (fig. 47) and passages of original plastered brickwork with stucco plugs on the back wall of the north eyvan (figs. 48–49).

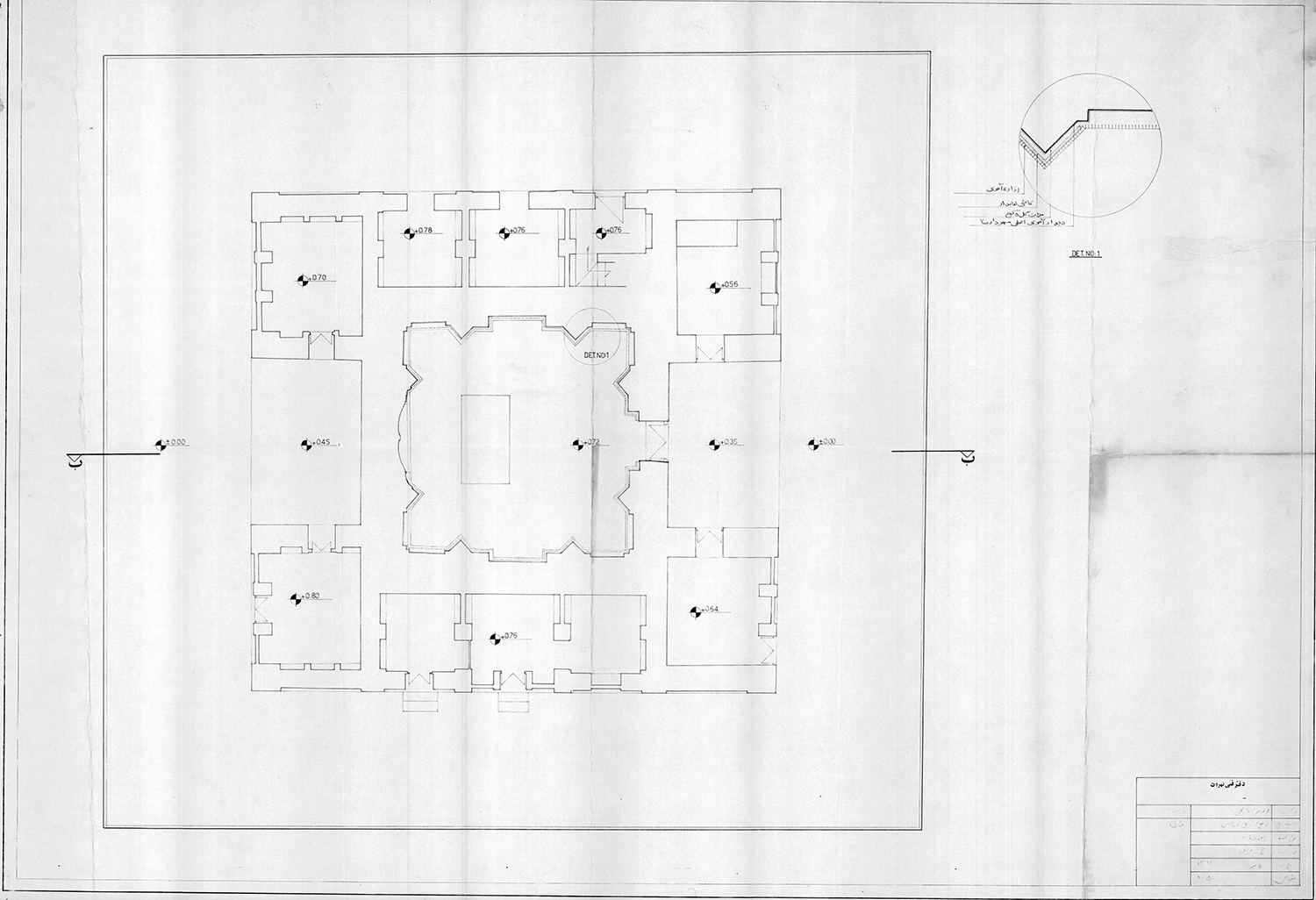

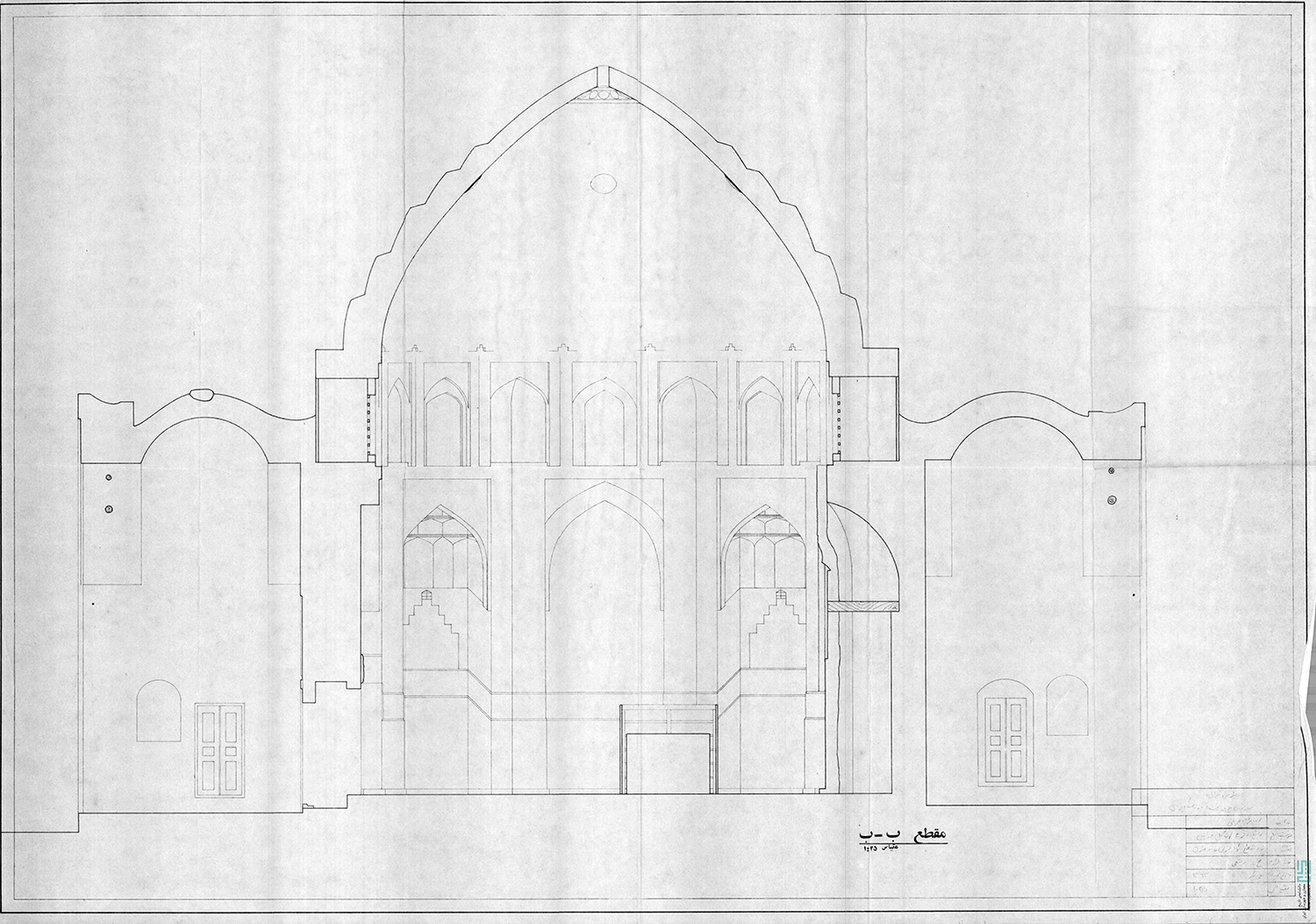

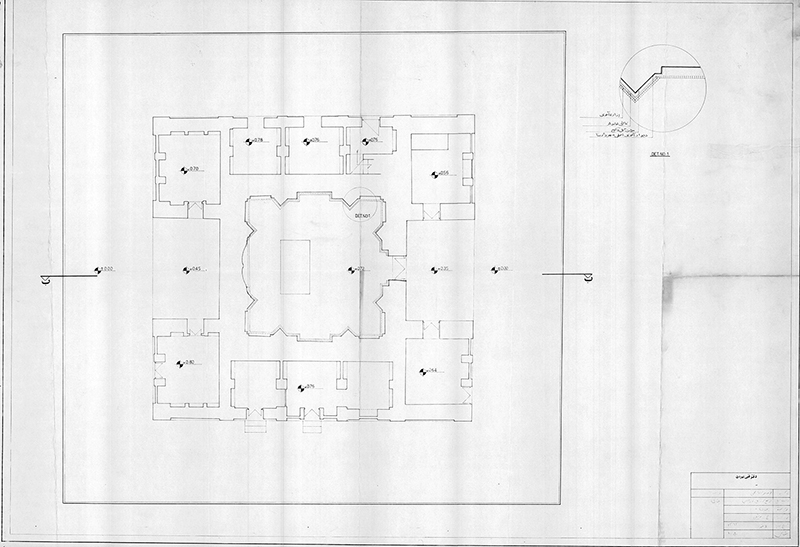

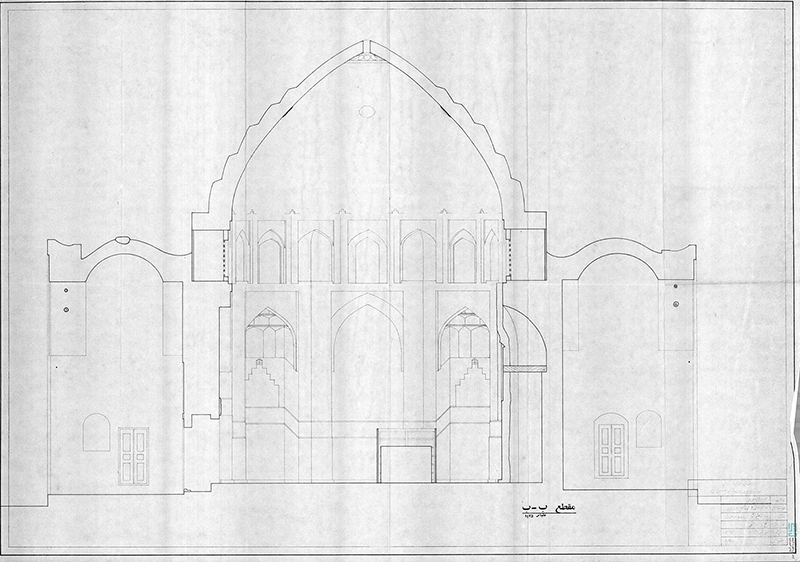

At the end of the restoration, three detailed architectural drawings were created of the domed tomb and its surrounding rooms, including a plan, west section, and north façade (figs. 50–51). In the first two, a rectangular screen is visible, which appears to be the same one depicted in the photographs of Jane Dieulafoy and Myron Bement Smith (see figs. 32, 44). The size of the cenotaph matches the dimensions provided by Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh in 1876, and its location aligns with the position proposed in the computer-aided analysis of Dieulafoy’s photograph from 1881. An interesting feature in the west section is a large niche behind the mihrab wall, with a wooden horizonal support. This feature is not visible in the plan drawn by the same person, which raises many questions, including about the feasibility of having such a large arch on one of the main sides of the structure. We continue to think about this issue.

During the revision of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s registration document in 1375 Sh/1996, the site was confused with the Emamzadeh Yahya in Tehran’s Oudlajan neighborhood (map) (Checklist, no. 24). As a result, a four-page report on the Tehran site was incorrectly attached to the registration document for the Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin.52 This confusion likely occurred because both shrines share the same name and featured octagonal towers with conical domes. The Tehran shrine was entirely destroyed in 1318 Sh/1939–40 during the construction of a sports court in the adjacent cemetery and then partially rebuilt.53

In 1389 Sh/2010–11, the Emamzadeh Yahya received a new hexagonal zarih, the third known example in the tomb (Checklist, no. 5). It was preceded by an aluminum screen that in turn replaced the wooden one, a portion of which remains in storage at the shrine (figs. 52–53 and Checklist, no. 4).54

The complex’s exterior and immediate surroundings have also received upgrades. Between 2013 and 2018, tilework was added to the north entrance gate. This tilework announces the Emamzadeh Yahya as an astan-e moqaddas, or holy shrine, indicating its identity as a multi-functional complex. The complex’s continued importance is further attested by extensive urban renewal directly in front of this entrance. A recently completed large park/plaza includes greenery, benches, lighting, a central planter in the shape of an eight-pointed star, and a large memorial to the site (figs. 54–55). The last identifies Emamzadeh Yahya as a descendant of Emam Hasan, provides the site’s date of registration as national heritage (1312 Sh/1933), names those responsible for the current improvements (behsazi), and is dated 1398 Sh/2018–19. This date appears to mark the commencement of the project and can be considered part of the seven-hundred-year chain of patronage and refurbishment of the Emamzadeh Yahya.55 This beautified zone in the north has a grandeur that is much different from the side and back entrances serving the neighborhood and the meydan (square) to the south, which is known locally as the site of Yahya’s martyrdom (qatlgah) (see Site Tour).

***

This essay has traced the evolution of the Emamzadeh Yahya over seven hundred years through all currently known and accessible sources. Moving beyond the Ilkhanid monument has revealed the site’s many layers and continuous use and refurbishment. While much of the building is irreparably damaged and lost, we are fortunate that many sources remain to piece together its fascinating histories. A meticulous examination of these sources has revealed the shrine’s resilience against repeated efforts to compromise its integrity and remarkable capacity to endure as a sacred space, even after losing important architectural structures and elements. It has also illuminated the many individuals who have interacted with the site over time, including the pilgrims who visited continuously over the centuries and inscribed notes on its walls, the Qajar-period officials and foreigners who researched the saint and recorded inscriptions, and the preservationists involved in its restoration forty years ago. Methodologically, this diachronic history raises the potential of similar approaches to other monuments that are generally defined by their production period alone. A single ‘little’ building can become quite a history class and resonate across many fields.

Like the Emamzadeh Yahya itself, the writing of the shrine’s history is a living work in progress. As new sources come to light and additional fieldwork is conducted, our understanding of the site will inevitably expand and improve. One such fortuitous circumstance transpired as we were finishing this article. In late October 2024, V&A curator Fuchsia Hart sent a text alerting us to this page from a 1915 sales catalog offering a door “from the city of Veramin (near Tehran).”56 Thankfully, the sales catalog reproduced the door and even summarized its inscriptions, and it was immediately clear that this was the door of Emamzadeh Yahya’s tomb (fig. 56). From the 1863 Qajar account, we knew that the door was an important commission and covered in detailed inscriptions, including critical evidence of Yahya’s lineage. We can now appreciate its actual appearance and hope that it will soon be located.

Citation: Keelan Overton and Hossein Nakhaei, “Chronological Overview of the Emamzadeh Yahya Complex, ca. 1200–2024.” Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.

Notes

Acknowledgments: We are grateful to Hamid Abhari, Mohammad Amini, Maryam Rafeienezhad, Jabbar Rahmani, Nazanin Shahidi Marnani, and Fatemeh Gharib for sharing information, research, and recent photographs and videos that have advanced our efforts from afar and enabled this interdisciplinary, multi-media synopsis. Thank you also to the many curators, archivists, and officials who granted access to key texts, photographs, and collections.

- For a summary of the site in both Persian and English, see its entry in the Ganjnameh, vol. 13: Haji-Qassemi (ed.), “Varamin, Emamzadeh Yahya,” 82–87 (English), 164–69 (Persian). ↩

- Abolfaraj Esfahani, Maqātil al-ṭālibīyyīn, 530. ↩

- Some important art historical studies of the site include Donald Wilber’s section in his Ilkhanid Architecture of Iran, no. 11, 109–11 (based on his May 1939) visit and Sheila Blair’s “Architecture as a Source” and “Art as Text.” ↩

- Dieulafoy, “La Perse, La Chaldée La Susiane,” 72 and La Perse, la Chaldée et la Susiane, 147. For further background on these two publications, see Overton, “Jane Dieulafoy in Varamin.” All citations herein are to La Perse while acknowledging that Dieulafoy’s Le tour article was published four years earlier and much more accessible. ↩

- Dieulafoy, La Perse, 148–49. ↩

- Any emamzadeh is also a space of prayer and can contain a mihrab, but this does not make it definable as a mosque. Wilber, The Architecture of Islamic Iran, 109, suggests that Dieulafoy was referring to the arcades along the narrow court. ↩

- Dieulafoy, La Perse, 148–49. ↩

- Wilber, The Architecture of Islamic Iran, cat. no. 11, 109–11 and fig. 6 (the plan). Blair, “Art as Text,” 435, fig. 14, reproduces his plan. ↩

- Dieulafoy describes the tower as literally “joint à” (attached to) the Emamzadeh Yahya. Dieulafoy, La Perse, 150. ↩

- These inscriptions have been known to scholars for some time. See, for example, Wilber, The Architecture of Islamic Iran, 110. ↩

- Several emamzadehs are known to have had luster tiles with Persian poetic verses. Consider, the Emamzadeh Jaʿfar in Damghan, Emamzadeh ʿAli b. Jaʿfar in Qom, Emamzadeh Habib b. Musa in Kashan, and Emamzadeh Mohammad in Kharg. For further background, see Watson, Persian Lustre Ware, 131–49 and 186–87 and Sites and Interiors here. As such, any assumption that tiles with Persian verses were exclusively intended for ‘secular’ buildings, such as palaces, should be reconsidered. ↩

- In 1933, Abdullah Chughtai argued for Samarra as their place of production, based on his reading of tiles in the Ashmolean. See Chughtai, “Lustred Tiles from Samarra.” It is hoped that the scientific analysis project in progress might resolve some questions around production sites. ↩

- Translation from Blair, “Art as Text,” 409. ↩

- One other tomb of a Yahya is known to have been decorated with luster tilework: the Emamzadeh Yahya b. Zayd near Gonbad-e Kavus. See Mostafavi, “Khānevādeh-ye honarmand,” 31. ↩

- Blair’s interpretation in “Architecture as a Source,” 225, requires some revision. She based her reading on the transcription in Répertoire chronologique d’épigraphie arabe, vol. 13, no. 4912, which has some errors, notably the al-hasani for the Varamini family’s lineage. This led her to identify the Varamini family as Hasanid (descendants of Emam Hasan). Ghouchani revised and corrected the Répertoire transcription and used primary sources to trace the family’s genealogy, showing that they were Hosaynid (descendants of Emam Hosayn). Ghouchani, “Barrasī-ye katībeh-ye ārāmgāh-e ʿAlā al-Dīn,” 59–61. ↩

- The roundels at the dome’s apex bear the names of the Twelve Shiʿi Emams. The name ‘Jaʿfar,’ the sixth Emam, was originally before ‘Musa,’ the seventh Emam. During the early 1980s restoration campaign, this name was mistakenly restored as ‘Hosayn.’ ↩

- Interior window treatments of this kind are usually dated to the Timurid and Safavid periods, but few survive, and we cannot rule out production during the Ilkhanid period. We thank Amir-Hossein Karimy for sharing some preliminary impressions of these windows. ↩

- This technique imitated stucco plugs inserted between fired bricks and was also used in Varamin’s congregational mosque and the tomb of Yusof Reza. On the evolution of these techniques from the Seljuk to Ilkhanid periods, see Grbanovic, “Between Tradition and Innovation,” 764–65. For those at Natanz, see McClary and Grbanovic, “On the Origins of the Shrine of ʿAbd al-Samad,” 513–15. ↩

- Blair, The Ilkhanid Shrine Complex at Natanz, 17. ↩

- This contrasts with cases like the tomb of Shaykh ʿAbd al-Samad at Natanz, where luster frieze tiles were installed over older stucco decoration. See McClary and Grbanovic, “On the origins of the Shrine of ʿAbd al-Samad,” 513–15. ↩

- On the various steps of production, including molding, luting of letters, painting, and firing, see Blair, “Art as Text,” 418–20. ↩

- Dieulafoy, La Perse, 149. ↩

- In the case of the ʿAlaoddin tower, there is a thirteen-year gap between the death of ʿAlaoddin Morteza (d. 675/1276) and the completion of his tomb. On this delay, see Blair, “Architecture as a Source,” 224–26. ↩

- Overton and Maleki, “The Emamzadeh Yahya,” 135 and fig. 20. ↩

- It is possible that the door was stolen before Mohammad Hasan Khan Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh’s visit to the site in 1876, as he makes no mention of this door or its important inscription. This omission is notable, given that he was meticulous about documenting the tomb’s inscriptions. See our discussion of his account below. ↩

- For a portrait of ʿAliqoli Mirza Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh signed by Jaʿfar and dated 1292/1875, see the Malek National Library and Museum Institution in Tehran, 1393.01.00017. ↩

- Varamin field notes preserved in the jong of Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh, Majles Library, س.س. ۱۴۵۳, fol. 57a. ↩

- In addition to the original jong, a copy was made shortly thereafter for Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh’s successor Jaʿfar Qoli Khan Nayyer al-Molk (d. 1915). This copy is preserved in the Malek National Library and Museum Institution in Tehran, 1393.04.6151/059. ↩

- His title appears in the newspaper as ‘The Chief of the Printing and Translation Bureau of the Protected Territories of Iran’ (رییس کل دارالطباعه و دارالترجمه ممالک محروسه ایران). ↩

- Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, Rasāʾel, 199–209. On this account, see Nakhaei, Masjed-e jāmeʿ-e Varāmīn, 58–61 and Overton, “Jane Dieulafoy in Varamin.” ↩

- Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, Rasāʾel, 202, 207. See also the annotated aerial views in Nakhaei, Masjed-e jāmeʿ-e Varāmīn, figs. 15–16 and the fixed map in Overton, “Jane Dieulafoy in Varamin,” fig. 4. ↩

- Hedin, Overland to India, vol. 1, 173–74. ↩

- Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, “Akhbār-e dākheleh: Darbār-e homāyūn,” [3]; Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, Rasāʾel, 208. ↩

- Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, Rasāʾel, 208; Overton, “Jane Dieulafoy in Varamin,” 73–74. ↩

- Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, Rasāʾel, 207. ↩

- Ibid., 208. ↩

- Dieulafoy, “La Perse, La Chaldée et La Susiane,” 75. ↩

- Ibid., 74. ↩

- Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, Rasāʾel, 207. ↩

- Sarre, Denkmäler Persischer Baukunst, 59. ↩

- Sarre, “Eine keramische Werkstatt von Kaschan im 13-14 Jahrhundert,” 65. ↩

- For background on the mihrab in Paris, see Overton, “Jane Dieulafoy in Varamin,” 77–80. Additional evidence of Mirza Hasan Mostowfi al-Mamalek’s possession and attempted sale of these tiles in Paris in September 1900 will be presented in Mihrab: Essay. ↩

- Pézard and Bondoux, “Mission de Téhéran,” 59. ↩

- Herzfeld, “Reisebericht,” 234. ↩

- It is difficult to date these tiles based on formal analysis alone, but a range of 1890 to 1910 seems reasonable. At present, no dates have been detected. For a discussion of the stylistic aspects of these tiles, see Makkinejad, Fann-e jamil, 120–1. ↩

- The Emamzadeh Yahya does not seem to have been impacted by the natural disasters, notably floods, that severely damaged the congregational mosque and tower of ʿAlaoddin to the northwest. It therefore seems likely that all of its still standing parts, except for the domed tomb, were deliberately destroyed during its reconfiguration. ↩

- Western Union telegram and letter from Hagop Kevorkian in London to Charles Freer in Detroit, 7 August 1913 and 25 August 1913, Charles Lang Freer Papers, FSA A.01, box 19, folder 28, National Museum of Asian Art Archives. See Overton, “Jane Dieulafoy in Varamin,” 77. ↩

- Martiny, “Albert Gabriel (1883–1972).” ↩

- The 1930 Antiquities Law sparked the registration of historical monuments through the Zand era (1796), and Varamin’s Ilkhanid sites were registered early on in this process. For an English translation of this law, see Nasiri-Moghaddam, “Archaeology and the Iranian National Museum,” 139–43. ↩

- The registration card cites all known literature on the site, including Herzfeld’s 1926 article. ↩

- In 1334 Sh/1955–56, the year before this photograph, the Geographical Organization of the Armed Forces took aerial photographs of this region, but these are much wider views and lack sufficient detail. Aerial photographs of Varamin have not yet been identified in the documentation by Walter Mittelholzer in 1924 or Erich Schmidt in 1935–36. ↩

- The registration document for the Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin is available on Iranarchpedia, the Encyclopedia of Iranian Architectural History (this link is inaccessible in some places). ↩

- Haji-Qassemi (ed.), “[Tehran,] Emamzadeh Yahya,” 3: 35 (English), 168 (Persian). ↩

- On the aluminum screen, see also Bonyad-e Iran-shenasi, Shomārī az boqʿeh-hā, 304, 306. ↩

- In April 2018, this area was being cleared and effectively a construction site. Compare today’s Google satellite view to 2020 (Overton and Maleki, “The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin,” fig. 4). ↩

- Kent-Shmavon Galleries, Illustrated catalogue of very notable collections of the ancient art of Asia and Europe, no. 1240 (pages unnumbered). ↩

Bibliography

Sources: Archives in Iran

- اعتضادالسلطنه، علیقلی میرزا. «شرح حالات امامزاده یحیی». مورخ محرم ۱۲۹۴ ق. در: جنگ نظم و نثر، نسخهی دستنویس در کتابخانهی مجلس شورای اسلامی در تهران، شمارهی ۱۴۵۳سس.، ۵۶ الف – ۵۶ ب.

نامعلوم. [گزارش سفر ورامین به همراه کاروان ناصرالدینشاه قاجار]. مورخ شعبان ۱۲۷۹ق. نوشتهشده به دستور علیقلی میرزا اعتضادالسلطنه. در: جنگ نظم و نثر، نسخهی دستنویس در کتابخانهی مجلس شورای اسلامی در تهران، شمارهی ۱۴۵۳سس.، ۵۷ الف.

The two texts above are combined as:

“Sharh-e halat-e Emamzadeh Yahya” (Biography of Emamzadeh Yahya), dated Moharram 1294/ January 1877 (56a–56b) and Varamin field notes from the royal visit in Shaʿban 1279 AH/ January 1863 (57a), preserved in a jong compiled for ʿAliqoli Mirza Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh. The Library, Museum and Document Center of the Islamic Parliament of Iran (Ketabkhaneh, Muzeh va Markaz-e Asnad-e Majles-e Shora-ye Eslami), Tehran, accession number 1453/س.س. ۱۴۵۳, fols. 56a–57a.

- اعتمادالسلطنه، محمدحسن خان. «اخبار داخله: دربار همایون.» . در: ایران، شمارهی ۳۰۵ (۷ ذیالحجه ۱۲۹۳ق.): ۱-۳. سازمان اسناد و کتابخانه ملی ایران، ۱۰۱۴۵۷۴.

Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, Mohammad Hasan Khan. “Akhbār-e dākheleh: Darbār-e homāyūn.” Iran 305 (24 December 1876): 1–3. National Library and Archives of Iran, Tehran, 1014574.

- «پرونده ثبت امامزاده یحیی ورامین.» تهیه توسط سازمان حفظ بناهای تاریخی، ۹ مرداد ۱۳۱۲ش. بازبینی و اضافات توسط سازمان میراث فرهنگی کشور، ۱۳۷۵ش. مرکز اسناد و مدارک سازمان میراث فرهنگی کشور، شمارهی ۱۹۹. دستیابی از وبگاه دانشنامهی تاریخ معماری و شهرسازی ایران (تاریخ دسترسی: بهمن ۱۴۰۲ش.).

“Registration Document of the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin.” Prepared by the Organization for the Preservation of Historical Buildings, 9 Mordad 1312 Sh/31 July 1933. Revised and supplemented by the Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization in 1375 Sh/1996. Center for Documents and Records, Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran, no. 199. Available online in the Encyclopedia of Iranian Architectural History, Iranarchpedia (date of access: February 2024).

- «گزارش نوبت دوم عملیات انجام شده و پیشرفت مرمت بنای تاریخی امامزاده یحیی ورامین.» . تهیه توسط دفتر فنی تهران به سرپرستی محمدحسن محبعلی. ۱۳۶۲ش. مرکز اسناد و مدارک سازمان میراث فرهنگی کشور، ۱۷۹۷.

“Second Phase Report on Completed Operations and Restoration Progress of the Historic Building of Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin.” Prepared by the Tehran Technical Office under the supervision of Mohammad Hasan Moheb-Ali, 1362 Sh/1983–84. Center for Documents and Records, Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran, no. 1797.

- «گزارش عملیات انجام شده و پیشرفت مرمت بنای تاریخی امامزاده یحیی ورامین.» تهیه توسط دفتر فنی تهران به سرپرستی محمدحسن محبعلی. ۱۳۶۳ش. مرکز اسناد و مدارک سازمان میراث فرهنگی کشور، ۱۸۰۱.

“Report on Completed Operations and Restoration Progress of the Historic Building of Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin.” Prepared by the Tehran Technical Office under the supervision of Mohammad Hasan Moheb-Ali, 1363 Sh/1984–85. Center for Documents and Records, Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran, no. 1801.

- سازمان نقشهبرداری کشور

National Cartographic Center of Iran, Tehran

- مرکز اسناد و تحقیقات دانشکده معماری و شهرسازی، دانشگاه شهید بهشتی، تهران

The Center for Documentation and Research of the Faculty of Architecture and Urban Planning, Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran

- آرشیو یکی از ساکنان محلهی کهنهگل، ورامین Archive of a resident of Kohneh Gel, Varamin

Sources: Persian

- ابوالفرج اصفهانی، علی بن الحسین. مقاتل الطالبیّین. تحقیق السید احمد صقر. بیروت: مؤسسة الاعلمی للمطبوعات، ۱۹۸۷. [Abolfaraj Esfahani, Maqātil al-ṭālibīyyīn] [Internet Archive]

- اعتمادالسلطنه، محمدحسن خان. رسائل اعتمادالسلطنه. تدوین میرهاشم محدث. تهران: اطلاعات، ۱۳۹۱ش. [Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, Rasāʾel] [WorldCat] [Lib.ir]

- ایرنا. «بقعه امامزاده یحیی (ع) ورامین جاذبهای تاریخی، میراثی گرانقدر از گذشتگان.» ۲۹ آذر ۱۳۹۹ش. [IRNA, “Boqʿeh-ye Emāmzādeh Yahyā Varāmīn jāzebeh-ī tārīkhī”] [IRNA]

- بنیاد ایرانشناسی. شماری از بقعهها، مرقدها و مزارهای استان تهران و البرز. ج۲: شهرستانهای شهریار، فیروزکوه، کرج، نظرآباد و ورامین. طرح، بررسی و تدوین حسن حبیبی. تهران: بنیاد ایرانشناسی، ۱۳۸۹ش. [Bonyad-e Iran-shenasi, Shomārī az boqʿeh-hā] [WorldCat] [Lib.ir]

- قوچانی، عبدالله. «بررسی کتیبه آرامگاه علاءالدین.» در: اثر، شمارههای ۱۵-۱۶ (۱۳۶۷ش.): ۵۹-۷۱. [Ghouchani, “Barrasī-ye katībeh-ye ārāmgāh-e ʿAlā al-Dīn”]

- مکینژاد، مهدی. فن جمیل: زندگی و آثار استاد علیمحمد اصفهانی (کاشیساز و نقاش دوره قاجار). تهران: متن، ۱۴۰۰ش. [Makkinejad, Fann-e jamīl] [WorldCat] [Lib.ir]

- ناصرالدین شاه قاجار. گزارش شکارهای ناصرالدین شاه قاجار ۱۲۸۱-۱۲۷۹ ه.ق. تصحیح و پژوهش فاطمه قاضیها. تهران: سازمان اسناد و کتابخانه ملی، ۱۳۹۰ش. [Naser al-Din Shah, Gozāresh-e shekārhā] [WorldCat] [Lib.ir]

- نخعی، حسین. مسجد جامع ورامین: بازشناسی روند شکلگیری و سیر تحول. تهران: دانشگاه شهید بهشتی و روزنه، ۱۳۹۷ش. [Nakhaei, Masjed-e jāmeʿ-e Varāmīn] [WorldCat] [Academia]

- همشهری آنلاین. «امامزادهای شبیه موزه.» ۳۰ اردیبهشت ۱۴۰۲ ش. [Hamshahri Online, “Emāmzādeh-ī shabīh-e muzeh”] [Hamshahri Online]

- مصطفوی، محمدتقی. «خانواده هنرمند.» اطّلاعات ماهانه ۹۰ (شهریور ۱۳۳۴ش.): ۳۰-۳۱ و ۵۷. [Mostafavi, “Khānevādeh-ye honarmand”]

Sources: Archives in Europe and North America

- Albums Dieulafoy, Bibliothèque de l’Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art, Paris, NUM 4 PHOT 018 [INHA]

- Charles Lang Freer Papers, National Museum of Asian Art Archives, Washington, D.C., FSA A.01 [NMAA]

- André et Yedda Godard Archives, Département des arts de l’Islam, musée du Louvre, Paris

- Ernst Herzfeld Papers, National Museum of Asian Art Archives, Washington, D.C., FSA.A.06 [NMAA]

- Donald Wilber Archive, Visual Resources Center, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Sources: English, French, German, and Persian–English translation

- Amanat, Abbas. s.v. “Eʿtemād-al-Salṭana, Moḥammad-Ḥasan Khan Moqaddam Marāḡaʾī.” Encylopaedia Iranica, December 15, 1998 (updated January 19, 2012), https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/etemad-al-saltana.

- Amini, Mohammad. “Oral History with Mohammad Amini: Sacred Landscapes and Moharram Rituals in Varamin.” Interviewed by Jabbar Rahmani and Maryam Rafeienezhad, edited by Hamid Abhari. Film in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton, 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online. [this website: Persian, English translation]

- Blair, Sheila S. The Ilkhanid Shrine Complex at Natanz, Iran. Cambridge: Harvard University, 1986. [WorldCat]

- Blair, Sheila S. “Art as Text: The Luster Mihrab in the Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art.” In No Tapping around Philology: A Festschrift in Honor of Wheeler McIntosh Thackston Jr.’s 70th Birthday, edited by Alireza Korangy and Daniel J. Sheffield, 407–36. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2014. [WorldCat] [Academia]

- Blair, Sheila S. “Architecture as a Source for Local History in the Mongol Period: The Example of Warāmīn.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 26, 1–2 (January 2016): 215–28. [Brill]

- Chughtai, Abdullah. “Lustred Tiles from Samarra in the Ashmolean Museum.” Islamic Culture 7, 3 (July 1933): 472–76. [Noormags]

- Combe, Étienne, Jean Sauvaget, and Gaston Wiet, eds. Répertoire chronologique d’épigraphie arabe, vol. 13. Cairo: Impr. de l’Institut français d'archéologie orientale, 1944. [BnF Gallica]

- Dieulafoy, Jane. “La Perse, La Chaldée et La Susiane,” Le tour du monde: Nouveau journal des voyages (January 1883): 1–80. [BnF Gallica]

- Dieulafoy, Jane. La Perse, la Chaldée et la Susiane: relation de voyage contenant 336 gravures sur bois d’après les photographies de l’auteur et deux cortes. Paris: Librairie Hachette et Cie, 1887. [Internet Archive]

- Dust-Ali Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek. The Artist and the Shah: Memoirs of Life at the Persian Court. Translated, edited, and annotated by Manoutchehr M. Eskandari-Qajar. Odenton: Mage Publishers, 2022. [WorldCat]

- Grbanovic, Ana Marija. “Between Tradition and Innovation: The Art of Ilkhanid Stucco Revetments in Iran.” In Proceedings of the 12th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, vol. 2, edited by Nicolò Marchetti et al., 763–78. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2023. [Harrassowitz Verlag]

- Haji-Qassemi, Kambiz (ed.). Ganjnameh: Cyclopaedia of Iranian Islamic Architecture, vol. 3, Spiritual Buildings of Tehran. Tehran: Shahid Beheshti University Press, 1998. [WorldCat]

- Haji-Qassemi, Kambiz (ed.). Ganjnameh: Cyclopaedia of Iranian Islamic Architecture, vol. 13, Emamzadehs and Mausoleums (Part III). Tehran: Shahid Beheshti University Press, 2010. [WorldCat]

- Hedin, Sven. Eine Routenaufnahme durch Ostpersien, vol. 1. Stockholm: Generalstabens Litografiska Anstalt, 1918. [Digital Silk Road]

- Hedin, Sven. Overland to India: with 308 illustrations from photographs, watercolour sketches, and drawings by the author and 2 maps; in two volumes. London: Macmillan, 1910. [Digital Silk Road]

- Herzfeld, Ernst. “Reisebericht.” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenlandischen Gesellschaft 80 (1926): 225–84. [JSTOR]

- Kent-Shmavon Galleries. Illustrated catalogue of very notable collections of the ancient art of Asia and Europe; Notable collections of the Kent-Shmavon galleries of ancient art objects of Asia and Europe. New York: Kent-Shmavon Galleries, 1915. [Internet Archive]

- Khamehyar, Ahmad. “An Introduction to the Origins and Construction of Emamzadehs in Iran, with an Emphasis on the Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin.” Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton, 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online. [this website: Persian, English translation]

- Martiny, Victor-Gaston. “Albert Gabriel (1883-1972).” Bulletin de la Classe des Beaux-Arts 55 (1973): 90–94. [Persée]

- McClary, Richard, and Ana Marija Grbanovic. “On the Origins of the Shrine of ‘Abd al-Samad in Natanz: The Case for a Revised Chronology.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 32, 3 (2022): 501–34. [Cambridge Core]

- Nasiri-Moghaddam, Nader. “Archaeology and the Iranian National Museum: Qajar and early Pahlavi cultural policies.” In Culture and Cultural Politics Under Reza Shah: The Pahlavi State, New Bourgeoisie and the Creation of a Modern Society in Iran, edited by Bianca Devos, Christoph Werner, 121–48. London: Routledge, 2013. [Taylor & Francis Group]

- Overton, Keelan. “Framing, Performing, Forgetting: “The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin.” Platform, September 12, 2022, https://www.platformspace.net/home/framing-performing-forgetting-the-emamzadeh-yahya-at-varamin.

- Overton, Keelan “Jane Dieulafoy in Varamin: The Emamzadeh Yahya through a Nineteenth-Century Lens.” Getty Research Journal 19 (spring 2024): 61–95. [Getty]

- Overton, Keelan, and Kimia Maleki. “The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: A Present History of a Living Shrine, 2018–20.” Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World 1, 1–2 (2020): 120–49. [Brill]

- Pézard, Georges, and Georges Bondoux. “Mission de Téhéran.” In M.C. Soutzo et al. Délégation en Perse: Mémoires. Tome XII, Recherches archéologiques: Quatrieme série, 51–64. Paris: Ernst Leroux, 1911. [Internet Archive]

- Sarre, Friedrich. Denkmäler persischer Baukunst. Berlin: Wasmuth, 1910. [Heidelberg University]

- Sarre, Friedrich. “Eine keramische Werkstatt von Kaschan im 13.–14. Jahrhundert.” Istanbuler Mitteilungen 3 (1935): 57–69. [WorldCat]

- Shahidi Marnani, Nazanin. “If some day a noble soul reads this... Documenting the yadegari of the Tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin.” Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton, 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online. [this website: Persian, English translation]

- Watson, Oliver. Persian Luster Ware. London: Faber and Faber, 1985. [Academia]

- Wilber, Donald Newton. The Architecture of Islamic Iran: the Il Khānid Period. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1955. [WorldCat]