The Sacred Encounter: Pious Visitation and Devotional Practices in Twelver Shiʿism

Sepideh Parsapajouh

In this essay, I share some anthropological findings concerning the practice of ziyarat (Ar. ziyara), or the ‘pious visit,’ in Twelver Shiʿism.1 The ultimate objective of the pious visit is the believer’s encounter and communion with a male or female saint, generally in the place preserving their bodily remains. Three essential elements foster this conjunction between the human and divine:

- a certain spiritual state and set of beliefs

- a material support, generally the tomb preserving corporal remains

- a set of ritual practices conducted in these places

I concentrate here on the third axis: the practices of the believer or pilgrim (zaʾer).2 To the outside observer, ritual practices can constitute a set of more or less uniform facts, but they are in fact very diverse and nuanced when observed closely. They are informed not only by the venerated figure and their burial site but also the ethnic, cultural, and social affiliations of the pilgrim. What follows proposes some general observations, illustrated with photographs of some of Iran’s largest and most visited ‘material supports’ or tombs. Many of the rituals described are integral to any Shiʿi holy tomb, including smaller sites like the Emamzadeh Yahya, thus underscoring their power, durability, and ubiquity.

Saints and Holy Places

Before discussing ritual practices, let us first briefly consider the saints in question. The sacred figures of Twelver Shiʿism can be divided into a five-part typology.3 The most important are the Fourteen Immaculate Ones: the Prophet Mohammad (d. 632); his daughter Fatima, known as Zahra (d. 632); his cousin and son-in-law ʿAli (d. 661), the first Emam and his immediate successor; his grandsons Hasan (d. 669) and Hosayn (d. 680), children of Fatima and ʿAli and the second and third Emams; and the ensuing nine Emams. The male and female descendants of the Twelve Emams, known as emamzadeh, constitute the next and largest group. There are officially 10,616 emamzadehs in Iran buried in 8,051 shrines identified by the same term (for example, Emamzadeh Yahya).4 The final three categories include biblical prophets such as Nuh (Noah), Hud (Eber), and Daniyal (Daniel); martyrs like Maytham al-Tammar (d. 680), Kumayl b. Ziyad (d. 702), and Muslim b. Aqil (d. 680); and wise men (scholars, jurists, theologians, philosophers, mystics) such as Ibn Babawayh (d. 991), Shaykh al-Mufid (d. 1022), and ʿAli Qazi Tabatabaʾi (d. 1947).

The most important place associated with the sacred figure is their tomb. The most important tombs are those of the Twelve Emams, and the majority available to visit are located in present-day Iraq within large shrine complexes. Karbala is the holy place par excellence for Shiʿi Muslims, and the burial place of Emam Hosayn (map) (fig. 1). 300 meters to the east is the shrine of Abol-Fazl al-ʿAbbas, Hosayn’s half-brother (figs. 1–2).

Only the eighth Emam, known as Emam Reza (d. 818), is buried in Iran, and his shrine at Mashhad (Haram-e Emam Reza; map) is the holiest site in the country (figs. 3–4). This immense haram follows a radial plan around the Emam’s tomb, marked by a gold dome. It includes historical architecture (mosques, madrasas, tombs, ayvans, fountains) patronized over the centuries as well as more recent administrative and service buildings (libraries, museums, offices, restaurants). A transnational pilgrimage destination, the shrine accommodates over twenty million visitors a year.

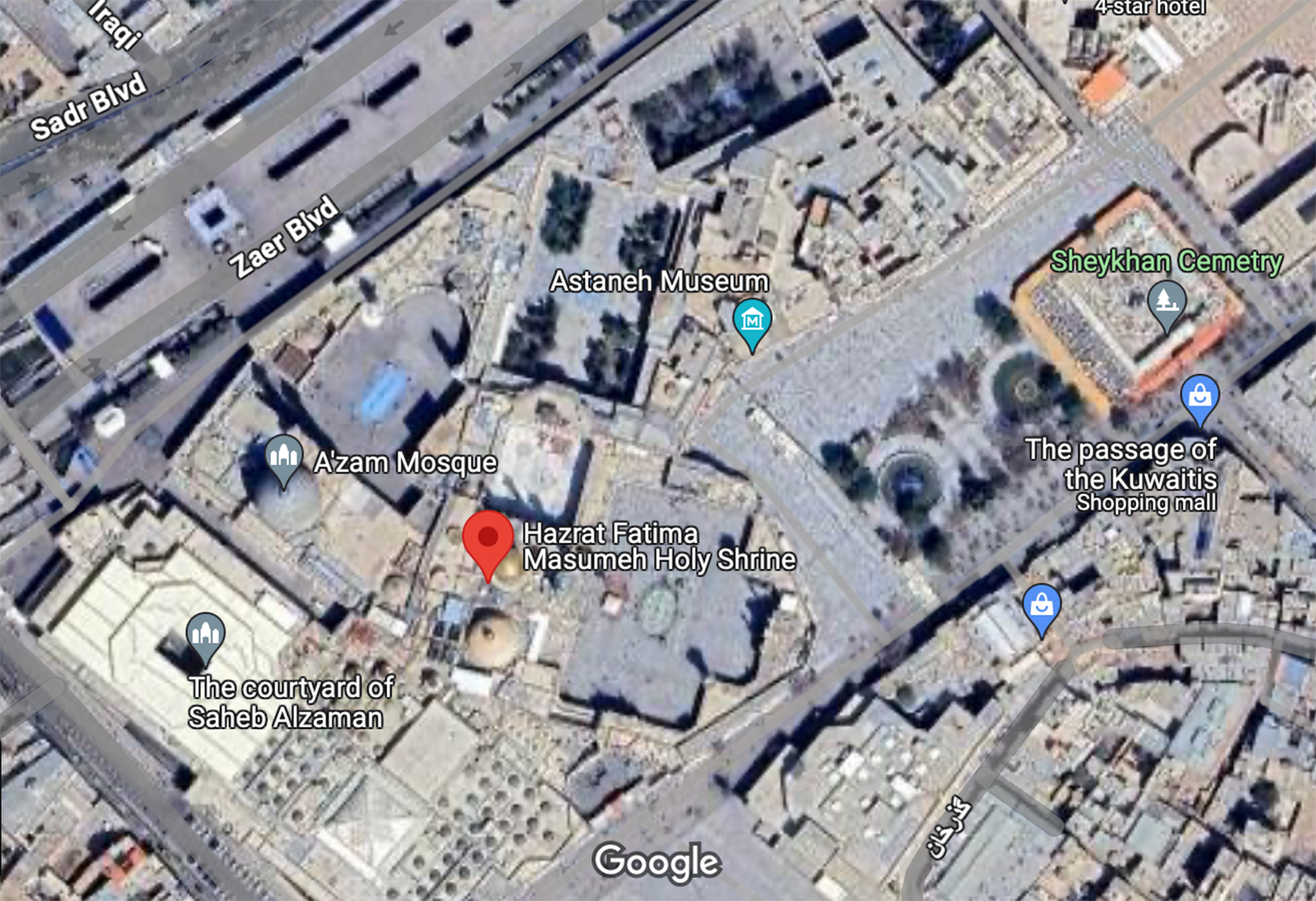

The next most important shrine in Iran is that of Emam Reza’s sister Fatemeh Maʿsumeh (d. 716) at Qom (Haram-e Hazrat-e Maʿsumeh; map) (figs. 5–6). Her tomb is also marked by a gold dome.

Qom is also home to a number of other tombs and cemeteries. The most important is the Sheykhan cemetery (qabrestan-e Sheykhan; map) just east of the shrine (fig. 7).5 This cemetery contains the graves of more than 600 Shiʿi scholars and descendants of the Emams, including Zakariya b. Adam Ashʿari Qommi (d. ca. 819–35), Mirza Mohammad Taheri Qommi (d. 1686), and Mirza Abolqasem Mohammad Shefti Qommi (d. 1815).6

Another major site in the Qom area is the Emam-e Zaman mosque located in Jamkaran (map), a village southeast of Qom (figs. 8–9). It is believed that the Mahdi (Twelfth Emam) ordered the mosque’s construction during a dream and that he is present at the site from time to time. This site underscores an important point in Twelver Shiʿism: among its sacred sites are mythical places believed to have attained sacred status through the spiritual presence or visitation of the Emam, and not through his tomb. Comparable sites are the mosques of Sahla and Kufa in Iraq.

Tehran and its surroundings are home to several hundred tombs considered sacred by believers. The largest complex is the Shrine of ʿAbdol-ʿAzim at Rey (map), a southern suburb of Tehran that is about 60 km north of Varamin (figs. 10–11). It is named after ʿAbd al-ʿAzim al-Hasani (d. 866), a great scholar and transmitter of hadith as well as a descendant of Emam Hasan, meaning he falls in both the descendant (emamzadeh) and wise men typologies.

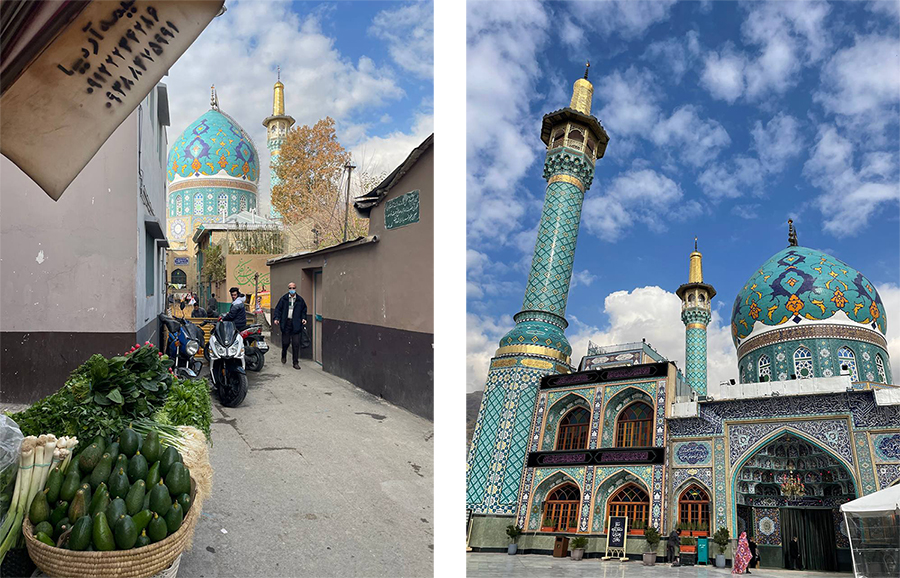

In Tehran proper, many neighborhoods are identified with a popular emamzadeh. One of the most important emamzadehs in the northern neighborhood of Tajrish is the Emamzadeh Saleh (map) (figs. 12–13). It is located in the old traditional bazaar and next to the main mosque.

The atmosphere in larger shrines (for example, Karbala, Mashhad, Qom) can seem disorderly if one does not know the codes.7 One can observe pilgrims of all ages, almost all socio-cultural backgrounds, and many different origins (fig. 14, vid. 1). Sometimes pilgrims are gathered in small groups led by a guide. Depending on the day and time of year and the various religious celebrations, the scene can be very frenetic and crowded.

Video 1. Entrance hall within the Shrine of Emam Hosayn at Karbala. Video (with sound) by Sepideh Parsapajouh, 2024.

The authorities of the shrine are responsible for security and maintenance. The khadems are honorary ‘servants’ responsible for cleaning and monitoring the shrine as well as orienting and informing pilgrims (fig. 15). Some shrines also have permanent or temporary reception points staffed by clerics (akhund) available to answer specific religious or legal questions.

The Tomb Sanctuary

The inside of the saint’s tomb is organized around their cenotaph. The cenotaph is the focus of the pious visit, and all pilgrims hurry toward it. It is often enclosed by a zarih, a pierced screen made of various materials (wood, steel, gilt, silver, gold) and often covered in inscriptions, textiles, and flowers (figs. 16–17).8 The objective of every pilgrim is to reach the zarih, touch and kiss it, and rub pieces of cloth or textiles on it in order to capture the saint’s influx or baraka (blessing).

While leaning against the zarih, the believer might invoke God and the Emam/emamzadeh, confide their sufferings, and implore the saint’s intercession and mediation. The last action is known as hajat, shafaʿat, or tawassol. These concepts are practical in nature and carry nuanced theological meanings, but fundamentally, they involve seeking the intercession of saints to connect the individual visitor with God. Requests for intercession can cover all areas: marriage, maternity, success, healing, or even simply drawing closer to God. Sometimes, as a sign of their request (hajat), pilgrims tie a ribbon or tasbih (prayer beads) to the zarih and make a wish.

Three kinds of small objects are indispensable to pilgrims during their ritual practices. I have already mentioned tasbih, which is used to formulate prayers and sometimes attached to the zarih during the request and wish process. Tasbih are often found near boxes with circular blocks of soil known as mohr (seal) made from soil (torbat) taken from the tomb of Emam Hosayn in Karbala (figs. 18–19). During prostration to the ground in prayer (namaz), the believer rests their forehead against this clay tablet, which might feature a pious inscription or image of Emam Hosayn’s tomb.

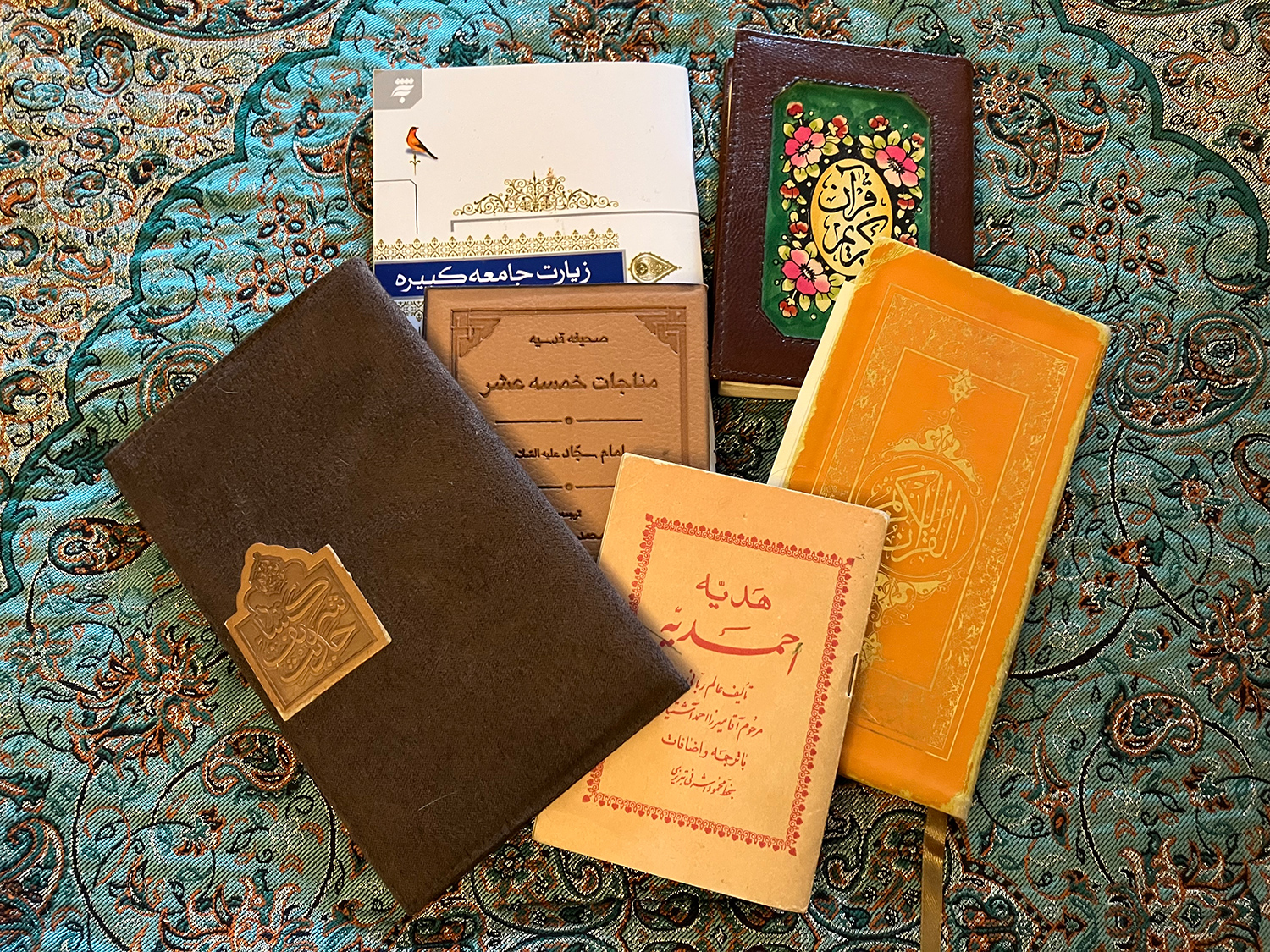

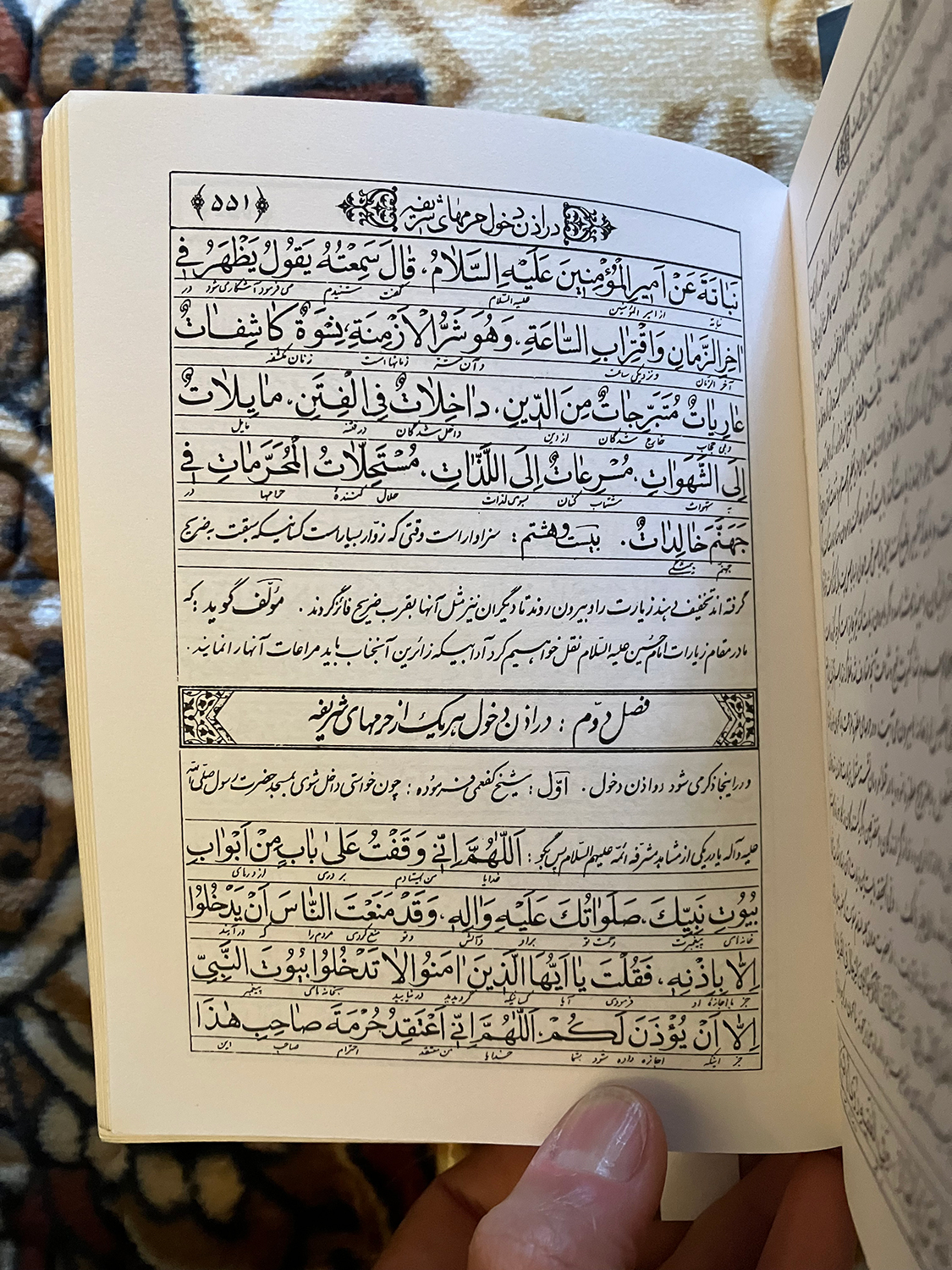

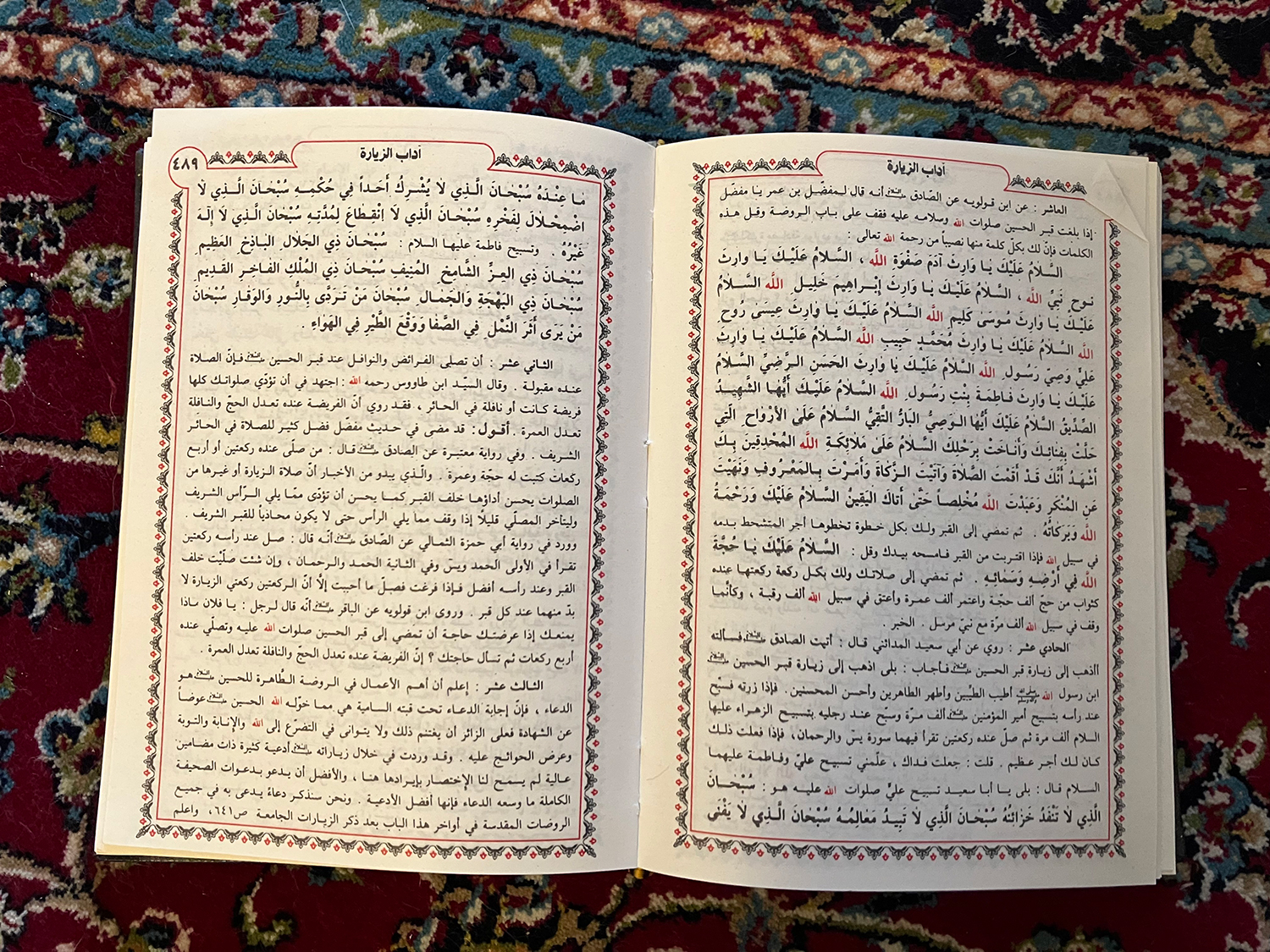

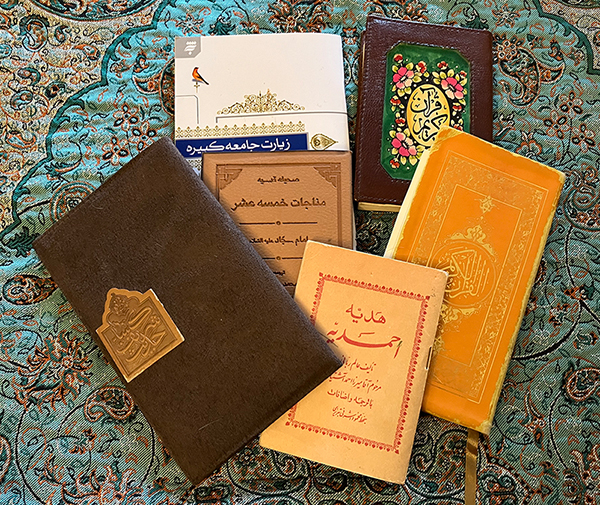

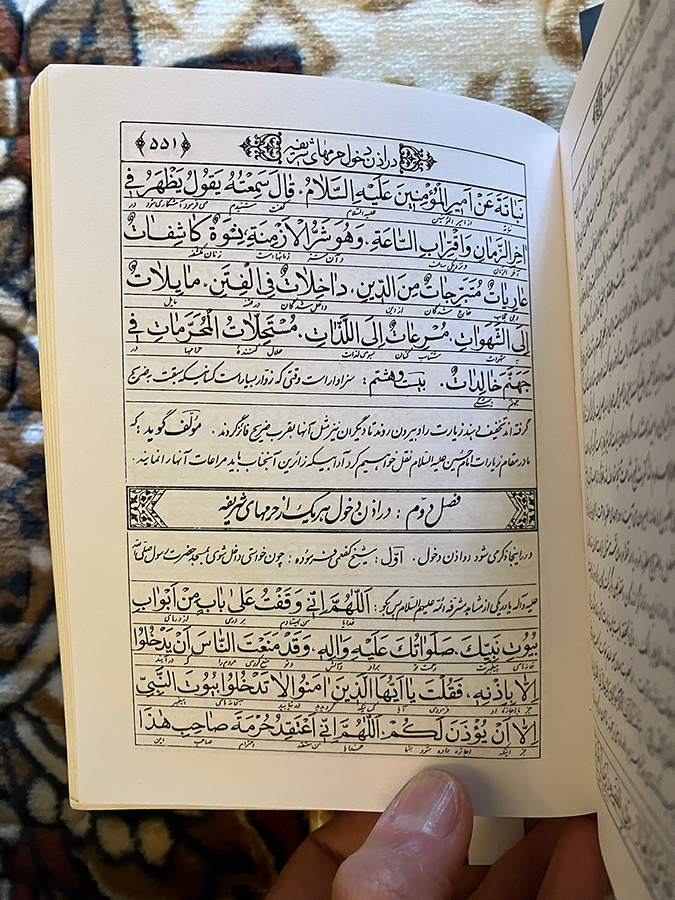

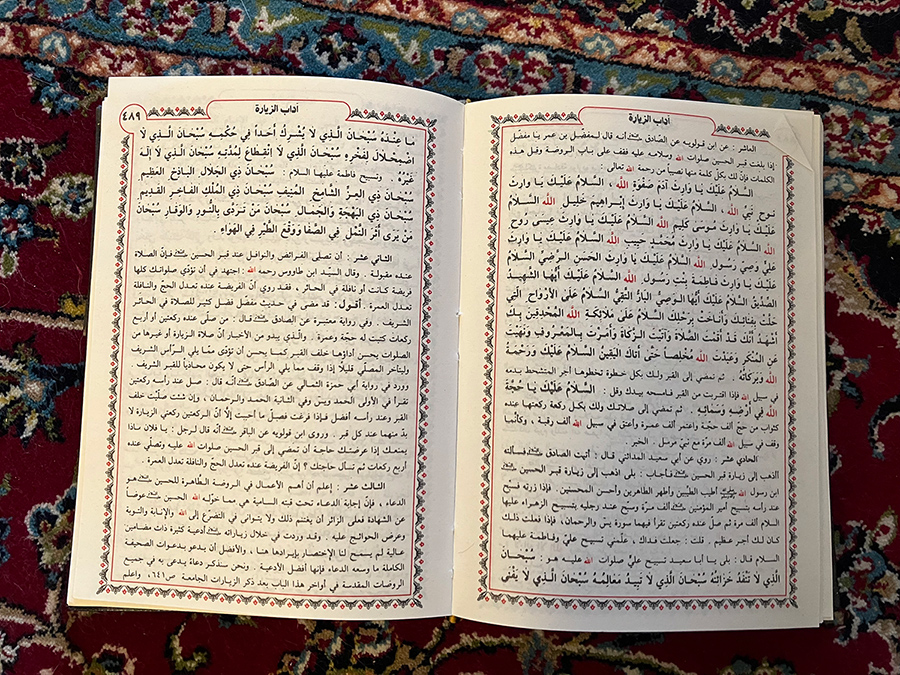

A third category of indispensable objects are booklets and books used and read by the believer while in the tomb. In addition to the Qur’an (al-Quran al-Karim), popular texts include collections of hadith and compilations of salutations, invocations (ways to call upon the saint), prayers, and devotions (fig. 20, vid. 2). One of the most common is the Mafatih al-Jinan (Keys to the Heavens), or parts of this book, compiled by ʿAbbas Qommi (d. 1941). Some of these books contain inscriptions that confirm that they were gifted by pilgrims, for example, “gift from so-and-so by way of thanks” or “for the granting of wishes.” These offerings resemble Christian ex-votos and are often presented as expressions of gratitude but also with the expectation that the giver will benefit from the blessings of the prayer conducted through the reading of the book.

Video 2. Reading Ziyarat-nameh-ye ʿAbbas in the Shrine of ʿAbbas at Karbala. Video (silent) by Sepideh Parsapajouh, 2024.

The buried saint is considered to be constantly on watch and present in the space. One can also believe in the power of angels and ‘inhabitants of the heavens’ (ahl-e behesht) who are the permanent ‘guardians’ and ‘visitors’ of the tomb. Like the zarih, all architectural elements in the tomb—the floor, walls, doors—are considered impregnated with the blessing of the holy person and are caressed and kissed by pilgrims. The baraka of the shrine also accompanies any object or thing in contact with the tomb, including fabrics rubbed on the zarih, mohr used during prayer, and even a photograph taken during the visit. Some of these objects (mohr, tasbih, fabrics) can be purchased at shops near the shrine (figs. 21–22). Each pilgrim comes to the tomb with their personal way of doing ziyarat and leaves with a sort of ‘relic of contact’ that spreads the tomb’s sacredness elsewhere, including in their home and homeland (fig. 23).

The Spiritual Meeting

The spiritual meeting between the pilgrim and the Emam/emamzadeh is a personal matter, and the saint is the only master of the process. The practices are quite free, and no sovereign authority supervises or frames them entirely. Over the course of history, certain ritual practices have become quite similar, entrenched, and common. The explanations offered below are mostly based on fieldwork conducted at Karbala, the most important shrine and an often very crowded tomb (of Emam Hosayn).9 Similar rituals transpire at smaller emamzadehs, including the Emamzadeh Yahya, but it can be assumed that the size and atmosphere of the material support (the tomb) can impact the experience. Another important factor is the inner state of the pilgrim, and we must also differentiate between a/the major pilgrimage of one’s lifetime versus routine visitation to the local emamzadeh.

It is possible to divide the meeting into four general stages:

The first step concerns the pilgrim’s preparatory practices. These preparations have two aspects: external/outer (exoteric) and internal/inner (esoteric).

The outer practices consist of

- performing ablutions to enter into a state of ritual purity

- wearing a beautiful clean cloth

- removing one’s shoes (if the pilgrim wishes to do so, as a sign of respect and modesty) and walking slowly towards the tomb sanctuary, praising God

The inner preparations consist of setting an intention (niyyat) and cultivating certain states of mind. These include maʿrefat (awareness of the truth and liveliness of the Emam/emamzadeh), ekhlas (purity and sincerity of the spirit), hozur-e qalb (presence of the heart; in other words, being spiritually available), taslim (submission and obedience, to the Emam/emamzadeh or God), showq (passion, fervor), and khoshuʿ (humility).

The second step is to ask the Emam/emamzadeh for permission to ‘enter the court’ (ezn-e dokhul), in reference to their tomb, also considered their home. This request can be asked in an informal and personal way or by reading a canonical text. The latter is often inscribed on a wall near the entrance or can be read in a booklet (fig. 24).

To give you an idea of this process, I quote the words that a pilgrim at Karbala confided to me:10

“It’s like if you want to enter his house! You have to ask his permission.”

I asked him how one knows if the saint has authorized entrance or not. He replied:

“You will feel his answer through your heart: it is a kind of vibration that you feel in your heart, a strong emotion, which means that the heart has been touched by his presence. It means that he has accepted you.”

In this sense, the request for entrance is the first form of inner and cordial connection with the saint.

Another pilgrim said:

“The sign of permission to enter is tears.” He explained that, according to his spiritual master (in reference to Ayatollah Bahjat, d. 2009), “Crying is not just a physical mechanism, but sometimes a sign of man’s relationship with the higher universe.”

Other people have expressed the same idea. For example:

“What the people say are only superficial rituals. The truth is that it is not up to us to ask permission to enter, because it is he who invites us first. It is never by chance that we go to visit him. If we are here, it is because he called us first, and we only responded to his invitation.”

According to this source, and I have heard this from other pilgrims as well, just being in the city home to the saint’s tomb is already a mark of their grace. This is perhaps why it is not uncommon to be asked by a resident of Karbala:

“What did you do in your life that the Emam [Hosayn] called you here?”

This belief of being “called” to a shrine is widespread among the Twelver Shiʿi, whether the destination is Karbala or any other shrine.

The third step is to enter the tomb. In some shrines, especially larger ones with high numbers of visitors, men and women enter the sanctuary through different doors and stand on different sides of the zarih, separated by a partition (fig. 25).

This stage is marked by the pilgrim’s recitation of ‘entrance greetings.’ These pious formulas are very melodious and elaborate and can be recited from memory, improvised, or read from a canonical text. One example written in classical Arabic is the Ziyarat al-Warith (Visit to the Heir [of the Prophet]), which is attributed to the Emam Jaʿfar and often recited for Emam Hosayn but also for the other martyred Emams (fig. 26).11 The text begins with a common formula praising God, the angels and prophets, the Prophet Mohammad, and the Emams:

“Greetings to you, O proof of God, son of the proof of God; greetings to you, angels of God, pilgrims of the grave of the son of the messenger of God...

Greetings to you, O the slain on the way to God, son of the slain on the way to God,

Hail to thee, O blood of God, son of the blood of God;

Hail to thee, who was the object of pity of the earth and the heavens.”

“Hail to you for whom all creatures, the seven heavens, the seven layers of the earth, all people of paradise and hell (...) wept ...”

“Hail to you, O heir of Nuh (Noah) the prophet of God, Hail to you, O heir of Ebrahim (Abraham) the friend of God, Hail to you, O heir of Musa (Moses) the word of God, Hail to you, O heir of Isa (Jesus) the spirit of God, Hail to you, O heir of Mohammad the friend of God, Hail to you, O heir of ʿAli the ally of God, ...”

The entrance greetings are always accompanied by various gestures of modesty, gratitude, and affection. This includes bowing one’s head, as if facing the holy person, and caressing and kissing the doors, walls, and even the floor with one’s hands and lips. These actions begin as soon as the pilgrim enters the tomb and increase as they approach the zarih, as if approaching the body of the saint. These gestures can be accompanied by crying and weeping.

The climax of the pious visit is reached in the fourth step, when the pilgrim attaches to a small window of the zarih (see my “Transcender les émotions”) (fig. 27). The pilgrim stands at this small window as long as possible (or desired), and the words and gestures of devotion start again, often getting louder. They caress the zarih and entrust the saint with their words, and it is at this moment that the meeting is actualized and emotion is at its peak. The pilgrim might rub tasbih, scarves, books, and shrouds against the zarih, aiming to capture some of its baraka. They might also slip a letter (a secret message) or some money through the holes of the zarih or tie something to its bars, all part of the request and wish process.

Detached from the zarih and filled with emotion, the pilgrim composes themself and finds a place to stand or sit in the tomb. Many continue to cry, perhaps from the emotion of the encounter or the weight of the sufferings confided. The pilgrim lets their emotions and moods flow—hobb (love), boghz (anger), hozn (sadness)—and thought and reason are neutralized or dismissed by the force of emotion. According to the beliefs of the common people and the words of the mystics (orafa), it is through the heart that one reaches an inspired form of consciousness. This is yet another objective of the pious visit.

Finally, after a moment of time contingent on their inner state, the pilgrim gets ready to leave the tomb. They usually leave the chamber backwards, so as not to turn her back to the saint, and with gestures of deference and humility, including kissing the doors and walls and reciting verses and formulas of praise in a very low voice.

***

Ziyarat is a very common practice among Shiʿi believers in Iran, and they are renewed by this practice. When pilgrims come to the shrine, their bond with the saint is strengthened, and after leaving the sanctuary, they seek to maintain this link in their daily life and world. This is accomplished through dreaming, prayer, invocation, and charitable acts, such as the sharing of food (nazri) in their home community. They may also distribute various souvenirs (tasbih, mohr, scarves) blessed by the pious visit among the people around them.

Citation: Sepideh Parsapajouh, “The Sacred Encounter: Pious Visitation and Devotional Practices in Twelver Shiʿism.” Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.

Notes

These findings are based on field observations and interviews conducted between 2014 and 2018 in Iran and Iraq with Persian speakers. Some additional photographs from my recent 2024 visit to Iraq have been included. For a short text written in French after this trip, see “Transcender les émotions.” I thank colleagues and friends for sharing some additional photographs. I also take the occasion to warmly thank my dear colleague Keelan Overton for her enthusiasm and encouragement, and also for her trust and patience.

- On this term, see Amir-Moezzi, « Prière de pélerinage englobant; » Khosronejad, Saints and Their Pilgrims in Iran; and my “The Topography of Corporal Relics.” ↩

- I discuss the material support and sacred geography of Twelver Shiʿism in greater detail in “The Topography of Corporal Relics.” ↩

- Parsapajouh, “The Topography of Corporal Relics,” 202–8. ↩

- Official statistics of the Iranian “Organization of Oqaf and Holy Places” (Sazman-e oqaf va boqa-ye motebarekeh), 2018. ↩

- The term sheykhan is the Persian plural form of the term sheykh (religious man). ↩

- Parsapajouh, « Un cosmopolitisme religieux. La ville de Qom, » 101. ↩

- Some of this text is drawn from my earlier article in French on Karbala. See Parsapajouh, « Pouvoir du lieu. » ↩

- On the zarih recently made in Qom for the tomb of Emam Hosayn at Karbala, see Parsapajouh, « La châsse de l’imam Husayn. » ↩

- Parsapajouh, « Pouvoir du lieu. » ↩

- Parsapajouh, « Pouvoir du lieu, » 376–77. ↩

- This text is the focus of my article « Pouvoir du lieu, médiation du texte, » where it is fully translated and explained (in French). For the Arabic text with an English translation, see “Ziyara Warith.” For another important text, al-Ziyara al-Jamiʿa, see Amir-Moezzi, « Prière de pèlerinage englobant » (also fig. 20 here). ↩

Bibliography

- Amir-Moezzi, Mohammad Ali. « Jamkarân et Mâhân: deux pèlerinages insolites en Iran. » In Lieux d’islam: cultes et cultures de l’Afrique à Java, edited by Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi, 154–67. Paris: Autrement, 1996. [WorldCat]

- Amir-Moezzi, Mohammad Ali. « Prière de pèlerinage englobant (al-Ziyāra al-jāmiʿa) (Aspects de l’imamologie duodécimaine, XVII). » In Raison et quête de la sagesse. Hommage à Christian Jambet, edited by Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi, 31–60. Turnhout: Brepols, 2020. [Brepols]

- Delage, Rémy. « Soufisme et espace urbain. Circulations rituelles dans la localité de Sehwan Sharif. » In Territoires du religieux dans les mondes indiens. Parcourir, mettre en scène, franchir, edited by Mathieu Claveyrolas and Rémy Delage, 149–75. Paris: Éditions EHESS, coll. Purusartha, n°34, 2016. [Open Edition Books]

- Khosronejad, Pedram. Saints and Their Pilgrims in Iran and Neighbouring Countries. Wantage: Sean Kingston Publishing, 2012. [WorldCat]

- Neuve-Église, Amélie. « La marche d’Arbaʿīn en Iran contemporain. Modalités de l’extension d’une temporalité sacrée entre logiques spirituelles et sociopolitiques. » Archives des sciences sociales des religions 193 (2021): 199–231. [Open Edition Journals]

- Overton, Keelan and Kimia Maleki. “The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: A Present History of a Living Shrine, 2018–20.” Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World 1, 1–2 (2020): 120–49. [Brill]

- Parsapajouh, Sepideh. « La châsse de l’imam Husayn. Fabrique et parcours politique d’un objet religieux de Qom à Karbala. » Archives des sciences sociales des religions. La force des objets. Matières à expériences 174 (avril–juin 2016): 49–74. [Open Edition Journals]

- Parsapajouh, Sepideh. “The Topography of Corporal Relics in Twelver Shiʿism. Some Anthropological Reflections on the Places of Ziyāra.” Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World 1, 1–2 (2020): 199–225. [Brill]

- Parsapajouh, Sepideh. « Pouvoir du lieu, médiation du texte: Remarques anthropologiques sur la visite pieuse à Karbalā. » Studia Islamica 116, 2 (2021): 346–92. [Brill]

- Parsapajouh, Sepideh. « Un cosmopolitisme religieux. La ville de Qom au miroir des circulations transnationales. » In Un Moyen-Orient ordinaire. Entre consommations et mobilités, edited by Thierry Boissière and Yoann Morvan, 88–133. Marseille: Diacritiques éditions, 2022. [Open Edition Books]