The Photographs

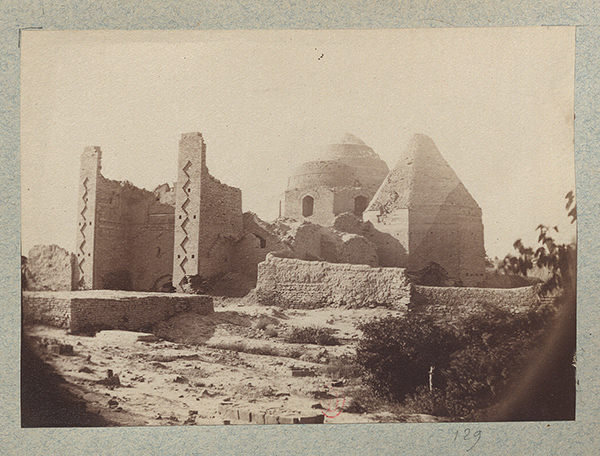

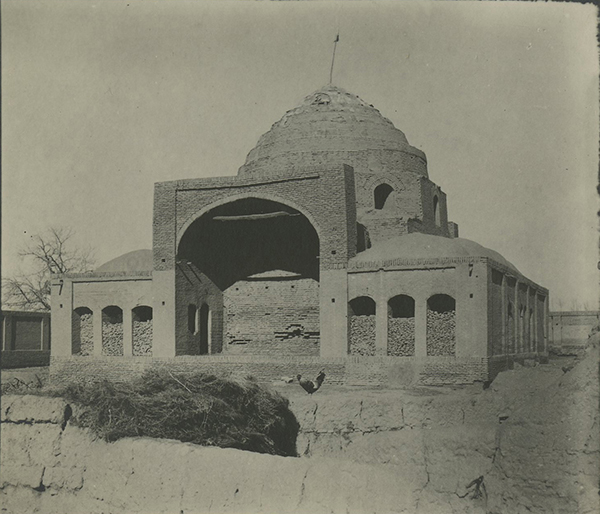

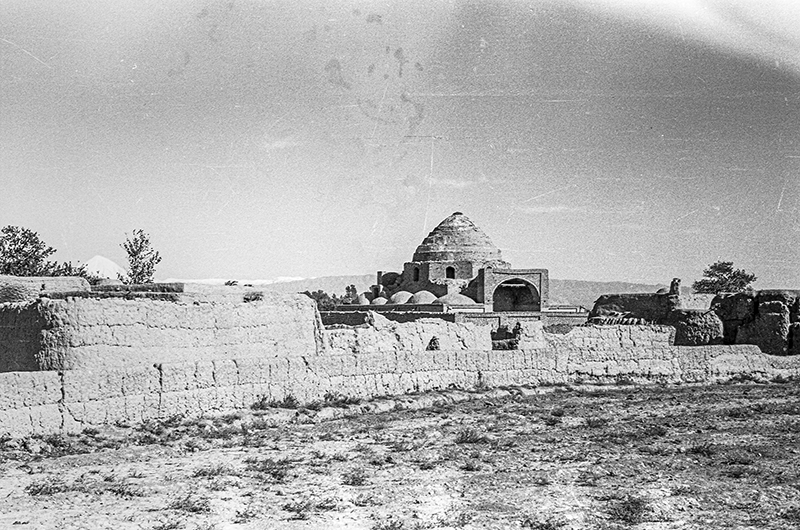

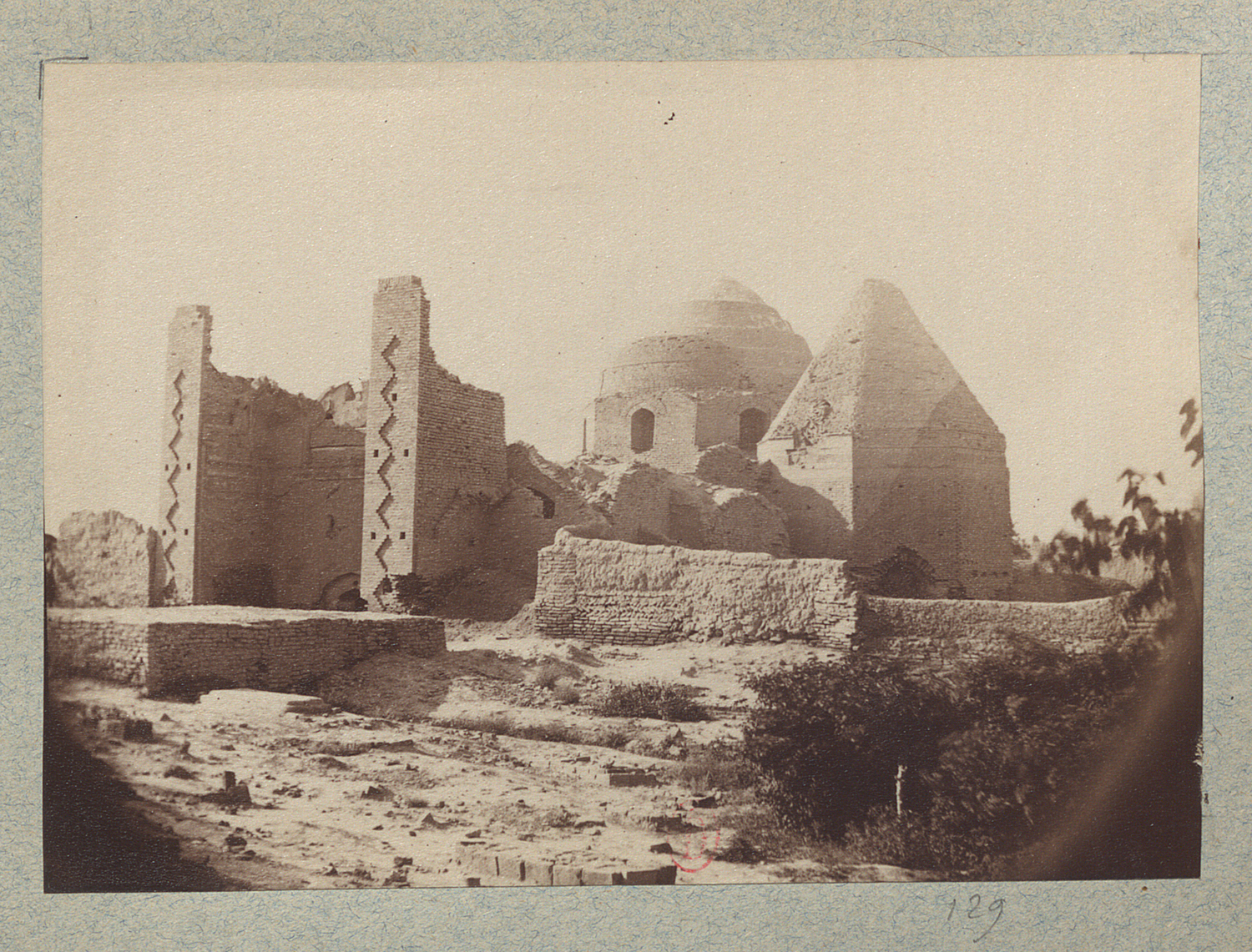

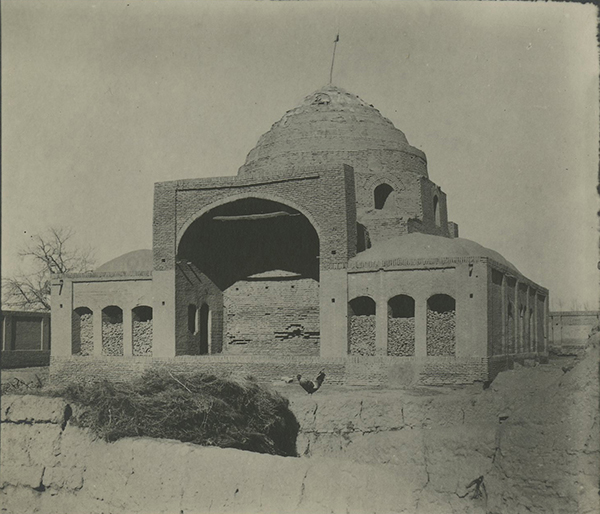

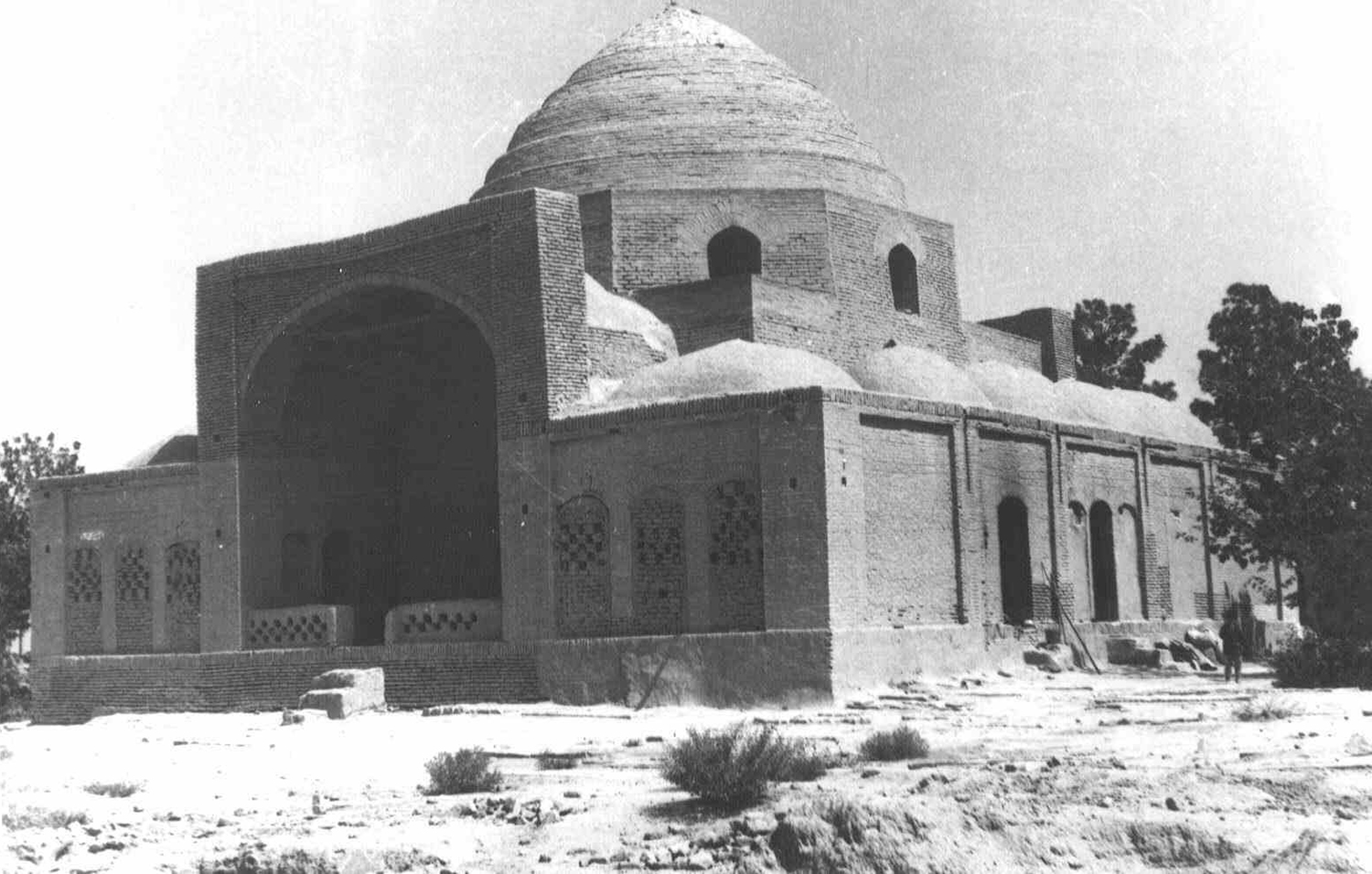

This is the earliest and best known photograph of the Emamzadeh Yahya in its original Ilkhanid-period configuration. The complex consisted of a monumental entrance portal (pishtaq) on the north, an octagonal structure with a conical roof on the west, the tomb of the saint at the rear (south), topped by a stepped dome and fronted by an eyvan, and various spaces and rooms in between. By the time Jane Dieulafoy took this photograph, the arch of the entrance portal had collapsed, but its standing walls attest its immense size and in turn the importance of the complex. A low wall encircles the complex, and a large platform is visible in front. The surrounding terrain is uneven and includes several graves marked by tombstones.

Jane Dieulafoy, June 1881. Print preserved in Perse 1, 4 Phot 18 (1), p. 65, no. 129, Bibliothèque de l’Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art (INHA), Paris.

Related pages:

- Dieulafoy in Photographers

- Photo Album

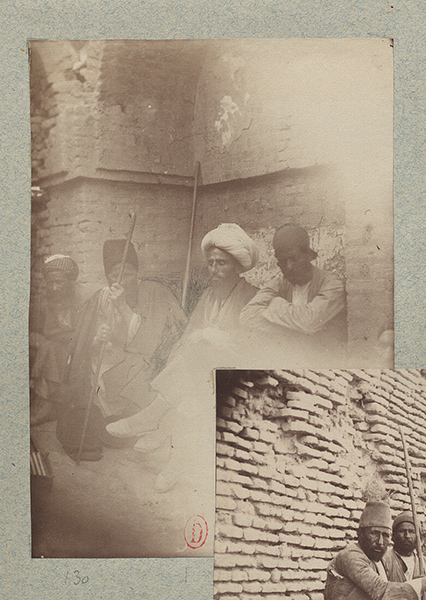

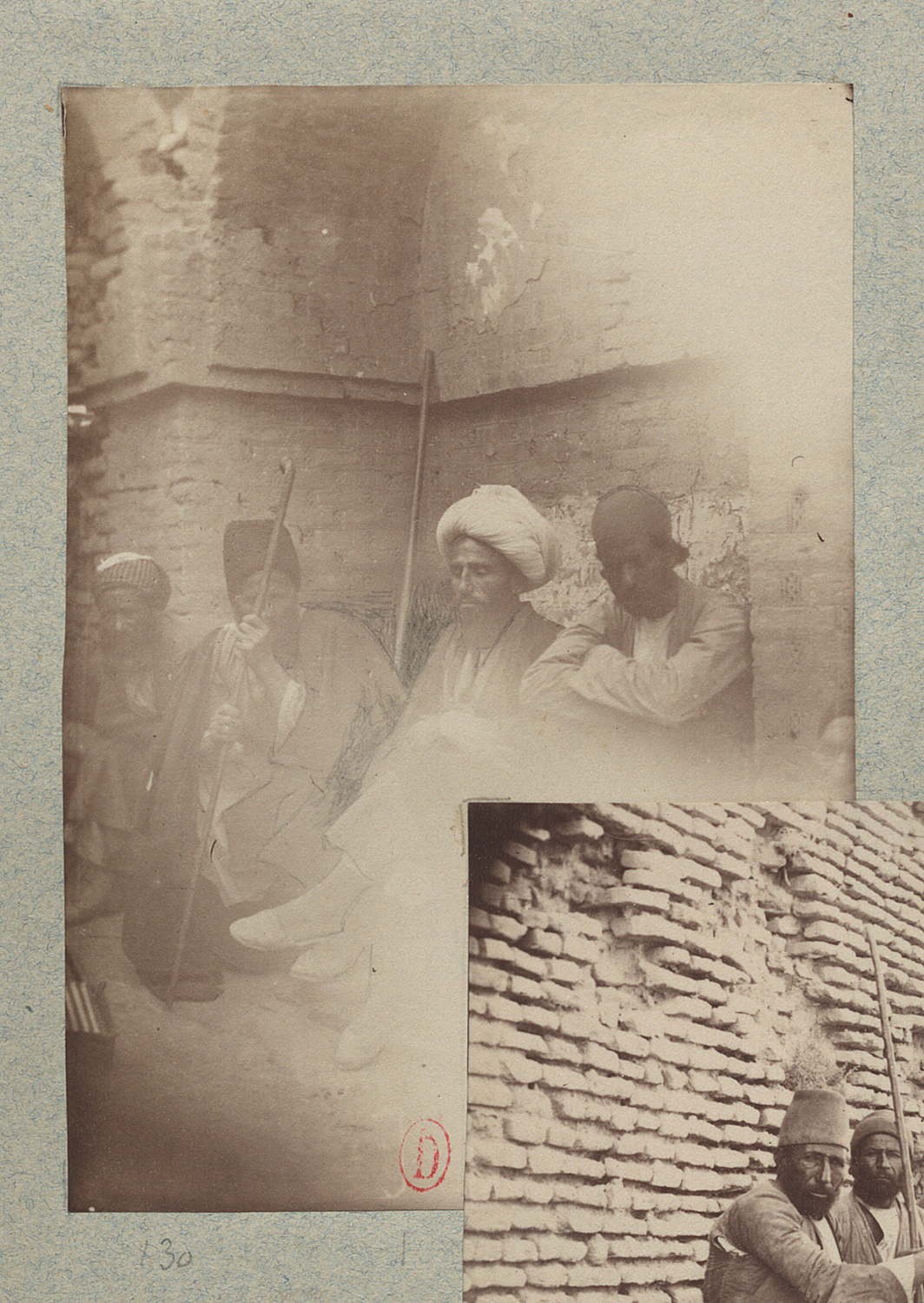

A group of five men sit in an arched niche against a wall of plastered brickwork with stucco plugs. The fifth man is just visible on the far right. One man wears a white turban while another holds a long stick or cane. It is unclear where exactly they are in the complex, but Dieulafoy’s account provides some clues. In her 1883 Le tour article (p. 72) and subsequent 1887 La Perse travelogue (p. 148), she describes the scene as follows: “When we arrived, the guarding of the gate was entrusted to peasants armed with sticks, surrounding a mullah wearing a white turban reserved for priests” (translated from the French). According to Dieulafoy, entrance into religious sanctuaries had been forbidden to Christians due to ongoing thefts, and the Emamzadeh Yahya’s luster tiles were being sold in Tehran “at very high prices.” Despite this “common law,” Dieulafoy and her husband were granted special permission to enter the complex by Naser al-Din Shah (r. 1848–96) and were accompanied by the brother of the head of the village.

Jane Dieulafoy, June 1881. Print preserved in Perse 1, 4 Phot 18 (1), p. 65, no. 130, Bibliothèque de l’Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art (INHA), Paris.

Related pages:

- Dieulafoy in Photographers

- Photo Album

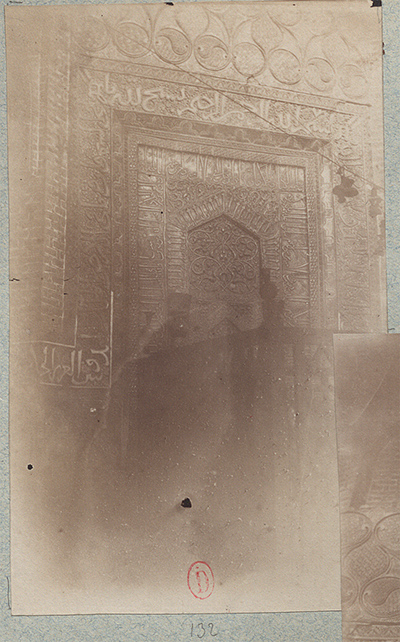

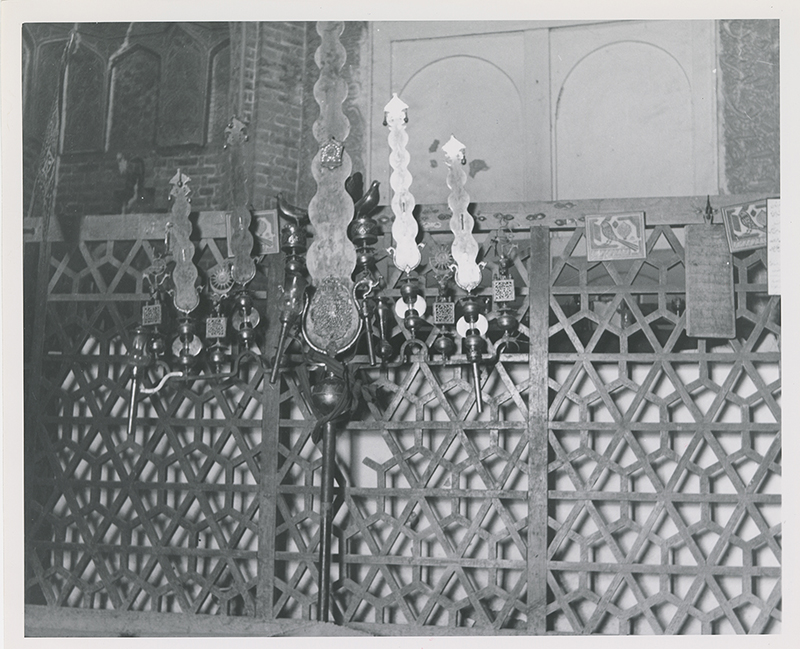

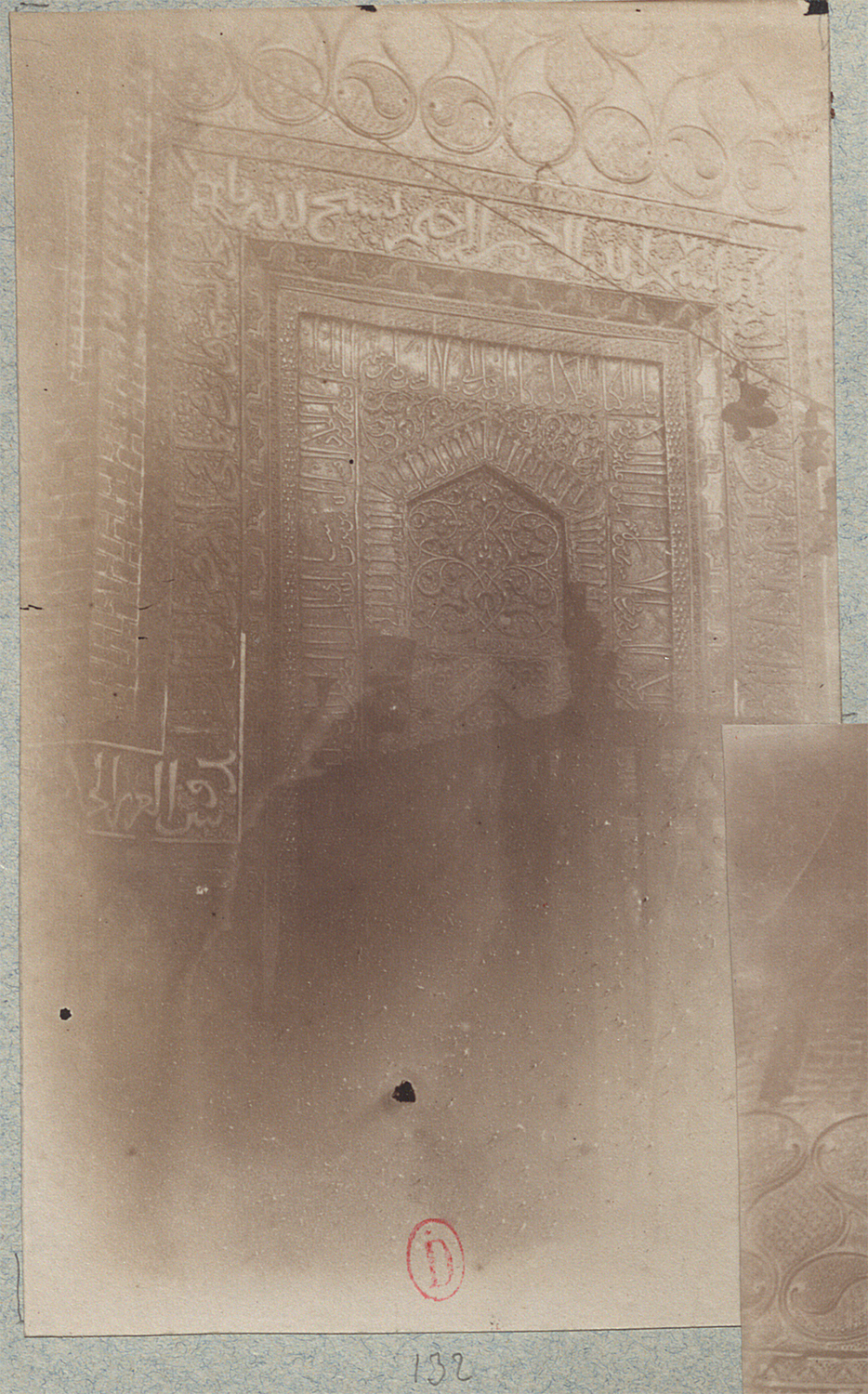

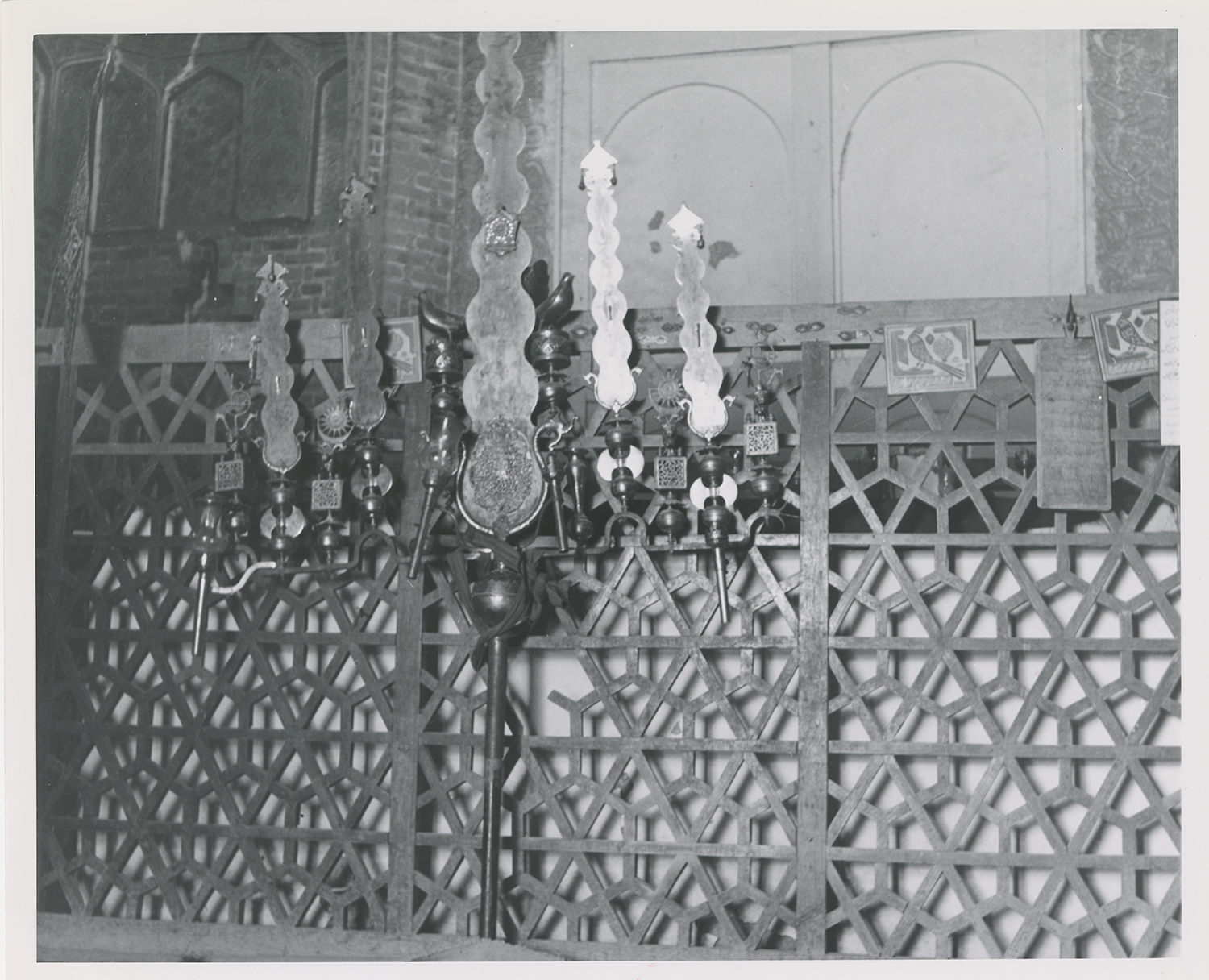

This is the only known image of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s 663/1265 luster tiled mihrab in situ and one of the most important photographs taken inside the tomb. Despite some fading to the small print, it is quite sharp and allow us to re-appreciate the mihrab on its original qibla wall. It was framed not only by the surviving stucco inscription dated Moharram 707 AH/July 1307 but also two smaller borders, one of which was composed of luster half star and cross tiles. During the mihrab’s afterlife on the market (ca. 1900–40), some of its more than seventy tiles were jumbled or lost, and thanks to this photograph, we can appreciate some of its tiles in their original configuration on the wall. Unfortunately, the condition of the print does not allow us to discern much of the dado to the left of the mihrab, but we can note the bright white letters in the stucco inscription, likely indicating a degree of cleaning. In addition to capturing the mihrab, this image also illuminates the most sacred part of the tomb chamber: the tomb of the saint. A wood screen obstructs the lower half of the mihrab and shields the cenotaph of Emamzadeh Yahya. Metal vases with flared rims are mounted to the screen’s visible corners, and a string dangling above suspends several objects, including metal bells. These signs of sanctity underscore an important point: even though areas of the complex were in poor condition (no. 1) the tomb remained a living sacred space.

Jane Dieulafoy, June 1881. Print preserved in Perse 1, 4 Phot 18 (1), p. 65, no. 132, Bibliothèque de l’Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art (INHA), Paris.

Related pages:

- Dieulafoy in Photographers

- Photo Album

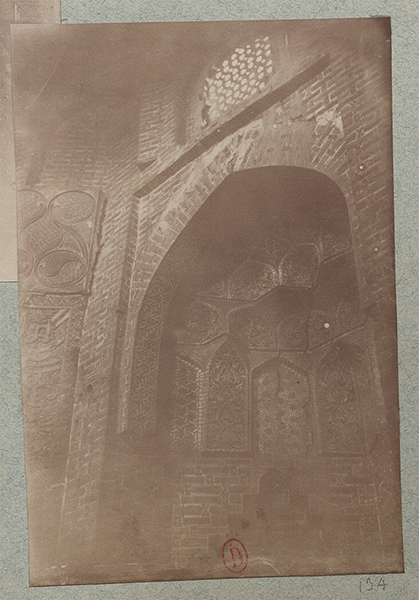

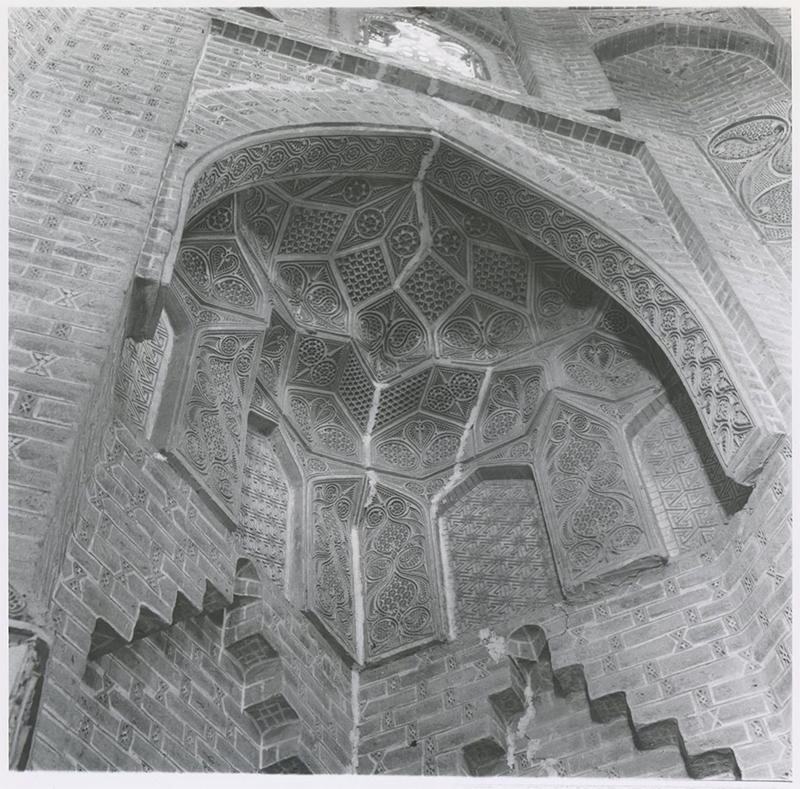

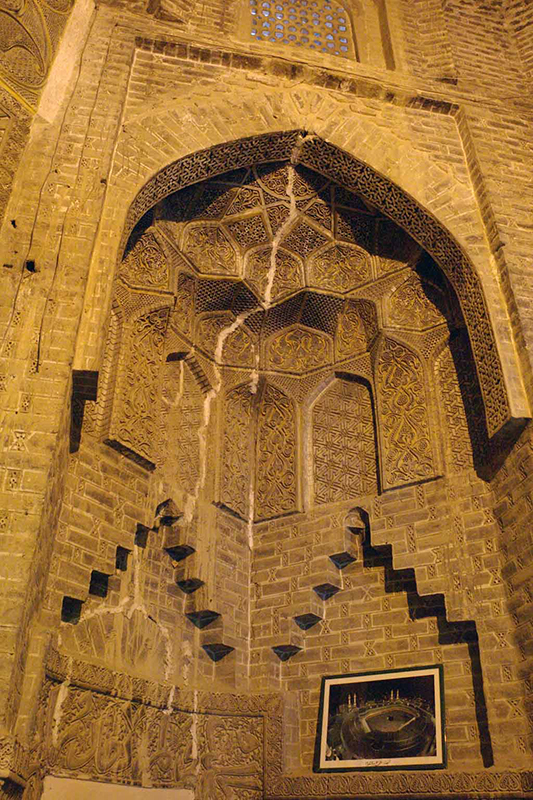

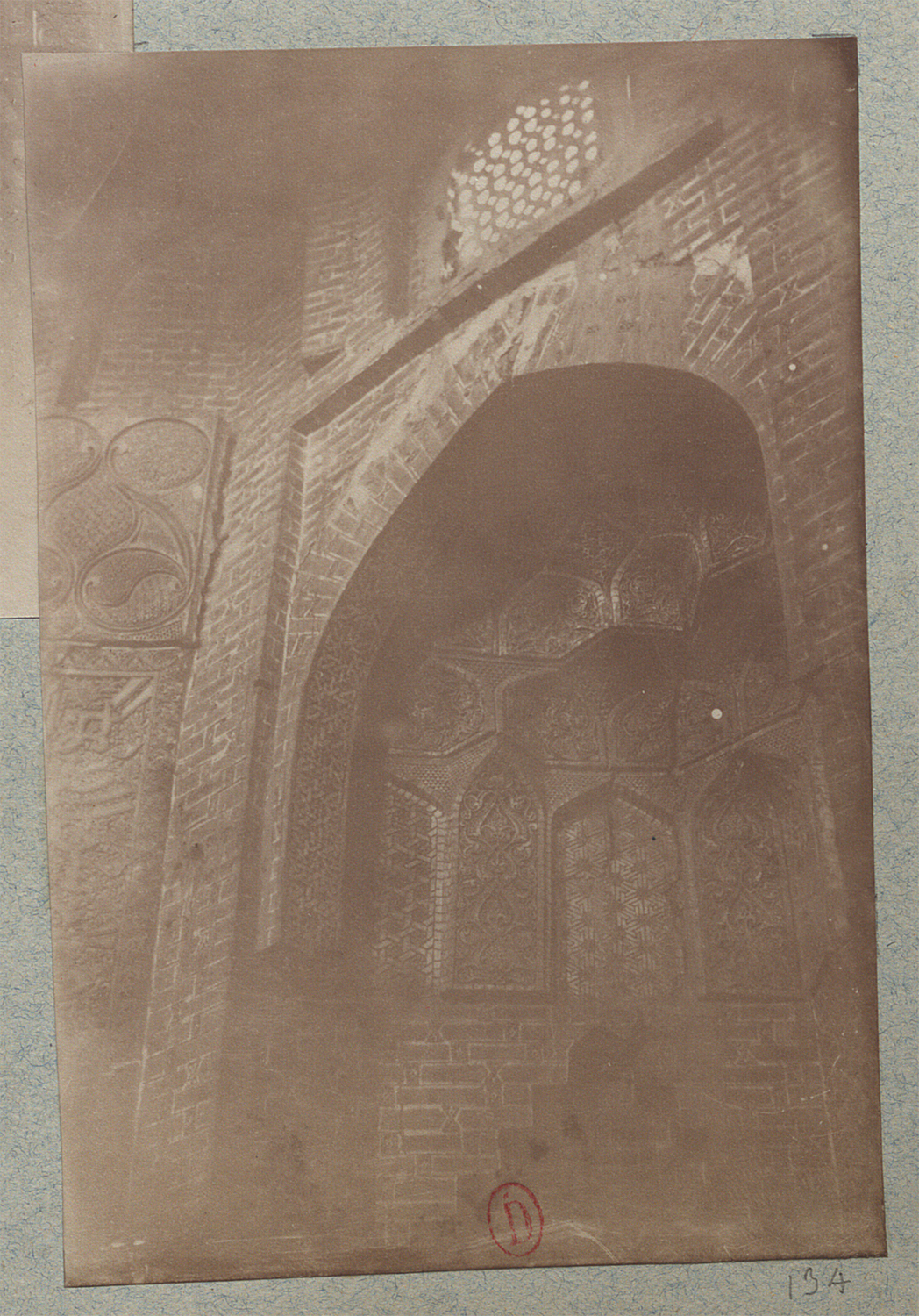

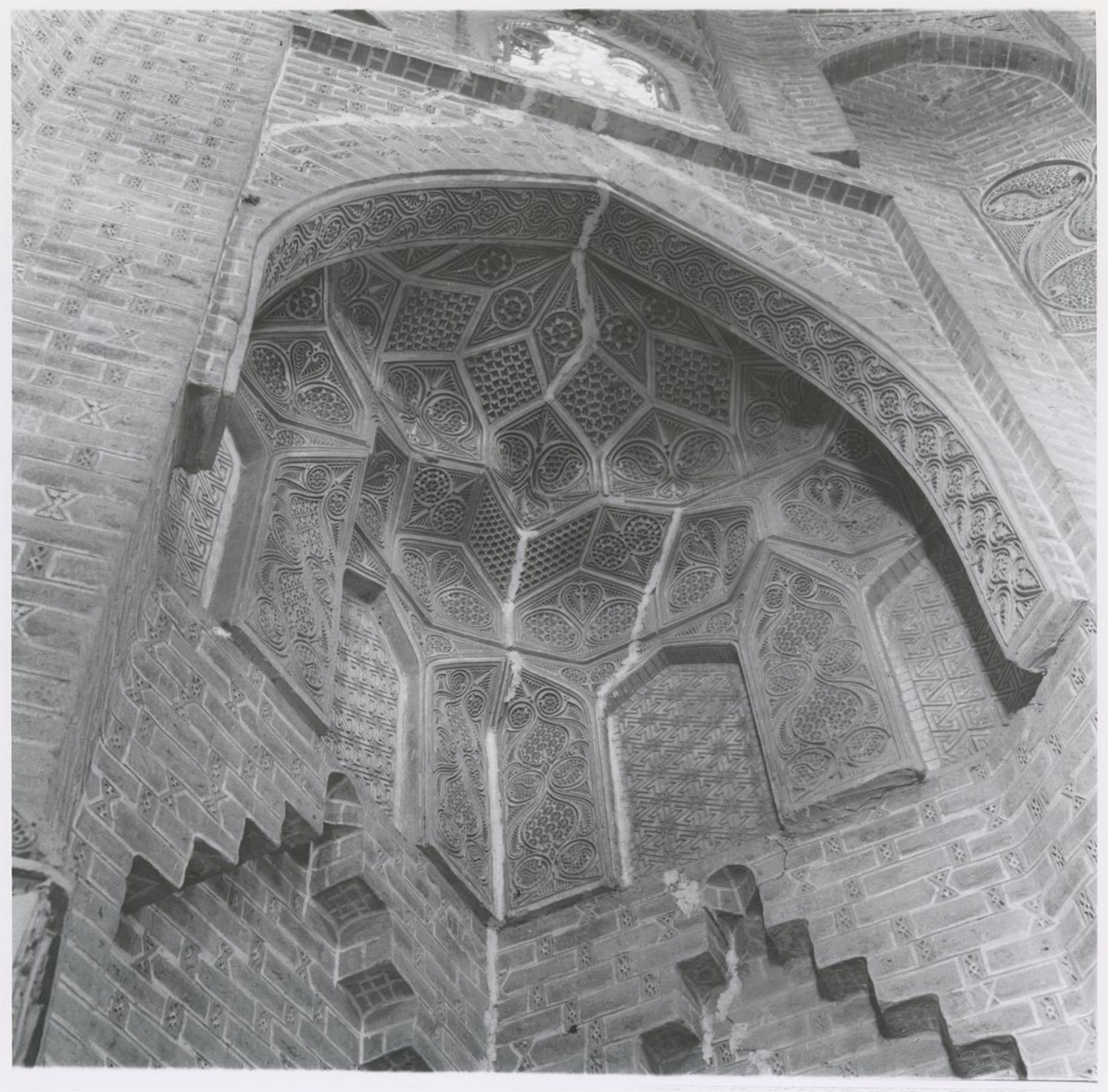

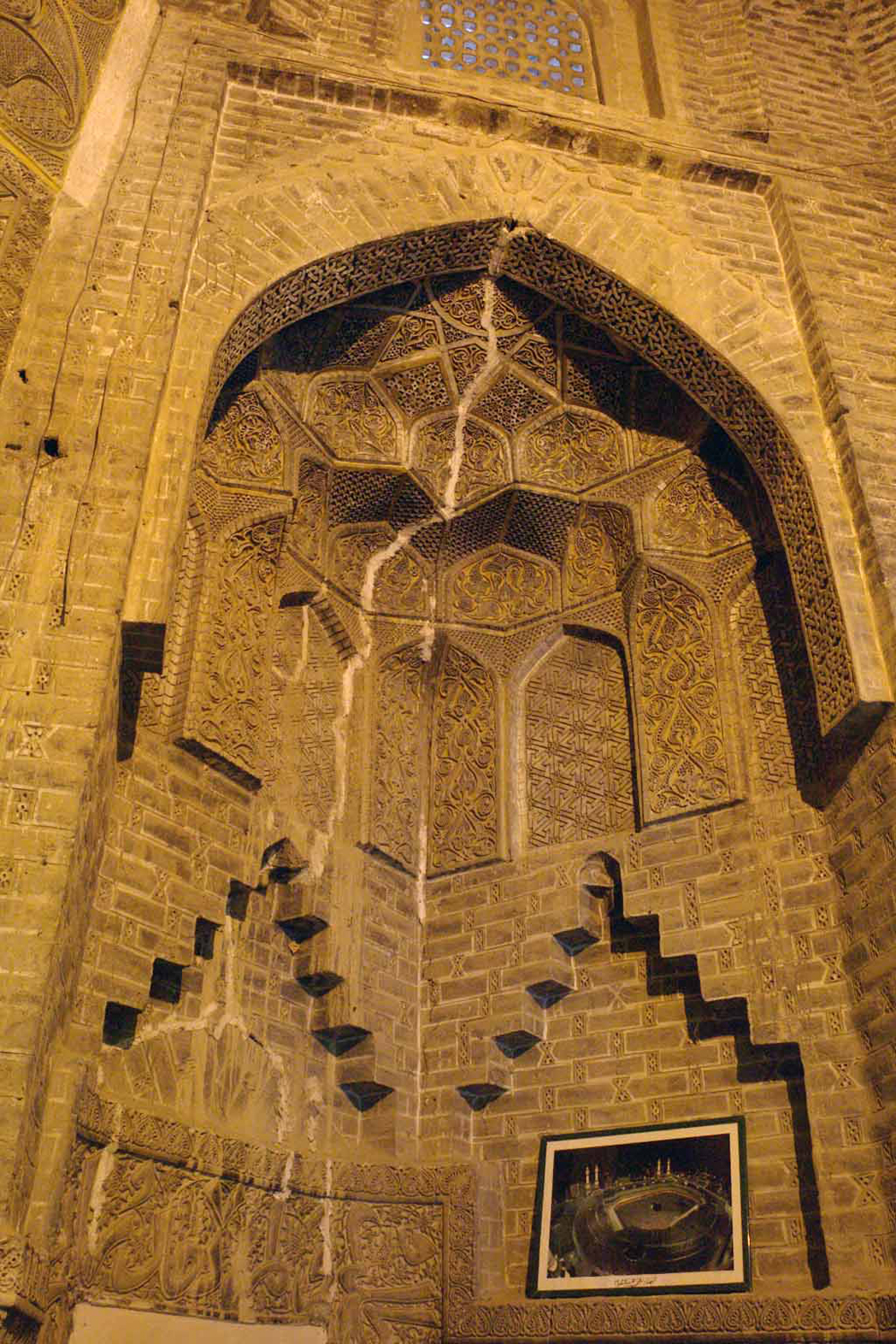

This photograph captures the corner niche to the right of the mihrab (southwest). Like many photographers after her, Dieulafoy was drawn to the carved stucco panels comprising the squinch. White plaster is visible throughout the framing arch, indicating attempts to repair or consolidate the brickwork. The window above has lost all of its internal stucco trellis, but the external screen is intact. The right edge of the horizontal stucco panel above the mihrab is visible and slightly detached from the wall.

Jane Dieulafoy, June 1881. Print preserved in Perse 1, 4 Phot 18 (1), p. 65, no. 134, Bibliothèque de l’Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art (INHA), Paris.

Related pages:

- Dieulafoy in Photographers

- Photo Album

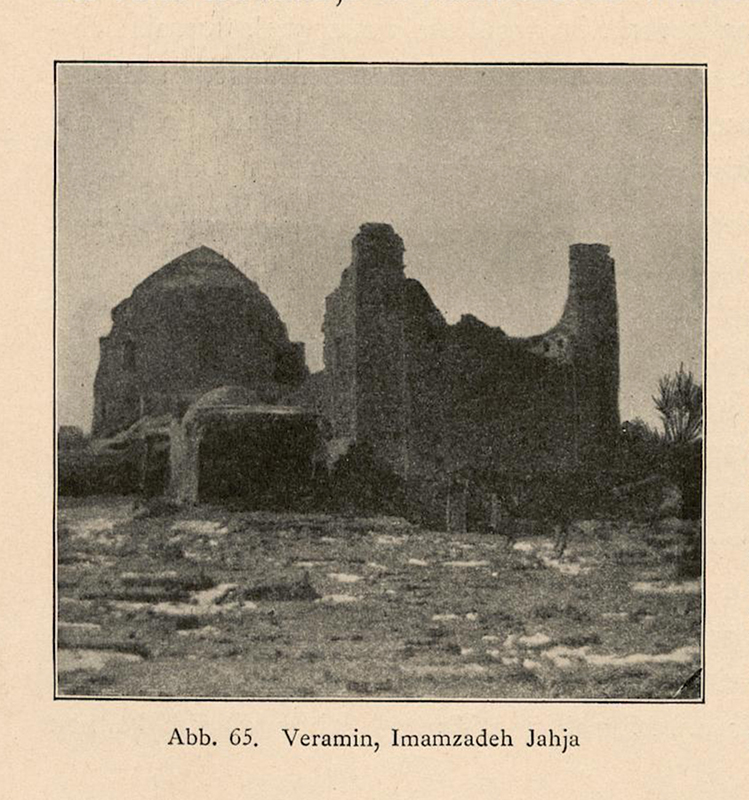

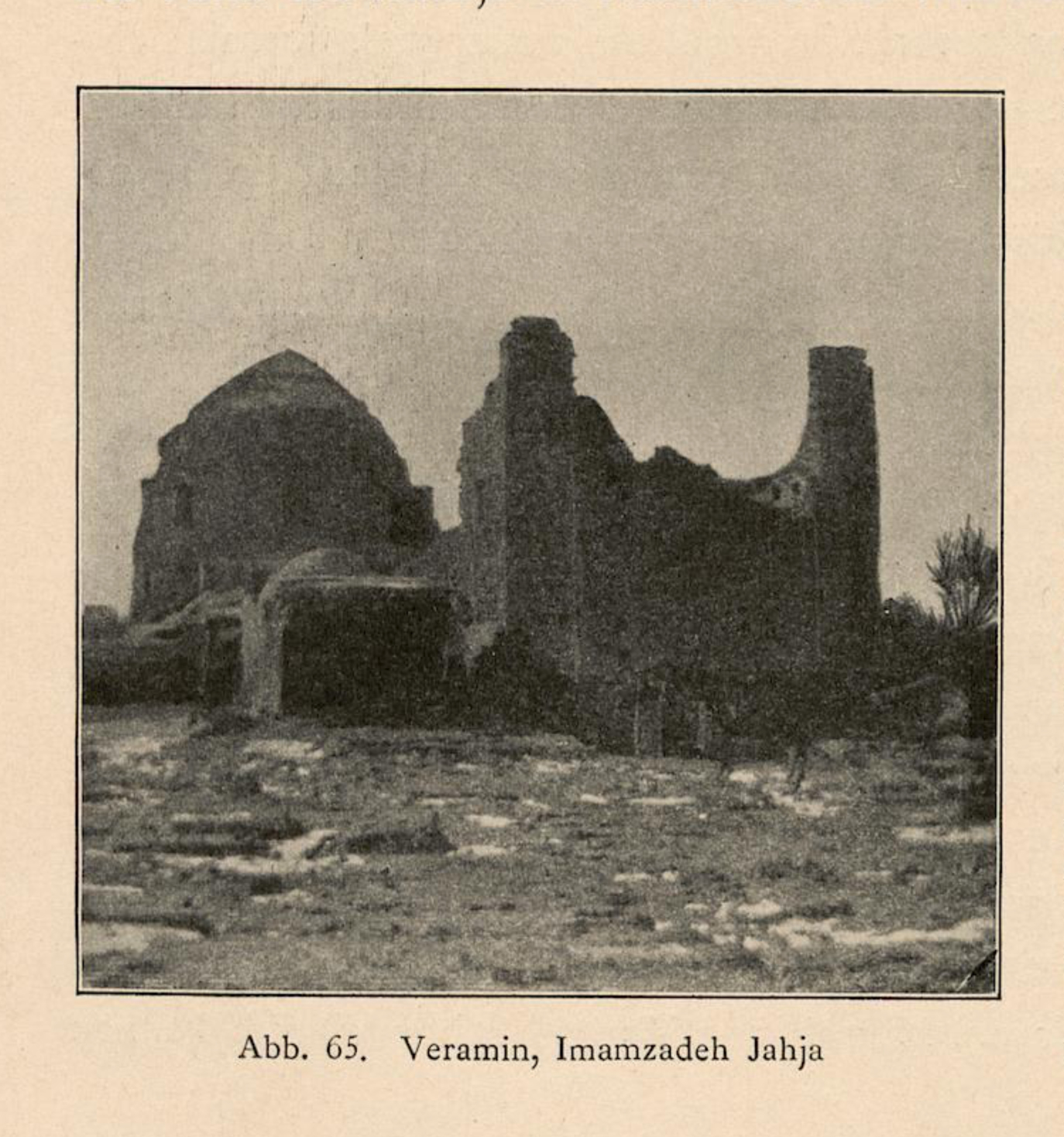

This photograph was taken from the opposite angle of Dieulafoy’s general view (no. 1). The conical roof of the tower is just visible through the dilapidated entrance portal, and more of the domed tomb is visible in the background. To the left of the portal is a low structure, and in the foreground are traces of what are likely graves. This is the last known view of the complex in this configuration.

Friedrich Sarre. Print published in Sarre’s Denkmäler Persischer Baukunst, 1910 (textband), p. 59, pl. 65 (Heidelberg University). Unfortunately, the original glass plate has not been located, which would facilitate a closer reading of this important image.

Related pages:

- Sarre in Photographers

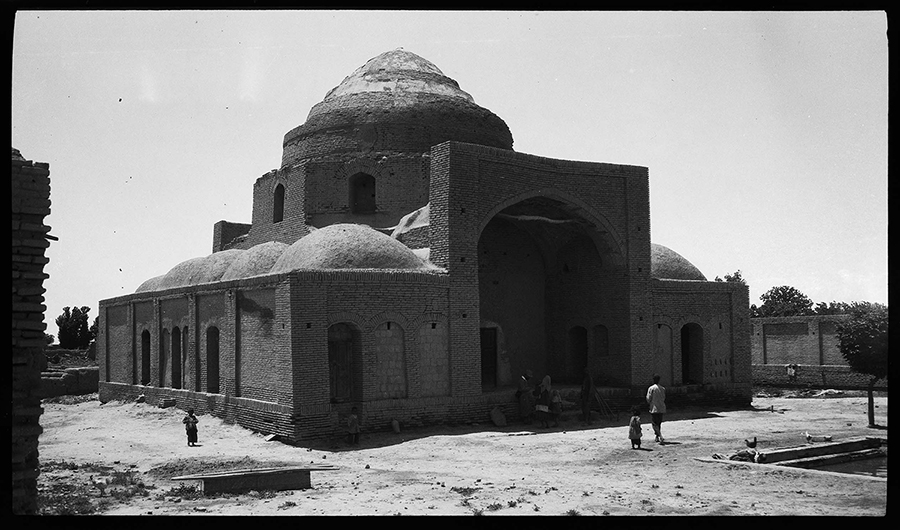

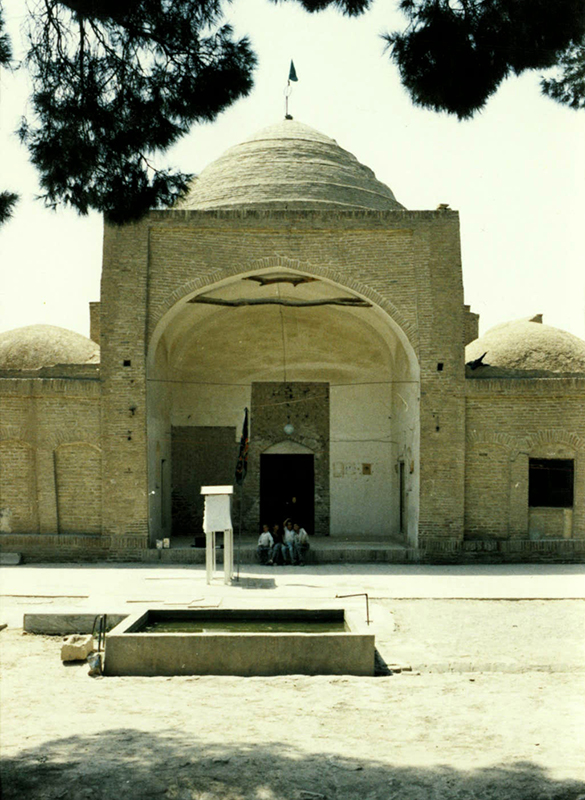

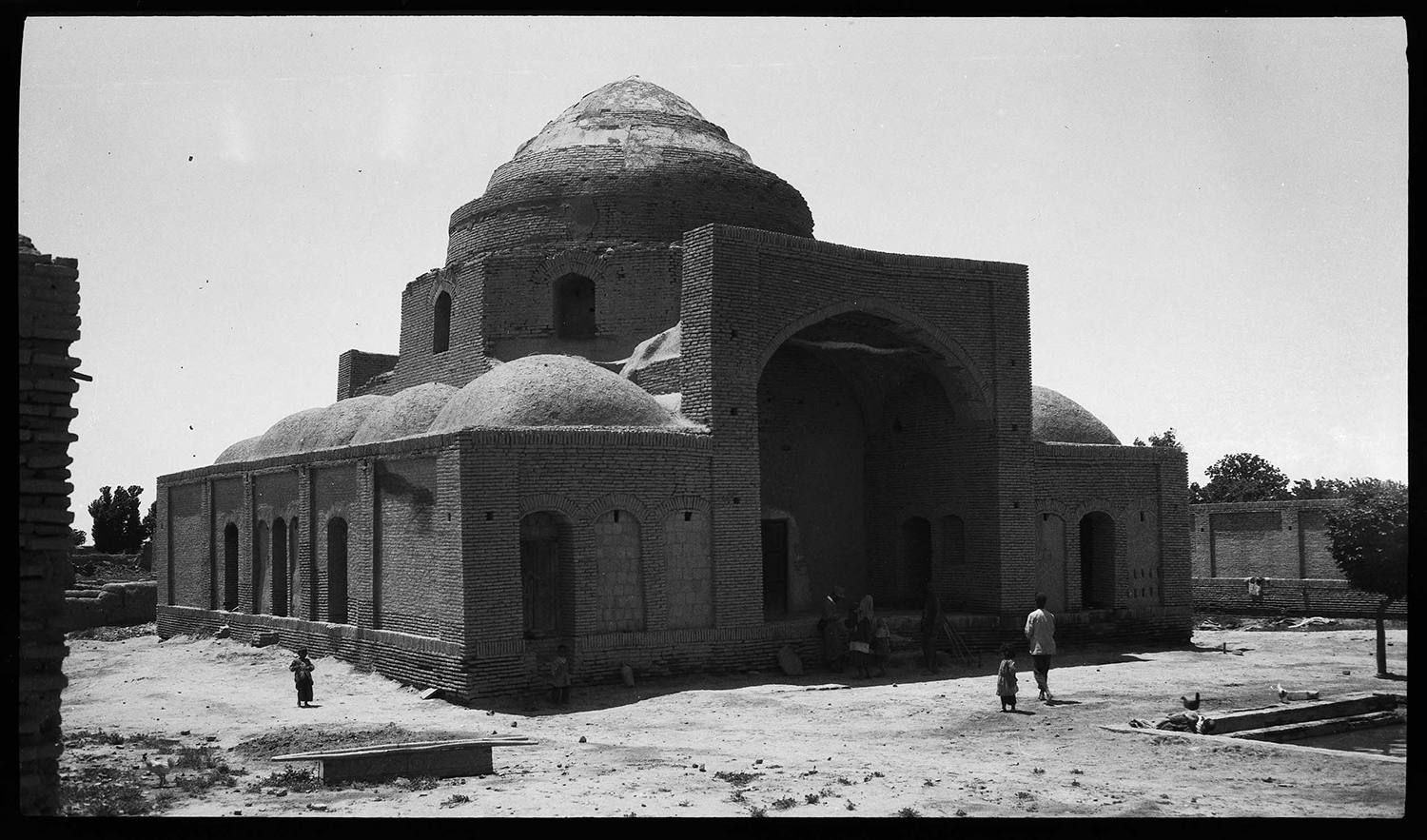

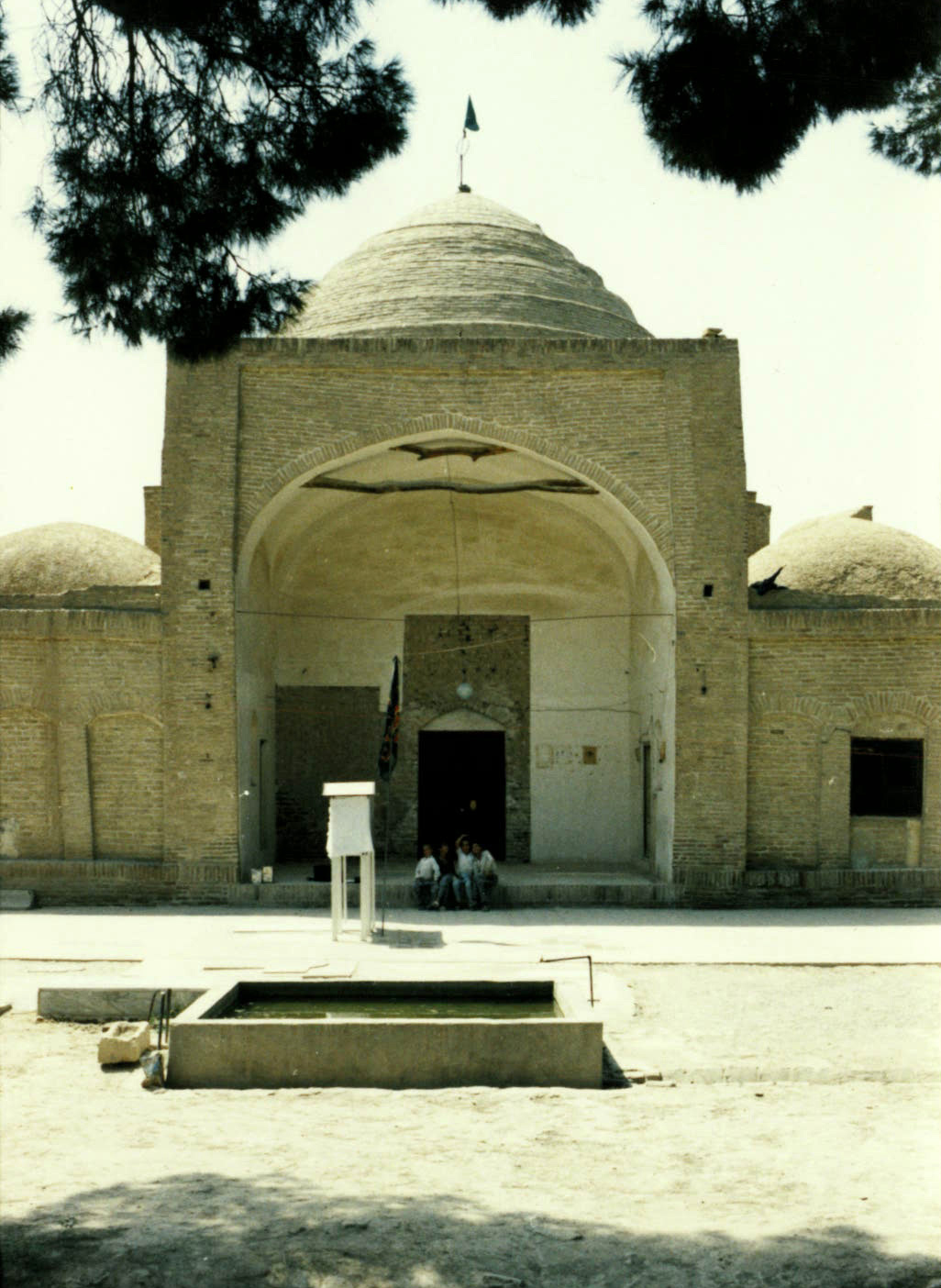

Almost forty years have passed, and the Emamzadeh Yahya has been significantly reconfigured. The only remaining feature from Sarre’s 1897 photograph (no. 5) is the main tomb, which now sits in the middle of a courtyard with a water tank. The tomb is now ringed by new elements: domed rooms on the east and west and a large eyvan on the north and south. The dome of the original tomb shows signs of wear and patching whereas the new surrounding ones are smooth. The arch of the visible north eyvan is supported by a wood beam, and the entrance into the tomb can just be seen (a closed door). On the side of the eyvan, another door leads into the new side room. The photographer stood in the northeast corner of the complex next to a structure possibly projecting from the new courtyard wall (see the bricks on the far left). This regular wall of fired bricks can be seen in the distance, on the right. On the opposite side of the photograph, behind the tomb, the courtyard has not been cleared, including of what may be some of the original walls. A notable feature of this image are the nine people around the tomb, including four small children and a baby. The clothes, chickens, and pots scattered throughout the courtyard indicate that they (or someone) likely live in the complex.

Albert Gabriel, 1934. © Ministère de la Culture (France), Fonds Albert Gabriel INHA, Médiathèque du patrimoine et de la photographie, 20K005153.

These six photographs (nos. 7–11) were taken in the 1930s and also document the transformed complex. This view from the east shows the wall of the new rectangular courtyard. Some sort of dwelling abuts this new wall, and there is also a small side entrance. The domed tomb is visible in the background, now fronted on the north and south by an eyvan and on the east (visible here) and west with lower domed rooms. The latter have smooth fresh surfaces, while the original dome exhibits wear and loss.

André or Yedda Godard, after 1930. © musée du Louvre, Département des Arts de l’Islam, Archives Godard 1APAI/9027.

Related pages:

- The Godards in Photographers

- Watch the film about this archive

This view of the back of the tomb (south) is useful on many levels. In the immediate foreground are the original mudbrick walls just visible in the 1934 photograph (no. 6), confirming that the clearing of preexisting features remained in progress. This eyvan repeats the look of the one on the north, but in this case, there is no central door leading into the tomb directly. A door on the side of the eyvan leads into a side room, and that new wall covers a former arched opening leading into the tomb (we will return to this opening soon). Extra bricks are stored in the arched openings on either side of the eyvan, and the new courtyard wall is again visible in the distance.

André or Yedda Godard, after 1930. Print on gelatin silver bromide paper © musée du Louvre, Département des Arts de l’Islam, Archives Godard 1APAI/9025. Screenshot after Overton, “Jane Dieulafoy in Varamin,” fig. 14.

Related pages:

- The Godards in Photographers

- Watch the film about this archive

This photograph of the southwest corner of the tomb is the sharpest of the three exterior views in this series. It allows us to appreciate the brickwork of the original stepped dome and zone of transition, including windows framed by double arches. Within the dark shadows of the eyvan, we can also see the second of the blocked arched openings. In the foreground, a large passage of shadow implies some sort of deep recess or excavation.

André or Yedda Godard, after 1930. Print on gelatin silver bromide paper © musée du Louvre, Département des Arts de l’Islam, Archives Godard 1APAI/9029. The original material support is a glass plate stereo negative, 1APAI/12368.

Related pages:

- The Godards in Photographers

- Watch the film about this archive

This view of the northwest corner niche inside the tomb captures a major crack running down the center of the squinch. The image is a little out of focus, but it gives a good view of the tomb’s plastered brickwork with carved stucco plugs and painted white outlines. The bottom of the frame confirms that the lost portion of the patron’s name in the stucco inscription was gone by this time.

André or Yedda Godard, after 1930. Digitized and inverted nitrate film negative © musée du Louvre, Département des Arts de l’Islam, Archives Godard 1APAI/9033.

Related pages:

- The Godards in Photographers

- Watch the film about this archive

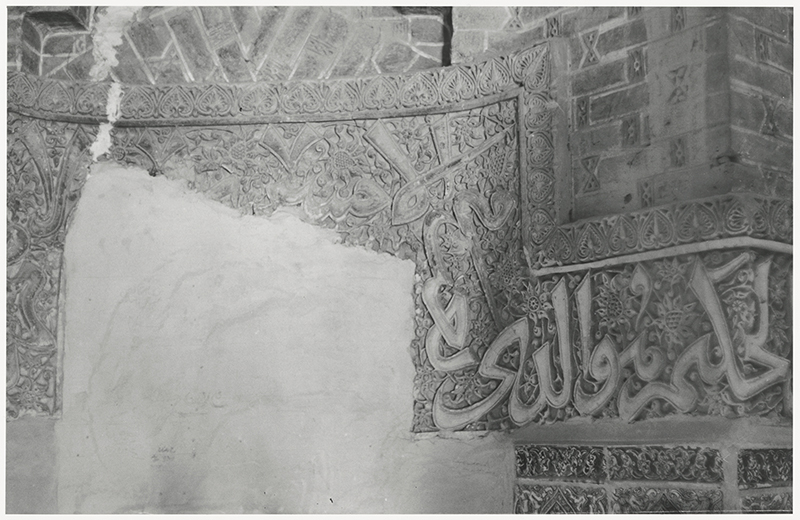

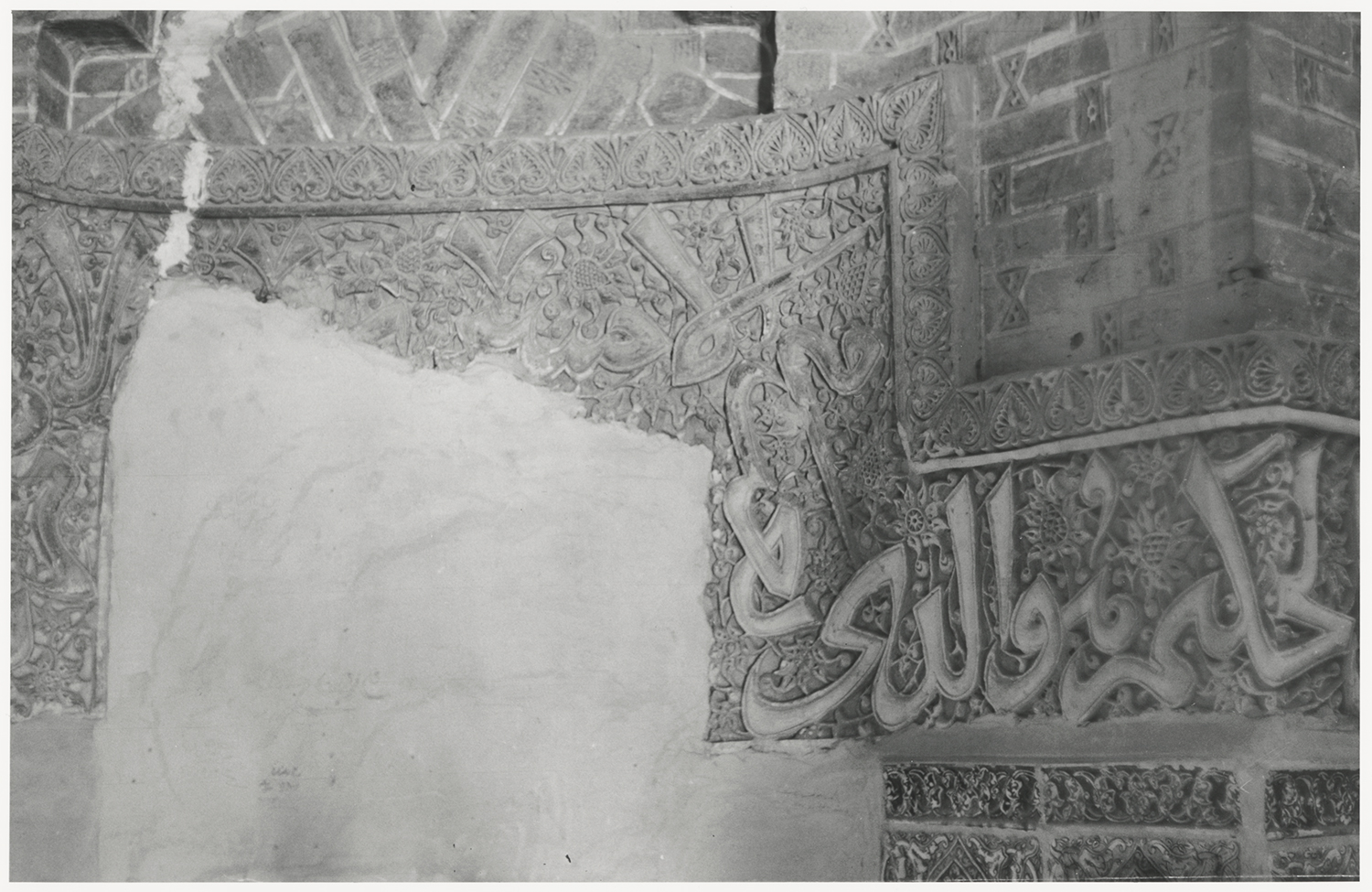

This detail of the stucco inscription in the southwest corner is useful on many levels. It conveys the depth of the stucco band and how it is slightly curved in some places. It also shows its finely carved upper border consisting of a repeated heart shape or peacock (the inspiration for this website’s logo). The thin lower border below is significantly damaged, and this likely occurred during the removal of the luster tiles that once clad the now plastered dado. This photograph also contains the evidence that allows us to date this series to sometime after 1930. On the far left of the frame is a faint yadegari (inscription written by a pilgrim) dated [xx]49. In her essay here (see no. 16), Nazanin Shahidi Marnani has interpreted this date as 1349 hijri, hence 1930–31. This reading of the date is supported by the fact that the Emamzadeh Yahya was registered as national heritage in 1312 Sh/1933. It makes sense that Godard, who signed the site’s registration documents in his capacity as the director of the Archaeological Services of Iran, would have visited around this time.

André or Yedda Godard, after 1930. Digitized and inverted nitrate film negative © musée du Louvre, Département des Arts de l’Islam, Archives Godard 1APAI/9030.

Related pages:

- The Godards in Photographers

- Watch the film about this archive

This view captures the opposite corner of the tomb on the southeast. The plastered dado shows signs of texture and cracking, suggesting that it is not a fresh layer. The lower thin border of the stucco band is mostly gone. Just visible on the bottom edge of the photograph is the top of a metal object.

André or Yedda Godard, after 1930. Digitized and inverted nitrate film negative © musée du Louvre, Département des Arts de l’Islam, Archives Godard 1APAI/9031-9032.

Related pages:

- The Godards in Photographers

- Watch the film about this archive

The snow-covered peak of Mount Damavand is just visible on the far left of this photograph, confirming that it was taken in a field to the northeast of the complex. Mudbrick walls, modest dwellings, and remnants of ruined structures populate the foreground. Portions of the shrine’s new wall can be seen, and the dome and zone of transition appear unrepaired.

Donald Wilber, May 1939. Donald Wilber Archive, Visual Resources Collections, History of Art, University of Michigan, DW-19L.

About thirty years have passed since Godard photographed the back of the tomb (no. 8). The eyvan now has two stairs and a low railing, and the arched openings to the sides have mostly been filled. Potted flowers sit on the ledge on the far right, and some sort of brush is stored in the eyvan.

Hélène Roger-Viollet and Jean-Victor Fischer, February 1958. © Hélène Roger & Jean-Victor Fischer / Collections Roger-Viollet / BHVP / Ville de Paris.

Related pages:

- Roger-Viollet and Fischer in Photographers

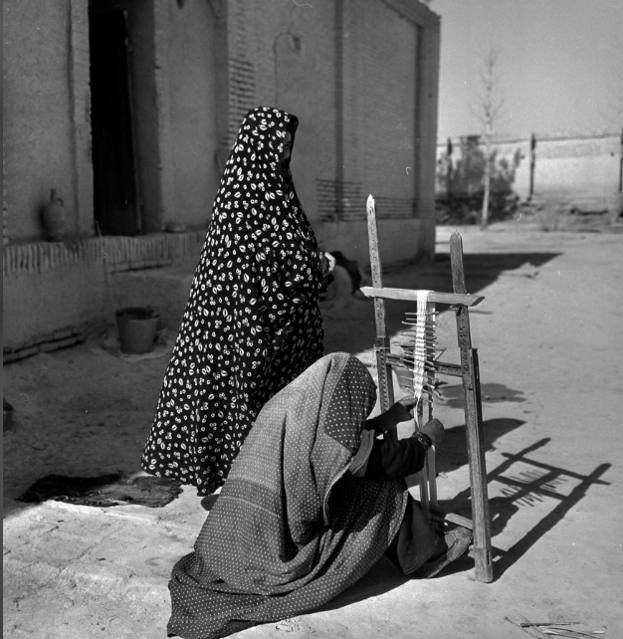

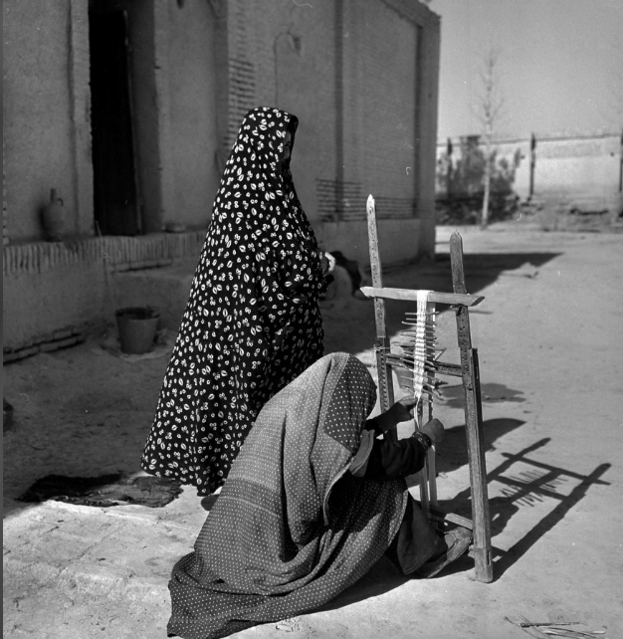

This photograph was taken on the east side of the tomb and is a rare (in this timeline) close-up portrait of two women. It is unclear what the seated woman is making on her loom, but she appears to be weaving sticks into threads. Jugs and pots are visible behind, next to the entrance into a side room. This image was taken by commercial photographers who were equally interested in people (not just architecture).

Hélène Roger-Viollet and Jean-Victor Fischer, February 1958. © Hélène Roger & Jean-Victor Fischer / Collections Roger-Viollet / BHVP / Ville de Paris.

Related pages:

- Roger-Viollet and Fischer in Photographers

This photograph was taken seventy-seven years after Dieulafoy’s (no. 3) and captures the same wooden screen shielding the cenotaph. The major difference is that the luster mihrab in the background is now gone (stolen before 1900) and has been reduced to a white void with two round arches. The cenotaph is also plastered white and was likewise robbed of its luster revetment. A number of ritual objects are adhered to and propped up against the screen, including an important ʿalamat (ceremonial standard). At the time, the Emamzadeh Yahya was the main ritual space of the village of Kohneh Gel. Depending on when this was taken in April 1958, it could have been the month of Ramadan (1377 hijri).

Probably by Myron Bement Smith, April 1958. United States Information Service Iran / National Museum of Asian Art Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Gift of Katherine Dennis Smith, FSA-2023-000001 (scroll to page 3).

Related pages:

- For a detailed tour of this photograph, see Ritual Objects

- Smith in Photographers

This is the southeast squinch of the tomb (notice the left edge of the stucco panel above the mihrab). Areas of white plaster have been applied to consolidate cracks, which again run down the middle of the squinch. The window above retains small portions of its internal stucco trellis (see the circles).

Probably by Myron Bement Smith, April 1958. United States Information Service Iran / National Museum of Asian Art Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Gift of Katherine Dennis Smith, FS-FSA-2024-010246 (scroll to p. 3).

Related pages:

- Smith in Photographers

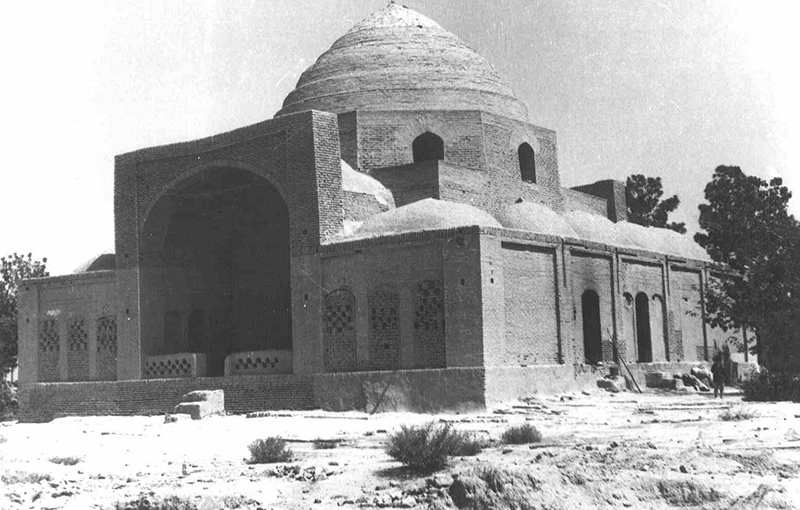

The first color photograph in this timeline, this view of the south of the tomb shows its now repaired dome and zone of transition. The terrain in the courtyard is uneven, and the edges of many tombstones protrude from the ground.

Baroness Marie-Thérèse Ullens de Schooten, probably 1950s. Ullens Collection, Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University, W475880_1. [Archnet]

Related pages:

- Ullens de Schooten in Photographers

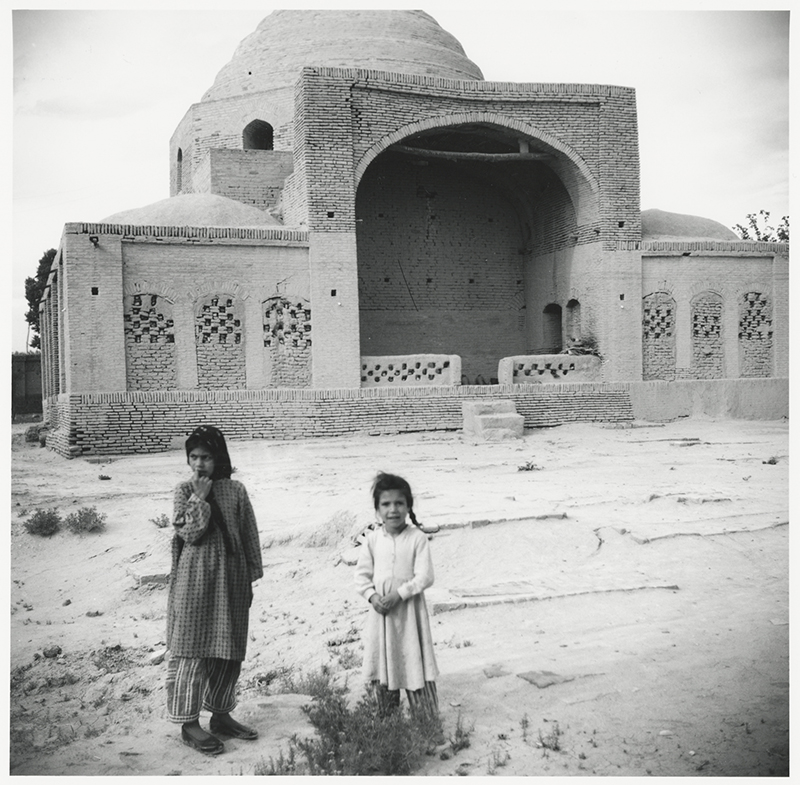

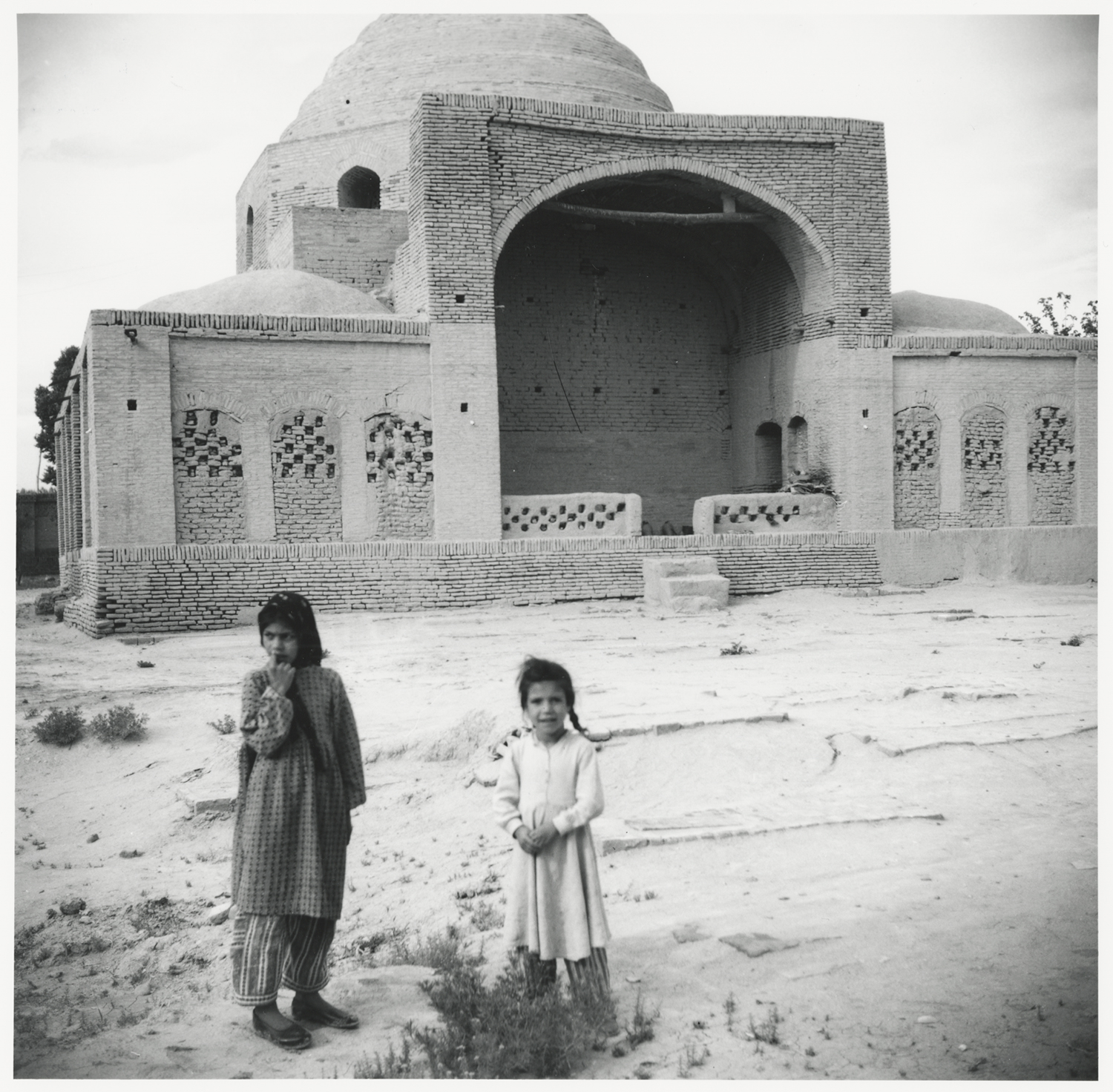

This black and white photograph was likely taken at the same time as the previous example but is distinguished by its inclusion of two children.

Baroness Marie-Thérèse Ullens de Schooten, probably 1950s. Ullens Collection, Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University.

Related pages:

- Ullens de Schooten in Photographers

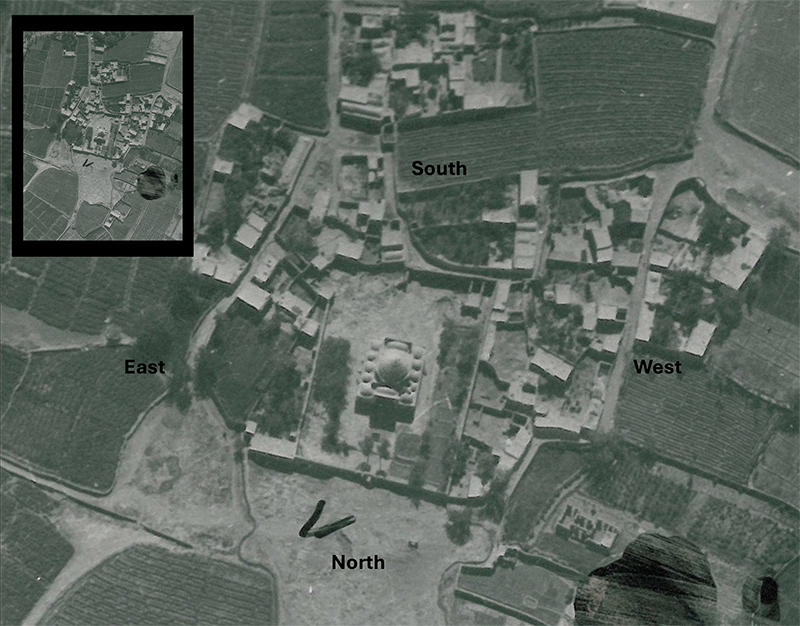

This aerial photograph is an excellent view of the once relatively isolated village of Kohneh Gel. The Emamzadeh Yahya is immediately recognizable, and the scale of the complex in relation to the modest village is striking. The area in front of the shrine (north) is largely empty, and the village is surrounded by agricultural fields. The rectangular complex is in fact not a perfect rectangle, especially in the southeast corner, where the terrain appears uneven, and some work may be in progress. The courtyard has some trees, including two near the entrance (north) and a cluster on the east. Areas of shading on the west may indicate some plantings. Many surrounding buildings directly abut the courtyard wall, and a small door at the back leads to the alleyway behind.

Photographer unknown, likely from a round of aerial photography of Iranian cities that began in 1343 Sh/1964–65. The Center for Documentation and Research of the Faculty of Architecture and Urban Planning, Shahid Beheshti University, no. 879.

Related pages:

This screenshot from a documentary film attests the Emamzadeh Yahya’s centrality in Varamin’s mourning ceremonies held during the month of Moharram to commemorate the tragedy of Karbala. Large crowds have flocked to the relatively isolated village (see no. 20) to partake in processions (dasteh) around the shrine. The dome of the tomb and the courtyard wall are visible in the background. The original film shows groups of mourners parading ceremonial standards (ʿalam, ʿalamat) and banners (parcham) and partaking in rituals like chest and chain beating (sineh zani, zanjir zani).

Screenshot from a documentary film, Ordibehesht 1346 Sh/Moharram 1387/April 1967. Archive of a local resident.

Related pages:

- For some clips from this film and further context, see the Oral History with Mohammad Amini

This photograph was taken in the open area to the north of the Emamzadeh Yahya (no. 20). Two men sit in the foreground, clearly posing for a photograph with the shrine behind. The modest arched entrance of the complex is visible, and many trees fill the courtyard.

Photographer unknown, before 1970. Published in Alaoddin Azari Damirchi, Joqrāfīyā-ye tārīkhī-ye Varāmīn (Historical Geography of Varamin), Bahman 1348 Sh/January 1970. [WorldCat] [Lib.ir]

This view of the tomb from the southeast shows the side entrance and door captured in 1958 (no. 15). A small figure stands nearby, likely a child.

Photographer unknown, undated, likely 1950s–1960s, before 1972. National Library of Iran, accession number unknown.

This color photograph is striking on several levels. Taken on a clear day from an elevated position, it captures the considerable greenery that once surrounded the site. In the background, to the north, a line of tall poles (power lines?) crosses the open space in front of the shrine. The south eyvan has been freshly plastered and cleared of its railing (compare to the previous images). From this vantage point, many of the tombstones in the courtyard are visible, including many very close to the tomb. The foundation on the west is in poor condition (note the crumbling bricks). Above, peaking out of the low domes, is the exit to the roof.

Bernard O’Kane, 1972.

Related pages:

- O’Kane in Photographers

This color photograph of the qibla wall has many points of interest. The delicately carved stucco spandrels in the zone of transition retain traces of original pigment (a mustard yellow/orange), and several have large cracks. The double-layered window has lost most of its internal stucco trellis, but the external screen remains. The large stucco panel above the mihrab void also has traces of pigment and has been consolidated in many places, especially on the far right (the area detached in 1881; no. 4). Some of the white paint/plaster used to cover the new paneling of the mihrab void appears to have seeped into the adjacent stucco inscription. These edges of the inscription were damaged during the removal of the luster tiles.

Robert Hillenbrand, before 1976.

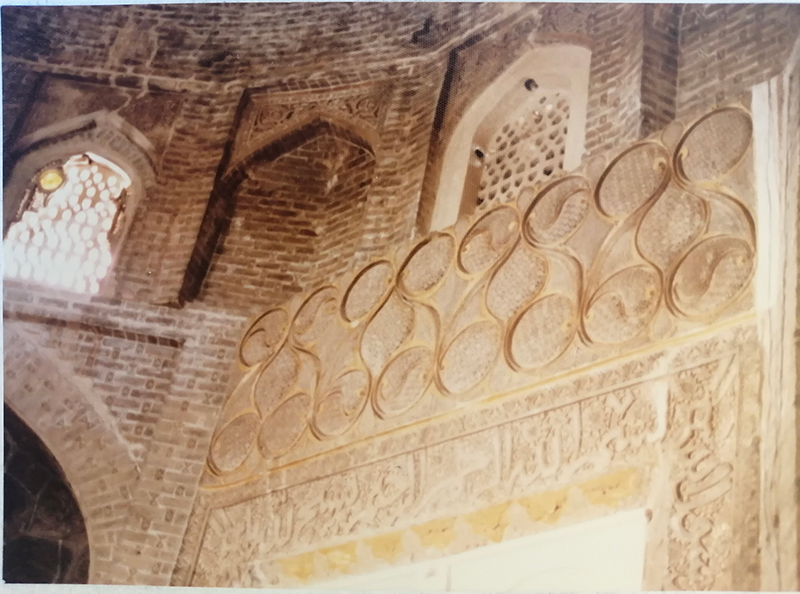

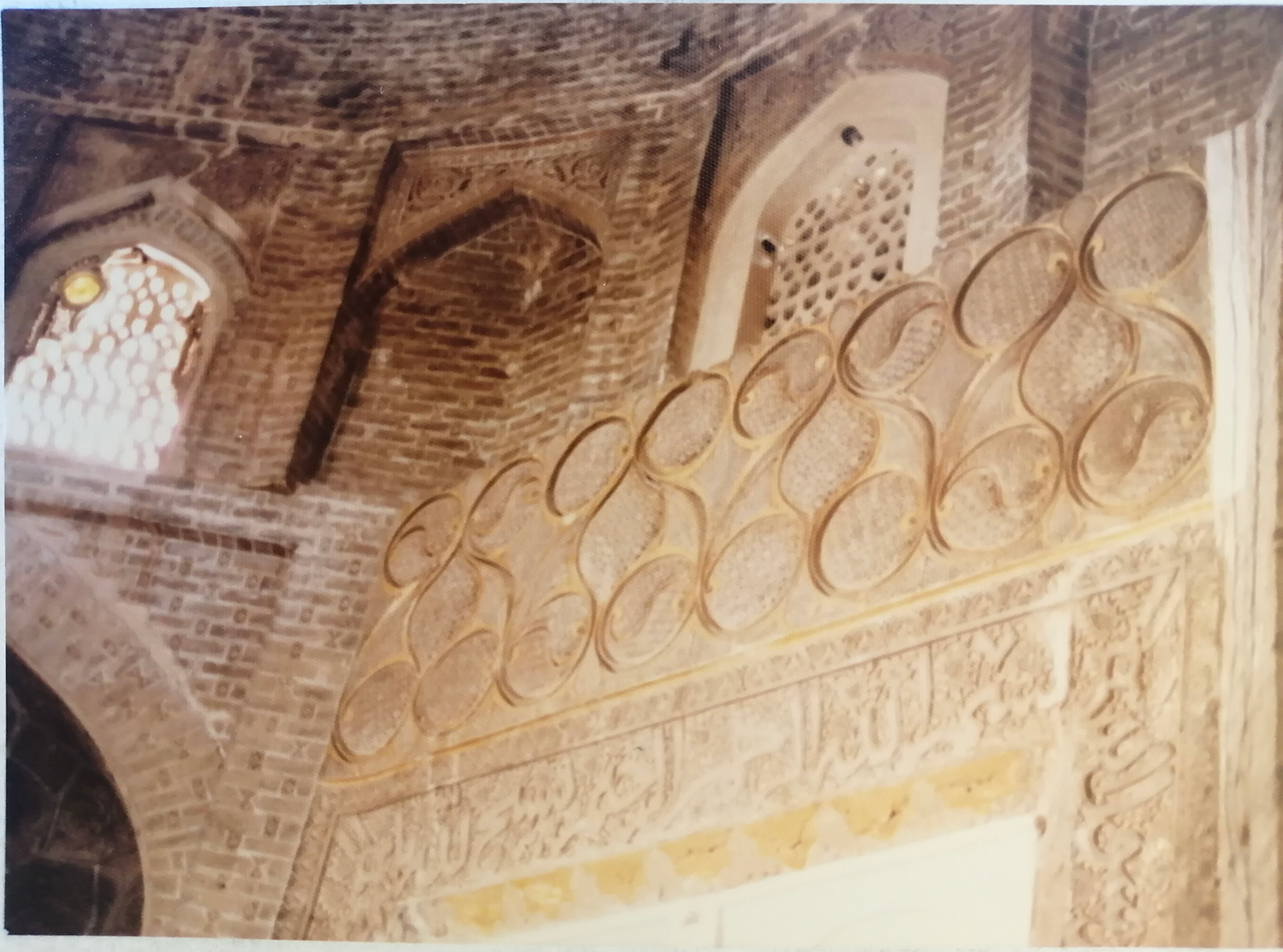

This view looking up into the southeast squinch captures its many carved facets and refined patterns as well as areas of plaster consolidation. No pigment is visible.

Robert Hillenbrand, before 1976.

This wide view of the southwest corner niche documents many areas of repair. It also captures a great deal of pigment on the underside of the arch and at the apex of the squinch.

Robert Hillenbrand, before 1976.

This view of the northwest squinch shows each carved facet framed in a border of alternating white and mustard yellow/orange. Compare to the unadorned (and hence unfinished?) southeast squinch (no. 26).

Robert Hillenbrand, before 1976.

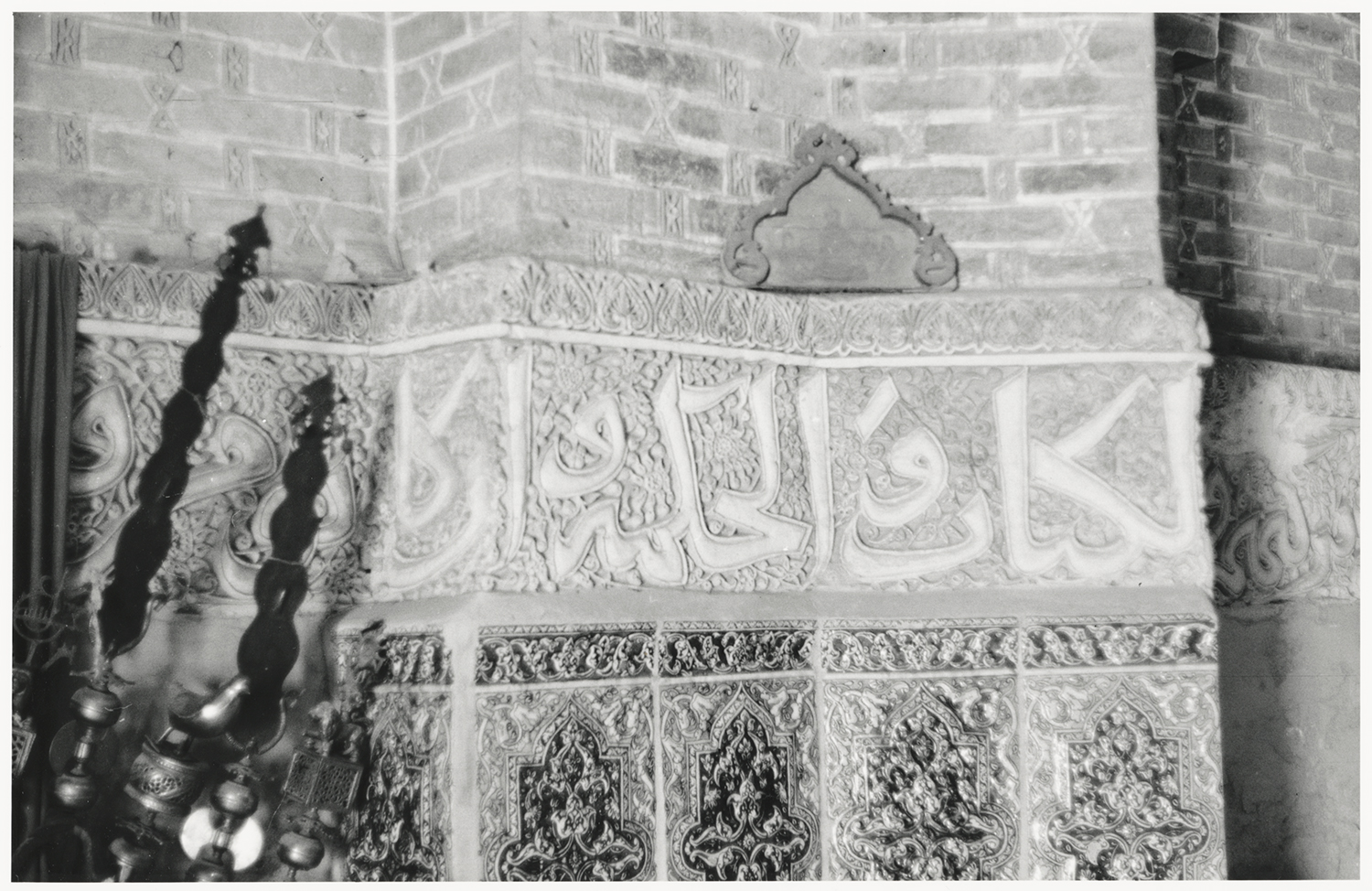

This series of five black and white photographs (no. 29–33) is part of a group of ten details of the stucco inscription. Here, we focus on the east side of the tomb, proceeding from the southeast corner (next to the mihrab) to the entrance on the north. This is the beginning of the second verse of sura al-Jumuʿah, where parts of two words are lost. As in the southwest corner (no. 11), the stucco band curves slightly, and the arch of the former opening can be seen above. It appears that some yadegari may be written on the plastered dado below. A few underglaze tiles added to the dado around 1890–1910 to mask the voids of the stolen luster tiles are visible on the lower right.

Robert Hillenbrand, before 1976. Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University, IrPV.476, acquired by the library in 1985 from the Islamic Architecture Archive, Edinburgh.

Moving to the left, this is the middle of the second verse of sura al-Jumuʿah (a wider shot of no. 12). On the far left, we can see how the upper lip of a replacement tile projects slightly above the base of the stucco inscription.

Robert Hillenbrand, before 1976. Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University, IrPV.477, acquired by the library in 1985 from the Islamic Architecture Archive, Edinburgh.

This photograph shows more of the circa 1890–1910 underglaze tiles and is particularly useful for its capturing of ritual objects. Resting on the upper edge of the stucco band is a small framed image. A large figure sits in the center and is flanked by two smaller ones. Given the tomb setting, it is probable that this is Emam ʿAli and his two sons Hosayn and Hasan. On the far left, a curtain is draped over the stucco band, and some finials (tigheh) project into the frame. These appear to be the finials of the ʿalamat photographed in 1958 (no. 16), but curiously, they are not in the same order. If this were the right side of the standard, we would expect to see the calligraphic finial (see the far left) as the outermost one. These finials could be unscrewed and remounted on the horizonal crossbar, and this is perhaps what has happened in the intervening two decades. Alternatively, it could be another similar ʿalamat.

Robert Hillenbrand, before 1976. Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University, IrPV.479, acquired by the library in 1985 from the Islamic Architecture Archive, Edinburgh.

Related pages:

- Ritual Objects

- Checklist, no. 51

The right edge of this photograph shows the opposite end of the ʿalamat, which again features the sun and moon finial. It seems that the piece of fabric was probably draped over the stucco band so that the standard could be propped up against the wall without harming it. The fact that the ʿalamat was moved around in the space—from against the wooden screen around the cenotaph (1958, no. 16) to the east wall—is not surprising and may have to do with the time of year (for example, during religious holidays or not). On the left edge of the photograph, another piece of fabric is visible.

Robert Hillenbrand, before 1976. Robert Hillenbrand, before 1976. Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University, IrPV.480, acquired by the library in 1985 from the Islamic Architecture Archive, Edinburgh.

This piece of fabric was draped across the northeast corner niche. We cannot be sure why, but it seems to have shielded something. The photograph has a glare caused by light entering from the entrance (north) on the far left.

Robert Hillenbrand, before 1976. Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University, IrPV.483, acquired by the library in 1985 from the Islamic Architecture Archive, Edinburgh.

This photograph was taken in the empty field to the northeast of the complex, looking toward the modest arched entrance (compare to the aerial view, no. 20). Parts of the field look like they have been prepared for agriculture, and the homes of Kohneh Gel are visible around the complex.

Sheila Blair and Jonathan Bloom, 1978.

Related pages:

- Blair in Photographers

This view of the tomb is well known and has been used as a representative image of the shrine in online databases and museum galleries. A small raised water feature is filled with water (compare to the tank in 1934, no. 6), and the north eyvan is plastered and empty. On the left side of the façade, a tombstone has been remounted within the central arch. Many tombstones are visible in the courtyard, and pieces of loose gravel, stone, and brick are strewn throughout.

Sheila Blair and Jonathan Bloom, 1978. [Archnet]

Related pages:

- Blair in Photographers

This is a nicely lit view of the stucco inscription just inside the entrance door. The lower thin border is largely intact, and parts of the inscription have been cleaned and consolidated (see the bright sections). At the bottom, we have a good view of the relationship between the inscription and the underglaze replacement tiles below. Some plaster from the latter overlaps the former.

Sheila Blair and Jonathan Bloom, 1978.

Related pages:

- Blair in Photographers

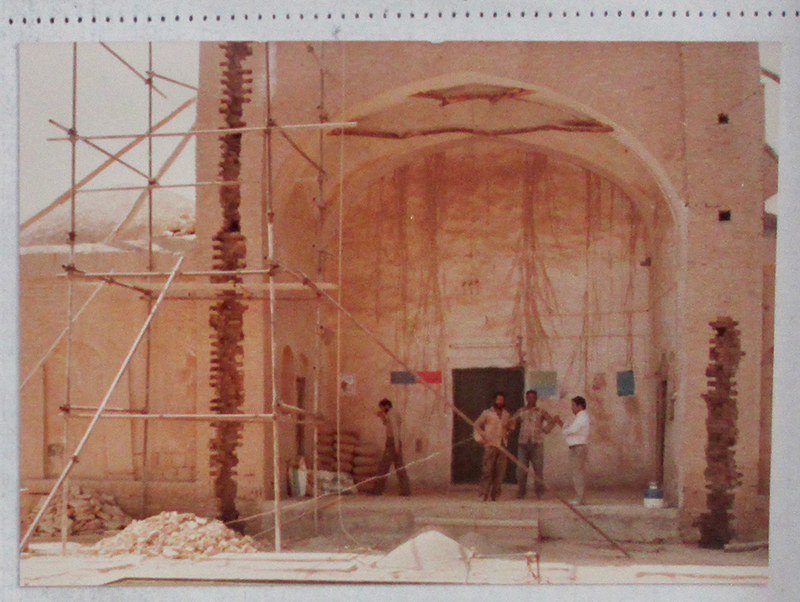

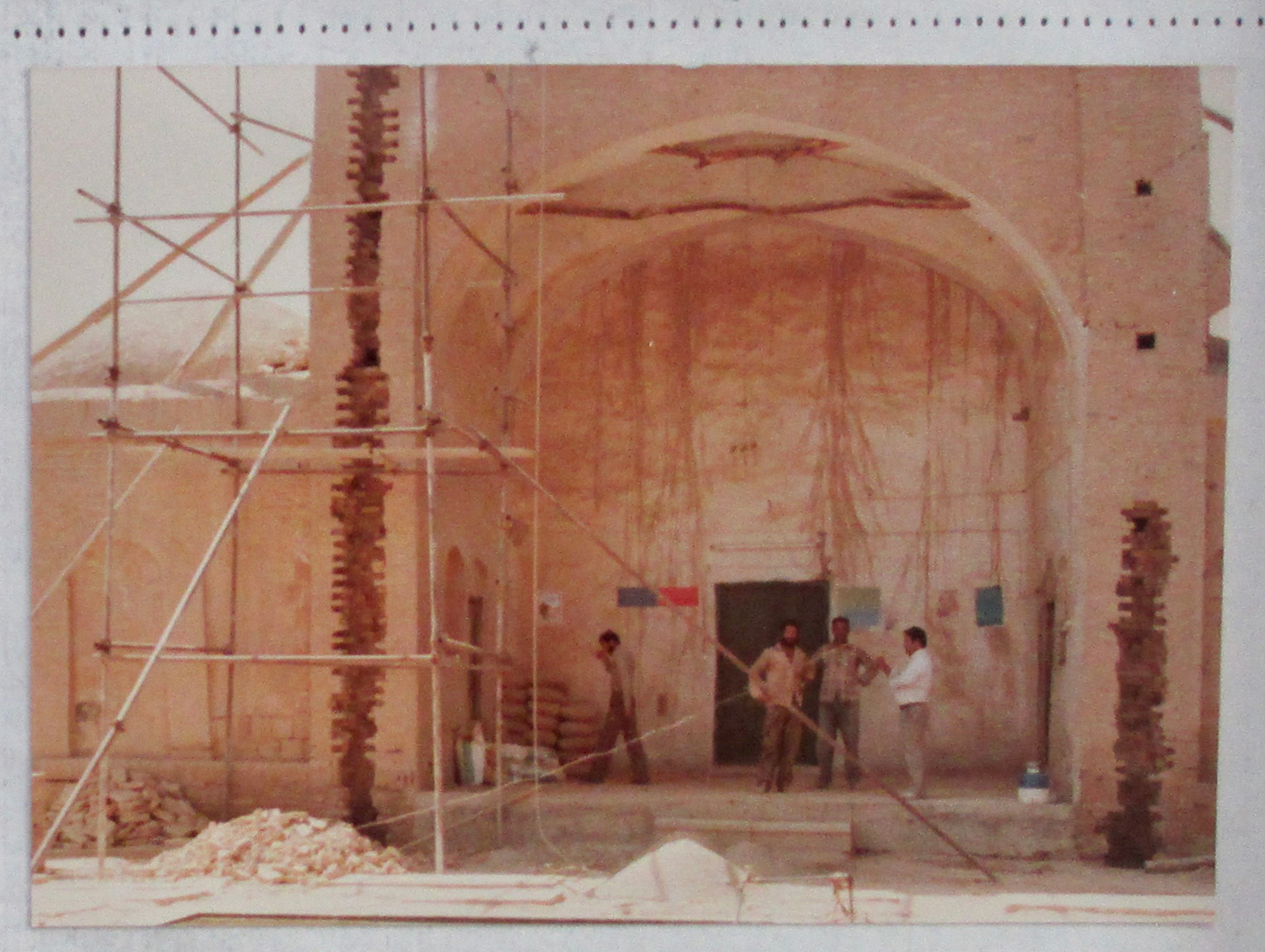

In the early 1980s, the National Organization for the Preservation of the Historical Monuments of Iran (Sazman-e Melli) initiated a multi-year restoration of the Emamzadeh Yahya. This comprehensive campaign was led by Mohammad Hasan Moheb-Ali and entailed work on both the tomb and courtyard. This photograph shows one of the first major logistical endeavors: the clearing of bricks up both sides of the tomb’s entrance in order to access and ultimately reinforce pre-existing support columns. Four men stand in the eyvan plastered white.

Photographer unknown, 1362 Sh/1983. First Phase Restoration Report of the Emamzadeh Yahya, Sazman-e Melli Hefazat-e Asar-e Bastani-e Iran. Center for Documents and Records, Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran, no. 844.

Related pages:

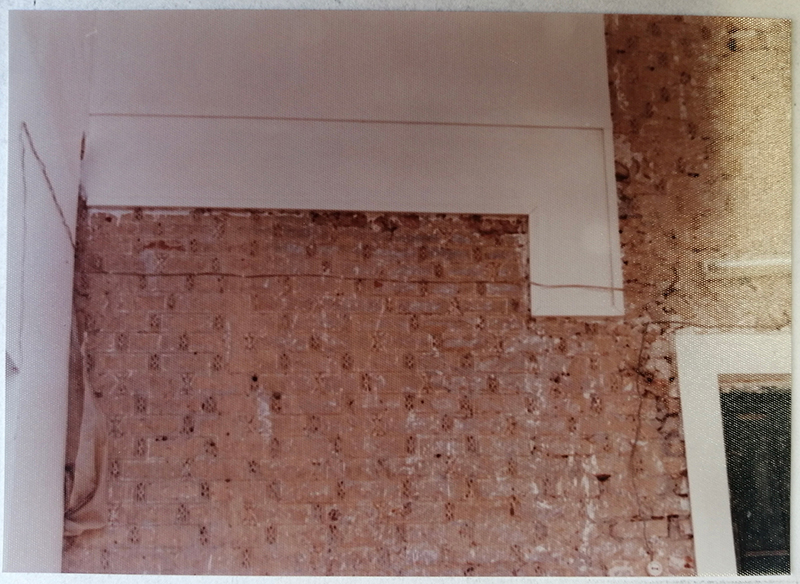

Plaster has now been removed from the lower half of the back wall of the north eyvan, exposing the brickwork underneath.

Photographer unknown, 1362 Sh/1983–84. Second Phase Restoration Report of the Emamzadeh Yahya, Sazman-e Melli Hefazat-e Asar-e Bastani-e Iran. Center for Documents and Records, Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran, no. 1797.

Related pages:

A closer view of the back wall of the north eyvan, showing a mix of recent and original brickwork. The lighter areas are the original plastered brickwork with stucco plugs, presumably dating to the Ilkhanid period. A young child is observing the work, or at least the camera…

Photographer unknown, 1362 Sh/1983. First Phase Restoration Report of the Emamzadeh Yahya, Sazman-e Melli Hefazat-e Asar-e Bastani-e Iran. Center for Documents and Records, Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran, no. 844.

Related pages:

New plaster has now been added over the recent brickwork, but the original plastered brickwork has been left exposed. Notice the stucco plugs, which are comparable to those in the interior.

Photographer unknown, 1363 Sh/1984. Restoration Report of the Emamzadeh Yahya, Sazman-e Melli Hefazat-e Asar-e Bastani-e Iran. Center for Documents and Records, Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran, no. 1801.

This photograph of the back of the tomb (south) documents the creation of a concrete boundary around the structure to ensure proper drainage and prevent moisture infiltration. This space would soon be filled with rubble and covered in flat paving. This work impacted many of the tombstones located next to the tomb, not all of which were installed in the ground. The tall forms next to potted plants are vertical tombstone boxes filled with portraits of the deceased (one is just visible) and other meaningful objects and fabrics.

Photographer unknown, 1362 Sh/1983–84. Second Phase Restoration Report of the Emamzadeh Yahya, Sazman-e Melli Hefazat-e Asar-e Bastani-e Iran. Center for Documents and Records, Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran, no. 1797.

This view shows the completed paved boundary around the tomb. Some tombstones appear to have been reinstalled in this new surface while others remain untouched in the natural terrain.

Photographer unknown, 1363 Sh/1984. Restoration Report of the Emamzadeh Yahya, Sazman-e Melli Hefazat-e Asar-e Bastani-e Iran. Center for Documents and Records, Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran, no. 1801.

Moving back inside the tomb, this photograph of the stucco panel above the mihrab can be compared with the one taken in the 1970s (no. 25). The area of heavy plaster consolidation on the right appears to be marked for treatment. Some pieces of the internal stucco trellis in the window above remain.

Photographer unknown, 1363 Sh/1984. Restoration Report of the Emamzadeh Yahya, Sazman-e Melli Hefazat-e Asar-e Bastani-e Iran. Center for Documents and Records, Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran, no. 1801.

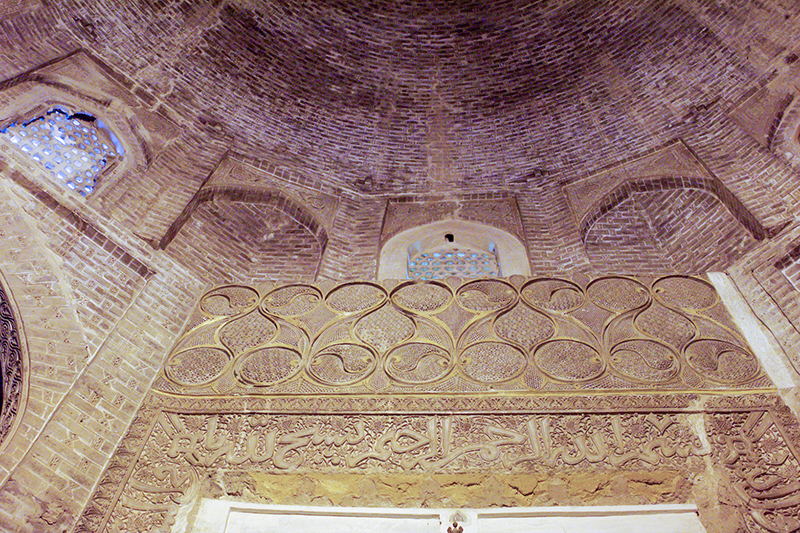

This photograph was taken after the restoration of the qibla wall. The major task entailed lifting the horizontal stucco panel off the wall, clearing the debris behind it, and remounting it in its proper position. The plaster consolidation on the right of the panel is now refined. The remaining pieces of the stucco trellis in the window above have been removed and the window is now covered in plaster. In the window on the left, a single piece of round yellow glass is visible in the stucco trellis, offering important documentation of its color. At the top of the mihrab void, we notice a significant change. The piece of horizontal white paneling just below the stucco inscription has been removed to reveal the imprints of the luster half star and cross tiles one framing the mihrab (no. 3). Just below these revealed imprints, a faint shadow is visible. This is the tip of a luster cross, to which we will soon return.

Photographer unknown, 1363 Sh/1984. Restoration Report of the Emamzadeh Yahya, Sazman-e Melli Hefazat-e Asar-e Bastani-e Iran. Center for Documents and Records, Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran, no. 1801.

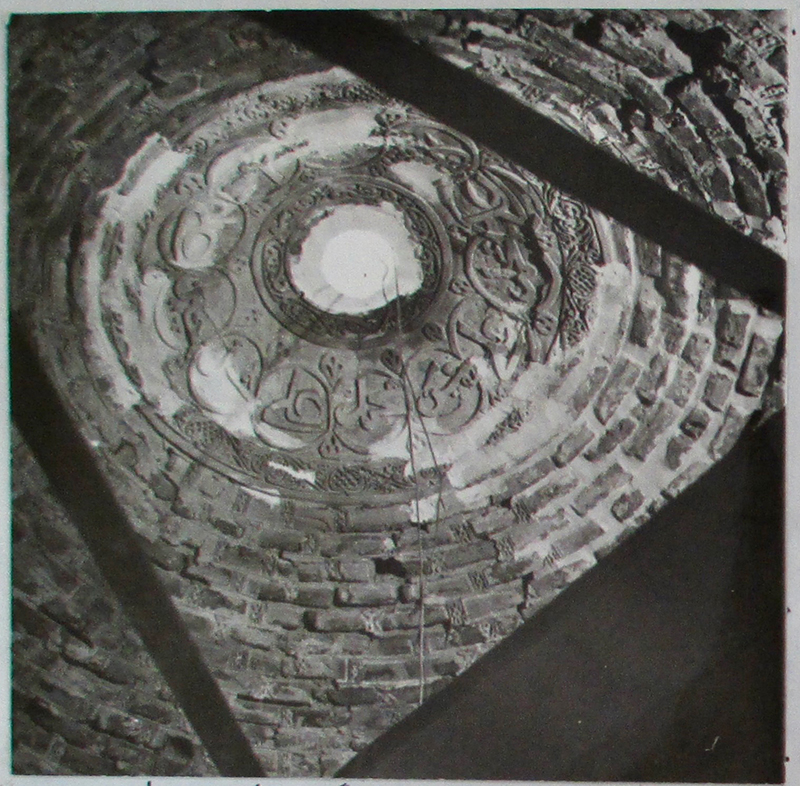

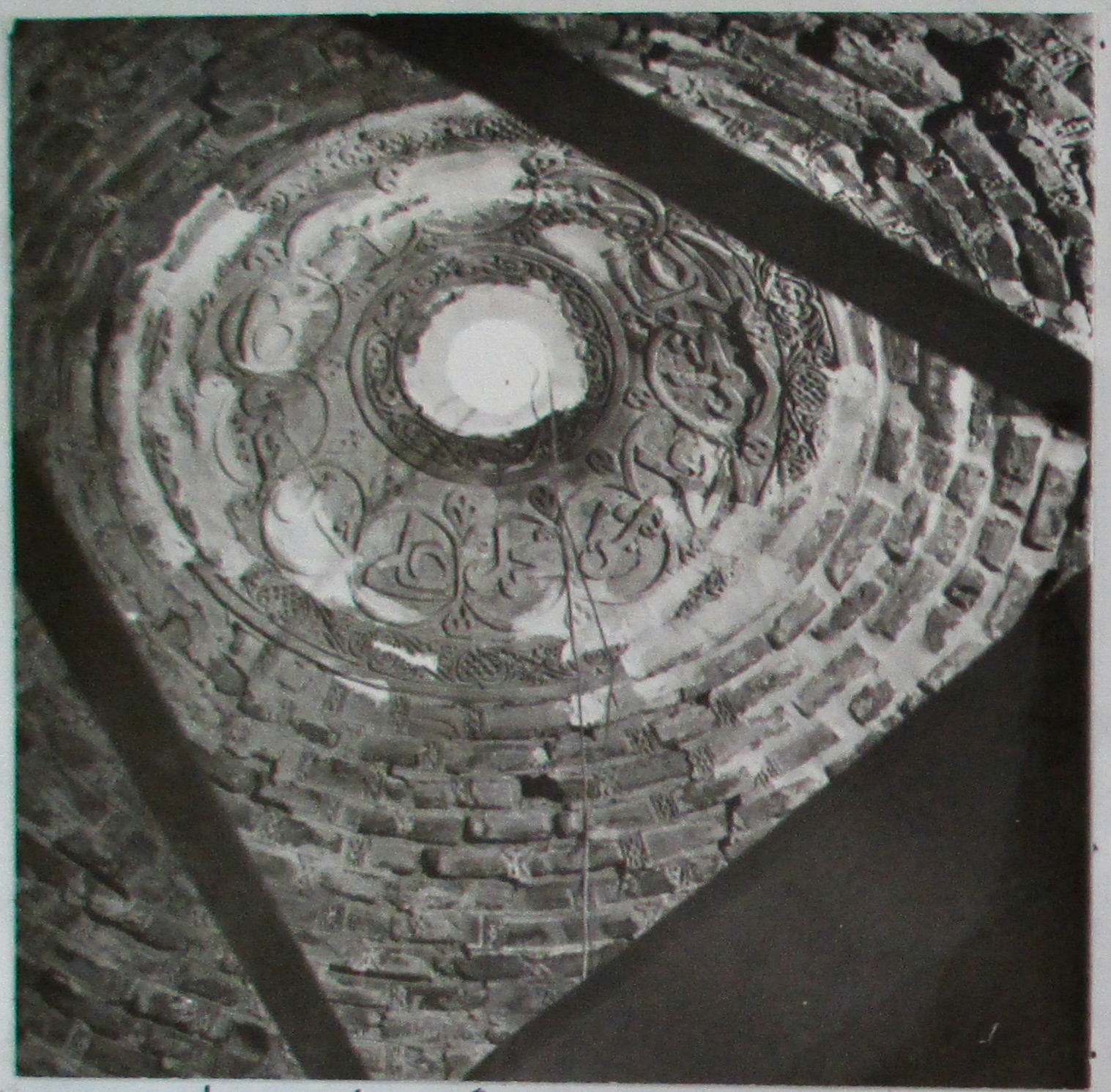

This photograph shows the apex of the dome decorated with stucco roundels bearing the names of the Twelve Emams. This was also the focus of treatment.

Photographer unknown, 1362 Sh/1983. First Phase Restoration Report of the Emamzadeh Yahya, Sazman-e Melli Hefazat-e Asar-e Bastani-e Iran. Center for Documents and Records, Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran, no. 844.

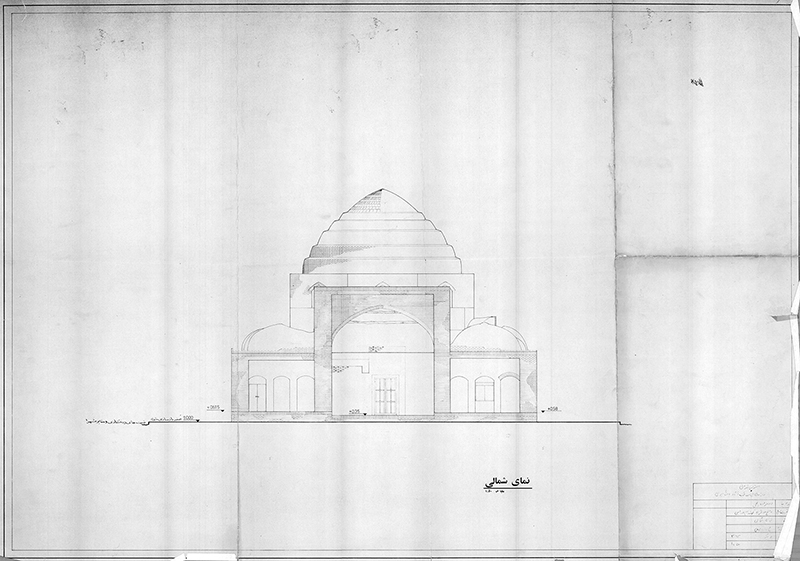

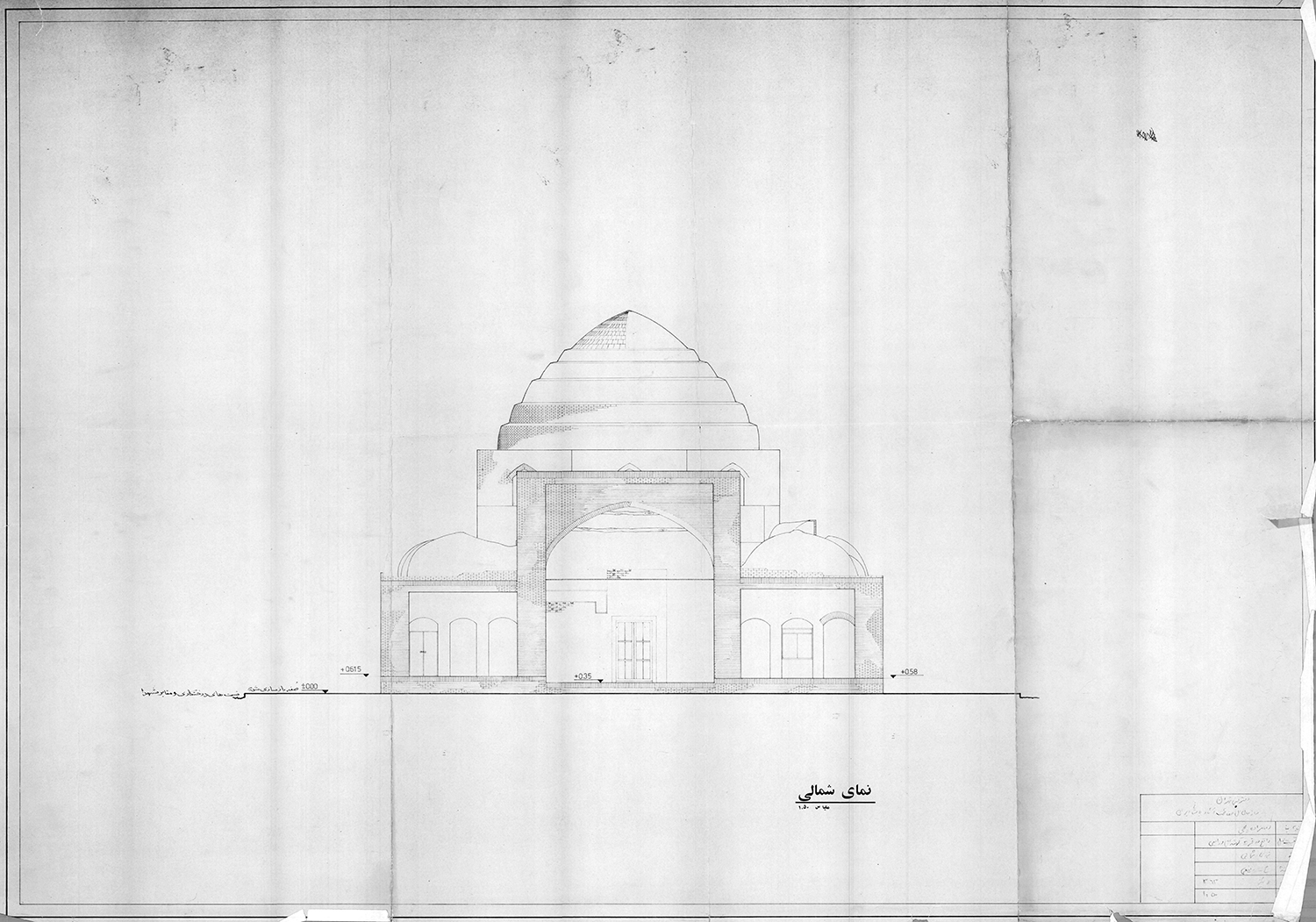

Near the end of the restoration campaign, Ataollah Rafiei prepared three detailed drawings of the tomb. Among many details, this north façade indicates the patterns of brickwork throughout, the areas of original plastered brickwork with stucco plugs in the eyvan, the wood beams above, the different configurations of the three arches on either side, and the door leading to the roof (far right).

Drawing by Ataollah Rafiei, 1363 Sh/1984. Source: Iranarchpedia

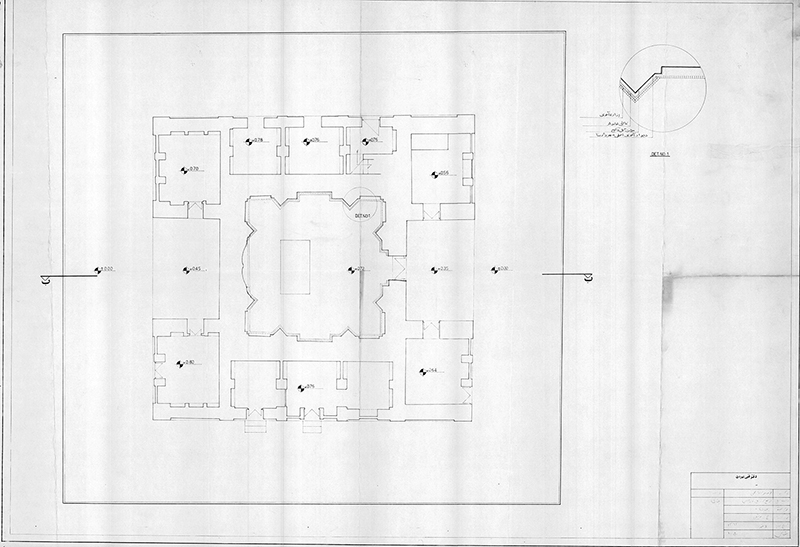

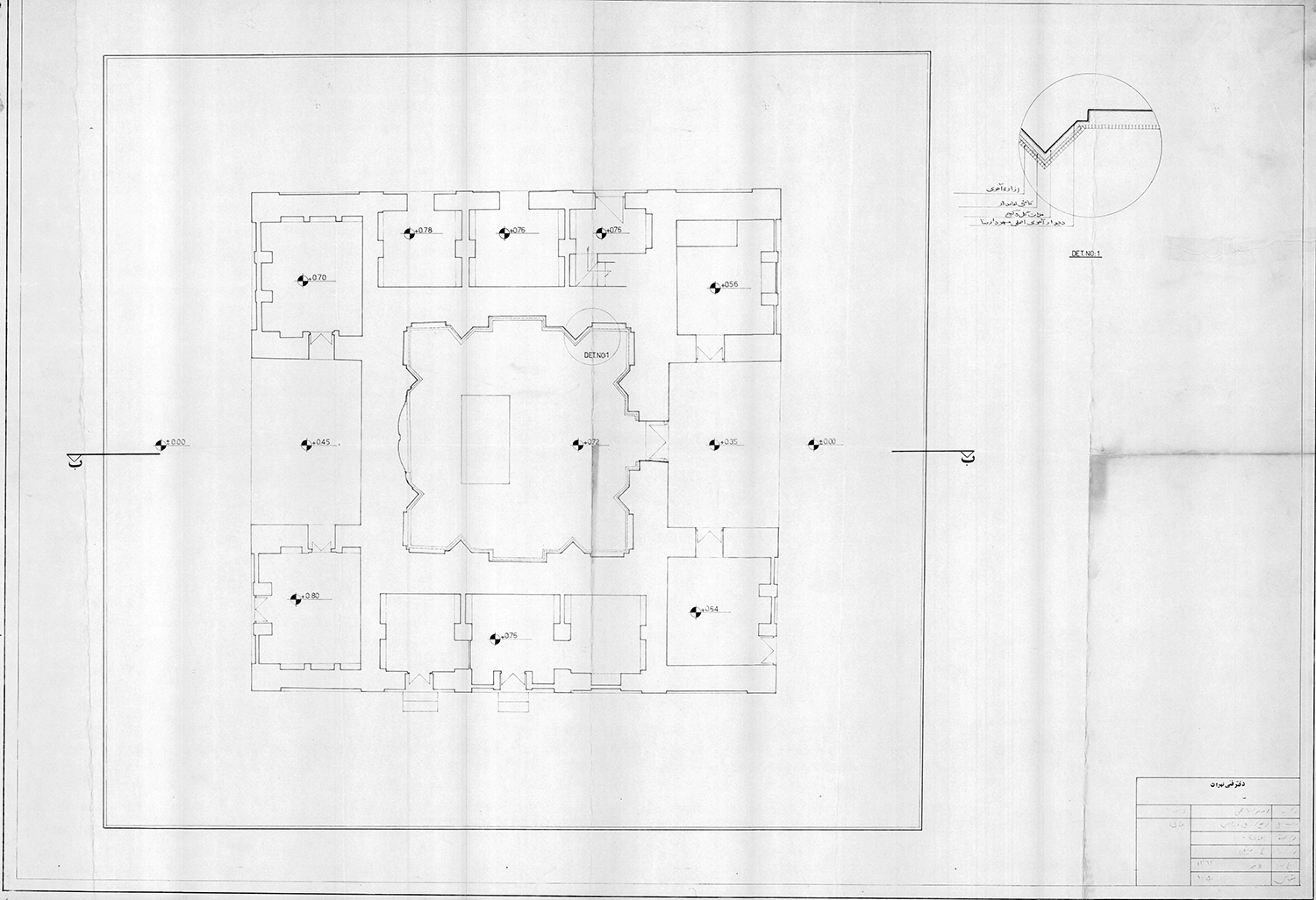

This plan is notable for its detailed drawing of the entire reconfigured tomb, not just the original octagonal chamber. As a result, we can better understand the surrounding rooms and their exits. For the tomb itself, Rafiei carefully rendered its deep corner niches and folding walls and included a detail of the latter in the upper right indicating its layers of brick, tile, and stucco. He also noted the size and location of the rectangular zarih, placed slightly toward the south (qibla) wall.

Drawing by Ataollah Rafiei, 1363 Sh/1984. Source: Iranarchpedia

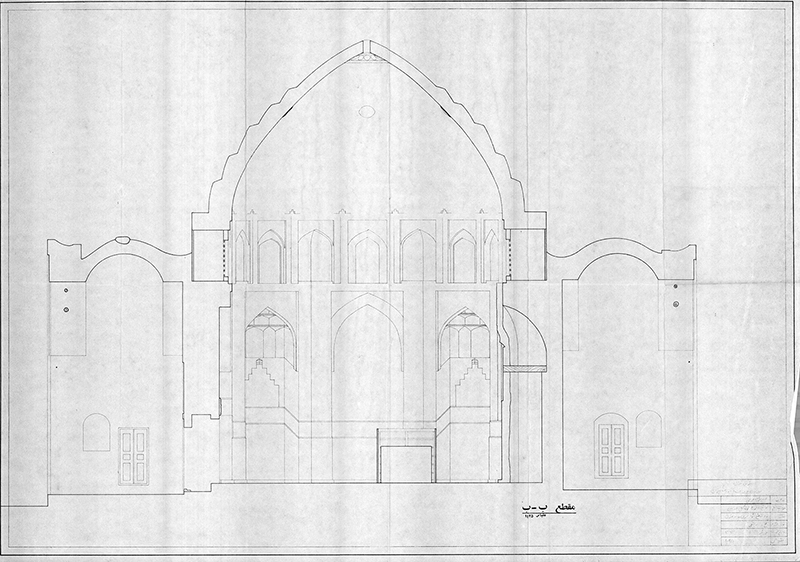

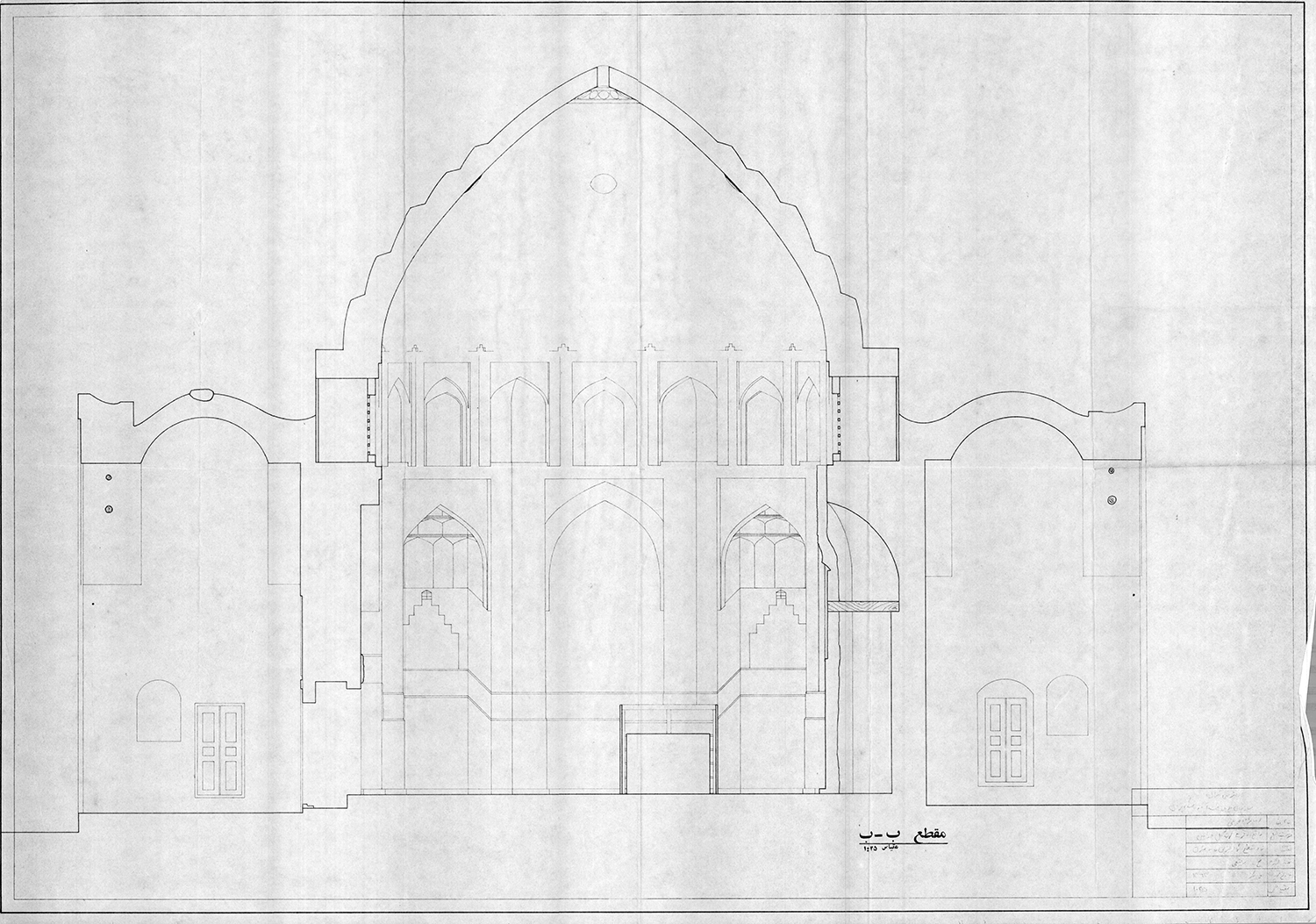

Among many details, this west section provides a sense of the width of the dome (flat on the interior, stepped on the exterior) and illuminates the large size of the cenotaph within the screen. A curious feature is the large niche indicated behind the mihrab void. The restoration reports detail the cleaning of debris behind this area, and it seems that the restorers might have discovered this niche. We continue to research this topic.

Drawing by Ataollah Rafiei, 1363 Sh/1984. Source: Iranarchpedia

By the time that this photograph was taken, the piece of yellow glass in the window on the left (no. 44) was gone. The small tip of a luster cross remounted at the top of the mihrab void is now clearly visible. In combination with the exposed imprints directly above, this fragment is a powerful reminder of the tomb’s luster tilework.

Bernard O’Kane, 1984.

View of the southeast corner niche, to the left of the mihrab. Notice the curve and depth of the stucco band and the bricks of the former arched opening.

Bernard O’Kane, 1984.

A horizontal view of the southeast corner niche. The bolsters below are covered in white lace, one of which features an elegant face. Some of the underglaze replacement tiles have also been consolidated with a white substance.

Bernard O’Kane, 1984.

View of the southwest corner niche, to the right of the mihrab. A poster of the Kaba rests on the upper lip of the stucco band, and the left side of the niche may show signs of water damage.

Bernard O’Kane, 1984.

The date of Moharram 707 (July–August 1307) in the stucco inscription on the west side of the tomb. Some yadegari are visible on the letters. A bookshelf is below.

Bernard O’Kane, 1984.

We conclude this timeline with a view of the tomb taken at some point after the restoration from beneath the shade of the trees that welcome visitors into the courtyard. Four children sit on the step of the eyvan. The wall behind is mostly plastered white, with parts of the original brickwork exposed. The tombstone remounted on the left side of the façade remains in place, and the second arch on the right is now open (compare to 1978, no. 35). The new boundary around the tomb is clear, and a vertical element (a tombstone box?) is positioned next to a flag. The water feature remains, and the terrain around it has been cleaned up.

Source: Iranarchpedia

Citation: Keelan Overton, “Photo Timeline: A Visual History of the Emamzadeh Yahya, 1880s–1980s.” In The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton, 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.