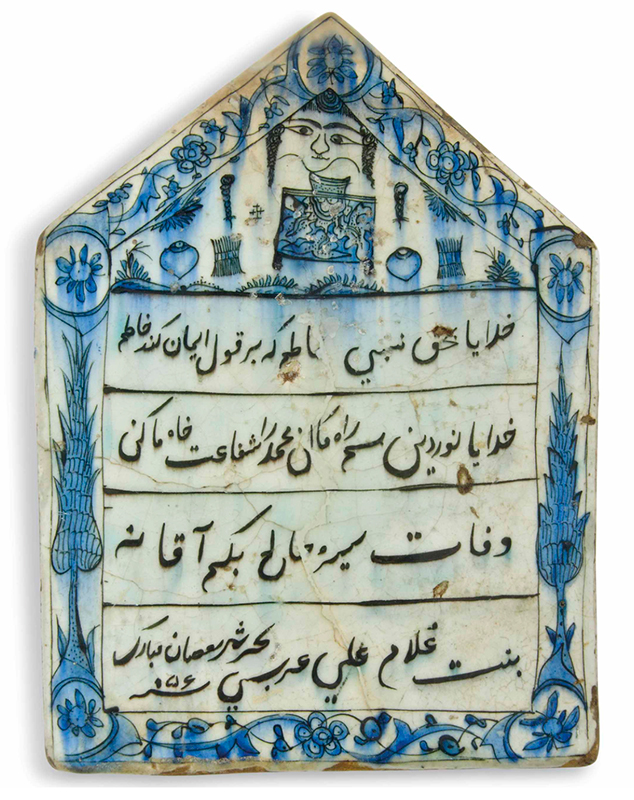

22Tombstone of ʿEsmat Ashkamiz [?] Khanom, a daughter of ʿAli-Qoli [?] Beg Shamlu, in the Emamzadeh Yahya at Tehran

Iran, dated Shaʿban 1056/September–October 1646 Fritware (stonepaste), painted in blue and black under a clear transparent glaze Currently set in the eyvan leading into the tomb of the Emamzadeh Yahya complex in Tehran Photograph by Maryam Rafeienezhad, 2024

This ceramic tombstone, painted in blue and black under a clear transparent glaze, is installed at the back of the eyvan leading into the tomb of the Emamzadeh Yahya complex in Tehran (map) (fig. 1). The tombstone has a vertical rectangular shape, with the sides curving slightly toward the pointed top, and consists of a frame decorated with objects and two cypress trees around a central inscription in six lines. A comparable composition can be seen in several other seventeenth-century tombstones, including one dated Shawwal 1050/January–February 1641 in the Institut du monde arabe in Paris (Kanda 2024, fig. 5.2.1) and one dated Shaʿban 1056/September–October 1646 sold at Christie’s in 2016 (fig. 2).

The frame on the upper part of the tombstone in Tehran incorporates various motifs: three rings (prayer seals, mohr?), a covered sarcophagus (?), double-sided comb, pair of knotted hair-like pendants, and bound book (?) (fig. 3). The comb motif is one of the most frequently depicted elements on seventeenth-century underglaze-painted ceramic tombstones. In addition to figure 2 above, it can be seen on tombstones in the Potteries Museum & Art Gallery in Stoke-on-Trent (Jumada I 1018/August–September 1609, STKMG:1950.P.251) and the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London (Safar 1037/October–November 1627, 545-1878 and Ramadan 1083/December 1672–January 1673, 513-1888).

These figural motifs evoke mourning, ritual practice, and personal identity and appear to have been carefully selected to suit the funerary context. While certain motifs were specific to the deceased’s gender, others were not. For instance, turbans and weapon sets appear to have been reserved for male burials (Kanda 2024, 366–67). An interesting comparison can be made between this ceramic tombstone and the stone tombstone of a female deceased once set against the northwest corner of the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin (see Sheikhalhokamaee’s essay, no. 3, fig. 8; Nakhaei’s essay, fig. 12). The latter also features a double-sided comb and three circular motifs, which may represent either rings or prayer seals. As Sheikhalhokamaee notes, motifs such as combs, prayer seals, and rosaries became popular from the Safavid period (1501–1722) onward and appear on the tombstones of both men and women. It is therefore more plausible that such motifs functioned as general markers of religious devotion rather than as indicators of gender.

The central inscription of the tombstone in the Emamzadeh Yahya at Tehran is composed of six lines, each set in a cartouche in a manner reminiscent of illuminated manuscripts. The inscription is executed in nastaʿliq script and reads*:

بر کشتی عمر تو گلی چو بنشست

آید ز قضا پرور کشتی یار شکست

گفتم ز که بود این شکست کشتی

گفت فریاد که از گوهری پاک شکست

وفات عصمت اشک آمیز(؟)… خانم بنت

علی قلی(؟) بیک شام لو فی تاربخ شهر شعبان سنه ۰۵۶

When a rose settled upon the ship of your life,

The fate which rears [all things] approached, [and] the ship of the beloved was wrecked

I asked, “Who caused this shipwreck?”

He said, “Alas! It was shattered by a pure gem!”

The death of ʿEsmat Ashkamiz [?]… Khanom, a daughter of

ʿAli-Qoli [?] Beg Shamlu, on the day of the month of Shaʿban, [1]056 [September–October 1646]

[*The blurry quality of the photograph makes it difficult to decipher some portions of the inscription. A few words could be interpreted differently, but the final reading reflects my interpretation. I thank Majid Daneshgar for discussing this inscription.]

The use of Persian poetry on Iranian ceramic tombstones became increasingly popular from the last quarter of the sixteenth century, gradually replacing the Qurʾanic verses, Hadith quotations, and Arabic prayers for the Fourteen Infallibles (the Prophet Mohammad, his daughter Fatemeh, and the Twelve Emams) commonly inscribed on late fifteenth- and sixteenth-century tombstones (for a 992/1584–85 example in the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin, see Sheikhalhokamaee’s essay, no. 1). Between the late sixteenth and early eighteenth centuries, two distinct types of Persian verses emerged almost simultaneously on underglaze-painted ceramic tombstones: poetic excerpts from the works of renowned poets, carefully chosen for their appropriateness to a funerary context (Type I), and madda tarikhs (chronogram poems), specially composed verses incorporating the name of the deceased and/or abjad numerals (numerical values assigned to letters) (Type II).

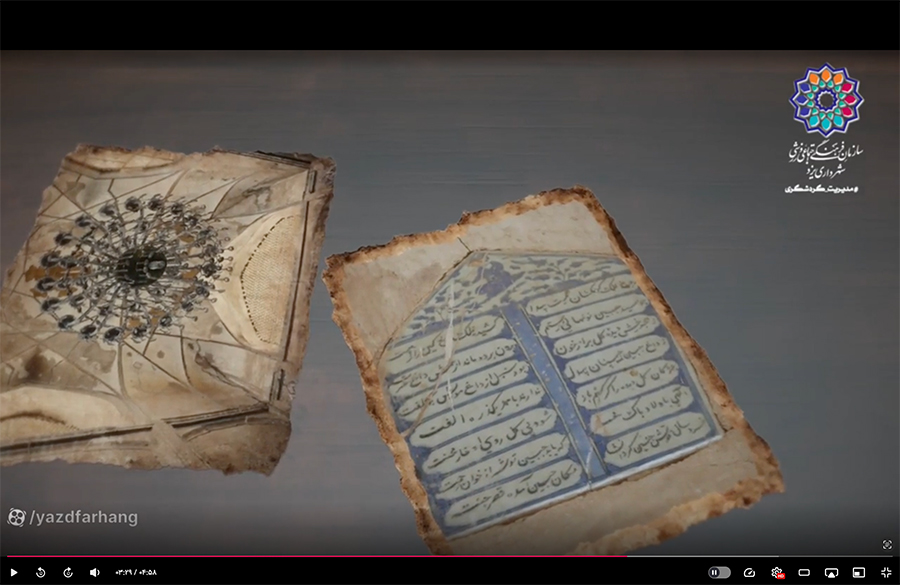

At least thirteen known examples of Type I tombstones survive, either in museum collections and without clear provenance or in situ in religious monuments, including in Kashan (Ghiasian and Mashhadi Noosh-Abadi 2022, 10–11) and this example in Tehran. Meanwhile, at least four examples of Type II tombstones remain in situ in religious buildings in Yazd. In the Boqʿeh-ye Seyyed Shams al-Din (map), for instance, a ceramic tombstone for Seyyed Hosayn features an inscription composed of Persian verses specially composed for the deceased (fig. 4). These verses include his name and the year of his death encoded through abjad numerals. The phrase مکان حسین آمده قصر جنت (The palace of paradise has arrived at the place of Hosayn) in the last line corresponds to the year 1132/1719–20. The tombstone is currently installed at the back of the eyvan leading into the Boqʿeh-ye Seyyed Shams al-Din (fig. 5).

The underglaze-painted ceramic tombstone in the Emamzadeh Yahya at Tehran belongs to Type I category. It bears a Persian verse (its source unidentified) mourning the death of the female deceased and employs motifs such as a rose and ship to symbolize the transience of life and its eventual end. Although the deceased’s name is only partially legible, it appears to associate her with the Shamlu tribe, one of the prominent Qizilbash tribes of Turkoman origin that played a pivotal role during the Safavid period. Tombstones of this type occasionally record noble or tribal affiliations, and several are known to commemorate individuals from the Shamlu clan (for instance, Kanda 2024, fig. 5.2.1). As part of the Qizilbash elite, the deceased and her family likely possessed the means to commission fashionable tombstones inspired by the palette and motifs of contemporaneous Chinese blue-and-white porcelain (Kanda 2015, 32–34; for other examples, see V&A 544-1878, 1822-1876 and 513-1888; fig. 6). Their patronage also suggests a cultivated appreciation for Persian literary culture, as reflected in the poetic inscription.

As noted above, Type I tombstones predominantly survive in museum collections, often without clear provenance. For instance, all Type I tombstones now preserved in the V&A were acquired between 1876 and 1888, but no documentation about their original locations exists. This raises the possibility of the systematic removal or plundering of such underglaze-painted ceramic tombstones during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, around the same time that luster tilework was also being stolen from sites like the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin. The fact that this tombstone remains in the Emamzadeh Yahya at Tehran is therefore notable, but its current in situ location should not be read as its original placement. In 1318 Sh/1939–40, the original structure and courtyard were demolished and subsequently rebuilt between 1320 Sh/1941 and 1330 Sh/1951–52 (Haji-Qassemi, ed. 1998, 32, 25). We can presume that this tombstone was salvaged from the original site and added to this new eyvan (see fig. 1) during the later phase of rebuilding.

Although the tombstone in the Emamzadeh Yahya at Tehran is currently out of reach and cannot be touched or easily read by visitors, it may have once been located in a more accessible area. Visitors approaching it would have immediately noticed the verb shekast, which signals the death of the deceased. Given the standardized content and limited variation in the Persian verses inscribed on ceramic tombstones, it is plausible that Persian poetry was recited alongside Qurʾanic verses during grave visitations. The surviving yadegari in the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin attest the importance of Persian verses during ziyarat (pious visitation) (see Shahidi Marnani).

Sources:

- Ghiasian, Mohamad Reza and Mohammad Mashhadi Noosh-Abadi. “Kashi-ha-ye haft-rang-i mazar dar ziyarat-ga-ye Soltan-e ʿAta-bakhsh va Soltan-e Amir Ahmad-e Kashan (sadeh-ye dahom ta sizdahom-e hijri-ye qamari) (Cuerda Seca [haft rang] Tomb Tiles in the Shrines of Sultan ʿAta-bakhsh and Sultan Amir Ahmad in Kashan [16th-18th Centuries AH]).” Journal of Iranian Architecture Studies 10, 20 (2022): 5–26. [magiran]

- Haji-Qassemi, Kambiz, ed. “Emamzadeh Yahya.” In Ganjnameh: Cyclopaedia of Iranian Islamic Architecture, vol. 3, Spiritual Buildings of Tehran, edited by Kambiz Haji-Qassemi, 32–35. Tehran: Shahid Beheshti University Press, 1998. [WorldCat]

- Kanda, Yui. “Iranian Blue-and-White Ceramic Vessels and Tombstones Inscribed with Persian Verses, c. 1450–1725.” In The Routledge Companion to Global Renaissance Art, edited by Stephen J. Campbell and Stephanie Porras, vol. 1, 363–77. New York: Routledge, 2024. [Taylor & Francis]

- Kanda, Yui. “Safavid Ceramic Tombstones.” MPhil diss., University of Oxford, 2015.

- Rafeienezhad, Maryam. “Chenar tree of the Emamzadeh Yahya in Tehran, and a comparison with the Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin (in Persian).” Catalog entry in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, April 26, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online. [this website: Persian]

- Sazman-e Farhangi Ejtemaʿi Varzeshi-ye Shahrdari-ye Yazd (Cultural, Social, and Sports Organization of Yazd Municipality). Boqʿeh-ye Seyyed Shams al-Din Nagini dar miyan-e Chaharmenar-e Yazd (The Shrine of Seyyed Shams al-Din Nagini in the middle of Chaharmanar, Yazd), 8 Dey 1403/28 December 2024. [Aparat]

- Sazman-e Farhangi Ejtemaʿi Varzeshi-ye Shahrdari-ye Yazd (Cultural, Social, and Sports Organization of Yazd Municipality). “Yazd yadgari-ye mandegar: Boqʿeh-ye Seyyed Shams al-Din (Yazd, an enduring legacy: The Shrine of Seyyed Shams al-Din).” 16 Mordad 1400/7 August 2021. [farhang.yazd]

- Shahidi Marnani, Nazanin. “If some day a noble soul reads this... Documenting the yadegari of the Tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin.” Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online. [this website: Persian, English translation]

- Sheikhalhokamaee, Emadaldin. “Historical Tombstones of the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin” (in Persian). Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, May 7, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online. [this website: Persian]

Citation: Yui Kanda, “Tombstone of ʿEsmat Ashkamiz [?] Khanom, a daughter of ʿAli-Qoli [?] Beg Shamlu, in the Emamzadeh Yahya at Tehran.” Catalog entry in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, July 12, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.