The Green Solitude of Kohneh Gel: An Ethnography of Religious and Social Life in the Emamzadeh Yahya

(Fall 1402–Spring 1403 Sh / November 2023–May 2024)

Maryam Rafeienezhad

Translated from Persian by Shahrad Shahvand

Contents:

You have come to visit one of the oldest neighborhoods in Varamin, which houses at its heart a modest emamzadeh with a dome made of mudbrick. The Emamzadeh Yahya, while being one of the splendid monuments of the Ilkhanid period [1256–1353] and a tourist attraction for both domestic and foreign visitors, maintains a special connection with the lives of the residents of the Kohneh Gel (کهنه گل) neighborhood. Even after centuries have passed, this historical monument, along with the spiritual figure of the Emamzadeh, holds a special place in the minds and hearts of the people, to such an extent that one can observe the influence of this special connection during celebratory and mourning ceremonies (مراسم, marasem) and rituals (آیین, ayin) held there.

In this essay, I have tried to present to you the results of my recent many months of research, observation, and documentation, which attest to the special connection between the Emamzadeh Yahya and the lives of the people of Kohneh Gel and Varamin. These observations were conducted over five months and during more than fifteen trips to Varamin. The majority of the audience and interviewees were local residents. However, interviews were also conducted with some members of the board of trustees, a local historian, and a specialist in cultural heritage. The methods used in this study include in-depth interviews, observation, participant observation, and occasionally group interviews. One of the most significant outcomes of this study, much of which is presented here visually, is illuminating the special status of the emamzadeh as more than just a religious site and in fact an active symbol of the cultural and historical vibrancy of modern-day Varamin. This status has been shaped by the historical, political, social, and cultural foundations of the city of Varamin and the Kohneh Gel neighborhood.

The Kohneh Gel Neighborhood and the Emamzadeh Yahya

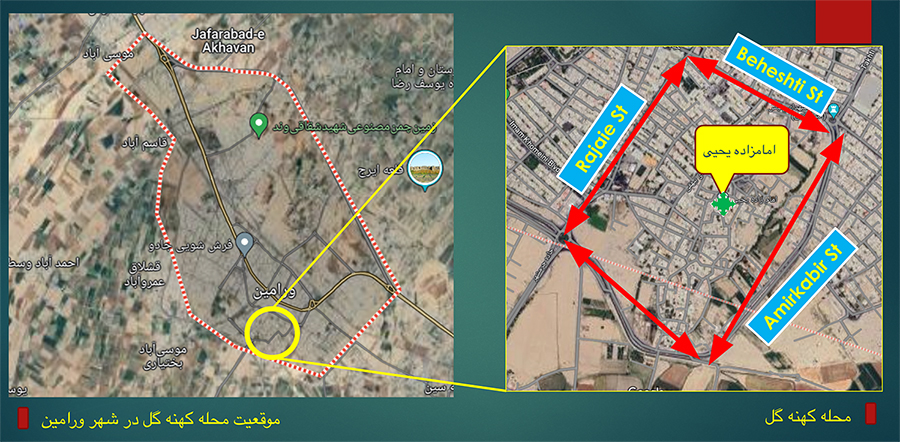

The Kohneh Gel neighborhood is considered one of the oldest neighborhoods in Varamin and is located in the southeast (fig. 1). The neighborhood population is 7,457, of which 3,648 are women and 3,809 are men. The current size of the neighborhood is 770,700 square meters (77 hectares).1 In terms of land ownership, the boundaries of Kohneh Gel are much larger than what is indicated on the municipal map.2 Due to recent migrations, the newly developed areas of the neighborhood in the northwest and parts of the northeast have undergone changes. The historic and old fabric of the neighborhood is in the center, where the historical monument of the Emamzadeh Yahya is also located. Twenty-seven percent of the neighborhood’s population is employed, with most engaged in labor jobs. Various migration waves in the years 1397 Sh/2018–19 and 1400 Sh/2021–22 increased the immigrant population of the neighborhood by forty percent, which is a considerable growth. Different ethnic groups, including Lur, Turk, Kurd, Fars, Gilaki, and Afghan, reside in this neighborhood. Among the migrant groups, the population of the Afghan community is the largest.3

This neighborhood does not have any specific educational or cultural centers, and there is only a health center and Basij base. Adjacent to the Emamzadeh Yahya, there is a small green space and a playground. The buildings surrounding the emamzadeh are mostly residential. According to oral histories narrated by local residents, the neighborhood was once a small village that predates the arrival of the Kangarlu tribes (قبایل کنگرلو).4 The remnants of fire temples and other buildings from the Zoroastrian era have deteriorated and disappeared over the years due to wars and neighborhood expansion. These buildings, once located near the current site of the emamzadeh, were known by the locals as the ‘Gabri Fortress,’ which is now a residential area. According to the accounts of the neighborhood’s long-term residents, due to the lush greenery of this region, people from Varamin and surrounding cities would visit Kohneh Gel on holidays to spend their leisure time.

There are various narratives about how this neighborhood came to house the Emamzadeh Yahya within its heart and how the shrine became the starting point of a deep connection in the religious culture of its residents.5 In his A Social History of Varamin, local historian Mohammad Amini mentions that the presence of madrasas such as the Fathiyeh and Razaviyeh during the fifth/eleventh and sixth/twelfth centuries attracted learned and religious scholars to the Varamin region.6 This can be considered one of the roots of the Shiʿi presence in Varamin and the presence of the Emamzadeh Yahya in this area (see our interview with Mr. Amini here).

Following the martyrdom of Emamzadeh Yahya (d. 255–56/869–70) and the construction of a historical building as his resting place, his popularity and reputation increased. After numerous trips by various Iranian and foreign travel writers, including Madame [Jane] Dieulafoy [d. 1916], and the presentation of this monument in her documentary work, the Emamzadeh Yahya gradually gained international fame.7 As such, the historical monument of the Emamzadeh Yahya is considered one of the renowned attractions of the city of Varamin.

The Emamzadeh Yahya has long been preserved in the oral memory of the people, along with two other sites. According to Mr. Amini, during the period between 1318 Sh/1939 and the 1357 Sh/1979 Islamic Revolution, a religious scholar and mojtahed [high-ranking cleric] named Mr. Taheri provided religious education in Varamin, and his sermons attracted many followers. Regarding holding mourning ceremonies, Taheri issued a fatwa asserting that the setting of the Emamzadeh Yahya was not suitable for rozeh-khani (روضه خوانی, lamentations) or mourning (عزاداری, ʿazadari). Thereafter, some neighborhoods in Varamin, including Kohneh Gel, decided to build hosayniyehs and mosques next to emamzadehs. The Emamzadeh Yahya was one of these blessed places near which a hosayniyeh and mosque were constructed.

To the south of the Emamzadeh Yahya, on the opposite side of the neighborhood’s current hosayniyeh, there is a small square (میدان, meydan) around which a small green space has been created (map). This location is the place of martyrdom—the qatlgah (قتلگاه) or shahidgah (شهیدگاه)—and holds a special place in the oral memory and beliefs of the people. In the past, some Ashura rituals were performed in this location, and according to local belief, Emamzadeh Yahya and his companions were martyred here, and some of his companions were also buried here. According to tradition, the renowned ʿalam (علم, ceremonial standard) of the Kohneh Gel neighborhood would be carried around the neighborhood each year, and its head would be lowered at this spot, the martyrdom site, at noon on the day of Ashura.

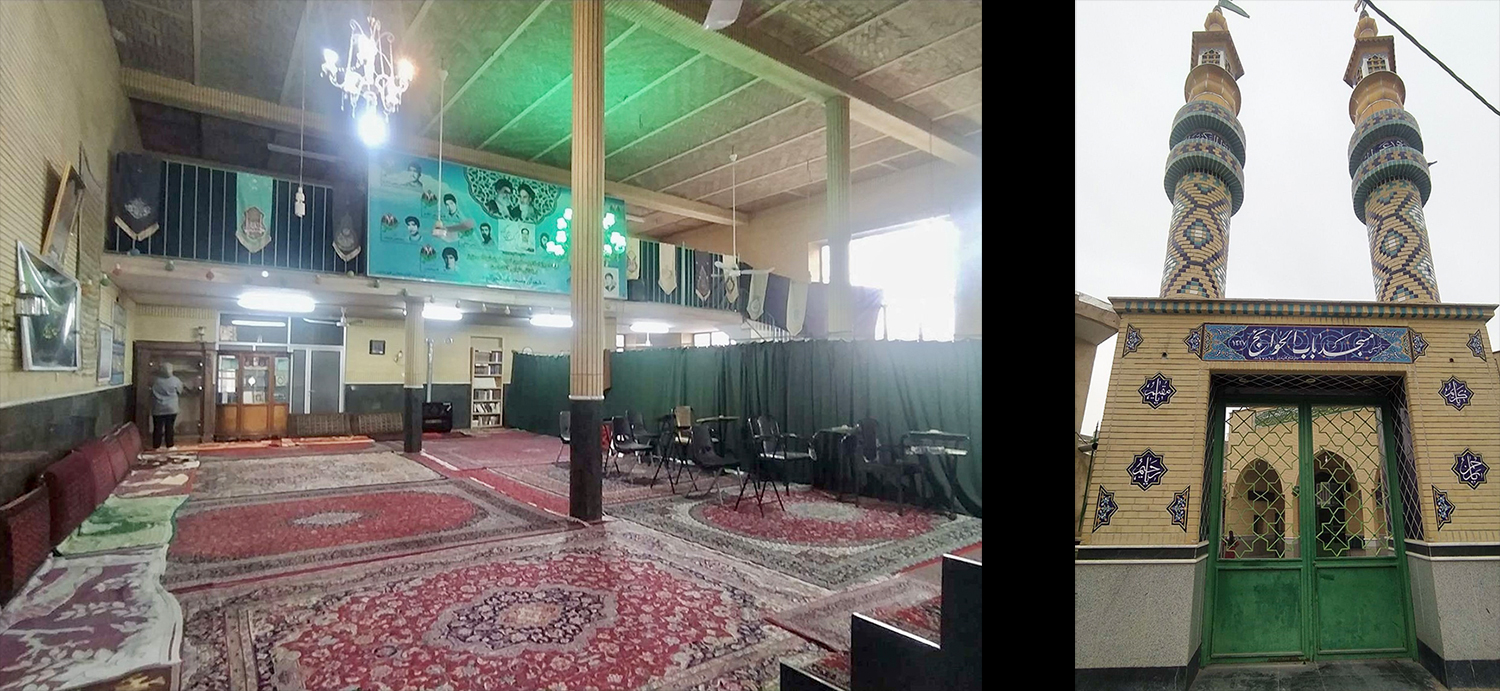

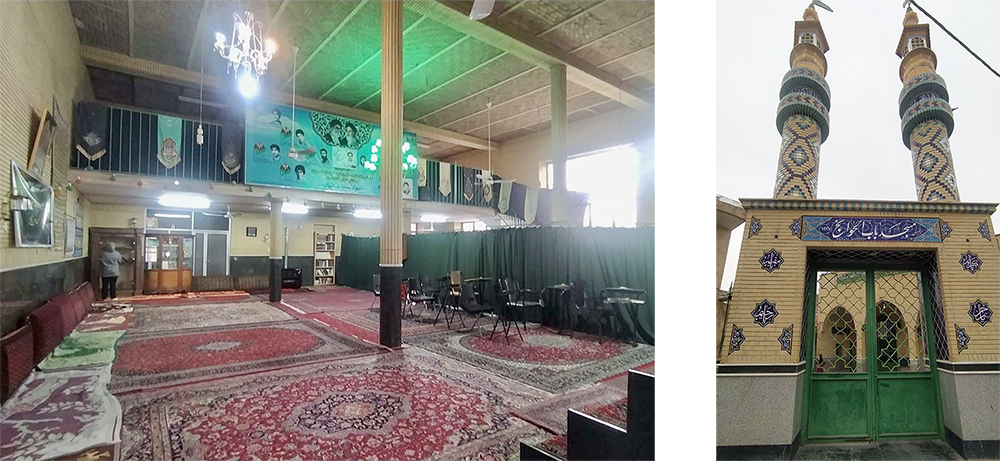

The Masjed-e Bab ol-Havaʾej (مسجد باب الحوائج, Bab ol-Havaʾej Mosque) is also located near the Emamzadeh Yahya and martyrdom site (fig. 2). A benevolent farmer from the Kangarlu tribes built this mosque over a hundred years ago. Later, further lands were added to it, leading to its expansion, and it is now used by the people of Kohneh Gel for holding religious ceremonies.8 The significance of this mosque to the people stems from its once housing the aforementioned ʿalam in a wooden chest in a separate room.

The Kohneh Gel Hosayniyeh (حسینیه کهنه گل) was built later to host Ashura ceremonies, serve nazri (نذری, free food and drink) to the people, and facilitate other religious rites (map) (fig. 3). According to local narratives, following the expansion of the neighborhood and increase in population, the emamzadeh’s space was no longer sufficient to accommodate and receive the mourners and attendees at religious ceremonies. With the construction of the mosque and the hosayniyeh, a closely interconnected triangle was formed for hosting religious rituals and organizing the religious life of the neighborhood’s residents (fig. 4).

Those Who Frequent the Emamzadeh

In general, within Shiʿi religious culture, people have a deep attachment to Emamzadehs, and various beliefs exist regarding the sanctity of these individuals. Some Emamzadehs have very old graves and genealogies that trace their lineage back to the immaculate Emams, and this relationship has granted them a special status and esteem. Therefore, visiting the shrines of Shiʿi Emamzadehs has long been very popular, and despite significant changes in the religious atmosphere of Iranian society, many people still continue to visit their beloved emamzadehs. The Emamzadeh Yahya is one such revered and beloved religious site in Varamin.

1. Women

Women are the heart and soul of the emamzadeh. They are the most active and visible group among the pilgrims (زائرین) to the shrine, and despite spending a lot of time on household duties, they continue to have a meaningful presence at the emamzadeh both during the week and on holidays. Most women living in the Kohneh Gel neighborhood are housewives. Some of them have skills in sewing and carpet weaving, but they practice these crafts at a very basic level as hobbies and do not generate considerable income to alleviate financial difficulties. No specific social or educational services have been allocated for this neighborhood, and the Emamzadeh Yahya is the only place that provides them peace, eases their burdens, and offers them a space for social interaction with other women.

These women can not only engage in religious practices they believe in, such as supplicatory prayers (دعا, doʿa), sofreh-ye salavat [a group ceremony held on a sofreh, or tablecloth] and performing namaz (نماز, obligatory daily prayers), but they can also find renewed energy for returning home through friendly conversations (fig. 5). Some women sometimes bring homemade products, such as dried fruits and nuts, to sell at the emamzadeh for other visitors to purchase. In many interactions, the women do not initially know each other, and their relationships begin at the emamzadeh. Among these visitors, Afghan women form a significant group actively involved in holding ceremonies. Their presence is notable, both in performing namaz and individual religious rituals and in group practices such as Doʿa Tavasol and Ziyarat Ashura (for descriptions of these rituals, see Special Times and Ceremonies ).

2. Children

From the very early days of my trips to Kohneh Gel, perhaps even during the first visits, the presence of children at the Emamzadeh Yahya was surprising to me. At the entrance of the emamzadeh, there is a park where children are usually busy playing (fig. 6). This area was added to the entrance space as a green space in recent times (see Site Tour). Children’s play often unintentionally extends into the courtyard of the emamzadeh (fig. 7). Older children tend to play soccer in the entrance area, while the younger ones find various ways to entertain themselves, from tag and haft-sang (Seven Stones, a traditional game) to hide-and-seek. The diverse space of the emamzadeh and the large courtyard provide ample room for them to play, and the lively atmosphere of children’s games is always present around the shrine. These children mostly live in the Kohneh Gel neighborhood and have chosen this place for play independently, without their parents. Other children visiting the emamzadeh with their parents occasionally also join them.

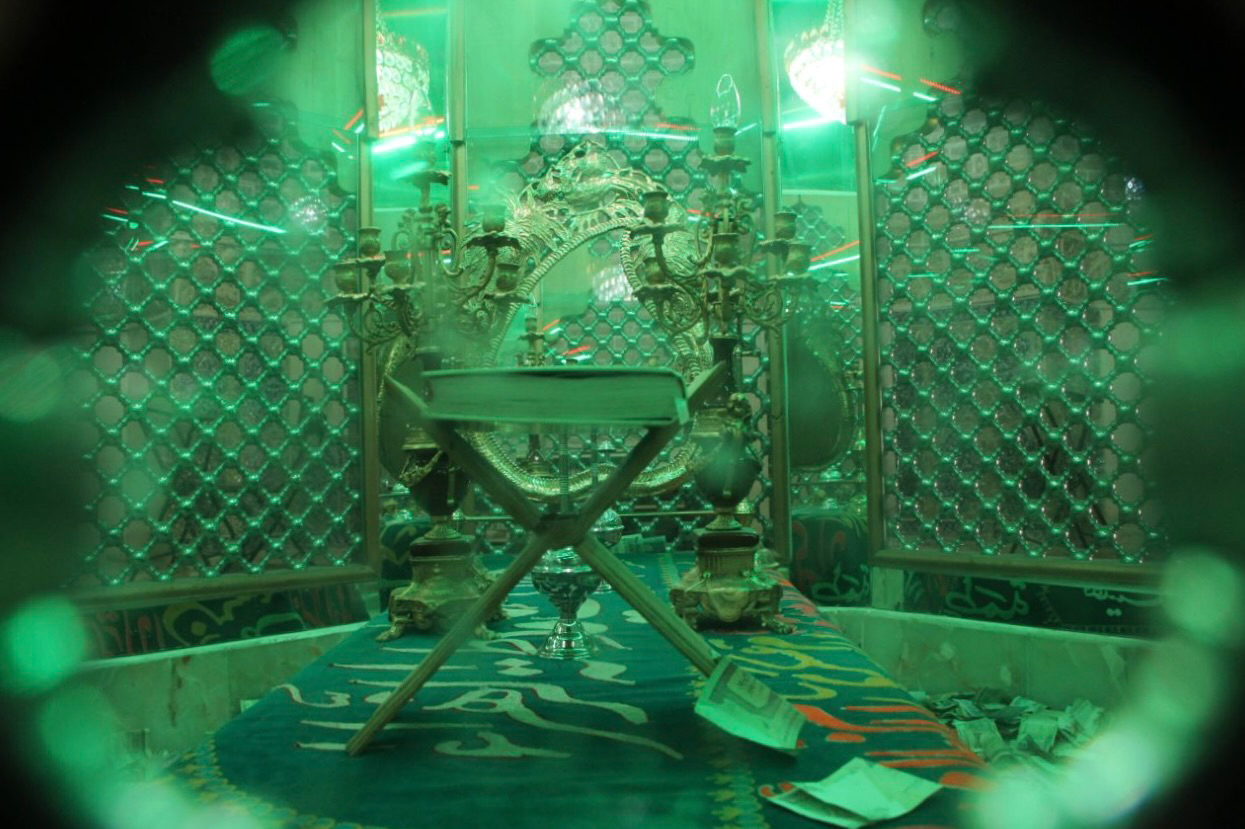

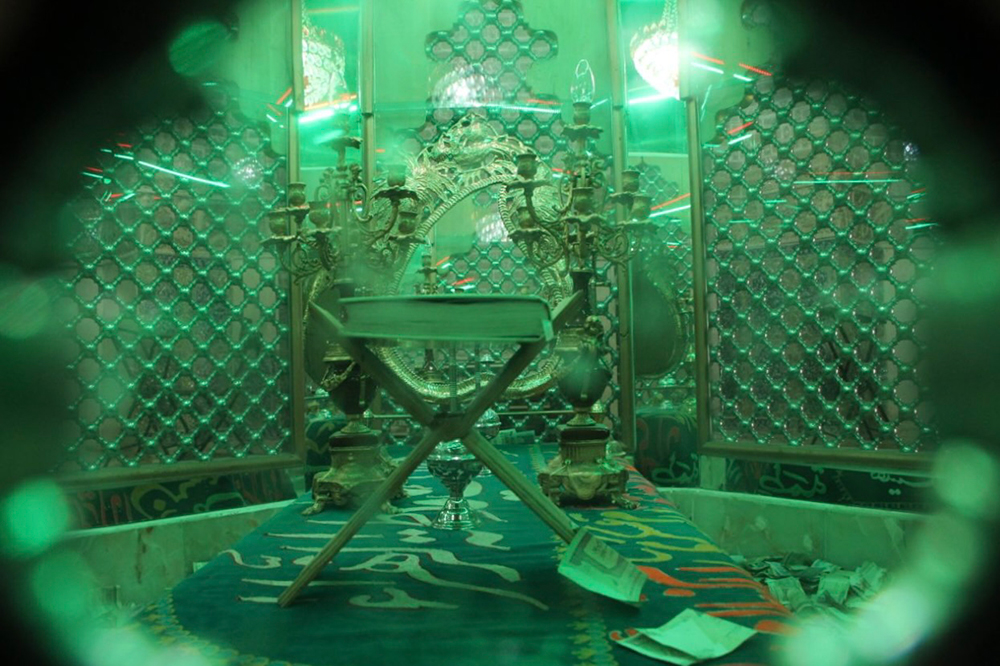

Another group of children who come with their parents are captivated by the wonder of the space and how different it feels from other public places, especially when they reach the small tomb (آستان, astan) of the Emamzadeh (fig. 8). The green-colored room [zarih, ضریح, screen around the cenotaph] adorned with banners (parcham, پرچم) and twinkling colored lights draws them into the imaginary world of stories. Curiosity sometimes takes over, and by touching the zarih and pressing their faces against it to see what is inside, they become more diligent in their search to discover more about the emamzadeh. Playing with books, mohr (مهر, clay tablets for prayer), and strands of tasbih (تسبیح, prayer beads) are also among the favorite hobbies of the younger children. Some attempt to imitate their parents by performing namaz or pretending to engage in doʿa. At times, they even start reciting phrases resembling Arabic words and Qurʾanic verses, which are often quite gibberish. Overall, being in the atmosphere of the emamzadeh is a distinct, intriguing, and entirely social experience for these children. It is social in the sense that they meet many other children like themselves, even from other areas, with whom they can play, and they also encounter different individuals engaged in religious and spiritual behaviors that are new to them.

3. Visitors to Graves

Visiting graves is a cultural practice in Iran that has been observed from the past to the present across the country according to the local customs of each region.9 People typically visit their deceased relatives at the end of the week or during national and religious occasions, sharing some moments of their lives with them. During these rituals, distributing food as charity (nazri) is a common practice. Since the Emamzadeh Yahya is considered fundamental to the historical and religious identity of the Kohneh Gel neighborhood, being buried in such a place is highly regarded locally, and this desire to be interred near the Emamzadeh is often expressed in conversation. A large piece of land has been endowed as the courtyard of the emamzadeh, where residents of Kohneh Gel bury their deceased and visit their graves on weekends (figs. 9–10). With the growing population, the courtyard of the emamzadeh no longer has enough space for the burial of all of the neighborhood’s deceased, and priority for burial is given to the native and long-term residents of Kohneh Gel.

People hold ceremonies for their deceased by distributing food (nazri), reciting doʿa and zekr (ذکر, repeated phrases and invocations), and sometimes someone plays the ney (a traditional flute) (aud. 1). On special occasions, such as Father’s Day or Mother’s Day, many graves are covered with flowers, and individuals visit their loved ones to find peace and offer flowers and recite Fateheh prayers (ذکر فاتحه). Among the residents of the Kohneh Gel neighborhood, the Kangarlu tribes might hold the largest share of graves at the emamzadeh due to their social power, the longevity of their historical presence in the neighborhood, and their management of the emamzadeh (fig. 11).

Audio 1. A man playing ney beside the graves of the deceased. Recording by Maryam Rafeienezhad, 2023.

4. Teenagers

Teenagers often come to the Emamzadeh Yahya to meet their peers, and the shrine serves as a space for this group’s social interaction, albeit with some limitations. Given that Kohneh Gel lacks suitable public spaces for social exchanges, the emamzadeh provides teenagers with the opportunity to meet peers and members of the opposite gender while also performing religious obligations. Many teenagers in the neighborhood have left school due to extreme poverty, work labor jobs to help support their families, and spend their weekends at the emamzadeh chatting with their peers. Some of them, despite dressing in completely modern styles and not adhering to traditional or religious beliefs, accompany their parents in holding doʿa and nazri. Based on this researcher’s observations, the Emamzadeh Yahya is one of the most important places for teenagers to engage in social interaction and role-play, and adopting various roles during ceremonial rituals is highly significant for them.

5. The Elderly

This group has the strongest connection and sense of belonging to the emamzadeh. When you talk to them about the emamzadeh, their eyes light up, and they can speak for hours about the spiritual status of the emamzadeh and its power to heal the sick. Their belief in the emamzadeh takes on a different shape and meaning, something tied to their identity. They have lived their lives with the emamzadeh, it is present in their memories, and if health issues and the challenges of old age permit, they have the highest participation in both group and individual religious programs.

6. Tourists

Tourists visiting the Emamzadeh Yahya can be divided into several different groups. One group consists of foreign tourists who visit the emamzadeh as part of their tour of Tehran’s historical sites, or they are researchers in various fields who come to the emamzadeh due to its historical, social, cultural, religious, and artistic dimensions (figs. 12–13). Domestic tourists are also divided into several categories: one group consists of academic researchers, including students accompanied by their professors or university researchers and professors. Another group consists of ordinary people who have no knowledge of the splendid Ilkhanid-era shrine or the personality (historical figure) of Emamzadeh Yahya and who visit simply to see Tehran’s historical attractions as part of tours organized by tourism companies or cultural centers. Another group of visitors includes pilgrims who, while traveling to Qom and Rey for pilgrimage, also make a stop in Varamin or come specifically from other cities to visit the Emamzadeh Yahya. It is also worth mentioning that groups from schools occasionally come to visit this historical site.

People’s Beliefs and Their Connections with Emamzadeh Yahya

1. Ziyarat

Ziyarat (زیارت, pious visitation or pilgrimage) refers to visiting someone with the intention of honoring or venerating them. A person who undertakes such a visit is called a zaʾer (زائر, pilgrim). Many people, from both near and far, come to visit the Emamzadeh Yahya and perform the rituals and practices associated with ziyarat. The emamzadeh holds a special and sacred place in the beliefs of the neighborhood’s residents and is intertwined with their sensory perceptions. To understand this point, it suffices to observe their behavior at different times of the visit, beginning with their entrance into the emamzadeh. At first, they perceive the sacred with their eyes. Their eyes light up at the sight of the dome and tomb of the Emamzadeh, reflecting a feeling of familiarity and closeness akin to meeting a dear person. Then, their posture changes as they lean slightly forward in a gesture of respect, bowing their heads with eyes cast downward, because they perceive themselves in the presence of a sacred and higher entity. They then recite a salam (greeting).10 After reaching the steps of the eyvan [the vaulted space on the north façade of the tomb], touching the earth of the emamzadeh, and kissing the walls of the eyvan, they are confronted with the main threshold of the tomb while continuing to recite their greetings.

These sensory connections (seeing and touching)—combined with acts of bowing, kissing, and reciting zekr—intensify step by step, and as pilgrims approach the tomb of the Emamzadeh, their emotional perception reaches its peak. By touching the zarih and smelling the rosewater in the air, the pilgrim reaches the closest possible point of proximity to their beloved. Their sensory perceptions crystallize, and at this moment, pilgrims may cry or loudly call out the name of the Emamzadeh or even God, or recite doʿa in a loud voice, imbuing the emamzadeh with a distinct spiritual atmosphere (fig. 14).

Some pilgrims, and they are not few, speak to the Emamzadeh in Persian in a very simple manner, expressing their wishes, pains, and needs. Another group, after unburdening themselves, begins to perform a cycle of namaz (fig. 16). There are also those who spend hours reciting doʿas from books that are placed on separate bookshelves for men and women in the tomb. The resonance of the Qurʾanic recitation by some pilgrims, who have greater Qurʾanic literacy and can recite the Qurʾan with intonation, adds to the spiritual atmosphere of the emamzadeh and breaks the silence. One of the lengthiest prayers is the namaz of Jaʿfar Tayyar, which very few perform (one can often discern when a pilgrim is performing it by the extended duration of their namaz). These religious rituals can vary depending on the day. For instance, it is customary to recite Ziyarat Ashura on Thursdays, Doʿa Tavasol on Tuesdays, and Doʿa Nodbeh on Fridays. During various religious occasions, different doʿas are recited, and depending on whether the occasion is celebratory or in mourning of the Infallible Emams, the manner of reciting the doʿa and zekr by the people or the eulogist (مداح, maddah) changes.

The common belief among all pilgrims is their faith in the intercessory power of Emamzadeh Yahya and his sacred status in seeking cures for their ailments and problems. This relationship is unique. In a spiritual space, a material object transforms into a means of connection, forming a fusion of the material and the spiritual that defines the existential link between the Emamzadeh and the pilgrim.11 In other words, through spiritual belief and behaviors that engage all of their senses, the pilgrim uses a material tool like money or nazr (food and edibles) to seek their needs (حاجت, hajat) from the Emamzadeh (see fig. 15). As observed during fieldwork, several beliefs are formed in this connection and can be categorized into two main groups, spiritual needs and material needs:

- “The Emamzadeh heals the sick.” (material need)

- “The Emamzadeh lifts our spirits and visiting him lightens our hearts.” The sacred serves as psychological therapy. Talking and communicating with him, and expressing one’s difficulties, temporarily eases mental and emotional burdens. (spiritual need)

- “The Emamzadeh grants wishes.” (material need)

- “The Emamzadeh has a status in which he is aware of everything.” (spiritual need)

- “The Emamzadeh protects us from evils and troubles.” (both material and spiritual needs)

When it comes to people’s beliefs in and relationship with the Emamzadeh, concepts like intercession (شفاعت, shafaʿat), well-being, fulfillment of needs, and protection play a central and foundational role. The root of the connection between material and spiritual needs in the relationship between the pilgrim and the Emamzadeh lies in the concept of seeking assistance. This need can be material, such as a person seeking a physical need like healing for the sick. Or, it can be purely spiritual, focusing on mental peace and well-being, like performing various types of namaz and doʿa. Or, it can be a combination of both needs, meaning that a person chooses to have a spiritual connection with the Emamzadeh to achieve peace and security in their material world, believing that the Emamzadeh is a source of holiness connected to God and being close to and loving him provides protection against evils.

2. Vow

The term nazr (نذر, vow) literally means “that which one obligates oneself to do, or what one commits to upon the condition of something.” This means that, by making a nazr, a person commits themselves to fulfill it upon the realization of their wish. The customs and rituals of making nazr and nazri exist in various forms across different religions and have historically been prevalent in diverse cultures. One of the places where these rituals are performed is religious sites, such as the Emamzadeh Yahya.

The customs of nazr at the emamzadeh are carried out in various forms and intentions and at different times. One of the signs of a nazr, often observed in the women’s section, are the tasbihs tied to the zarih after a pilgrim recites a zekr and states their wish (fig. 17). During this process, the pilgrim presents whatever they desire to God through the Emamzadeh, invoking him as a sacred intermediary for fulfilling their request. By stating their wish in Persian or chanting “O Emamzadeh Yahya,” they present their request, tie a tasbih or string to the zarih, and do not untie it until their wish is granted.

Many types of food offerings, both local and non-local, are common at the emamzadeh and vary depending on different religious occasions and national celebrations. During the month of Moharram, for example, the ceremonies of the first few days are usually held in the evenings. The distribution of nazri occurs at dinner time, following the completion of rituals such as chest-beating (سینهزنی, sineh zani) and mourning in the neighborhood associations (هیئت, heyʾat). Common drink nazri include sherbet, tea, milk, and chocolate milk. Meal offerings traditionally feature dishes like chelo khoresht (rice with stew) with qeymeh and qormeh sabzi, as well as abgusht, halim, sholeh zard, and ash-e reshteh, which have long been popular among the offered foods. The midday meal on Ashura is one of the customary offerings during religious rituals, especially in Varamin. As noted in interviews with the neighborhood residents, it predominantly consists of chelo khoresht with qeymeh.

The distribution of nazri is also observed on other days. For example, during the Thursday morning recitation of Ziyarat Ashura, breakfast is often provided and distributed by charitable individuals and consists of dishes like lentil soup, halim, bread with cheese and herbs, and omelets (fig. 18). On days of religious celebrations, such as mabʿas (27 Rajab, مبعث, the day marking the beginning of Prophet Mohammad’s mission) or mid-Shaʿban (15 Shaʿban, the birthday of the Twelfth Emam), the different areas of the emamzadeh are filled with offerings of sweets, chocolates, halva, dates, and fruits. During grave visitation on weekends, when people come to see their departed loved ones, it is customary to distribute offerings such as dates, halva, and fruit (fig. 19). [For these rituals and occasions, jump ahead to Special Times and Ceremonies]

3. Sacred Objects (ʿalam)

All objects used during religious rituals and ceremonies are considered sacred and valuable, but some are particularly special because they contain a sacred story or belief. One historical belief is the sanctity of an ʿalam long revered by the local population and Kangarlu tribe.12 This ʿalam features a wooden shaft and dark-colored metal blade shaped like a cross (fig. 20). Before the construction of the mosque and hosayniyeh, the ʿalam and ʿalamat (a horizontal ceremonial standard with many finials) of the Kohneh Gel heyʾat were stored inside the Emamzadeh Yahya next to the zarih (see Ritual Objects). After the mosque (Masjed-e Bab ol-Havaʾej) and hosayniyeh were constructed, the ʿalam was re-housed in the mosque in the room known as the ʿAlam Room, while the ʿalamat was stored within the Kohneh Gel Hosayniyeh (see no. 49). The historical and ongoing respect for the Masjed-e Bab ol-Havaʾej derives from its role in safeguarding the ʿalam in a wooden box and preserving this box in the ʿAlam Room (fig. 21). According to accounts from the older women of the neighborhood as well as Mr. Amini (the aforementioned local historian), rituals known as namaz-e hajat (the supererogatory prayer for need) were traditionally conducted in the ʿAlam Room. Some older residents continue to perform these rites during the Nights of Qadr [when the Qurʾan was first revealed to the Prophet Mohammad] and the early ten days of the month of Moharram.

This ʿalam carries many stories and legends, which can be heard from people with excitement and passion. They believed that this ʿalam was capable of healing, which is why they made many offerings to it. On the Day of Ashura specifically, the ʿalam was carried along a designated path on the shoulders of an individual. According to some elders, however, the movement was believed to be the result of the ʿalam itself. In other words, people believed that it was the spirit and energy of the ʿalam that caused its movement. After the settlement of the Kangarlu tribes and construction of the mosque, the metal part of the ʿalam was kept inside the aforementioned box (see fig. 21).13 This renowned and respected ʿalam went missing in the late 1340s Sh/1960s. There are many stories about the reason for its disappearance, but people attribute it to competition between different tribes in Varamin wanting to keep the ʿalam to themselves.

Today, the box that contained the ʿalam and the room in the Masjed-e Bab ol-Havaʾej where it was once kept continue to be revered by some individuals. Many women go there to perform prayers during religious occasions. Among their conversations and those of other older individuals, stories about their wishes being granted in the ʿAlam Room are noteworthy.

Management of the Emamzadeh Yahya

The Emamzadeh Yahya is managed by several groups and institutions. The part that is in constant contact with the people is the board of trustees (heyʾat-e omana, هیئت امنای), which is trusted by the community. The Endowment Organization (Owqaf) and Cultural Heritage Organization (Miras) also oversee the financial affairs and manage the historical and cultural aspects. The way that emamzadehs are managed and administered has always been a challenge. Since the Kangarlu settled in Kohneh Gel and gained power, there has always been a debate about who should be responsible for managing the emamzadeh.

1. The Kangarlu Tribes and the Board of Trustees

The ethnic identity of the Kohneh Gel neighborhood is primarily shaped by the Kangarlu. These tribes were relocated from western Iran to Varamin during the reign of Fath ʿAli Shah Qajar [r. 1797–1834].14 As the Kangarlu gained power in Kohneh Gel (the tribe included the four clans of Ilchi, Bilchi, Purchi, and Qareh Khan Begloo), the emamzadeh became a symbol of religious identity and an integral part of the social power structure, perhaps even the most important part.15 In the social system of Iranian emamzadehs, shrines receive material offerings from the people in their interactions with the Emamzadeh, and their management can lead to social and economic power.

According to accounts from the older residents of the neighborhood and a member of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s board of trustees, in the past, the rooms around the octagonal tomb were under the control of the Kangarlu. These rooms were used to store the bodies of the tribe’s deceased before their transfer to Qom, and through their presence in these rooms, the tribe consolidated management of the emamzadeh.16 This management involved handling financial affairs, offerings, and endowments donated by benefactors, overseeing construction and unforeseen repairs, managing the internal affairs of the emamzadeh, supervising the duties of the khadem (day-to-day custodian or ‘servant’) and motevalli (caretaker, manager), monitoring the sale of graves, coordinating and providing facilities for the emamzadeh’s daily activities and special occasions, and, after the Islamic Revolution, liaising with the Endowment Organization and Cultural Heritage Organization.

2. The Khadem

The custodian (خادم, khadem) of the emamzadeh handles an essential part of tasks related to the site. In the mornings, she turns on the lights of the emamzadeh and sweeps the courtyard and interior of the sanctuary (fig. 22). She is responsible for constantly monitoring the emamzadeh to ensure that no harm comes to the premises. During special occasions, such as mourning or celebrations, she assists in preparing tea, refreshments, and food. For memorial services, she must bring chairs from storage, arrange them, and serve the attendees (see fig. 10). Her duties also include cleaning the restrooms, maintaining the emamzadeh’s small garden, and tidying the graves. At noon and in the afternoon, she turns on the emamzadeh’s loudspeaker to broadcast azan (اذان, the call to prayer) from a small radio (vid. 1).

Video 1. The khadem sweeping the courtyard of the Emamzadeh Yahya. Video by Maryam Rafeienezhad, 2024.

Over the years, the Emamzadeh Yahya has had many khadems. One of the first was Mashdi Hossein Gharibian, whom people affectionately called Mash Hossein.17 He had migrated from Esfahan to Varamin and served as a beloved and respectable khadem of the emamzadeh from the late 1340s Sh/1960s until 1367 Sh/1988. Following Hossein Gharibian, Maryam Khanum and her husband Ostad Mohammad took on the responsibilities. Maryam Khanum served as the khadem of the emamzadeh from 1369 Sh/1990 until about five or six years ago, after which Massumeh Khanum and her husband, the current custodians, were appointed to this position. In the past, the selection of the khadem was handled by the board of trustees and motevalli of the emamzadeh, but now the Endowments Organization also plays a role. The khadem’s salary is paid by the Endowments Organization, but the board of trustees continues to supervise the position as they did in the past.

Special Times and Ceremonies

Visiting the emamzadeh at different times of the year and observing a variety of special ceremonies were crucial to this research. The neighborhood residents connect with the emamzadeh at specific times, and through rituals performed there, their lives gain meaning. Here, I summarize my observations of specific days, rituals, and holidays.

1. Cold Winter Days and Spring Days

Some of my visits to the Emamzadeh Yahya occurred on extremely cold winter days, to the extent that I would hurry from the entrance to the tomb (astan) to warm up inside. On one such cold day, I witnessed a different view of the emamzadeh; it seemed as if it had wrapped itself against the intense cold (fig. 23). In fact, the khadem (custodian), under the guidance of the board of trustees, had devised this solution to prevent the cold from entering the astan, covering the facade with a large sheet of plastic. Despite the cold, a group of locals, some of whom were Afghan, came to visit the emamzadeh and the graves. Elderly visitors, who faced more challenges in such weather, were fewer in number. The restrooms, located at the end of the emamzadeh’s courtyard, did not provide warm water suitable for performing ablutions (vozu), hence most visitors would suffice with reciting doʿa and ziyarat.

In spring, the emamzadeh’s surroundings and courtyard were greener and more beautiful. Now, even the elderly could visit the emamzadeh whenever they wished. While sitting in the eyvan, the sounds of birds chirping on the branches of the emamzadeh’s trees filled the entire space (vid. 2).

Video 2. Spring and the sounds of birds chirping in the courtyard of the Emamzadeh Yahya. Video by Maryam Rafeienezhad, spring 2024.

2. Ziyarat Ashura

A few hours before the event begins, benefactors responsible for the nazri (charitable food and drink) and members of the board of trustees arrive at the emamzadeh and perfume the space with rosewater. These sorts of tasks are part of preparing the emamzadeh for holding religious rituals. The chanting of elegies (مداحی, maddahi) plays [through loudspeakers], and the crowd gradually grows. As more people arrive, they sit in rows, one behind the other. The elderly lean against the wall, and some sit on chairs. The benefactor, along with some neighborhood residents, prepares the breakfast nazri in the kitchen. The maddah (eulogist) is also present.18 Others set up and check the sound system, and after a while, the maddah begins by welcoming the attendees and reciting short introductory rozehs (lamentations) in the form of poetic eulogies in praise of the Immaculate Emams. These serve as a prelude to the main doʿa (supplicatory prayer), the Ziyarat Ashura (زیارت عاشورا) (fig. 24). Typically, there are fewer women than men in attendance.

The maddah narrates some reports about the month of Rajab and its significance [it was Rajab at the time]. Then, he starts with the supplicatory expression “السلام علیک یا ابا عبدالله” (peace be upon you, Oh Aba Abdellah [Emam Hosayn]) and proceeds with reciting the doʿa, emphasizing the name of Emam Hosayn whenever it appears [listen to a recitation on Aparat]. He asks the people to repeat it loudly with him, place their hands on their chests, and kneel while reciting the zekrs (repeated invocations from the Ziyarat). He then tells them that, after death, when they are alone in the grave, it is Hosayn who will help them and intercede on their behalf. At this moment, the sound of men’s weeping becomes audible. The maddah continues the doʿa and asks the people to prostrate. Everyone takes their mohr (clay tablet for prayer), and another part of the doʿa is recited. As the doʿa continues and the maddah emotionally pleads “Call on Aba Abdellah [Emam Hosayn] as if you are adoring your child or loved one” (آنچنان اباعبدلله را صدا کن انگار قربان صدقهی فرزندت یا عزیزت میروی), the sound of women’s weeping intensifies. The maddah asks the people to call on Hosayn more loudly and raise their hands. Everyone shifts their sitting position toward the qibla (direction of prayer) and prays with raised hands. Throughout the doʿa, the maddah attempts to infuse more sorrowful passion into the recitation and encourages people to express their sorrow more intensely along with him. This is one of the major tasks of a maddah: to lead the people during the doʿa, encouraging them to participate with empathy and heightened religious fervor.

After the completion of the doʿa, some men lay out disposable plastic tablecloths (fig. 25). Tea is also served in disposable plastic cups along with sugar cubes. Bowls of lentil soup are then distributed, accompanied by plastic spoons. Pieces of barbari bread are also handed out. I sit at the sofreh [in reference to the ‘table’ of food] and taste the lentil soup nazri, which is much better than the typical lentil soup in Iranian cuisine because it has meat. The food is tasty and perfectly cooked. The benevolent individual who prepared the nazri comes and joins us for breakfast, and after finishing the meal, everyone wishes for the acceptance of his nazr (vow). They then clean up together.

3. Maʿbas

Maʿbas (27 Rajab, مبعث) is of great significance to both Shiʿi and Sunni Muslims, as it marks the day when the Prophet Mohammad was chosen as the Messenger of God. On that day, as always, I was observing people and taking notes from the corner. Many visitors were entering the tomb, reciting zekr while bowing, and then proceeding to recite doʿa beside the zarih. Most of them had brought food or sweets as nazri, and children were responsible for distributing the nazri and charitable foods (kheyrat). When the adults offered the nazri, they would first wish each other a happy Eid (عید). The presence of Afghan migrants was also notable; some of them were Sunni and engaged in performing namaz. It seemed that Eid-e Maʿbas held more importance for them than for the other locals (for Iranians, the most significant Eid is Nowruz). They [the Afghans] had put on their new and beautiful clothes and were eager to outdo one another in saying the Eid greeting, whereas the behavior of the non-Afghans appeared more reserved and less lively and enthusiastic. In response to my question about celebrating Eid-e Maʿbas, one Afghan woman explained, “Eid-e Maʿbas and Eid-e Qorban (Eid al-Adha) are our most important Eids. We are as joyous and observant of the tradition on these two days as you are during Nowruz.” As I was listening to her, I noticed that her hands were beautifully decorated with henna [link in English].19 The visits to the graves were also very lively, with most of the neighborhood residents present and distributing charitable food, including sweets, fruits, and decorated halva (fig. 26).

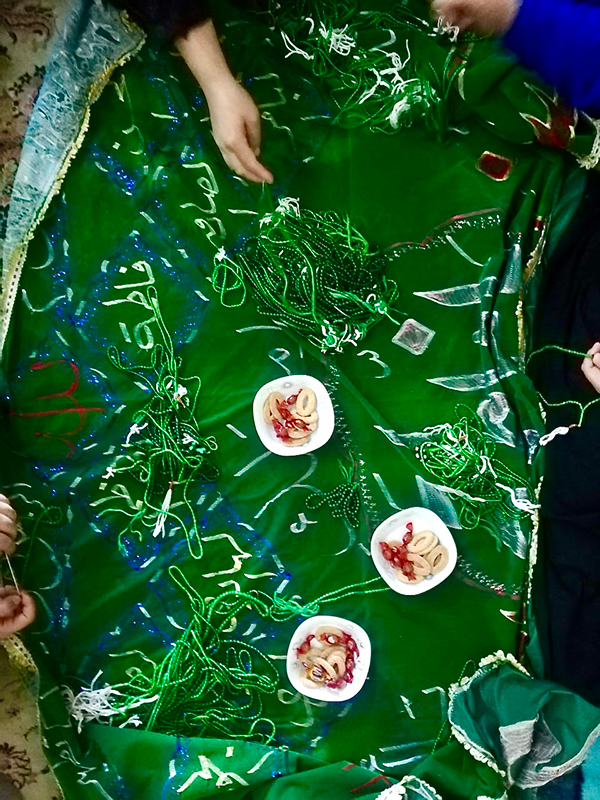

4. Sofreh Salavat

Another ritual I was able to observe during my time at the Emamzadeh Yahya was the Sofreh Salavat (سفرهی صلوات), a practice particularly carried out by women and primarily Afghan women from the neighborhood and some Iranian women. A few hours into the morning, four Afghan women entered the tomb, carrying nazri foods, green fabrics, and a thermos of tea. It was absolutely clear that they were planning a special ceremony. I quickly joined the group and asked about the procedures while helping them prepare.

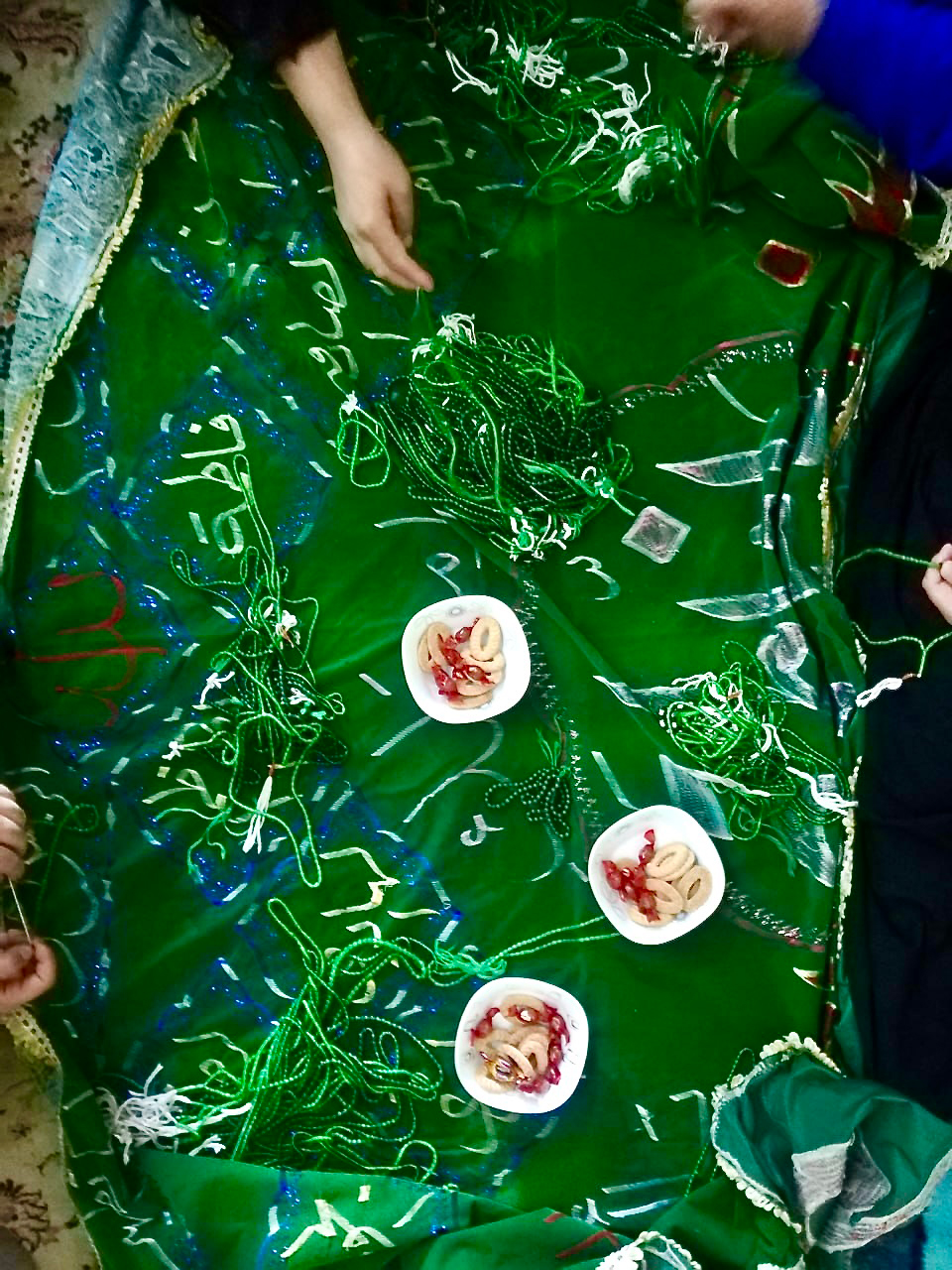

The ceremony begins with spreading out a green cloth (sofreh) embroidered with the names of the Fourteen Infallible Ones and the salavat invocation [Oh Allah, bless Mohammad and the family of Mohammad]. Then, they place a large number of tasbih sets on the cloth (sofreh), each set consisting of six tasbihs tied together at the top with thread. Once the recitation of the salavat is completed on each tasbih set, they wrap it up and place it in a basket to save space. In addition to the baskets of tasbih for counting the salavat, tea, sweets, chocolates, and homemade donuts (pirashki) are also placed on the sofreh (fig. 27).

While reciting the salavat, the women hold the tasbih set in such a way that the tasbihs for already counted salavats do not get mixed with the others. In other words, they hold the strand being counted in one hand and the rest in the other. The person who has a wish makes a vow (nazr), and the counting of the salavat begins (fig. 28, vid. 3). For each wish or intention (نیت, niyat), fourteen thousand salavat must be recited in a cycle. One of the women explained to me that a person can even make a wish from afar and join the group in counting/reciting salavat. Once one full cycle of counting/reciting is completed, another individual with a different wish can begin the next round. This way, the ceremony can last several hours. The number of participants gradually increases, and after an hour, our group of six grows to fifteen. After the ceremony concludes, the women enjoy tea, donuts, and chocolates while engaging in conversation.

Video 3. Sofreh Salavat ceremony. Video by Maryam Rafeienezhad, February 2024.

One of the notable aspects of this ceremony for me was the women’s chats during the performance of the zekr. Alongside reciting the zekr and performing religious ritual, social interactions, greetings, and even becoming acquainted with a new person like me occurred simultaneously, which was quite remarkable. This is different from other religious rituals during which people remain silent and do not talk to one another, such as Ziyarat Ashura.

5. Nimeh Shaʿban

On the snowy morning of Nimeh Shaʿban (15 Shaʿban, نیمهی شعبان, the birthday of the Twelfth Emam), I arrived at the emamzadeh, and from the entrance, I saw some men who were mostly relatives of the board of trustees carrying sound systems into the courtyard.20 The entrance area of the building was decorated with colorful and beautiful fabrics, as well as strings of colorful lights (fig. 30). Banners (parcham) with the inscriptions ‘Ya Mahdi’ [the Twelfth Emam] and ‘Ya Aba Saleh’ were also hanging from the walls.

As I climbed the stairs, I saw a few people in the kitchen preparing tea and hot chocolate. The scent of incense filled the air of the tomb. Men who sat in the men’s section were mostly elderly or middle-aged. In the women’s section, a few women were sitting in a corner, waiting for the ceremony to begin. After the sound system was adjusted, a maddahi was played, and about fifteen minutes later, the religious songs (moludi-khani) sung for birthday celebrations began. The maddah started with zekr-e shaʿbaniyeh (a prayer recited during the month of Shaʿban), which included three zekr. After, a younger maddah took over, singing joyful poems in praise of Emam Mahdi with rhythm and melody, encouraging the audience to repeat and clap along (vid. 4). The men sang and clapped more enthusiastically. Meanwhile, hot chocolate and sweets were distributed, and the attendees were served. The ceremony lasted about an hour, and cheerful poems like this were sung:

From the ocean of velayat, the Creator has brought forth a jewel / Or from the constellation of emamat, a moon has emerged

A sun has appeared from the prophetic heavens / Blinding the eyes of those like bats

خالق از بحر ولایت گهر آورده برون/ یا که از برج امامت قمر آورده برون

از سپهر نبوی گشت عیان خورشیدی/ که ز خفاشوشان دیده درآورده برون

Video 4. The sounds of the birthday celebration of mid-Shaʿban in the north courtyard of the Emamzadeh Yahya. Video by Maryam Rafeienezhad, February 25, 2024.

6. Doʿa Tavasol

In the afternoon of Nimeh Shaʿban, Afghan women gathered and set up a sofreh salavat. After the salavat recitations, they decided to read the Doʿa Tavasol (دعای توسل; tawassol) [Wikishia; listen to a recitation on Aparat] (fig. 31). Everyone sat together, and Massumeh Khanum (the khadem) began to recite the Doʿa Tavasol. The part of the doʿa that everyone needs to repeat together was recited loudly by the women: “یا وجیها عندالله اشفع لنا عندالله ...” (O Esteemed One in the sight of God, intercede on our behalf before Him). At the end of the doʿa, the women turned towards the east and west while standing, and then towards the qibla, repeating a zekr.

7. Estekhareh ba tasbih

During one of my visits to the Emamzadeh Yahya, I observed a special ritual called estekhareh ba tasbih (استخاره با تسبیح; divination with prayer beads) performed by an elderly Afghan woman who mentioned that this practice is common among women in religious gatherings. That day, I was engaged in conversation with a woman who was sharing her feelings about the Emamzadeh, expressing how overwhelmed with difficulties she was and how coming here brought her peace. The older Afghan woman, who was from Kunduz and whom I often saw performing namaz and doʿa on Thursdays, approached us and offered to perform estekhareh ba tasbih for the woman I was speaking with. She explained that she had seen Lady Fatemeh (PBUH) [daughter of the Prophet Mohammad, also known as Hazrat-e Zahra] in a dream, who told her, “You can perform estekhareh, so do it” (تو میتوانی استخاره کنی و این کار را انجام بده). The woman agreed, and the older Afghan woman asked for her name and her mother’s name before asking her to make a wish or intention (niyat).21 After the wish was made, she held the tasbih in her hand and began reciting various zekrs (fig. 32). After a few seconds of reciting zekr, she randomly grasped a section of the tasbih and began counting and separating them in pairs. She did this twice. If the final bead of the section was single, the answer to the wish was considered negative, and if it was even, the answer was positive. The result for the woman’s wish was positive, and after the ritual was complete, she gave the Afghan woman ten thousand tomans as a token of gratitude.

8. Last Thursday of the Year and Visiting Graves

The tradition of grave visitation at the end of the year [March in the Iranian solar calendar] is an old custom among Iranians and usually takes place on the last Thursday of the year. People visit the cemetery, place colorful vases and bouquets on graves, recite the Fateheh (Fatiha), and offer kheyrat (charitable food) in memory of their deceased ones as they prepare to welcome Nowruz and the start of the New Year with their loved ones (figs. 33–36) (see the Checklist, no. 43). After the New Year begins, it is also customary for people to visit cemeteries, lay out a Haft-Sin spread (sofreh-ye haft-sin) at the graves of their loved ones, and offer New Year greetings to the deceased and each other. Some also engage in religious practices by conducting a Sofreh Salavat ceremony, performing namaz, and reciting doʿa. This year, with Nowruz coinciding with the month of Ramadan, the recitation of the Ziyarat Ashura prayer and the offering of nazri were held at sunset and iftar [breaking of the fast]. Residents of the neighborhood stayed for the Ziyarat Ashura prayer and, after performing namaz, broke their fast with the nazri offered by a local benefactor, including lentil soup or abgoosht, bread and cheese, dates, and herbs.

***

The Last Visit

After several months, I visited the Emamzadeh Yahya for the last time. By now, the emamzadeh had become a familiar research field, and after months of absence, I found myself missing it. Seeing it again was exciting. It was late spring [May 2024], and the distinct sounds of birds chirping in the trees echoed throughout the courtyard. I sat in the eyvan of the tomb and reflected on the past few months. What stood out vividly in my mind was the closeness and affection people have for the emamzadeh, not only as a religious place but as also as a reminder of the identity and cultural history of the Kohneh Gel neighborhood. The fact that such a place can warmly welcome all social groups in the neighborhood is unique, and one not solely due to its religious nature. Meeting the social needs of the neighborhood community is another distinctive characteristic of the emamzadeh and expands its function beyond just being a sacred place (مکان مقدس, makan-e moqaddas). Of course, the historical and religious significance of the building has also endowed it with a distinctive quality. I took up my pen to record my final observations of a calm day with just a few people present and left the emamzadeh with the hope of visiting again.

Citation: Maryam Rafeienezhad, “The Green Solitude of Kohneh Gel: An Ethnography of Religious and Social Life in the Emamzadeh Yahya,” translated by Shahrad Shahvand. Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.

Notes

Editor’s note (Overton): The provided literal translation has been edited to ensure clarity while retaining the author’s distinct voice and writing style. Some additional glosses, definitions, and links to resources in English have been added to foster understanding. Throughout this translation, Emamzadeh refers to an individual, whereas emamzadeh refers to a tomb. This essay weaves between the Islamic lunar and Iranian solar calendars. A useful resource for date conversions can be found here. The first part of this essay, describing the setting and neighborhood, is well complemented by the Site Tour. The music in that film, and several others, is inspired by the ney in the audio clip here (see aud. 1).

Author’s note: This research (“The Ethnography of the Connection between Emamzadeh Yahya and the Lives of the People of Kohneh Gel”) was initiated in October 2023 and continued until early August 2024 [main fieldwork between November–May]. During this period, more than fifteen trips were made to Varamin for field-based data collection and observation. Some of these visits took place at different hours, days, and ceremonial occasions to enable the researcher to understand, as comprehensively as possible, all anthropological and cultural dimensions of the rituals and social connections between the people and the Emamzadeh Yahya, which holds a role and significance beyond that of a typical shrine in their lives. The primary challenges of the research were the distance between the researcher’s residence and the shrine and the lack of some data archives at local organizations and institutions in Varamin.

Acknowledgments: This research, in addition to having a team of specialists from different parts of the world, received support and cooperation from individuals without whose efforts this project would have been impossible. I would like to begin by thanking my good friends and advisors Dr. Jabbar Rahmani and Sepideh Parsapajouh for their supervision of this research. My gratitude also goes to my dear friend and companion Fatemeh Gharib, who accompanied me on numerous trips and took beautiful photographs. The professional collaboration and management of Dr. Keelan Overton, from whom I learned immensely, provided constant encouragement and motivation through the challenging phases of this project, deserving of my heartfelt thanks. I am also grateful to my good friend Ms. Somayeh Maleki for her help compiling demographic data and also Mr. Naser Taheri for his work in preparing and editing the maps of Kohneh Gel. I extend my appreciation to the diligent team of editors, whose careful reviews greatly improved my article. The support and cooperation of Mr. Mohammad Amini, a local historian of Varamin, were invaluable in compiling historical and cultural data about Varamin. Massumeh Khanum, the khadem of the Emamzadeh Yahya, and her daughter Fatemeh always welcomed me and my colleagues with open arms and played a crucial part in data collection. Mr. Mohammad Purchi Kangarlu, a member of the board of trustees of the Emamzadeh Yahya, provided warm and friendly cooperation in understanding the local culture of Kohneh Gel and the rituals of the Emamzadeh Yahya. Mr. Saadatkhah, the son of one of the former employees and board members of the Emamzadeh Yahya, also assisted in understanding the culture and customs of this neighborhood. Finally, I extend my sincere gratitude to all the residents of Kohneh Gel and the Afghan groups who welcomed me warmly and responded to my questions.

- Analysis of statistical data from the 1395 Sh/2016 Population and Housing Census, Somayeh Maleki, Demography Specialist. ↩

- Interviews conducted with residents reveal that the lands with registered plots and ownership deeds cover a wider area than what the municipality has designated as the Kohneh Gel neighborhood. Historically, the neighborhood covered a larger area. ↩

- According to the 1395 Sh/2016 Population and Housing Census, the Afghan immigrant population in this neighborhood was 600. After 1396 Sh/2017, based on qualitative findings from interviews, this number has increased significantly, which calls for more detailed quantitative study. ↩

- The author merely recounts the people’s narratives and has not conducted any specific study on this topic herself. ↩

- In his Tashayyoʿ dar Varāmīn (Shiʿism in Varamin), Ahmad Ahmadi states that the people of Varamin accepted Islam in the first half of the first/seventh century. See Ahmadi and Shakeri, Tashayyoʿ dar Varāmīn, 257. The fact that Rey [Shahr-e Rey, to the north] was a pioneer in adopting Shiʿism and Shiʿi culture significantly influenced the migration of Shiʿis to Varamin. ↩

- For more information, see Amini, Tārīkh-e ejtemāʿī-ye Varāmīn (Social History of Varamin). ↩

- Jane Dieulafoy, along with her archaeologist husband, traveled to Iran in 1881. She documented her journey through photographs and writings, which were published as two separate books. She visited Iran two more times thereafter. For further reading, see Safarnāmeh-ye Madame Dieulafoy (La Perse, La Chaldée et la Susiane). ↩

- This information is based on the statements of Mr. Amini. ↩

- ‘bazdid-e ahl-e qobur’ (بازدید از اهل قبور) is a phrase commonly used by Iranians for visiting the deceased. The term ‘ahl-e qobur’ refers to the deceased, and these visits typically occur on weekends, either Thursday or Friday evenings, when people go to the cemetery to visit the graves of their loved ones. ↩

- Greeting the sacred Emamzadeh or invoking the Emamzadeh’s name is done with Arabic expressions such as: السلام علیک یا امامزاده یحیی. ↩

- In sacred places, holy objects always serve as mediums for connecting with God or the Emamzadehs, and the pilgrim often uses material tools to establish a connection. It is within this sacred relationship that the objects themselves acquire sanctity; for example, the cloths or tasbihs pilgrims use to fulfill their wishes or the foods and offerings made as nazr to be distributed as charity. ↩

- The story of the ʿalam dates back to the initial settlement of the Kangarlu tribes, some of whom were relocated from Armenia to Varamin (see Tarīkh-e ʿĀlam-ārā-ye ʿAbbāsī; The World Adorning History of ʿAbbasi). During the Qajar era, following conflicts among the tribes, Maqsud Soltan of the Kangarlu was appointed by Iran as the governor of the Nakhchivan fortress. These tribes were later exiled to Varamin during the reign of Fath ʿAli Shah. People believed that the ʿalam belonged to Hazrat-e Abu al-Fazl. For further study on the history of the Kangarlu tribes’ migration, see Amini, ʿAshāyer-e manṭaqe-ye Varāmīn (The Tribes of the Varamin Region). ↩

- For further study, see Amini, Tārīkh-e ejtemāʿī-ye Varāmīn (Social History of Varamin). ↩

- Amini, ʿAshāyer-e manṭaqe-ye Varāmīn (The Tribes of the Varamin Region). ↩

- Durkheim, one of the first and most important theorists of the social function of religion, believed that religion can reinforce the social structure of societies as an arm of political power. Under this power, individuals can therefore also elevate their social status in religious places. For further study, see Giddens, Jāmeʿeh shenāsī, (Sociology), 492. ↩

- The transfer of the deceased to sacred places is a tradition that has long been common among Shiʿis. This practice was so deeply rooted in some Shiʿi families and scholars that if it was not possible to transport the body immediately after death, it would be temporarily buried and later moved to the designated sacred location once obstacles were removed. This tradition was also prevalent in Iran. Some, for example, would request in their will to be buried in Mashhad (at the shrine of Emam Reza) or in Qom (at the shrine of Fatemeh Maʿsumeh). To ensure this, they would leave funds for their heirs to cover the costs of transporting their bodies, after desiccation, through a complex process to the holy sites. For further study, see Faqih Bahrololum, Tārīkhcheh-ye Enteqāl-e Janāʾez. ↩

- In the past, ziyarat to sacred and holy sites, such as the shrines of the Emams, was a difficult and lengthy journey, sometimes taking several months. In people’s beliefs, visiting these sites was extremely valuable and significant. A person who went on a pilgrimage to Emam Reza’s shrine in Mashhad would be called ‘Mashhadi,’ often shortened colloquially to ‘Mashti’ or just ‘Mash.’ ↩

- A maddah recites religious poetry at religious ceremonies, whether joyful or somber, to encourage the audience to celebrate or weep. In the past, such individuals were known as ‘rozeh-khans,’ but today they are referred to as ‘maddah.’ ↩

- Despite its overall decline, the practice of applying henna to the hands, feet, and facial hair remains a common custom among villagers and nomads. It is considered a sort of religious tradition performed during celebrations and ceremonies, especially during Eid-e Fetr (Eid al-Fitr), Eid-e Qorban (Eid al-Adha), and Eid-e Ghadir (Eid al-Ghadir), and it is done during Nowruz with the intention of bringing joy and happiness. The application of henna during joyous occasions is also mentioned in the poetry of some poets. ↩

- According to Shiʿi Muslim beliefs, the birthday of Emam Mahdi, the Twelfth Emam, is an auspicious day, and in Shiʿi tradition, this day is celebrated with festivities. ↩

- With this statement, she wanted to emphasize the ability and sanctity that Lady Fatemeh had bestowed upon her and to inform the women about it. ↩

Bibliography

- احمدی، احمد و طاهره شاکری. تشیع در ورامینتهران: انتشارات نظری، ۱۳۹۶ش. [Ahmad Ahmadi and Tahere Shakeri, Tashayyoʿ dar Varāmīn, Shiʿism in Varamin, 2017] [Lib.ir]

- امینی، محمد. تاریخ اجتماعی ورامین در دوره قاجاریه. تهران: چاپ شرکت افست، ۱۳۶۸ش. [Mohammad Amini, Tārīkh-e ejtemāʿī-ye Varāmīn, A Social History of Varamin during the Qajar Period, 1989] [Lib.ir]

- امینی، محمد. عشایر منطقه ورامین در گذشته و حال: انتشارات واج، ۱۳۸۴ش. [Mohammad Amini, ʿAshāyer-e manṭaqe-ye Varāmīn, The Tribes of the Varamin Region, 2005] [Lib.ir]

- دیولافوا، ژان. سفرنامه مادام دیولافوا، ترجمهی علیمحمد فرهوشی. تهران: انتشارات دنیای کتاب، ۱۳۹۸ش. [Jane Dieulafoy, Safarnāmeh-ye Madame Dieulafoy, La Perse, La Chaldée et la Susiane, translated by Alimohammad Farahvashi, 2019] [Lib.ir]

- گیدنز، آنتونی. جامعهشناسی. ترجمهی منوچهر صبوری، تهران: نشر نی، ۱۳۹۹ش. [Anthony Giddens, Jāmeʿeh shenāsī, Sociology, translated by Manouchehr Saboori, 2020]

- قرهچانلو، حسین. «امامزاده یحیی (ورامین).» در: وقف میراث جاویدان ۱، شمارهی ۲ (۱۳۵۳ش.): ۷۰-۷۳. [Hossein Qarachanlu, “Emāmzādeh Yahya (Varāmīn),” 1974] [Noormags.ir]

- فقیه بحرالعلوم، محمد مهدی. «تاریخچه انتقال جنائز به عتبات عالیات (شهر کربلا).» در: فصلنامهی فرهنگ زیارت ۸، شمارهی ۳۳ (۱۳۹۶ش.): ۷-۴۴. [Mohammad Mehdi Faqih Bahrololum, “Tārīkhcheh-ye Enteqāl-e Janāʾez,” History of the Transfer of Corpses to the Holy Shrines, 2017] [Noormags.ir]

- منشی، اسکندر بیگ. تاریخ عالم آرای عباسی. تهران: امیرکبیر، ۱۳۵۰ش. [Eskandar Beg Monshi, Tarīkh-e ʿĀlam-ārā-ye ʿAbbāsī, The World Adorning History of ʿAbbasi, 1971] [Lib.ir]