The History of Varamin and its Shiʿi Significance, 10th–20th Centuries

ترجمه فارسی

The goal of this essay is to offer a chronological history of Varamin over ten centuries and summarize its shifting political, economic, demographic, and cultural circumstances. Following the style of an encyclopedia entry (for example, Minorsky, “Warāmīn; ”Bosworth, “Warāmīn;” and Blair and Bloom, “Varamin”), this essay provides a detailed narrative of Varamin’s evolution from a prominent stop on ancient trade routes to a significant Shiʿi center and Ilkhanid provincial capital to a modern suburb of Tehran. Special emphasis is placed on Varamin’s Shiʿi significance through its notable families, intellectuals, and architectural heritage.

Geography and Economic Significance

The history of Varamin is closely intertwined with two nearby cities: Rey (Ray, Rayy) and Tehran. Rey was a prominent city and the capital of several dynasties from the third century BCE until the early thirteenth century. Located twenty-five miles northwest of Varamin, its few remnants can be found within a residential area called Shahr-e Rey (lit. City of Rey) (map). This area gradually merged into the expanding urban landscape of greater Tehran, which has been Iran’s capital since 1786. Varamin is located approximately thirty-five miles southeast of Tehran and remains its own distinct city and the capital of Varamin county (shahrestan) (fig. 1).

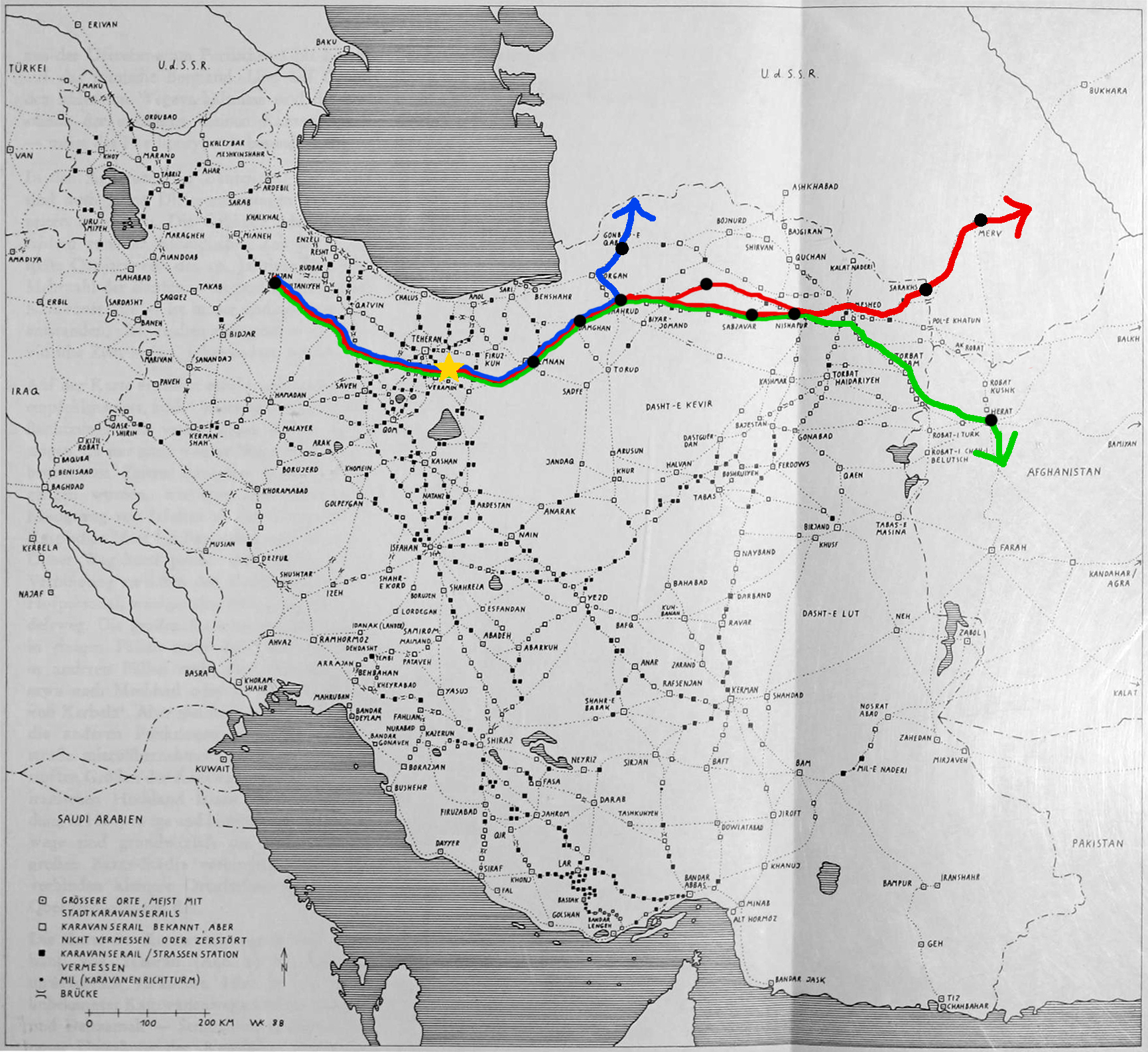

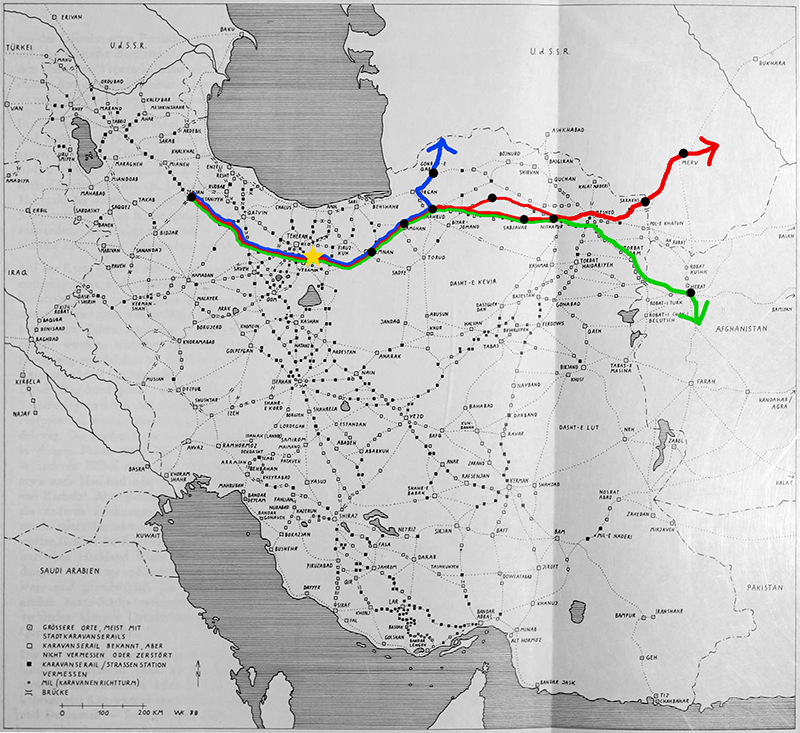

Throughout its history, Varamin has been an important stop on major roads and trade routes crisscrossing the Iranian plateau. During the Sasanian empire (224–651), Qalʿeh Iraj (map), an expansive rectangular citadel two miles northeast of modern Varamin, was one of the stops along the famous Silk Road toward Rey.1 After the Muslim conquest in the seventh century, and particularly during the Buyid dynasty (ca. 945–1055), Varamin became a frequent stop connecting Rey to important cities like Esfahan.2

Varamin’s significance peaked during the late Ilkhanid period (1256–1335), when it became a key stop on the route from Soltaniyeh, the Ilkhanid capital in the northwest, to eastern cities like Balkh, Sistan, and Kharazm (Khwarazm) (fig. 2).3 Its prominence continued through the Timurid period (ca. 1370–1507), and famous European travelers like Ruy González de Clavijo (d. 1412) passed through it en route to Samarqand and China.4 With the increased focus on Tehran during the Safavid period (1501–1722), Varamin started to lose its significance. During the Qajar dynasty (1779–1925), Tehran became the capital of Iran, and the road connecting the capital to the east no longer passed through Varamin. Known today as the Emam Reza Highway (Road 44), this road is one of the most important highways in Iran and part of the Asian Highway 1 project connecting Asia to Europe. Although Varamin’s role as a major stop on key trade routes has decreased over the past three centuries, it has remained an important agricultural hub, as discussed below.

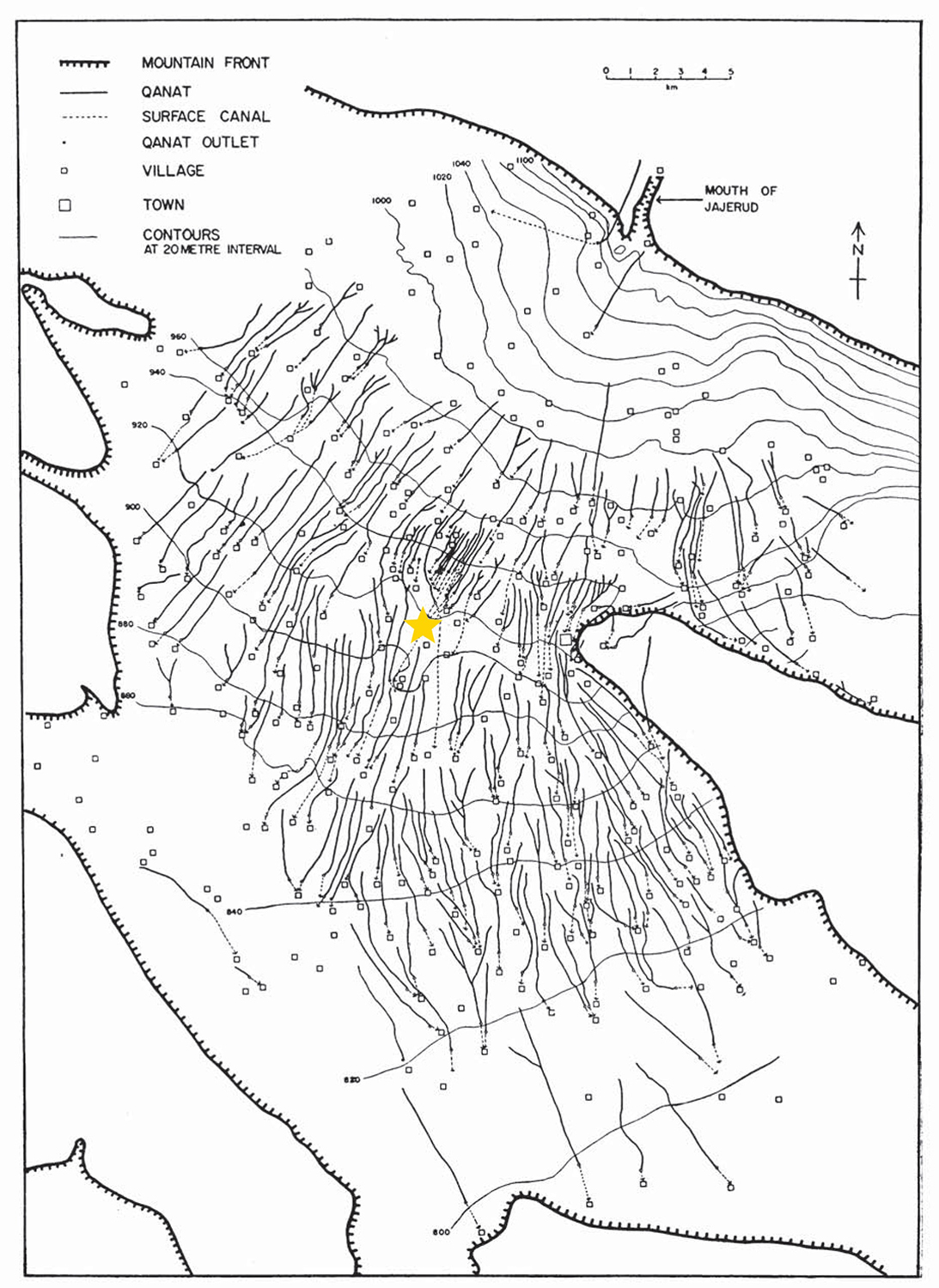

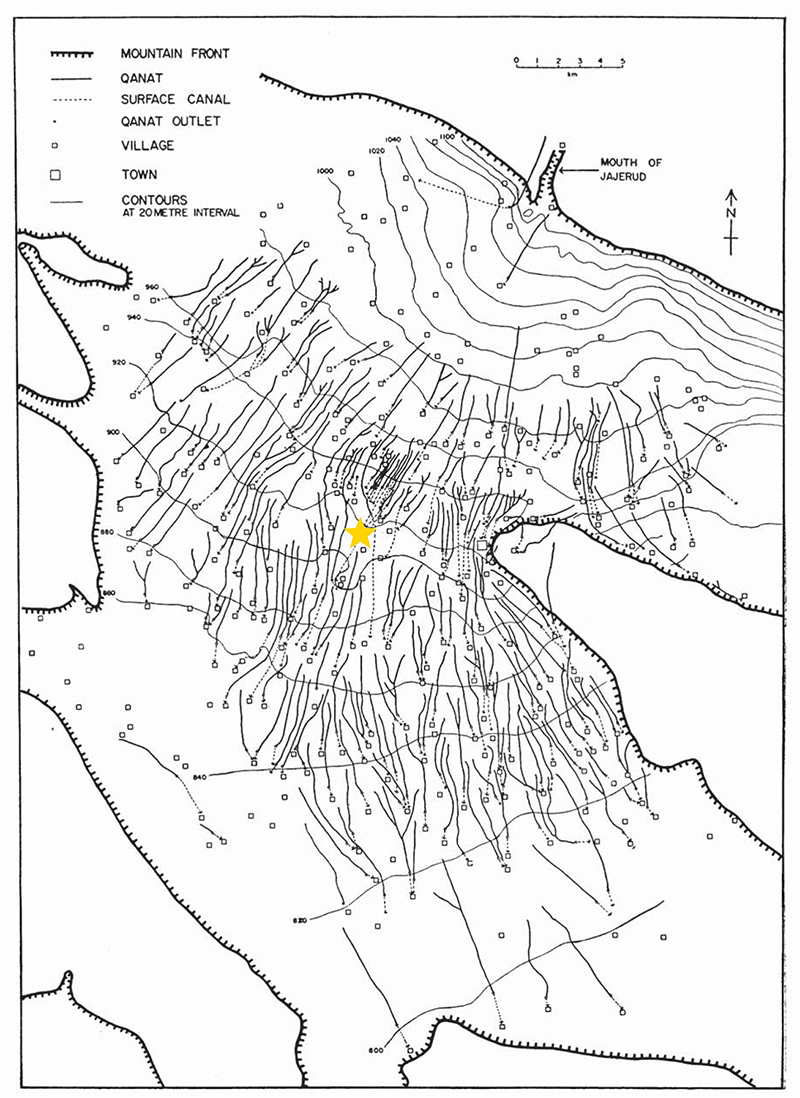

Varamin is located in the plain between the Alborz Mountains to the north and the Great Salt Desert (Dasht-e Kavir) to the southeast, which gives it the advantage of multiple water resources and rich semi-desert soils. Before modern irrigation systems were introduced, Varamini farmers used hundreds of underground canals known as qanat, along with surface water from the mouth of the Jajrud River, about ten miles to the north (fig. 3).5 Textual sources from the tenth to seventeenth centuries indicate that cotton, wheat, and grapes were cultivated in Varamin.6 Throughout the Qajar era, Varamin was renowned for its agricultural products, particularly vegetables, which found a significant market in Tehran.7 This legacy persists today, with Varamin’s fertile lands continuing to supply the capital.

The Rise of Varamin as a Shiʿi Center (1100s–1220s)

The name of Varamin first appeared in tenth-century geographical texts as a large and populated qaryeh (village) in the Rey region.8 Subsequently, eleventh-century genealogy books highlighted Varamin as the residence and burial place of notable descendants of Shiʿi Emams, including Yahya b. ʿAli (d. ca. 860s), for whom the Emamzadeh Yahya was built.9 By the twelfth century, Varamin flourished to such an extent that it was considered comparable to a city and included in the list of major Shiʿi cities alongside Qom, Kashan, and Aveh.10

Varamin’s prosperity in the late Seljuk period (1140s–1194) was deeply intertwined with a single Shiʿi family led by Razioddin (Razi al-Din) Abu-Saʿd Varamini (fl. 1160s), an affluent local ruler (raʾis).11 Razioddin Abu-Saʿd and his son Montajaboddin (Montajab al-Din) Hosayn were praised for their substantial contributions to restoring Muslim holy sites in Mecca and Medina as well as various Shiʿi shrines (mashahed-e aʾemmeh).12 The social status of this family peaked when Razioddin’s grandson—Fakhroddin (Fakhr al-Din) b. Safioddin (Safi al-Din) Ahmad b. Razioddin Abu-Saʿd—was appointed vizier under Tughrul b. Arslan (r. 1176–91, 1192–94). His tenure under the Seljuks lasted only a few months, however, as the empire fell in 590/1194.13 In Varamin, this family participated in architectural and educational endeavors, including constructing a masjed-e jameʿ (congregational mosque) and two religious schools with sufficient endowments to support scholars and students.14

The rise of Varamin as a prominent Shiʿi center was further influenced by circumstances in neighboring Rey, which had been home to a large Shiʿi population since the ninth century and had historically provided Varamin with economic, political, and cultural support. In 617/1220, the dynamic between the two cities changed dramatically. As recorded by geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi (d. 1229), during conflicts between Rey’s Shiʿi majority and Sunni minority, the latter took control of the city and left most of it in ruins.15 Since Varamin was located just twenty-five miles south of Rey and under the absolute control of affluent Shiʿi families, it naturally emerged as the region’s next major Shiʿi city.

Ilkhanid Provincial Capital (1270s–1330s)

The Mongol invasions of Iran were also a catalyst in Rey’s demise and Varamin’s rise. Following the Mongols’ multiple attacks on Rey between 616/1219 and 656/1258, Varamin gradually became the region’s economic, political, and ideological center. This transition was accomplished under the leadership of the Alavi Hosayni Varamini family (‘Alavi’ in reference to Emam ʿAli, d. 661), whose ancestral lineage can be traced to Ahmad b. Ibrahim b. Ismaʿil Monqazi, who came to Varamin in the ninth or tenth century and was a seventh-generation descendant of Emam Hosayn (d. 680).16 The family’s descent from Shiʿi Emams granted them substantial respect and influence within the predominantly Shiʿi community of the Rey region, enabling them to occupy pivotal roles in both political and religious positions.

During the Ilkhanid period, Varamin was promoted from a qaryeh to a shahr (city) and made the dar al-molk (capital) of Rey province.17 Three members of the Hosayni Varamini family served as governors (malek): Fakhroddin (Fakhr al-Din) Hasan b. Jamaloddin (Jamal al-Din) Mohammad, his son ʿAlaoddin (ʿAlaʾ al-Din) Morteza b. Fakhroddin Hasan (d. 675/1276), and his grandson Fakhroddin Hasan b. ʿAlaoddin Morteza (d. 707/1308).18 The last appears in Rashidoddin’s (Rashid al-Din, d. 1318) famous Jameʿ al-Tavarikh (Compendium of Chronicles) on several occasions, indicating that he was a court favorite during the reigns of Arghun (r. 1284–91) and Uljaytu (r. 1304–16).19 In 682/1284, before he became emperor, Arghun operated a business in Varamin consisting of three hundred households of artisans (khaneh-ye ouz), probably under the supervision of Malek Fakhroddin Hasan.20 The city was particularly famous for its cotton plantations and weavers, and it is likely that those artisans produced textiles.21 The economic investment of the crown prince in Varamin underscores the importance of the city and its Shiʿi rulers in the Ilkhanid economy.

Thanks to connections with the Ilkhanid court, Varamin enjoyed relative stability during the early fourteenth century, and coins were minted in the city for the first time in its history. The American Numismatic Society in New York preserves two of these coins dated 711/1311–12 (fig. 4).22 The reverse of these coins is inscribed with the Salavat-e Kabireh, a specific form of Islamic prayer (salavat) that involves sending blessings to the Prophet Mohammad, Emam ʿAli, and the other eleven Shiʿi Emams. This inscription not only reflects the prevalent faith in Varamin but also signals Uljaytu’s conversion to Shiʿism in 709/1309 under the influence of prominent scholars. Among those who presented Shiʿi ideology to the Ilkhan was one Jamaloddin Varamini, likely Jamaloddin Mohammad b. Naser Alavi Hosayni ʿEraqi Varamini of the distinguished Hosayni Varamini family.23

The Shiʿi fervor and ideology of fourteenth-century Varamin is also reflected in the city’s literary production. In one of his poems, the local poet Hamzeh Kuchak Varamini asserts that he chose to live in Varamin to counter the adversaries of Emam ʿAli:

زاد و مقام من به ورامین از آن بود

تا سور دشمنان علی چون عزا کنم

Zād-o maqām-e man beh Varāmīn az ān bovad

tā sūr-e doshmanān-e ʿAli chūn ʿazā konam

I was born in Varamin, and I live there,

To turn the feast of [Emam] ʿAli’s enemies into their funeral.24

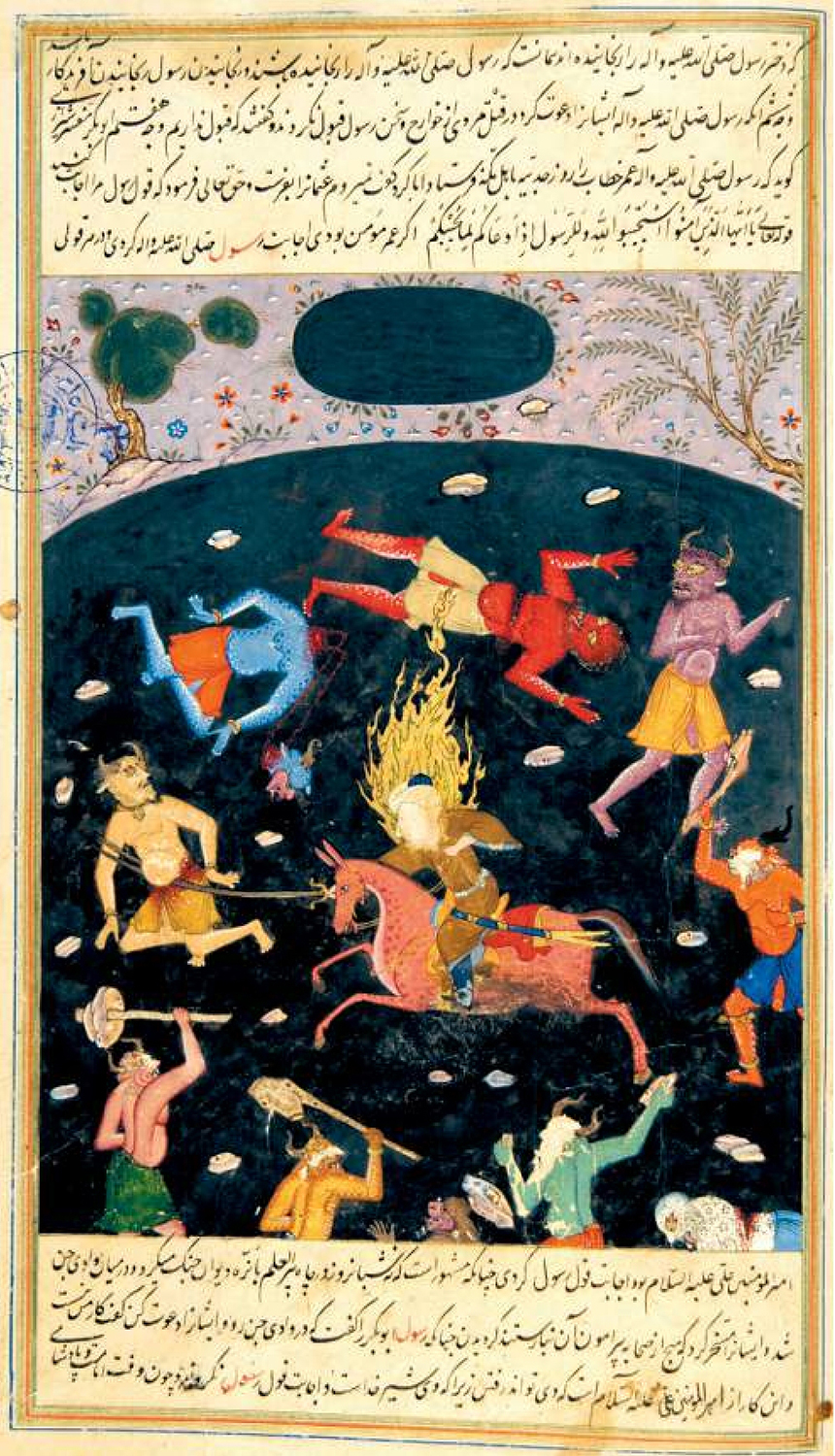

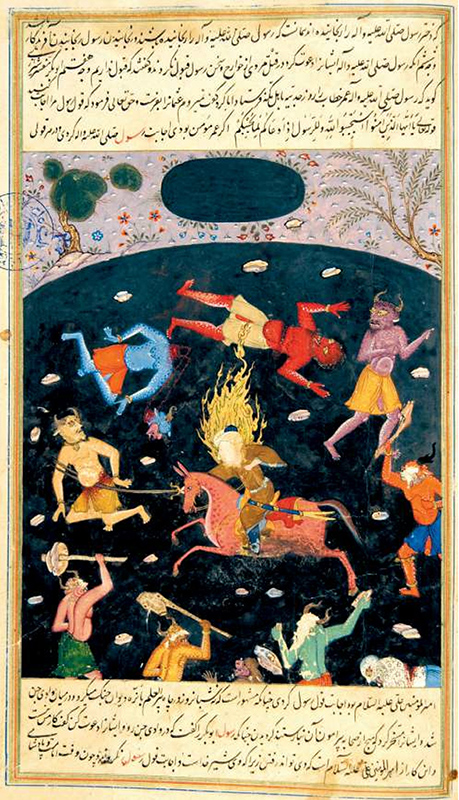

A similar ideology is also present in the Ahsan al-kibar fi maʿrefat al-aʾemat al-ʾathar (The Best of the Greats: On the Knowledge of the Immaculate Emams), written between 1338 and 1343 by another member of the Alavi Hosayni Varamini family: Mohammad b. Abi Zayd b. Arabshah Hosayni Varamini.25 In this text, the status of the Emams, and particularly Emam ʿAli, is exaggerated to a near-divine level in order to justify their legitimacy as the rightful successors of Prophet Mohammad. This manuscript received significant attention during the Shiʿi Safavid government, leading to the production of multiple illustrated versions (fig. 5).26 We will return to this book later.

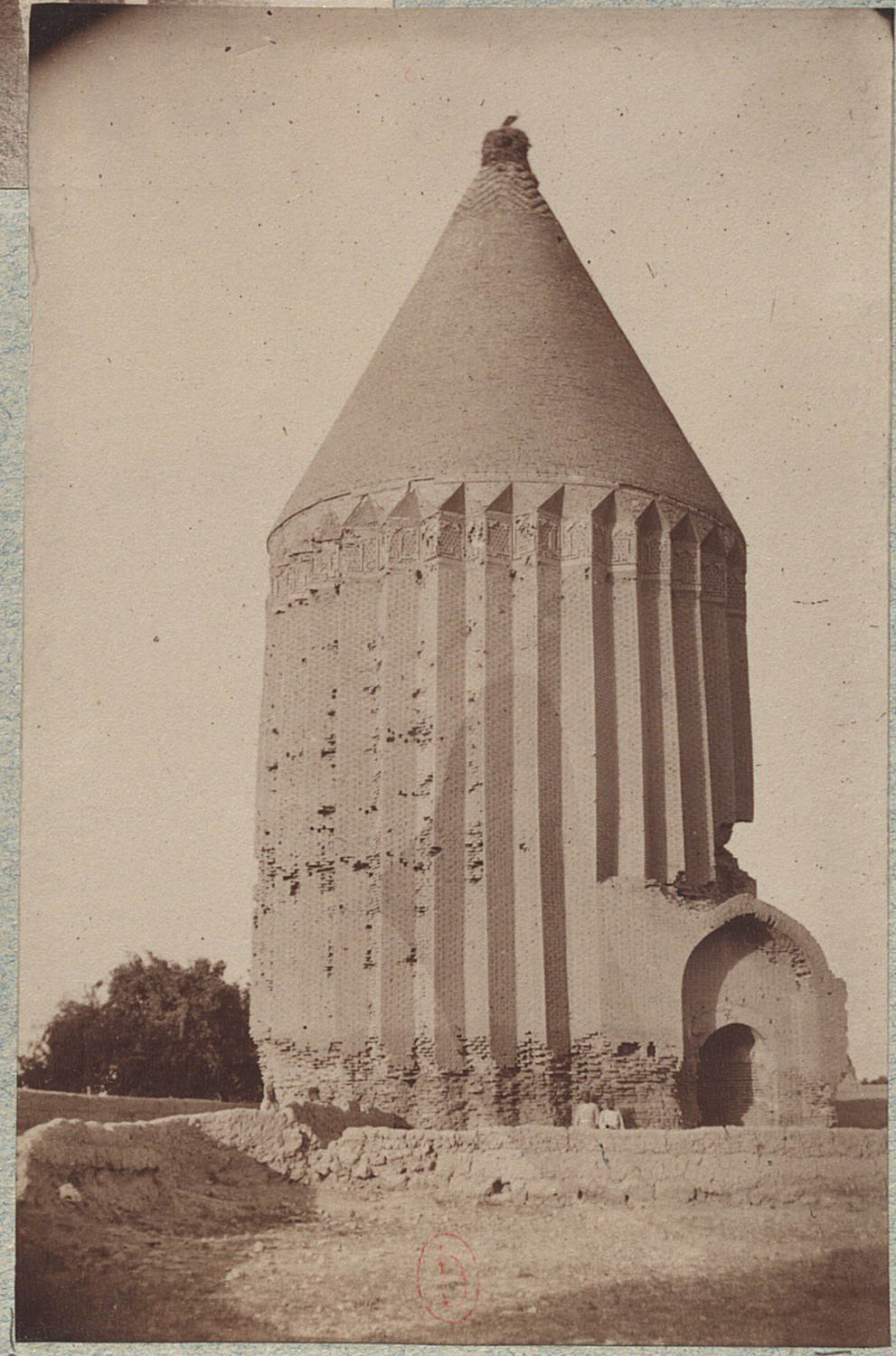

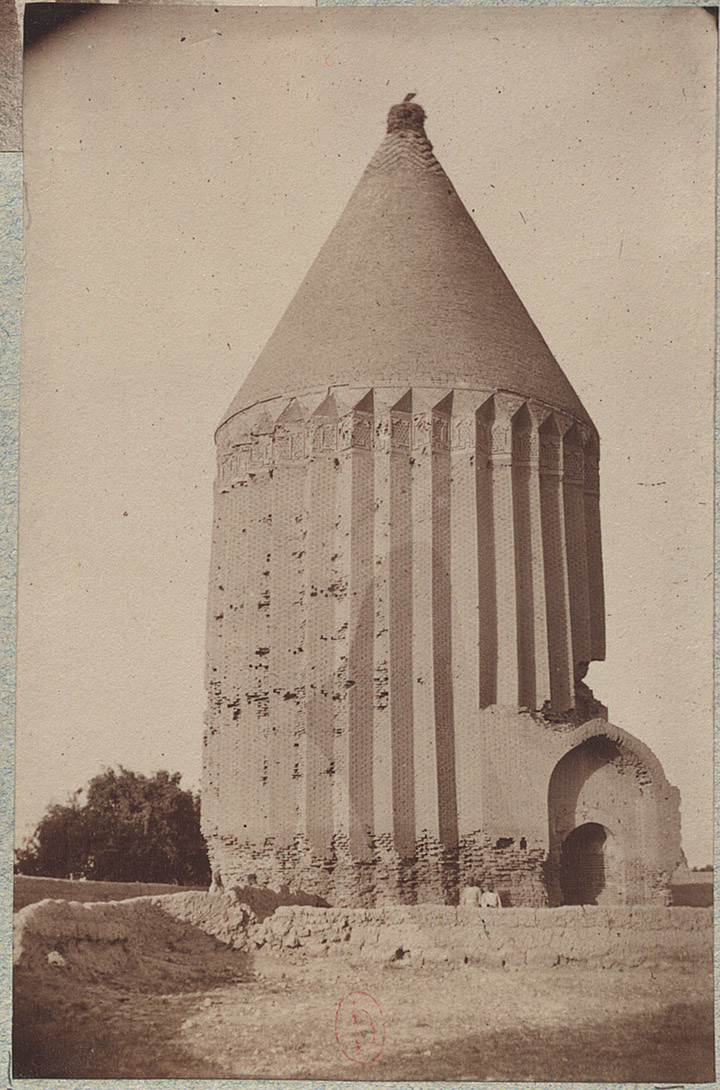

The Hosayni Varaminis were also major patrons of architecture, and many medieval monuments can be linked to them. Most relevant to this exhibition is their patronage of the Emamzadeh Yahya over five decades (c. 1260–1307), an effort likely started by Malek ʿAlaoddin Morteza and completed by his son Malek Fakhroddin Hasan, whose name is memorialized in the 707/1307 stucco band (see Stucco Inscription). Malek Fakhroddin Hasan was presumably also the patron of the city’s giant tomb tower commemorating his father, hence known as the ʿAlaoddin tower (borj-e ʿAlaoddin) (map) (fig. 6).27 The soaring height (27 meters) of the building reflects ʿAlaoddin Morteza’s political status as a high-ranking governor (malek), while its Kufic inscription introducing him as the asylum of the pure line (kahf al-ʿetrat al-tahirah) highlights his religious status as a descendant of the Prophet Mohammad.28

Today, Malek ʿAlaoddin’s tomb tower is primarily known as a memorial of a local ruler and even functions as a small local museum. By contrast, the burial places of many other members of the Hosayni Varamini family are revered as living emamzadehs, given their descent from Shiʿi Emams.29 Notable examples include the Emamzadeh ʿAli (map), Emamzadeh ʿAbdollah (map), Emamzadeh Zeyd Abolhasan (map), Emamzadeh Hadi al-Qazi (map), and Emamzadeh ʿAli Kiyakey (map). The Emamzadeh ʿAli is located directly east of the Emamzadeh Yahya, just a 17-minute walk, and its domed interior was covered with mirrorwork in recent decades (fig. 7). The saint’s cenotaph is enclosed in a rectangular metal zarih (pierced screen) covered in a green fabric, a symbolic color in Shiʿi sacred spaces.

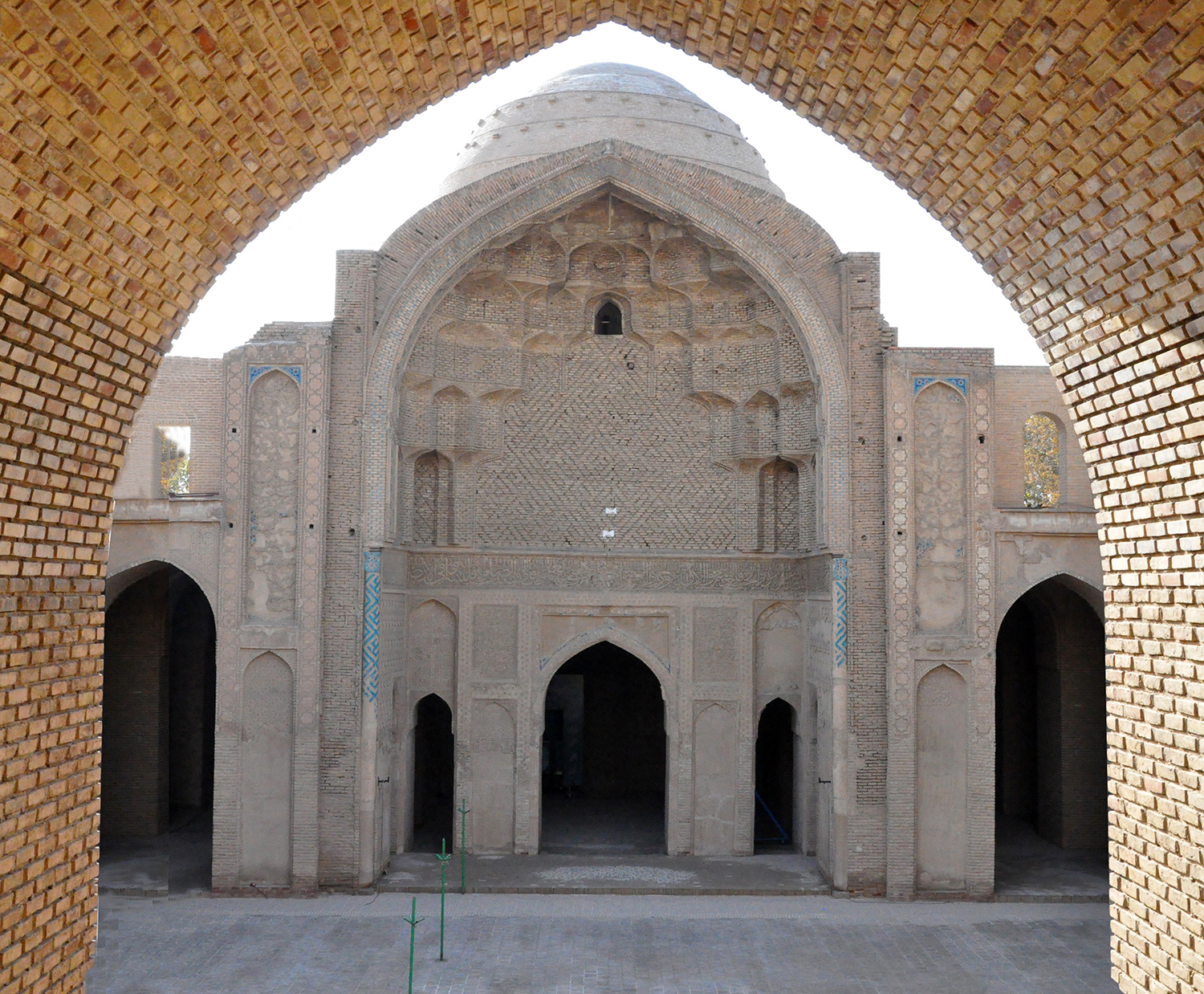

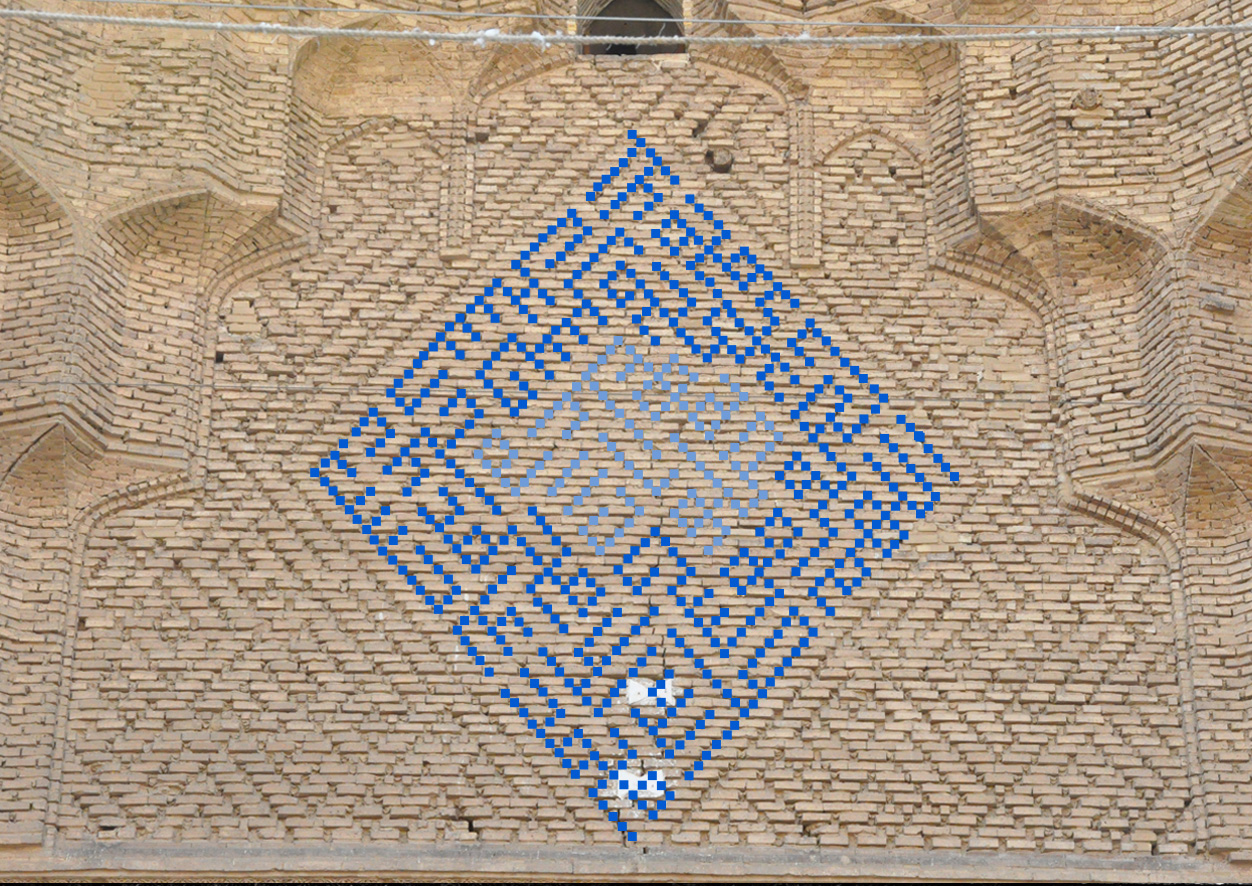

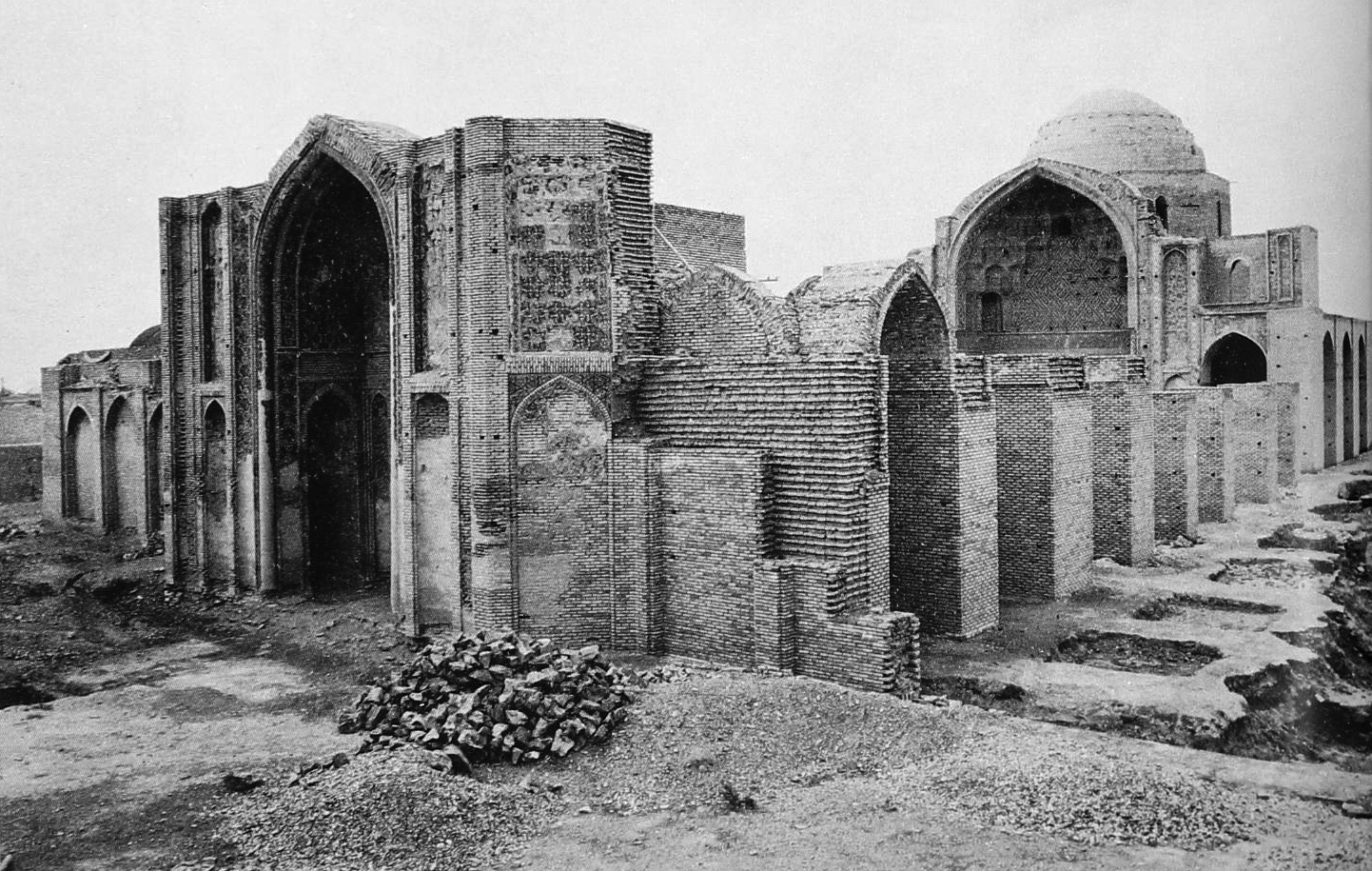

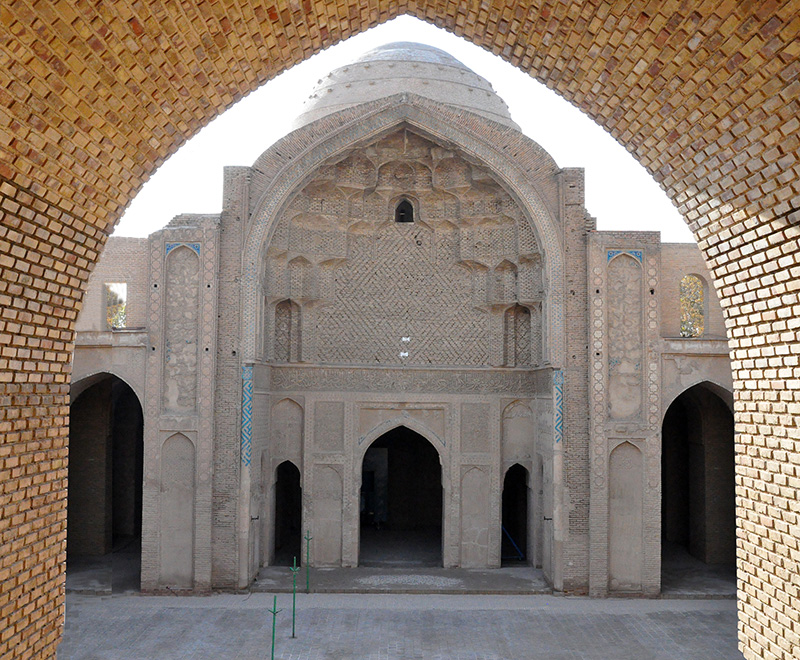

In addition to buildings directly tied to the Hosayni Varamini family, Varamin is home to many other monuments constructed during or just after their influential period of governorship. Among the most architecturally significant structures are the Emamzadeh Shah Hossein (map), Emamzadeh Sakineh Banu (map), tomb of Yusof b. Hosayn Razi (map), and the new congregational mosque (map), which likely replaced the twelfth-century mosque built by the Razioddin Varamini family (see Architectural Heritage). The construction of the new mosque was started in 722/1322 by the order of Khajeh ʿIzzoddin (Khwaja ʿIzz al-Din) Mohammad b. Mohammad b. Mansur Quhadi (d. c. 725/1325), a prominent figure in Malek Fakhroddin Hasan’s local court and a high-ranking official under Uljaytu and Abu Saʿid (r. 1316–35).30 This mosque is one of the most significant architectural projects in Varamin’s history, and like many other monuments in the city, it exhibits a strong Shiʿi bent through inscriptions referring to Emam ʿAli and his descendants. One example is the Salavat-e Kabireh inscription on the ayvan (Ar. iwan) leading into the domed qibla sanctuary, which is similar to the inscription on Varamin’s coins mentioned earlier (figs. 8–9).31

Instability and Transition (1330s–1700s)

Varamin’s flourishing period ended with the death of Sultan Abu Saʿid in 736/1335. According to the aforementioned Ahsan al-kibar, this trying and chaotic time was characterized by conflicts among governors, the decline of old families, and insecurity along main roads.32 This instability was exacerbated by Timur’s (r. 1370–1405) invasion of the region in the 1380s, and the once prosperous city of Varamin was left abandoned for around seventy years (c. 1330–1400). During his journey to Timur’s court in Samarqand in 1405, the Spanish traveler Ruy González de Clavijo described Varamin as a large but depopulated city without fortifications.33 Nonetheless, his very act of passing through the city on his way to and from Samarqand reveals that it remained a key stop on eastern trade routes.

Varamin’s strategic location along important roads played a key role in its partial resurgence during the fifteenth century. During the reign of Timur’s son Shah Rokh (r. 1405–47), Varamin received support from Timurid leadership and experienced a significant demographic shift. As part of his broader plan to restore and control conquered lands, Shah Rokh appointed two brothers of the Chaghatai elite, Amir Elyas Khajeh (d. 838/1434–35) and Amir Yusof Khajeh (d. 846/1442), as governors of Qom, Kashan, Rey, and Rostamdar in Gilan province.34 The arrival of new rulers and troops meant that inhabitants of the province were gradually replaced with members of different tribes (ʿashayer), including Arabs, Turkmen, Baluch, and Khalaj.35 During their period of governorship from 1415 until 1442, the Chaghatai amirs contributed to Varamin’s architectural heritage, including completing and renovating the congregational mosque in 845/1441 (recall the vertical panels in fig. 8) and some degree of intervention in the Emamzadeh Hosayn Reza (Hosayn Razi) (map) in 841/1437 (fig. 10).36 The dated Qur’anic inscription inside the tomb does not reveal if it marks construction or a later decorative intervention.37

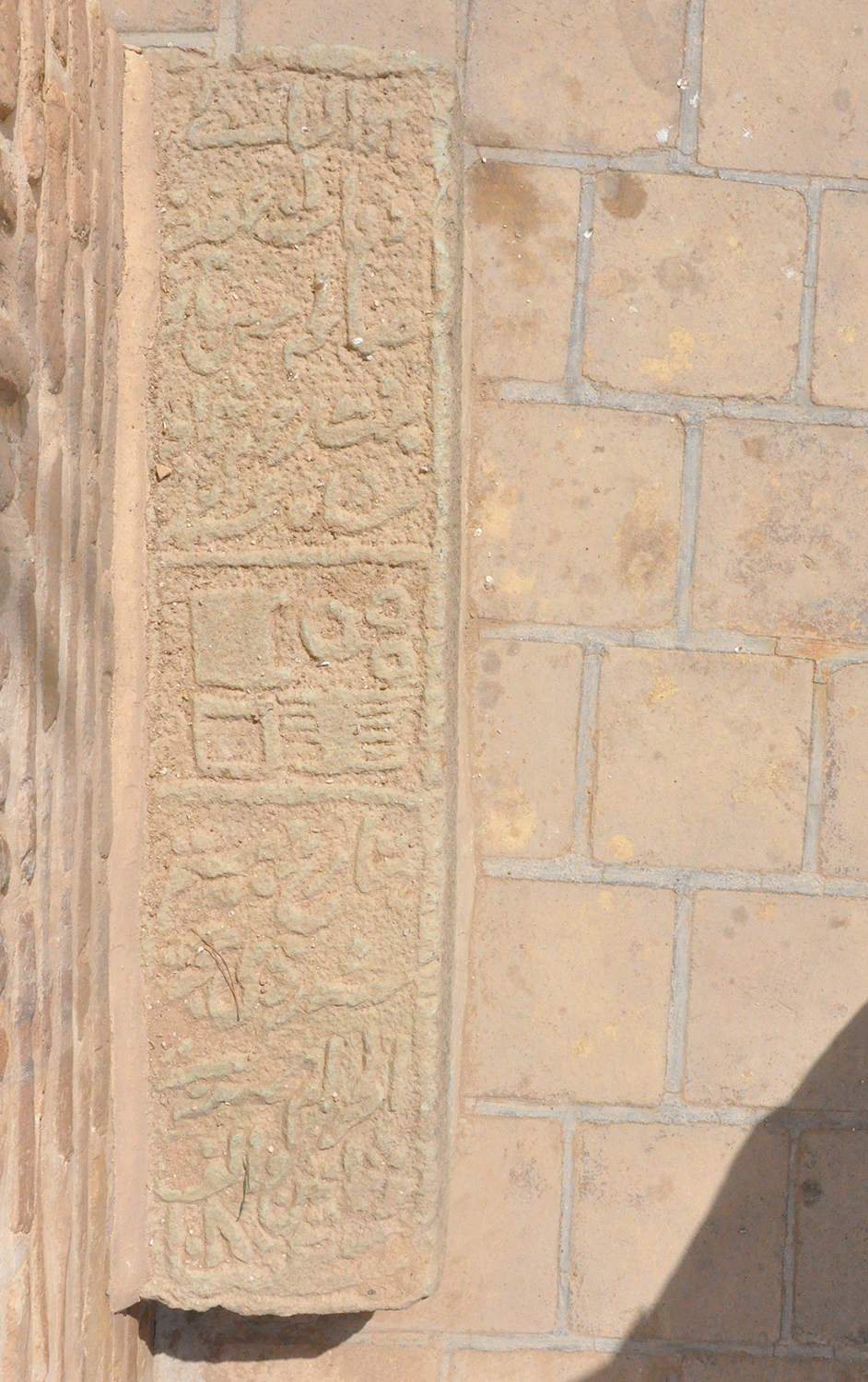

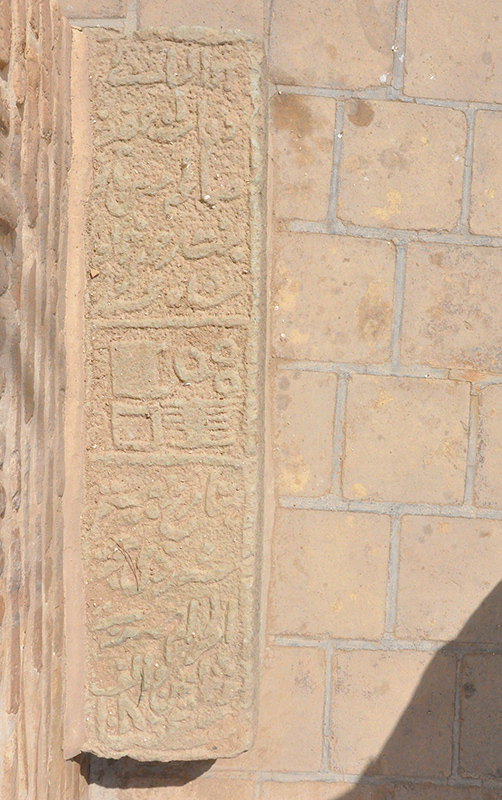

Although there are several tombs attributed to Sufis (ʿaref) in Varamin, including the tomb of Yusof b. Hosayn Razi (map) and the Emamzadeh Hosayn Reza (map), the city’s oldest confirmed Sufi shrine is the Emamzadeh Seyyed Fathollah (Fath-Allah) (map) dated Rajab 889/August 1484.38 Based on the foundation inscription (see this image), the tomb is the burial place of Seyyed Fathollah al-Hosayni, revered as soltan al-ʿarefin (the king of Sufis). This tomb was part of a larger complex including a mosque and was patronized by Nasrollah (Nasr-Allah) b. ʿAtaʾollah (ʿAtaʾ-Allah) al-Hosayni.39

The Safavid period (1501–1722) marked a significant shift in administrative authority from Varamin to Tehran. Although Varamin was initially the co-capital of Rey province with Tehran, Shah Tahmasp I’s (r. 1524–76) reign saw a decline in its stature, and the shah concentrated on developing Tehran with a defense wall and bazaar.40 His most significant architectural patronage in the Varamin area was the construction of a new tomb for the Emamzadeh Jaʿfar (map) at Pishva (fig. 11).41 This patronage likely stemmed from the belief that Emamzadeh Jaʿfar was the son of Emam Musa (d. 128/799), the seventh Shiʿi emam, a lineage that the Safavid kings also claimed.42 The only example of Safavid patronage that is known in Varamin proper is a wood door dated Safar 971/September 1563 and endowed to the Emamzadeh Yahya.43 The question of why the Shiʿi Safavid kings generally appear to have overlooked Varamin—a city with a deep history of Shiʿism—remains unresolved.

Even though Varamin became politically marginalized during the Safavid period, its literary productions were known to the court. In 955/1548, following the order of Shah Tahmasp I, ʿAli b. Hasan Zavareʾi summarized the Ahsan al-kibar in a new work titled Lavameʿ al-anvar fi maʿrefat al-aʾemat al-ʾathar (The Gleams of Lights in Understanding the Immaculate Emams).44 Multiple copies of the original text were also produced, including illustrated manuscripts now in the Golestan Palace Library and Archive (see fig. 5) and National Library of Russia.

A final point about Varamin’s Safavid period concerns its shifting demographics. The Safavid dynasty was founded in 1501 with the aid of the Qizilbash, a coalition of seven Turkmen Shiʿi tribes historically based in Anatolia, Syria, and the Caucasus. During the sixteenth century, two of these tribes—the Ostajlu and Takkalu—gained influence in the Varamin region, and local rulers were often elected from their ranks.45 One example is Erdoghdi Khalifa (d. 1582), who was a Sufi and one of the powerful leaders of the Takkalu tribe.46 The memory of these newcomers has been maintained through the tribal iconography depicted on their tombstones. For instance, a tombstone of a woman dated 1086/1676 and once in the courtyard of the Emamzadeh Yahya features carvings of everyday items such as scissors (fig. 12). Such iconography is not unique to the Takkalu tribe but is found on tombstones of various tribes across Iran and used to signify the gender of the buried person.

A Mere Village (1800s)

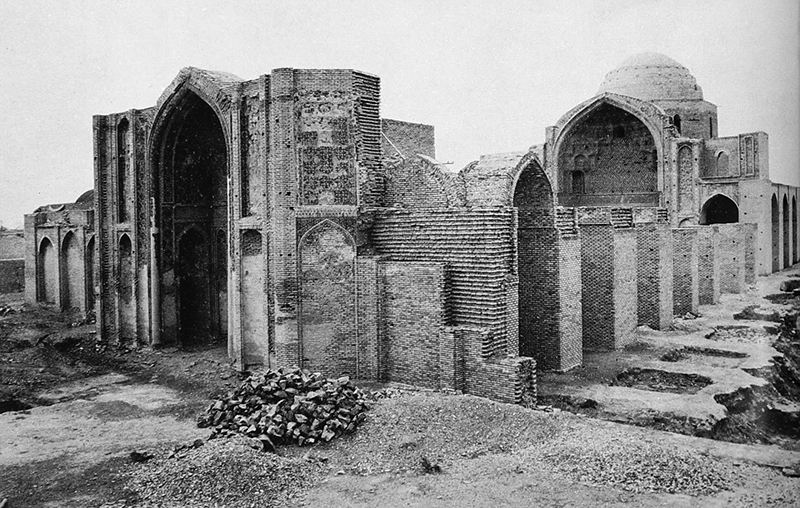

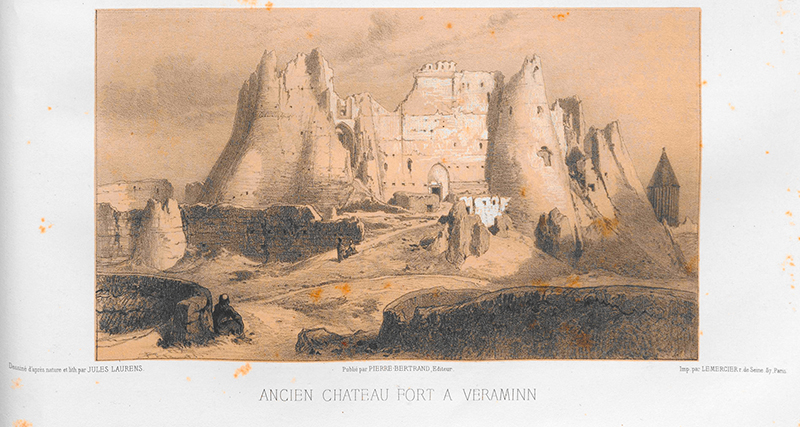

The medieval city of Varamin, once located on the south side of the congregational mosque, was largely in ruins by the nineteenth century. Only remnants of tombs and houses remained, and many travelers commented on the city’s ruinous state.47 This condition was attributed to natural disasters, including floods.48 The signs of this flood were visible on the walls of the ʿAlaoddin tower and congregational mosque before their renovation and likely explains the almost complete loss of the west side of the mosque’s courtyard (figs. 13–14). As a result, settlement shifted northward toward the tomb of ʿAlaoddin, and Varamin was reduced to a mere village (qaryeh). Despite these changes, it remained home to a diverse number of tribes, including the Kangarlu and Bakhtiari.49

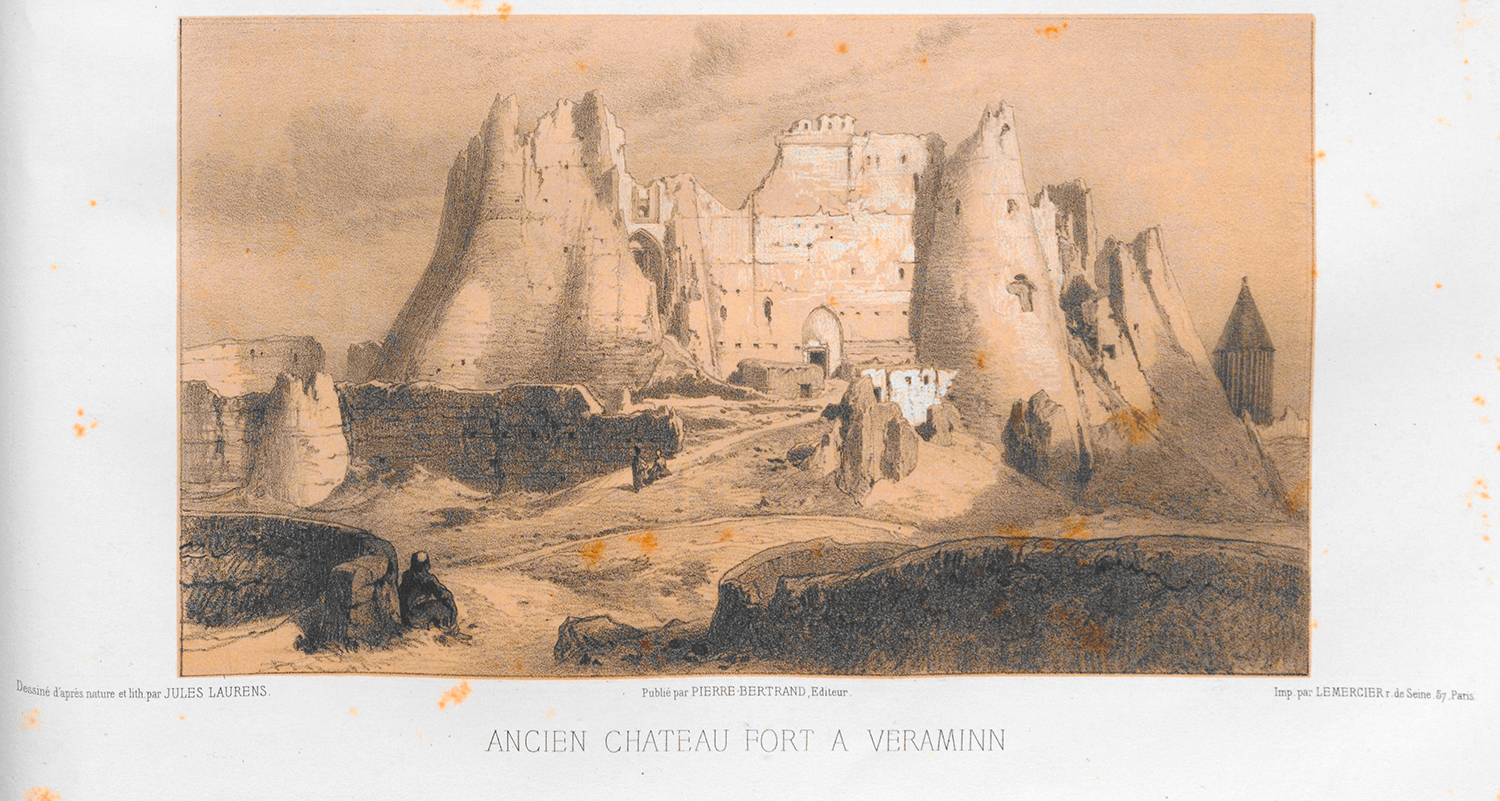

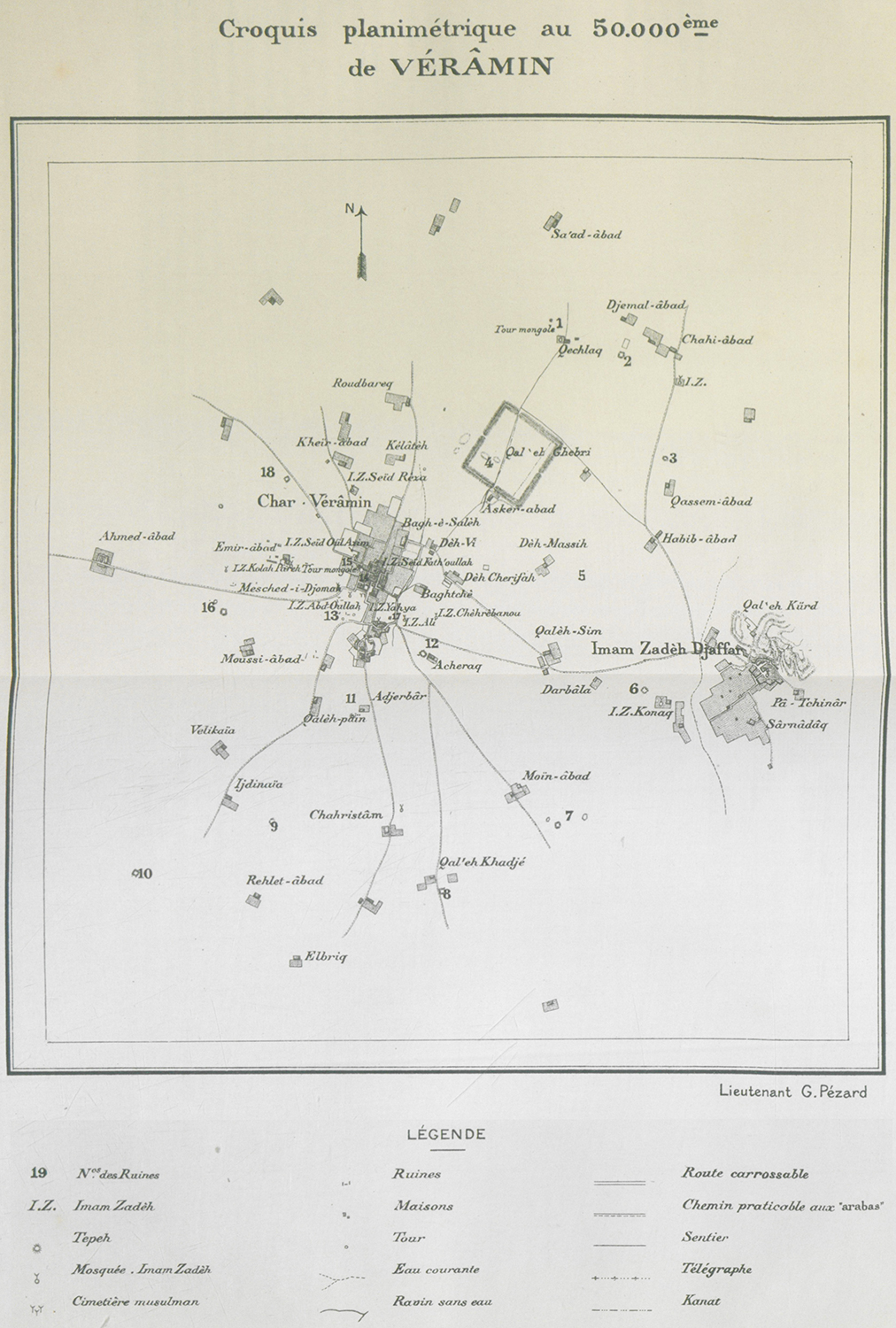

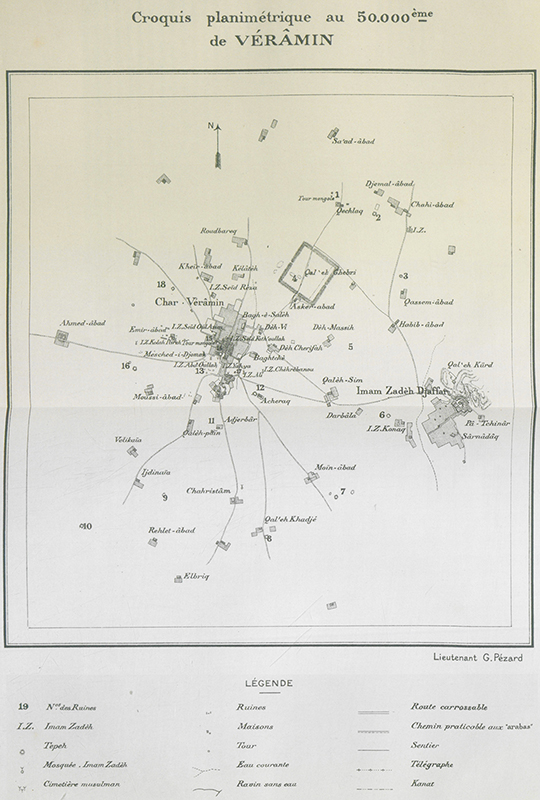

Around the turn of the twentieth century, and likely due to its proximity to Tehran and Rey, Varamin became a popular site for the excavation of antiquities. This coincided with the gradual disappearance of the central citadel (qalʿeh) from the city’s maps. This formidable structure drawn by Jules Laurens in 1848, photographed by Jane Dieulafoy in 1881, and described by Friedrich Sarre in 1897 is conspicuously absent from the 1909 map created by French archaeologist Lieutenant Georges Pézard (figs. 15–16).

Despite such losses and the poor conditions of other monuments like the congregational mosque, Varamin remained a sacred landscape with many tomb shrines. In his map of Varamin, Pézard recorded eleven emamzadehs, all indicated with “I.Z.” for “Imam Zadèh” (fig. 16).

Urbanization, Industrialization, and Preservation (1930s onward)

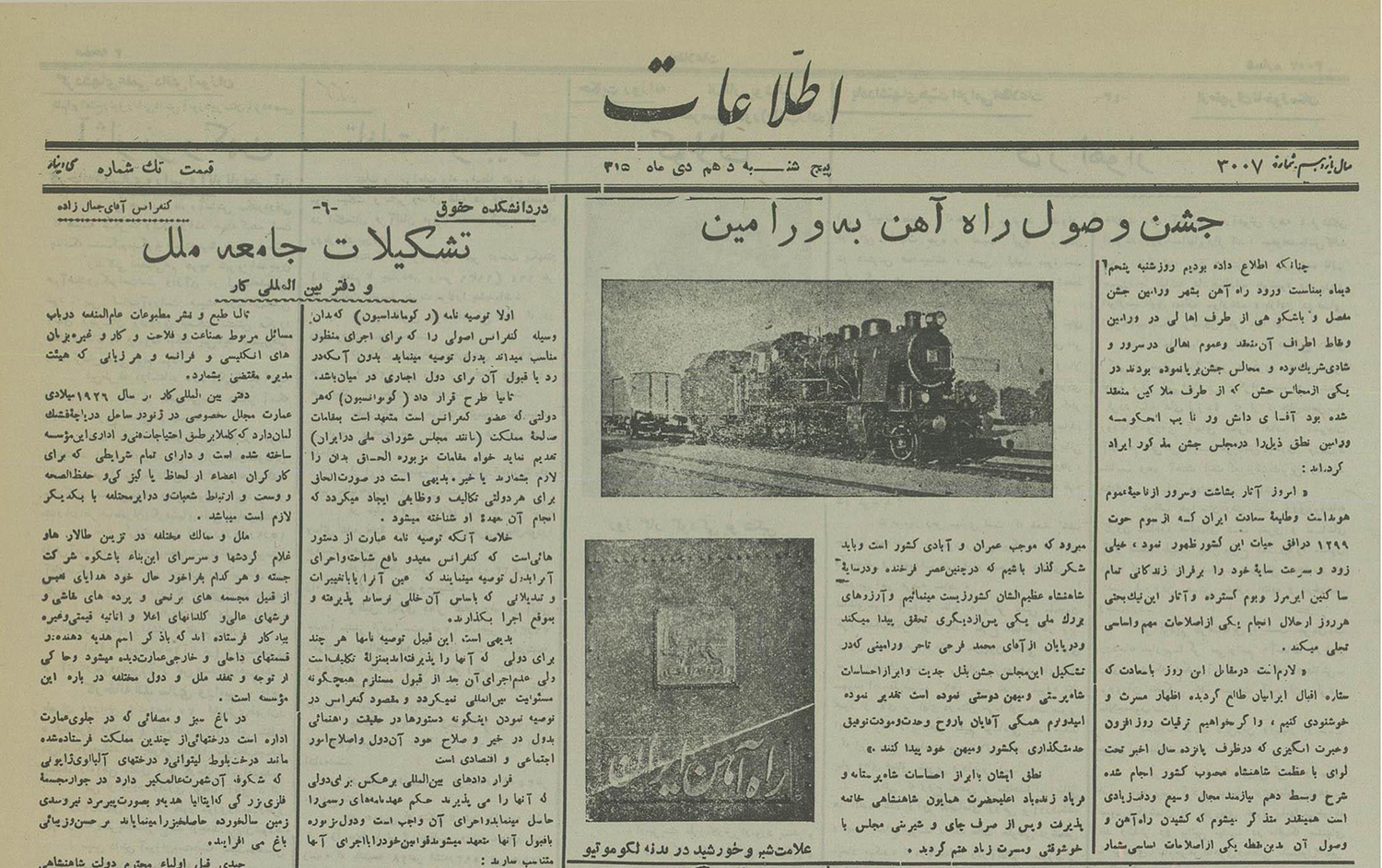

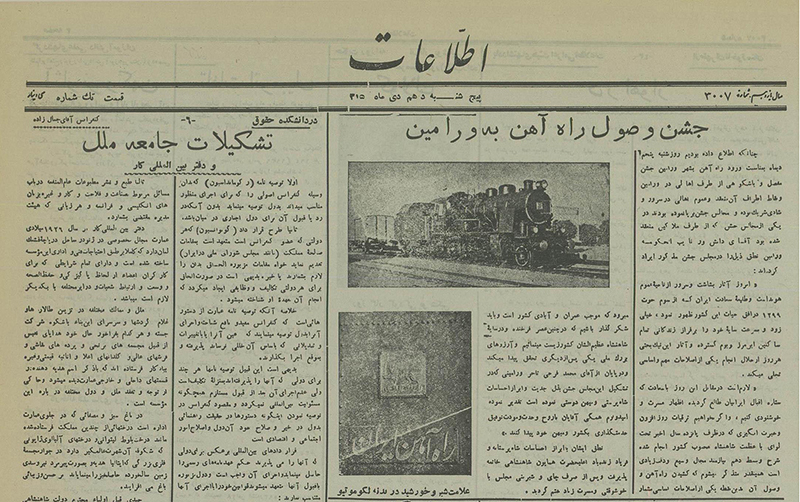

During the early Pahlavi period, and especially after the construction of the railroad in 1315 Sh/1936, Varamin emerged as an important city near the capital (fig. 17). The establishment of factories like the sugar refinery (1313 Sh/1934) (map) and oil refinery (1317 Sh/1938) (map), both located about a mile north of central Varamin, contributed to the city’s rise as an industrial hub (fig. 18).

The 1930s also saw the recognition of Varamin’s major historical buildings as national heritage (asar-e melli). The congregational mosque was registered in 1310 Sh/1931 (no. 176), ʿAlaoddin tomb tower in 1310 Sh/1931 (no. 177), Emamzadeh Yahya in 1312 Sh/1933 (no. 199), and Emamzadeh Shah Hosayn in 1318 Sh/1940 (no. 339). The Emamzadeh Yahya quickly became the focus of a major renovation (see Nakhaei and Overton), but the congregational mosque remained almost untouched until the 1340s Sh/1960s. Efforts focused on the west side, and the building underwent three rounds of excavation in 1345 Sh/1966, 1354 Sh/1975, and 1367 Sh/1988 (fig. 19). Although archaeological evidence and historical inscriptions indicate that the building’s construction and decoration were never actually completed, the west side and the entrance portal were entirely rebuilt in the 1990s, giving it its current appearance (fig. 20).50

Although what remains of Varamin’s art and architectural heritage is only a fraction of its former splendor, each remnant encapsulates a distinct phase in the city’s long history. The legacy of Shiʿi families, especially the Hosayni Varamini family, stands out as a living part of Varamin’s fabric, and many shrines, whether belonging to an emam’s descendant or a Sufi, still function as centers for gathering, remembrance, and worship.

Citation: Hossein Nakhaei, “The History of Varamin and its Shiʿi Significance, 10th–20th Centuries.” Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.

Notes

- Kleiss, “Qalʿeh Gabri bei Veramin,” 289–90. ↩

- al-Maqdisi, ʾAḥsan al-taqāsīm, 401; al-Tawhidi, Akhlāq al-vazīrayn, 376–77; Hamawi, Muʿjam al-boldān, 5: 370. ↩

- Mostawfi, Nuzhat al-qulūb, 173–78. ↩

- Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy of Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo, 182–83. ↩

- Beaumont, “Qanats on the Varamin Plain, Iran,” 177; Azari Damirchi, Joqrāfīyā-ye tārīkhī-ye Varāmīn, 7–8. ↩

- Ibn Hawqal, Ṣūrat al-ʾarḍ, 2: 379; Mostawfi, Nuzhat al-qulūb, 97; Razi, Taḍkere-ye haft eqlīm, 2: 1194. ↩

- Mostawfi, Sharh-e zendegī-ye man, 3: 283. ↩

- Estakhri, al-Masālek va al-mamālek, 123; Ibn Hawqal, Ṣūrat al-ʿarḍ, 2: 322. ↩

- Jafarian, “Tashayyoʿ dar Varāmīn,” 121–22. ↩

- Qazvini Razi, Naqḍ, 394–95; Samʿani, al-ʾAnsāb, 13: 307; Hamawi, Muʿjam al-boldān, 5: 307. ↩

- See Jafarian, “Khāndān-e Abu-Saʿd Varāmīnī.” ↩

- Qazvini Razi, Naqḍ, 200, 579. ↩

- Ravandi, Rāhat al-ṣudūr, 370. ↩

- Qazvini Razi, Naqḍ, 200, 222–23. In his twelfth century Divan (collection of Persian poetry), ʿAbdoljalil (ʿAbd al-Jalil) Qavami Razi, a local poet from Rey, highlighted Montajaboddin Hosayn’s generosity in several poems. See Qavami Razi, Dīvān, 7–12, 17–20, 169–71. ↩

- Hamawi, Muʿjam al-boldān, 3: 116–17. ↩

- Fakhroddin Razi, al-Shajarat al-mobārakah, 175–76. There are several uncertainties about the lineage of this family in genealogy books. See Khamehyar, “Molūk-e shīʿe-ye Rey va Varāmīn dar dore-ye Ilkhanī,” 433–34. ↩

- Mostawfi, Nuzhat al-qulūb, 94, 97. ↩

- Ibn al-Tiqtaqi, al-ʾAṣīlī fī ʾansāb al-ṭālibīyyīn, 285–86; Ibn al-Fuwati, Majmaʿ al-ādāb, 2: 369, 590. ↩

- Blair, “Architecture as a Source,” 221–23. ↩

- Rashidoddin Fazlollah, Jāmīʿ al-tavārīkh, 2: 792. ↩

- Razavi, Shahr, sīyāsat va eqteṣād, 367; Nakhaei, Masjed-e jāmeʿ-e Varāmīn, 42–43. ↩

- In addition to figure 4 here, see 1968.212.39. ↩

- al-Qashani, Tārikh-e Ūljeytū, 101; Nakhaei, Masjed-e jāmeʿ-e Varāmīn, 46. ↩

- Afshar, “Montakhabātī az se shāʿer-e shīʿī,” 159. ↩

- See Heydari, “Aḥsan al-kībār fī maʿrefat al-aʾemat al-aṭhār,” 31. ↩

- On the Golestan example, see Shayestefar, “Barrasī-ye moḍūʿī-ye noskhe-ye khaṭṭī-e Aḥsan al-kībār.” ↩

- This tomb was built thirteen years after ʿAlaoddin’s death. On this gap, see Blair, “Architecture as a Source,” 224–26. ↩

- Quchani, “Barrasī-ye katībe-ye ārāmgāh-e ʿAlā al-Dīn,” 63; Blair, “Architecture as a Source,” 225. ↩

- Vaziri, Tārīkh-e Varāmīn, 12–13; Khamehyar, “Molūk-e shīʿe-ye Rey va Varāmīn dar dore-ye Ilkhanī,” 434. ↩

- Ibn al-Fuwati, Majmaʿ al-ādāb, 1: 327; Nakhaei, Masjed-e jāmeʿ-e Varāmīn, 115–17. ↩

- To learn more about inscriptions referencing Shiʿi beliefs, see Kratchkovskaïa, “Notices sur les inscriptions,” 44–45; Nakhaei, Masjed-e jāmeʿ-e Varāmīn, 119–25. ↩

- Hosayni Varamini, Aḥsan al-kībār, fols. 78b, 178a; Heydari, “Aḥsan al-kībār fī maʿrefat al-aʾemat al-aṭhār,” 32. ↩

- Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy of Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo, 182–83. ↩

- Hafez-e Abru, Zobdat al-tavārīkh, 4: 609. Hosayni, Tārīkh-e owlād-e teymūr, 117. ↩

- Hafez-e Abru, Zobdat al-tavārīkh, 4: 609. On Iranian ethnic groups and tribes, see Towfiq, “ʿAŠĀYER.” On tribes in Varamin, see Amini, ʿAshāyer-e manṭaqe-ye Varāmīn. ↩

- For the inscription in the congregational mosque, see O’Kane, “Timurid Stucco Decoration,” 67–68; Nakhaei, Masjed-e jāmeʿ-e Varāmīn, 143–45. ↩

- O’Kane, “The Imāmzāda Husain Ridā at Varāmīn;” Golombek and Wilber, The Timurid Architecture of Iran and Turan, 1: 412. ↩

- The tomb of Yusof b. Hosayn Razi, also referred to as the Emamzadeh Yusof Reza, is believed to be the burial place of Yusof b. Hosayn Razi, a prominent Sufi who lived in the ninth century. See Rezvan, “Boqʿe-ye Yūsof Rezā.” Regarding the Emamzadeh Hosayn Reza, Tajik and Atri claim that there was a khanqah (a communal space for Sufis to worship and meditate) in its northern side, which no longer exists. Bonyad Iranshenasi, Shomārī az boqʿehā, 125. ↩

- Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, Rasāʾel, 206–7. ↩

- Razi, Taḍkere-ye haft eqlīm, 2: 1156. ↩

- Amin al-Sultan, “Sharḥ-e Khwār va qesmatī az Varāmīn,” 3: 365. ↩

- See Morimoto, “The Earliest ʿAlid Genealogy for the Safavids.” ↩

- This door was stolen at some point after its inscription was transcribed by companions of Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh during their visit in 1279/1863 (see History of Evolution). ↩

- Moeini, “Zavareʾī, ʿAli ebn-e Hasan.” ↩

- Monshi-ye Qomi, Kholāṣat al-tavārīkh, 1: 607; 2: 874. ↩

- Eskandar Beg, Tārīkh-e ʿālamārā, 155; Monshi-ye Qomi, Kholāṣat al-tavārīkh, 2: 709. ↩

- Fraser, A Winter’s Journey, 2: 69; Eastwick, Three Years’ Residence in Persia, 1: 285–86; Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, Rasāʾel, 202-9. ↩

- On natural disasters, see Chodzko, “Une Excursion de Téhéran aux Pyles Caspiennes,” 291. On devastating floods during the Qajar period, see Amin al-Sultan, “Sharḥ-e Khwār va qesmatī az Varāmīn,” 3: 368. ↩

- Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, Rasāʾel, 202. ↩

- For an analysis of this restoration, see Nakhaei, Masjed-e jāmeʿ-e Varāmīn, 80–89, 94–100. ↩

Bibliography (Persian, Arabic)

- آذری دمیرچی، علاءالدین. جغرافیای تاریخی ورامین. تهران: بی نا، ۱۳۴۸ش. [Azari Damirchi, Joqrāfīyā-ye tārīkhī-ye Varāmīn] [WorldCat] [Lib.ir]

- ابن حوقل. صورة الأرض. القسم الثانی. بیروت: دار مکتبة الحیاة، ۱۹۹۲م. [Ibn Hawqal, Ṣūrat al-ʾarḍ] [Internet Archive]

- ابن طقطقی الحسنی، صفیالدین محمد بن تاجالدین علی. الأصیلی فی أنساب الطالبیین. تحقیق مهدی رجایی. قم: کتابخانه آیتالله مرعشی نجفی، ۱۳۷۶ش. [Ibn al-Tiqtaqi, al-ʾAṣīlī fī ʾansāb al-ṭālebīyyīn] [Internet Archive] [WorldCat]

- ابن فوطی، عبدالرزاق بن احمد. مجمع الآداب فی معجم الألقاب. به تحقیق محمد الکاظم. المجلد الاول و الثانی. تهران: وزارت فرهنگ و ارشاد اسلامی، ۱۳۷۴ش. [Ibn al-Fuwati, Majmaʿ al-ādāb] [WorldCat] [Noorlib]

- اسکندربیگ ترکمان. تاریخ عالم آرای عباسی. [تهران:] دارالطباعه آقا سید مرتضی، ۱۳۱۴ق. [Eskandar Beg, Tārīkh-e ʿālamārā] [WorldCat] [Noorlib]

- اصطخری، ابراهیم بن محمد. المسالک و الممالک. تحقیق محمد جابر عبدالعال الحینی. قاهره: الهیئه العامه لقصور الثقافه، ۲۰۰۴م. [Estakhri, al-Masālek va al-mamālek] [WorldCat] [Noorlib]

- اعتمادالسلطنه، محمدحسن خان. رسائل اعتمادالسلطنه. تدوین میرهاشم محدث. تهران: اطلاعات، ۱۳۹۱ش. [Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, Rasāʾel] [WorldCat] [Lib.ir]

- افشار، ایرج. «منتخباتی از سه شاعر شیعی قرن هشتم.» در جشننامهٔ هانری کربن، زیر نظر سید حسین نصر، ۱۵۱-۶۹. تهران: مؤسسه مطالعات اسلامی دانشگاه مکگیل، ۱۳۵۶ش. [Afshar, “Montakhabātī az se shāʿer-e shīʿī”] [WorldCat] [Ketabnak]

- امینالسلطان، علیاصغر خان. «شرح خوار و قسمتی از ورامین.» در محمدحسن خان اعتمادالسلطنه، مطلع الشمس، ج۳، ۳۳۹-۶۹. تهران: پیشگام، ۱۳۶۲ش. [Amin al-Sultan, “Sharḥ-e Khwār va qesmatī az Varāmīn”] [HathiTrust]

- امینی، محمد. عشایر منطقه ورامین در گذشته و حال. ورامین: واج، ۱۳۸۴ش. [Amini, ʿAshāyer-e manṭaqe-ye Varāmīn] [Lib.ir]

- بنیاد ایرانشناسی. شماری از بقعهها، مرقدها و مزارهای استان تهران و البرز. ج۲: شهرستانهای شهریار، فیروزکوه، کرج، نظرآباد و ورامین. طرح، بررسی و تدوین حسن حبیبی. تهران: بنیاد ایرانشناسی، ۱۳۸۹ش. [Bonyad Iranshenasi, Shomārī az boqʿehā] [WorldCat] [Lib.ir]

- توحیدی، ابی حیان علی بن محمد. أخلاق الوزیرین، مثالب الوزیرین الصاحب بن عباد و ابن العمید. حققه و علق حواشیه محمد بن تاویت الطنجی. بیروت: دار صادر، ۱۴۱۲ق/ ۱۹۹۲م. [al-Tawhidi, Akhlāq al-vazīrayn] [Internet Archive] [Noorlib]

- «جشن وصول راهآهن به ورامین.» اطلاعات، ۱۵ دی ۱۳۱۵ش. [“Jashn-e vuṣūl”] [Ettelaʿat Publications]

- جعفریان، رسول. «تشیع در ورامین.» کیهان اندیشه ۷۵ (آذر و دی ۱۳۷۶ش): ۲۷-۱۱۶. [Jafarian, “Tashayyoʿ dar Varāmīn] [ensani.ir]

- جعفریان، رسول. «خاندان ابوسعد ورامینی و تلاش برای آبادانی حرمین شریفین.» میقات حج ۱ (پاییز ۱۳۷۱ش): ۷۰-۱۶۵. [Jafarian, “Khāndān-e Abu-Saʿd Varāmīnī”] [Noormags]

- حافظ ابرو، عبدالله بن لطف الله. زبدة التواریخ. مقدمه و تصحیح و تعلیقات کمال حاج سید جوادی. ج ۴. تهران: وزارت فرهنگ و ارشاد اسلامی، ۱۳۸۰ش. [Hafez-e Abru, Zobdat al-tavārīkh] [WorldCat] [Noorlib]

- حسینی، جعفر بن محمد. تاریخ اولاد تیمور از تواریخ ملوک و انبیاء. مقدمه و تصحیح عباس زریاب خوئی. به اهتمام نادر مطلبی کاشانی. قم: مورخ، ۱۳۹۳ش. [Hosayni, Tārīkh-e owlād-e teymūr] [WorldCat] [Lib.ir]

- حسینی ورامینی، محمد بن ابی زید بن عربشاه. أحسن الکبار فی معرفه الأئمه الأطهار. نسخه خطی ش ۴۱۵۹، کتابخانه و موزه ملی ملک. [Hosayni Varamini, Aḥsan al-kībār] [Malek Museum, manuscript no. 4159, dated 948/1541–42] [Internet Archive]

- حموی، یاقوت. معجم البلدان. المجلد الثالث و الخامس. بیروت: دار صادر، ۱۹۹۵م. [Hamawi, Muʿjam al-boldān] [WorldCat] [Noorlib]

- حیدری یساولی، علی. «أحسن الکبار فی معرفه الائمه الاطهار، متنی از نیمۀ نخست قرن هشتم هجری با نگاهی به نسخ خطی موجود از آن در کتابخانه محدث ارموی.» کتاب ماه کلیات ۱۱۹ (آبان ۱۳۸۶ش): ۲۸-۳۳. [Heydari, “Aḥsan al-kībār fī maʿrefat al-aʾemat al-aṭhār”] [Noormags]

- خامهیار، احمد. «ملوک شیعه ری و ورامین در دوره ایلخانی.» کتابگزار ۱ (بهار ۱۳۹۵ش): ۳۸-۴۳۳. [Khamehyar, “Molūk-e shīʿe-ye Rey va Varāmīn dar dore-ye Ilkhanī”] [Noormags]

- دانیل، ویکتور، بیژن شافعی و سهراب سروشیانی. معماری نیکلای مارکف. تهران: انتشارات دید، ۱۳۸۲ش. [Daniel, Meʿmāri-ye Nikolai Markov] [WorldCat]

- رازی، امین احمد. تذکرۀ هفت اقلیم. تصحیح، تعلیقات و حواشی محمدرضا طاهری. ج ۲. تهران: سروش، ۱۳۷۸ش. [Razi, Taḍkere-ye haft eqlīm] [WorldCat] [Lib.ir] [Noorlib, old edition]

- راوندی، محمد بن علی. راحة الصدور و آیة السرور در تاریخ آل سلجوق. تصحیح مجتبی مینوی. تهران: امیرکبیر، ۱۳۶۴ش. [Ravandi, Rāhat al-ṣudūr] [WorldCat] [Noorlib]

- رجبی، فاطمه. جلوه هنر شیعی در نگارههای عصر صفوی. تهران: شرکت انتشارات سوره مهر، ۱۳۹۵ش. [Rajabi, Jelve-ye honar-e shīʿī] [WorldCat]

- رشیدالدین فضل الله بن عماد الدوله ابوالخیر. جامع التواریخ. به کوشش بهمن کریمی. ج ۲. تهران: اقبال، ۱۳۳۸ش. [Rashidoddin Fazlollah, Jāmīʿ al-tavārīkh] [WorldCat, new edition]

- رضوان، همایون. «بقعه یوسف رضا ،بنایی ناشناخته از دوران ایلخانی.» اثر ۲۸ (۱۳۷۶ش):۴۰-۴۸. [Rezvan, “Boqʿe-ye Yūsof Rezā”] [ensani.ir]

- رضوی، ابوالفضل. شهر، سیاست و اقتصاد در عهد ایلخانان. تهران: امیرکبیر، ۱۳۸۸ش. [Razavi, Shahr, sīyāsat va eqteṣād] [WorldCat]

- سمعانی، عبدالکریم بن محمد. الأنساب. تقدیم و تعلیق عبدالله عمر البارودی. الجزء الخامس. بیروت: دارالجنان، ۱۴۰۸ق/۱۹۸۸م. [Samʿani, al-ʿAnsāb] [Internet Archive]

- شایستهفر، مهناز. «بررسی موضوعی نسخهی خطی احسن الکبار شاهکار نگارگری مذهبی دوره صفویه.» کتاب ماه هنر ۱۳۸ (اسفند ۱۳۸۸ش): ۱۴-۲۶. [Shayestefar, “Barrasī-ye moḍūʿī-ye noskhe-ye khaṭṭī-e Aḥsan al-kībār”] [Noormags]

- فخر رازی، محمد بن عمر. الشجرة المبارکه فی أنساب الطالبیه. تحقیق مهدی رجایی. قم: کتابخانه آیت الله مرعشی نجفی، ۱۳۷۷ش. [Fakhroddin Razi, al-Shajarat al-mobārakah] [Internet Archive]

- قاشانی، ابوالقاسم عبدالله بن محمد. تاریخ اولجایتو. به اهتمام مهین همبلی. تهران: بنگاه ترجمه و نشر کتاب، ۱۳۴۸ش. [al-Qashani, Tārīkh-e Ūljeytū] [WorldCat] [Lib.ir]

- قزوینی رازی، عبدالجلیل. النقض معروف به بعض مثالب النواصب فی نقض «بعض فضائح الروافض.» تصحیح میرجلالالدین محدث. قم: دارالحدیث، ۱۳۹۱ش. [Qazvini Razi, Naqḍ] [WorldCat] [Noorlib]

- قوامی رازی، بدرالدین. دیوان شرف الشعراء بدرالدین قوامی رازی. تصحیح میر جلال الدین حسینی ارموی. بی جا: چاپخانۀ سپهر، ۱۳۳۴ش. [Qavami Razi, Dīvān] [WorldCat, new edition] [Noorlib]

- قوچانی،عبدالله. «بررسی کتیبه آرامگاه علاءالدین.» اثر ۱۵-۱۶ (۱۳۶۷ش): ۵۹-۷۱. [Quchani, “Barrasī-ye katībe-ye ārāmgāh-e ʿAlā al-Dīn”]

- مستوفی، حمدالله بن ابیبکر. نزهة القلوب. به کوشش محمد دبیرسیاقی. قزوین: حدیث امروز، ۱۳۸۱ش. [Mostawfi, Nuzhat al-qulūb] [WorldCat] [Noorlib] [Internet Archive, old edition]

- مستوفی، حمدالله بن ابیبکر. نزهة القلوب: المقالة الثالثة در صفت بلدان و ولایت و بقاع . تصحیح گای لیسترانج. تهران: دنیای کتاب، ۱۳۶۲ش. [Mostawfi, Nuzhat al-qulūb: al-maqālat al-thālethah] [WorldCat] [Lib.ir]

- مستوفی، عبدالله. شرح زندگی من: تاریخ اجتماعی و اداری دورۀ قاجاریه. ج۳. تهران: زوار،۱۳۸۴ش. [Mostawfi, Sharh-e zendegī-ye man] [WorldCat] [Noorlib]

- معینی، محسن. «زوارهای، علی بن حسن.» دانشنامه جهان اسلام، ۱۹ اسفند ۱۴۰۲ش. [Moeini, “Zavareʾī, ʿAli ebn-e Hasan”] [Encyclopaedia of the World of Islam]

- مقدسی، شمسالدین ابی عبدالله محمد. أحسن التقاسیم فی معرفة الأقالیم. قاهره: مکتبه مدبولی، ۱۴۱۱ق/۱۹۹۱م. [Al-Maqdisi, ʾAḥsan al-taqāsīm] [Internet Archive]

- منشی قمی، احمد بن حسین. خلاصة التواریخ. تصحیح احسان اشراقی. ج۱. تهران: دانشگاه تهران، ۱۳۸۳ش. [Monshi-ye Qomi, Kholāṣat al-tavārīkh] [WorldCat] [Noorlib]

- نخعی، حسین. مسجد جامع ورامین: بازشناسی روند شکلگیری و سیر تحول. تهران: دانشگاه شهید بهشتی و روزنه، ۱۳۹۷ش. [Nakhaei, Masjed-e jāmeʿ-e Varāmīn] [WorldCat] [Academia]

- وزیری، سعید. تاریخ ورامین. ورامین: بی نا، ۱۳۵۸ش. [Vaziri, Tārīkh-e Varāmīn] [Lib.ir]

Bibliography (English, French, German)

- Beaumont, Peter. “Qanats on the Varamin Plain, Iran.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 45 (September 1968): 169–79. [JSTOR]

- Blair, Sheila. “Architecture as a Source for Local History in the Mongol Period: The Example of Warāmīn.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 26, 1–2 (2016): 215–29. [JSTOR]

- Blair, Sheila S. and Jonathan M. Bloom. “Varamin.” In Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture, 391. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. [Oxford Reference]

- Bosworth, C. Edmund. “Warāmīn.” In Encyclopaedia of Islam New Edition Online (EI-2 English), edited by Peri J. Bearman et al., vol. 11, 143–44. Leiden: Brill, 2002. [Internet Archive]

- Chodzko, M. Alexandre. “Une Excursion de Téhéran aux Pyles Caspiennes.” In Nouvelles annales des voyages. Tome. 127I. Paris: E. Thunot, 1850. [BnF]

- Clavijo, Ruy Gonzáles de. Narrative of the Embassy of Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo to the Court of Timour at Samarcand. Translated by Clements R. Markham. London: Hakluyt Society, 1859. [Internet Archive]

- Eastwick, Edward B. Journal of a Diplomat’s Three Years’ Residence in Persia, vol. 1. London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1864. [Internet Archive]

- Eshragh, Abdol-Hamid, ed. Masterpieces of Iranian Architecture. Tehran: Offset Press, 1970. [WorldCat]

- Fraser, James Baillie. A Winter’s Journey from Constantinople to Tehran, vol. 2. London: Richard Bentley, 1838. [Internet Archive]

- Golombek, Lisa and Donald Wilber. The Timurid Architecture of Iran and Turan, vol. 1. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988. [WorldCat]

- Kleiss, Wolfram. “Karawanenwege in Iran.” Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran 20 (1987): 327–30. [ÖAW]

- Kleiss, Wolfram. “Qalʿeh Gabri bei Veramin.” Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran 20 (1987): 289–307. [WorldCat]

- Kratchkovskaïa, Vera. “Notices sur les inscriptions de la mosquée Djoum’a a Véramine.” Revue des etudes Islamiques 5 (1931): 25–58. [WorldCat]

- Minorsky, Vladimir. “Warāmīn.” In E. J. Brill’s First Encyclopedia of Islam 1913–1936, edited by Martijn Theodoor Houtsma et al., vol. 8, 1122–23. Leiden: Brill, 1987. [Internet Archive]

- Morimoto, Kazuo. “The Earliest ʿAlid Genealogy for the Safavids: New Evidence for the Pre-Dynastic Claim to Sayyid Status.” Iranian Studies 43, 4 (2010): 447–69. [JSTOR]

- O’Kane, Bernard. “The Imāmzāda Husain Ridā at Varāmīn.” Iran 16 (1978): 175–77. [JSTOR]

- O’Kane, Bernard. “Timurid Stucco Decoration.” Annales Islamologiques 20 (1984): 61–84. [persee.fr]

- Pézard, Georges and Jules-Georges Bondoux. “Mission de Téhéran.” In M. C. Soutzo et al., Délégation en Perse: Mémoires, Tome. XII: Recherches Archéologiques, 51–64. Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1911. [Internet Archive]

- Sarre, Friedrich. Denkmäler persischer Baukunst. Berlin: Wasmuth, 1910. [Heidelberg University]

- Towfiq, F. “ʿAŠĀYER.” Encyclopædia Iranica, December 15, 1987, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/asayer-tribes.