If some day a noble soul reads this... Documenting the yadegari of the Tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin

Nazanin Shahidi Marnani

Translated from Persian by Farshad Sonboldel

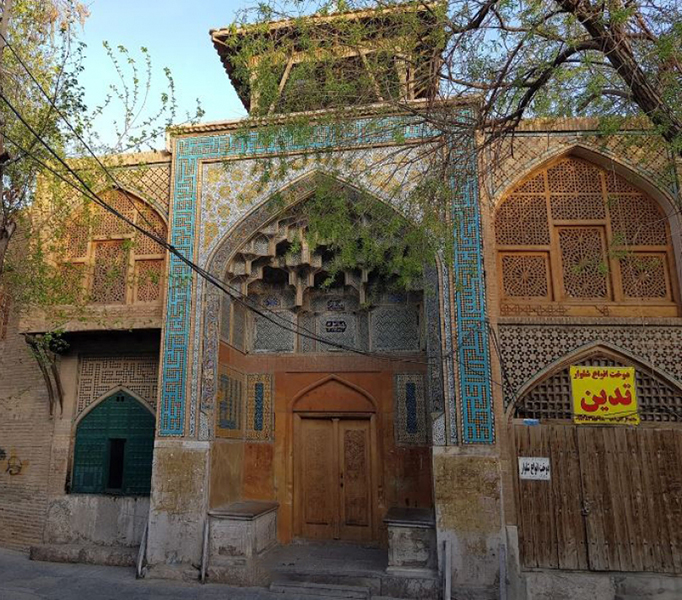

When we enter an Islamic building, inscriptions (کتیبهها) are usually among the first things that catch the eye. Inscriptions serve as a kind of official medium (رسانه) for conveying information about the building’s creators. Often, they state the name of the patron, architect, master builder, and date of construction, as well as direct and indirect references to the builders’ beliefs, motivations, and other aspects. Inscriptions are not the only written media in historical buildings, however. When looking at historical buildings, if we take a step forward and look more closely, we often find short messages on the walls: memories (یادگار, yadegar) of people who have entered the building over successive centuries, paused, and departed. These yadegari (یادگاری, pl. یادگاریها) are a way to hear the countless voices of people who visited the building centuries ago and were its true users: believers, seminary students, lovers, scholars, and travelers. The walls have been vast, free, and well-viewed pages, and for someone who wants to convey a name or message for posterity, what could be better?

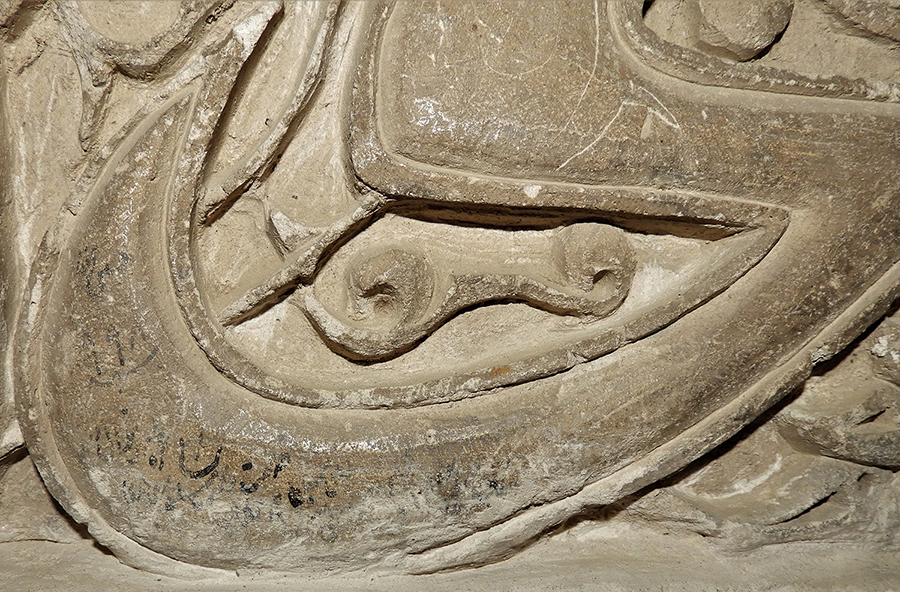

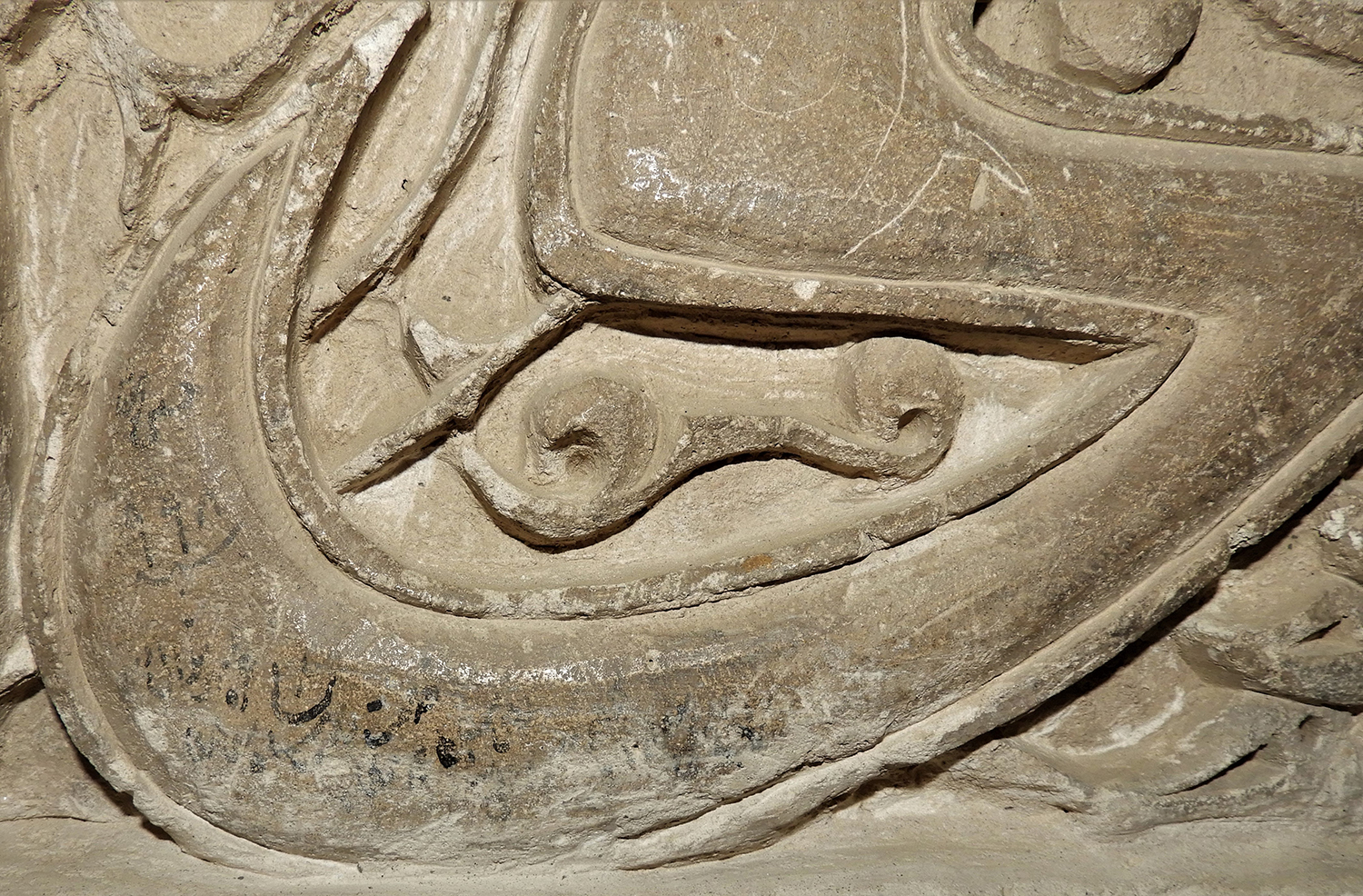

In research on historical buildings, less attention has been paid to yadegari, but the reality is that these faded and brief informal inscriptions are a medium for knowing the users of the building, and sometimes even provide new data about the building itself. Although recording a memory (یاد) and name is the common motivation for most of these writings, their content is diverse. The yadegari have two main categories: visual yadegari and textual yadegari. Visual yadegari, which are the work of the illiterate part of society, are sometimes more numerous than textual yadegari, and examples can be seen on the walls of the Masjed-e Jameʿ (congregational mosque) in Saveh (map), Masjed-e Sarkucheh Mohammadiyeh in Naʾin (map), Shrine of Pir-e Bakran (map), and many other buildings (figs. 1–3). These images, which are mostly carved on the stucco (گچ) walls, depict shapes of plants, animals, and humans, symbols that are worth examining in their own right.

The textual yadegari left by literate individuals on the walls can be divided into several thematic categories:

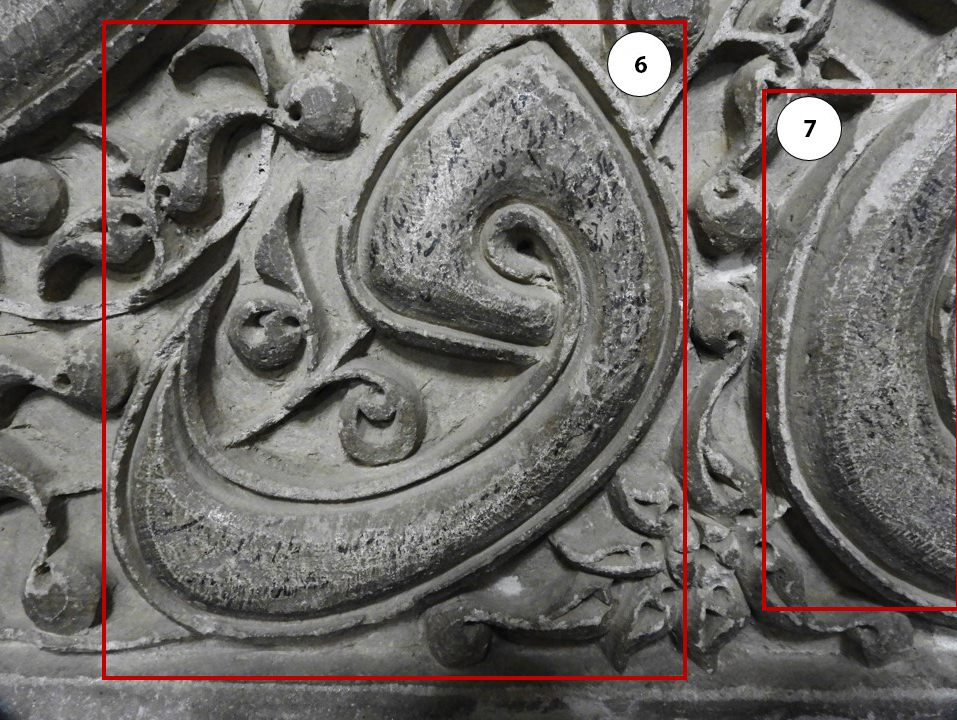

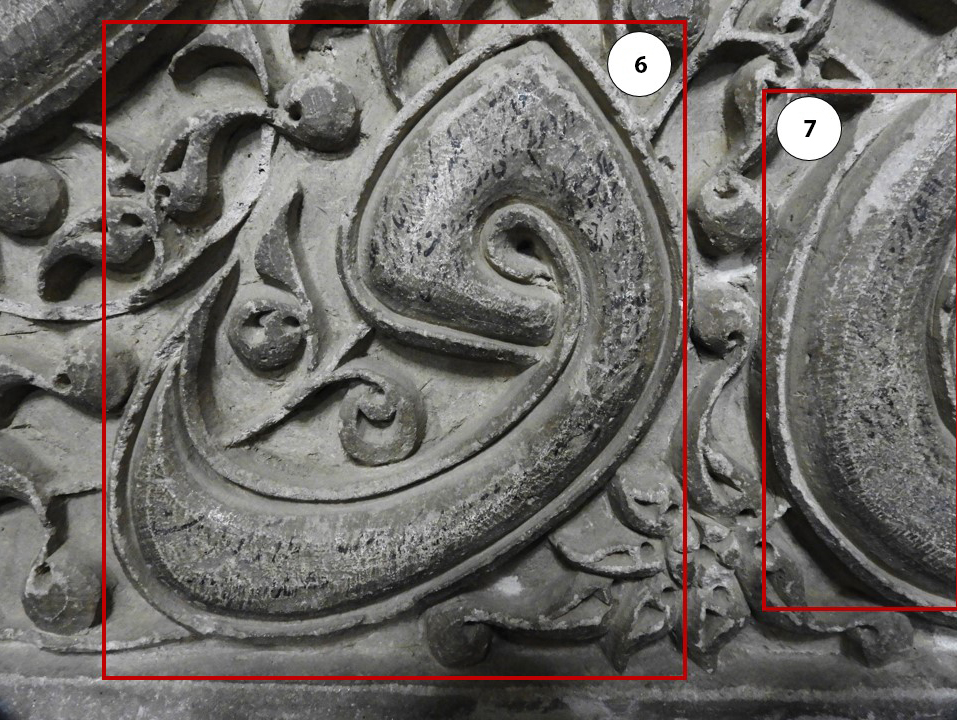

1. A major part of these yadegari, especially when we encounter a religious building, are prayers written in Persian, Arabic, or a combination of the two. These yadegari are either prayers for oneself and others or requests for prayers from visitors and readers. In the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin, most of the yadegari are of this kind and mostly in the form of Persian poetic verses (yadegari 1, 3, 6, and 7).

2. The second category of inscriptions concerns the brevity of life, the instability of the world, and advice to avoid attachment. This category is also mostly in verse and in Persian, sometimes from known poets and sometimes from famous verses of the time. Perhaps the most famous verse written on the walls of buildings in Iran regarding the brevity of life is this one:

این نوشتم تا بماند یادگار / من نمانم خط بماند روزگار

I wrote this so that it endures as a yadegari / I won’t be around, but my words will remain

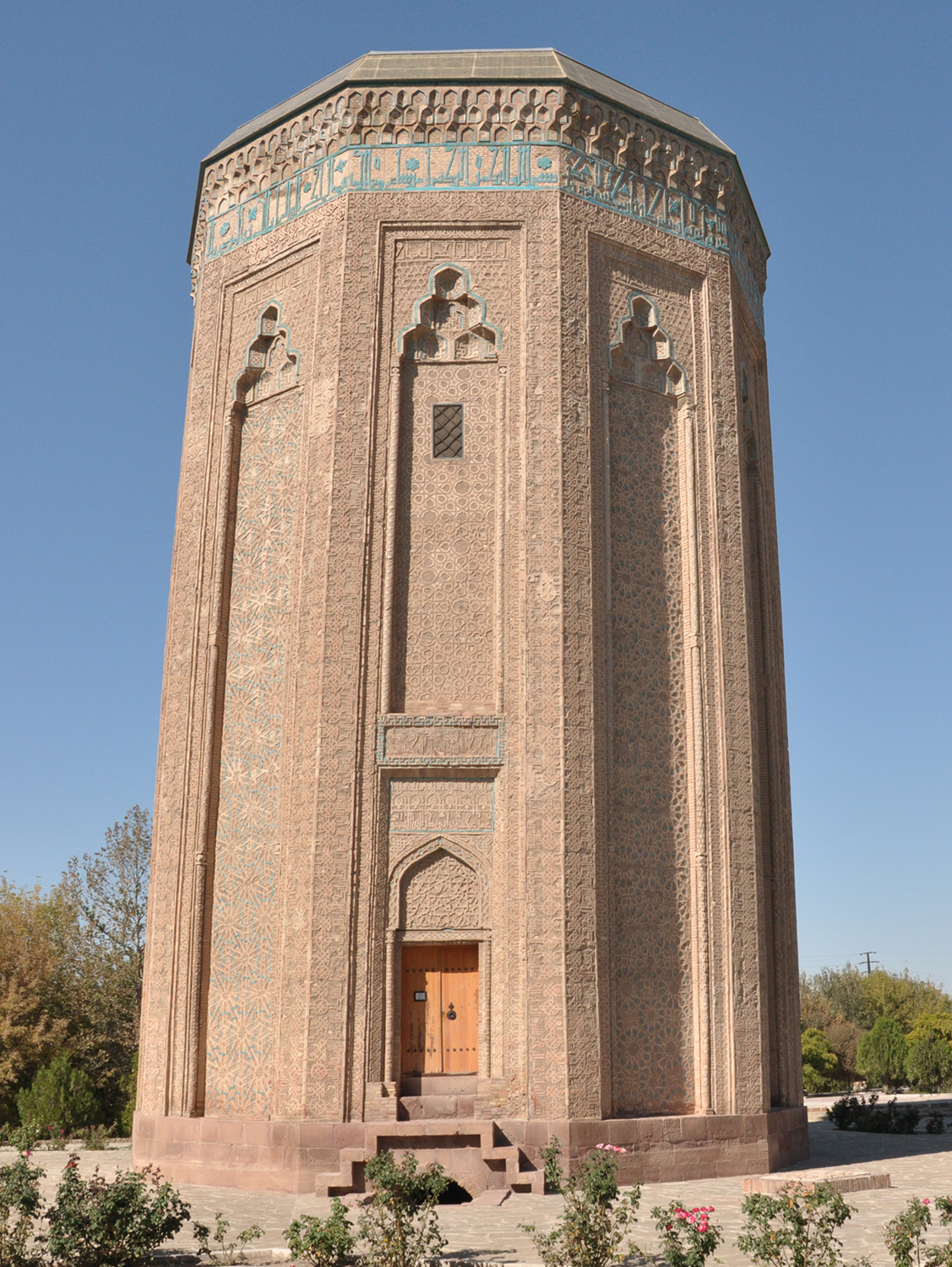

Examples of this verse can be found in buildings across various regions, from Nakhchivan to Esfahan, Khorasan, and Transoxiana, and it has also been written in the Emamzadeh Yahya (yadegari 1 and 16). This theme has been used not only in yadegari but also sometimes in a building’s official inscriptions and objects, such as water basins (سنگاب, cat. no. 21) and tombstones (سنگ مزار). In The Appearance of Persian on Islamic Art, Bernard O’Kane, professor of Islamic art and architecture at the American University in Cairo, includes an inscription with this poem (with slight variation) from the Mausoleum of Moʾmeneh Khatun in Nakhchivan (map) dated 582/1186 (fig. 4–5):

ما بگردیم پس بماند روزگار / ما بمیریم این بماند یادگار

We will return, time will remain / We shall pass away—may this remain as a yadegari1

[Translator’s gloss: gardidan (گردیدن) here means to die. Another translation of the first hemistich of the couplet (beyt, بیت) is: We shall pass away, but the world will remain.]

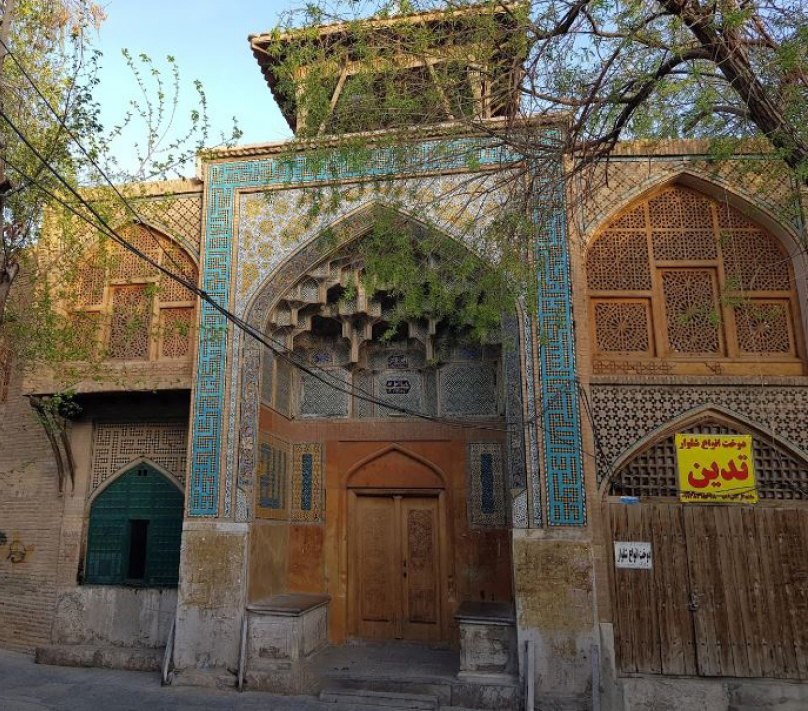

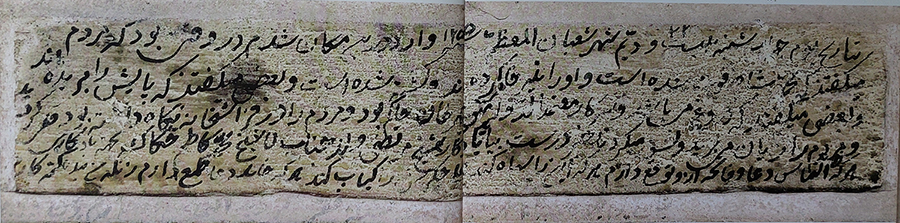

3. Complaints about the times are also common themes of the wall writings (دیوارنوشتها). This category often includes verses expressing grievances about life. Sometimes, however, there are examples where the writer briefly narrates their life story or the calamities of their time, including war, periods of famine, and the tyranny of kings. These types of yadegari are not numerous but are very valuable and provide information about the conditions and thoughts of people of the era. An example of this can be seen on the wall of the Masjed-e ʿAli Qoli Agha in Esfahan (map), where the yadegari recounts the rumor of Mohammad Shah’s death in 1255/1839 and the panic of the city’s residents (figs. 6–7).2

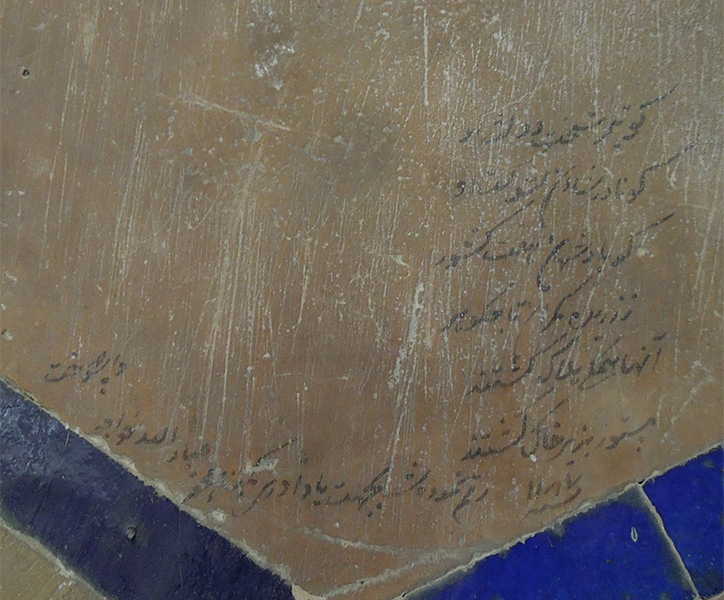

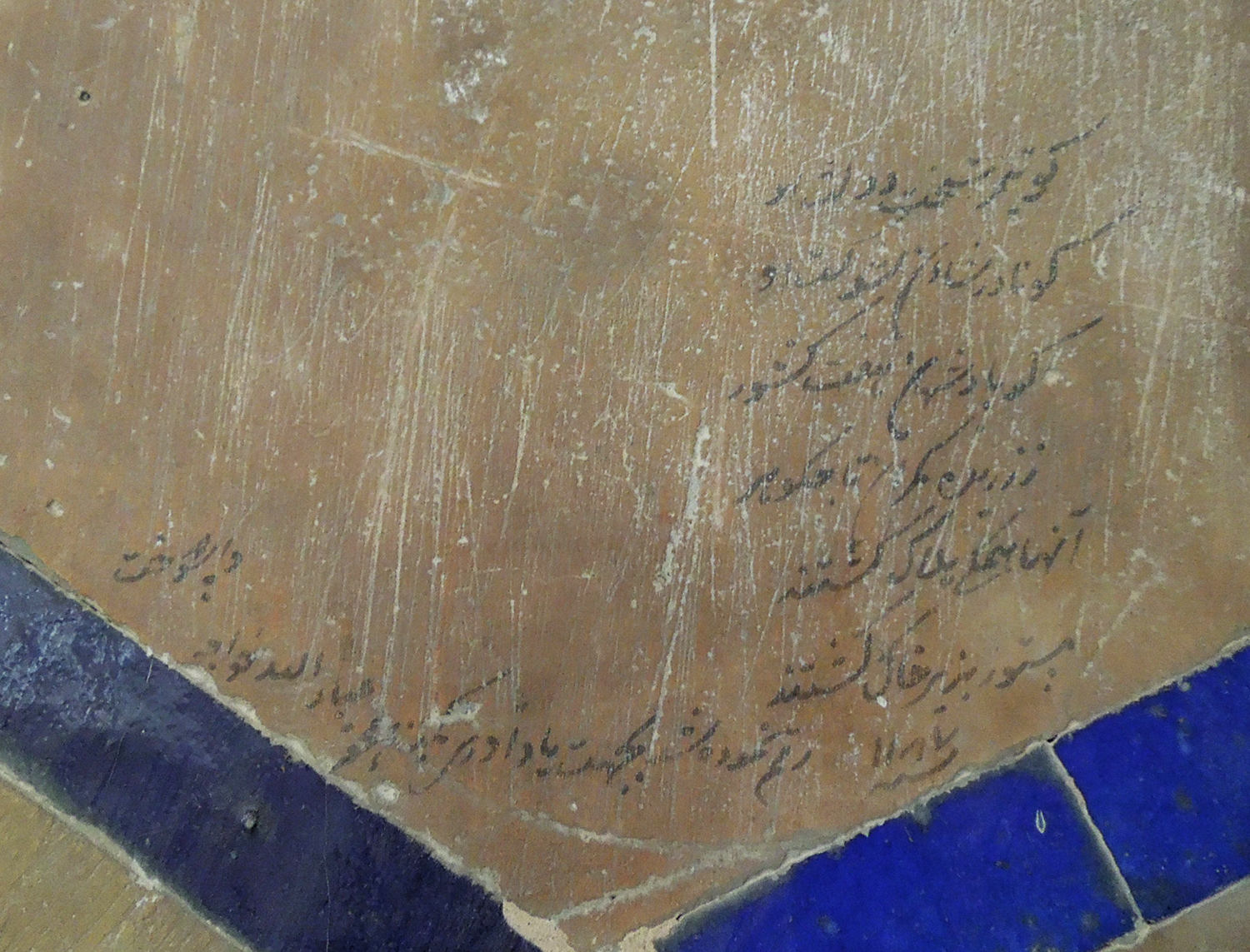

Another example is in the Rukhabad Mausoleum in Samarkand (map), a few steps away from Timur’s [r. 1370–1405] tomb. Among the wall inscriptions of the building, the text of one of the yadegari is a sign of people’s disgust with Timur and Nader Shah [r. 1736–47] (figs. 8–9).3

کو تیمُر سخت و دولت او / کو نادر شاه و شوکت او

کو پادشهان هفت کشور / زرینکمران تاج گوهر

آنان همگی هلاک گشتند / مستور به زیر خاک گشتند

سنه ۱۱۸۷ رقم نموده شد جهت یادآوری کمینه محقر عبادالله خواجه ...

Where is cruel Timur and his power? / Where is Nader Shah and his majesty?

Where are the kings of the seven realms? / With golden belts and jewelled crowns

They all perished / they are concealed within the earth.

The year 1187 [1773–74] was inscribed for remembrance by the humble, lowly servant of God, Khajeh...

In pilgrimage sites and madrasas that were destinations for pilgrims and students from cities near and far, expressions of homesickness in the yadegari illuminate somewhat the geographical range of a building’s users.

4. The fourth category, which is not as numerous as the others but very noteworthy, consists of yadegari describing the day the writer came to the building and wrote a few lines on the wall to record the memory. These yadegari often begin with the date and names of the writer’s companions, continue with a brief description of the day’s memory, and end with the writer’s name. The value of these yadegari lies in the fact that they show details of the building’s function during the period when the memory was recorded. For example, examining the yadegari of the Madreseh-ye Chahar Bagh in Esfahan (map) reveals that by the middle of the Qajar period, the school had more or less lost its original function and become a recreational spot for the city’s ordinary people (for more on this, see the abstract of my lecture in 1396 Sh/2018) (figs. 10–11).

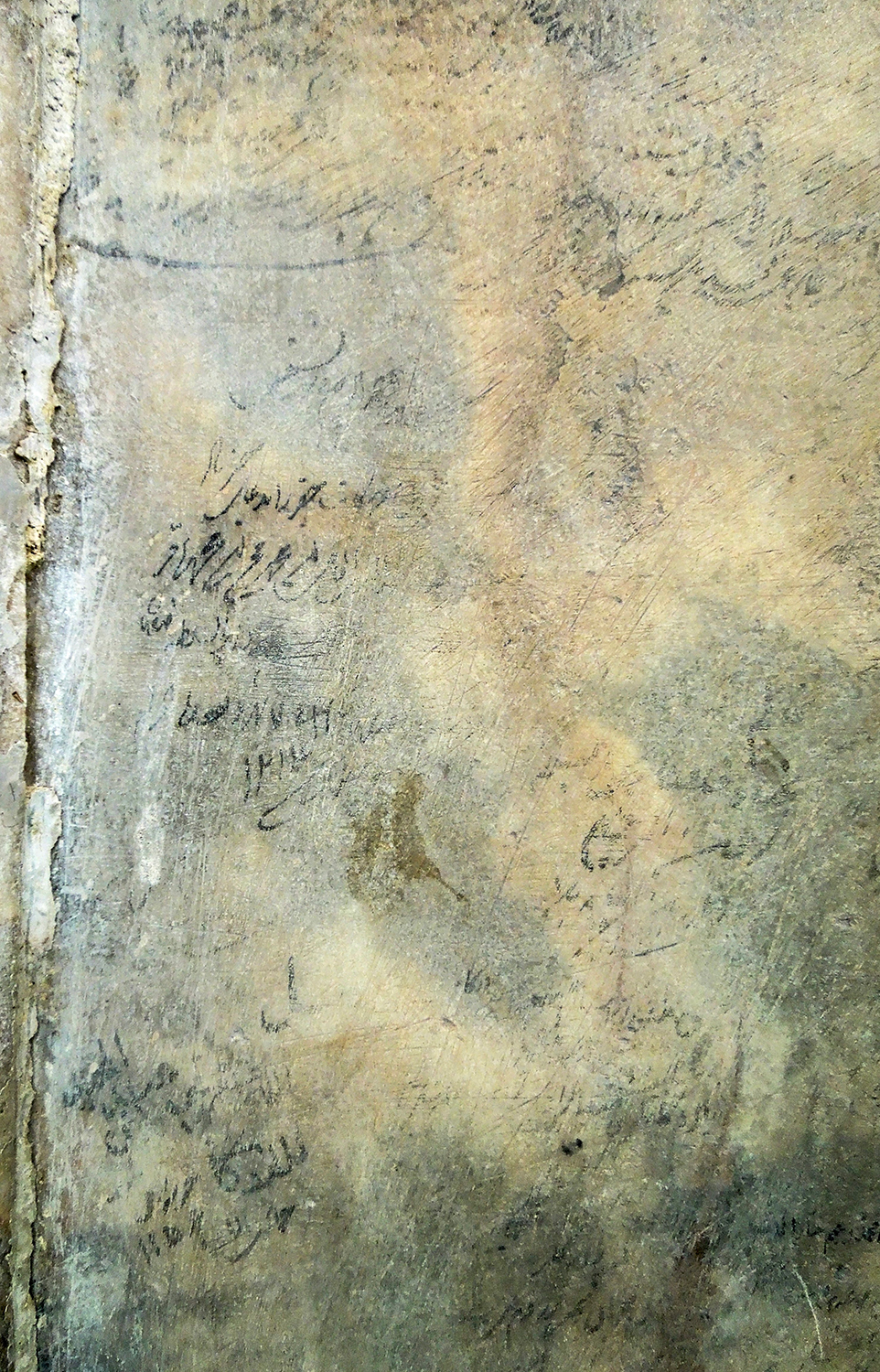

Yadegari are often not lasting inscriptions. Many of them have gradually disappeared due to disagreements of later readers, to make room for new inscriptions, due to the quality of the ink, or even during the process of contemporary restoration. For this reason, what still remains on the walls of historical buildings is very valuable, and documenting and reading these yadegari alongside other architectural documents is essential.

Introduction to the Yadegari of the Emamzadeh Yahya

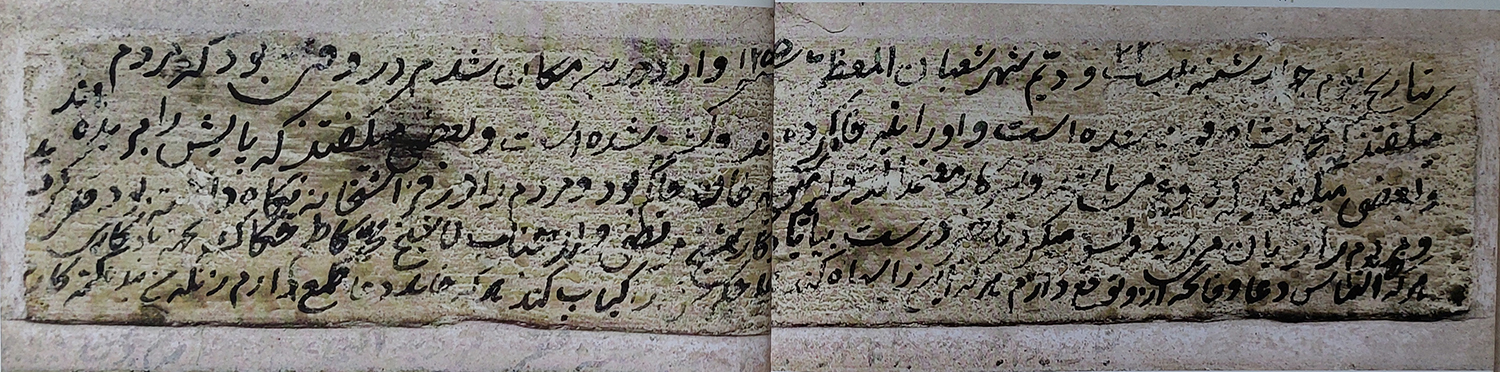

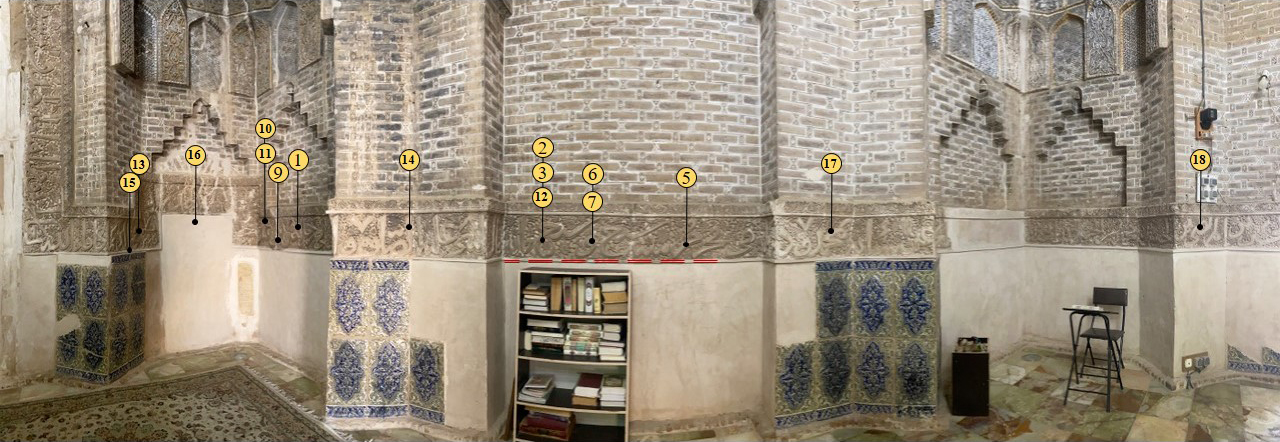

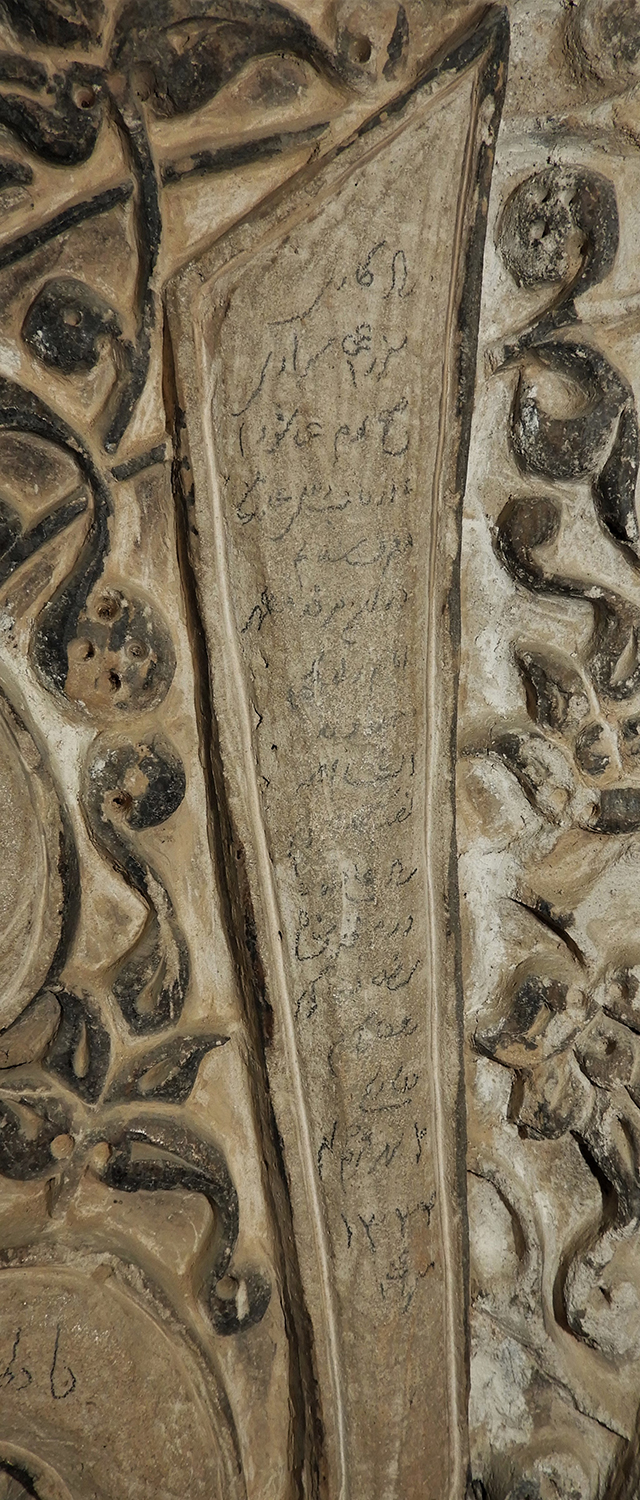

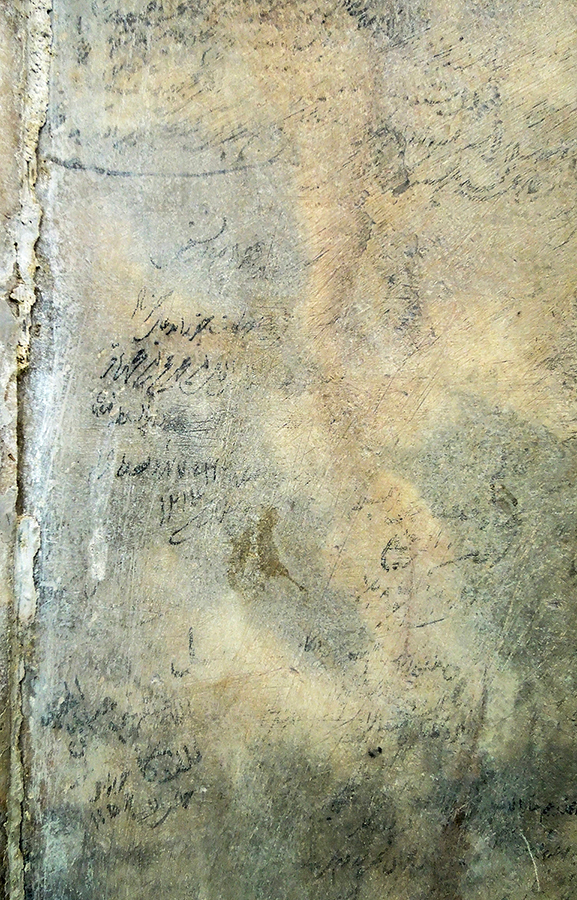

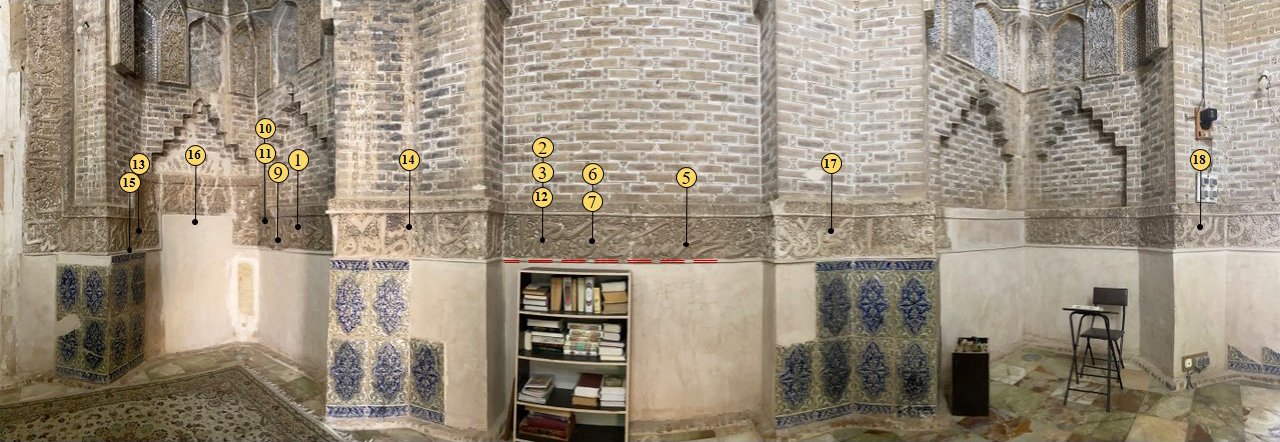

In the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya, traces of a number of yadegari can be seen on the stucco inscription dated 707/1307. In the present project, we decided to document these yadegari as much as possible. Most of the yadegari are severely damaged, faded, and illegible. Through photography and digital image enhancement, we were able to read eighteen yadegari, albeit incompletely. The surviving yadegari are mostly on the west side of the stucco inscription (fig. 12). As can be seen in the panoramic photographs, the stucco inscription on the east has been partially repaired and plastered during recent restoration, and it is possible that this section previously had more yadegari (fig. 13). In the future, perhaps more of these wall writings can be identified in other parts of the building and added to this collection.

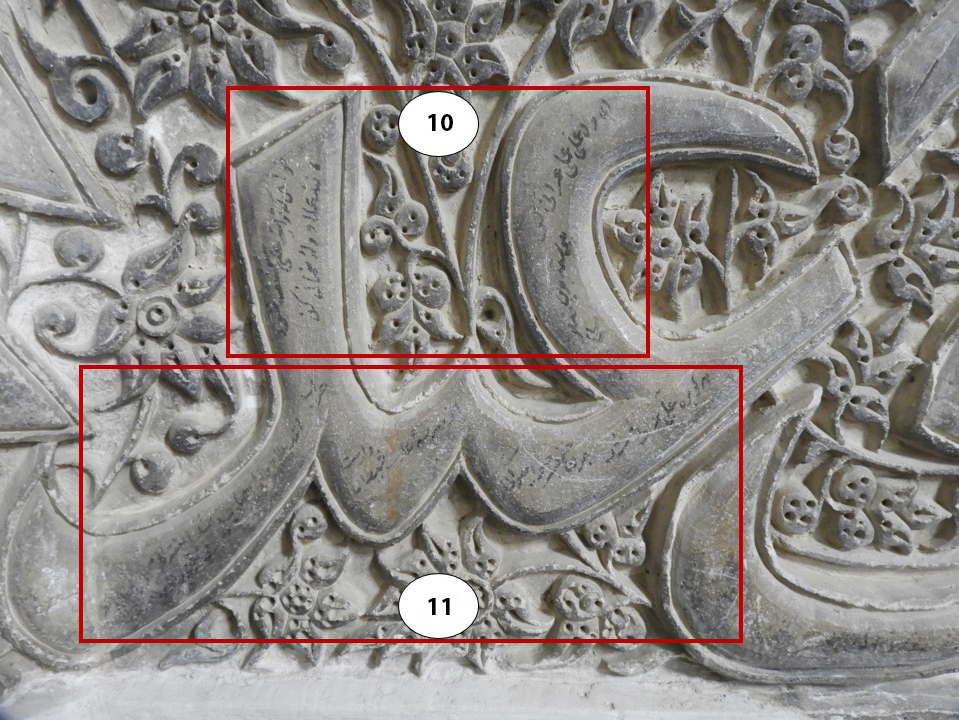

The yadegari contain interesting data. Sixteen verses from four different poets were identified in them: Abu Saʿid Abo’l-Khayr, an eleventh-century mystic; Saʿdi Shirazi, a thirteenth-century poet; Khaju-ye Kermani, a thirteenth-century poet; and Salman Savaji, a fourteenth-century poet.

The most prominent theme among these verses is the expression of Shiʿi beliefs (numbers 6, 8, 10, 11, 14). Both of the selected verses of Khaju-ye Kermani (d. 1334) and Saʿdi (d. 1291) are on this subject (numbers 6, 10). The theme of Khaju’s selected poem, which is advisory in nature, invites the reader to follow the way of ʿAli ibn Abi Talib, the first Shiʿi Emam, in life. A small but interesting point about these verses is that they also mention a famous fourteenth-century poet and mystic: ʿAlaoddowleh Semnani (d. 1336), who was one of Khaju’s teachers and patrons. In this poem, he is an example of those who have chosen ʿAli’s path in life. The choice of such a verse also shows ʿAlaoddowleh’s fame and credibility among the people of the time. The date of the yadegari is illegible, but based on comparison with the writing style of other dated inscriptions in the building, it probably belongs to the sixteenth century.

As mentioned, some of the inscriptions in the Emamzadeh Yahya are dated. These dates have often been eroded, but seven dates were readable (numbers 3, 4, 8, 14, 15, 16, 18). The oldest date is 750/1349 (number 3), which is only 43 years after the date of the stucco inscription. In chronological order, the rest of the dates are: 985/1577, 997/1589, 998/1590, 1332/1913, 1349/1930, and 1345 Sh/1966. The three close dates during the tenth/sixteenth century, which coincide with the Safavid era [1501–1722], may indicate a period of renewed prosperity for the tomb and an increase in visitors and pilgrims (زائران). Interestingly, in the inscription dated 985/1577 (number 8), the only remaining verse—“May [God] grant eternal fortune and everlasting life”—is from one of Salman Savaji’s odes that was actually composed in praise of and prayer for the king of the time. Could this inscription be a prayer for the Shiʿi Safavid king (this period coincides with the reign of Shah Mohammad Khodabandeh [r. 1576–77])? It should also be noted that around the same time, in Moharram 971/September 1563, a new wooden door was made and endowed to the tomb (see History of Evolution and cat. no. 15). This point also confirms the prosperity of the building in the second half of the sixteenth century.

Traces of four or five contemporary yadegari were also found in the building. The yadegari dated 10 Moharram 1332/9 December 1913 (number 14) shows that at the end of the Qajar period, the building was still active and people were visiting it for pilgrimage and possibly for ceremonies on the day of Ashura. Unlike the older yadegari in the tomb, which are written in ink, this one is in pencil.

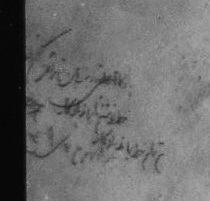

We end this brief summary with an interesting yadegari: number 16. This example is evidence of the short lifespan of most wall writings. In an old photograph of the interior of the Emamzadeh Yahya taken by André Godard around 1930, a yadegari is inadvertently recorded on the edge of the image (fig. 14). Today, there is no trace of this writing in the building.

Although the yadegari is dated, only half of the date (year 49...) is visible in the frame. The location of the yadegari and style of writing both clearly indicate that it is not an old yadegari. The writing is located in the plastered dado in the southwest corner of the tomb. Until the late nineteenth century, this area was covered with luster tilework (کاشیهای زرینفام, kashi-ha-ye zarrinfam). After these tiles were stolen, the dado was covered with white plaster, and the yadegari was written on this plaster. The complete date should therefore be 1349/1930, which is close to the date the photograph was taken. The yadegari shows that the building was still in use by people at the time of Godard’s visit. Moreover, the fact that it has faded in less than a hundred years suggests that there were probably other inscriptions in various parts of the tomb that have disappeared today. Only one part of the yadegari’s text is legible, the famous verse:

خط نوشتم تا بماند یادگار / من نمانم خط بماند روزگار

I wrote this so that it endures as a yadegari / I won’t be around, but my words will remain

List of Yadegari in the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin

Here, I categorize the recorded yadegari into the four groups mentioned above. With the exception of yadegari number 16 (André Godard, ca. 1930) and 17 and 18 (Hamid Abhari, 2024), I photographed all of the yadegari during my two visits to the site in Farvardin and Shahrivar 1401/April and September 2022. At the end of each yadegari, there is an audio recording allowing you to listen to the text.

[the translation follows the style of the original transcription]

First Category: Seeking Prayers

1

O you whose fortune is blessed / Do you know what I intended from you

[Read] a Fatiha for the writer / So that your end may be praiseworthy

The poor, the humble, the needy

...

In the year

...

I wrote this so that it endures as a yadegari.

I won’t be around, but my words will remain.

ای آنکه تو [را طالع] مسعود بود / دانی که مرا از تو چه مقصود بود

یک فاتحه از بهر نویسنده [بخوان] / تا عاقبت کار تو محمود بود

الفقیر الحقیر المحتاج

...

فی سنه

...

این نوشتم تا بماند یادگار

من نمانم خط بماند روزگار

Listen to a recitation of the yadegari.

2

He is the Exalted

Anyone who enters this garden sincerely / His prayers will certainly be answered.

هو العلی

هرکه درین روضه دراید ز صدق / هست دعایش به یقین مستجاب

Note: This was probably a famous couplet among people, as we see it in other places. One example is on the wood zarih [grilled screen around the cenotaph] of Emamzadeh Soltan Sayyed Ahmad, son of Emam Musa al-Kazem in Faryumad, Khorasan [map].

Listen to a recitation of the yadegari.

3

I arrived at this fortunate spot of (?) / I wrote in this way (?) without a notebook.

If one day a chivalrous person reads [this] / He will ... from the sincerity of his heart

....

Written by the servant

Ahmad son of ... Varamini (?)

... date ...

Fifty and seven hundred [750/1349–50]

رسیدم من بدین فرخنده منظر(؟) / نوشتم این چنین(؟) بی هیچ دفتر

اگر روزی جوانمردی بخواند / کند از صدق دل بر ...

....

حرر العبد

احمد بن ... ورامینی(؟)

... تاریخ ...

خمسین و سبعمائه

Note: Yadegari 2 and 3 are written side by side in the same handwriting and are most likely by the same writer. In the date phrase, the first word is very faint. There is a possibility that this word might be ‘thirty’ instead of ‘fifty,’ meaning the inscription could be even older, dated 730/1329–30.

See Figure 16.

Listen to a recitation of the yadegari.

4

... and for all

The believing men and women

By Your Mercy, O Most Merciful of the Merciful

... in the month of Shawwal, year 997 [1588–89]

Written by ʿAla al-Molk/al-Kottab (?)

[It was written] ...

... ولجمیع

المومنین و المومنات

برحمتک یا ارحم الراحمین

... در شهر شوال سنه ۹۹۷

بخط علا الملک/الکُتاب (؟)

[تحریر] شد ...

Listen to a recitation of the yadegari.

5

God, by the sanctity of this son of a holy man ...

... and whoever erases (?) ...

الهی به حرمة این معصومزاده ...

... و هر کس که خط بزند(؟) ...

Listen to a recitation of the yadegari.

6

Lord, for the sake of the children of Fatemeh, / May I end my words with faith

Whether you accept or reject my call / My hand [grasps] the skirt of the Prophet’s progeny.

خدایا به حق بنی فاطمه / که بر قولم ایمان کنم خاتمه

اگر دعوتم رد کنی ور قبول / من و دست و دامن آل رسول

Listen to a recitation of the yadegari.

7

O God, by Your glory, do not humiliate me / [Do not shame me] with the disgrace of sin.

الاهی بعزّت که خوارم مکن / [به ذلّ] گنه [شرمسارم مکن]

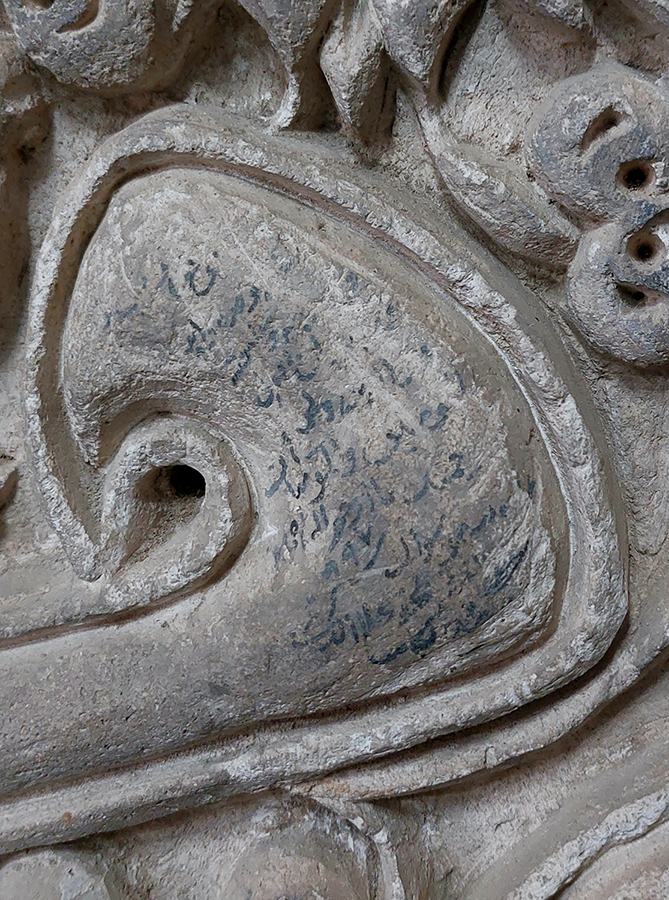

Note: Both yadegari 6 and 7 are from Saʿdi’s (d. 1291) Bustan. The first is from the second part of the chapter “In Supplication to God,” and the second is from “Chapter Ten: In Supplication and Conclusion of the Book.” There is another yadegari on the crown [of the letter] that was not read.

See Figure 19.

Listen to a recitation of the yadegari.

8

… Haydar … / lead me to perpetual [fortune] and eternal life.

... Sayyed (?) ʿAli ...

Year 985 (?) [1577–78]

... حیدر ... / [به دولت] ابد و عمر جاودان برسان

... سید(؟) علی ...

سنه ۹۸۵ (؟) [۱۵۷۷- ۷۸]

Note: This single line is from one of the odes of Salman Savaji (d. 1376), a poet from Saveh. He composed this ode in praise of Soltan Oveys Jalayer (r. 1365–75). The writing before this line has been erased, but the remaining letters do not match the previous part of this line in the original ode: “Raise your hand and say, O Lord, for that king.”

Listen to a recitation of the yadegari.

Second Category: Advice and Wisdom

9

The world is like a golden [jar] / sometimes the water in it is bitter, sometimes [it is] sweet.

Don’t be proud that [your life is so long] / [for the horse of one’s deeds is always under a saddle].

دنیا بمَثَل چو [کوزه] زرینست / گه آب بِدو تلخ و گهی شیرین [است]

تو غره مشو که [عمر من چندین است] / [کین اسب عمل مدام زیر زین است]

Note: This quatrain (رباعی) is attributed to Abu Saʿid Abu’l-Khayr (d. 1049).

Listen to a recitation of the yadegari.

10

O heart, do deeds like ʿAli ʿEmrani / [Be] a Muslim continuously in this way (?).

If you want the secret of ʿAli to be revealed to you / Act like ʿAlaoddowleh Semnani

... Shaʿban year six and seven ...

ای دل عملی علیِ عمرانی کن / پیوسته بدین نمط(؟) مسلمانی [کن]

خواهی که ترا سرّ علی کشف شود / مانند علاءالدوله سمنانی کن

... شعبان سنه سته و سبع...

Listen to a recitation of the yadegari.

11

Response

He who takes the path of ʿAli ʿEmrani / Like Khezr he goes to the water of life.

He escapes the habitual temptations of Satan / He becomes like ʿAlaoddowleh Semnani.

The poor, humble Mohammad (?)

جواب

هرکو به ره علیِ عمرانی شد / چون خضر به سرچشمه حیوانی شد

از وسوسه عادت شیطان وارست / مانند علا الدوله سمنانی شد

الفقیر الحقیر محمد(؟)

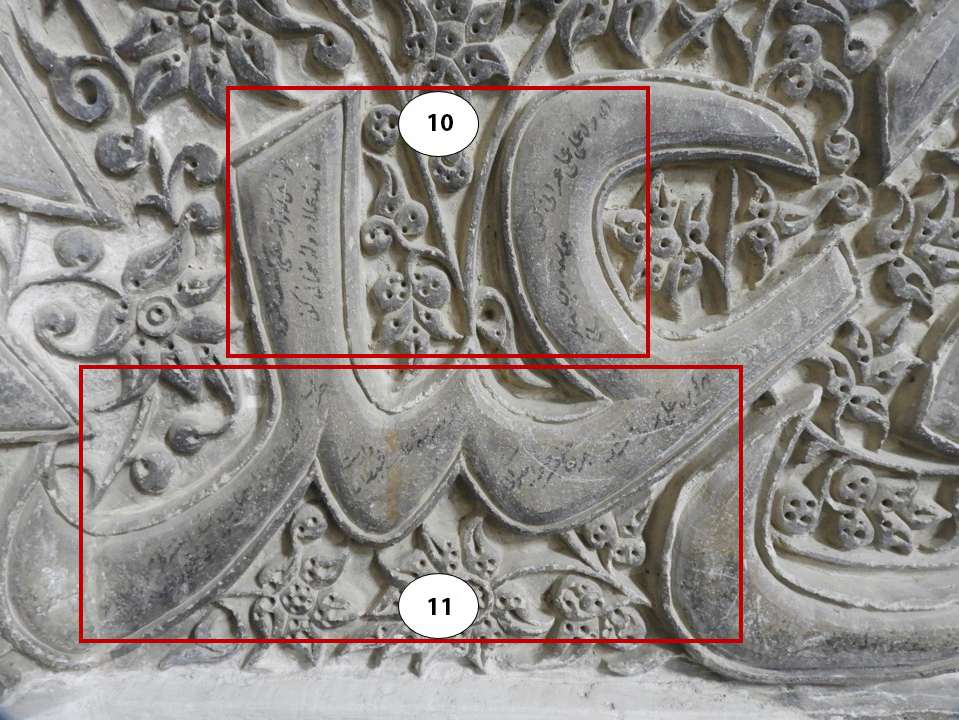

Note: Yadegari 10 and 11 are written one below the other but are by two different writers. As stated, yadegari 11 is in response to yadegari 10. Interestingly, the verses in 11 are attributed to Khaju-ye Kermani (d. 1290), but the verses in 10, although similar in theme, seem to be by an unknown poet, possibly the writer himself.

The reference to ʿAlaoddowleh Semnani (d. 1336) in both poems probably alludes to his spiritual transformation. In his youth, ʿAlaoddowleh served in the court of Arghun Khan [r. 1284–91], but due to a spiritual revelation, he left the court and spent the rest of his life in worship and self-purification.

See Figure 22.

Listen to a recitation of the yadegari.

Third Category: Complaints about Life

12

My two eyes are constantly weeping in separation from you. / There are hidden brands on my heart from sorrow for you.

The sinner ...

دو دیدهام ز فراقت مدام گریانست / مرا بدل ز غمت داغها پنهانست

المذنب ...

Listen to a recitation of the yadegari.

13

I wrote this so that it endures as a yadegari / I won’t be around, but my words will remain

Written by the sinful servant Shamsoddin ʿArizi (?) ...

Nezam (?) ... Lavasani (?)

این نوشتم تا بماند یادگار / من نمانم خط بماند روزگار

حرر العبد الخاطی شمسالدین عریضی(؟) را...

نظام(؟) ... لواسانی(؟)

Listen to a recitation of the yadegari.

Fourth Category: Describing Events

14

Yadegari of Mirza ʿAli Moradi (?)

Morning of the day of Ashura

From the direction of ... Varamin

We were honored in this pure shrine

...

God willing

May it be granted

...

On the 10th of the sacred month of Moharram 1332 [9 December 1913]

Mirza ʿAli

یادگاری میرزا علی مرادی (؟)

صبح یوم عاشورا

از جانب ... ... ورامین

مشرف شدیم در این مرقد مطهر

...

انشالله

نصیب گردد

...

در تاریخ ۱۰ شهر محرم الحرام ۱۳۳۲

میرزاعلی

Listen to a recitation of the yadegari.

16

May a yadegari … remain (?) …

I wrote this so that it endures as a yadegari.

I won’t be around, but my words will remain.

... month ... year [13]49

یادگاری ... ماند نظر کنم (؟) ...

خط نوشتم تا بماند یادگار

من نمانم خط بماند روزگار

... شهر ... سنه ۴۹[۱۳]

Note: As mentioned earlier, this yadegari, which was written just below the stucco inscription in the dado in the southwest corner of the tomb, has now disappeared. Its image can only be seen in a photograph taken by André Godard around 1930 (see fig. 14).

17

Oh ʿAli, help

Yadegari of Hajji ...

یا علی مدد

یادگار. حاجی ...

Note: Two more recent yadegari in pencil can also be seen on the stucco inscription and seem to have been written on the same day and in the same handwriting, merely to record the name and memory of the writer. One of the yadegari begins with the phrase “O ʿAli, help,” which is one of the most common prayers of dervishes and, of course, a Shiʿi phrase.

Citation: Nazanin Shahidi Marnani, “If some day a noble soul reads this... Documenting the yadegari of the Tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin,” translated by Farshad Sonboldel. Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.

Notes

Editor’s note: I (KO) have modified aspects of this literal translation to improve clarity and smoothness in English. Additional glosses appear in [ ], dates of poets are repeated to contextualize the time of writing, and some additional resources have been added at the end. Links to Iranarchpedia.ir (a standard architectural resource/encyclopedia in Iran) have been changed to equivalents in Archnet, since the former website is often inaccessible outside of Iran. We sincerely thank Sunil Sharma for translating the verses in the yadegari (some modifications have been made by Sonboldel). The author frequently links Ganjoor.net, the most useful website for reading and searching Persian poetry.

Acknowledgments: The trip to Varamin and photographing the yadegari was made possible with the companionship of my husband, Amir-Hossein Karimy. His collaboration in reading several yadegari was also a great help, for which I am grateful. I also thank Hamid Abhari for providing photographs he took of the building in 1400 Sh/2021 and 1402 Sh/2024. But most of all, I am grateful to Dr. Keelan Overton, who suggested this work and, after writing, patiently read the text several times and pointed out valuable points for its improvement. Also, with her keen eye, she found Godard’s photograph of the yadegari from the tomb and made it available for me to study.

- O’Kane, “The Appearance of Persian,” 33. ↩

- Masjedi, Khati ze deltangi, 95–96. ↩

- On the yadegari of this building, see my 1395 Sh/2017 essay. ↩

Bibliography

- ابوالخیر، ابوسعید. رباعیات نقلشده. وبگاه گنجور ، https://ganjoor.net/abusaeed

- افشین وفایی، محمد. «سلمان ساوجی». دانشنامه جهان اسلام. ج.۲۴، ۱۳۹۶. [Noormags]

- امیری خراسانی، احمد. «سیمای امام علی در شعر خواجوی کرمانی». وبگاه کتابخانه دیجیتالی تبیان،۱۳۸۷، https://library.tebyan.net/fa/Viewer/Text/63849/0

- انوری، حسن. «سعدی». دانشنامه جهان اسلام. ج.۲۳، ۱۳۹۶. [Noormags]

- دادبه، اصغر. «خواجوی کرمانی». دایرة المعارف بزرگ اسلامی، ۱۳۹۸، https://www.cgie.org.ir/fa/article/245033/خواجوی-کرمانی

- ساوجی، سلمان. دیوان اشعار. وبگاه گنجور، https://ganjoor.net/salman/divanss

- سعدی، مصلحالدین. بوستان. وبگاه گنجور، https://ganjoor.net/saadi/boostan

- شهیدی مارنانی، نازنین. «در یادگارنویسی -۲». وبگاه آسمانه، ۱۳۹۵، https://asmaneh.com/posts/vpxje

- مایل هروی. نجیب. «ابوسعید ابوالخیر». دایرة المعارف بزرگ اسلامی، ۱۳۹۹، https://www.cgie.org.ir/fa/article/226623/%D8%A7%D8%A8%D9%88%D8%B3%D8%B9%DB%8C%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D8%A8%D9%88%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AE%DB%8C%D8%B1

- مسجدی، حسین. خطی ز دلتنگی: یادگاریهای دیوارنبشت اصفهان. اصفهان: سازمان فرهنگی تفریحی شهرداری اصفهان، ۱۳۹۵. [Masjedi, Khati ze deltangi, A Line of Melancholy: Wall Inscriptions of Isfahan, 2016] [WorldCat]

- یاقوتیان، مهدی. وبگاه خطه فریومد، ۱۳۹۹، http://faryoumad.blogfa.com/post/611

- O’Kane, Bernard. The Appearance of Persian on Islamic Art. New York: Persian Heritage Foundation, 2009.

- Shahidi M. Nazanin. “Graffiti as a Historical Source for Architectural History: The 19th Century Graffiti of Chahar-Bagh Madrasa of Isfahan.” Paper presented at the Ernst Herzfeld Society Thirteenth Colloquium, July 6–9, 2017.

Additional Resources

For Encyclopaedia Iranica articles in English on some of the poets mentioned here, see:

We recommend some of the following translations:

- Khaju-ye Kerman: Homay e Homayun (in Italian)

- Saʿdi: Golestan, various