From Varamin to Honolulu: The Displacement, Commodification, and Aestheticization of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s Luster Mihrab, 1863–2025

Keelan Overton and Hossein Nakhaei

Contents:

Introduction

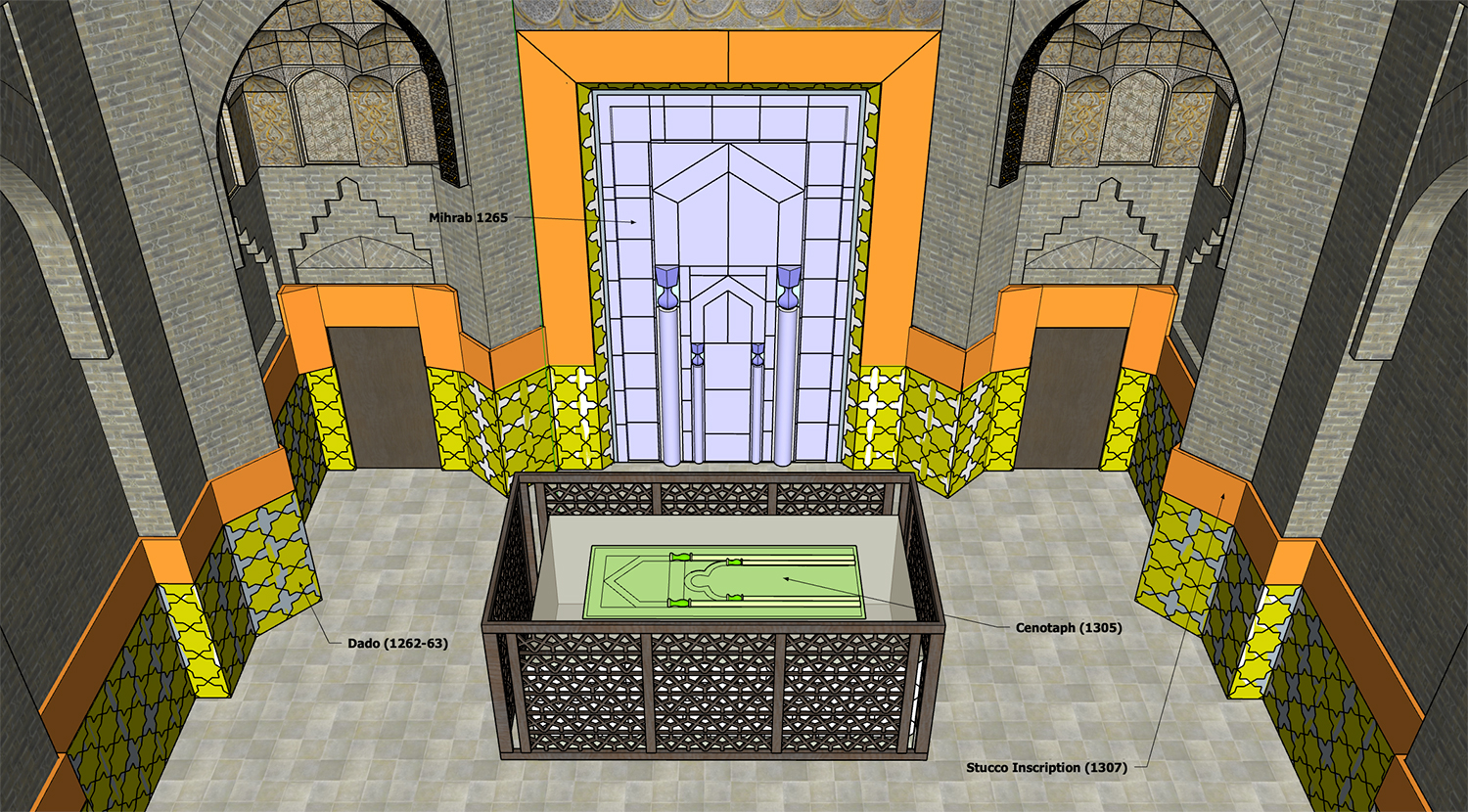

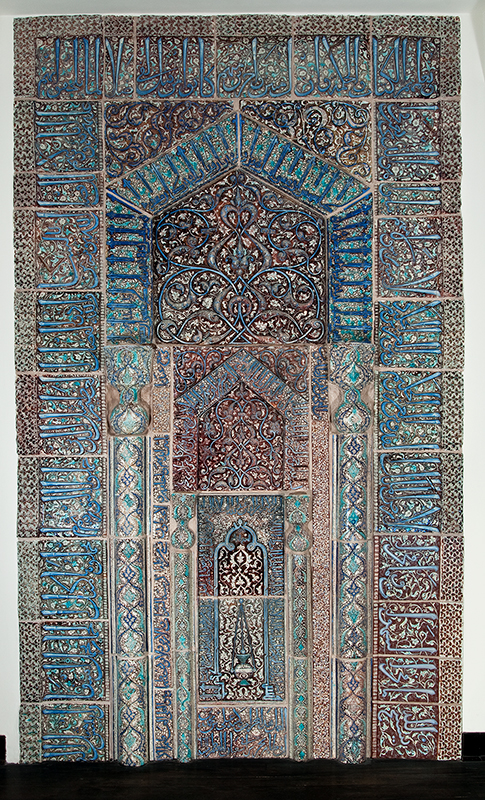

For over six hundred years, a luster mihrab dated Shaʿban 663/May 1265 was one of the most prominent architectural, sacred, and ritual features in the relatively small octagonal tomb chamber of Yahya b. ʿAli (d. 255–56/869–79) (vid. 1). Measuring over twelve feet tall and seven feet wide, it occupied almost the entire width of the narrow qibla wall and was carefully framed by three sets of borders: a thin stucco frieze, a border of alternating luster half star and cross tiles, and a stucco epigraphic band carrying the opening verses of sura al-Jumuʿah (Qur’an 62), which are also present in the mihrab’s outer border (fig. 1). The mihrab’s primary function, as with any mihrab, was to direct prayer toward the Kaʿba in Mecca.

Video 1. Interior of the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya, Varamin, looking toward the mihrab void on the southern qibla wall and then panning over the zarih (screen enclosing the cenotaph) and ending at the entrance door on the north. Video by Hamid Abhari, October 2024.

Standing in grandeur before its visitors, the mihrab drew some to engage with its twelve sets of relatively legible Qur’anic inscriptions and dazzled the eye as light animated its lustered surface. Together, these qualities endowed it with a powerful presence during ziyarat (pious visitation) to the tomb, extending far beyond its strictly orienting function (vid. 2). Within the intimate space, it likely contributed to the pilgrim’s embodied spiritual experience, animating various senses and encouraging a heightened awareness of the Divine. Situated just a few feet from the cenotaph, which symbolized Yahya b. ʿAli’s presence and served as the material conduit for the pilgrim’s wishes and calls for intercession, the mihrab played a central role in shaping the devotional encounter.

Video 2. Panning up the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab, from the bottom to the top. Video by Aiden Khazeni, September 2023.

The mihrab was likely among the last elements stolen from the shrine. While the cenotaph and dado were renewed with later substitutes, the mihrab was beyond replacement, its absence itself—its literal void—becoming a powerful presence within the tomb and space for reflection (figs. 2–3). While an irreparable loss to the Emamzadeh Yahya, the systematic removal of the tomb’s luster tilework did not diminish the shrine’s significance, and it continued to be the focus of ziyarat during the twentieth century, as documented in yadegari (inscriptions written on the walls by pilgrims), photographs, and living memories. Today, the shrine remains a vibrant site of social and religious community, resisting any diminishment or supposed victimization.

Composed of over sixty tiles, the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab is one of only eleven currently known mihrabs from medieval Iran produced in the luster technique, one of most complex, laborious, and costly ceramic techniques of the day.1 Compared to some of the other fragmented or entirely dismantled mihrabs, the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab is in relatively better condition, at least in terms of preserving its integrity. This does not, however, diminish areas of loss, damage, and dislocation stemming from its forced transfer and subsequent circulations.

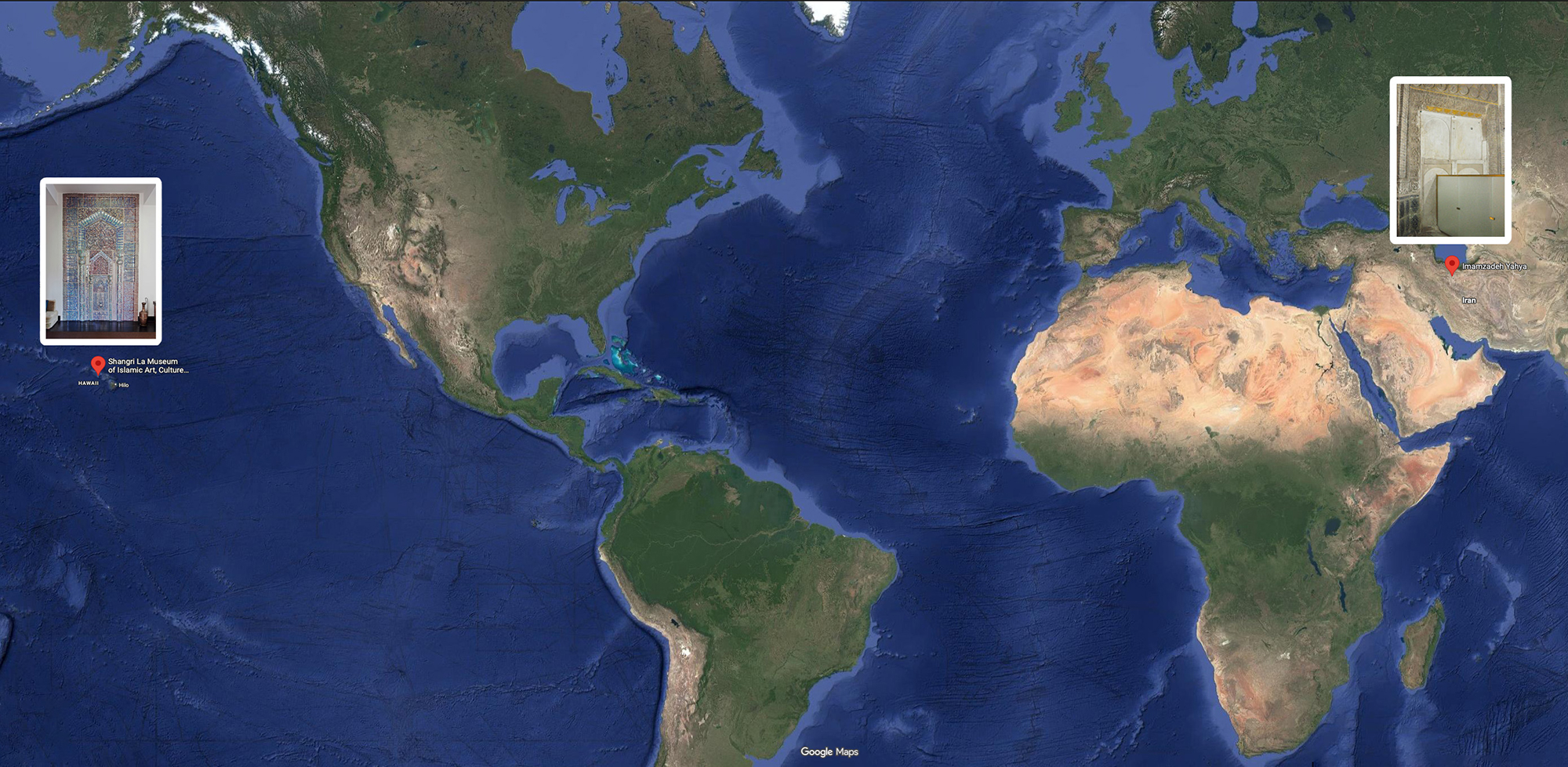

The Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab is in many ways a microcosm of the Emamzadeh Yahya complex as a whole: it has a long and complex history and has suffered some irreparable damage but remains an invaluable ‘site’ of Persian art, architecture, culture, and religion (terms that inevitably intertwine). Like the shrine, the mihrab’s history is ideally considered through a diachronic lens that combines its original periods of production and subsequent layers, uses, and resonances across audiences. In this study, we adopt a historiographical frame and seek to answer a series of fundamental questions: How did the mihrab end up literally on the other side of the world, in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, in the Hawaiian home of American billionaire heiress Doris Duke (d. 1993) (fig. 4)? How did it become known to some audiences as an isolated ‘masterpiece,’ ‘monument,’ or ‘object’ defined primarily by art historical data, as in the caption accompanying figure 5? And, perhaps most importantly, what are the implications of these framings?

In this historiography spanning over 160 years, we trace the mihrab’s documentation in situ, its physical displacement and alteration, commodification on the international art market, popular and academic reception, and trajectories across five foreign destinations: Paris, London, Philadelphia, New York, and Honolulu. Our goal is to improve the understanding of this iconic ensemble and to tell its recent history in a comprehensive and detailed manner, presenting a repository of facts and resources that can be used for subsequent research and interpretation. We share all currently known information while acknowledging that additional material will hopefully—and surely—come to light.

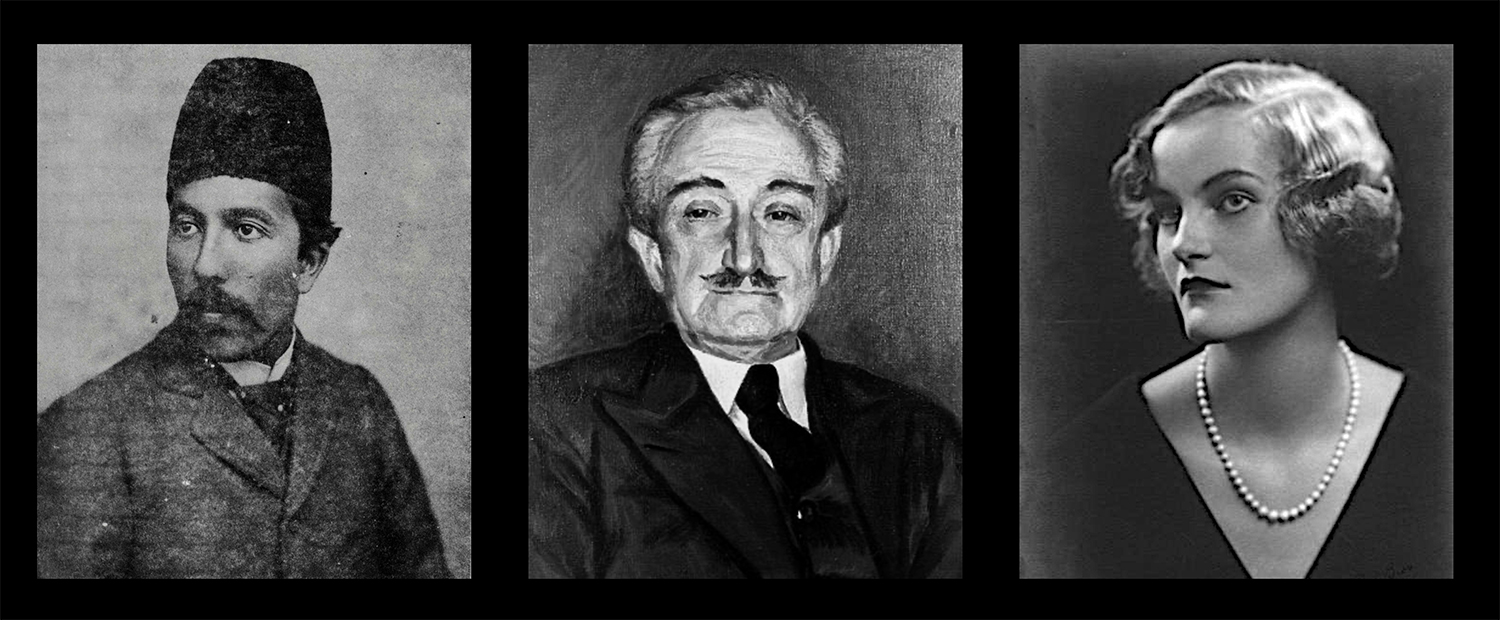

This story unfolds in three main chapters, each of which is marked by the interests, privilege, and wealth of three personalities: the Iranian dignitary Mirza Hasan Khan Ashtiani Mostowfi al-Mamalek (d. 1932), the Armenian dealer Hagop Kevorkian (d. 1962), and the American collector Doris Duke (d. 1993) (fig. 6).

Chapter One (Displacement): 1863–1912 explores the mihrab’s documentation in Iran by Qajar officials and European visitors, its transport to Paris in 1900 by Mirza Hasan Khan Ashtiani Mostowfi al-Mamalek, and the related European art market for luster tiles.

Chapter Two (Commodification): 1912–35 considers Hagop Kevorkian’s purchase of the mihrab from Mostowfi al-Mamalek in 1912–13 and the dealer’s purveying, commodification, and display of the ensemble in international events and cities, including in the United States.

Chapter Three (Aestheticization): 1937–2025 traces Doris Duke’s purchase of the mihrab from Hagop Kevorkian in 1940, the ensemble’s history in her private Hawaiian home, and its popular and scholarly reception since 2002, when Shangri La opened as a public museum.

Note to the Reader

In order to facilitate digestion across audiences and interests, this layered history is presented in two formats: an essay and a visual timeline. This lengthy essay consists of an introduction (this page), three chapters, and a conclusion and bibliography. The visual timeline synthesizes the story through representative images and short texts. Clicking on any image leads into the essay.

This historiography is framed as a strict chronological history and generally presents events in the year of occurrence in the present tense. In some cases, a visit to the Emamzadeh Yahya falls in one year, while the published or recorded account appears much later. Factors such as the timing between the visit and publication, as well as the type of publication (print or digital, small or large print run, affordable or costly, accessible or exclusive), naturally affected how the mihrab was seen and understood or, alternatively, ignored and misunderstood.

While this study focuses on the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab, its fates and fortunes are often inseparable from the other luster tiles steadily stolen from the tomb during the second half of the nineteenth century, including portions of the luster cenotaph attributed to Yahya b. ʿAli and stars and crosses presumed to have clad the dado.2 In addition to referencing these tiles, we also highlight some seminal events in the broader historiography of Persian art and architecture.

Throughout this historiography, we have paid particular attention to usage and coinage. Single quotes (also known as ‘scare quotes’) are used to signal terms that are problematic, subtle, and/or products of their time. Double quotes are used when quoting someone else’s words or phrases. The words used to describe the removal of the luster tiles from the Emamzadeh Yahya can be particularly loaded. In our own usage, we have avoided the terms ‘plunder’ and ‘looting,’ because they are often associated with imperialist military incursions and their associated loot. The case of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s luster tiles is a much different story from, say, the Benin Bronzes.

The removal of tiles from the Emamzadeh Yahya occurred over several decades and involved a variety of actors for different actions: the original instigation, the tiles’ physical separation from walls and surfaces (alternate terms: theft, vandalism, deinstallation, denuding, stripping, stealing), their packing and storage within Iran, and their transport out of the country. Regardless of the nationalities of the individuals involved, the specific legal frameworks in place, and whether financial transactions with local parties can be documented, the evidence presented here reveals that the mihrab’s taking from the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya was a wrongful extraction of a sacred element from a living tomb and was acknowledged in its day as duplicitous and problematic. This removal marks a major loss on two levels: to the Emamzadeh Yahya itself and to the cultural patrimony of Iran.

Acknowledgements

We thank all archivists, curators, and librarians who facilitated our research in person and from afar. We are especially grateful to Amir Mahdi Moslehi for sharing several important photographs in Iranian archives and alerting us to some key sources and Alex Pezzati for supporting and enhancing our research of the Penn Museum chapter of this story. Overton conducted research in the National Museum of Asian Art Archives in Washington, DC, National Archives and Diplomatic Archives in Paris, the V&A Museum Archives in London, and Duke University in Durham, NC. Nakhaei conducted research at the New York Public Library in New York City and the Penn Museum in Philadelphia. For the purposes of this historiographical research, the authors have not visited Shangri La in person but have instead focused on related archives preserved in Duke University. Nakhaei plans to conduct a firsthand examination of the mihrab for his dissertation, entitled “Luminous Past, Fragmented Present: Persian Luster Tiles from Sacred Architecture to Museum Galleries,” which is in progress at the University of Pittsburgh. Overton last saw the mihrab in person at Shangri La in 2012, when working there as a curator. Our last visits to the Emamzadeh Yahya were in 2018 (Overton) and 2020 (Nakhaei). Nakhaei’s archival research was supported by a Marstine Fellowship for Research and Public Engagement at the University of Pittsburgh. Overton’s work was supported by the Persian Heritage Foundation, Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art, Gingko, the Barakat Trust, and Clark Art Institute.

Notes

- The known luster mihrabs are in different states of preservation, and only five of the eleven can be described as relatively intact. Some, like the two made for the tomb of Emam Reza in Mashhad and now in the shrine’s museum (Checklist, no. 16), are missing a few tiles, present some tiles in jumbled order, and include some replacement parts in different media. Others, like the example made for the Emamzadeh ʿAli b. Jafar in Qom and now in the National Museum of Iran in Tehran, appears relatively intact in its current guise but is in fact heavily restored (for further discussion, jump ahead to 1931). ↩

- Most star and cross tiles that measure about 30 cm, contain Qur’anic inscriptions around their perimeter, are decorated with luster painting and white glaze, and dated between Dhu al-Hijja 660/October 1262 and Rabiʿ II 661/March 1263 can be confidently attributed to the Emamzadeh Yahya. The majority of such tiles are not dated, however. Photographs of the dado tiles in situ are not currently known, but some of their imprints remain. The half versions that framed the mihrab are documented in photographs and imprints, and the tip of one luster cross has been remounted under the latter. It is possible that some of these tiles could have clad the sides of the cenotaph (originally a large rectangular box) and/or been used in other areas of the complex, including the octagonal structure with a conical dome once on the west. Another outstanding question is whether or not similar tiles with Persian verses were used at the site. At present, we do not know of any other medieval sites in Varamin with such star and cross tiles, but similar tiles were used elsewhere, and tiles were easily mixed up in the hands of dealers and collectors. Throughout this study, we often describe these tiles as “from the Emamzadeh Yahya” while acknowledging some ambiguities. ↩

Citation: Keelan Overton and Hossein Nakhaei, “From Varamin to Honolulu: The Displacement, Commodification, and Aestheticization of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s Luster Mihrab, 1863–2025.” Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, November 16, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.