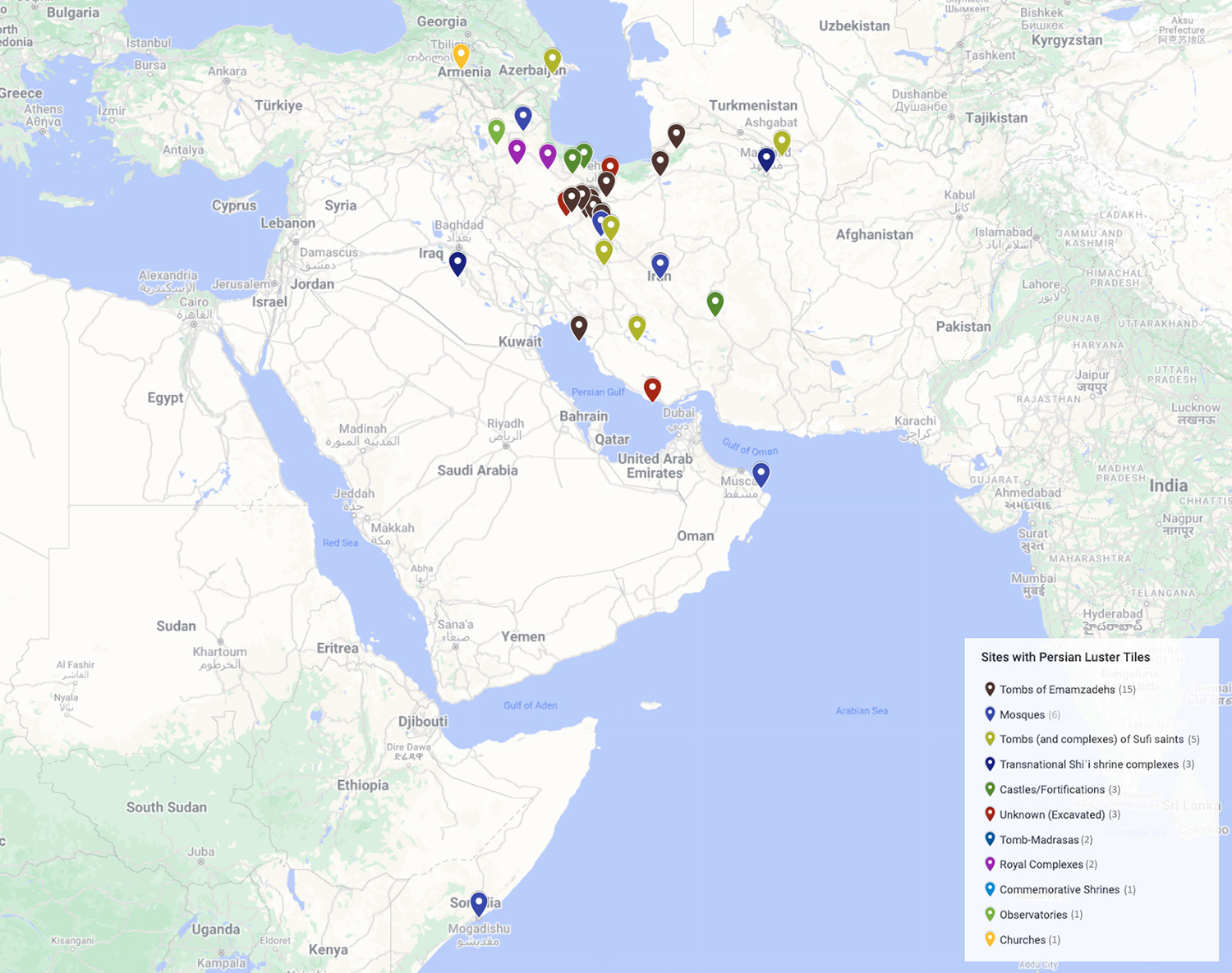

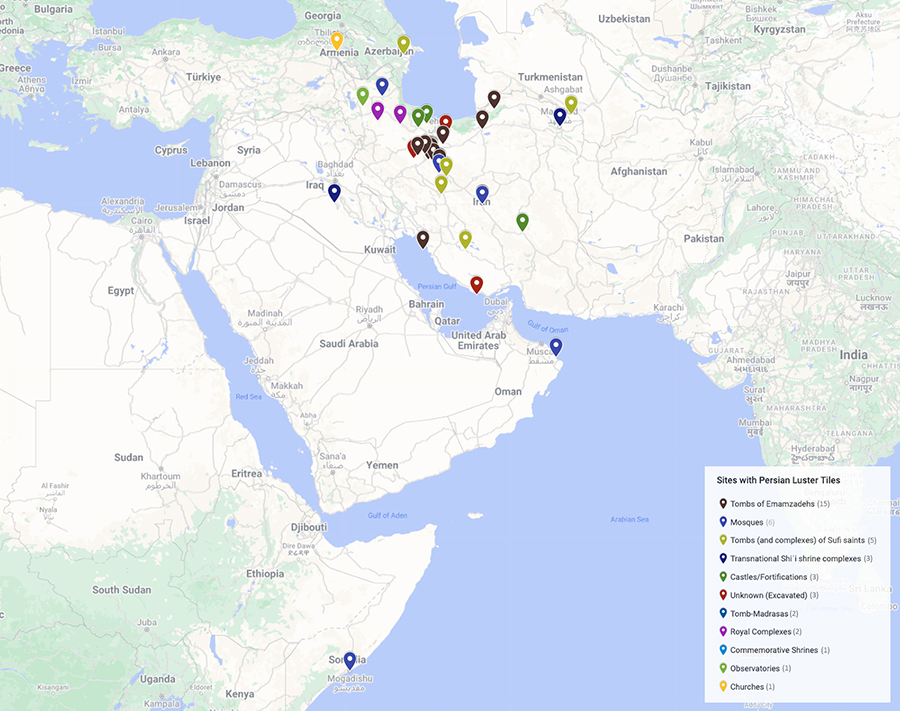

Sites with Persian Luster Tiles, ca. 1200–1350

Hossein Nakhaei and Keelan Overton

The tomb chamber of the Emamzadeh Yahya was an exceptional luster tiled interior of medieval Iran, but it was far from the only space decorated in this manner. In 1985, Oliver Watson published a list of twenty-two sites decorated with Persian luster tilework or associated with it in some way.1 This list can now be expanded to forty-two sites (fig. 1). In this essay, we provide an overview of these diverse sites, consider the degree to which their tilework (or evidence of it) remains, explore how some tiles are remembered at the sites themselves, and highlight steps taken by some museums to bridge the gap between displaced tiles and their original contexts. Sharing detailed information about some sites can be problematic, because they unfortunately remain at risk. We have modified this presentation accordingly.

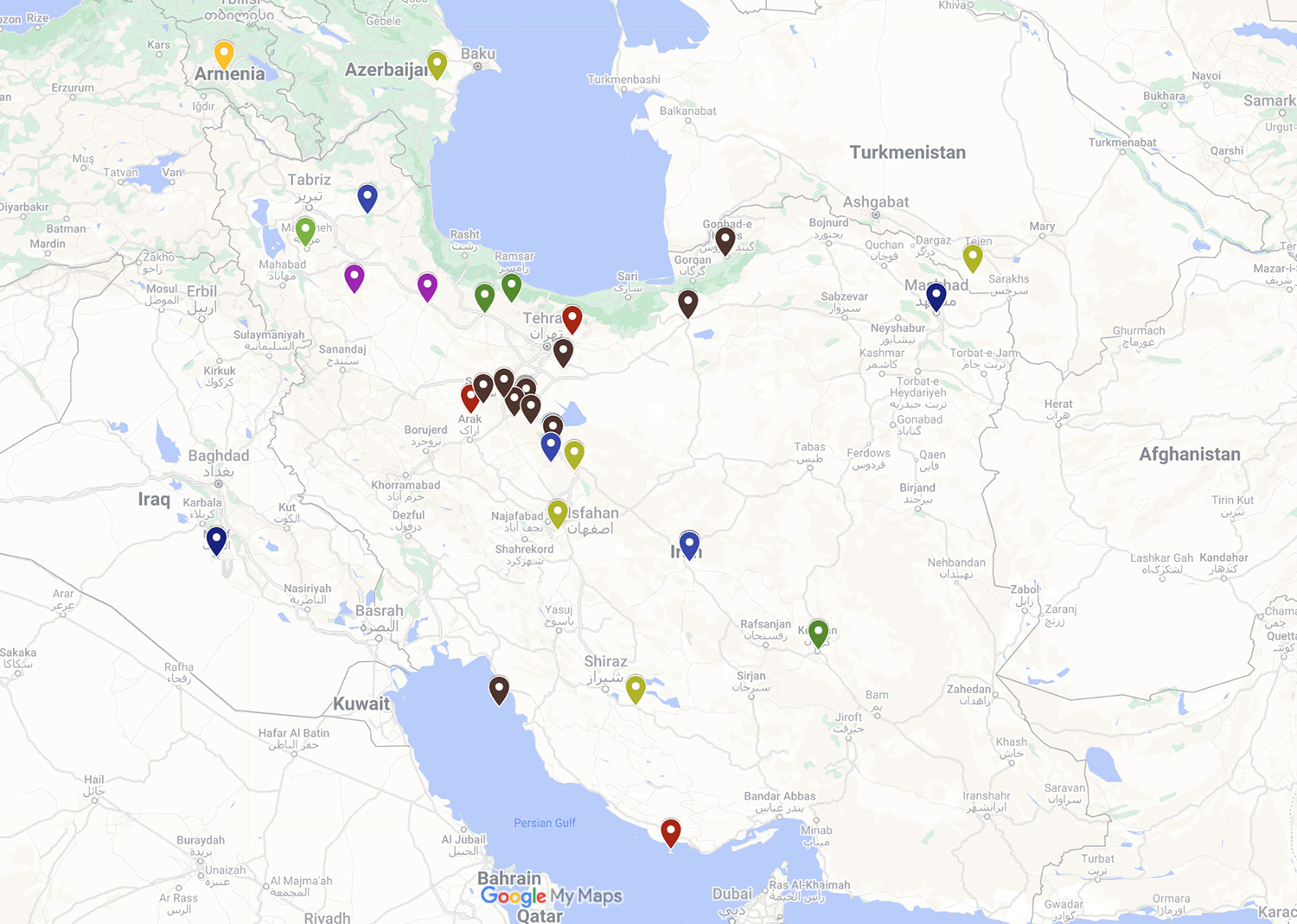

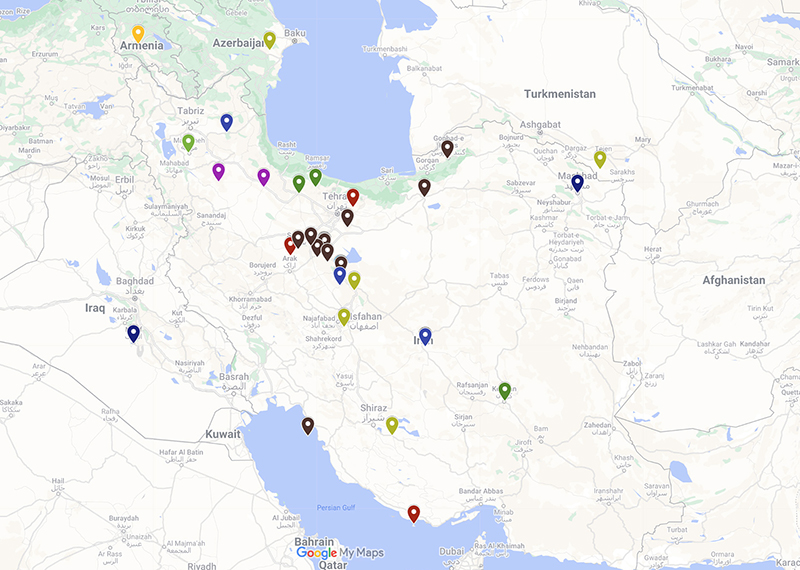

Thirty-six of the sites are in modern-day Iran and an additional four are in neighboring Armenia, Azerbaijan, Iraq, and Turkmenistan. Considered together, this group reflects the geographical expanse of the Ilkhanid khanate (1256–1353) and the Persianate world that preceded national borders (fig. 2). Two sites are farther afield along the coasts of Oman and Somalia (see fig. 1). Like Watson’s original list, this one is likely to expand as new findings come to light.

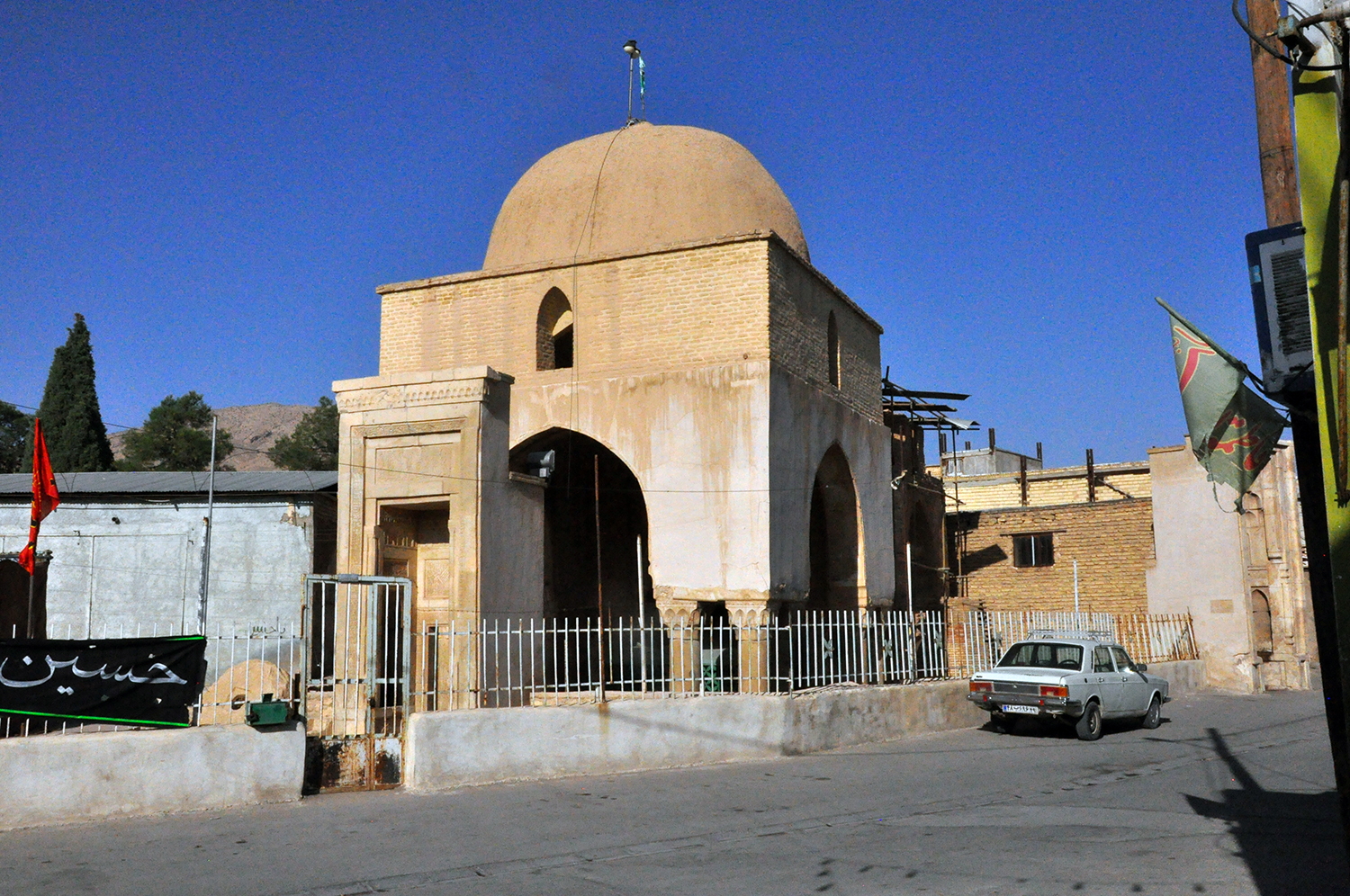

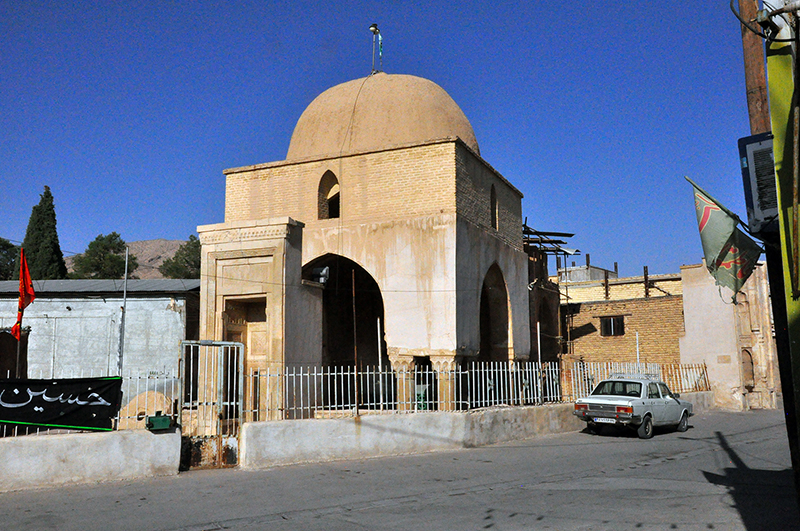

The sites can be divided into eleven building types, with the caveat that some move fluidly across typologies. Half of them (23 of 42) are funerary and can be further divided into three sub-categories: transnational shrines (sprawling complexes that entomb the Emams; fig. 3), emamzadehs (tombs of descendants of the Emams, ranging in size from single domed chambers to multi-unit complexes), and Sufi complexes (tombs of Sufi saints, also ranging in size; fig. 4). Most of these tombs remain in use; that is, they are active sites of pilgrimage (ziyarat). The remaining building types include mosques, castles or fortifications, royal complexes or palaces (fig. 5), tomb-madrasas, commemorative shrines (generally memorializing a holy figure’s presence or witnessing), observatories, churches, and archaeological sites whose functions remain unknown.

In addition to differing considerably in function, size, and condition, the forty-two sites vary in the degree to which they were originally decorated with luster tilework. Some sites included interiors that were the focus of holistic luster commissions with multiple architectural elements (dados, epigraphic friezes, mihrabs, cenotaphs, borders). Among the best-known luster tiled interiors are the tombs of Emamzadeh Yahya, Emam Reza (map), ʿAli b. Jaʿfar (map), and Shaykh ʿAbd al-Samad (map) (see Leone’s essay). Some large complexes had multiple spaces decorated with luster tilework. In the Shrine of Emam Reza, for example, the mosque next to the tomb of Emam Reza included a luster mihrab (figs. 6–7).2 In the Shrine of Shaykh ʿAbd al-Samad, the octagonal chamber of the complex also had a mihrab (discussed further below).3

Most of the luster tiles in question were made between circa 1200 and 1350, and some are dated to the exact month and/or year. In terms of production, the majority are presumed to have been made in Kashan, per several families of known Kashani potters (see Blair’s essay). In some cases, notably the palatial complex of Takht-e Soleyman in northwest Iran (map), both kilns and molds have been discovered, suggesting on site production (figs. 8–9).4 We must also leave open the possibility of other production sites, including beyond modern-day Iran.5

In Situ Tiles

Of the forty-two sites, only ten preserve luster tiles in situ or at least in their original spaces, with the number of tiles ranging from many to just a few. The tomb of Emam Reza in the Mashhad shrine (see figs. 6–7) has the largest number of tiles in situ and is the most well-known example. Most of the sites preserve only a few remaining tiles, as in tomb of Abu Saʿid in Miana, Turkmenistan (map) (fig. 10).6 In some cases, the current placement of the tiles reflects later interventions, restorations, and remountings, and we must therefore be cautious of presuming that in situ extends to original placement.7 In a few instances, as in the church of Yeghvard (Eghvard) in Yeghvard, Armenia (map), the luster tiles are examples of reuse from other sites.8

Two sites are also notable for preserving fragments of luster tiles. One is the tomb of ʿAbd al-Samad in Natanz, where several fragments embedded in the walls may help to identify other tiles from the site.9 The other is the shrine complex of the Sufi saint Bayazid in Bastam, Iran (map), where some small fragments of Ilkhanid tiles were carefully integrated into the building’s revetment.10 Unlike the Natanz tomb, which can be considered a cohesive luster interior, the Bastam case is an example of select quotation or recycling.11 As such, we do not include this site in our list of forty-two.

In Situ Imprints

Among the most useful tools for understanding a site’s lost tiles are the imprints left behind from their adhesion to the walls. These imprints can help scholars to reconstruct shape combinations and link some museumized tiles to their sites. Ideally, they also include fragments that confirm the techniques of the tiles in question, which included not only luster but also monochrome, lajvardina, and glazed/unglazed (buff). In the small tomb in the Natanz shrine, all of the tile imprints on the walls remain uncovered, as if the theft transpired yesterday, and fragments confirm a general pattern of luster stars alternating with monochrome turquoise crosses (see this 2018 video).12 At Takht-e Soleyman, imprints confirm a wide range of shapes and combinations, and tiles in many techniques can be appreciated in the site museum (figs. 11–12, vid. 1–2).13

Video 1. Imprints of tile revetment in the west eyvan of Takht-e Soleyman. The video begins facings the octagonal pavilion (see fig. 11) and then walks into the eyvan. Note that this video was taken on a windy day and is quite shaky. Video by Keelan Overton, 2016.

Video 2. Tiles in various shapes and techniques on view in the site museum of Takht-e Soleyman. Video by Keelan Overton, 2016.

In Situ Memories

At some sites, luster fragments have been remounted within their original settings as memory devices and responses to the loss. In the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya, a fragment of a tip of a luster cross was remounted at the top of the mihrab void, probably in the early 1980s during the tomb’s conservation (fig. 13) (see Photo Timeline, no. 44). This fragment is the only piece of luster still in the tomb and combined with the imprints above serves as an important reminder of the lost revetment.

An interesting case of remembrance also occurred recently (2022) in the tomb of Shaykh ʿAbd al-Samad in Natanz. Luster and turquoise fragments were remounted within a plaster substrate echoing the original star and cross dado and epigraphic frieze above. This layer was then placed over a portion of the dado (fig. 14). Although not entirely accurate (fragments from the mihrab of the adjacent octagonal dome chamber were included in the frieze), this installation can be interpreted as an artistic response to the violent act of fragmentation—the literal breaking of tiles—that occurred during the tomb’s plunder.

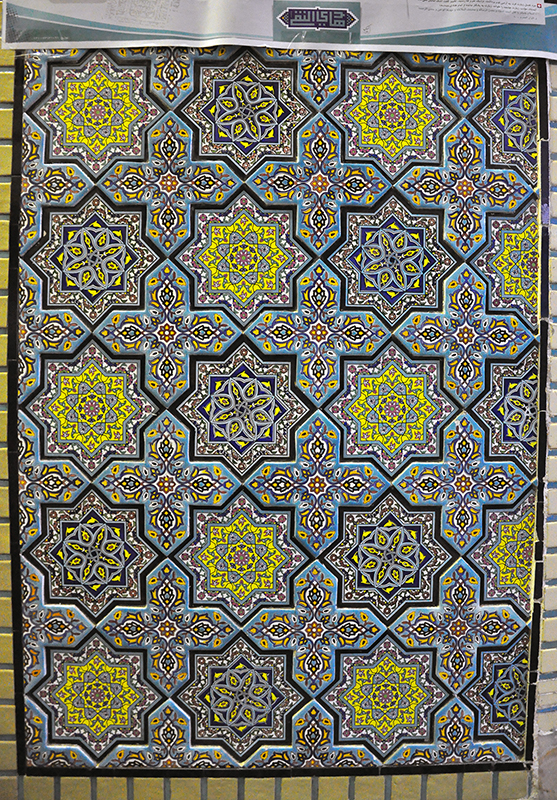

For sites that lack tiles, fragments, and imprints, the memory of lost tilework can be preserved through new decoration inspired by original patterns. These commemorative additions can include newly tiled dados, as in the Emamzadeh ʿAli b. Jaʿfar (map) (figs. 15–16). In this case, the site’s new carpets also reference its lost tilework (see fig. 15).14

A final mode of site-based remembrance is through didactics that mention or show the displaced tiles in museums worldwide. The mihrab void of the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya once displayed two collages combining prints from Jane Dieulafoy’s La Perse with photographs of the tomb’s cenotaph tombstone panel and dado tiles on display in the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg (figs. 17–18).15 In the octagonal domed chamber of the Shrine of Shaykh ʿAbd al-Samad, a large banner once displayed next to the mihrab void (a now dispersed luster mihrab) indicated that its tiles were stolen (به سرقت [رفته]) during the Qajar period and now kept in the Louvre (they are in fact in many museums) (fig. 19).16 Both of these didactics have since been removed, underscoring how acts of site-based remembrance are often in flux. A third example can be found in the shrine complex of Pir Hosayn (map) in Prisatçay village, Azerbaijan, where photographs of the site’s luster frieze tiles are displayed in the entrance of the mosque (fig. 21) (see also this high-resolution video tour of the site).

In Museums

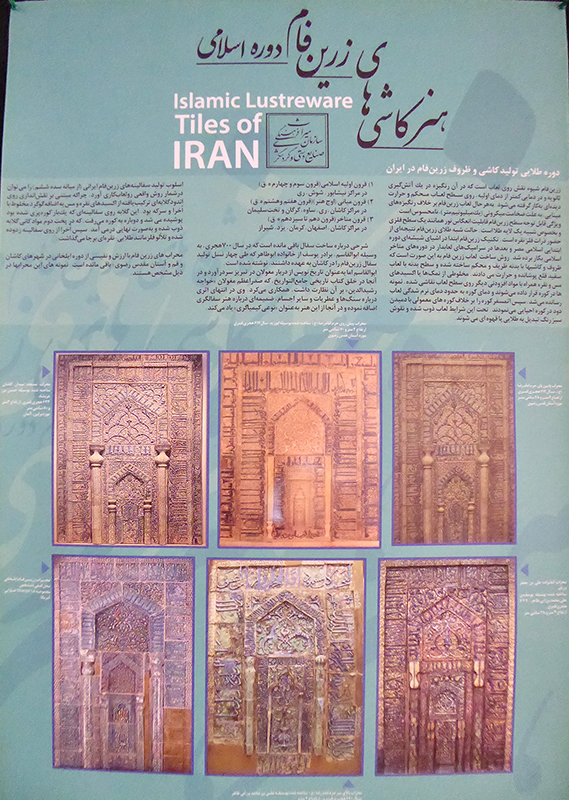

Today, most luster tiles are found in museums. In Iran, at least 28 institutions preserve this revetment, including site museums (fig. 21; see fig. 9, vid. 2), shrine museums (cat. no. 16), national and regional museums, and local repositories of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage. Luster tiles are also staples of Islamic art and ceramics galleries worldwide, and tiles from single sites can be broadly dispersed. In the case of the Emamzadeh Yahya, we currently know of around fifty private and public collections preserving its attributed or confirmed tiles (cat. nos. 17, 18, 19).

Museumized tiles exist in three main states. The first are broken fragments of single tiles in various shapes (stars, crosses, rectangles, octagons, hexagons) (see fig. 21). Their breakage could have transpired during damages to the standing building, burial in what would become an archaeological site, removal from standing walls during theft, and/or transport and travel. Many cross tiles have lost a tip, perhaps indicative of the pressure applied to lift it off the wall (fig. 22). As we have seen, the only luster fragment remaining in the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya is one such fragment (see fig. 13).

The second category are tiles that remain complete shapes; that is, they are not broken. These tiles are often displayed as stand-alone beautiful ‘objects,’ when they were in fact parts of much larger ensembles. In some cases, the desire to frame (and ultimately sell) a complete shape led to disparate parts being assembled together (Checklist, no. 17). The third and final category is the rarest: relatively complete multi-tiled ensembles. The mihrabs of the tomb of Emam Reza, Emamzadeh Yahya, and Mir Emad mosque in Kashan (map) are among the finest luster ensembles, but there are also missing parts (see Checklist, no. 16 and Travels of a Mihrab).17

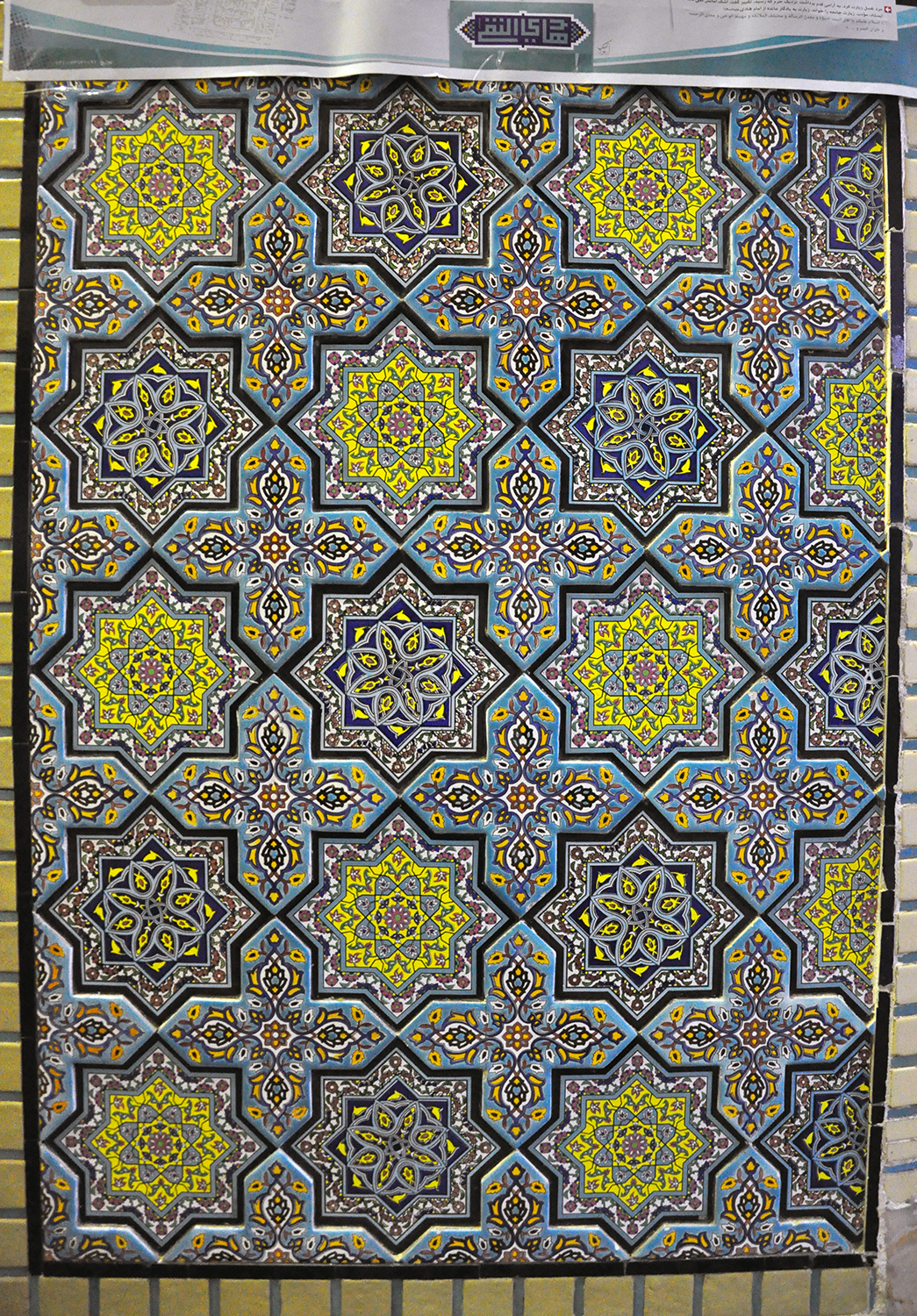

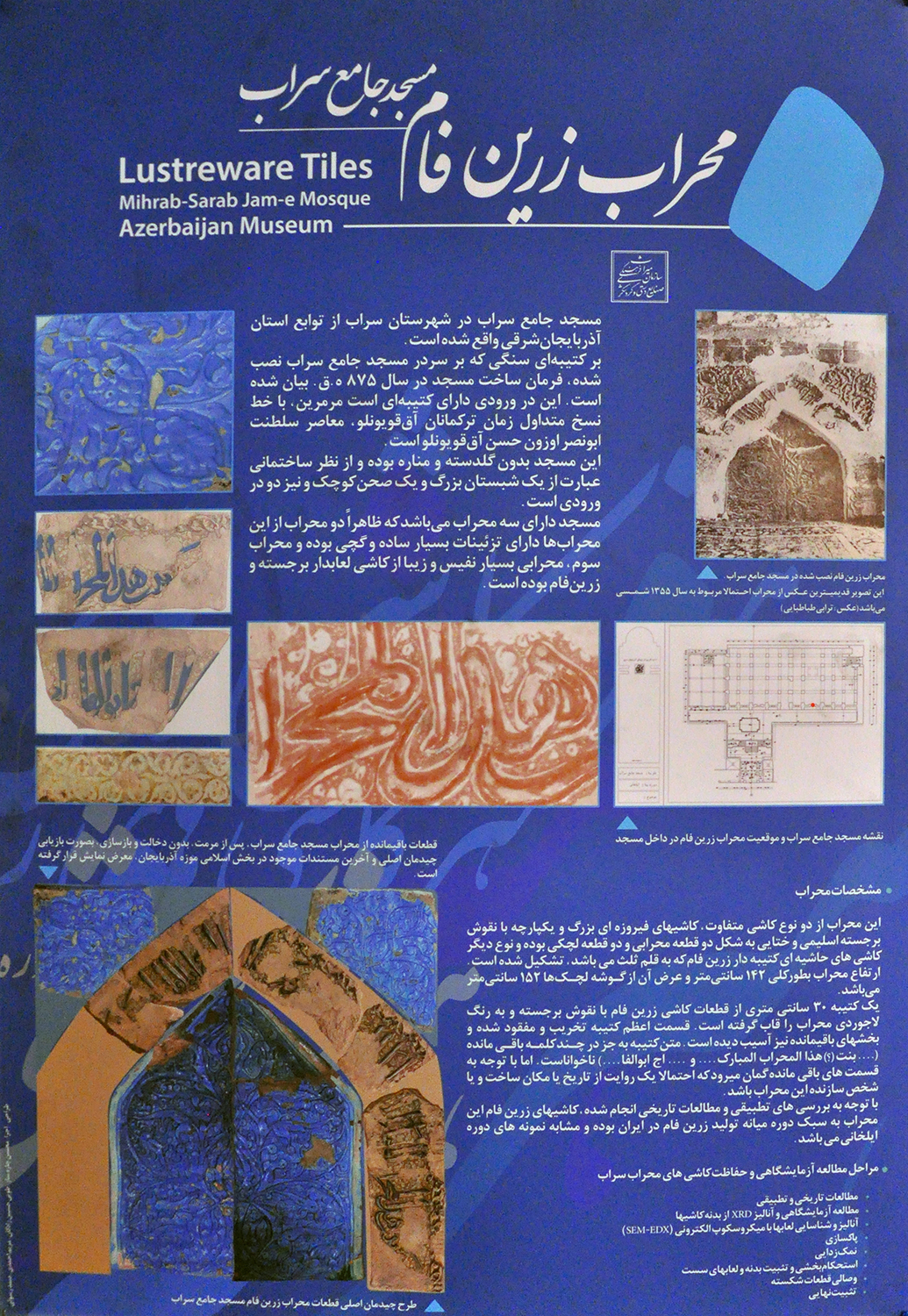

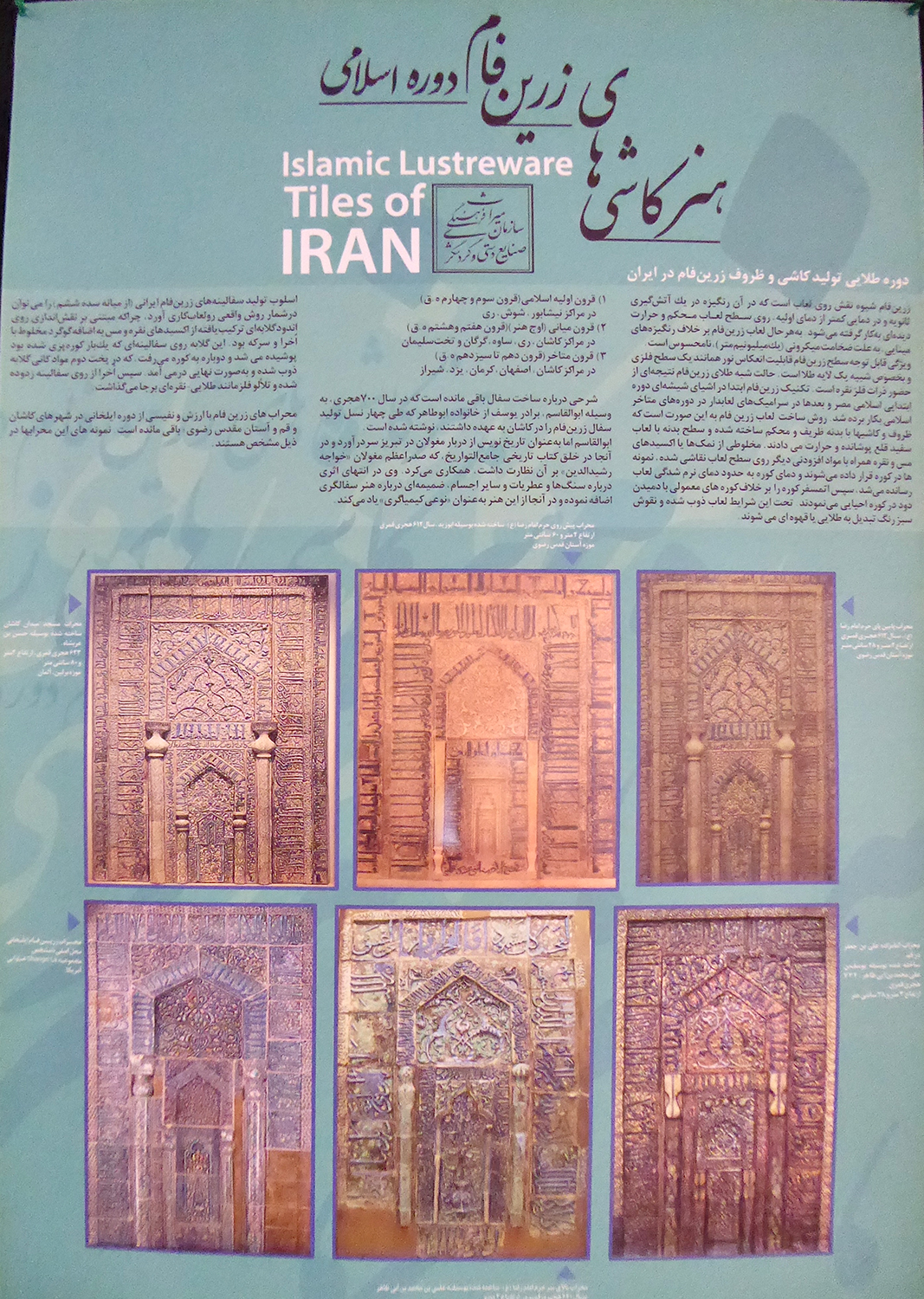

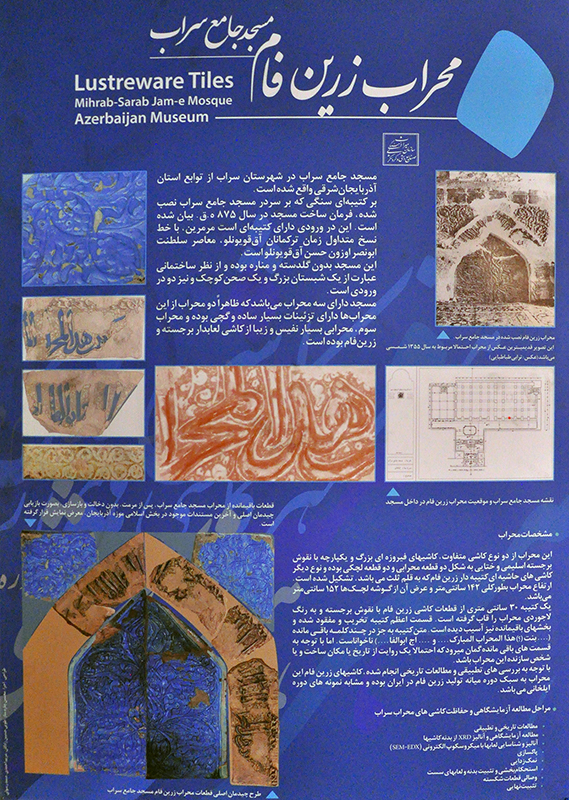

The topic of how museums do and do not address the sites that are the original homes of these displaced tiles is a big one and summarized elsewhere (see the Introduction to the Checklist). For purposes of brevity here, we will simply highlight two positive examples of what we can call ‘site-sensitive’ museum curation. One example is the display of the mihrab from the congregational mosque in Sarab, Iran (map) in the Azerbaijan Museum (map) (fig. 23–24). This display features two large didactics: one about the mosque on the left, including a plan locating the mihrab, and one about the six relatively intact luster mihrabs (fig. 25–26).18 It is perhaps not surprising that this display transpired in a regional museum about eighty miles from the site and was based on the research of a graduate student in conservation.19

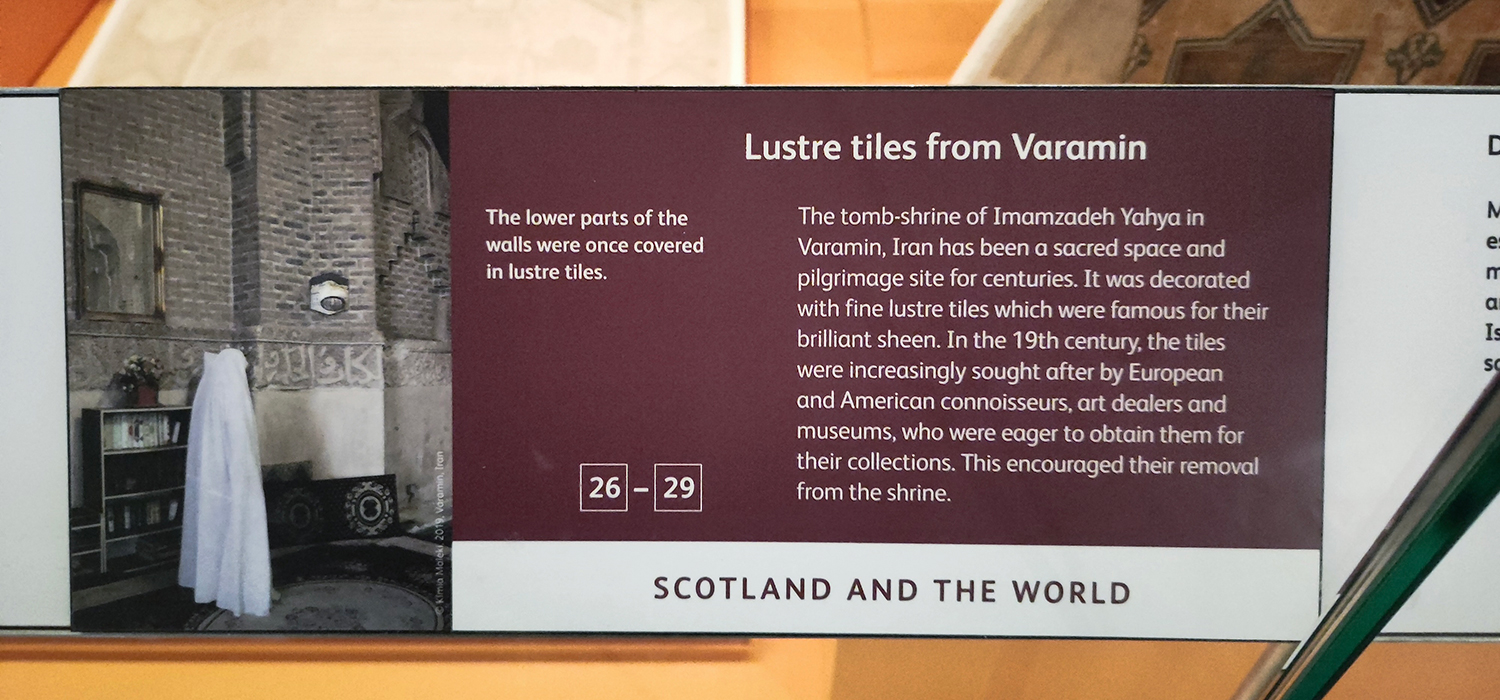

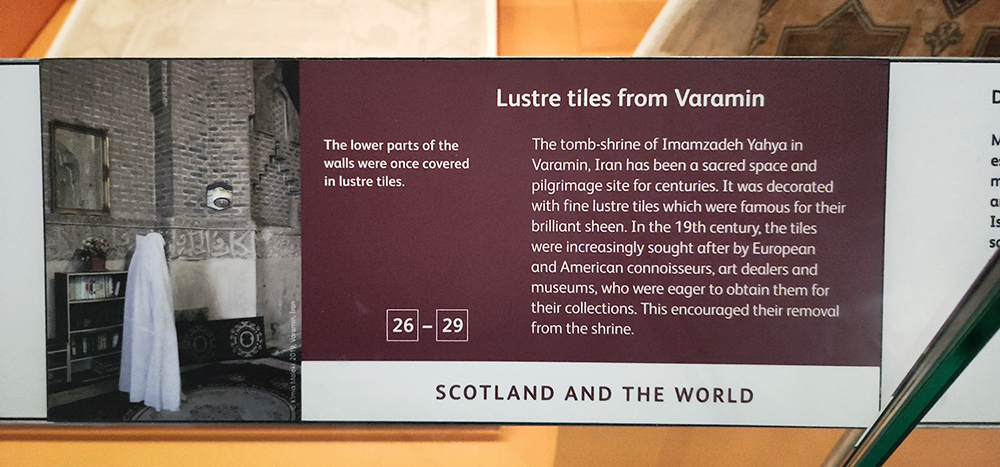

A European example can be found in the National Museum of Scotland (map) in Edinburgh, where the label accompanying a panel of star and cross tiles attributed to the Emamzadeh Yahya includes a photograph of a woman praying in the space (figs. 27–28).20 In this case, the curator reached out to me (Overton) and Kimia Maleki to request this image so that the tomb could be shown as a living sacred space. It is not possible for all museums to incorporate such photographs in their displays, and one of the functions of this online exhibition/website is to fill this interpretive and visual gap.

***

Architectural sites are not merely names on museum labels but rather very real places where the memories of their displaced cultural heritage still endures. This essay is an attempt to foster ongoing dialogue between sites once home to luster tiles and the museums that are now the guardians of this heritage. Doing so requires expanding our knowledge of the sites themselves and remembering that Iranian museums also preserve this material, and often display it in ways that are revealing contrasts to foreign museums. The ongoing demand for luster tiles also means having to adjust how we share our research in open access platforms. In this case, we shifted our initial focus on comprehensive mapping to site-based remembrance, offering another way to perceive these sites and respect their preservation.

A consideration of the Emamzadeh Yahya within this running list of forty-two sites underscores its significance in studies devoted to understanding luster tiles as architectural elements of buildings, rather than standalone objects. The tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya is a relatively rare case of an interior whose tilework can be digitally reconstructed, thanks to limited intervention, some remaining imprints, and primary source texts and photographs that document the tilework in situ (see Digital Tools). In most cases, neither the buildings themselves nor their related archives enable such careful reconstructions.

Citation: Hossein Nakhaei and Keelan Overton, “Sites with Persian Luster Tiles, ca. 1200–1350.” Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.

Notes

- Watson, Persian Lustre Ware, 183–88. ↩

- Kafili, “Luster mihrabs of the Holy Shrine” [in Persian]. ↩

- Vaqefi, Cultural Heritage of Natanz, 52–56, 63–64 [in Persian]; McClary and Grbanovic, “On the Origins of the Shrine of ʿAbd al-Samad in Natanz,” 532–33. ↩

- Hirx et al., “The Glazed Press-Molded Tiles of Takht-i Sulaiman,” 238–40 and fig. 279 (cat. no. 92, a gypsum mold). ↩

- Mohsenian, Survey of Iranian Lustreware [in Persian]; Agha Aligol et al., “Study of the Provenance of Iranian Lusterwares by PIXE Analysis” [in Persian]. In a 1933 article, Abdullah Chughtai suggests that tiles attributed to the Emamzadeh Yahya and now in the Ashmolean Museum were produced in Samarra. See Chughtai, “Lustred Tiles from Samarra in the Ashmolean Museum.” ↩

- On the tomb of Abu Saʿid, see Kuehn, “Tileworks on 12th to 14th century funerary monuments in Urgench (Gurganj).” ↩

- For example, see Watson, “The Masjid-i ʿAlī, Quhrūd.” ↩

- Donabédian and Porter, “Éghvard (Arménie, début du XIVe siècle), La chapelle de l’alliance;” Porter, “‘Talking’ Tiles from Vanished Ilkhanid Palaces.” ↩

- McClary and Grbanovic, “On the Origins of the Shrine of ʿAbd al-Samad in Natanz,” fig. 10. ↩

- Hasani, “Introducing a Fragment of a Luster Tile with a Persian Poem” [in Persian]. ↩

- Another example of quotation can be seen on the façade of the 1477–84 Blue Mosque in Tabriz, where pieces of likely contemporary luster (not Ilkhanid) were integrated into the mosaic revetment of the façade. Sandra Aube, “The Uzun Hasan Mosque in Tabriz,” 58, describes these luster pieces as perhaps “technical experiments.” ↩

- McClary, “Re-contextualizing the object;” Leone, “New Data on the Luster Tiles of ʿAbd al-Samad’s Shrine;” Overton, “Framing, Performing, Forgetting,” fig. 19 and video. ↩

- For an overview, see Masuya, “Ilkhanid Courtly Life,” 91–103. ↩

- Displaced carpets are also sometimes remembered in their original contexts. Consider the replica carpet of the ‘Ardabil carpet’ (VAM 272-1893 and LACMA 53.50.2) in the Shrine of Shaykh Safi al-Din (d. 1334) in Ardabil. ↩

- Overton and Maleki, “The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: A Present History,” fig. 17; Overton, “Framing, Performing, Forgetting,” figs. 12–13. ↩

- A study of this mihrab is forthcoming by Fuchsia Hart and Hossein Nakhaei: “Scattered Tiles, Defaced Birds: The Life of Lustre Tiles in a Contested Site.” ↩

- For the mihrabs in the tomb of Emam Reza, see Kafili, “Luster mihrabs of the Holy Shrine” [in Persian]. For the mihrab once in the Mir Emad mosque, see Ritter, “The Kashan Mihrab in Berlin.” ↩

- For a table listing these six mihrabs and further information, see Blair, “Art as Text,” table 1, 409. ↩

- Hosseinzadegan, “Examination and Study of the Remaining Fragments of Luster Mihrabs from Sarab.” ↩

- The tiles have individual accession numbers. See, for example, star A.1921.1314 A. ↩

Bibliography

This bibliography aims to provide a linguistically balanced resource for the many sites and luster tiles discussed here. For Persian titles, we do not use transliteration and instead provide complete English translations. In the notes, Persian titles are provided in English translation, with [in Persian] noted.

Sources: Persian

- آقا علی گل، داود و دیگران. «مطالعه منشاء تولید سفالینههای زرینفام ایرانی با استفاده از روش آنالیز پیکسی.» در: مقاله نامه کنفرانس فیزیک ایران ۱۳۸۵، ۷۵۴- ۵۷. دانشگاه صنعتی شاهرود، ۱۳۸۵ش. Agha Aligol, Davood et al. “Study of the Provenance of Iranian Lusterwares by PIXE Analysis.” In The Proceedings of the Iranian Physics Conference Article, 754–57. Shahrood: Shahrood University of Technology, 2006. [Civilica]

- اکبری، عباس. کاشی و کاشان. کاشان: خانه سفال، ۱۳۹۸ش. Akbari, Abbas. Kashi and Kashan. Kashan: Ceramic House Institute, 2019.

- امیرحاجلو، سعید و دیگران. «معرفی، طبقه بندی و ساختارشناسی کاشی های زرین فام یافت شده از قلعه دختر شهر کرمان.» در: پژوهه باستانسنجی، شمارهی ۲ (۱۳۹۹ش):۱- ۲۳. Amirhajloo, Saeed, Mohammad Amin Emami, Davood Agha-Aligol, and Reza Riahiyan Gohorti. “Introduction, Classification and Compositional Structure of the Luster Tiles from Qaleh Dokhtar in Kerman.” Journal of Research on Archaeometry 2 (2020): 1–23. [JRA]

- بهرمان، علیرضا. محراب زرینفام حرم مطهر مولی متقیان امام علی (ع): بازخوانی محراب زرینفام هشتصد ساله فراموششده حرم مطهر مولی متقیان امام علی (ع). تهران: طراحان ایماژ، ۱۳۹۷ش. Bahraman, Alireza. The Luster Mihrab of the Holy Shrine of Emam Ali: Revisiting the Eight-Hundred-Year-Old Forgotten Luster Mihrab of the Holy Shrine of Emam Ali. Tehran: Tarrahan-e Emaj, 2019.

- حسنی، میرزامحمد. «معرفی یک قطعه کاشی زرینفام با شعری فارسی از مجموعه بایزید بسطامی.» در: فرهنگ قومس، شمارههای ۵۸-۶۱ (بهار و تابستان ۱۳۹۵ ش):۸۹- ۹۶. Hasani, Mirza Mohammad. “Introducing a Fragment of a Luster Tile with a Persian Poem from the Bayazid Bastami Complex.” Farhang-e Qumes 58, 59, 60, 61 (2016): 89–96. [Noormags]

- حسینزادگان، طوبی. بررسی و مطالعه قطعات بجای مانده از محراب های زرین فام سراب متعلق به موزه آذربایجان و ارائه راهکارهای حفظ و مرمت آن. پایاننامه کارشناسی ارشد، دانشگاه آزاد اسلامی واحد تهران مرکزی، ۱۳۹۲ش. Hosseinzadegan, Tuba. Examination and Study of the Remaining Fragments of Luster Mihrabs from Sarab in the Azerbaijan Museum, and Proposing Conservation and Restoration Solutions. Master’s thesis, Islamic Azad University Central Tehran Branch, 2013. [Elmnet]

- خبرگزاری صدا وسیما. «پایان مرمت کاشیکاری بقعه شیخ عبدالصمد نطنزی.» ۲۴ شهریور ۱۴۰۱ش. IRIB News Agency. “Completion of the preservation of the tilework of the tomb of Shaykh ʿAbd al-Samad Natanzi.” September 15, 2022, https://www.iribnews.ir/00F0Tq.

- سیری، محمدسپهر و سعید امیرحاجلو. «بازنگری محل انتساب هفت قطعه کاشی زرینفام در موزه ملّی ایران؛ اطلاعات باستانشناختی تازهای از دشت لار تهران.» در: مجله موزه ملی ایران، شمارهی ۱ (پاییز و زمستان ۱۳۹۹ش): ۲۱۱-۲۳. Siri, Mohammad Sepehr, and Saeed Amirhajiloo. “Review of Seven Pieces of Luster Tiles in the National Museum of Iran; New Archaeological Finds from Lar Plain in Tehran.” Journal of the Iran National Museum 1 (Autumn 2020 and Winter 2021): 211–23. [Journal of the Iran National Museum]

- شکری، پوریا. گونهشناسی و طبقهبندی کاشیهای دوره ایلخانی تا حمله تیمور بر اساس فرم و لعاب. پایاننامه کارشناسی ارشد، دانشگاه هنر اصفهان، شهریور ۱۳۹۴ش. Shokri, Pouria. Typology and Classification of Tiles during the Ilkhanid era to the beginning of the Timurids, based on Form and Glaze. Master’s thesis, Art University of Isfahan, September 2015.

- قانونی، محسن و سمانه صادقی مهر. «بررسی کتیبهٔ کاشیهای زرینفام مزار حضرت فاطمه معصومه (س) در قم.» در: هنرهای زیبا- هنرهای تجسمی، شمارهی ۲۲/۲ (تابستان ۱۳۹۶ش):۷۷- ۸۸. Ghanooni, Mohsen and Samaneh Sadeghimehr. “Study of the Inscriptions on the Luster Tiles of the Shrine of Hazrat Fatemeh (s) in Qom.” Honarha-ye ziba 22, 2 (2018): 77–88. [University of Tehran, JFAVA]

- کفیلی، حشمت. «محرابهای زرینفام حرم مطهر در موزه مرکزی آستان قدس رضوی.» در: شمسه، شمارهی ۱۸ (بهار ۱۳۹۲): ۱- ۲۸. Kafili, Heshmat. “Luster mihrabs of the Holy Shrine in the Central Museum of Astan Quds Razavi.” Shamseh 18 (2013): 1–28. [Shamseh]

- لشکری، آرش، اکبر شریفینیا و سمیه مهاجروطن. «بررسی نقوش کاشیهای زرینهفام آوه از دوره ایلخانان.» در: نگره، شمارهی ۳۲ (اسفند ۱۳۹۳ش): ۳۸- ۵۴. Lashkari, Arash, Akbar Sharifinia, and Somaieh Mohajervatan. “A Study of Luster Tile Designs from Aveh in Ilkhanid Period.” Negareh 32 (February–March 2015): 38–54. [Negareh]

- محسنیان، محمد. بررسی سفالینههای زرینفام قرون ششم و هفتم ه.ق. ایران به کمک روشهای تجزیه دستگاهی. پایاننامه کارشناسی ارشد، دانشگاه تربیت مدرس، تابستان ۱۳۸۳. Mohsenian, Mohammad. Survey of Iranian Lustreware (sixth and seventh centuries qamari/twelfth and thirteen centuries) by means of Instrumental Analysis. Master’s thesis, Tarbiat Modares University, Summer 2004.

- مدرسی طباطبایی، حسین. تربت پاکان قم. جلد ۲. قم: مهر قم، ۱۳۵۵ش. Tabataba’i, Hossein Modarressi. Tombs of the pious in Qom, vol. 2. Qom: Mehr-e Qom, 1977. [WorldCat]

- مشهدی نوشآبادی، محمد و حمیدرضا جیحانی. «قدمگاه امام علی (ع)؛ در جستجوی تربتخانه ایلخانی کاشان.» در: مطالعات معماری ایران، شمارهی ۱۸ (پاییز و زمستان ۱۳۹۹ش) ۸۹- ۱۱۲. Mashhadi Noushabadi, Mohammad, and Hamidreza Jayhani. “Qadamgah-e Emam ʿAli: In Search of the Ilkhanid Turbat-khaneh of Kashan.” Journal of Iranian Architecture Studies 18 (2022): 89–112. [JIAS]

- مشهدی نوشآبادی، محمد و محمدرضا غیاثیان. «رؤیانگاری بر کاشی زرینفام در دو بنای قدمگاهی کاشان از دوران ایلخانی و صفوی.» در: فرهنگ و ادبیات عامه، شمارهی ۳۷ (فروردین و اردیبهشت ۱۴۰۰ش) ۱۰۱- ۳۱. Mashhadi Noosh Abadi [Noushabadi], Mohammad, and Mohamad Reza Ghiasian. “The Writing of Dreams on Lustre Tiles in Two Qadamgāhs in Kashan from the Ilkhanid and Safavid Periods.” Culture and Folk Literature 37 (March & April 2021): 101–31. [Tarbiat Modares University]

- واقفی، حسین اعظم. میراث فرهنگی نطنز: آثار تاریخی، آداب و سنتها و تاریخ نطنز. ج. ۱. نطنز: حسین اعظم واقفی، ۱۳۷۴. Vaqefi, Hossein Azam. Cultural Heritage of Natanz: Historical Monuments, Customs and Traditions, and the History of Natanz, vol. 1. Natanz: Hossein Azam Vaqefi, 1995. [WorldCat]

- ورجاوند، پرویز. کاوش رصدخانه مراغه و نگاهی به پیشینه دانش ستارهشناسی در ایران. تهران: امیرکبیر، ۱۳۶۶ش. Varjavand, Parviz. Excavation of the Maragheh Observatory and a Review of the History of Astronomy in Iran. Tehran, AmirKabir, 1987. [WorldCat]

Sources: English, French, German

- Aube, Sandra. “The Uzun Hasan Mosque in Tabriz: New Perspectives on a Tabrizi Ceramic Tile Workshop.” Muqarnas: An Annual On The Visual Cultures Of The Islamic World 33 (2016): 33–62. [Archnet]

- Blair, Sheila. “Art as Text: The Luster Mihrab in the Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art.” In ‘No Tapping around Philology’: A Festschrift in celebration and honor of Wheeler McIntosh Thackston’s 70th Birthday, edited by Alireza Korangy and Daniel Sheffield, 407–36. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2014. [Academia]

- Chughtai, Abdullah. “Lustred Tiles from Samarra in the Ashmolean Museum.” Islamic Culture 7, 3 (July 1933): 472–76. [Noormags]

- Donabédian, Patrick, and Yves Porter. “Éghvard (Arménie, début du XIVe siècle), La chapelle de l’alliance.” Hortus artium medievalium: Journal of the International Research Center for Late Antiquity and Middle Ages 23, 2 (2017): 837–55. [HAL]

- Grbanovic, Ana Marija. “Lost and Found: The Ilkhanid Tiles of the Pir-i Bakran Mausoleum (Linjan, Isfahan).” Iran 61 (2023): 235–54. [Taylor & Francis]

- Haeri, Mohammad-Reza. “Kashan v. Architecture (2) Historical Monuments.” Encyclopaedia Iranica, May 1, 2012, https://iranicaonline.org/articles/kashan-v2-historical-monuments.

- Hart, Fuchsia, and Hossein Nakhaei. “Scattered Tiles, Defaced Birds: The Life of Lustre Tiles in a Contested Site.” In The Complex of ‘Abd al-Samad in Natanz: Context and Decoration, edited by Anaïs Leone, Richard Piran McClary, and Yves Porter. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press, forthcoming 2025.

- Hirx, John, Marco Leona, and Pieter Meyers. “Technical Study 2: The Glazed Press-Molded Tiles of Takht-i Sulaiman.” In The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256–1353, edited by Linda Komaroff and Stefano Carboni, 233–42. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2002. [MetPublications]

- Kuehn, Sara. “Tilework on Funerary Monuments of the 12th to 14th Century in Konya Urgench (Gurganj).” Arts of Asia 38, 2 (2007): 1–18 [Sara Kuehn]

- Leone, Anaïs. “New Data on the Luster Tiles of ʿAbd al-Samad’s Shrine in Natanz, Iran.” Muqarnas 38, 1 (2021): 331–56. [Muqarnas]

- Masuya, Tomoko. “Ilkhanid Courtly Life.” In The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256–1353, edited by Linda Komaroff and Stefano Carboni, 74–103. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2002. [MetPublications]

- McClary, Richard. “Re-contextualizing the object: Using new technologies to reconstruct the lost interiors of medieval Islamic buildings.” International Journal of Islamic Architecture 7, 2 (2018): 263–83. [White Rose]

- McClary, Richard, and Ana Marija Grbanovic. “On the Origins of the Shrine of ʿAbd al-Samad in Natanz: The Case for a Revised Chronology.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 32, 3 (2022): 501–34. [Cambridge Core]

- Naumann, Rudolf, and Elisabeth Naumann. Takht-i Suleiman. München: Prähistor. Staatssammlung, 1976. [WorldCat]

- Overton, Keelan and Kimia Maleki, “The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: A Present History of a Living Shrine, 2018–20.” Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World 1 (2020): 120–49. [Brill]

- Overton, Keelan. “Persian Luster Tilework between the Field and Museum.” Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online, March 24, 2022. [Khamseen]

- Overton, Keelan. “Framing, Performing, Forgetting: The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin.” Platform, September 19, 2022, https://www.platformspace.net/home/framing-performing-forgetting-the-emamzadeh-yahya-at-varamin.

- Porter, Yves. “Use and Reuse of Persian Luster Tiles.” In Under the Adorned Dome, Four Essays on the Arts of Iran and India, 106–43. Leiden: Brill, 2023. [Brill]

- Porter, Yves. “‘Talking’ Tiles from Vanished Ilkhanid Palaces (Late Thirteenth to Early Fourteenth Centuries): Frieze Luster Tiles with Verses from the Shah-nama.” Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World 2, 1–2 (2021): 97–149. [Brill]

- Ritter, Markus. “The Kashan Mihrab in Berlin: A Historiography of Persian Lustreware.” In Persian Art: Image-making in Eurasia, edited by Yuka Kadoi, 157–78. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. 2018. [JSTOR]

- Rougeulle, Axelle, Thomas Creissen, and Vincent Bernard. “The Great Mosque of Qalhāt Rediscovered. Main Results of the 2008–2010 Excavations at Qalhāt, Oman.” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 42 (2012): 341–56. [JSTOR]

- Watson, Oliver. Persian Luster Ware. London: Faber and Faber, 1985. [Academia]

- Watson, Oliver. “The Masjid-i ʿAlī, Quhrūd: An Architectural and Epigraphic Survey.” Iran 13 (1975): 59–74. [JSTOR]