The Stucco Inscription in the Tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya: From Architectural Ornament to Historical Memory

Keelan Overton and Hossein Nakhaei

With a filmed recitation by Ahmad Khamehyar

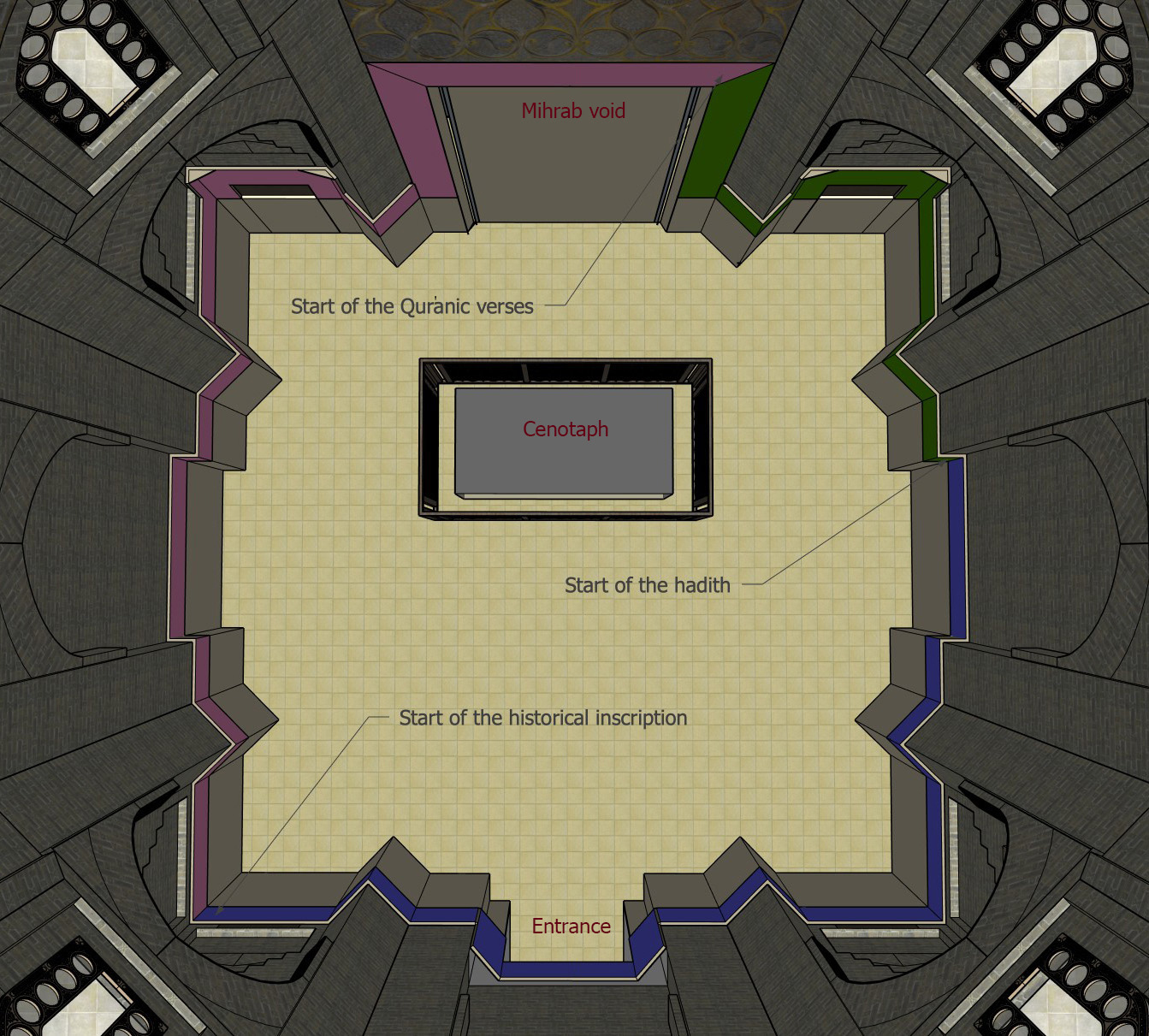

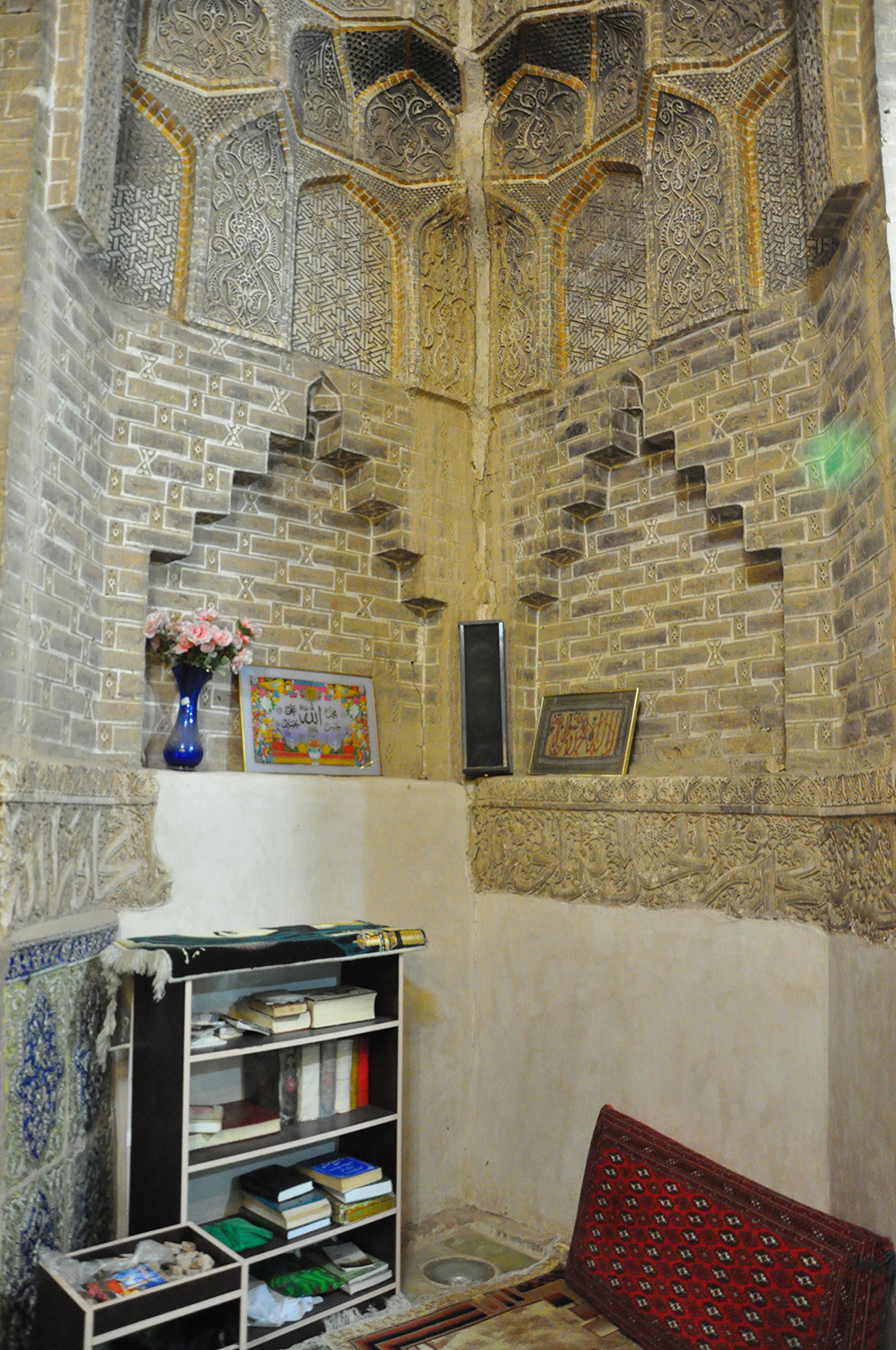

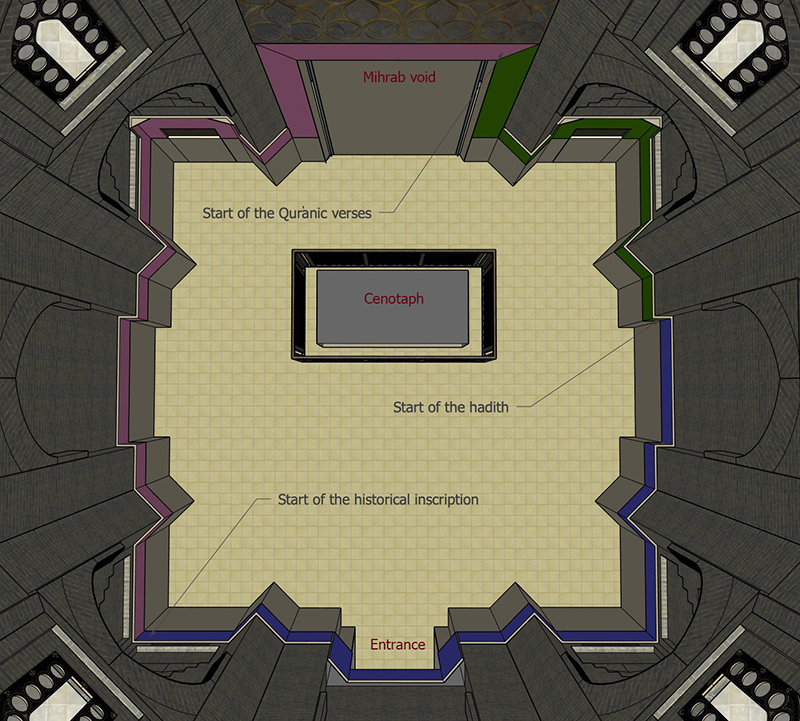

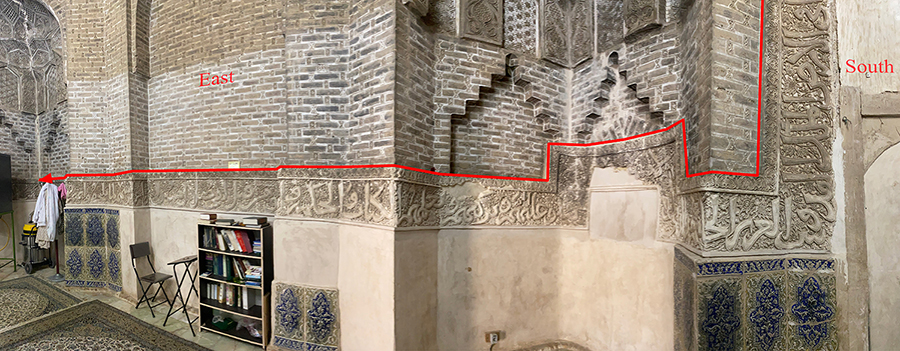

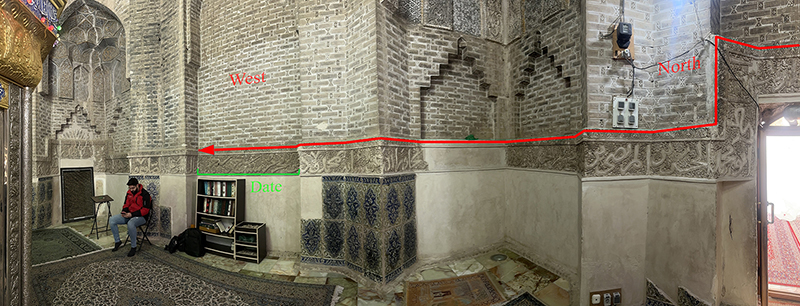

The stucco inscription inside the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya is one of the most important features of the Ilkhanid-period (1256–1353) interior. Wherever one stands in the tomb, one sees this inscription, which wraps around the space and is mostly visible at eye-level (approximately 4 feet high, or 1.2 meters), hence easily seen, read, and touched (figs. 1–2). The inscription contains three distinct texts—Qurʾanic verses, a foundation inscription, and a hadith (fig. 3)—and is an excellent example of stucco craftsmanship. In this essay, we explore the epigraphy’s content, reception, and preservation and offer a filmed recitation that facilitates its holistic appreciation through sound and space.1

Overview: Layout and Texts

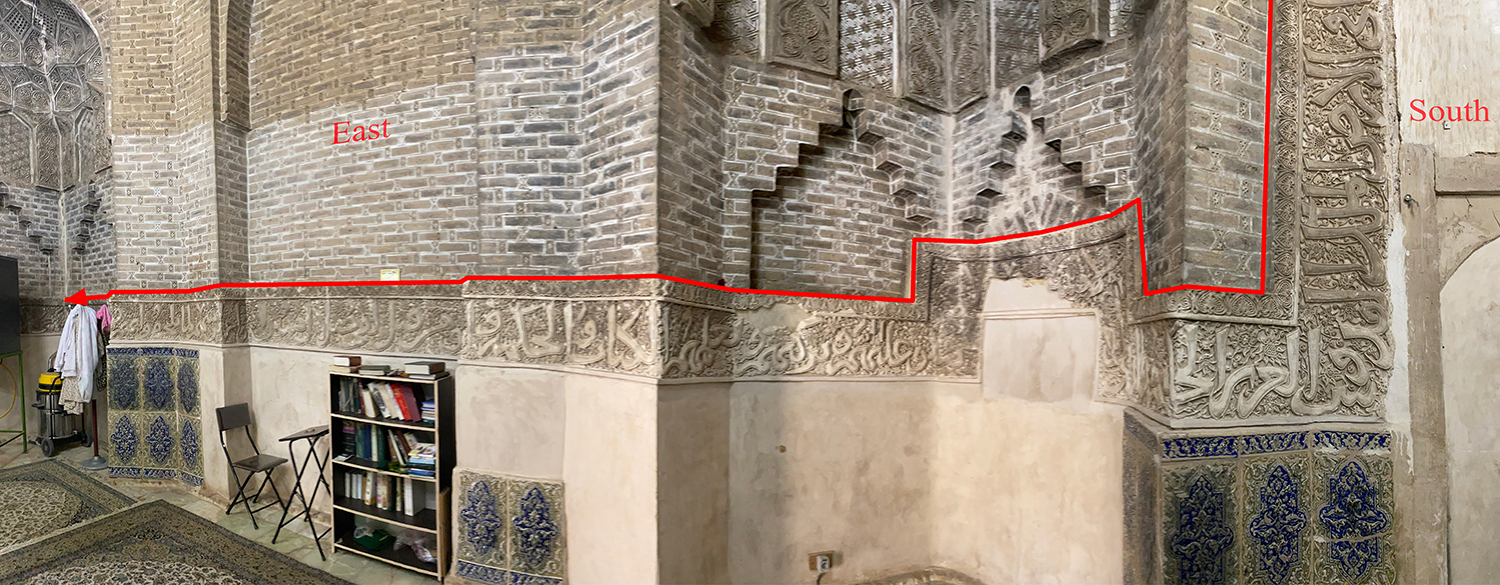

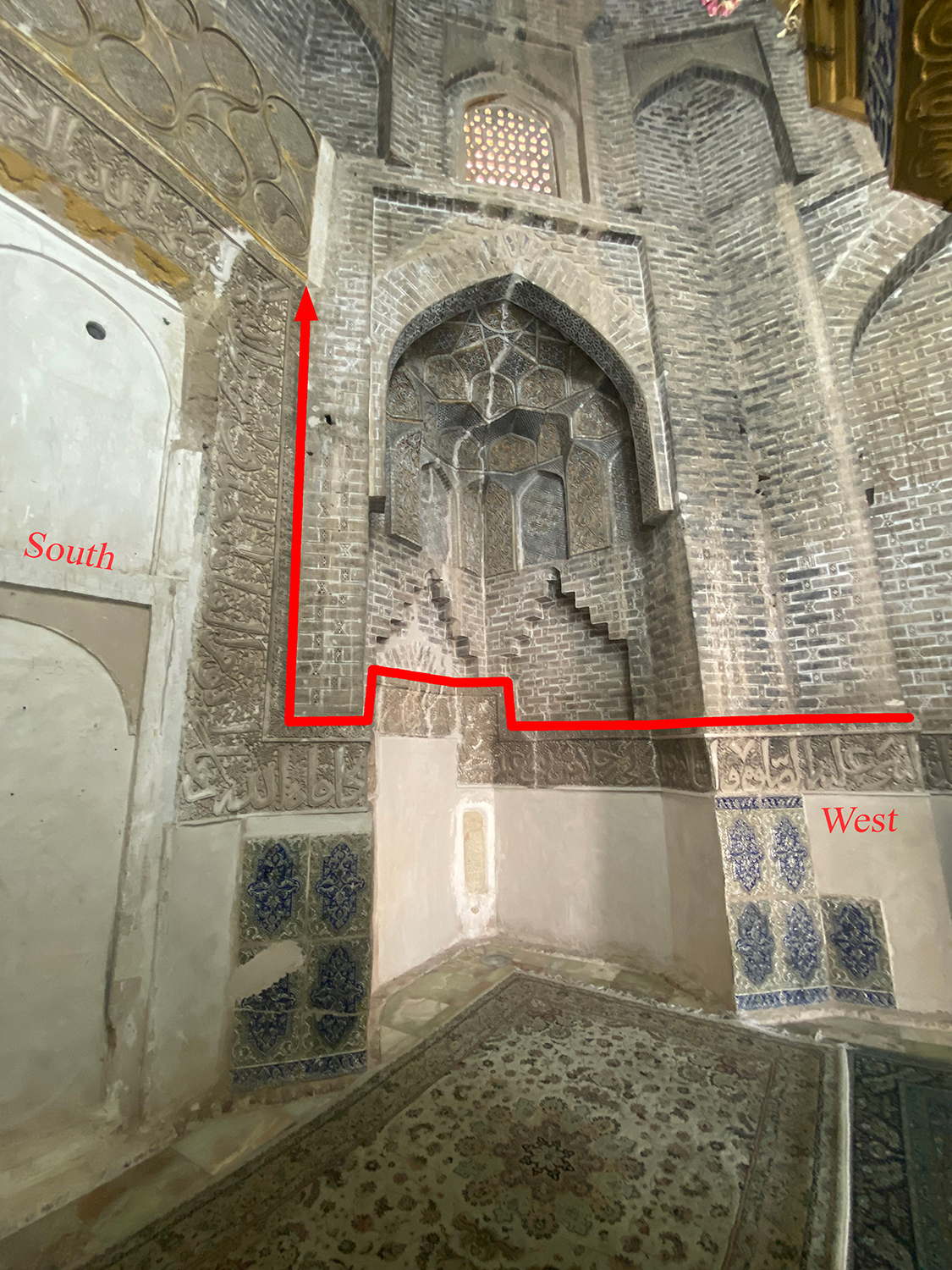

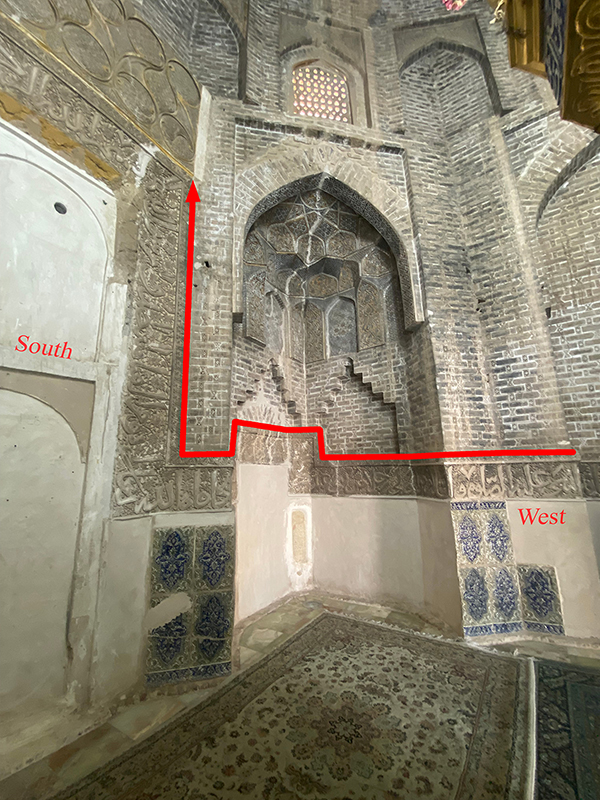

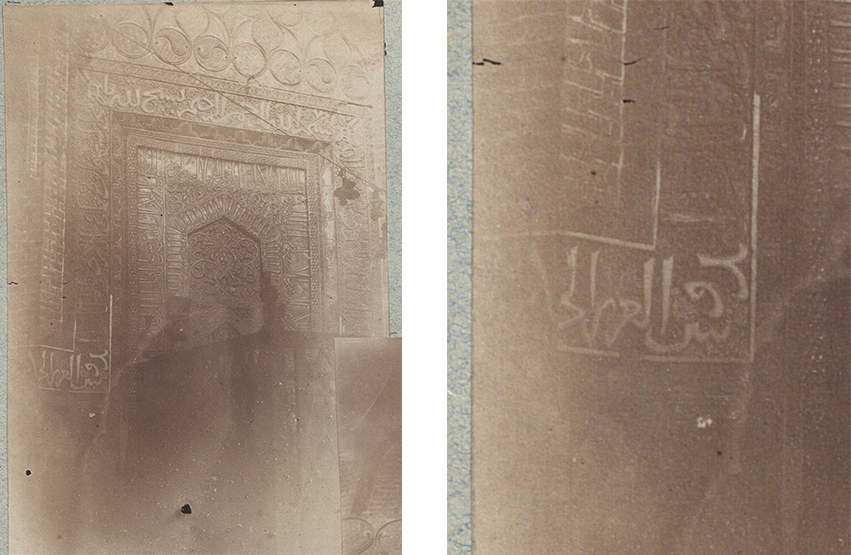

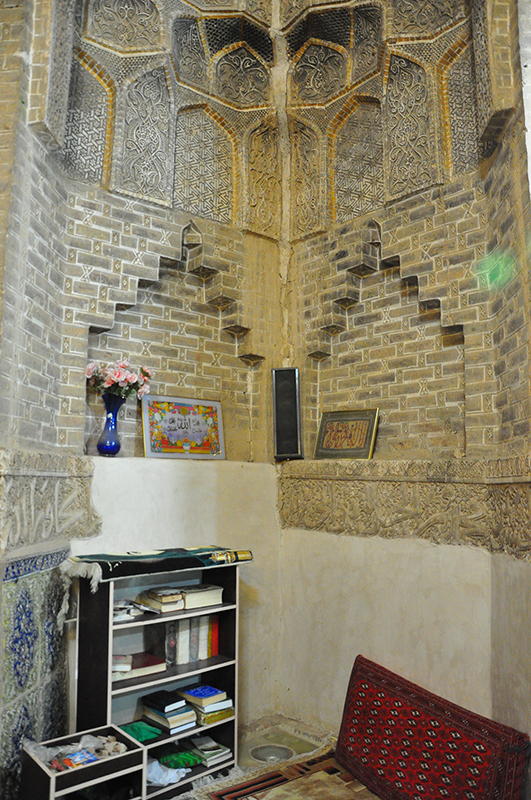

The inscription wraps around the entire interior, shifting in height depending on what it frames and undulating with the dynamic contours of the walls (notice the segmented surfaces in fig. 3). The highest point of the band is on the qibla (south) wall, where it originally framed the luster mihrab dated 663/1265 (fig. 4). The basmala begins on the upper right and transitions into the first verse of sura al-Jumuʿah (The Friday Congregation). Directly below are the imprints of luster half star and cross tiles that once also framed the mihrab (fig. 5). During the removal of these tiles in the second half of the nineteenth century, the adjacent edges of the stucco inscription were severely damaged. Some letters appear to bear traces of the tools used by the thieves to pry loose the tiles (fig. 6).

The sura continues down the left side of the mihrab and into the southeast corner, where it juts upwards to accommodate a previous exit. Some significant loss is visible in the words امیین and رسولا (fig. 7). It continues along the entire east wall at a consistent height, folding with the shifting walls (see fig. 3).

These popular Qurʾanic verses are also rendered in stucco in the domed sanctuary of Varamin’s congregational mosque. Dated 726/1326, this inscription is much higher up the wall (approximately 27 feet, or 8.3 meters), at the base of the zone of transition, and hence physically out of reach (fig. 8).2

In the northeast corner of the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya, the inscription transitions into a historical document recording the full name and titles of the patron and ending with the date of Moharram 707/ July–August 1307 in the middle of the west wall. The length of this foundation inscription, taking up more than one third (almost 40%) of the total surface area, is notable (see the blue portion in fig. 3) (fig. 9). In the northwest corner, a large portion of the inscription is entirely missing.

Finally, in the southwest corner, the inscription transitions into a hadith, a saying attributed to the Prophet Mohammad (fig. 10). This hadith, which has not been found in any other known building to date, highlights the divine reward for showing kindness and support to the Prophet’s family and his descendants.

Inscriptions within an Inscription

In addition to being an integral part of the tomb’s architecture, historical document of the Ilkhanid period, and sacred text on several levels, the stucco inscription functioned as an interactive element during personal ziyarat (زیارت, pious visitation). From at least 750/1349 to 1345 Sh/1966, pilgrims wrote minute inscriptions (یادگاری, yadegari) in black script on the surfaces of its large letters (about 8 inches, or 20 cm in height) (fig. 11).3 As discussed by Nazanin Shahidi Marnani in her essay here, most of these yadegari include verses of Persian poetry, some by well-known poets. As such, the stucco inscription is also a poetic anthology on the wall that allows us to begin to tap the literary mindsets of the tomb’s pilgrims.

The inscription’s delicate stucco material, accessible height, and presence in a continuously used interior have made it vulnerable to many forms of damage and in turn necessitated continuous preservation (مرمت), including surface cleaning and structural consolidation. The majority of the surviving readable yadegari are on the west side of the interior, but we can assume that many more were once present. By June 1881, a degree of cleaning had transpired around the left (east) side of the mihrab, as clear in the abrupt transition between dark and light zones in Jane Dieulafoy’s photograph (fig. 12). The darkening of the inscription was likely cumulative and caused by smoke and soot (unburned black carbon) from candles and oil lamps. The white substance visible today over the yadegari in the letter ل suggests that this intervention included overpainting (figs. 13–14). Thankfully, the line of Salman Savaji (d. 1376) in this yadegari can still be discerned (Shahidi Marnani, no. 8, fig. 20).

Other areas of the stucco inscription, including the date on the west wall, have a shiny surface suggestive of possible touching over time (figs. 15–16). We can imagine that some pilgrims would have run their fingers over the inscription during the tactile experience of ziyarat, seeking to absorb the baraka (blessing) of the sacred space (see Parsapajouh’s essay).

Some letters exhibit a significant level of scratching that seems to indicate deliberate erasure of the yadegaris (fig. 17).

Recitation

In this film, historian Ahmad Khamehyar recites the entire stucco inscription in one take, reanimating it through sound, sight, and movement (vid. 1). The process takes about three minutes, and the act of reading is relatively easy for one familiar with the texts. The inscription is physically close (mostly within arm’s reach), the letters are large (about 8 inches in height), and the cursive sols (thuluth) script is generally clear. The tomb is also well lit and not too crowded on this cold day in January, save for a few children and adults (fig. 18). The biggest challenges to reading are a few modern elements blocking the inscription and a few missing parts (notably in fig. 9). The close and steady panning over the words allows the viewer to notice many details and changes in condition and surface, including targeted repairs and shifts from light to dark.

Video 1. Dr. Khamehyar begins above the mihrab with the basmala and continues counterclockwise around the interior. Video by Hamid Abhari, January 2024 (~4 minutes, with sound).

This twenty-first century reading begs the question of how the inscription would have been experienced in the past. The extant yadegari dated between 1349 and 1966 confirm that pilgrims physically interacted with the inscription of over six centuries. Whether or not they actually read it remains to be known, and which part(s).4 Did they circumambulate the tomb, reading some of the original Ilkhanid text as Dr. Khamehyar has done here? Would the first four verses of sura al-Jumuʿah have been immediately familiar to most fourteenth-century visitors and not necessarily read word for word? Did some pilgrims stand in place, poring over the yadegaris of others, deciphering, recognizing, and enjoying these famous Persian verses? While these questions cannot be answered, simply posing them helps us to appreciate this multi-textual and multi-dimensional writing on the wall.

Transcription and Analysis

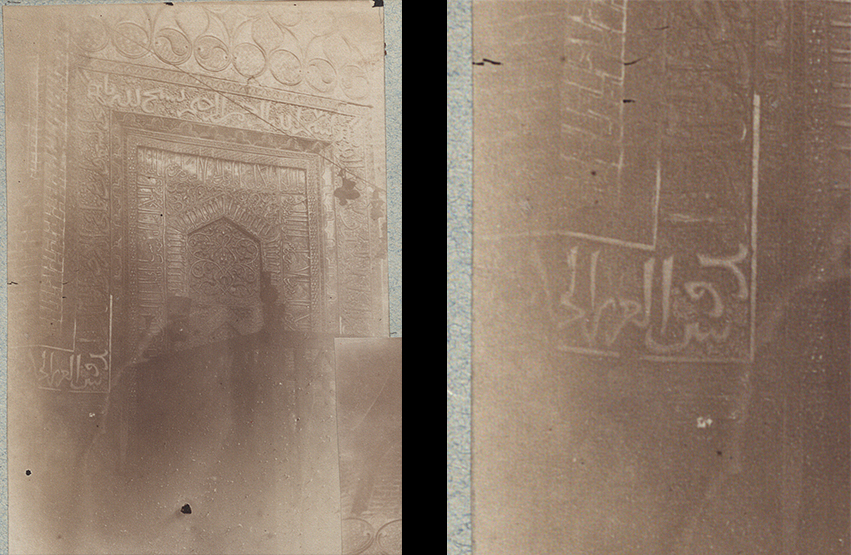

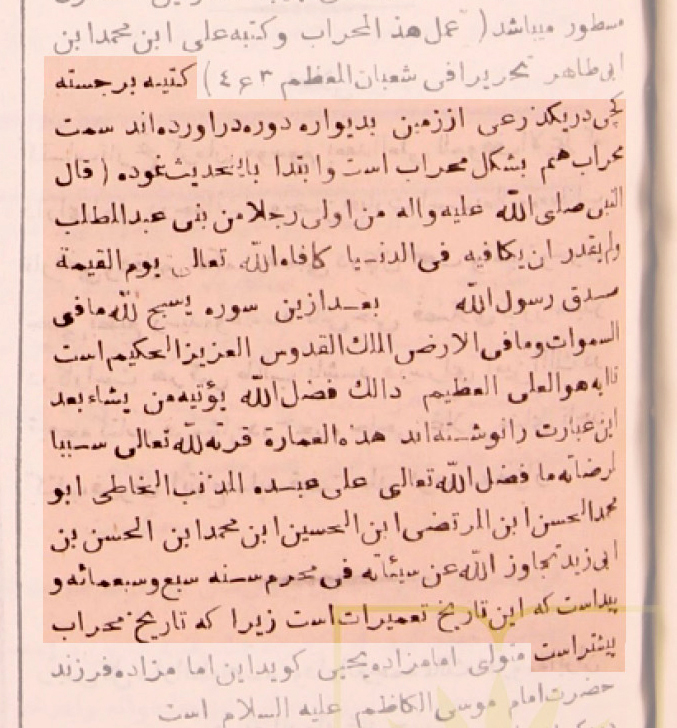

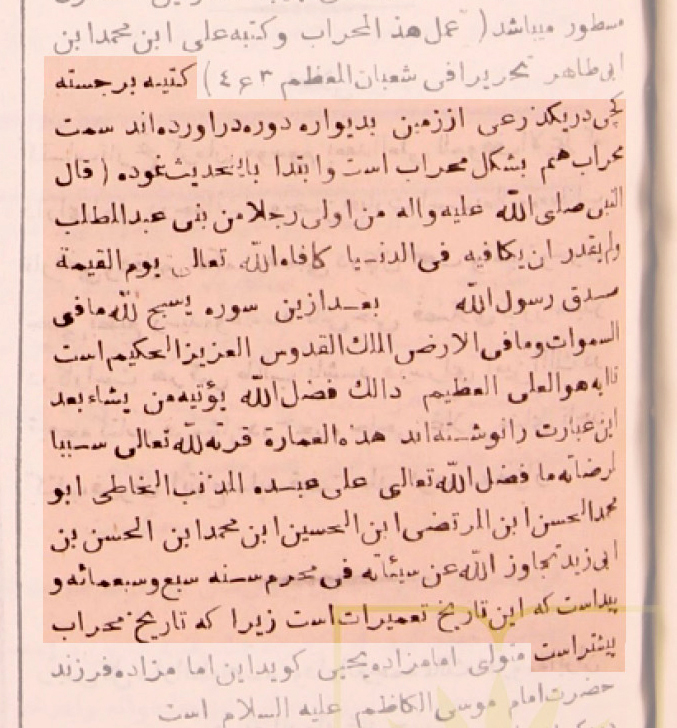

This analysis of the stucco inscription builds on three precedents, each of which has approached it in a distinct way. The first known recording and partial transcription occurred at the order of ʿAliqoli Mirza Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh (d. 1880) in January 1863 (see Textual Source). In December 1876, Mohammad Hasan Khan Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh (d. 1896) visited the tomb and soon published an almost entire transcription in his newspaper Iran. Unlike Dr. Khamehyar here, Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh began with the hadith and explicitly stated that the inscription started with the hadith (fig. 19).5

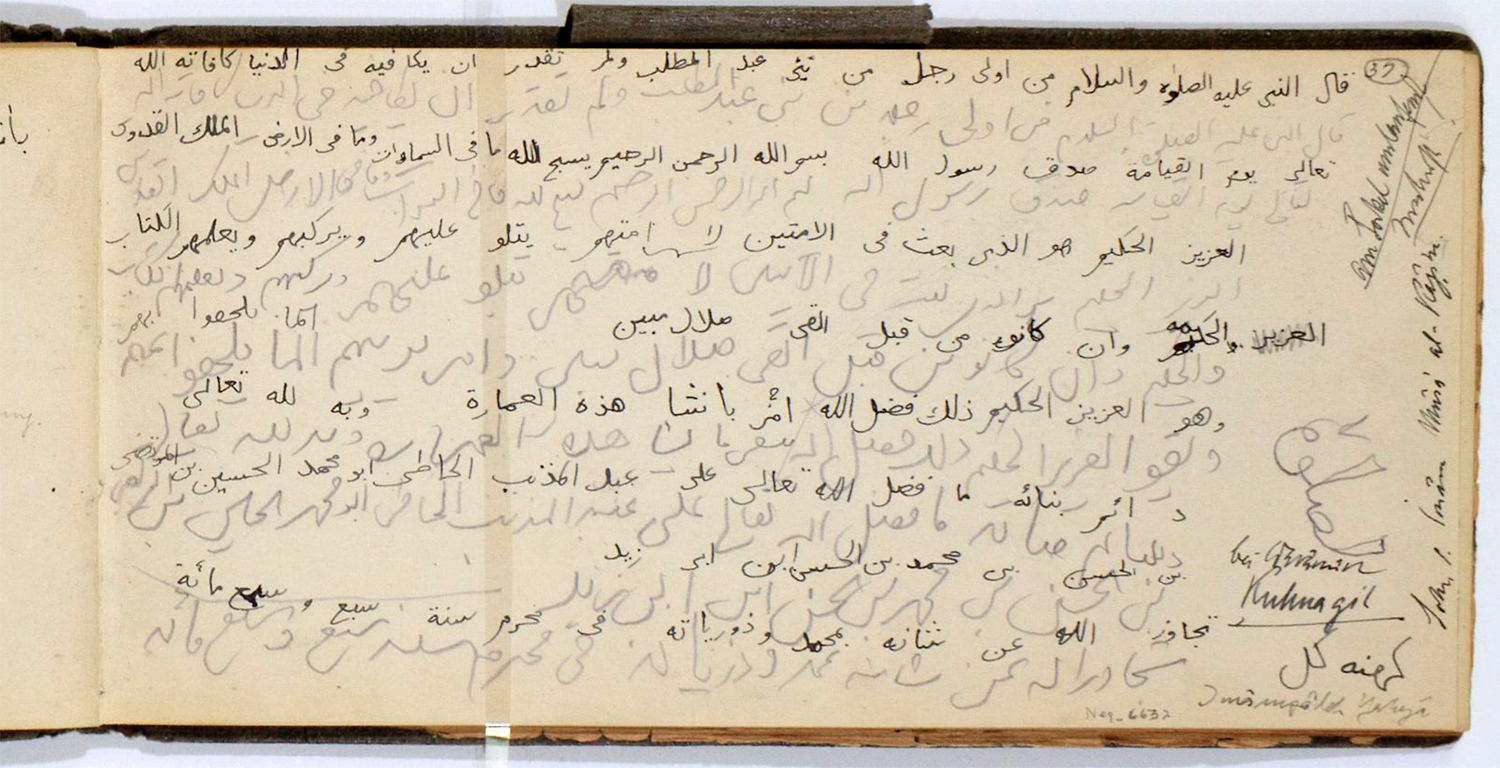

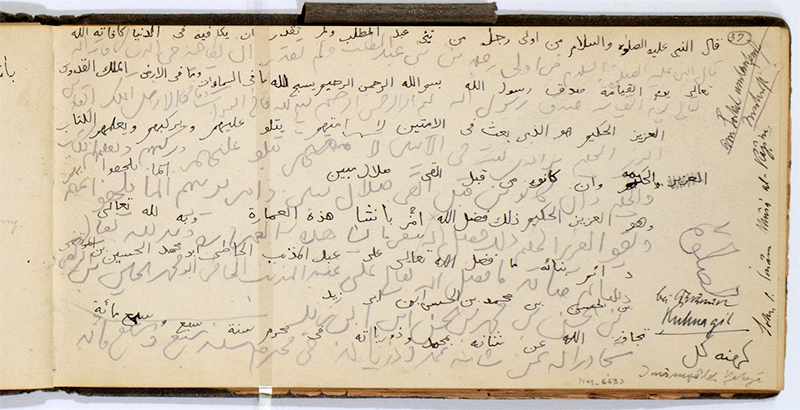

In 1923, German archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld (d. 1948) recorded a complete transcription in one of his sketchbooks, also beginning with the hadith and ending with the date (fig. 20). In his transcription, which was written in pen and then corrected in pencil, Herzfeld left a long gap in the missing portion of the patron’s name (discussed further below). In the lower right corner of the page, he wrote the name of the ‘Imāmzâdeh Yahyā’ and its location in ‘Kuhnagil’ (Kohneh Gel). By this time, all of the tomb’s luster tilework had been stolen, and Herzfeld appears to have been one of the first western scholars allowed into the tomb in the early twentieth century. It would take another three decades for the stucco inscription to be partially published in the Répertoire chronologique d'épigraphie arabe.6

Note: [ ] indicates parts of the inscription that have been lost

I.

Sura al-Jumuʿah, verses 1-4

سوره جمعه، آیات ۱-۴

بسم الله الرحمن الرحیم

یسبح لله ما فی السّموات وَ ما فی الارض الملک القدوس العزیز الحکیم (۱)

هُو الذی بعث فی الامیی[ن رسو]لا منهم یتلو علیهم آیاته وَ یزکیهم و یعلمهُم الکتاب وَ الحکمه و ان کانو من قبل لفی ضلال مُبین (۲)

و اخرین منهم لما یلحقُوا بهم و هُو العَزیز الحکیم (۳)

ذلک فضلُ الله ... (جمعه، ۴)

Translation by Dr. Mustafa Khattab (Quran.com):

In the Name of Allah—the Most Compassionate, Most Merciful.

Whatever is in the heavens and whatever is on the earth [constantly] glorifies Allah—the King, the Most Holy, the Almighty, the All-Wise. (1)

He is the One Who raised for the illiterate [people] a messenger from among themselves—reciting to them His revelations, purifying them, and teaching them the Book and wisdom, for indeed they had previously been clearly astray— (2)

along with others of them who have not yet joined them [in faith]. For He is the Almighty, All-Wise. (3)

This is the favor of Allah … (4)

The inscription’s orthography largely aligns with the current standardized Qurʾan, with two main distinctions: absence of dots (often key parts of individual letters) and infrequent harakat diacritics (short vowel marks indicating pronunciation). All words are outlined by a thin contour, except for the word آیاته in the middle of the second verse. This word, which shows signs of damage, is also much smaller than the others, suggesting that it might have been forgotten initially and added later (figs. 21–22).

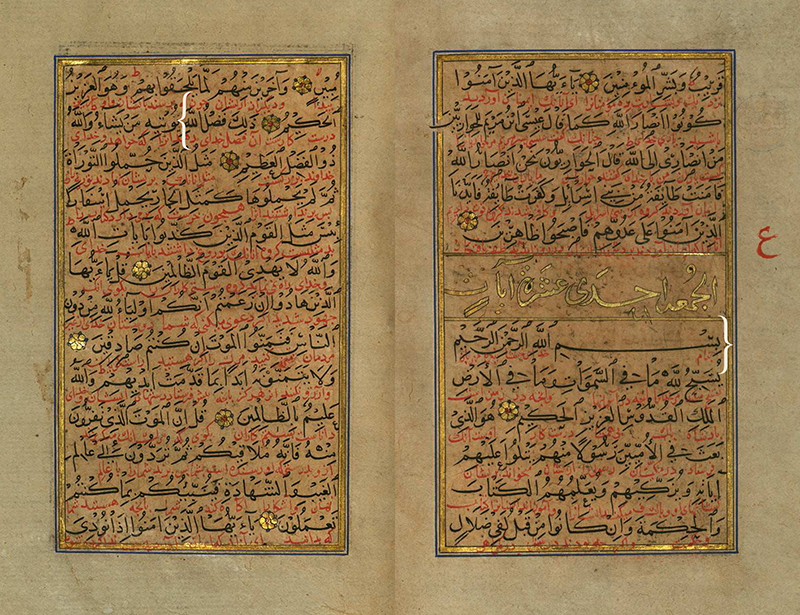

Based on comparison to corresponding verses in an Ilkhanid Qurʾan dated 723/1323, only the first three words of the fourth verse were included in the tomb’s stucco inscription, leaving off the remaining seven (fig. 23). Given that the other two sections of the inscription (foundation and hadith) appear complete, it is likely that the decision to cut short the fourth verse was affected by the available space on the wall. The transition between the Qurʾanic verse and the foundation inscription appears neatly in the northeast corner (figs. 24–25).

II.

Foundation inscription dated Moharram 707 (July–August 1307)

کتیبه احداثیه به تاریخ محرم ۷۰۷ قمری

سَعی بانشا هذه العمارة قُربه لله تَعالی و سَببا لمرضاته ما فضل الله تَعالی علی عبده المذنب الخاطی ابومحَمد الحسن بن المرتضی بن الحَسن بن مُحمد بن الحسن بن ابیزید [...] ا تجاوزَ الله عن سیأته بمحمد و ذریَاته فی مُحرم سنه سبع و سبع مایه

Translation: Efforts were made to construct this building as an act of devotion to God Almighty and a means to seek his pleasure. By the grace that God bestowed upon His sinful and erring servant, Abu Mohammad al-Hasan ibn al-Morteza ibn al-Hasan ibn Mohammad ibn al-Hasan ibn Abi Zayd [...]. May God forgive his sins through [Prophet] Mohammad and his descendants, in Moharram of the year seven hundred and seven.

The widely accepted transcription of this part of the inscription dated Moharram 707 (July–August 1307) was first published in the Répertoire in 1954 and later repeated by Sheila Blair.7 In these publications, certain words, specifically سببا and the ما before فضل, were inaccurately transcribed. In 1988, Abdullah Ghouchani revised the text and corrected the inaccuracies in the earlier transcription but overlooked the الحسن before ابیزید at the end of the patron’s name.8

The foundation inscription is notable for being the only part of the epigraphic band with an area of total loss. This loss appears in the northwest corner at the end of the patron’s name (fig. 26). In comparison to the southeast corner, where two words of the sura were partially damaged (see fig. 7), no words remain here, and the original content can only be surmised.

In his 1988 article, Ghouchani argued that the missing section likely included the end of the name of the patron—Malek Fakhr al-Din (Fakhroddin) Hasan (d. 1308)—as it was followed by a phrase asking for God’s forgiveness.9 If we agree with this assumption, the ending was likely الحسینی الورامینی (al-Hosayni al-Varamini). This ending also appears after Fakhr al-Din’s name in an endowment document dated 703/1304 and in the inscription at the top of his father’s tomb in Varamin, the tower of ʿAlaoddin (see Architectural Heritage).10 As such, it appears to have been the family’s preferred styling and official designation, indicating both their lineage (descent from Emam Hosayn) and origin. Two letters still visible at the very end of the lost segment (ر, ز or ن, followed by ا) could, however, complicate this interpretation (fig. 27).11

While the missing words remain debatable, their linkage to Fakhr al-Din is not, and their complete loss might indicate a deliberate eradication of the key part of his name. Such acts of erasure are often politically or personally motivated and can be seen in many other historical monuments in Iran and beyond, and even the Emamzadeh Yahya’s own yadegari (see fig. 17).12 If indeed targeted vandalism, this loss is yet another layer of history embedded in the stucco inscription and a second form of calculated destruction in the tomb. While the tomb’s luster tiles were stolen during the second half of the nineteenth century, we cannot be sure when the name was effaced.

The foundation inscription is the only surviving historical document in the tomb that explicitly references its construction, but it contains several ambiguities at the start: سَعی بانشا هذه العمارة (Efforts were made to construct this building). The first concerns the term انشا (enshā), which means ‘to construct or build.’ It is unclear if this term refers to the commencement or completion of construction, but given the earlier dates on the luster tiles (1262–1305) and the death of Malek Fakhr al-Din Hasan a few months after the date of this inscription, the latter is probable. The second set of ambiguities concerns the term العمارة (al-ʿimārah). Since the current tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya was originally part of a larger medieval complex, it is unclear whether العمارة referred exclusively to the domed tomb or perhaps the entire complex.13 It is also unclear if the ‘efforts’ in question were new construction or renovations to something pre-existing. Blair argues for the latter, and the fact that the stucco band was applied over existing walls might support this argument (see Historical Evolution).14

The semantic complexities of the foundation inscription underscore how little we know about the Emamzadeh Yahya’s actual construction, both the tomb individually and the complex as a whole. These mysteries are compounded by limited surviving evidence and the destruction of other parts of the complex.

III.

Hadith

حدیث

قال النبی عَلیه الصّلوة و السّلام من اولی رجلا من بنی عَبدالمطلب وَ لم یقدرُ ان یکافیه فی الدنیَا کافاه الله تعالی یوم القیامه صدَق رسُول الله

Translation: The Prophet, peace and blessings be upon him, said: ‘Whoever bestows [a favor] upon a man from the descendants of Abd al-Muttalib [the Prophet’s grandfather] and [that man] is unable to repay him in this world, Allah the Almighty will repay him on the Day of Resurrection.’ The Messenger of Allah has spoken the truth.

The commonly recorded version of this hadith differs slightly from the one inscribed in the Emamzadeh Yahya.15 While the latter mentions a general favor granted to a descendant of ʿAbd al-Muttalib without specifying the nature of the favor, the former explicitly mentions a ‘known favor’ (معروفاً) granted in this world. Additionally, the inscription in the tomb states that Allah will reward the benefactor on the Day of Resurrection, whereas the common version specifies that the Prophet Mohammad will personally recompense him.

Inscribing this hadith immediately after the foundation inscription evokes the analogy of constructing the shrine for Yahya b. ʿAli as performing a favor for a descendant of ʿAbd al-Muttalib. The patron Malek Fakhr al-Din Hasan Hosayni Varamini passed away on 20 Shaʿban 707/22 February 1308, about six months after the date recorded on the west wall (Moharram 707/July–August 707), meaning he did not live to see the completion of his patronage. This hadith can therefore be interpreted as a testament to the divine reward awaiting him in the hereafter for this endowment. Additionally, it can be interpreted as a general call to make endowments to the shrine (or emamzadehs generally), with the assurance of divine compensation.

***

The stucco inscription in the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya is a unifying architectural feature of the interior, historical document about the building, sacred text on several levels, tactile zone of ziyarat, record of the tomb’s continuous use, and reminder of the plunder of its luster tiles. In recent decades, it has also become the focus of modern preservation efforts. One of the latest initiatives began in 2021 and focused on cleaning the surface and stabilizing cracks through the injection of adhesive and restorative composite mortar into the fissures (fig. 28).16 While efforts to reinforce and protect the inscription are necessary, surface cleaning might raise questions about what is and is not preserved. As we have seen, the historical yadegari are themselves important textual sources that warrant preservation like other forms of historical evidence.

The photographs and filmed recitation presented here have sought to capture the inscription over time (1863 to 2024), across sensory modes (visual, audible, tactile), and between the frames of architectural history, pilgrimage, and preservation. Through its many layers, resonances, points of entrée, and even tensions, this single inscription speaks volumes for the Emamzadeh Yahya complex as a whole.

Citation: Keelan Overton and Hossein Nakhaei, “The Stucco Inscription in the Tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya: From Architectural Ornament to Historical Memory.” Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of a Living Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton, 33 Arches, 2024. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.

Citation: Ahmad Khamehyar, “Recitation of the Stucco Inscription in the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya.” Video in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton, 33 Arches, 2024. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.

Notes

Acknowledgements: We thank Ahmad Khamehyar and Hamid Abhari for traveling to Varamin in January 2024 and kindly recording the inscription in this important way. Thank you to Hamid Abhari and Fatemeh Gharib for sharing excellent photographs. Our analysis of the yadegari builds on Nazanin Shahidi Marnani’s foundational readings here.

- The inscription in question can also be called an epigraphic band or frieze. For an overview of the texts, languages, and styles of monumental epigraphy in Iran and Transoxiana, see Blair’s introduction in Monumental Epigraphy, 3–16. This monograph catalogs seventy-nine inscriptions from 810 to 1106. ↩

- Nakhaei, Masjed-e jāmeʿ-e Varāmīn, 111–12, 130, 165. ↩

- The process of leaving commemorative inscriptions at monuments has a long history in Iran. For the tenth-century Buyid inscriptions at Persepolis, for example, see Blair, Monumental Inscriptions, 13 and nos. 6–7, 34–37. ↩

- On the different ways to ‘read’ and experience Qurʾanic epigraphy, and its varied functions in buildings like the Dome of the Rock, see Edwards, “Text, Context, Architext.” ↩

- Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, “Akhbār-e dākheleh: Darbār-e homāyūn,” [3]; Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, Rasāʾel, 208. ↩

- Combe et al., Répertoire chronologique d'épigraphie arabe, 14: 14–15. ↩

- Ibid; Blair, “Architecture as a Source for Local History,” 220–21. ↩

- Ghouchani, “Barrasī-ye katībeh-ye ārāmgāh-e ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn,” 62. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Afshar, “Waqfnāmeh-ye seh dīh dar Kāshān,” 128; Ghouchani, “Barrasī-ye katībeh-ye ārāmgāh-e ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn,” 63. ↩

- Ghouchani, “Barrasī-ye katībeh-ye ārāmgāh-e ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn,” 62. ↩

- A famous example of erasure is the replacement of Umayyad caliph ʿAbd al-Malik’s (r. 685–705) name with that of Abbasid caliph al-Maʾmun (r. 813–33) in the Dome of the Rock. See Milwright, The Dome of the Rock and Its Umayyad Mosaic Inscriptions, 35–36, fig. 1.13. On epigraphic erasures in Esfahan, see Overton, “Filming, Photographing and Purveying,” 346–48. ↩

- The foundation inscription of the congregational mosque in Varamin (dated 722/1322) also used the term العمارة, but the structure likely consisted of multiple components, and the term may therefore have referred to the entire complex, not just the mosque (specifically the south eyvan and domed chamber). See Nakhaei, Masjed-e jāmeʿ-e Varāmīn, 143–44. On the various parts of an Ilkhanid complex, see Blair, “Ilkhanid Architecture and Society: An Analysis of the Endowment Deed of the Rabʿ-i Rashīdī.” ↩

- In “Architecture as a Source for Local History” (p. 221, 224, 226), Blair uses the terms ‘renovation,’ ‘redecoration,’ and ‘reconstruction’ while discussing the evolution of the complex. Her conclusion likely stems from an earlier argument presented in her book The Ilkhanid Shrine Complex at Natanz (p. 17), where she suggests that the term العمارة was typically used in Ilkhanid Iran to refer to structures that were restored or rebuilt. ↩

- Ravandi and Ravandi, Ḍiyāʾ al-Shihāb, 2: 58, no. 355. ↩

- IRNA News Agency, “Maremmat va estehkām-bakhshī Ilkhānī Emāmzādeh Yahyā Varāmīn āghāz shod.” ↩

Bibliography

- اعتمادالسلطنه، محمدحسن خان. رسائل اعتمادالسلطنه. تدوین میرهاشم محدث. تهران: اطلاعات، ۱۳۹۱ش. [Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, Rasāʾel-e Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, The essays of Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, 1391 Sh/ 2012] [WorldCat] [Lib.ir]

- اعتمادالسلطنه، محمدحسن خان. «اخبار داخله: دربار همایون.» در: ایران، شمارهی ۳۰۵ (۷ ذیالحجه ۱۲۹۳ قمری): ۱-۳. سازمان اسناد و کتابخانه ملی ایران، ۱۰۱۴۵۷۴. [Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, Mohammad Hasan Khan. “Akhbār-e dākheleh: Darbār-e homāyūn.” Iran 305 (24 December 1876): 1–3. National Library and Archives of Iran, 1014574.]

- افشار، ایرج. «وقفنامۀ سه دیه در کاشان.» در: فرهنگ ایران زمین، شمارهی ۴ (۱۳۳۵ش): ۱۲۲- ۳۸. [Afshar, “Waqfnāmeh-ye seh dīh dar Kāshān,” “Waqfnameh of three villages in Kashan,” 1335 Sh/1956] [Noormags]

- خبرگزاری ایرنا. «مرمت و استحکامبخشی ایلخانی امامزاده یحیی ورامین آغاز شد.» ۳۰ فروردین ۱۴۰۰ش. [IRNA News Agency, “Maremmat va estehkām-bakhshī Ilkhānī Emāmzādeh Yahyā Varāmīn āghāz shod,” “Preservation and reinforcement of the Ilkhanid Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin has begun,” 30 Farvardin 1400 Sh/19 April 2021] [IRNA News Agency]

- راوندی، سعید بن هبة الله و ضیاءالدین فضلالله راوندی. ضیاء الشهاب و ضوء الشهاب فی شرح شهاب الأخبار. ج ۲. تحقیق عقیل الربیعی، کربلا: العتبه الحسینیه المقدسه، ۱۴۳۵ق. [Ravandi, Ḍiyāʾ al-Shihāb va Ḍawʾ al-Shahāb fī sharh-e Shahāb al-ʾakhbār, Ḍiyāʾ al-Shihāb and Ḍawʾ al-Shahāb in the commentary on Shahāb al-ʾakhbār, 1435/2014] [Internet Archive]

- قوچانی، عبدالله. «بررسی کتیبه آرامگاه علاءالدین.» در: اثر، شمارهی ۱۵-۱۶ (۱۳۶۷ش): ۵۹- ۷۱. [Ghouchani, “Barrasī-ye katībeh-ye ārāmgāh-e ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn,” “Study of the Inscription of ʿAlaoddin's Tomb,” 1367 Sh/1988–89]

- نخعی، حسین. مسجد جامع ورامین: بازشناسی روند شکلگیری و سیر تحول. تهران: دانشگاه شهید بهشتی و روزنه، ۱۳۹۷ش. [Nakhaei, Masjed-e jāmeʿ-e Varāmīn: Bāzshenāsī-ye ravand-e sheklgīrī va seyr-e taḥavvol, The Great Mosque of Varamin: The Process of Formation and Evolution, 1397 Sh/2019] [WorldCat] [Academia]

- Blair, Sheila. “Architecture as a Source for Local History in the Mongol Period: The Example of Warāmīn.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, special issue: The Mongols and Post-Mongol Asia: Studies in Honour of David O. Morgan, 3rd series, 26, 1–2 (2016): 215–29. [JSTOR]

- Blair, Sheila S. “Ilkhanid Architecture and Society: An Analysis of the Endowment Deed of the Rabʿ-i Rashīdī.” Iran 22 (1984): 67–90. [JSTOR]

- Blair, Sheila S. The Ilkhanid Shrine Complex at Natanz, Iran. Cambridge: Harvard University, 1986. [WorldCat]

- Blair, Sheila. The Monumental Inscriptions from Early Islamic Iran and Transoxiana. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1992. [Archnet]

- Combe, Étienne, Jean Sauvaget and Gaston Wiet (eds.). Répertoire chronologique d’épigraphie arabe, vol. 14. Cairo: Imprimerie de L’institut Francais d’archéologie orientale, 1954. [WorldCat]

- Edwards, Holly. “Text, Context, Architext: The Qurʾan as Architectural Inscription.” In Brocade of the Pen: The Art of Islamic Writing, edited by Carol Garrett Fisher, 63–75. East Lansing: Kresge Art Museum, Michigan State University, 1991. [WorldCat]

- Herzfeld, Ernst. Sketchbook, SK-II Persien. National Museum of Asian Art Archives, FS-FSA_A.6_02.01.02. [Ernst Herzfeld Papers]

- Milwright, Marcus. The Dome of the Rock and Its Umayyad Mosaic Inscriptions. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016. [WorldCat]

- Overton, Keelan. “Filming, Photographing and Purveying in ‘The New Iran:’ The Legacy of Stephen H. Nyman, ca. 1937–42.” In Arthur Upham Pope and a New Survey of Persian Art, edited by Yuka Kadoi, 327–70. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2016. [Academia]