A Luster Cabinet in Tehran, ca. 1880s, and Its Global Dispersal

Keelan Overton, with contributions by Mariam Rosser-Owen and Deniz Erduman-Çalış

Introduction

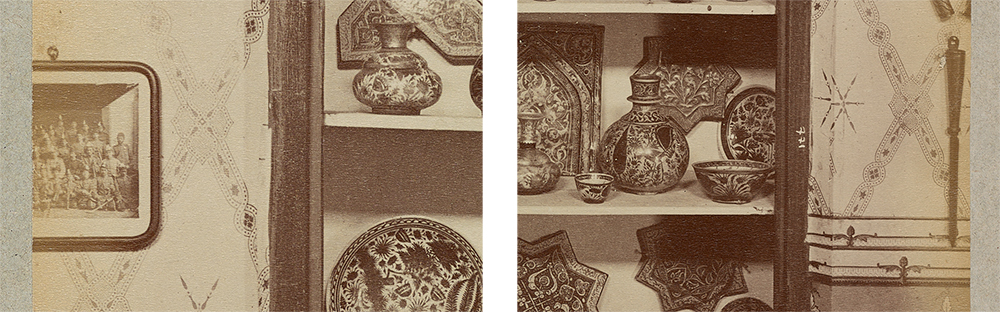

The Antoin Sevruguin photographs of Persia collection in the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles includes a rare photograph of luster ceramics on display in Tehran. Captioned “Cachis persans (Téhéran)” (“cachis” for kashi, کاشی, or tiles), the subject is a tall cabinet with five shelves packed with four types of luster: medieval tiles of the type generally attributed to Kashan, ca. 1200–1350; Safavid (1501–1722) vessels with metal fittings; contemporary Qajar (1789–1925) tiles, some imitating earlier models; and large dishes made in Spain around 1400 and then often referred to as ‘Hispano-Moresque.’ Altogether, the cabinet presents a global history of luster from Spain to Iran over seven centuries and into the present moment of the photograph.

Of relevance to this project on the Emamzadeh Yahya are the three large stars and two large crosses that are immediately recognizable as the type commonly attributed to the tomb (fig. 1). That the tomb’s tiles would have ended up in the capital just a few hours to the north makes sense given what we know about the Emamzadeh Yahya’s history in the 1870s and 1880s. During the first half of 1875, Robert Murdoch Smith (d. 1900), the Tehran-based agent for the South Kensington Museum, negotiated the acquisition of over 2,000 works of Persian art, including tiles attributed to the Emamzadeh Yahya, from Frenchman Jules Richard (d. 1891) (Handling Session). Richard had lived in Iran since 1844 and moved in court circles as a photographer, translator, professor at the Dar al-Fonun (founded in 1851), and well-known collector. Smith helped Richard pack up his collection in his Tehran house, a “tedious operation” (no. 17, July 9, 1875), and 62 cases combining Richard’s materials with additional tiles purchased from Louise Jean-Baptiste Nicolas (d. 1875), commissioner at the French Legation, were soon sent south to Bushire and from there by steamer to London via the Suez canal (V&A Archives, Smith reports nos. 9–17) (Carey 2017, 102–5).

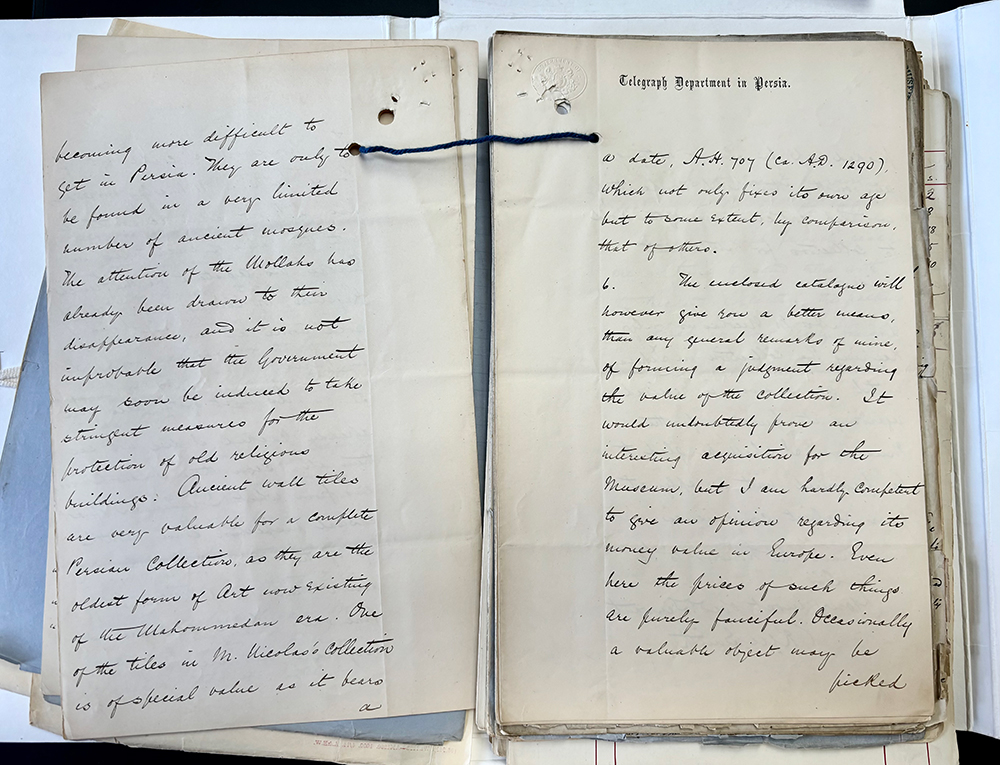

This first shipment was followed by another set of 52 tiles in November 1875 including some “sensitive acquisitions” (Carey 2017, 102). Iranian tilework was at such risk that Smith wrote the following in one of his reports to the museum (fig. 2):

Such tiles are now very rare and are every day becoming (see fig. 2, upper left) more difficult to get in Persia. They are only to be found in a very limited number of ancient mosques. The attention of the mollahs has already been drawn to their disappearance, and it is not improbable that the government may soon be induced to take stringent measures for the protection of old religious buildings. Ancient wall tiles are very valuable for a complete Persian collection, as they are the oldest form of art now existing of the Mahommedan era. One of the tiles in M. Nicolas’s collection is of special value as it bears a date, A.H. 707 (ca. A.D. 1290), which not only fixes its own age but to some extent, by comparison, that of others.

By the time of Jane Dieulafoy’s visit to the Emamzadeh Yahya in June 1881, Smith’s prediction—that shrines would be closed to foreigners—had apparently come true. In her January 1883 newspaper article, Dieulafoy describes how only a “royal order” allowed her to enter (p. 74). We can also remember that when he visited the Emamzadeh Yahya five years earlier in December 1876, Qajar official Mohammad Hasan Khan Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh (d. 1896) read two star tiles that had become dislodged from the wall. Like Dieulafoy, he praised the tomb’s luster tilework in a newspaper. This public praise of luster and the Emamzadeh Yahya specifically in both Tehran and Paris likely contributed to the collecting fervor that explains what we see in this densely-packed cabinet.

Bearing in mind this general context, we can now pose some questions: Who had the means to assemble this collection of Persian luster alongside two dishes from Spain? Where was this photograph taken and for what reason? Where are these objects now, and how did they get there? The answer to the first question is, yes, Jules Richard, but before addressing the collector, let us first consider the photograph.

The Photograph

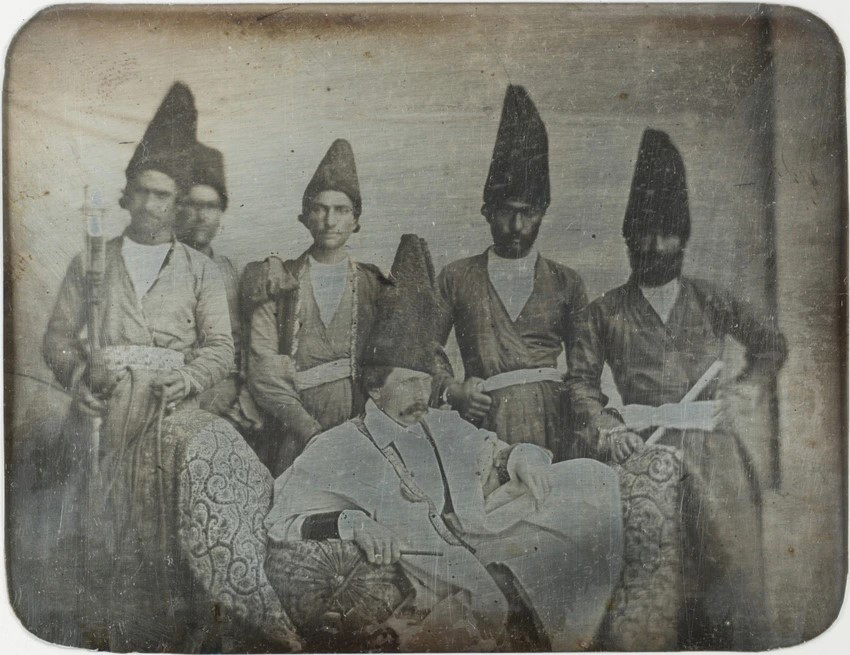

The photograph is a loose albumen print in a collection of 97 such prints, all attributed to the commercial photographer Antoine Sevruguin (d. 1933), or at least his studio or brand. In her article on the now disbound album, Sandra Williams suggests that its owner was probably a politically-connected European traveler in Iran and that it was likely compiled in the last decade of the nineteenth century, per the 1892 in one of the captions (Williams 2020, p. 30–32). Since the album is no longer intact, it is difficult to glean insight on its owner, but some photographs related to the Tobacco Régie, a notorious concession signed in March 1890 that awarded British Major G. F. Talbot the full monopoly over the production, sale, and export of tobacco for fifty years, suggest that this individual may have moved in these circles. A photograph taken in front of the Tehran headquarters of the Régie shows a number of Europeans identified by the captions on the right, presumably written by the owner (fig. 3; the ‘M. Nicolas’ is not the collector noted above).

The print is in excellent condition, and a high-resolution tiff from the Getty allows us to inspect its details closely (fig. 4). The far edge of the cabinet bears the negative number ‘771,’ which is consistent with images produced in or owned by Sevruguin’s studio (see Williams’ article for her points against single authorship). We cannot see much of the setting beyond the cabinet, but we can note the fine wallpaper, with a dado distinguished from the upper walls by a border, and various decorations mounted to the wall, including collectible arms and armor and a photograph of uniformed students in a military academy.

Had this photograph remained bound in its album, we would likely have a much better sense of how it did, or did not, relate to other images in the collection and why it was meaningful to the owner. Was this photograph taken by Sevruguin, or a member of his studio, with the album compiler present? In other words, did it commemorate a gathering of elites in this house? Or did the album owner just buy it from the studio given the generally appealing content (the luster)? Might the collector have enlisted the studio to photograph the cabinet and distribute prints for the purpose of generating sales? The previous photograph in the current numbering system (2017.R.25-19) cannot be read at face value as directly related, but it could depict another interior in the same house. This salon is decorated with comparable wallpaper and decorated with almost exclusively European furniture and collectibles. If in the same house, and this is a big if, it is strong evidence in favor of the owner of the house being a European.

Research on this photograph remains ongoing, and we can hope that another print of negative 771 might come to light. As for the owner/compiler, we can suggest with confidence that this individual moved in the upper echelons of the Qajar court and related European circles. In addition to the Régie headquarters, the owner was interested in (and spent time in?) one of the finest properties in Shemiran in northern Tehran, the Bagh-e Malek (map), the home of Hajj Mohammad Kazem Malek al-Tojjar, the leading merchant of the day (see 2017.R.25-18).

The Collection

The cabinet mixes a variety of luster tiles and portable objects. In addition to the star and cross tiles from the Emamzadeh Yahya, there is the Qajar-period capital of a column presumably from a mihrab, a tile in the shape of an arch (no. 5), and four smaller stars (see fig. 1). The last measure about 20 centimeters and can be compared to many similar examples with a phoenix in slight relief in white and luster framed by a border of Qur’anic or poetic verses in white on blue (see this large panel in the V&A).

The vessels in the cabinet include coffee cups, vases, spittoons, bases of water pipes, bowls, and flatter dishes. Their designs include floral and vegetal patterns, inscriptions (Qur’anic verses and poetry), and depictions of peacocks, cranes, cockerels, and phoenixes. Some of the jars have detailed metal mounts added during the nineteenth century to spruce up the object before sale and likely mask areas of chipping and breakage. Given the lack of color in the photograph, the videos below provide a sense of the colors, tones, reflections, and textures of luster that made it so appealing to collectors.

Video 1. Safavid-period luster vessels on display in Sèvres – Manufacture et Musée nationaux. Sèvres. Video by Keelan Overton, 2024.

Video 2. Bottle, Safavid, 1650–1700, with brass mounts, 1800–75, V&A Museum, London, 2544-1876. Curator Fuchsia Hart rotates the bottle and then turns it over to show its accession number, highlighting how it also arrived in 1876, the same year as the first batch of luster tiles from the Emamzadeh Yahya (see the film in Handling Session). Video by Keelan Overton, 2024.

The Collector

(research in progress, coming soon)

Enter the Interactive Photograph

Many of these luster objects and tiles were produced in large quantities and are preserved in countless collections worldwide. As a result, identifying the exact object/tile requires time, teamwork, and sometimes just pure luck. To date, we have located five objects/tiles in their current museums (see map 1 for their global dispersal). In this first iteration of this ongoing collaborative feature, we present these five alongside the dishes whose presence in the cabinet in Tehran might pique significant interest but which have not yet been identified: the pair of luster chargers (no. 2).

Click on the numbers to explore the object/tile further. No. 2 is by Mariam Rosser-Owen. No. 5 is by Deniz Erduman-Çalış.

Annotated interactive of a Luster Cabinet in Tehran, ca. 1880s. Photograph by Antoin Sevruguin (d. 1933) or the Sevruguin studio, albumen print. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, 2017.R.25-20.

Map 1. Locations worldwide relevant to the luster cabinet, including the current museum homes of the objects. Google Map created by Keelan Overton, December 2024.

Practical resources:

- The Sevruguin photograph is available in high resolution Zoom on Getty primo. Once in the Rosetta window, on the far left, scroll down to 2017.R25-20, “Cachis persans (Téhéran).”

Sources:

- Carey, Moya. Persian Art: Collecting the Arts of Iran for the V&A. London: V&A Publishing, 2017. [WorldCat]

- Dieulafoy, Jane. “La Perse, La Chaldée et La Susiane,” Le tour du monde: Nouveau journal des voyages (January 1883): 1–80. [BnF Gallica]

- Mahdavi, Shireen. “RISHĀR KHAN.” Encyclopædia Iranica, September 24, 2010, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/rishar-khan.

- Overton, Keelan “Jane Dieulafoy in Varamin: The Emamzadeh Yahya through a Nineteenth-Century Lens.” Getty Research Journal 19 (spring 2024): 61–95. [Getty]

- V&A Museum Archive, MA/1/S2325, Nominal file for Robert Murdoch Smith

- Wallis, Henry. Illustrated Catalogue of Specimens of Persian and Arab art Exhibited in 1885. London: Burlington Fine Arts Club, 1885. [Google Books]

- Williams, Sandra. “Reading an ‘Album’ from Qajar Iran.” Getty Research Journal 12 (2020): 29–48. [MUSE]

Acknowledgements: Thank you to Deniz Erduman-Çalış, Fuchsia Hart, Yui Kanda, Hossein Nakhaei, and Mariam Rosser-Owen for participating in this collaborative detective hunt. I am also grateful to Frances Terpak and Moira Day for facilitating research of the GRI collection over the years. Finally, thanks to Abbas Akbari, Mansoureh Azadvari, and Reza Sheikh for their insights on some details in the photograph.

Citation: Keelan Overton, “A Luster Cabinet in Tehran, ca. 1880s, and Its Global Dispersal.” The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.