An Introduction to the Origins and Construction of Emamzadehs in Iran, with an Emphasis on the Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin

Ahmad Khamehyar

Translated from Persian by Shahrad Shahvand

About Emamzadehs in Iran

In a lexicographical sense, ‘emamzadeh’ (امامزاده, pl. امامزادگان, emamzadegan) refers to the ‘descendant of an Emam’ (زادهی امام), specifically someone who is an offspring of one of the Twelve Infallible Emams, according to Emami Shiʿi beliefs.1 However, in contemporary usage among the people of Iran, the term ‘emamzadeh’ has expanded beyond its original definition and is now commonly used to refer to shrines or sites of pilgrimage associated with the children and grandchildren of the Shiʿi Emams.2

Before the Safavid period (1501–1722), numerous pilgrimage sites in Iran were dedicated to Sufi shaykhs, Sunni scholars, and religious figures, as well as the graves of governors and rulers. At the same time, in several cities and regions across the country, there were also tombs and pilgrimage sites belonging to ʿAlavi Sadats (سادات علوی), the progeny of the first Shiʿi Emam ʿAli and the Prophet Mohammad [ʿAlavi refers to Emam ʿAli; the phrase ‘ʿAlavi Seyyeds’ is henceforth used]. During the Safavid era, which marked the official establishment of Twelver Shiʿism, many of these pilgrimage sites, previously associated with Sufis, Sunnis, and sometimes rulers, were re-designated as emamzadehs—shrines of individuals considered to be direct descendants of the Twelve Emams. Even prior to the Safavid period, some tombs of ʿAlavi Seyyeds, whose genealogies traced back to the Shiʿi Emams through multiple intermediaries, were sometimes identified as the direct descendants of the Emams. This reassociation occurred because the general populace often lacked the ability to accurately trace and verify the full genealogies of these Seyyeds, leading them to omit the intermediaries and link the lineage directly to an Infallible Emam.

Given that the majority of pilgrimage sites in Iran were attributed to descendants of Emams during the Safavid period, the term emamzadeh gradually became synonymous with ziyaratgah (زیارتگاه, place of pilgrimage). As a result, the prefix emamzadeh was added to many pilgrimage sites that were neither the burial places of Emamzadehs nor ʿAlavi Seyyeds, but rather belonged to other revered figures such as Sufi pirs and babas (Sufi shaykhs), or even pre-Islamic prophets. Consequently, one can now encounter pilgrimage sites referred to with titles like ‘Emamzadeh Saleh, the Prophet’ and ‘Emamzadeh Baba Ruzbahan.’

It is said that there are currently around ten thousand pilgrimage sites in Iran, with the majority of these sites recognized as emamzadehs. However, it is important to note that not all of these emamzadehs can be assumed to be the burial places of the children or descendants of the Shiʿi Emams. From a historical perspective, it is not possible to conclusively establish that these sites belong to the direct descendants of the Emams or even to other ʿAlavi Seyyeds. In fact, as mentioned earlier, a portion of the pilgrimage sites in Iran attributed to Emamzadehs originally belonged to Sufis, rulers, or other revered Sunni figures and were only later associated with Emamzadehs during the Safavid period. Additionally, some of these sites were formerly sacred places (such as Mithraic worship centers, Zoroastrian fire temples, caves, springs, and sacred trees) which, either before or during the Safavid era, were transformed into emamzadehs and Islamic pilgrimage sites.

In addition to these points, it is important to note the emergence of completely new pilgrimage sites without any historical precedent during the Safavid period and even up to the contemporary era. Some of these sites were established after the fact as tombs or graves of religious scholars and notable figures, while others came into existence based on dreams or night visions experienced by local individuals. Despite these developments, historical and material evidence show that there were significant examples of tombs and pilgrimage sites dedicated to Emamzadehs and ʿAlavi Seyyeds in periods predating the Safavids. In fact, the origins of some of these sites can be traced back to the early Islamic period (seventh century). Notably, several of these emamzadehs were tombs of ʿAlavi Seyyeds whose graves, shortly after their death, quickly became focal points of veneration and pilgrimage (fig. 1).

The History of the Arrival of ʿAlavi Seyyeds in Iran

The arrival of the ʿAlavi Seyyeds in Iran can be traced back to the second/eighth century. It is believed that the first ʿAlavis to enter Iran were some of the Zaydi Emams who rebelled against the ruling caliphs of their time. Among the earliest was Yahya b. Zayd b. Zayn al-ʿAbidin, the grandson of the fourth Shiʿi Emam, who, after passing through the lands of what is now modern-day Iran, led a rebellion against the Umayyad Caliph Walid II, son of Yazid b. ʿAbd al-Malek (r. 125–126/743–44), in Greater Khorasan. He was eventually killed in 125/742–43 in the city of Jowzjan (now Sar-e Pol in northern Afghanistan).3 Following him, Yahya b. ʿAbdollah Mahz, the son of Hasan b. Hasan, the second Shiʿi Emam, fled and sought refuge in the mountainous region of Daylam (now part of Gilan Province in northern Iran) during the reign of the Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid (r. 170–93/786–809). However, Yahya was eventually captured and killed in Harun’s prison in the city of Rafeqah (now Raqqa in northern Syria).

In the year 200/815–16, Maʾmun (r. 198–218/813–33), the son of Harun al-Rashid, decided to appoint ʿAli b. Musa al-Reza, the eighth Shiʿi Emam, as his heir apparent [Emam al-Reza’s lineage traces back to Emam ʿAli and Fatemeh al-Zahra, the daughter of the Prophet Mohammad, through five intermediaries]. In 201/817, after traveling through the lands of Iran, Emam Reza arrived in the ancient city of Merv (in present-day southern Turkmenistan). There, the people pledged allegiance to him as Maʾmun’s heir apparent, and coins were even minted in his name. However, shortly thereafter, in 203/818, Emam al-Reza passed away in the city of Tus (map).4 Since ancient times, Emami Shiʿis have held the belief that Emam al-Reza was murdered by Maʾmun through the administration of poisoned grapes (see cat. no. 40) and that his appointment as heir apparent was politically motivated by the Abbasid caliph. Today, the largest and most famous sacred site in Iran is the Holy Shrine of Emam Reza (Haram-e Emam Reza) in the city of Mashhad, located near the ruins of the historic city of Tus (fig. 2).5

In his Tārīkh-e Qom (تاریخ قم, History of Qom), written in the fourth/tenth century, Hasan b. Mohammad Qomi reports that after the announcement of Emam Reza’s appointment as heir apparent, his sister Fatemeh, the daughter of Emam Musa Kazem, set out for Iran with the intention of joining her brother. Along the way, in the city of Saveh (southwest of present-day Tehran), she fell ill. As a result, she altered her route towards the city of Qom, where one of the largest early Shiʿi communities had by then formed. Seventeen days after arriving in Qom, she passed away.6 Today, the shrine of this revered lady, Fatemeh bt. Musa b. Jaʿfar, known by the epithet ‘Maʿsumeh,’ is one of the most important pilgrimage sites for Shiʿis in Iran, second only to the Shrine of Emam Reza (fig. 3).7 The presence of this sacred shrine in the city of Qom has played an indisputable role in the establishment of one of the largest seminaries of Emami Shiʿism in modern times.

Since the third/ninth century, ʿAlavi Seyyeds have migrated extensively to various cities in Iran. The city of Qom, which witnessed an early expansion of Emami Shiʿism, became one of the most significant destinations for ʿAlavi Seyyeds. In his Tārīkh-e Qom, Hasan b. Mohammad Qomi provides a detailed account of the emigration of ʿAlavi Seyyeds to the city and its surrounding areas. Additionally, by referring to the Muntaqilat al-Ṭālibīyah (منتقلة الطالبیة, Settlements of the Talibi [Tribe]) written by the ʿAlavi Seyyed Ebn-e Tabataba (d. fifth/eleventh century), one can observe that other cities, such as Esfahan, Rey, Neyshabur, and some coastal cities along the Caspian Sea and the adjacent mountainous regions, namely Tabaristan and Daylaman (present-day provinces of Mazandaran and Gilan), also experienced extensive ʿAlavi Seyyed migrations from the third/ninth to fifth/eleventh centuries.

In the mid-third/ninth century, some Zaydi ʿAlavis succeeded in establishing an ʿAlavi state in Tabaristan. During the same period, other ʿAlavis in different parts of Iran began to rebel against the Abbasid caliphs. Typically, these rebellions ended in defeat, and their leaders were killed. Abu al-Faraj (Abolfaraj) Esfahani (d. 356/967), a prominent literary figure of the Abbasid era, documented most of these rebellions in his Maqātil al-Ṭālibīyīn (مقاتل الطالبیّین, The Battles of the Talibiyin).

The Formation of Emamzadehs in Iran

Following the establishment of the Seljuk dynasty by Sultan Toghrel I (r. 429–55/1037–63), the construction of tombs, mausoleums, and other commemorative structures became increasingly common in Iran. In regions where Shiʿis resided, tombs were often built for the descendants of the Emams and for ʿAlavi Seyyeds. Many of these tombs were commissioned by Shiʿi statesmen who had risen to administrative or governmental positions within the Seljuk state.

In his Ketab-e Naqż (کتاب نقض, The Book of Refutation), ʿAbd al-Jalil Qazvini Razi, an Emami writer of the sixth/twelfth century, records the construction of the following tombs during the early decades of Seljuk rule: the shrine (مشهد) of Fatemeh bt. Musa b. Jaʿfar in Qom, commissioned by Amir Abu al-Fazl ʿEraqi during the reign of Sultan Toghrel I; the shrine of ʿAbd al-ʿAzim (ʿAbdol-ʿAzim) Hasani in Rey, commissioned by Majd al-Molk Baravestani Qomi (murdered in 492/1099); the shrine of ‘Emamzadeh’ ʿAli b. Emam Mohammad Baqer in Barkarsaf (present-day village of Ardahal, near Kashan), commissioned by Majd al-Din Kashi; the shrine of ʿAbdollah b. Emam Musa Kazem in the village of Ojan near Saveh, commissioned by Safi al-Din Abu al-Mahasin Hamadani; and the shrines of two Emamzadehs, Fazl and Soleyman, sons of Emam Musa Kazem, in the Shiʿi-inhabited city of Aveh, located between Saveh and Qom.8

Most of these buildings, including the tombs (مزار) of Fatemeh Maʿsumeh in Qom, ʿAbdol-ʿAzim Hasani in Rey, and ʿAli b. Emam Mohammad Baqer in Ardahal, have undergone significant development over time and, due to extensive construction in their surrounding areas, have been transformed into large religious complexes and pilgrimage sites. However, a few pilgrimage sites, such as the Emamzadeh ʿAbdollah in Ojan near Saveh (map), have preserved their original Seljuk-era structures (fig. 4). In the case of the Emamzadeh Fazl and Soleyman in nearby Aveh (map), only a single eyvan (vaulted space open on one side) was added to the Seljuk-era structure during the Safavid period (fig. 5).

From a historical perspective, there are doubts about whether some of these Emamzadehs—including ʿAli b. Emam Mohammad Baqer and the Emamzadehs of Aveh and Saveh (believed to be the sons of Emam Musa Kazem)—actually migrated to Iran and were buried in the locations where their tombs were later constructed. Hence, there is insufficient historical evidence to confirm the authenticity of these emamzadehs. It appears, however, that several other emamzadehs constructed during the Seljuk and Ilkhanid periods to commemorate direct descendants of the Twelve Emams were, in fact, the burial places of ʿAlavi Seyyeds who lived in these regions. Some of these individuals were later identified as direct descendants of the Shiʿi Emams.

The majority of emamzadehs are usually found in the central cities of Iran, where Shiʿism spread more extensively and residents were particularly devoted to preserving and honoring the tombs of the ʿAlavi Seyyeds who once lived there. The pilgrimage site of Emamzadeh ʿAbdollah in the village of Kudzar, located forty kilometers south of the city of Arak (map), is a rare and remarkable example of an emamzadeh whose entire interior is adorned with a layer of Seljuk-era stuccowork, much of which has been preserved to this day (fig. 6).

In the city of Qom, there are several emamzadehs in the form of hexagonal brick buildings with conical domes.9 Some of these structures were built in the second half of the eighth/fourteenth century by the emirs of Khandan-e Safi, a local Shiʿi family that ruled over Qom, and their interiors are adorned with intricate brick designs and stuccowork (figs. 7–8).10 The most well-known among them is the Emamzadeh ʿAli b. Jaʿfar, attributed to one of the sons of Jaʿfar-e Sadiq, the sixth Shiʿi Emam. Its mihrab and tombstone are considered some of the finest examples of luster tilework produced in the eighth/fourteenth century.

During this period, the well-known Abu Taher Kashi family and other craftsmen, such as Hasan b. ʿAli b. Ahmad Babewayh Vidgoli (also known as Bidgoli), were engaged in producing luster tilework and stucco mihrabs. Commissioned by the builders of these tombs, they created mihrabs and tombstones [parts of cenotaphs] for these emamzadehs, particularly in cities like Mashhad, Qom, Kashan, Varamin, and other locations that were important pilgrimage sites for the Shiʿis.11

The History of the Emamzadeh Yahya Complex

During the seventh/thirteenth and the first half of the eighth/fourteenth centuries, under the rule of the Ilkhanid dynasty in Iran, a local ʿAlavi Seyyed family from the city of Varamin governed the two cities of Rey and Varamin for nearly a century, acting as representatives of the Ilkhanid rulers.12 Although historical sources provide limited and scattered information about this family, the available evidence suggests that they made significant efforts to contribute to the architectural landscape within their domain, particularly in Varamin and Rey.13

A massive brick funerary tower (borj) in Varamin, the Borj-e ʿAlaoddoleh (map), modeled after an older tower known as the Borj-e Toghrel in the city of Rey, stands as a testament to the reign of this family. This tomb serves as the burial place of one of the rulers of the family, ʿAlaoddin Morteza (ʿAlaʾ al-Din, d. 675/1276–77). It was constructed during the reign of his son, Malek Fakhroddin Hasan II (Fakhr al-Din, d. 707/1308) and likely commissioned by him (fig. 9). According to Abdullah Ghouchani’s reading of the Kufic inscription at the top of the building’s exterior, the tomb’s construction was completed in 688/1289–90.14

Another prominent building constructed (or reconstructed) during the reign of the ʿAlavi rulers of Rey and Varamin in their place of origin, the city of Varamin, is the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya. This tomb is regarded as one of the significant architectural works of the Ilkhanid period remaining in central Iran and is notable for its rich stuccowork, intricate brickwork, and luster tiles (fig. 10). All of the luster tiles, including those covering the mihrab and cenotaph, as well as the star and cross-shaped tiles that once adorned the dado, were removed from their original locations and transferred abroad. The mihrab, considered among the finest examples of luster tilework from the Ilkhanid era, is now in the Shangri La Museum of Islamic Art, Culture & Design in Honolulu, while the tombstone of the cenotaph is in the State Hermitage Museum (see Blair’s essay).15

In the stucco inscription written in thuluth (sols) script around the interior of the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya (listen to my recitation here), the name ‘Hasan b. Morteza b. Hasan b. Mohammad b. Hasan b. Abi Zayd’ can be observed (this is the same previously mentioned Malek Fakhroddin Hasan II ʿAlavi) (fig. 11). This inscription is dated Moharram 707/July–August 1307, just a few months before the passing of Fakhroddin Hasan, who, according to Ilkhanid-era historian Abu al-Qasem Kashani, died in the month of Shaʿban of the same year (February 1308).16 The luster tombstone of the emamzadeh is dated 10 Moharram 705/2 August 1305, also corresponding to the reign of Malek Fakhroddin Hasan II. The other luster tiles associated with this building are dated between 660–63/1262–65, during the rule of Malek ʿAlaoddin Morteza.

The Notable Figure Buried in the Emamzadeh Yahya

One of the most important sources for understanding the lineage and identity of figures buried in Iranian emamzadehs are books of Seyyed genealogies. These sources often provide abundant information about the descendants of the Shiʿi Emams, including their children, grandchildren, and later generations, as well as the cities to which these Seyyeds migrated and where their descendants resided. Additionally, they offer valuable insights into the political, social, and scholarly status of the ʿAlavi Seyyeds, sometimes even recording the date and place of their death and burial.

In Seyyed genealogical sources, an ʿAlavi Seyyed named Yahya b. ʿAli b. ʿAbd al-Rahman ʿAlavi is mentioned whose lineage traces back to Emam Hasan-e Mojtaba, the second Shiʿi Emam and son of Emam ʿAli, through five intermediaries. He was killed in Varamin during the reign of al-Mohtadi Bellah (r. 255–56/869–70), the fourteenth Abbasid caliph. Historical evidence indicates that the Emamzadeh Yahya was constructed as a tomb for this particular individual.

The earliest historical account of this individual comes from the aforementioned Abu al-Faraj Esfahani (d. 356/967), who mentions Yahya b. ʿAli b. ʿAbd al-Rahman b. Qasem b. Hasan b. Zayd [b. Hasan b. ʿAli b. Abi Taleb] among the ʿAlavis executed during the caliphate of the Abbasid Mohtadi. He states that Yahya was killed in a village near Rey by the agents of ʿAbdollah b. ʿAziz, the governor of Rey.17

Another historical account comes from the aforementioned Ebn-e Tabataba ʿAlavi (fifth/eleventh century), who records the murder of Yahya b. ʿAli b. ʿAbd al-Rahman in Varamin.18 The significance of this account lies in the fact that it specifically identifies the location of Yahya’s murder as Varamin, rather than Rey. Considering that Varamin was one of the dependencies of Rey in the early centuries of the Islamic calendar, this account does not conflict with Abu al-Faraj’s earlier report.

Moreover, Abu al-Hasan ʿOmari ʿAlavi (d. 466/1073–74) mentions the incident of Yahya’s murder during the reign of the Abbasid caliph al-Mohtadi and notes the existence of his grave in the vicinity of Rey.19 Similarly, Ebn-e Fondoq-e Beyhaqi (d. 565/1169–70), writing about the same individual, states that he was killed by the agents of ʿAbdollah b. ʿAziz in one of the villages of Rey, where his grave is located.20

In the Sirr al-silsilah al-ʿAlawīyah (سر السلسلة العلویة, The Secret of the ʿAlawi Lineage), one of the earliest genealogical sources attributed to Abu Nasr Bokhari (d. 357/967–68), a person named ʿAli b. ʿAbd al-Rahman is mentioned as being murdered during the time of ʿAbdollah b. ʿAziz, under the caliphate of al-Mohtadi. The same report adds that his mashhad (pilgrimage site) in Varamin is visible and standing.21 Interestingly, the individual identified as being murdered is not Yahya, but his father ʿAli. This discrepancy may be attributed to omissions in the text or scribal errors made by the copyist of the manuscript. There are also doubts surrounding the attribution of the Sirr al-silsilah al-ʿAlawīyah to Abu Nasr Bokhari.22 In any event, the significance of this account lies in the fact that it provides early evidence of the existence of a pilgrimage site in Varamin.

The aforementioned historical reports sufficiently suggest that the Emamzadeh Yahya of Varamin is indeed the burial site of Yahya b. ʿAli b. ʿAbd al-Rahman b. Qasem b. Hasan b. Zayd b. [Emam] Hasan b. [Emam] ʿAli b. Abi Taleb. It is noteworthy, however, that the luster tiled tombstone associated with the Emamzadeh Yahya makes no mention of his lineage, referring to him only as ‘Emam-e ʿalem, Yahya’ (امامِ عالِم یحیی, the knowledgeable Emam, Yahya). In this inscription, Emamzadeh Yahya is assigned two significant scholarly titles: emam and ʿalem. The term ʿalem (meaning scholar in Persian) was used for individuals recognized for their expertise and mastery in one of the branches of knowledge, typically in religious sciences. While the term emam originally referred to the Shiʿi Emams and the founders of legal and theological schools, it later came to be applied more generally to scholars who were leading authorities in their field—those considered at the pinnacle of scholarly achievement in their time. As a result, prominent figures such as Emam Mohammad Ghazali and Emam Fakhr Razi became widely known by the honorific emam.23

Given that most luster tiled tombstones placed on the graves of Emamzadehs in Iran reference their lineage, the absence of such a reference on the tombstone associated with the Emamzadeh Yahya leaves room for the assumption that, at the time of its construction (or reconstruction) during the Ilkhanid period, the people of Varamin, or perhaps the builder of the tomb, were unaware of the Emamzadeh’s lineage.24 Even if they were aware, no evidence of this is visible in the artistic remnants from that period. In fact, we have no evidence to determine what the populace of Varamin or the patrons of the Emamzadeh Yahya thought about the individual buried there, or his lineage, at the time of construction. However, given that this figure is mentioned in historical sources and his lineage, persona, and tomb are frequently referenced in genealogical sources, one can reasonably assume that the patrons of the tomb were likely aware of who he was.

Another piece of evidence that supports this claim is a wooden door from the Safavid period, completed in Safar 971/October 1563. Unfortunately, this door is no longer in its original location, and its fate is unknown (see cat. no. 15). Fortunately, in Shaʿban 1279/January 1863, Qajar prince ʿAliqoli Mirza Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh (d. 1298/1880) recorded the door’s inscription, which included Emamzadeh Yahya’s lineage, and appended this transcription to a biography of the saint based on genealogical sources (see Textual Source).25 In the door’s inscription, the lineage of the Emamzadeh is given as follows: Yahya b. ʿAli b. ʿAbd al-Rahman b. Qasem b. Hasan b. Zayd b. Hasan b. ʿAli b. Abi Taleb. This evidence indicates that there was continuity, rather than a historical break, in the knowledge of the people of Varamin, and by extension the creators of this wooden door, about the lineage of Emamzadeh Yahya.

During the Qajar era (1779–1925), it appears that the lineage of Emamzadeh Yahya, like that of many other Emamzadehs in Iran, had been forgotten by the local populace, and alternative accounts about the figure buried there began circulating. Contemporary sources provide two versions of common local perceptions of Emamzadeh Yahya’s lineage. One account, reported by Qajar courtier Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh ([Mohammad Hasan Khan], d. 1313/1896), states that this Emamzadeh was believed to be Yahya b. Emam Musa Kazem.26 Another account associates the same Emamzadeh with Yahya b. Zayd b. Emam Zayn al-ʿAbidin.27 Clearly, from a historical perspective, neither of these accounts contains any factual basis.28 In reality, Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh’s treatise of Emamzadeh Yahya should be seen as an attempt to clarify the historical identity of the Emamzadeh and his lineage based on genealogical sources. It is likely that, after reading the inscription on the Safavid wooden door, Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh became aware of the true lineage of the Emamzadeh. By writing this biography, he sought to correct the prevailing misconceptions of his time, which mistakenly identified Emamzadeh Yahya as a son of Emam Musa Kazem.

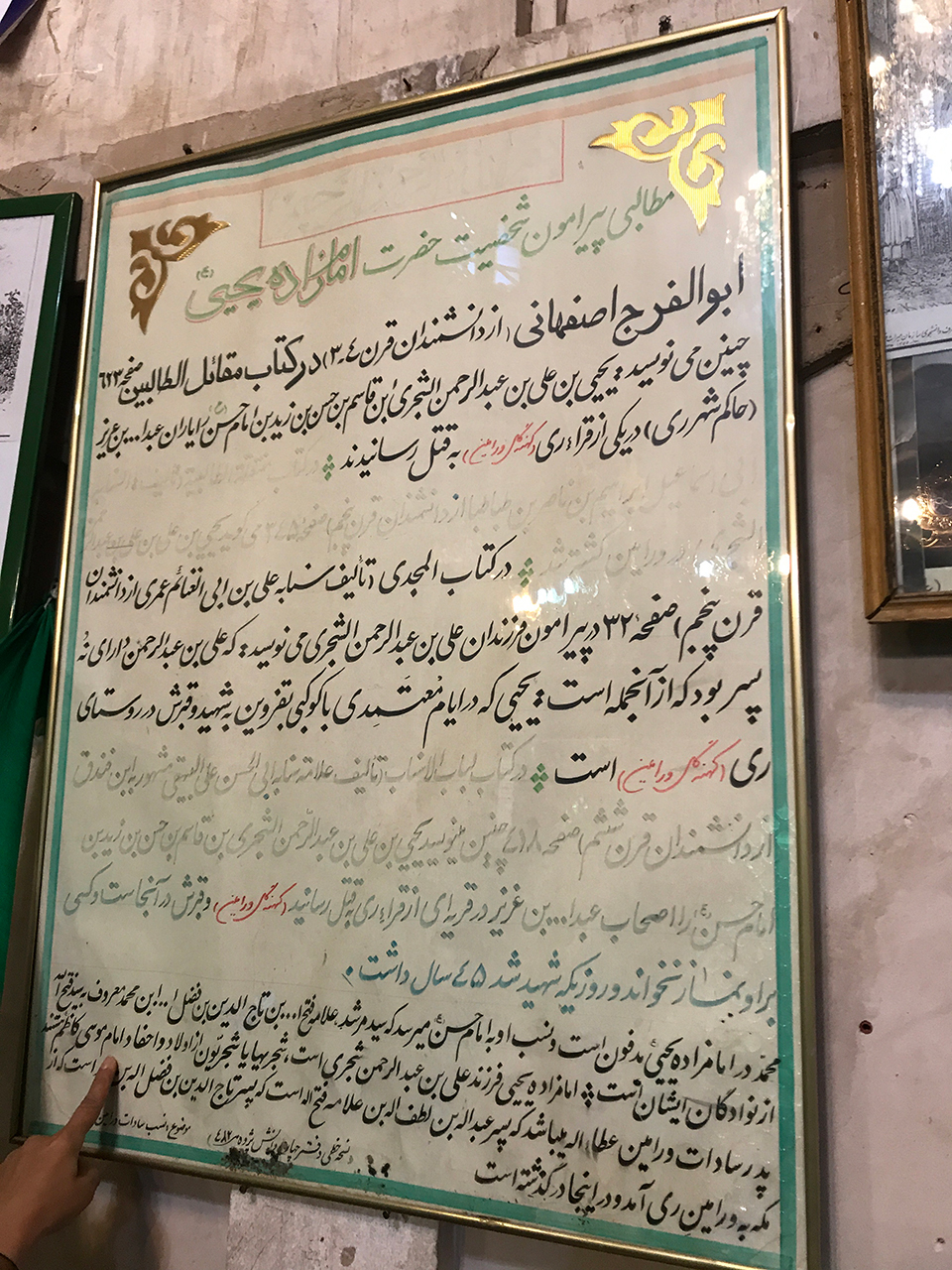

In recent decades, several other Iranian scholars, including Seyyed Safar Rajabi, Hossein Qarachanloo, and Mohammad Mahdi Faqih Jalali Bahrololum, have emphasized the same viewpoint [regarding Emamzadeh Yahya’s lineage].29 Based on the research done to date, this viewpoint has been accepted by the Endowment Organization and reflected in the informational signs displayed in the Emamzadeh Yahya. A large sign summarizing Emamzadeh Yahya’s biography based on historical and genealogical sources was previously displayed in the mihrab space (fig. 12).

***

Unlike many other emamzadehs that lack sufficient historical credibility, the Emamzadeh Yahya in the city of Varamin is an example of a site that, based on multiple historical sources, can be confidently identified as the burial place of an ʿAlavi Seyyed from the early Islamic centuries. Textual evidence, including genealogical sources written between the fourth/tenth and sixth/twelfth centuries, confirms the existence of the tomb of Yahya b. ʿAli in Varamin, although no material evidence from that period remains today. What is now recognized as the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya is part of a larger and more refined complex that was built or rebuilt during the Ilkhanid period, when Varamin emerged as the political center of Rey province under the patronage of the ruling ʿAlavi family.

The only mention of the individual buried in the tomb appears in the decoration, where the phrase ‘emam-e ʿalem Yahya’ (the knowledgeable Emam, Yahya) is inscribed on the luster tombstone dated 705/1305. This inscription offers little insight into how the tomb’s patrons and builders, as well as the people of Varamin during the Ilkhanid era, perceived Yahya b. ʿAli. However, the tomb once featured a wooden door from the Safavid period inscribed with Emamzadeh Yahya’s lineage, as derived from pre-Ilkhanid textual evidence. Taken together, this body of evidence supports the possibility of many centuries of historical continuity in the local knowledge of the true identity and lineage of the Emamzadeh.

By the Qajar period, evidence suggests that the people of Varamin had forgotten Emamzadeh Yahya’s lineage, and in some cases, his tomb was mistakenly attributed to Yahya b. Zayd b. Emam Zayn al-ʿAbidin or Yahya b. Emam Musa Kazem. In the late Qajar period, Prince ʿAliqoli Mirza Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh challenged these misattributions after consulting genealogical sources and reading the inscription from the now lost wooden door of the emamzadeh. This not only underscores the importance of genealogical knowledge for figures like Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh, who belonged to the nobility, but also highlights the extensive access individuals like him had to genealogical records. Moreover, the inscription on the stolen wooden door, whose current whereabouts are unknown, underscores the importance of material culture as a crucial form of evidence for preserving and transmitting the historical memory of these buildings.

Citation: Ahmad Khamehyar, “An Introduction to the Origins and Construction of Emamzadehs in Iran, with an Emphasis on the Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin,” translated by Shahrad Shahvand. Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.

Notes

Editor’s note (Overton): This is a literal translation of the author’s original essay in Persian. The provided translation has been copyedited, and in some instances, sentences have been reordered and language simplified to improve clarity and flow in English. Some additional glosses, definitions, and links have also been added to help the English reader. Throughout this translation, Emamzadeh refers to an individual (like Emam or Seyyed), whereas emamzadeh refers to a tomb.

Acknowledgments: I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Hossein Nakhaei and Keelan Overton for carefully reviewing the article, providing valuable comments and suggestions, and assisting me in editing and finalizing the manuscript. I would also like to thank Hoda Nedaeifar for editing the essay.

- On the Emams and Infallible Ones, according to the belief of the Emami Shiʿis, see Algar, “Čahārdah Maʿsūm.” ↩

- Also see Lambton, “Imāmzāda.” ↩

- Abu al-Faraj Esfahani, Maqātil al-Ṭālibīyīn, 145–50. The pilgrimage site of Yahya b. Zayd is located in this city. ↩

- See Madelung, “ʿAlī Al-Reżā.” ↩

- On the city of Mashhad, see Streck, “Mas̲h̲had.” ↩

- Qomi, Tārīkh-e Qom, 308–9. ↩

- On Hazrat-e Maʿsumeh and her shrine, see Modarresi Tabatabai, Torbat-i pākān, volume 1. On the city of Qom, see Calmard, “Ḳum.” ↩

- Qazvini Razi, Kitāb-i Naqż, 214–15 and 236–37. ↩

- A conical dome (gonbad-e rok) is a type of dome shaped like a pyramid or cone. The tomb tower located in Gonbad-e Qabus is one of the oldest examples of this type of dome in Iran. This architectural style was frequently used in tomb towers during the Seljuk and Ilkhanid periods. ↩

- For a report on these buildings, see Arab, “Gozāresh-e taḥqīq va moʿarrefī-e haft banā-ye tārīkhī va ārzeshmand-e Qom,” 146–63. ↩

- On the Abu Taher family, see Watson, “Abū Ṭāher.” On Hasan b. ʿAli b. Ahmad Babewayh Vidgoli and his works, see Blair, “Stucco Workers, Luster Potters.” ↩

- On Varamin, see Bosworth, “Warāmīn.” ↩

- On this family, see Khamehyar, “Molūk-e shiʿeh-ye Rey va Varāmīn dar dowreh-ye Ilkhānī,” 433–38. Although historical sources limit the domain of this family’s rule to Rey and Varamin, genealogical sources suggest that their domain was more extensive, likely including other cities such as Qom and Kashan. See Khamehyar, “Āgāhī-haye dīgarī darbāreh-ye molūk-i ʿAlavī-ye Rey dar dowreh-ye Ilkhānī.” ↩

- Ghouchani, “Barresī-ye katībeh-ye Ārāmgāh-e ʿAlāʾ al-dīn,” 62–63. ↩

- On the construction and architecture of the Emamzadeh Yahya, see Blair, “Architecture as a Source;” Overton and Maleki, “The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin.” ↩

- Abu al-Qasem Kashani, Tārīkh-e Oljāytū, 75. ↩

- Abu al-Faraj Esfahani, Maqātil al-Ṭālibīyīn, 530. ↩

- Ebn-e Tabataba, Muntaqilat al-Ṭālibīyah, 345. ↩

- ʿOmari ʿAlavi, al-Majdī fī ansāb al-ṭālebīyīn, 216. ↩

- Beyhaqi, Lubāb al-ansāb wa-al-alqāb wa-al-aʿqāb, 1: 418. ↩

- Bokhari, Sirr al-silsilah al-ʿAlawīyah, 22. ↩

- Ansari, “Doshvāreh-ye Ketāb al-Shajarah.” ↩

- On the term ‘emam,’ see Majmuʿat min al-muʾallefin, Muʿjam muṣṭalaḥāt al-ʿulūm al-sharʿīyah, 1: 251–52. ↩

- Including the tombstones of Emamzadeh Jaʿfar [b. Musa], Emamzadeh ʿAli b. Jaʿfar, and Emamzadeh Hares b. Ahmad (Khakfaraj) in Qom. For the inscriptions of these tombstones, see Modarresi Tabatabai, Torbat-e Pākān, 2: 38, 48, 84. ↩

- Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh, “Sharḥ-e ḥālāt-e Emāmzādeh Yaḥyā,” 55–56. Two extant manuscripts of this treatise are preserved in Tehran: one in the Majles Library (the original, dated Moharram 1294/January 1877, no. 26/1453 SS) and the other in the Malek Library (a copy, no. 6151/059). ↩

- Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, Rasāʾel-e Eʿtemād al-Salṭaneh, 208. ↩

- Faqih Mohammadi Jalali, Qiyām-e Yahya b. Zayd, 307–8. ↩

- As mentioned in the main text of this article, Yahya b. Zayd was killed in 125/742–43 in Jowzjan (present-day Sar-e Pol in Afghanistan), where his grave still stands today. ↩

- Rajabi, “Varāmīn: Yek jāmeʿ va chahār mazār-e tārīkhī,” 181; Qarachanloo, “Emāmzādeh Yaḥyā (Varāmīn),” 71; Faqih Mohammadi Jalali, Qiyām-e Yahya b. Zayd, 307–13. ↩

Bibliography (Persian and Arabic)

- ابن طباطبا، ابراهیم بن ناصر. منتقلة الطالبیة، تحقیق السید محمد مهدی الخرسان. النجف الاشرف: المطبعة الحیدریة، ۱۳۸۸ق. [WorldCat]

- ابوالفرج اصفهانی، علی بن الحسین. مقاتل الطالبیّین، تحقیق السید احمد صقر. بیروت: مؤسسة الاعلمی للمطبوعات، ۱۹۸۷م. [ویرایش متفاوت WorldCat]

- اعتضاد السلطنه، علیقلی میرزا. «شرح حالات امامزاده یحیی.» در: جنگ نظم و نثر، نسخهی دستنویس در کتابخانهی مجلس شورای اسلامی در تهران، شمارهی ۲۶/۱۴۵۳سس. [Lib.ir]

- اعتمادالسلطنه، محمدحسن خان. رسائل اعتمادالسلطنه، تصحیحِ میر هاشم محدّث. تهران: اطلاعات، ۱۳۹۱ش. [Lib.ir]

- انصاری، حسن. «دشوارهی کتاب الشجرة المبارکة منسوب به فخر رازی: بررسی احتمالات گوناگون.» در: بررسیهای تاریخی، ۲ آبان ۱۳۸۶ش.، https://ansari.kateban.com/post/1219

- بخاری، ابونصر سهل بن عبدالله. سر السلسلة العلویة، تحقیق السید محمدصادق بحرالعلوم. النجف الاشرف: المکتبة الحیدریة ومطبعتها، ۱۳۸۲ق. [WorldCat]

- بیهقی، علی بن زید. لباب الأنساب والألقاب والأعقاب، تحقیق السید مهدی الرجائی، ۲ جلد. قم: مکتبة آیة الله العظمی المرعشی النجفی الکبری، ۱۴۱۰ق. [WorldCat]

- خامهیار، احمد. «ملوک شیعهی ری و ورامین در دورهی ایلخانی.» در: کتابگزار، شمارهی ۱ (۱۳۹۵ش.): ۳۴۸-۴۳۳. [Noormags]

- خامهیار، احمد. «آگاهیهای دیگری دربارهی ملوک علوی ری در دورهی ایلخانی.» در: گنجینه، ۲۸ مهر ۱۳۹۷ش. [Ganjineh.kateban]

- رجبی، سید صفر. «ورامین: یک جامع و چهار مزار تاریخی.» در: مشکوة، شمارهی ۳۵ (۱۳۷۱ش.): ۱۷۶-۱۸۵. [Noormags]

- عرب، کاظم. «گزارش تحقیق و معرفی هفت بنای تاریخی و ارزشمند قم، بازمانده از قرن هشتم هجری.» در: اثر، شمارهی ۳۳-۳۴ (۱۳۸۱ش.): ۱۴۶-۱۶۳. [Tebyan.net]

- عمری علوی، علی بن محمد. المجدی فی أنساب الطالبیّین، تحقیق احمد المهدوی الدامغانی. قم: مکتبة آیة الله العظمی المرعشی النجفی العامة، ۱۴۲۲ق. [Internet Archive]

- فقیه محمدی جلالی (بحرالعلوم)، محمد مهدی. قیام یحیی بن زید (ع). قم: وثوق، ۱۳۸۵ش. [Lib.ir]

- قرهچانلو، حسین. «امامزاده یحیی (ورامین).» در: وقف میراث جاویدان ۱، شمارهی ۲ (۱۳۷۲ش.): ۷۰-۷۳. [Noormags]

- قزوینی رازی، عبدالجلیل. بعض مثالب النواصب فی نقض بعض نواقض الروافض (کتاب نقض)، تصحیح میر جلالالدین محدّث ارموی، به کوشش محمدحسین درایتی. قم: مؤسسهی علمی فرهنگی دار الحدیث، تهران: کتابخانه و مرکز اسناد مجلس شورای اسلامی، ۱۳۹۱ش.

- قمی، حسن بن محمد بن حسن. تاريخ قم، مترجم: حسن بن محمد بن حسن بن عبدالملك قمی، تصحيح واحد تحقيق آستانه مقدسه قم. قم: زائر، ۱۳۸۸ش. [ویرایش متفاوت Noorlib]

- قوچانی، عبدالله. «بررسی کتیبهی آرامگاه علاءالدین.» در: اثر۱۵-۱۶(۱۳۶۷ش.): ۵۹-۷۱.

- کاشانی، ابوالقاسم. تاریخ اولجایتو، به اهتمام مهین همبلی. تهران: بنگاه ترجمه و نشر کتاب، ۱۳۴۸ش. [Lib.ir]

- مجموعة من المؤلفین. معجم مصطلحات العلوم الشرعیة، ۴ جلد. ریاض: مدینة الملک عبدالعزیز للعلوم والتقنیة، جلد ۱، ۱۴۳۹ق.

- مدرسی طباطبایی، حسین. تربت پاکان (آثار و بناهای قدیم محدودهی کنونی دارالمؤمنین قم)، ۲ جلد. قم: انجمن آثار ملی، ۱۳۵۳ش. [Soha library]

Bibliography (English)

- Algar, Hamid. “Čahārdah Maʿsūm.” Encyclopædia Iranica, December 15, 1990, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/cahardah-masum.

- Blair, Sheila. “Stucco Workers, Luster Potters, and Builders: the Case of Hasan ibn Ali ibn Ahmad Babawayh al-Vidguli.” Essay pending in Stucco in the Architecture of Iran and Neighboring Countries: New Research – New Horizons, edited by Lorenz Korn.

- Blair, Sheila. “Architecture as a Source for Local History in the Mongol Period: The Example of Warāmīn.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 26, 1–2 (January 2016): 215–28.

- Bosworth, C. Edmund. “Warāmīn.” In Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, vol. 11, 143–44. Leiden: Brill, 2002.

[Internet Archive] [Brill] - Calmard, Jean. “Ḳum.” In Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, vol. 5, 369–72. Leiden: Brill, 1986.

[Internet Archive] [Brill] - Lambton, Ann K. S. “Imāmzāda.” In Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, vol. 3, 1169–70. Leiden: Brill, 1986.

[Internet Archive] [Brill] - Madelung, Wilferd. “ʿAlī Al-Reżā.” Encyclopædia Iranica, December 15, 1985 (updated 2011), https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/ali-al-reza.

- Overton, Keelan and Kimia Maleki. “The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: A Present History of a Living Shrine, 2018–20.” Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World 1 (2020): 120–49.

[Brill] - Streck, Mamara bihi. “Mas̲h̲had.” In Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, vol. 6, 713–16. Leiden: Brill, 1991.

[Internet Archive] [Brill] - Watson, Oliver. “Abū Ṭāher.” Encyclopædia Iranica, December 15, 1983 (updated 2011), https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/abu-taher-family-potters-kasan.