The History of Zarrinfam Pottery in Iran at a Glance

Abbas Akbari

On the Terms ‘Zarrinfam’ and ‘Luster’

Any introduction to the history of pottery in Iran requires an overview of luster (lustre), its different types, and related terminology. The terms that have been used to describe this technique in Persian and English are limited and have caused some confusion.

In Persian, the term zarrinfam (literally ‘golden color’) is used widely, but the pottery itself is not necessarily always golden. Sometimes it is red or brown, for example. The word is merely descriptive and does not illuminate the different methods of production. In his ʿArayes al-Javaher va Nafayes al-Atayib (Precious Minerals and Exquisite Fragrances) dated 700/1301, Abo'l Qasem ʿAbdollah Kashani (d. 1324), a notable member of Abu Taher Kashani family, described what is today known as zarrinfam or luster as leʿgheh-ye do-atasheh (enamel of two firings) or alat-e do-atasheh (pots of two firings).1 ‘Two firings’ refers to twice firing: the first one for the base glaze in an oxidation kiln (when oxygen is sufficiently present) and the second one for the luster decoration in a reduction kiln (when oxygen is reduced). It should be noted that although bisque firing (pre-firing without a glaze) and initial glazing were done simultaneously in some medieval ways of producing pottery, the bisque phase was not included in Abo'l Qasem’s text. Although his text referred to two firings, his wares were in fact fired three times, if we include the bisque phase.

In English-language ceramic literature, the pottery in question is commonly referred to as ‘lustre’ (British English and French spelling) or ‘luster’ (North American English spelling). This word can refer to all metal-like surfaces, including those that can be made in two kiln conditions, whether oxidation or reduction. Luster also indicates brilliance and brightness, qualities that can be found in many other examples of non-reflective metallic-glazed pottery, including all polychrome transparent glazes. In sum, we can observe that the term ‘luster’ is rather general and imprecise and offers no definitive picture of production.

The same can be said for the phrase ‘metallic ceramics,’ which refers to metallic reflection, one of the visual characteristics of luster pottery. Once again, the semantics do not illuminate the technique. Some types of metallic pottery are produced in an oxidizing kiln atmosphere, meaning oxygen is sufficiently present for firing the pots inside the kiln. By contrast, the primary technique of luster pottery—the clay paste method—requires reduction conditions. Reduction refers to a condition of firing at a lower temperature during which the potter produces a smoky atmosphere in the kiln in order to create a metallic surface on the pottery.2 The smoke is created by the addition of anything that can produce smoke. In a wood kiln, wood should be used (fig. 1). This process can be seen in my film “Kashi and Kashan” (8:51).

The Clay Paste Method

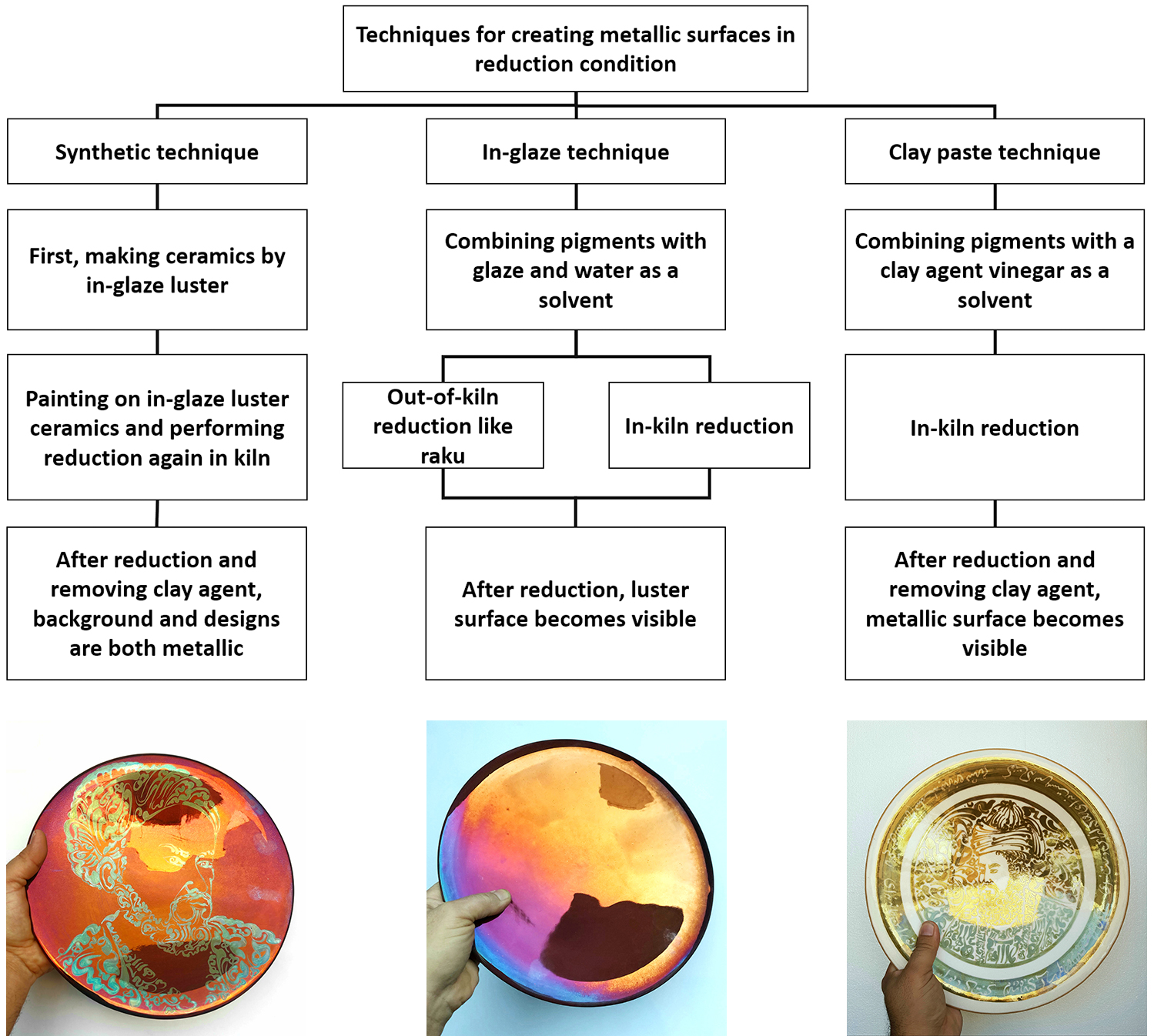

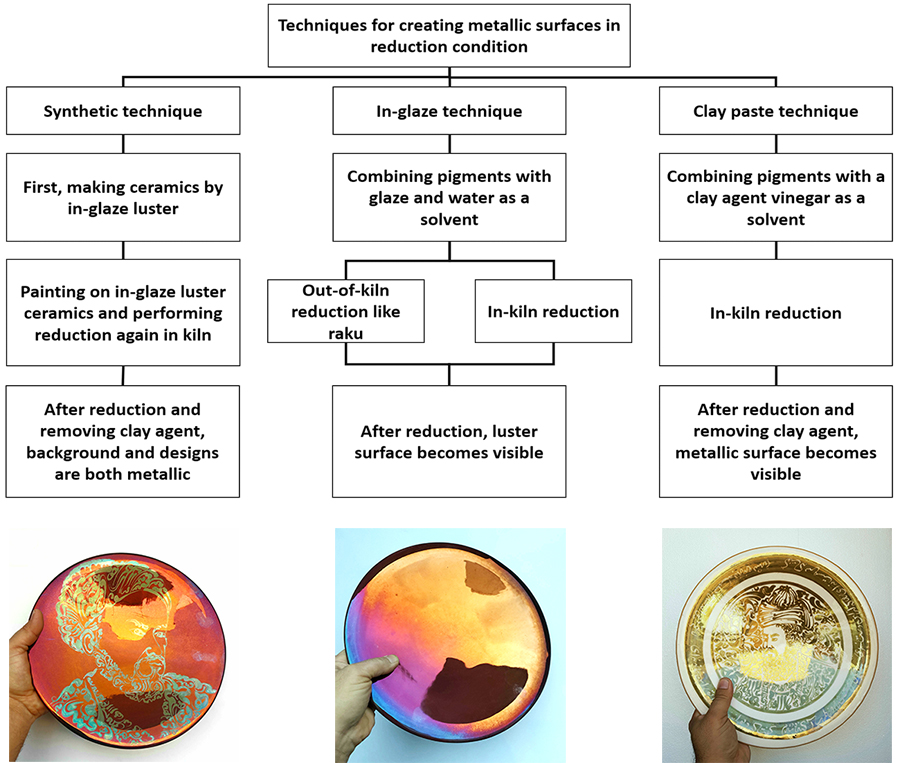

The table here shows the three types of luster pottery produced in reduction conditions, one of which is ‘clay paste’ (fig. 2, the photo on the right). The clay paste technique is a medieval technique of luster production and its origin is still debated. In this method, the combination of metal oxides (silver and copper) and salts is combined with a clay medium that is saturated with iron oxide and a solvent such as vinegar. The potter then paints with this composition on a ceramic body that has already been glazed and fired and fires it again in a low-temperature reduction kiln. After the kiln cools down, the potter removes the clay medium from the ceramic piece. If everything has gone well, a metallic surface, or luster, is obtained.

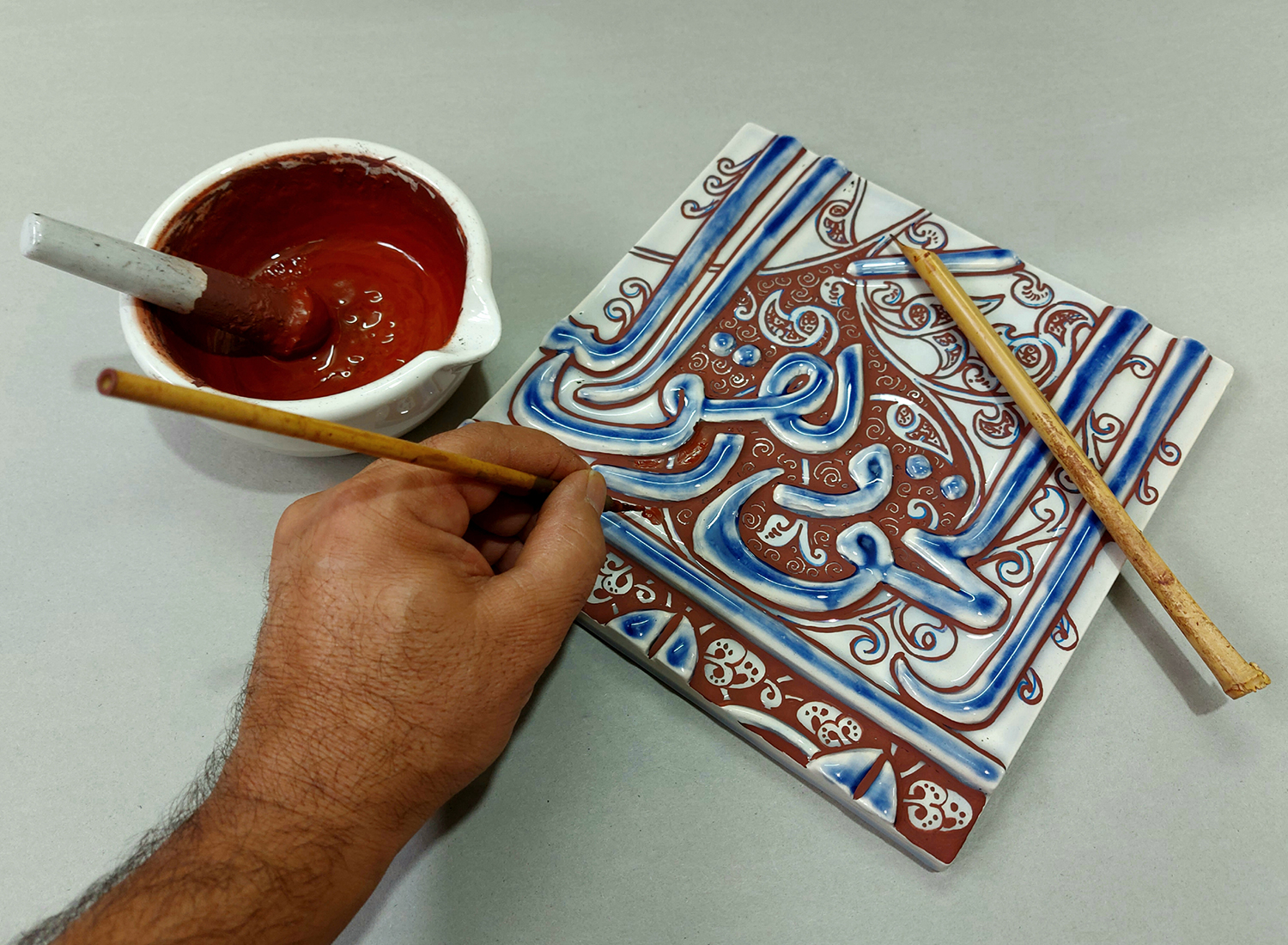

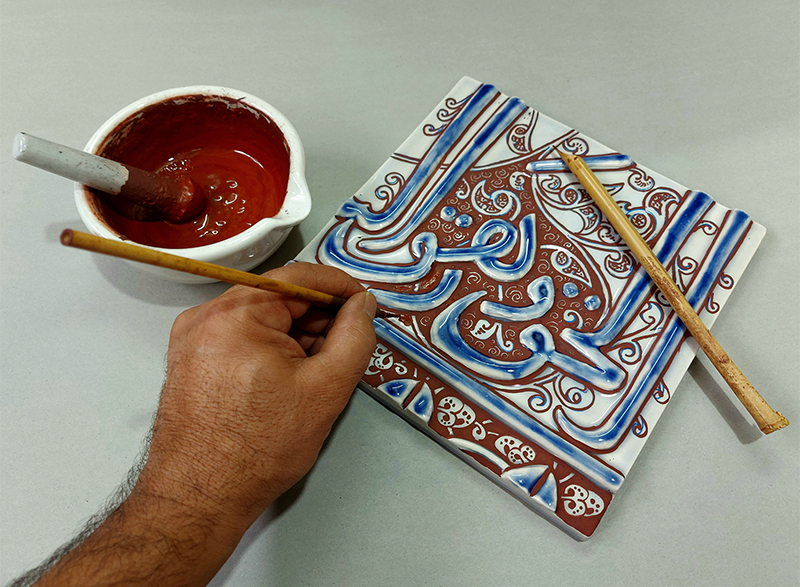

Perhaps the most important feature of the clay paste method of producing luster is its ability to allow one to draw both positive and negative delicate lines (fig. 3–5). In the positive technique, the potter uses a brush to paint with luster directly onto the ceramic body. In the negative technique, the potter uses a sharp-pointed piece of wood or a bamboo calligraphy pen to scratch out patterns in the passages of painted luster, revealing the white glaze beneath.

During the medieval period, Kashani potters produced some of the finest works with these delicate lines in the ‘miniature style,’ so called because they resembled miniature paintings on paper (see “The Art of the Book”) (fig. 6). The clay paste technique was also used to produce luster tiles, including the star and cross tiles attributed to the Emamzadeh Yahya (fig. 7, vid. 1).

Video 1. Details of the luster surface of the Wereldmuseum star tile, WM-66085, including positive and negative lines. Video (silent) by Keelan Overton, September 2022.

It is because of this unique characteristic—its delicate lines—that the clay paste technique has been distinguished from other methods of luster and its place of invention has always been debated. Two points should be emphasized: first, the clay paste method appeared around the ninth century, and second, it was not possible to produce this method without knowing the conditions of the reduction kiln.

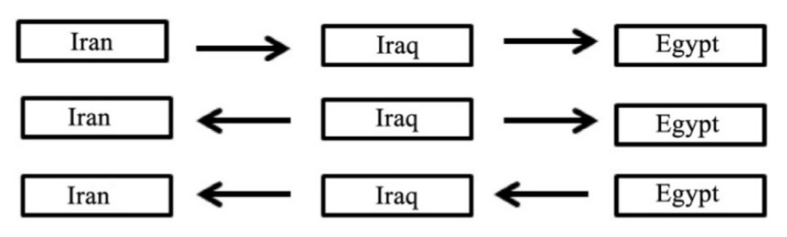

On the Origin of Luster Pottery and the Importance of Iran

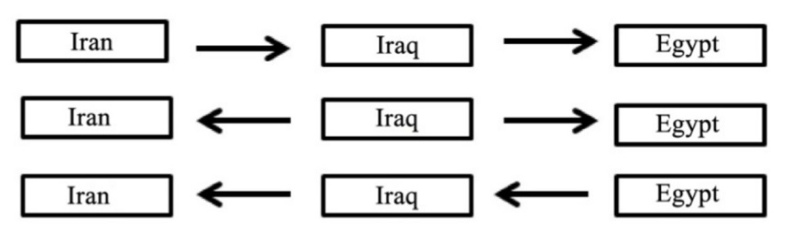

The advent of luster pottery was one of the great turning points in the history of ceramics.3 Iran has always been considered one of the possible places of origin, but Iraq and Egypt have also been proposed. The following chart illustrates Iran’s position in the controversy and the development of the technique according to three camps:

These conflicting theories are based on the following four hypotheses, none of which are irrefutable and some of which are contradictory:

- The transfer of the luster technique from glass to pottery in eighth-century Egypt.4

- The oldest known luster tiles, dateable between 856 and 863. These are in the Kairouan mosque in Tunis (map) and were imported from Baghdad.5 The oldest surviving examples of luster pottery are attributed to ninth-century Basra (fig. 9).

- The migration of potters from Fustat to Rey around the eleventh century.6

- The possibility of multiple production centers in Iran, including Kashan (see my film “Where is Kashan?”), Rey, Saveh, Gorgan, and Neyshabur.7

Supporters of the first hypothesis consider Egypt as the birthplace of the technique (on glass) and then attribute its transfer to pottery in Iraq. Others, like Egyptian researcher Zaki Mohamad Hassan, argue that Iran should be considered the birthplace of luster pottery because of its many production centers (Kashan, Rey, Saveh, Gorgan, and Neyshabur). In Egypt and Iraq, production was limited to one city each: Cairo and Basra.

A New Hypothesis: The Discovery of Materials and Iranian Scientists in Abbasid Iraq

It is impossible to resolve this debate without considering another possible hypothesis based on a different form of evidence. I would like to propose that the discovery of certain chemical compositions is closely related to the earliest productions of luster pottery.

The key material in question is silver nitrate. The discovery of this compound (nitrat-e noghreh), as well as several other combinations of silver, is attributed to Mohammad ibn Zakaria Razi (d. 925), an Iranian physician, philosopher, and alchemist known for discovering alcohol and authoring many texts, including the Kitab al-Asrar. Razi was born in Rey (map), the city just south of modern Tehran that would later host Egyptian immigrants seeking new markets (see the third hypothesis above).8 Razi went to Baghdad in 283/896, decades before this likely migration. During his ten years of residency in Iraq, he made chemicals necessary for pottery as well as many other medical discoveries.9 Razi’s presence in Iraq at the same time as the production of luster pottery is an important point to consider in the origin of luster pottery. Moreover, the role of Iranian scientists in the history of luster pottery is not limited to Razi. Jaber ibn Hayyan (d. 815), another Iranian scientist and resident of Iraq who wrote a treatise on glass and luster on glass, also deserves mention.10

It is necessary to remember that today’s political borders are not the same as those of the ninth century, when Iran, Iraq, and Syria were governed by a single Islamic government: the Abbasids. This discussion therefore does not embrace nationalistic prejudices defined by today’s geographical borders. It should be remembered that Jaber ibn Hayyan and Zakaria Razi, despite being called ‘Iranian’ according to today’s borders, did their scientific work related to luster within the borders of modern-day Iraq.

Importance of Persian Sources for the Production of Luster Pottery

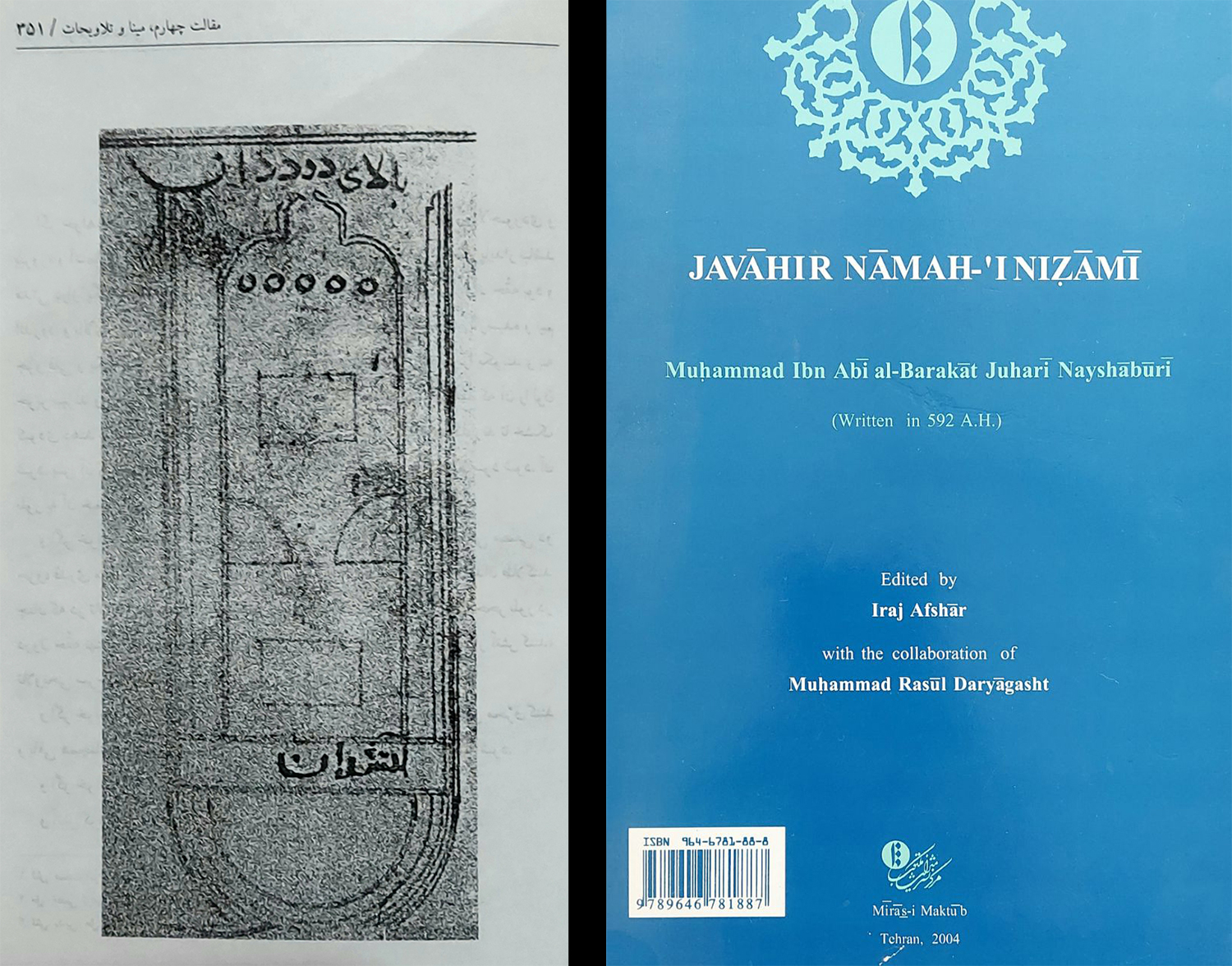

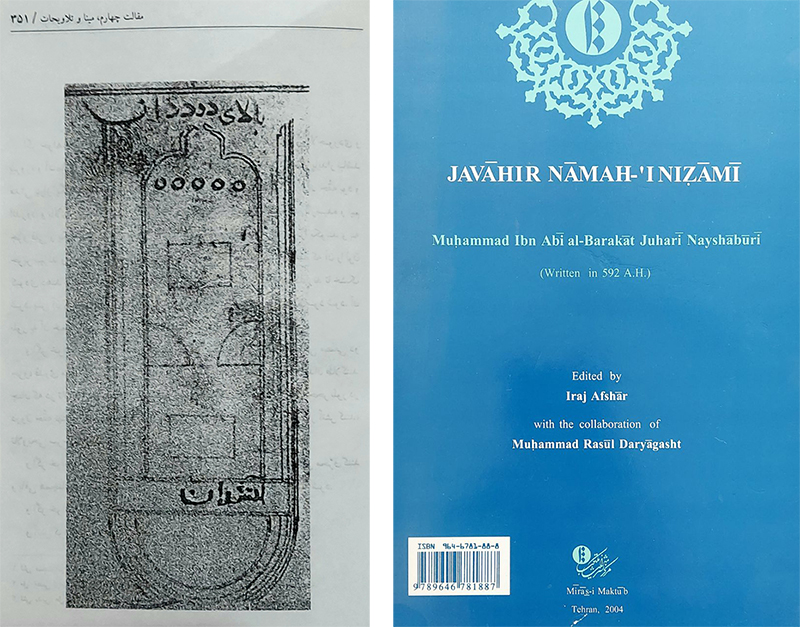

Two important Persian texts that recorded the secrets of luster strongly support the role that Iran played in the history of production. These sources are the Javahernameh-ye Nezami (The Book on Mineralogy of Nezami) written by Mohammad ibn al-Barakat Jowhari Neyshaburi and the aforementioned ʿArayes al-Javaher va Nafayes al-Atayeb of Abo'l Qasem Kashani.11 A manuscript of the Javahernameh-ye Nezami dated 592/1196 and preserved in the Malek Library includes an illustration of a special reduction kiln called a ‘dud-dan’ (literally, the place of smoke) (fig. 10). In his ʿArayes al-Javaher, Abo'l Qasem describes his family’s recipes and how other potters of the time made different recipes by adding more or less ingredients. Both authors only explain the making of luster according to the clay paste technique.

A third older source is also known: the Kitab al-Durra al-Maknuna (The Book of the Hidden Pearl) by the aforementioned Iranian scientist based in Iraq, Jaber ibn Hayyan (d. 815). The Kitab al-Durra technically explains how to make luster on glass and introduces different recipes. It is yet another reminder of the contribution of Iranians in promoting this technique.

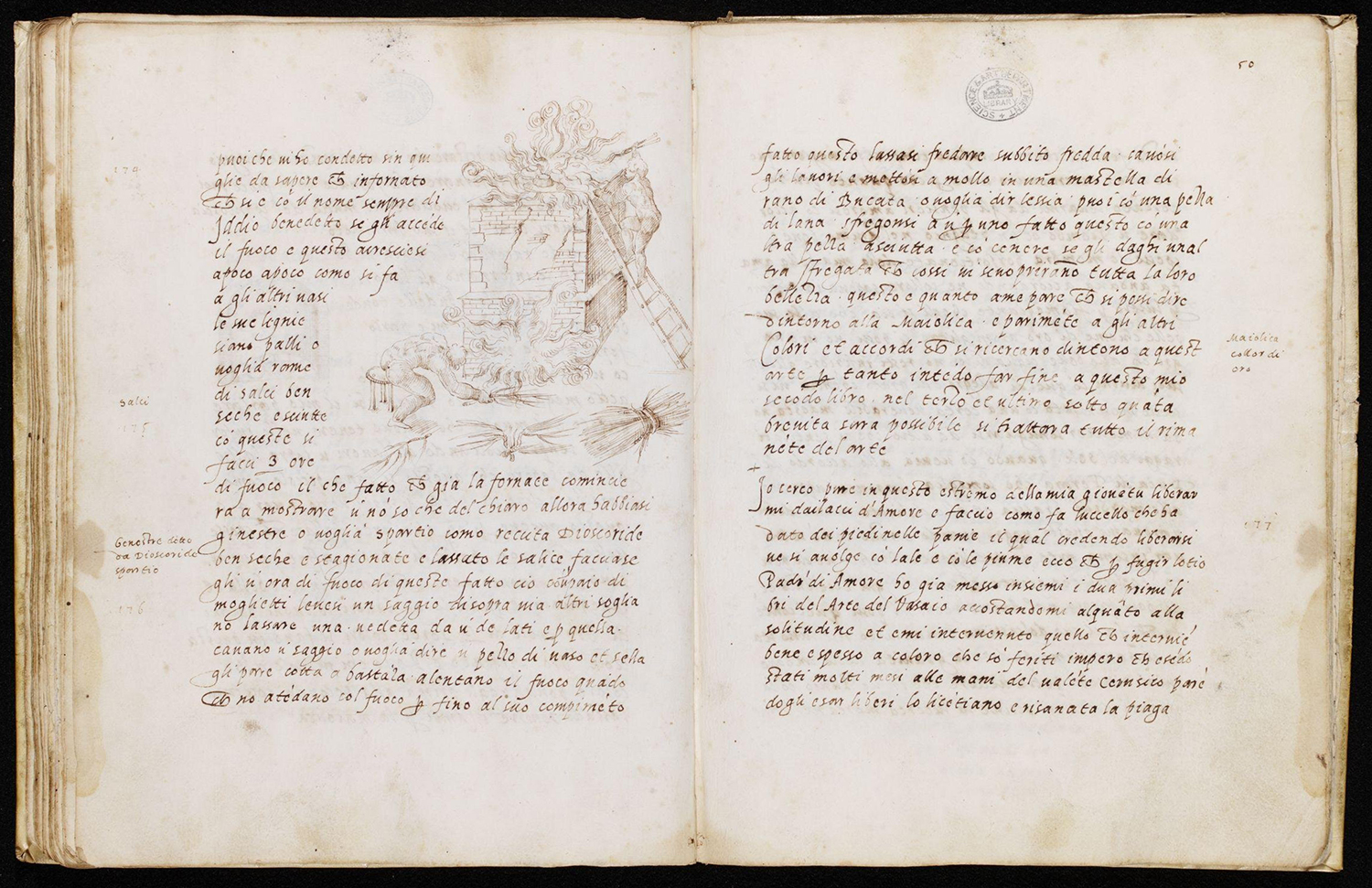

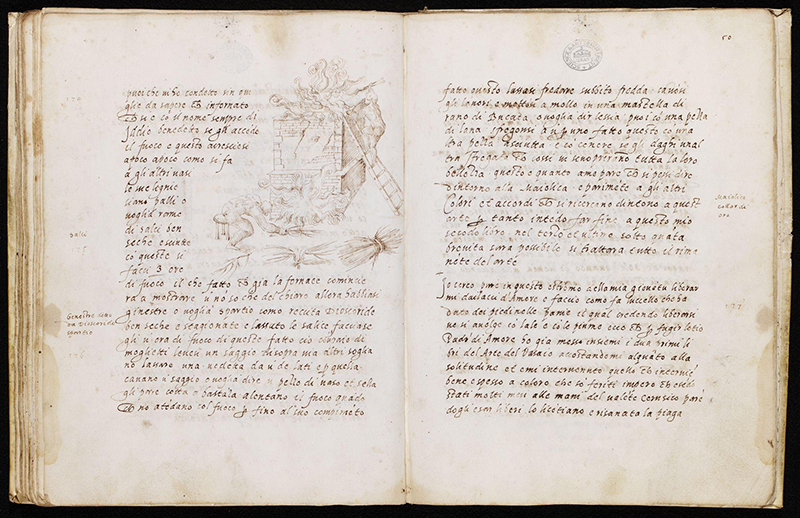

An important non-Persian source is the sixteenth-century treatise of Italian engineer-architect Cipriano Piccolpasso (d. 1579) entitled Li tre libri dell'arte del vasaio (The three books of the potter’s art). A manuscript of this text produced around 1557 and preserved in the V&A Museum illustrates the steps of making many types of pottery, including luster. The drawings in the luster section show the reduction kiln and clocking the reduction time with a sandglass (fig. 11).

Importance of the Continuation of Luster Pottery Production in Iran

Until a few decades ago, and before the development of today’s mass media, it was believed that the production of luster ceramics had disappeared in most historical centers and that knowledge of the technique was limited to only a few people worldwide. This assumption prevailed before the publication of Alan Caiger-Smith’s Lustre Pottery in 1985. It was also widely believed that the last examples of luster pottery in Iran belonged to the Qajar period (1789–1925). Many lusterwares were produced at this time, but most of them lacked signatures. A notable exception is the well-known potter Ali Mohammad Esfahani, who knew the technique well and was active for about a decade around 1880. Examples of his signed and attributed works are preserved in several museums. Most are in the underglaze technique (for example), but one is luster in an Ilkhanid style (fig. 12).

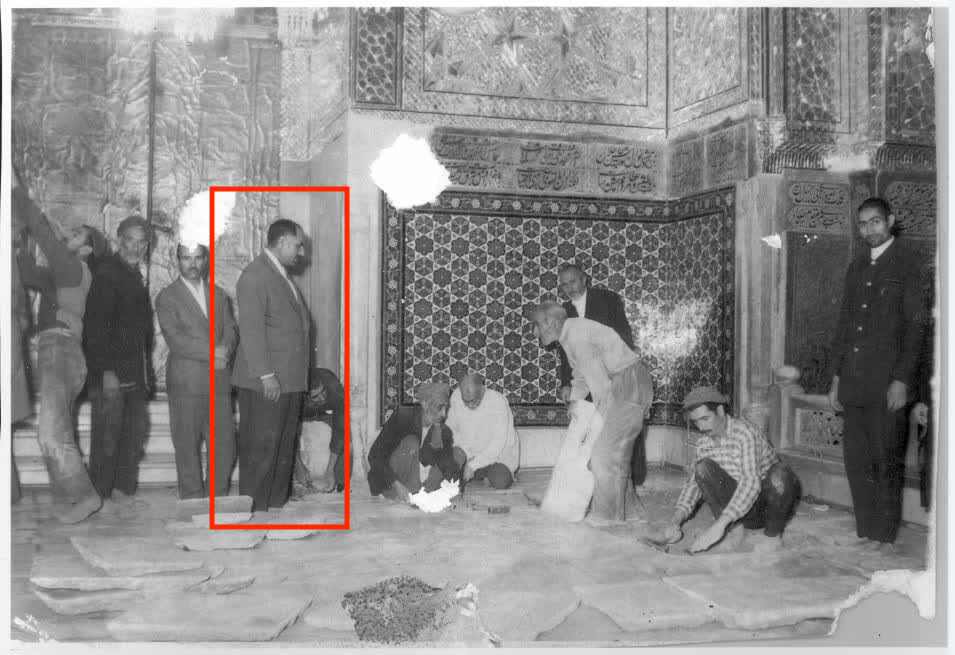

Despite the presumption among some that luster production ended during the Qajar period, documentary evidence and dated works confirm that it continued through the 1980s. The best examples are the signed and dated tiles of the Tomb of Pir Palandouz in Mashhad (map). The tilemakers responsible for this work were as follows: Mahmoud Moaveni, Shokrollah Khosdast Kashani, Habibollah Banna Razavi, Akbar Abbasnejad, Seyyed Abbas Alizadeh, and Gholamhossein Sahneyni. This octagonal tile was made by Shokrollah Khosdast Kashani, visible in the photo below (figs. 13–14).

In fact, Iran is one of the few countries where we can see a relatively continuous history in the production of luster pottery. The contemporary situation is also optimal, at least in terms of the number of potters who have the ability to make such pottery, thanks to books, educational videos, and workshops. Among these workshops are regular luster programs that I hold several times a year at the University of Kashan and which cover all stages and topics, including the kiln, materials and compositions, painting, and firing.

***

The production of luster pottery using the clay paste technique remains one of the most important technical achievements in the history of ceramics, and the role of Iran should be revised and updated in scholarship. Debates about the technique’s origin must consider both the contributions of Iranian scientists in ninth-century Abbasid Iraq (for example, Jaber ibn Hayyan) and those in later Seljuk and Ilkhanid Iran (for example, Mohammad ibn al-Barakat Jowhari Neyshaburi and Abo'l Qasem Abdollah Kashani). The artistic quality of Iranian works made during the medieval period was exceptional and still has a special and privileged position in Iran today, as well as internationally.

Citation: Abbas Akbari, “The History of Zarrinfam Pottery in Iran at a Glance.” Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.

Notes

- See Matin in Watson, Ceramics of Iran, 474. ↩

- On reduction in a kiln, see Valtat, Le lustre, Histoire et technique. ↩

- Allan, Islamic Ceramic, 8. ↩

- Porter, British Museum, Islamic tiles, 29. ↩

- Ettinghausen, Grabar, Jenkins-Madina, Islamic Art and Architecture, 69. Porter, Islamic tiles, 25. ↩

- Lane, Early Islamic Pottery: Mesopotamia, Egypt and Persia. ↩

- Mohammad Hassan Zaki, Al-fonūn al-Īrānī fī al-ʿAsr al-Islāmī. ↩

- See Arthur Lane’s migration theory in Lane, Early Islamic Pottery, 37. ↩

- Akbari, “Lessons from Muhammad Abi Al Barakat Johari Neishahbouri.” ↩

- al-Hassan, “An eighth century Arabic treatise on the colouring of glass.” ↩

- These sources are discussed by western scholars such as Allan, “Abul Qasim’s Treatise;” Caiger-Smith, Lustre Pottery; and Porter, “Les techniques du lustre métallique.” ↩

Bibliography (Persian, Arabic)

Manuscripts

- Mohammad ibn al-Barakat Jowhari Neyshaburi, Javāher-nāmeh-ye Neẓāmī, dated 592/1196. Malek Library, Tehran, MS. 3609.

Books and Editions

- اکبری، عباس. درسهایی از محمد ابی البرکات جوهری نیشابوری. تهران: مولف، ۱۳۹۶ ش. Akbari, Abbas, “Lessons from Muhammad Abi Al Barakat Johari Neishahbouri.” Tehran: self published, 1396 Sh/2014.

- اکبری، عباس. کاشی و کاشان. تهران: مولف، ۱۳۹۹ ش. Akbari, Abbas. Kāshī va Kāshān [Kashi and Kashan]. Tehran: self published, 1399 Sh/2019.

- افشار، ایرج. جواهرنامه نظامی. تهران: میراث مکتوب، ۱۳۸۳ ش. Afshar, Iraj. Javāher-nāmeh-ye Neẓāmī. Tehran: Miras-e Maktub Press, 1383 Sh/2004. [http://opac.nlai.ir/opac-prod/bibliographic/726016]

- زکی، محمدحسن. الفنون الایرانی فی العصر الاسلامی. بیروت: دارالرائد العربی، ۱۹۸۱ م. Zaki, Mohammad Hassan. Al-fonūn al-Īrānī fī al-ʿAsr al-Islāmī. Beirut: Dar al-Raed al-Arabi, 1981. [Lib.ir]

Bibliography (English, French)

- Allan, James W. “Abū’l-Qāsim’s Treatise on Ceramics.” Iran 11 (1973): 111–20. [JSTOR]

- Allan, James W. Islamic Ceramics. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 1991.

- Caiger-Smith, Alan. Lustre Pottery. London: Faber & Faber, 1985. [Internet Archive]

- Ettinghausen, Richard, Oleg Grabar, and Marilyn Jenkins. Islamic Art and Architecture 650–1250. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.

- al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. “An eighth century Arabic treatise on the colouring of glass: Kitāb al-Durra al-maknūna (the book of the hidden pearl) of Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (c. 721–c. 815).” Arabic Sciences and Philosophy 19, 1 (2009): 121–56. [Cambridge]

- Lane, Arthur. Early Islamic Pottery: Mesopotamia, Egypt and Persia. London: Faber & Faber, 1947. [Internet Archive]

- Piccolpasso, Cipriano. The Three Books of the Potter’s Art. Chatham: Scolar Pr., 1980.

- Porter, Venetia. Islamic Tiles. London: British Museum, 2005.

- Porter, Yves. « Les techniques du lustre métallique d’après Jowhar-nâme-ye Nezâmi (1196 AD). » Congrès international de céramique médiéval en Méditerranée, Athènes 11 (2003): 422–60. [pdf online]

- Valtat, Alain. Le lustre, Histoire et technique. Paris: A.A., Auxerre, 2016.

- Watson, Oliver, with Moujan Matin and Will Kwiatkowski. Ceramics of Iran. London: Yale University Press, 2020.

Videos by Abbas Akbari on YouTube

- “Kāshī and Kāshān.” YouTube, 17 April 2021, https://youtu.be/XvW2zTY47vQ?si=9Q6J0XkRyB0iDlQU

- “Where is Kashan? What is Lustre?” YouTube, 1 May 2021, https://youtu.be/XONUL6xNJKo?si=J1at91rn14DUUyBg

- “Secrets of Kashan: Insights with the Iranian Potter Abbas Akbari.” YouTube, 20 December 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bZJRf0rabWk

- “Lustre Ceramic Workshop in Berlin.” YouTube, 19 September 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kWIw2fS0Oa0

- “Natanz, A.H.707/1308 CE.” YouTube, 10 March 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uI1LP8el260

- “Spring in Varamin’s Lustre Flowerpot.” YouTube, 20 March 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mnG7GrLuWH8

- “Lustre Painting Workshop.” YouTube, 29 April 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-tuA39QHqBc

- “A practical study of Persian lustre sculptures at The Fitzwilliam Museum.” YouTube, 17 June 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2AF5NDb_-Do

- “Lustre Painting Workshop.” The Fitzwilliam Museum YouTube, 22 January 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YG8oU9BdSx8

- “From Kashan to Tapalpa.” YouTube, 19 July 2024, https://youtu.be/iSdoVQdCxgo?si=sd9p-7wP5KUeAssz

- “My WayWay!” YouTube, 31 July 2024, https://youtu.be/p1lhK1hJLes?si=JApehgcv-heyT4Go