History of Architectural Preservation in Iran and the Restoration of the Emamzadeh Yahya in 1361–63 Sh/1983–85

Zahra Khademi

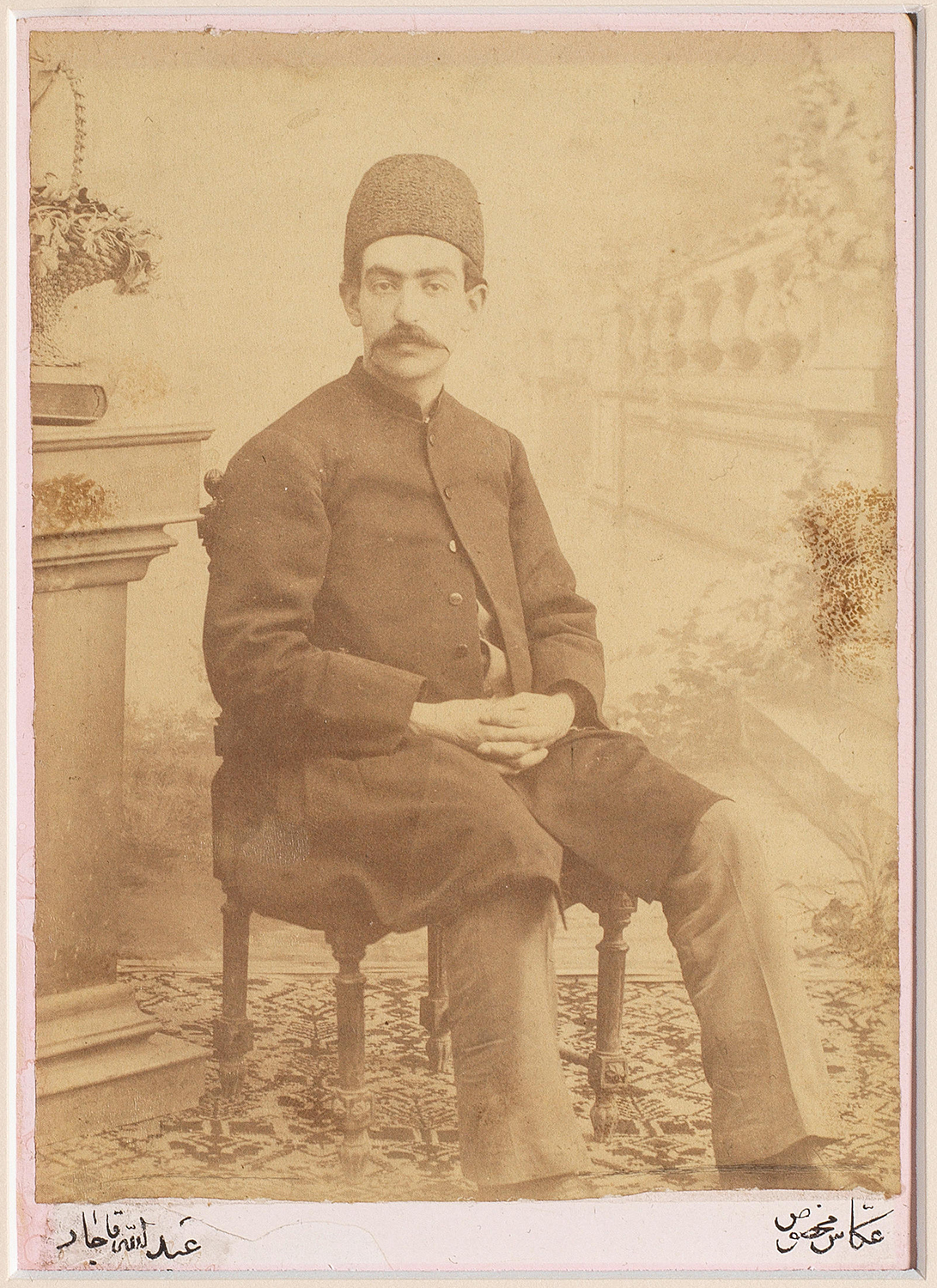

The preservation (حفاظت) and restoration (مرمت) of Iran’s cultural heritage have long been of paramount importance.1 The early twentieth century marked the initial steps towards conservation, starting in 1296 Sh/1917 with the establishment of the Department of Antiquities (شعبه عتیقات, Shoʿbeh-ye ʿAtiqat), under the Ministry of Education led by the minister Morteza Khan Momtaz al-Molk (fig. 1). This department, which was directed initially by the poet Iraj Mirza, laid the groundwork for systematic preservation efforts and included a modest museum (Muzeh-ye Iran) (fig. 2). Notable initiatives in the 1920s and 1930s included the formation of the National Monument Council (انجمن آثار ملی, Anjoman-e Asar-e Melli) in 1301 Sh/1922, the creation of an archaeological museum in Tehran in 1927 (map), and the establishment of the Department of National Antiquities in 1928 under the directorship of French architect André Godard (d. 1965) (see his page here).

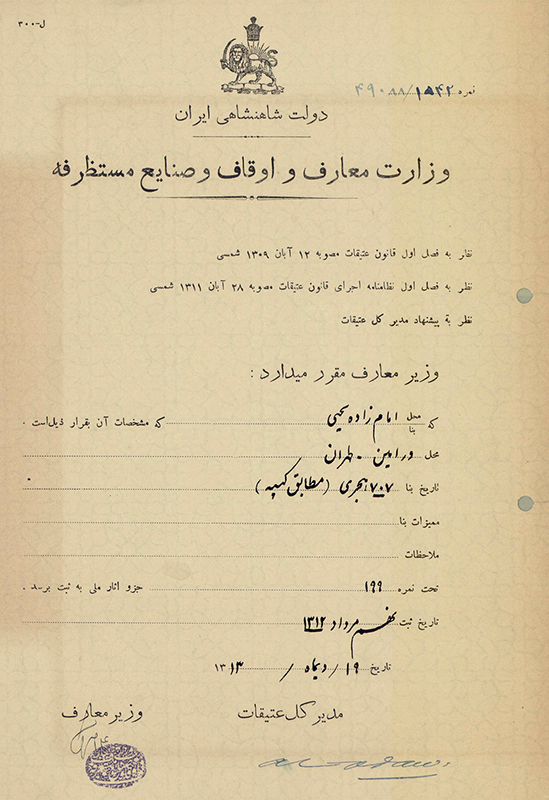

In 1309 Sh/1930, the National Consultative Assembly (مجلس شورای ملی, Majles-e Showra-ye Melli) enacted the Antiquities Law (قانون عتیقات, Qanun-e ʿAtiqat), which provided precise regulations for the classification and conservation of historical sites and monuments.2 This law mandated that all significant historical sites and monuments be identified and registered and also prohibited the restoration or alteration of any registered monument without the antiquities service’s permission and supervision. Subsequently, a section for the protection of historic buildings (سازمان حفظ بناهای تاریخی, Sazman-e Hefz-e Banaha-ye Tarikhi) was established within the department to oversee the conservation of monuments.

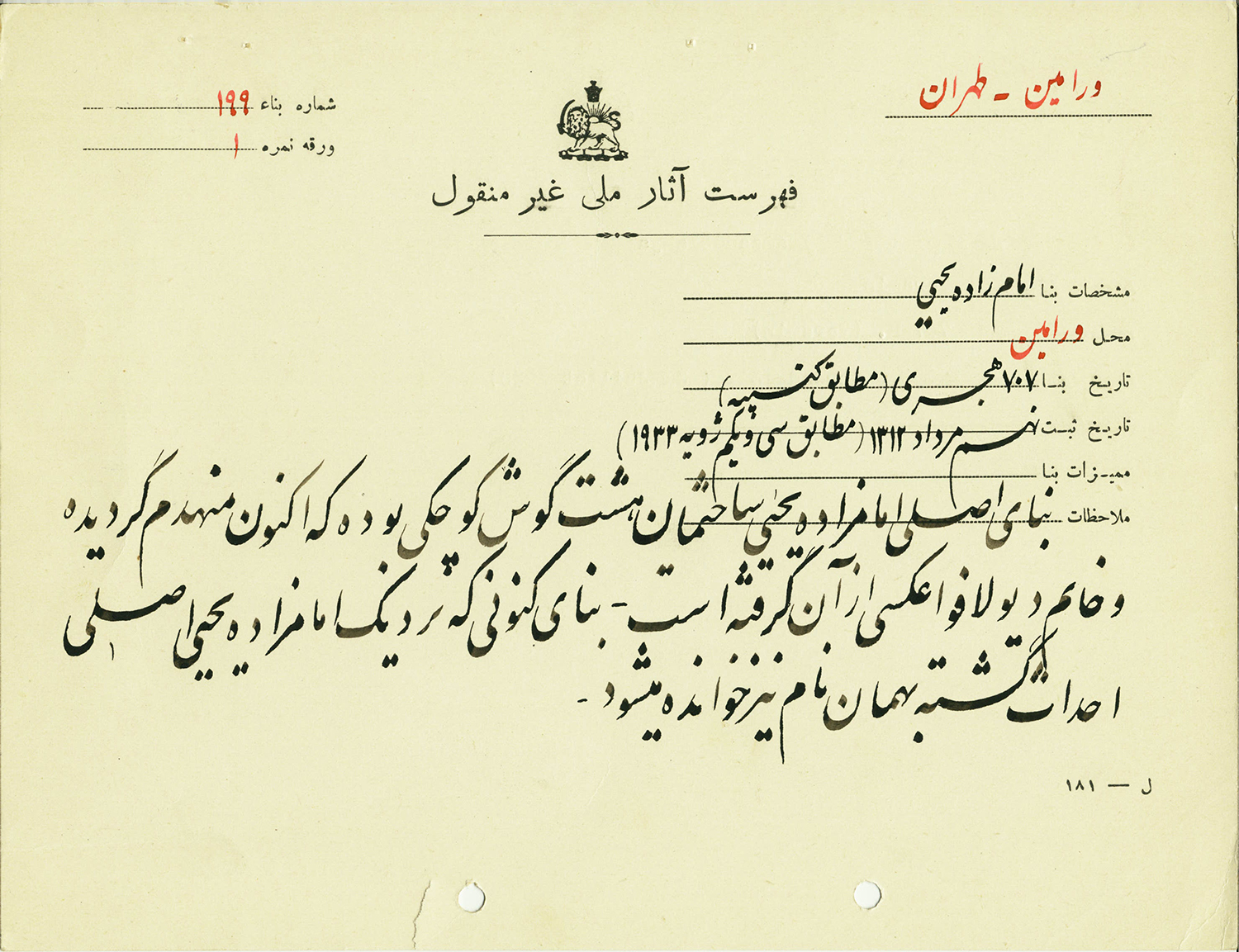

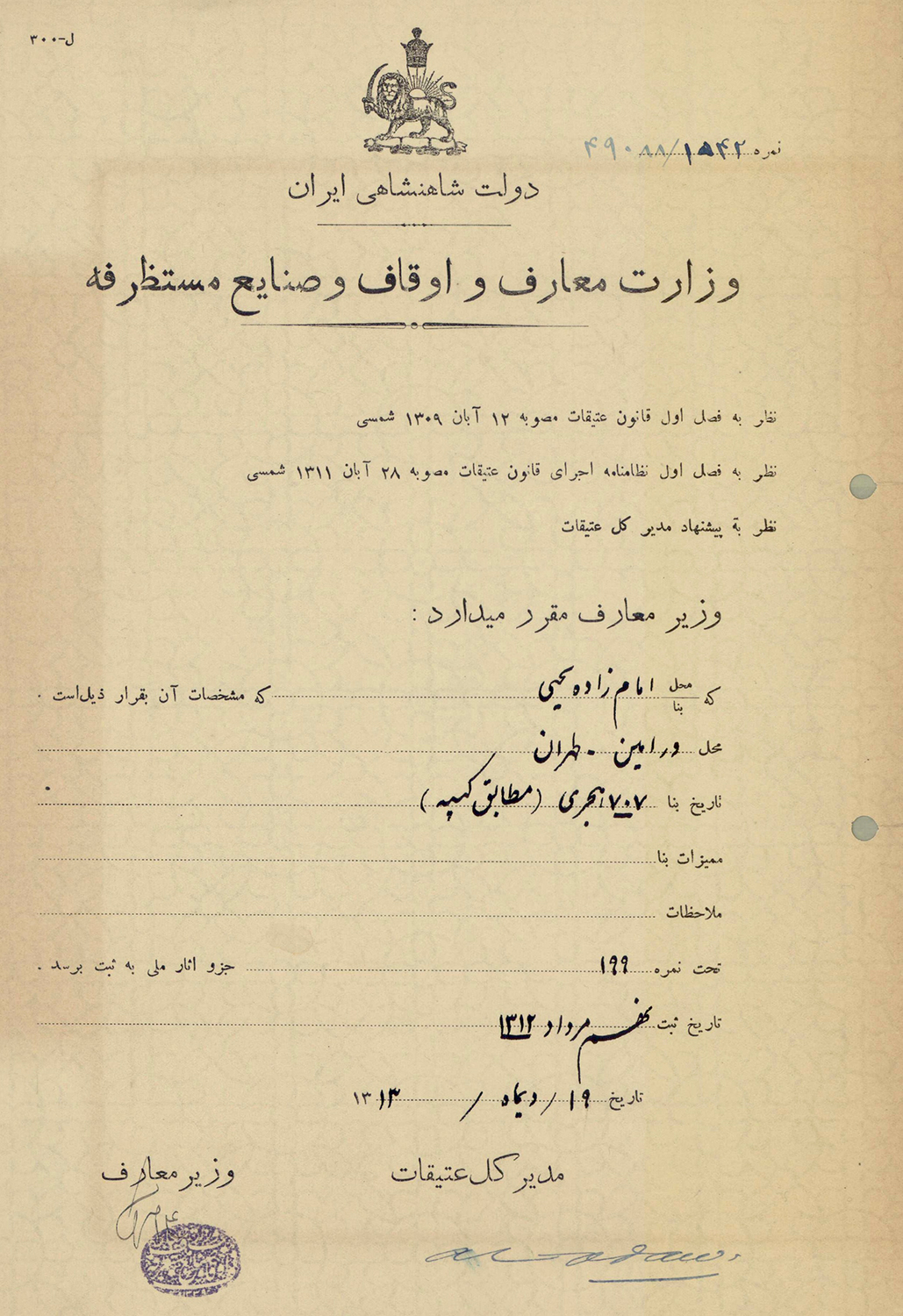

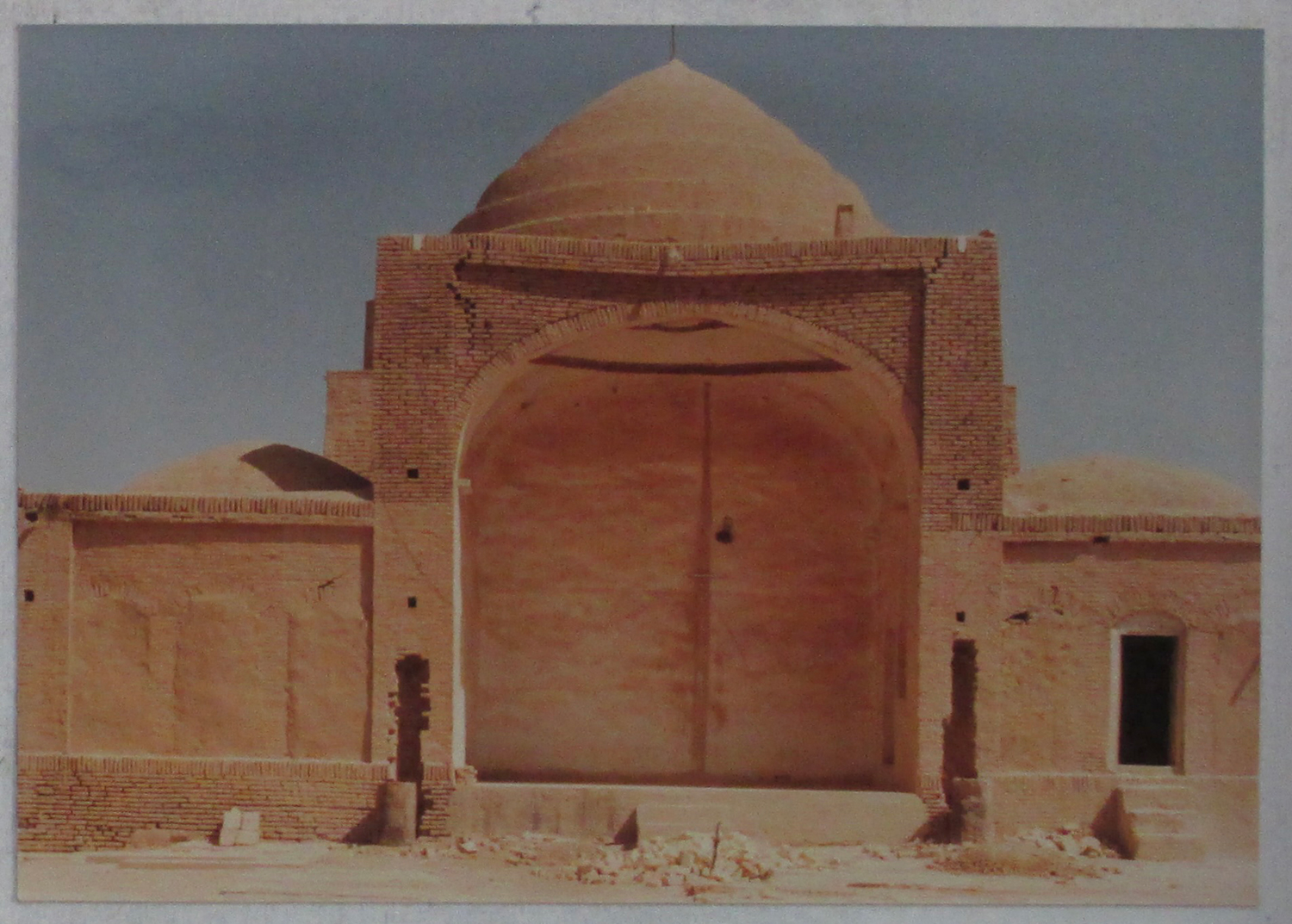

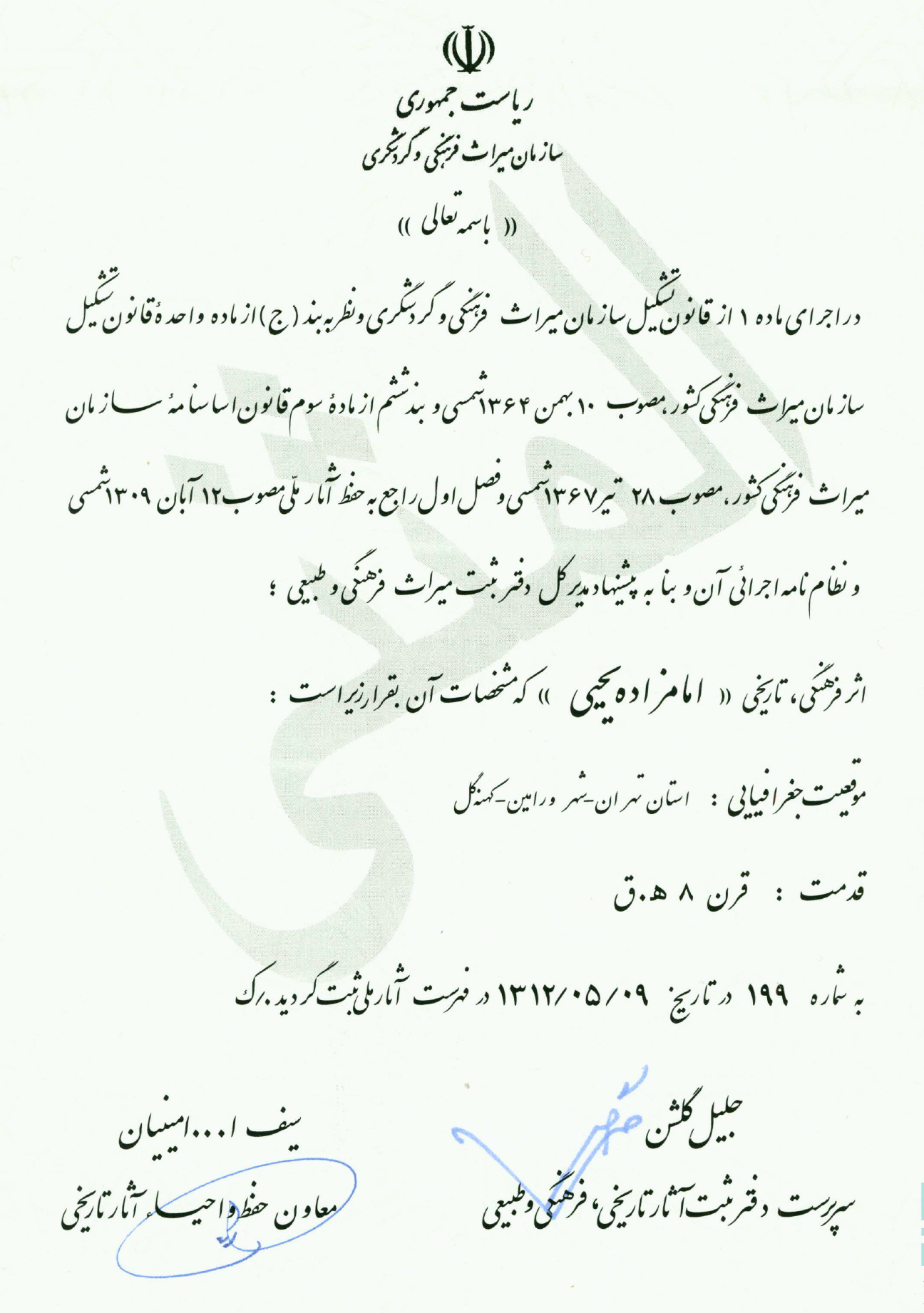

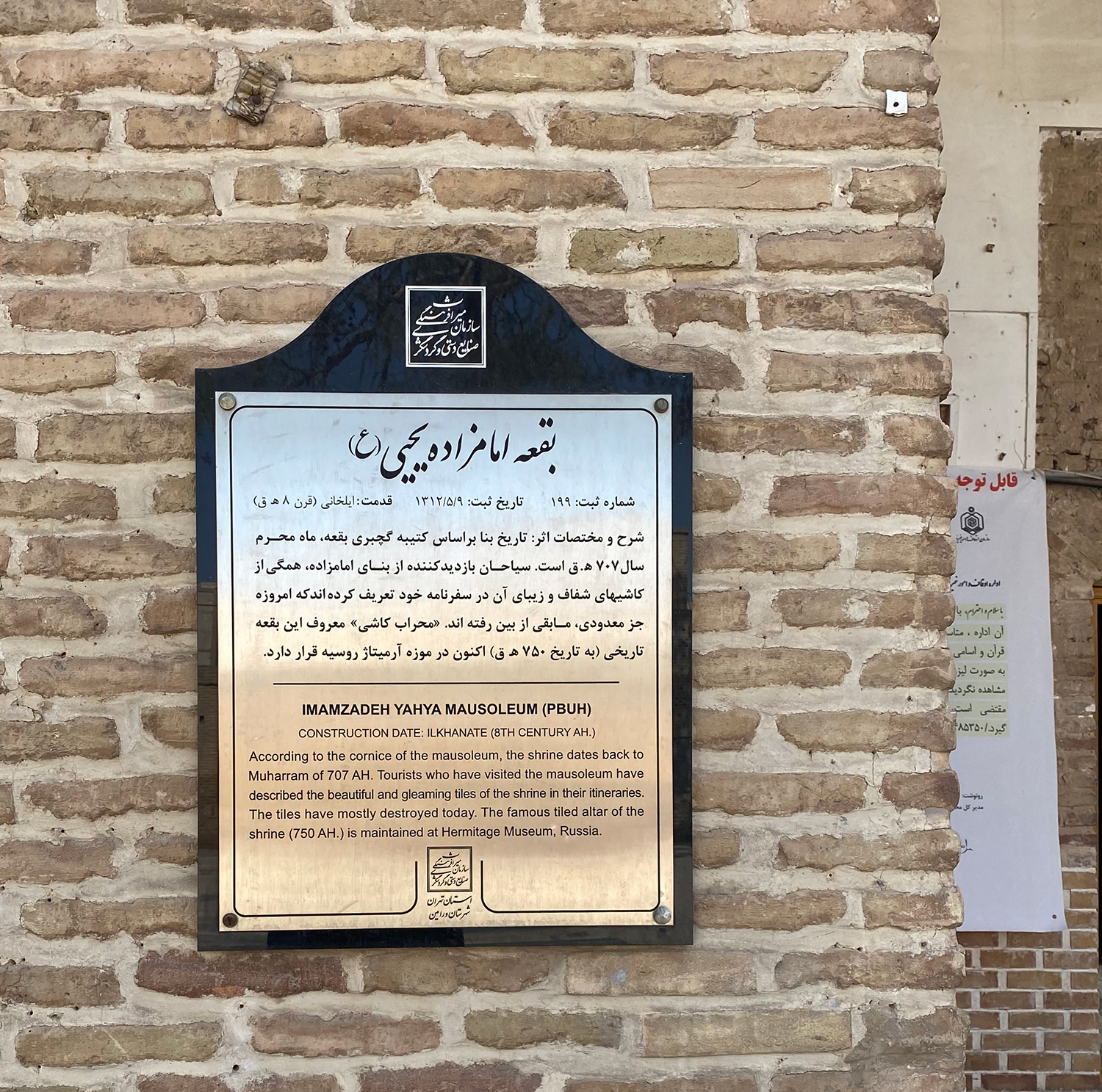

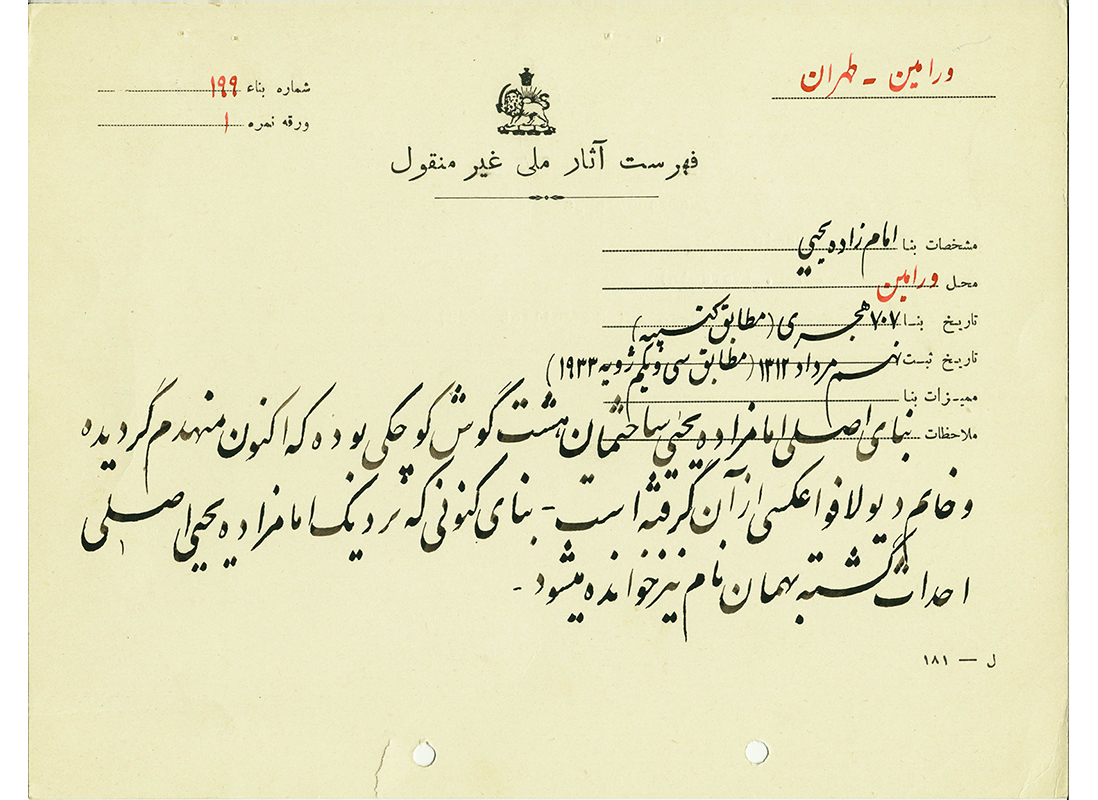

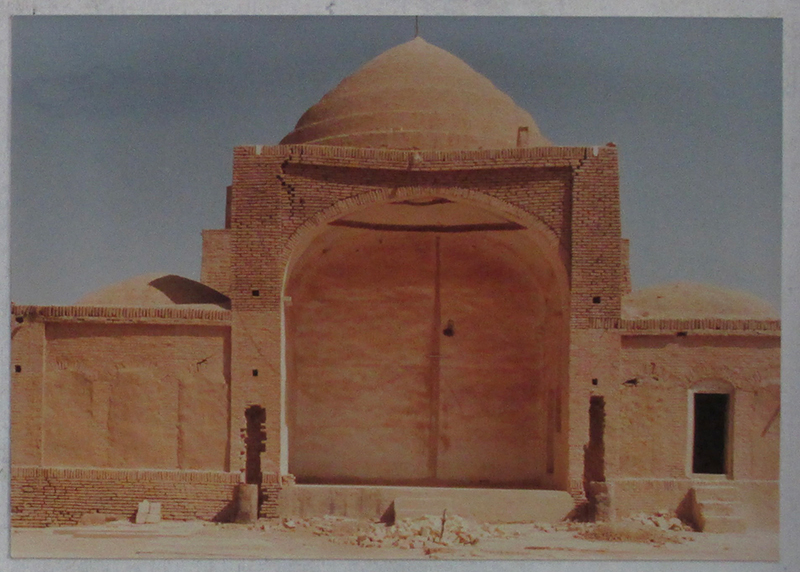

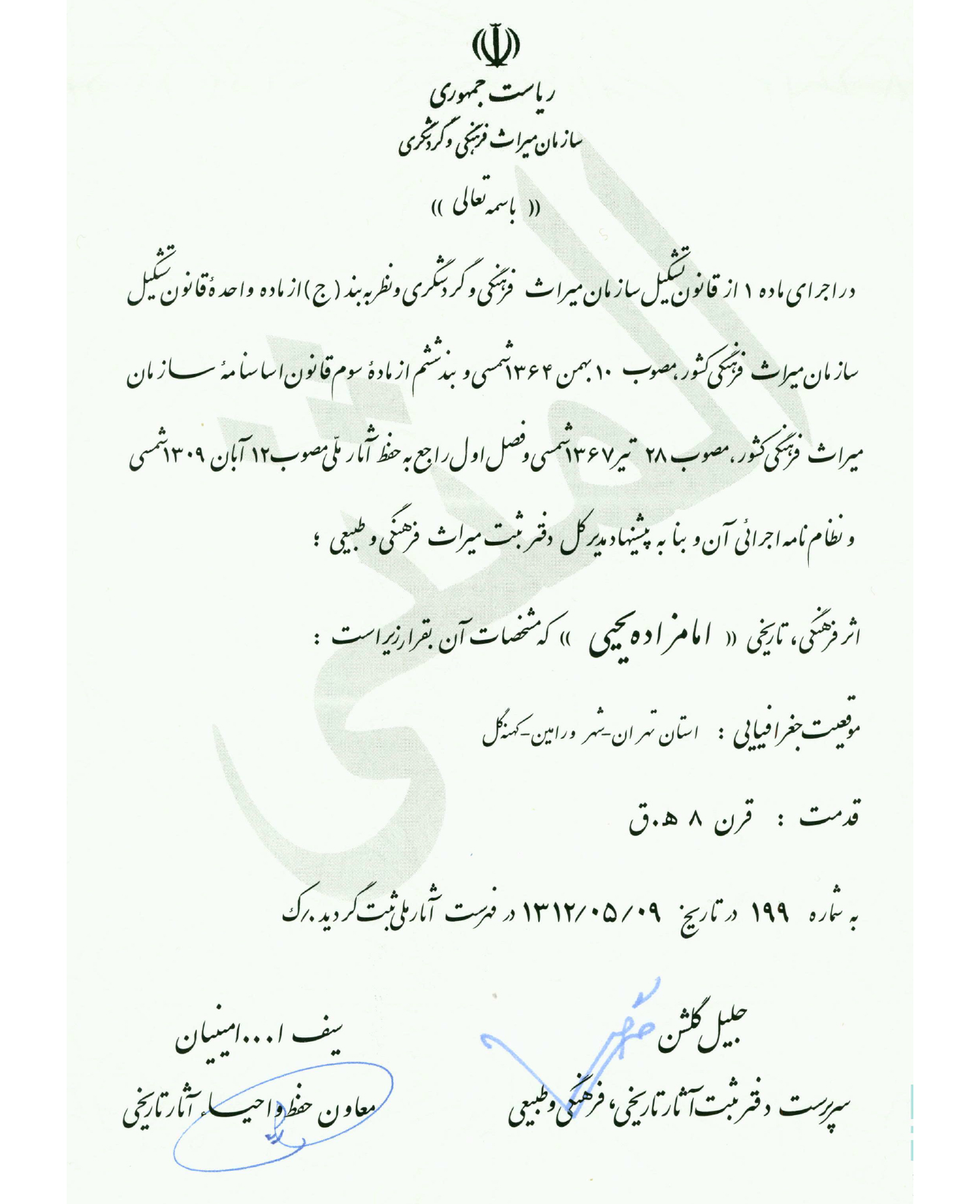

Under this law, on 9 Mordad 1312 Sh/31 June 1933, the Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin was added to the list of national monuments (فهرست آثار ملی غیرمنقول, Fehrest-e Asar-e Melli-ye Gheyr-e Manqul) with the registration number 199 (figs. 3–4). Its date was recorded as 707 [1307], in reference to the date in the stucco inscription inside the tomb (see Stucco Inscription).

The establishment of the National Organization for the Preservation of Historic Monuments of Iran (سازمان ملی حفاظت آثار باستانی ایران, Sazman-e Melli Hefazat-e Asar-e Bastani-e Iran) in 1344 Sh/1965 further advanced preservation efforts. Part of the Ministry of Culture and Arts, this organization opened technical bureaus in provincial capitals, each headed by an archaeologist, civil engineer, and local architects. It coordinated restoration projects across the country and often collaborated with international bodies such as the Italian government’s Dipartimento per l’Assistenza Tecnica.3 Such collaborations transformed sites and monuments under restoration into training workshops for Iranian technicians and conservators. Advanced conservation techniques were tested, and traditional crafts in wood, stone, stucco, ceramics, and other materials were preserved or revived. Additionally, an institute for restoration was established within the Department of Architecture at the National University in Tehran. This institute partnered with the Department of Architecture at the Università di Firenze on a comprehensive restoration program for the tomb of Oljaytu in Soltaniyeh (map).

The Islamic Revolution of 1357 Sh/1979 and the subsequent Iran-Iraq war (1980–88) posed significant challenges to the preservation of Iran’s cultural heritage. Many monuments were endangered, and there was a brief period when historical sites were viewed as symbols of past monarchical regimes. However, in 1362 Sh/1983, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini (d. 1989) issued an edict emphasizing that the cultural and artistic wealth of Iran belonged to the people and necessitated respect and preservation.

Restoration of the Emamzadeh Yahya, 1361–63 Sh/1983–85

Following the renewed commitment to preservation in the early 1980s, technical officials were deployed across Iran to address vandalism and repair significant damages. Among these efforts, Mohammad Hasan Moheb-Ali, director of the technical bureaus in the Tehran branch of the Sazman-e Melli, spearheaded the restoration of the Emamzadeh Yahya between 1361–63 Sh/1983–85. Moheb-Ali held a master’s degree in architecture from Shahid Beheshti University and had also trained at the Iran Restoration Institute under the guidance of esteemed professors Piero Sanpaolesi and Dr. Reza Kasaei, particularly during the restoration of the tomb of Oljaytu (1969–78).4

Moheb-Ali’s reports to the Sazman-e Melli outline the restoration of the Emamzadeh Yahya over three years. The work was extensive and focused on the north and south eyvans (ایوان), side rooms, interior, and exterior of the tomb (گنبدخانه, gonbad-khaneh), as well as the courtyard.

1. North and south eyvans of the tomb

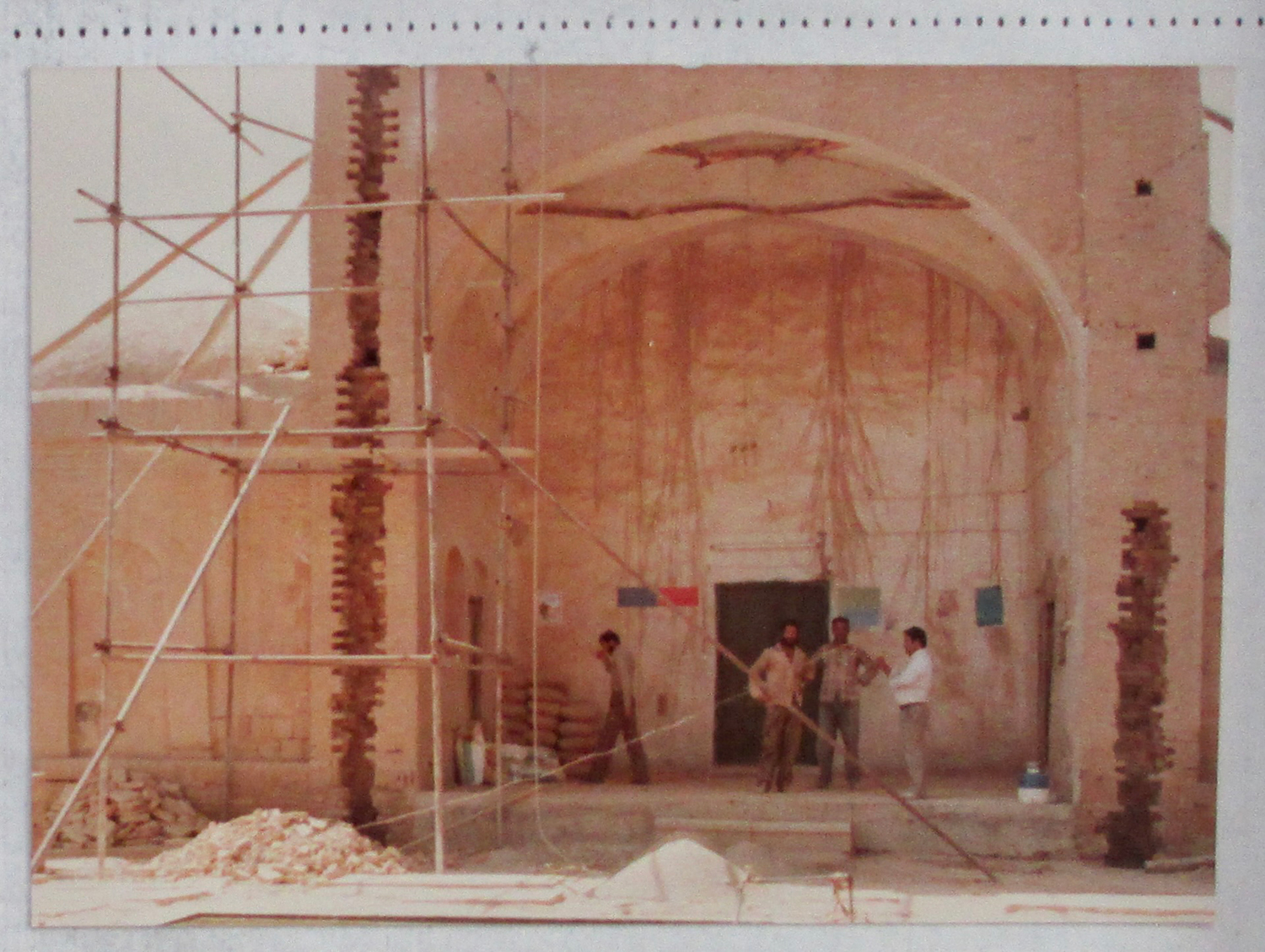

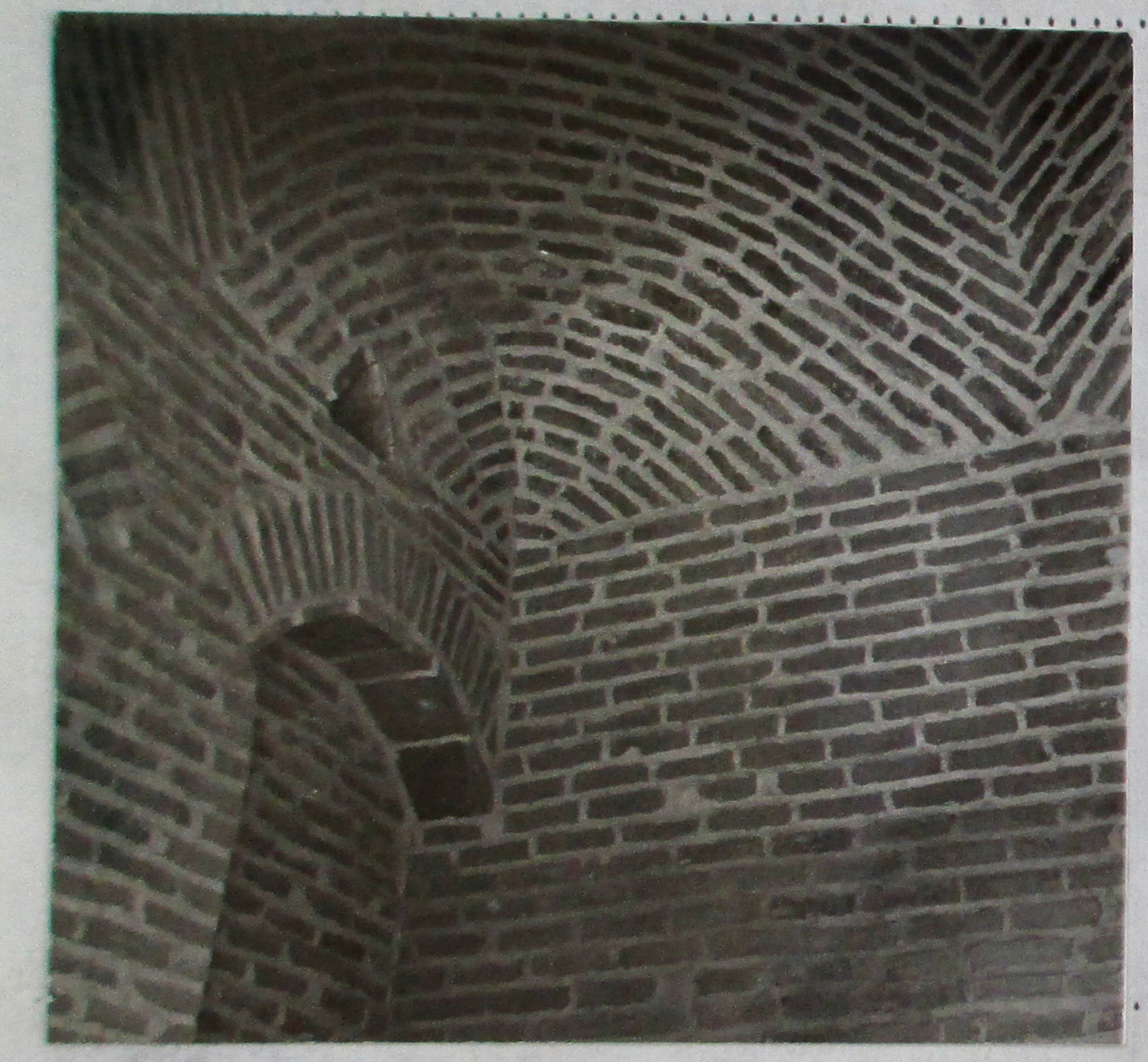

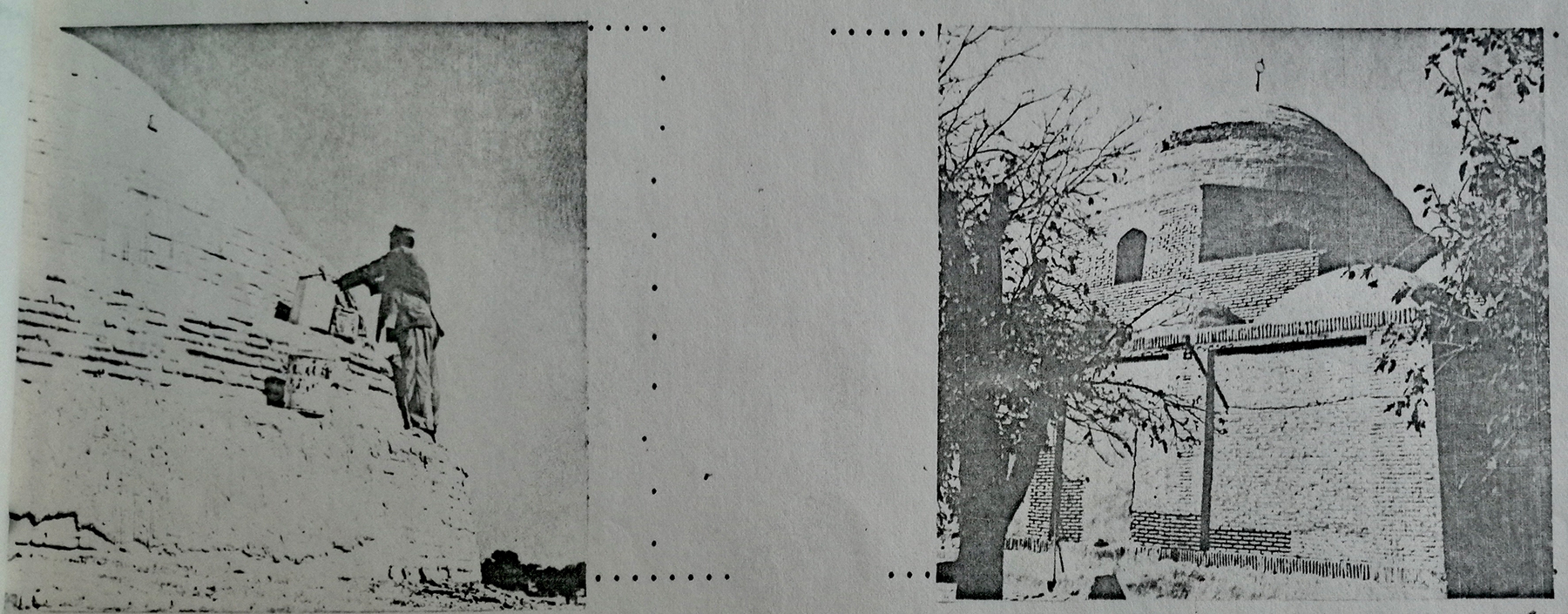

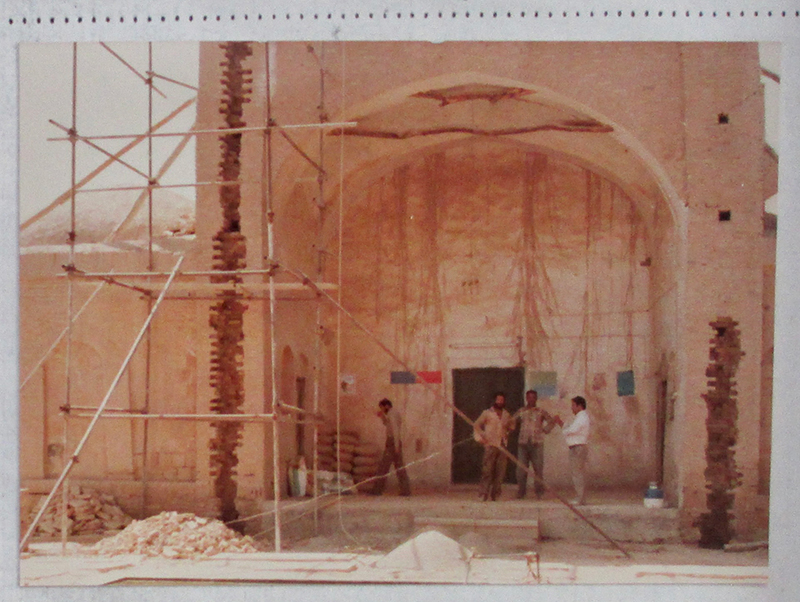

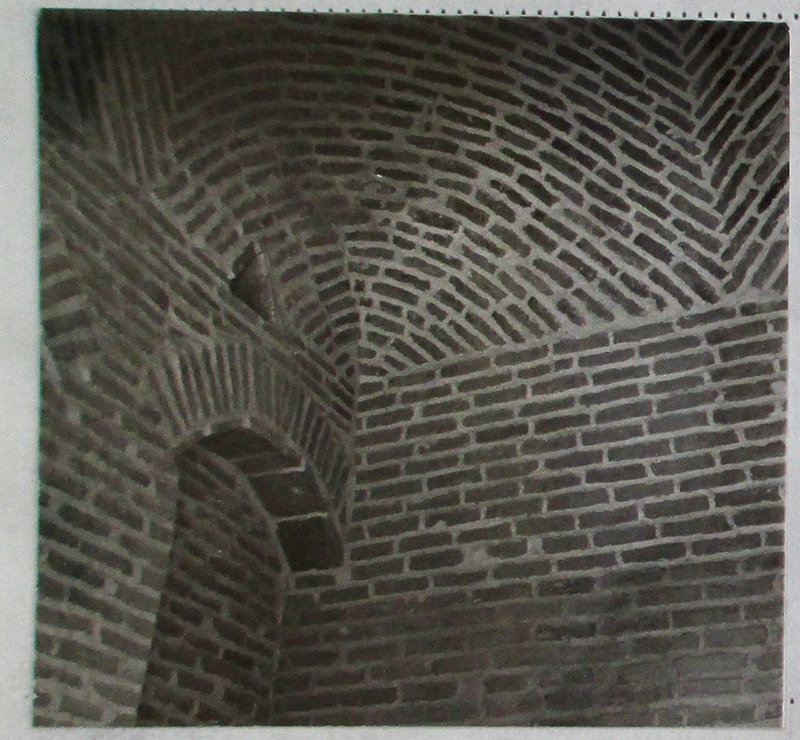

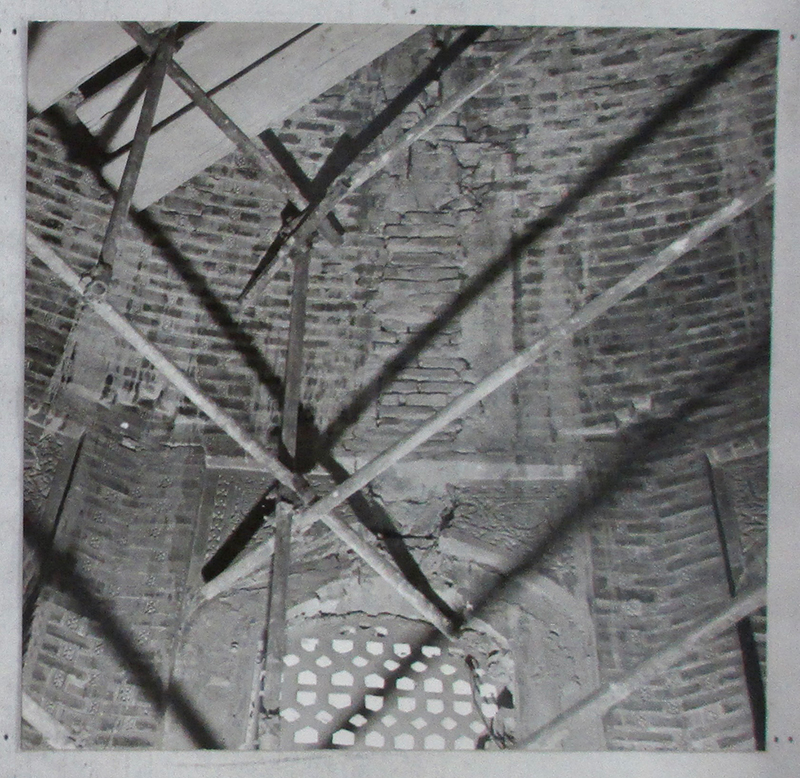

A major task was the reinforcement of the pre-existing columns inset into both sides of the portals (پیشطاق, pishtaq) framing the north and south eyvans. The areas beneath the columns were excavated, iron plates were installed in the excavated areas, and concrete was poured to support the columns. The brickwork running vertically up the portal was steadily removed, and double iron columns were welded to metal plates to carry out the eyvans’ bracing (کلاف کشی) (fig. 5). Finally, the brickwork around the columns was redone, including re-grouting (بندکشی).

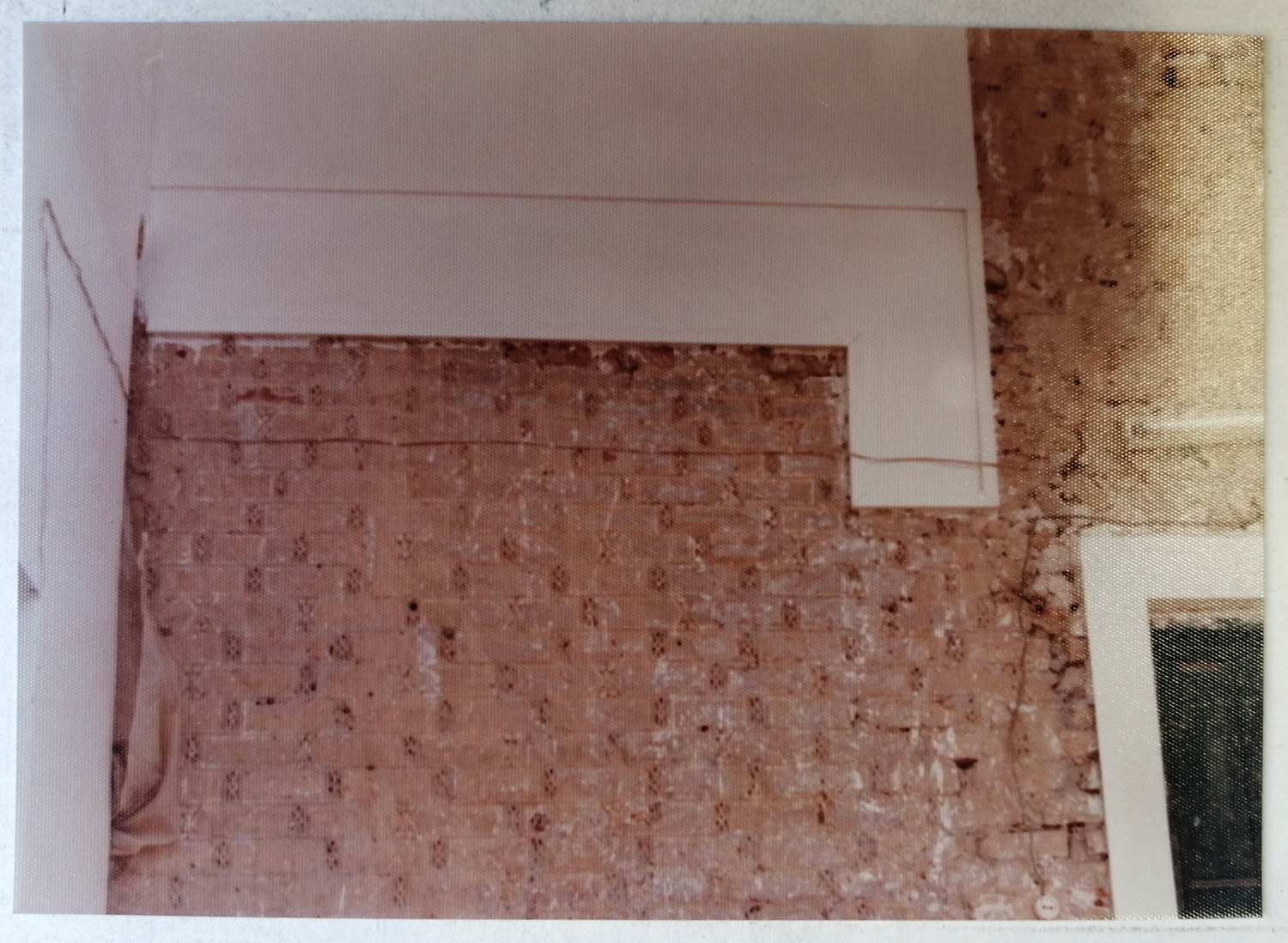

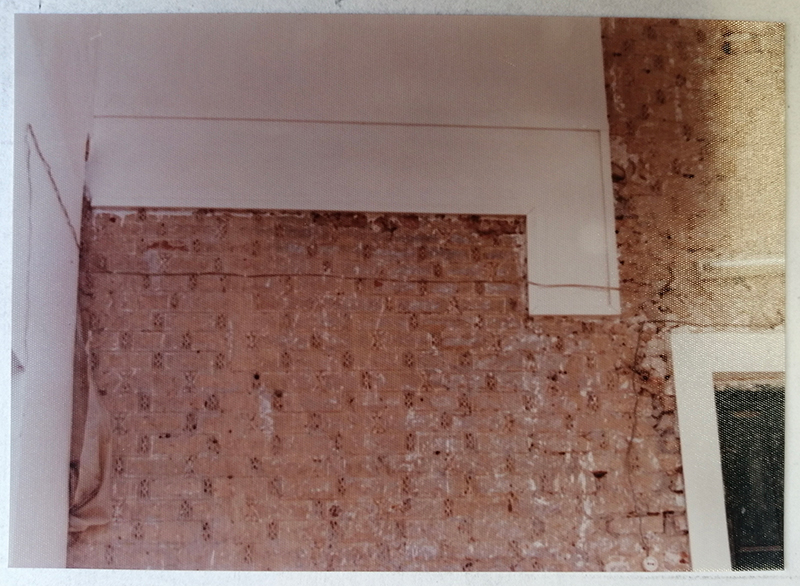

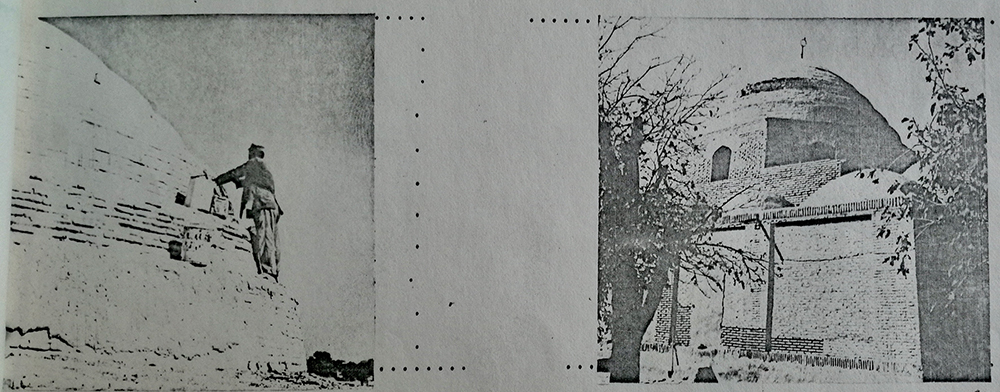

In the north eyvan, deteriorating layers of plaster were removed, revealing the original facade beneath. The upper part of the eyvan was replastered to reinforce the structure while original brickwork was left exposed below (figs. 6–7). Furthermore, the facade of the northern section was grouted, and the brickwork along the roof edge (هره چینی) was restored to ensure its stability and appearance.

The south eyvan received similar attention (fig. 8). The deteriorating plaster was removed and new plaster was added.

2. Side rooms of the tomb

The small rooms adjacent to the eyvans were also addressed. Their floors were paved using traditional khataʾi (ختائی) bricks, and the brickwork of the walls was re-grouted to maintain consistency with the architectural style (fig. 9). The walls were also thoroughly cleaned.

3. Interior of the tomb

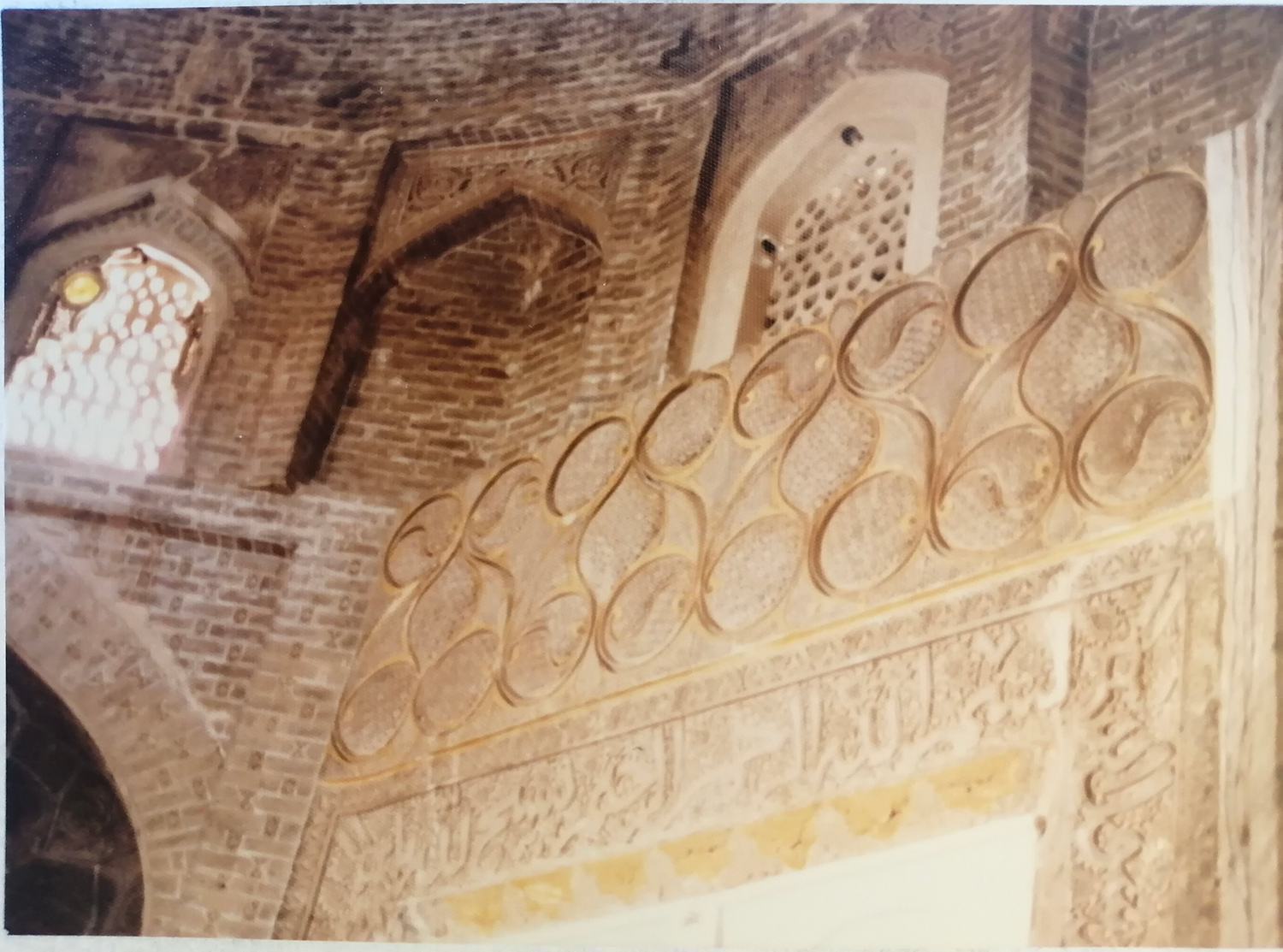

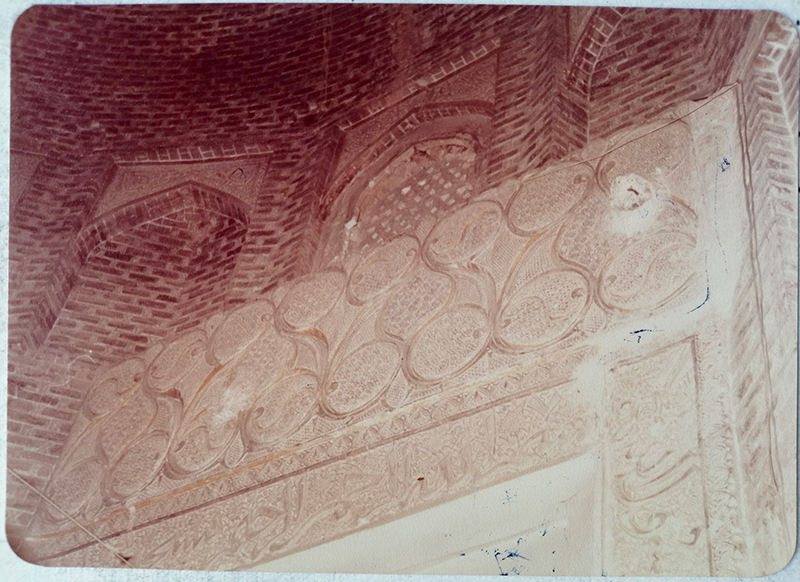

Attention focused on the historical stucco (گچبری, gachbori) elements, including the mihrab area on the qibla wall, epigraphical elements at the apex of the dome, and windows in the zone of transition. The mihrab area required restoration and consolidation (مرمت و تحکیم):

- Excess plaster behind the mihrab was carefully removed.

- The back of the stucco mihrab (گچبری محراب) was cleaned to free and stabilize it.

- The stucco mihrab was then lifted using jacks and repositioned in its original location (moved slightly higher and further back).

- Special anchors (rawl plugs) were used to reinforce the mihrab.

- Brickwork was laid beneath the stucco mihrab to secure and stabilize its base.

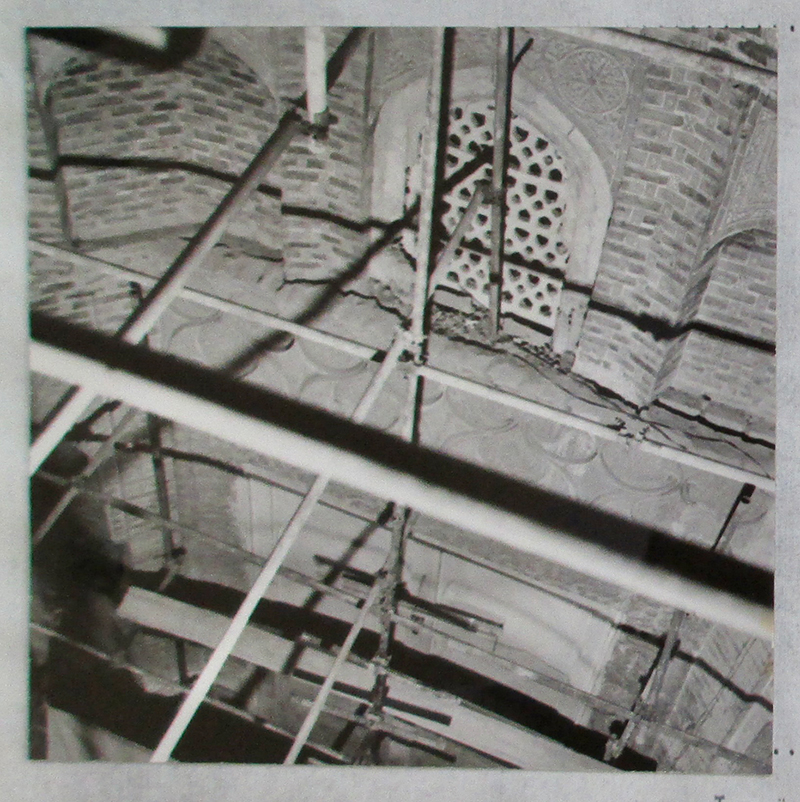

These references to the ‘stucco mihrab’ seem to refer to the large horizonal stucco panel above the mihrab void (once filled with the luster tiled ensemble).5 A photograph taken in 1362 Sh/1983 shows debris behind the top part of the stucco panel and gaps between it and the brick wall (fig. 10). A photograph taken the next year shows white plaster consolidation on its right edge (fig. 11).

The removal of old plasterwork again revealed important original decoration.6 Directly inside the stucco inscription framing the mihrab, the imprints of a previous border of half star and cross tiles were exposed (fig. 12, compare to fig. 11). Like the mihrab, these luster tiles had long since been removed from the tomb (see History of Evolution).

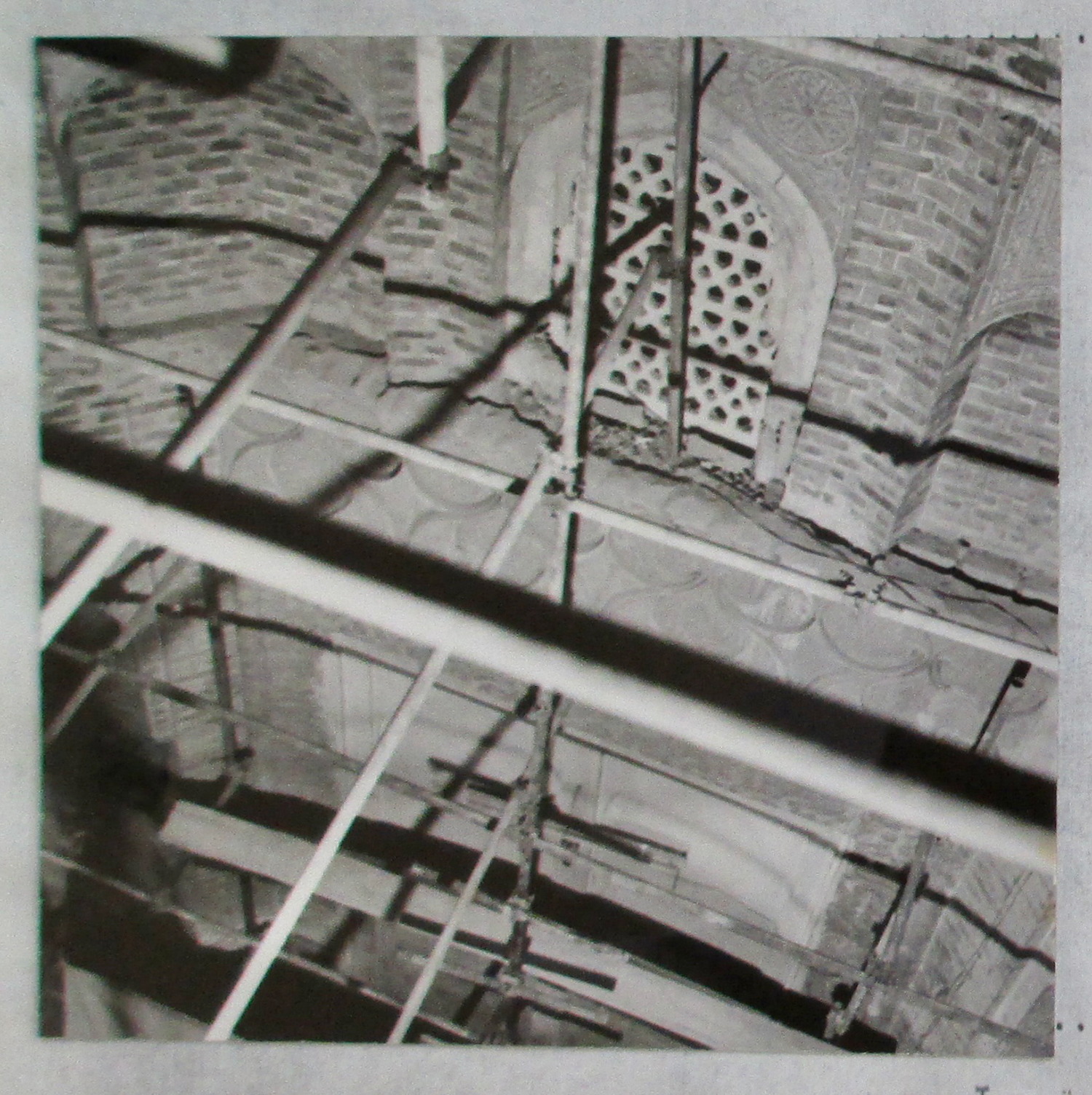

Some of the stucco windows in the zone of transition were also restored (fig. 13). This included grouting the areas around them to ensure stability.

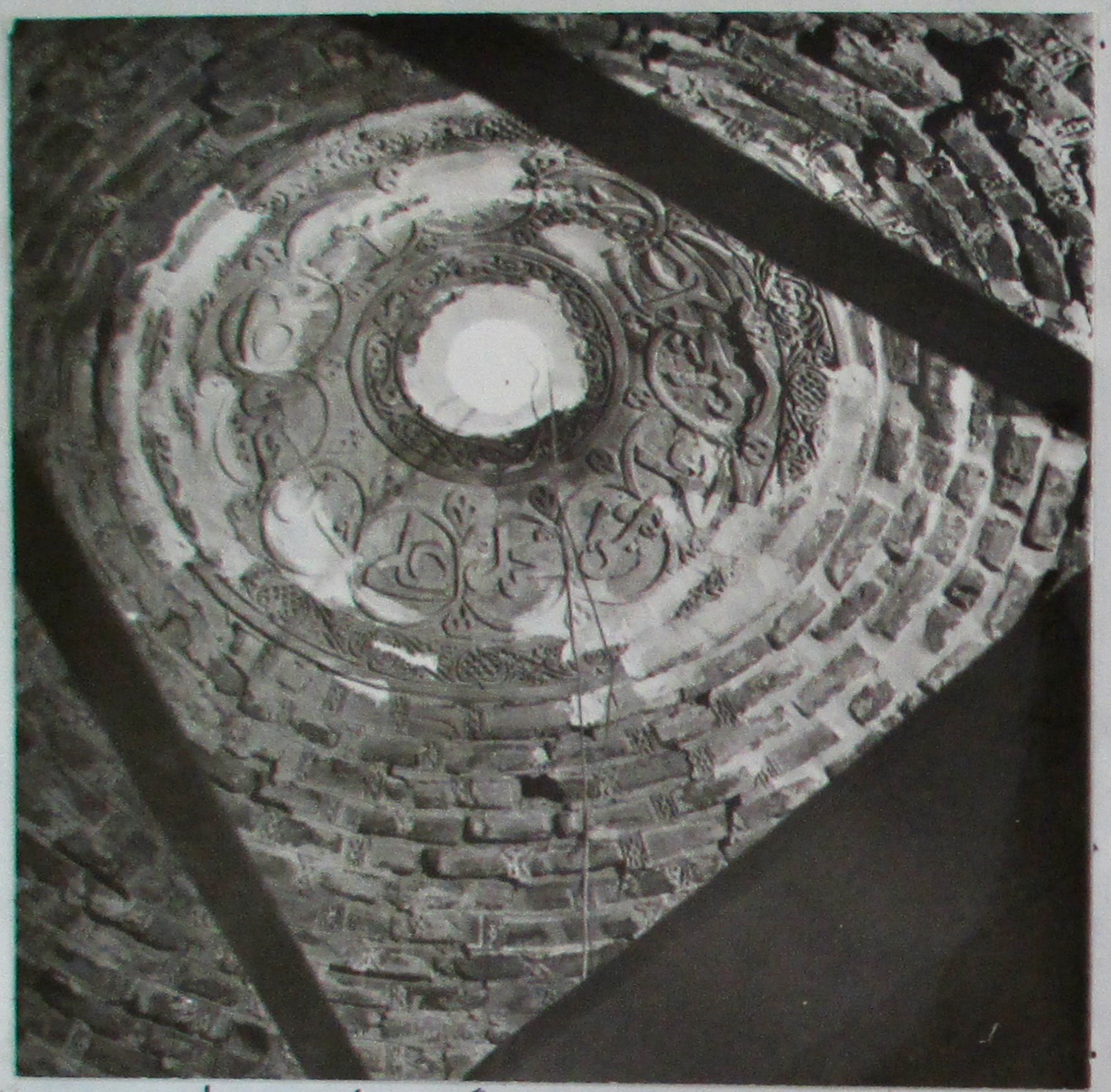

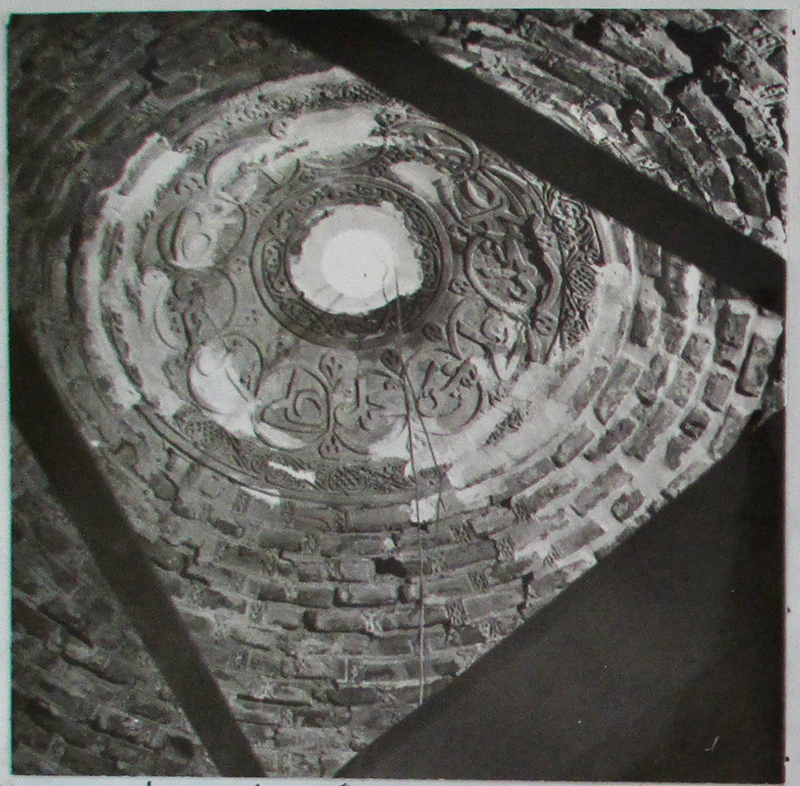

Attention also focused on the apex of the dome, which includes small epigraphic roundels with the names of the Emams (fig. 14).

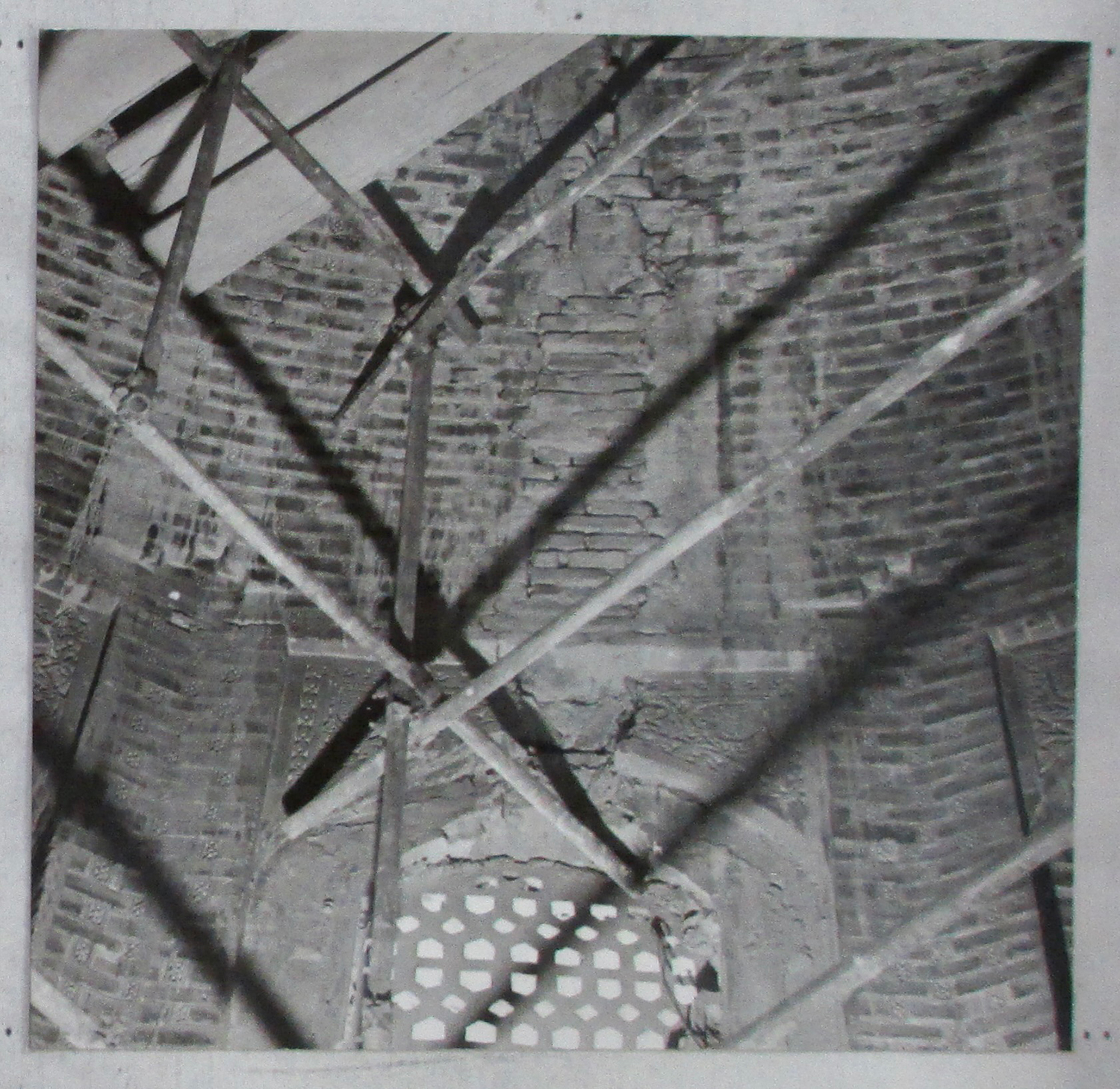

4. Dome of the tomb

Attention focused on clearing and re-grouting gaps between the bricks on the exterior of the dome (fig. 15).

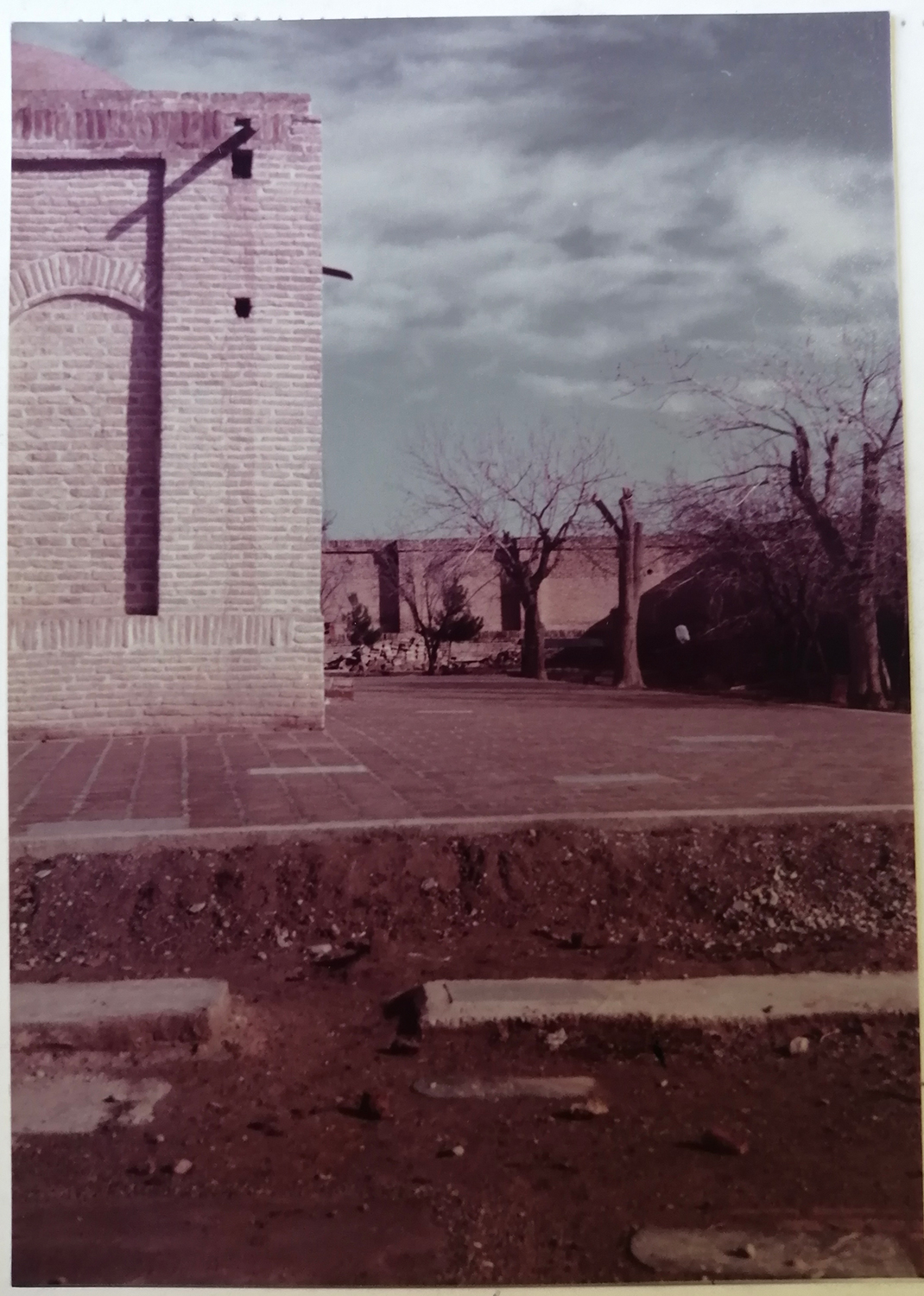

5. Courtyard

The courtyard area immediately surrounding the tomb was carefully graded and paved (شیب بندی صفه سازی) to ensure proper drainage and prevent moisture infiltration. A concrete boundary was erected to serve as a moisture barrier, filled with gravel and crushed stone, and leveled and surfaced with a layer of mortared paving (شفته ریزی) (figs. 16–17).

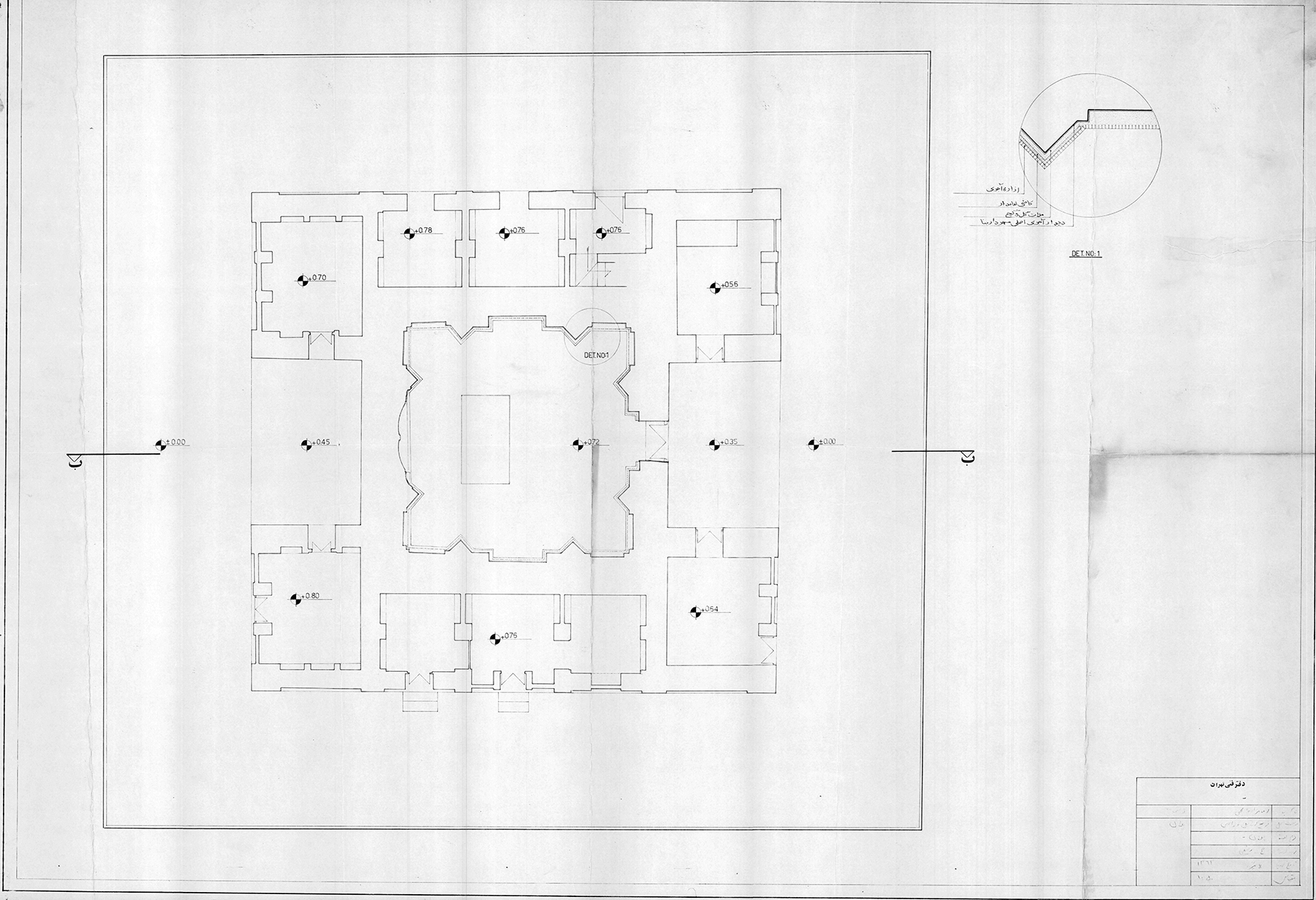

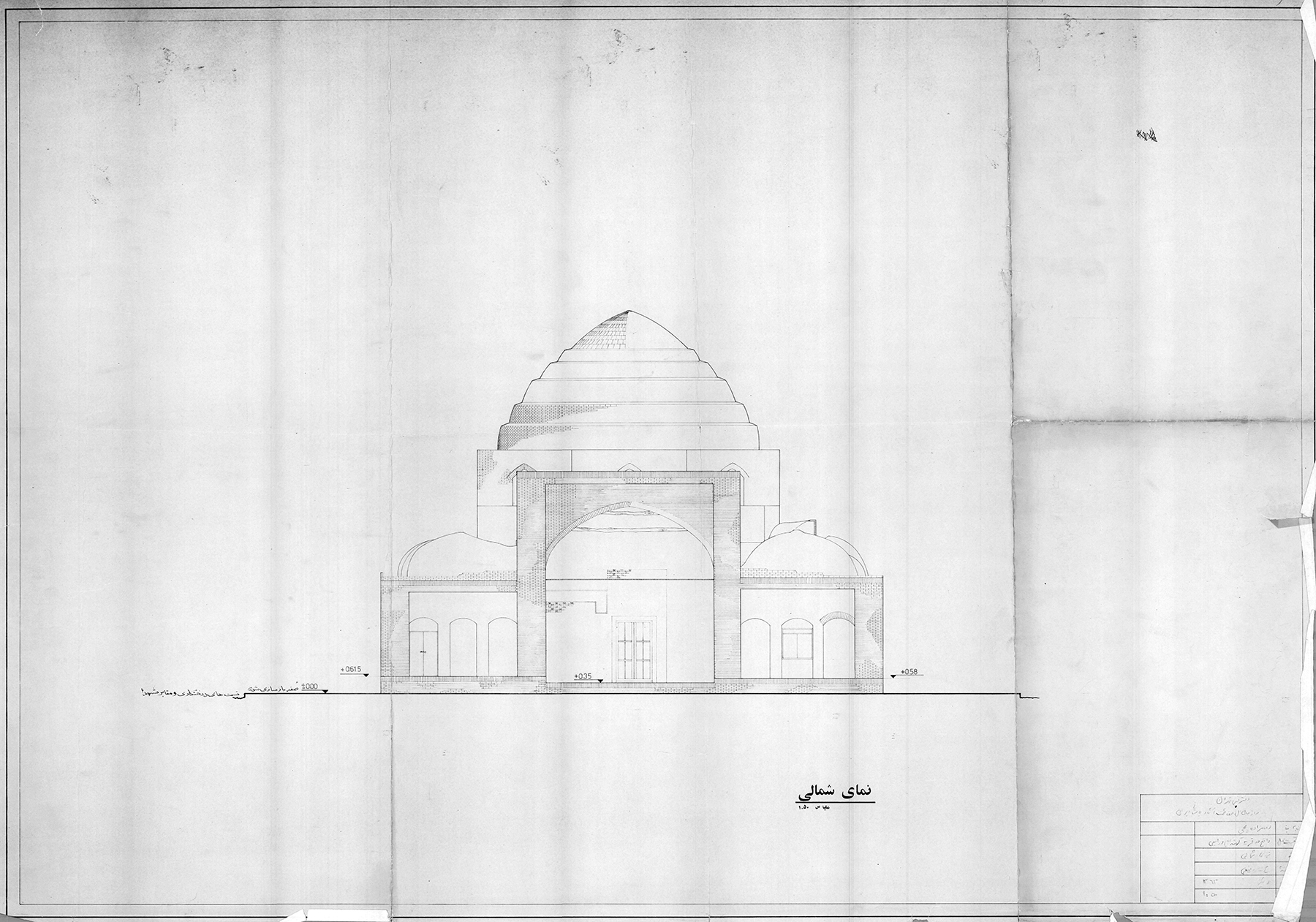

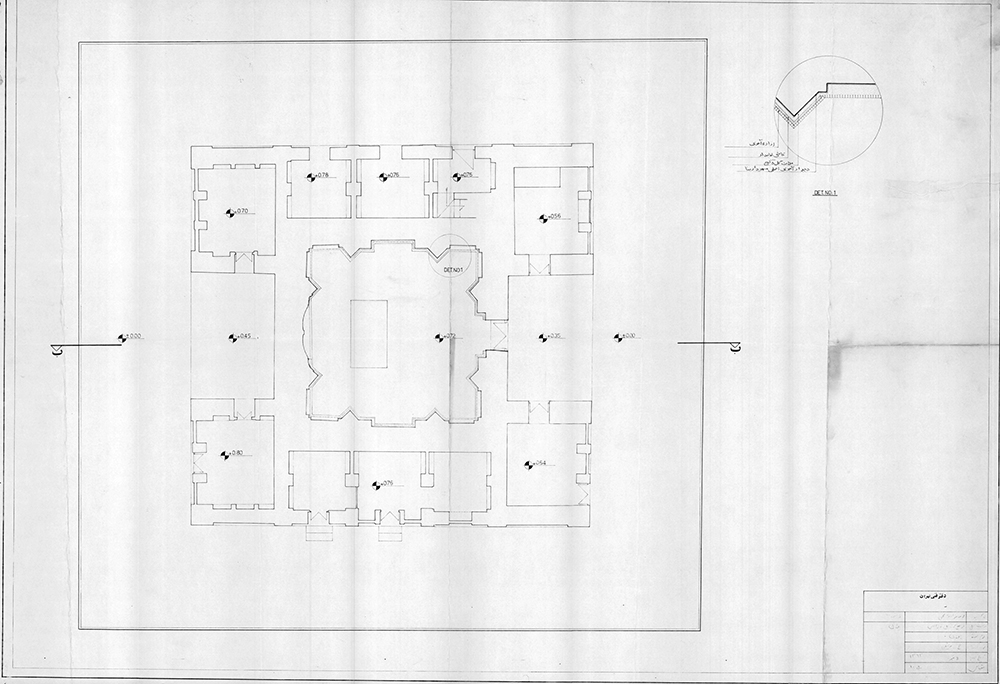

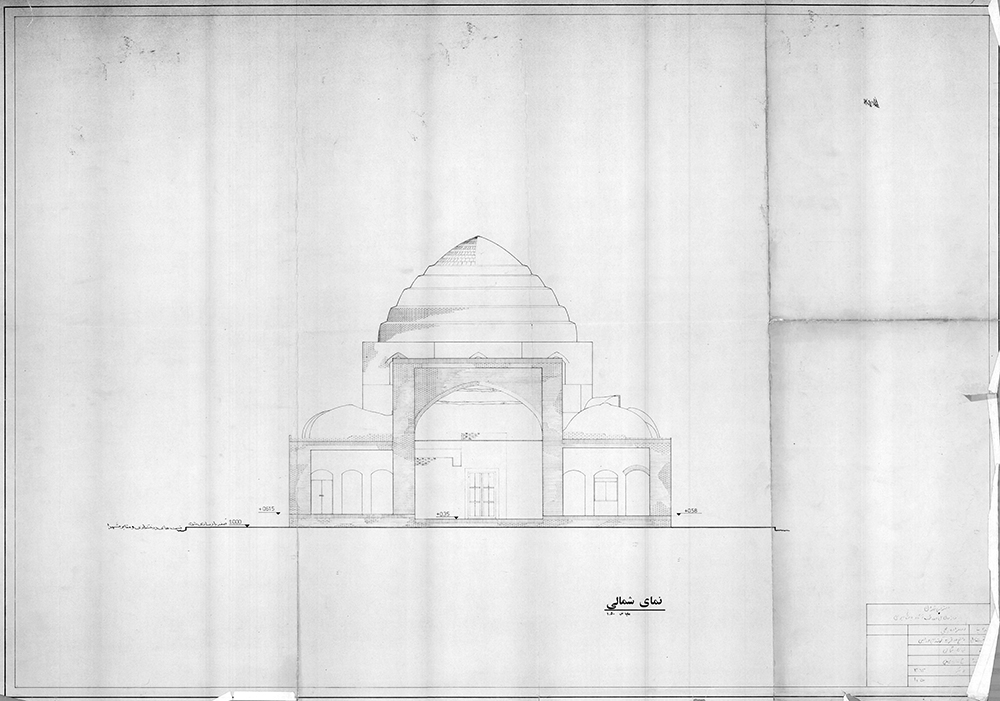

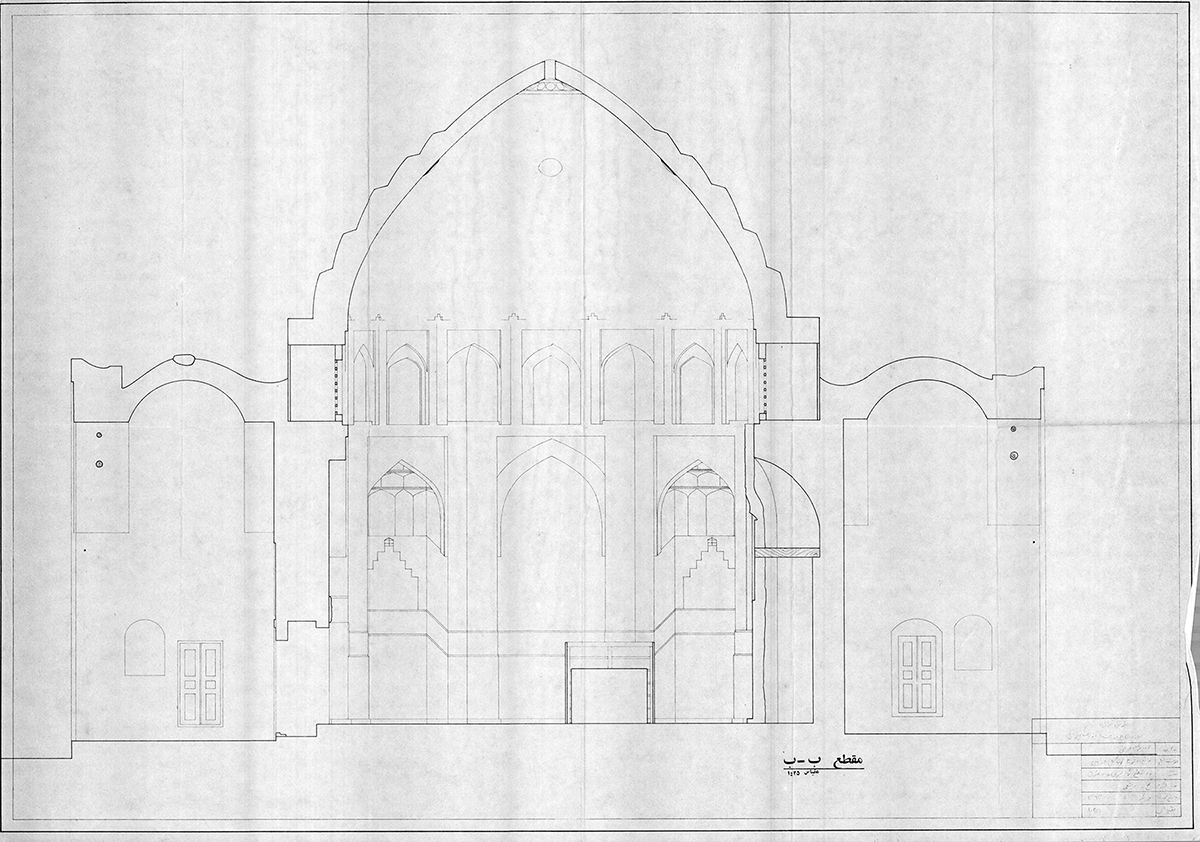

Another important component of the preservation of the Emamzadeh Yahya in the early 1980s was the drawing of a detailed plan and two sections by the accomplished draftsman Ataollah Rafiei. Rafiei’s drawings are notable for their careful attention to detail, including the depiction of the rectangular zarih (screen around the cenotaph) and the intricate brickwork in the eyvans. These drawings highlight the precision and thoroughness of the restoration efforts and ensured that the smallest details were faithfully documented (figs. 18–20). We can assume that they were ordered at the end of the restoration efforts.

Formation of ‘Miras’

From 1364 Sh/1985 onwards, all conservation and restoration activities were coordinated by Iran’s Cultural Heritage Organization (سازمان میراث فرهنگی ایران, Sazman-e Miras-e Farhangi-e Iran), known commonly as ‘Miras,’ which evolved from the former Organization for the Preservation of Historic Monuments (fig. 21). In 1382 Sh/2003 and 1385 Sh/2006, the fields of tourism and handicrafts were integrated into Miras, forming Iran’s Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Handicrafts Organization (سازمان میراث فرهنگی، گردشگری و صنایع دستی ایران, Sazman-e Miras-e Farhangi, Gardeshgari va Sanayeʿ-e Dasti-ye Iran). In 1398 Sh/2019, Miras became part of the newly created Ministry of Cultural Heritage, Tourism, and Handicrafts, whose creation represented a structural shift from what was previously an ‘organization’ into a full-fledged ‘ministry.’ The Varamin branch of Miras is situated within the courtyard of the congregational mosque (map), emphasizing its ongoing role in the preservation of local heritage (fig. 22).

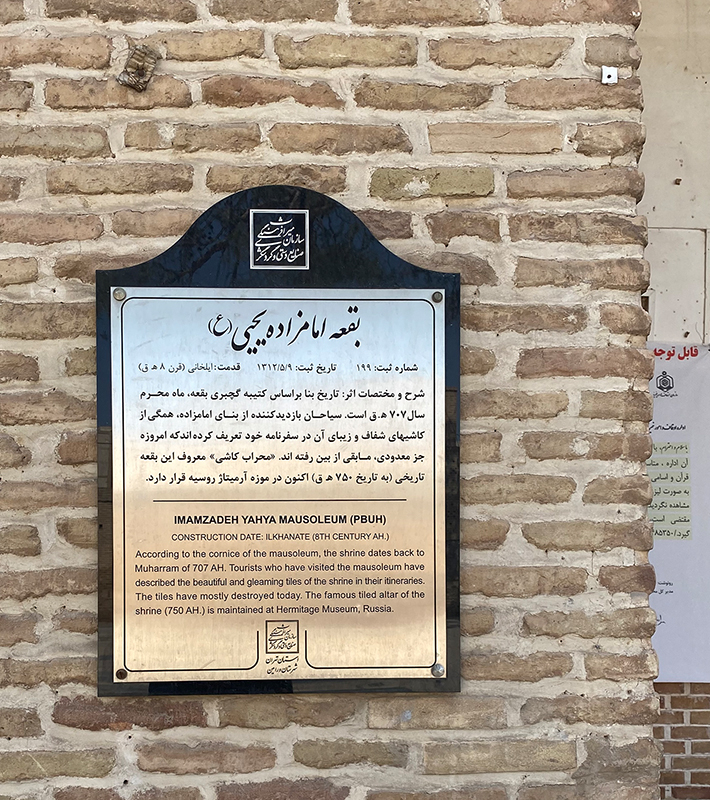

A Miras sign erected on the façade of the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya highlights the site’s original registration in 1312 Sh/1933 (figs. 23–24). This inscription was part of a much larger endeavour to preserve not just the brick and mortar of Iran but also the soul of its cultural heritage. In its simplicity, the sign reminds us that although much has been taken from the site, much still endures. It stands as a testament to the resilience of cultural heritage, the power of history, and the hope that, through preservation, we can safeguard the future.

Citation: Zahra Khademi, “History of Architectural Preservation in Iran and the Restoration of the Emamzadeh Yahya in 1361–63 Sh/1983–85.” Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.

Notes

Editor’s note: To facilitate accessibility and reading across audiences, we include transliterations, transcriptions, and translations of key organizations and architectural terms. We are grateful to colleagues who shared photographs of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s restoration reports. To contextualize these photographs from the early 1980s, see the Photo Timeline, History of Evolution, and Site Tour.

- A significant portion of the historical context presented at the start of this essay is derived from Galdieri and Afsar, “Conservation and Restoration of Persian Monuments.” ↩

- For this entire law see Nasiri-Moghaddam, “Archaeology and the Iranian National Museum,” 139–43.” ↩

- On IsMEO, the Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, see Panaino, “Italy xv. IsMEO.” ↩

- Memar News, “The Tribute Ceremony for Engineer Mohammad Hasan Moheb-Ali.” ↩

- Information provided by Hossein Nakhaei. ↩

- Information provided by Keelan Overton. ↩

Post-script: Practical resources

The Deputy of Cultural Heritage at the Ministry of Cultural Heritage, Tourism, and Handicrafts oversees four main offices, listed below. Researchers needing to contact the Ministry can click the links provided to access the names and contact details of the General Directors of each office.

- The General Office for Inscriptions of Natural, Tangible and Intangible Cultural Heritage (اداره کل ثبت و حریم آثار و حفظ و احیاء میراث معنوی و طبیعی)

- The General Office for the Preservation and Revitalization of Historical Buildings and Sites (اداره کل حفظ و احیاء بناها، محوطهها و بافتهای تاریخی)

- The General Office for Museum Affairs (اداره کل موزهها)

- The General Office of National and World Heritage Sites (مدیرکل امور پایگاههای میراث ملی و جهانی)

Additionally, there is the Research Institute of Cultural Heritage and Tourism, (پژوهشگاه میراث فرهنگی و گردشگری), which operates alongside the Ministry.

Bibliography

Primary

- Moheb-Ali, Mohammad Hasan, and Sazman-e Melli Hefazat-e Asar-e Bastani. Restoration reports for the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin, dated 1361 Sh/1982 (no. 1795), 1362 Sh/1983 (no. 1797), and 1363 Sh/1984–85 (no. 1801).

Secondary

- Galdieri, Eugenio, and Kerāmat-Allāh Afsar. “Conservation and Restoration of Persian Monuments.” Encyclopaedia Iranica, December 15, 1992, https://iranicaonline.org/articles/conservation-and-restoration-of-persian-monuments (updated October 28, 2011)

- Iranarchpedia, entry on the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin, https://iranarchpedia.ir/entry/14210

- Ishagh, Mohammad. Sokhanvaran Nami Iran dar Tarikh-e Iran. Tehran: Tolu, 1992. [Internet Archive]

- Memar News. “The Tribute Ceremony for Engineer Mohammad Hasan Moheb-Ali,” 23 Bahman 1295 Sh/11 February 2017, https://memarnews.com/مراسم-نکوداشت-مهندس-محمد-حسن-محب-علی/.

- Nasiri-Moghaddam, Nader. “Archaeology and the Iranian National Museum: Qajar and early Pahlavi cultural policies.” In Culture and Cultural Politics under Reza Shah, edited by Bianca Devos and Christoph Werner, 121–38. London: Routledge, 2014. [WorldCat]

- Panaino, Antonio. “Italy xv. IsMEO.” Encyclopaedia Iranica, December 15, 2007, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/italy-xv-ismeo-2#article-tags-overlay (updated April 5, 2012)