5Berlin, Germany

Tile in the form of an arch, possibly from a mihrab Iran, probably Kashan, 13th century Original building unknown Fritware molded, opaque white glaze, luster painting 11.26 × 10.67 × 1.65 in. (28.6 × 27.1 × 4.2 cm) Museum für Islamische Kunst, Berlin, 1900,26 Photograph © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Islamische Kunst / Christian Krug

This tile, which is now in the collection of the Museum für Islamische Kunst (Museum for Islamic Art) in Berlin but not on view, has traveled a long way in its history. Today, we think that it could come from a mihrab and was probably made in the workshops of Kashan. However, it took many decades for this attribution to be clarified, taking geographical diversions via Spain.

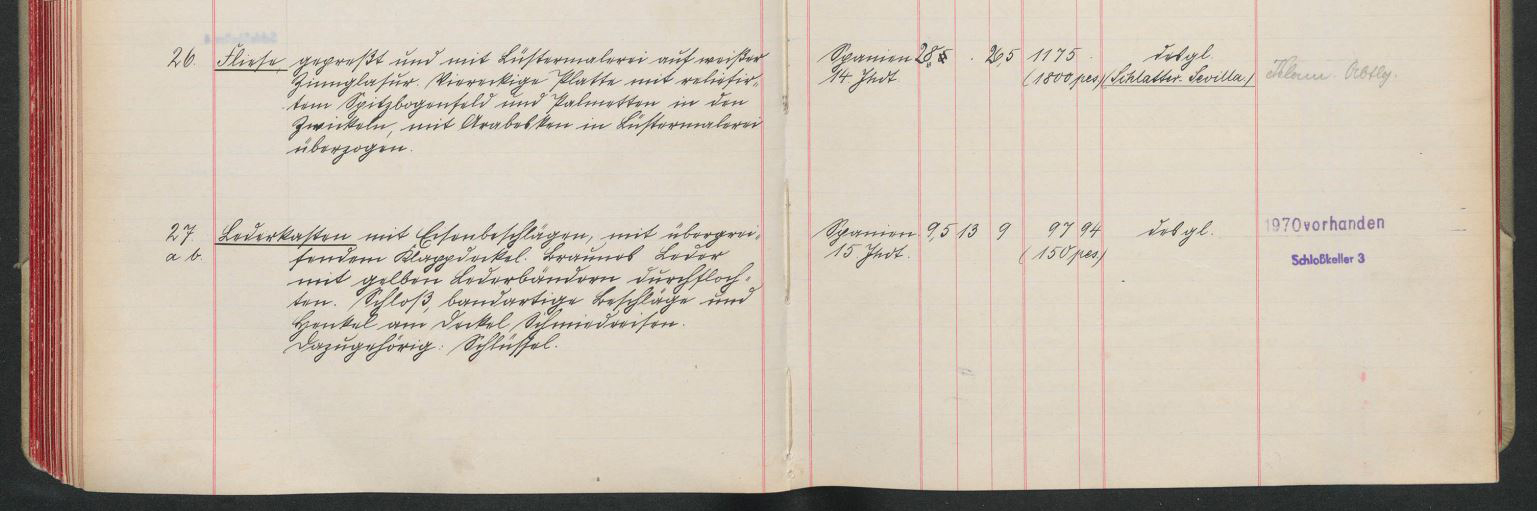

In the spring of 1900, Julius Lessing (d. 1908), director of the Kunstgewerbemuseum (Museum of Decorative Arts) in Berlin, traveled to Spain. According to the museum’s inventory records, Lessing acquired seven works of art in Seville from a person named Schlatter. The oldest of these objects was this tile, listed in the inventory log as ‘Tile, Spain, 14th century’ (fig. 1).

Transcription: Fliese, gepresst und mit Lüstermalerei auf weißer Zinnglasur. Viereckiger Platte mit reliefiertem Spitzbogenfeld und Palmetten in den Zwickeln, mit Arabesken in Lüstermalerei überzogen. Spanien, 14. Jahrhundert. 1800 Pesos, Schlatter, Sevilla

Translation: Tile, molded and with luster painting on white tin glaze. Square plate with pointed arch field in relief and palmettes in the spandrels, covered with arabesques in luster painting. Spain, 14th century. 1800 pesos, Schlatter, Seville

The pencil addition on the far right reads “Islam. Abtlg,” which means that it was transferred to the Museum für Islamische Kunst.

Three years later, Friedrich Sarre (d. 1945), the first director of the Berlin Museum für Islamische Kunst, published an article on Spanish luster ceramics. In it, Sarre first describes the famous Alhambra vases and then moves on to Spanish luster tiles. He observes a close stylistic relationship between the presumed ‘Spanish’ tile in Berlin and tiles in the Cuarto Real de Santo Domingo in Granada (map). He also comments on similarities between the gold luster of the tiles and believes the Spanish origin of the Berlin tile to be proven: “I consider that the presumed Persian origin of this tile can be ruled out” (Sarre 1903, p. 126).

Sarre’s successor, Ernst Kühnel (d. 1964), seems to have been less certain of this attribution. In 1927, the tile was included in an exhibition of Islamic art at the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague (map). In his review of the exhibition, Kühnel states, “It is not without reason that it has occasionally been claimed to be Persian, especially in view of the colour of the clay” (Kühnel 1927, p. 94). This Dutch exhibition also included a panel of star and cross tiles likely from the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin (information supplied by Suzanne Lambooy to Keelan Overton).

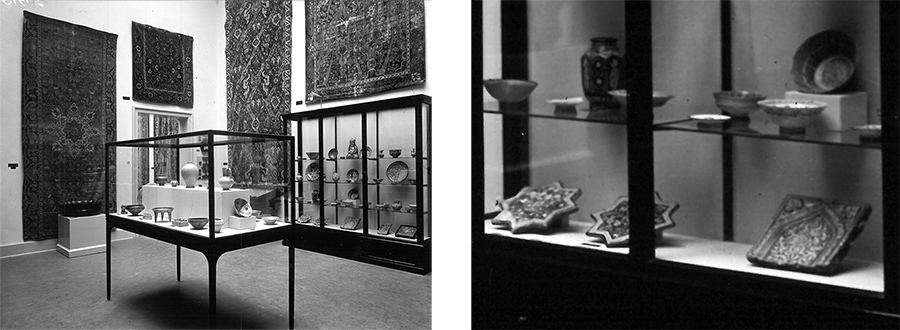

With the opening of the new permanent exhibition at the Pergamonmuseum in Berlin (map) in 1932, the tile entered the collection of the Museum für Islamische Kunst, one of three collections housed in the Pergamonmuseum. A photograph taken in early 1933 shows the tile with other Persian luster tiles and pottery in a single showcase (fig. 3). It looks like Kühnel, who was responsible for the new displays, wanted to emphasize his Persian attribution.

The winding path of the tile from Kashan to Seville to Berlin continued in the second half of the twentieth century. With the outbreak of the Second World War, it was removed from Berlin and taken to safety in a salt mine in Grasleben (Erduman-Çalış 2000, p. 302–7). After the end of the war, the tile was sent to the Zonal Fine Art Repository in Celle (Erduman-Çalış 2000, p. 307). We can follow its path in the ‘Islamic Art’ exhibition held in 1947 in Schloss Celle, a castle in Lower Saxony, where it was again titled ‘Spanish Tile from Malaga’ (Celle 1947, p. 22).

The tile then returned to divided Berlin in 1954. As it had been in West Germany after the war, it entered the Museum für Islamische Kunst in West Berlin. In 1967, director Klaus Brisch and curator Johanna Zick-Nissen prepared a new exhibition at Schloss Charlottenburg in Berlin. The accompanying catalog attributes the tile to Iran and dates it to the thirteenth century (Berlin 1967, no. 172). Some years later, in 1971, the Museum für Islamische Kunst moved to a new building in Dahlem, West Berlin, where the tile was again displayed (fig. 4).

During this time, the Pergamonmuseum in East Berlin housed the twin museum with Islamic artworks that had not been transferred to West Germany, including the luster mihrab from the Meydan Mosque in Kashan dated 623/1226 (I. 5366). With the reunification of the two German states in 1990, the two twin museums were reunited, and the collection was presented in a new permanent exhibition at the Pergamonmuseum, which opened in 2000.

Considering the long journey of this tile, two questions remain unanswered: How did the tile travel from Iran to Seville by 1900, and what was the role of the collector in Tehran who displayed it in his house in the 1880s (fig. 5)?

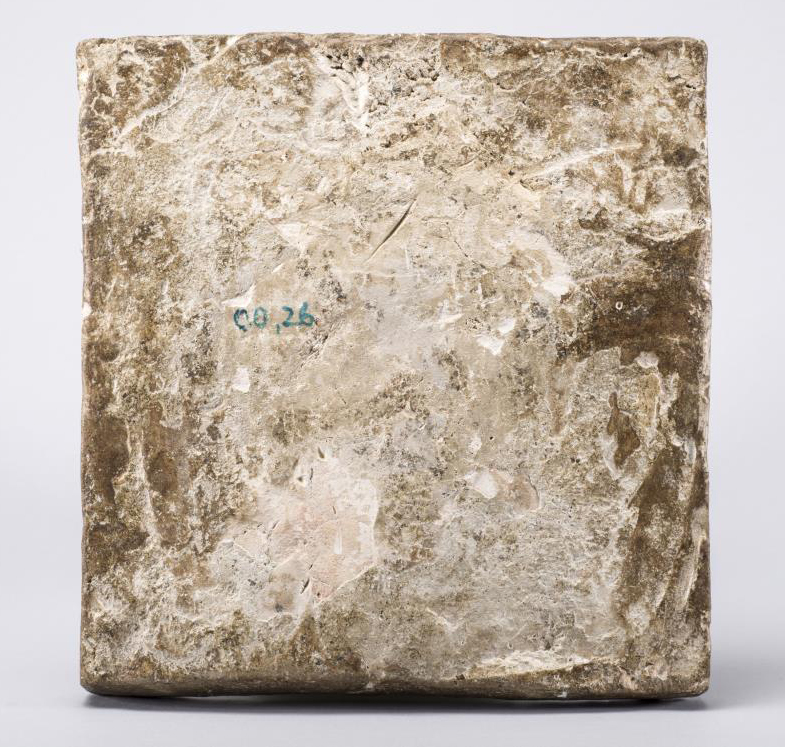

At the end of the nineteenth century, luster ceramics from Iran and Spain were equally sought after by collectors and museums in Europe and the United States (Masuya 2000). A well-organized network of national and international dealers ensured that the artworks were transported and sold to an interested clientele. Today, researchers around the world are trying to reconstruct the original contexts of tiles such as this one, whose original building remains unknown. Unfortunately, the back of this tile does not reveal any additional information, and the looters and dealers managed to cover their tracks, so more detective work is required (fig. 6).

Sources:

- Inventory log of the Museum für Kunstgewerbe Berlin, 1899–1900, https://storage.smb.museum/erwerbungsbuecher/EB_KGM-K_SLG_LZ_1899-1900.pdf

- “Islamische Kunst. Ausstellung des Museums für Islamische Kunst.” Schloss Charlottenburg (Langhansbau), Berlin, 1967. (exhibition catalog)

- Erdmann, Kurt. “Islamische Kunst.” Schloss Celle (Central Repository), 1947. (exhibition catalog)

- Erduman-Çalış, Deniz. Faszination Lüsterglanz und Kobaltblau. Die Geschichte Islamischer Keramik in Museen Deutschlands. München: Universitätsbibliothek der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, 2020. [LMU]

- Kühnel, Ernst. “Die Ausstellung islamischer Kunst im Haag.” Der Kunstwanderer (1926–27): 493–96.

- Masuya, Tomoko. “Persian Tiles on European Walls: Collecting Ilkhanid Tiles in Nineteenth-Century Europe.” Ars Orientalis 30 (2000): 39–64. [JSTOR]

- Sarre, Friedrich. “Die spanisch-maurischen Lüsterfayencen des Mittelalters und ihre Herstellung in Malaga.” Jahrbuch der Königlich Preussischen Kunstsammlungen 24, 2 (1903): 103–30. [JSTOR]

Citation: Deniz Erduman-Çalış, “Berlin, Germany: Tile in the form of an arch.” Luster cabinet entry in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.