2Location unknown

Two Iberian luster dishes

A (left)

Deep dish (brasero) with raised boss and possible coat of arms at center

Spain, Valencia region, late 15th–early 16th century

Earthenware with tin-glaze and luster decoration

B (right)

Round dish with ribbed boss and inscription

Spain, Valencia region, first half 16th century

Earthenware with tin-glaze and luster decoration

Spanish luster

It is surprising and intriguing to find two Iberian luster dishes at the top of this case, which otherwise displays examples of Iranian lusterware in Richard’s collection. Though we cannot see the details of their designs very clearly, we can see enough to assign them as productions of the Valencia region (map) in the late fifteenth or early sixteenth centuries. This is when the potteries of this region took over from the Islamic industry that had flourished under Nasrid rule (1232–1492) at the pottery center and port of Málaga. Now operating under the patronage of the Christian lords of Aragón, the scale of production and export truly exploded. Such vast numbers were exported to Italy that when Italian potters finally discovered how to make the technique of tin-glazed lusterware themselves, the bottom fell out of the Spanish market, and lusterware became a primarily local industry. It continued to be made into the eighteenth century, and on a small scale into the nineteenth century, when it was consciously revived in the spirit of national craft revivals (Rosser-Owen 2022b).

Large numbers of Iberian lusterware, spanning from twelfth-century Almohad production at Almería (map) to fifteenth-century Valencia wares, have also been found at Fustat in Egypt and other Eastern Mediterranean sites. Luster production in Egypt itself seems to have ceased by the end of the Fatimid period in 1171. Between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries, luster was only produced in a few centers in Syria and Iran [see Akbari’s essay here]. After that, it stopped altogether, due to the changing fashions caused by the influx of Chinese blue-and-white porcelain. Iberian imports, sent back to the lands where the luster technique had been invented, filled a gap when local taste outlasted local production (Rosser-Owen 2013).

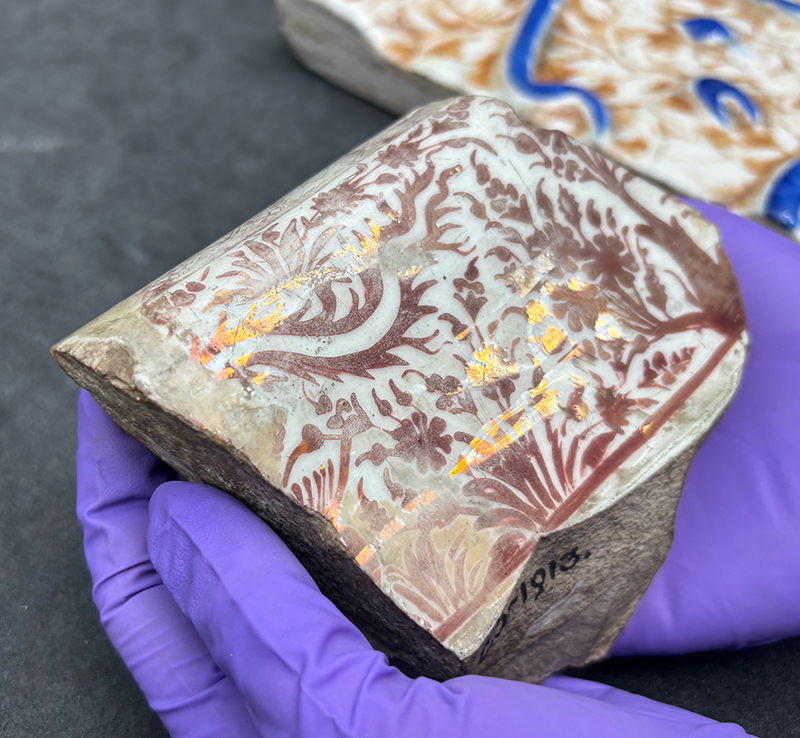

Unlike most lusterware made in the Middle East, Valencia lusterware was made with a deep red earthenware clay body and covered with a thick, opaque white tin-glaze that supported the luster decoration. This could develop a beautiful golden sheen, indicating high silver content in the luster pigment (as in fig. 1), or could be quite red, indicating that more copper than silver was used (as in fig. 2).

The later lusterwares tend to use increasing amounts of copper in their recipes, presumably because without their international export markets, the makers could not afford so much expensive silver (Dectot, Makariou and Miroudot 2008, p. 115). Their designs were predominantly vegetal, based on plant ornaments, and several patterns might be combined on a single vessel, as in dish A here. If they featured figurative decoration, this tended to be located on the dish’s reverse, indicating that, when not in use, they were probably displayed on a wall or credenza-like dresser with their reverses facing outwards (fig. 3). It is notable that most larger examples of Iberian lusterware have two small suspension holes in their rim. The presence of glaze inside these holes confirms that they were punctured before the vessels were fired, indicating that suspension and display were anticipated at the point of making.

The lack of figurative decoration associates this group of luster objects with the category of ‘Mudéjar’ art – a term coined in the nineteenth century to distinguish objects and buildings in an ‘Islamic’ style or technique from those that were perceived to be natively Spanish/Iberian. The term also implies that only someone who identified as ‘Muslim’ could have made or appreciated art in this style, when there are so many examples of this being far from the case. As such, it is a term that art historians of medieval Iberia do not like to use. Similarly, the term ‘Hispano-Moresque’ is going out of fashion. This was coined in 1861 by Baron Jean-Charles Davillier (1823–83), a French writer and collector who wanted to make a racial distinction between ‘Arab’ (‘Hispano-Arab’) and ‘Moor’ (‘Hispano-Moresque’), referring to the indigenous populations of North Africa who formed such a strong proportion of the Muslim population of al-Andalus (as Islamic Spain was called in Arabic) (Davillier 1861). Today, we prefer to be more historically specific in how we refer to particular types of artistic production and production centers (figs. 4–5).

Intersecting collecting histories

Interest in Iberian lusterware among collectors grew out of the collecting of Renaissance Italian tin-glazed wares known as maiolica, with which ‘Hispano-Moresque’ was often confused (Rosser-Owen 2022a). Early connoisseurs found it difficult to tell them apart, until scientific research at Sèvres in the 1840s identified the Spanish origins of one class of ware. One reason for this confusion seems to have been that many of the earliest examples of Valencia lusterware to be collected were acquired in Italy. By the 1850s, when the V&A started to collect Iberian lusterware, there were already several pre-existing private collections on which they could draw, in particular those of Jules Soulages (1812–56) and Ralph Bernal (1783–1854). The collecting of ‘Hispano-Moresque’ therefore preceded the collecting of Persian lusterware by several decades.

Until the V&A’s systematic collection of Persian luster in the 1870s and 1880s, examples of this ware were rare among British collectors, though they were better known in France (Carey 2017). Again, there was poor understanding of the differences between the ceramic traditions, and it was not uncommon to find them displayed together or for ‘Hispano-Moresque’ wares to be described as ‘Persian’ (Vanke 1999, p. 221). This is shown by the tile discussed here by Deniz Erduman-Çalış, which was acquired in Spain and therefore considered to be an example of Nasrid luster until well into the twentieth century.

Where did Jules Richard acquire these dishes?

As Moya Carey has discussed, Jules Richard enjoyed “a successful second career as an art dealer” (Carey 2017, p. 107). His French connections could have enabled him to buy these dishes on the Paris art market. On the other hand, it is plausible that he could have acquired them in Iran. We know that Iberian lusterware was exported to Iran during the Nasrid period. Ibn al-Khatib (1313–75), vizier at the Nasrid court in Granada, boasted that “Málaga lustered pottery is such that all countries clamor for it, even the city of Tabriz,” referring to one of the Timurid (ca. 1370–1507) capitals in northwest Iran (Rosser-Owen 2022b, p. 127–28). Though lusterwares are not mentioned among the diplomatic gifts brought to Timur by Ruy González de Clavijo in the early fifteenth century (Simpson 2024, p. 184–92), this was just when Valencia was starting to surpass Nasrid Málaga in luster production. It is therefore possible that members of Clavijo’s party (although originating in Castile, rather than Aragón) brought examples of these fashionable new wares with them, as personal possessions or to trade.

Contacts between Iran and the Iberian Peninsula continued through diplomatic channels as well as global trading networks, in particular those of the Genoese (García Porras and Fábregas 2010), and it is not unlikely that examples of Valencia lusterware found their way to Iran. Material evidence of this contact exists in the examples of Central Asian cloth of gold found inside the tombs of the Castilian royal pantheon of Las Huelgas in Burgos (map). One particularly spectacular example, from the tomb of Alfonso de la Cerda (d. 1333), has Genoese commercial stamps on it (Herrero Carretero 2004).

As mentioned above, the production of luster within Middle Eastern centers was declining, and by the fifteenth century, the Iberian Peninsula was the only place in the world making lusterwares, apart from possible small-scale production under the Timurids. It has even been suggested that the export of Valencia lusterwares to Iran might have inspired Safavid (1501–1722) potters to revive the use of luster to decorate their own ceramics (Dectot, Makariou and Miroudot 2008, p. 107–9) (fig. 6).

Could Jules Richard have come across these Valencia wares in a collection in Iran? Though this is plausible, sadly we will probably never know.

Where are they now?

So far, we have not been able to trace the present whereabouts of these two dishes. Valencia lusterwares were produced on a massive scale, and their decoration is often generic and repetitive. In terms of what we can tell from Sevruguin’s photograph, dish A appears to be a brasero, the kind of deep-sided dish like an example in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (fig. 7). The way the shadow falls in the photograph implies a deep dish, as does the narrowness of its rim. It is also decorated with ‘gadrooning,’ a very common device on the Valencia lusterwares, executed in slight relief, probably by being placed in a mold, and a bit like repoussé in metal objects. There is a raised boss at the center of the dish with a device that cannot be clearly read. This is likely a coat-of-arms and could be a generic design or identify the patron for whom the dish was originally made. Surrounding this boss are three or possibly four bands of different designs, which are difficult to see clearly in the photograph (for a detail of such bands, see fig. 4).

Dish B has a more distinctive design (fig. 8). The ribbed boss at the center is unusual, as is the way the inscription is placed across the dish, in a wide open V form. It is not possible to see what the inscription reads, though this is most probably a Christian text or pseudo-text. Inscriptions such as ‘Ave Maria Gratia Plena’ (Hail Mary Full of Grace), or the first lines of St John’s Gospel (‘In the beginning was the word’), were quite common on Valencia lusters (fig. 9). The use of Latin inscriptions as pattern reflects the earlier use of Arabic or pseudo-Arabic inscriptions and shows the continued legacy of Islamic art on these objects, although inscriptions were never very common on Iberian lusterware. The spaces between the inscription bands in dish B are filled with spiky plant motifs, and the dish’s rim has double gadrooning. A dish with some similar characteristics is again found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (see fig. 8).

Having identified these key characteristics, we started to look for matches and have found many objects with very close designs, but nothing exact. Given the number of objects from Richard’s collection now in the V&A collection, thanks to the systematic purchases of Robert Murdoch Smith (Carey 2017), we started with the Iberian lusterwares in this museum, which are fortunate to have a catalogue raisonné written by Antony Ray (Ray 2000). They were not to be found, and this is not surprising given that the V&A collection of Spanish lusterware was already comprehensive by around 1880 (Rosser-Owen 2022a). Next, I checked the other great international collections of Spanish luster—the Musée de Cluny in Paris (see fig. 3), Instituto Valencia de Don Juan in Madrid, Museo Nacional de Cerámica González Martí in Valencia, and Hispanic Society of America in New York—but did not find them there. We have also searched publications, photographs, and online collections of the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyon, British Museum and Courtauld Gallery in London (fig. 9), Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), and Manufacture et Musée Nationaux de Sèvres (see figs. 4–5). In all cases, however, our search was not exhaustive.

Richard’s remaining collection was exhibited in Paris at the Exposition Universelle of 1889, and from there much of it appears to have passed into the hands of Parisian dealers. Since most of the older European institutional collections had already been formed by then, it is plausible that the dishes entered an American collection at the turn of the twentieth century. William Randolph Hearst (1863–1951), for example, had acquired at least 300 lusterware objects by 1907, though he was selling off his collection by the 1930s (personal communication from Cristina Aldrich). Private collections often changed hands, and some of Hearst’s lusterware ended up in Doris Duke’s (1912–93) Honolulu home known as Shangri La, including one piece (48.112) similar to dish A here.

We hope that by drawing attention to these two objects from Richard’s collection someone out there will recognize them and help to fill in the later stages of their stories.

Sources:

- Carey, Moya. “Diplomats and Dealers: the Approach to Persian Art in 1876.” In Persian Art: collecting the arts of Iran for the V&A, idem, 69–117. London: V&A Publishing, 2017.

- Davillier, Jean-Charles. Histoire des faïences hispano-moresques à reflets métalliques. Paris: Librairie Archéologique de Victor Didron, 1861. [BnF Gallica]

- Dectot, Xavier, Sophie Makariou, and Delphine Miroudot. Reflets d’or: d’Orient en Occident: la céramique lustrée, IXe-XVe siècle. Paris: RMN, 2008.

- García Porras, Alberto, and Ádela Fábregas. “Genoese Trade Networks in the Southern Iberian Peninsula: Trade, Transmission of Technical Knowledge and Economic Interactions.” Mediterranean Historical Review 25, 1 (2010): 35–51 [Digibug]

- Herrero Carretero, Concha. “Marques d’importation au XIVe siècle sur les tissus orientaux de Las Huelgas.” Bulletin du CIETA 81 (2004): 41–47.

- Ray, Anthony. Spanish Pottery 1248-1898: with a catalogue of the collection in the Victoria and Albert Museum. London: V&A Publications, 2000.

- Rosser-Owen, Mariam. “‘From the mounds of Old Cairo’: Spanish ceramics from Fustat in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum.” In Actas del I Congreso Internacional Red Europea de Museos de Arte Islámico, edited by Jesús Bermúdez et al, 163–87. Granada, Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife, 2013. [Alhambra-Patronato]

- Rosser-Owen, Mariam. “‘The only Art Pottery worthy of the name’: Collecting Spanish lustreware by the Victoria and Albert Museum (1851-1921).” In Collecting Spain: Collecting Spanish Decorative Arts in Britain and Spain, edited by Ana Cabrera Lafuente and Lesley E. Miller, 89–117. Madrid: Ediciones Polifemo, 2022. [2022a]

- Rosser-Owen, Mariam. “The consumption and reception of Iberian lustreware: medieval to contemporary.” In Lüsterkeramik: Schillerndes Geheimnis / Luster Ceramics: Shimmering Secret, edited by Miriam Kühn and Martina Müller-Wiener, 126–43. Petersberg: Michael Imhof Verlag, 2022. [2022b]

- Simpson, Marianna Shreve. “Gift-giving between Iran and Iberia from Timur to Tahmasp.” In Iranian Art from the Sasanians to the Islamic Republic: Essays in Honour of Linda Komaroff, edited by Sheila S. Blair, Jonathan M. Bloom, and Sandra S. Williams, 184–208. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2024.

- Tolar, Tanja. “A Spanish Lustre Dish.” Illuminating Objects Blog, The Courtauld Gallery, https://sites.courtauld.ac.uk/illuminating-objects/illuminating-objects-home/spanish-lustre-dish/

- Vanke, Francesca. “The contribution of C.D.E. Fortnum to the historiography and collecting of Islamic ceramics.” Journal of the History of Collections 11, 2 (1999): 219–31.

With particular thanks to Cristina Aldrich, Keelan Overton, and Sandra Williams.

Citation: Mariam Rosser-Owen, “Two Iberian luster dishes.” Luster cabinet entry in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.