From Varamin to Honolulu: The Displacement, Commodification, and Aestheticization of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s Luster Mihrab, 1863–2025

Keelan Overton and Hossein Nakhaei

Contents:

- Introduction

- Chapter One (Displacement): 1863–1912

- Chapter Two (Commodification): 1912–35

- Chapter Three (Aestheticization): 1937–2025

- Conclusion and Bibliography

Chapter Two (Commodification): 1912–35

This chapter considers Hagop Kevorkian’s purchase of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab from Mostowfi al-Mamalek in 1912–13 and the dealer’s purveying, commodification, and display of the ensemble in international events and cities, including in the United States.

1912–13: New York, Tehran, Paris

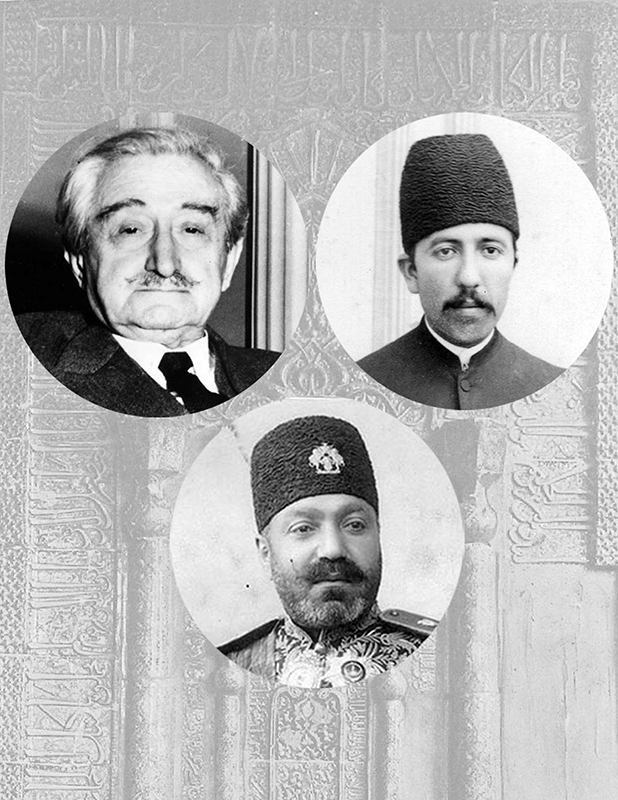

In the wake of Kevorkian’s exhibitions in Paris, London, and New York, the dealer learns of another major luster ensemble now available for purchase: the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab. Hearing that Mirza Hasan Khan Ashtiani Mostowfi al-Mamalek, now Minister of War, has been granted permission to “dispose of the monument” (Kevorkian’s words in August 1913 to American collector Charles Lang Freer), the dealer travels to Iran in October 1912 to begin negotiating its acquisition.104 His efforts are in vain, because the price is too high.

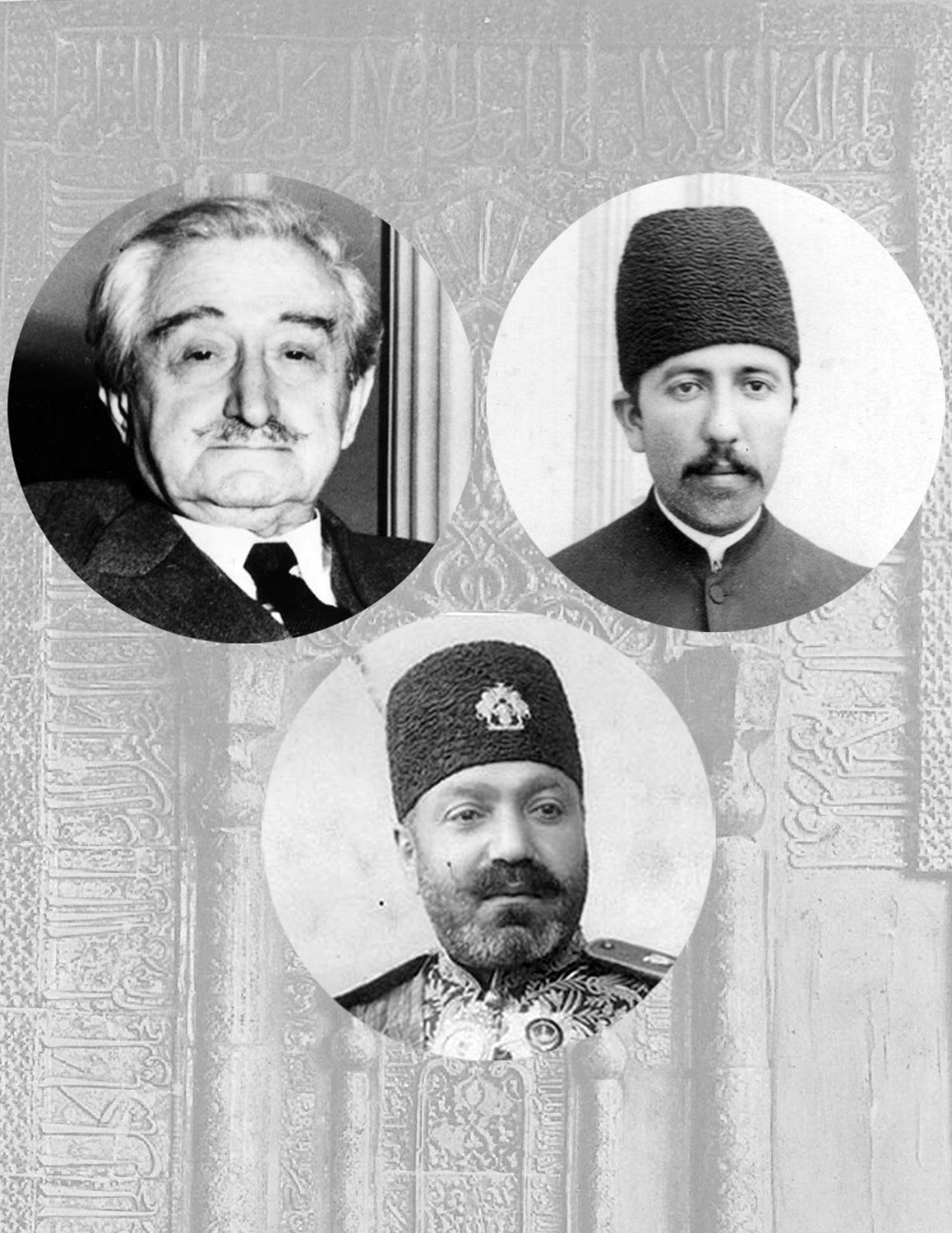

Mostowfi al-Mamalek then travels to Europe, and one purpose of his mission is apparently to convince “the Regent” to return to Iran. The individual in question is Abolqasem Khan Naser al-Molk (d. 1927), who was appointed regent to Ahmad Shah (r. 1909–25) in 1911 but, from 1912 onward, carried out his duties from Europe via telegraph. This political situation presents Kevorkian with an opening to curry favor with Mostowfi al-Mamalek and gain leverage for the mihrab’s acquisition: “In this connection and on account of my excellent relations with the Regent himself, I rendered services that have been appreciated by His Excellency [Mostowfi al-Mamalek] and in return he conceded the monument [mihrab] to me at a price for which it would have been impossible to obtain it.”105 Kevorkian’s narrative seems to accord with fact, for he owns the mihrab by at least 25 August 1913 and Naser-al-Molk returns to Iran in September, apparently “after repeated pleas from members of the Cabinet and other officials.”106

“In this connection and on account of my excellent relations with the Regent himself, I rendered services that have been appreciated by His Excellency [Mostowfi al-Mamalek] and in return he conceded the monument [mihrab] to me at a price for which it would have been impossible to obtain it.”

Kevorkian’s account underscores that his acquisition of the mihrab—which occurred in concert with London retailer Debenhams Limited (jump ahead to May 1914)—rested on his personal connections and political maneuverings in Paris, a city that remained central to the Qajar court’s operations abroad.

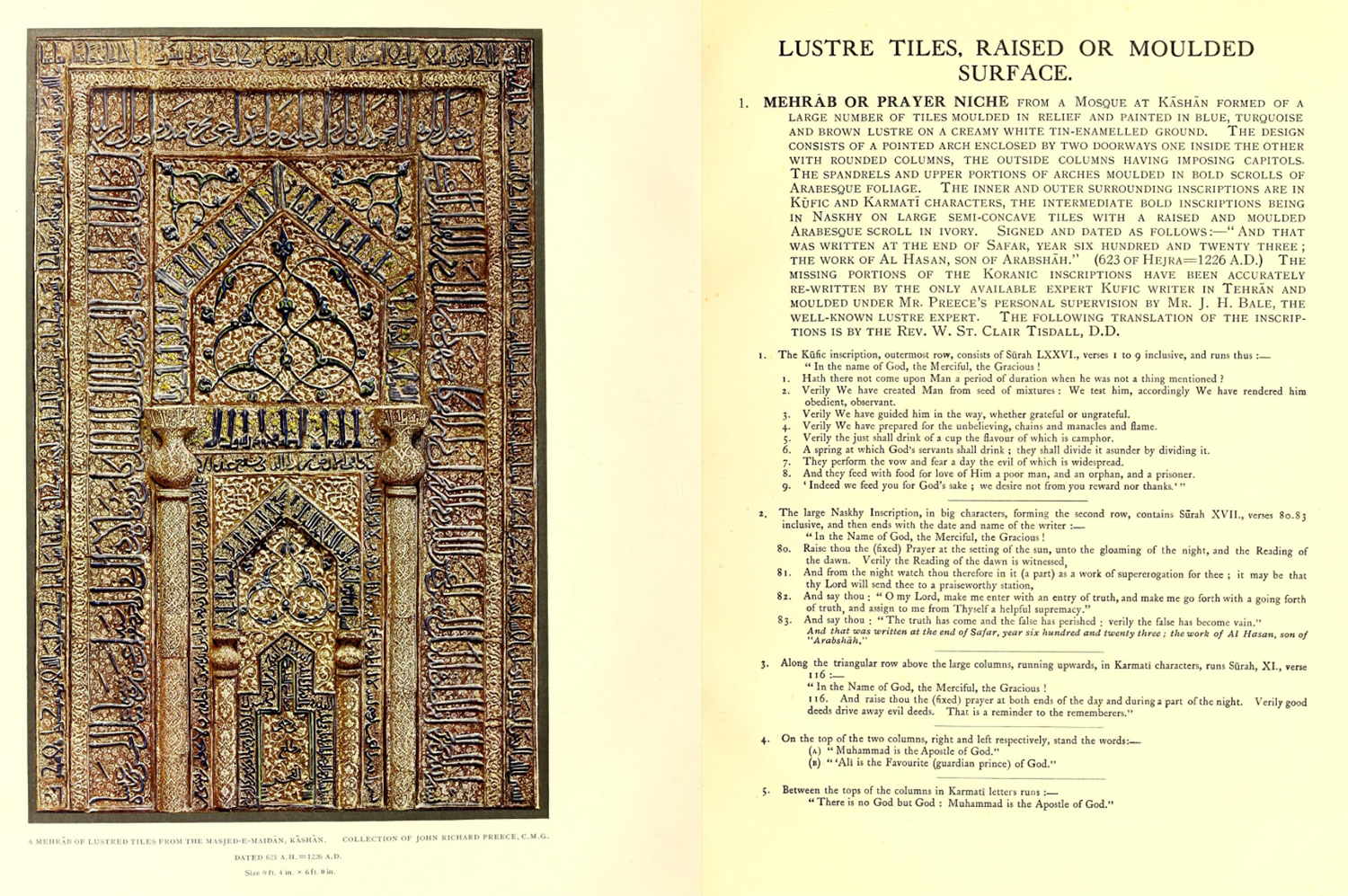

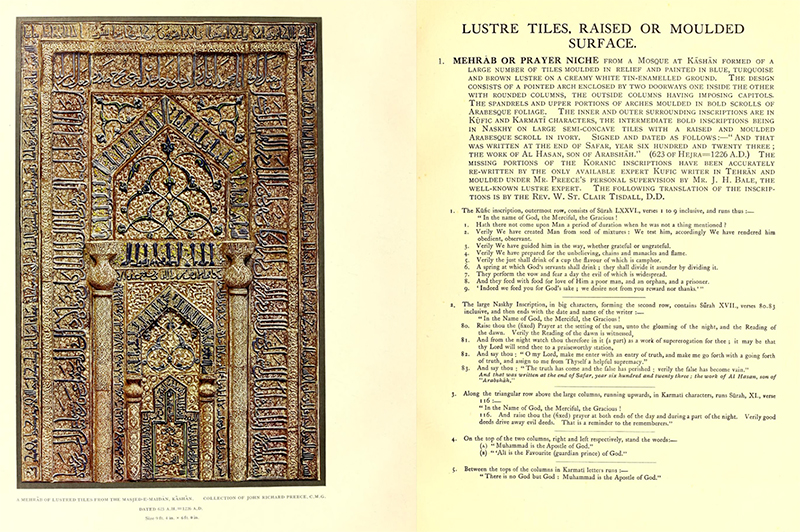

May 1913: London

While Kevorkian acquires the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab privately from Mostowfi al-Mamalek, the mihrab from Kashan’s Masjed-e Meydan (or Masjed-e Mir ʿEmad, map), which had been photographed in situ by Dieulafoy in 1881 (see fig. 29), is offered as the highlight in the Preece collection sale at Vincent Robinson galleries in London (map), just north of Kevorkian’s Persian Art Gallery (map) (fig. 73). John Richard Preece (d. 1917))—a British employee of the Indo-European Telegraph Department in Iran, who later served as British Consul at Esfahan and then General Consul—had acquired the mihrab around 1897.107 The removal and export of the Masjed-e Meydan’s mihrab coincided roughly with the displacement of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab, and as we shall see, their purveying would continue to overlap.

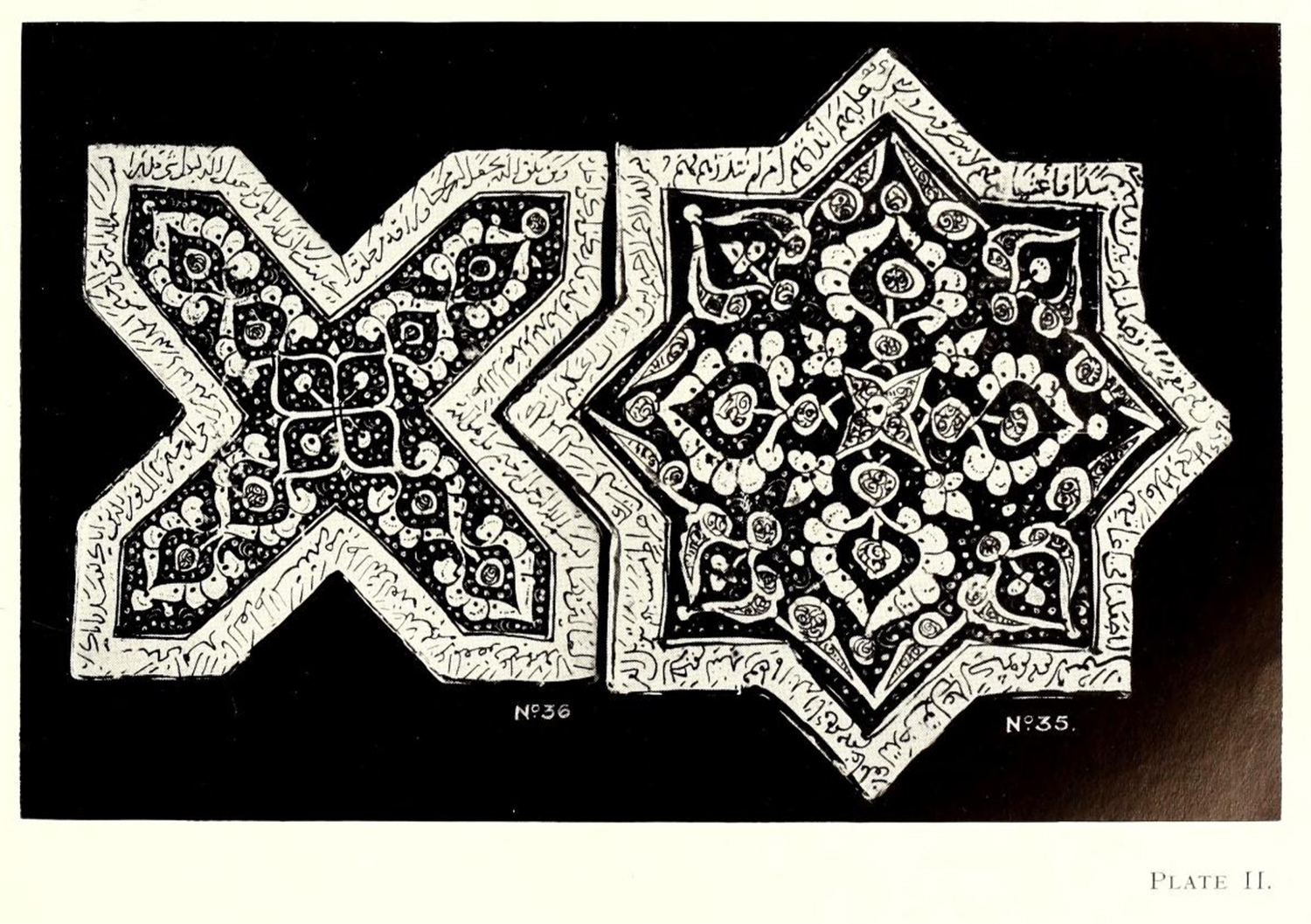

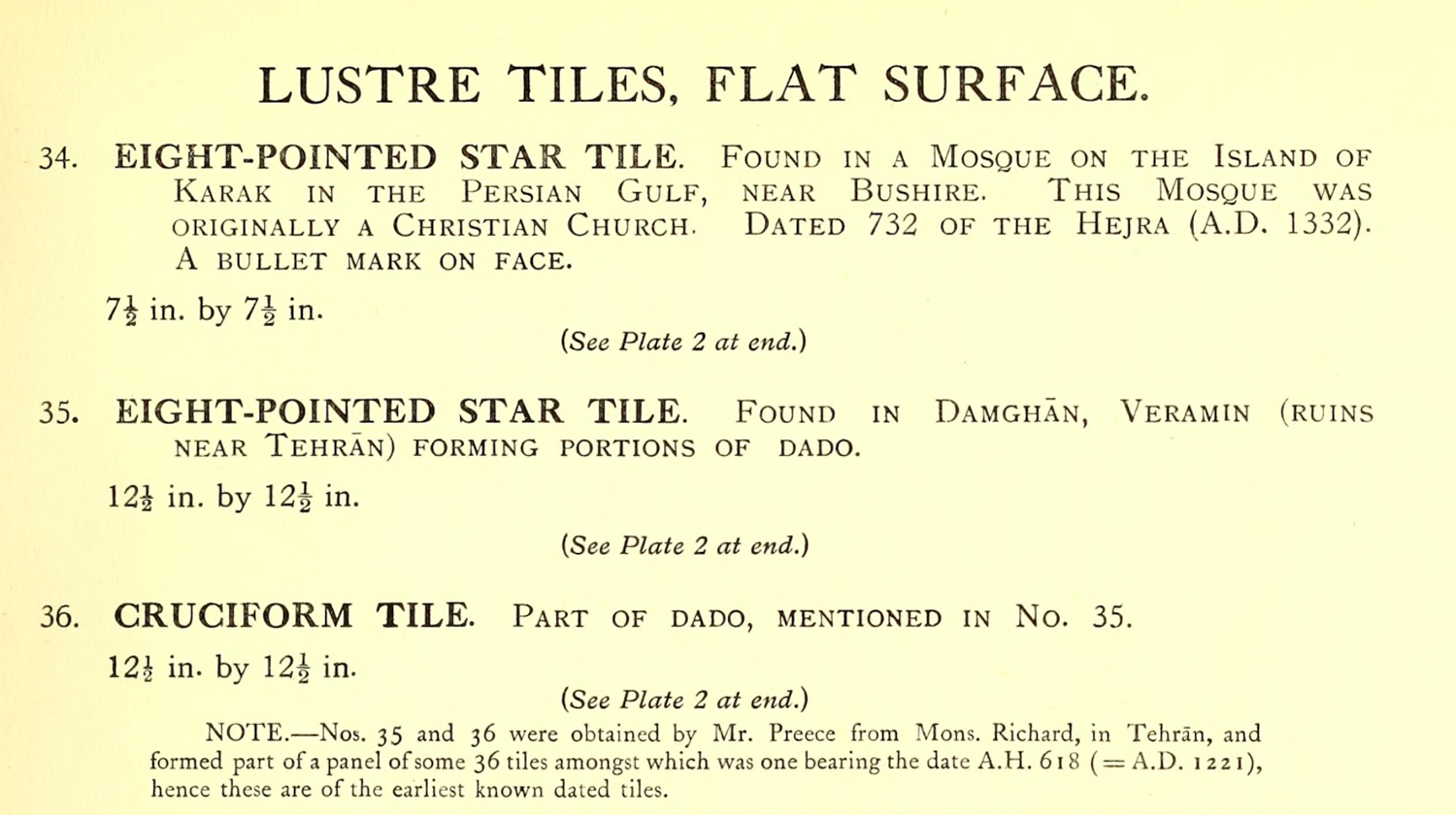

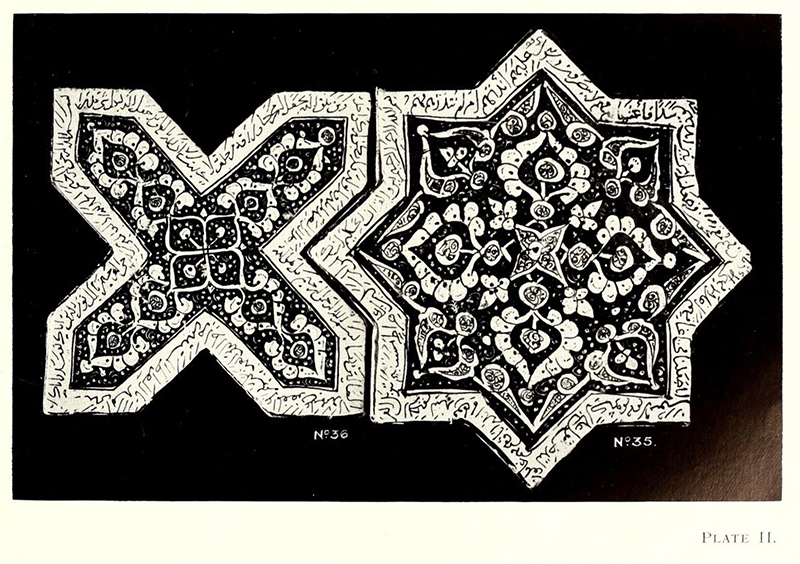

The Preece sale also includes two star and cross tiles from the Emamzadeh Yahya that are described as “found in Damghān, Veramin (ruins near Tehrān)” and “obtained by Mr. Preece from Mons Richard, in Tehran” (figs. 74–75).108 Instead of identifying the source building, the entry names another city—Damghan—that is nearly 200 miles northeast of Varamin (map).109 This careless approach to architectural origin is contrasted to the accurate attention to provenance (past ownership), and specifically the dealer Jules Richard (see 1875–76). Naming Richard undoubtedly served to lure buyers and increase the tiles’ monetary value.

August 1913–February 1914: London, Paris, Tehran, Detroit, at Sea

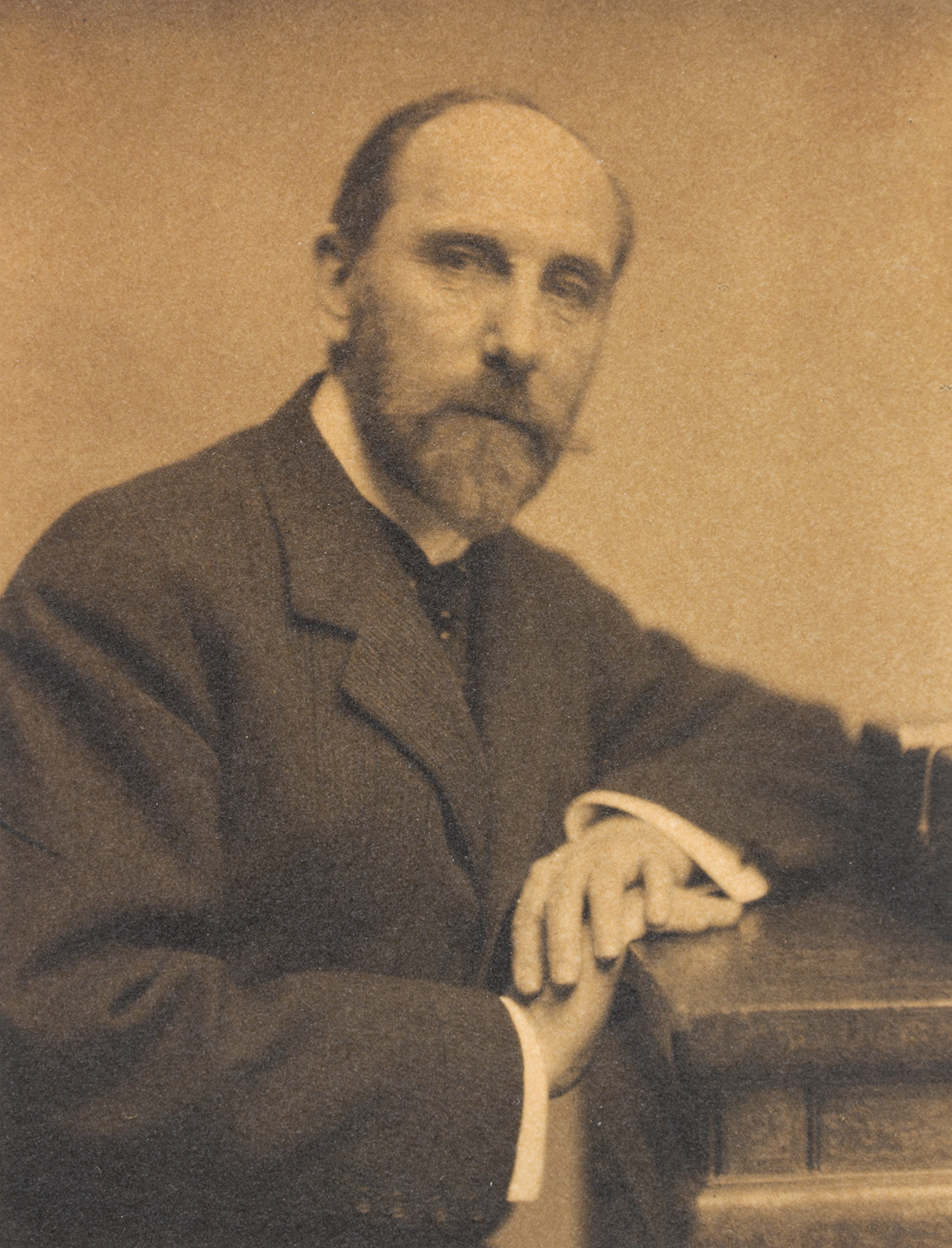

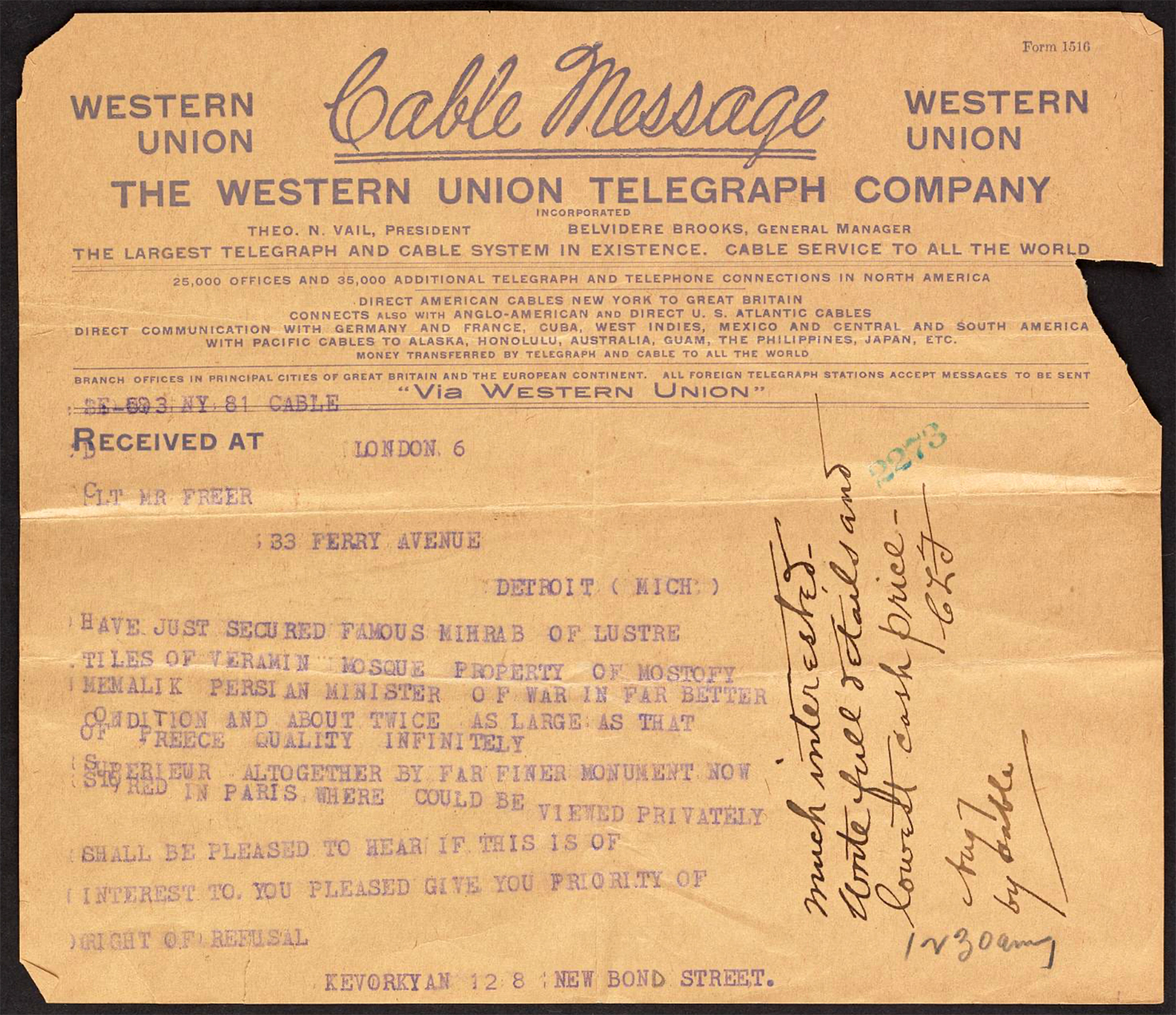

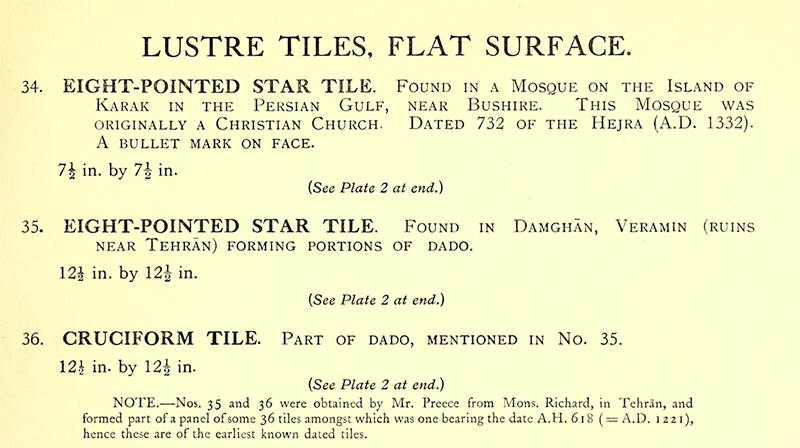

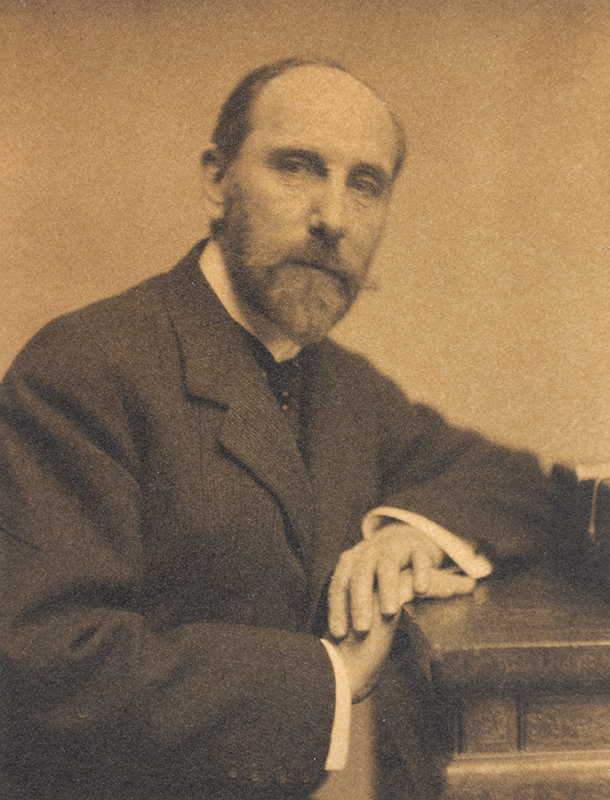

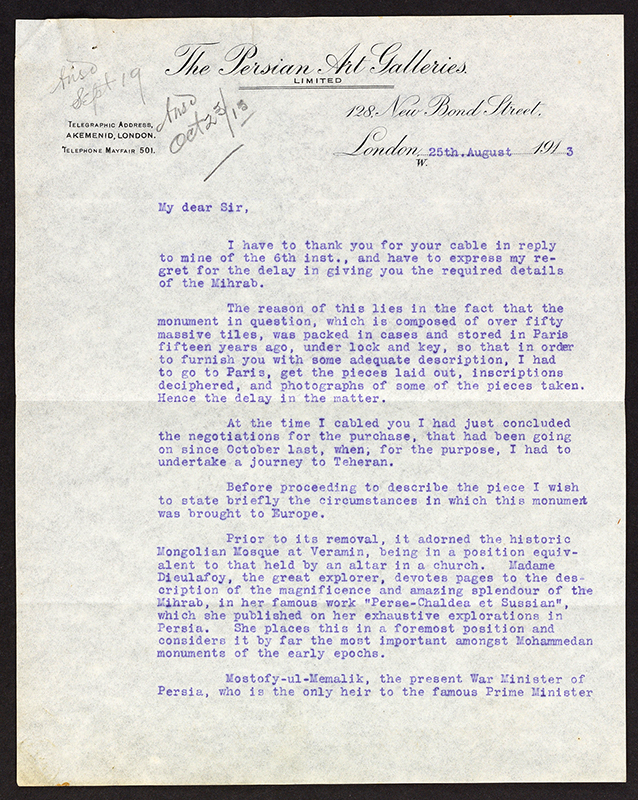

Shortly after concluding his negotiations with Mostowfi al-Mamalek, Kevorkian offers the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab for sale to Detroit-based industrialist and collector Charles Lang Freer (d. 1919) (fig. 76). He first reaches out to the collector from London via telegram (fig. 77):

Have just secured famous mihrab of lustre tiles of Veramin mosque property of Mostofy Memalik [Mostowfi al-Mamalek] Persian Minister of War in far better condition and about twice as large as that of Preece [see fig. 73] quality infinitely superieur altogether by far finer monument now stored in Paris where could be viewed privately shall be pleased to hear if this is of interest to you pleased give you priority of right of refusal.

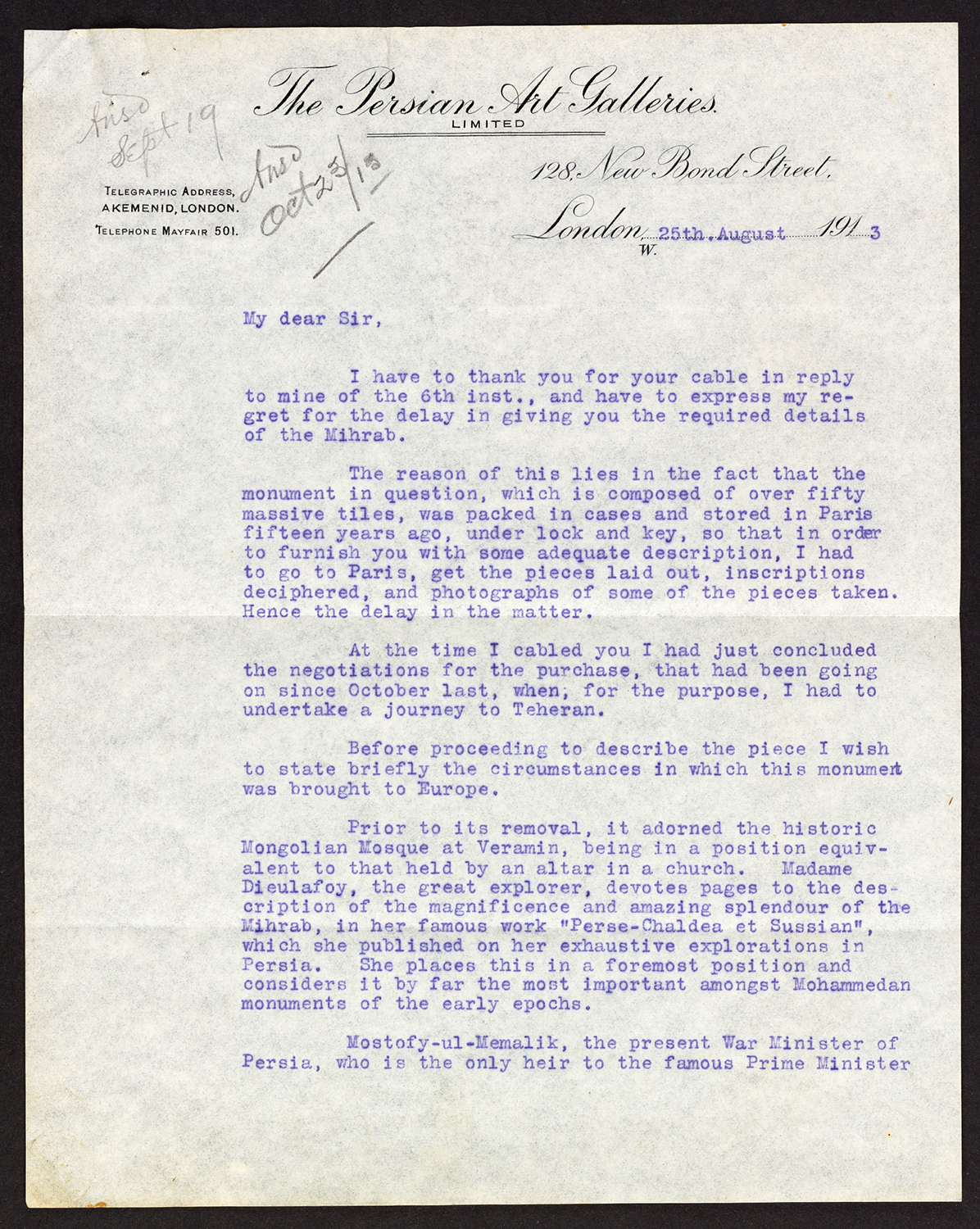

A few weeks later from Paris, Kevorkian sends Freer a six-page letter about the mihrab accompanied by fifteen-pages of translations of its inscriptions. He describes its architectural setting and refers back to Jane Dieulafoy (fig. 78):

Prior to its removal, it adorned the historic Mongolian Mosque at Veramin, being in a position equivalent to that held by an alter in a church. Madame Dieulafoy, the great explorer, devotes pages to the description of the magnificence and amazing splendour of the mihrab, in her famous work [La Perse; see 1887]. She places this in a foremost position and considers it by far the most important amongst Mohammedan monuments of the early epochs.

Kevorkian’s description of the mihrab as from the “Veramin mosque” echoes earlier amorphous language and is notable given his awareness of Dieulafoy’s La Perse, which named the Emamzadeh Yahya relatively clearly (“Imamzaddé Yaya”). It is unclear if Kevorkian misunderstood the source building, deliberately obscured the Emamzadeh Yahya, or simply preferred the term ‘mosque,’ presuming it would be more familiar to foreign buyers. Regardless, the dealer’s failure to name the Emamzadeh Yahya marked a major step backward in the mihrab’s understanding as an architectural element from a very specific building. His reference to the “historic Mongolian Mosque” might have also led Freer to think that the mihrab came from the city’s congregational mosque, which was becoming increasingly more known abroad through publications like Sarre’s Denkmäler Persischer Baukunst of 1901. He also leans on Dieulafoy’s admiring remarks—although she was not a specialist in the so-called “Mohammedan” art—to bolster the mihrab’s market value.

Kevorkian next explains the mihrab’s recent history and connection to Mostowfi al-Mamalek (fig. 79):

Mostofy-ul-Memalik, the present War Minister of Persia, who is the only heir to the famous Prime Minister [Mirza Yusof Ashtiani, d. 1886] to Nasr-ed-Din Shah [Naser al-Din], and whose ancestors for centuries held the same exalted position, owned large tracts of land including the sites of the ancient city of Veramin and all the villages at present left standing. He brought the Mihrab to Paris with a view to exhibiting it at the universal exposition of Paris of 1899 [sic, 1900], with the result that he was disgraced and degraded by the late Shah [Mozaffar al-Din, d. 1907] for this act and further was prevented from exhibiting at the exposition inconsequence [added in handwriting] of a communique made through the Persian Legation.110

Kevorkian describes Mostowfi al-Mamalek’s price as “not less than a million francs” ($192,654) and notes how “Mr. Homberg,” the French banker who owned two removed tiles (see 1903) had offered 400,000 [French] francs (€15,849 or $77,061).111 He continues:

The Shah would not forgive Mostofy until he solemnly undertook not to dispose of the secret monument, whereupon he was permitted to enter Persia and accordingly did so. But the monument was mortgaged and could not be released, except by payment of a heavy sum of money and therefore it was left in store in Paris under lock and key. On the death of the Shah [3 January 1907] and the ultimate substitution of a constitutional regime, His Excellent Mostofy-ul-Memalik, having played an important role, was called to fill the post of Prime Minister at a most difficult moment, and the great Mushtahid (the religious authority) [mojtahed] who was the herald of the Constitution [see 1907], in return for the services of Mostofy and his gifts of land which he bequeathed to the Imamzades of Veramin, authorized him to dispose of the monument in question.112

Kevorkian explains how he went to Tehran in October 1912 to begin negotiations and that he was ultimately successful thanks to his interventions with the Regent. He mentions sending Freer photographs in a separate parcel, including one taken “in Persia soon after the piece was removed from the Mosque and temporarily set.”113

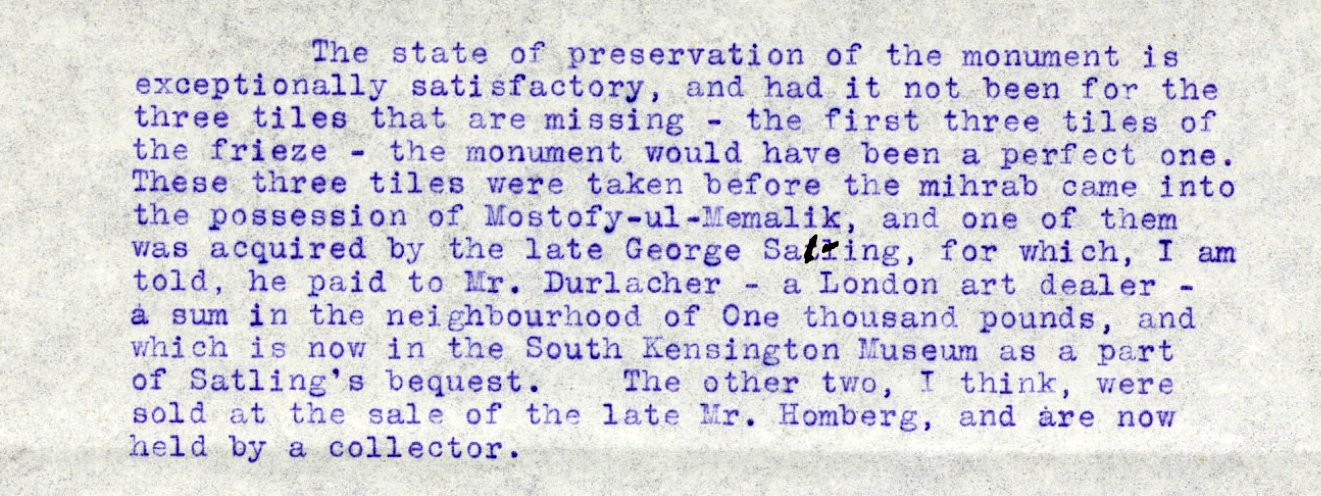

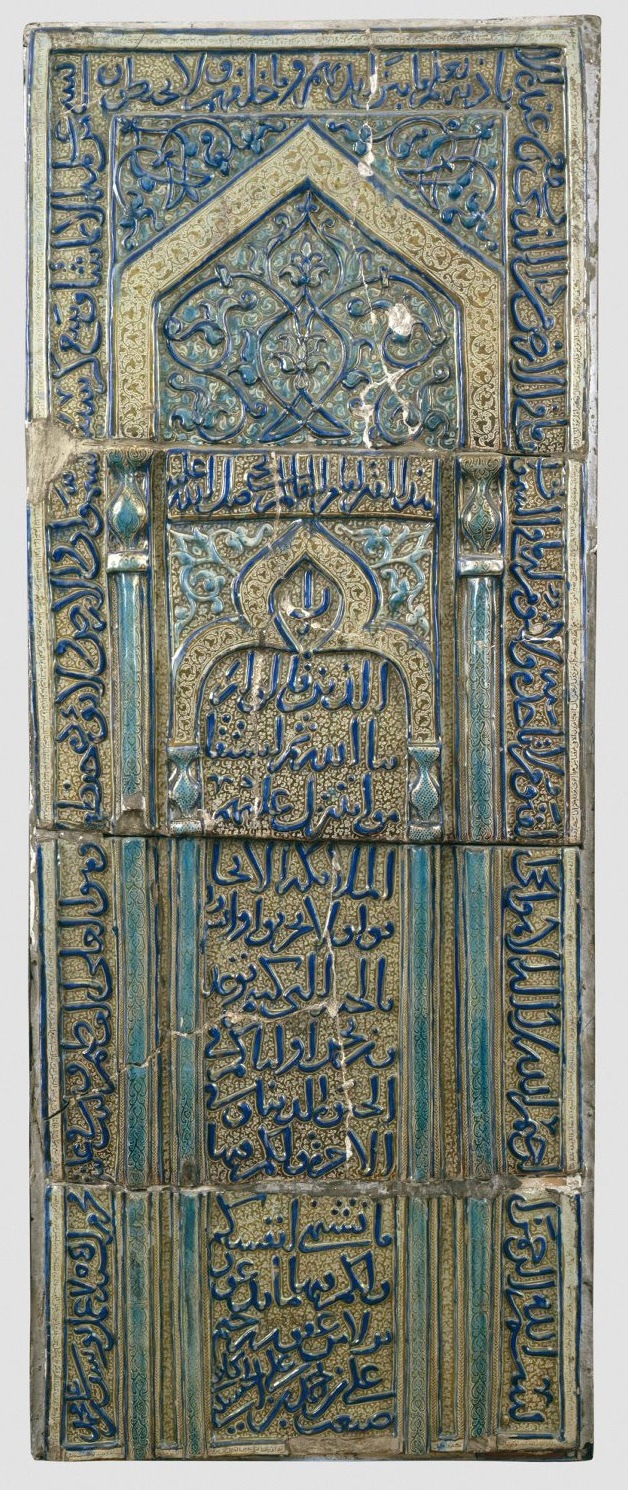

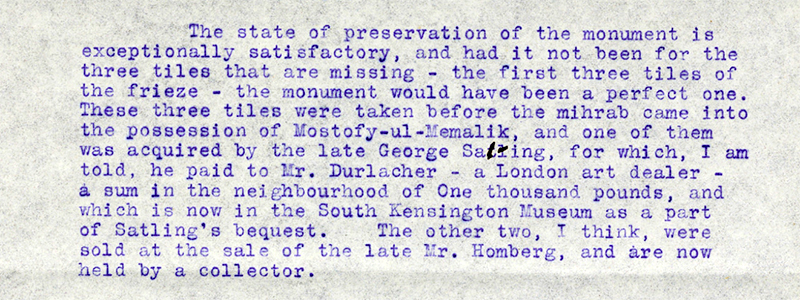

Kevorkian is highly complimentary of the mihrab’s glazes, relief, and calligraphy—“so perfect an achievement”—and describes the mihrab’s condition as “extremely satisfactory.” He references only three missing tiles: “the first three tiles of the frieze.” In fact, four were missing from this border, and others were missing from the inner portion (see 1875; jump ahead to 2025). The dealer mentions that the border tiles had been taken from the ensemble before it was acquired by Mostowfi al-Mamalek, a point that seems possible per other removed tiles. According to Kevorkian, George Salting (d. 1909) acquired one of the tiles from London dealer “Mr. Durlacher” (Henry and George Durlacher, the Durlacher Brothers) and it had entered the South Kensington Museum as part of Salting’s bequest (fig. 80).114 He thinks that the other two tiles were sold at the sale of the Octave Homberg Sr. (d. 1907) and were acquired by another collector.115

Kevorkian offers Freer a price of £16,000 ($77,792), citing the fact that Freer’s “generous gift” (his 1906 endowment of his collection to the Freer Gallery of Art) will ultimately serve “public education.” If the collector declines, he will market the mihrab for £20,000 ($97,240).116 Kevorkian notes that he will be heading to Iran for two months and that Freer can communicate with his firm in London. He concludes that any comparison between the “Veramin Mihrab” and the other luster mihrab presently exhibited at Vincent Robinsons (from the Masjed-e Meydan in Kashan, see 1881 and 1913) is an “absurdity.”117

Upon receiving Kevorkian’s letter and image of the mihrab, Freer responds that he would like to examine the piece in person in Paris and proposes the following fall, if his health allows it.118 Responding from Tehran, Kevorkian agrees that Freer should see the mihrab since “no mechanical reproduction is capable of conveying the true impression of this production of genius & since I believe that the only means of doing justice to the monument by acquiring proper acquaintance with its merit is to see it.”119 Freer replies that his health has declined, and he will not be able to visit Paris and can no longer ask Kevorkian to reserve the mihrab “under option” for him.120

Back in London in January 1914, Kevorkian shares that he has arranged for the mihrab to be sent to the United States so that Freer can inspect it with the least inconvenience to his health. Kevorkian makes his pitch:

No one in Europe has ever seen it since it was first brought to Europe 15 years ago, and no one knows the real facts in connection with the transaction between me and the former owner [Mostowfi al-Mamalek]. I beg further to state that I have declined many inquiries for inspection from parties who mean business. I invariably declined to allow inspection at the risk of offering my various friends, for I felt that you should not be deprived of the opportunity of the first refusal on account of your health—a reason for which you have no control—and I know that you are the only gentleman to appreciate it fully. It will therefore afford me much pleasure that you should possess it if possible.121

“I know that you are the only gentleman to appreciate it fully.”

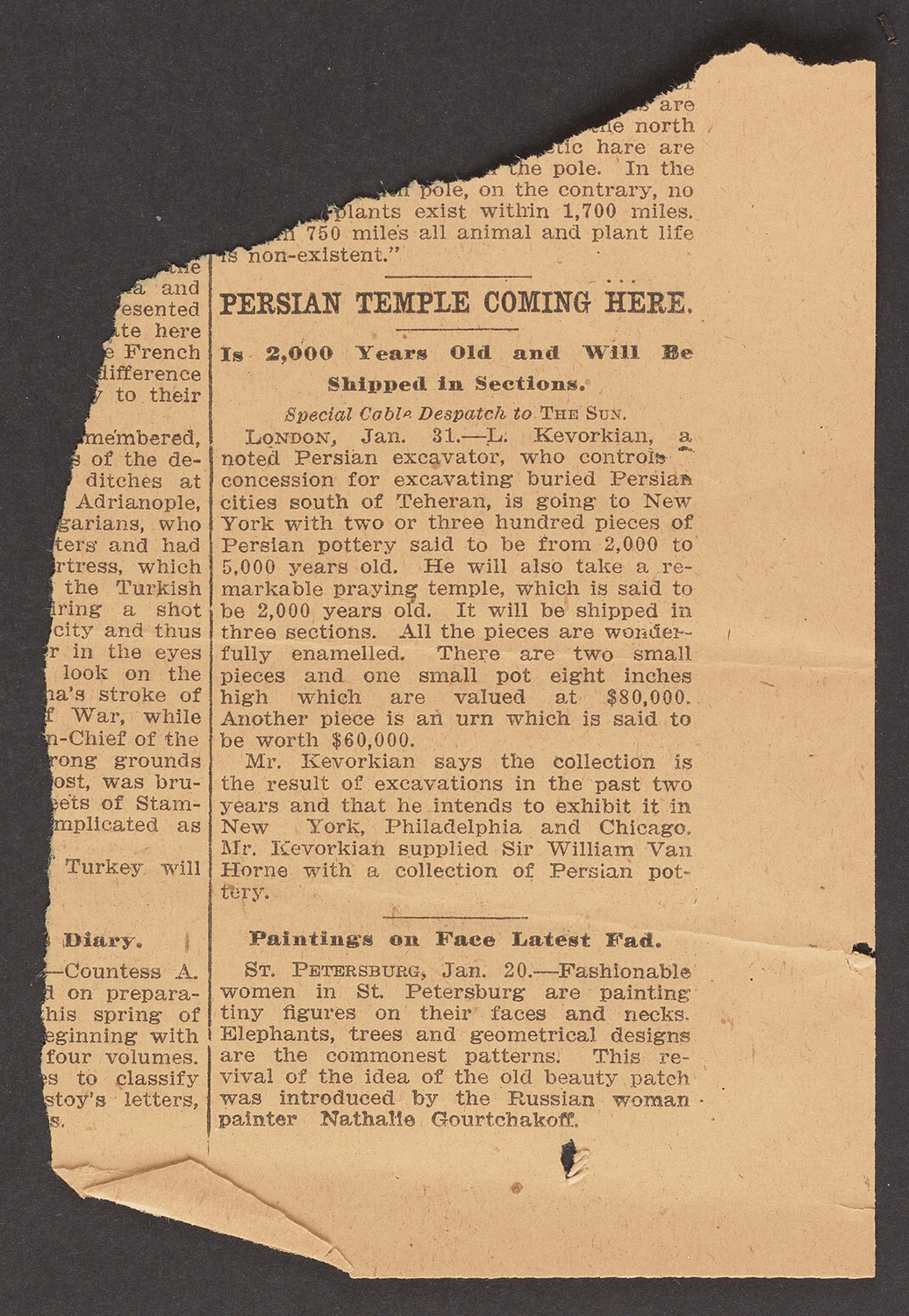

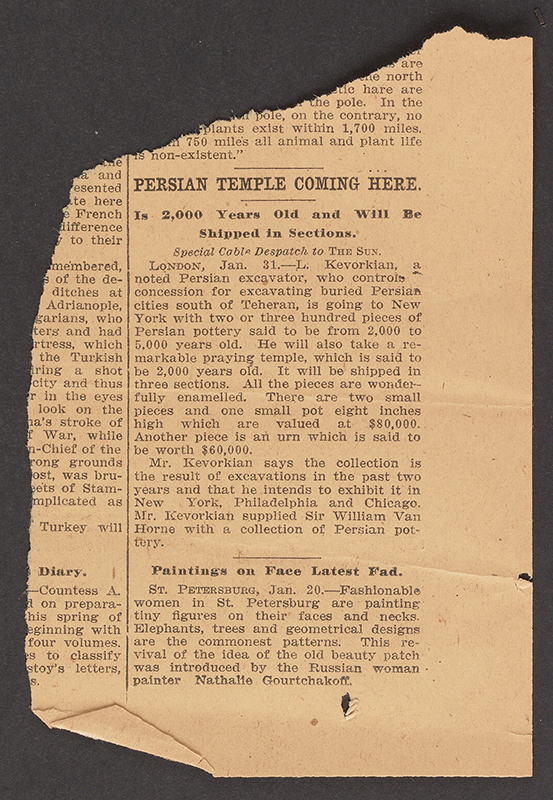

Kevorkian’s trip to New York is announced in a 31 January “Special Cable Despatch [sic]” to The Sun, likely sent in by the dealer himself (fig. 81). This dispatch describes Kevorkian as “a noted Persian excavator [note that he is identified as ‘Persian’ and that ‘archaeologist’ is not used], who controls concessions for excavating buried Persian cities south of Teheran.” The dealer-excavator is on his way to New York with “two or three hundred pieces of Persian pottery said to be from 2,000 to 5,000 years old” and “a remarkable praying temple, which is said to be 2,000 years old.”122 The end of the announcement mentions Kevorkian’s excavations of the last two years and forthcoming exhibitions-sales in New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago. The dispatch is quickly picked up by American outlets, including the New York Herald (1 February 1914) and The Houston Post (14 February 1914).

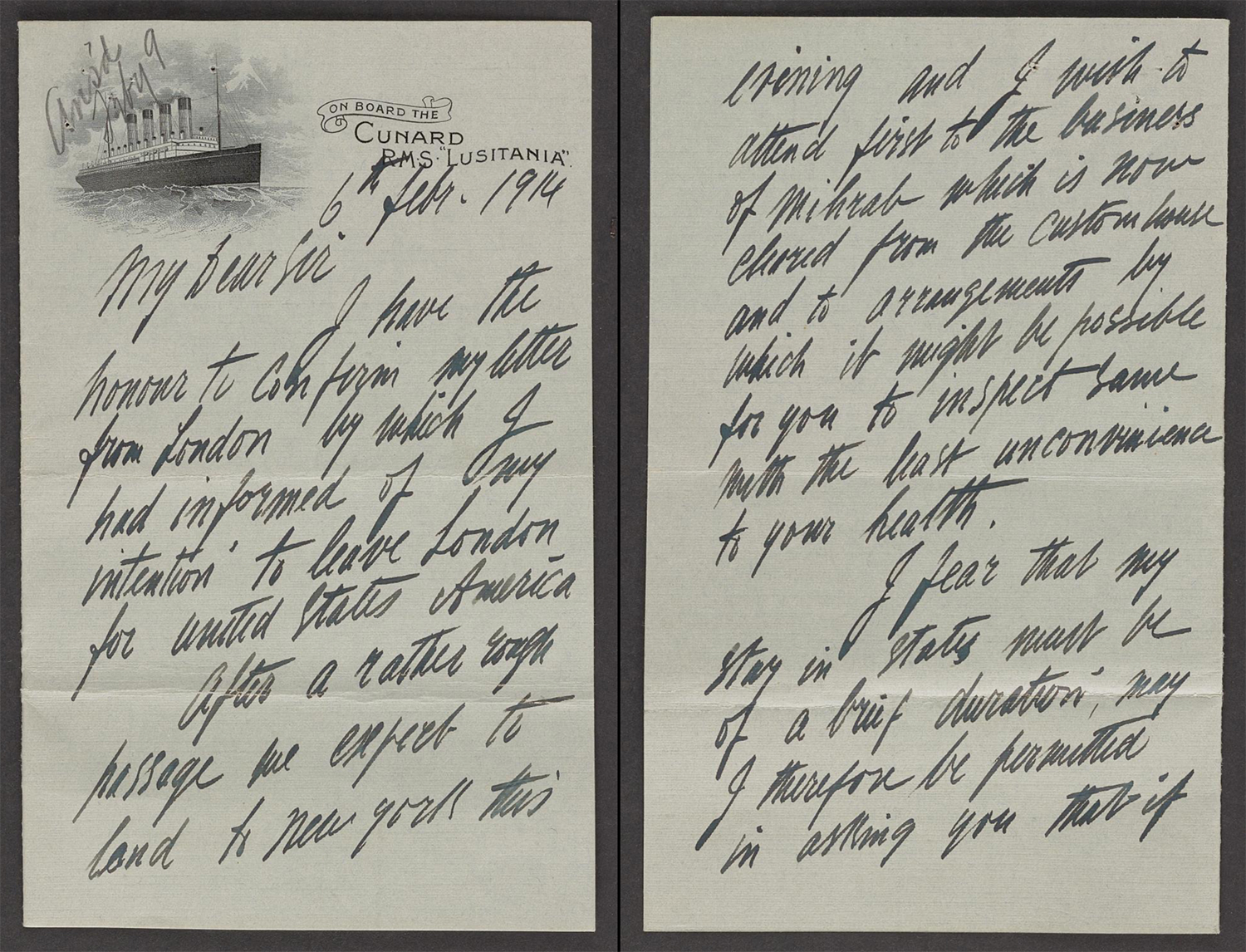

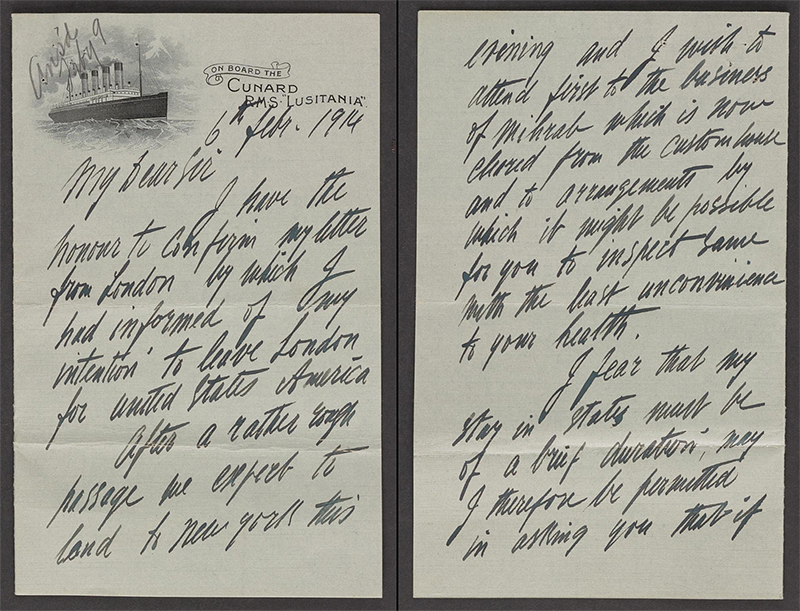

On 6 February 1914, writing from aboard the RMS Lusitania, Kevorkian confirms that he is on his way to New York and that the mihrab has cleared customs and can be available for Freer’s inspection (fig. 82). He is also willing to transport the mihrab to Detroit if needed. Freer offers to come to New York in early March to see the ensemble, and on 12 February, writing from the Plaza Hotel, Kevorkian notes being pleased that Freer has no objection to it being exhibited—likely a reference to the dealer’s pending show in New York—and will “get it mounted and hope it will be ready.”123

It is not clear if Freer saw the mihrab in New York, but it is certain that he did not purchase the piece. Had he done so, the mihrab would likely be preserved in what is today known as the National Museum of Asian Art in Washington, D.C. (map). On 5 May 1906, Freer had signed an agreement with the Smithsonian Institution—“the world’s largest museum, education, and research complex, with 21 museums, 14 education and research centers, and the National Zoo” (About page)—to donate his collection and provide funds for the building of a new museum to house it (the Freer Gallery of Art).124

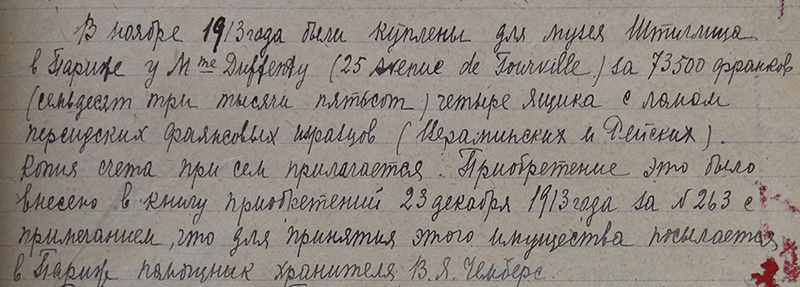

November–December 1913: Paris and St. Petersburg

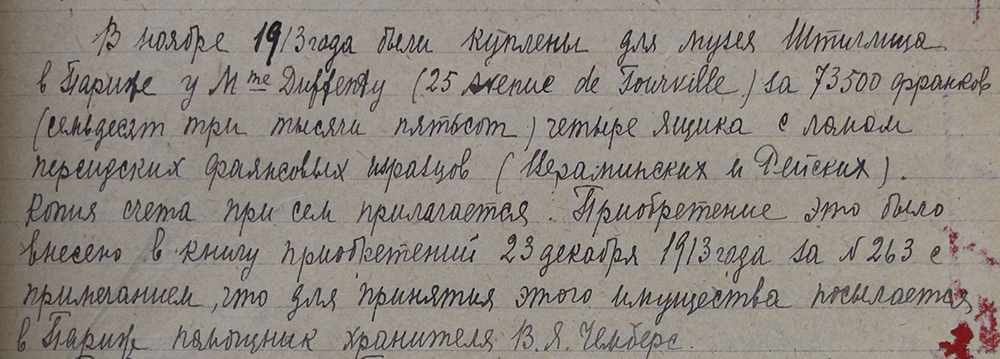

While Kevorkian peddles the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab to Charles Lang Freer and arranges its shipment from Paris to New York, Parisian dealer Clotilde Duffeuty, who had sold a single tile from the mihrab’s outer border to the Stieglitz Central School of Technical Drawing in May 1901, sells the same museum an enormous group of over 950 luster tiles. Many of the tiles can be attributed to the Emamzadeh Yahya, and among the most significant is the tombstone panel attributed to Yahya b. ʿAli’s cenotaph, a large rectangular box that was broken apart like many others (see 1875–76) (fig. 83).

The sale also includes hundreds of star and cross tiles from the tomb. A few contain Persian verses, and many are broken and fragmented, suggesting profound damages during their removal from the walls and/or subsequent transport (fig. 84). The tiles are described as “Varamin-type” and “Rey-type,” but some belong to the Shrine of Pir Hosayn in Prisaatçay village in modern-day Azerbaijan, including its deconstructed cenotaph.125 The total cost is 73,500 French francs (€2912 or $14,160), the assistant curator goes to Paris to accept the “property,” and the acquisition is recorded in the museum’s inventory book on 23 December 1913 (Checklist, no. 19). Due to the outbreak of World War I on 28 July 1914, the tiles remain stored in crates for a decade (jump ahead to 1925). In 1923, the tombstone panel is displayed at the Stieglitz Museum in an exhibition devoted to tiles.

At present, we do not know when, how, and from whom Duffeuty acquired this substantial collection. It is possible that the cenotaph arrived in Paris around the same time as the mihrab (1900), and the fact that both ensembles were released for sale around the same time (1912–13) suggests a connection. Unlike the mihrab, which stayed relatively intact as an ensemble, the tiles that clad the cenotaph were dispersed, and we currently do not have a photograph of it intact to guide its conceptual reassembly. The cenotaph’s physical fragmentation is one of the reasons why it has been largely ignored in the shrine’s historiography, especially in relation to the mihrab.126

March–April 1914: New York

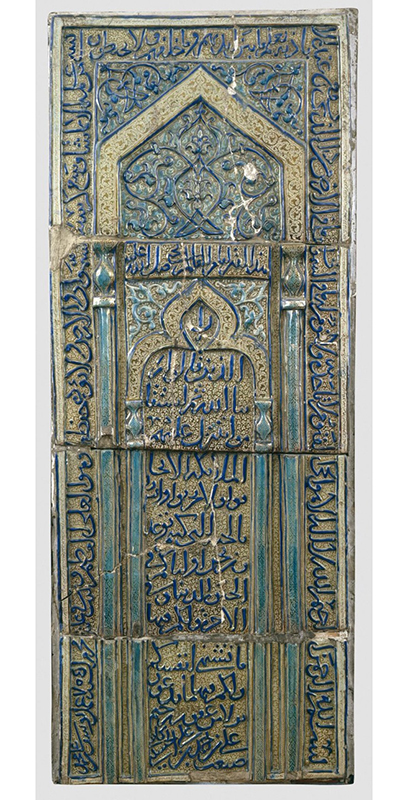

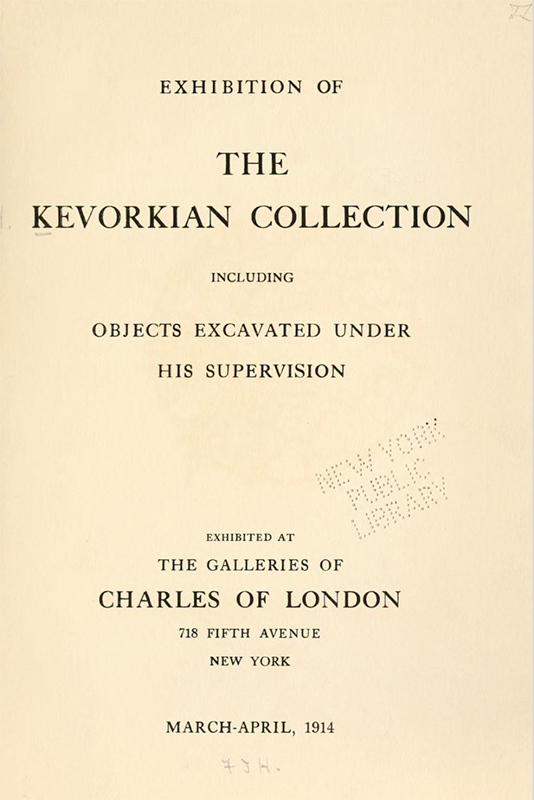

Kevorkian displays the Emamzadeh Yahya’s luster mihrab in an exhibition of his collection at the Galleries of Charles of London in New York (map) (fig. 85). The eight-page catalog entry describes the ensemble as “from the Seljoucid Temple at Veramin” and states, “The temple from which this Mihrab was taken is of an earlier date than the Mihrab itself, and it is therefore tolerably certain that this masterpiece was made under the orders of Hulagu as a part of his policy of restoration.”127 The allusion to the Mongol khan Hulegu (r. 1256–65) has no basis in fact and invoking him as the conqueror of the Abbasid caliphate (750–1258) likely functions to attract attention and exoticize the story. Despite this, the entry ends with a useful list of the mihrab’s Qur’anic inscriptions, which Kevorkian had also sent to Freer (see 1913). The mihrab is not illustrated, and the Emamzadeh Yahya is not named.

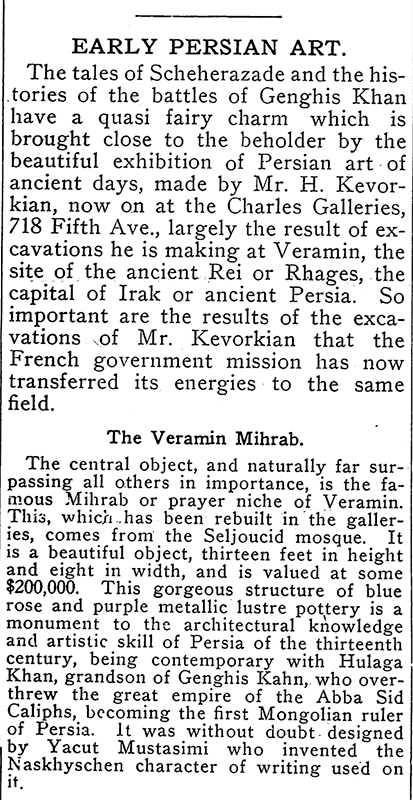

A contemporary newspaper article describes the exhibition as the result of Kevorkian’s excavations “at Veramin, the site of the ancient Rei or Rhages,” further confusing the two distinct cities located twenty-five miles apart (fig. 86). The “Veramin Mihrab” is lauded as the “central object” coming from “the Seljoucid mosque” and “valued at some $200,000.”

May 1914: Philadelphia

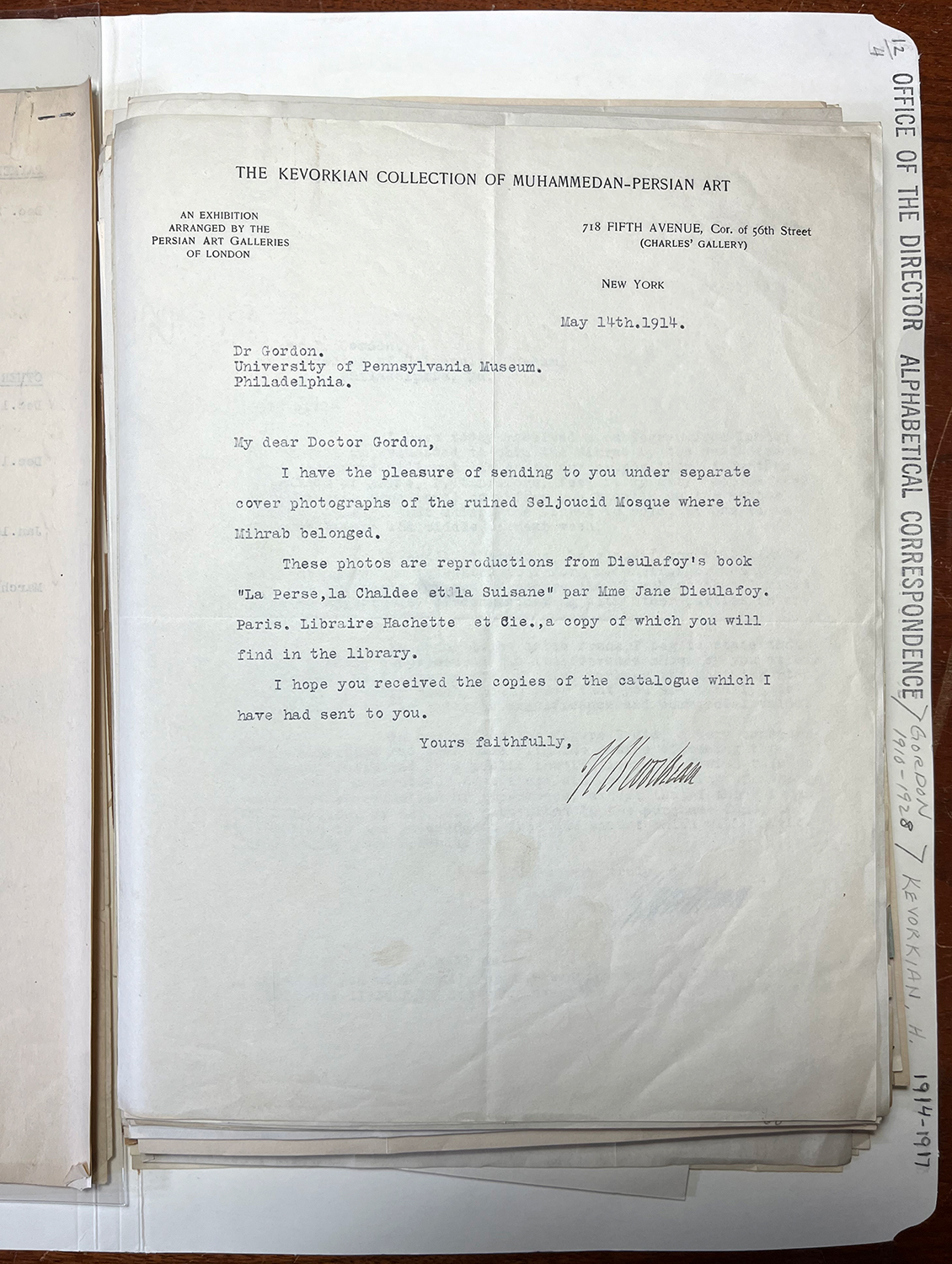

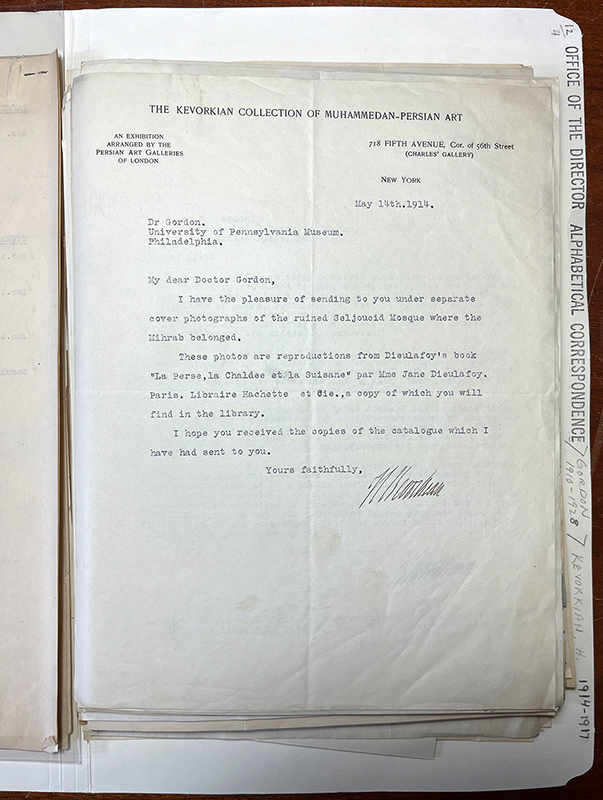

After eight months of ultimately failed negotiations with Charles Lang Freer, Kevorkian moves on to his next potential buyer. On 5 May, he sends a telegram to Dr. George Byron Gordon (d. 1927), director of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (henceforth Penn Museum), offering the mihrab for sale (fig. 87).128 In a subsequent letter on 14 May, Kevorkian mentions sending “photographs of the ruined Seljoucid Mosque where the Mihrab belonged” and cites the reproductions as coming from Dieulafoy’s La Perse (fig. 88). While he uses Dieulafoy’s famous account to add value to the mihrab, he continues to fail to name the Emamzadeh Yahya.

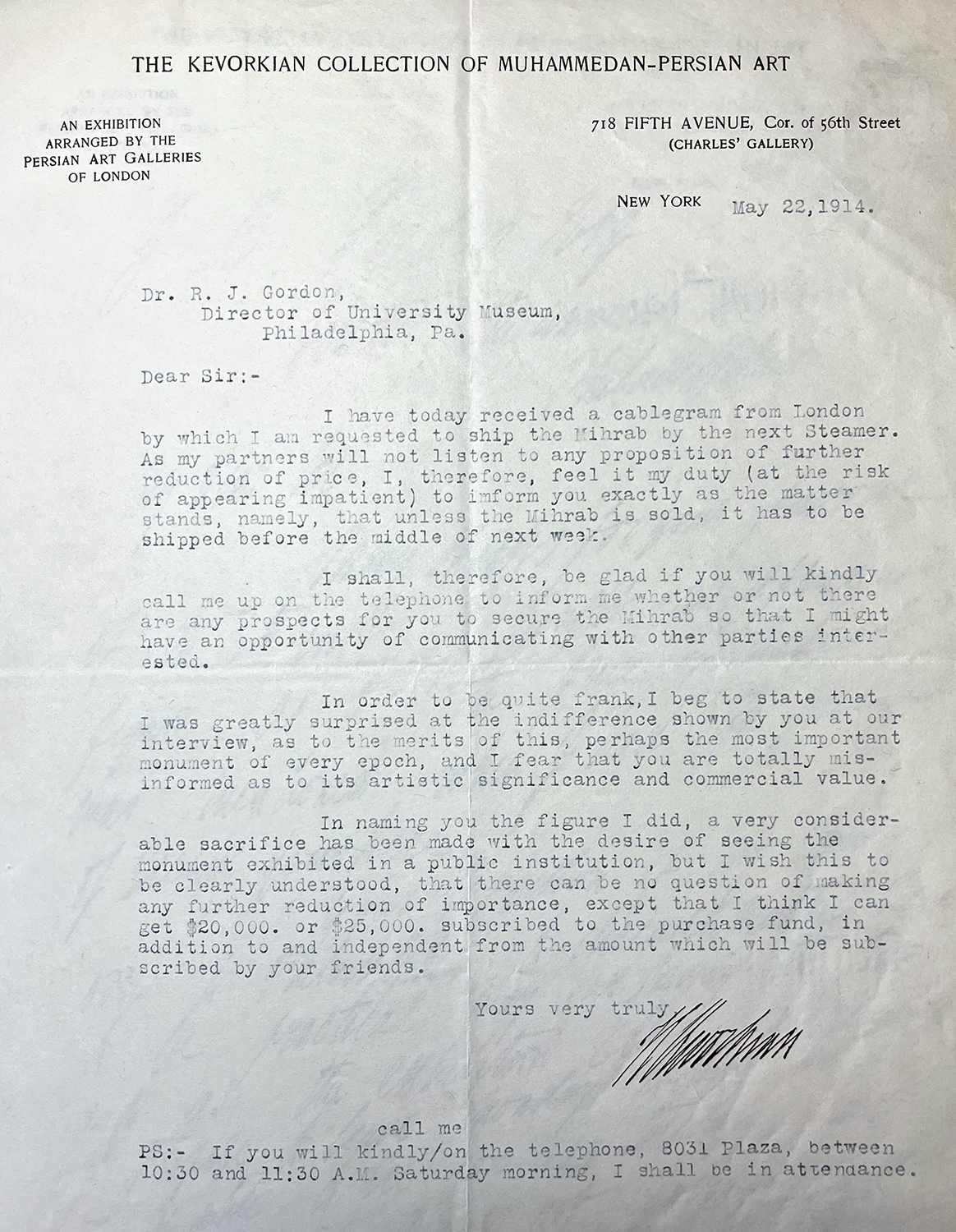

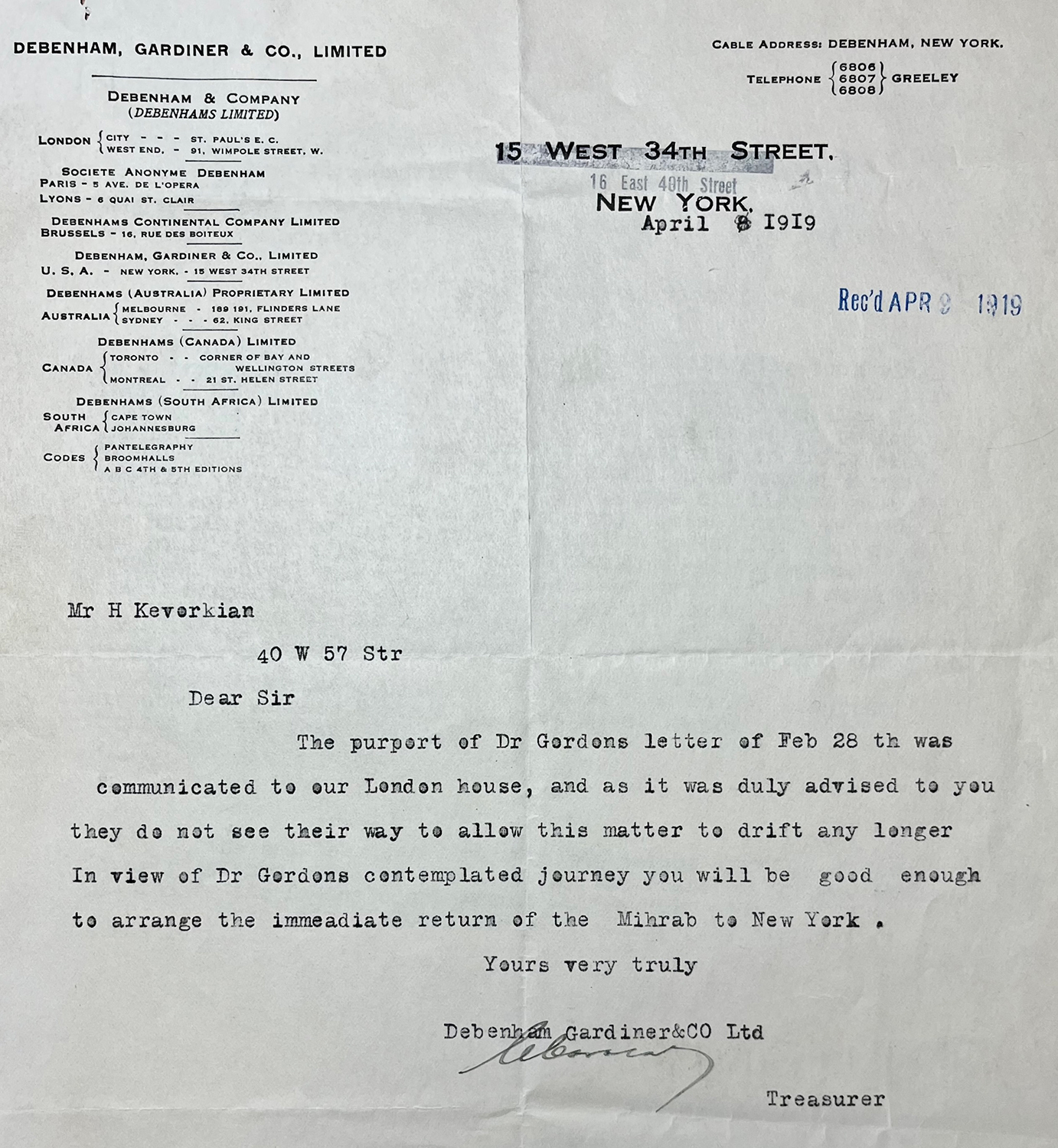

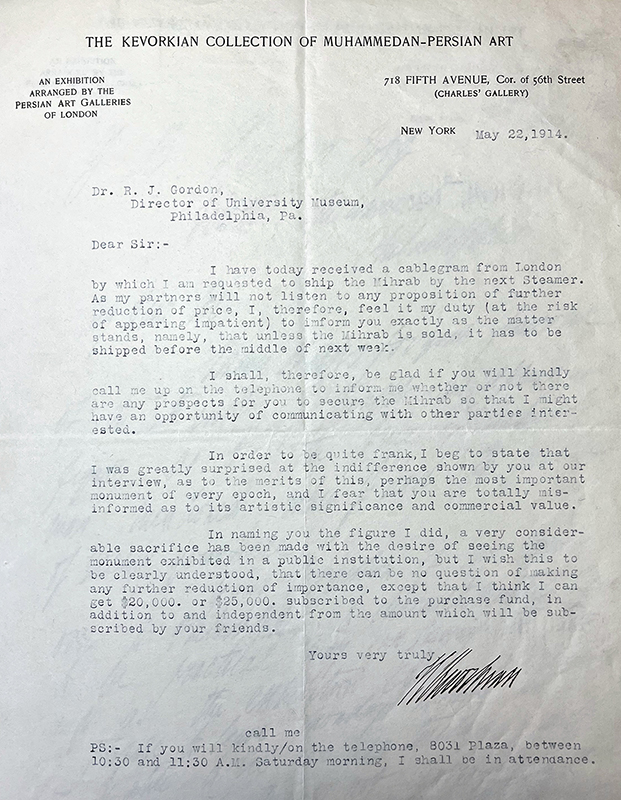

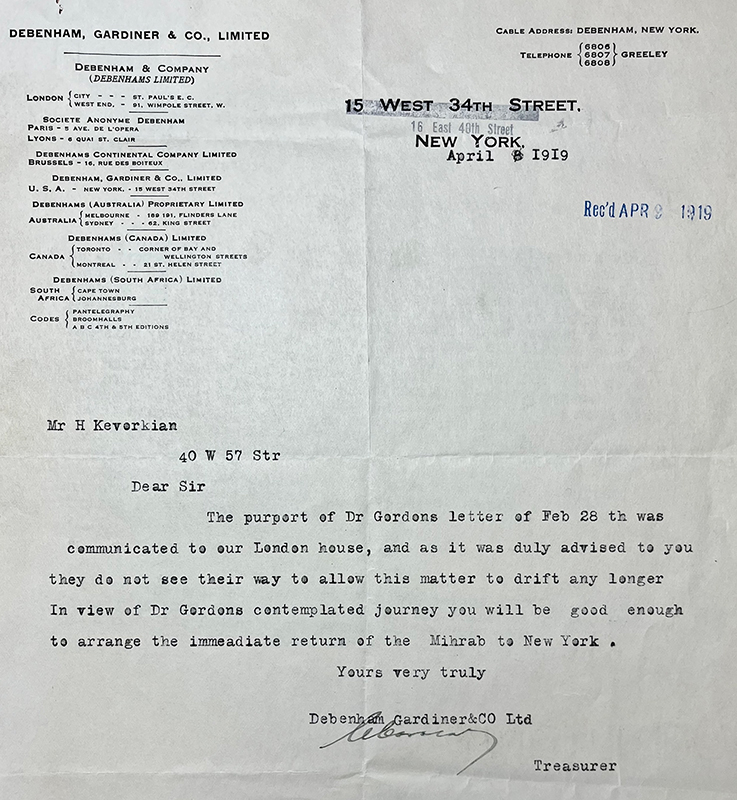

On 22 May, following the receipt of a cablegram from his “partners” in London, Kevorkian’s tone becomes urgent. He informs Gordon that if the museum does not agree to purchase the mihrab, it will be shipped to London on the next Steamer (fig. 89).129 The dealer’s reference to partners is significant, because it reveals that he (or his Persian Art Galleries) was not acting alone in purveying the mihrab, which involved an international commercial network for matters like storage, travel, and insurance. Subsequent correspondence reveals that his main partner in London was Debenhams Limited, a large retailer founded in 1778 with a flagship department store—Debenham & Freebody (established 1908)—on Wigmore Street in London’s West End (map), about a half a mile north of Kevorkian’s gallery (map).130

Kevorkian highlights the mihrab’s “artistic significance and commercial value,” continuing the decisive shift away from its religious and devotional meanings and functions. This reframing is further evident in Kevorkian’s discussion of where the mihrab should be exhibited. He expresses a desire to see the mihrab displayed in a public institution (recall similar sentiments to Freer)—what he terms an act of “sacrifice”—but also makes it clear that he cannot reduce the price further. He thinks he can get $20,000 or $25,000 “subscribed to the purchase fund,” which suggests that he was courting someone else to aid the museum’s acquisition. The next day (23 May), Gordon declines the offer, citing the price as the main obstacle.

28 July 1914–11 November 1918: World War I

After his first unsuccessful negotiation with the Penn Museum, Kevorkian ships the mihrab back to London, probably just before the outbreak of the First World War on 28 July 1914. Britain enters the war on 4 August, meaning that the mihrab is now in an active war zone (fig. 90).

1915–16: Philadelphia

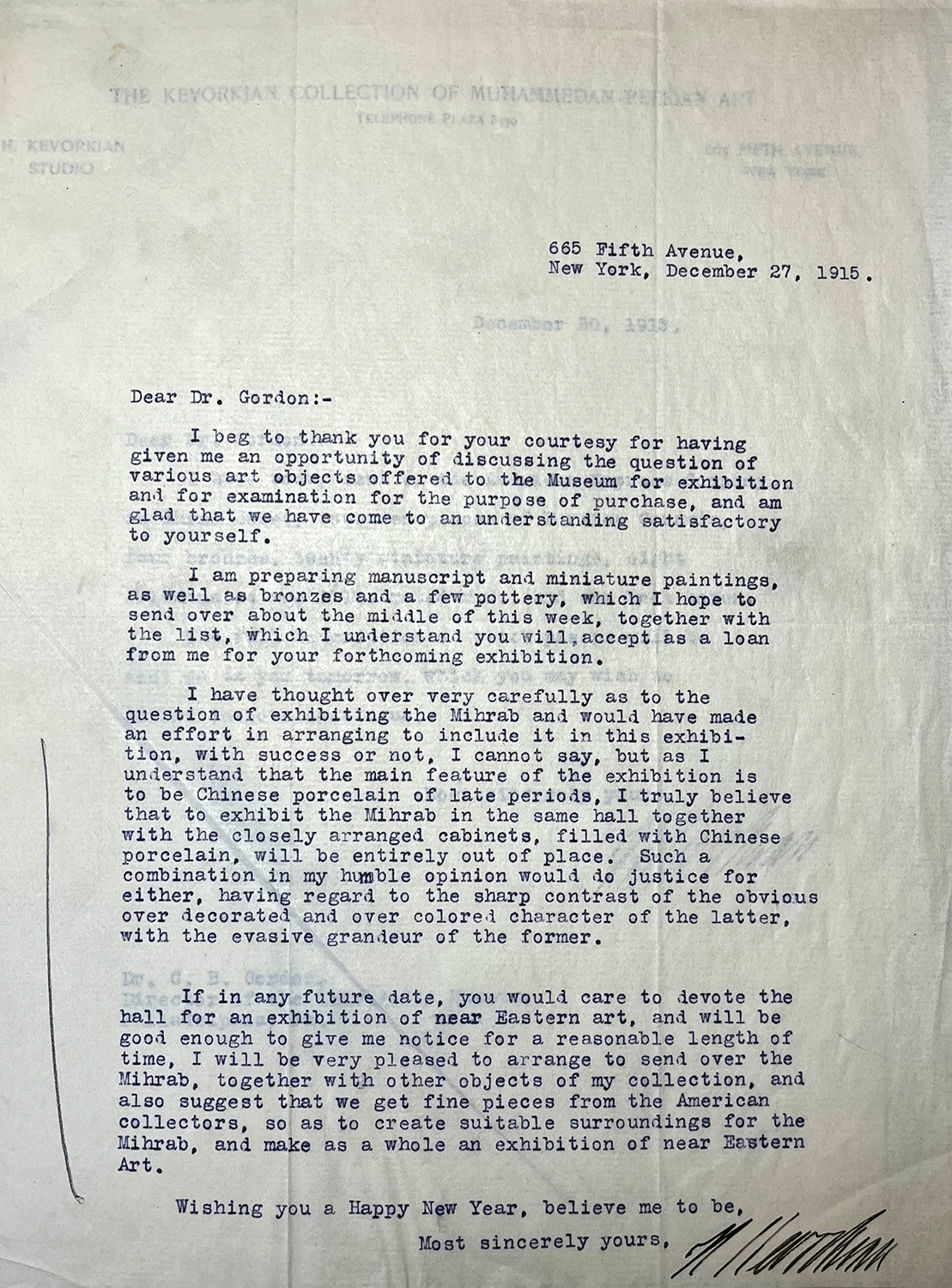

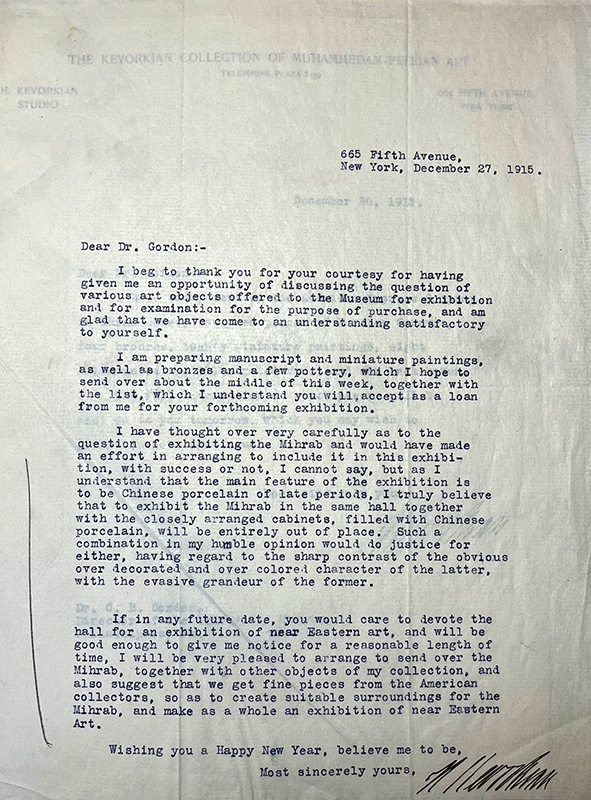

During the war, Kevorkian and Gordon stay in touch about several loans and purchases, and in December 1915, Gordon asks the dealer to send the mihrab to the museum for inclusion in an exhibition of Chinese porcelain. Kevorkian refuses this request, calling the display of the mihrab alongside Chinese porcelain “entirely out of place” (fig. 91). Instead, he proposes a future exhibition on “near Eastern Art” that would include the mihrab and other materials in his collection.

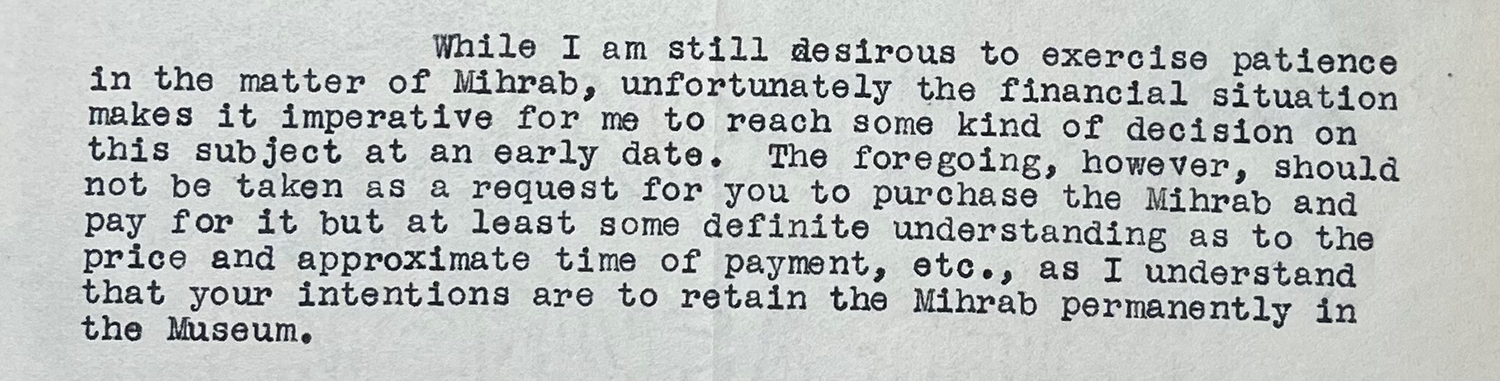

Kevorkian continues to see the Penn Museum as a potential home for the mihrab, and in July 1916, he writes to Gordon pressing for an update on the museum’s decision. He notes receiving “serious offers of purchase” and invitations to exhibit the piece at other museums but claims to have declined them in favor of maintaining his “pourparler” (a French term meaning preliminary negotiations or informal discussions) with the Penn Museum. He describes their relationship as not binding but meriting priority.131

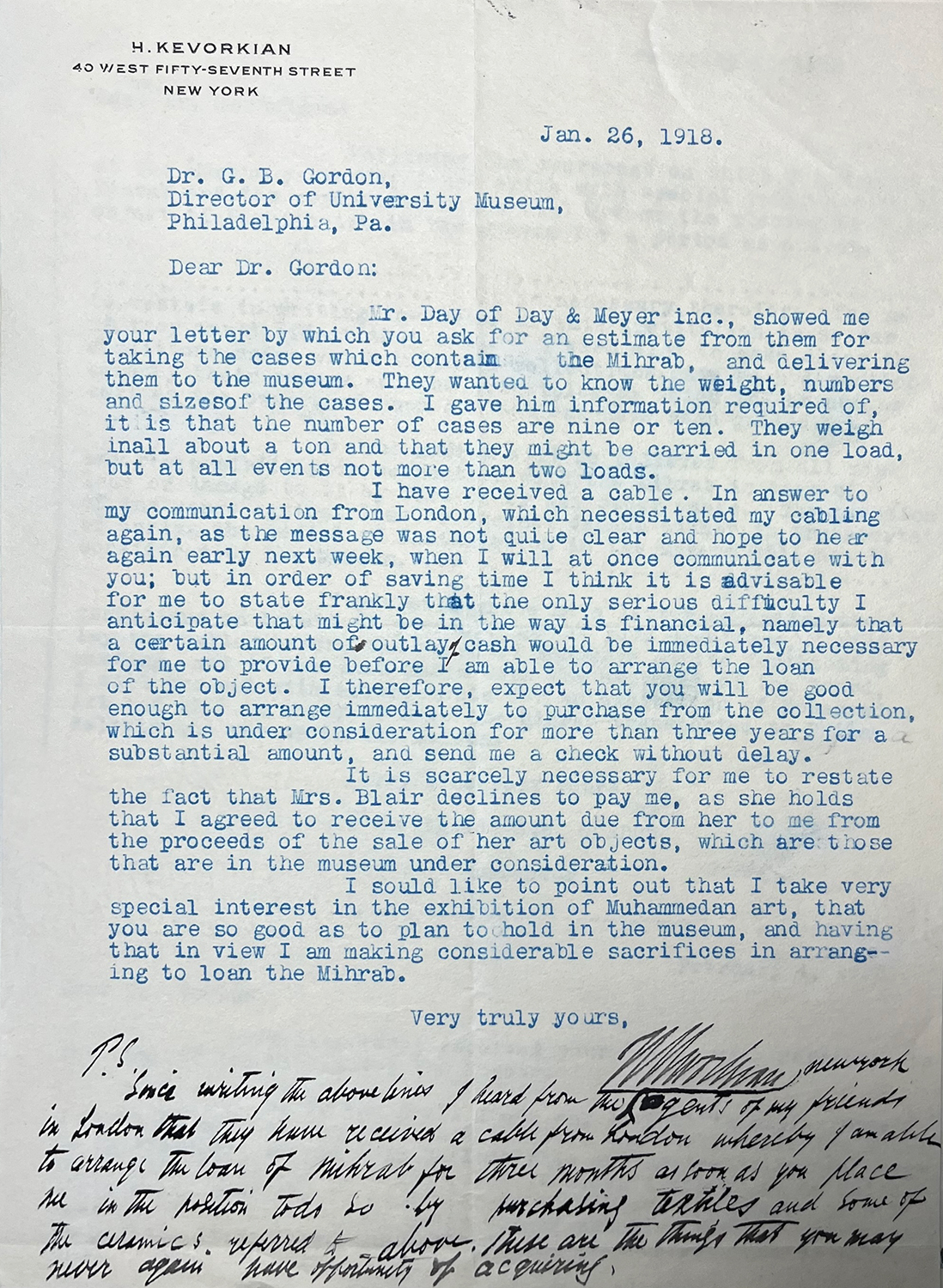

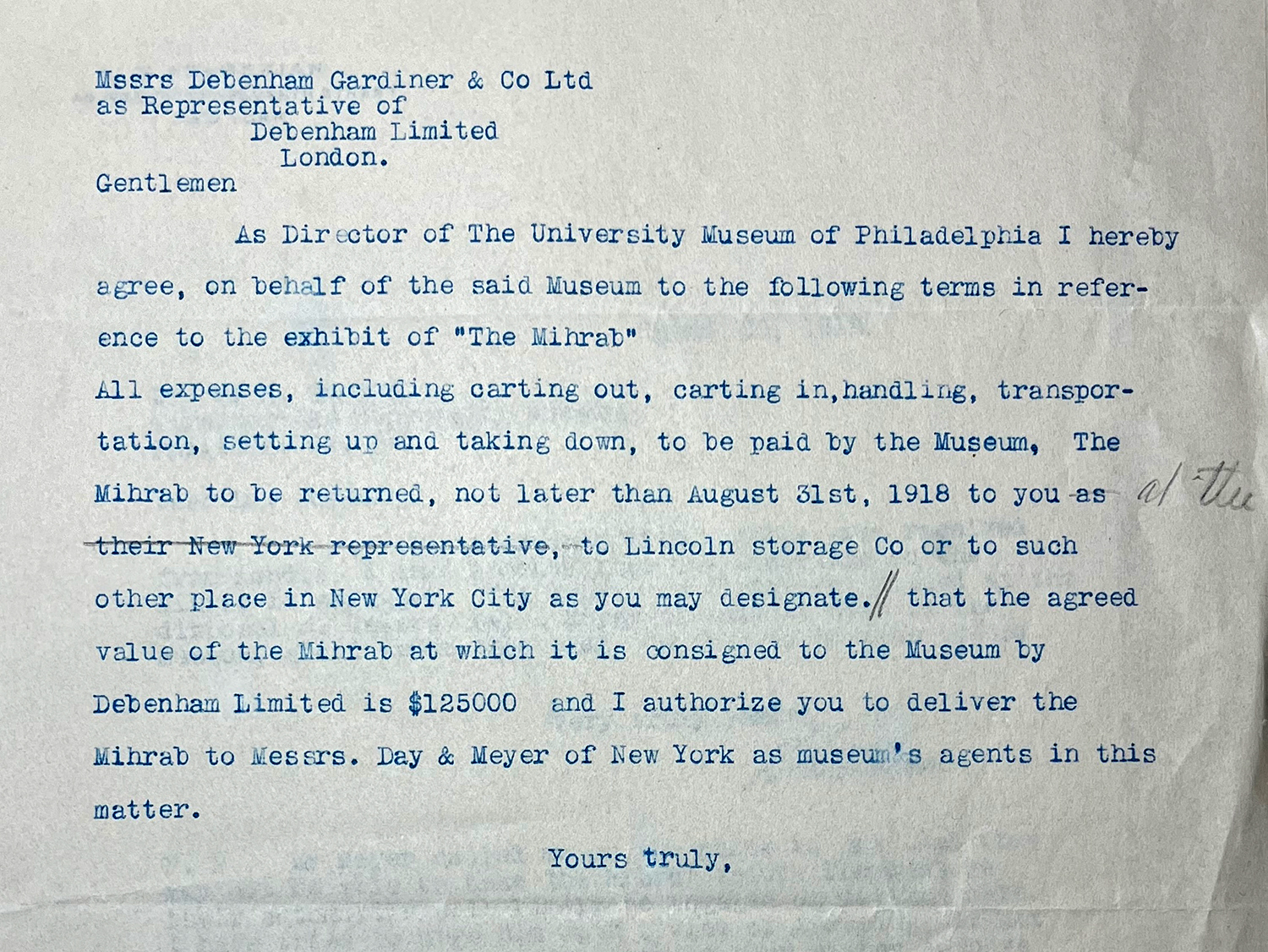

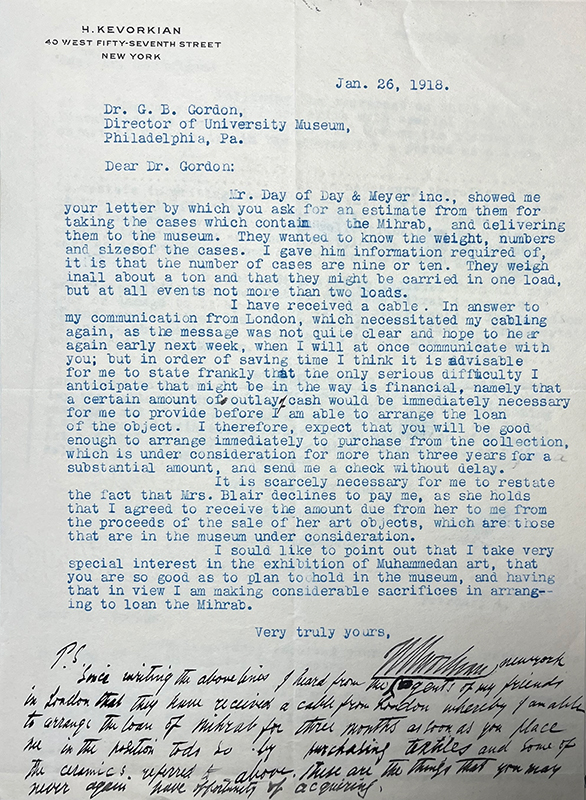

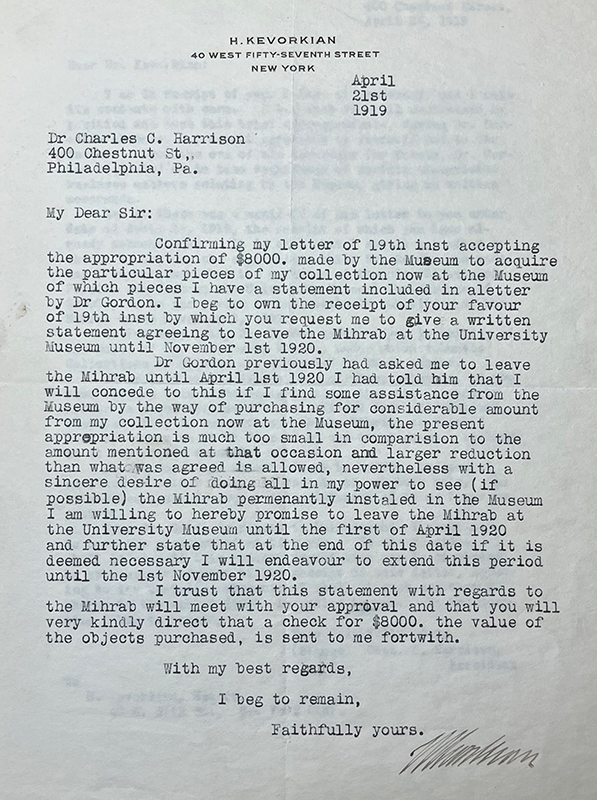

January–April 1918: New York and Philadelphia

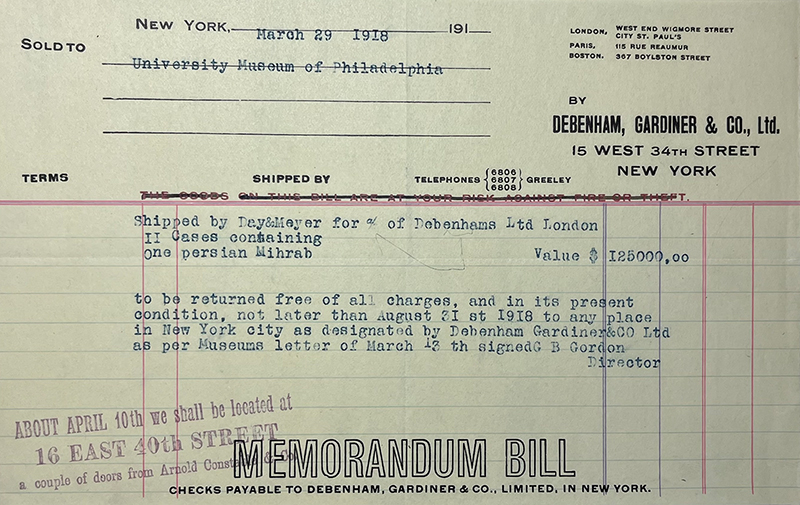

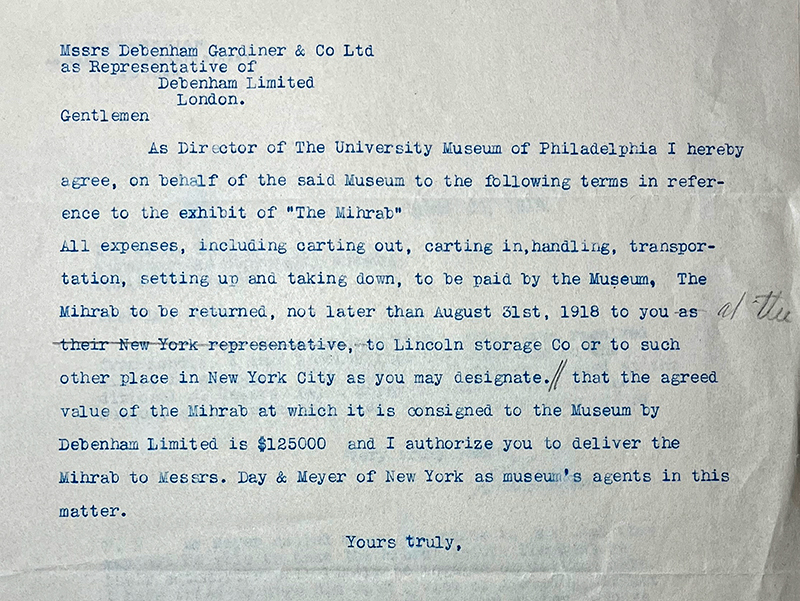

The Penn Museum’s exhibition of “Mohammedan Art” is approved, and Kevorkian and his partners agree to lend the mihrab for three months. The main condition for the mihrab’s loan is that the Penn Museum commits to purchase, for no less than $8,000 ($185,129 in August 2025), textiles and ceramics from Kevorkian’s collection that had been on loan to the museum for over three years. Kevorkian is frank about his need for some “outlay cash,” likely to cover expenses for storing and transporting the mihrab (fig. 92). The dealer underscores his interest in the exhibition and, again, his “considerable sacrifices in arranging to loan the Mihrab.”

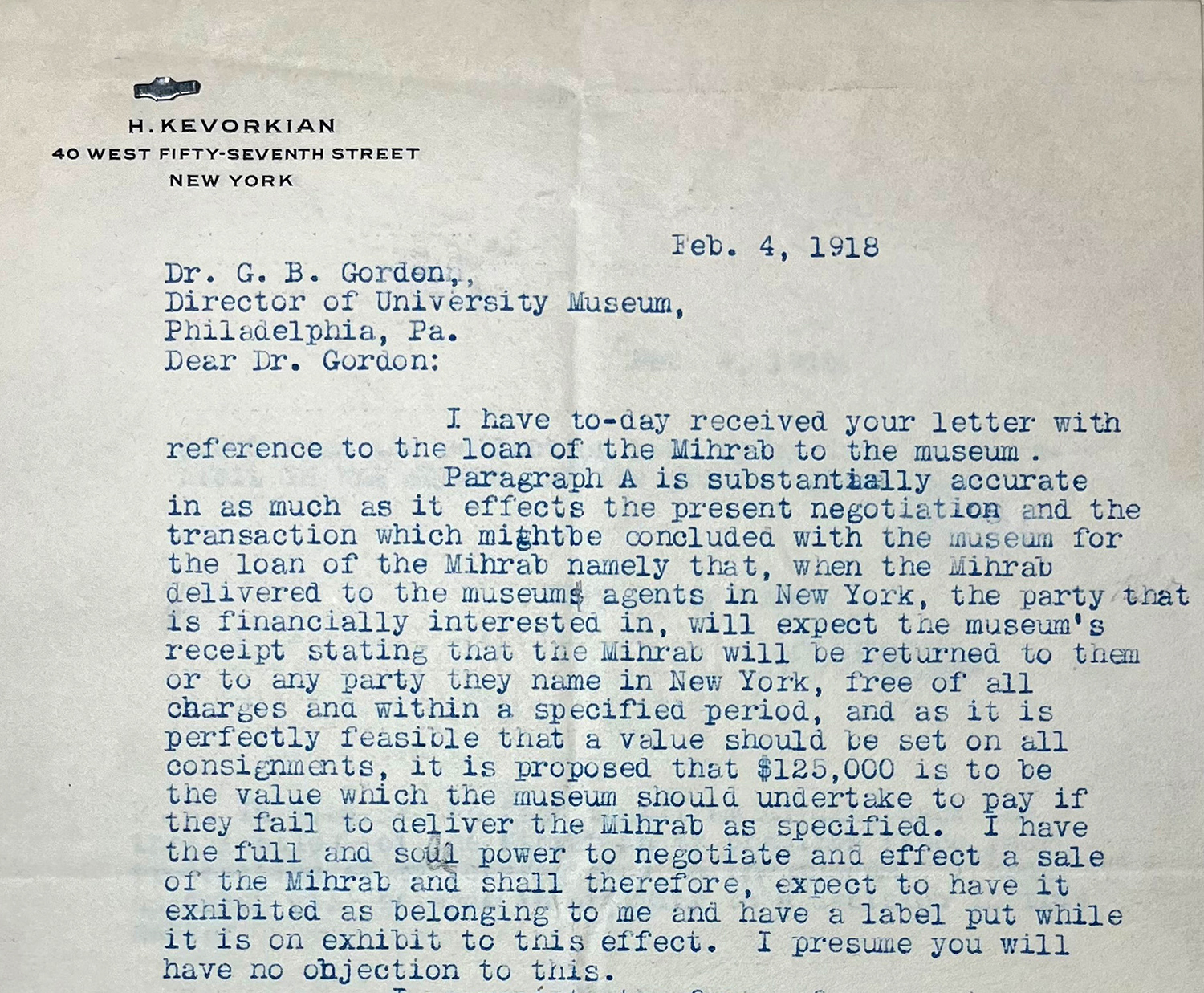

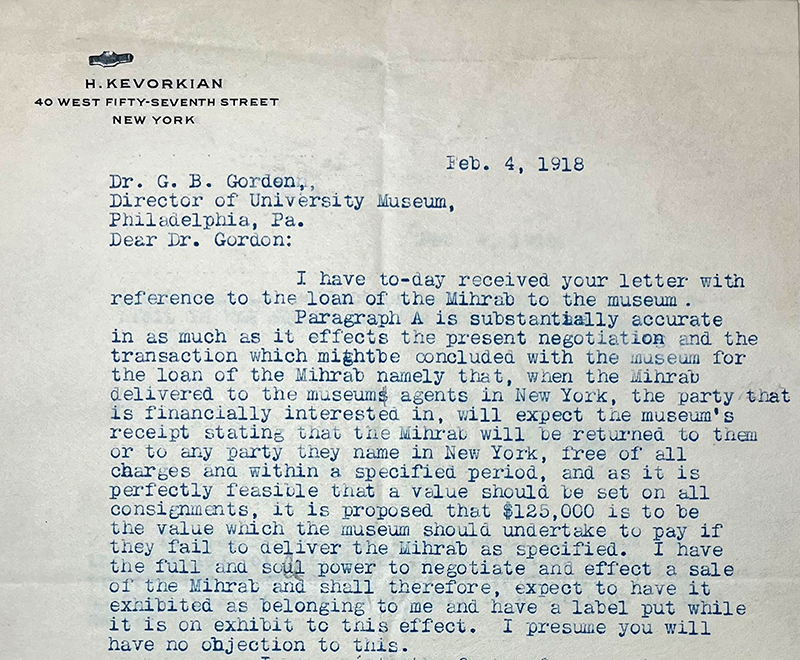

Over the course of February, Kevorkian and Gordon continue to iron out the terms of the loan. The dealer underscores that he is “holding back the installation of the Mihrab in my premises [in New York] since your proposition of my loan of the same to the museum.”132 He proposes $125,000 ($2,872,127 in August 2025) as the mihrab’s value for insurance purposes and underscores that he has “the full and soul [sic] power to negotiate and effect a sale of the Mihrab and shall therefore, expect to have it exhibited as belonging to me and have a label put while it is on exhibition to this effect” (fig. 93). This exchange suggests that Kevorkian’s primary motivation for displaying the mihrab publicly was to secure its sale. This contradicts his own statement that he was eager to see the “Mihrab exhibited as a loan in the museum not for any commercial consideration but for aesthetic pleasure.”133

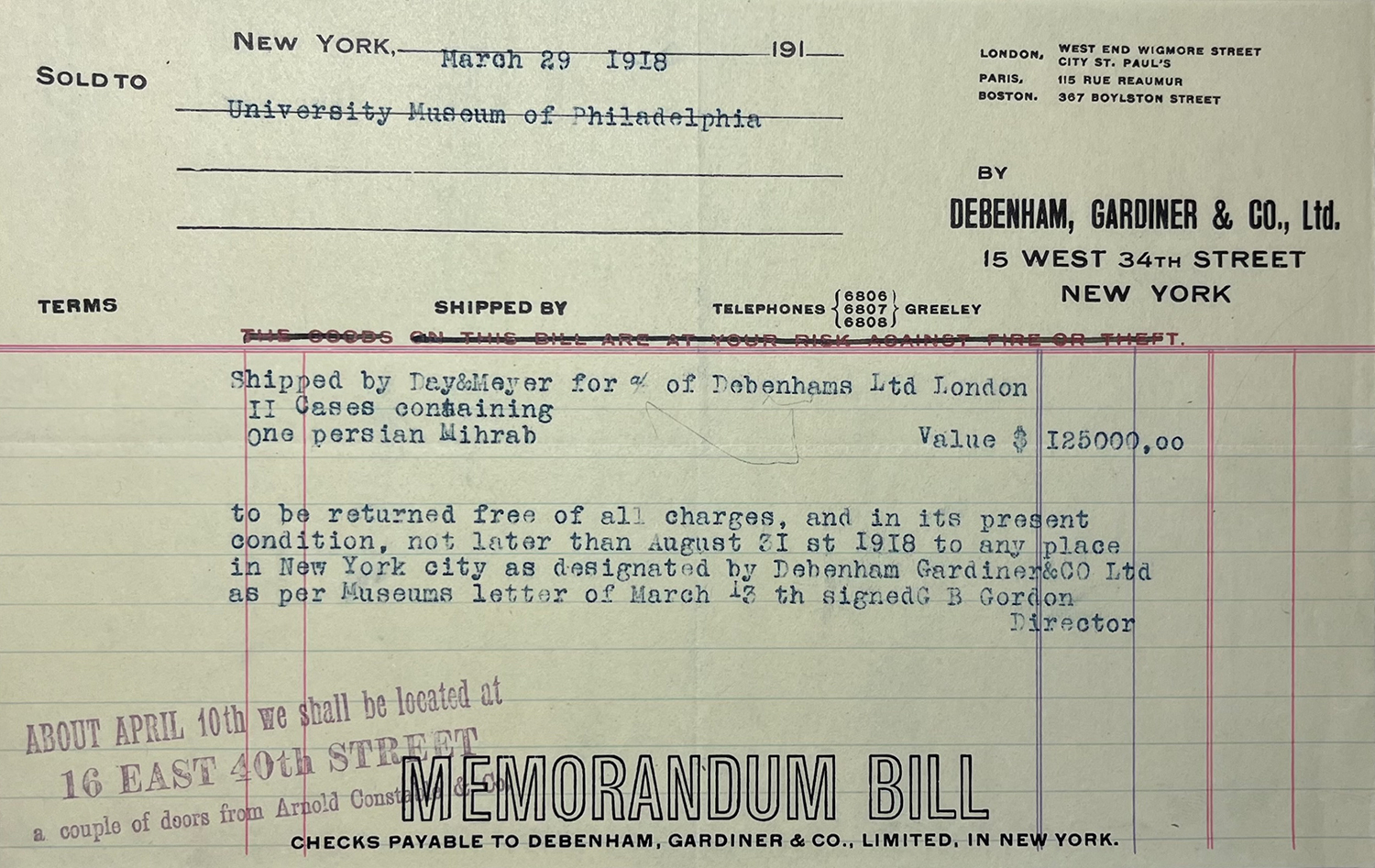

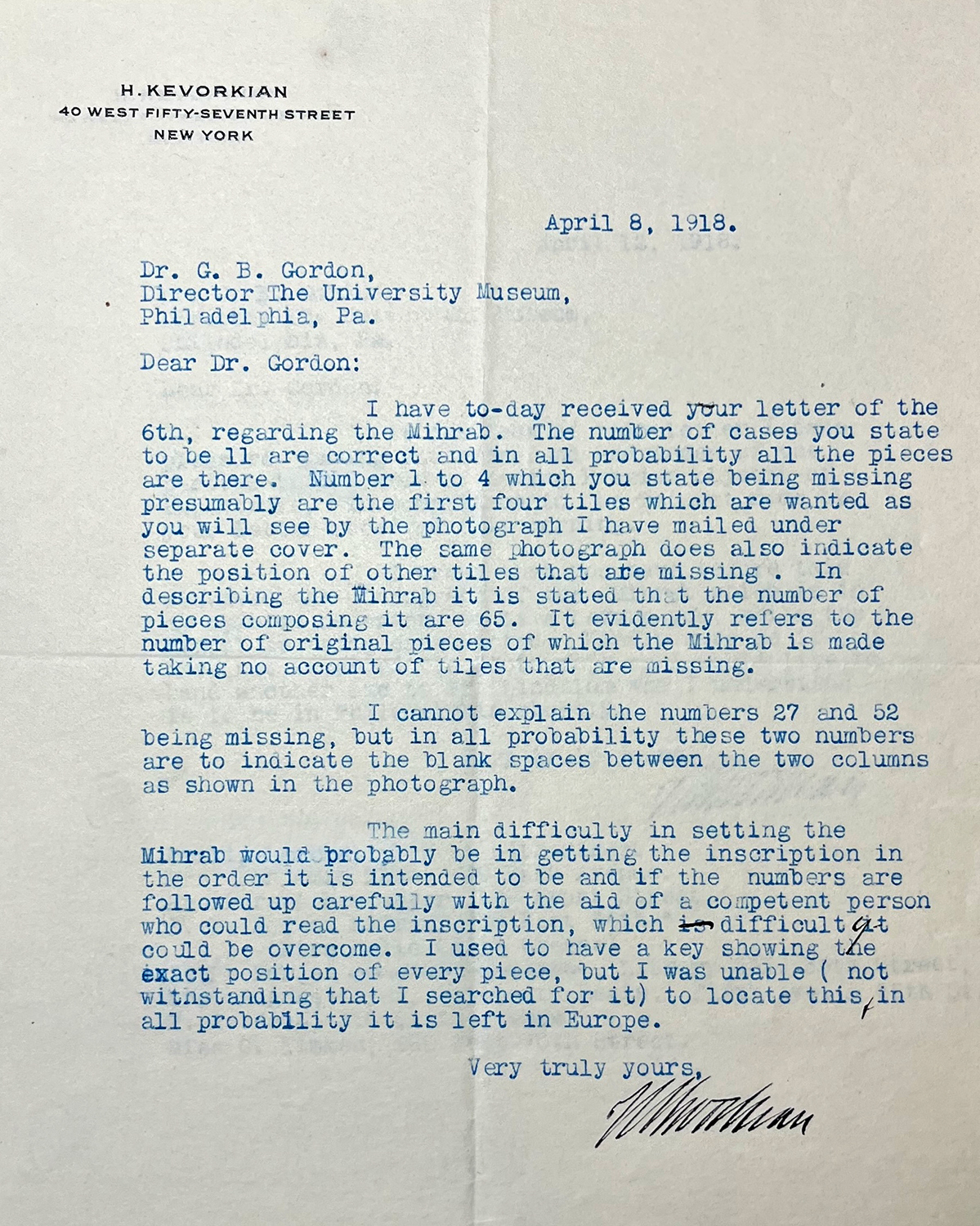

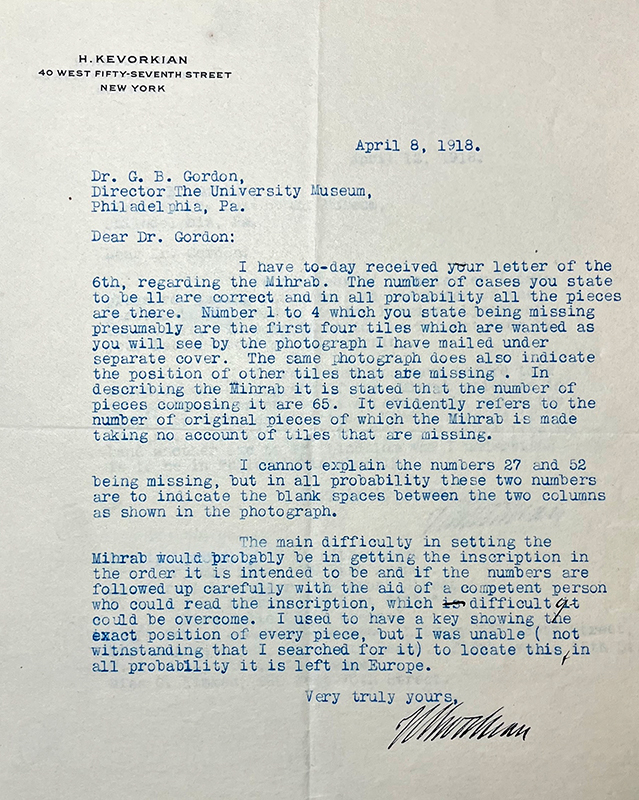

The correspondence between Kevorkian and Gordon reveals the many complex logistics involved in moving the mihrab, including its transportation from New York to Philadelphia (by Day & Meyer Corp.), installation at the museum (by Charles Lindblom & Son in New York, responsible for the 1914 installation), and insurance coverage while in transit to and from Philadelphia and against fire and burglary while in the museum (the latter likely provided by Lloyd’s of London) (figs. 94–95).134 The mihrab weighed about a ton, was packed into eleven cases, and required three to four weeks for installation. In one letter, Kevorkian advises transporting the boxes by truck rather than by train, citing delays in train service and the “extreme frailty” of the pieces.135

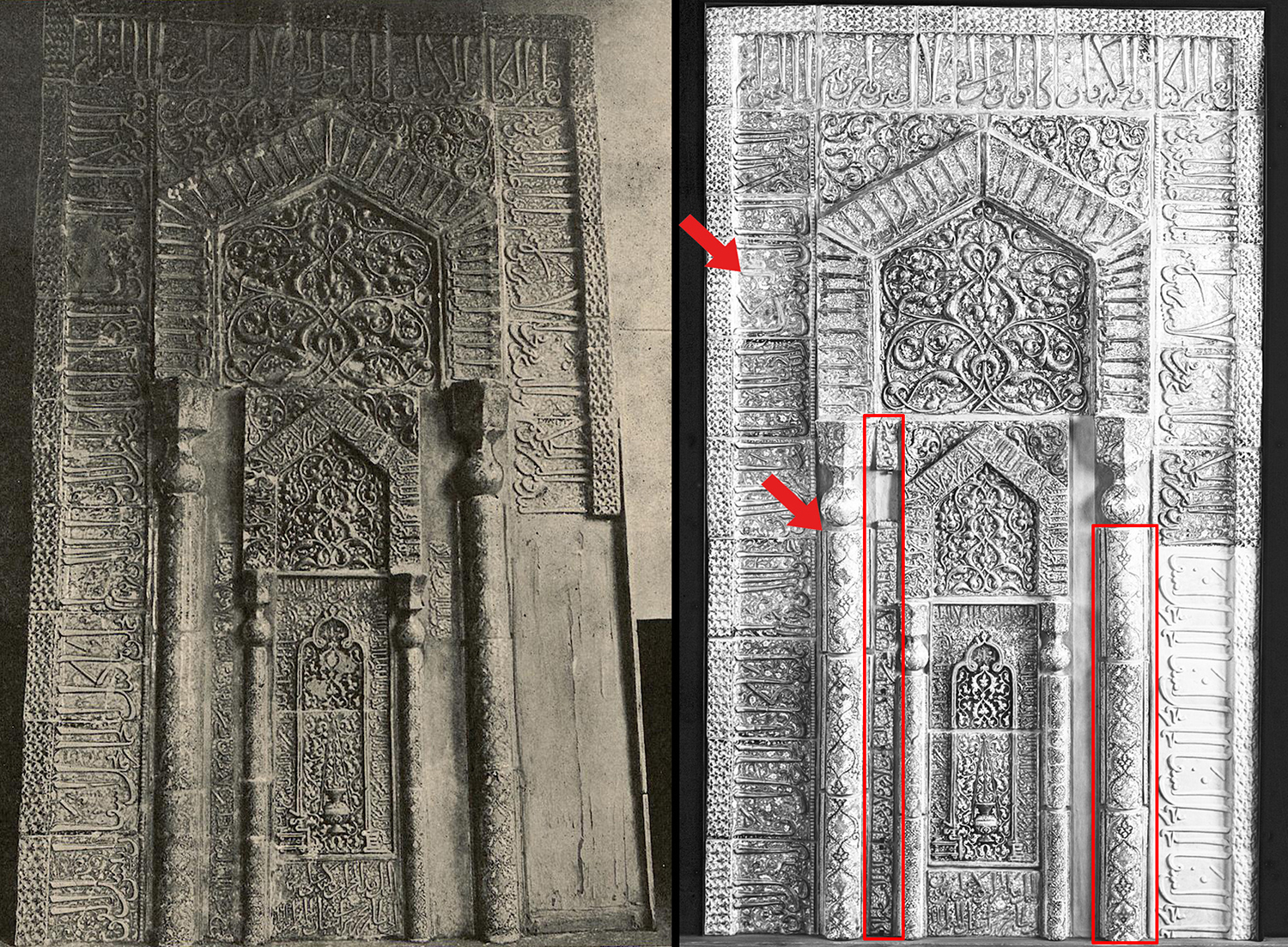

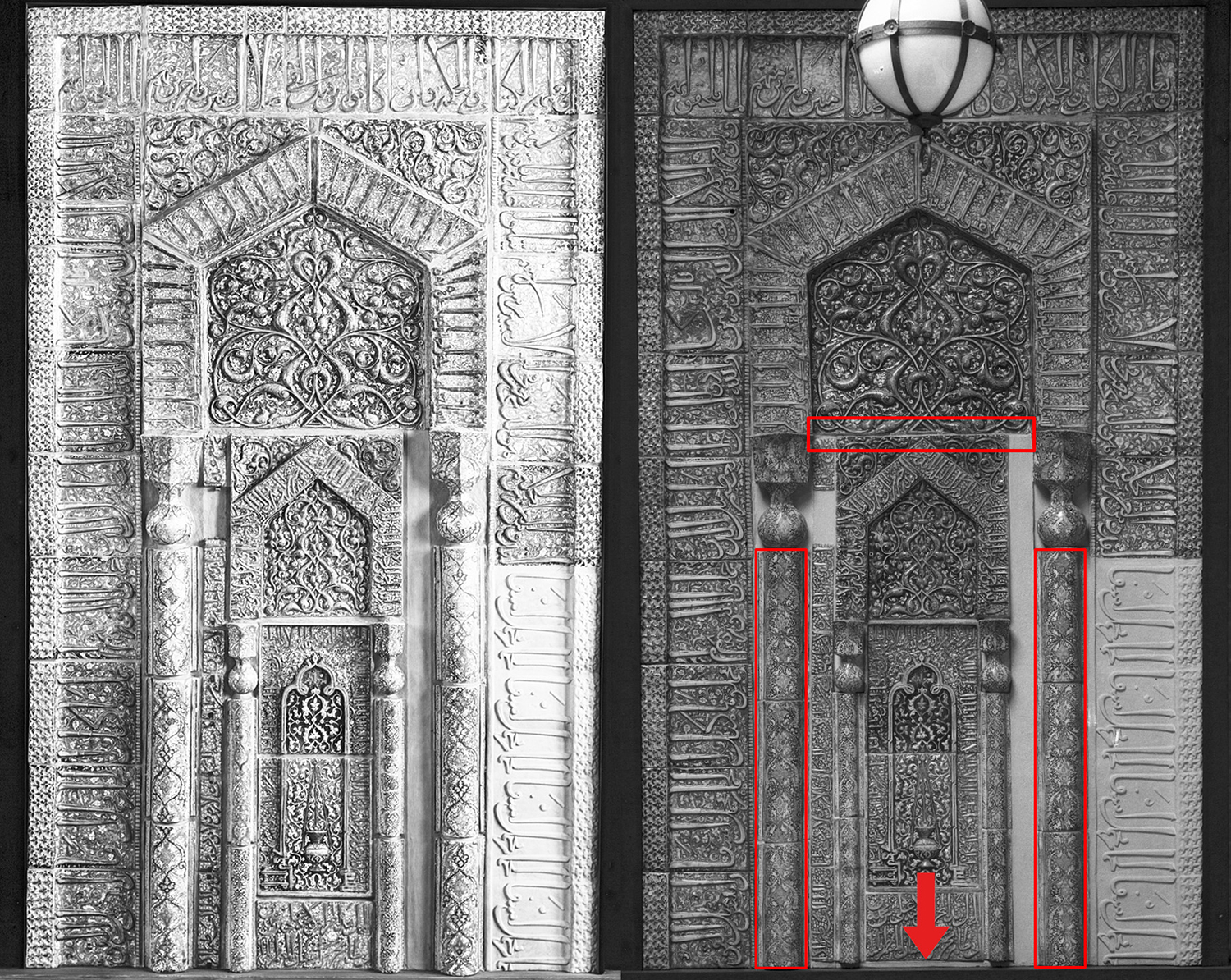

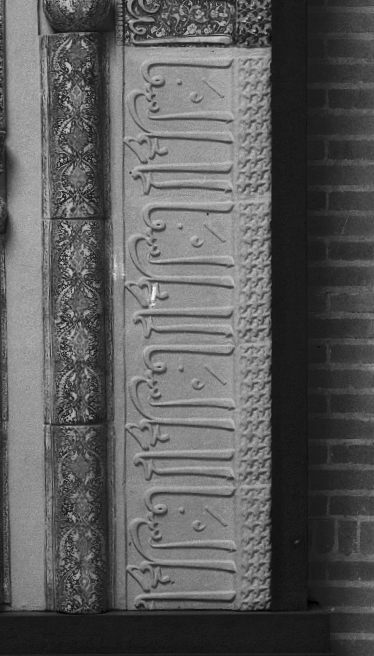

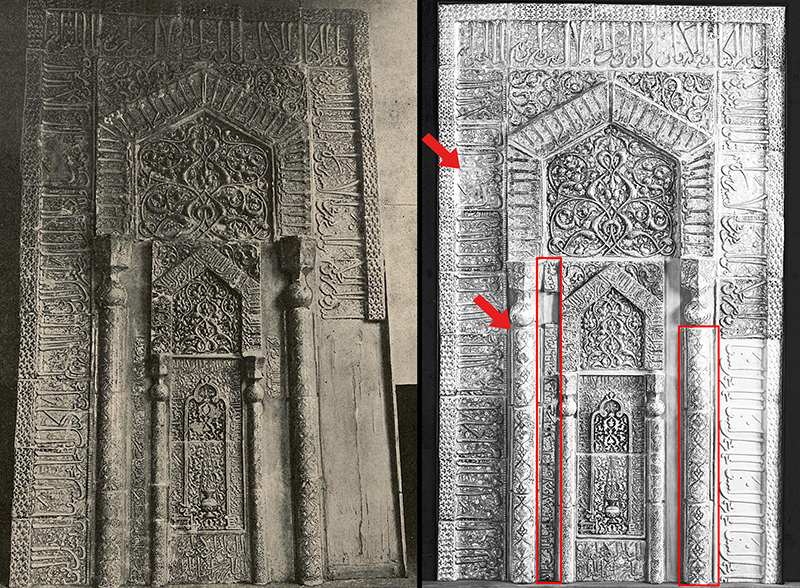

To facilitate the installation, Kevorkian provides Gordon with detailed instructions and an annotated photograph.136 Aware of missing tiles from the outer border and in between the columns, he identifies the main challenge as “getting the inscription in the order it is intended to be” but assures Gordon that this is feasible if guided by someone competent in reading (fig. 96). Kevorkian also recalls once possessing “a key showing the exact position of every piece.”

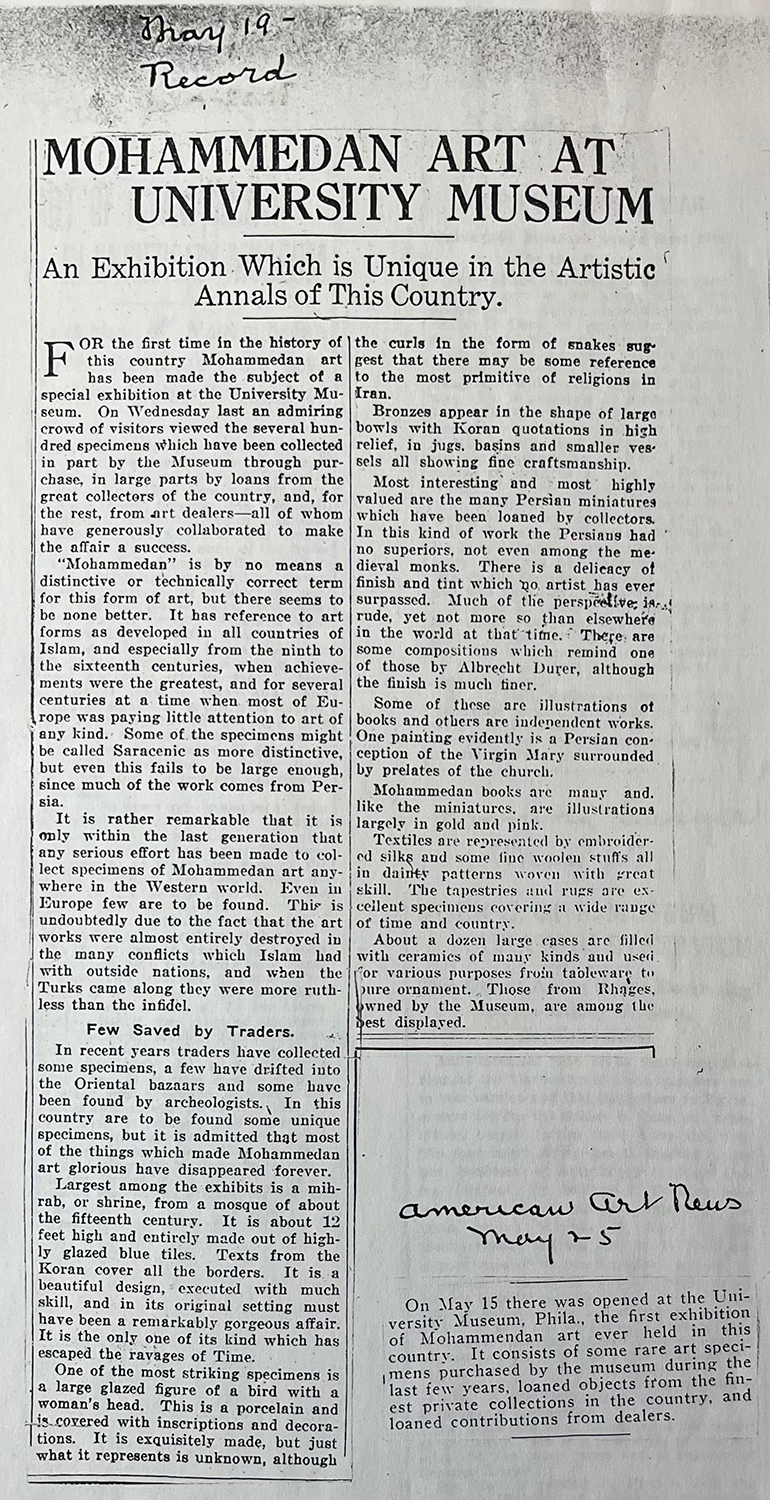

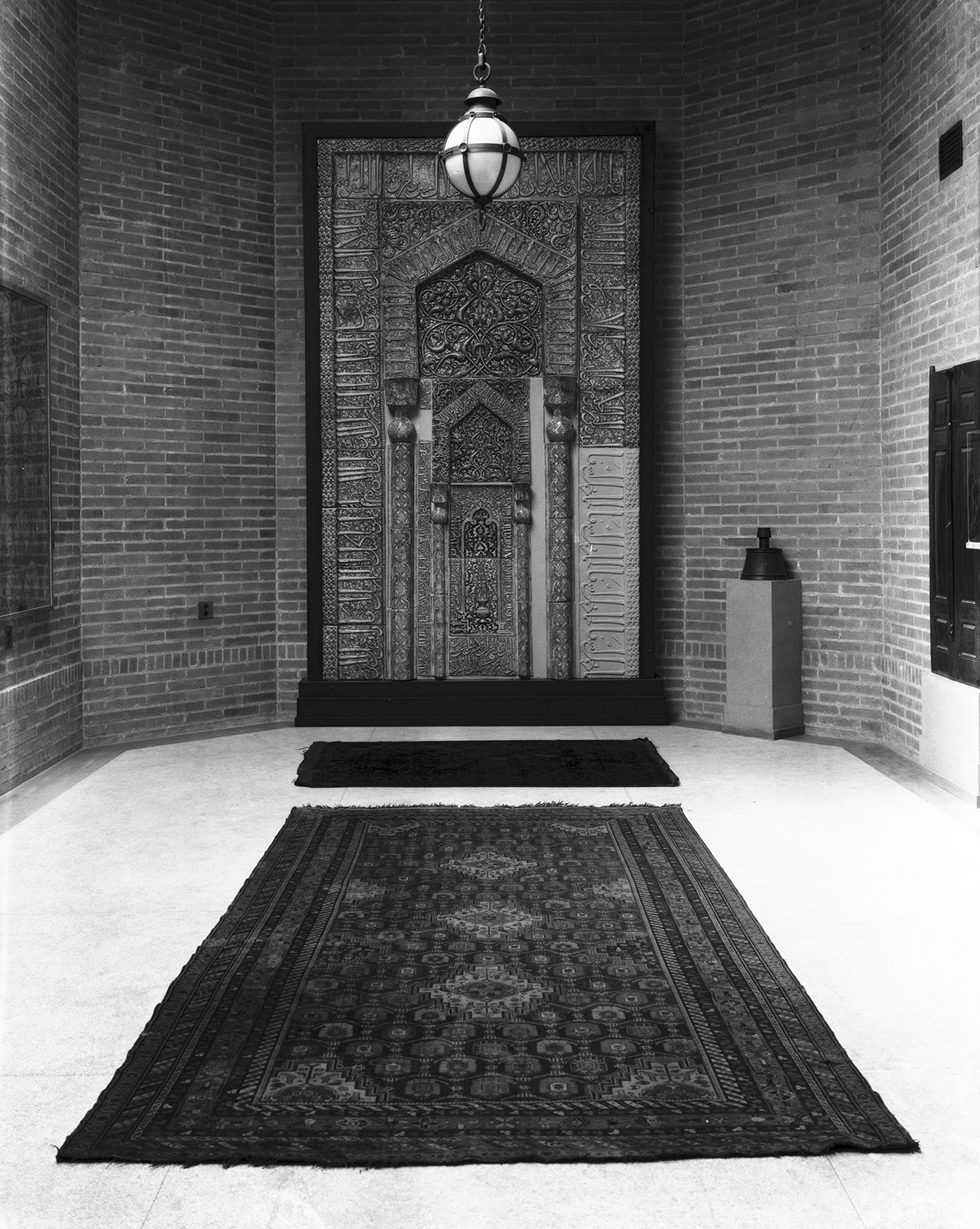

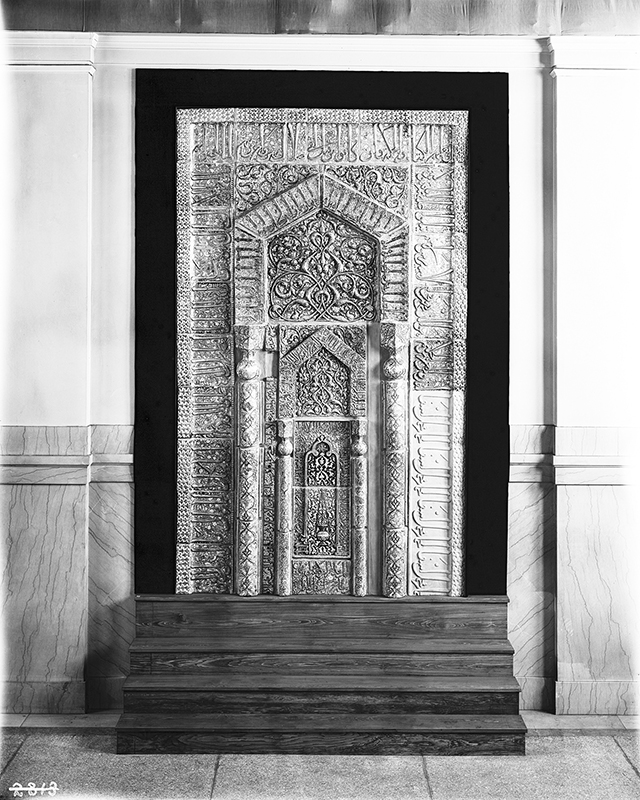

15 May–31 August 1918: Philadelphia

The mihrab is displayed for three and a half months in the Penn Museum’s “Exhibition of Mohammedan Art.” It is located at the far end of the exhibition in a stairway landing, elevated at the top of wooden steps, and placed in front of a black fabric in turn covering a door (fig. 97). Above the mihrab, more drapery covers a cast of the frieze of the Parthenon, part of the Classical galleries installed in 1899. The exhibition unfolds in the long gallery facing the mihrab, and the high ceilings accommodate several large carpets (fig. 98).

The mihrab’s missing tiles in between the columns and in the lower right are filled with white plaster. The tiles on the lower right—originally the basmala (the phrase that opens every sura of the Qur’an), followed by the first verse of sura al-Jumuʿah—are replaced with four identical pieces of molded plaster with الحمار یحمل اسفا. These words are borrowed from the second to last tile of the outer border, located in the lower left. In other words, a phrase at the end of the inscription is repeated four times at the start. This act of so-called reconstruction reveals a disregard for the mihrab’s sacred verses—which glorify God, his Messenger, and the sacred verses themselves—reducing them to meaningless and repetitive decorative filler. The individuals responsible for this intervention were clearly not familiar with the text, and the missing words could have been replicated with relative accuracy.

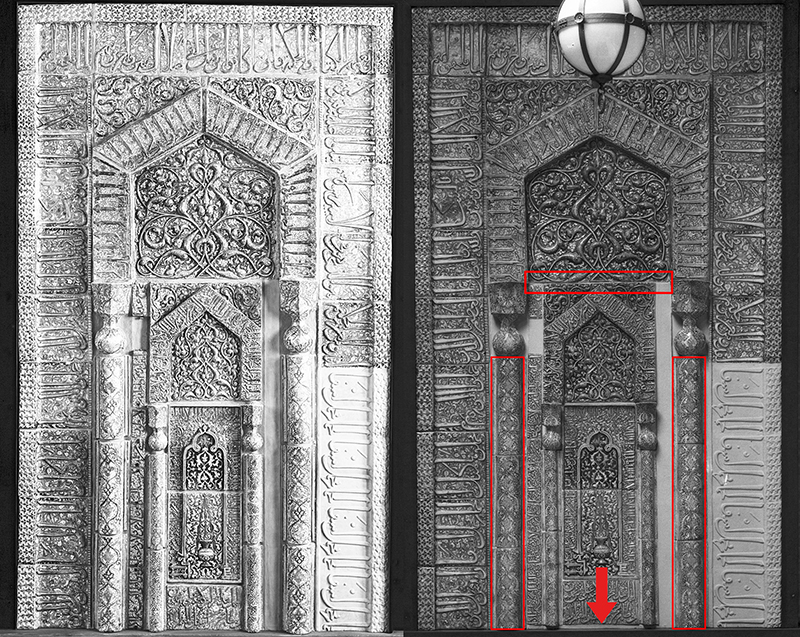

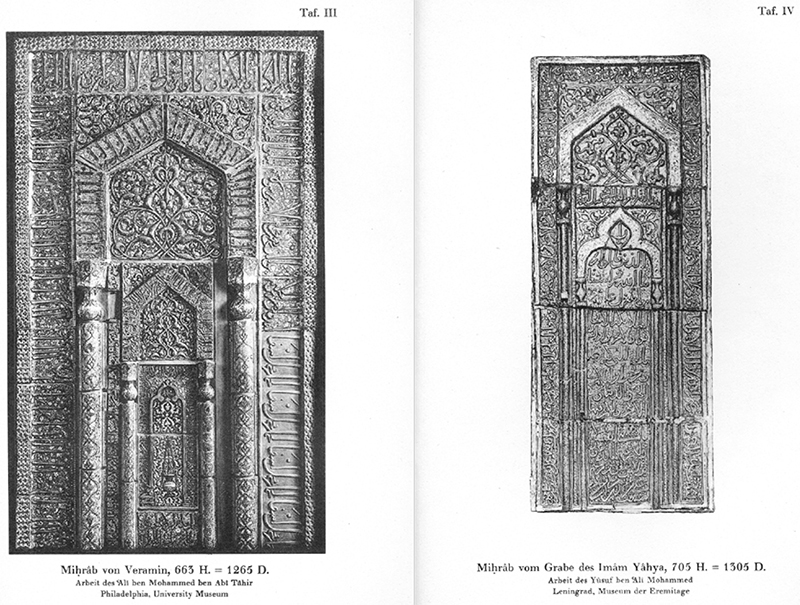

A comparison of the Penn Museum photograph to the one reproduced by Sarre in 1910 reveals that the mihrab had undergone some changes since entering Kevorkian’s possession (fig. 99). One notable change is the restoration of damaged areas visible in the older photograph, particularly along the outer border tiles. Some of the individual tiles are also rearranged. The three tiles comprising the bases of the large columns, with thin inscriptions along their edges, are altered, as are some of the thinner tiles framing the inner niche, which had already been disrupted in 1910.

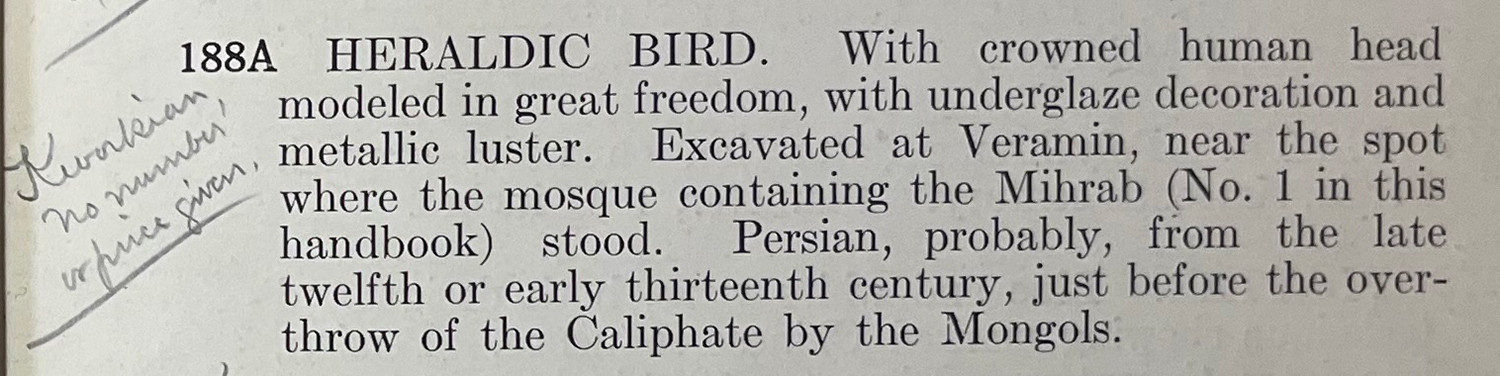

The mihrab is the first piece in the university’s small catalog, which properly records the potter and date but again vaguely mentions a “mosque” (vid. 6):

This Mihrab appears to have stood in a mosque which antedated the Mongol conquest of Persia; but the inscription on the tablet at the bottom states that the Mihrab itself was executed by Ali, son of Mohammed, son of Ab-i-Tahir, and was completed in the month of Shaaban in the year of the Hegira 663 (1264 A.D.).

Video 6. The catalog of the “Exhibition of Mohammedan Art,” Penn Museum, 1918, showing the cover, table of contents, introduction, and entry no. 1 on the mihrab. The University Museum: Section of Oriental Art (1918), Exhibition Catalogues and Collection Guides, Box 10, Penn Museum Archives. Video by Hossein Nakhaei, 2025.

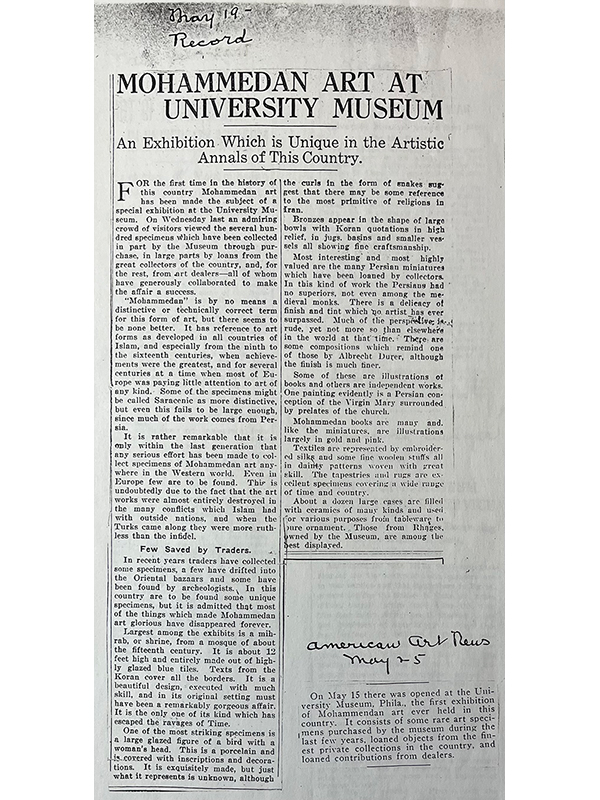

A review of the exhibition in The Philadelphia Record implies that it was highly admired but also misunderstood (fig. 100):

Largest among the exhibits is a mihrab or shrine, from a mosque of about the fifteenth century. It is about 12 feet high and entirely made out of highly glazed blue tiles. Texts from the Koran cover all the borders. It is a beautiful design, executed with much skill, and in its original setting must have been a remarkably gorgeous affair. It is only one of its kind which has escaped the ravages of Time.137

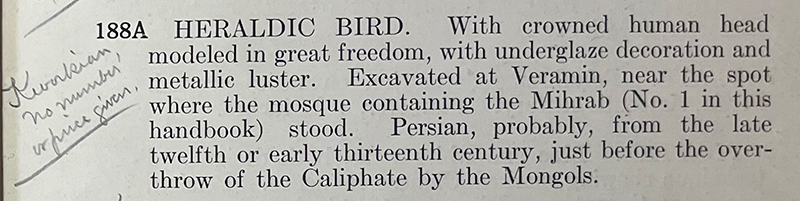

The exhibition also includes a large luster human-headed bird (harpy) belonging to Cora Timken Burnett (d. 1956) (fig. 101). In the catalog entry, Kevorkian mentions that the piece was “excavated at Varamin, near the spot where the mosque containing the Mihrab (No.1 in this handbook) stood” (fig. 102). This claim is questionable on several levels, and Kevorkian was clearly using Varamin and the mihrab as geographical and cultural references to heighten the appeal of other examples of luster. Moreover, his mention of “the mosque” might have perpetuated the misunderstanding that the mihrab came from the city’s congregational mosque.

April 1919: New York and Philadelphia

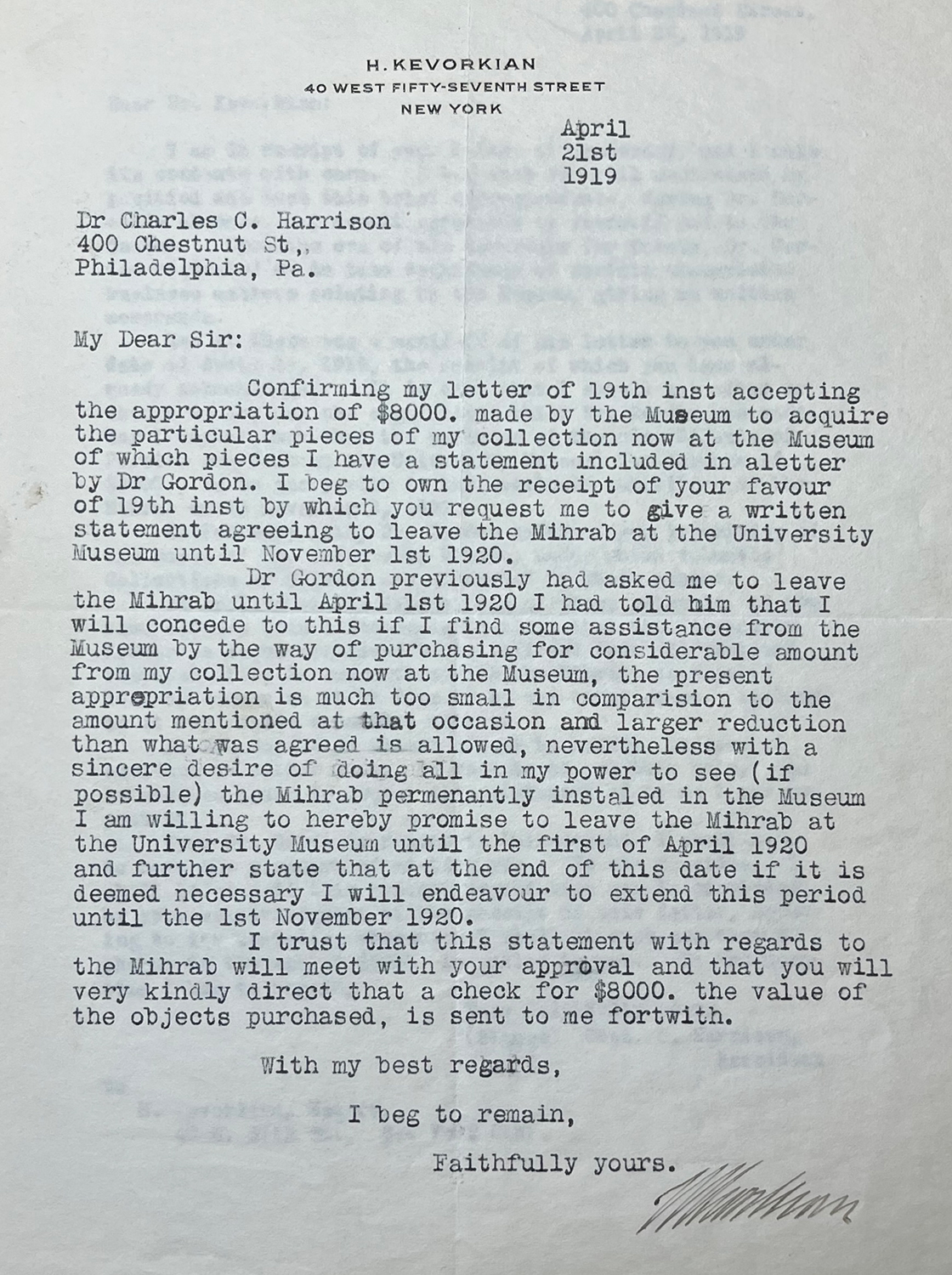

Kevorkian receives a letter from the New York branch of Debenhams, written in concert with “our London house,” and ordering him to arrange the “immediate return of the mihrab to New York” (fig. 103). This letter shows that Debenhams still played a—if not the—decisive role in the mihrab’s fate. Following the receipt of this letter, Kevorkian writes to Charles C. Harrison, head of the Board of Managers, insisting that the museum finally purchase the nine pieces of Persian art valued at $8,000 ($155,198 in August 2025), which would allow the mihrab to remain at the museum for another year, through 1 April 1920 (fig. 104). The museum finally pays the amount, and the mihrab ends up staying in the museum not just for one more year but two decades.

1922: Tehran

The Society for National Heritage (انجمن آثار ملی) is established by a group of intellectual elites to “preserve and restore historical buildings and to honor the legacy of Iran’s artistic and cultural achievements” (fig. 105).138 Mostowfi al-Mamalek, who was involved in the taking of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab to Paris in 1900 and its sale to Kevorkian in 1912–13, is among the founders of the Society.139 His participation in both dismantling and preserving cultural materials over more than twenty years can be read against broader sociocultural shifts in Iran. The indifference to culture heritage exhibited by some Qajar elites and courtiers during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—recall Sepahsalar’s orders facilitating transport (see 1875–76), Naser al-Din Shah’s offhand remarks in Paris (see 1889), and many excavation concessions (see 1900, 1912)—soon shifted into a growing climate of nationalism. During the Qajar to Pahlavi (1925–79) transition, powerful figures such as Mostowfi al-Mamalek could rebrand themselves as guardians of the nation’s past.

In early 1925, the Society for National Heritage starts to invite foreign scholars to Iran to deliver lectures and contribute to the documentation and study of Iranian art and architecture. Among the first scholars to visit are German archaeologist and art historian Ernst Herzfeld (d. 1948) and American art historian and dealer Arthur Upham Pope (d. 1969), both of whom are important figures in the historiography of the mihrab and Emamzadeh Yahya complex.

1923: Varamin

German archaeologist-art historian Ernst Herzfeld (d. 1948) visits the Emamzadeh Yahya and writes a complete transcription of the tomb’s stucco inscription (fig. 106). He records the name of the shrine as the “Imāmzâdeh Yahyā” and its location as “Kuhnagil” (Kohneh Gel). By the time of Herzfeld’s visit, all of the tomb’s luster tilework had been stolen, and the Emamzadeh Yahya had undergone its significant reconfiguration. It was perhaps unrecognizable from the complex reproduced in Sarre’s Denkmäler, and this may explain why Herzfeld failed to realize, in a later article, that the tomb with the stucco inscription was also once home to the increasingly famous luster mihrab: “Die andere Moschee, die einst den wundervollen, gestohlenen Goldlüster Mihrāb besaß, ist verschwunden” (the mosque, which once had the wonderful stolen golden luster mihrab, had disappeared).140

1925: Petrograd (St. Petersburg)

The large batch of tiles from the Emamzadeh Yahya acquired by the Stieglitz Museum in 1913 from Clotilde Duffeuty and stored in crates at the onset of the First World War are transferred to the State Hermitage Museum (map). Ernest K. Querfeld (d. 1949), curator and director of the Stieglitz Museum, writes a report to Joseph A. Orbeli (d. 1961), curator of the Near Eastern collections at the Hermitage, providing information about the 1913 acquisition (fig. 107).

1925: Philadelphia

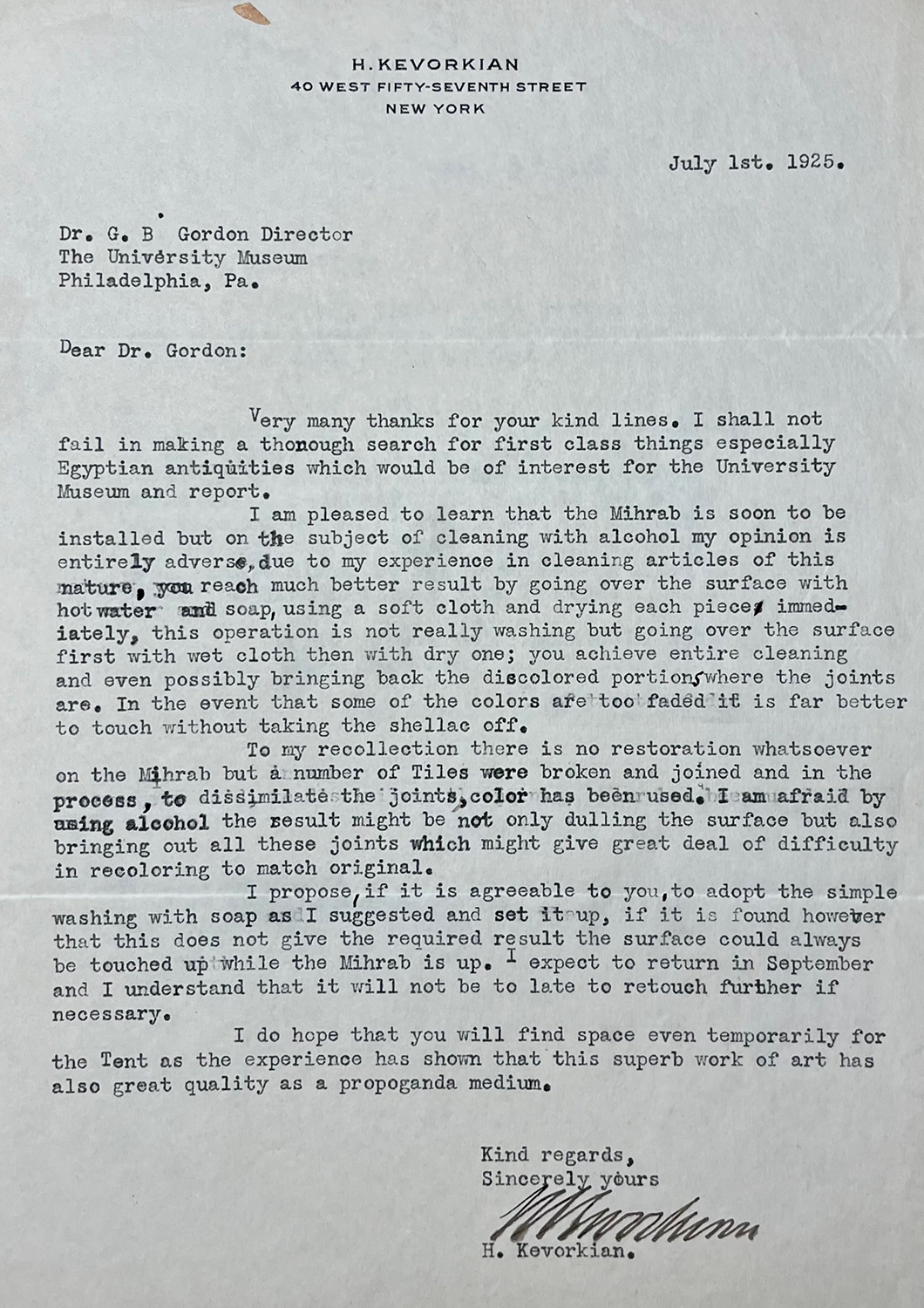

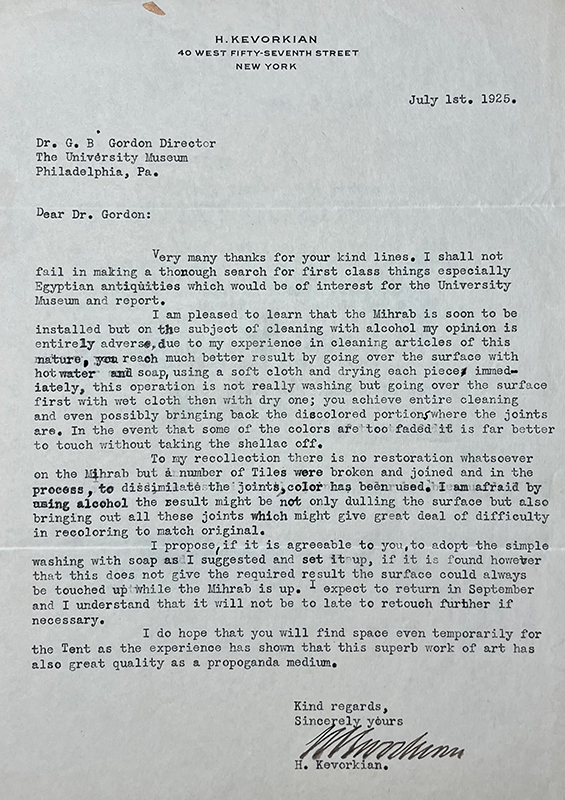

Back in the United States, and in advance of the mihrab’s reinstallation in the Penn Museum, Gordon and Kevorkian exchange a series of letters about the mihrab’s physical condition. In one letter, Gordon asks Kevorkian for his opinion on cleaning the mihrab’s tiles. Gordon proposes using alcohol to “bring out the lustre,” noting that while alcohol could clean the surface, it might also remove the paint and shellac applied during earlier restorations, which had yellowed over time.141 In response, Kevorkian recommends using hot water and soap with a soft cloth and drying each piece immediately (fig. 108). He questions that there were major previous interventions but concedes that some tiles had been broken and subsequently repaired by painting over the cracks. In response, Gordon mentions that a large part of the mihrab is restored and encourages Kevorkian to examine it carefully once he gets a chance.142

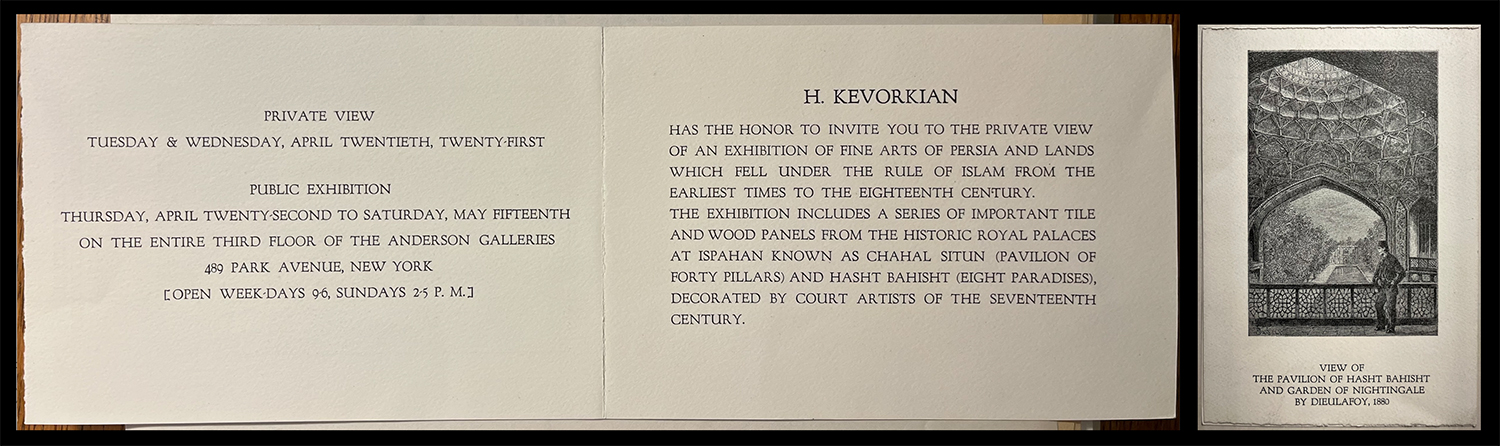

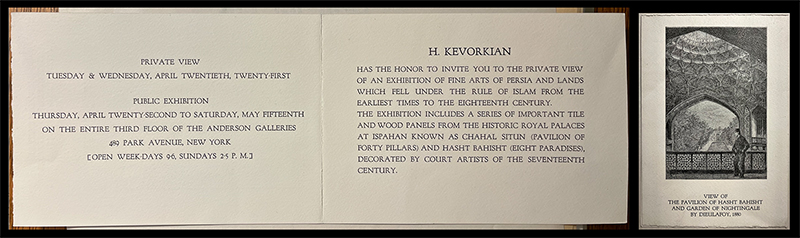

20 April–15 May 1926: New York

Kevorkian displays his Persian art collection at Anderson Galleries in New York (map). In advance of this exhibition, which was truly a sale, Kevorkian sends letters and private viewing invitations to many colleagues and potential buyers (fig. 109). He explains to Gordon (Penn Museum) that the purpose of the exhibition is “to afford to museum authorities and curators proper accommodation of inspection with minimum loss of time.”143 Kevorkian reserves several pieces for Gordon’s inspection, including a pair of doors said to be from the Chehel Sutun in Esfahan. He writes to the director, “I have been looking forward to have you see my collection of manuscripts and miniatures for a long time, I therefore, hope that you will not fail to honor me by visiting the exhibition.”144

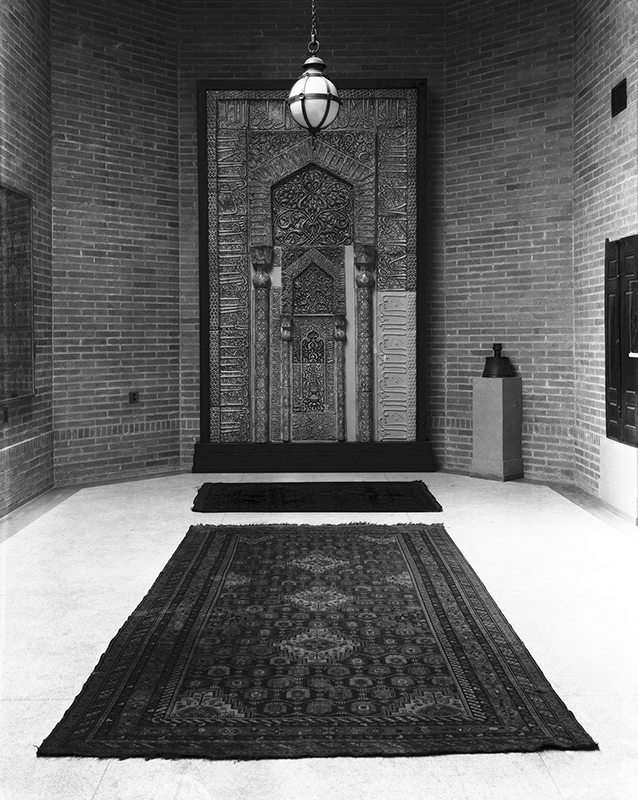

May–November 1926: Philadelphia

On 18 May, the Eckley Brinton Coxe Junior Egyptian Wing opens at the Penn Museum. The wing includes twelve rooms, and the mihrab is installed in one of the side rooms dedicated to Persian art, in front of a narrow brick wall (fig. 110). Nearby is a possibly Ilkhanid-period candlestick, a likely Safavid-period wooden door with some figural designs, and an Ottoman silk velvet.145 The plaster and inscriptional fills added before the 1918 exhibition (the first display in the museum) remain in place. The inner part of the mihrab is now set slightly higher so that the gap between the large triangular hood and the smaller niche below is closed. As a result, a gap now appears at the base, beneath the panel with the signature and date (fig. 111). In its original configuration, a row of horizonal tiles occupied this space (see fig. 63). This row of tiles has never been reproduced in the mihrab’s many installations abroad.

The mihrab’s exhibition at the Penn Museum overlaps with Philadelphia’s hosting of the First International Congress on Persian Art and Archaeology, orchestrated by Arthur Upham Pope in conjunction with the Sesquicentennial International Exposition (31 May–30 November). The exposition’s Persian Pavilion replicates and mixes aspects of Sassanian and Achaemenid architectural heritage, including the reliefs of Naqsh-e Rostam (map), as well as Safavid-period mosques in Esfahan like the Masjed-e Shah (map).146

30 January 1927: Philadelphia

George Byron Gordon, director of the Penn Museum, dies suddenly in an accident. The relationship he had developed with Kevorkian since at least 1914 was instrumental in bringing the mihrab to Philadelphia and keeping it there for over a decade. Between 24 June 1915 and 23 December 1925, the Penn Museum—under Gordon’s leadership—paid Kevorkian a total of $133,350 for almost eighty works of art.147 This scale of transaction underscores the extent of the professional relationship between the director and dealer, which in turn bolstered the case for keeping the mihrab in the museum permanently. As recorded by Kevorkian (see the last line in fig. 112), this was apparently Gordon’s long-term intention.

Although the mihrab remains in the Penn Museum for the next thirteen years, Gordon’s death likely plays a pivotal role in determining its ultimate departure from the institution. In the weeks following Gordon’s death, Jane M. McHugh, Secretary of the Board of Managers, reaches out to Kevorkian about his “property” in the museum, including the mihrab and sixteen other objects, including many works of ancient Egyptian art.148

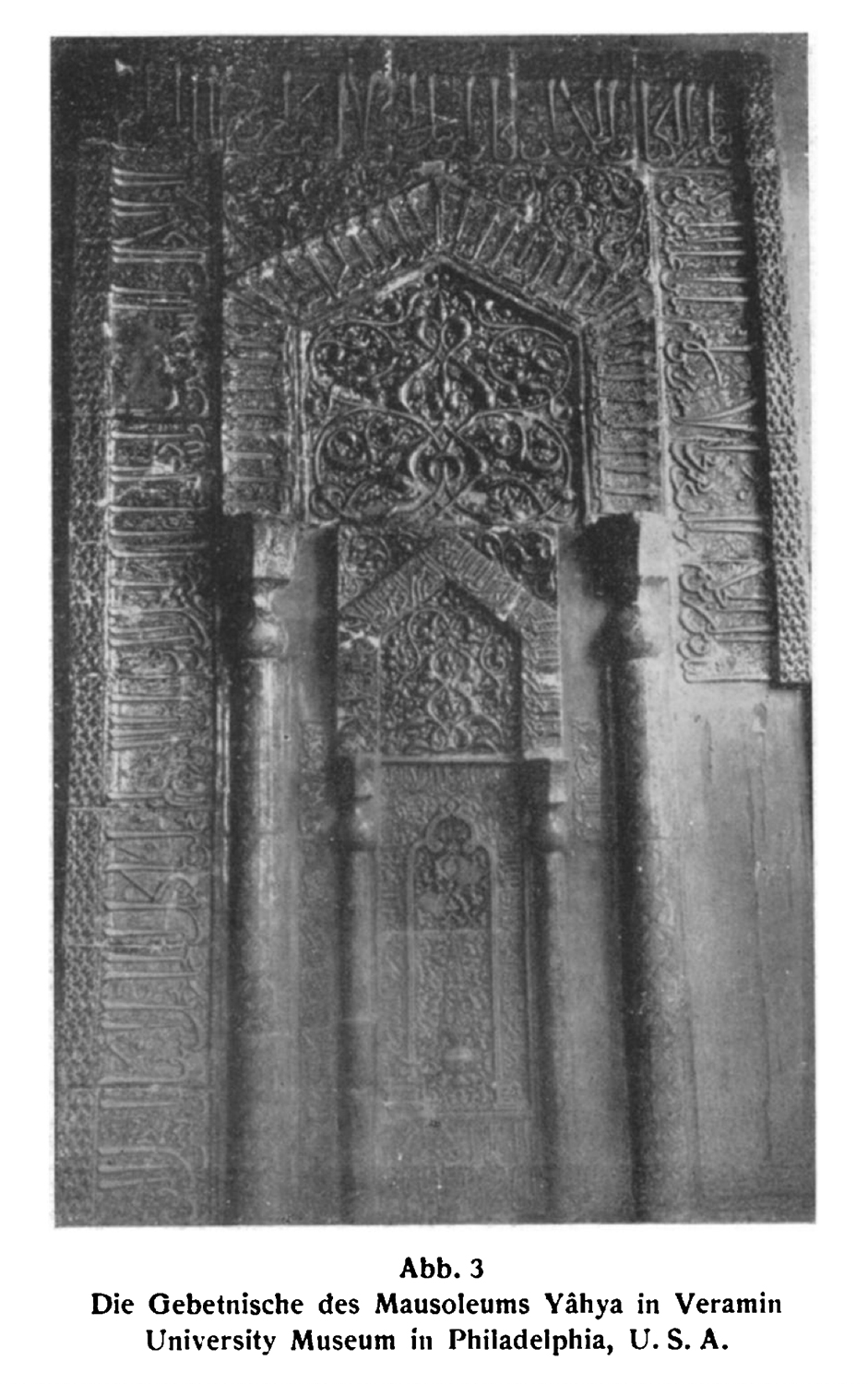

1927–28: Berlin

Friedrich Sarre, now the director of the Islamic department at the Kaiser Friedrich Museum (today’s Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, or State Museums of Berlin) reaches an agreement with Vincent Robinson & Co. (see 1913) to acquire the luster mihrab from Kashan’s Masjed-e Meydan. The agreed price for this mihrab and a set of two large tiles attributed to a shrine in Qom (no. 2 in the Preece catalog) is £6,900 ($33,534).149

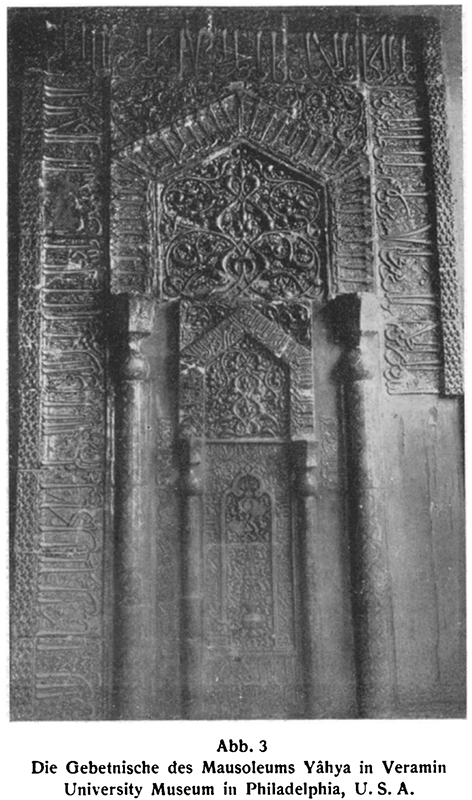

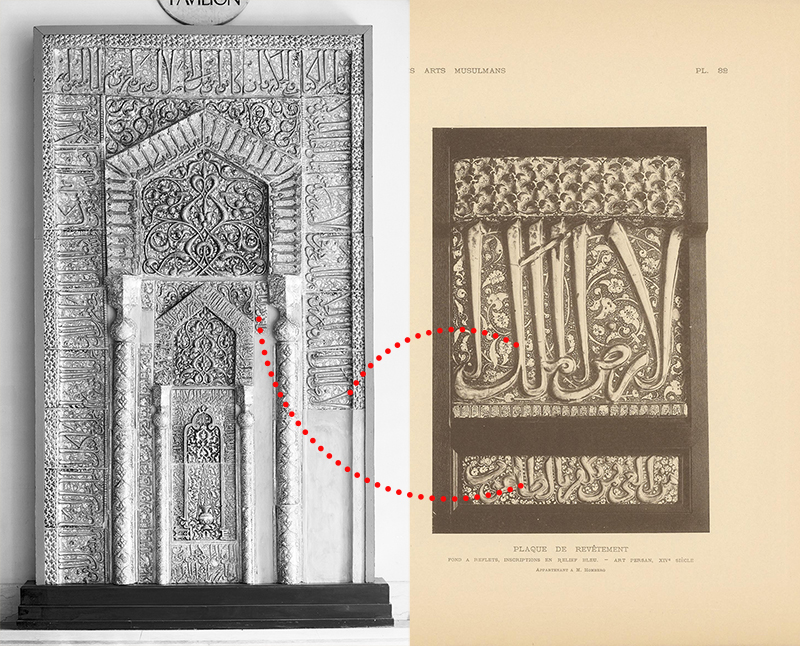

In an article written on the occasion of these acquisitions, Sarre reproduces the same photograph of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab that he first reproduced in 1910 (fig. 113). He draws a direct line between the West’s (Abendland) collecting of medieval Persian ceramics and the destruction of most of Iran’s mihrabs.150 He then highlights the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab as the only other mihrab sent abroad relatively intact. The caption lists it as in the “University Museum in Philadelphia, U.S.A.”

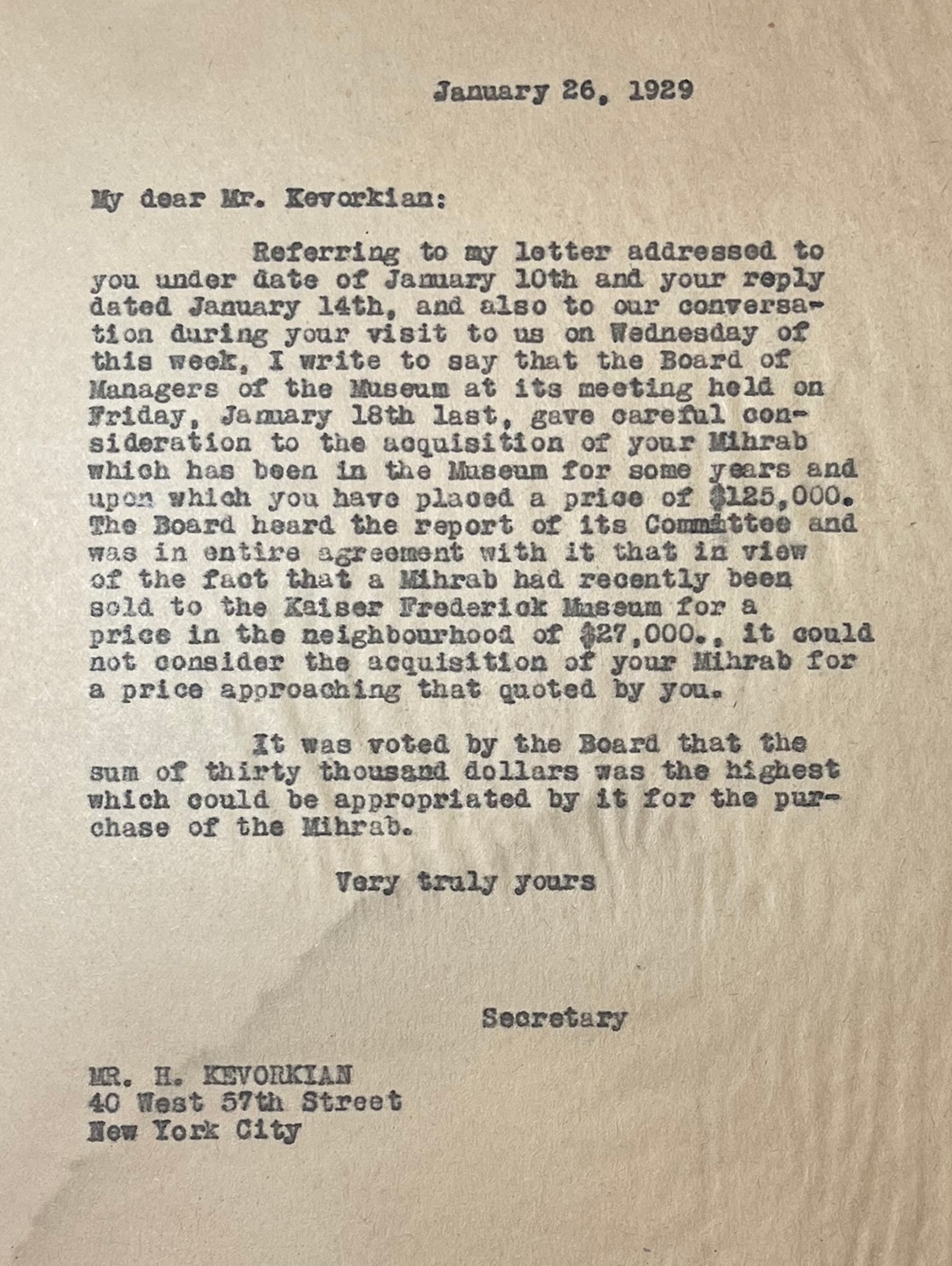

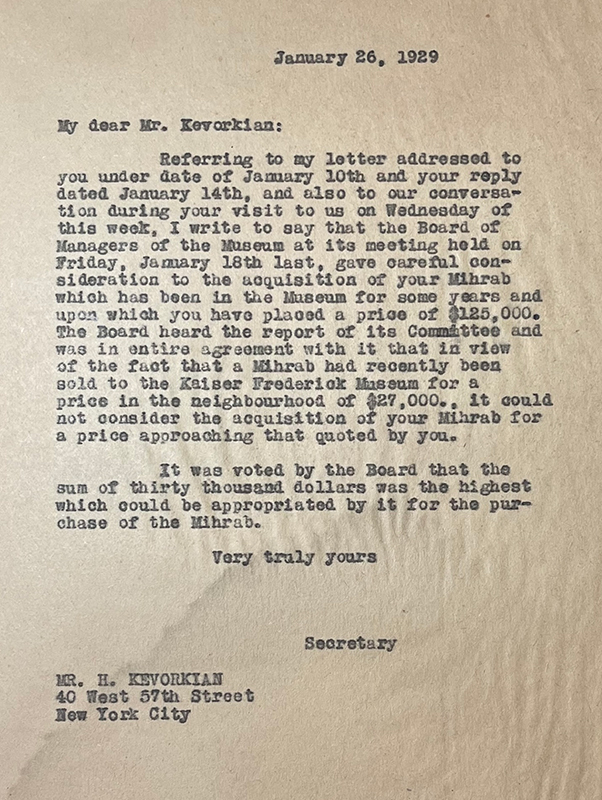

January 1929: Philadelphia

The Board of Managers of the Penn Museum, led by Charles C. Harrison, reaches a decision about the purchase of the mihrab. After “careful consideration,” the Board concludes that Kevorkian’s asking price of $125,000 is far too high. As a point of comparison, they cite the sale of the Masjed-e Meydan’s mihrab to the Kaiser Frederick Museum in Berlin for $27,000 (see 1927–28) (fig. 114). The maximum amount that the museum can offer for the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab is $30,000 ($568,378 in August 2025).

November–December 1930: Philadelphia

In late 1930, Kevorkian, Horace H. F. Jayne (d. 1975), the new director of the Penn Museum, and Myron Bement Smith (d. 1970), secretary of the American Institute for Persian Art and Archaeology, enter into negotiations about the mihrab’s inclusion in the pending International Exhibition of Persian Art in London (fig. 115). The Penn Museum agrees to cover insurance and shipping to New York, and the exhibition committee will cover all other expenses from New York to London and the return, if Kevorkian decides to bring it back to the United States.

Smith, Jayne, and Kevorkian also discuss the tiles missing from the mihrab and believe that four tiles owned by American collector Horace Havemeyer (d. 1956) might belong to the outer border (fig. 116).151 After examining the tiles, Smith confirms that they “did not fit the Mihrab and we are therefore not sending them to London.”152 Havemeyer is known to have owned at least two tiles from the 734/1334 luster mihrab of the Emamzadeh ʿAli b. Jaʿfar in Qom (map), and it is likely that they were among the group of four.153 The potential mismatching of border tiles from the Qom (Emamzadeh ʿAli b. Jaʿfar) and Varamin (Emamzadeh Yahya) mihrabs was notable given their obvious visual differences, especially the outer lips in relief. As we shall see, the two mihrabs would continue to be confused.

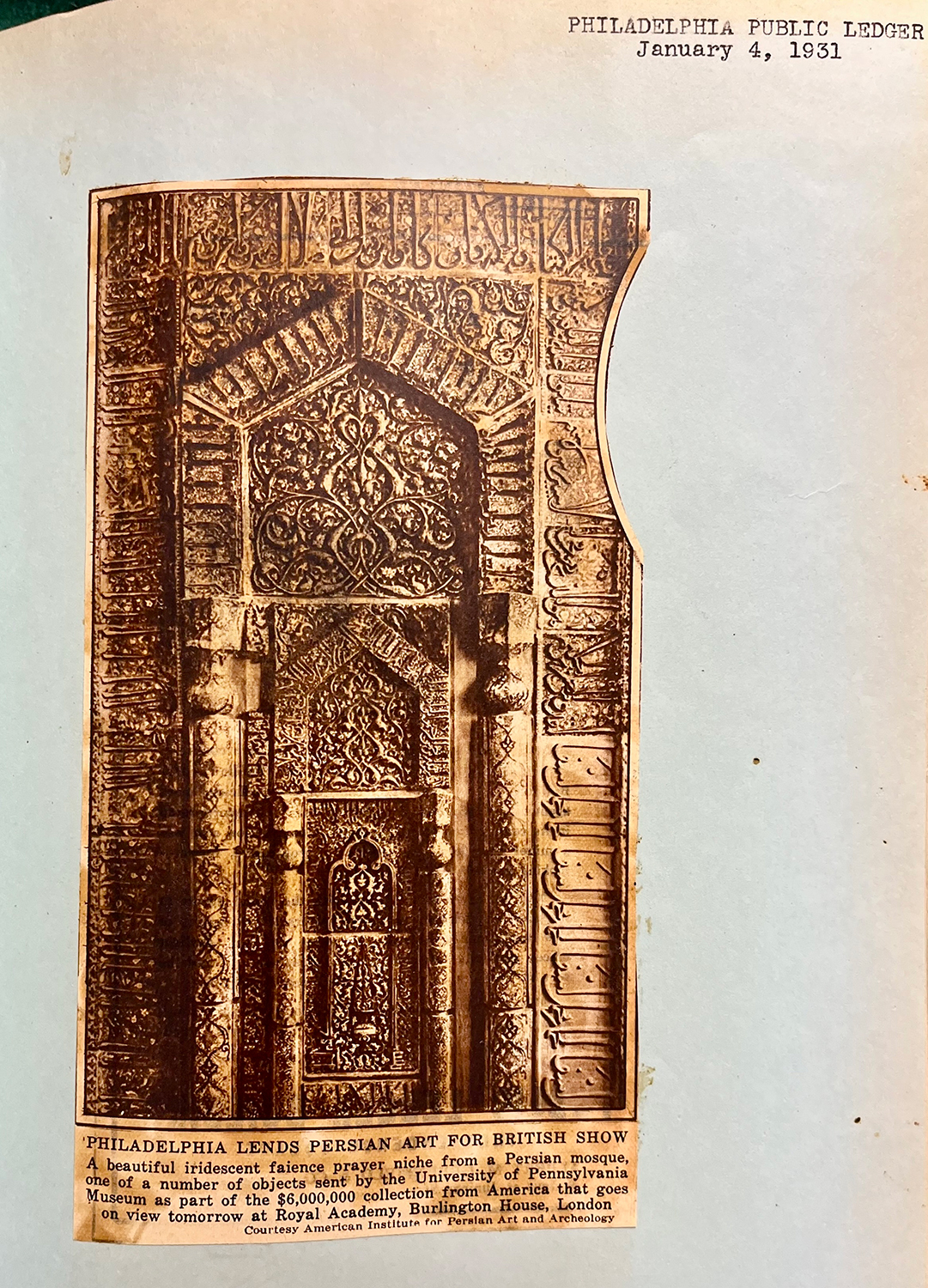

7 January–7 March 1931: London

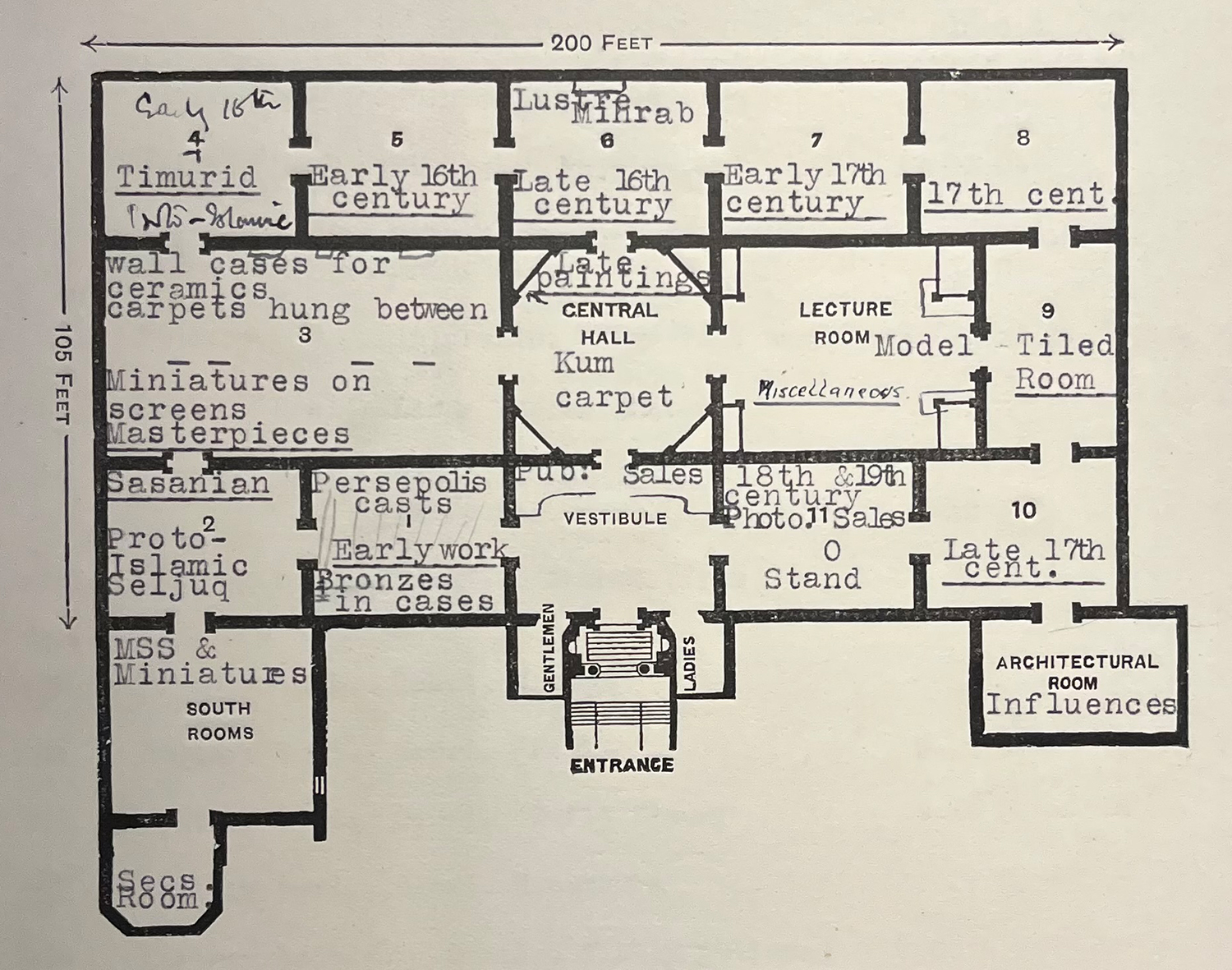

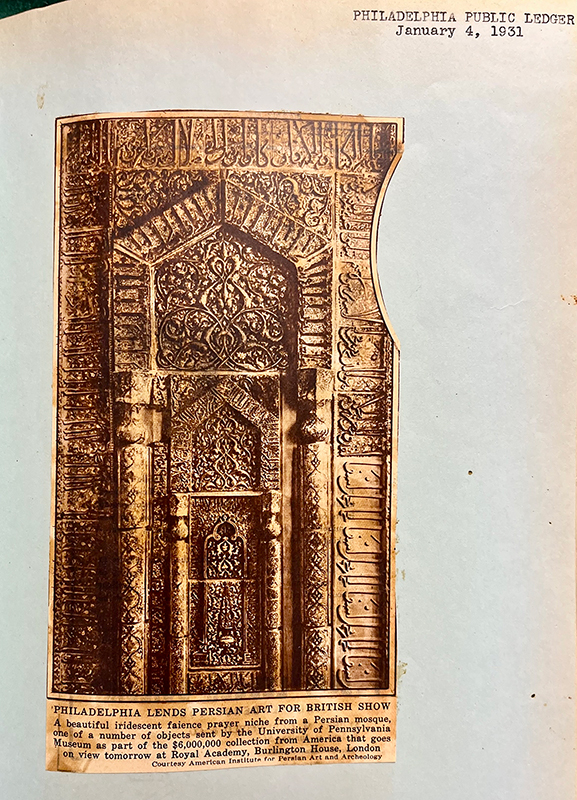

The mihrab is sent to London for inclusion in the momentous International Exhibition of Persian Art, part of the Second International Congress on Persian Art and Archaeology (the first in Philadelphia in 1926). The event is directed by Arthur Upham Pope and Reginald Blomfield (d. 1942) and sponsored by King George V of England (r. 1910–36) and Reza Shah Pahlavi (r. 1924–41) of Iran. The mihrab’s voyage to London is documented in a newspaper announcement whose caption highlights it as “a prayer niche from a Persian mosque” and “part of the $6,000,000 collection from America” sent to London (fig. 117). As a result, the mihrab is presented as an American contribution to the international event, rather than site-specific Iranian religious heritage.

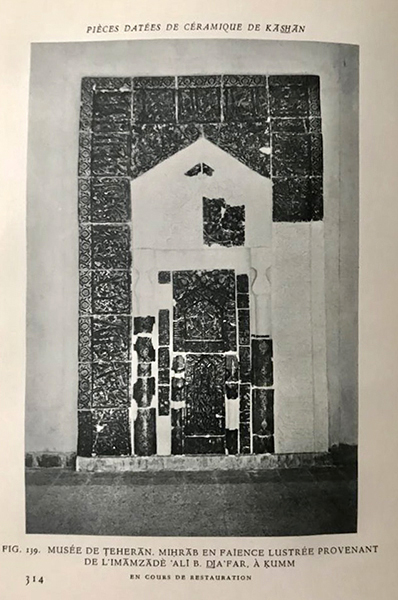

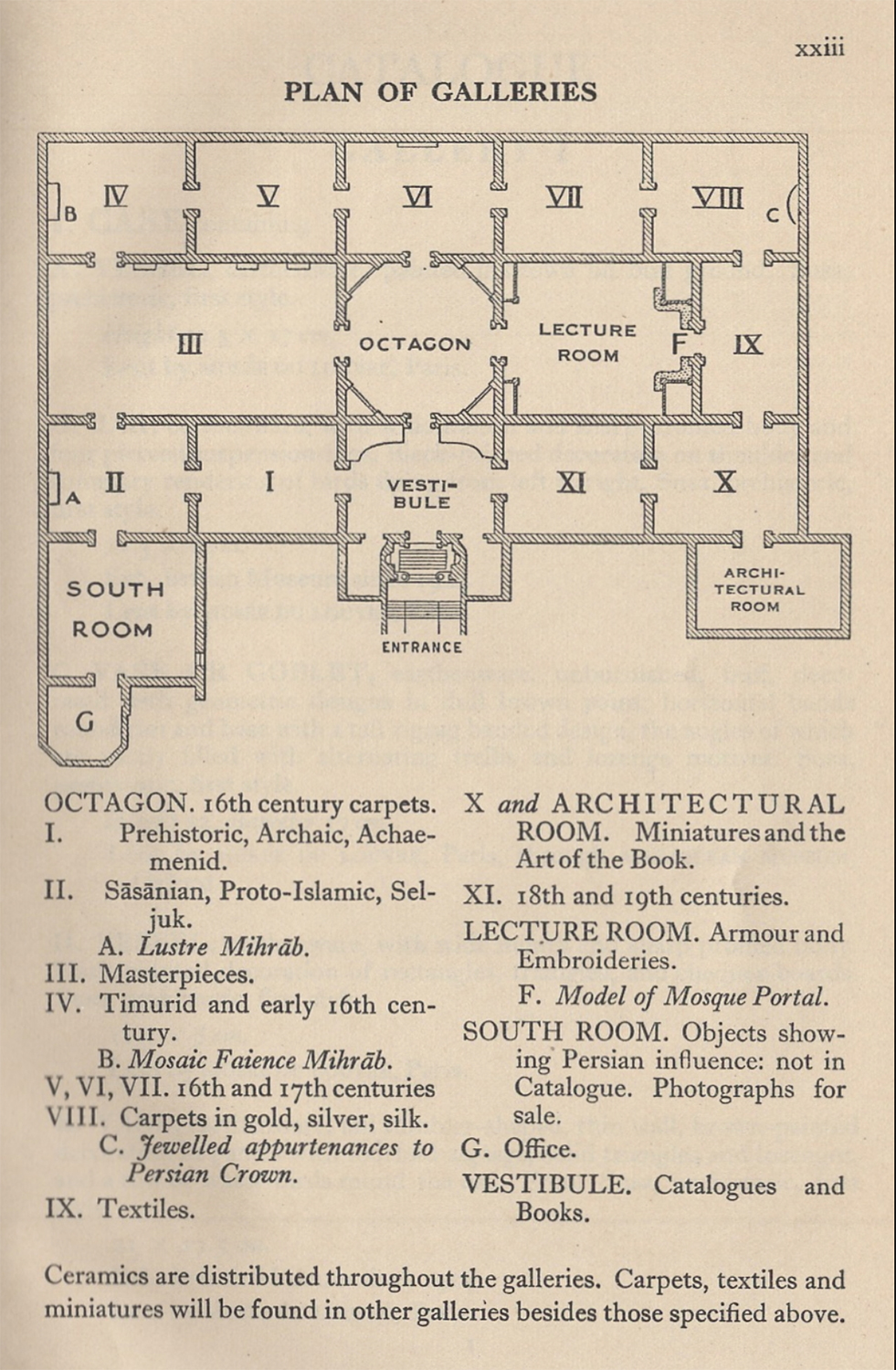

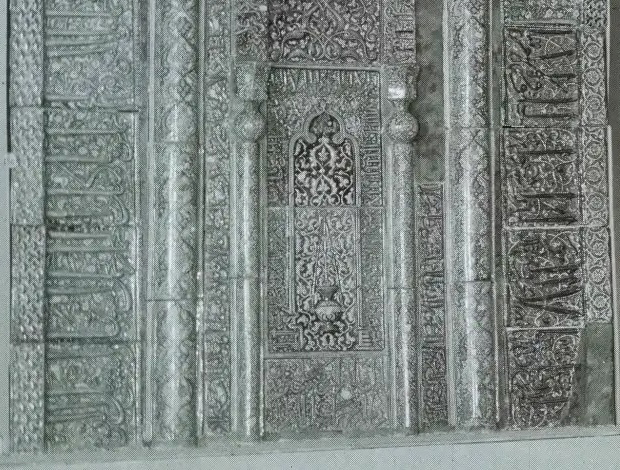

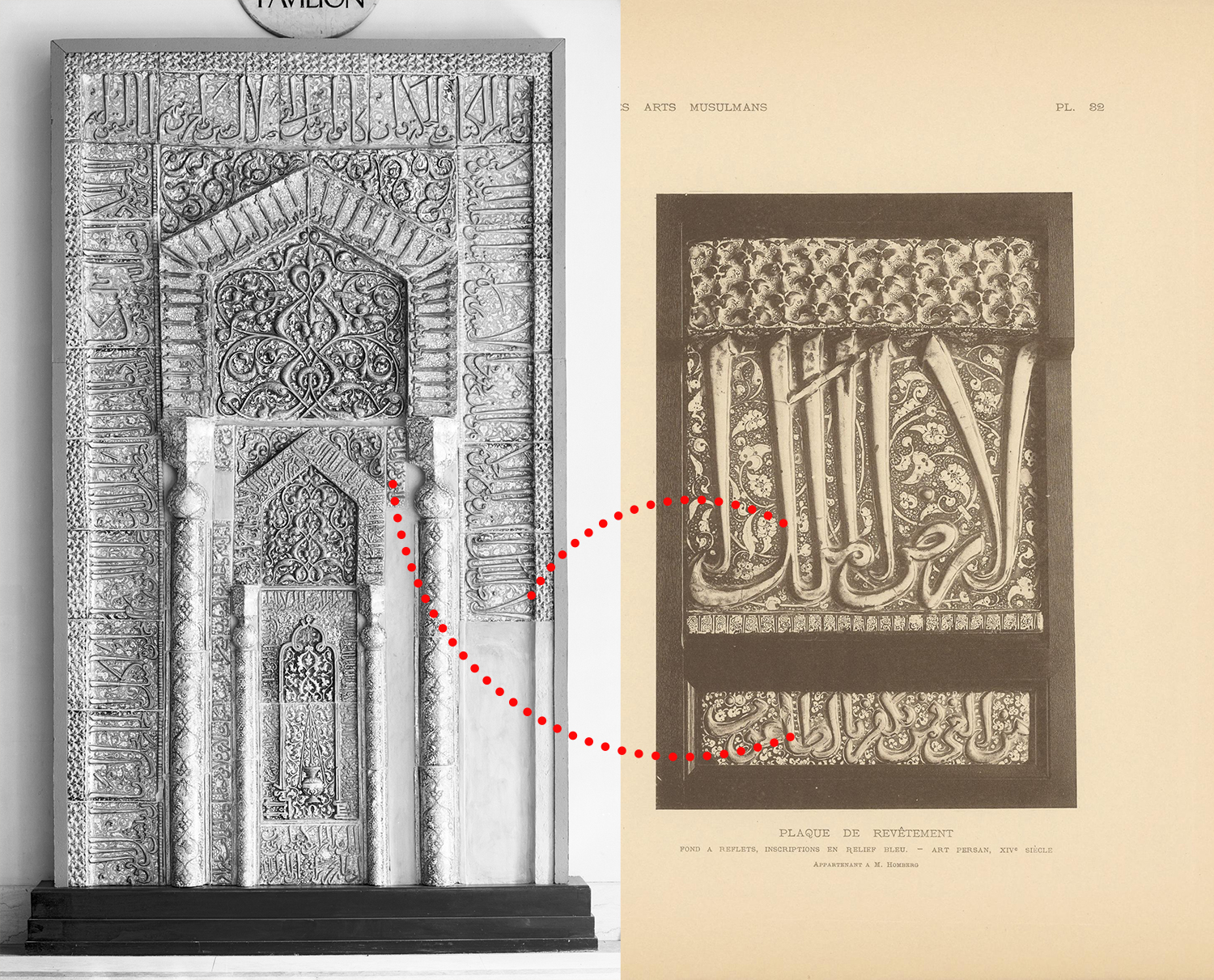

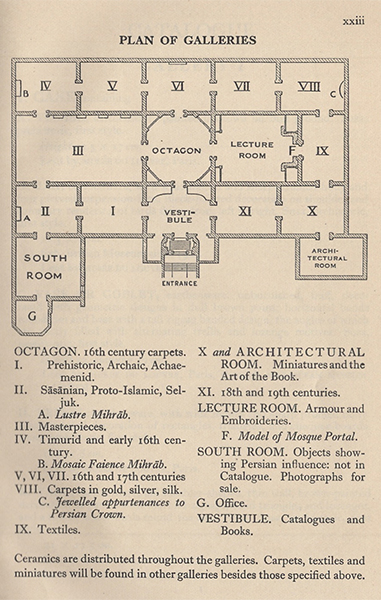

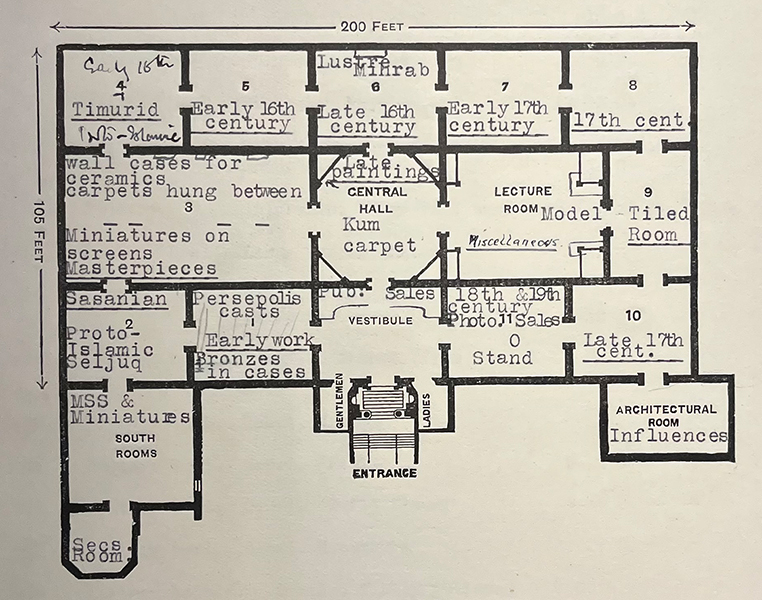

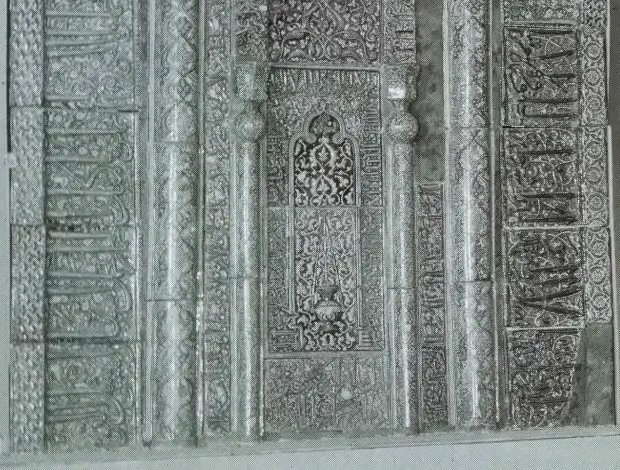

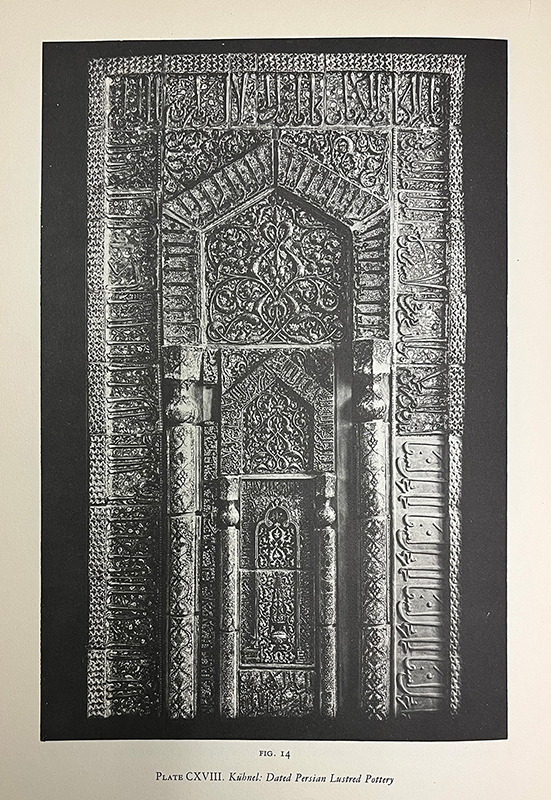

The exhibition includes over two thousand works of art lent by individuals and institutions from twenty-two countries, including Iran, and occupies almost all of the first floor of London’s Burlington House, part of the Royal Academy of Arts (map).154 The mihrab is displayed in a room at the back left (northwest) of the building, surrounded by carpets and luster tiles from different collections and sites (figs. 118–19). As in Philadelphia in 1918, it is elevated, but in this case, on a white pedestal. The mihrab’s importance to the exhibition curators is attested by an earlier plan of the galleries that positioned it on the main axis of the building, directly behind the central octagonal hall (figs. 120–21).

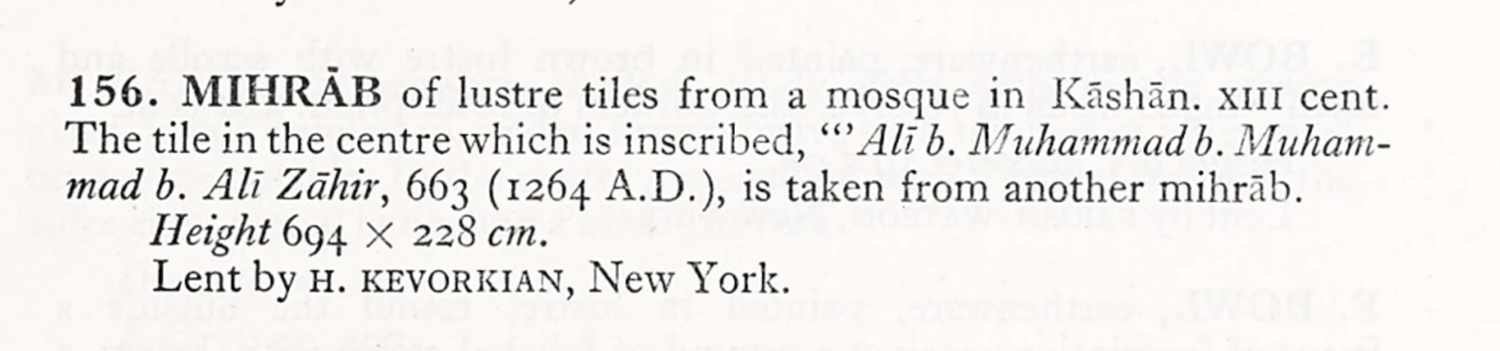

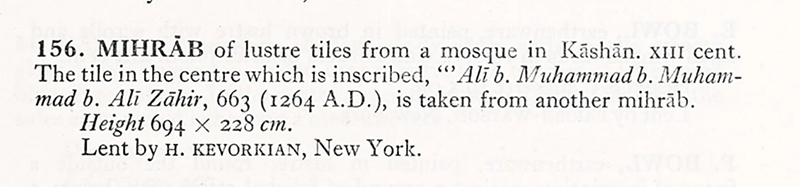

The catalog entry on the mihrab written by Russian historian Vladimir Minorsky (d. 1966) contains several errors (fig. 122). Most notably, it describes it as “from a mosque in Kāshān.” It also claims that the lower central panel bearing the date and name of the potter belongs to another mihrab, which is incorrect based on Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh’s reading of this tile in situ in 1876.155 The mihrab’s height is also inaccurately given as 694 centimeters (22.77 ft), almost double its actual height.

The problem of the border tiles missing from the lower right of the mihrab is resolved in London in a rather baffling, and possibly unprecedented, way. Four tiles from the aforementioned mihrab of the Emamzadeh ʿAli b. Jaʿfar in Qom are integrated into this area (fig. 123). These tiles have a different outer lip in relief, carry a different verse (the beginning of sura al-Aʿraf), and are themselves installed out of order. What is further remarkable is that the tiles are likely loaned by Iran, which is known to have sent at least one tile from the Emamzadeh ʿAli b. Jaʿfar’s mihrab to the event.156 This tile was originally the last tile in the lower left of that mihrab, and in London, it is displayed as the first filler tile on the lower right of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab. This pastiching together of tiles from two different luster mihrabs underscores the lengths that curators and collectors would go to mix luster ensembles to convey the illusion of completeness.157 It is further surprising given that, in the lead up to the exhibition, Myron Bement Smith seems to have ruled out isolated tiles probably belonging to the Emamzadeh ʿAli b. Jaʿfar’s mihrab as a suitable fit the Emamzadeh Yahya’s. The London pastiche does not go unnoticed, and German scholar Ernst Kühnel (d. 1964) briefly mentions it in an article published soon after the exhibition.158

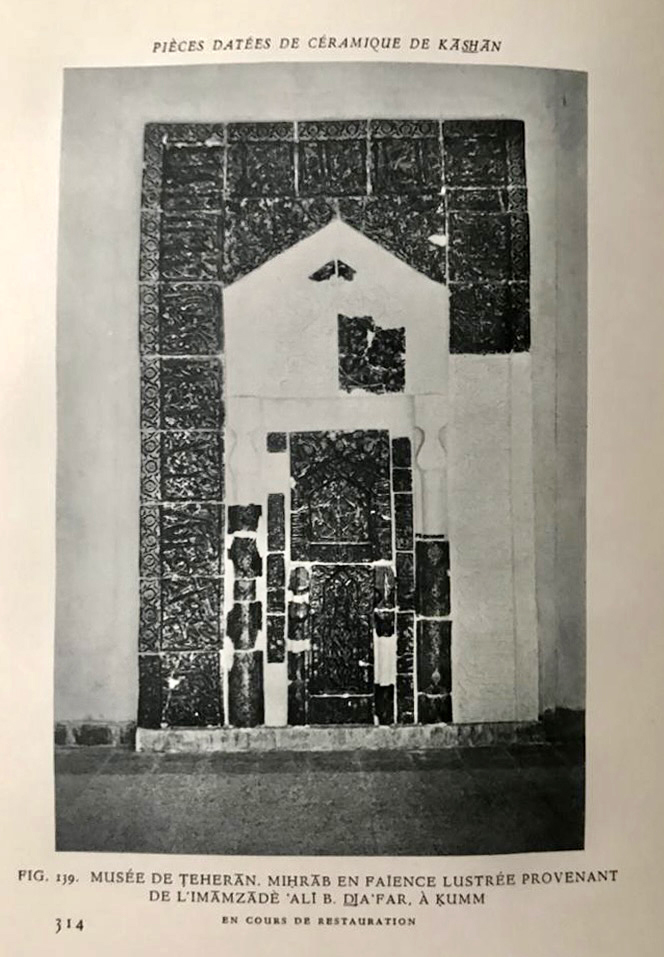

In addition to being integrated into the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab (Varamin), tiles from the Emamzadeh ʿAli b. Jaʿfar mihrab (Qom) are also displayed on their own. A spandrel from this mihrab’s hood (no. 161 in the catalog) is displayed to the right of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab, albeit with its two parts in the wrong orientation (see the far right of fig. 119).159 These tiles are ultimately sent back to Iran and kept out of public view until they are transferred to Tehran in the lead up to the opening of the National Museum (map) in 1937. That same year, French artist-art historian Yedda Reuilly Godard (d. 1976) publishes the first scholarly article on the Emamzadeh ʿAli b. Jaʿfar’s mihrab, and its reproduction shows its highly fragmented and poor condition, including many missing tiles (fig. 124). Today, this mihrab has been highly restored, and Godard’s photograph offers an important reminder of original parts, albeit already highly impacted (fig. 125).

A comparison of the mihrabs from the Emamzadeh Yahya (Varamin) and Emamzadeh ʿAli b. Jaʿfar (Qom) underscores how circumstances of removal and preservation could vary significantly. The targeting of the Qom tomb resulted in profound damage to its mihrab, literally tearing it apart. The removal of the Varamin mihrab was a more organized and methodical enterprise that left it relatively intact. In London, it was displayed as a relatively complete ensemble, whereas the Qom example, and some others, were presented in parts, either as fillers or isolated pieces. Finally, while the remaining parts of the Qom mihrab ultimately entered an Iranian museum (for other examples, see the Checklist, no. 16), the Varamin mihrab was exported and became ‘owned’ by foreigners.

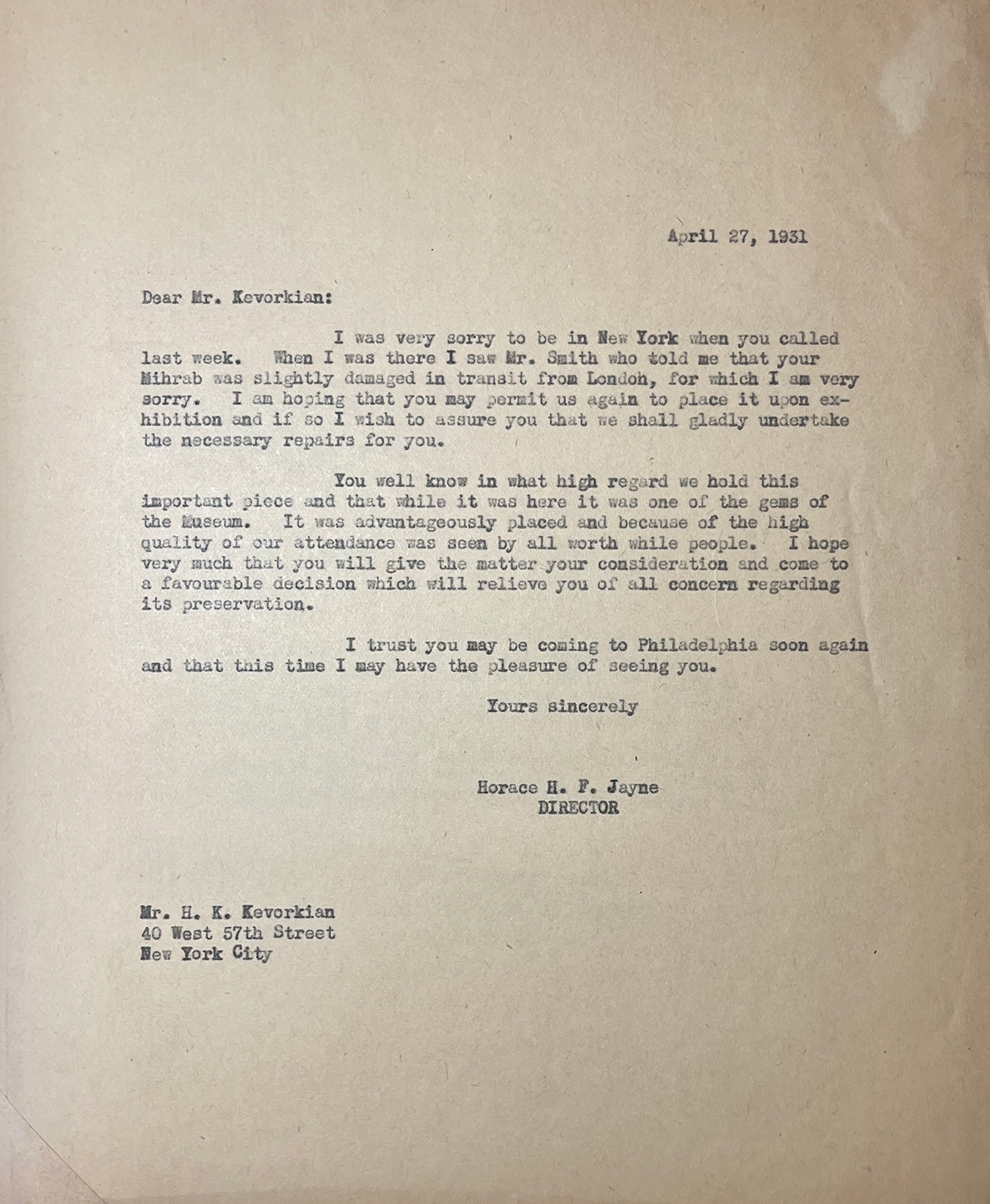

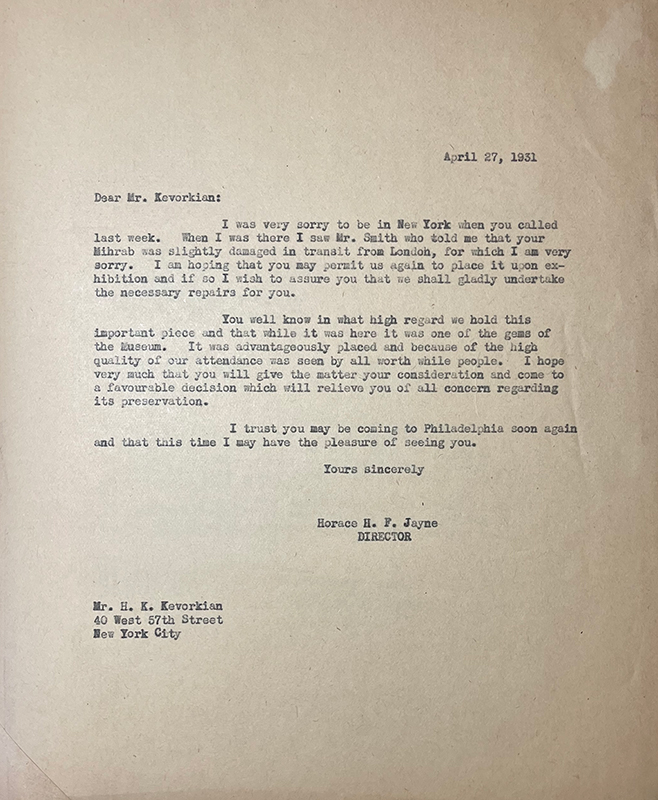

April–October 1931: Philadelphia

After the London exhibition, and during the mihrab’s shipment back to New York, some of its tiles are damaged. Jayne writes to Kevorkian acknowledging this damage and assuring him that the museum will cover the repairs (fig. 126). Jayne hopes to exhibit the mihrab in the museum once again, describing it as a “one of the gems of the Museum” when it was “advantageously placed and because of the high quality of our attendance was seen by all worth while [sic] people.” This language raises the question of audience and precisely who was deemed “worthwhile” to see the mihrab. It also presents a stark contrast to the mihrab’s original context, when it stood in a tomb accessible to ordinary visitors and pilgrims.160

“You well know in what high regard we hold this important piece and that while it was here it was one of the gems of the Museum. It was advantageously placed and because of the high quality of our attendance was seen by all worth while people.”

Kevorkian agrees to return the mihrab to Philadelphia and imposes new conditions, marking a shift in the dynamics of negotiation between the dealer and museum. Jayne’s response is conciliatory, and he accepts all of Kevorkian’s terms, including covering insurance and transportation from New York to Philadelphia. He also agrees to restore the damaged tiles (“one tile split in two from its old breakage and one of the smaller capitals broken into two parts”), label the mihrab as “lent by Mr. H. Kevorkian,” and display it in an elevated recession.161 Following these agreements, the mihrab is packed and shipped from the New York warehouse of Davies Turner & Co. (map) to Philadelphia by Messrs. Day & Meyer. The mihrab is displayed in the Penn Museum as of May 1931, making this its third known installation there (see 1918 and 1926).

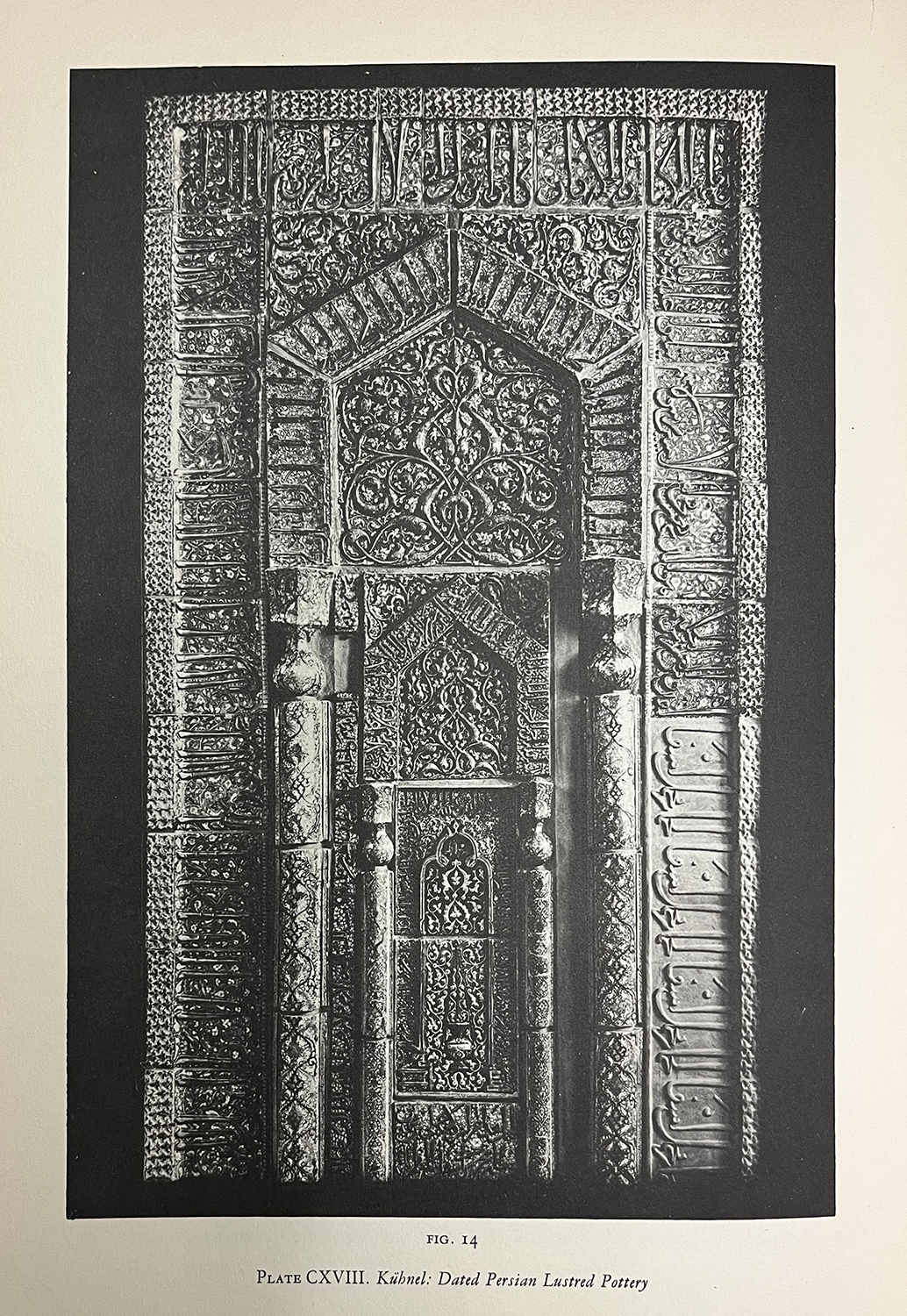

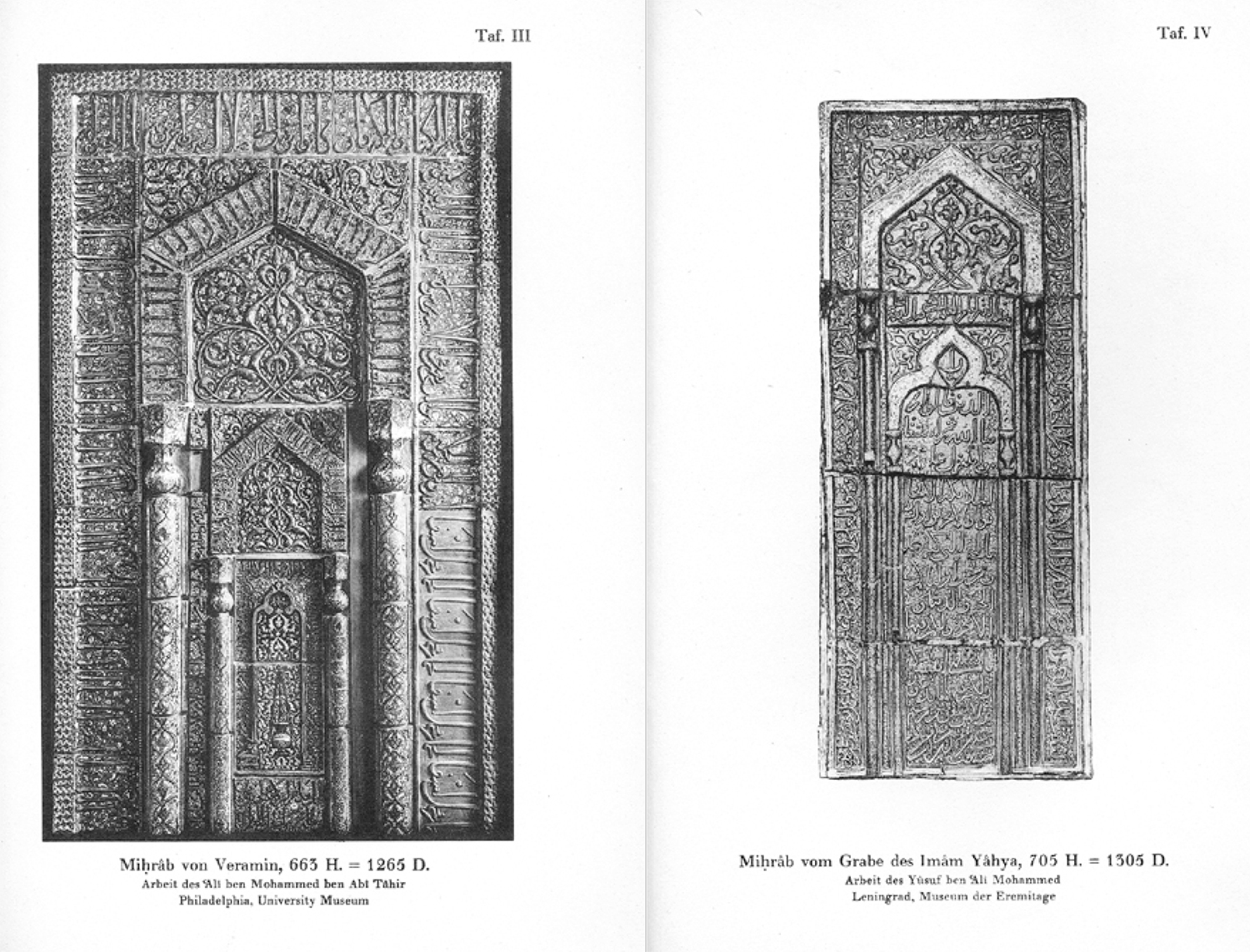

While the mihrab is en route back to Philadelphia, Jayne co-edits a volume in which Ernst Kühnel (d. 1964), who became director of the Museum für Islamische Kunst in October 1931, reproduces a photograph of the mihrab framed in black and likely taken during the 1918 exhibition at the Penn Museum (fig. 127). The German scholar corrects several errors in earlier studies, including Sarre’s misreading of the mihrab’s date. He also comments on the inclusion of four tiles from the Qom mihrab in the Varamin mihrab in London (“in the London Exhibition four foreign tiles dated 734 A.H. were used to fill the gap on the lower right”). Finally, he observes that the mihrab must have been taller than the exhibited version, noting the absence of the horizontal row of tiles between the columns.162 Despite these precise observations, Kühnel reiterates earlier incorrect claims that the lowermost tile with the signature and date were part of a different mihrab. He also describes several tombstone panels isolated from cenotaphs as mihrabs, including the 705/1305 panel naming “Emam Yahya” in the State Hermitage Museum. This confusion of two completely different elements—one set into a wall to orient prayer and the other part of the upper surface of a three-dimensional cenotaph—had long roots (see 1910-12).

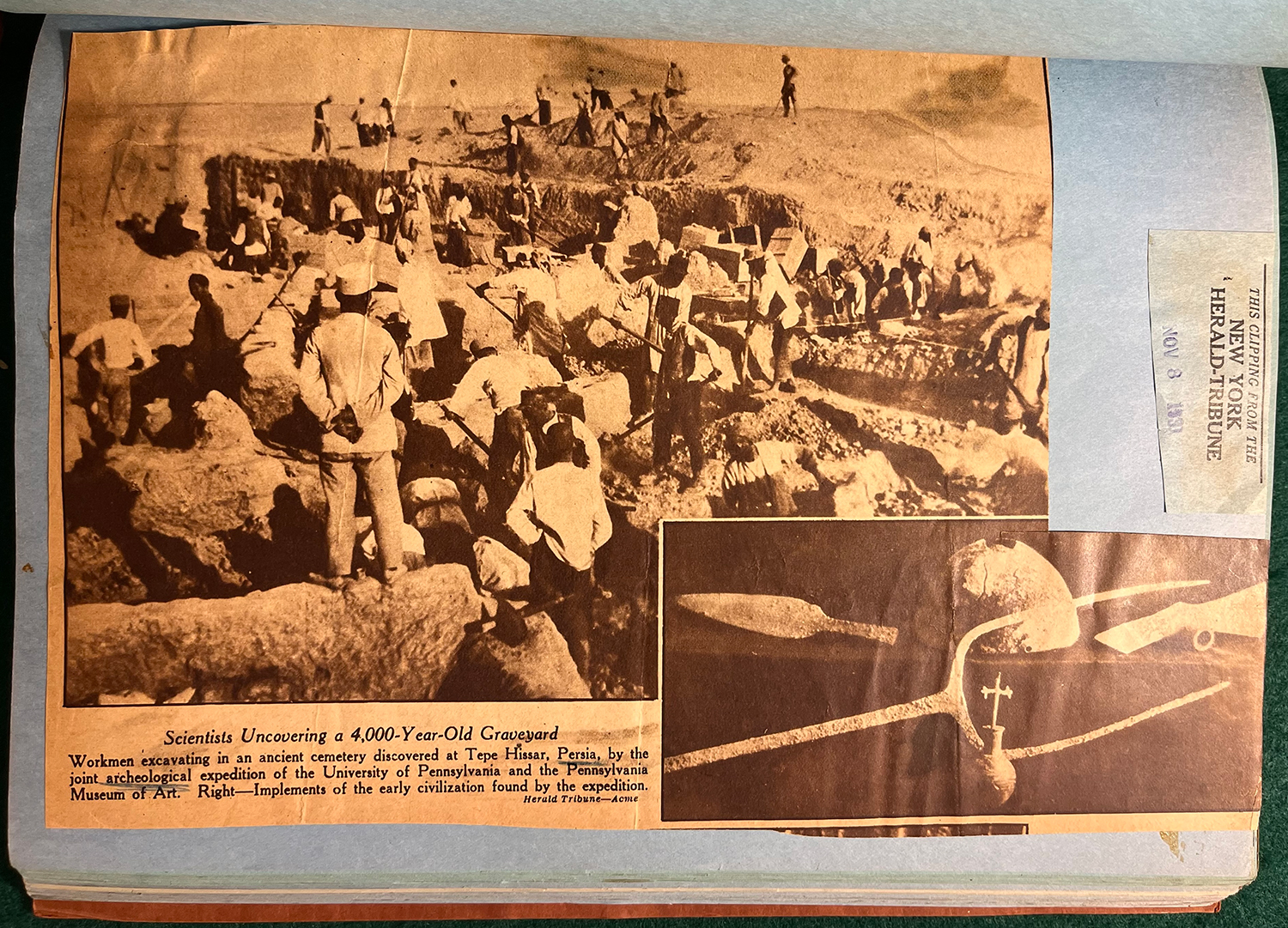

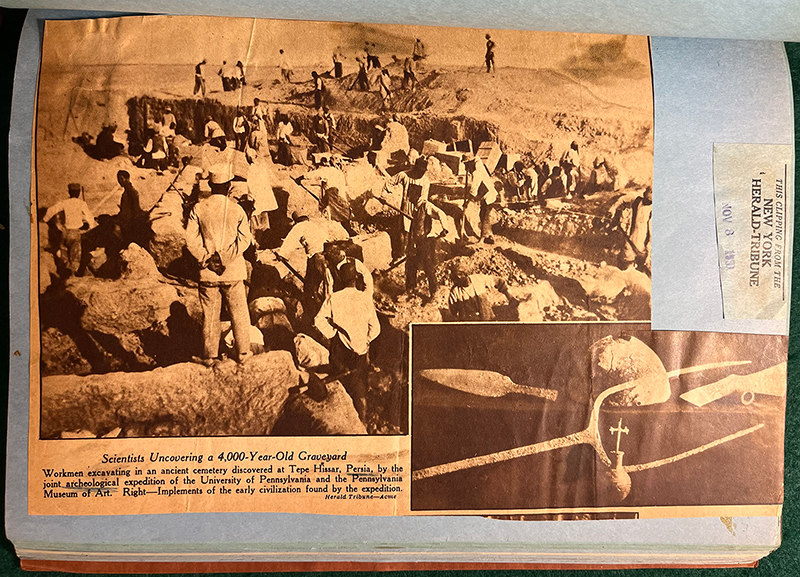

While the Penn Museum redisplays the mihrab, it also becomes involved in scientific archaeological excavation in Iran, which is now open to various parties given the cancellation of the French monopoly in 1927. The museum’s first excavation (begun in 1931) is at Tapeh Hesar in Damghan (map) and conducted in collaboration with Arthur Upham Pope’s American Institute for Persian Art and Archaeology and directed by German archaeologist Erich F. Schmidt (d. 1964) (fig. 128).163

May–June 1932: Philadelphia

About a year into its third known display in the Penn Museum, Kevorkian sends the museum two tiles that had been isolated from the mihrab for at least three decades and previously owned by French collector Octave Homberg (see 1903). Jayne responds, “I wish to acknowledge the receipt of the two tiles for the Mihrab which you handed Miss McHugh. As soon as our technician is free we shall have them properly incorporated in the monument. With my thanks to you for this added proof of your kindness to the Museum…”164 The tiles are soon reinstalled in the mihrab, marking a positive intervention and reunion, in contrast to the problematic pastiche of 1931 London. A photograph taken in 1940 shows the two tiles returned to the ensemble (fig. 129). While the larger tile is put in its proper place as the fourth tile in the outer border, the thinner tile is mispositioned in the inner border. Although it should be located near the end of the inscription on the lower left, it is installed on the upper right (see Conclusion).

1933: Varamin

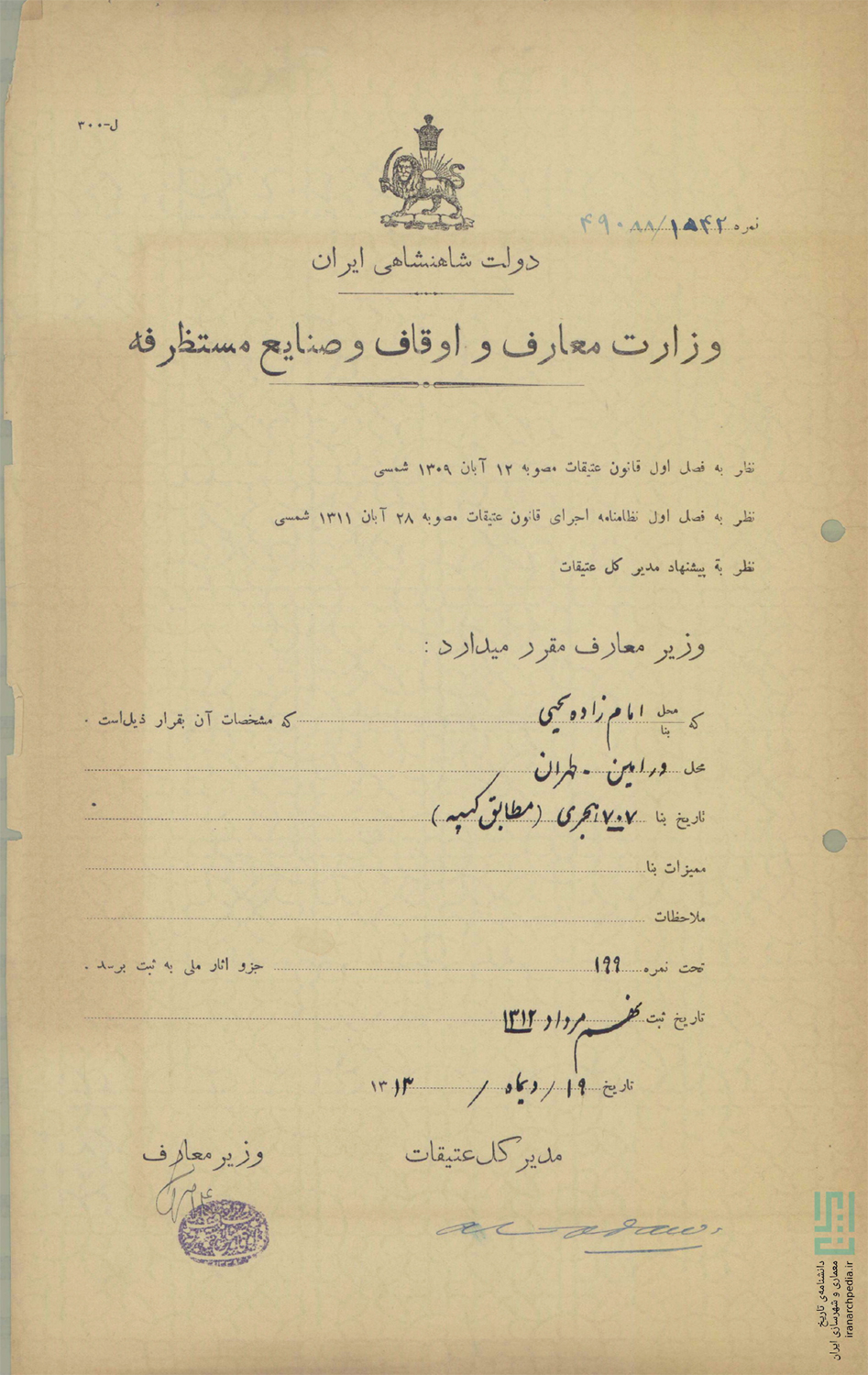

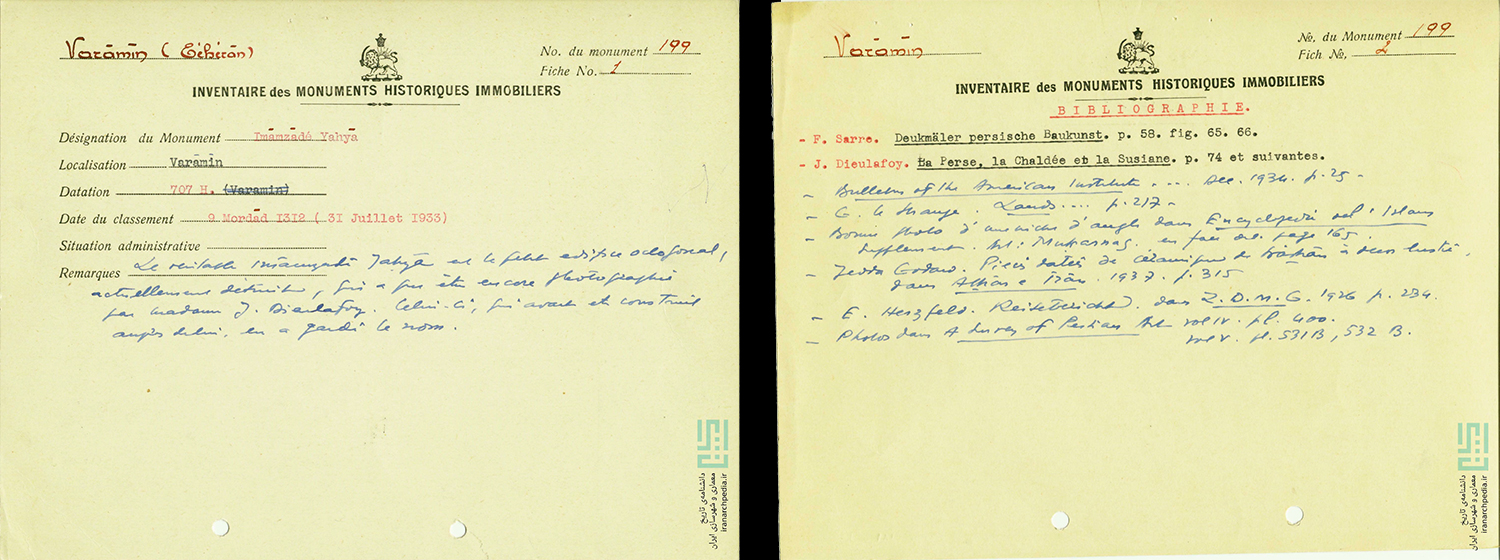

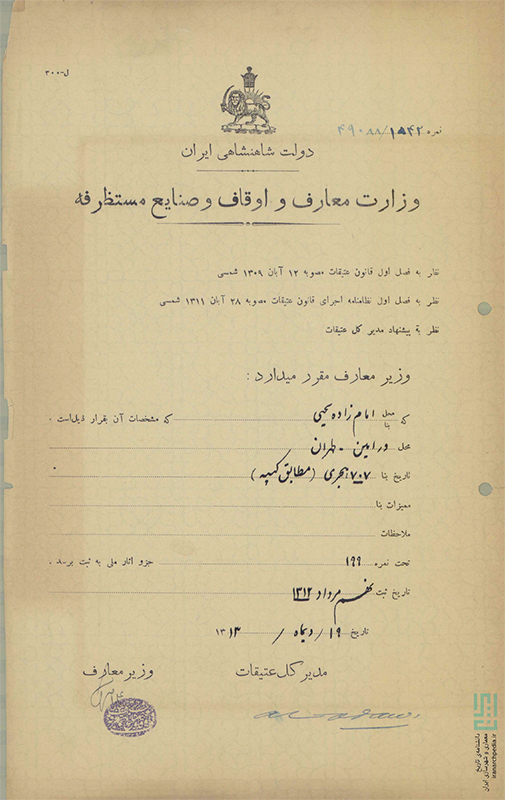

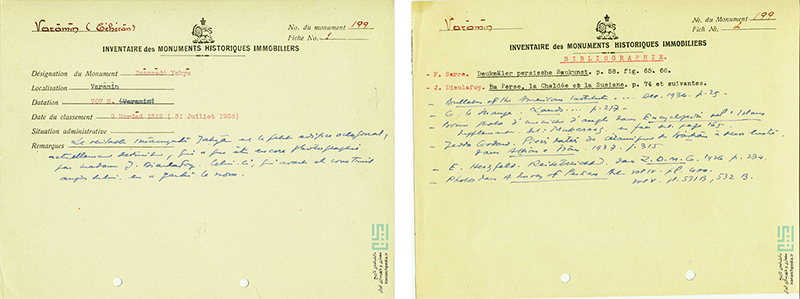

On 9 Mordad 1312 Sh/31 July 1933, the Emamzadeh Yahya is registered as a national heritage site and assigned the number 199. The registration of architectural monuments through the Zand era (1796) had been outlined in the Antiquities Law passed on 12 Aban 1309/9 November 1930. This law is referenced at the top of the shrine’s official declaration, which also notes that its registration was proposed by André Godard (d. 1965), the director of the Archaeological Services of Iran (مدیر کل عتیقات), and approved by Ali-Asghar Hekmat, Minister of Education (وزیر معارف) (fig. 130).

The Emamzadeh Yahya’s bilingual (Persian and French) inventory card records its name, location, date of construction (707 AH, from the stucco inscription), date of registration, and some remarks (fig. 131). The French card includes Godard’s handwritten notes, which presumably guided the Persian translation:

Le veritable Imāmzadé Yahyā est le petit édifice octogonal, actuellement détruit, qui a pu être encore photographié par Madame J. Dieulafoy. Celui-ci, qui avait été construit tout auprès, en a gardé le nom.

بنای اصلی امامزاده یحیی ساختمان هشتگوش کوچکی بوده که اکنون منهدم گردیده و خانم دیولافوا عکسی از آن گرفته است. بنای کنونی که نزدیک امامزاده یحیی اصلی احداث گشته بهمان نام نیز خوانده میشود.

The original Emamzadeh Yahya is the small octagonal building, now destroyed, which was photographed again by Madame J. Dieulafoy. This one, which had been built nearby, kept the name. [translated from the French]

Godard’s notes seem to rely exclusively on Jane Dieulafoy’s account from 1883 or 1887 and reveal the lasting impact of her textual and photographic documentation. He references her photograph of the complex showing the octagonal structure with a conical dome on the west (see fig. 27) and erroneously concludes that this structure, which was by then demolished, was the original emamzadeh. Had Godard engaged with local residents and the site itself, he would have been aware that the gonbadkhaneh was clearly the burial place of Yahya b. ʿAli. His failure to mention the theft of the tiles is also notable, given that Dieulafoy herself devoted considerable space to them and described some as “stolen.” Whether intentional or not, Godard’s statement that the original building was destroyed not only diminished the still standing medieval tomb and living shrine but might have helped to normalize and justify the preservation of its tiles in museums.

The back of the registration card includes a bibliography that reveals two key points (fig. 131, right). First, Godard’s understanding of the site was shaped primarily by published European sources, and he neglected to use any Persian sources, including Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh’s 1876 newspaper article. It is also unclear why he relied so heavily on Dieulafoy when he could have made his own conclusions based on his own visit, which appears to have transpired around this time and included his taking of several photographs inside the tomb (see Photo Timeline, no. 7–12). Second, Godard returned to this bibliography at a later date, updating it through the mihrab’s reproduction in A Survey of Persian Art of 1938–39. The same degree of revision was not afforded to his general remarks about the shrine, which later mislead others (jump ahead to 1996).

1935: Berlin

In his third publication of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab (see 1910 and 1928), Sarre contextualizes it in relation to three other so-called mihrabs created in Kashan. He identifies the “Imamzadeh Jahjâ,” corrects his earlier misreading of the mihrab’s date, and mentions its recent exhibition in London, belonging to Kevorkian, and location in the University Museum in Philadelphia. He also flags the problematic filler used in Philadelphia in 1918 and 1926: “Der Aufbau...ist nicht ganz richtig erfolgt. Ausserdem hat man in unschöner und unnötiger Weise die fehlenden Fliesen in der breiten Aussenborte rechts unten durch moderne ersetzt” (The construction...is not quite right. In addition, the missing tiles in the wide outer border at the bottom right have been replaced with modern ones in an unsightly and unnecessary manner).” Sarre reiterates the mihrab’s connection to the slightly earlier star and cross tiles described by “Madame Dieulafoy” and “jetzt in grosser Anzahl, ungefähr 100 Stück, ausserhalb des Landes in öffentlichen und privaten Sammlungen befinden” (now found in large numbers, approximately 100 pieces, in public and private collections outside the country). He describes the taking of the shrine’s tiles as a “Beraubung des Heiligtums” (robbery of the sanctuary) and suggests that this is why he was prohibited entrance in 1897.165

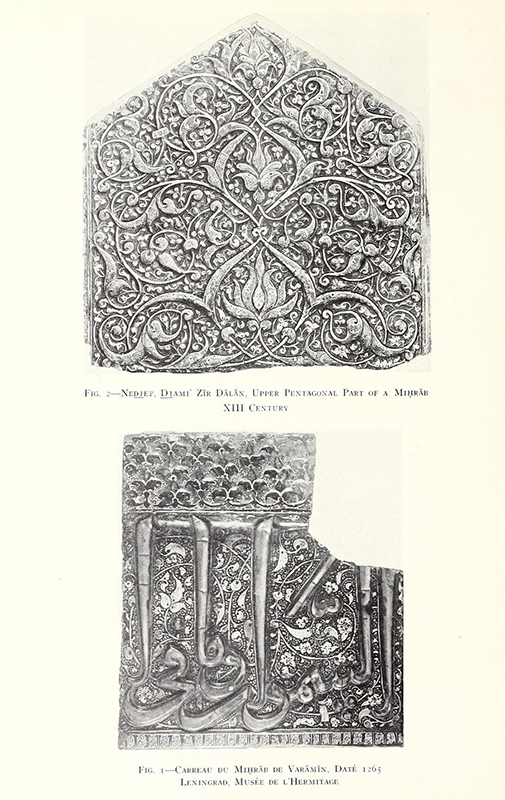

At the end of his article, Sarre turns to the panel naming “Imâm Yâhya” in the State Hermitage Museum and again erroneously calls it a “miḥrâb.” He focuses on its two signatures, highlights its lower quality in comparison to the other pieces discussed, and compares it to two other so-called mihrabs. It is unclear why Sarre called the tombstone panel a mihrab, especially when he knew about the tomb’s actual mihrab. The reproduction of the two elements side by side likely confused matters further, especially since the tombstone panel resembles the form of a mihrab when isolated and reproduced vertically (fig. 132). Nonetheless, this reproduction was an important first visual reunion of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab and cenotaph (or at least its tombstone panel).

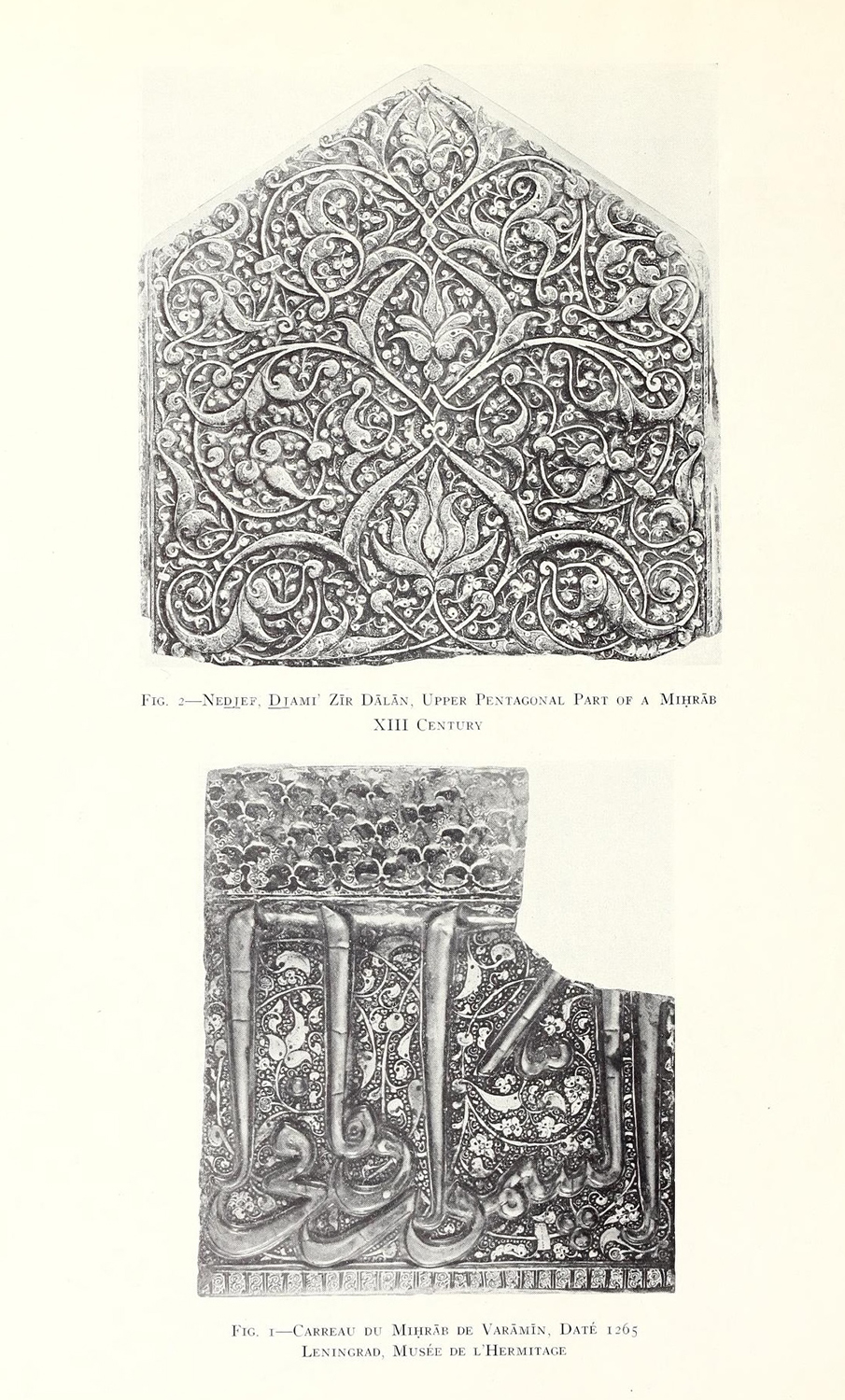

1935–36: Leningrad (St. Petersburg)

Russian scholar Vera Kratchkovskaya (d. 1974) publishes an article in Ars Islamica (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian) in which she identifies the single tile in the State Hermitage Museum as the third of the four tiles missing from the outer border of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab (fig. 133). She also identifies the tile previously in the possession of Octave Homberg (see 1903) as the fourth but is apparently unaware that this tile has been reunited with the ensemble in Philadelphia (see 1932). Kratchkovskaya’s article advocates for “le méthode épigraphique” (the epigraphic method) and emphasizes that scholars must move beyond tentative dating and attribution and seek to connect tiles dispersed across collections, thus getting closer to “le secret de leur origine” (the secret of their origin). She cites how the recent publication of a luster tile dated 707/1307 in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York allowed others from the same frieze to be identified.166

Kratchkovskaya’s article is preceded by two others on luster mihrabs: one by Dwight M. Donaldson on the two mihrabs in the tomb of Emam Reza at Mashhad (Checklist, no. 16) and one by Mehmet Aga-Oglu on the fragmented luster mihrab in a mosque in the Shrine of ʿAli at Najaf (see the hood in fig. 133). Donaldson reproduces a wide view of Emam Reza’s tomb showing its two mihrabs in situ, while Aga-Oglu attributes the Najaf mihrab to the workshop also responsible for “the Kevorkian miḥrāb in the University Museum, Philadelphia.”167 Considered together, the three Ars Islamica articles underscore a blossoming of scholarship on luster mihrabs in various guises—fragmented and relatively complete, in situ and in museums—and the centrality of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab in this research.

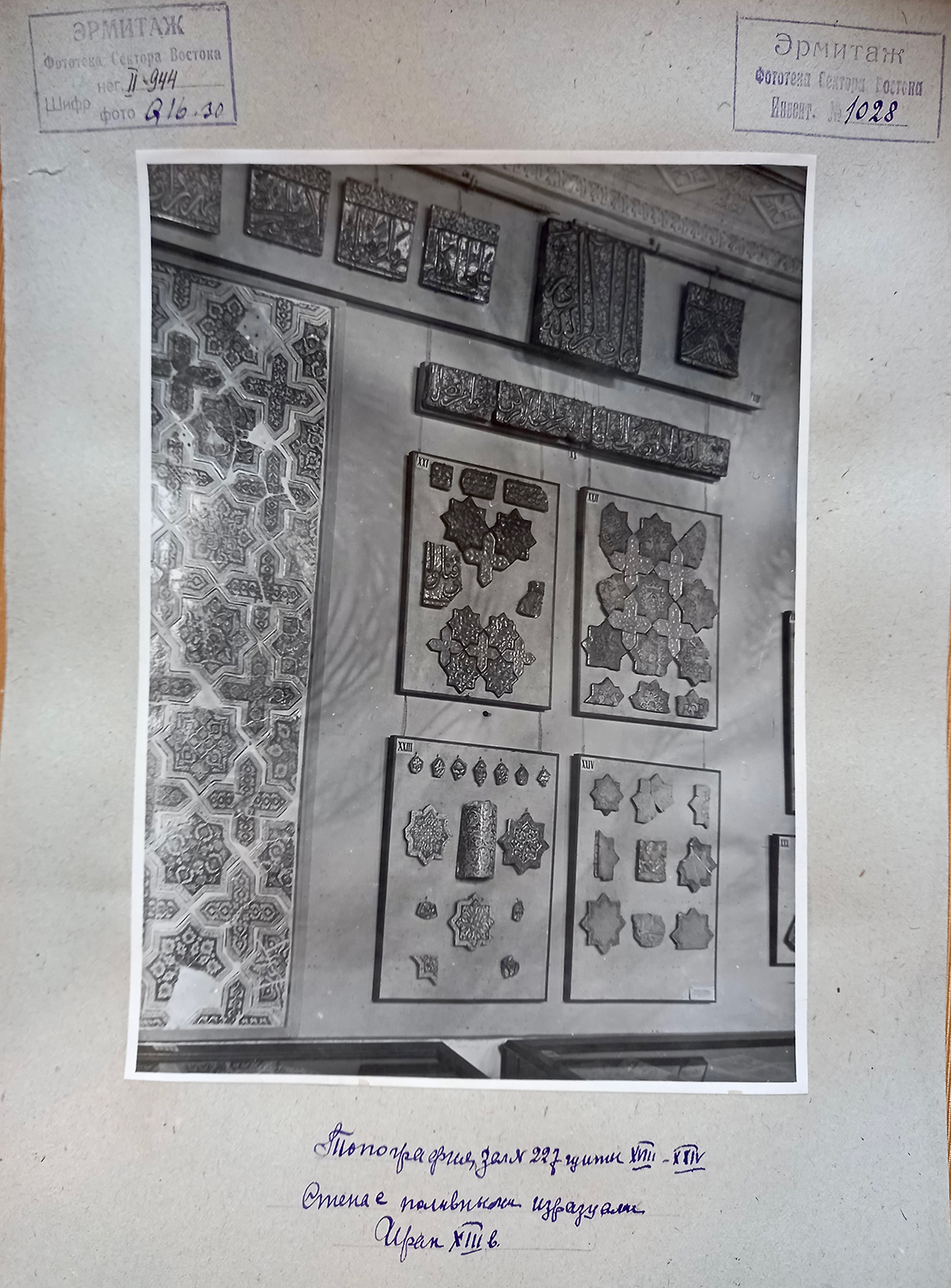

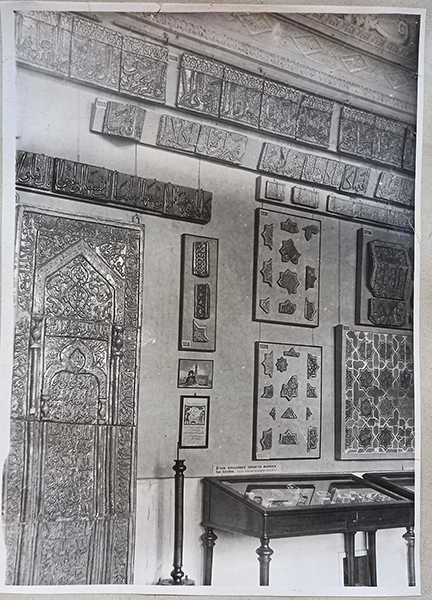

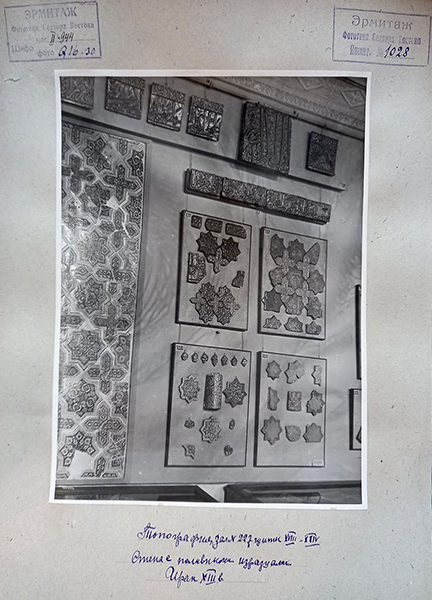

The Ars Islamica volume also announces the pending Third International Congress on Iranian Art and Archaeology Art in Leningrad, which followed the first in Philadelphia in 1926 and the second in London in 1931. The event is spearhead by Iosif (Joseph) A. Orbeli (d. 1961), the curator who received the transfer of over 950 luster tiles from the Stieglitz Museum in 1925. The eight-day congress (conference of academic presentations) is accompanied by an enormous exhibition at the State Hermitage Museum featuring 25,000 objects in eighty-four halls (fig. 134).168 Russian collections are highlighted, but loans are also secured from many countries, including around 900 objects from Iran.169 Scholars and dignitaries from around the world are invited to Leningrad, including Iranian archaeologist Mohammad Taghi Mostafavi (d. 1981) and Minister of Education Ali Asghar Hekmat (d. 1980). The exhibition is extremely popular and extended until 1 July 1936.170

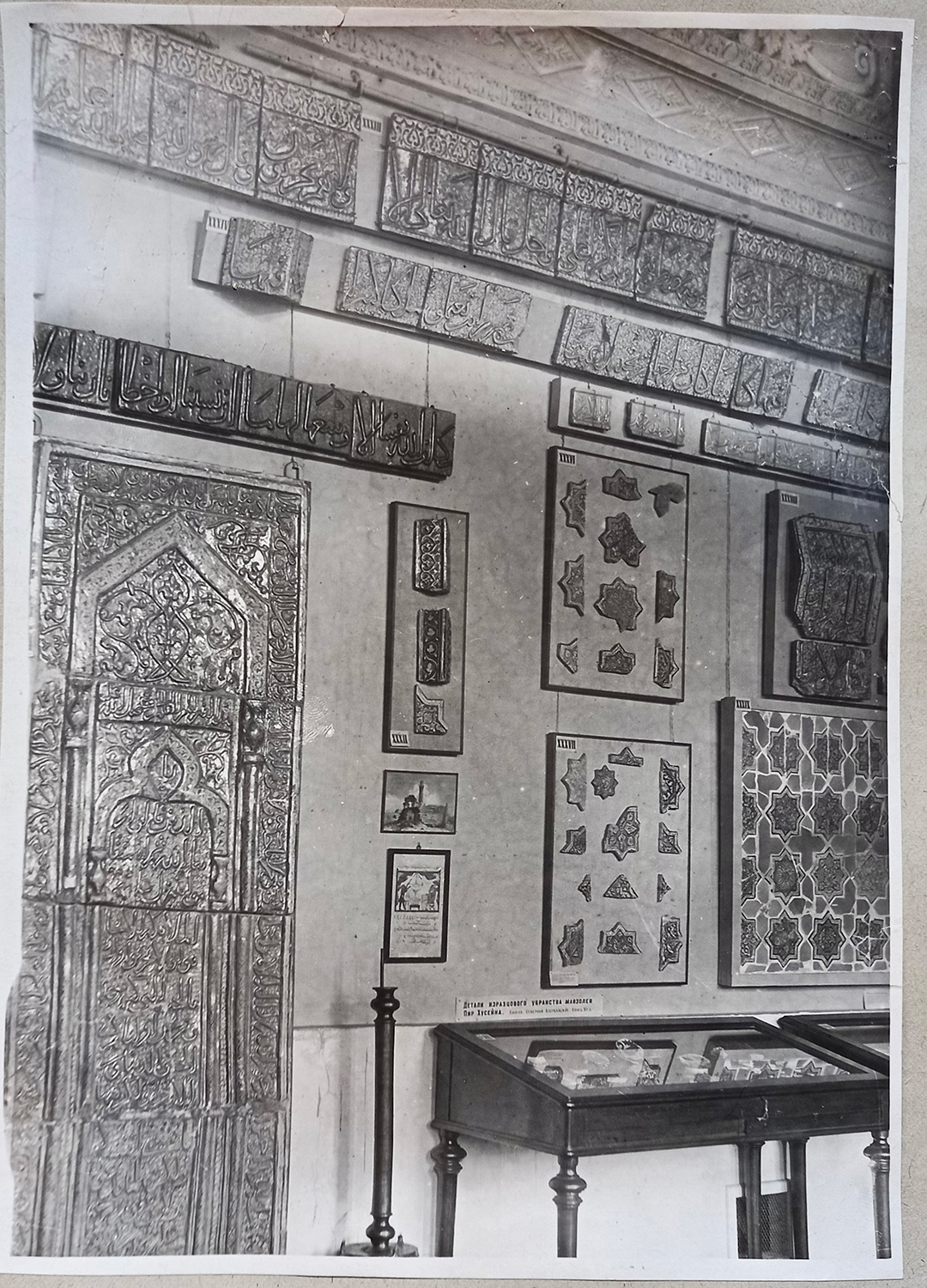

The exhibition at the Hermitage displays many luster tiles, including the tombstone panel attributed to Yahya b. ʿAli’s cenotaph, star and cross tiles from the tomb’s dado, and complete tiles and fragments from other sites such as the Shrine of Pir Hosayn in modern-day Azerbaijan (figs. 135–36). An image of this shrine is included in the display—next to the tombstone panel attributed to the Emamzadeh Yahya—and is a relatively rare visual acknowledgement of a source site (see fig. 135). Vera Kratchkovskaya presents on the Shrine of Pir Hosayn, and several others also give talks on luster ceramics, including German art historian Richard Ettinghausen (d. 1979) on the Kashan style and Iranian art historian Mehdi Bahrami (d. 1951) on luster tiles attributed to the Emamzadeh Jaʿfar in Damghan.

By 1935, the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab and related tiles were relatively well known in the international field of Persian art and architectural history. The shrine’s tiles were not only displayed in major cities like London, Philadelphia, and Leningrad but also published in English, French, and Russian. The mihrab was the focus of important and improving research that included conceptual reunions between its isolated tiles and the whole (recall Kratchkovskaya’s work) and even some literal reunions (recall Philadelphia 1932). In a few years, however, it would disappear from public and scholarly view. It is to the Territory of Hawaii, a world away from Varamin and a world away from the museums and conferences of London and Leningrad, that we now turn.

Notes

- Letter from Kevorkian to Freer, 25 August 1913, 2, FSA A.01, Box 19, Folder 28, NMAAA. For further discussion of this source, jump ahead to August 1913. ↩

- Letter from Kevorkian to Freer, 25 August 1913, 2–3, FSA A.01, Box 19, Folder 28, NMAAA. ↩

- Bakhash, “Nāṣer-al-molk, Abu’l-Qāsem.” ↩

- Ritter, “The Kashan Mihrab in Berlin,” 159. ↩

- These tiles are now in the Burrell Collection in Glasgow. See 33.54 and 33.55. ↩

- Luster tiles from Damghan are routinely attributed to its Emamzadeh Jaʿfar (map). ↩

- Letter from Kevorkian to Freer, 25 August 1913, 1–2, FSA A.01, Box 19, Folder 28, NMAAA. Searches to date in the National Archives and Diplomatic Archives of France have not located this “communique.” We also have not found any correspondence that supports Kevorkian’s claim that Mostowfi al-Mamalek was “disgraced” by the shah. However, Mostowfi al-Mamalek’s decision to stay in Paris and only to return to Iran in 1907, upon the shah’s death, may support Kevorkian’s narrative. ↩

- $77,061 in August 1913 converts to $2,521,809 in August 2025. We have converted French francs to British pounds (GBP) and U.S. dollars (USD) using the Historical Currency Converter, and we have computed U.S. dollar inflation from 1913 to 2025 using the CPI Inflation Calculator. ↩

- Letter from Kevorkian to Freer, 25 August 1913, 2, FSA A.01, Box 19, Folder 28, NMAAA. The mihrab’s “mortgage” may reflect Mostowfi al-Mamalek’s need for liquidity to cover extensive purchases in Paris. See September–November 1900, and specifically Amanollah Mirza Jahanbani’s letter to Dust-Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek on 28 Jamadi al-Awwal 1318/23 September 1900 (Moezzi and Khosronejad, Haz kardīm, 127–28). ↩

- This photograph has not been found in the archive, and it is unclear if it was indeed taken in Iran. Kevorkian might have been referring to the example reproduced in Sarre’s 1910 Denkmäler, the location of which is still unclear. Letter from Kevorkian to Freer, 25 August 1913, 3, FSA A.01, Box 19, Folder 28, NMAAA. ↩

- One of the four missing border tiles—the second in the series—remains unidentified (jump ahead to 2025). ↩

- We know that Homberg owned the fourth tile in the series, which he reproduced at least three times and which was reintegrated into the ensemble in 1932. If Homberg indeed owned a second tile from the border, it could be the first in the series, which eventually entered the Denver Art Museum (jump ahead to 1958), or the second, which is still missing. We can rule out the third tile in the series, since it was sold to the Stieglitz Museum in 1901 and then entered the Hermitage. The sale of Homberg’s collection in Paris in 1908 might provide some clues, but unfortunately, none of the possibilities are illustrated, and none of the given dimensions match the missing tile (~H. 46, W. 42 cm). See Galerie Georges Petit, Catalogue des Objets d’Art, 11–16 May 1908, lot 189, 30. A “Duveen Brothers, Paris Library” copy of this catalog in the Clark Art Institute includes annotations noting the buyer and sale price in French francs. ↩

- Letter from Kevorkian to Freer, 25 August 1913, 4, FSA A.01, Box 19, Folder 28, NMAAA. These figures convert to $2,545,731 and $3,182,164, respectively. ↩

- Letter from Kevorkian to Freer, 25 August 1913, 5, FSA A.01, Box 19, Folder 28, NMAAA. ↩

- Letter from Freer to Kevorkian, 19 September 1913, 1–2, FSA A.01, Box 19, Folder 28, NMAAA. ↩

- Letter from Kevorkian to Freer, 20 October 1913, 2, FSA A.01, Box 19, Folder 28, NMAAA. The final page of this letter mentions the excavations at Rhages (Rey) and the “royal prince” (see 1912). ↩

- Letter from Freer to Kevorkian, 23 October 1913, FSA A.01, Box 19, Folder 28, NMAAA. One Mr. Hallouneuff (?) of Persian Art Galleries follows up with good wishes for Freer’s health. ↩

- Letter from Kevorkian to Freer, 23 January 1914, FSA A.01, Box 19, Folder 28, NMAAA. This handwritten letter was transcribed by one H. Paliuer (?) of Persian Art Galleries. ↩

- The so-called temple in question remains unclear but was perhaps related to Kevorkian’s earlier digging “on the site of a ruined temple” at Raghes (Rey). See “To Display Rare Ceramics,” The New York Times, 2, 27 February 1910. ↩

- Letter from Freer to Kevorkian, 9 February 1914 and letter from Kevorkian to Freer, 12 February 1914, FSA A.01, Box 19, Folder 28, NMAAA. This is the final known correspondence about the mihrab in this archive. ↩

- The Freer Gallery of Art opened on 9 May 1923. In 2019, this museum, as well as the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, were collectively rebranded as the National Museum of Asian Art. ↩

- For an analysis and reconstruction of Pir Hosayn’s cenotaph, see Sadofeev, “Questions of Attribution of Some Tiles.” ↩

- New research is pending on Yahya b. ʿAli’s cenotaph. Dmitry Sadofeev (curator of medieval Iranian ceramics and tiles at the Hermitage) has been working on a reconstruction, based primarily on tiles in the museum, and has prepared an article for publication. Thank you to Daria Vasilyeva (curator at the Hermitage) for information on the 1923 exhibition at the Stieglitz Museum. ↩

- The Galleries of Charles of London, Exhibition of the Kevorkian Collection, no. 335 [pages unnumbered]. It seems likely that this text was written by, or at least supervised by, Kevorkian. ↩

- This telegram has not been located in the Penn Museum Archives (PMA), but it is mentioned in a 6 May 1914 letter from Gordon to Kevorkian in which the former asks for the price of the mihrab. The institution currently known as the Penn Museum is formally the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. In archival sources and earlier publications, it is sometimes referred to as the ‘University Museum.’ In this essay, we use ‘Penn Museum’ for consistency, except when quoting directly from historical documents, in which case we retain the original wording. The finding aid for the relevant collection (George B. Gordon Director’s Office Records) is available here. We thank Lindsay Allen for alerting us to materials about the mihrab in this archive and Alex Pezzati for his support and expertise. ↩

- ‘Steamer’ refers to a steam-powered ship commonly used in the late nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries for transporting goods and passengers across long distances. ↩

- This connection is confirmed by the “memorandum bill” cited below, dated 29 March 1918, and noting the West End Wigmore Street location. ↩

- Letter from Kevorkian to Gordon, 3 July 1916, George Byron Gordon Director’s Office Records, 0001.03, Box 12, PMA. ↩

- Letter from Kevorkian to Gordon, 4 February 1918, 2, George Byron Gordon Director’s Office Records, 0001.03, Box 12, PMA. ↩

- Letter from Kevorkian to Gordon, 9 February 1918, 2, George Byron Gordon Director’s Office Records, 0001.03, Box 12, PMA. ↩

- Letters from Kevorkian to Gordon, 4 February 1918 and 18 March 1918, George Byron Gordon Director’s Office Records, 0001.03, Box 12, PMA. ↩

- Letters from Kevorkian to Gordon, 18 February 1918 (name of the installation firm), 28 February 1918 (time needed for installation), and 14 March 1918 (fragility and transport by truck). George Byron Gordon Director’s Office Records, 0001.03, Box 12, PMA. ↩

- The annotated photograph has not been located in the archive. ↩

- This is inaccurate. For the eleven known surviving luster mihrabs, see note 1. ↩

- Bahr al-Olumi, Kārnāmeh-ye anjoman-e āthār-e mellī, 19. See also Grigor, “Recultivating ‘Good Taste,’” 17. ↩

- Bahr al-Olumi, Kārnāmeh-ye anjoman-e āthār-e mellī, 19. ↩

- Herzfeld, “Reisebericht,” 234. ↩

- Letter from Gordon to Kevorkian, 30 June 1925, George Byron Gordon Director’s Office Records, 0001.03, Box 12, PMA. ↩

- Letter from Gordon to Kevorkian, 6 July 1925, George Byron Gordon Director’s Office Records, 0001.03, Box 12, PMA. ↩

- Letter from Kevorkian to Gordon, 1 April 1926, George Byron Gordon Director’s Office Records, 0001.03, Box 12, PMA. ↩

- Letter from Kevorkian to Gordon, 27 April 1926, George Byron Gordon Director’s Office Records, 0001.03, Box 12, PMA. ↩

- A comparable candlestick (NEP12) was purchased from Kevorkian in 1925. A number of doors were purchased from the dealer in 1919, 1922, and 1926, some with figural designs and one from the ‘Emamzadeh Qasem’ (NEP41) (see 1912). ↩

- On this pavilion, see Wood, “‘A Great Symphony of Pure Form,’” figs. 4–5. For additional images of the exposition, see Temple University Libraries. ↩

- “Payments to H. Kevorkian,” undated but before 13 March 1926 (this is the last entry in the document), PMA. For materials from Iran purchased from Kevorkian between 1915 and 1926, use the ‘advanced search’ in the collections online. ↩

- “Objects in the museum which are the property of Mr. H. Kevorkian,” 17 February 1927, appended to a letter from the Secretary of the Board of Managers, Penn Museum, to Kevorkian, PMA. ↩

- Ritter, “The Kashan Mihrab in Berlin,” 164. Sarre had been in contact with John Richard Preece from 1912 onwards. This figure is equivalent to approximately $627,989 in August 2025. ↩

- Sarre, “Zwei Persische Gebetnischen aus Lüstrierten Fliesen,” 126. ↩

- Letter from Smith to Jayne, 3 December 1930, Horace H.F. Jayne Director's Office Records, 0001.04, Box 9, PMA. ↩

- Letter from Smith to Jayne, 11 December 1930, Horace H.F. Jayne Director's Office Records, 0001.04, Box 9, PMA. ↩

- Two of these tiles are now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. See 40.181.5 and 40.181.6. ↩

- For some discussions of this exhibition, see Wood, “‘A Great Symphony of Pure Form’” and Rizvi, “Art History and the Nation.” For the list of lenders, see Catalogue of the International Exhibition of Persian Art, 341–46. ↩

- Kühnel notes that Sarre’s incorrect reading of the date as 661 in 1910 fueled the idea that the lower part of the mihrab belonged to a different mihrab. See Kühnel, “Dated Persian Lustred Pottery,” 235n11. ↩

- In 1918, following several attacks on the Emamzadeh ʿAli b. Jaʿfar, religious authorities removed all remaining tiles from the interior and transferred them to the treasury of the Shrine of Fatemeh Massumeh. See Feyz, Ganjīneh-ye āthār-e Qom, vol. 2, 337–38. Although tiles from this mihrab are not recorded in the London catalogue, in a 1937 article, Yedda Godard notes that the final tile of the mihrab’s outer border—bearing the date and signature—was sent to London in 1931. See Godard, “Pieces datées de céramique de Kā͟s͟hān,” 312. ↩

- Acts of pastiching together historical fragments to create the illusion of completeness are more common in portable ceramics, including luster and mina’i. See, for example, Leoni et al., “‘The illusion of an authentic experience.’” ↩

- Kühnel, “Dated Persian Lustred Pottery,” 235n11. ↩

- A similar misorientation persists in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s display of the spandrels from the mihrab of the tomb of ʿAbd al-Samad in Natanz. See Leone, “New Data on the Luster Tiles,” fig. 16–18. ↩

- By the late nineteenth century, certain restrictions existed for access into the Emamzadeh Yahya, but they were mainly based on religion, not social rank. ↩

- Letters from Kevorkian to Jayne, 13 May 1931 (broken tiles) and 8 May 1931 (display preferences). Horace H.F. Jayne Director's Office Records, 0001.04, Box 9, PMA. ↩

- Kühnel, “Dated Persian Lustred Pottery,” 235. ↩

- [no author], “The University Museum Excavations in Iran.” ↩

- Letter from Jayne to Kevorkian, 9 June 1932. Horace H. F. Jayne Director’s Office Records, 0001.04, Box 9, PMA. ↩

- Sarre, “Eine keramische Werkstatt von Kaschan,” 65–66 (all references in this paragraph). ↩

- Kratchkowskaya, “Fragments du Miḥrāb de Varāmīn,” 132–33. The tile in question is from the epigraphic frieze in the tomb of Shaykh ʿAbd al-Samad at Natanz (Metropolitan, 12.44). ↩

- Donaldson, “Significant Miḥrābs in the Ḥaram at Mashhad,” figs. 1–2; Aga-Oglu, “Fragments of a Thirteenth Century Miḥrāb,” 131. ↩

- See Ackerman, “L’exposition d’art iranien a Leningrad,” 45; Vasilyeva, “Eighty Years after the Third International Congress,” 155; and Kadoi, “The Study of Persian Art on the Eve of World War II,” 155. ↩

- Vasilyeva, “Eighty Years after the Third International Congress,” 155. Vasilyeva records that thirty-four loans were gifted to the Hermitage at the end of the exhibition. ↩

- Vasilyeva, “Eighty Years after the Third International Congress,” 159–60. Ibid., 169, describes the exhibition as “underpinning the permanent display of the art and culture of the Orient” and “perhaps the most significant exhibition ever undertaken by the department, determining for many years the underlying principles according to which its displays were created.” The exhibition’s eighty-year anniversary was commemorated in September 2015 with a temporary exhibition in the Hermitage Theatre. See ibid., fig. 21a–c. ↩