From Varamin to Honolulu: The Displacement, Commodification, and Aestheticization of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s Luster Mihrab, 1863–2025

Keelan Overton and Hossein Nakhaei

Contents:

Conclusion

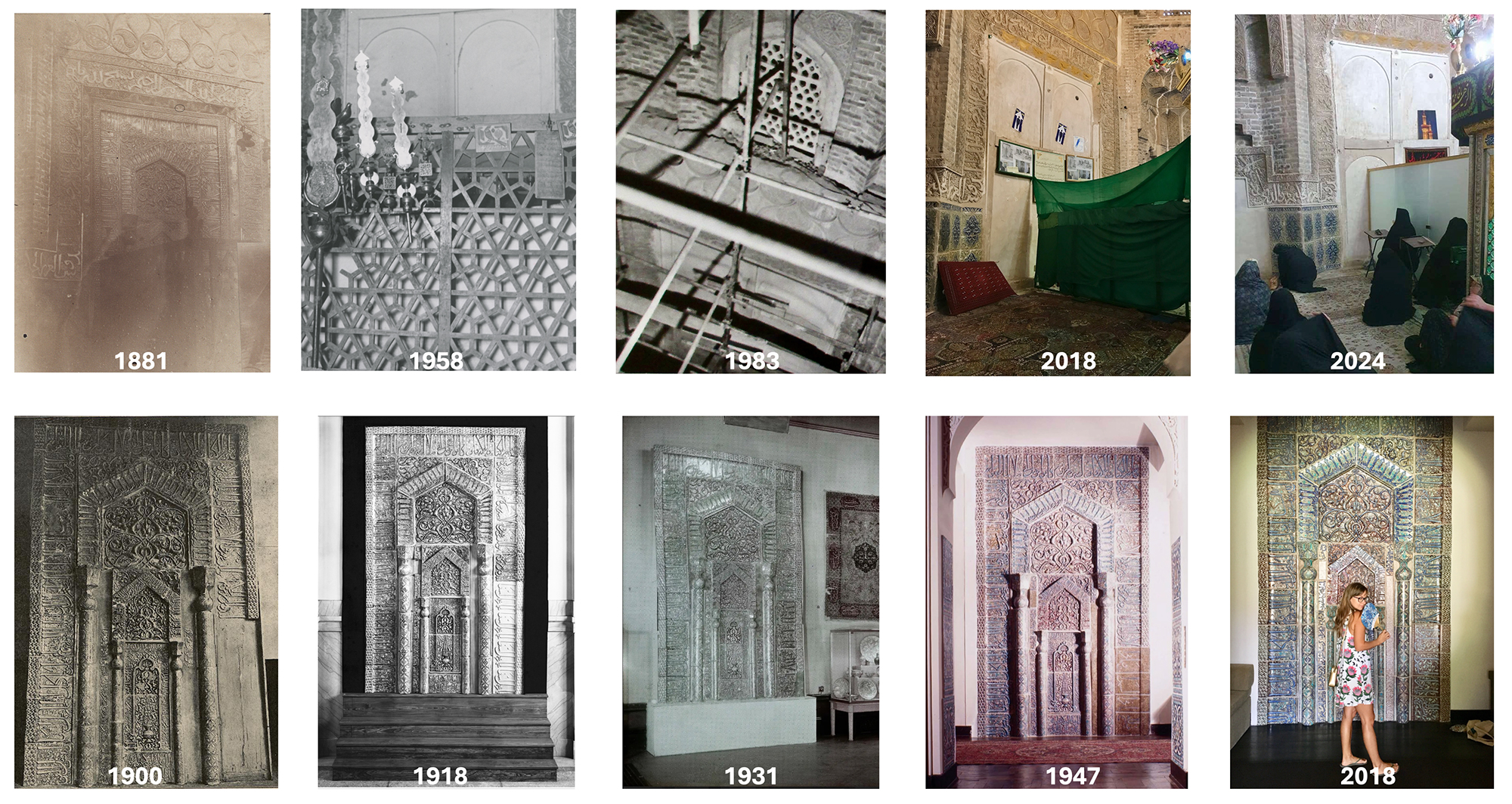

This historiography has traced the profound physical and conceptual transformations of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab between 1863 and 2025. For over six hundred years, the mihrab was embedded in the tomb of Yahya b. ʿAli, where it oriented prayer and sanctified the space through its sacred verses, dynamic luster surfaces, and monumentality. During the nineteenth century, it was studied in situ by a variety of admirers, and its exposure and fame steadily grew. The majority of the ensemble was taken to Paris in 1900, and after being exhibited in a boutique to popular acclaim, it entered a period of obscurity, stored in the city for nearly a decade (1900–12). It was then sold to a dealer, and for the next twenty-eight years (1912–40), it was exhibited, commodified, and peddled on the international art market as a standalone ‘monument’ ultimately valued at $150,000. For the next fifty-three years (1940–93), it was a private possession in a secluded home, literally on the opposite side of the world from Varamin, in an entirely foreign setting. When this home transformed into a museum (2002), the mihrab was reintroduced to the public as a museumized ‘object’ and ‘masterpiece.’ Meanwhile, the resilient tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya adapted to the thefts of its tilework and the shrine’s major reconfiguration. The mihrab remained conceptually present and resonant, and its void continued to orient prayer while also serving as a flexible space for its community’s curated expressions (fig. 274).

These broad trajectories underscore the mihrab’s geographic reach (Varamin, Paris, London, New York, Philadelphia, Honolulu) and conceptual mutability (architectural element, orientation device, sacred text, cultural heritage, financial commodity, collectible object, private possession, museum masterpiece), depending on the eye of the beholder and/or possessor. Along the way, the ensemble has been praised and memorialized while simultaneously damaged and misunderstood. The mihrab’s layered journeys reveal how sacred objects are not simply displaced in space but continuously remade—physically, semantically, and ideologically—by the structures of power, privilege, and desire that shape their life following their removal.

Historical Summary

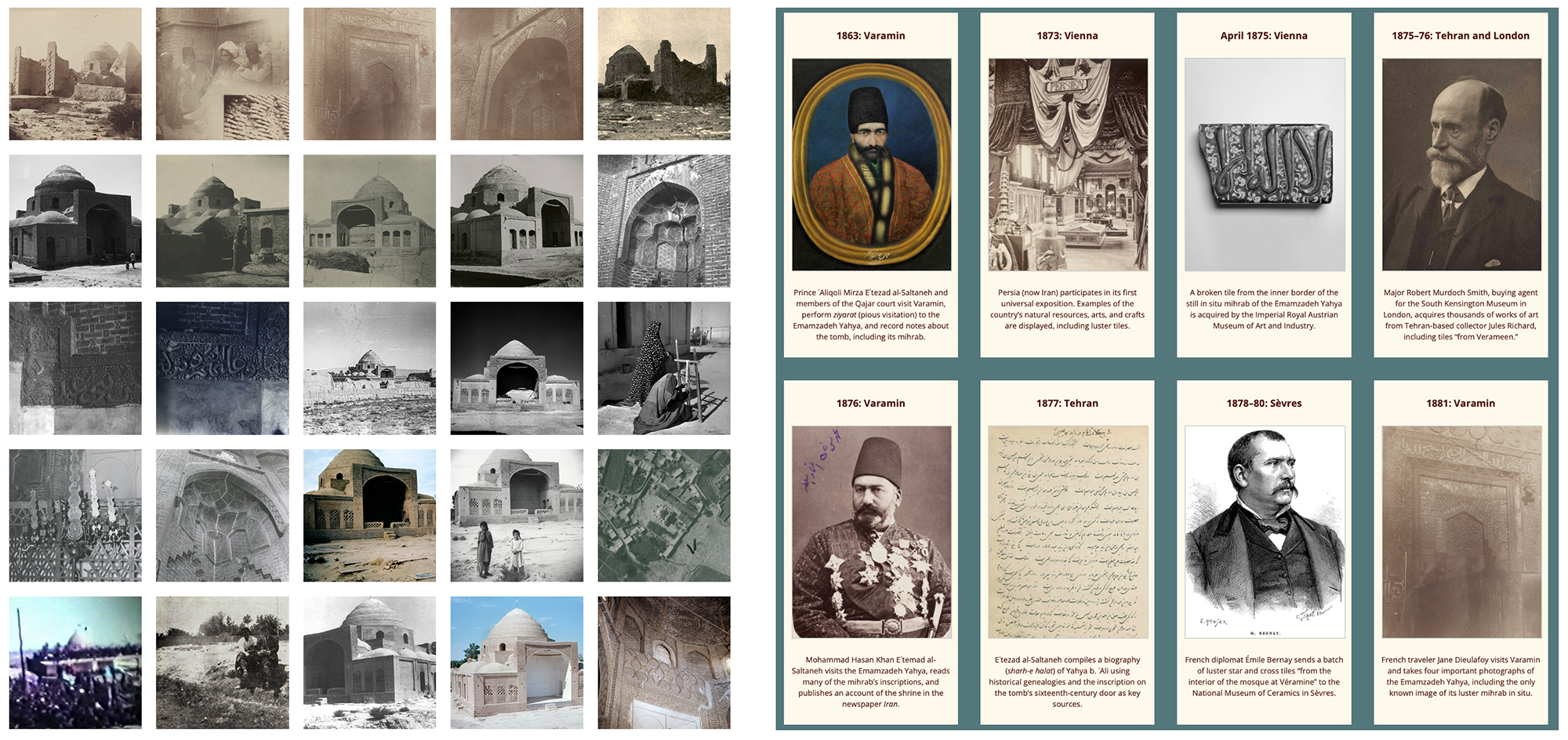

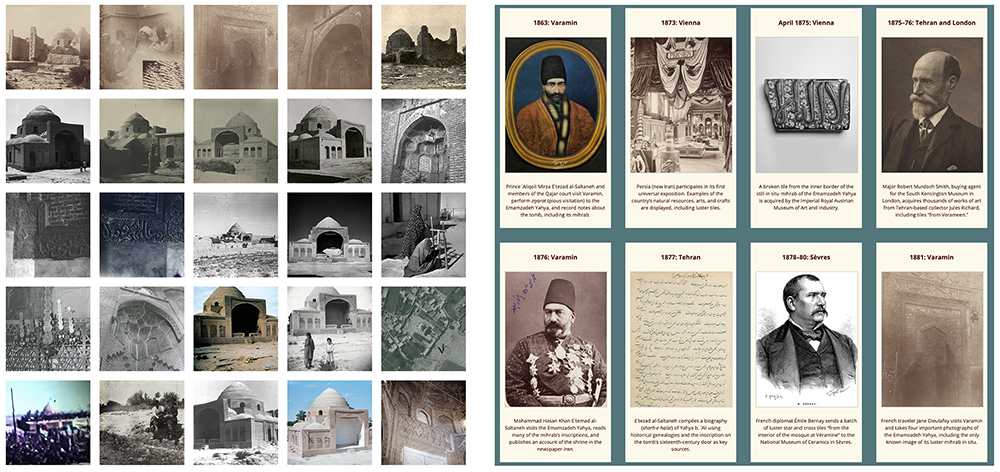

During the second half of the nineteenth century, the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab entered a prolonged process of documentation and displacement shaped jointly by Qajar officials and European individuals and institutions. The Qajar court visits memorialized in the accounts of Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh (1863) and Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh (1876) attest to the shrine’s status as a living sacred space and destination of ziyarat. Even during this time, however, individual tiles from the mihrab were already being detached, circulated, and sold into European collections, catalyzed by the growing momentum of international exhibitions in cities like Vienna and Paris (1873, 1889).

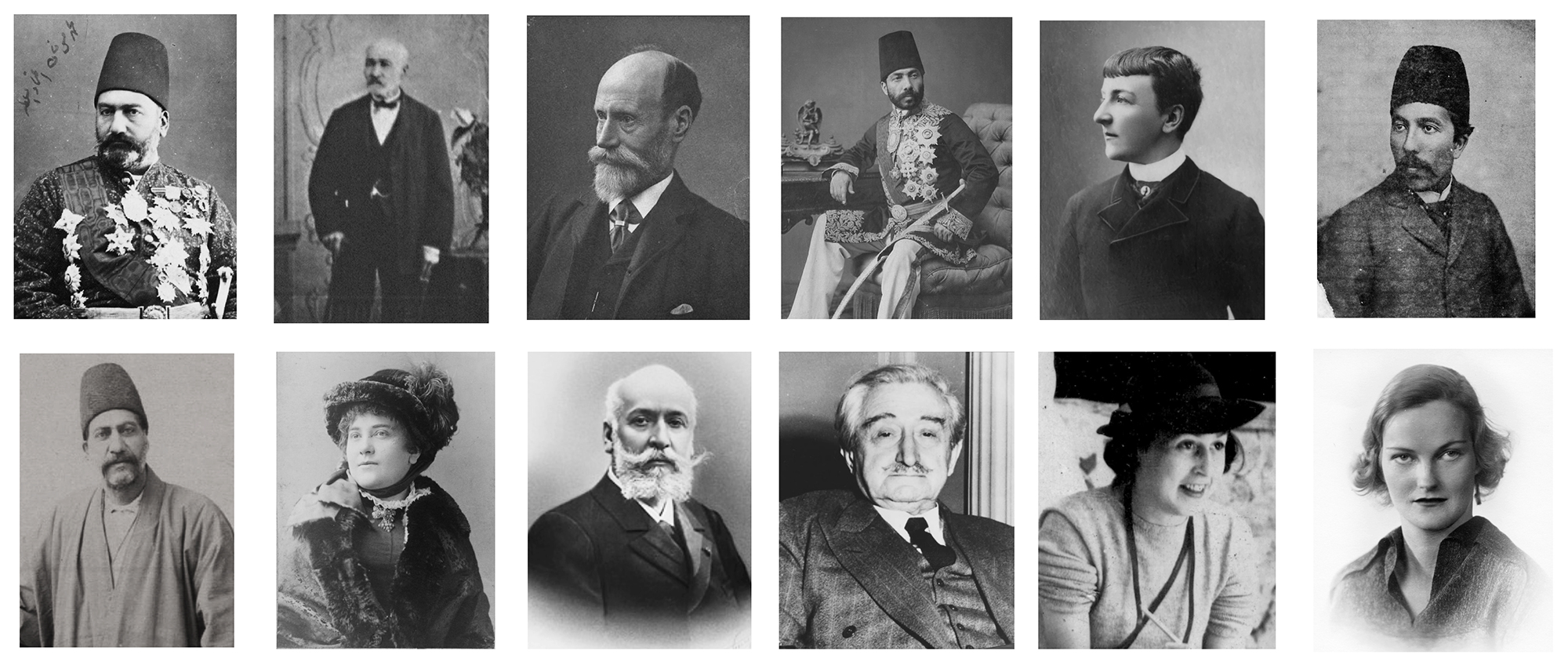

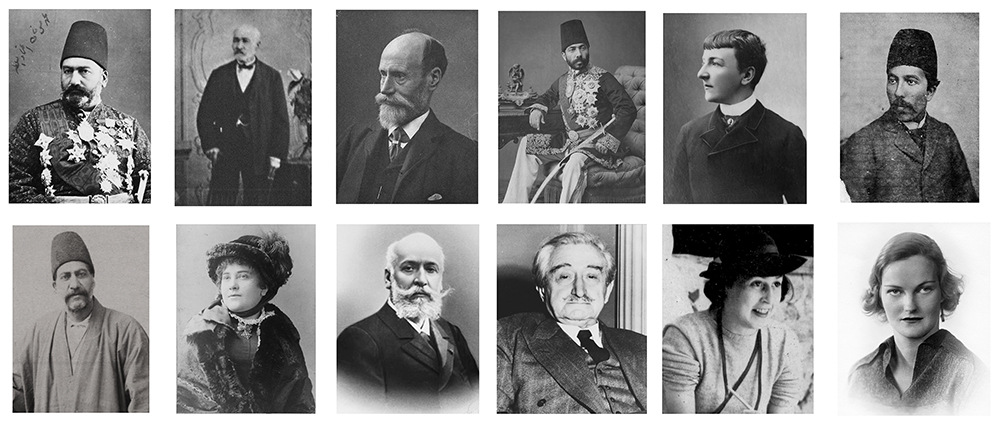

Money, connection, and access were the three key currencies required to acquire these tiles, and European ceramic and design museums—Sèvres, South Kensington, k. k. Österreichisches Museum für Kunst und Industrie—played a role in driving the ‘hunt.’ Museum agents like Robert Murdoch Smith navigated access through pre-existing appointments in Iran and personal ties to high-ranking officials like Mirza Hossein Khan Moshir al-Dowleh Sepahsalar; dealer-collectors like Jules Richard leveraged embedded positions within the Qajar court and European connections; and some Qajar elites used cultural patrimony as personal capital and prestige on the international stage.

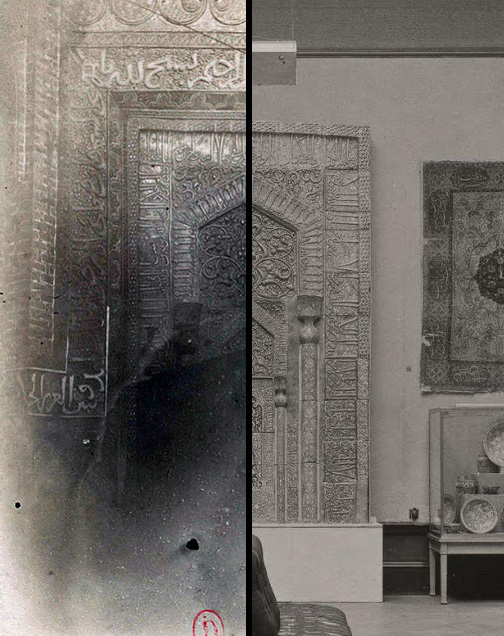

Access to sites that preserved luster tilework was so pivotal that a single visit could determine a site’s future. Jane Dieulafoy’s brief visit to the Emamzadeh Yahya in June 1881, which was facilitated by a permission issued by Naser al-Din Shah, generated two publications (1883, 1887) that in turn played a transformative role in introducing the mihrab to collecting networks. By exposing what had long remained beyond the gaze of foreigners, her account became a foundational reference for generations of dealers, collectors, and scholars and propelled the mihrab’s shift, in some circles, from a sacred architectural element to an object of aesthetic desire.

A closer examination of the mihrab’s trajectory reveals that the familiar binary of ‘European thieves’ versus ‘Iranian victims’ oversimplifies the complex reality of its displacement. While it is currently unknown who exactly ordered the mihrab’s removal from the tomb, and when, Qajar elites participated in its transport to Paris in 1900 and subsequent commodification. This entangled web of agency and complicity challenges conventional frameworks of blame and invites a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of cultural loss—one that accounts for those who ignited, facilitated, and profited from the displacement (fig. 275). While figures such as Robert Murdoch Smith and Jules Richard are familiar names in the dispossession of Iran’s cultural heritage, those like Mirza Hossein Khan Ashtiani Qavam Daftar and Mirza Hasan Khan Ashtiani Mostowfi al-Mamalek are perhaps surprising. For audiences accustomed to viewing such figures through sanitized biographical lenses, it may be unsettling to confront their participation—whether direct or indirect—in the removal, sale, and circulation of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab and other examples of Iranian cultural heritage. Nevertheless, it is critical to parse these entanglements between political authority and personal ambition.

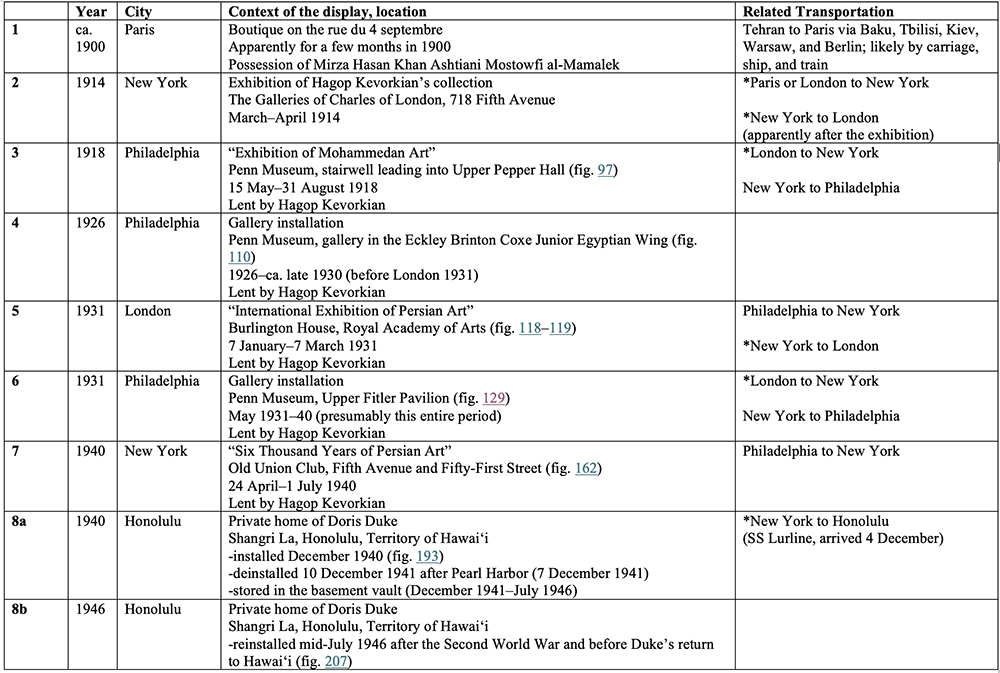

Chaotic circumstances in Iran during the last decades of the Qajar dynasty (1786–1925) created a vulnerable climate for cultural heritage. While Iranian officials and European elites profited off cultural patrimony, dealers initiated commercial digs throughout the country, especially on the Tehran plain around Rey and Varamin. One such dealer was Hagop Kevorkian, who purchased the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab from Mostowfi al-Mamalek in 1912–13. The sale of the mihrab to a dealer launched the ensemble into a new phase of possession, one that prioritized its constant display and publication to increase its financial value and opportunities for sale. Under Kevorkian’s purview, the mihrab was displayed six times in twenty-six years in three cities (Table I).

Table I. Displays of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab between 1900 and 1946 [pdf]

*indicates shipment by sea, across the Atlantic or Pacific Ocean

Kevorkian’s purveying of the mihrab can be considered through three frames: negative, positive, and pseudo positive. The mihrab’s six displays in his possession exposed it to considerable risk. Each instance of transport, installation, and deinstallation subjected it to damage and jumbling, and this indeed occurred during its return from London in 1931 (fig. 276). Moreover, the mounting system that Kevorkian likely developed for the mihrab resulted in irreparable damage to its tiles—the holes in the upper edges for attachment to the wood backing. While Kevorkian’s ultimate agenda was to maximize his profit, he fortunately decided to keep the mihrab intact as a ‘complete’ ensemble and even returned two displaced tiles to it in 1932. Many other large-scale luster ensembles were broken apart and sold as isolated tiles, including the cenotaph of Yahya b. ʿAli, which remains to be reconceptualized and understood. The same tragic fate befell many illustrated manuscripts, including the Ilkhanid Shahnameh (‘Great Mongol Shahnameh’), which was ripped apart by George Demotte (d. 1923) and dispersed worldwide. Demotte acquired it in Paris in 1910 from Shemavan Malayan, brother-in-law of Kevorkian, who apparently brought it from Iran.

In the pseudo positive category, Kevorkian seems to have prioritized a museum buyer for the mihrab, a motivation that was again to his benefit, including name recognition. Immediately after acquiring the mihrab, he approached Charles Lang Freer, who had endowed his collection to a future museum in the Smithsonian. He then cultivated a long relationship with the Penn Museum, giving the institution plenty of chances to buy the mihrab, and finally entered into negotiations with the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Neither the Penn Museum nor the Metropolitan were able to offer a suitable figure. When billionaire Doris Duke was able to pay Kevorkian’s asking price of $150,000, probably with little hassle or hesitation, he completed the sale, knowing that the mihrab’s transfer to her Honolulu home would relegate it to seclusion and isolation.

The mihrab’s acquisition by Doris Duke in late December 1940 saw its fate shift dramatically. During the forty years prior, it was displayed in four cities (Paris, London, New York, and Philadelphia) and published in some seminal art historical studies, including Sarre’s Denkmäler, A Survey of Persian Art, and the proceedings of the Third International Congress. Although it remained displaced from the shrine and Iran, it could at least be appreciated by those who could afford to go to museums and exhibitions in America and Europe, and its importance was even acknowledged in the popular press. When Doris Duke bought the mihrab, it became personal property, and this invaluable example of cultural heritage effectively went underground, buried on multiple levels.

The mihrab’s physical and conceptual fortunes at Shangri La raise many questions about the fates of cultural materials when they enter private hands (fig. 277). While no museum can claim a perfect track record of preservation and no material is inherently safer in any museum (recall Berlin 1945), museum collections are generally safeguarded by principles of collective stewardship and professional oversight, rather than personal whims and entourages. During its original installation at Shangri La, the mihrab was squeezed into a space that could have been structurally modified, resulting in the burying of one of its tiles. It was then hastily deinstalled after the attack on Pearl Harbor and reinstalled after the war by someone lacking professional training. We can only imagine what physical damage it might have endured during these processes and what might have been prevented with institutional safeguards.

The mihrab’s location in a private home had other consequences that extended beyond its physical condition. During Duke’s lifetime, it was only seen by Duke and her guests and friends, and its public presentation was limited to lifestyle and fashion magazines. For decades, its location in Honolulu was unknown and confused, especially by Iranian researchers. When Shangri La was transformed from a home to a museum in 2002, the mihrab re-entered a realm of public visibility, albeit one still limited by Hawai‘i’s remoteness. The launch of Shangri La’s collection online with many color photographs was a positive step in visibility, but its location continued to be confused until 2014, when Sheila Blair published the first detailed analysis of the ensemble, seventy-four years after it entered Shangri La. In sum, the mihrab’s acquisition by Duke exposed it to significant physical and conceptual risk and prolonged its intellectual confusion and stagnation.

Reflections

The historiography of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab inspires a self-reflexive audit on the field of Persian art and architectural history. While the mihrab’s art historical data and significance are well known, it has often been mired in confusion, simplification, exclusion, and isolation, both in English- and Persian-language scholarship. Much of this boils down to access, which has always shaped scholarly engagement. Generally speaking, those who could study the mihrab firsthand focused on it as an isolated artwork, while those who had access to the shrine examined the building independently. Consequently, each side’s understanding of the opposite context remained incomplete or outdated. A 1978 photograph of the tomb—repeated multiple times in museum displays and academic presentations—became the dominant view of the shrine outside of Iran, while scholars inside Iran continued to recycle dated information on the mihrab, including a 1918 photograph.

Political circumstances have reinforced these separations, but the emergence of digital platforms has helped to bridge some of these informational divides. One example is the steady integration of color photography posted on Shangri La’s website into Persian scholarship. Another is the digitization of critical archives, including Dieulafoy’s photo albums and Kevorkian’s correspondence with Charles Freer.252 This website has likewise sought to resolve these disconnects by prioritizing transnational collaboration and making archives and collections more accessible through films and generous reproduction. A considerable portion of the visual material in this essay is unpublished and undigitized archives (fig. 278).

One way to bridge the problem of access is through collaboration, which is also the foundation of this study and has facilitated a relatively balanced approach to archives, bibliographies, and perspectives. The field would benefit from more collaboration between scholars trained in different disciplines, familiar with various methods, and working inside and outside of Iran. Outside of Iran, and particularly in some European and American universities and museums, archival and dated photographs require contextualization, visual curation can be expanded to capture evolving realities, and detached academic and museological frames would ideally acknowledge different forms of meaning and significance. Among researchers working in Iran, there is a need to move beyond the shadow of established scholars and received knowledge, continue original research grounded in firsthand documentation, and move toward synthetic results that engage with broader discussions in the field. The discipline at large would benefit from deeper research on individuals and networks involved in the displacement, commodification, and aestheticization of Iran’s cultural materials. Only through reciprocal collaboration can the study of Persian architectural heritage transcend inherited narratives, develop a deeper understanding of its material, historical, and historiographical realities, and move toward a more dynamic future.

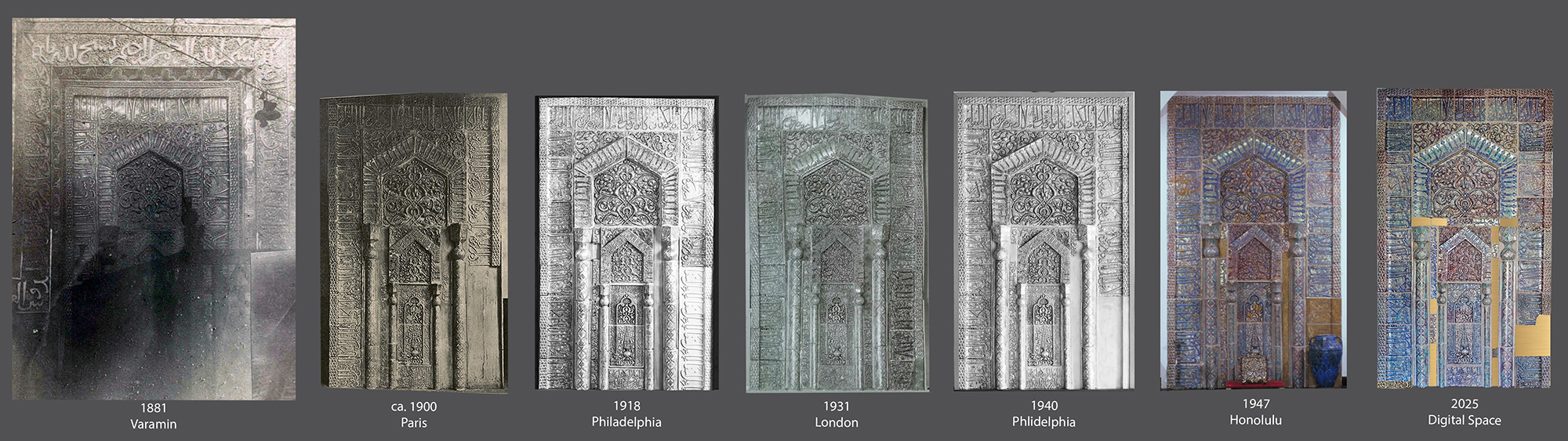

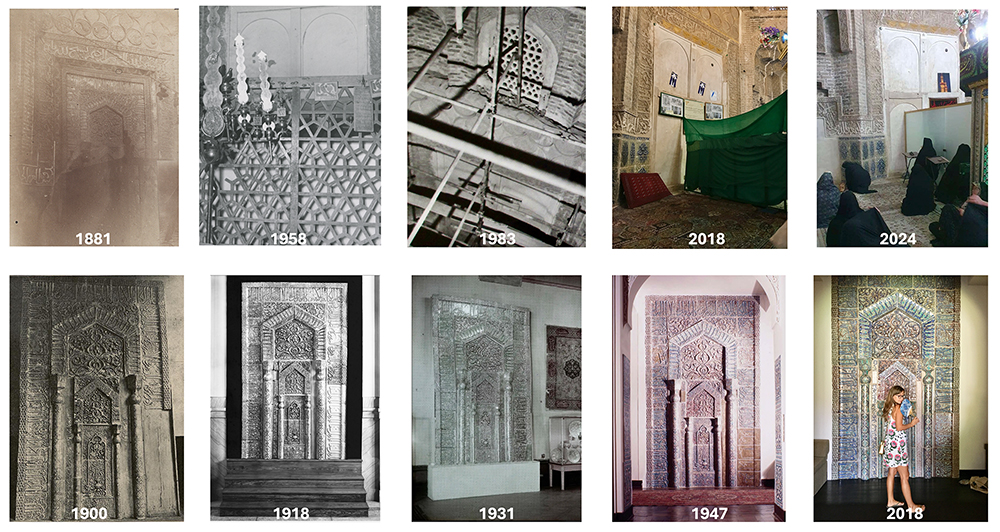

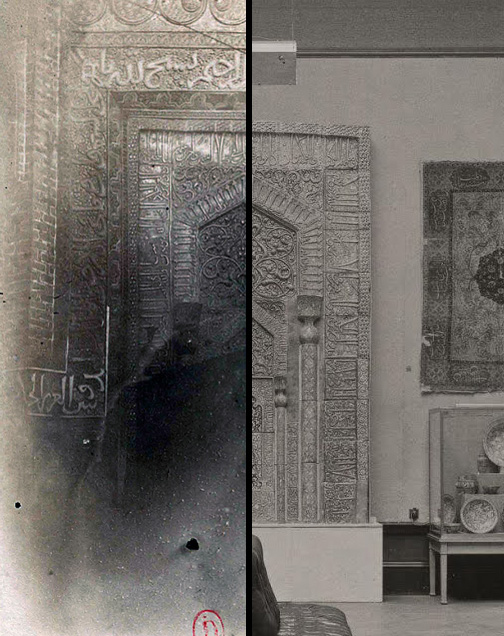

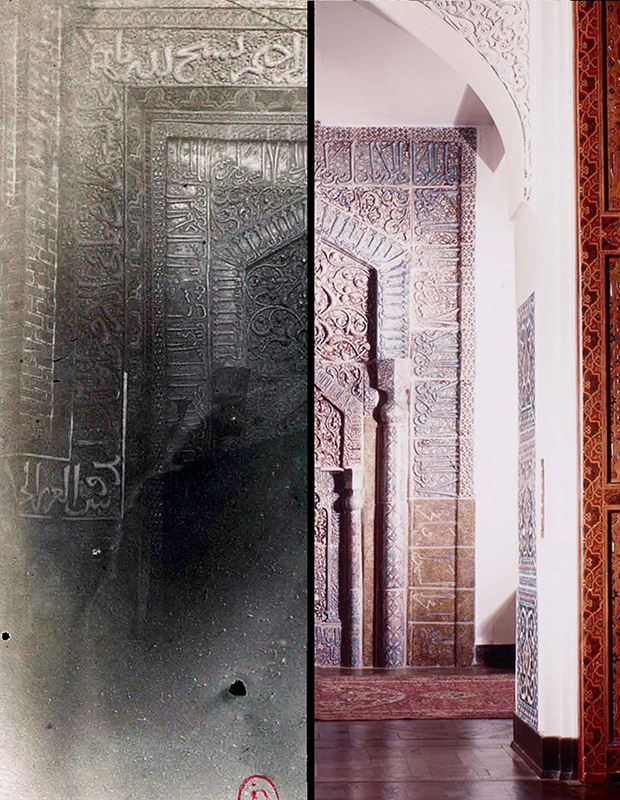

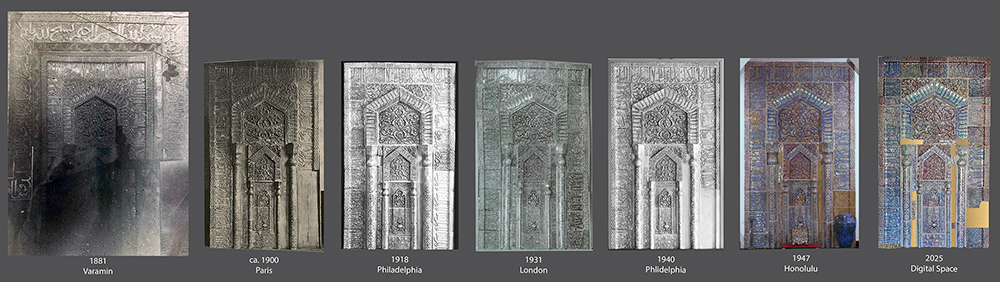

This historiography has underscored how much more there is to learn about the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab and how many ways it can be seen and re-seen. During this study, some major physical alterations to the mihrab were illuminated through repeated close looking with fresh eyes, even at a distance. Moreover, the mihrab’s visual archive was expanded far beyond Jane Dieulafoy’s 1881 photograph of it in situ, thus revealing its steady transformations over six decades (fig. 279). These photographs capture the mihrab in varying physical states: tiles missing, tiles jumbled, surfaces damaged, and the ensemble ostensibly ‘completed’ with various substitutes.

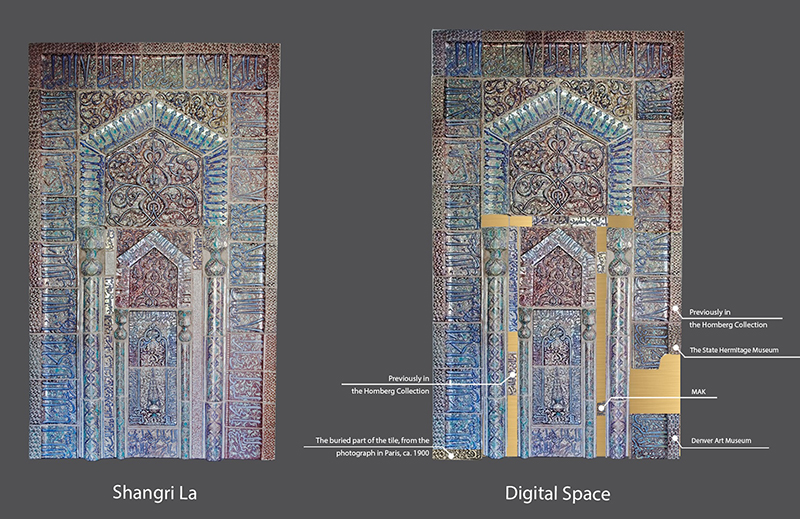

In a digital environment, we have the opportunity to reimagine and partially restore some of this inaccuracy and incompleteness. The visual timeline above begins with Dieulafoy’s photograph of the mihrab in situ and deliberately includes some of the surrounding qibla wall, which is notable for its soaring verticality, a stark contrast to the mihrab’s current claustrophobic setting. The final image—a digital visualization—achieves several goals (fig. 280). It moves currently jumbled tiles to their correct locations and re-places the three tiles in the lower right border (the tile in between those now in the Denver Art Museum and Hermitage remains to be identified). It also reconstitutes the inner border by indicating its original upper horizonal row, thus increasing the mihrab’s height and balancing its proportions, and reuniting the isolated tile now in the MAK. Finally, the buried tile on the lower left is reearthed and re-seen via an archival photograph. The virtually reunited tiles are labeled by their current repositories, and still missing pieces are left blank, with the hope that they might be found one day. The study of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab is by no means done or exhausted, and we will continue to add to its layers of understanding. Other museumized masterpieces might warrant similar revisitations and expansions.

When the mihrab was removed from the tomb of Yahya b. ʿAli and the Emamzadeh Yahya complex as a whole—its home of over six hundred years—it entered a state of unprecedented risk and mobility. In addition to surviving two world wars and the vulnerabilities of being personal property in a private home for fifty-three years, it was shipped across an ocean six times and installed and deinstalled for exhibition at least seventeen times in forty-six years.253 This figure is staggering for such a large, heavy, and complex multi-unit ensemble and prompts reflection on today’s museumscape, wherein architectural elements are often perceived as fixed, and hyper-preciousness can prohibit researchers from handling broken luster tile fragments in storage, even when wearing gloves. The mihrab’s resilience and layered evolution recalls that of the Emamzadeh Yahya complex itself, and the addition of the mihrab’s visual timeline to this website facilitates a shared exploration of their trajectories, furthering their reconnection (fig. 281). Neither story can be told irrespective of the other.

This historiography has aimed to gather, organize, and reunite the dispersed fragments of the mihrab’s history—both its literal tiles and its archives—and present them in a readable narrative. It has sought to make information accessible, coherent, and transparent, and we have intentionally avoided definitive conclusions or judgements, preferring to allow the evidence to speak for itself and have space to be digested. Like most masterpieces of Iranian cinema, this story is intentionally left open-ended. The audience becomes the judge and is free to imagine what might constitute the mihrab’s rightful place physically, historically, and ethically. We trust that new conversations and responsibilities will emerge with time.

Citation: Keelan Overton and Hossein Nakhaei, “From Varamin to Honolulu: The Displacement, Commodification, and Aestheticization of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s Luster Mihrab, 1863–2025.” Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, November 16, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.

Notes

- The NMAAA digitization critically includes both photographic materials and paper correspondence. It is hoped that other archives will likewise prioritize the release of both sets of materials, thus leveling access for researchers who face travel restrictions. ↩

- This count considers installation and deinstallation for seven displays in Europe and the mainland United States as well as the December 1940 installation at Shangri La, December 1941 deinstallation, and July 1946 reinstallation. ↩

Bibliography

Sources: Archives in Iran

- Central Library and Documentation Center, University of Tehran, Tehran [UT Library]

- Library, Museum and Document Center of the Islamic Parliament of Iran, Tehran

- Malek National Library and Museum Institution, Tehran [malekmuseum]

- National Library and Archives of Iran, Tehran [NLAI]

- اعتضادالسلطنه، علیقلی میرزا. «شرح حالات امامزاده یحیی». مورخ محرم ۱۲۹۴ ق. در: جنگ نظم و نثر، نسخهی دستنویس در کتابخانهی مجلس شورای اسلامی در تهران، شمارهی ۱۴۵۳سس.، ۵۶ الف – ۵۶ ب.

نامعلوم. [گزارش سفر ورامین به همراه کاروان ناصرالدینشاه قاجار]. مورخ شعبان ۱۲۷۹ق. نوشتهشده به دستور علیقلی میرزا اعتضادالسلطنه. در: جنگ نظم و نثر، نسخهی دستنویس در کتابخانهی مجلس شورای اسلامی در تهران، شمارهی ۱۴۵۳سس.، ۵۷ الف.

The two texts above are combined as:

“Sharh-e halat-e Emamzadeh Yahya” (Biography of Emamzadeh Yahya), dated Moharram 1294/January 1877 (56a–56b) and Varamin field notes from the royal visit in Shaʿban 1279 AH/January 1863 (57a), preserved in a jong compiled for ʿAliqoli Mirza Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh. The Library, Museum and Document Center of the Islamic Parliament of Iran (Ketabkhaneh, Muzeh va Markaz-e Asnad-e Majles-e Shora-ye Eslami), Tehran, accession number 1453/س.س. ۱۴۵۳, fols. 56a–57a.

- اعتمادالسلطنه، محمدحسن خان. «اخبار داخله: دربار همایون.» . در: ایران، شمارهی ۳۰۵ (۷ ذیالحجه ۱۲۹۳ق.): ۱-۳. سازمان اسناد و کتابخانه ملی ایران، ۱۰۱۴۵۷۴.

Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, Mohammad Hasan Khan. “Akhbār-e dākheleh: Darbār-e homāyūn.” Iran 305 (24 December 1876): 1–3. National Library and Archives of Iran, Tehran, 1014574.

- «پرونده ثبت امامزاده یحیی ورامین.» تهیه توسط سازمان حفظ بناهای تاریخی، ۹ مرداد ۱۳۱۲ش. بازبینی و اضافات توسط سازمان میراث فرهنگی کشور، ۱۳۷۵ش. مرکز اسناد و مدارک سازمان میراث فرهنگی کشور، شمارهی ۱۹۹. دستیابی از وبگاه دانشنامهی تاریخ معماری و شهرسازی ایران (تاریخ دسترسی: بهمن ۱۴۰۲ش.).

“Registration Document of the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin.” Prepared by the Organization for the Preservation of Historical Buildings, 9 Mordad 1312 Sh/31 July 1933. Revised and supplemented by the Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization in 1375 Sh/1996. Center for Documents and Records, Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran, no. 199. Available online in the Encyclopedia of Iranian Architectural History, Iranarchpedia (date of access: February 2024).

- «گزارش نوبت دوم عملیات انجام شده و پیشرفت مرمت بنای تاریخی امامزاده یحیی ورامین.» . تهیه توسط دفتر فنی تهران به سرپرستی محمدحسن محبعلی. ۱۳۶۲ش. مرکز اسناد و مدارک سازمان میراث فرهنگی کشور، ۱۷۹۷.

“Second Phase Report on Completed Operations and Restoration Progress of the Historic Building of Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin.” Prepared by the Tehran Technical Office under the supervision of Mohammad Hasan Moheb-Ali, 1362 Sh/1983–84. Center for Documents and Records, Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran, no. 1797.

- «گزارش عملیات انجام شده و پیشرفت مرمت بنای تاریخی امامزاده یحیی ورامین.» تهیه توسط دفتر فنی تهران به سرپرستی محمدحسن محبعلی. ۱۳۶۳ش. مرکز اسناد و مدارک سازمان میراث فرهنگی کشور، ۱۸۰۱.

“Report on Completed Operations and Restoration Progress of the Historic Building of Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin.” Prepared by the Tehran Technical Office under the supervision of Mohammad Hasan Moheb-Ali, 1363 Sh/1984–85. Center for Documents and Records, Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran, no. 1801.

Sources: Archives in Europe and North America

- Archives nationales/National Archives of France, Paris [ANF]

- Centre des Archives diplomatiques de La Courneuve/Diplomatic Archives Centre in La Courneuve, French Ministry of Culture [CAD]

- Doris Duke Papers on the Shangri La residence, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina [DDPSL]

- Doris Duke Photograph collection, 1880–2006, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina [DDPC]

- Penn Museum Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania [PMA]

- Arthur Upham Pope papers, Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library [NYPL]

- National Museum of Asian Art Archives, Washington, DC [NMAAA]

- MAK Digital Library, Vienna [MAK]

- MAK Aktenarchiv, Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna [MAK]

- V&A Archives, London [V&A Archive]

Exhibition Catalogs, Sales Catalogs, and Museum and Collection Monographs, circa 1873–1941

*This section of the bibliography is presented in chronological order. The locations and dates of the sale or exhibition are included in brackets. Some contemporary reviews are included, as well as some related texts with a commercial component and/or that fueled demand.

- Special-Catalog der Ausstellung des Persischen Reiches, Weltausstellung 1873 in Wien. Vienna: Persischen Ausstellungs-Commission, 1873. [Austrian National Library]

- Smith, Robert Murdoch. Persian Art. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. [WorldCat]

- “Fine Arts. Persian Art at South Kensington.” The Illustrated London News, 15 April 1876.

- Darcel, Alfred. “Le musée céramique de Sèvres.” Gazette des beaux-arts: Courrier européen de l’art et de la curiosité 20 (July 1879): 77–89. [Gallica]

- [Dieulafoy, “La Perse,” 1883]

- Gonse, Louis. Katalog der Orientalisch-Keramischen Austellung im Orientalischen Museum. Vienna: Verlag des Orientalischen Museums, 1884. [HathiTrust] [WorldCat]

- Wallis, Henry. Illustrated Catalogue of Specimens of Persian and Arab art Exhibited in 1885. London: Burlington Fine Arts Club, 1885. [Google Books]

- [Dieulafoy, La Perse, 1887]

- Wallis, Henry. The Godman Collection. Persian Ceramic Art Belonging to Mr. F. DuCane Godman, F.R.S.; with Examples from Other Collections. The Thirteenth Century Lustred Wall-Tiles. London: [Taylor and Francis], 1894. [Internet Archive] [WorldCat]

- Baschet, Maurice, and Neurdein frères. Le Panorama: Exposition Universelle, 1900. Paris: L. Baschet, 1900. [Internet Archive]

- Pirou, Eugène. Exposition universelle de 1900: Portraits des commissaires généraux. Paris: 1900. [Gallica]

- Delbeuf, Régis. La Turquie et l’Orient à l’exposition de 1900. Constantinope: 1900. [Internet Archive]

- Léra, M. “Les nations a l’exposition: L’Espagne, la Turquie et la Perse.” Le Mois littéraire et pittoresque (October 1900): 474–85. [Gallica]

- Mannheim, Charles, and Hôtel Drouot. Catalogue des Objets d’Art et de Curiosité, Anciennes Faïences Italiennes et Orientales, Étoffes Européennes et Orientales, Tapis d’Orient. Paris: 1900. [Paris, 23 February 1900] [Gallica]

- Mannheim, Charles, and Hôtel Drouot. Catalogue des Objets d’Art et de Curiosité, Faïences & Porcelaines. Paris: 1900. [Paris, 14–16 June 1900] [Gallica]

- Mannheim, Charles, and Hôtel Drouot. Objets de la Perse, Importante Plaque de Revêtement, Paris: 1900. [Paris, 16 December 1900] [Gallica]

- Godman, Frederick Du Cane. The Godman Collection of Oriental and Spanish Pottery and Glass, 1865-1900. London: Taylor and Francis, 1901. [WorldCat]

- Migeon, Gaston. Cèramique orientale a reflets métalliques. Paris: Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 1901. [Internet Archive]

- Migeon, Gaston. Exposition des Arts Musulmans: Au Musée des Arts Décoratifs. Paris: Librarie Centrale des Beaux-Arts, 1903. [Paris, April 1903] [Internet Archive]

- Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs. Exposition des Arts Musulmans. Paris: Société Française d’Imprimerie et de Librairie, 1903. [Internet Archive]

- Migeon, Gaston, and Henri Saladin. Manuel d’art musulman. Paris: A. Picard, 1907. [Internet Archive]

- Galerie Georges Petit. Catalogue des objets d’art et de haute curiosité orientaux & européens : composant la collection de feu M.O. Homberg. Paris: Georges Petit, 1908. [Paris, 11–16 May 1908] [Clark Art]

- Kelekian, Dikgran G. The Kelekian Collection of Persian and Analogous Potteries, 1885–1910. Paris: H. Clarke, 1910. [Internet Archive]

- Meisterwerke muhammedanischer Kunst. Ausstellung München 1910, amtlicher Katalog: Ausstellung von Meisterwerken muhammedanischer Kunst, Musikfeste, Muster-Ausstellung von Musik-Instrumenten. München: Verlag von Rudolf Mosse, 1910. [Munich, 14 May–9 October 1910] [Heidelberg University Digital Library] [Metropolitan]

- [Sarre, Denkmäler Persischer Baukunst, 1910]

- “To Display Rare Ceramics: Hagop Kevorkian Coming Here with Examples of a Lost Decorative Art.” The New York Times, 27 February 1910. [The New York Times]

- d’Allemagne, Henry-René. Du Khorassan au Pays des Backhtiaris, Trois mois de voyage en Perse, vol. 2. Paris: Hachette et Cie, 1911. [Internet Archive]

- The Persian Art Gallery [Hagop Kevorkian] and Galeries Barbazanges. Exposition de Céramiques Persanes de Miniatures et Manuscrits. 1911. [Paris, 7 April–2 May 1911]

- The Persian Art Gallery [Hagop Kevorkian]. Catalogue of the Kevorkian Collection of Persian Ceramics from the Caliphate Epoch (AD.700) to the 17th Century. London: Persian Art Galleries, 1911. [London, 15 June–28 July 1911]

- Galeries Henry Barbazanges [and Hagop Kevorkian]. Catalogue d’Exposition d’Art Musulman. 1911. [Paris, 3 November–3 December 1911]

- Persian Art Galleries [Hagop Kevorkian] and The Folsom Galleries. Exhibition of Mohammedan Art from the Caliphate Epoch to the XVIII Century. The Persian Art Galleries, 1912. [New York, 17 January–10 February 1912] [Smithsonian Libraries]

- The Galleries of Charles of London [and Hagop Kevorkian]. Exhibition of the Kevorkian Collection Including Objects Excavated Under His Supervision. Exhibited at the Galleries of Charles of London. New York: Lent & Graff Co., 1914. [New York, March–April 1914] [Internet Archive]

- Wilson, Arnold Talbot, and Royal Academy of Arts. Catalogue of the International Exhibition of Persian Art: 7th January to 7th March, 1931, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 3rd edition. London: Office of the Exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts, 1931. [London, 7 January–7 March 1931] [Royal Academy]

- Ashton, Leigh, Reginald Theodore Blomfield, Roger Fry, Arthur Upham Pope, and Arnold Talbot Wilson. Persian Art: An Illustrated Souvenir of the Exhibition of Persian Art at Burlington House, London, 1931, 2nd edition. London: Hudson & Kearns, Ltd., 1931. [Internet Archive]

- Ackerman, Phyllis. “L’exposition d’art Iranien a Leningrad.” Syria 17, 1 (1936): 45–52. [JSTOR]

- [Pope and Ackerman, eds., A Survey of Persian Art, 1938–39]

- Ackerman, Phyllis. Guide to the Exhibition of Persian Art. New York: The Iranian Institute, 1940. [New York, April–May 1940] [Internet Archive]

- Jewell, Edward Alden. “Persian Exhibition of Art is Opened: Iranian Institute Presents a Benefit in the Interests of Crippled and Disabled. 6,000 Years Represented. Rare Carpets, Tapestries, and Textiles Along With Potteries Are Among Items.” The New York Times, 24 April 1940.

- Ettinghausen, Richard. “‘Six Thousand Years of Persian Art’ the Exhibition of Iranian Art New York, 1940.” Ars Islamica 7, 1 (1940): 106–17. [JSTOR]

- Hammer Galleries. Art Objects & Furnishings from the William Randolph Hearst Collection: Catalogue Raisonné Comprising Illustrations of Representative Works. New York: Publishers Print, Co., 1941. [WorldCat]

Sources: Persian

- آذری دمیرچی، علاءالدین. جغرافیای تاریخی ورامین. تهران: بی نا، ۱۳۴۸ش. [Azari Damirchi, Joqrāfīyā-ye tārīkhī-ye Varāmīn] [WorldCat] [Lib.ir]

- آذری، علاءالدین. «ورامین». در: محمد یوسف کیانی (ویراستار)، شهرهای ایران، ج. ۳، ۲۳۴-۲۵۱. تهران: وزارت فرهنگ و ارشاد اسلامی، ۱۳۶۸ش. [Azari, “Varāmīn”] [WorldCa]

- اعتمادالسلطنه، محمدحسن خان. رسائل اعتمادالسلطنه. تدوین میرهاشم محدث. تهران: اطلاعات، ۱۳۹۱ش. [Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, Rasāʾel] [WorldCat] [Lib.ir]

- امینی، محمد و همایون رضوان. تاریخ اجتماعی ورامین از ابتدا تا عصر پهلوی. ورامین: انتشارات علمی فرهنگی صاحبالزمان، ۱۳۸۲ش. [Amini & Rezvan, Tārīkh-e ejtemāʿī-ye Varāmīn az ebtedā tā ʿasr-e Pahlavī] [Lib.ir]

- بحرالعلومی، حسین. کارنامهٔ انجمن آثار ملی از آغاز تا ۲۵۳۵ شاهنشاهی. تهران: انجمن آثار ملی، ۱۳۵۵ش. [Bahr al-Olumi, Kārnāmeh-ye anjoman-e āthār-e mellī] [Ketabnak]

- بنیاد ایرانشناسی. شماری از بقعهها، مرقدها و مزارهای استان تهران و البرز. ج. ۲: شهرستانهای شهریار، فیروزکوه، کرج، نظرآباد و ورامین. طرح، بررسی و تدوین حسن حبیبی. تهران: بنیاد ایرانشناسی، ۱۳۸۹ش. [Bonyad Iranshenasi, Shomārī az boqʿehā] [WorldCat] [Lib.ir]

- بهرامی، مهدی. صنایع ایران: ظروف سفالین. تهران: انتشارات دانشگاه تهران، ۱۳۲۷ش. [Bahrami, Sanāyeʿ-e Irān] [WorldCat]

- بهرمان، علیرضا. محراب زرینفام حرم مطهر مولی متقیان امام علی (ع): بازخوانی محراب زرینفام هشتصد ساله فراموششده حرم مطهر مولی متقیان امام علی (ع). تهران: طراحان ایماژ، ۱۳۹۷ش. [Bahraman, Alireza, Mehrāb-e zarrīn-fām-e haram-e moṭahhar-e mawlā-ye mottaqiyān Emām ʿAlī (ʿa)]

- پرورش ریزی، مرضیه و شادابه عزیزپور. «مطالعه تطبیقی تزیینات امامزاده جعفر اصفهان و امامزاده یحیی ورامین». در: اصغر منتظرالقائم، محمد مهرابی، احمد شرفخانی (ویراستاران)، امامزادگان تجلیگاه هنر قدسی: بررسی تزیینات و آرایهها در بقاع متبرکه. تهران: سازمان چاپ و انتشارات وزارت فرهنگ و ارشاد اسلامی، ۱۳۹۳ش. [Parvaresh and Azizpour, “Motāleʿe-ye tatbīqī-ye tazʾīnāt-e Emāmzādeh Jaʿfar-e Esfahān va Emāmzādeh Yaḥyā-ye Varāmīn”] [Rasekhoon]

- پوپ، آرتور اپهام. «هنر سفالگری و کاشیسازی در دوران اسلامی. الف: تاریخچه». ترجمهی فاطمه کریمی. در پوپ و اکرمن، سیری در هنر ایران، زیر نظر سیروس پرهام، ج. ۴ و ۸، تهران: انتشارات علمی و فرهنگی، ۱۳۸۷ش. [Pope, “Honar-e sofālgarī va kāshī-sazī dar dowrān-e eslāmī: alef. tārīkhcheh”]

- تبریزی، میرزا حسن. «اخبار خارجه غیررسمی». در: ایران، شمارهی ۶۱ (۱۵ شوال ۱۲۸۸ق.): ۳. روزنامه ایران، ج. ۱: شماره:۱-۲۰۸. تهران: کتابخانه ملی جمهوری اسلامی ایران، ۱۳۷۴ش. [Tabrizi, “Akhbār-e khāreje-ye gheyr-e rasmī”] [Ketabnak]

- تبریزی، میرزا حسن. «اخبار مختلفه». در: ایران، شمارهی ۱۰۲ (۷ ربیعالثانی ۱۲۸۹ق): ۴. روزنامه ایران، ج. ۱: شمارهی:۱-۲۰۸. تهران: کتابخانه ملی جمهوری اسلامی ایران، ۱۳۷۴ش. [Tabrizi, “Akhbār-e mokhtalefeh”] [Ketabnak]

- تقوینژاد، بهاره و صدیقه میرصالحیان. «آرایههای گچبری بقعه امامزاده یحیی ورامین». در: اصغر منتظرالقائم، محمد مهرابی، احمد شرفخانی (ویراستاران)، امامزادگان تجلیگاه هنر قدسی: بررسی تزیینات و آرایهها در بقاع متبرکه. تهران: سازمان چاپ و انتشارات وزارت فرهنگ و ارشاد اسلامی، ۱۳۹۳ش. [Taghavi Nejad and Mirsalehian, “Ārāyeh-hā-ye gachborī-ye boqʿeh-ye Emāmzādeh Yaḥyā-ye Varāmīn”] [Rasekhoon]

- دیولافوا، ژان. ایران، کلده و شوش. ترجمهی علی محمد فرهوشی. تهران: انتشارات دانشگاه تهران، ۱۳۳۲ش. [Dieulafoy, Īrān, Kaldeh and Shūsh] [Ketabnak]

- ساعدنیوز. «خاطره تکان دهنده ناصرالدین شاه از موزه لوور». ۱۴ مرداد ۱۴۰۴ش. [Saednews, “Khāṭere-ye tekān-dehande-ye Nāṣer al-Dīn Shāh az Mūze-ye Lūvr”] [Saednews]

- طباطبایی، محمد. یادداشتهای سید محمد طباطبایی از انقلاب مشروطیت ایران. به کوشش حسن طباطبایی. تهران: نشر آبی، ۱۳۸۴ش. [Tabataba’i, Yāddāsht-hāye Seyyed Mohammad Tabātabā’ī] [WorldCat]

- طرفداری، علیمحمد. از گنجیابی تا باستانشناسی: ایرانشناسان اروپایی و باستانشناسی ایران در دوره قاجار و پهلوی اول. تهران: سازمان اسناد و کتابخانه ملی ایران، ۱۳۹۸ش. [Tarafdari, Az Ganjyābī tā bāstānshenāsī] [Gisoom]

- طهماسبپور، محمدرضا. ناصرالدین، شاه عکاس: پیرامون تاریخ عکاسی ایران. تهران: نشر تاریخ ایران، ۱۳۹۲ش. [Tahmasbpour, Nāṣer al-Dīn, shah-e akkās]

- عقابی، محمدمهدی (و.). دایرة المعارف بناهای تاریخی ایران در دوره اسلامی/۲: بناهای آرامگاهی. تهران: پژوهشگاه فرهنگ و هنر اسلامی، ۱۳۷۶ش. [Oqabi, Banāhā-ye ārāmgāhī] [WorldCat]

- علوی، میرزا ابوالحسن. «رجال صدر مشروطیت». در: یغم، شمارهی ۵۰ (مرداد ۱۳۳۱ش.): ۲۱۶-۲۲۲. [Alavi, “Rejāl-e sadr-e mashrūtīat] [Noormags]

- فرخفر، فرزانه و محمد زهدی. «تحلیل مضمونی و تصویری محراب امامزاده یحیی ورامین، شاهکار زرینفام عصر ایلخانی و بزرگترین محراب زرینفام ایران». در تاریخ روایی، شمارهی ۹ (تابستان ۱۳۹۷ش.): ۱۰۹-۱۳۹. [Farrokhfar and Zohdi, “Taḥlīl-e maḍmūnī va taṣvīrī-e meḥrāb-e Emāmzādeh Yaḥyā Varāmīn”] [Noormags]

- فیض قمی، عباس. گنجینهٔ آثار قم، جلد دوم. قم: مهر استوار، ۱۳۵۰ش. [Feyz, Ganjīneh-ye āthār-e Qom] [WorldCat]

- کاشانی، ابوالقاسم عبدالله. عرایس الجواهر و نفایس الاطایب. به کوشش ایرج افشار. تهران: انتشارات انجمن آثار ملی، ۱۳۴۵ش. [Kashani, ʿArāyes al-jawāher va nafāyes al-aṭāyeb] [WorldCat]

- مدرسی طباطبایی، حسین. . تربت پاکان قم. ج. ۲. قم: مهر قم، ۱۳۵۵ش. [Modarressi, Torbat-e pākān-e Qom] [WorldCat]

- مستوفیالممالک، میرزا حسن خان. «یک: به تعریف درنمیآید، باید دید.» در معزی و خسرونژاد (و.)، حظ کردیم و افسوس خوردیم، تهران: اطراف، ۱۴۰۳ش.، ۲۱- ۷۴. [Mostowfi al-Mamalek, “Be taʿrīf dar nemīāyad”] [WorldCat]

- معزی، فاطمه و پدرام خسرونژاد (و.). حظ کردیم و افسوس خوردیم: گزارش سفر به اروپا از میان نوشتههای میرزا حسن خان مستوفیالممالک و دوستعلی خان معیرالممالک. تهران: اطراف، ۱۴۰۳ش. [Moezzi and Khosronejad, Haz kardīm va afsūs khordīm] [WorldCat]

- ناصرالدین شاه قاجار. گزارش شکارهای ناصرالدین شاه قاجار ۱۲۸۱-۱۲۷۹ ه.ق. تصحیح و پژوهش فاطمه قاضیها. تهران: سازمان اسناد و کتابخانه ملی، ۱۳۹۰ش. [Naser al-Din Shah, Gozāresh-e shekārhā] [WorldCat] [Lib.ir]

- ناصرالدین شاه قاجار. روزنامه خاطرات ناصرالدین شاه قاجار در سفر اول فرنگستان. به کوشش فاطمه قاضیها. تهران: انتشارات سازمان اسناد ملی ایران، ۱۳۷۷ش. [Naser al-Din Shah, Rūznāme-ye khāṭerāt-e Naṣer al-Dīn Shāh dar safar-e avval-e farangestān]

- ناصرالدین شاه قاجار. روزنامه خاطرات ناصرالدین شاه قاجار در سفر سوم فرنگستان. به کوشش محمداسماعیل رضوانی و فاطمه قاضیها. تهران: انتشارات سازمان اسناد ملی ایران، ۱۳۶۹ش. [Naser al-Din Shah, Rūznāme-ye khāṭerāt-e Naṣer al-Dīn Shāh dar safar-e sevvom-e farangestān] [Ketabnak]

- نیری، حمید. زندگینامه مستوفیالممالک. با همکاری سیفالله وحیدنیا. تهران: انتشارات وحید، ۱۳۶۹ش. [Nayyeri, Zendgīnāme-ye Mostowfī al-Mamālek] [Ketabnak]

- وزیری، سعید. تاریخ ورامین. ورامین: بی نا، ۱۳۵۸ش. [Vaziri, Tārīkh-e Varāmīn] [Lib.ir]

Sources: English, German, French, Russian

- Abdi, Kamyar. “Nationalism, Politics, and the Development of Archaeology in Iran.” American Journal of Archaeology 105, 1 (2001): 51–76. [JSTOR]

- Adle, Chahryar, and Yahya Zoka. “Notes et documents sur la photographie Iranienne et son histoire.” Studia Iranica 12, 1 (1983): 249–80.

- Aga-Oglu, Mehmet. “Fragments of a Thirteenth Century Miḥrāb at Nedjef.” Ars Islamica 2, 1 (1935): 128–31. [JSTOR]

- Akbari, Abbas. An Oriental Devotion. Kashan: Ceramic House Institute, 2015.

- Akbari, Abbas. In Aun Gallery. Tehran: Aun Gallery, [n.d.].

- Akbari, Abbas. “An Oriental Devotion.” 13 April 2021. [YouTube]

- Akbari, Abbas. “Spring in Varamin’s Lustre Flowerpot.” 20 March 2023. [YouTube]

- Akbarnia, Ladan, and Fahmida Suleman. “Transforming Curatorial Practices for the Global Museum: Reflections on the British Museum’s Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World.” Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World 3, 2 (2023): 299–342. [Brill]

- ASADI. “Sacred Fire.” 21 May 2024. [Instagram]

- Bakhash, Shaul. “Nāṣer-al-molk, Abu’l-Qāsem.” Encyclopædia Iranica, 3 December 2015, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/naser-al-molk-abul-qasem/.

- Blair, Sheila S. “Architecture as a Source for Local History in the Mongol Period: The Example of Warāmīn.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 26, 1–2 (January 2016): 215–28. [Cambridge] [JSTOR]

- Blair, Sheila S. “Art as Text: The Luster Mihrab in the Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art.” In No Tapping around Philology: A Festschrift in Honor of Wheeler McIntosh Thackston Jr.’s 70th Birthday, edited by Alireza Korangy and Daniel J. Sheffield, 407–36. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2014. [WorldCat] [Academia]

- Blair, Sheila S. “Surveying Persian Art in Light of A Survey of Persian Art.” In Arthur Upham Pope and A New Survey of Persian Art, edited by Yuka Kadoi, 371–95. Leiden: Brill, 2016. [Brill]

- Carboni, Stefano, and Tomoko Masuya. Persian Tiles. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993. [Google Books]

- Carey, Moya. Persian Art: Collecting the Arts of Iran for the V&A. London: V&A Publishing, 2017. [WorldCat]

- Crane, Mary E. “A Fourteenth-Century Mihrab from Isfahan.” Ars Islamica 7, 1 (1940): 96–100. [JSTOR]

- Dieulafoy, Jane. “La Perse, La Chaldée et La Susiane.” Le tour du monde: Nouveau journal des voyages (January 1883): 1–80. [Gallica]

- Dieulafoy, Jane. La Perse, la Chaldée et la Susiane: Relation de voyage contenant 336 gravures sur bois d’après les photographies de l’auteur et deux cortes. Paris: Librairie Hachette et Cie, 1887. [Internet Archive]

- Dimand, Maurice S. “A XIV Century Prayer Niche of Faience Mosaic.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 34, 6 (1939): 136–37. [JSTOR]

- Donaldson, Dwight M. “Significant Miḥrābs in the Ḥaram at Mashhad.” Ars Islamica 2, 1 (1935): 118–27. [JSTOR]

- Duke, Doris. “My Honolulu House.” Town & Country, August 1947.

- Ekhtiar, Maryam D., Priscilla P. Soucek, Sheila R. Canby, and Navina Najat Haidar, eds. Masterpieces of Islamic Art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011. [Metropolitan]

- Eskandari-Qajar, Manoutchehr M., ed. and trans. The Artist and the Shah: Memoirs of Life at the Persian Court, from ’Eighty-Five Years of Life in a Few Pages’ & ’Notices on the Private Life of Naser al-Din Shah’. Odenton, MD: Mage Publishers, 2022. [WorldCat]

- Feuvrier, Jean Baptiste. Trois ans à la cour de Perse. Paris: Maloine, 1906. [WorldCat]

- Fromanger, Marine. “Henry Viollet en Perse 1911–1913: l’architecture iranienne à la période islamique d’après une source inédite: Le Fonds Viollet.” PhD dissertation, Aix-Marseille Université I, 2002. [theses.fr]

- Fujii, Jocelyn. “An Islamic treasury by the Pacific: Doris Duke’s romantic estate, Shangri La, is about to open as an art museum.” The New York Times, 27 October 2002. [The New York Times]

- Fulco, Daniel. “Displays of Islamic Art in Vienna and Paris: Imperial Politics and Exoticism at the Weltausstellung and Exposition Universelle.” MDCCC 1800 6 (July 2017): 51–65. [Edizioni Ca’ Foscari]

- Gadoin, Isabelle. Private Collectors of Islamic Art in Late Nineteenth-Century London: The Persian Ideal. New York: Routledge, 2022. [WorldCat]

- Gasche, Herman. “Susa i. Excavations.” Encyclopædia Iranica, 20 July 2009, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/susa-i-excavations.

- Gierlichs, Joachim. “Philipp Walter Schulz and Friedrich Sarre: Two German Pioneers in the Development of Persian Art Studies.” In The Shaping of Persian Art: Collections and Interpretations of the Art of Islamic Iran and Central Asia, edited by Yuka Kadoi and Iván Szántó, 213–36. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013. [Academia]

- Gluck, Jay, and Noël Siver. Surveyors of Persian Art: A Documentary Biography of Arthur Upham Pope & Phyllis Ackerman. Costa Mesa, CA: SoPA, 1996. [WorldCat]

- Godard, Yedda. “Pièces datées de céramiques de Kāshān à décor lustré.” Athar-e Iran 2 (1937): 309–37.

- Grigor, Talinn. “Recultivating ‘Good Taste’: The Early Pahlavi Modernists and Their Society for National Heritage.” Iranian Studies 37, 1 (2004): 17–45. [JSTOR]

- Haji-Qassemi, Kambiz, ed. Ganjnameh: Cyclopaedia of Iranian Islamic Architecture, vol. 13, Emamzadehs and Mausoleums (Part III). Tehran: Shahid Beheshti University Press, 2010. [WorldCat]

- Hedin, Sven. Eine Routenaufnahme durch Ostpersien, vol. 1. Stockholm: Generalstabens Litografiska Anstalt, 1918. [Digital Silk Road]

- Hedin, Sven. Overland to India: with 308 illustrations from photographs, watercolour sketches, and drawings by the author and 2 maps; in two volumes, vol. 1. London: Macmillan, 1910. [Digital Silk Road]

- Helfgott, Leonard M. Ties that Bind: A Social History of the Iranian Carpet. Washington: Smithsonian Institute Press, 1994. [WorldCat]

- Herzfeld, Ernst. “Reisebericht.” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenlandischen Gesellschaft 80 (1926): 225–84. [JSTOR]

- Jenkins-Madina, Marilyn. “Collecting the ‘Orient’ at the Met: Early Tastemakers in America.” Ars Orientalis 30 (2000): 69–89. [JSTOR]

- Kadoi, Yuka. “The Study of Persian Art on the Eve of World War II: The Third Congress of Iranian Art and Archaeology in 1935.” In The Reshaping of Persian Art: Art Histories of Islamic Iran and Central Asia, edited by Iván Szántó and Yuka Kadoi, 117–34. Piliscsaba: The Avicenna Institute of Middle Eastern Studies, 2019. [Academia]

- Kennedy, Thalia. “Doris Duke and Gandhi: Revitalising Crafts Tradition and the Mughal Suite at Shangri La.” Shangri La Working Papers in Islamic Art 3 (July 2012): 1–32. [Academia]

- Kratchkowskaya, Vera. “Fragments Du Miḥrāb de Varāmīn.” Ars Islamica 2, 1 (1935): 132–34. [JSTOR]

- Kratchkowskaya, Vera. “Tiles of the Pir Hussein Mausoleum.” In III Международный Конгресс по Иранскому Искусству и Археологии, Ленинград, Сентябрь, 1935: Доклады [Third International Congress on Iranian Art and Archaeology. Reports: Leningrad, September 1935], edited by I. A. [Joseph] Orbeli, 109–13. Moscow: Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1939. [WorldCat]

- Kröger, Jens. Islamische Kunst in Berliner Sammlungen: 100 Jahre Museum für Islamische Kunst in Berlin. Berlin: Parthas, 2004. [WorldCat]

- Kühnel, Ernst. “Dated Persian Lustred Pottery.” Eastern Art 3 (1931): 221–36.

- Lanzilotti, Nāwāhineokalaʻi. “Kilo.” 15 January 2021. [YouTube]

- Lawford, Valentine. “Doris Duke’s Shangri-La.” Vogue, 1 November 1966. [Vogue]

- Lehmann, Wanda. “Persische Lüsterfliesen in Der Sammlung Des MK&G: Imperiale Infrastrukturen Und Die Zerstreuung Architekturgebundener Objekte.” In Sammlungsgeschichten: Islamische Kunst Im Museum für Kunst Und Gewerbe Hamburg (1873–1915), edited by Isabelle Dolezalek, Tobias Mörike, Wibke Schrape, and Tulga Beyerle, 107–16. Heidelberg: arthistoricum.net, 2022. [arthistoricum.net]

- Leone, Anaïs. “Revêtements au lustre métallique dans l'architecture religieuse et funéraire de l'Iran Ilkhânide (1256-1335).” PhD dissertation, Aix-Marseille Université, 2021. [theses.fr]

- Leone, Anaïs. “New Data on the Luster Tiles of ʿAbd al-Samad’s Shrine in Natanz, Iran.” Muqarnas Online 38, 1 (2021): 331–56. [Brill]

- Leoni, Francesca, Dana Norris, Kelly Domoney, Moujan Matin, and Andrew Shortland. “‘The Illusion of an Authentic Experience’: A Luster Bowl in the Ashmolean Museum.” Muqarnas 36, 1 (2019): 229–49. [Oxford University Research Archive]

- [Life], “Life goes Calling.” Life 6, 11, 13 March 1939. [Internet Archive]

- Littlefield, Sharon. Doris Duke’s Shangri La. Honolulu: Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art, 2002. [WorldCat]

- Mahdavi, Shireen. “Rishār Khan.” Encyclopædia Iranica, 24 September 2010, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/rishar-khan.

- Masuya, Tomoko. “Persian Tiles on European Walls: Collecting Ilkhanid Tiles in Nineteenth-Century Europe.” Ars Orientalis 30 (2000): 39–54. [JSTOR]

- McClary, Richard P. Mina’i Ware: A Reassessment and Comprehensive Study of Iranian Polychrome Overglaze Wares through Sherds. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press, 2024. [De Gruyter Brill]

- Mellins, Thomas, and Donald Albrecht, eds. Doris Duke’s Shangri La: A House in Paradise: Architecture, Landscape and Islamic Art. New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2021. [WorldCat]

- Miller, Ashley. “Negotiating ‘Tradition’: Doris Duke's Shangri La and the Transnational Revival of Moroccan Craft and Design.” Shangri La Working Papers in Islamic Art 9 (April 2019): 1–30. [Academia]

- Mousavi, Ali. Persepolis: Discovery and Afterlife of a World Wonder. Boston: De Gruyter, 2012. [WorldCat]

- Nakhaei, Hossein, and Keelan Overton. “The Architectural Heritage of Varamin: From the Sasanian to Early Pahlavi Periods.” Interactive feature in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.

- Nakhaei, Hossein, and Keelan Overton. “The Emamzadeh Yahya Through the Eyes of ʿAliqoli Mirza Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh: Notes from a Qajar Court Visit to Varamin in 1279/1863 and a Biography of Emamzadeh Yahya dated 1294/1877.” Interactive feature in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.

- Nasiri-Moghaddam, Nader. L’archéologie française en Perse et les antiquités nationales, (1884–1914). Paris: Connaissances et Savoirs, 2004. [WorldCat]

- Nasiri-Moghaddam, Nader. “The First British and French Archaeological Investigations in Susa During the 19th Century.” In Geographies of Contact, edited by Caroline Lehni, Fanny Moghaddassi, Hélène Ibata, and Nader Nasiri-Moghaddam. Strasbourg: Presses universitaires de Strasbourg, 2017. [OpenEdition Books]

- Orbeli, I. A. [Joseph], ed. III Международный Конгресс по Иранскому Искусству и Археологии, Ленинград, Сентябрь, 1935: Доклады [Third International Congress on Iranian Art and Archaeology. Reports: Leningrad, September 1935]. Moscow: Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1939. [WorldCat]

- Österreichisches Museum für Angewandte Kunst. Kunst Des Islam: 28. Mai Bis 26. Oktober 1977: Teppiche, Keramiken Und Fayencen, Gläser Und Moscheelampen, Metallarbeiten Aus Den Sammlungen Des Österreichischen Museums Für Angewandte Kunst, Wien: Ausstellung Im Schloss Halbturn. Vienna: Das Museum, 1977. [WorldCat]

- Overton, Keelan. “From Pahlavi Isfahan to Pacific Shangri La: Revivıng, Restoring, and Reinventing Safavid Aesthetıcs, ca. 1920–40.” West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture 19, 1 (2012): 61–87. [JSTOR]

- Overton, Keelan. “Commissioning on the Move: The Cromwells’ Patronage of ‘Living Traditions’ in India, Morocco, and Iran.” In Doris Duke's Shangri La: A House in Paradise: Architecture, Landscape and Islamic Art, edited by Thomas Mellins and Donald Albrecht, 93–113. New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2021. [Academia]

- Overton, Keelan. “Framing, Performing, Forgetting: “The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin.” Platform, September 12, 2022, https://www.platformspace.net/home/framing-performing-forgetting-the-emamzadeh-yahya-at-varamin.

- Overton, Keelan. “Jane Dieulafoy in Varamin: The Emamzadeh Yahya through a Nineteenth-Century Lens.” Getty Research Journal 19 (spring 2024): 61–95. [Getty]

- Overton, Keelan, dir. and ed. The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine. 33 Arches Productions, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online, https://khamseen-emamzadeh-yahya-varamin.hart.lsa.umich.edu.

- Overton, Keelan, and Kimia Maleki. “The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: A Present History of a Living Shrine, 2018–20.” Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World 1, 1–2 (2020): 120–49. [Brill]

- Overton, Keelan, and Hossein Nakhaei. “Chronological Overview of the Emamzadeh Yahya Complex, ca. 1200–2024.” Essay in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.

- Osorio, Jamaica Heolimeleikalani. “Call to Prayer.” 6 January 2022. [YouTube]

- Osorio, Jamaica Heolimeleikalani. “Call to Prayer.” Borders in Globalization Review 5, 1 (fall & winter 2023): 48–50. [Link]

- Pierson, Stacey. Private collecting, exhibitions, and the shaping of art history in London: The Burlington Fine Arts Club. New York: Routledge, 2017. [WorldCat]

- Pokorny-Nagel, Kathrin. “‘Vieles ist erreicht, aber noch mehr ist zu thun übrig’: Das österreichische Kunstgewerbemuseum und die Weltausstellung.” In Experiment Metropole: 1873: Wien und die Weltausstellung, edited by Wolfgang Kos and Ralph Gleis, 188–193. Vienna: Czernin, 2014.

- Pope, Arthur Upham. “The Ceramic Art in Islamic Times: The History.” In A Survey of Persian Art from Prehistoric Times to the Present, edited by Arthur Upham Pope and Phyllis Ackerman, vol. 4. London: Oxford University Press, 1938–39.

- Pope, “Suggestion Towards the Identification of Medieval Iranian Faience. In III Международный Конгресс по Иранскому Искусству и Археологии, Ленинград, Сентябрь, 1935: Доклады [Third International Congress on Iranian Art and Archaeology. Reports: Leningrad, September 1935], edited by I. A. [Joseph] Orbeli. Moscow: Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1939. [WorldCat]

- Pope, Arthur Upham. “The Architectural Survey Expedition of 1939.” Bulletin of the Iranian Institute 6/7 (1946): 170–95. [JSTOR]

- Pope, Arthur Upham, and Phyllis Ackerman, eds. A Survey of Persian Art from Prehistoric Times to the Present. London: Oxford University Press, 1938–39.

- Proctor-Tiffany, Mariah. “Doris Duke and Mary Crane: Collecting Islamic art for Shangri La, a Hawaiian hideaway home.” Journal of the History of Collections 35, 1 (March 2023): 179–92.

- Reiche, Ina, and Friederike Voigt. “Technology of Production: The Master Potter ‘Ali Muhammad Isfahani: Insights into the Production of Decorative Underglaze Painted Tiles in 19th Century Iran.” In Analytical Archaeometry: Selected Topics. Royal Society of Chemistry, edited by Howell Edwards and Peter Vandenabeele, 502–31. Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2012. [Royal Society of Chemistry]

- Ritter, Markus. “The Kashan Mihrab in Berlin: A Historiography of Persian Lustreware.” In Persian Art: Image-making in Eurasia, 157–78. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017.

- Rizvi, Kishwar. “Art History and the Nation: Arthur Upham Pope and the Discourse On ‘Persian Art’ in the Early Twentieth Century.” Muqarnas 24 (2007): 45–66. [Brill]

- Roxburgh, David J. “Au Bonheur Des Amateurs: Collecting and Exhibiting Islamic Art, ca. 1880-1910.” Ars Orientalis 30 (2000): 9–38. [JSTOR]

- Sadofeev, Dimtry V. “Questions of Attribution of Some Tiles from Mausoleum in Khanqah of Pir Huseyn” [in Russian]. Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. Asian and African Studies 16, 2 (2024): 340–59.

- Sarre, Friedrich. Denkmäler Persischer Baukunst. Berlin: Wasmuth, 1910. [Heidelberg University Digital Library]

- Sarre, Friedrich. “Zwei Persische Gebetnischen aus Lüstrierten Fliesen: I.” Berliner Museen 49, 6 (1928): 126–30. [JSTOR]

- Sarre, Friedrich. “Eine keramische Werkstatt von Kaschan im 13–14. Jahrhundert.” Istanbuler Mitteilungen 3 (1935): 57–69. [WorldCat]

- Sarre, Friedrich, and Fredrick R. Martin, eds. Die Ausstellung von Meisterwerken muhammedanischer Kunst in München, 1910, 3 vols. München: F. Bruckmann, 1912. [vol. 1, Smithsonian Libraries] [vol. 2, Internet Archive]

- Savage, Nicholas. Burlington House: Home of the Royal Academy of Arts. London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2018. [WorldCat]

- Stauffer, Robert H. Kahana: How the Land Was Lost. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2004. [WorldCat]

- Troelenberg, Eva-Maria. “‘The Most Important Branch of Muhammadan Art’: Munich 1910 and the Early 20th Century Image of Persian Art.” In The Shaping of Persian Art: Collections and Interpretations of the Art of Islamic Iran and Central Asia, edited by Yuka Kadoi and Iván Szántó, 237–53. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013. [Academia]

- Türker, Deniz. “Hakky-Bey and His Journal Le Miroir de l’Art Musulman, or Mirʾāt-ı ṣanāyiʿi islāmiye (1898).” Muqarnas 31 (2014): 277–306. [JSTOR]

- Vasilyeva, Daria. “Eighty Years After the Third International Congress on Iranian Art and Archaeology.” In Reports of the State Hermitage Museum LXXIV, 154–72. Saint Petersburg: The State Hermitage Publishers, 2017. [Academia]

- Wharton-Durgaryan, Alyson. “‘I Have the Honour to Inform You That I Have Just Arrived from Constantinople’: Migration, Identity and Commodity Disavowal in the Formation of the Islamic Art Collection at the V&A.” Museum & Society 18, 2 (2020): 258–79. [Museum & Society]

- Wilber, Donald Newton. The Architecture of Islamic Iran: The Il Khānid Period. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1955. [WorldCat]

- Wood, Barry D. “‘A Great Symphony of Pure Form’: The 1931 International Exhibition of Persian Art and Its Influence.” Ars Orientalis 30 (2000): 113–30. [JSTOR]