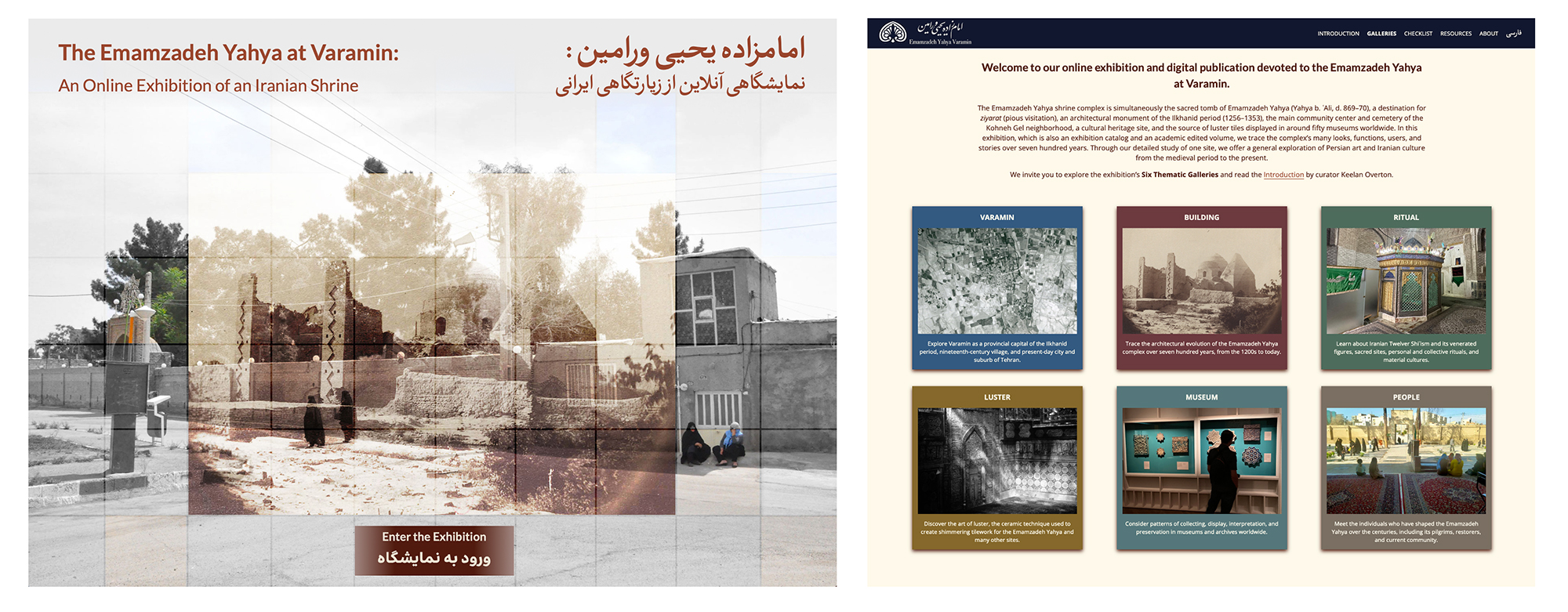

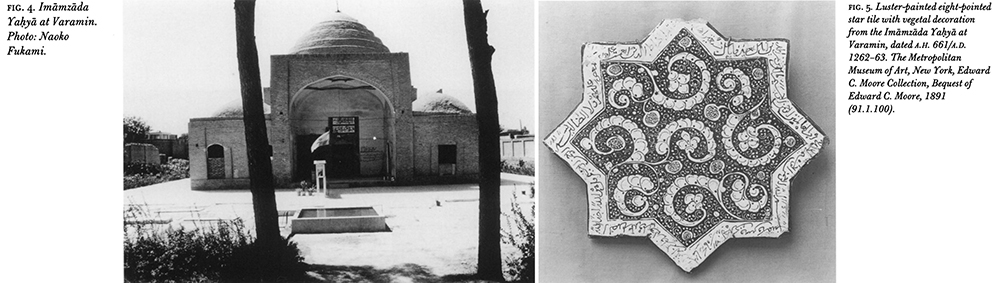

From Varamin to Honolulu: The Displacement, Commodification, and Aestheticization of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s Luster Mihrab, 1863–2025

Keelan Overton and Hossein Nakhaei

Contents:

- Introduction

- Chapter One (Displacement): 1863–1912

- Chapter Two (Commodification): 1912–35

- Chapter Three (Aestheticization): 1937–2025

- Conclusion and Bibliography

Chapter Three (Aestheticization): 1937–2025

This chapter traces Doris Duke’s purchase of the mihrab from Hagop Kevorkian in 1940, the ensemble’s history in her private Hawaiian home, and its popular and scholarly reception since 2002, when Shangri La opened as a public museum.

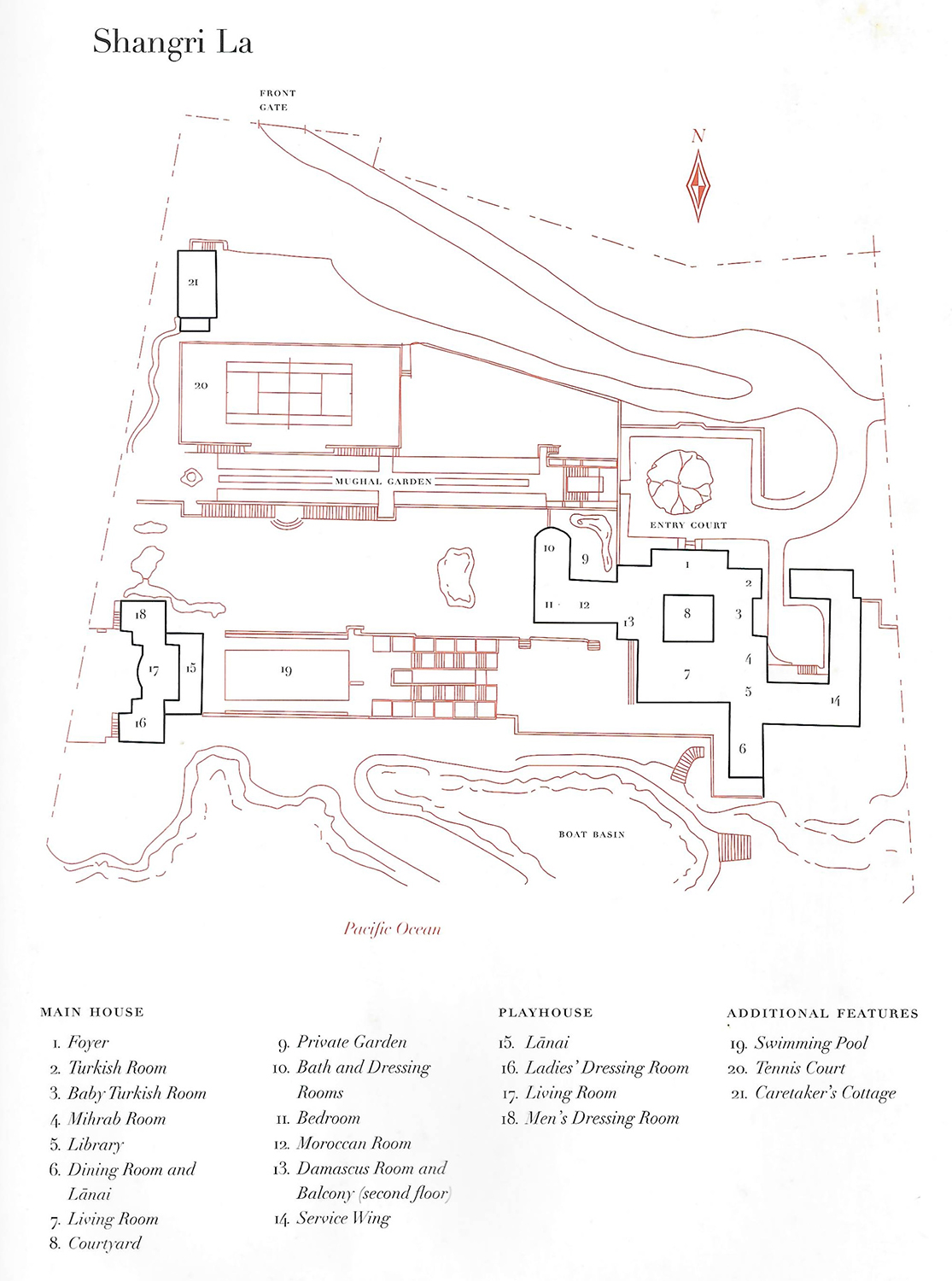

1937: Honolulu, Territory of Hawai‘i

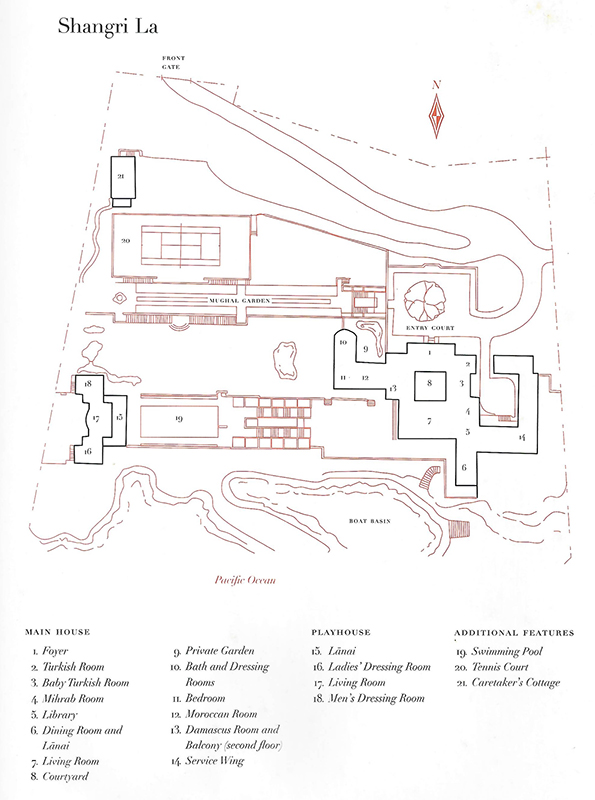

Construction begins on Shangri La, the Honolulu home of Doris Duke Cromwell (d. 1993), the American heiress who will soon acquire the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab. The home is located on a 4.9 acre lot on the Kaʻalāwai (Hawai‘ian, lit., the water [basalt] rock), a coastal area just east of Diamond Head (Lēʻahi) (map) (fig. 137). Marion Sims Wyeth (d. 1982) of Palm Beach is hired as the lead architect and H. Drewry Baker as the onsite supervising architect (fig. 138).

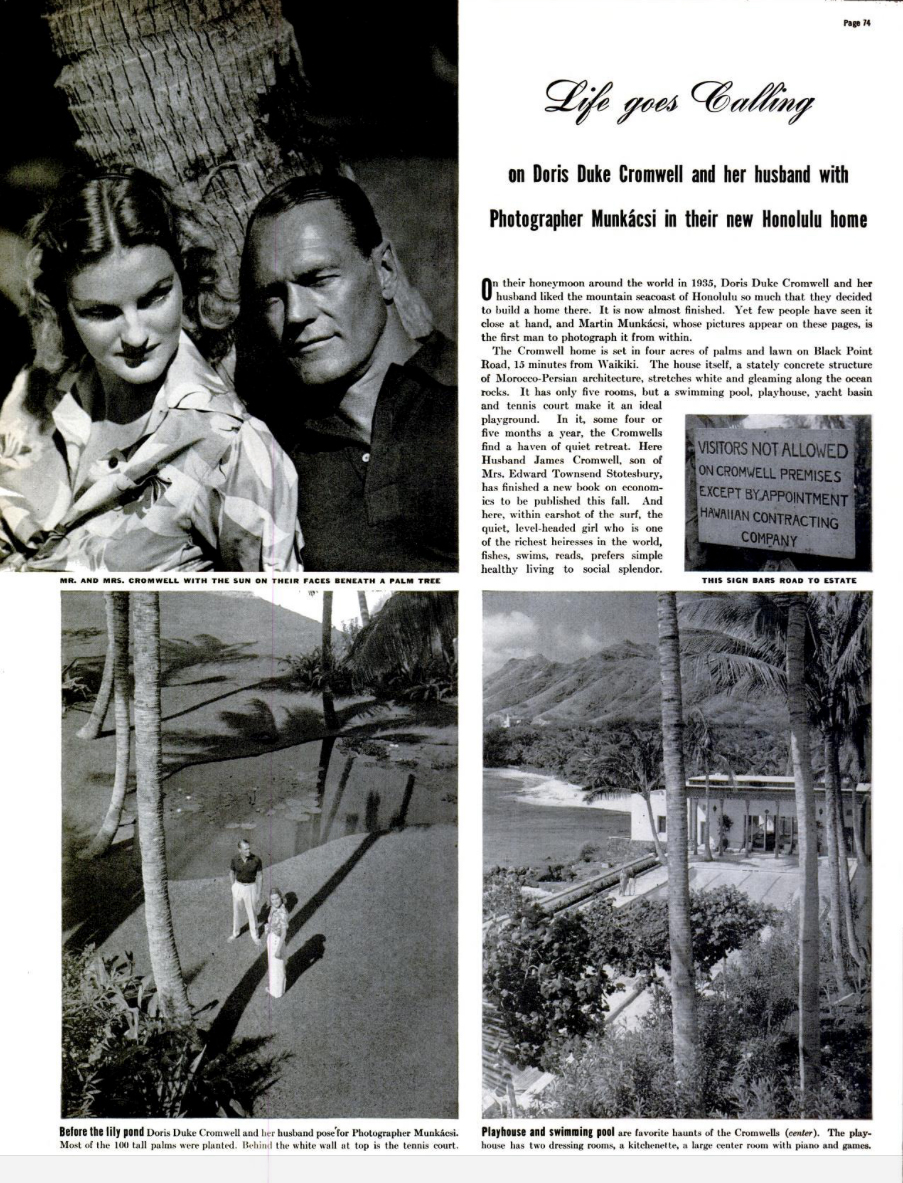

Doris Duke was the only child of tobacco tycoon and industrialist James Buchanan Duke (d. 1925). Upon inheriting her father’s wealth (about $80,000,000) at the age of twelve, she was dubbed “the richest little girl in the world.” In 1935, at the age of twenty-two, she married James Cromwell (d. 1990), and the couple embarked on an around-the-world, six-month honeymoon tour, including India.171 The honeymoon ended in the then Territory of Hawai‘i, and Duke quickly fell in love with the seclusion and lifestyle of the island. In April 1936, the couple purchased the Kaʻalāwai lot from owner Ernest Hay Wodehouse (d. 1957) for $100,000.172

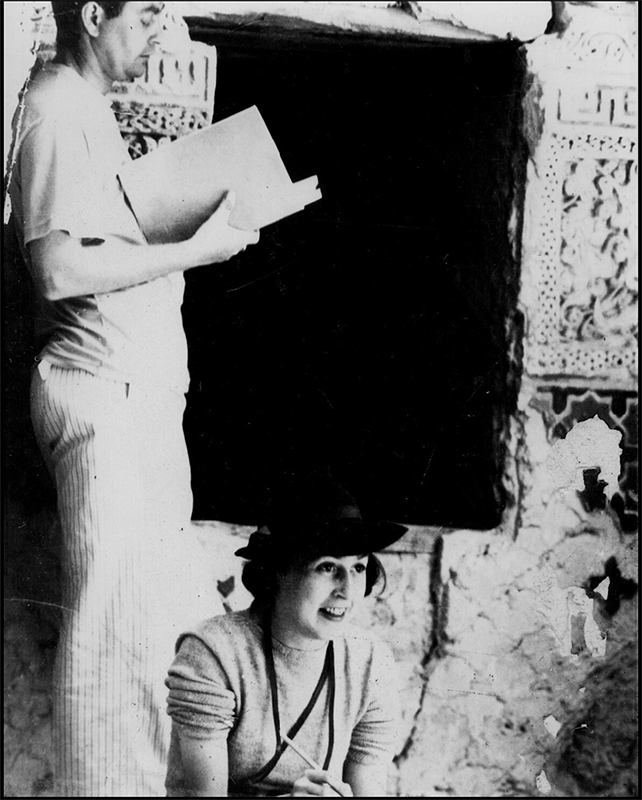

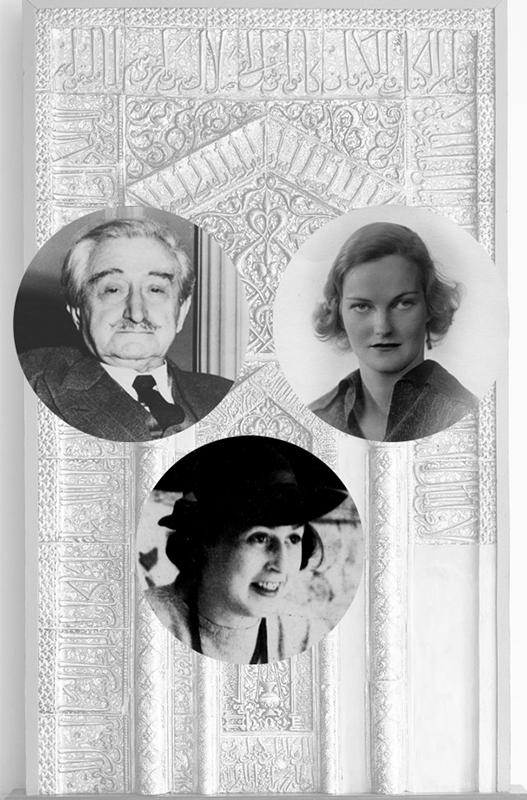

April–May 1938: Iran

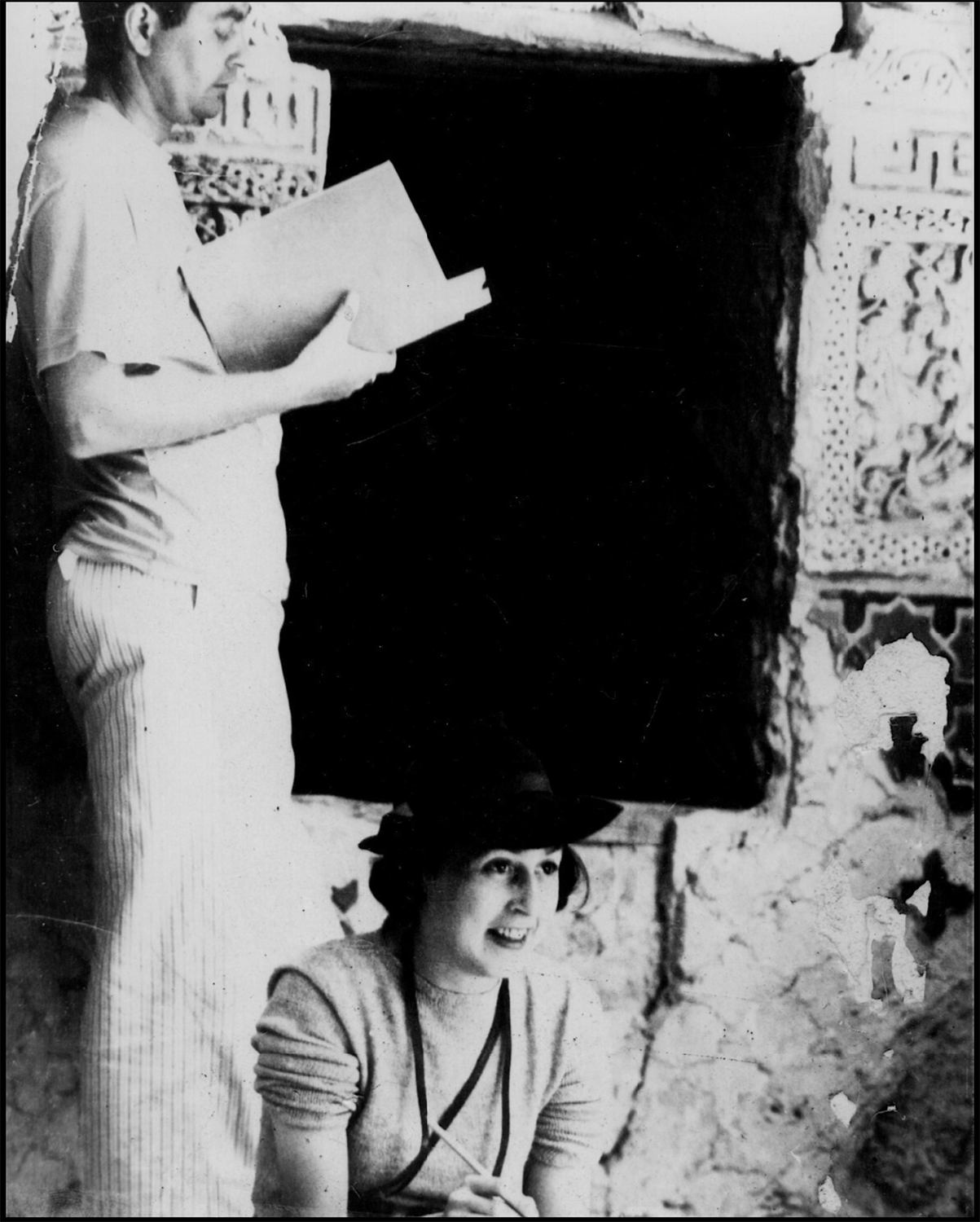

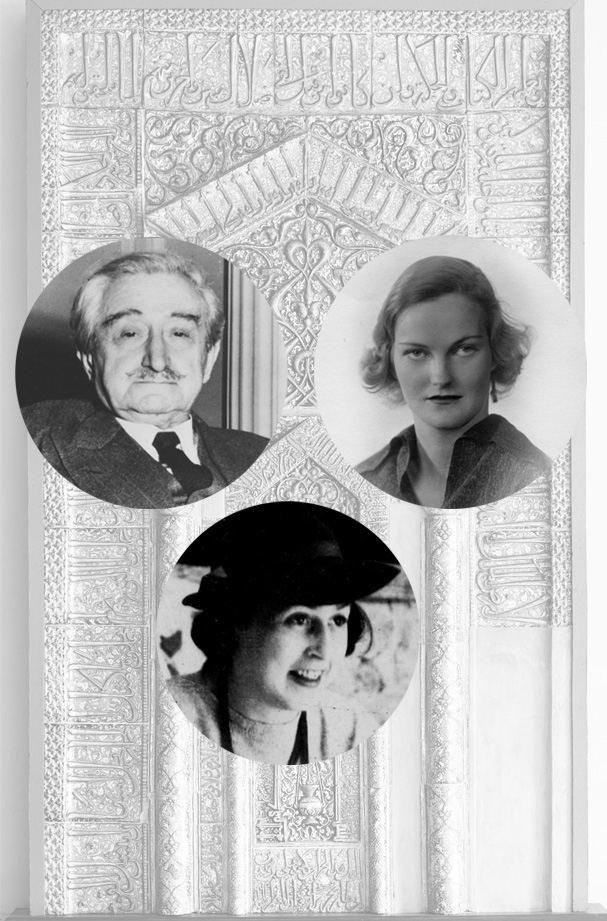

In the spring of 1938, the Cromwells visit Iran for about four weeks during a larger tour of Europe and the ‘Middle East.’ The trip is planned by Arthur Upham Pope, and the couple is accompanied by Mary Crane (d. 1978), a twenty-seven-year-old graduate student at the Institute of Fine Arts (New York University), who also works for Pope’s Institute as an architectural analyst and epigrapher (fig. 139).173 During the trip, the Cromwells meet with Iranian government officials and dealers and are recognized as potential customers and patrons (fig. 140).

In Esfahan, the Cromwells document some Safavid mosques and palaces for purposes of inspiration, creative quotation, and close replication back at Shangri La. They also meet Pope’s Iranian colleague Ayoub Rabenou (d. 1984), a dealer working between Iran and Paris, and enlist him to oversee the production of extensive custom-made tilework for Shangri La. This tilework is produced in two techniques—haft rangi (seven colors) and moʿarraq (mosaic)—by a workshop in Esfahan (fig. 141).174

1938–39: Honolulu, Territory of Hawai‘i

Construction of Shangri La is largely complete, and Duke avidly acquires materials to fill her home (figs. 142–143). While waiting for the custom tilework from Iran, she also purchases examples of historical Persian art from Rabenou and other dealers like New York-based Hassan Khan Monif (d. 1968). Some of Duke’s purchases are negotiated by Mary Crane, who emerges as a trusted advisor-agent and skillfully leverages her presence in New York, annual fieldwork in Iran, and connections with curators like Maurice Dimand (Metropolitan) and individuals like Arthur Upham Pope. Crane provides a variety of services to Duke, including organizing treatments on collections in New York, guiding the integration of Persian architectural forms and designs into Shangri La, providing opinions on artworks, and going to sales and shops to search for acquisitions. The similarly aged young women also develop a friendship.

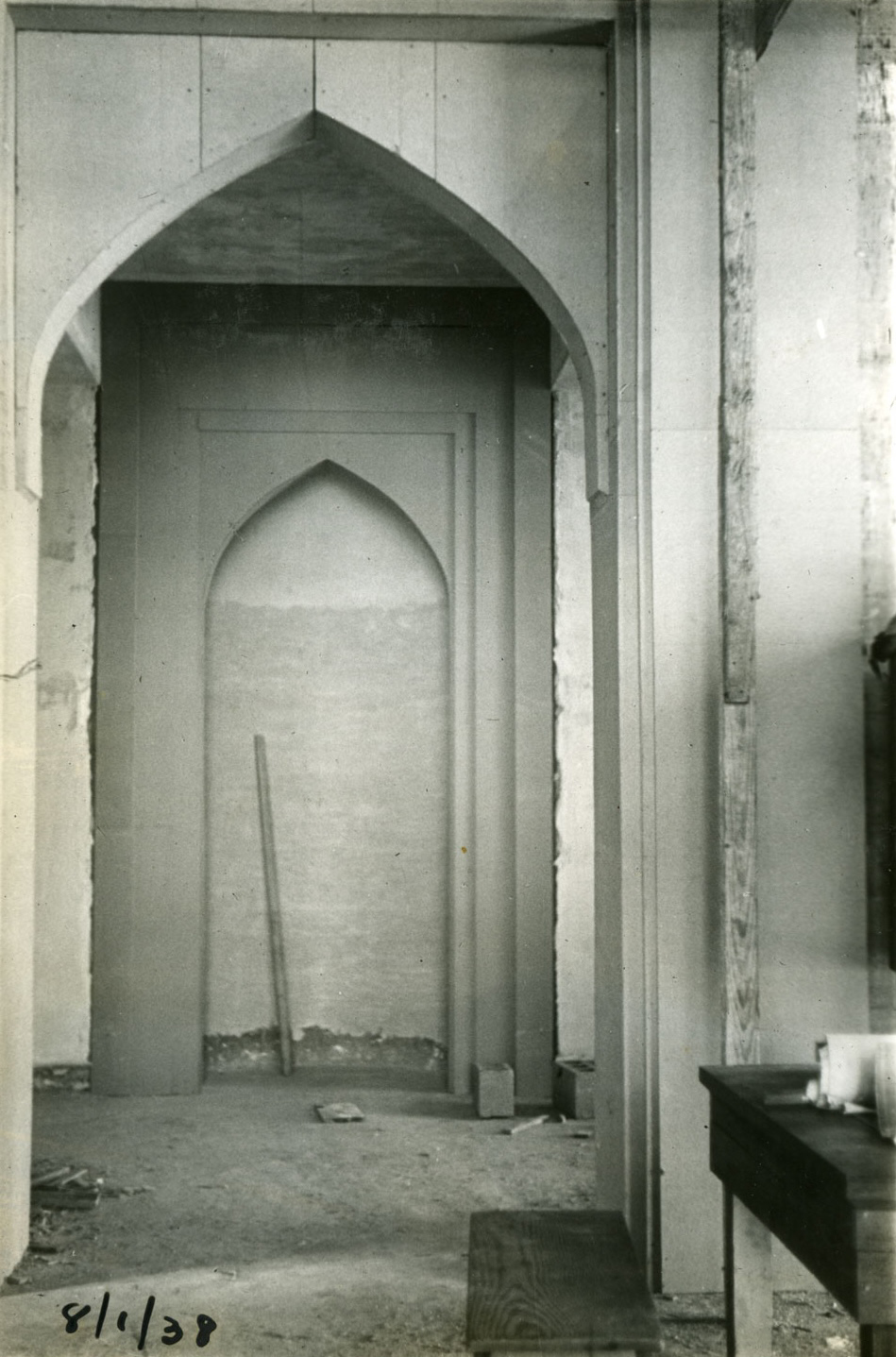

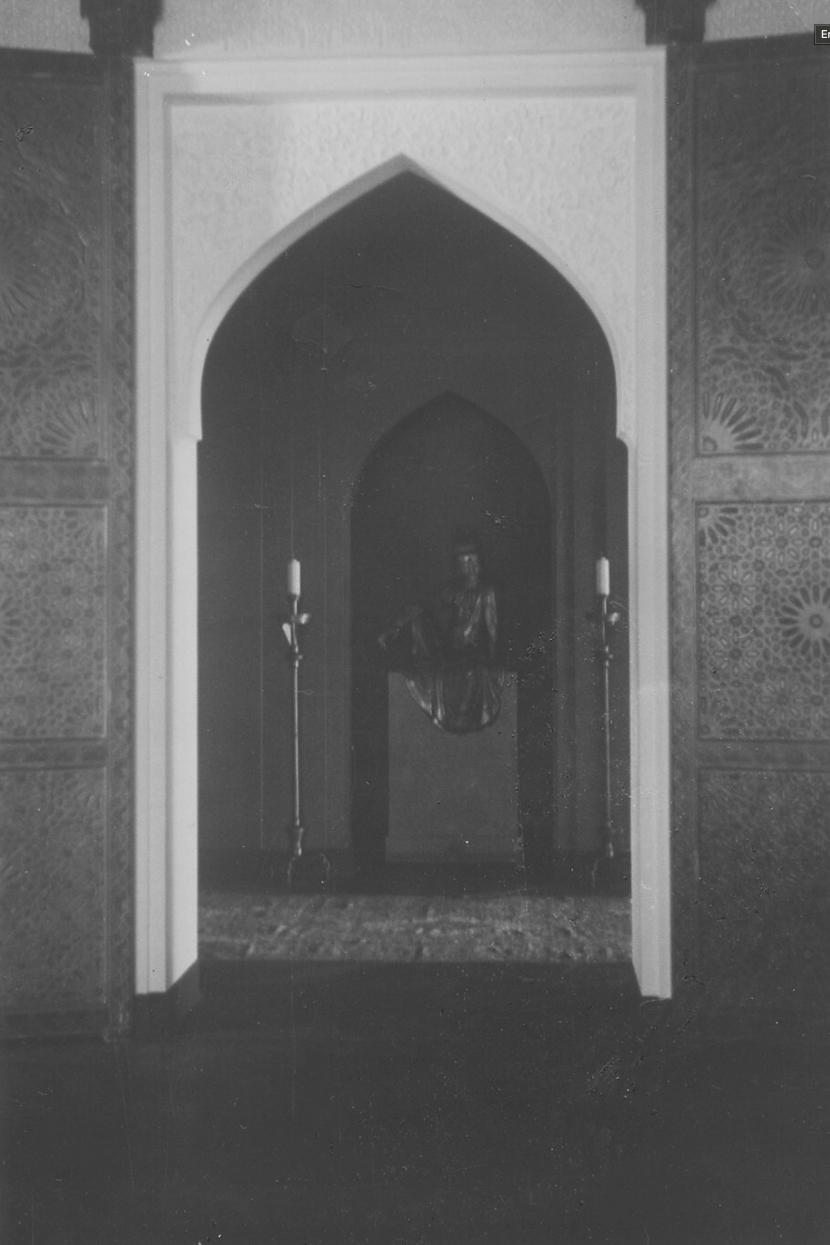

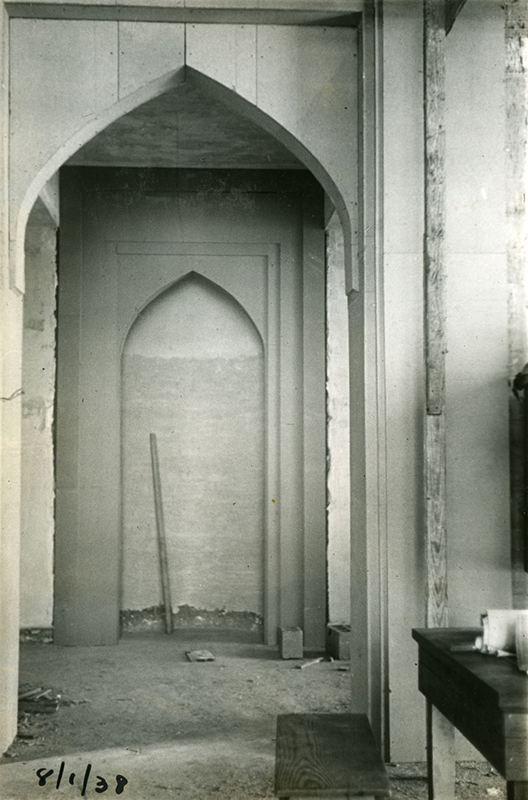

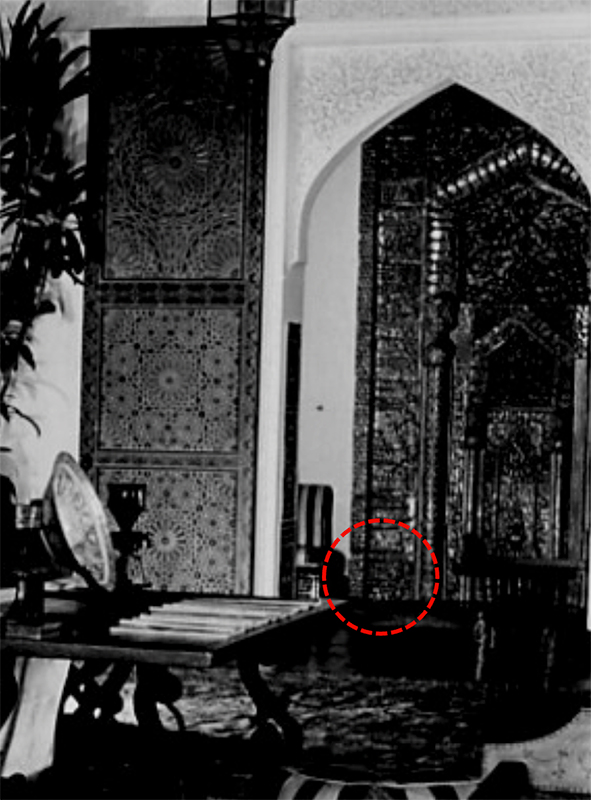

Within the main house, Duke concentrates many of her displays in the living room and adjacent areas, and the wall of the small room facing onto the living room is identified as the optimal space to display a significant artwork (fig. 144). By August 1938, this wall is filled with a shallow niche with a pointed arch set in a frame (fig. 145).175 Duke’s most prized possession at the time—a late fourteenth–fifteenth century Guanyin Bodhisattva purchased in Paris in 1937—is soon placed on a pedestal in this niche, and the arched threshold to the living room is ornamented with a stucco spandrel framed by a pair of wooden doors, both custom-made in Morocco in 1937 (fig. 146). The space becomes known as the ‘Kwan-yin Room,’ and the Guanyin is flanked on either side by candles.

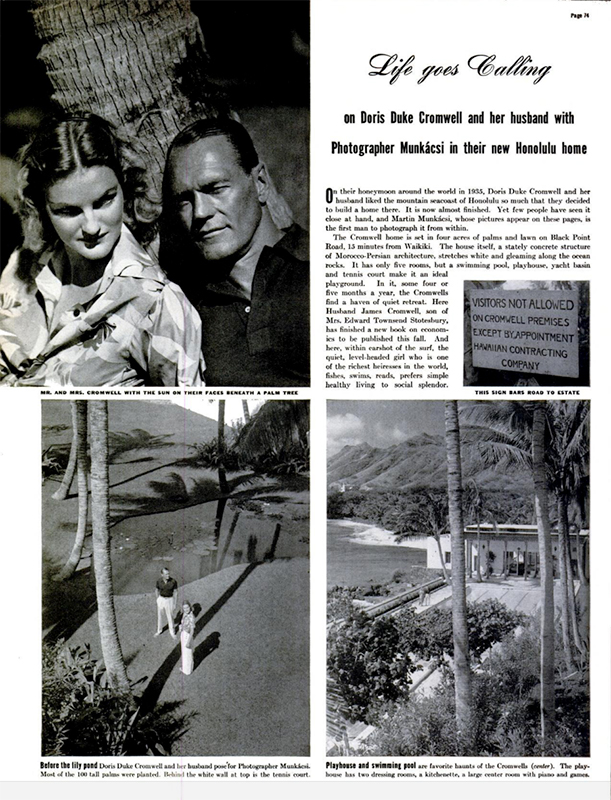

Once construction is relatively complete, the Cromwells invite Martin Munkácsi to photograph the property, and an article is soon published in Life magazine. (figs. 147–148).176 This is the first time that the house is seen by the American public and its name publicized as “Shangri-la.” The published photographs include some general views of the property, posed images of Duke and her husband, and a few more casual photographs with local friends like Johnny Gomez and some of the Kahanamoku brothers, a renowned Hawai‘ian family of distinguished watermen, including legendary surfer and Olympic swimmer Duke Kahanamoku (d. 1968). The article emphasizes that Duke “finds publicity distasteful, prefers quiet living,” hence her decision to build a house on an island far from the mainland United States.177 During these early days at Shangri La, Duke’s budding art collection remains quietly tucked away, and the property is an idyllic playground for Duke and her friends to sunbathe, picnic, swim, fish, surf, pose for photographs, and play with her animals (monkeys, cats, dogs, birds).178

1938–39: London and Leningrad (St. Petersburg)

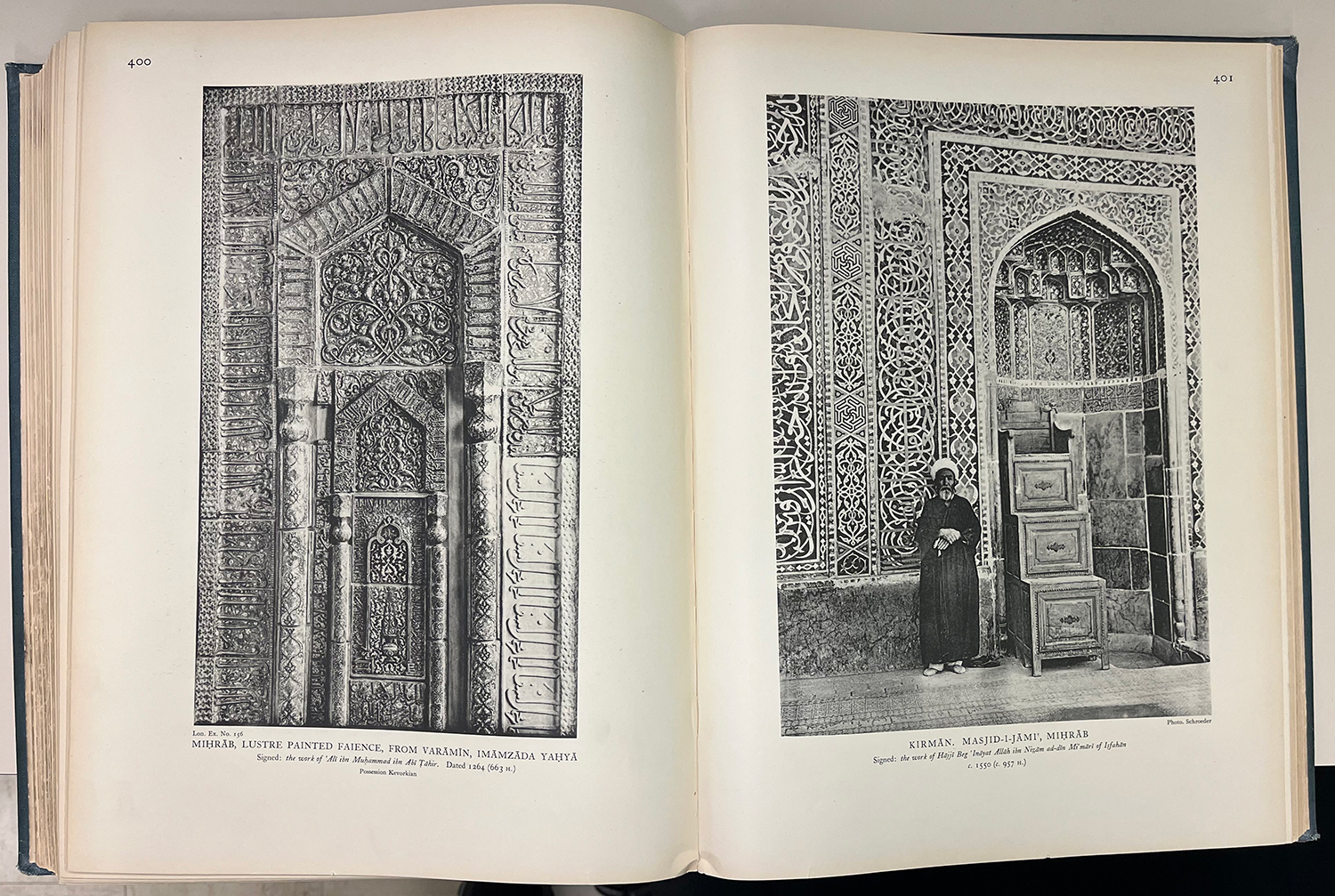

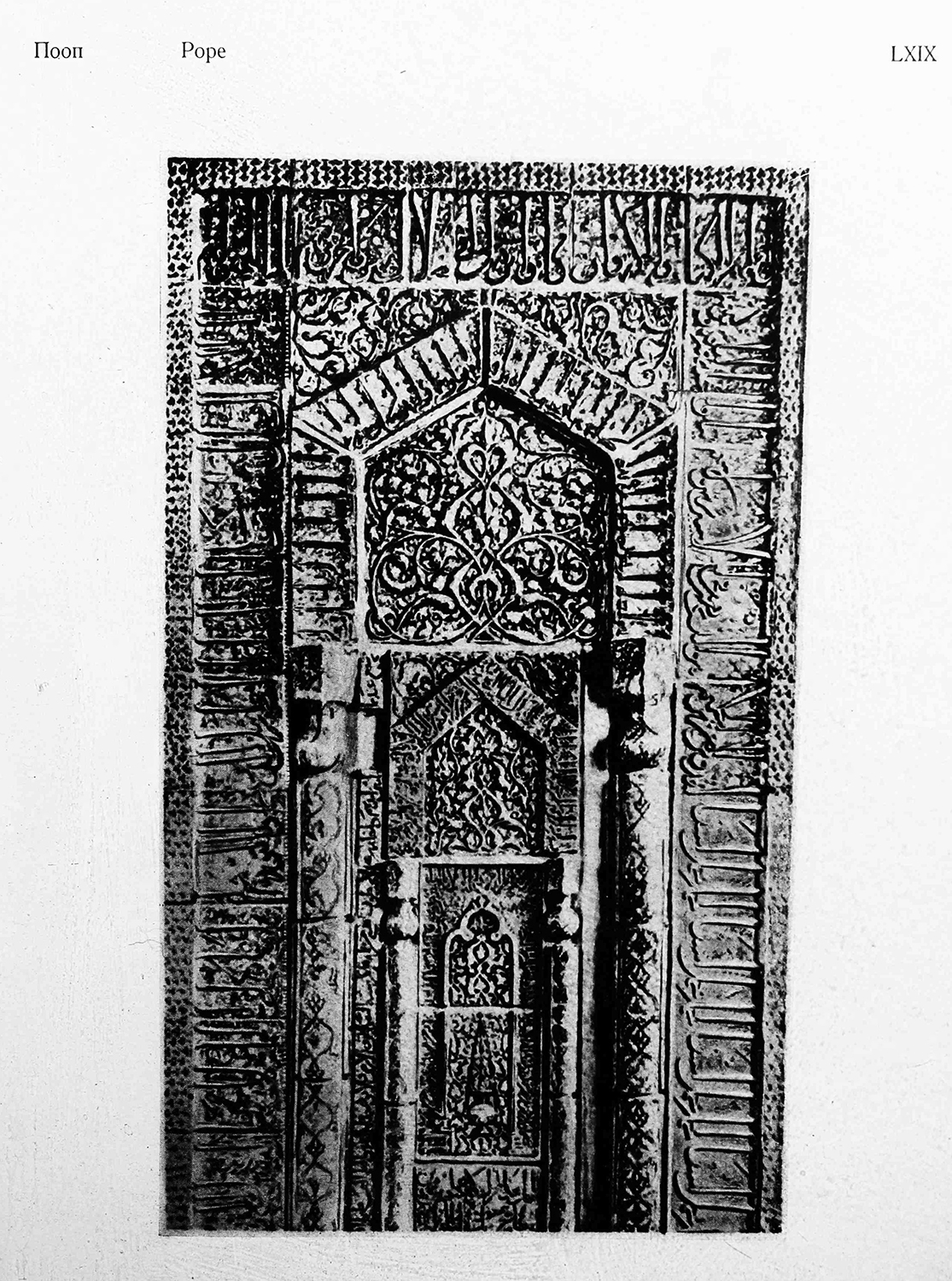

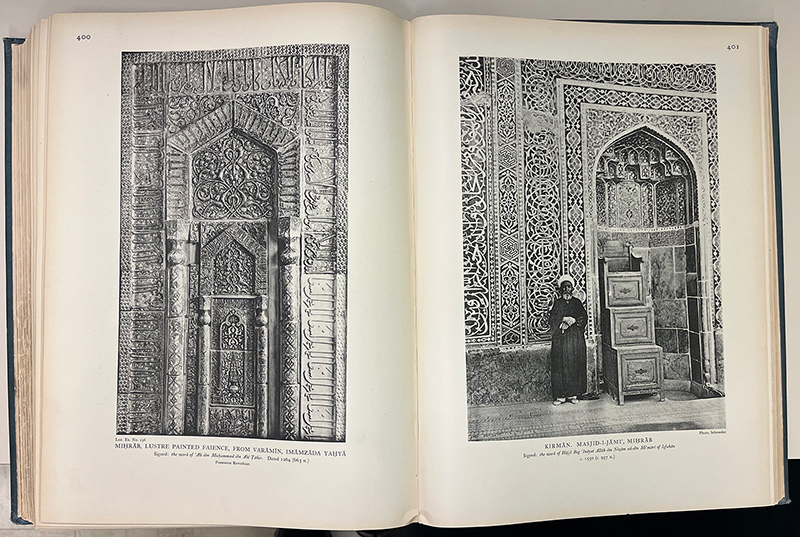

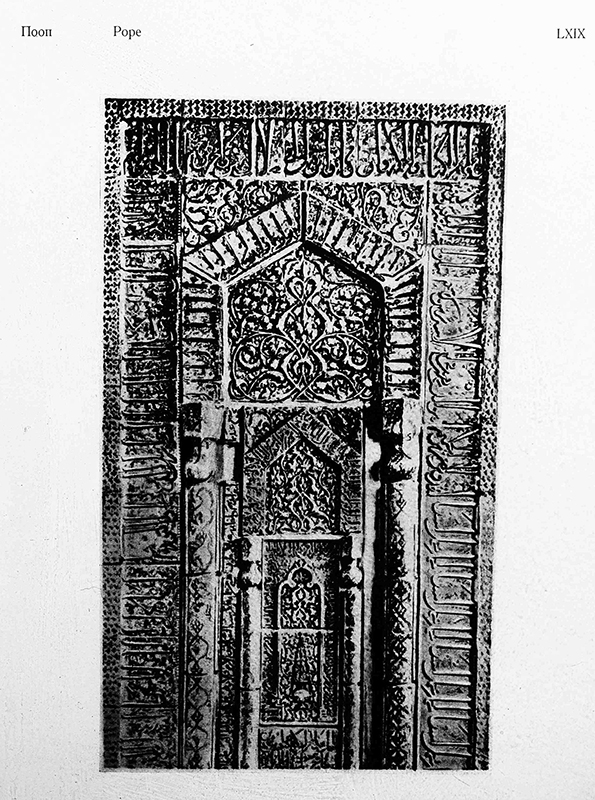

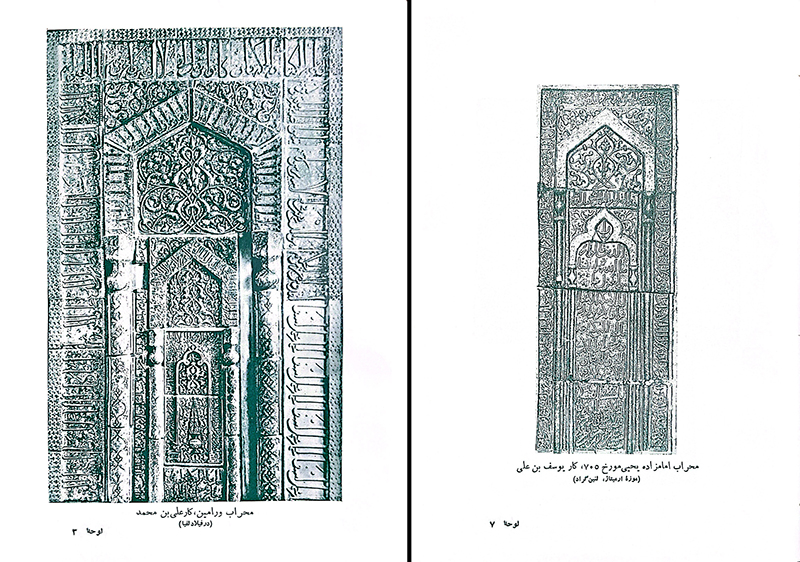

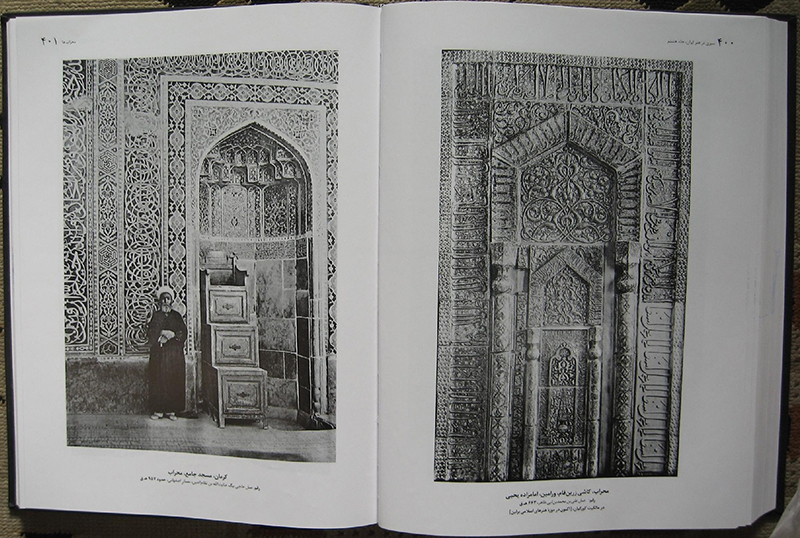

The mihrab is reproduced in the six-volume A Survey of Persian Art, edited by Arthur Upham Pope and his wife American art historian Phyllis Ackerman (d. 1977), using the 1918 photograph taken in the Penn Museum (fig. 149).179 It is listed as “Possession Kevorkian” and properly identified as from “Varāmīn, Imāmzāda Yahya.” Pope, who had organized the 1931 London exhibition, praises the mihrab in his typically florid prose: “The most elaborate work ever undertaken by Western potters is child’s play compared to one of these splendid structures, and it is doubtful whether even the great porcelain pagodas of China were more difficult to execute.”180 Pope seeks to convey the sensorial effect of the mihrab in its original religious context, albeit with considerable hyperbole: “Nothing more effective could be devised for inducing religious ecstasy: the clear, high-keyed tones and the bewildering complexity of dancing lights, the sacred message shining through the maze in stately letters, the whole enveloped in a shimmering flame, a light from another world; this formed a fitting portal to the Divine Presence.”181 While Pope mentions the correct date of the mihrab, he questions if the panel with the date and signature actually belongs to the ensemble (recall the same questioning in 1931).

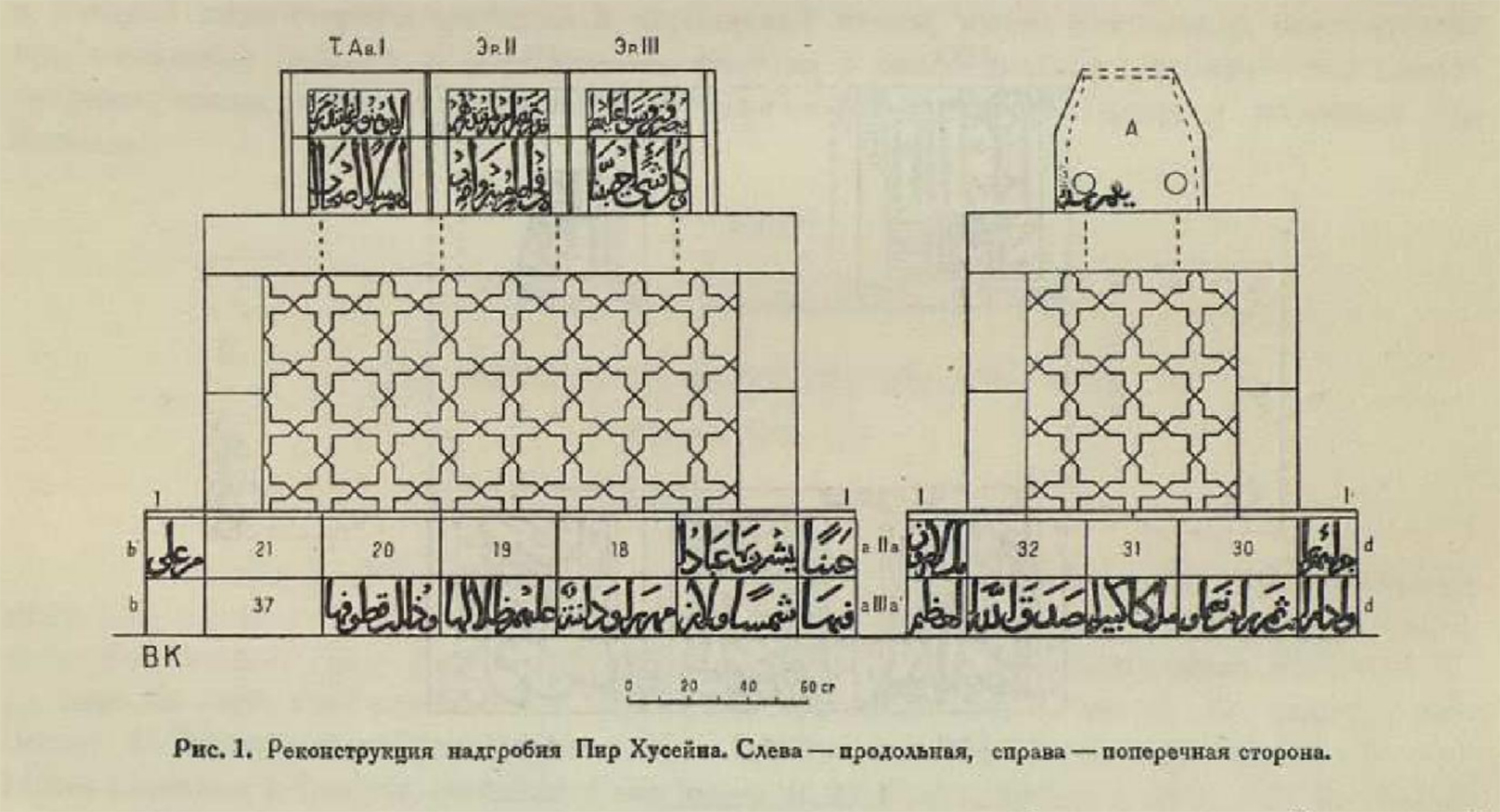

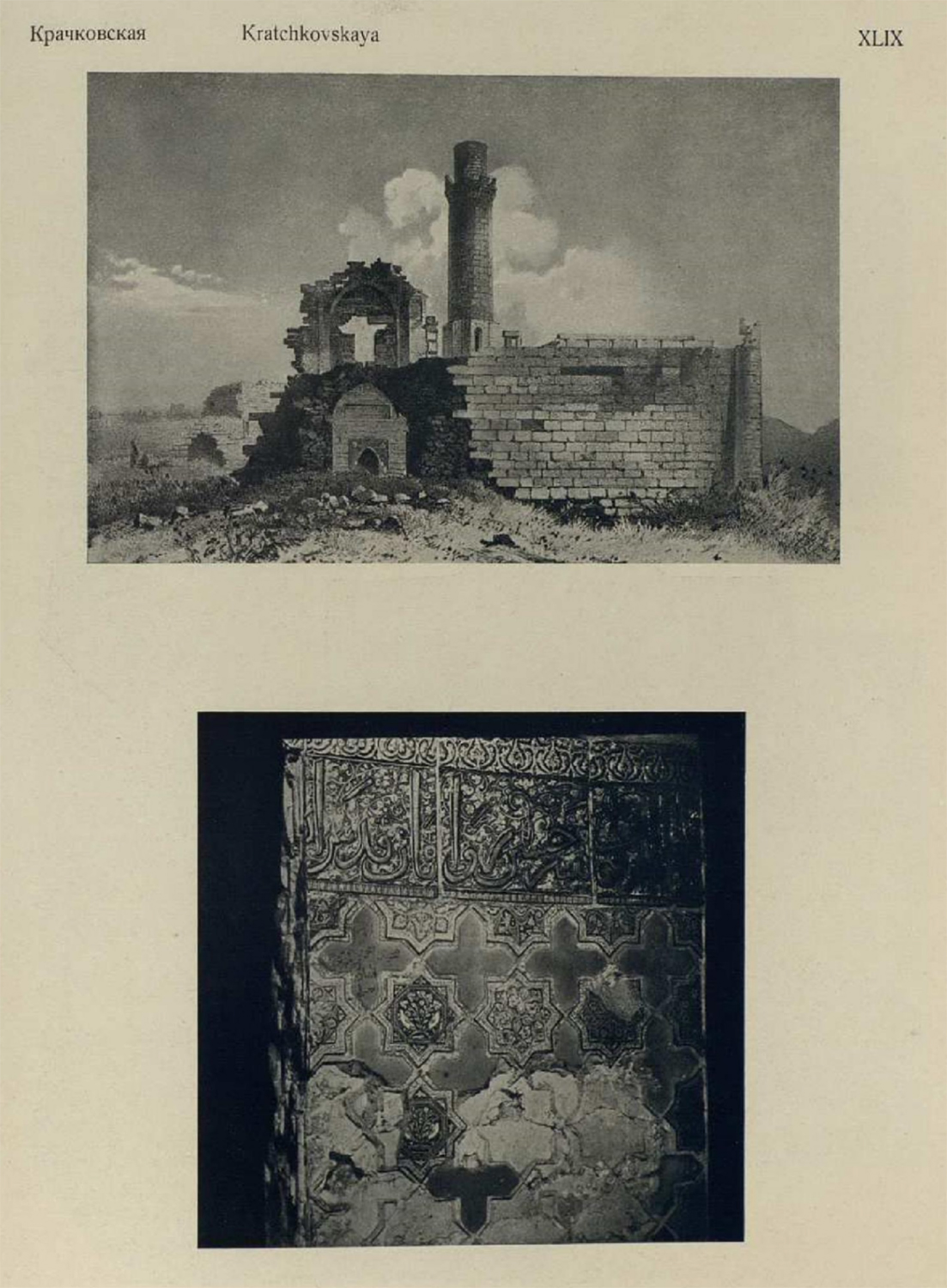

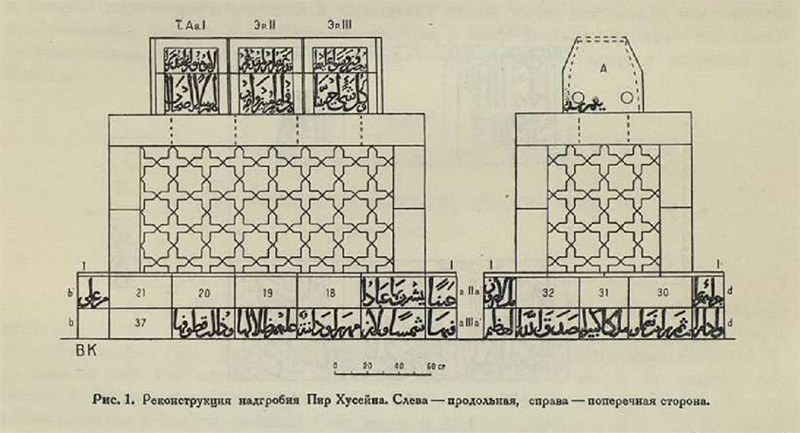

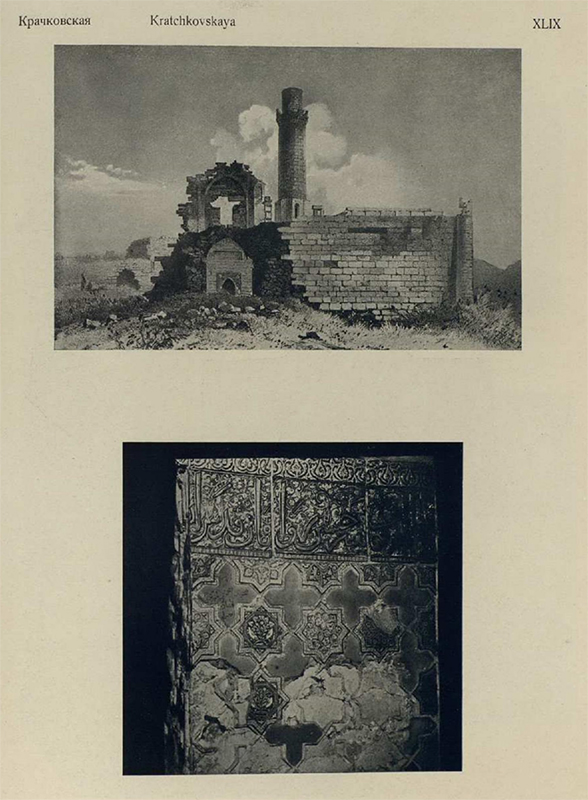

The Survey is soon followed by the trilingual proceedings of the Third International Congress held in Leningrad in September 1935. Vera Kratchkovskaya publishes her work on the Shrine of Pir Hosayn in Russian, and her essay includes her reconstructions of parts of the cenotaph (fig. 150), the 1861 print of the site that had been displayed in the Hermitage in 1935–36 (see fig. 135), and a photograph of some luster tiles in situ in the small tomb chamber (fig. 151).182

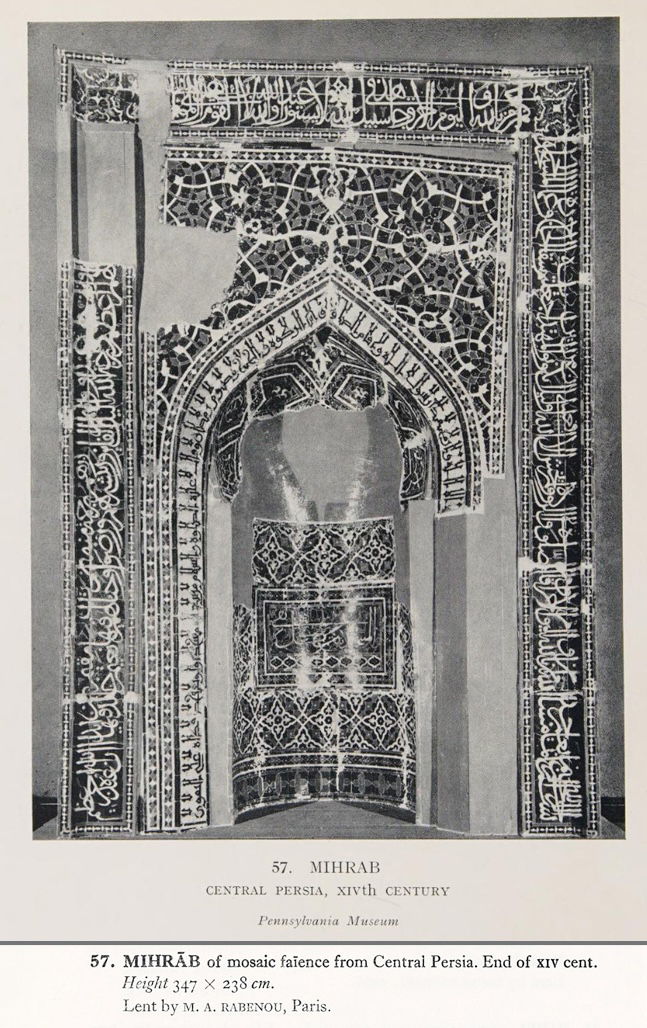

The proceedings includes several other articles on luster pottery and tilework. Iranian art historian Mehdi Bahrami considers luster tiles attributed to the Emamzadeh Jaʿfar in Damghan (in French) and German art historian Richard Ettinghausen explores the Kashan style in pottery (in English). In his essay on “medieval Iranian faience”—a condensed version of his more comprehensive chapter in the Survey—Pope highlights stylistic similarities between a luster tabourette in the Philadelphia Museum of Art (1943-41-1) and the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab as evidence that luster vessels and tiles were both produced in Kashan. He again reproduces the 1918 photograph of the mihrab (fig. 152).

Spring 1939: Iran

The American Institute of Persian Art and Archaeology conducts its fifteenth architectural survey in Iran. Pope describes the expedition as the “the largest yet sent out by the Institute, by far the best equipped, the most costly, and cover[ing] more ground than any other save that of 1938.”183 The five-person team is led by American art historian and expedition director Donald Newton Wilber (d. 1997) and includes Mary Crane as its architectural analyst and epigrapher (fig. 153).184 The expedition visits many sites and cities associated with medieval Persian luster tilework, including the tomb of Oljaytu in Soltaniyeh (map), the city of Kashan, the Shrine of Shaykh ʿAbd al-Samad in Natanz (map), the many tombs in Qom, and Pir-e Bakran near Esfahan (map). In Kashan, Wilber gathers sherds and wasters proving, in Pope’s words, that “in mediaeval ceramics the supremacy lay with Kashan.”185

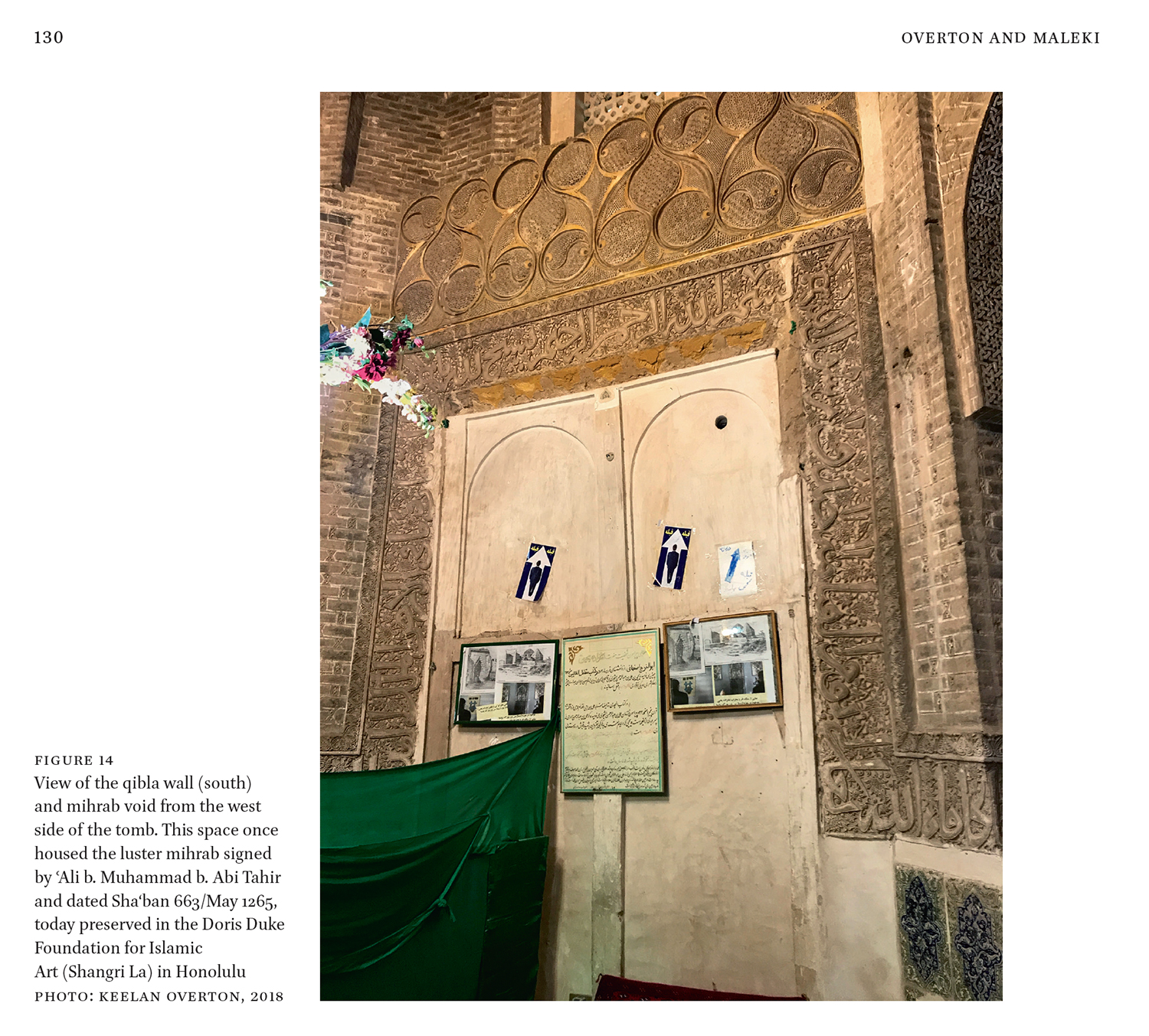

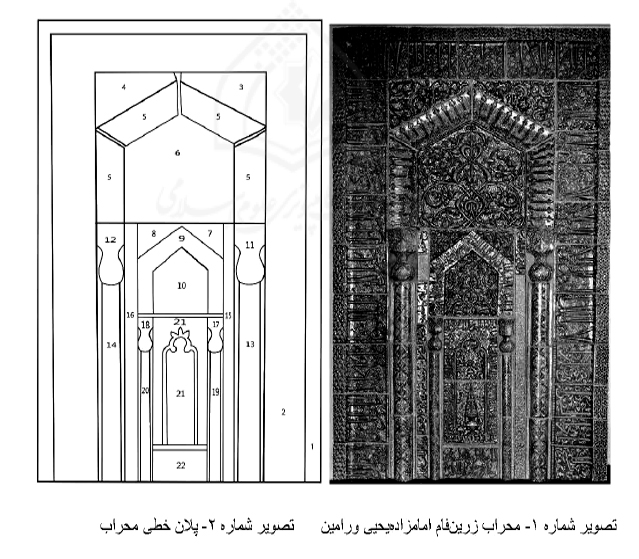

In May, Wilber visits several sites in Varamin, including the Emamzadeh Yahya (fig. 154). He surveys the shrine and takes photographs and measurements, including of the mihrab void. His research is not published for another sixteen years (jump ahead to 1955), and in the meantime, the mihrab remains conceptually isolated from its original site in many academic circles.

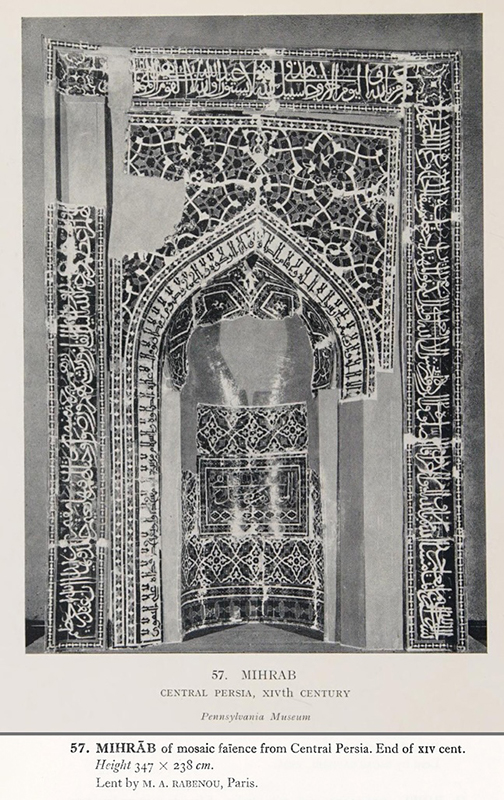

1939–40: New York

In June 1939, the Metropolitan Museum of Art acquires the mihrab made in the moʿarraq technique (monochrome-glazed tiles cut and arranged into a mosaic pattern) from the Madreseh-ye Emamiyeh (Emami or Baba Qasem, map) in Esfahan. According to the museum’s catalog and online record (39.20), dealer Ayoub Rabenou sold the mihrab to Arthur Upham Pope for the museum.186 The acquisition is heralded in the popular press as the “only one outside of Iran” and announced by curator Maurice Sven Dimand (d. 1986) in a short essay in the museum’s bulletin.187 The mihrab is quickly displayed in the museum next to examples of isolated luster tiles (fig. 155).

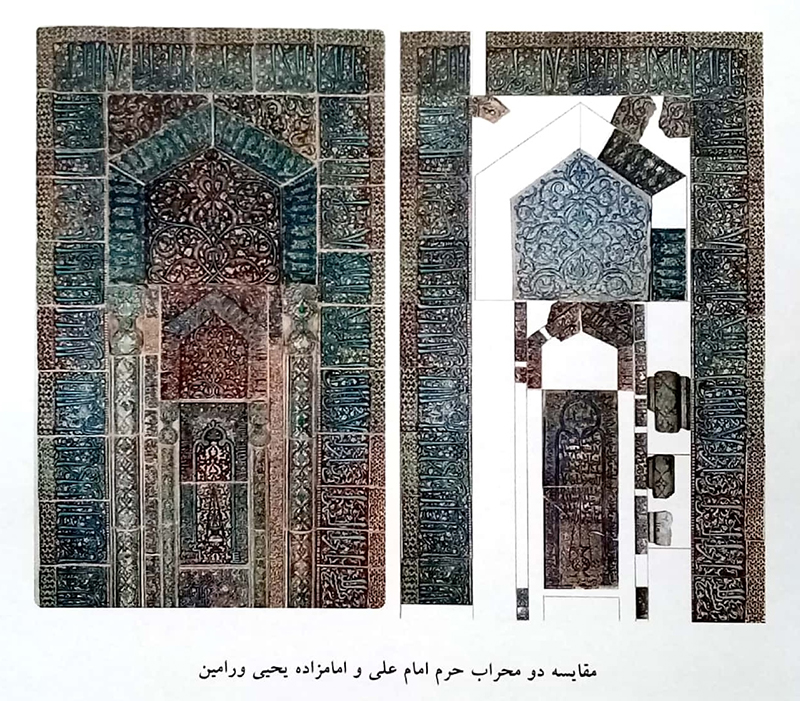

The Madreseh-ye Emamiyeh’s mihrab had a long history before entering the Metropolitan, and aspects of its historiography overlapped with the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab. A photograph taken of it in situ in the southern domed sanctuary of the madrasa reveals that much of its lower portion was missing (fig. 156).188 Like the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab, the Madreseh-ye Emamiyeh’s mihrab was a highlight of the 1931 International Exhibition of Persian Art in London, and the two mihrabs were in fact confused on the published gallery plan (see fig. 120, A and B). By the time of the London exhibition, some of the lower zone of the Madreseh-ye Emamiyeh mihrab had been restored, but new losses were also visible (fig. 157). In the accompanying catalogs, it was listed as lent by dealer Ayoub Rabenou and in the “Pennsylvania Museum.” This museum had displayed the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab on two occasions (1918, 1926), and it is possible that the two mihrabs were once again confused.189

In 1940, Mary Crane publishes an article on the Madreseh-ye Emamiyeh’s mihrab based on her fieldwork conducted at the madrasa in May 1939 as part of the American Institute’s architectural survey.190 Her study is a useful introduction to the madrasa and includes a plan, many photographs, a comparison of the dimensions of the qibla wall and the mihrab, and a reference to the in situ photograph (see fig. 156). Although Crane does not discuss when and how the mihrab was removed or reproduce an image of the void left behind, her article leaves little doubt about its original building.

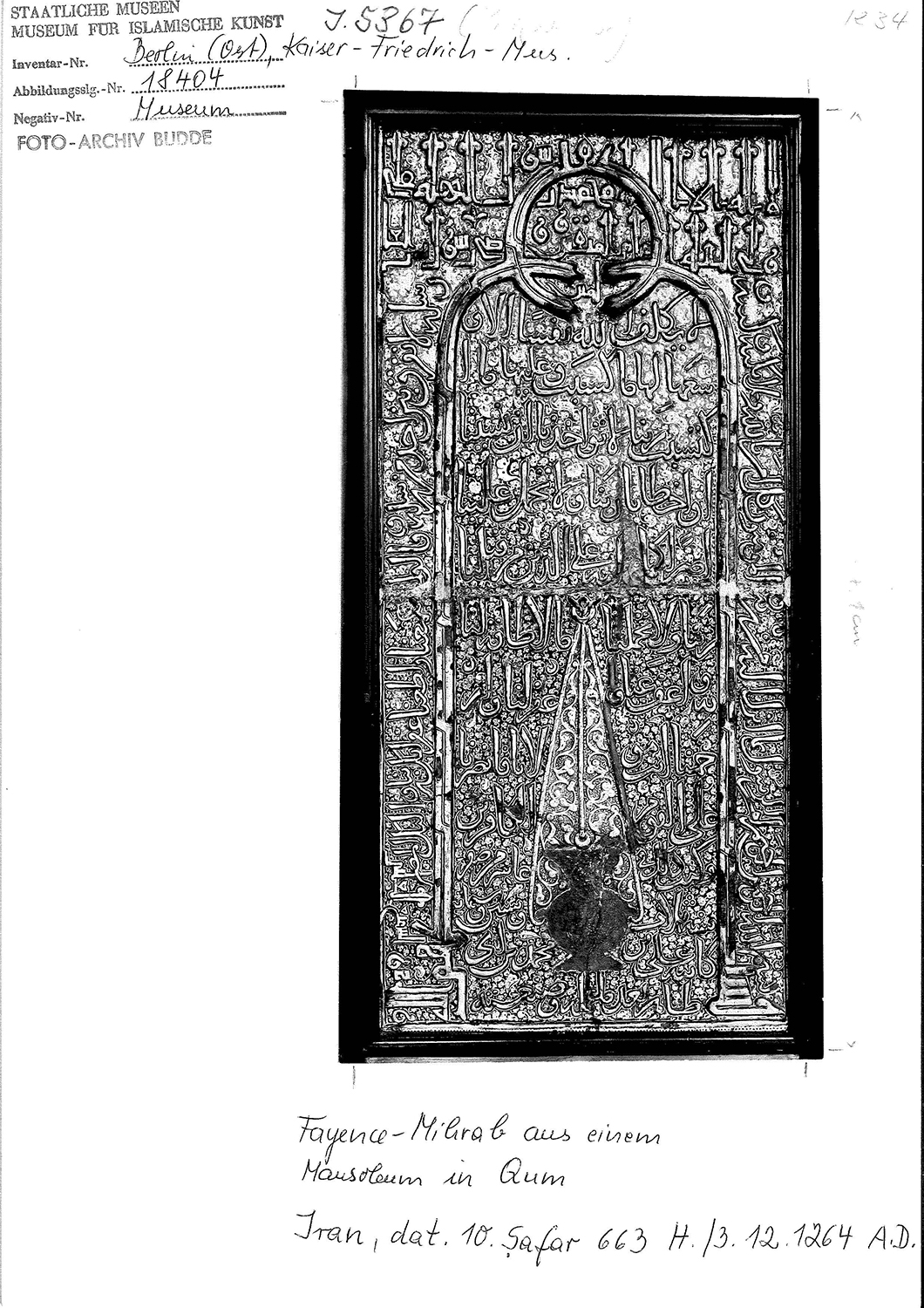

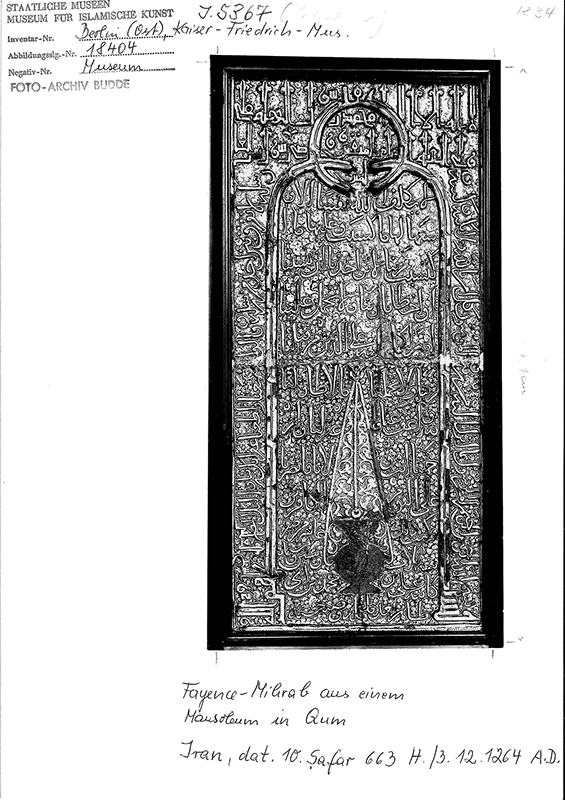

1 September 1939–2 September 1945: World War II

The outbreak of World War II disrupts the global economy and shifts investment priorities toward the war effort. The art market is destabilized, and European museums and collections face heightened risk of bombing, looting, and displacement. In 1945, the State Museums of Berlin are bombed, and its galleries of Islamic art are directly hit, including the Mshatta façade (fig. 158). Around three million ‘objects’ from collections in East Germany are taken to the Soviet Union as booty, one million of which are never returned. Among them is the two-tiled luster panel dated 663/1265 and signed by ʿAli b. Mohammad b. Abi Tahir, the same date and potter as the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab (fig. 159). This panel had been acquired in 1927 alongside the Masjed-e Meydan’s mihrab and accessioned as ‘I. 5367.’ Based on a historical account from 1270/1853–54, Hossein Modarressi proposed in 1976 that it was the cover of the cenotaph in the Emamzadeh Ahmad b. Qasem in Qom (map).191 The panel’s present whereabouts are unknown, but it is listed in the Lost Art Datenbank, Deutsches Zentrum Kulturgutverluste (Lost Art Database, German Lost Art Foundation), Lost Art-ID: 169834.192

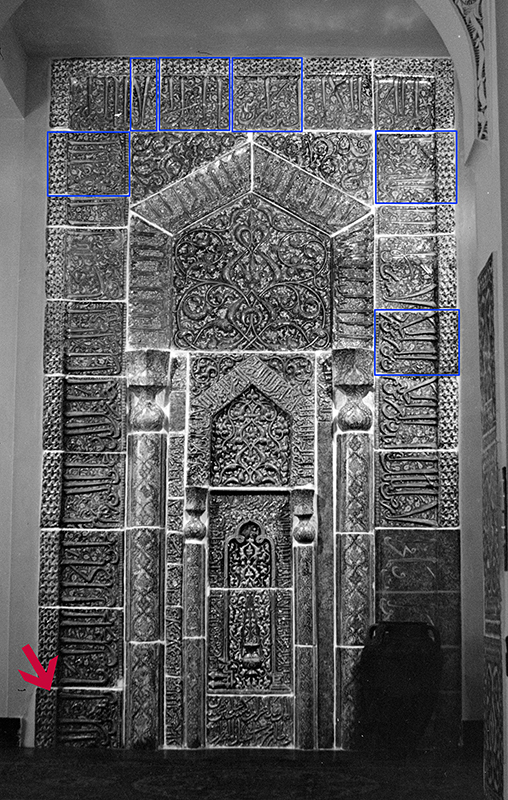

11 April 1940: Philadelphia

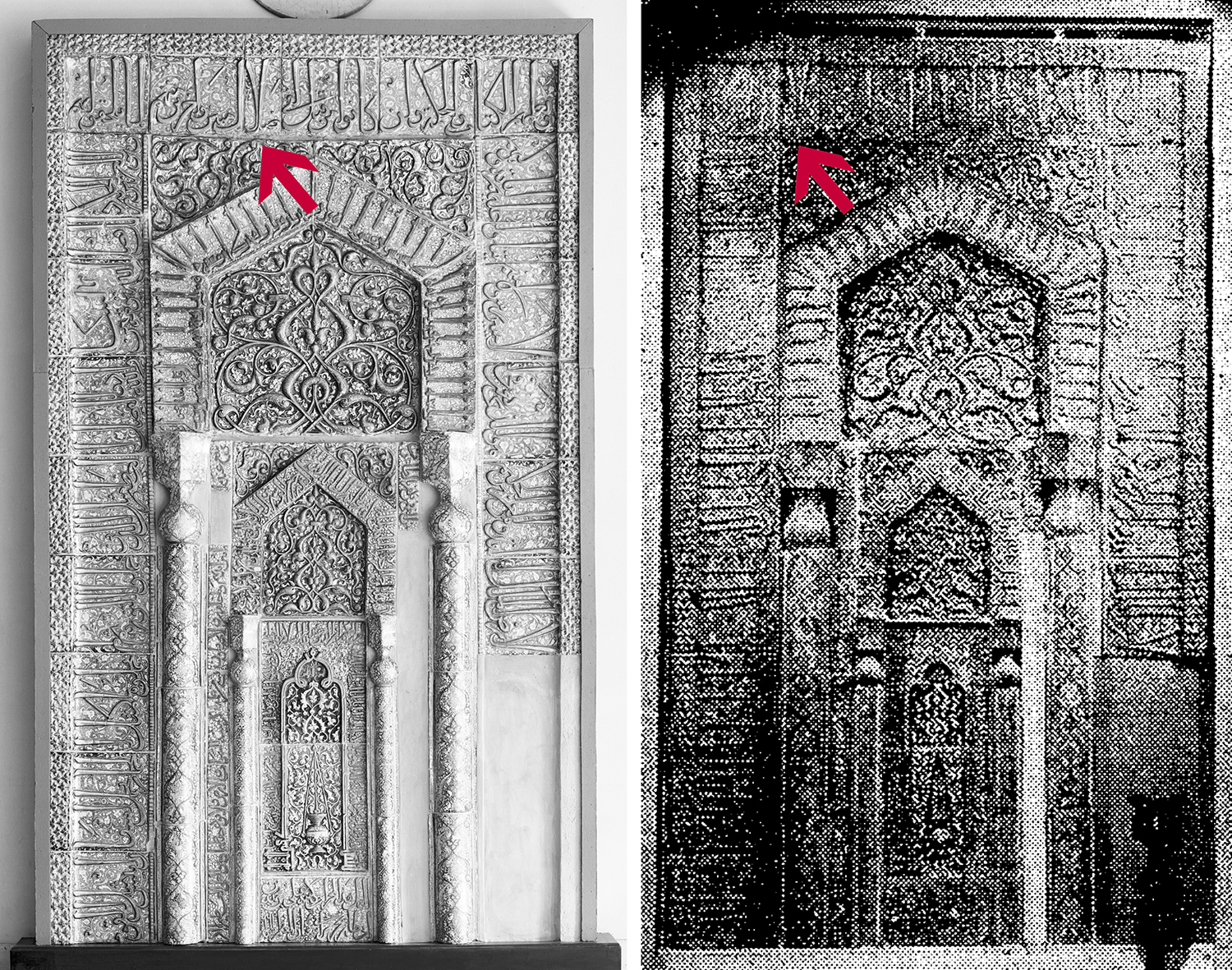

The mihrab is photographed for insurance purposes at the Penn Museum before being sent to New York for exhibition in “Six Thousand Years of Persian Art” (fig. 160). In this final iteration in Philadelphia, two major improvements are visible. The two tiles previously owned by Octave Homberg are reunited with the ensemble (see fig. 130), and the repetitive inscriptional filler on the lower right is gone and replaced with blank white plaster. After this gap, the first five verses of sura al-Jumuʿah unfold in their correct order, ending at القوم in the middle of the fifth verse.193

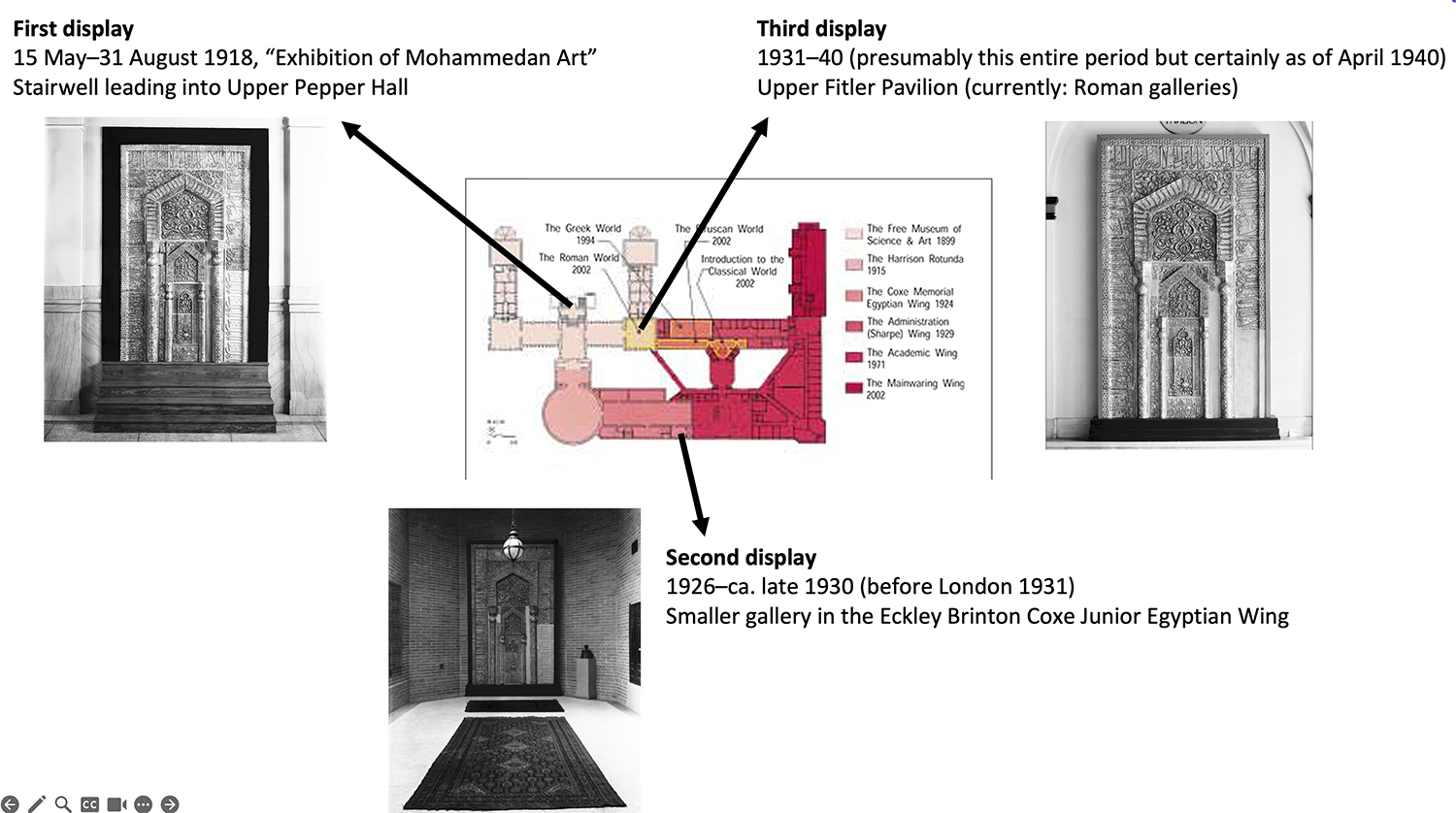

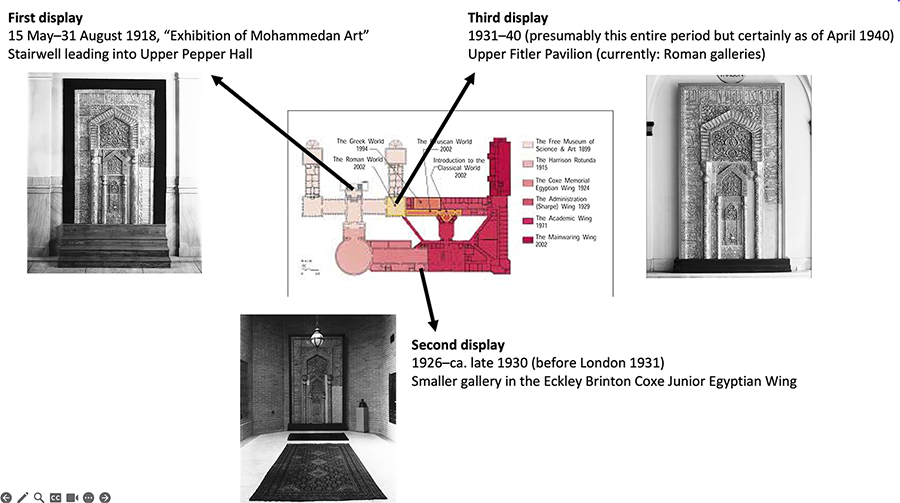

Between 1918 and 1940, the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab was installed in at least three distinct contexts in the Penn Museum: the temporary “Exhibition of Muhammadan Art” (1918), a small gallery in the new Coxe Memorial Egyptian Wing (1926–late 1930; then to London in 1931), and the Upper Fitler Pavilion (from May 1931) (fig. 161). These three installations over twenty-two years underscore the Penn Museum’s longstanding commitment to the mihrab’s display and its mobility within a single building.

24 April–1 July 1940: New York

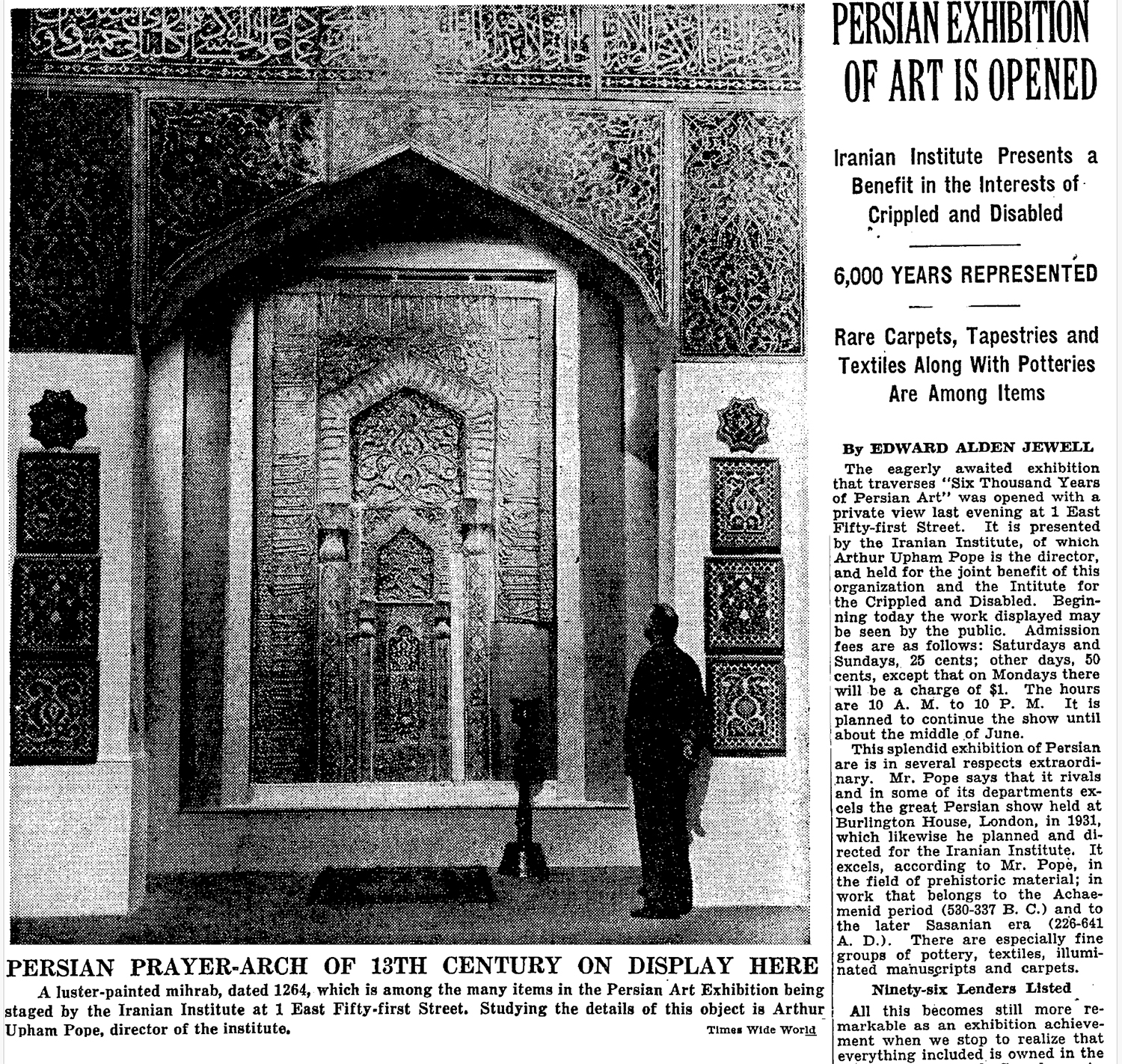

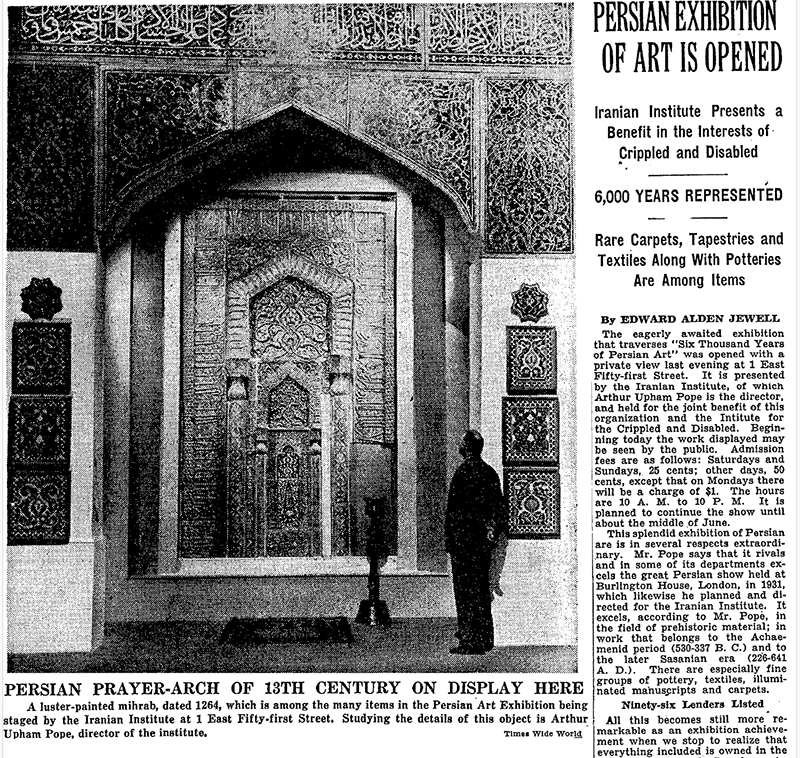

The Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab is displayed for a second time in New York (see 1914), in “Six Thousand Years of Persian Art,” another major exhibition organized by Arthur Upham Pope and the American Institute of Iranian Art and Archaeology.194 The exhibition is held in the now demolished old Union Club Building at Fifth Avenue and Fifty-First Street, and a photograph of Pope gazing at the mihrab is reproduced in a review in The New York Times (fig. 162).

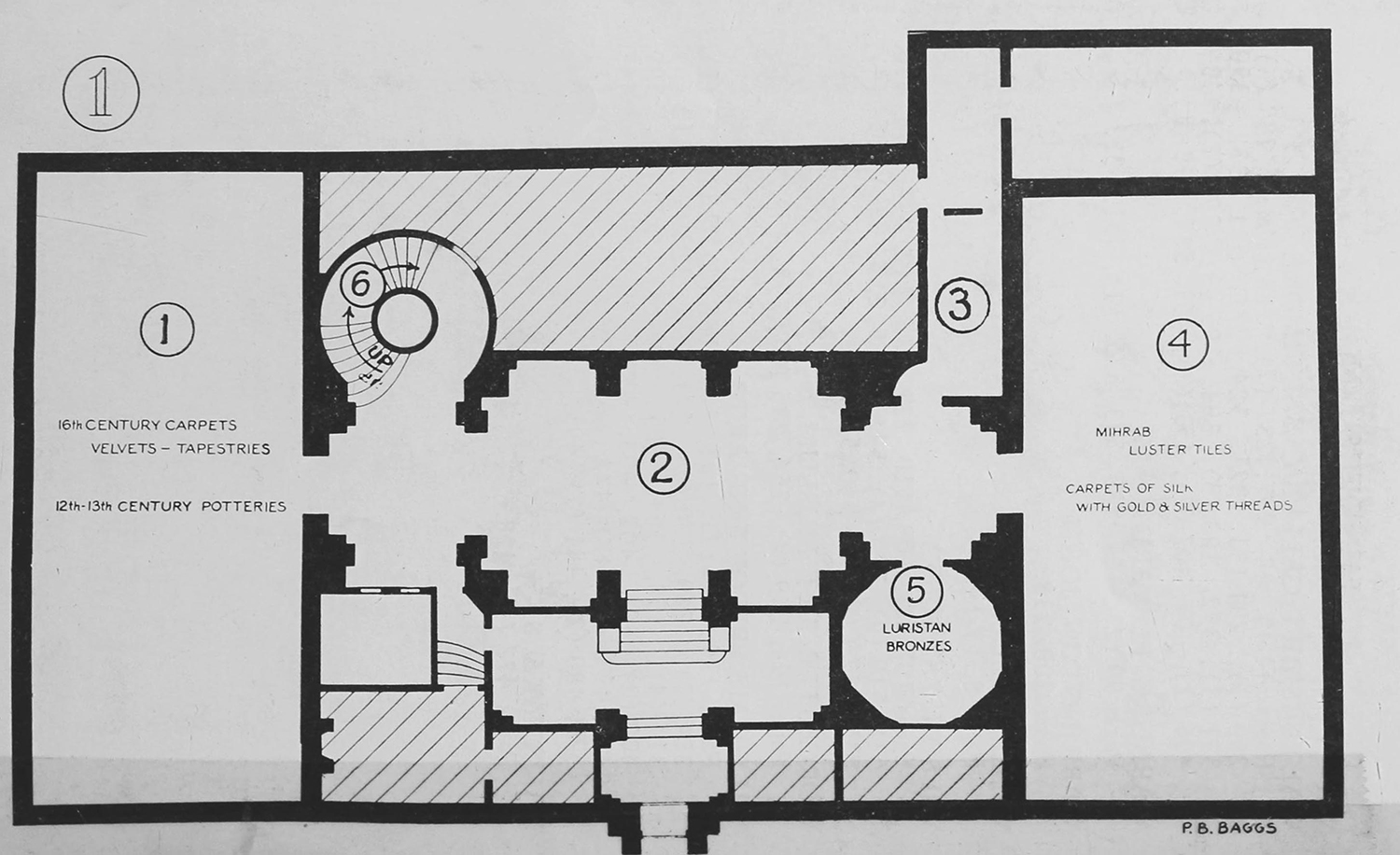

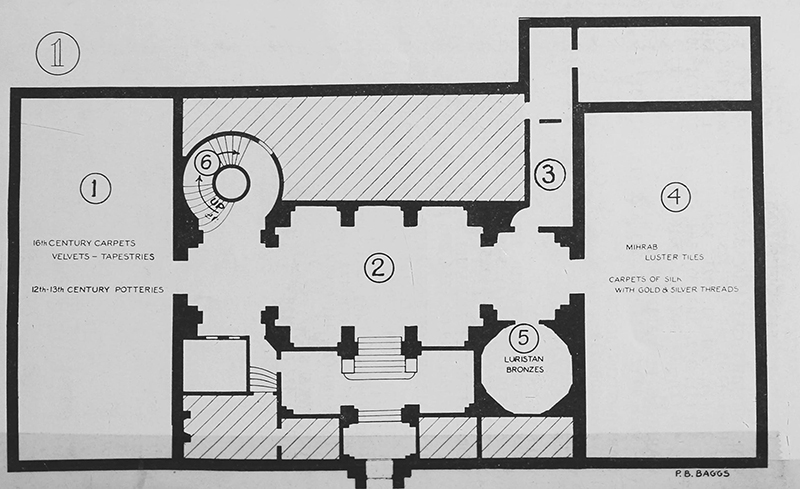

The mihrab is singled out on the published exhibition plan and displayed in one of the large galleries (fig. 163). It is slightly elevated and set behind a large arch with a tiled spandrel and inscription dated 885/1482, both in the moʿarraq technique. A tall bronze candlestick is placed in front of the mihrab’s missing tiles on the lower right, and a prayer carpet is set directly in front.195 This arrangement can be read as an attempt to evoke the original function of the mihrab and the atmosphere of a prayer space.

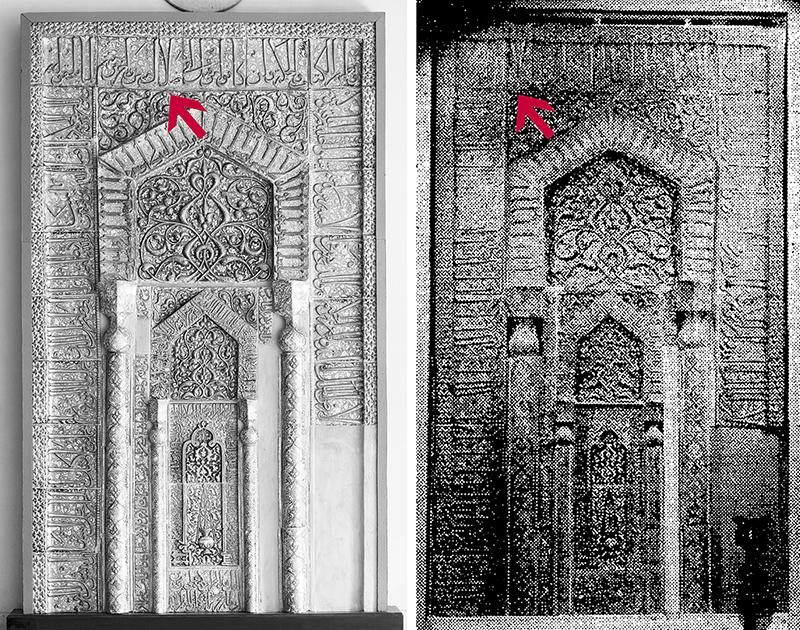

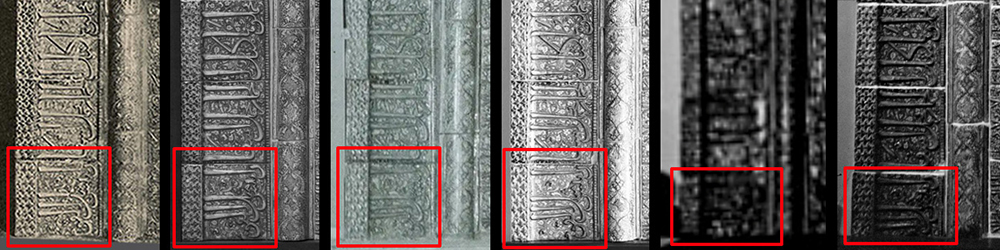

Some of the mihrab’s tiles are now out of place. One example is the thin tile with ضلا in the upper row of the outer border. Instead of being fourth from the right, it is fifth. This is an unfortunate error since the tile was correctly installed in Philadelphia just before the mihrab was sent to New York (fig. 164).

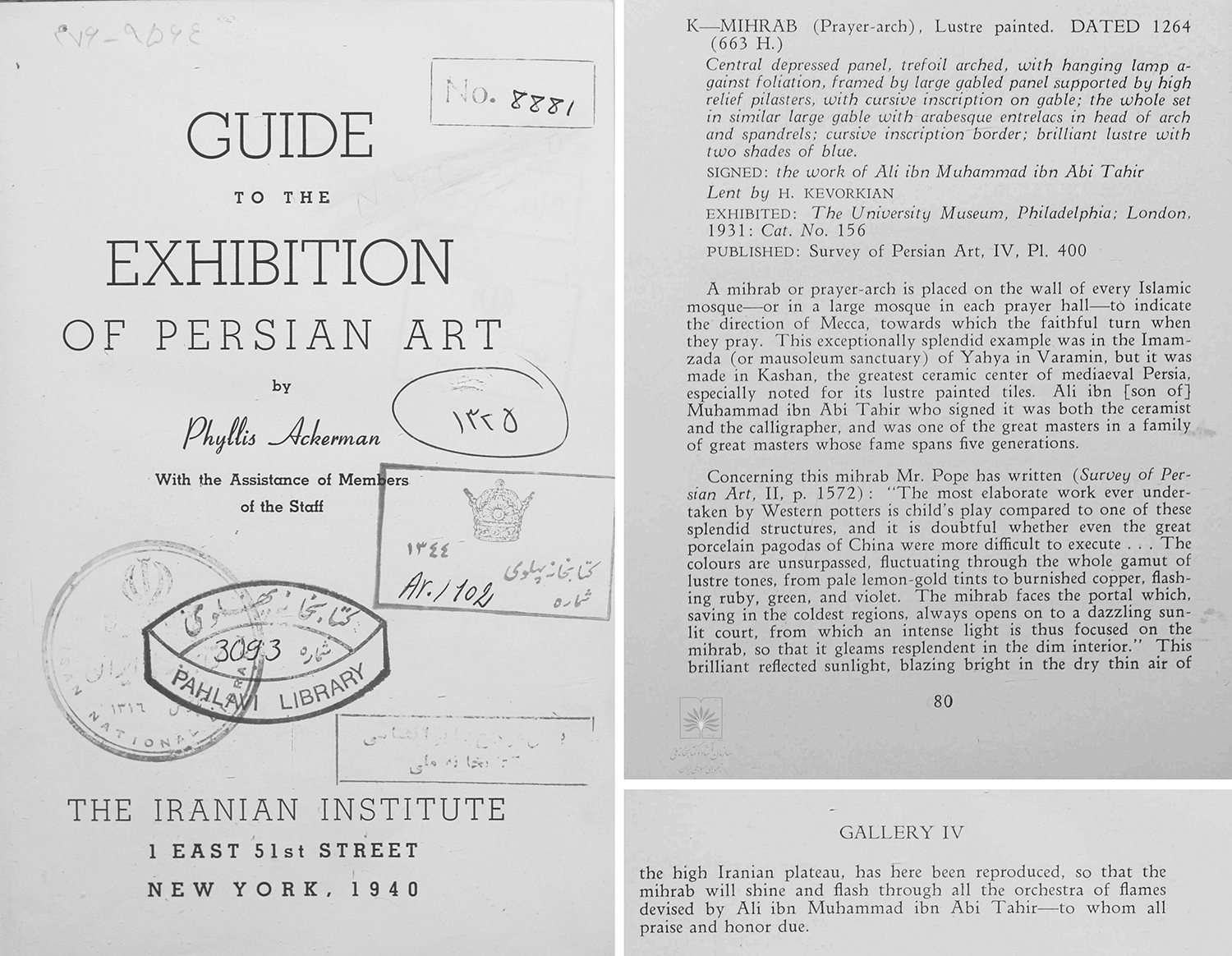

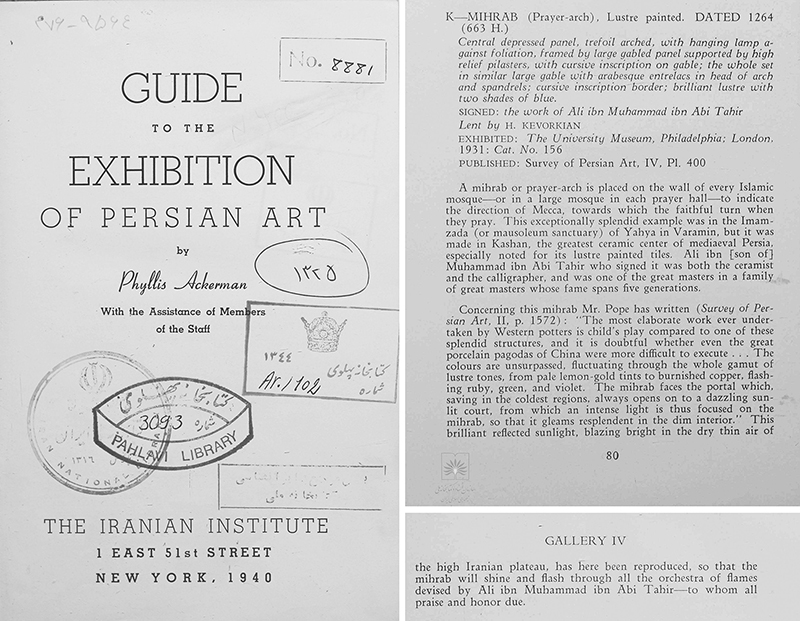

In the exhibition catalog, American art historian Phyllis Ackerman (d. 1977) writes an engaging entry on the mihrab that highlights its value as a potential acquisition for affluent visitors to the exhibition (fig. 165). Ackerman defines terms like mihrab and emamzadeh and mentions that the mihrab was located in the “Imamzada (or mausoleum sanctuary) of Yahya in Varamin.”196 She emphasizes the mihrab’s production in Kashan and introduces the potter as “one of the great masters from a family of great masters, whose fame spans five generations.” She also references Pope’s comments on the mihrab’s quality and aesthetic brilliance in A Survey of Persian Art and notes its previous exhibitions in Philadelphia and London, thus enhancing its value and prestige.

June 1940: New York and Honolulu

During the final weeks of the Persian art exhibition in New York, Doris Duke becomes interested in acquiring the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab.197 She does not communicate with Kevorkian directly but instead enlists Mary Crane, her preferred advisor on Persian art for the last two years. Crane is well positioned to mediate the sale given her connections in New York and work on the Madreseh-ye Emamiyeh’s mihrab recently acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

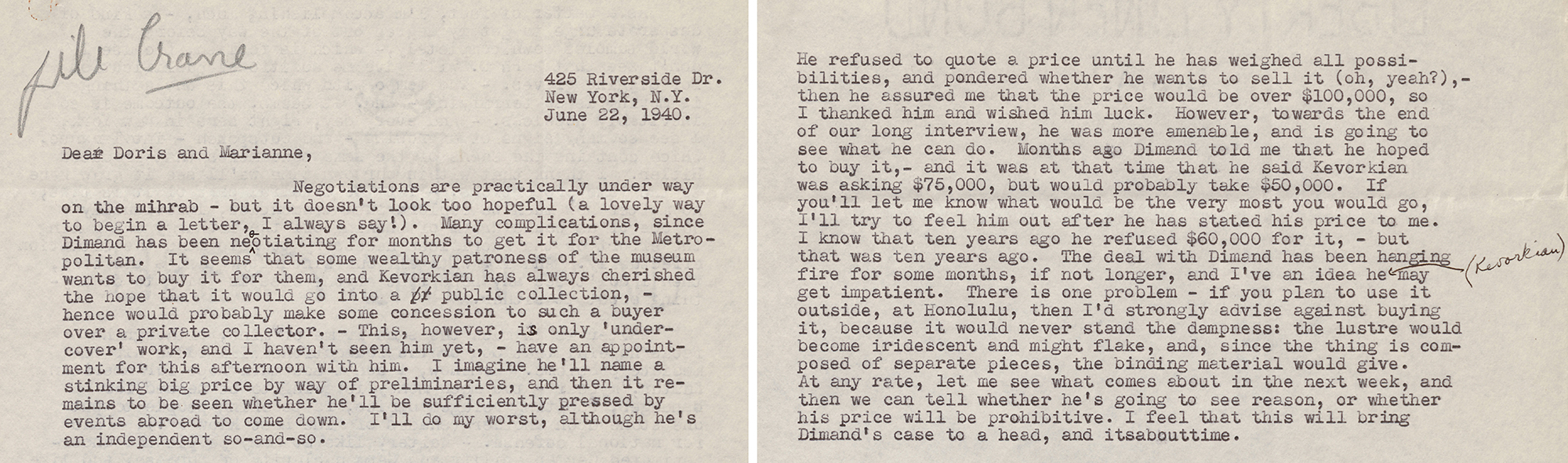

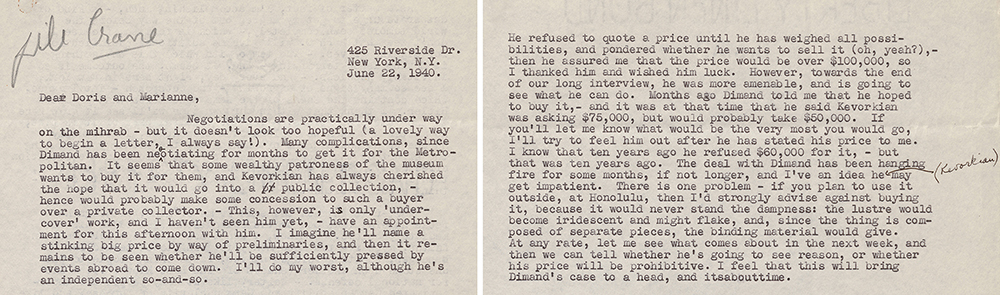

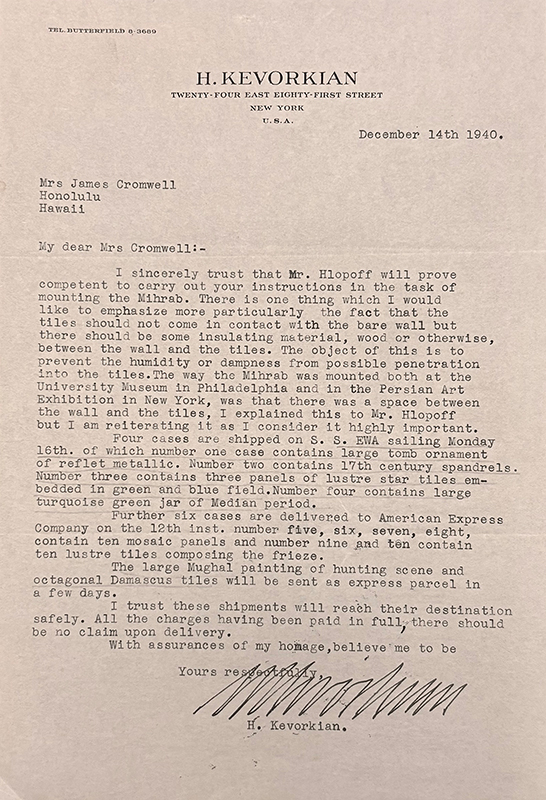

During the negotiations, Crane sends Duke and her secretary Marian Paschal detailed progress reports and letters.198 She initially reports that the acquisition does not look “too hopeful,” since Kevorkian had been negotiating for months with Maurice Dimand, curator at the Metropolitan, who was hoping that a patroness of the museum would assist with the acquisition (fig. 167). According to Crane, “Kevorkian has always cherished the hope that it would go into a public collection, hence would probably make some concession to such a buyer over a private collector.” At the end of the same long letter, after a long interview with Kevorkian, Crane writes that he refused to quote a price but that it would be over $100,000 (fig. 167, right). She references a range of prices learned through Dimand ($50,000–75,000) and asks Duke to let her know how much she is willing to pay. Crane senses that Kevorkian might be growing “impatient” with the prolonged negotiations with Dimand and the Metropolitan.

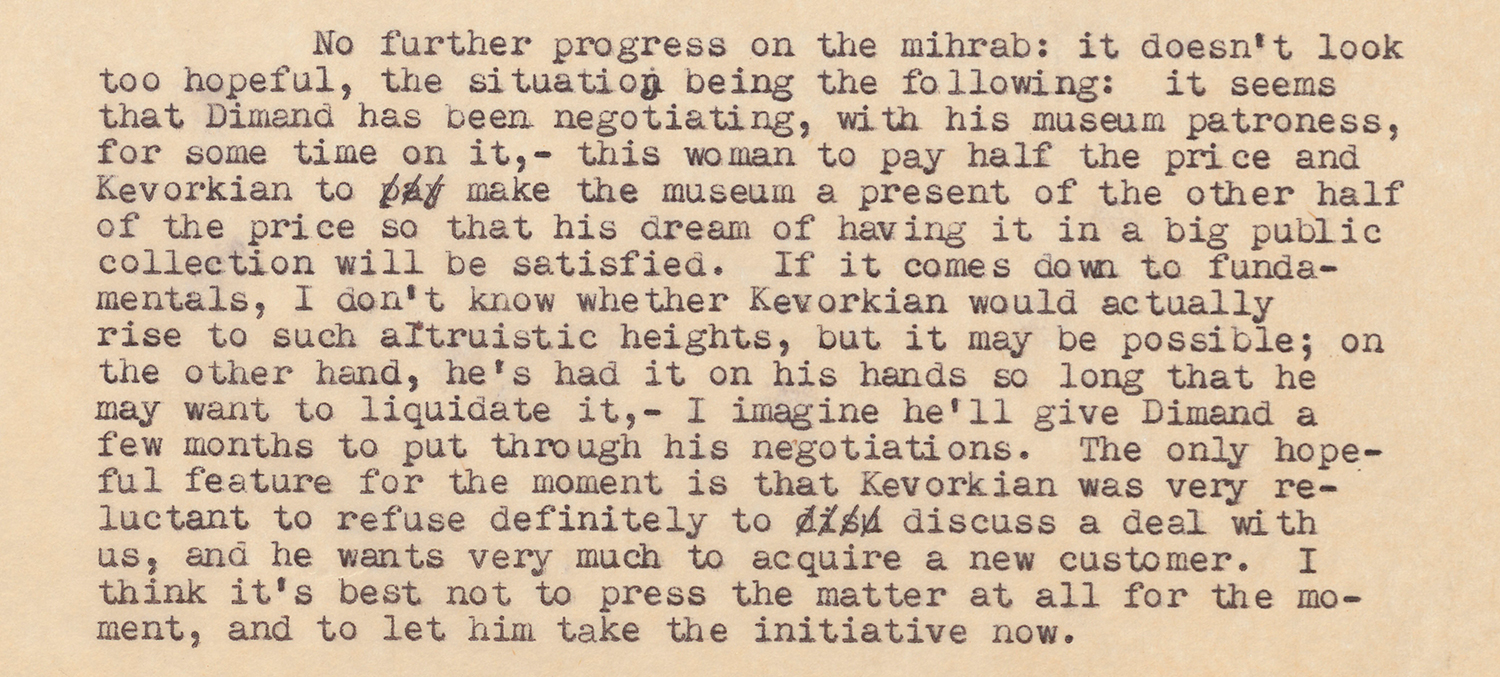

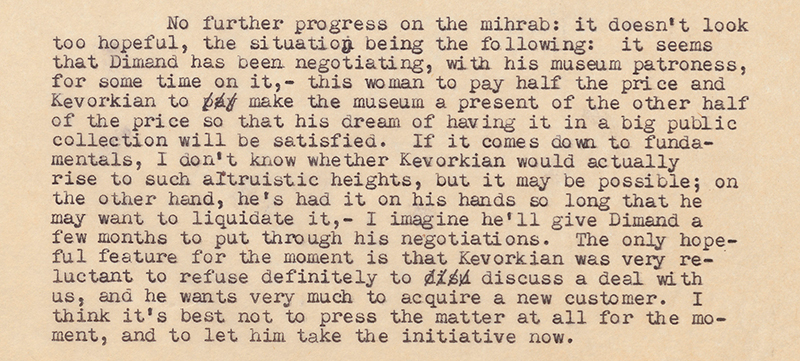

A week later, Crane reports that Dimand’s “museum patroness” would pay half the asking price, and Kevorkian would waive the other half as a gift “so that his dream of having it in a big public collection will be satisfied” (fig. 168). Crane is doubtful that the dealer will “rise to such altruistic heights” and recognizes Kevorkian’s probable desire to “liquidate” the mihrab since he had had it for so long. His lack of outright refusal gives her a degree of hope, and she continues to sense that he might want a new customer. She concludes, “I think it’s best not to press the matter at all for the moment, and to let him take the initiative now” (fig. 168). In other letters from around this time, Crane senses that the economic insecurities of the Second World War are making Kevorkian anxious to sell.

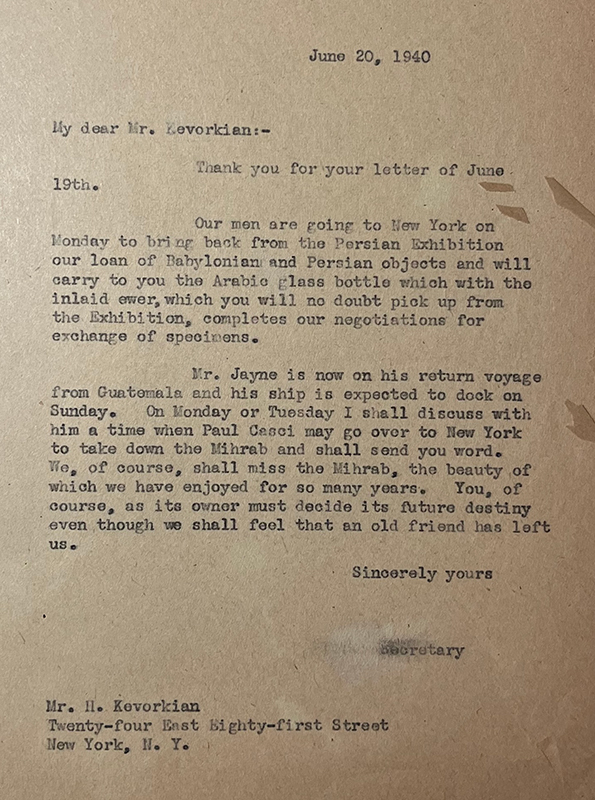

June 1940: New York and Philadelphia

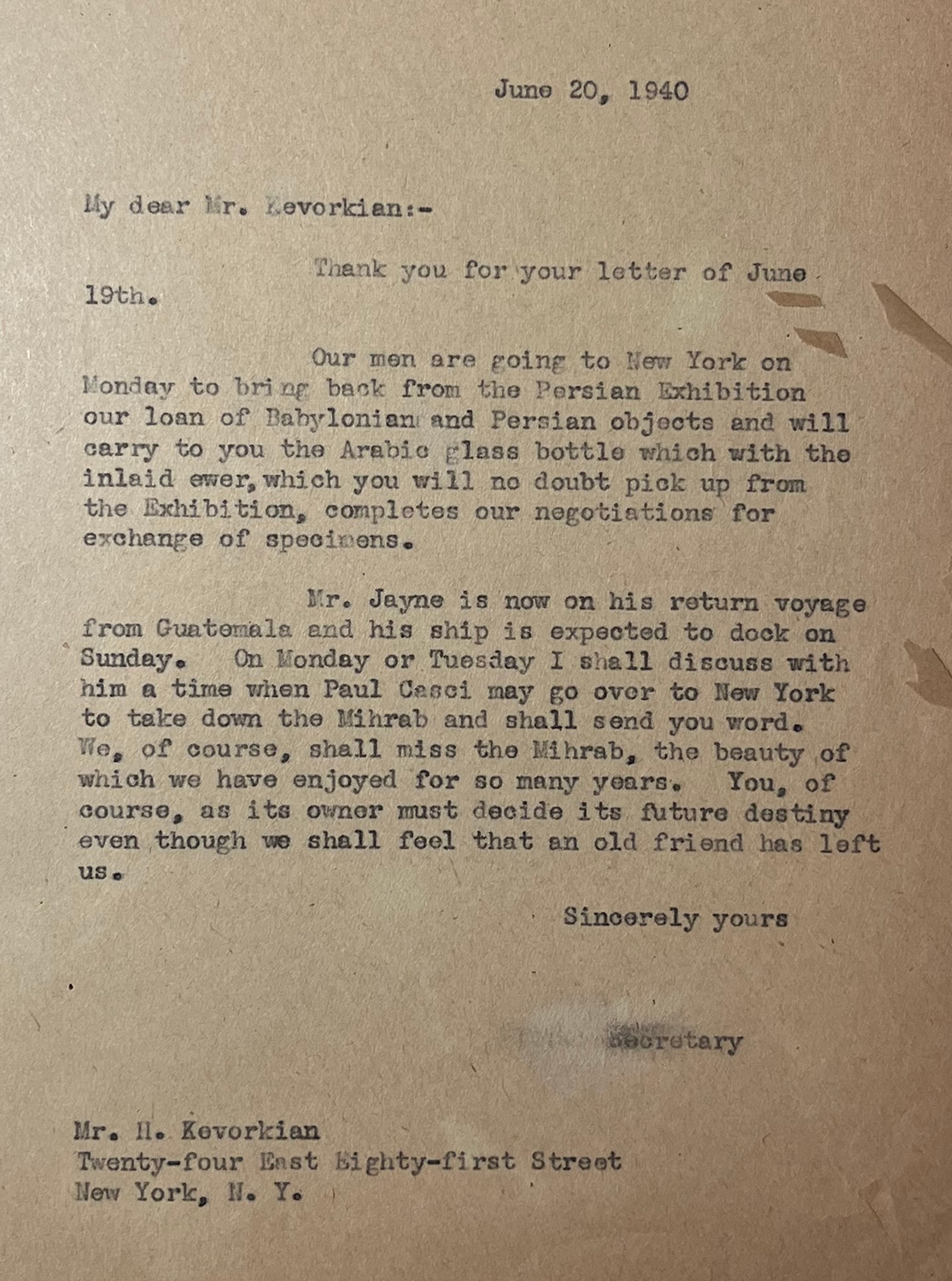

Following the closing of the Persian art exhibition in New York, Hagop Kevorkian writes to Jane M. McHugh, secretary of the Penn Museum, informing her of his decision to keep the mihrab in New York “to give to other communities the chance to see it as Philadelphians had the opportunity to see it during the last quarter of a century.”199 McHugh replies the following day: “We, of course, shall miss the Mihrab, the beauty of which we have enjoyed for so many years. You, of course, as its owner must decide its future destiny even though we shall feel that an old friend has left us” (fig. 169). With this exchange, the mihrab’s tenure at the Penn Museum comes to an end.

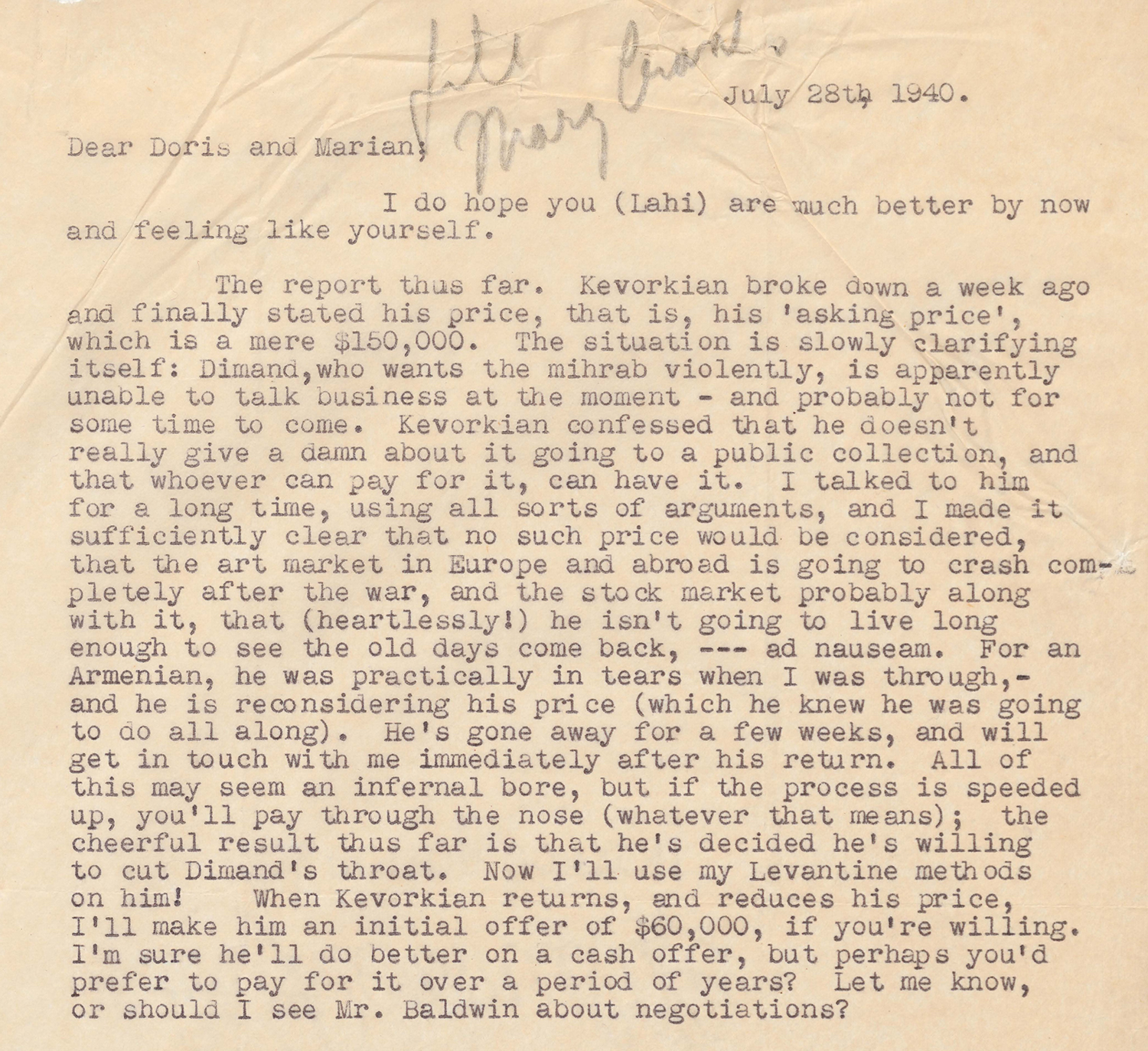

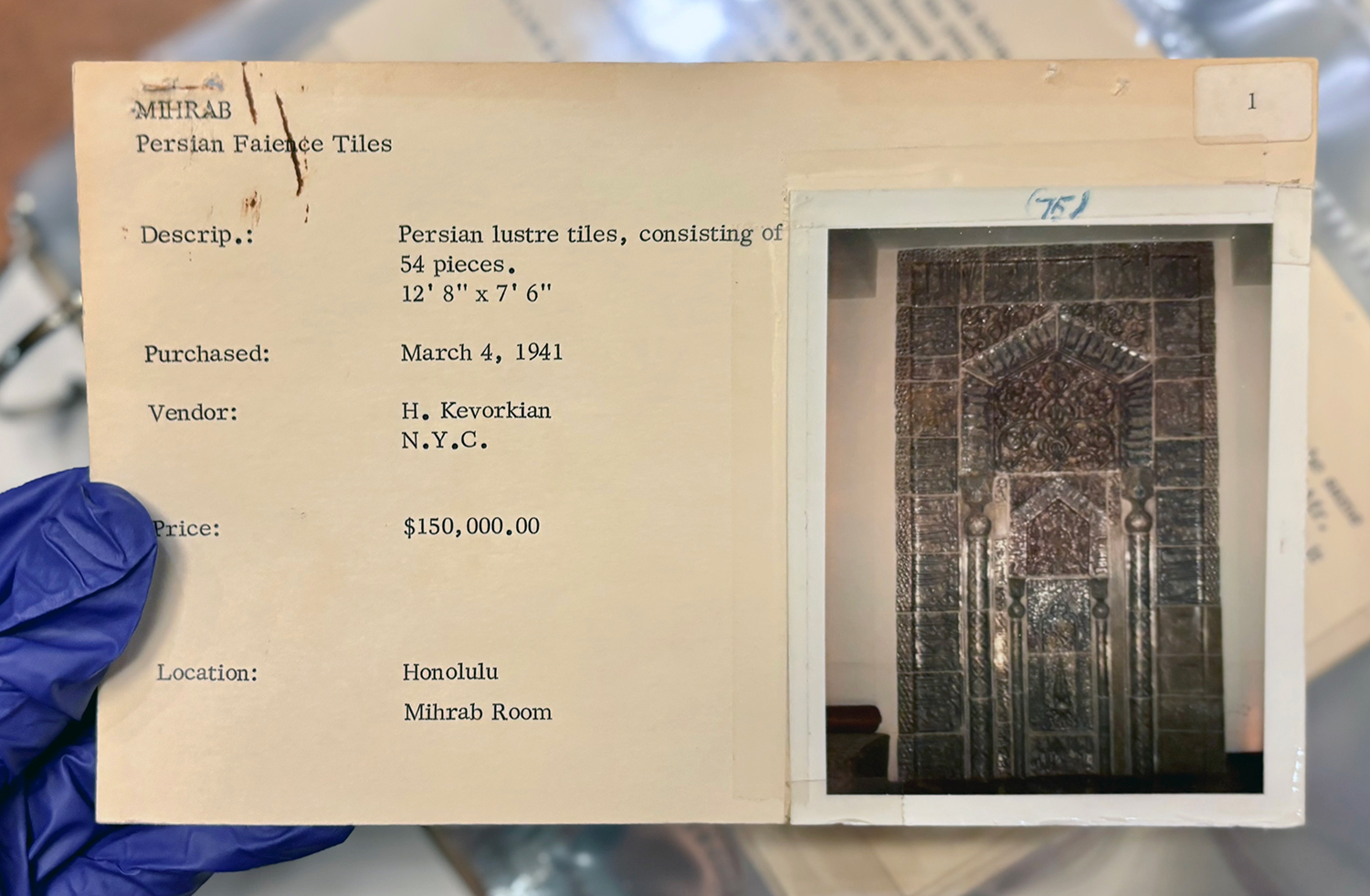

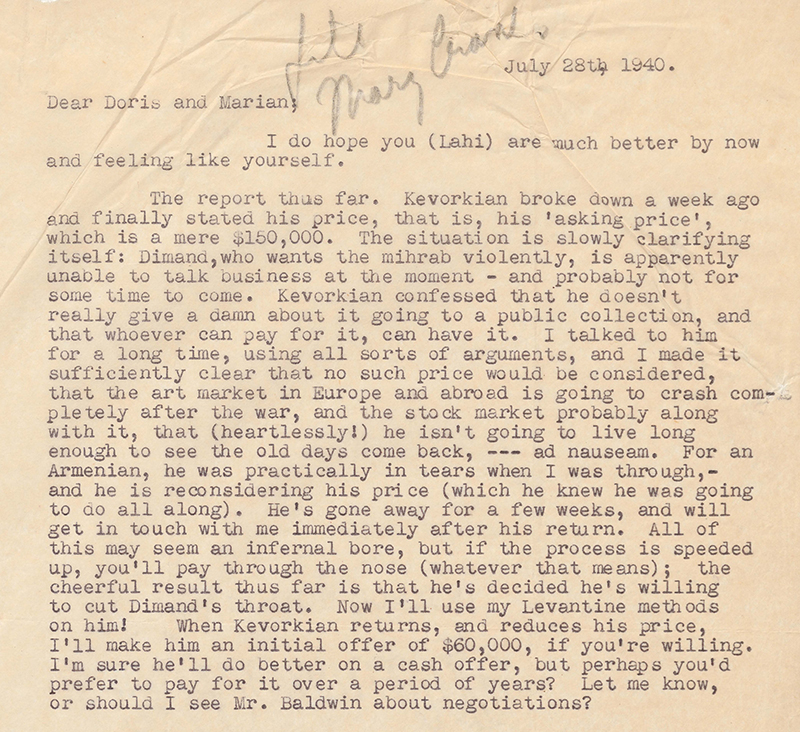

July 1940: New York and Honolulu: Negotiations

Kevorkian reveals his asking price to Crane: $150,000 ($3,471,171 in August 2025). Dimand apparently “wants the mihrab violently” but is “unable to talk business at the moment, and probably not for some time to come” (fig. 170). Kevorkian had admitted to Crane that he did not really care about it going to a public collection and “whoever can pay for it can have it.” Crane refers to a lengthy conversation with Kevorkian in which she raised a number of war-related circumstances, including the potential crash of the art market and stock market. She outlines her strategy to lower the price—what she refers to as her “Levantine methods”—and plans to make him an initial offer of $60,000.

“Whoever can pay for it, can have it”

These exchanges reveal a grim reality: the fate of the mihrab boiled down to money and whoever could pay the highest price. They also underscore Crane’s decisive skills and calculated moves as Duke’s agent. She wisely framed the deal in light of global economic insecurities, was prepared to leverage Duke’s ready cash, and also seems to have unsettled the now 68-year-old dealer.

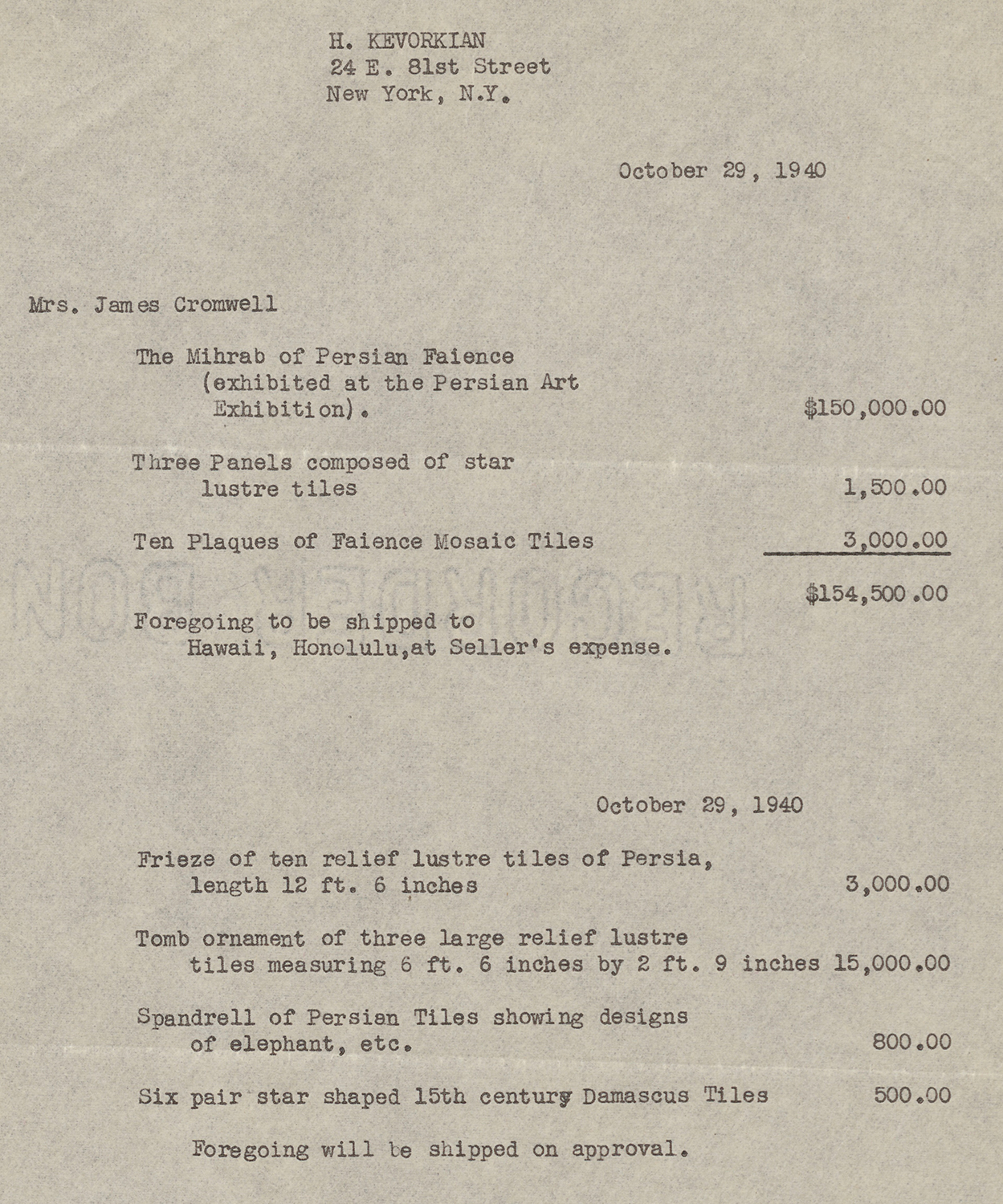

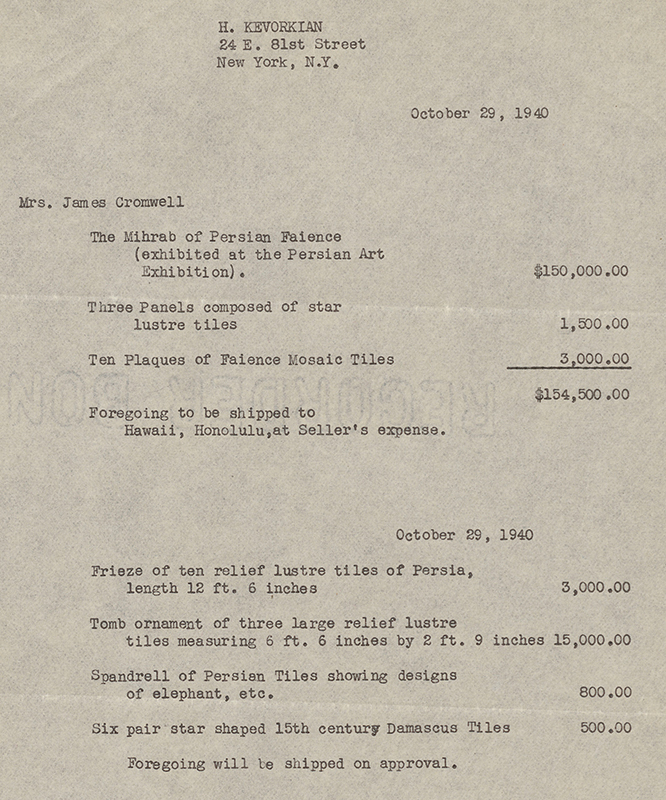

October–November 1940: Honolulu: Acquisition and Preparations

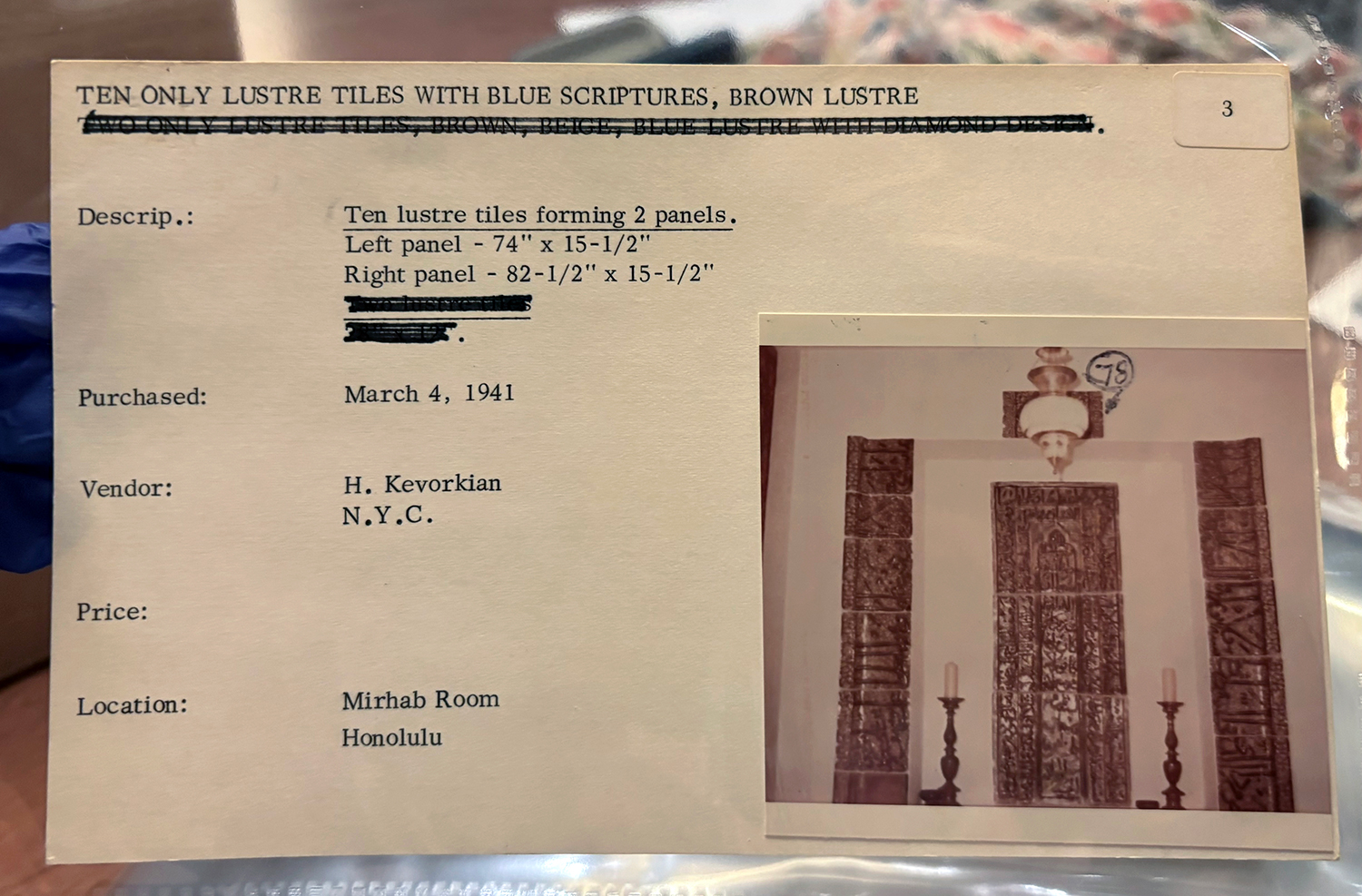

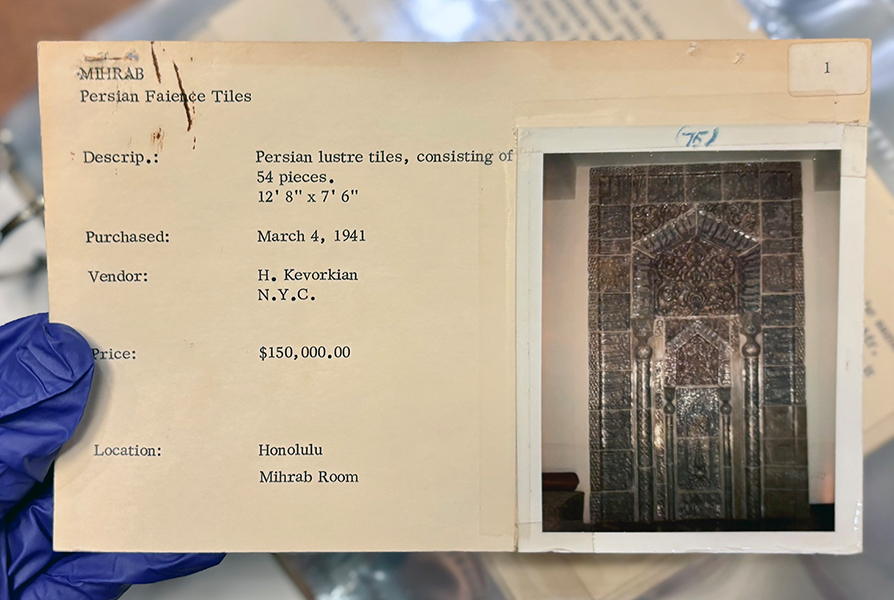

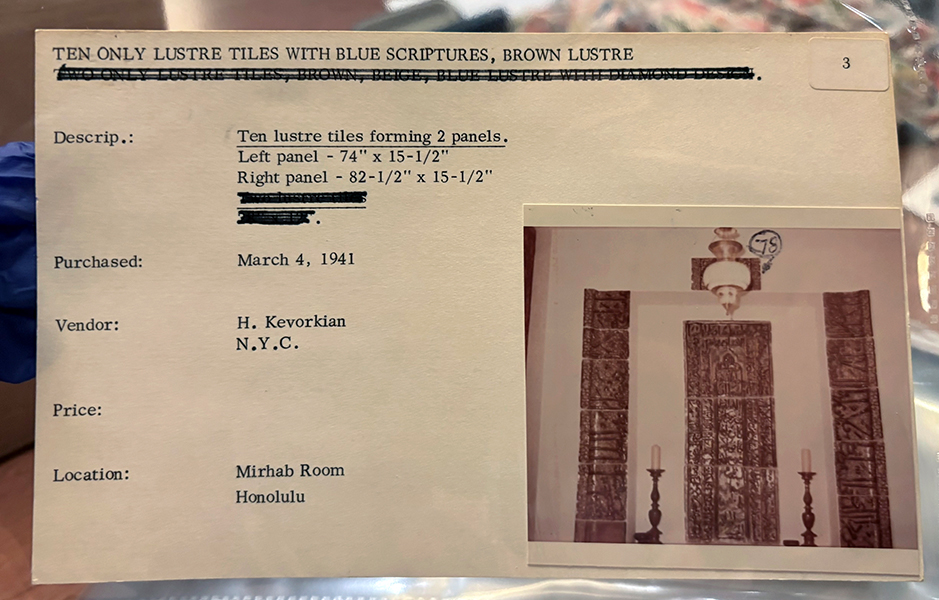

Kevorkian and Duke settle on the price of $150,000 for the mihrab.200 This figure is over double Crane’s initial offer ($60,000) and $120,000 more than what the Penn Museum was willing to pay in 1929 (fig. 171). Along with the mihrab, Duke purchases two other important ensembles of luster tilework from Kevorkian: a set of ten frieze tiles from an unidentified mihrab signed by Yusof b. ʿAli b. Mohammad b. Abi Taher, son of the maker of the mihrab, and the 713/1313 tombstone panel of Khadijeh Khatun’s cenotaph in the Emamzadeh Khadijeh Khatun in Qom.201 Kevorkian had exhibited this panel in Munich (1910), Paris (1911), and New York (1912), or at least recorded it in those catalogs.

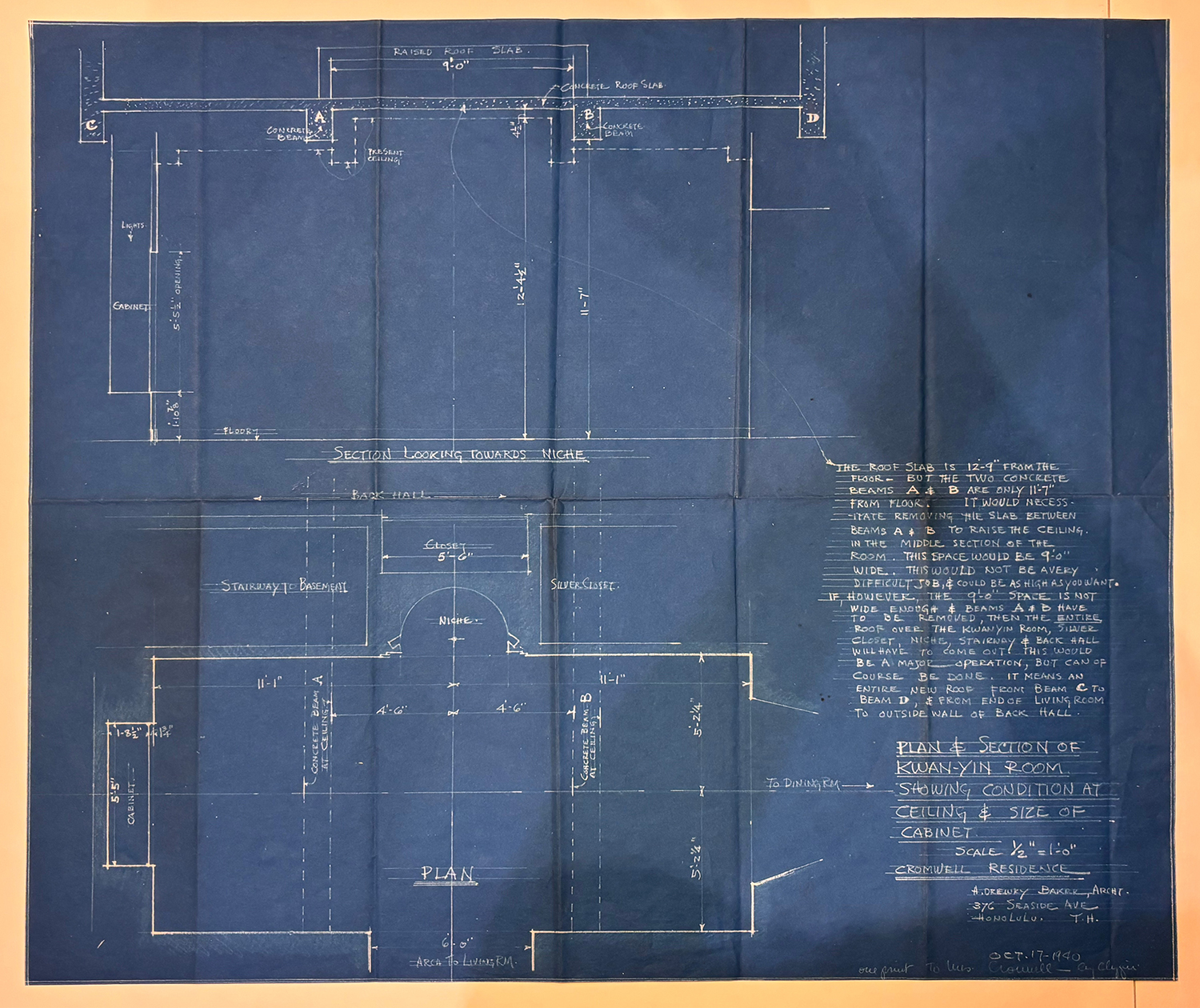

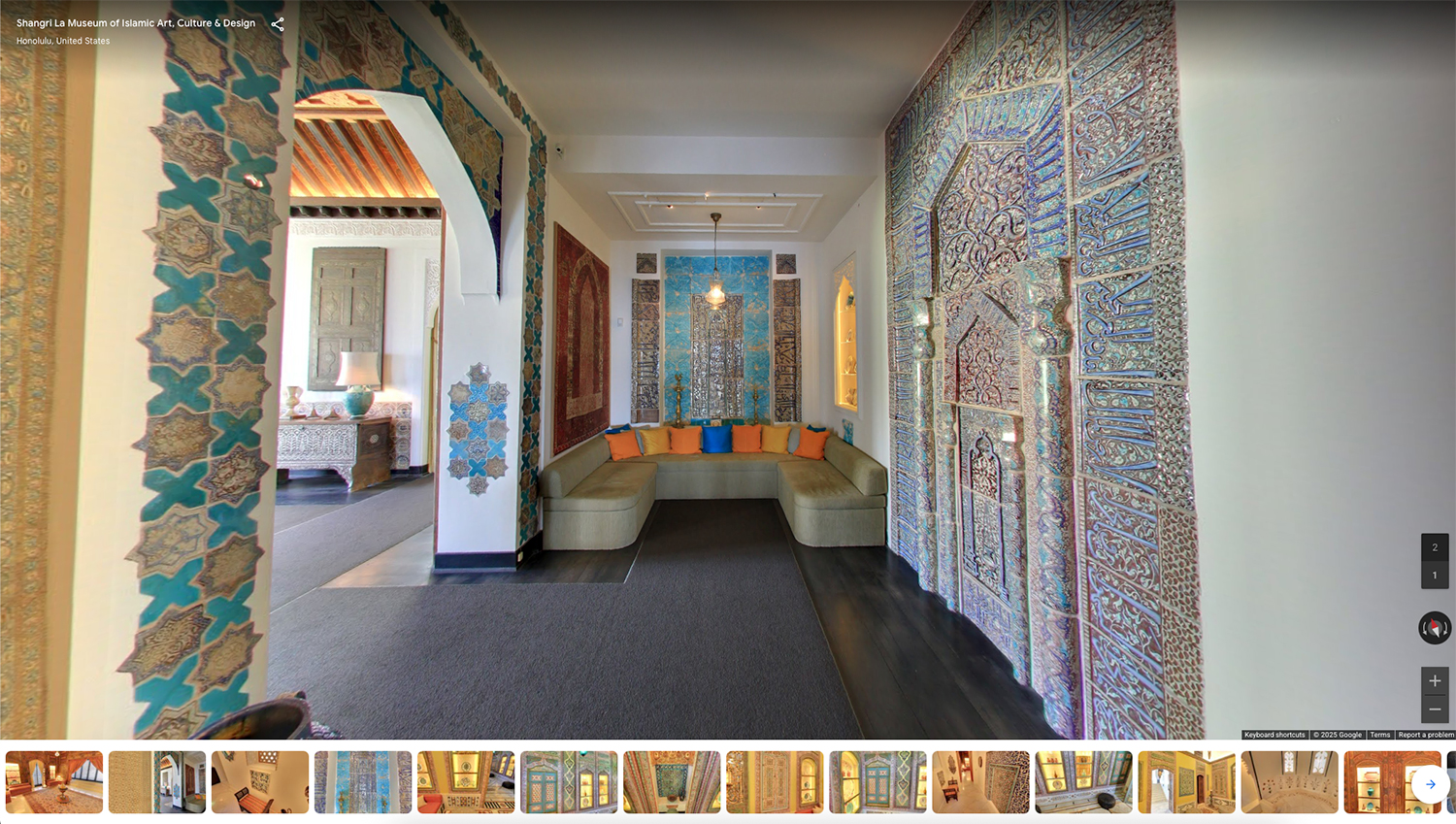

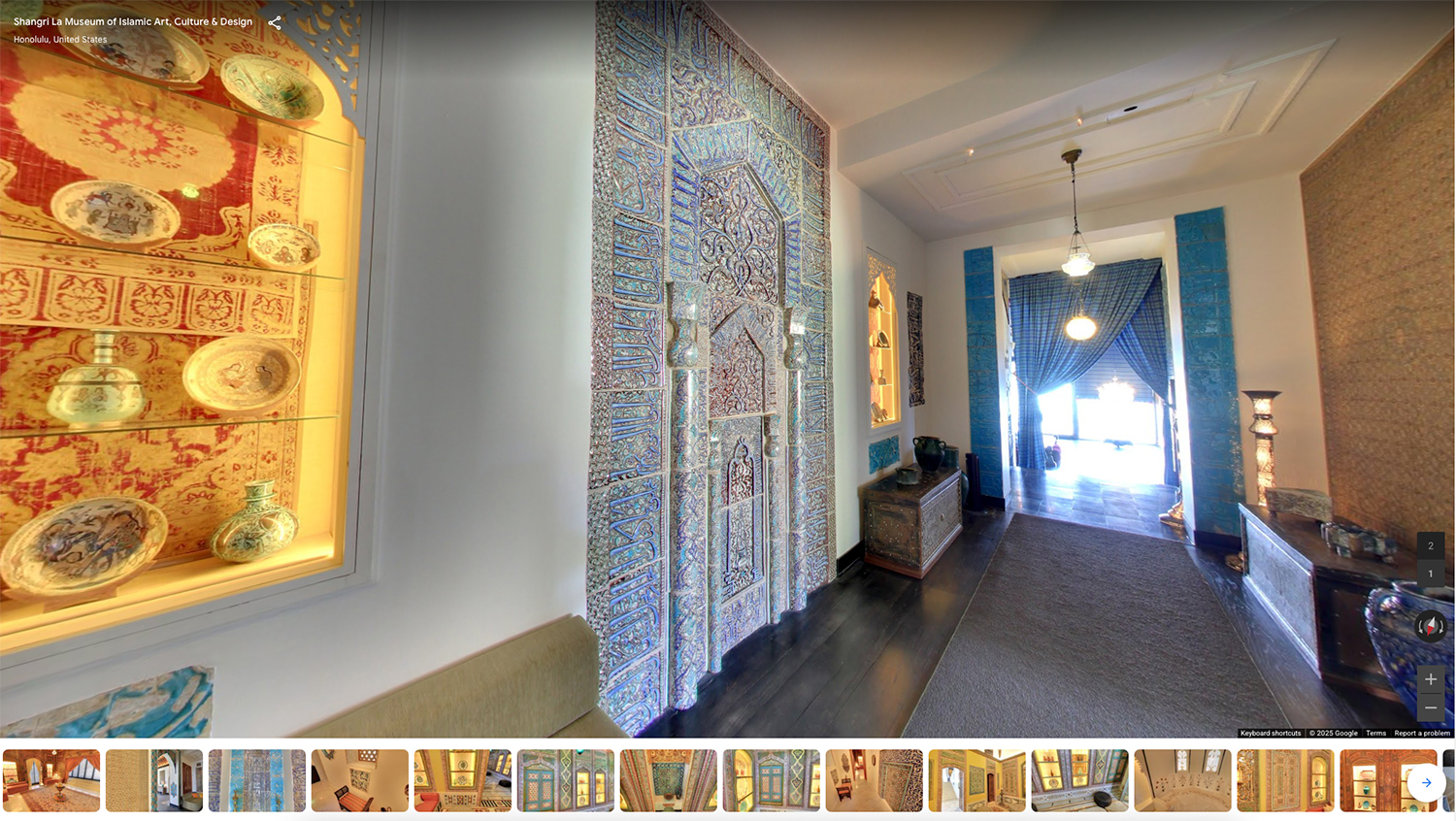

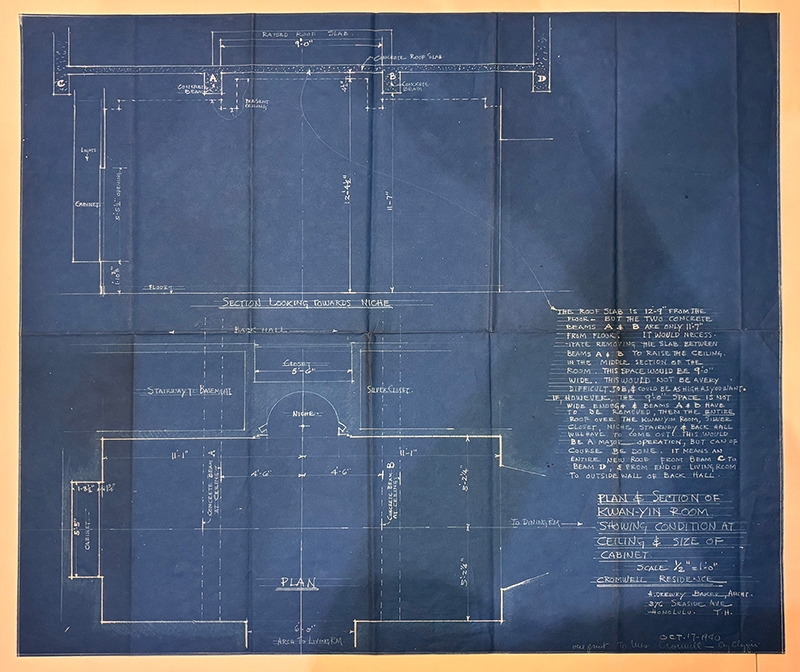

By mid-October, Duke and her team are planning the mihrab’s installation on the east wall of the ‘Kwan-yin Room’ (see fig. 146). The mihrab’s positioning in this space has nothing to do with the qibla, which is approximately 270° (west) from Honolulu, but instead reflects the place of priority reserved for Duke’s most valuable artwork202 The mihrab now eclipses the late fourteenth–fifteenth century Guanyin Bodhisattva and will soon occupy the eastern end of the long sight line traversing the living room, lawn, pool, and Playhouse, and ending with a view of Diamond Head (fig. 172).

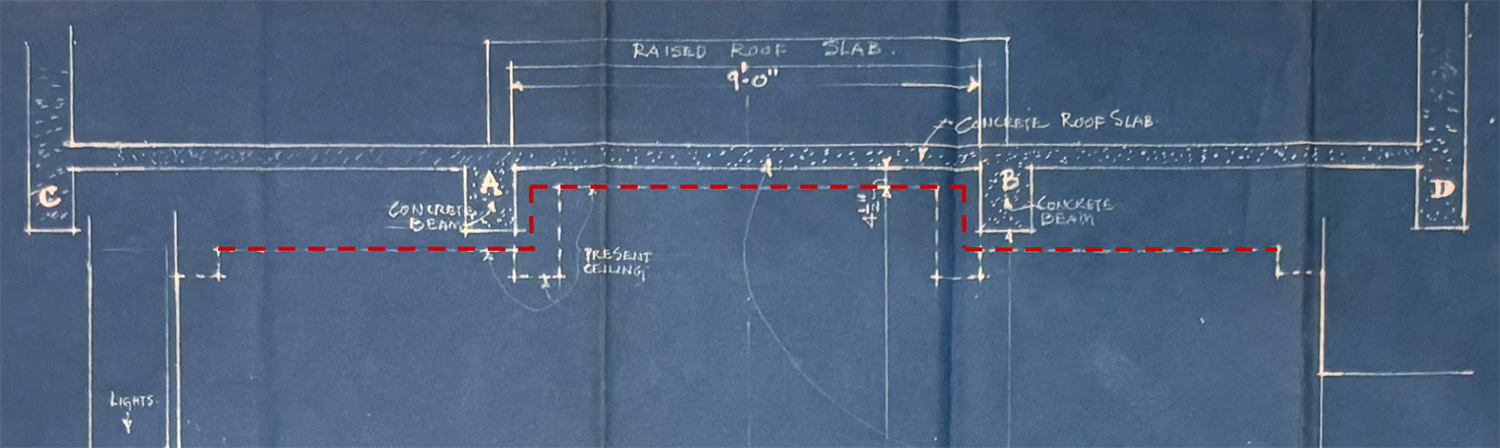

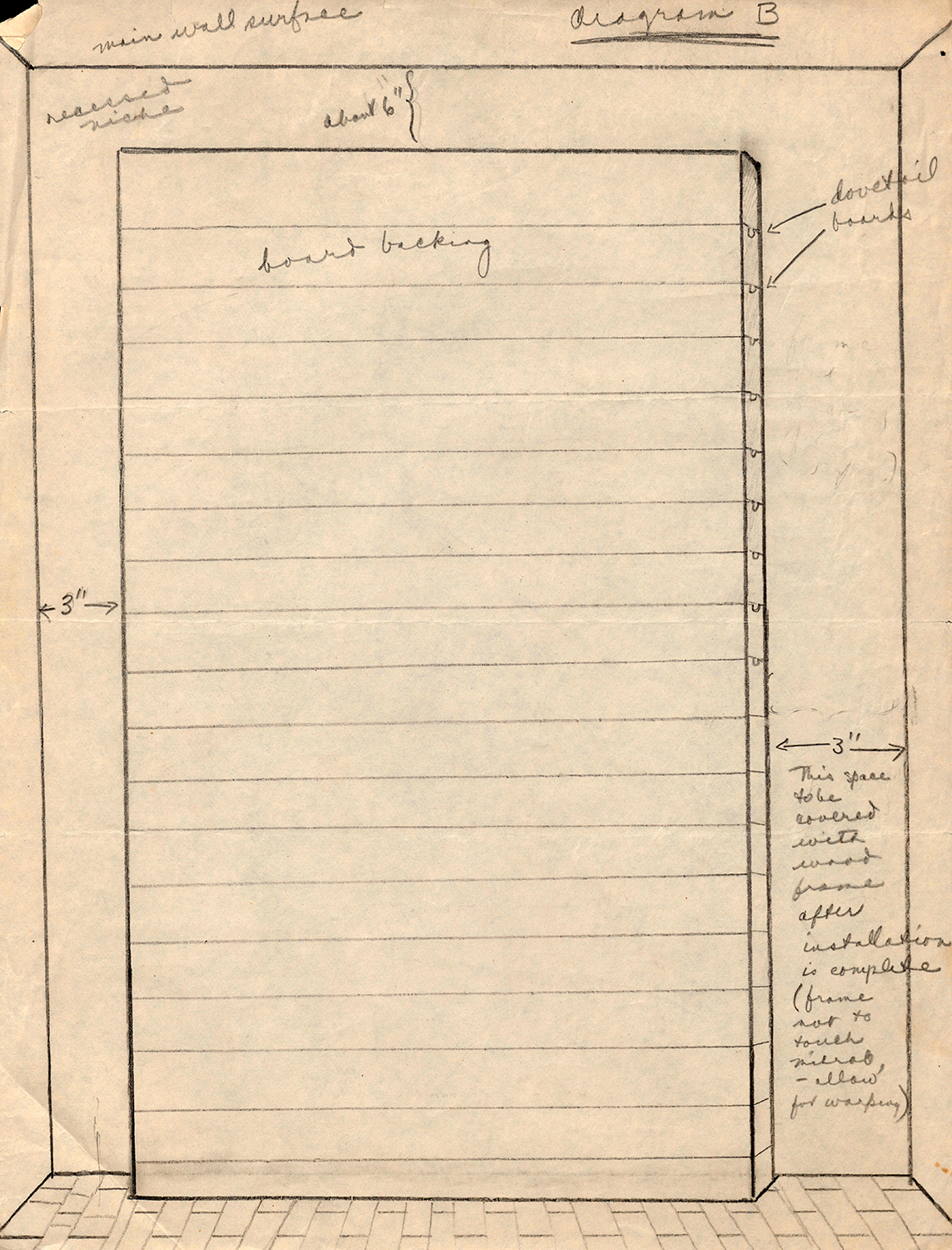

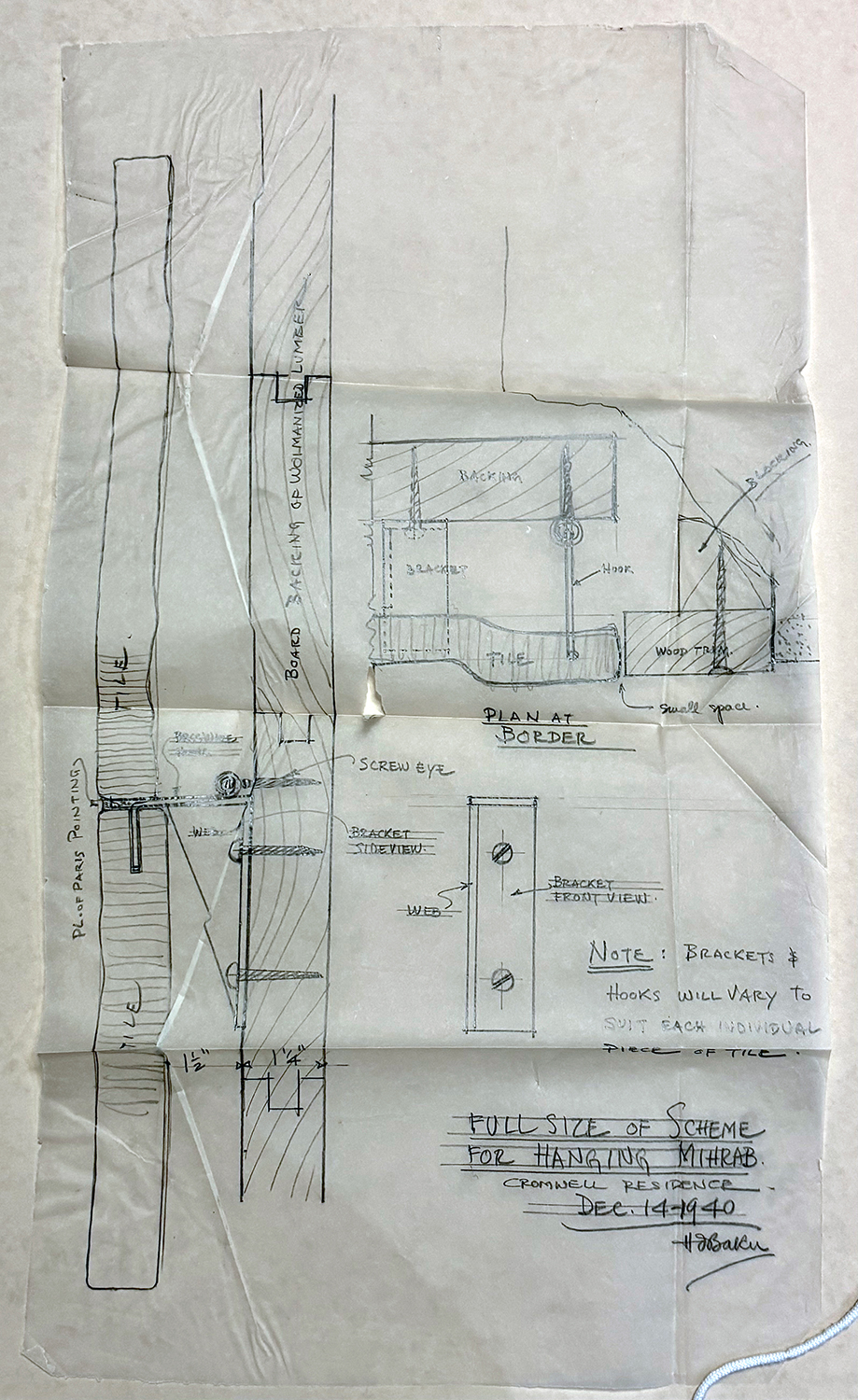

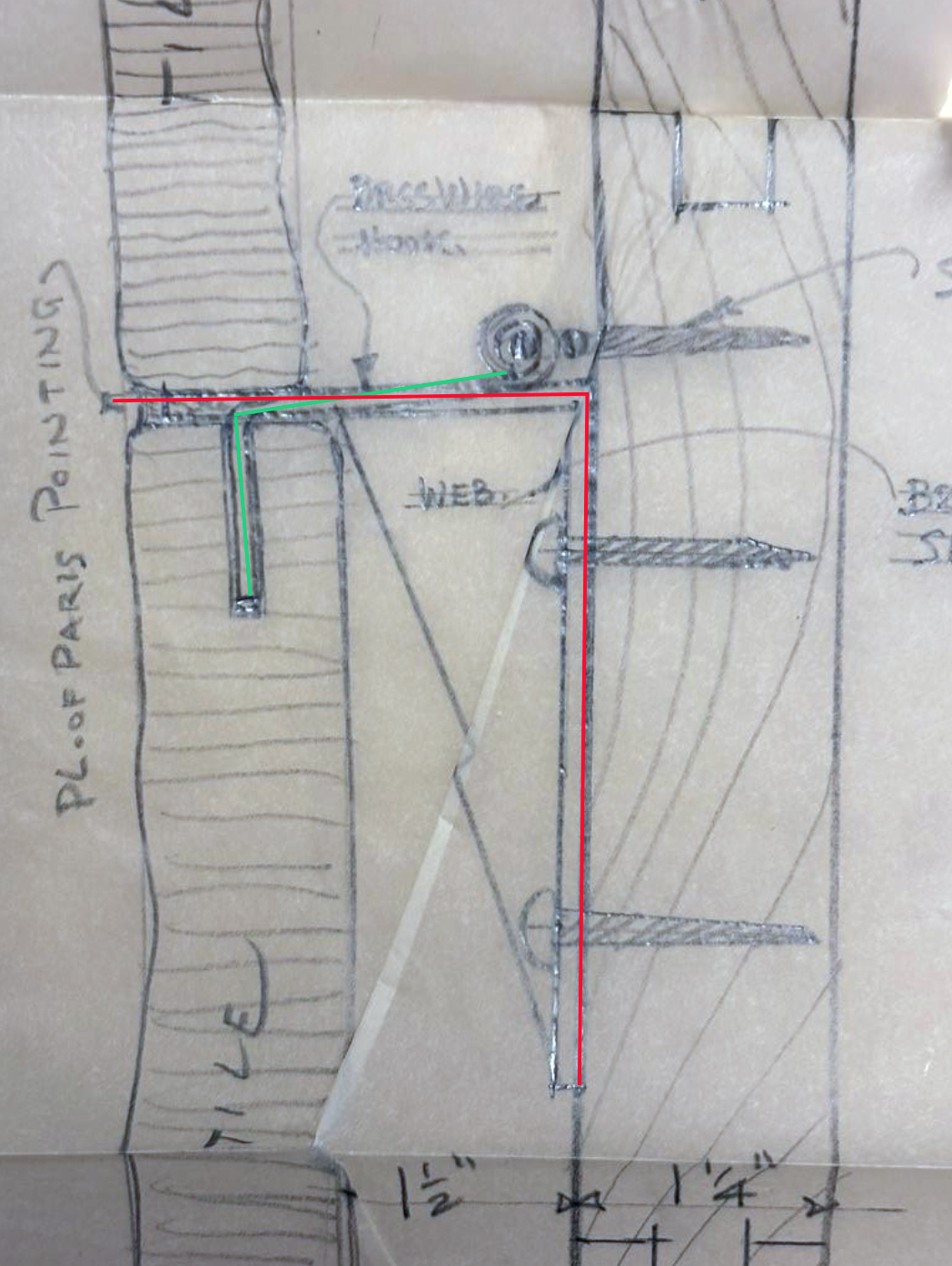

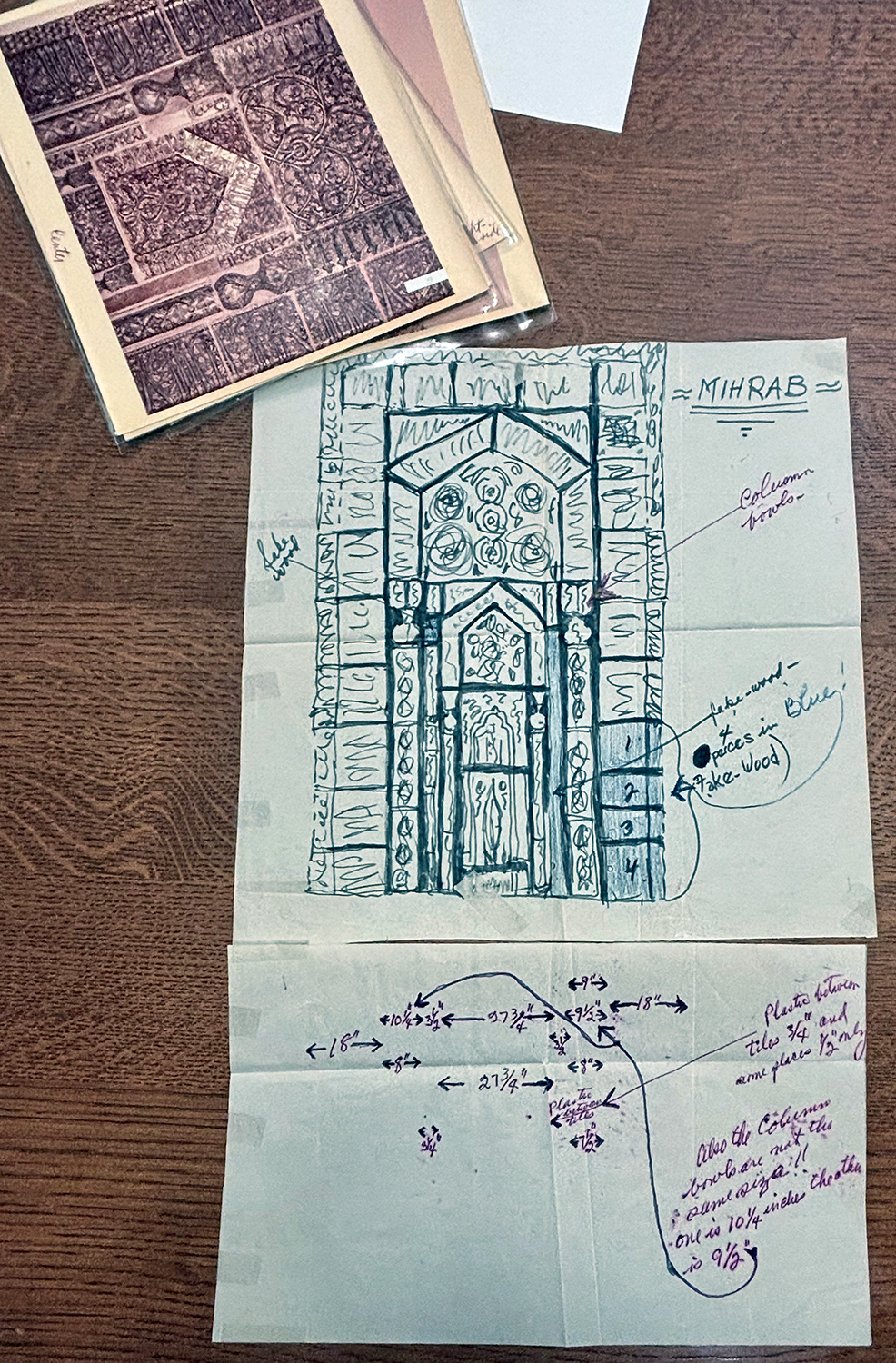

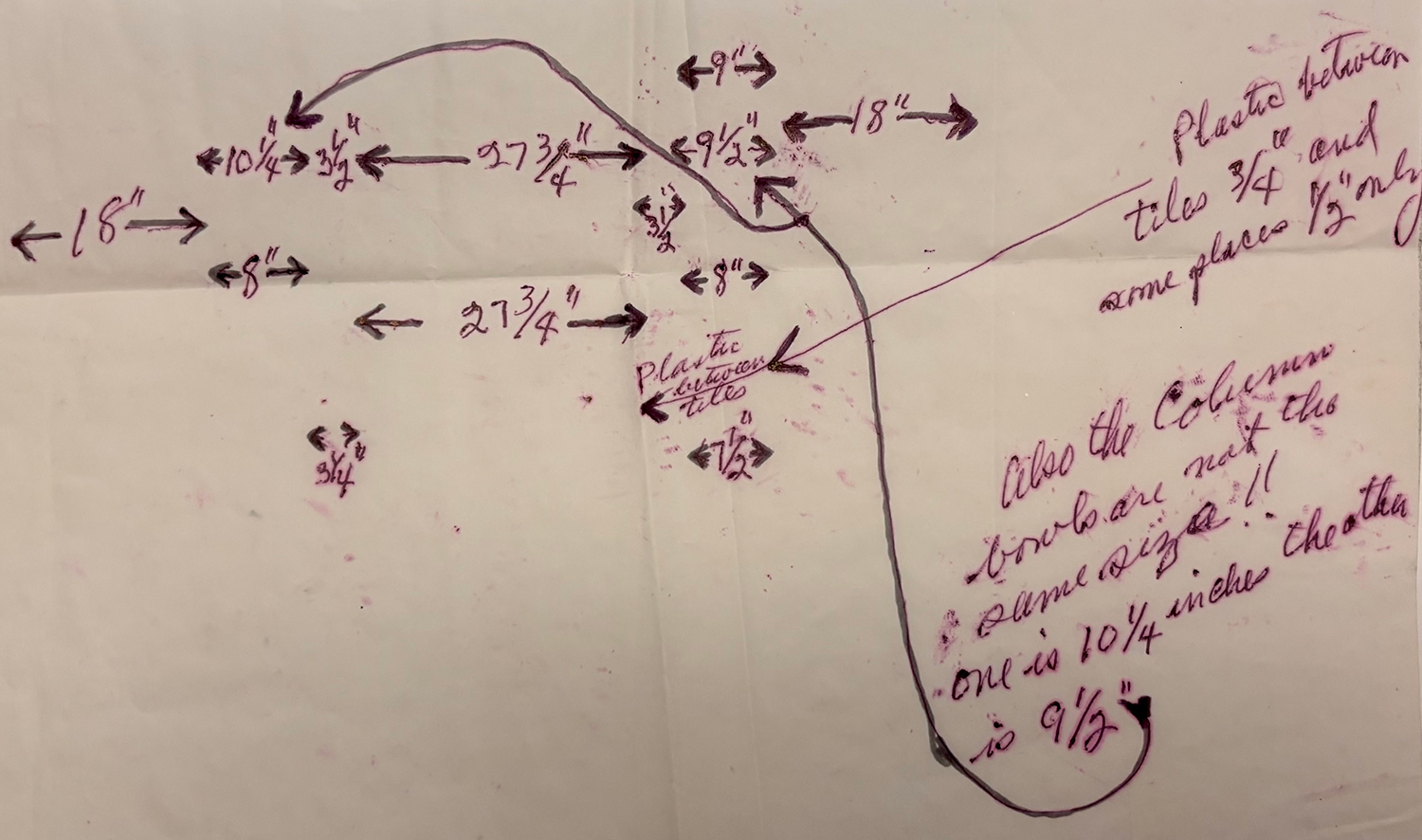

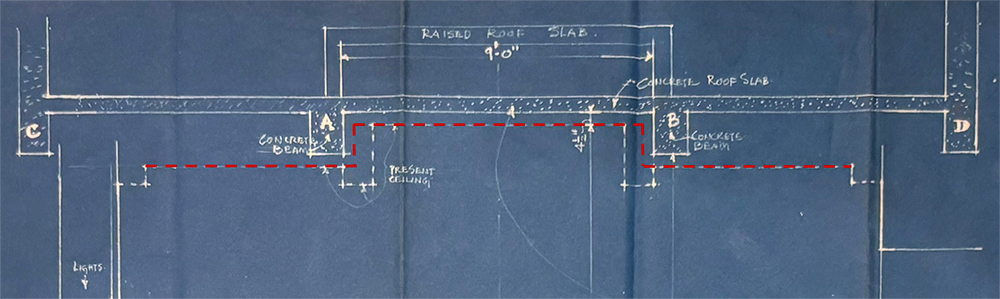

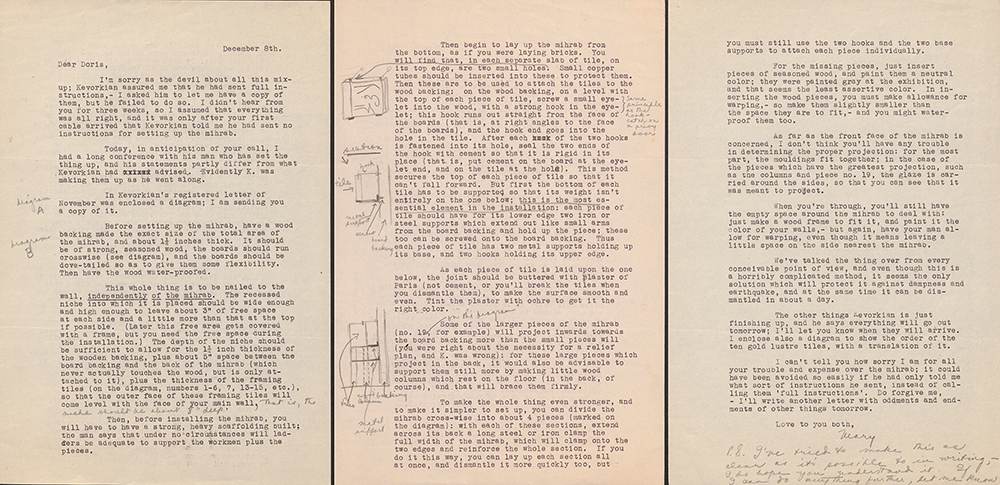

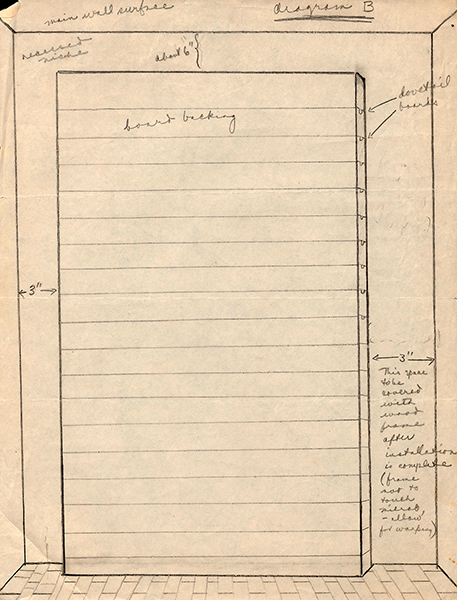

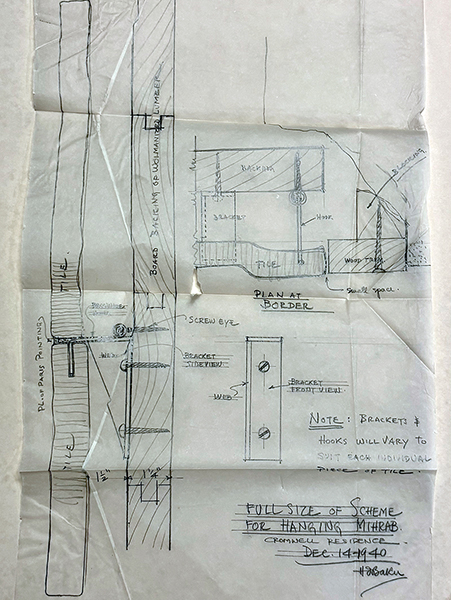

Fitting the sizeable mihrab (H. 151 3/8 × W. 90 in; 12.614 × 7.5 ft; 384.5 × 228.6 cm) in the relatively small room (L. 22.166 × W. 10.375 × H. 12.375 ft; 675.71 × 316.41 × 377.03 cm) presents a problem, especially given the height of the ceiling (12.375 ft) and two projecting concrete beams.203 In mid-October, Shangri La’s onsite supervising architect Drew Baker (see fig. 138) sends Duke a series of options and solutions. On his detailed plan and section, he writes (fig. 173):

The roof slab is 12’-9” [12.75 ft] from the floor [the height of the ceiling below the slab is 12.375 ft and the mihrab’s height is 12.614 ft] but the two concrete beams A & B are only 11’-7” [11.58 ft] from floor. It would necessitate removing the slab between beams A & B to raise the ceiling in the middle section of the room. This space would be 9’-0” wide [the mihrab is 7.5 ft wide]. This would not be a very difficult job & could be as high as you want. If, however, the 9’-0” space is not wide enough & beams A & B have to be removed, then the entire roof over the Kwanyin Room, silver closet, niche, stairway & back hall will have to come out. This would be a major operation but can of course be done. It means an entire new roof from beam C to beam D, & from end of living room to outside wall of back hall.

Baker’s note and drawing indicate that increasing both the height and width of the area designated for the mihrab was considered necessary, especially the height, which was 2.88 inches (7.5 cm) too short. The current configuration of the ceiling and roof suggest, however, that Baker’s proposal was only partially implemented. Aerial photographs of the building reveal that the roof slab was never raised, and photographs of the interior confirm that only a few centimeters exist between the top edge of the mihrab and the ceiling, meaning it also was not raised (figs. 175–176). Given that the mihrab exceeded the ceiling height by 2.88 inches (7.5 cm), the decision not to raise the ceiling appears to have resulted in burying the last border tile of the mihrab (jump ahead to December 1940).

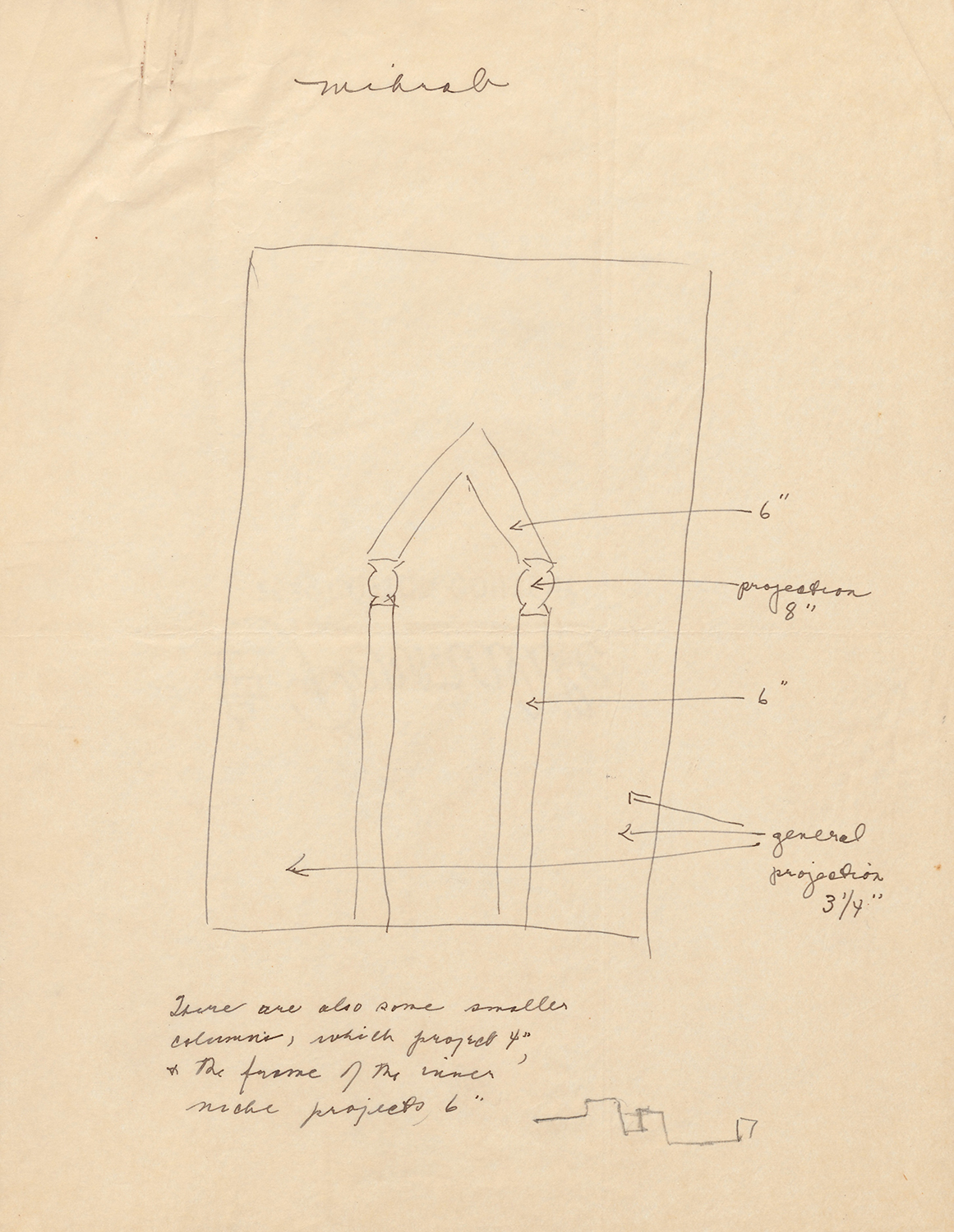

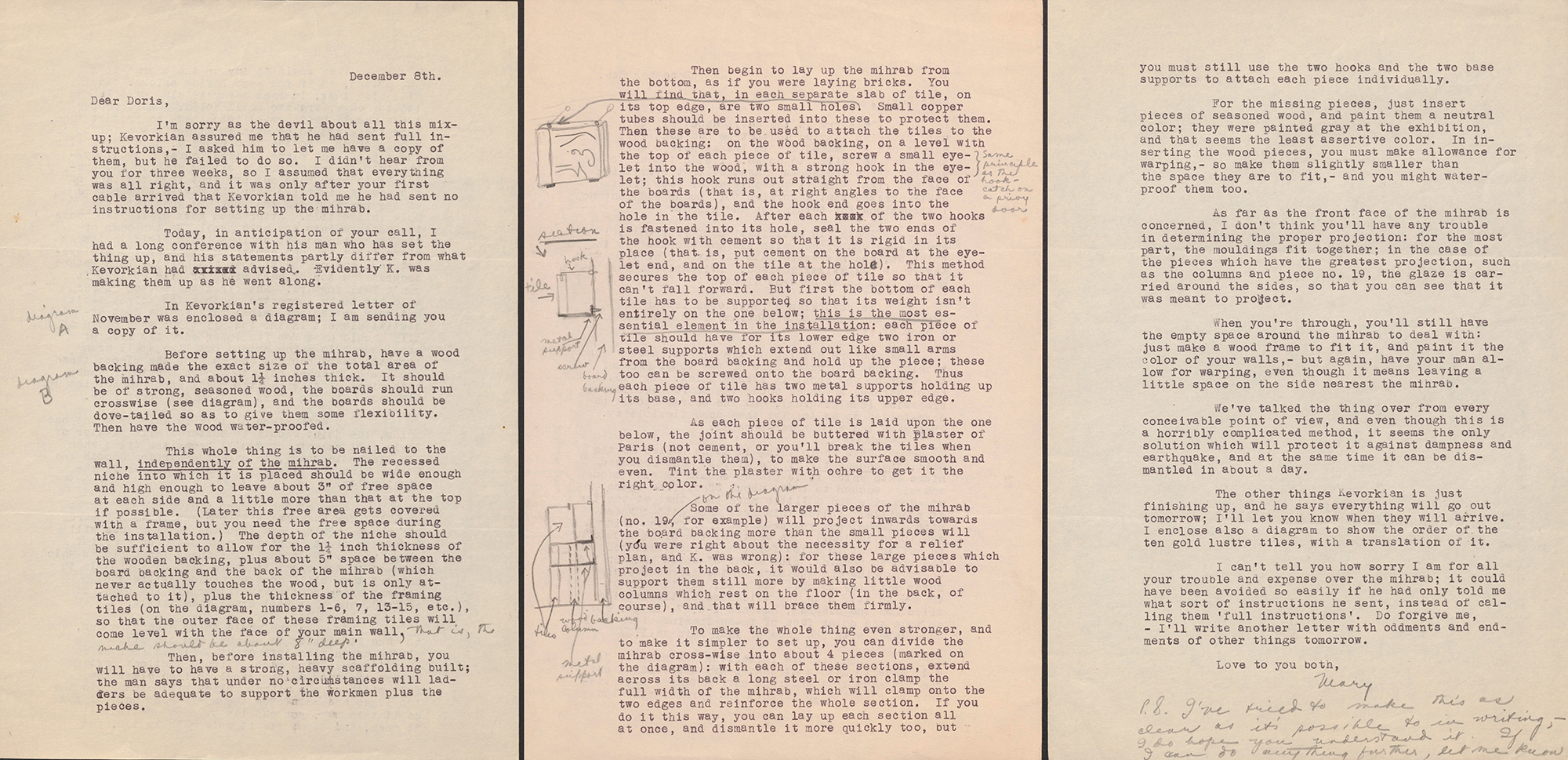

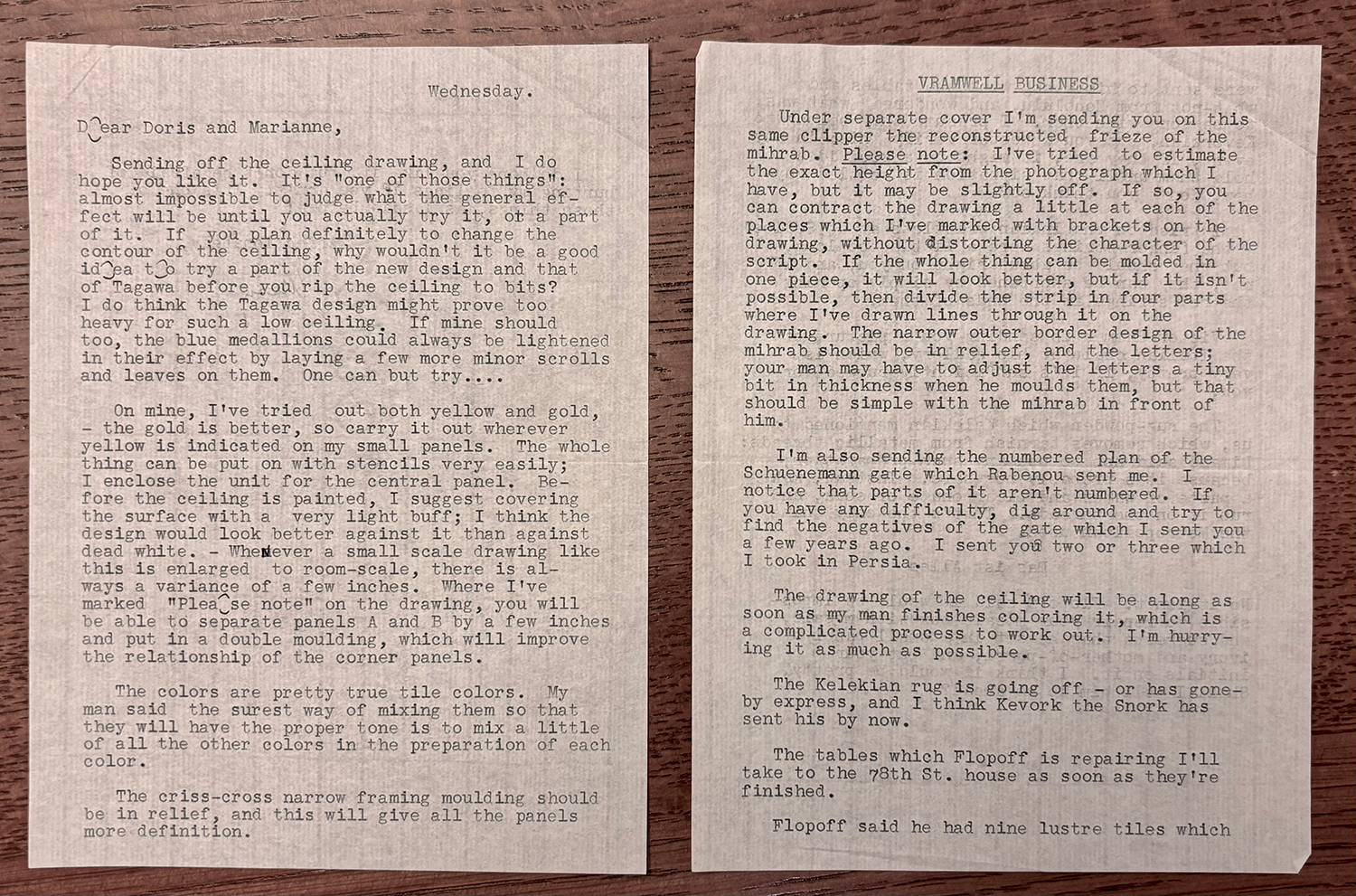

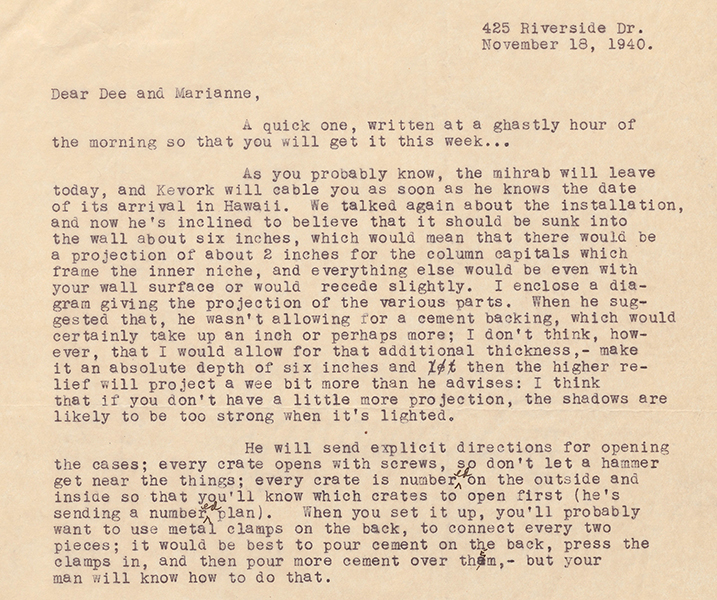

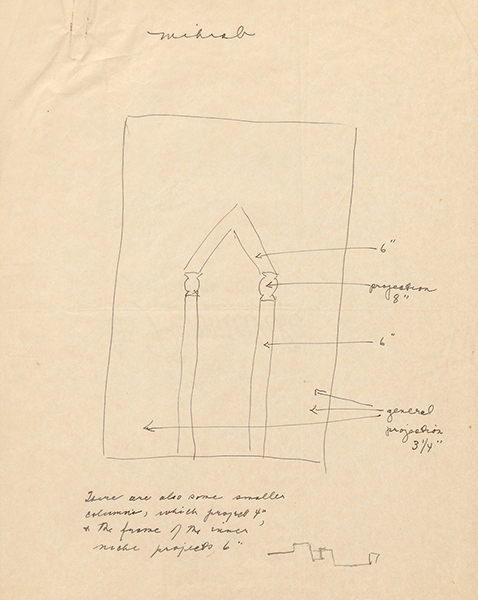

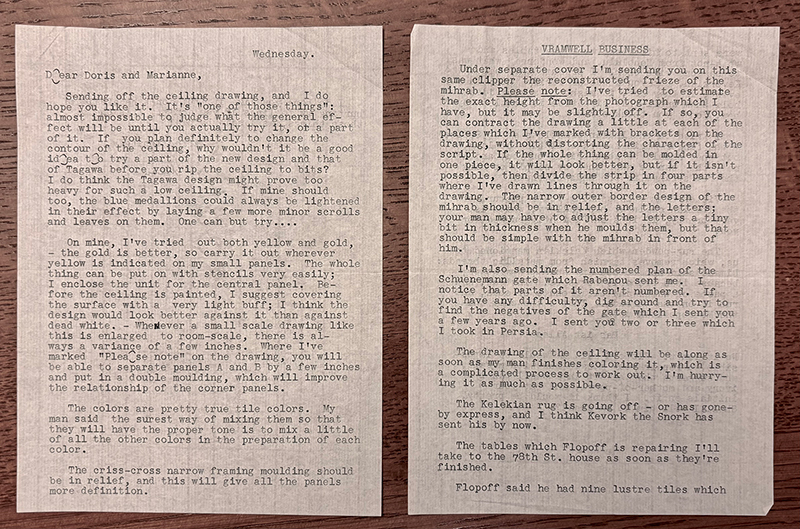

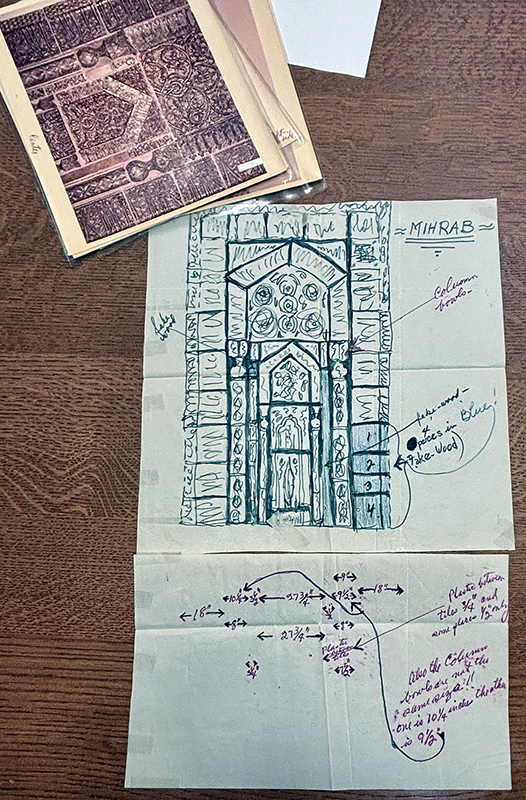

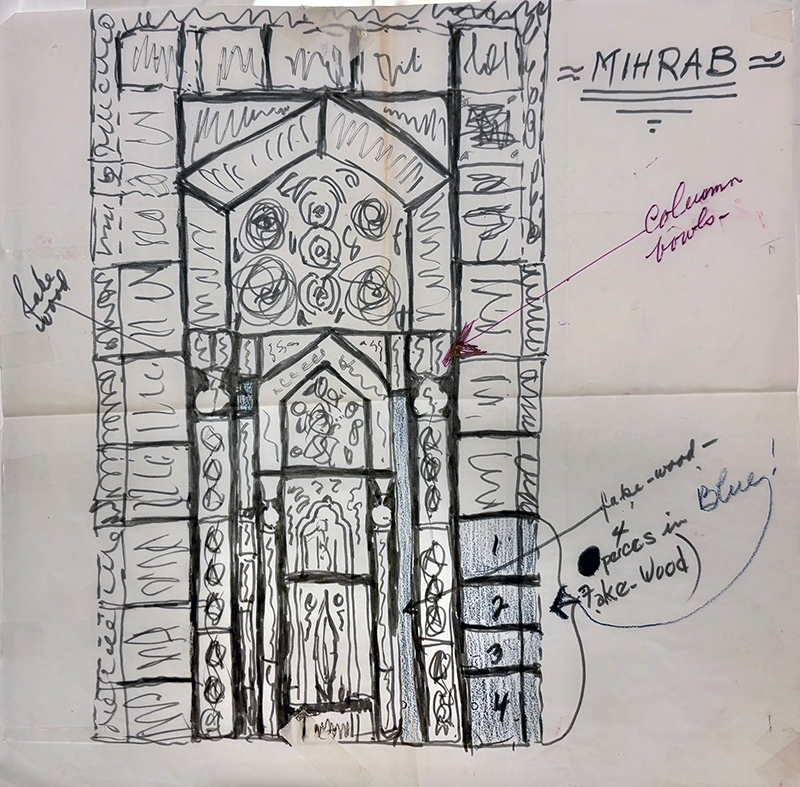

About a month later, on 18 November, Crane reports that the mihrab is on its way and includes the first of several diagrams guiding its installation (figs. 177–178). The focus of discussion is now the mihrab’s degree of recession and projection and how it will appear when lit.204 Crane promises to send explicit directions for opening the crates and warns, “don’t let a hammer get near the things” (fig. 177).

Around this time, Duke announces her separation from husband James H. R. Cromwell.205

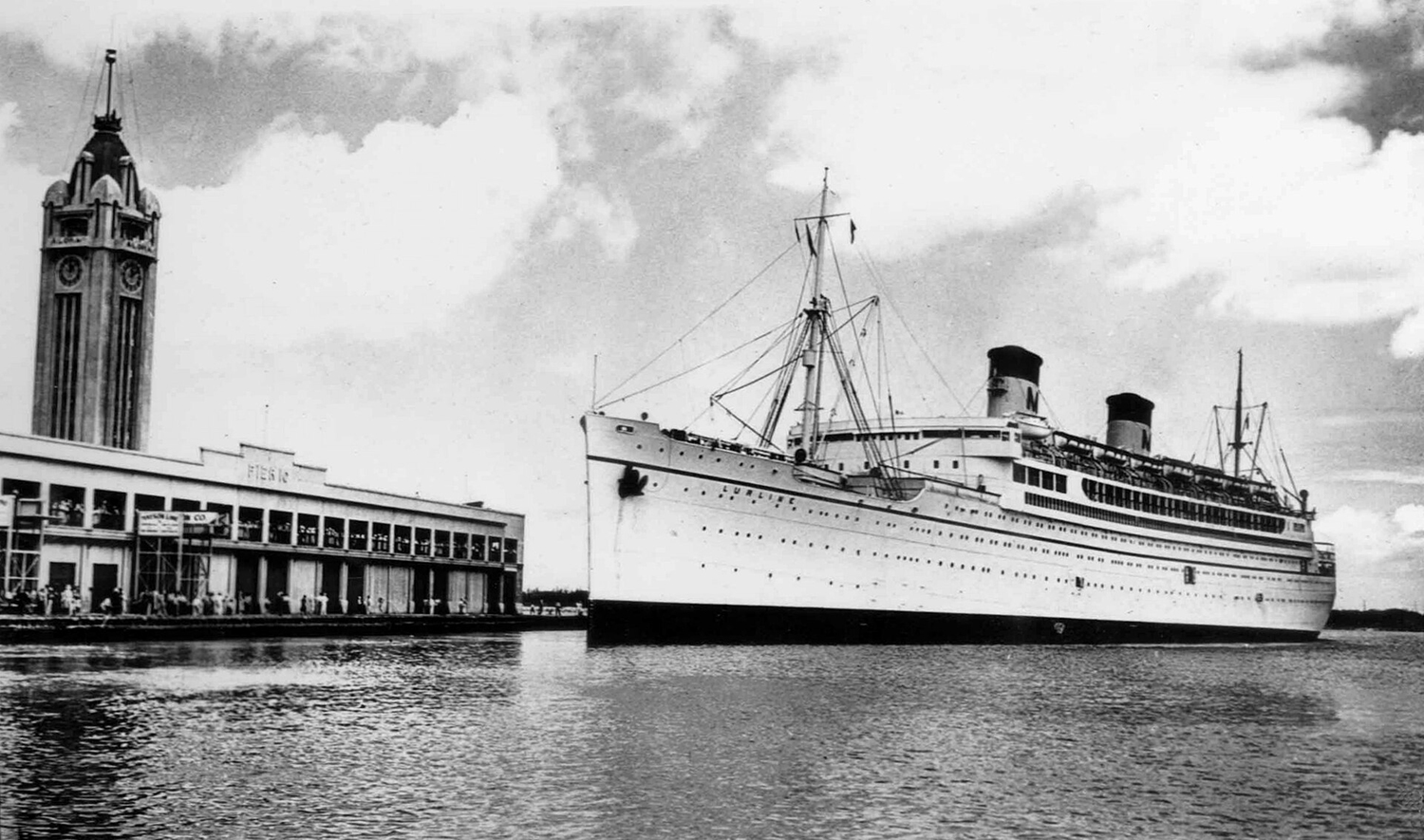

December 1940: Honolulu: Arrival and Installation

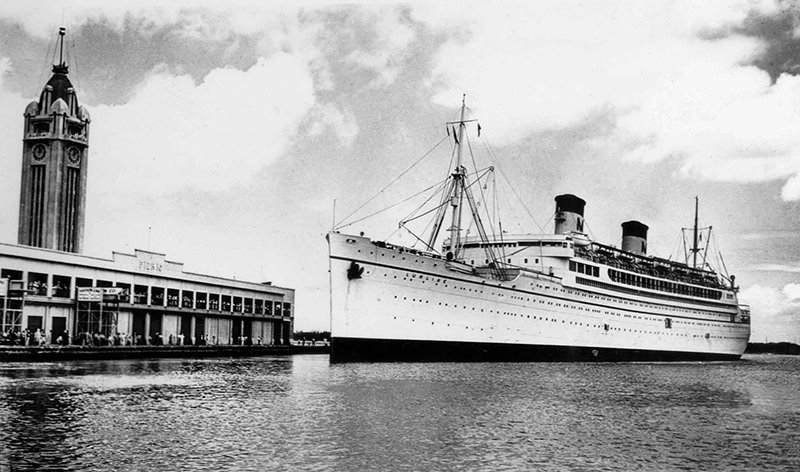

The mihrab arrives in Honolulu on 4 December aboard the SS Lurline of the Matson Line (figs. 179–180). The luster tiles from an unidentified mihrab and the cover of Khadijeh Khatun’s cenotaph (Emamzadeh Khadijeh Khatun) will soon follow.

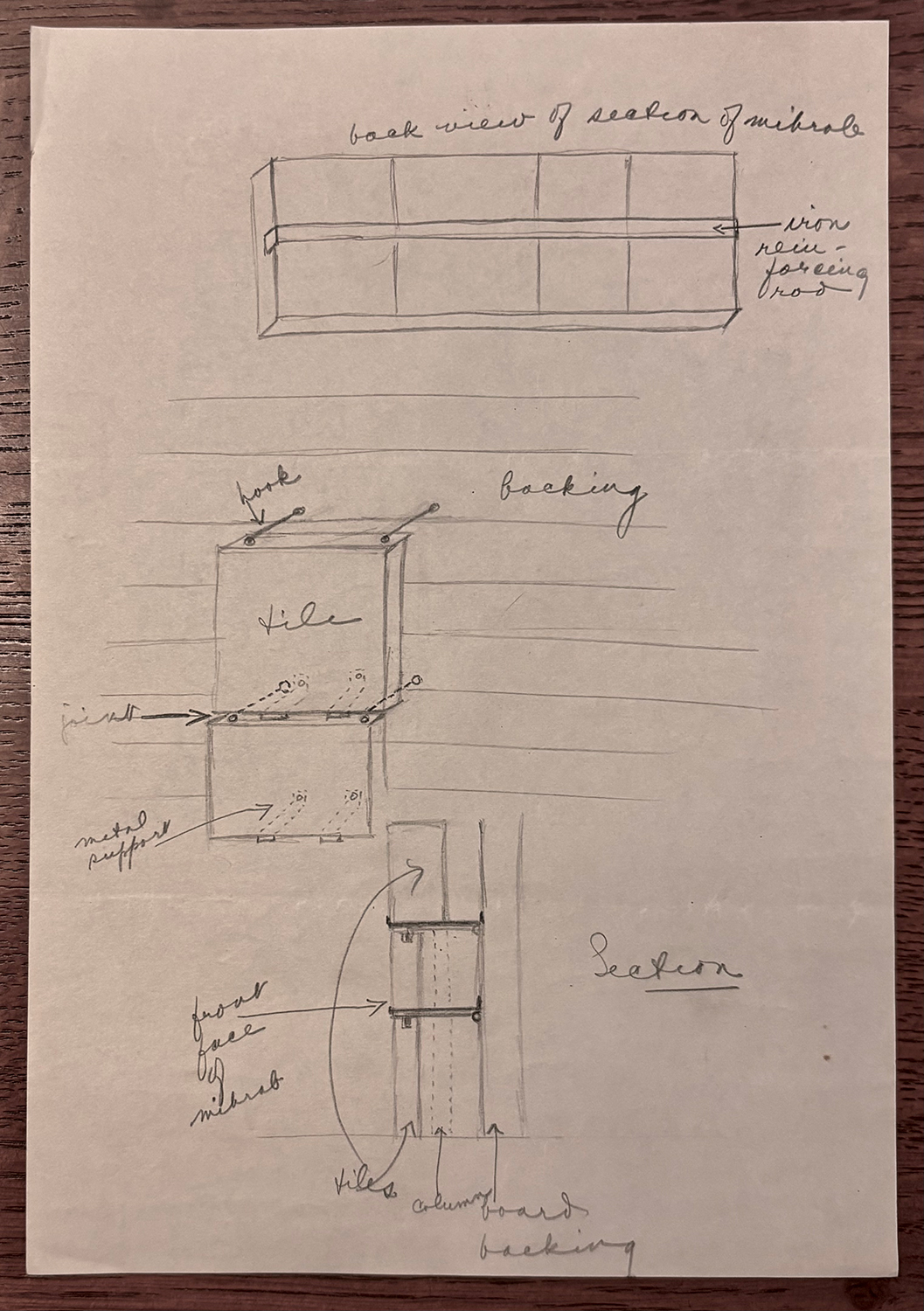

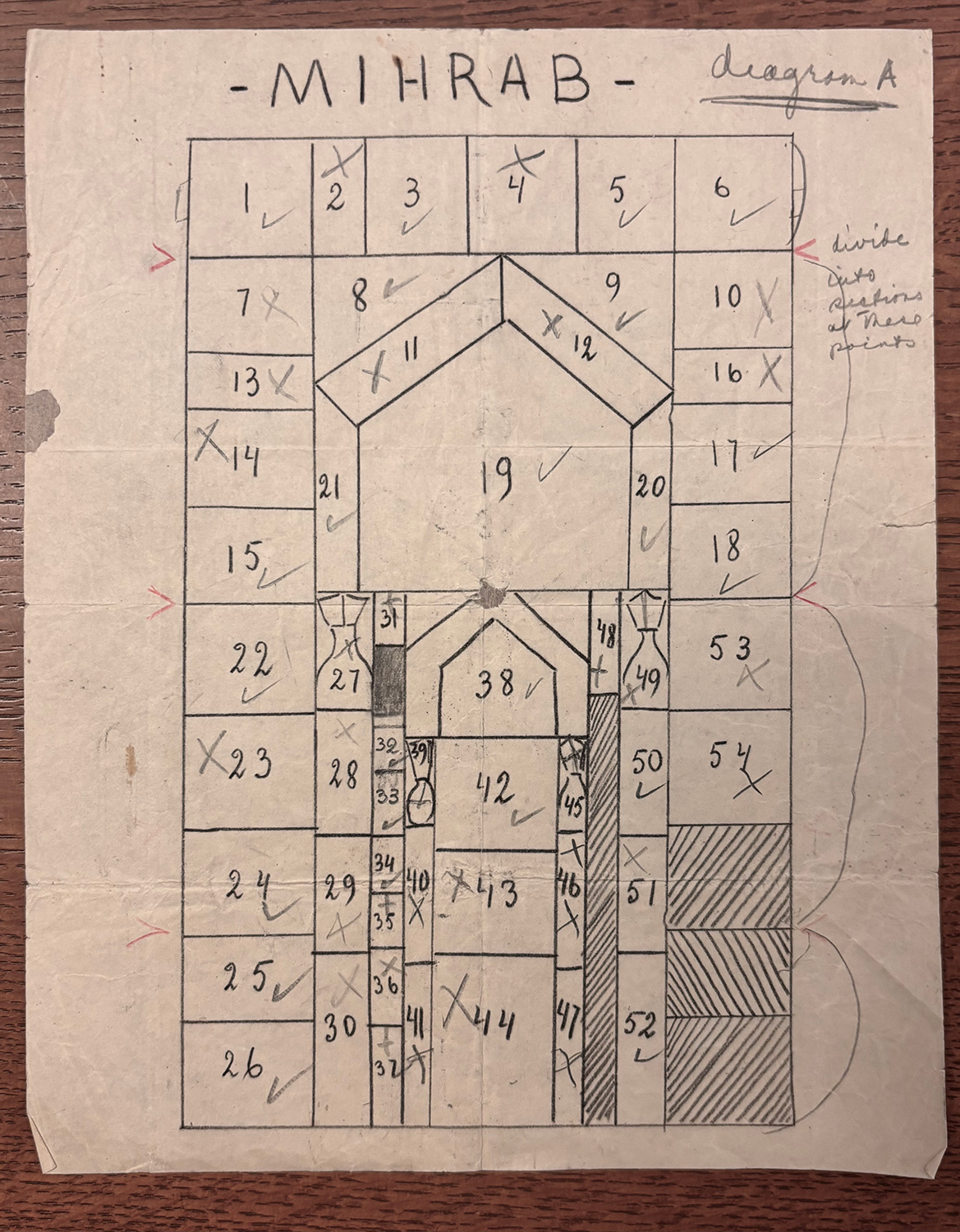

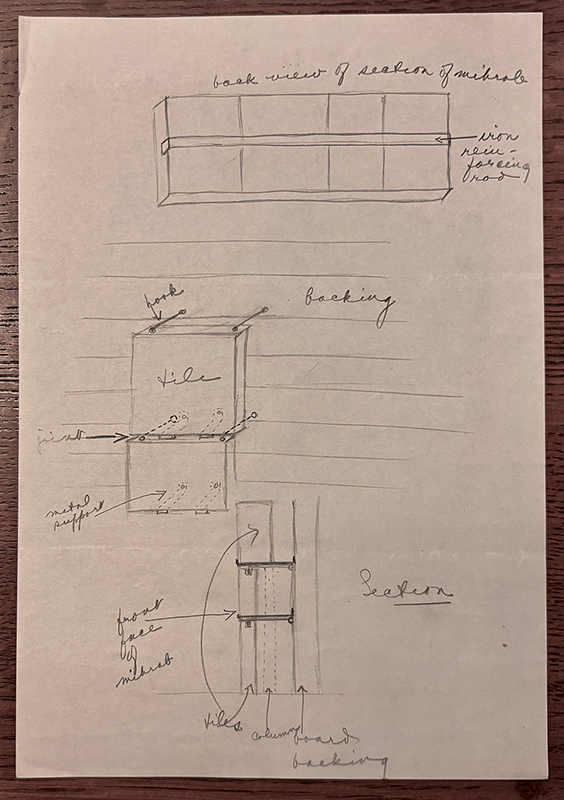

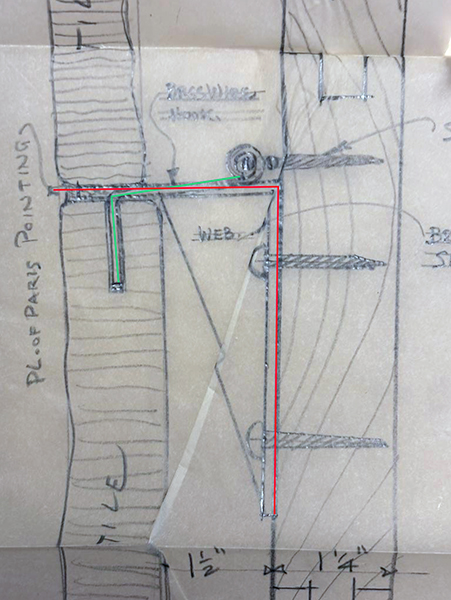

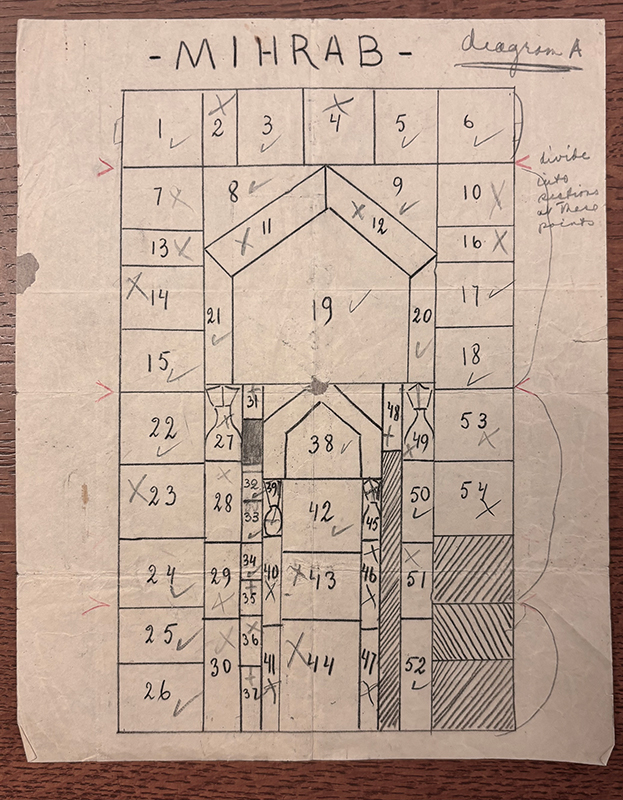

A few days later, Mary Crane sends Duke a 3-page letter and several drawings and diagrams outlining the mihrab’s installation (fig. 181). She emphasizes the necessity of leaving some space around the top and sides of the mihrab: “The recessed niche into which it is placed should be wide enough and high enough to leave about 3” of free space at each side and a little more than that at the top if possible” (first page of the letter, far left in fig. 181).206 She then mentions that the mounting system would ideally allow for quick dismantling and anticipate climactic concerns like dampness and earthquakes. She provides the following instructions: nail a wood backing or scaffolding to the wall (figs. 182–183); attach each tile to this backing, leaving about 5 inches between the backs of the tiles and the wood backing; use plaster to fill the joints between the tiles; and finally, for the missing tiles, use seasoned wood painted a neutral color, as opposed to the grey of the New York exhibition.

Crane provides explicit directions, accompanied by drawings, for how to mount each of the fifty-four tiles to the wood backing, effectively a curtain wall (fig. 184). Each tile has at least two small holes on its top edge, and copper tubes are to be inserted into them, sealed with cement, and attached to the backing. She concludes, “This method secures the top of each piece of tile so that it can’t fall forward.” For the bottom, what she describes as “the most essential element in the installation,” each tile is to be supported by two iron or steel supports “extending out like small arms from the board backing.” Finally, the joints are to be filled with plaster of Paris, not cement.

Drew Baker soon produces a detailed drawing of the mounting system (fig. 185). This method was entirely foreign to the original one, wherein individual tiles were affixed to the qibla wall of the tomb using mortar. It also left a permanent mark on each tile—the holes in the top for securing the brass hooks. It is probable that this system had been developed during one of the mihrab’s many earlier installations while in Kevorkian’s possession.

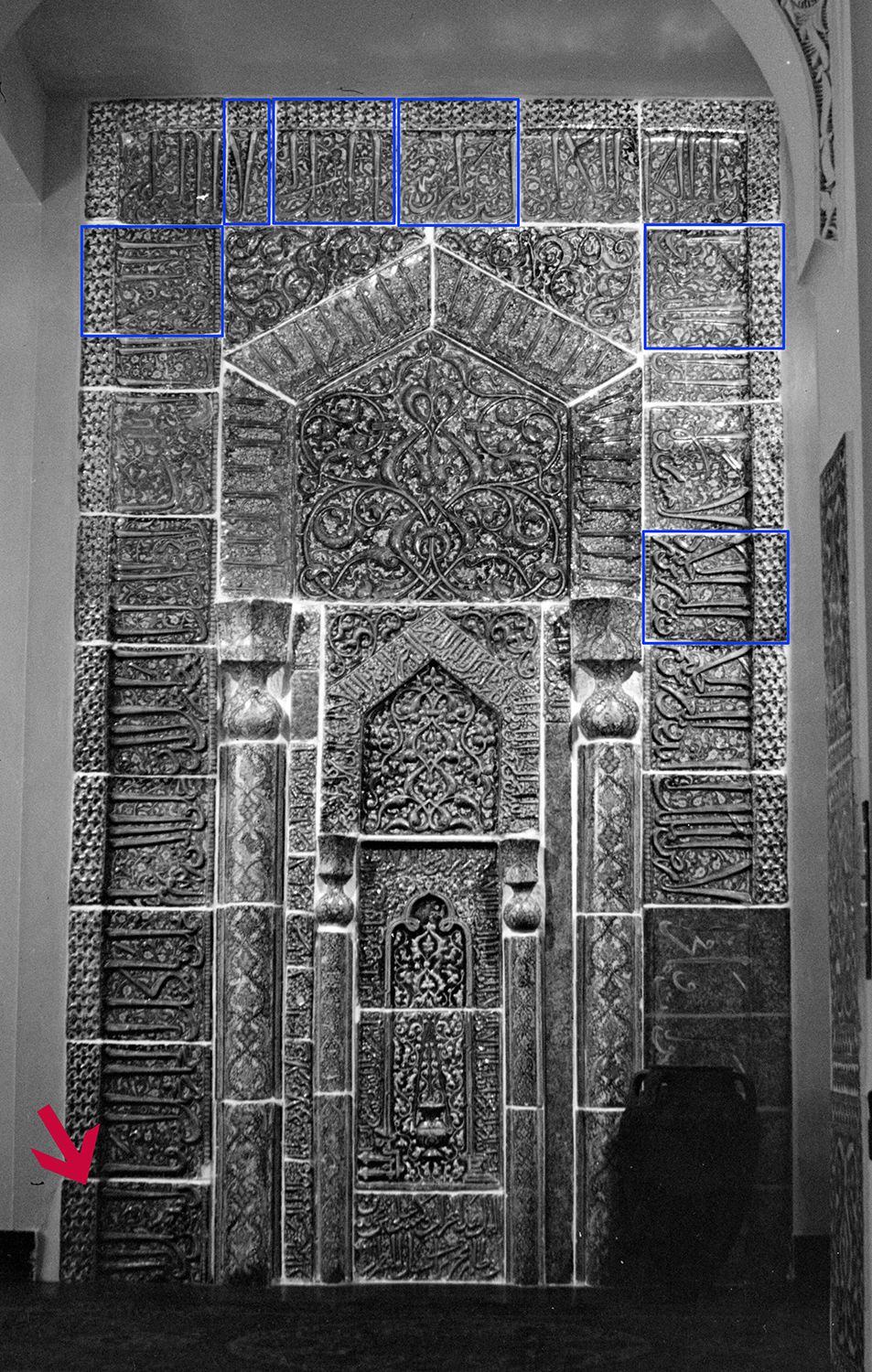

One of Crane’s diagrams shows each of the tiles identified by a number, a guide that presumably corresponded to numbers written on the backs of the tiles (fig. 186).207 At least one of the tiles—the thin example with ضلا, marked number 2—is in the wrong place. This tile was also mispositioned in the April 1940 exhibition in New York but correct in Philadelphia the weeks prior (see fig. 164). If a correct diagram had been provided, perhaps this mistake could have been avoided.

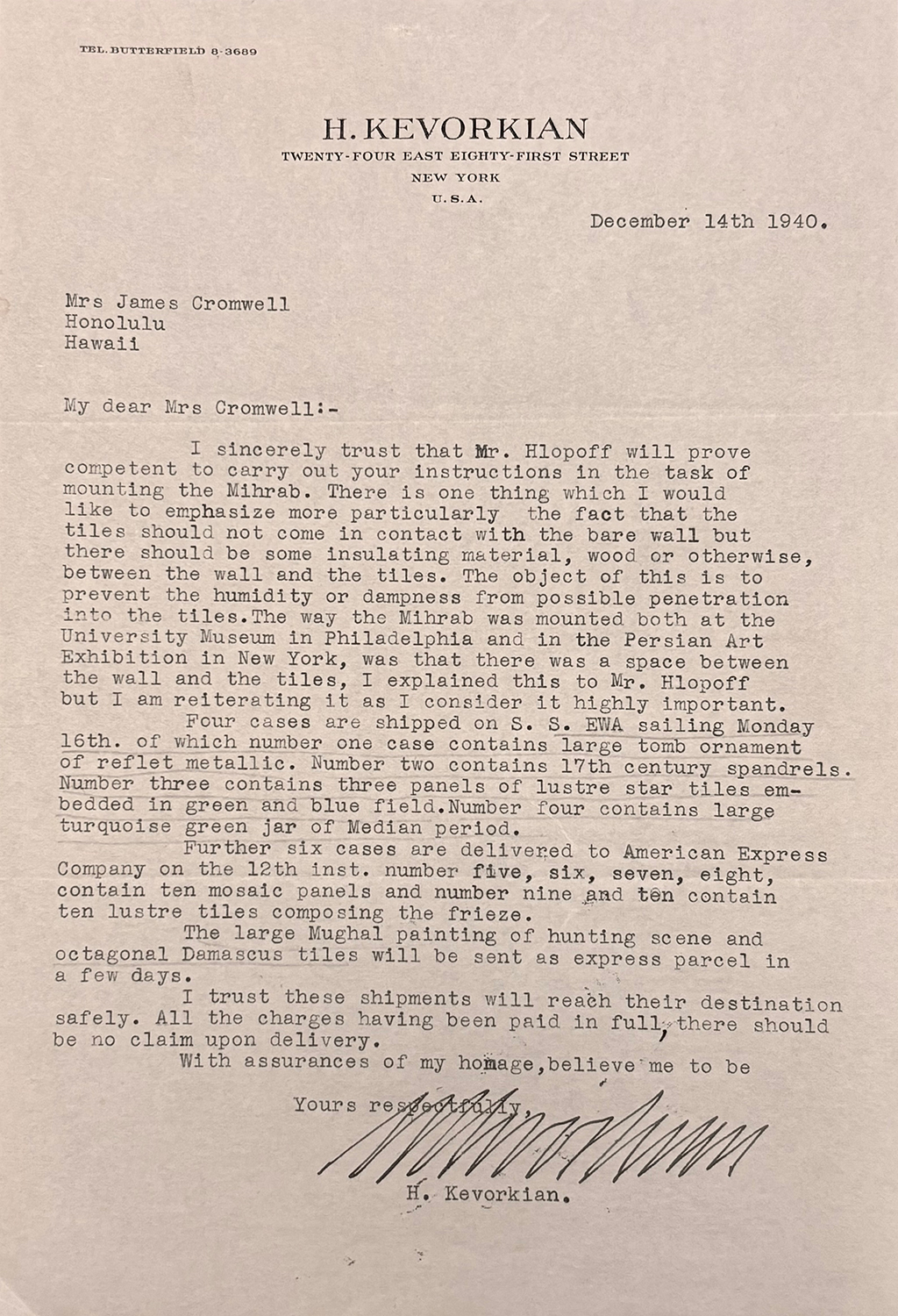

On 14 December, Kevorkian writes to Duke and emphasizes one aspect of the installation that he finds very important: the need to have space between the tiles and wall and some sort of insulating material, like wood, to prevent humidity and dampness (fig. 188). He mentions that the earlier installations in Philadelphia and New York had followed this method and notes that one “Mr. Hlofpoff” will supervise the process in Honolulu.208

December 1940: Honolulu: Alteration

While the mihrab’s tiles had been jumbled in almost all of its previous displays, the installation in Hawai‘i introduced an unprecedented circumstance. As discussed earlier, the height of the designated area was not sufficient to accommodate the mihrab. To make it fit, it is likely that the last tile in the outer border (no. 26 in fig. 187) was buried approximately 4.3 inches below the floor surface (fig. 191). Only the left side of the mihrab was affected by this situation, because the right side was already missing three tiles, creating enough of a gap to resolve the height constraint. The middle section was also unimpacted, since the row that was originally present between the columns was never added (see fig. 62, left), leaving enough space to adjust.

In the first known photograph of the mihrab installed at Shangri La, the last tile of the border is noticeably shorter than its previous iterations, and later photographs confirm that its inscription (بئس مثل القوم) now ends in the middle of the final word (القوم). In all previous photographs of the mihrab, the tile clearly ends with the full word (fig. 192). Although this lower section of the mihrab is not visible in Dieulafoy’s 1881 photograph, Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh’s transcription of the inscription in 1876 confirms that these were the final words—and hence the final tile—when the mihrab was in situ in the emamzadeh209.

The decision to partially bury the last tile of the mihrab, rather than adjust the height of the ceiling, reveals a striking disregard for the mihrab’s historical significance and physical integrity. It not only avoided structural solutions to the ceiling proposed by architect Drew Baker (see fig. 173) but also ignored the basic requirements for proper installation emphasized by agent Mary Crane—namely, to leave some space (see fig. 181). The result was that a three-year-old building was prioritized over a seven-hundred-year-old masterpiece. In none of its previous five photographed installations was the mihrab’s height so significantly compromised and the ensemble squeezed into a space. This decision not only disrupted the original composition of the tiles but also compromised the integrity of the sacred text by burying letters in the final word.

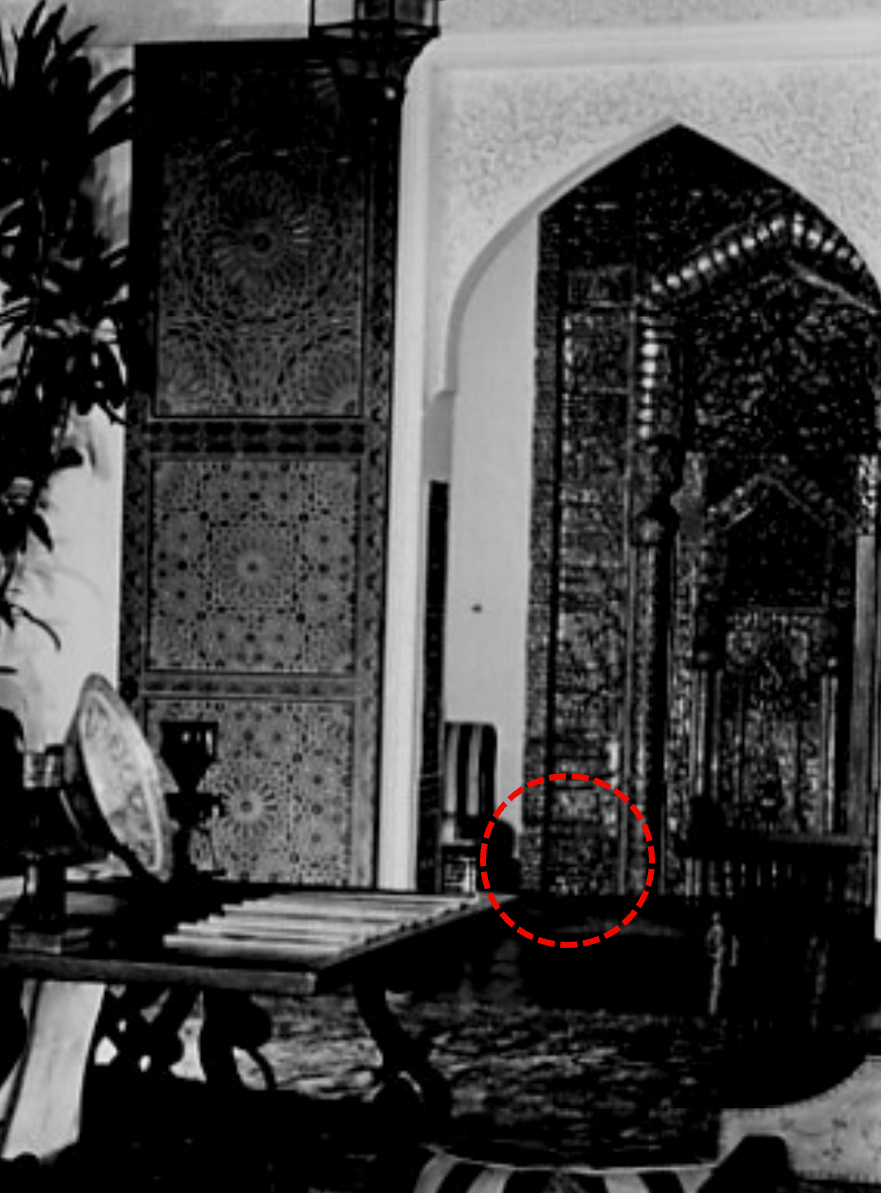

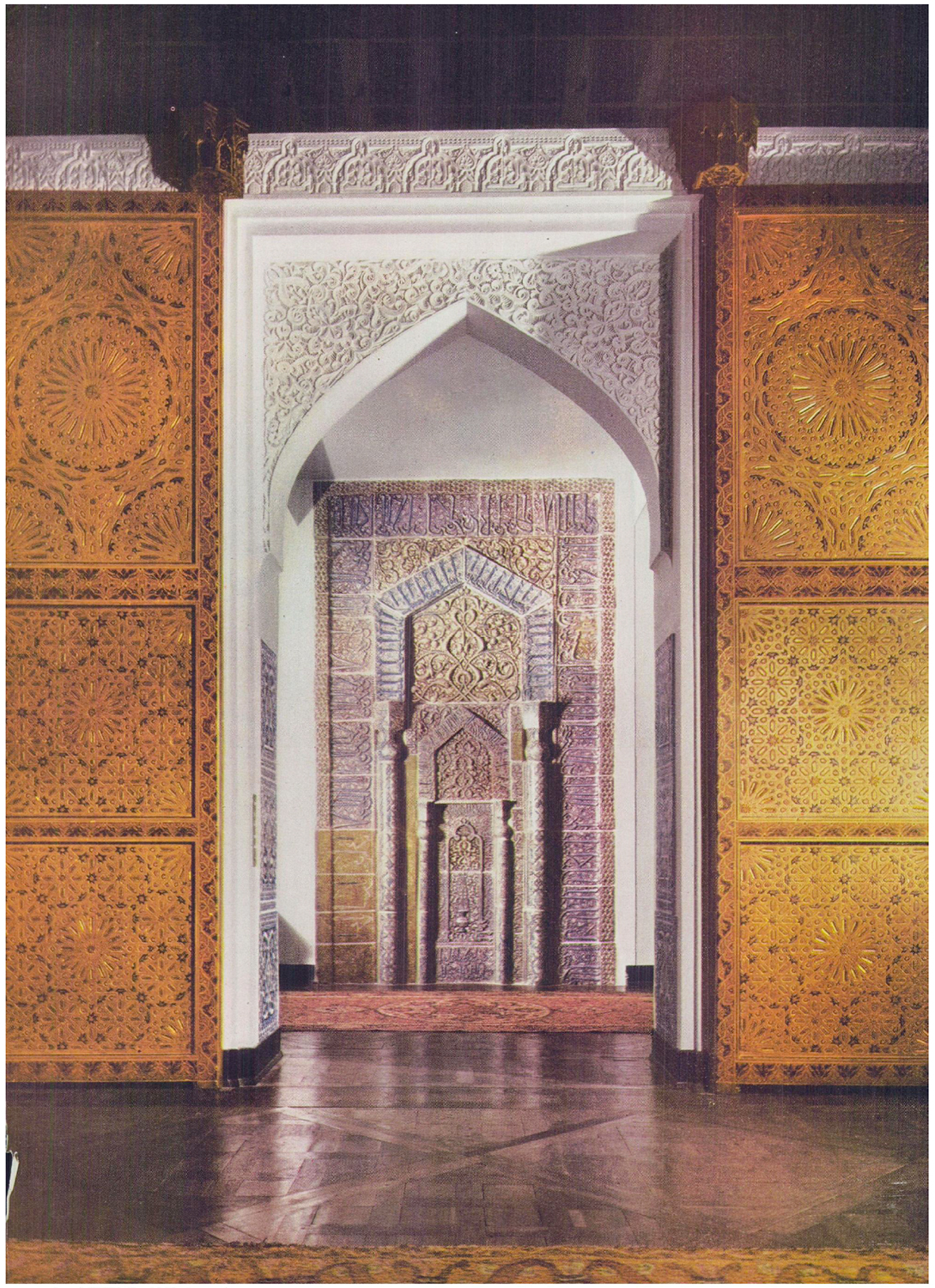

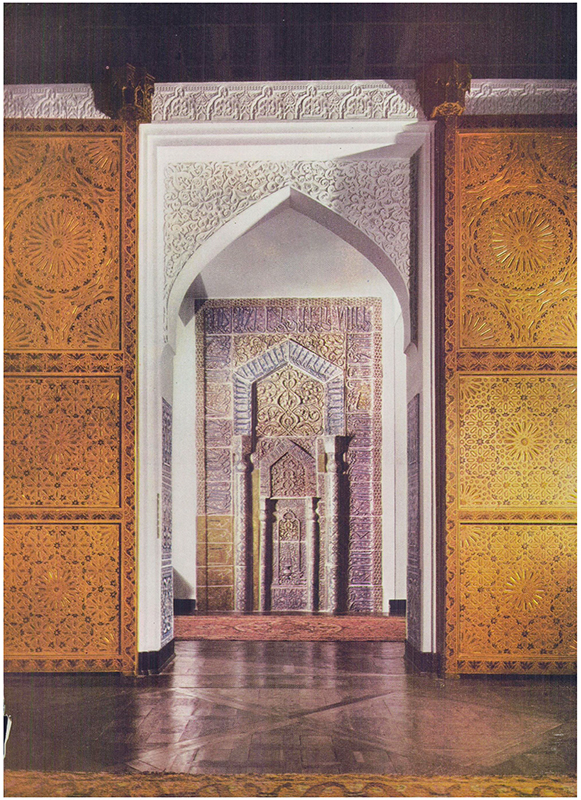

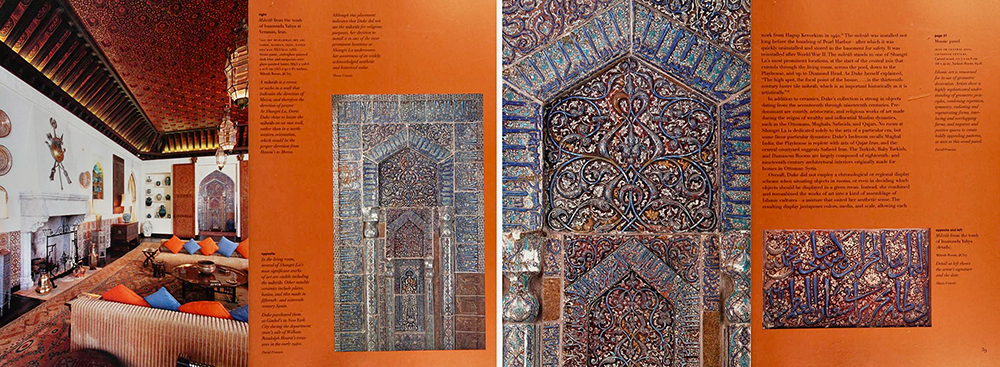

December 1940: Honolulu: Aestheticization

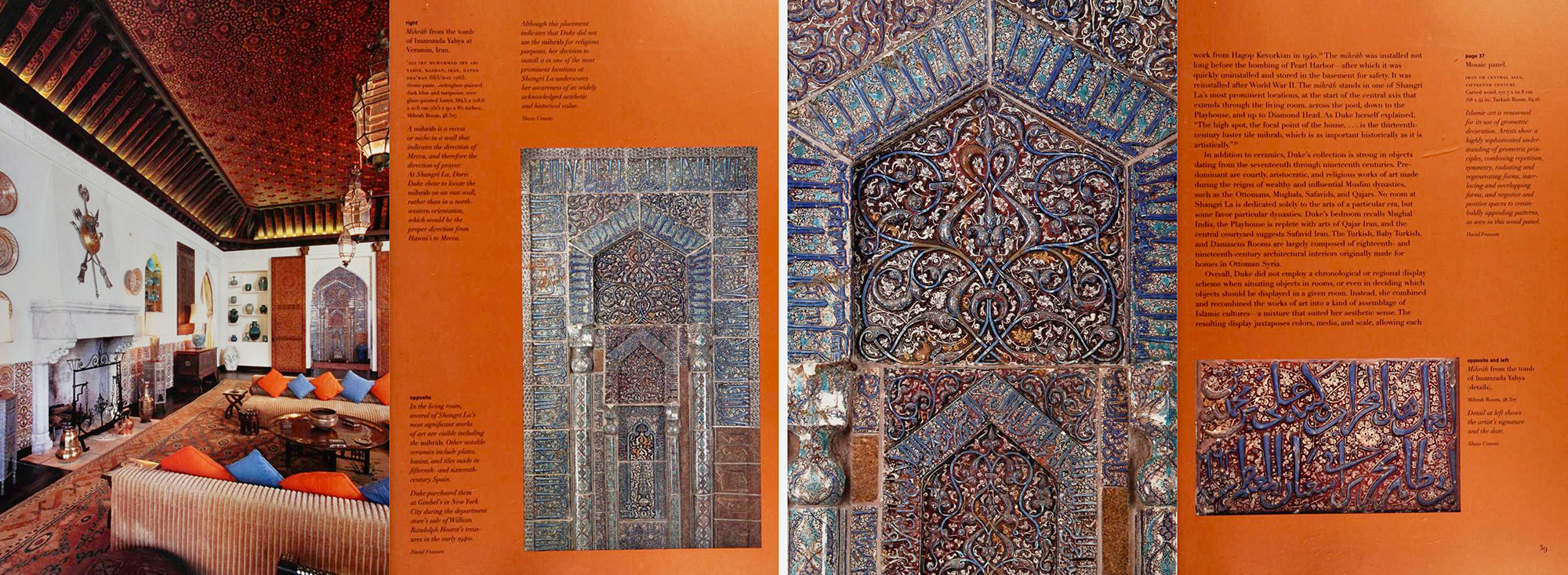

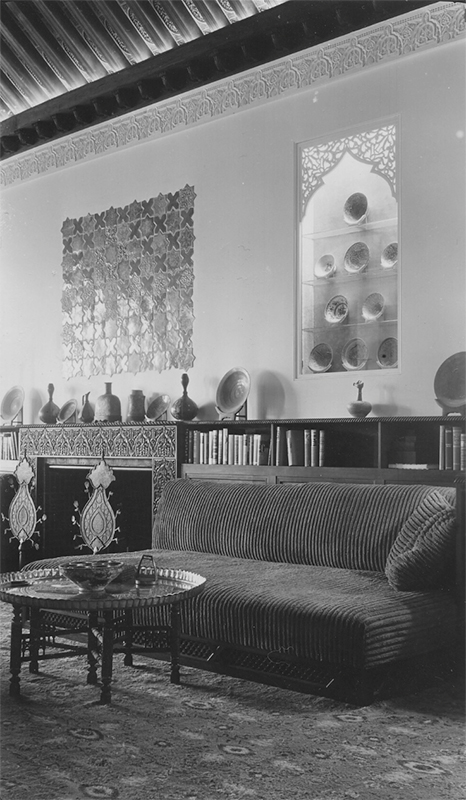

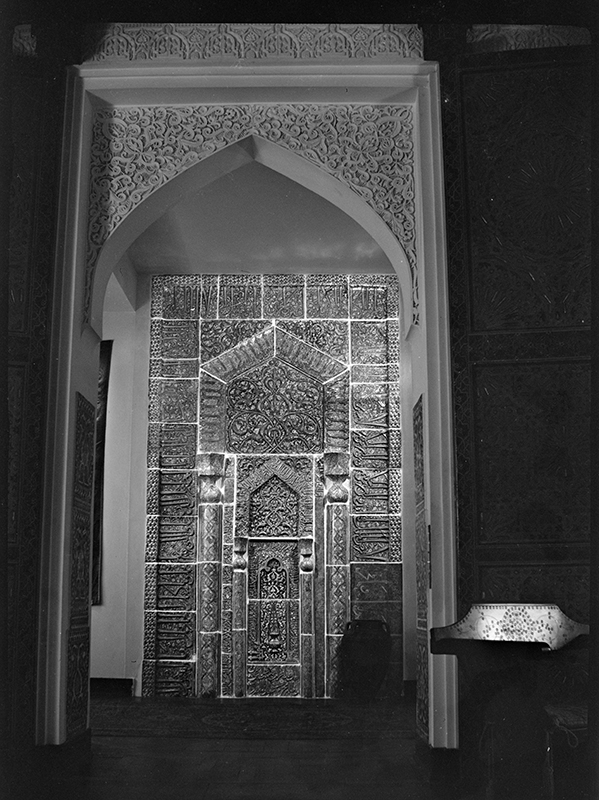

By late December, the mihrab is installed in the space previously home to the Guanyin, now the ‘Mihrab Room’ (fig. 193).210 The missing tiles in the lower right remain empty, but a line seems to indicate the general shape of at least one tile (fig. 194). In this new domestic setting, the mihrab is framed by the custom-made Moroccan stucco spandrel and wooden doors and surrounded by an eclectic mélange of materials, including a large sixteenth-century Spanish (Cuenca) carpet, couches and wood furniture, upholsteries and curtains by American textile artist Dorothy Liebes, and large potted plants.

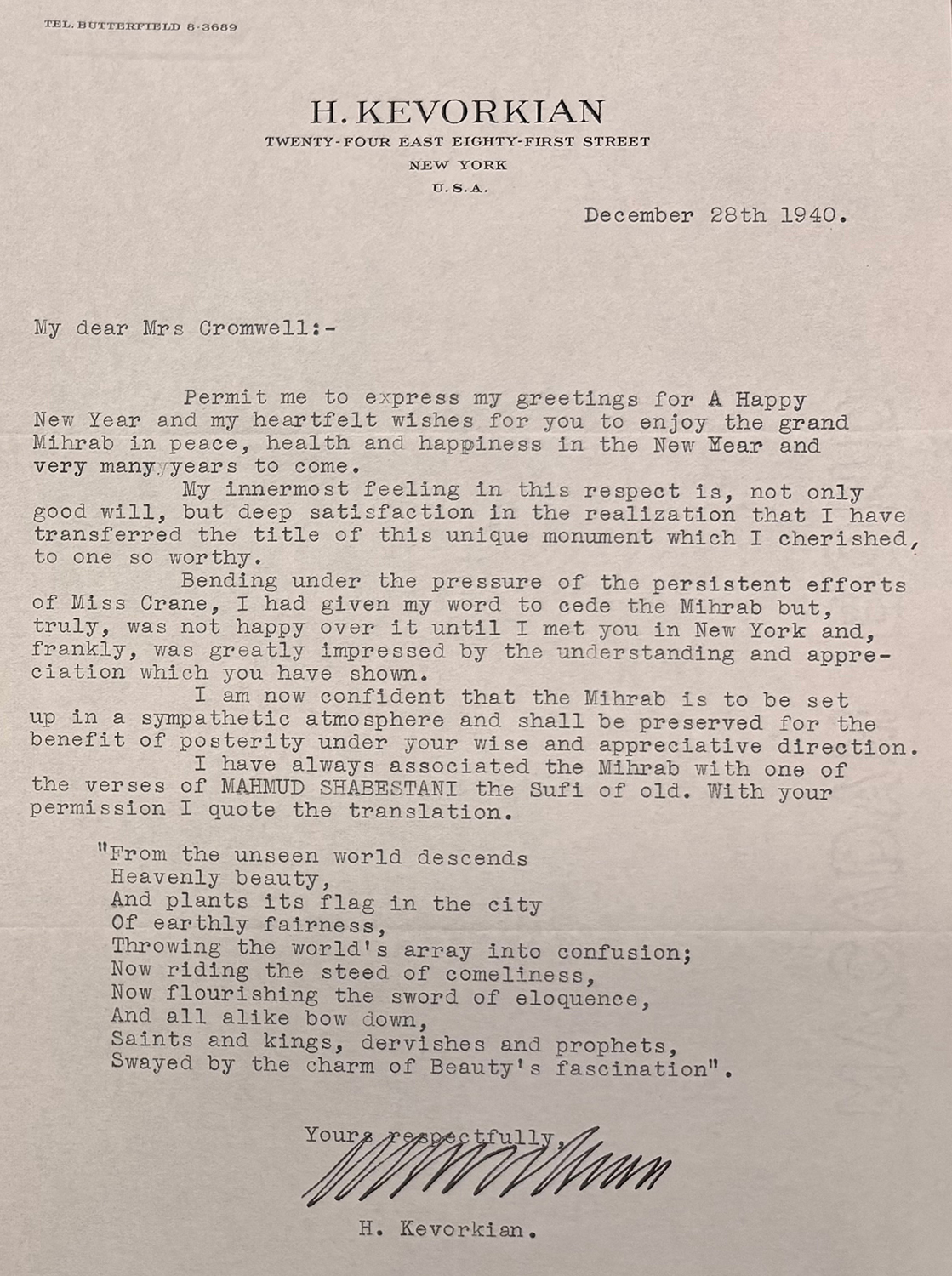

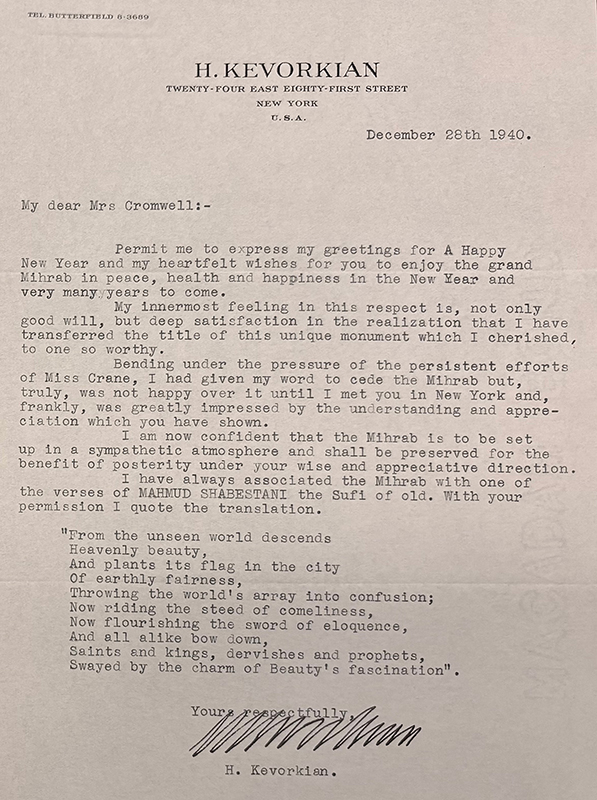

At the end of December, Kevorkian sends Duke a letter wishing her a happy New Year. He expresses his happiness about the sale and his “deep satisfaction in the realization that I have transferred the title of this unique monument which I cherished, to one so worthy.” He mentions Crane’s instrumental role in the negotiation and his meeting of Duke herself in New York, presumably in spring 1940 during the Persian art exhibition (fig. 195). He is “confident that the Mihrab is to be set up in a sympathetic atmosphere and shall be preserved for the benefit of posterity” and closes his letter by quoting verses by the Sufi poet Mahmud Shabestari (d. 1340).

“I am now confident that the Mihrab is to be set up in a sympathetic atmosphere and shall be preserved for the benefit of posterity under your wise and appreciative direction”

Kevorkian’s comments on preservation for “the benefit of posterity” are notable, given that he knew that the mihrab was entering a private home in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. His early desire to see the mihrab enter a public museum was ultimately superseded by a private collector’s ability to pay his full asking price. The dealer had spent twenty-seven years trying to sell the mihrab and was increasingly concerned by the war, which was looming closer to the United States. He had peddled the mihrab to several American collectors and museum directors (Charles Lang Freer, George B. Gordon, Horace H. F. Jayne, Maurice Dimand), displayed it in at least five contexts between New York, Philadelphia, and London, and shipped it across the Atlantic five times, all while sometimes being pressured by his London partner Debenhams.

After over six hundred years in the tomb of Yahya b. ʿAli (Emamzadeh Yahya) and forty years on the international art market, the mihrab enters the deliberately secluded Hawai‘ian home of a twenty-eight-year-old American heiress. For the next fifty-three years, this invaluable example of Iranian religious, architectural, and cultural heritage will only be visible in person to Duke and her privileged guests, friends, and staff. It will take sixty-two years for it to be available for public visitation.

Spring 1941: Honolulu

In spring 1941, Crane provides a “mihrab frieze reconstruction drawing” of the inscription missing from the lower right, and molded and painted faux tiles are soon inserted into the ensemble (figs. 196–197).211 This inscriptional filler is a fairly accurate presentation of the opening words of sura al-Jumuʿah, especially as compared to the fillers in 1918 Philadelphia and 1931 London, but Crane made some errors. The inscription did not begin with the first word of the verse but rather the basmala. The original inscription was therefore much more compressed than Crane’s generously spaced proposal.

During this time, Crane participates in another major set of acquisitions for Shangri La. In early 1941, she serves as Duke’s buying agent at what she describes as the “Hearst Mad-House,” the sales of the William Randolph Hearst (d. 1951) collection in New York.212 Aware of Duke’s interest in Persian luster, Crane emphasizes that “the Hispano-Moresque lustre plates [large dishes made in fifteenth-sixteenth century Spain] are the finest things in the sale” and buys five pieces. By the end of 1941, Shangri La is home to significant collections of both Persian and Spanish luster. The Spanish luster tiles and dishes are concentrated on the north wall of the living room, hence in close proximity to the mihrab and other Persian luster tiles and vessels. The mixing of Persian and Spanish luster traditions reflects an aesthetic logic to display that prioritizes visual and surface effect over historical context and meaning.

May 1941: Honolulu

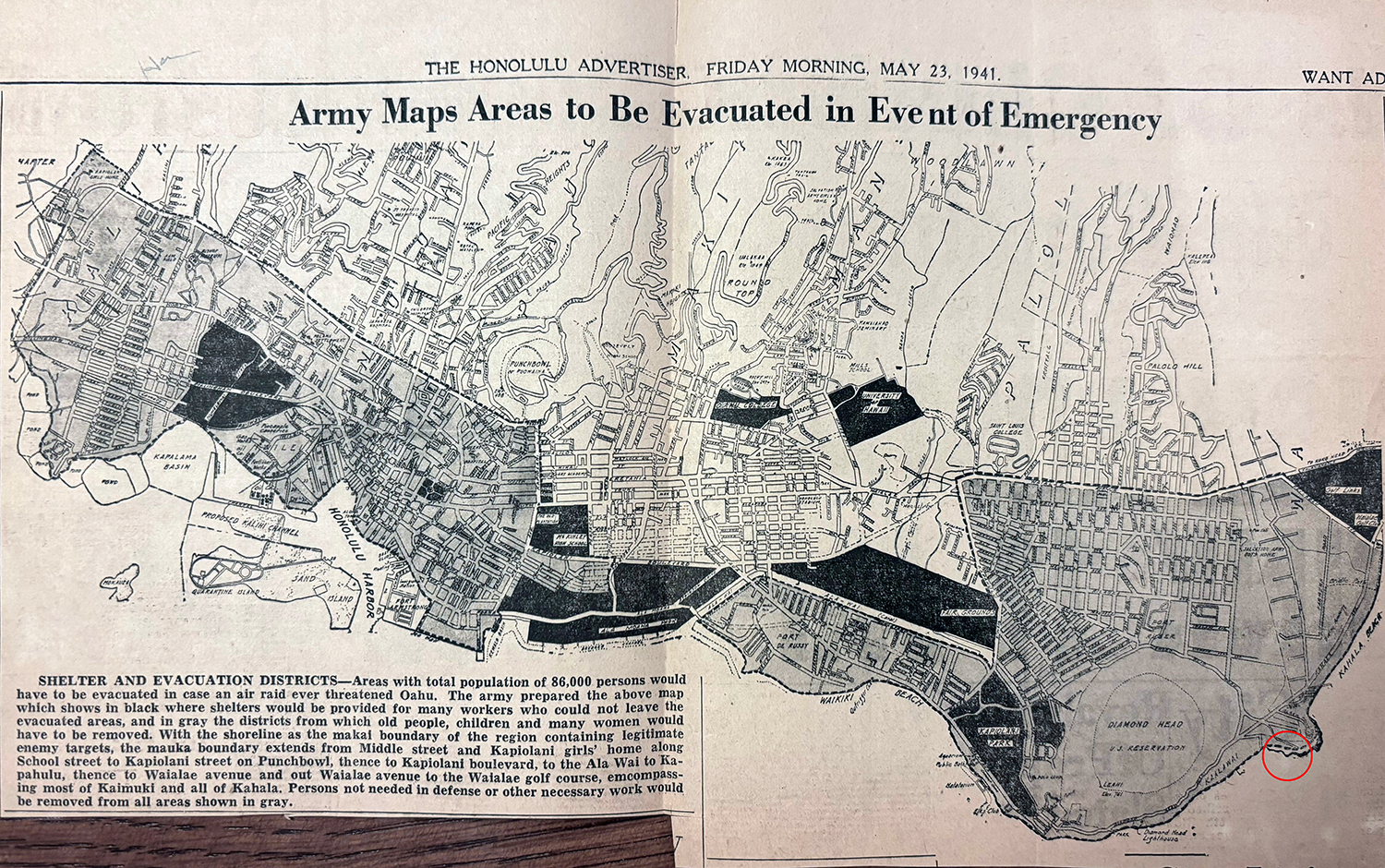

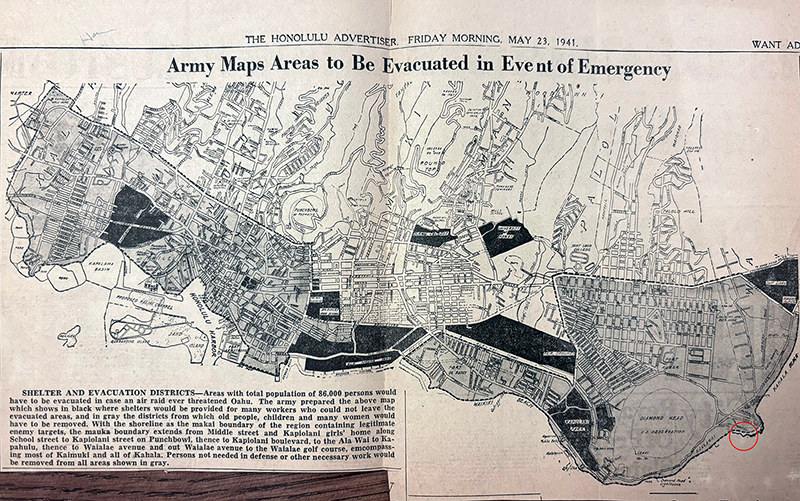

Doris Duke leaves Hawai‘i in early May as the threat of war looms. Shangri La is left under the watch of property manager Commander R. W. Swearingen (Waldo), a retired naval officer who oversees all activities, supervises the staff, and regularly reports to Duke and secretary Marian Paschal. On 28 May, Swearingen writes that people on the island are learning first aid and carrying provisions in their bags. Shangri La is in the evacuation zone, and he sends Duke a newspaper clipping (fig. 198).

7 December 1941: Honolulu

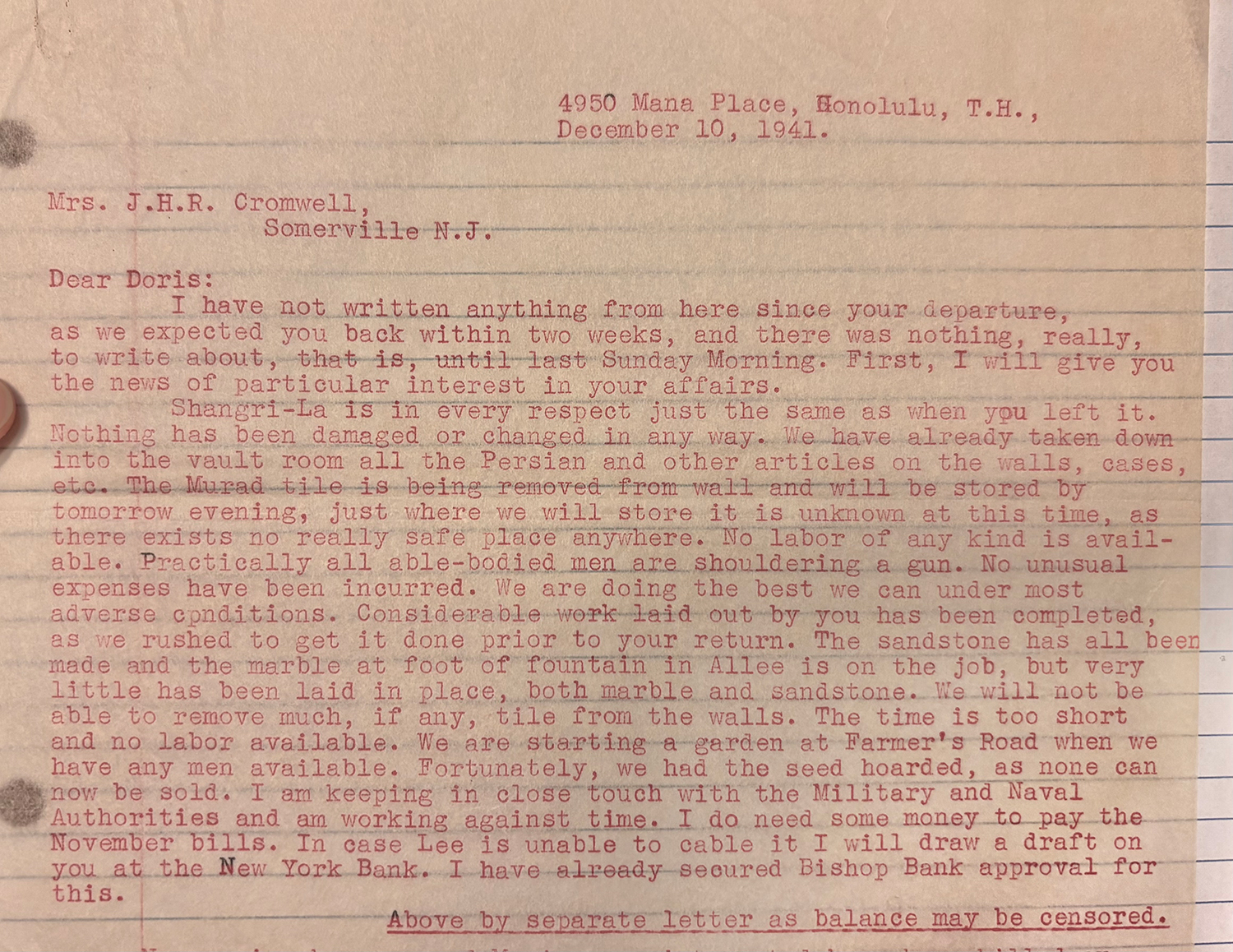

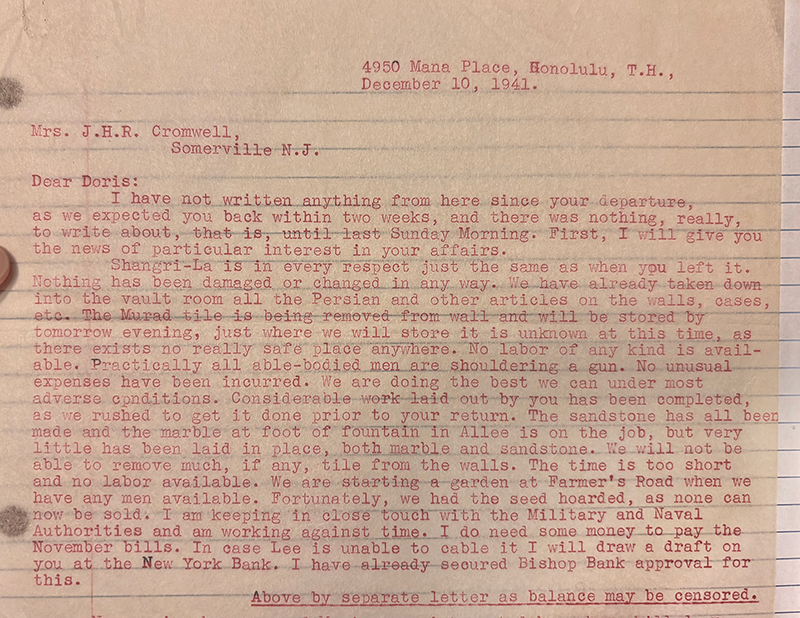

Pearl Harbor—a U.S. naval base located about fifteen miles northwest of Shangri La (map)—is attacked by Japan, and the United States enters the war (fig. 199). Three days after the attack, Swearingen sends news (fig. 200):

Shangri-La is in every respect just the same as when you left it. Nothing has been damaged or changed in any way. We have already taken down into the vault room all the Persian and other articles on the walls, cases, etc. The Murad [sic] tile is being removed from wall and will be stored by tomorrow evening, just where we will store it is unknown at this time, as there exists no really safe place anywhere.

On 16 December, he writes, “The Murad [sic] tiles has been removed from walls and is now stored in the vault with the other Persian articles and the glassware. I know of no safer place at this time.”213

“I know of no safer place at this time”

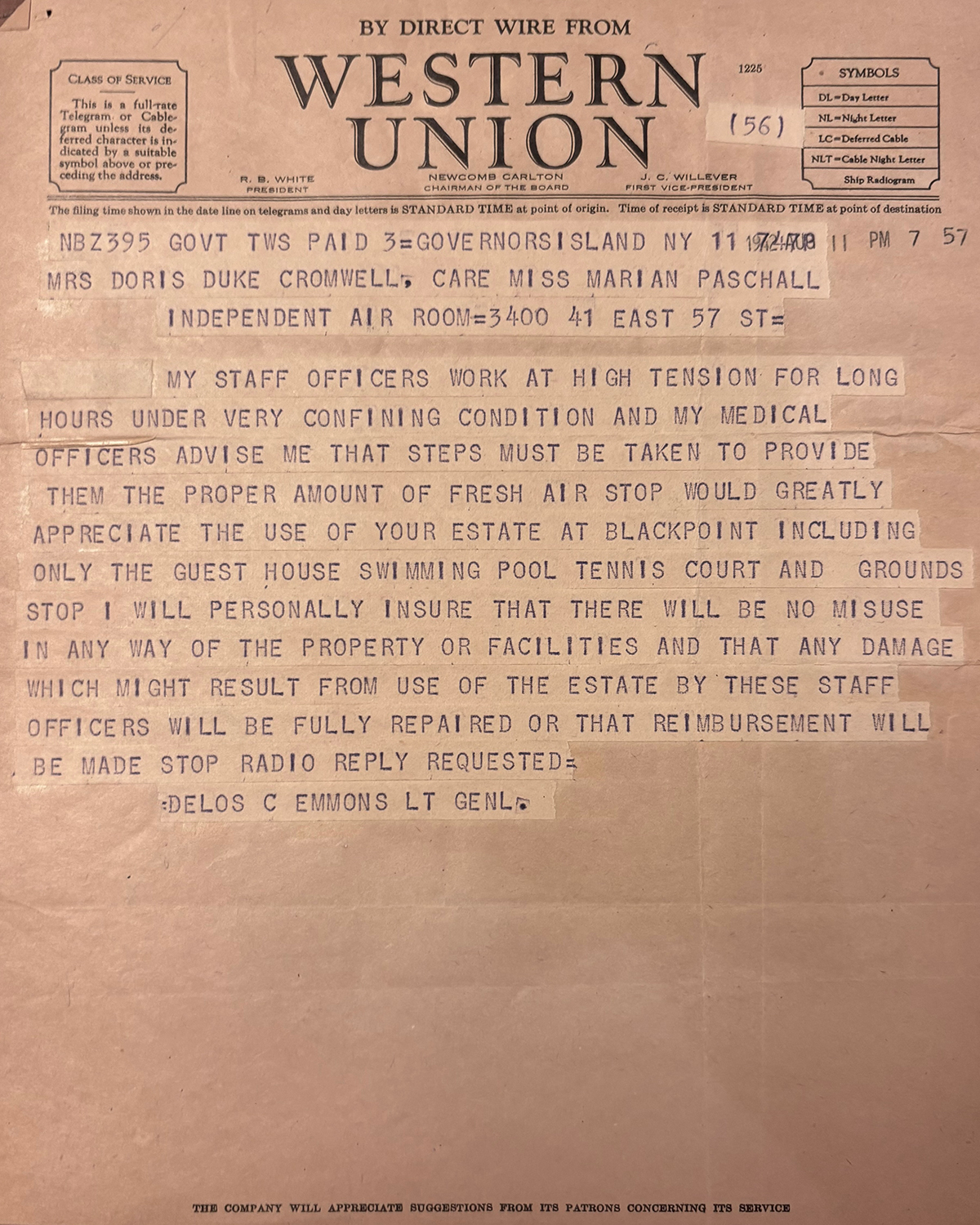

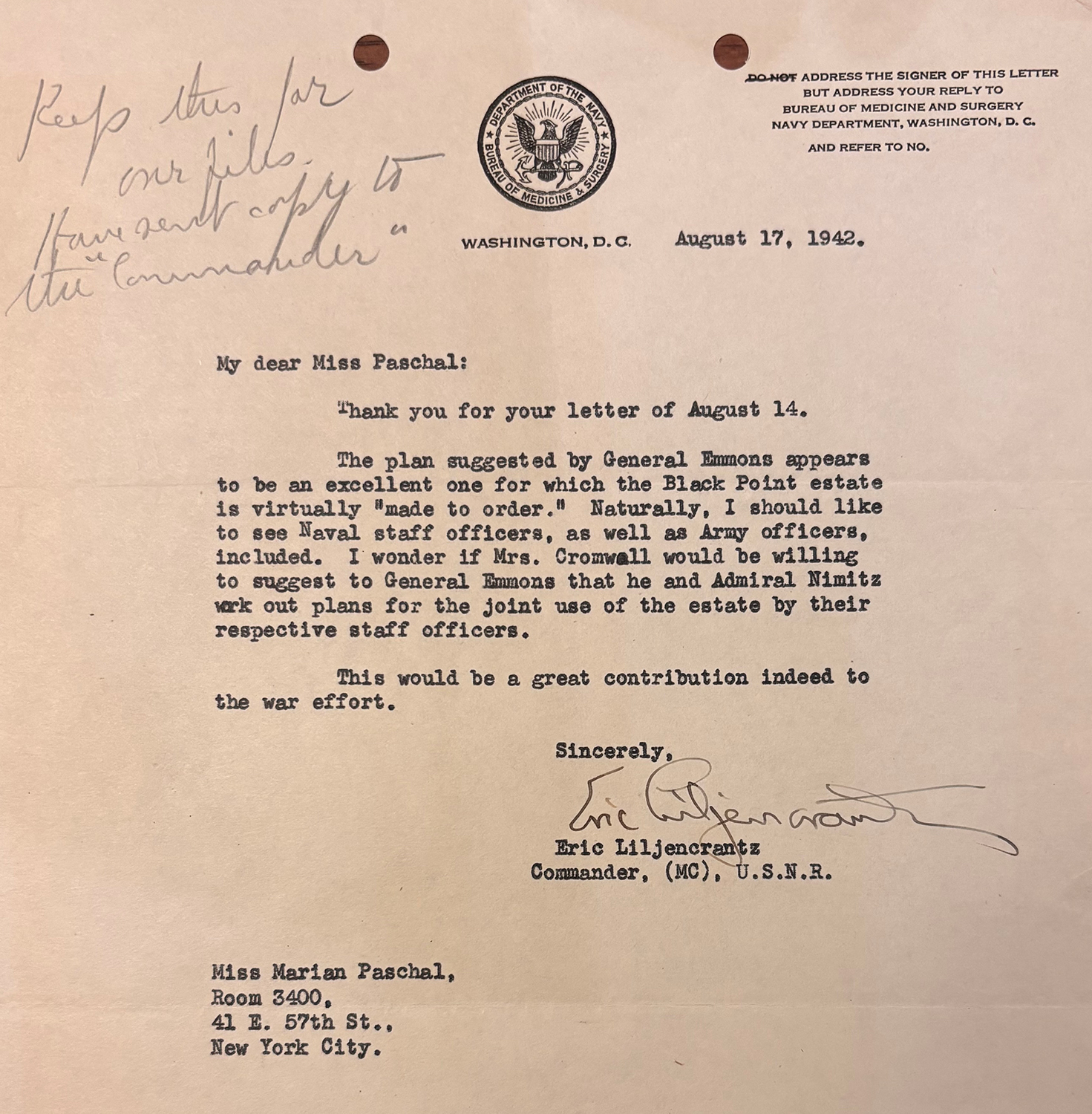

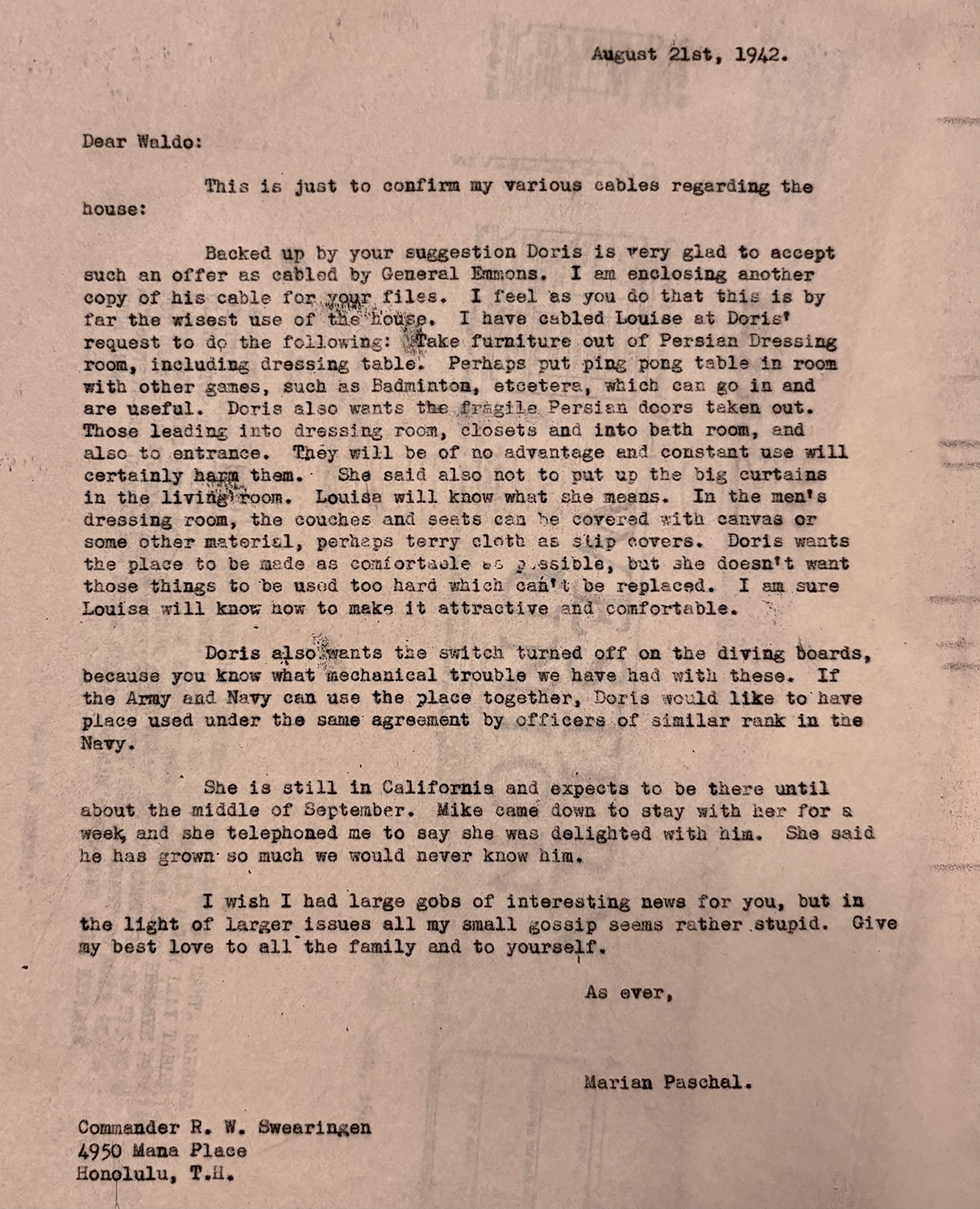

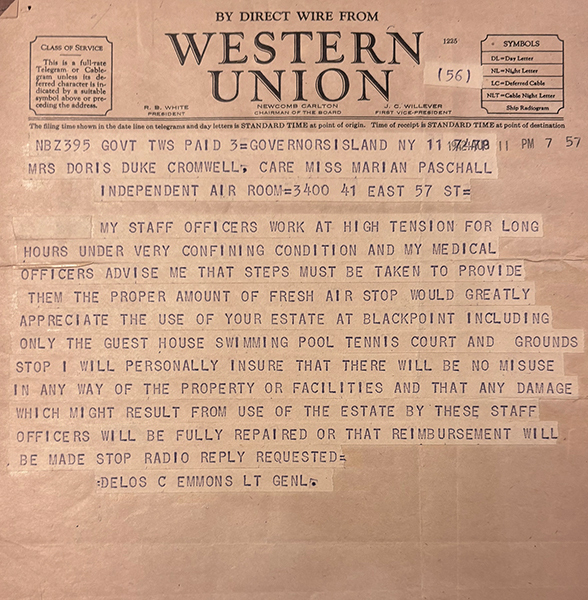

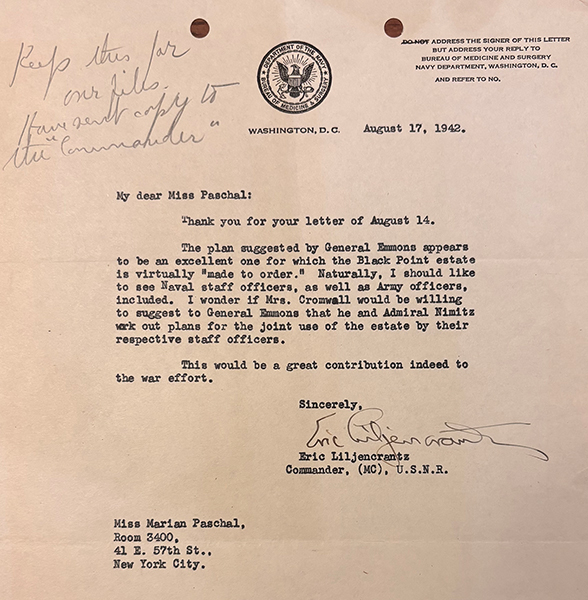

By January 1942, Hawai‘i is under military rule (martial law), and in March, it is suggested that Shangri La be used to support the war effort, perhaps even serve as a hospital.214 Lieutenant General Dellos C. Emmons requests that select areas of the property—mainly the tennis courts, pool, and Playhouse—be made available to staff officers working under tense conditions (fig. 201). His counterpart at the Navy places a similar request, describing Shangri La as “made to order” and Duke’s gesture as a “great contribution indeed to the war effort” (fig. 202). Duke supports the joint use of the estate by the army and navy, with specific conditions. She (via Paschal) instructs Swearington to move certain furnishings and valuables to storage, especially some fragile doors (fig. 203).

During the war, Duke works for the United Seamen’s Service, first in New Orleans and then in Alexandria, Egypt. She also joins the International New Service and is based mainly in Italy (fig. 204).215

1945–46: Honolulu

In August 1945, shortly before the conclusion of the war (2 September 1945), Swearingen inquires about Duke’s return to Hawai‘i and reports on work in progress and required at Shangri La. The list includes landscaping, checking water and electric systems, and reupholstering furnishings used by the military officers. He concludes, “Generally, everything is in fine condition.”216

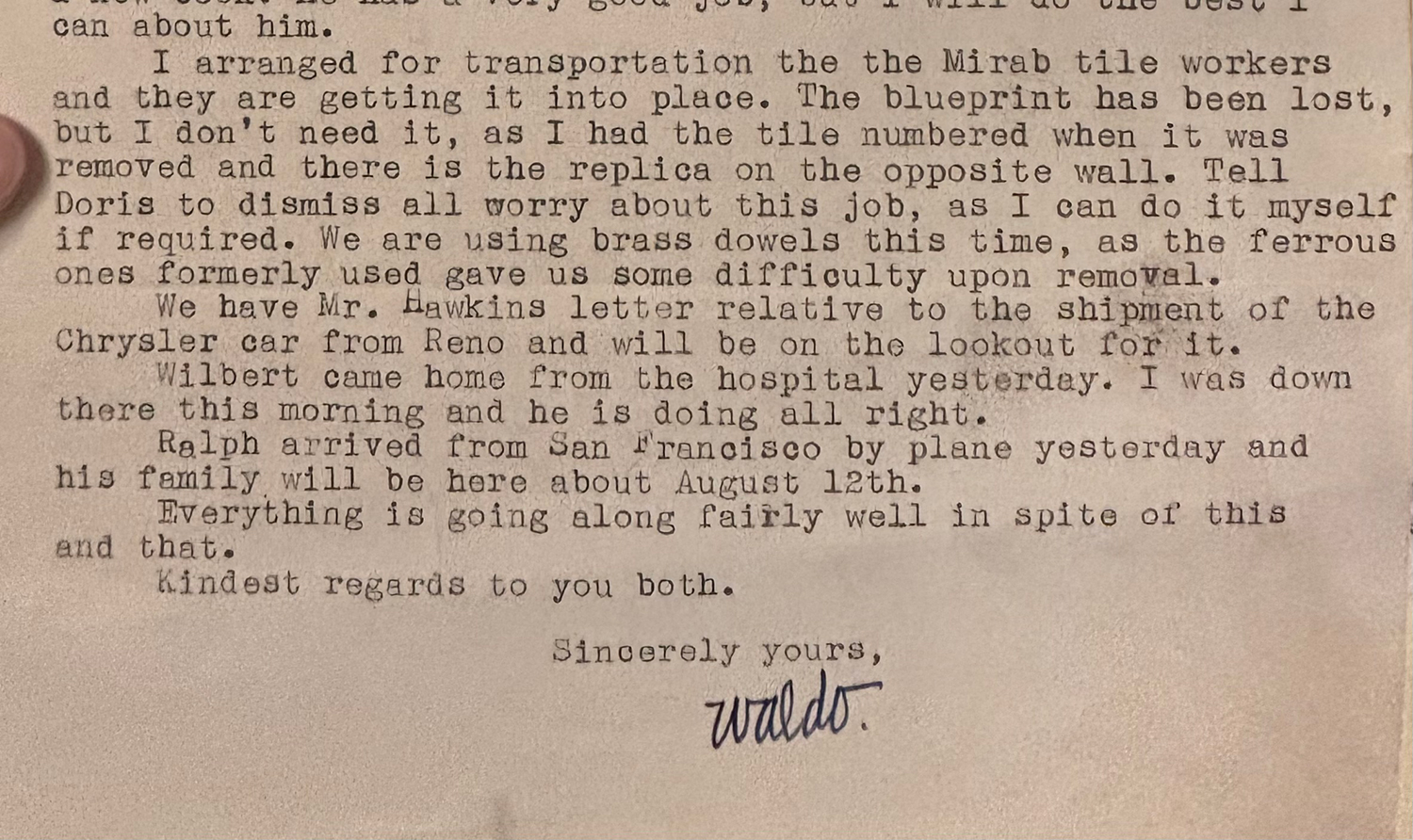

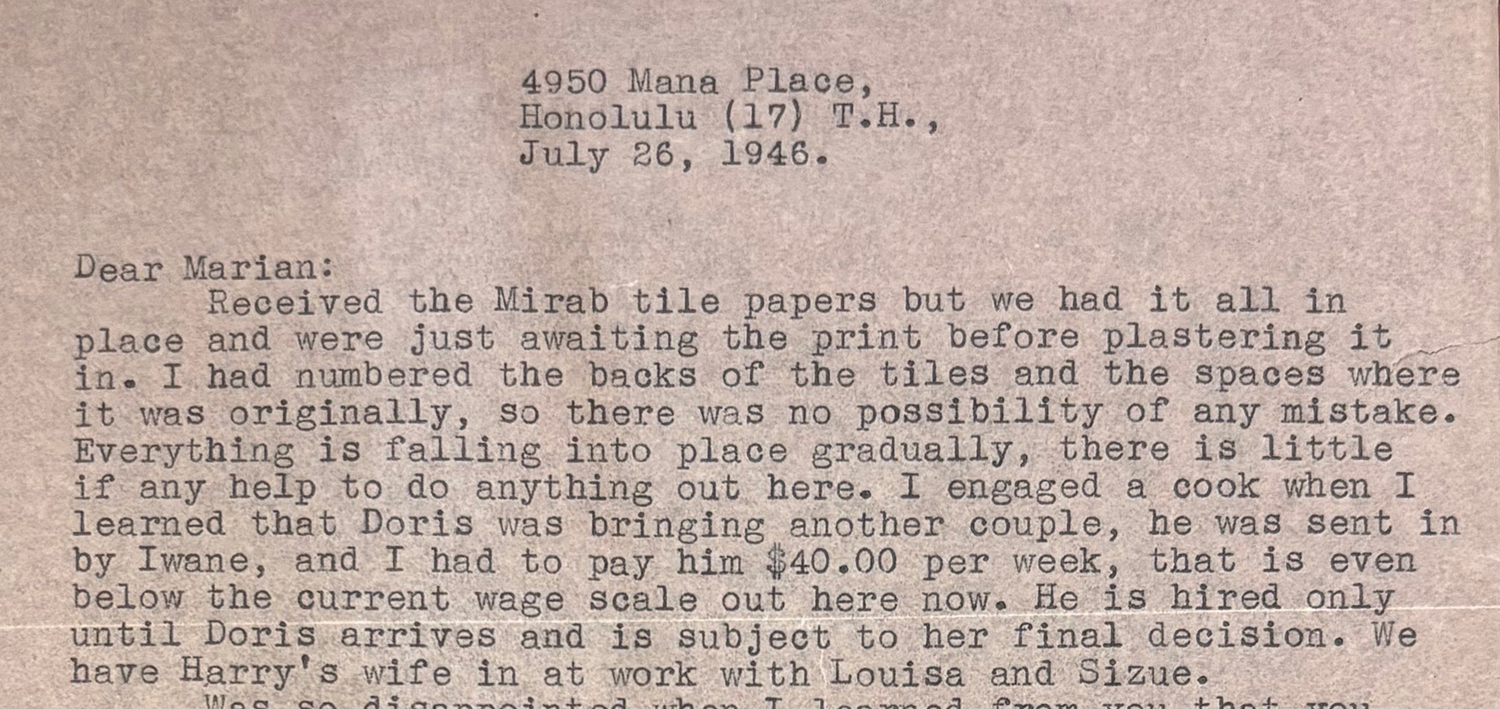

The mihrab is to be reinstalled in advance of Duke’s return. In mid-July 1946, Swearington begins directing this process and asks Marian Paschal to “tell Doris to dismiss all worry about this job, as I can do it myself if required” (fig. 205). He mentions that a blueprint has been lost, but this was not a problem since he had numbered the tiles and “there is a replica on the opposite wall.” He also mentions a change in tools—brass dowels, versus ferrous (iron) ones—as the latter “gave us some difficulty upon removal.” Paschal replies with a photstat of the plan and clarifies that the “piece on the opposite wall is not a replica.”217 On 26 July, Swearingen reports that the mihrab is in place and just requires plaster (fig. 206). He again mentions that he had numbered the backs of the tiles to avoid any mistakes. He concludes, “Everything is falling into place gradually” and ends his letter by describing how people know that Duke is coming. On 30 July, he sends a telegram confirming that “mihab [sic] tile installed.”218

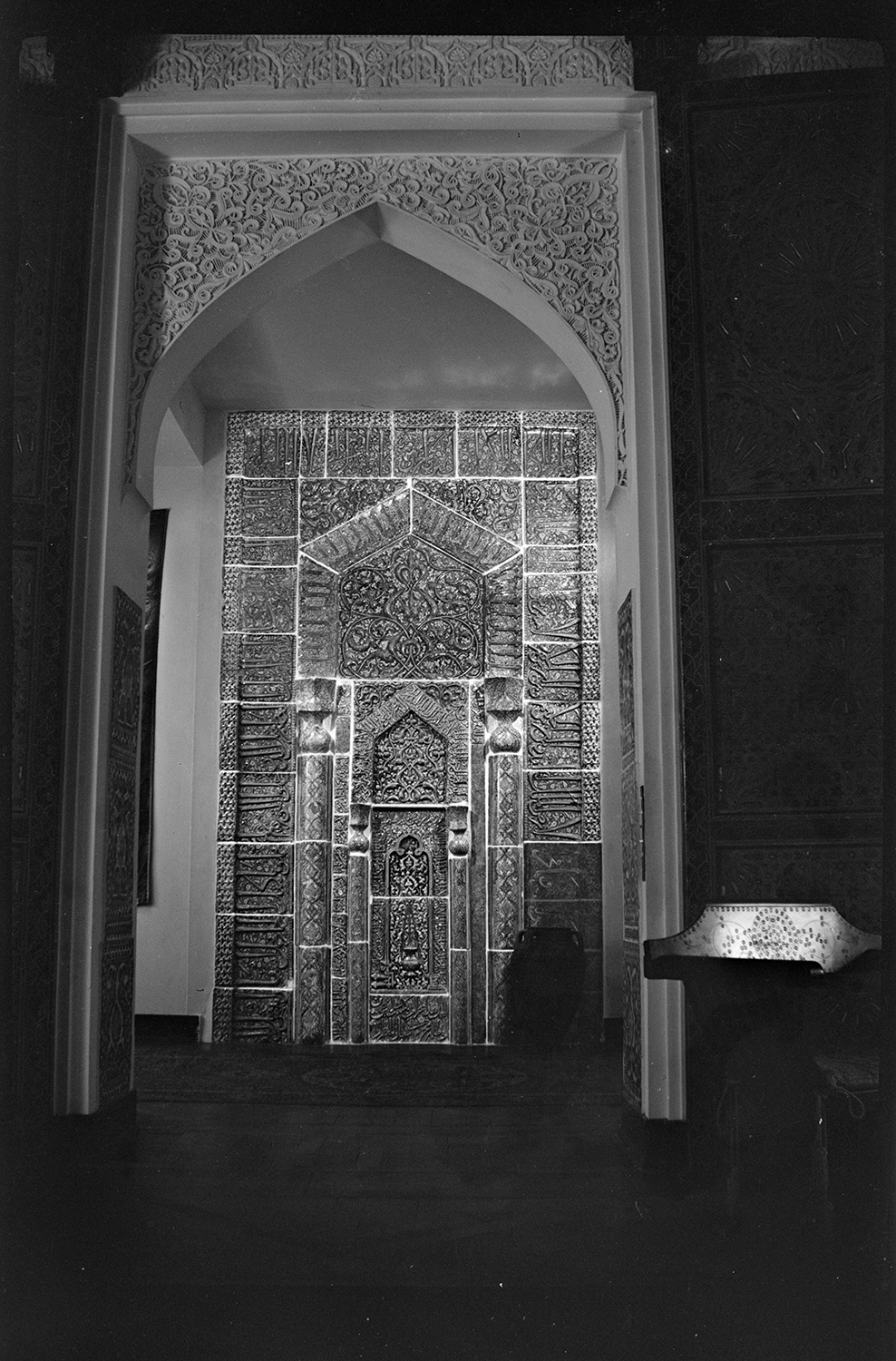

The first known photograph of the reinstalled mihrab shows the full ensemble and is invaluable evidence for understanding its early setting and configuration at Shangri La (fig. 207). A few inches of room are visible on the left and right, but there is very little space on its top edge. The high quality of the nitrate negative sharpens the contrast between the tiles and white plaster and facilitates a close analysis. Six tiles are jumbled (out of place), and the partially buried tile on the lower left is clearly visible (fig. 208). The inscriptional filler outlined by Crane is present in the lower right, and vaguely patterned filler stands in for the many missing tiles in the inner border between the columns. In contrast to the previous installation of the mihrab in New York (see fig. 162), where a candlestick was placed in front of the area of loss in the lower right, a large pot now masks that space.

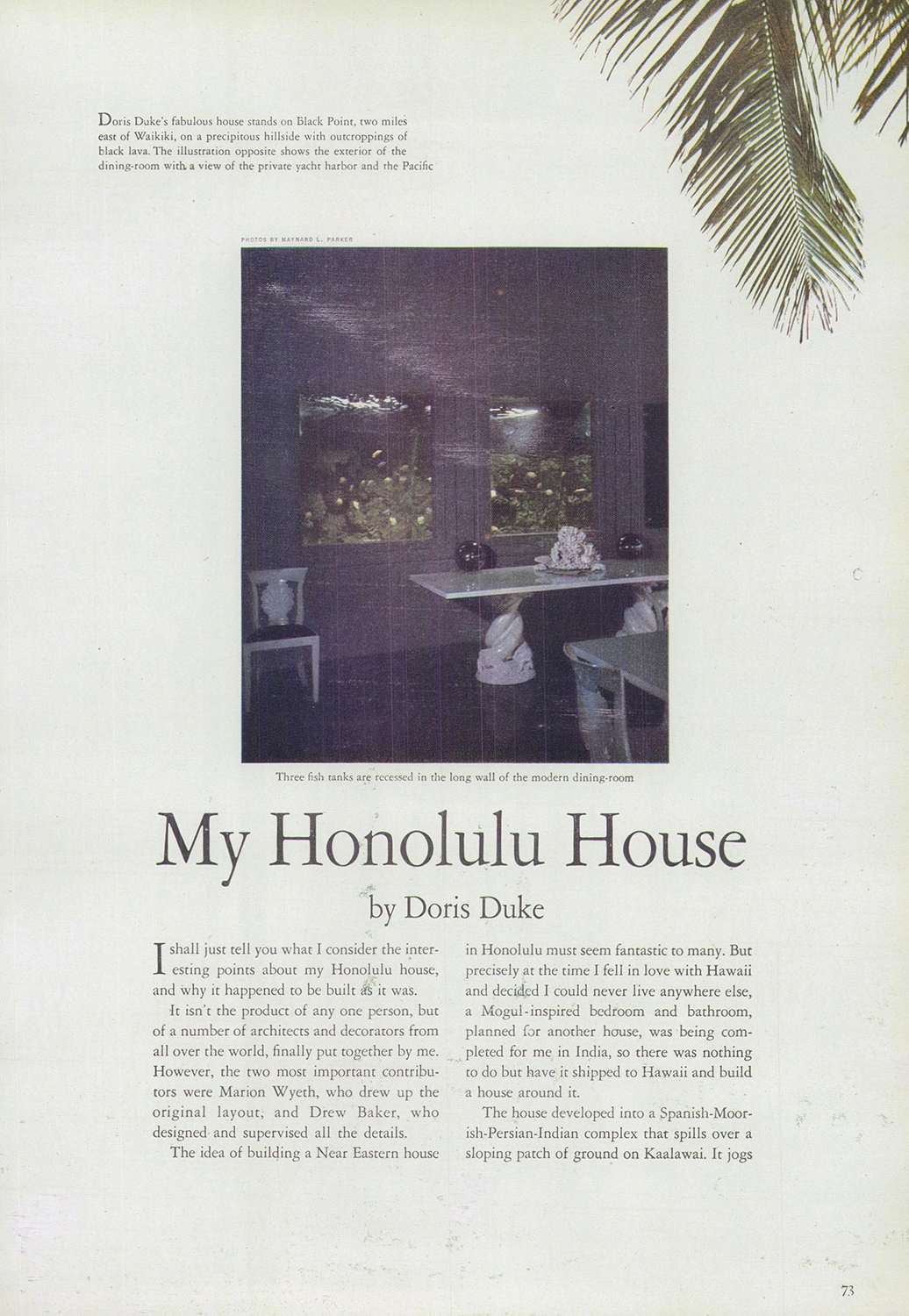

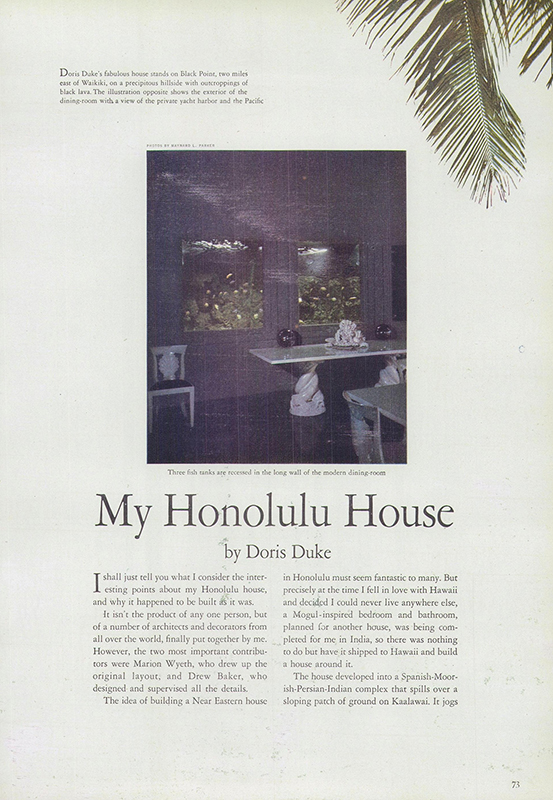

1947: Honolulu

American photographer Maynard Parker (d. 1976) visits Honolulu after the war and photographs Shangri La and other landmarks on the island.219 His color photograph of the mihrab is soon reproduced in Doris Duke’s “My Honolulu House,” one of the few sources available for tapping the collector’s voice (fig. 209). On the mihrab, Duke writes, “The high spot, the focal point of the house, however, is the thirteenth century luster tile mihrab, which is as important historically as it is artistically.”220 This is the first time that the general public, at least those who read Town and Country, see the mihrab in Honolulu, but the photograph is published in reverse (fig. 210; note the faux tiles on the lower left). A burgundy carpet (?) is in front of the mihrab, and panels of mosaic are visible in the door jamb. The same elements are present in the black and white photograph (see fig. 207) likely taken around the same time.

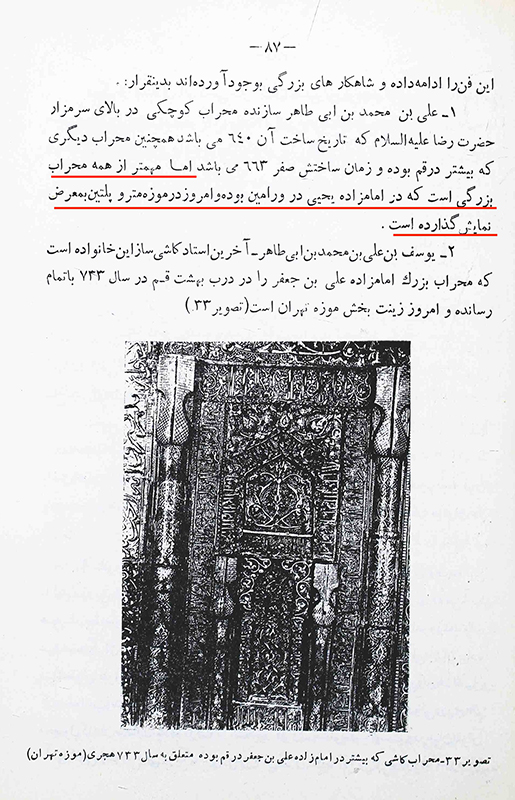

1948–49: Tehran

While a photograph of the mihrab on view in Doris Duke’s Honolulu home becomes available to certain audiences in the United States, the perception of the mihrab in Iran is entirely different. In his book on Persian ceramics published in 1327 Sh/1948–49, Mehdi Bahrami—director of the department of Islamic art at the Iran Bastan Museum (now the National Museum of Iran) and participant in the 1935 Third Congress in Leningrad—notes that the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab is currently on display in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (fig. 211).221 As we shall see, it will take decades for Iranian audiences to learn of its transfer to Hawai‘i.

1953: Tehran

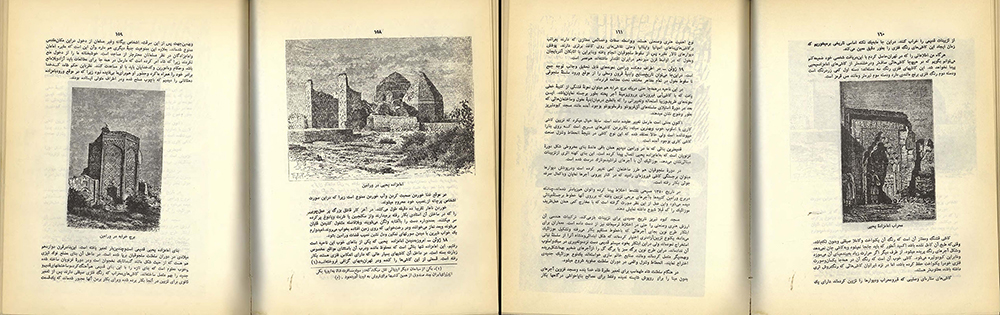

Jane Dieulafoy’s La Perse is translated into Persian by Iranian translator Ali Mohammad Farahvashi (d. 1968). The Persian translation reproduces the original woodcuts of the French version, but a major mistake is made in one of the captions. The image of the mihrab from the Emamzadeh Shah Hosayn (map), captioned generally by Dieulafoy as “Mihrab a Véramine” (p. 149), is mistakenly translated as the “mehrab-e Emamzadeh-ye Yahya” (Mihrab of the Emamzadeh Yahya) (fig. 212).222 The book’s visual and textual content becomes a key reference for Iranian audiences for decades.

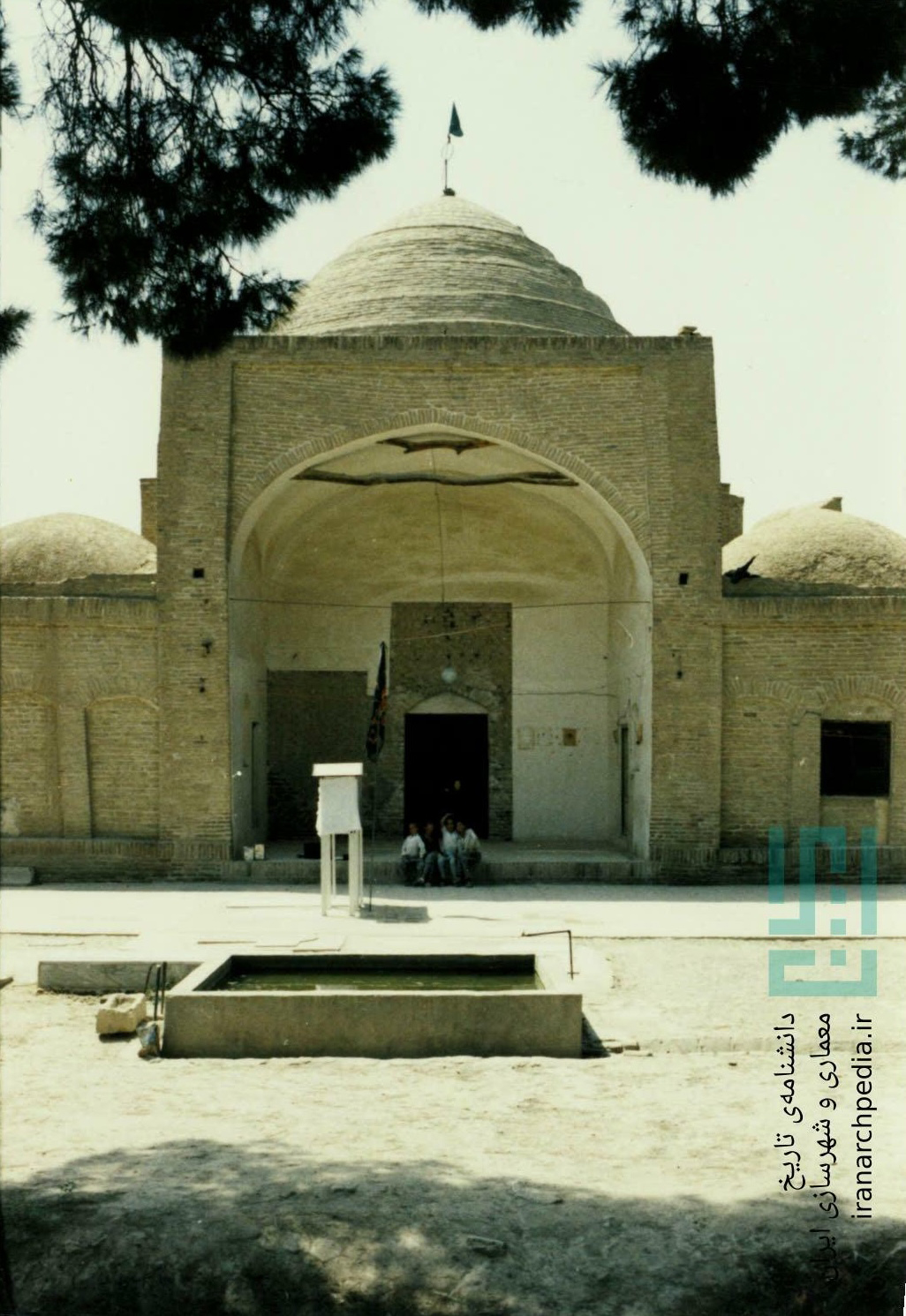

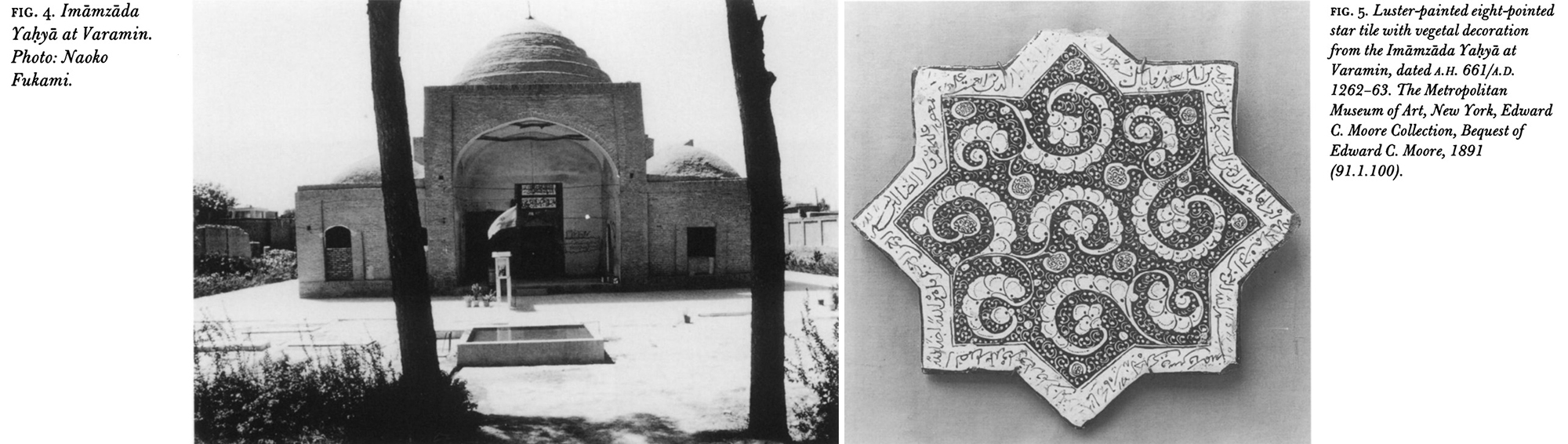

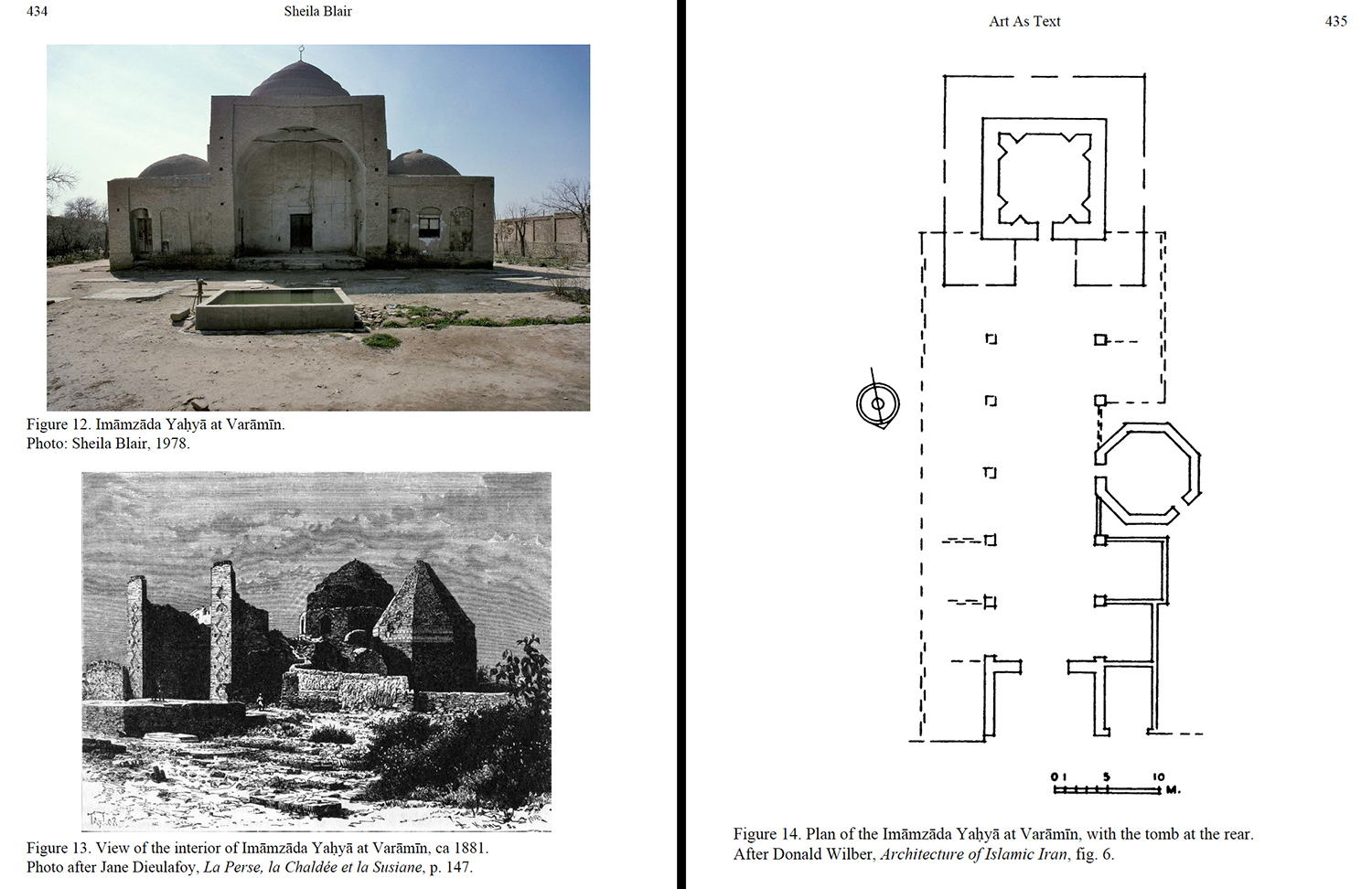

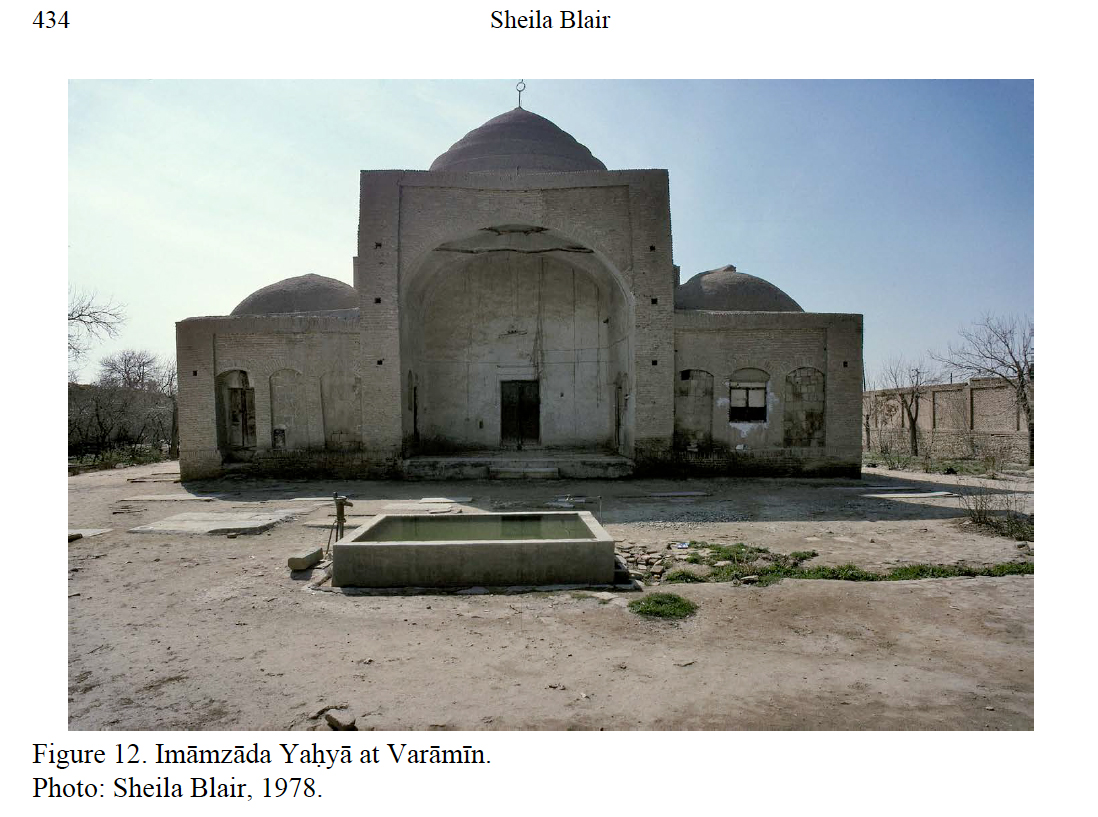

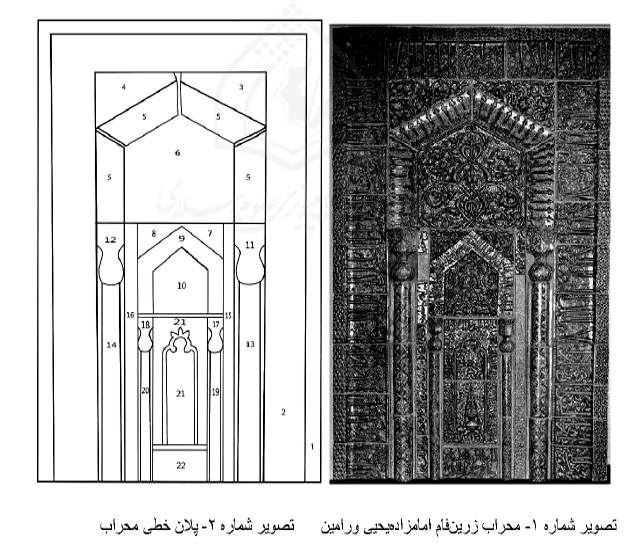

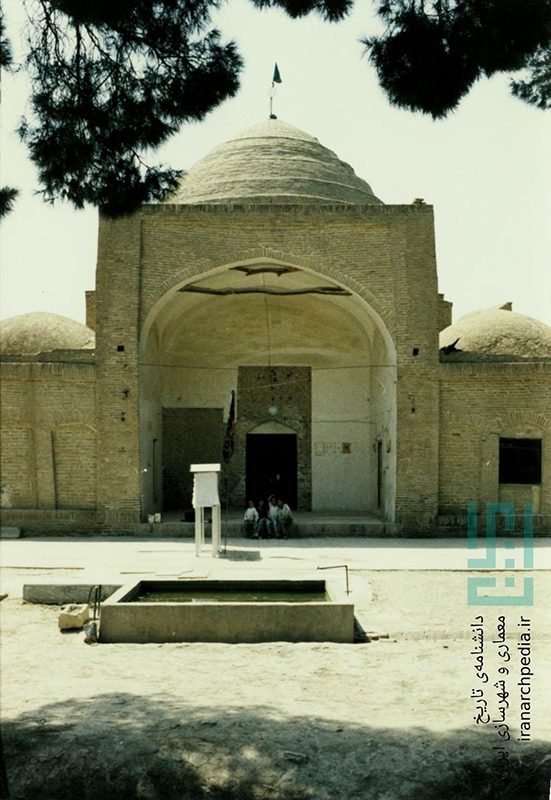

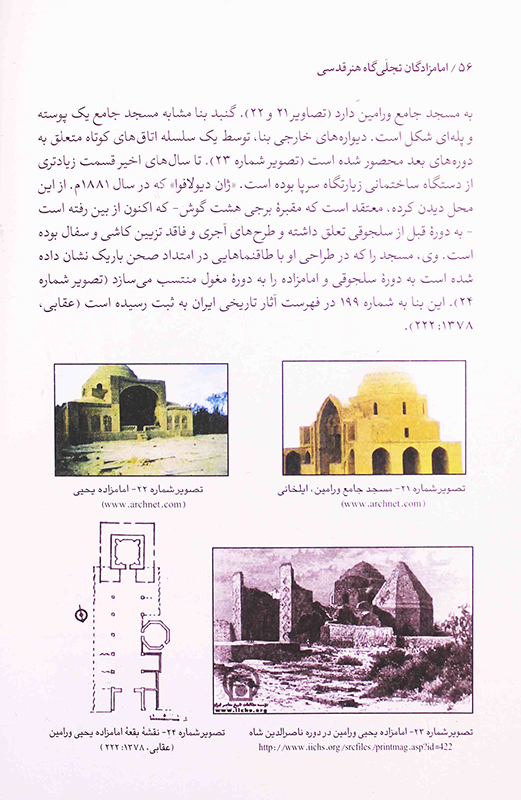

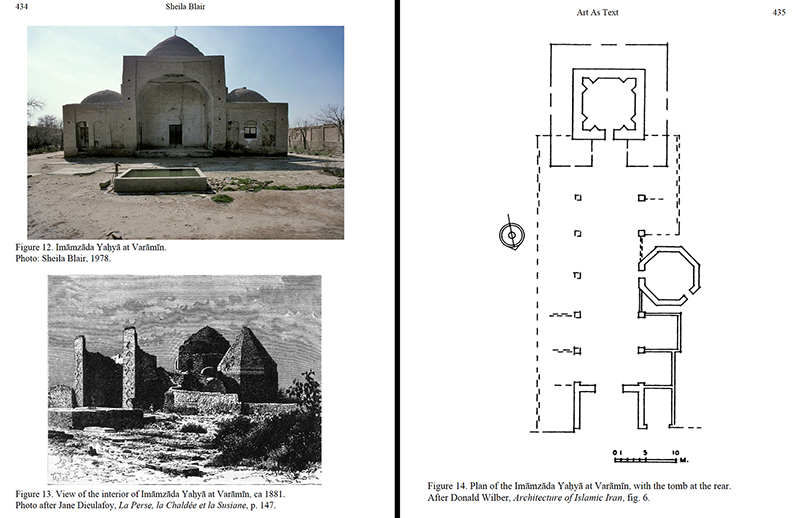

1955: Princeton, New Jersey

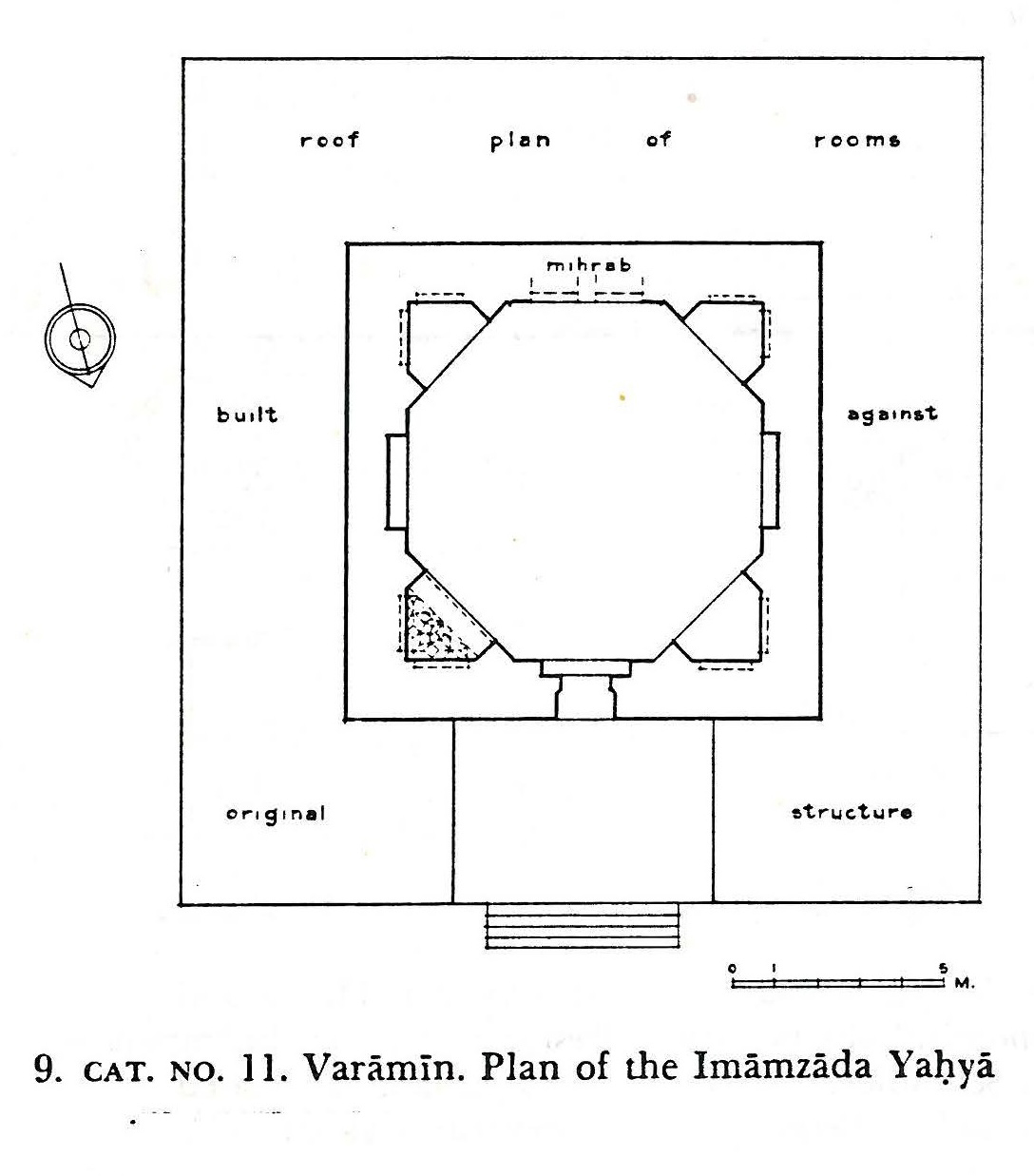

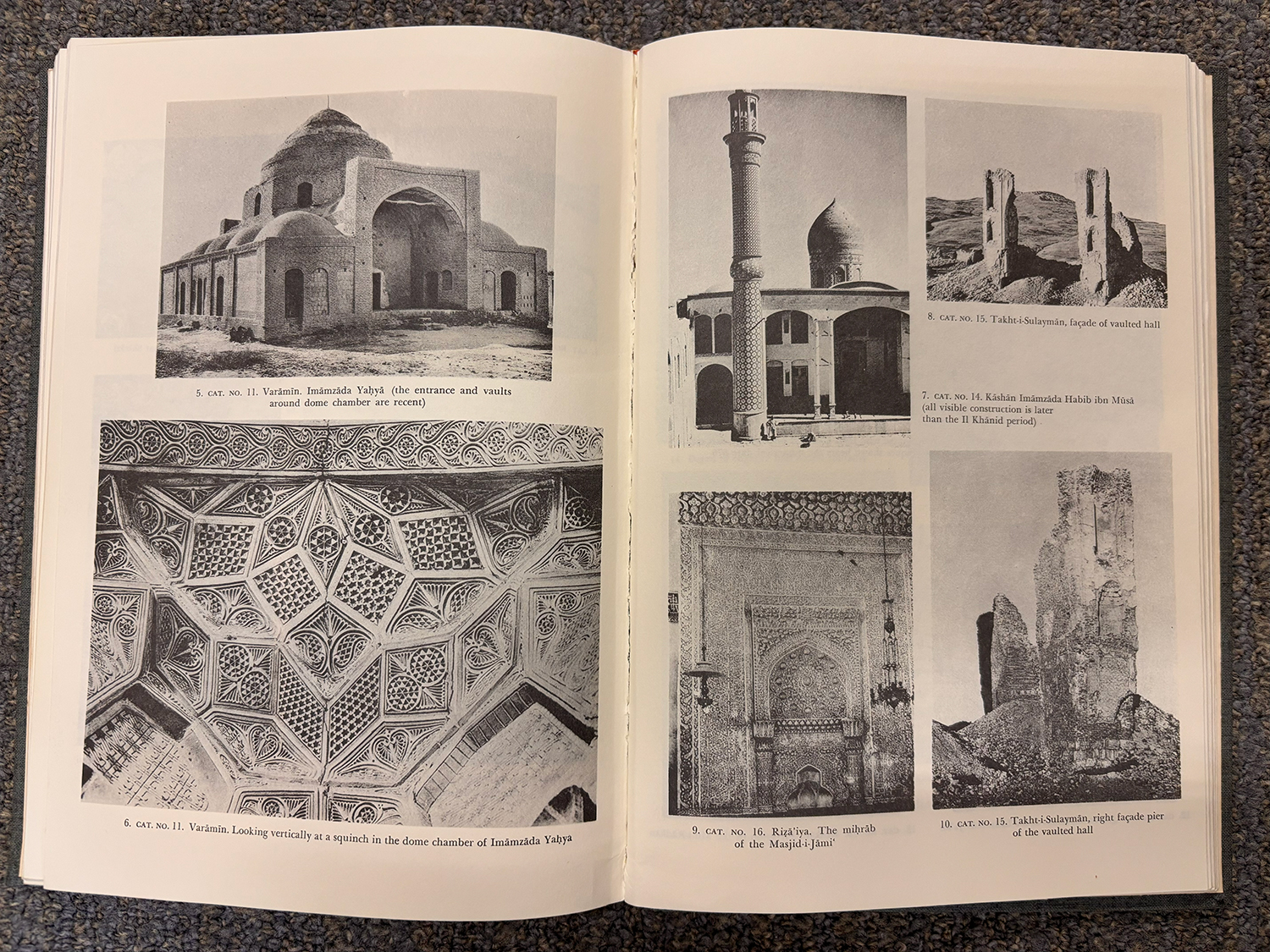

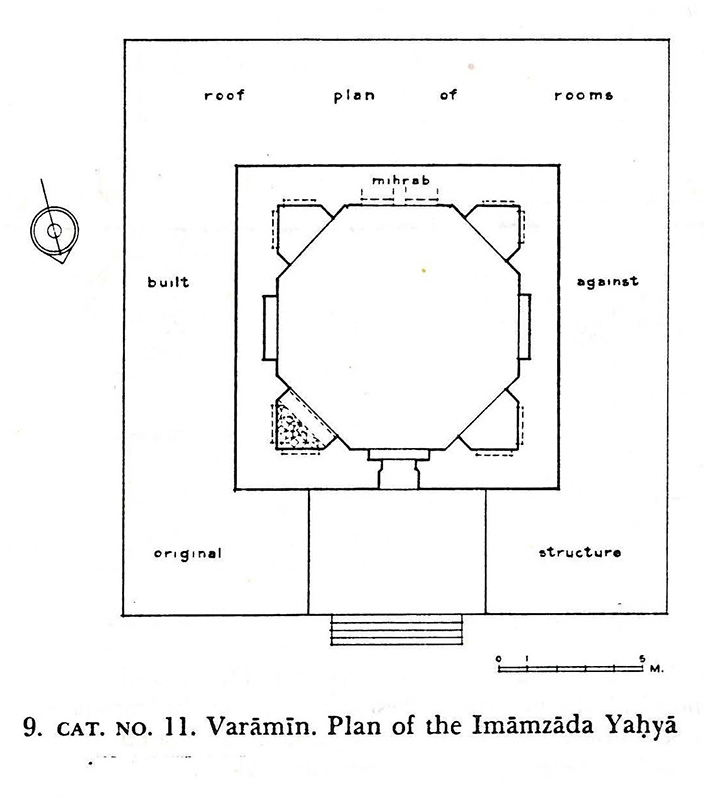

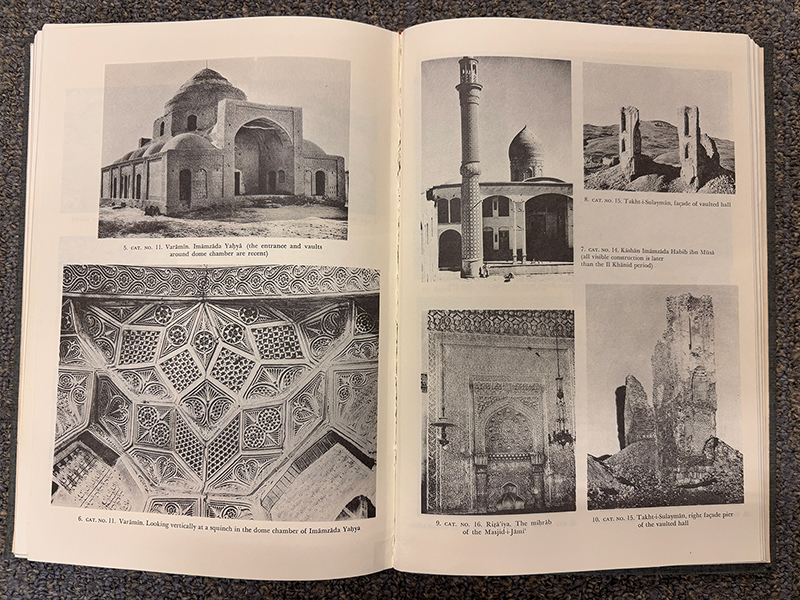

Based on his visit to Varamin in May 1939, Wilber devotes an entry to the Emamzadeh Yahya in his book on Iranian Ilkhanid architecture. This short text can be considered the first academic assessment of the site in English scholarship and includes a plan of the tomb (fig. 213), a proposed plan of the complex, and two photographs (fig. 214).223 Wilber likely took many more photographs, including a distant view of the site from a field to the northeast (see fig. 154).

Wilber bases much of his discussion of the tomb and its mihrab on earlier publications, including Jane Dieulafoy (1887) and Friedrich Sarre (1910). He is the first western scholar to discuss the mihrab’s original architectural setting and the literal void left behind. He marks the mihrab’s location on his plan of the tomb (see fig. 213), describes this area as “filled with a late blocking of brick,” and analyzes the mihrab’s width in relation to the void, noting that the mihrab is slightly narrower. He also offers some background on its removal: “The present owner of the mihrab has stated that it was taken to Paris by the wealthy owner of the village and sold there.” The “present owner” in question is somewhat unclear. If it was the owner as of 1939 (Wilber’s original fieldwork), it would be Kevorkian. If it was the owner as of 1955 (the book’s publication), it would be Duke. Either way, Wilber withholds this important information.

Wilber contextualizes the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab in reference to several large luster ensembles in museums. He compares the mihrab’s central niche with a lamp to the “tombstone mihrāb” from Qom “now in the Berlin Museum” (see fig. 159) and the same museum’s “very similar luster faïence mihrab from the Masjid-i-Maydān at Kāshān” (see fig. 73). He suggests that the two central panels of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab, as well as the lowermost panel with the date, were possibly later additions, bringing “the dating of the mihrab as a whole into question,” while conceding that the tiles “fit the space very well” (see comparable questioning of the date panel in 1931). He also mentions that several tiles belonging to the mihrab’s outer border are now in the Hermitage Museum and at least one other collection.224

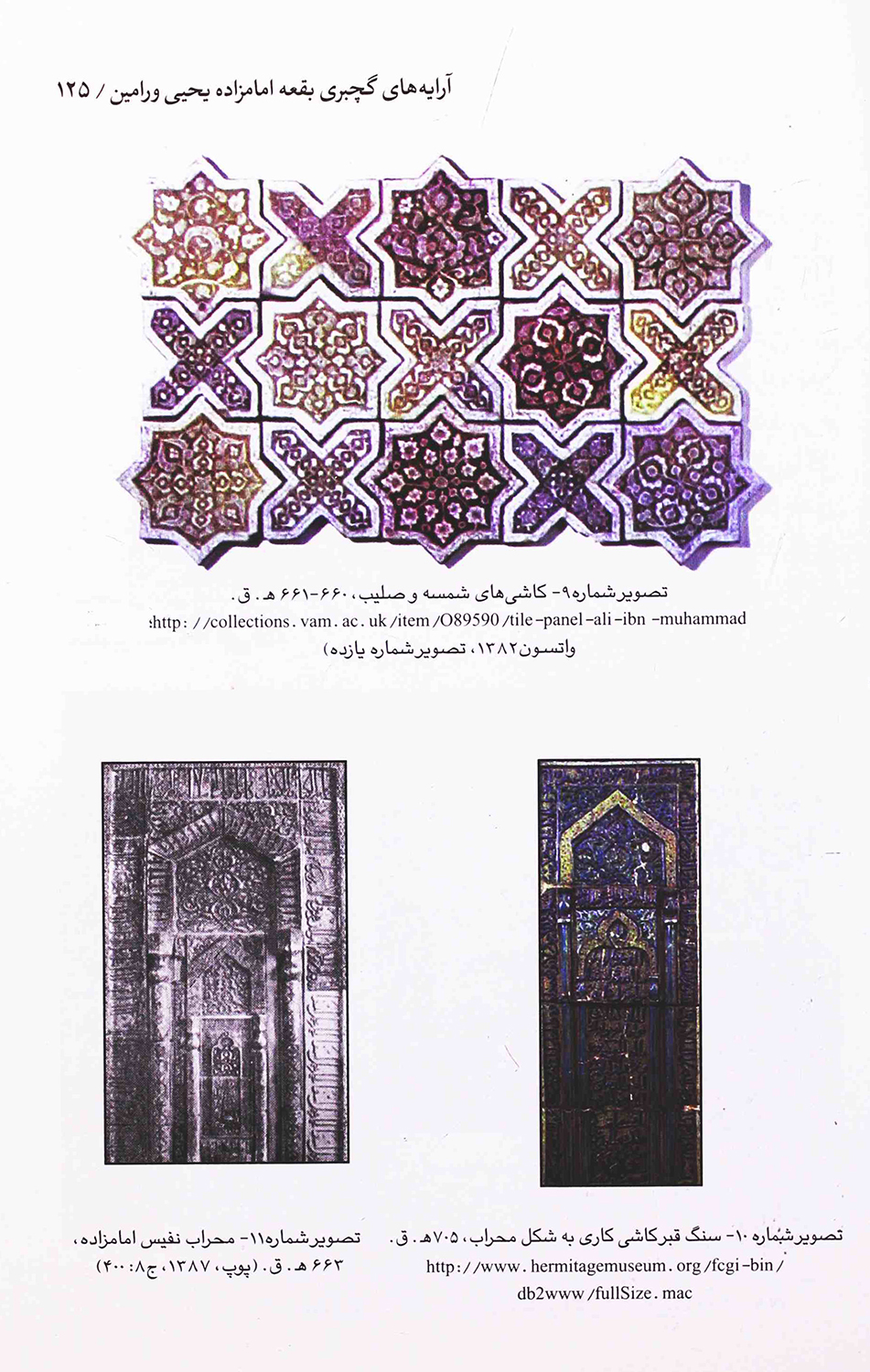

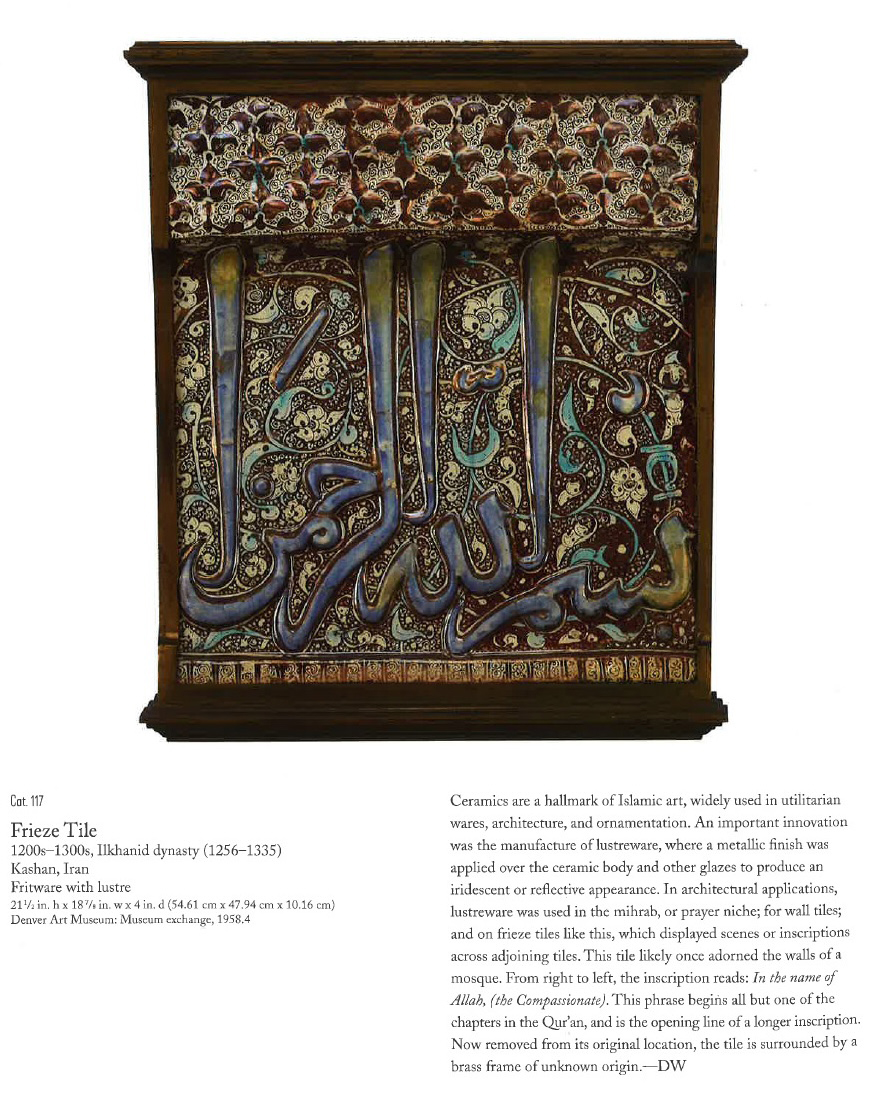

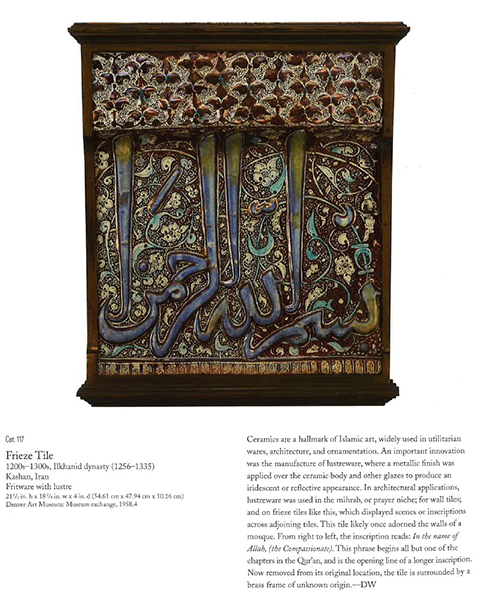

1958–61: Denver, Colorado

In June 1958, the first tile missing from the mihrab’s outer border enters the Denver Art Museum (DAM) set in a brass frame decorated with a dragon design (figs. 215–216). The tile is a loan from the New York gallery French & Company, and the museum’s annual report describes it is as “Section of a Façade Tile from a Mosque at Sultanabad, XV century.”225 In May 1961, the museum and French & Company conduct a formal exchange—the tile for a tapestry—and the tile is officially accessioned into the museum as 1958.4 (fig. 217).

It is not known when this tile was removed from the mihrab, but it was definitely gone by the time that it was photographed in circa 1900 Paris (see fig. 62). It could have removed in Paris and sold to a collector or museum, or it might have been removed while the mihrab was still in situ. As the first tile in the lower right, it would have been a vulnerable initial target.226

1965: Honolulu

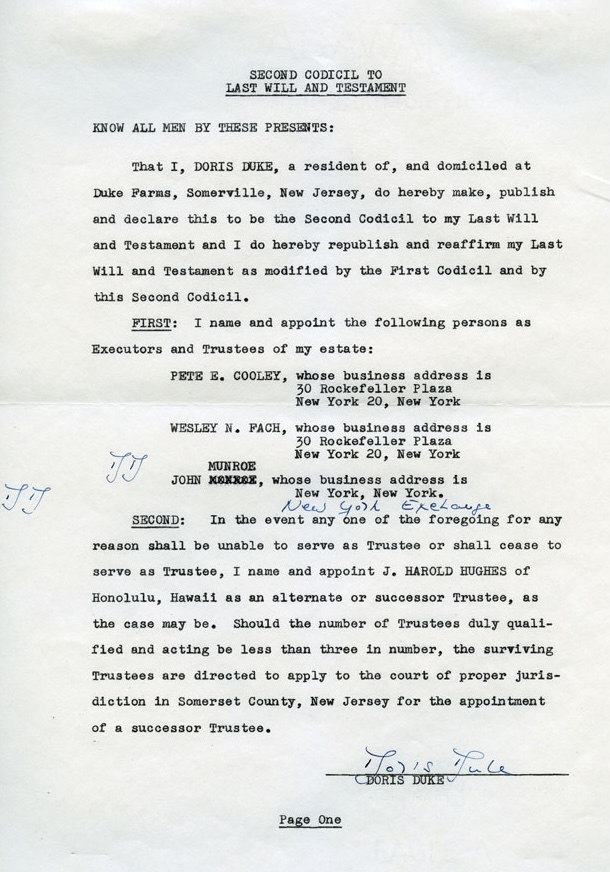

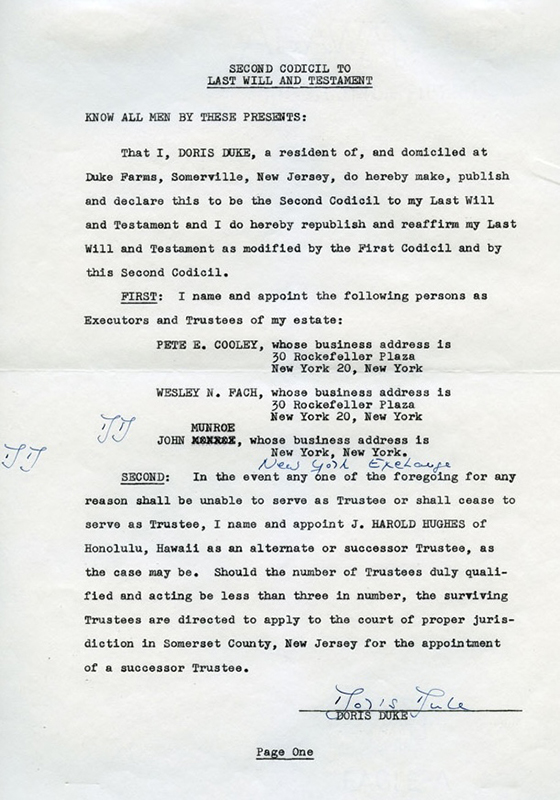

Doris Duke recognizes the value of Shangri La and its collection and adds a second codicil to her will creating the Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art “to promote the study and understanding of Middle Eastern Art and Culture” (fig. 218). In doing so, she creates one of the few foundations dedicated to the art and culture of the Islamic world in the United States. It seems that she bore this greater mission in mind during the last three decades of her collecting (1965–93).

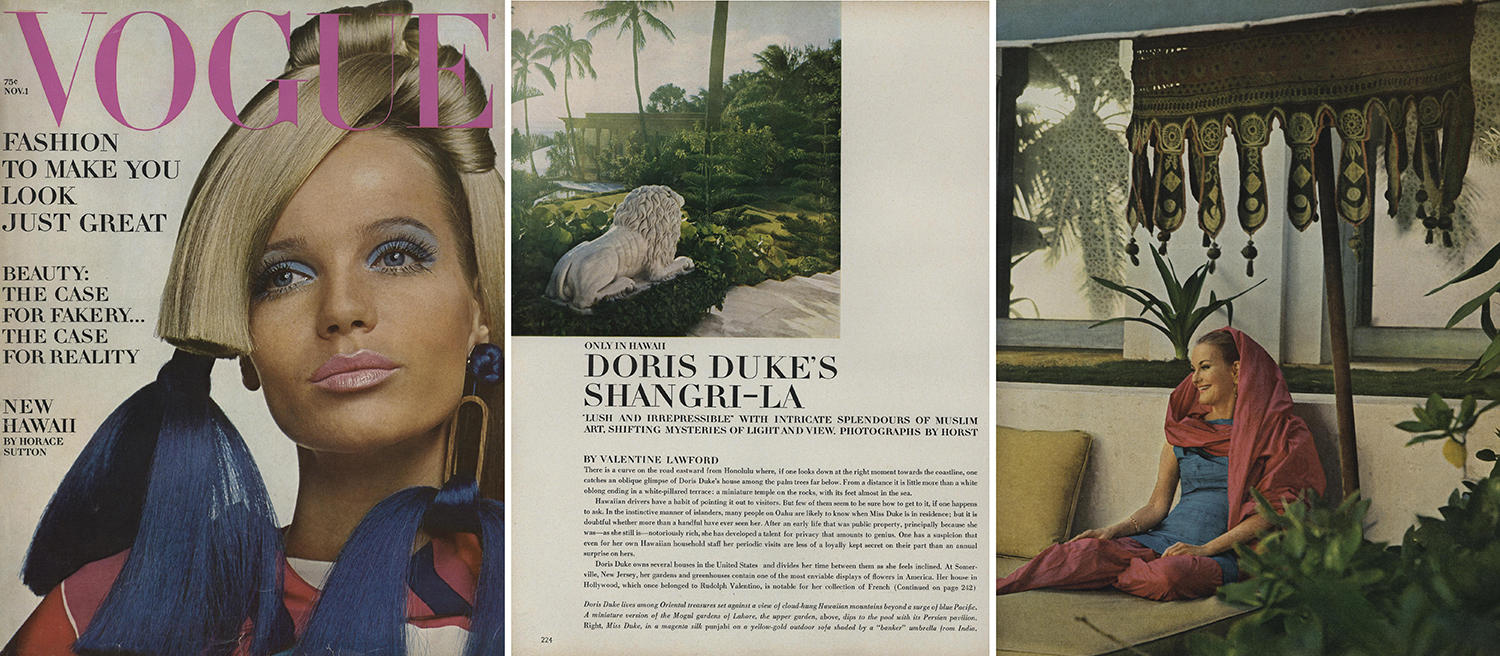

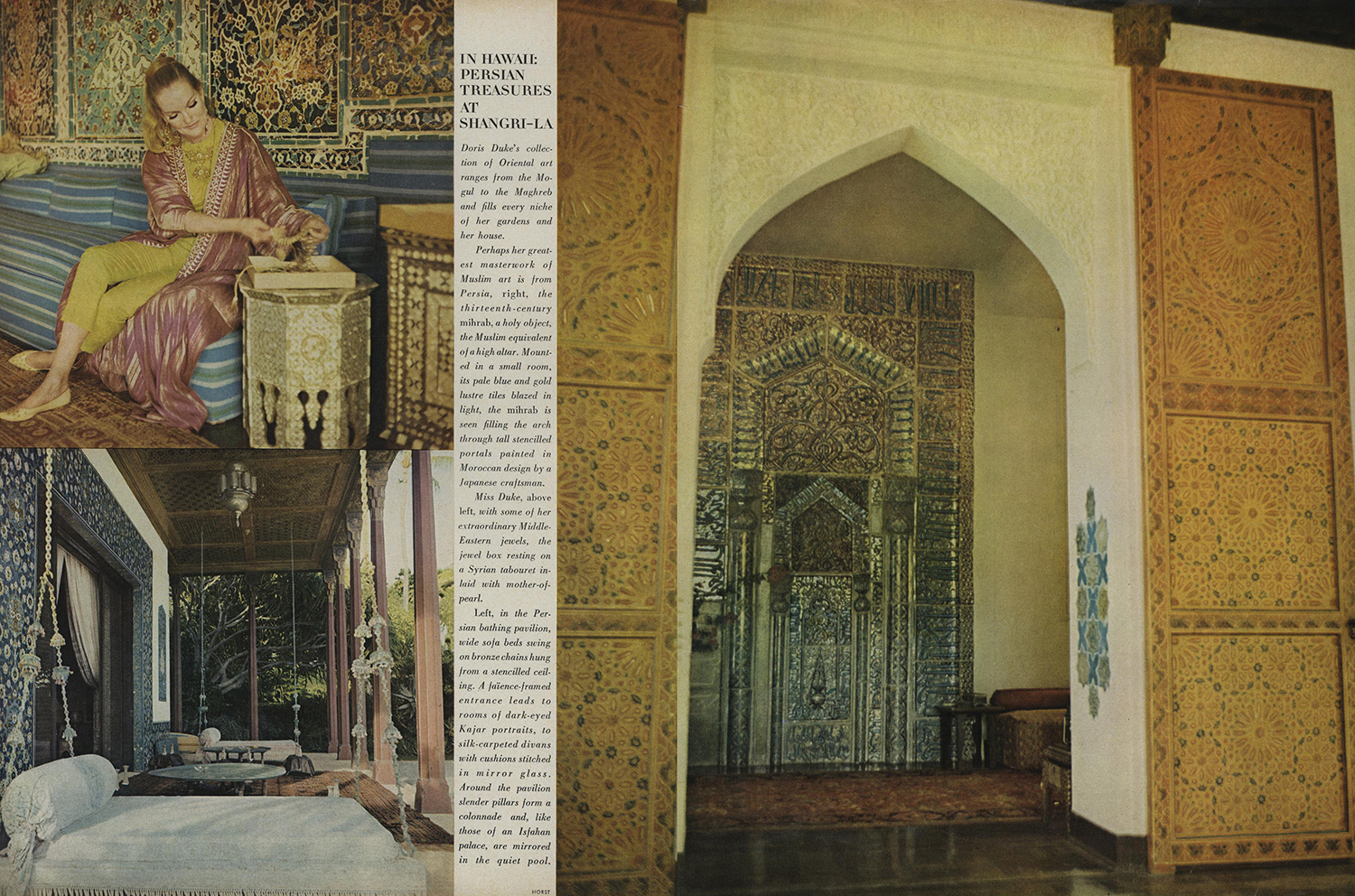

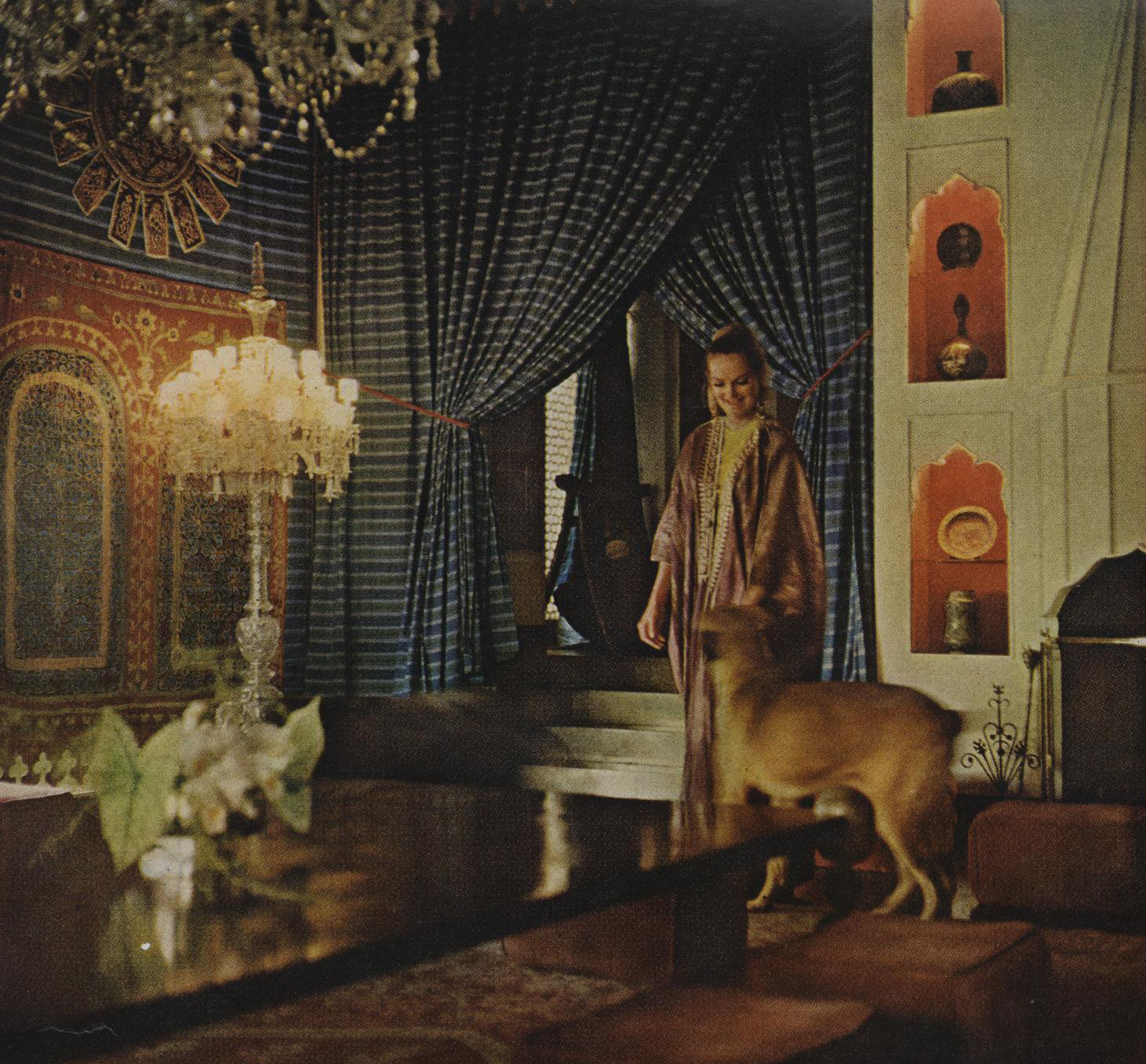

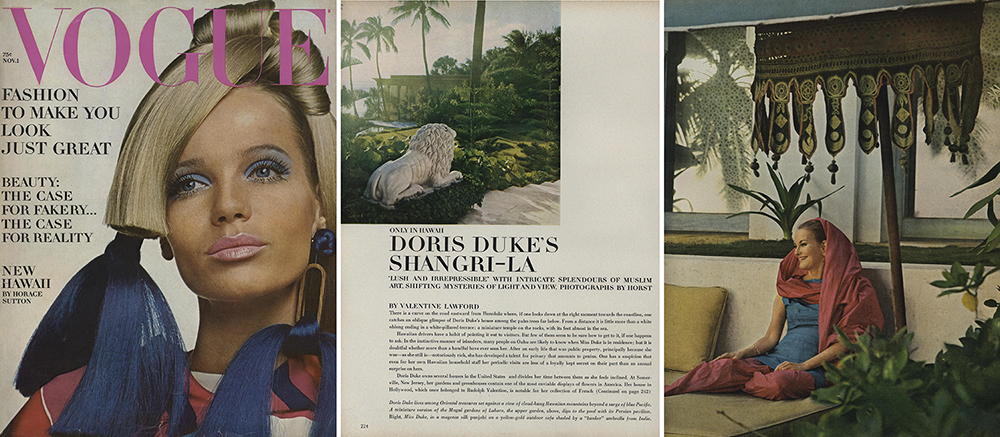

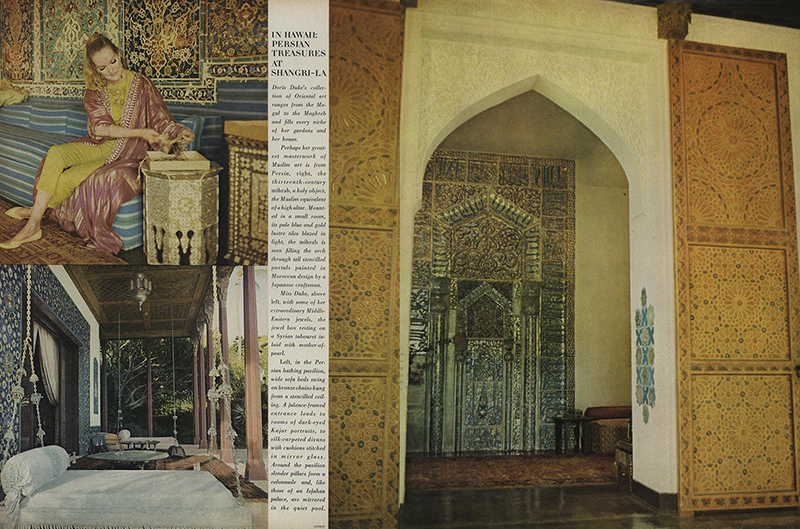

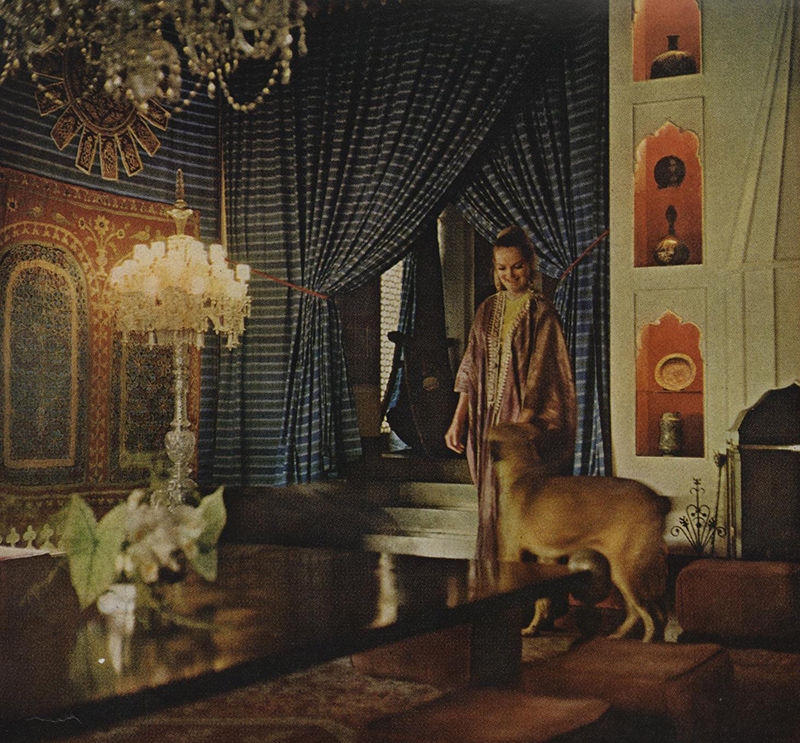

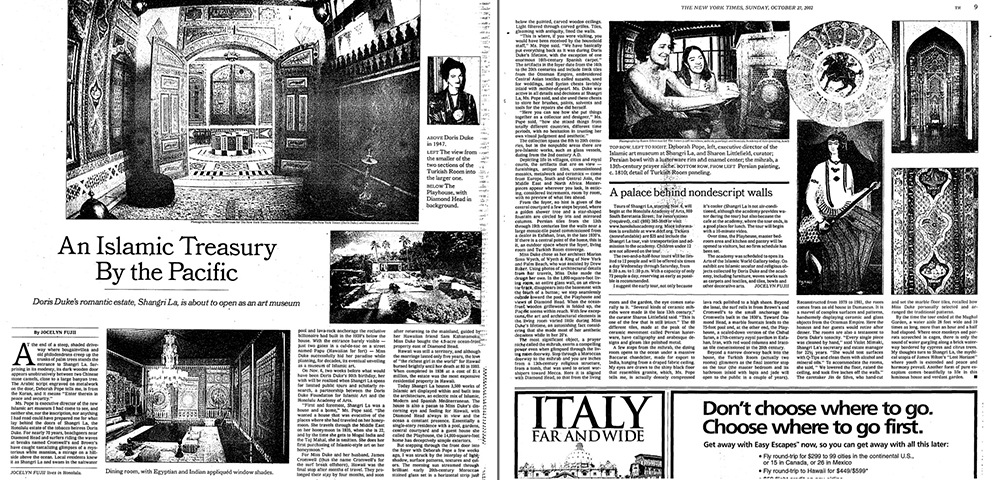

1966: Honolulu

The mihrab appears in Vogue, the monthly fashion and lifestyle magazine. Author Valentine Lawford makes many references to Doris Duke’s lavish lifestyle and belongings and highlights her passion for collecting. On the mihrab, Valentine writes, “Perhaps her greatest masterwork of Muslim art is from Persia, right [directional cue to the reader to look right], the thirteenth-century mihrab, a holy object, the Muslim equivalent of a high altar” (fig. 219).227 The adjacent photograph shows the mihrab through the living room arch, and the ensemble is again reproduced in reverse, as in 1947 (fig. 220).

The article includes four photographs of Duke in what could be described as ‘exotic’ or ‘ethnically inspired’ clothing reflecting her interest in the cultures she encountered and collected from. One outfit, for example, is described as a “magenta silk punjabi” over a “gold-and-mauve Damascus caftan.” In one image, she stands in the dining room with her dog, not too far away from the Mihrab Room (fig. 221; see the plan in fig. 142). In the mihrab’s original setting, the casual presence of dogs would have been inconceivable, and this juxtaposition underscores its profound transformation from an architectural feature embedded in a spiritual tomb to an aesthetic backdrop in a private home.

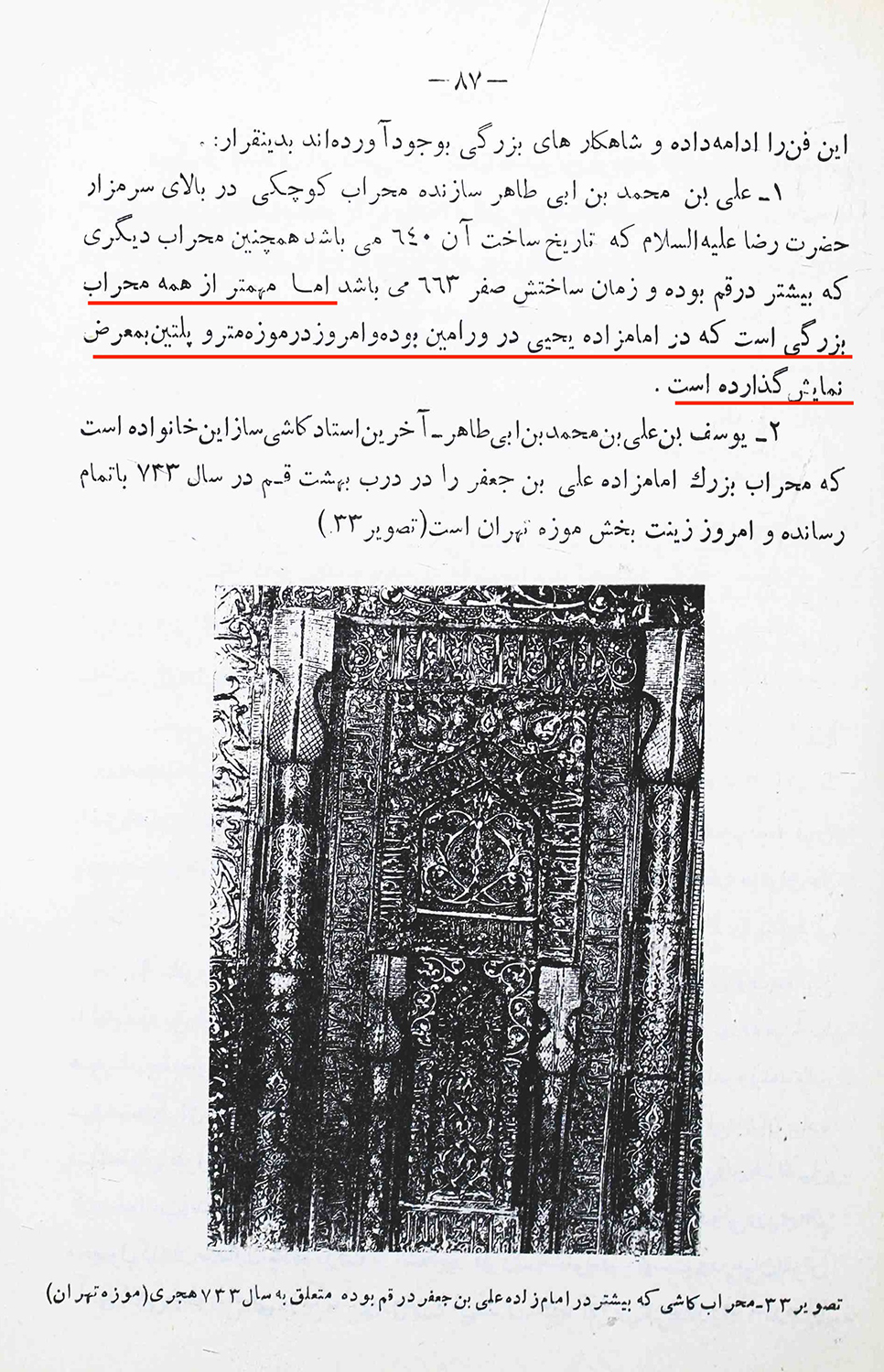

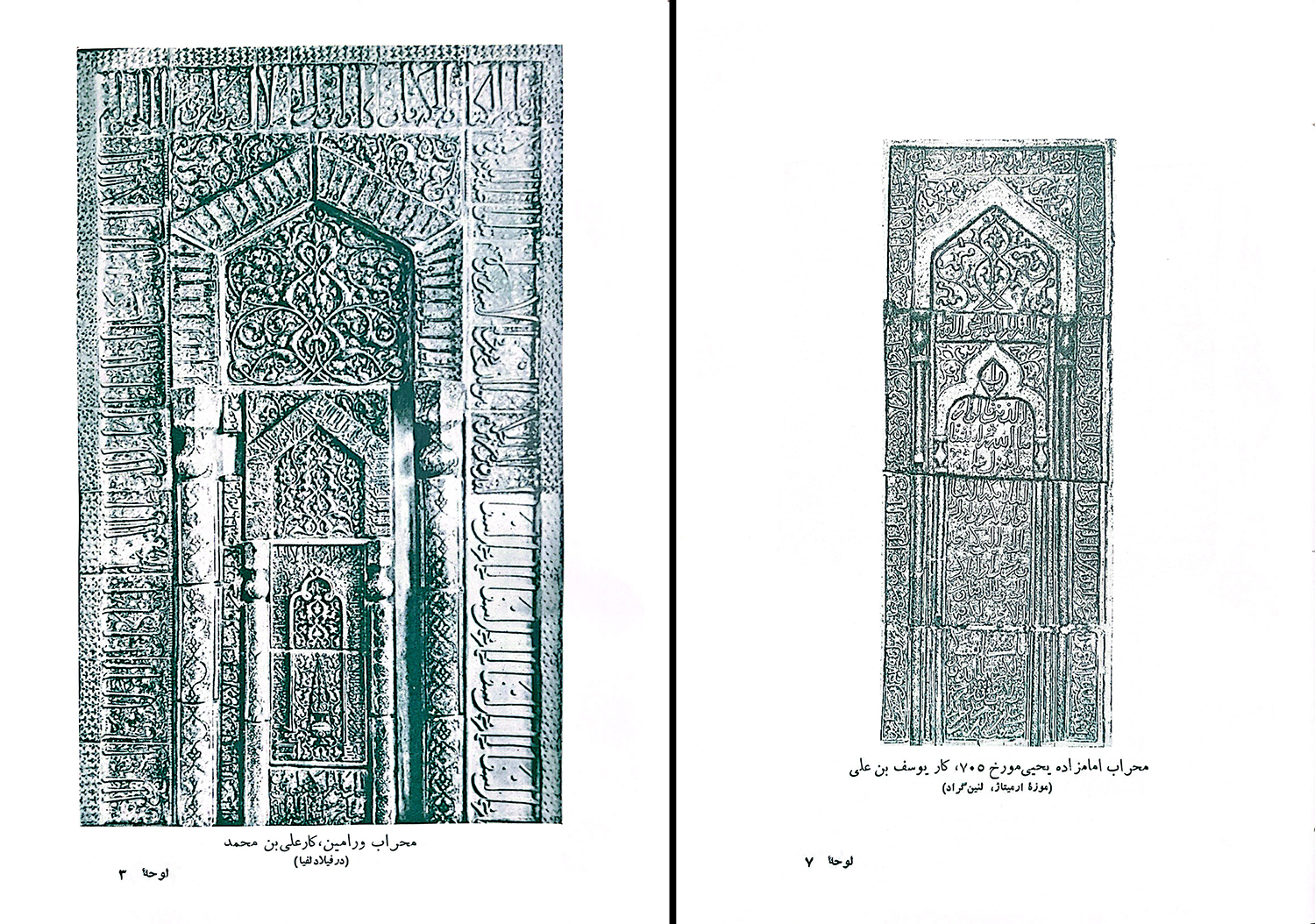

1966: Tehran

While some American audiences see the mihrab in Vogue, it is published for the first time in Persian in the printed edition of ʿArāyes al-jawāher va nafāyes al ʾaṭāyeb (Precious Minerals and Exquisite Fragrances), edited by Iranian bibliographer and historian Iraj Afshar (d. 2011) (fig. 222). This manuscript on mineralogy and pottery was written in 1300 by Abolqasem ʿAbdollah Kashani, the son of the potter responsible for the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab and the brother of the artisan involved in making the tombstone attributed to Yahya b. ʿAli’s cenotaph.

Afshar’s edition reproduces both the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab and the tombstone panel attributed to Yahya b. ʿAli’s cenotaph, marking the first time that they are conceptually reunited in Persian. Both images derive from Friedrich Sarre’s 1935 article (see fig. 132) and had also been published in a volume related to ʿArāyes al-Jawāher, which was perhaps Afshar’s point of exposure. Afshar’s captions seem to rely on Sarre’s original German ones, and hence repeat some of their inaccuracies, or at least misleading information. The Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab is again described as the محراب ورامین (Varamin mihrab) and its location is listed as Philadelphia, although it had now been in Hawai‘i for twenty-six years. Meanwhile, the tombstone cover attributed to Yahya b. ʿAli’s cenotaph and preserved in the Hermitage is labeled as محراب امامزاده یحیی (mihrab of Emamzadeh Yahya).

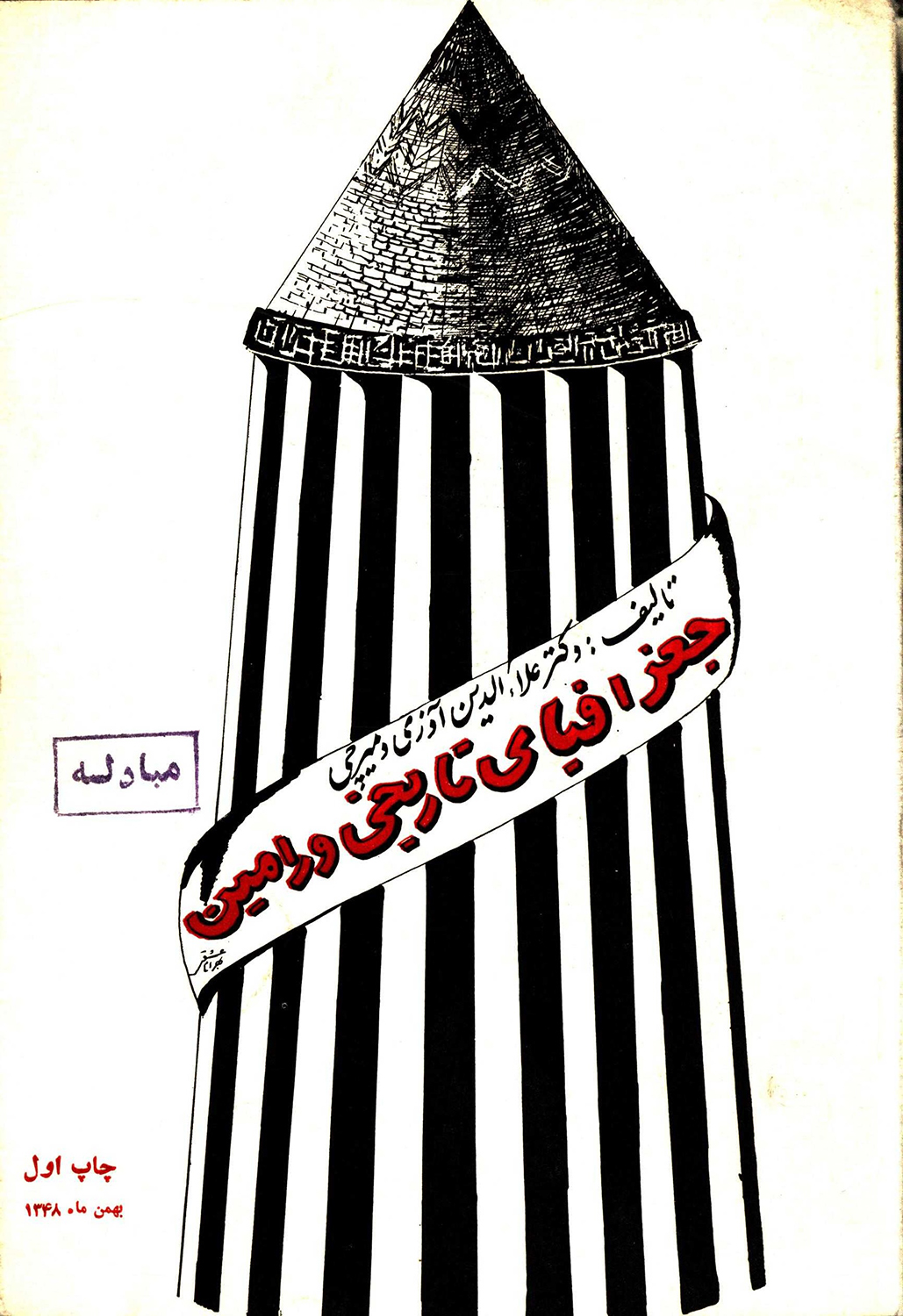

1970: Tehran

Historian Alaoddin Azari Damirchi publishes the first monograph dedicated to the history of Varamin and its monuments. In his introduction, he acknowledges that numerous books have been written on Iran and Iranians, but he laments the lack of scholarly studies on the cultural, social, and architectural history of many regions within the country, resulting in their continued obscurity. He also criticizes the prevailing tendency among Iranian scholars to rely on foreign authors and merely cite their work, rather than producing original research. Damirchi frames his book as a contribution that aims to address this gap and encourage future serious research on the region.228

The Emamzadeh Yahya is visually represented by a distant photograph of the complex (see Photo Timeline, no. 22), but no images of the tomb’s interior or its displaced tiles are included. Damirchi provides brief information about the shrine’s history, patron, decoration, and the theft of its tiles. Of particular note is his inclusion of excerpts from Jane Dieulafoy’s comments on the tomb’s luster tiles (in Persian translation as of 1953), revealing the extent to which her account was shaping Persian-speaking audiences’ understanding of the shrine and its displaced tiles.229

1970s–90s: Honolulu

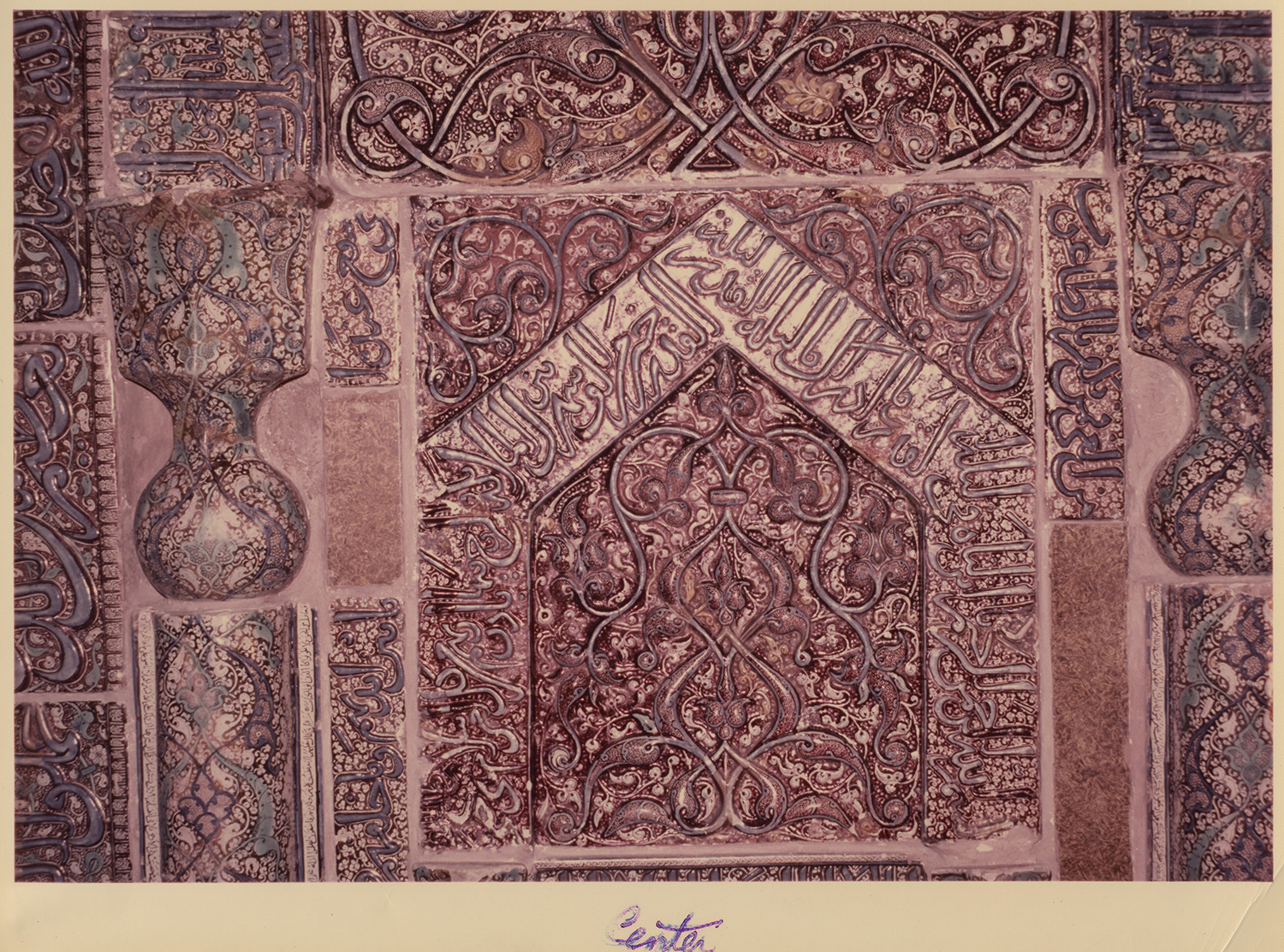

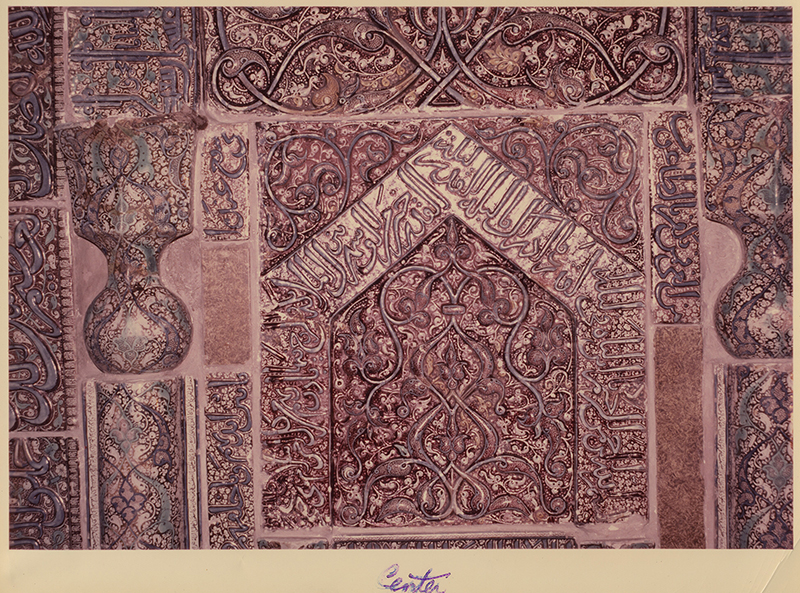

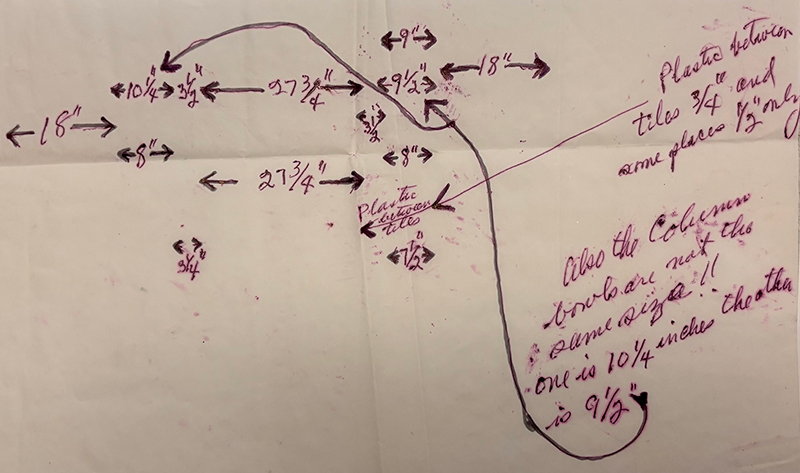

In September 1976, color photographs are taken of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab at Shangri La (fig. 224). Their exact purpose is unclear. They could just be photo-documentation, or they could have a larger role, perhaps related to the mihrab’s condition. Kodak prints dated September 1976 are inscribed in purple ink in handwriting that corresponds to a sketch attributed to Johnny Gomez (d. 1999), one of Duke’s oldest friends from the 1930s and a paid member of the staff who at times lived on the property (figs. 225–227). Among other details, Gomez’s sketch indicates the panels of “fake wood” standing in for the missing tiles, the presence of plastic between some tiles, the fact that the “column bowls” (capitals of the columns) are not the same size, and the widths of individual tiles.

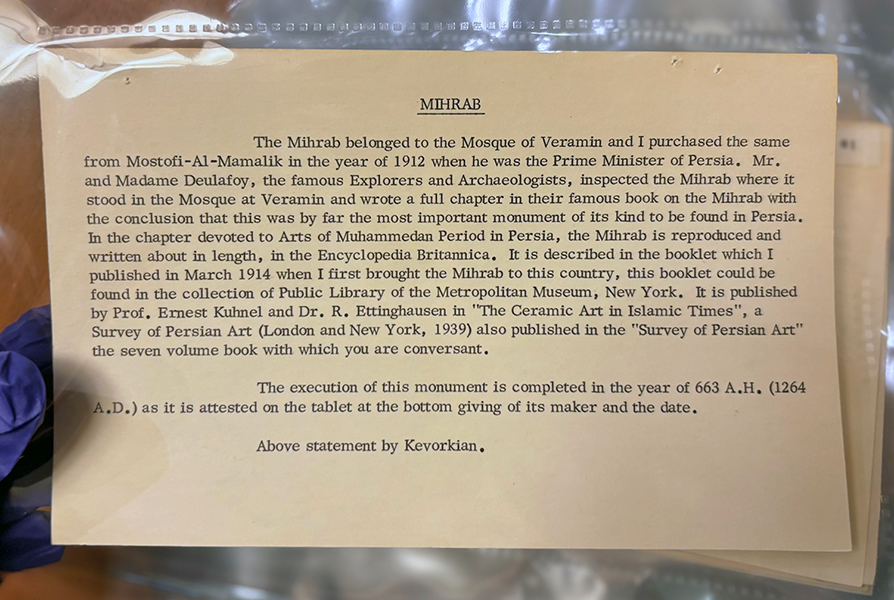

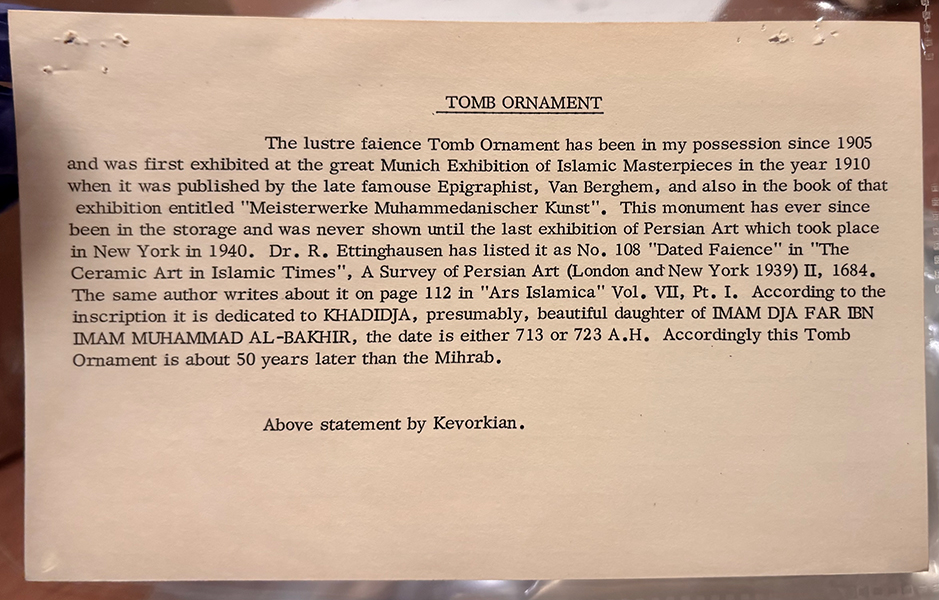

During these later decades at Shangri La, the mihrab is part of a systemized inventory of Duke’s art collection. It is given a card with a color photograph, description, purchase year, vendor, price, location, and an extended description (figs. 228–229). The last is credited as a “statement by Kevorkian” and repeats his account of the mihrab belonging to the “Mosque of Veramin” and being purchased from Mostowfi al-Mamalek in 1912 when he was Prime Minister (actually, Minister of War). This statement was likely drawn from one of Kevorkian’s letters during the 1940 negotiations, as it attempts to bolster the value and prestige of the mihrab by referencing earlier publications and exhibitions, often embellishing their content in the process. Included in Kevorkian’s references are Dieulafoy’s 1887 travelogue, an article in Encylopaedia Britannica, his own 1914 exhibition catalog, 1930s articles by Ernst Kühnel and Richard Ettinghausen, and the 1938–39 A Survey of Persian Art.230

The mihrab’s inventory card is filed with others related to the Mihrab Room, including the ten luster tiles signed by Yusof b. ʿAli (fig. 230) and the tombstone cover belonging to the cenotaph of Emamzadeh Khadijeh Khatun (fig. 231). In the photograph appended to the former, tall candlesticks are placed on either side of the tombstone panel, recalling the atmosphere around the Guanyin in 1939 and the mihrab in New York in 1940. Kevorkian’s statement on the “tomb ornament” states that it had been in his possession since 1905, in storage since the 1910 Munich show, and not displayed again until the 1940 New York exhibition.231

1980–85: Varamin

In 1980, Varamini historian and writer Saeid Vaziri publishes a book on the history of Varamin, including accounts of several lesser known emamzadehs in the region. In his section on the Emamzadeh Yahya, he does not mention the mihrab or its vacant location, but he does refer to the stolen tombstone of the cenotaph and missing tiles of the dado. His mention of fallen stucco decoration and neglect of preservation (با همه بیتوجهی که در حفظ [و] حراستشان شده است) underscores the building’s deteriorated condition at the time.232

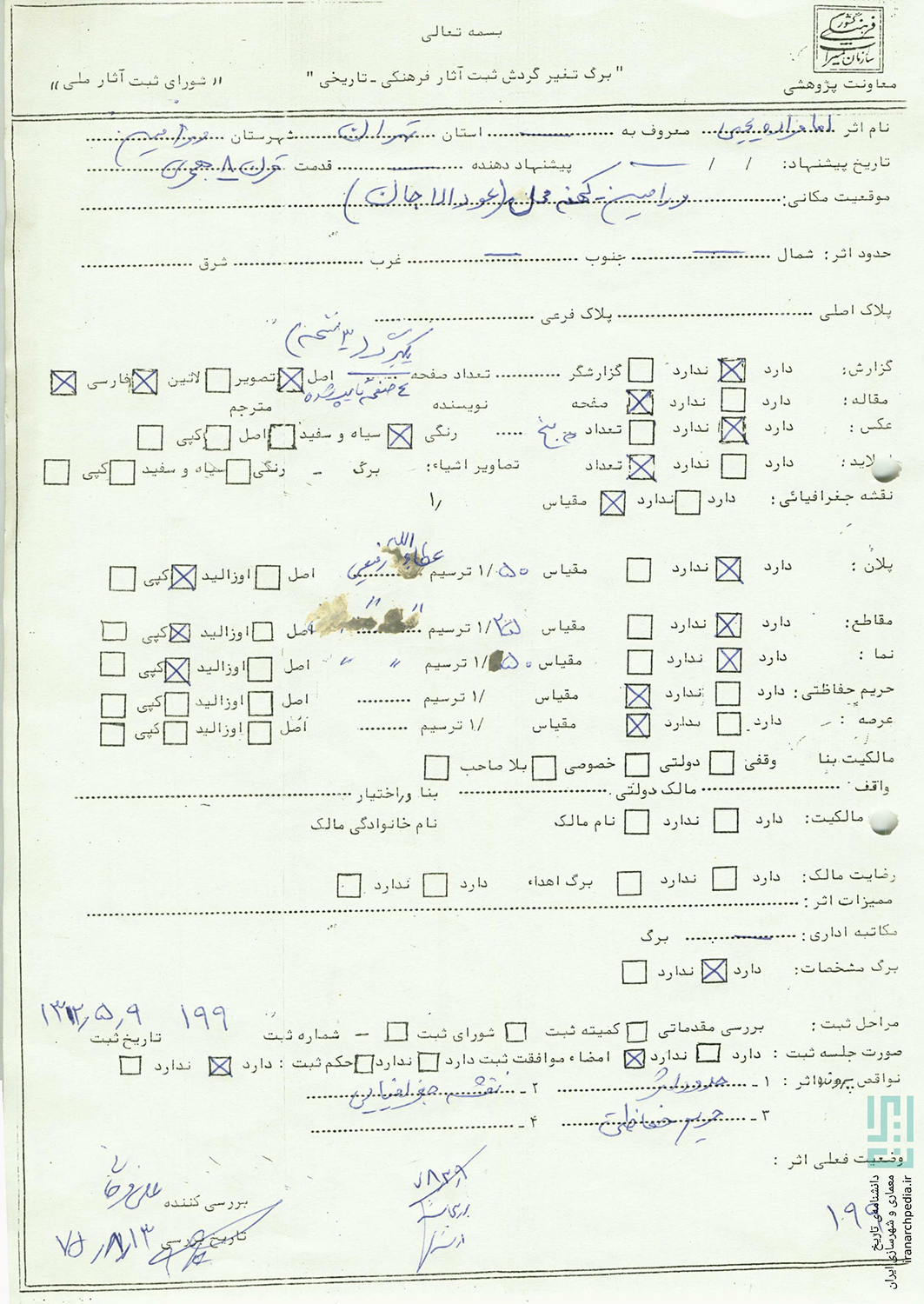

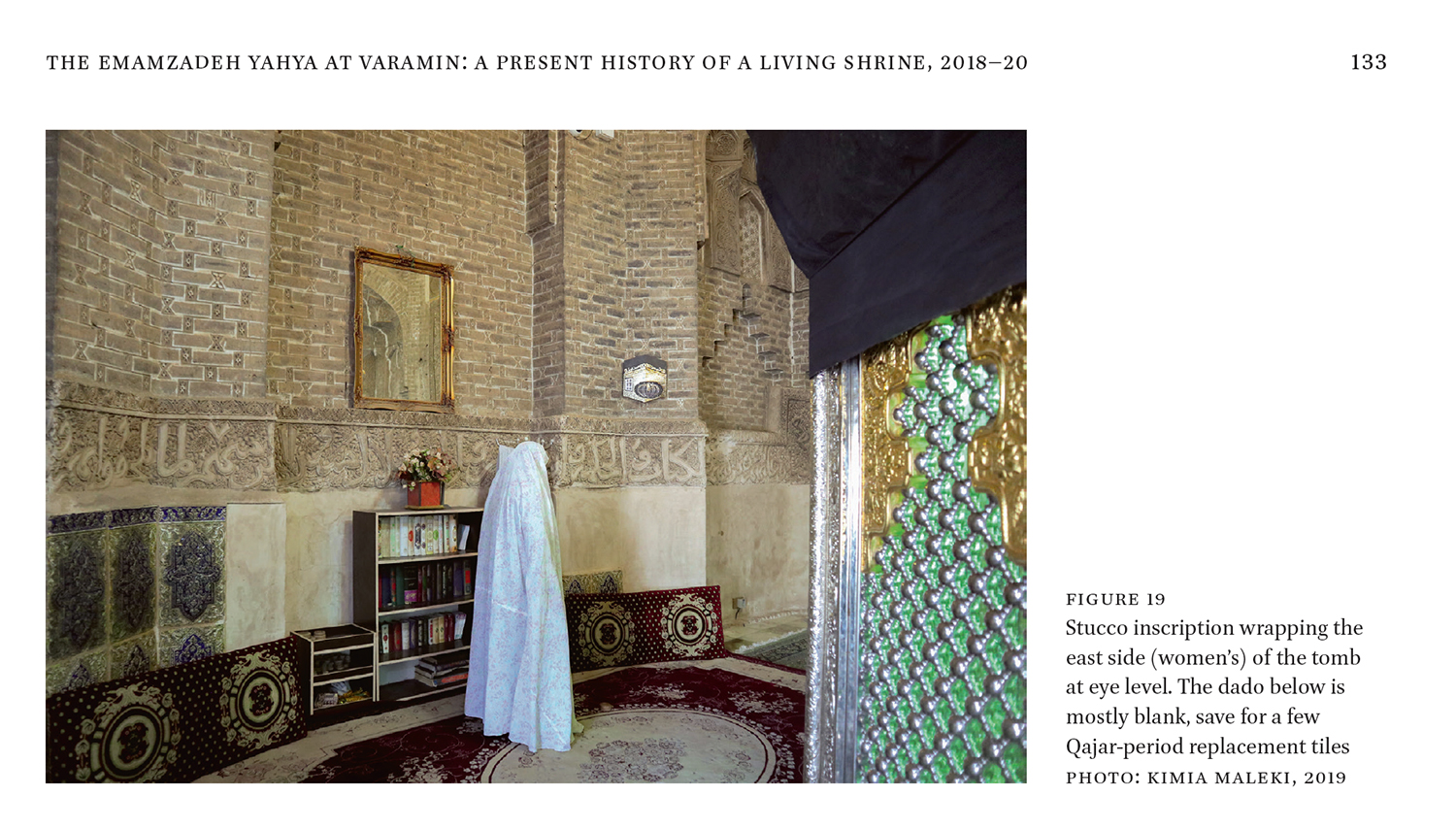

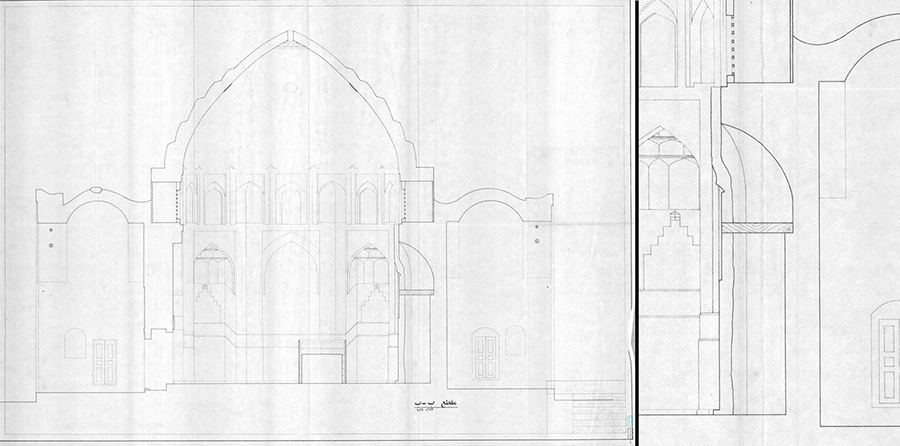

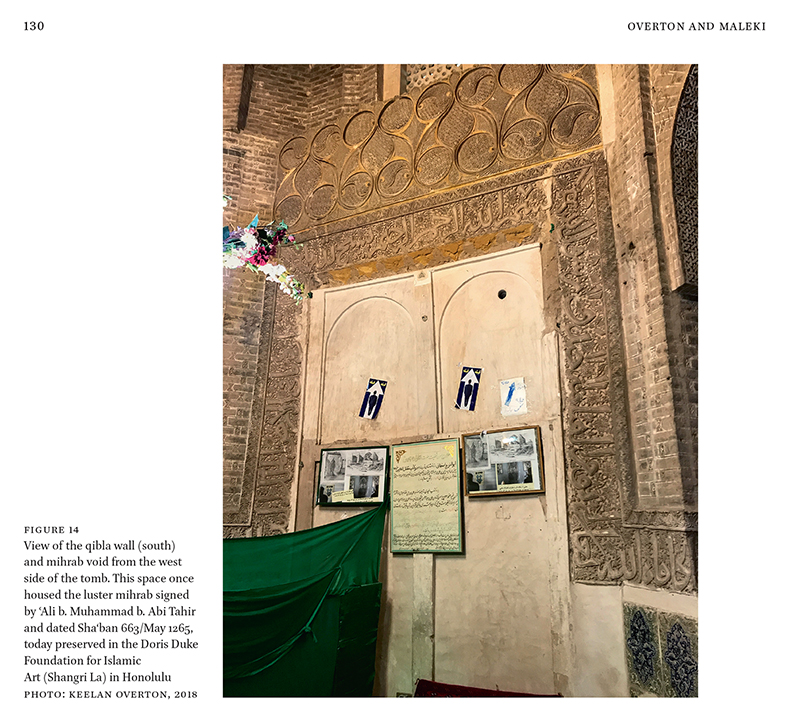

Three years after Vaziri’s remarks, the Emamzadeh Yahya is the focus of a three-year (1983–85) restoration campaign supervised by Iranian architect Mohammad Hasan Moheb-Ali under the auspices of the National Organization for the Preservation of Historic Monuments of Iran (سازمان ملی حفاظت آثار باستانی ایران) (see Preservationists). Inside the tomb, efforts concentrate on the qibla wall. The large horizontal stucco panel above the mihrab is lifted, cleaned, and consolidated, and plasterwork on the outer edge of the mihrab void is removed, revealing the imprints of half star and cross tiles (fig. 233). Around this time, a small fragment of the tip of a luster cross is remounted below these imprints as a poignant reminder of the tomb’s stolen luster tiles.

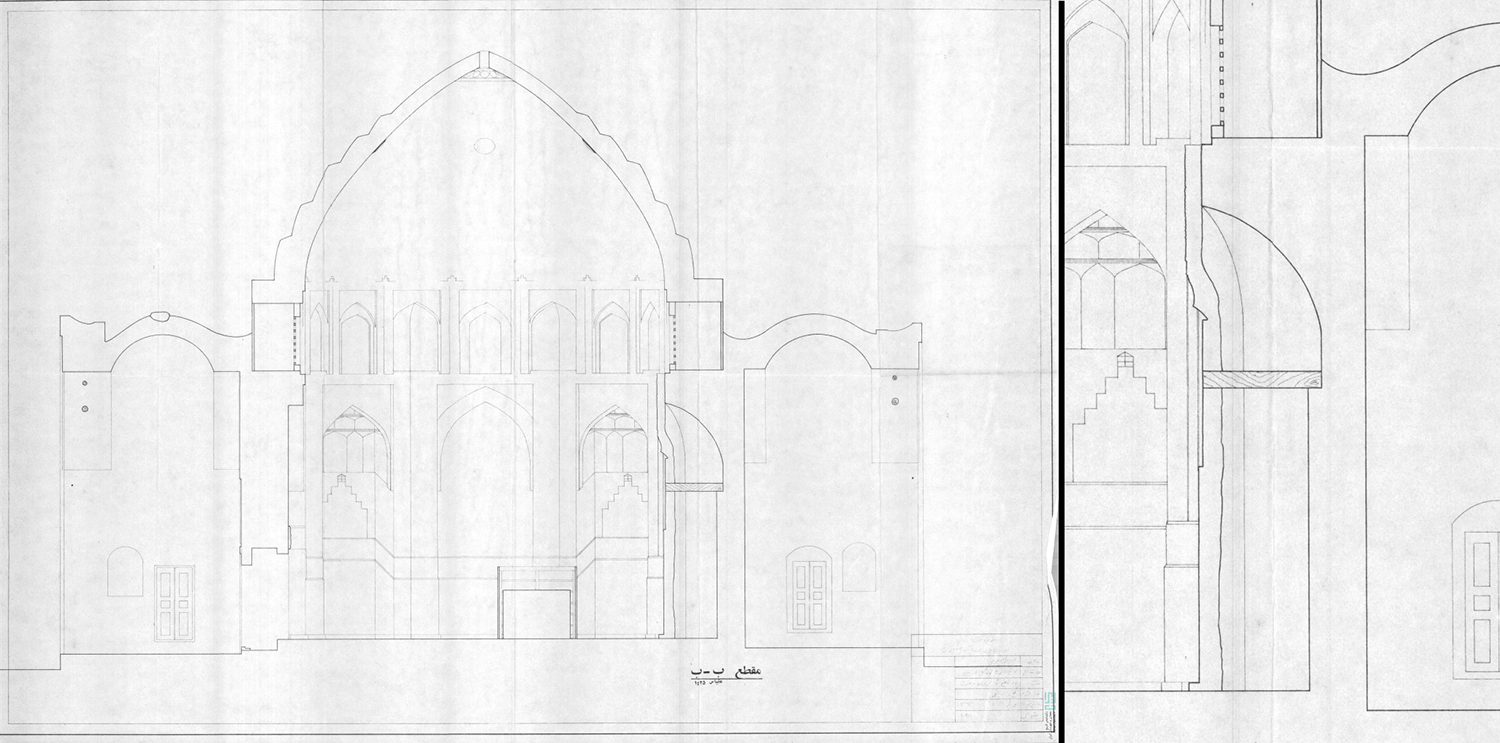

At the conclusion of the project, Ataollah Rafiei produces three detailed architectural drawings, including a west section of the tomb (fig. 234). In this drawing, a large niche is visible behind the void of the mihrab, supported by a horizontal wooden beam. This feature does not appear in the plan drawn by the same architect, raising several questions, including the feasibility of constructing such a large arch on one of the main sides of the building. However, given the overall precision of Rafiei’s drawings, it is possible that this niche did in fact exist behind the mihrab, perhaps as part of an earlier structure predating the commission of the 663/1265 luster mihrab. Clarifying this possibility would require physical access to the void behind the niche.

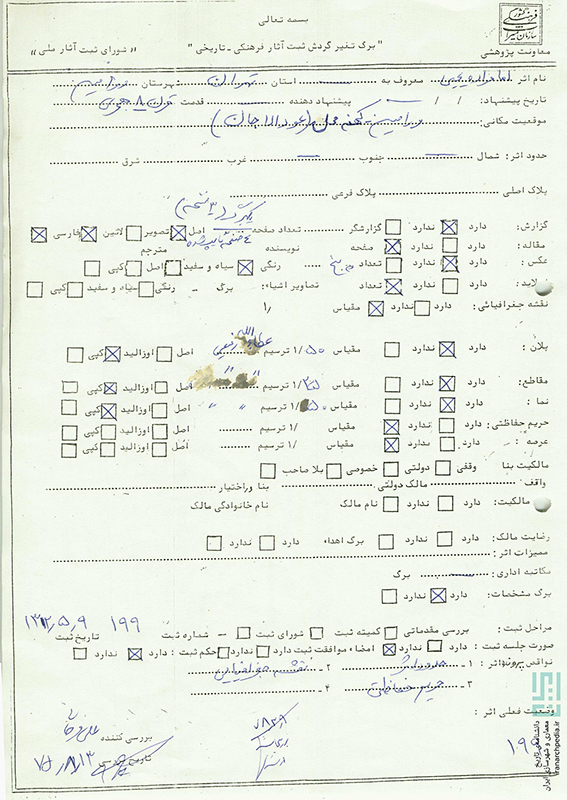

1996: Tehran

The original 1933 registration document of the Emamzadeh Yahya is reviewed by archaeologist Ali Farahani, a specialist at Iran’s Cultural Heritage Organization (سازمان میراث فرهنگی, Sazman-e Miras-e Farhangi). No additional information or clarification is added to the file, and the already muddled record (recall André Godard’s remarks) is confused further (fig. 235). The site is mistaken with the Emamzadeh Yahya in Tehran’s Oudlajan neighborhood (map) (Checklist, no. 24), and a four-page report on the Tehran shrine is attached to the file. Beyond sharing a name, the two sites also once had octagonal towers with conical domes, both of which were demolished. The shrine in Tehran was completely destroyed in 1318 Sh/1939–40 during the construction of a sports court in the adjacent cemetery and later partially rebuilt. By contrast, during the reconfiguration of the Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin in the early 1900s, parts of the complex were completely demolished—the entrance portal, octagonal tower with a conical dome on the west, and other connecting structures—but the tomb of the saint was left standing and enclosed in new features.

The images accompanying the registration document include one photograph of the north side of the tomb after its restoration about a decade earlier (see 1980–85), three interior views (two of replacement tiles in the dado and one of the northwestern corner with stucco decoration), and a detail of the entrance to the Toghrol Tower in Rey (map), confusing the Emamzadeh Yahya with yet another site (fig. 236). No images of the mihrab void or the stripped dado walls of the tomb are included, thus further obscuring the building’s thefts and this significant chapter in its history.

2000: United States

Japanese art historian Tomoko Masuya publishes an article in which she examines the multilayered networks of individuals involved in the acquisition and circulation of Persian luster tiles. She focuses on four key cities and sites: the Shrine of Shaykh ʿAbd al-Samad at Natanz, Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin, tombs in Qom (especially the Emamzadeh ʿAli b. Jaʿfar), and Takht-e Soleyman in northwest Iran. In her account of the Emamzadeh Yahya, Masuya identifies two distinct phases in the “plundering” of the building: “one before 1875, which supplied tiles to Richard [Jules Richard, see fig. 15] and Nicholas [Louis Jean-Baptiste Comte de Nicolas], and another after 1881 and before 1900, which stripped all the remaining tiles.”233 While her discussion of the tomb of Shaykh ʿAbd al-Samad includes a photograph of the stripped dado, the section on the Emamzadeh Yahya only reproduces the tomb’s north side and a star tile from the dado (fig. 238). Regarding the mihrab’s provenance, Masuya uses Sarre (1935) and Wilber (1955) to narrate its transport to Paris in 1900 “by the wealthy owner of the village and sold there.” She then notes that “most tiles passed into the Kevorkian collection and are now in a private collection in the United States.”234 Even at this late stage, just two years before the opening of Shangri La as a museum, the mihrab’s location is not disclosed.

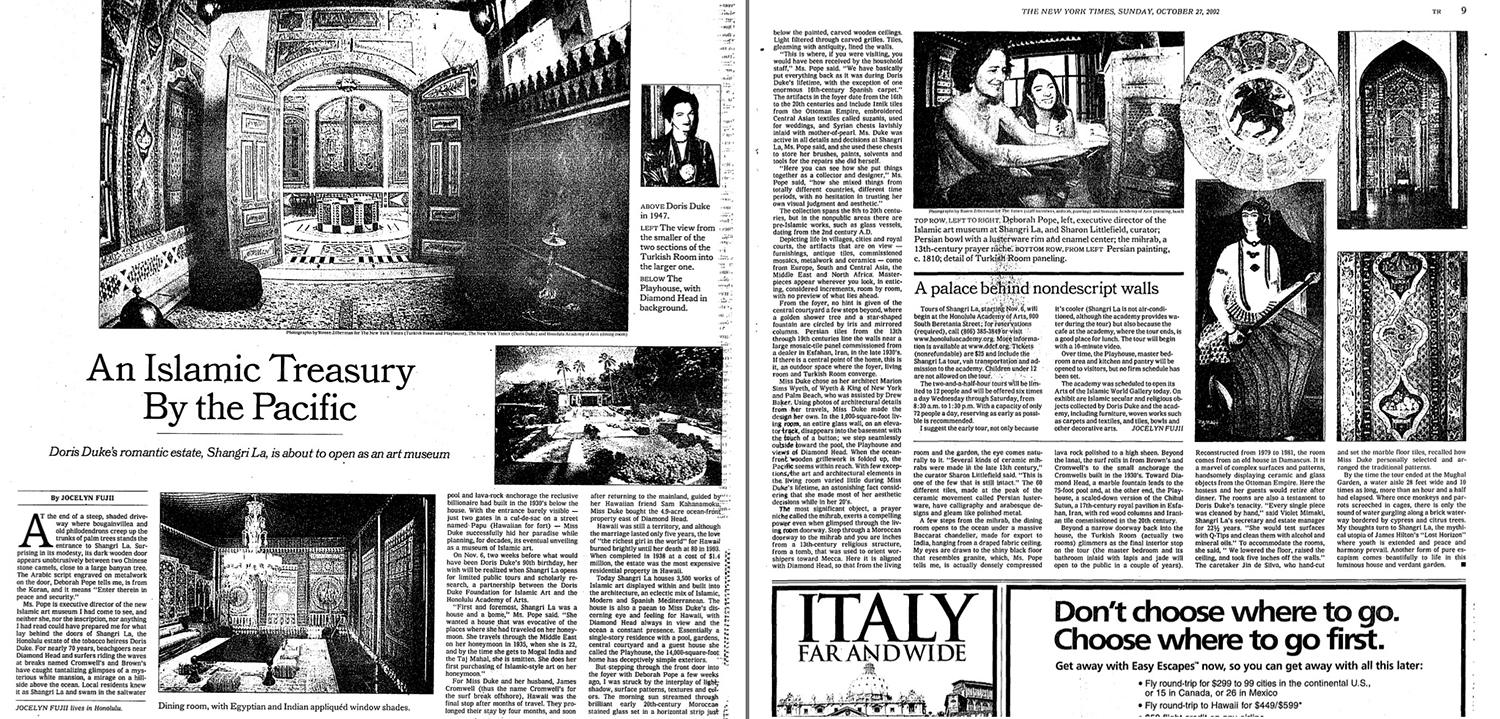

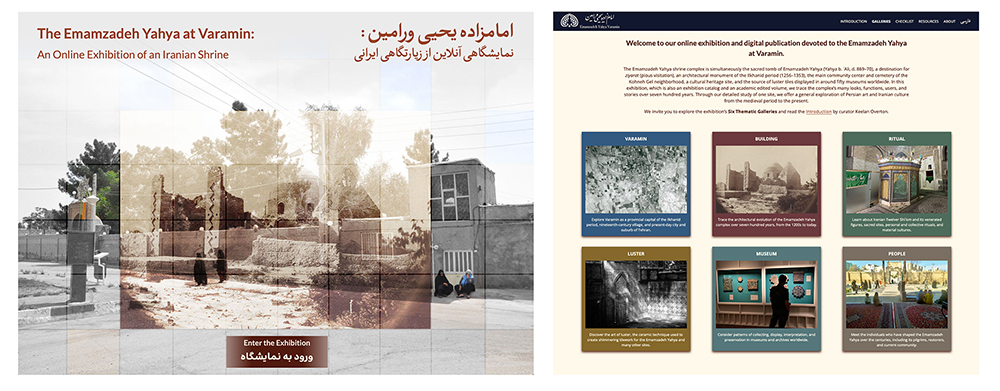

6 November 2002: Honolulu

Shangri La opens as a public museum owned and operated by the Doris Duke Foundation of Islamic Art (DDFIA), as stipulated in Duke’s 1965 second codicil to her will. A short announcement in the Star Bulletin highlights the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab as “the most significant piece of Islamic architecture at Shangri La” and reproduces a color photograph of the “Mecca marker.” A long article in The New York Times also includes an image of the mihrab and describes it as follows (fig. 239):

The most significant object, a prayer niche called the mihrab, exerts a compelling power even when glimpsed through the living room doorway. Step through a Moroccan doorway to the mihrab and you are inches from a 13th-century religious structure, from a tomb, that was used to orient worshippers toward Mecca. Here it is aligned with Diamond Head, so that from the living room and the garden, the eye comes naturally to it.235

To celebrate the museum’s opening, a book is published by curator Sharon Littlefield and includes several color images of the mihrab (fig. 240). The text identifies it as “from the tomb of Imamzada Yahya at Varamin, Iran.”

After sixty-two years of seclusion in Duke’s private home (since late 1940), the mihrab can now be seen firsthand by the public, albeit with some important caveats. Traveling to Hawai‘i is an expensive enterprise for most and an impossibility for many Iranian nationals. Even for locals, visiting the museum is costly and logically complex. General admission is $25, and visitors are required to take a shuttle from the Honolulu Academy of Arts in downtown Honolulu to the Kahala neighborhood (map).236 At the site, visitors take a guided tour led by a docent, and photography is not allowed.

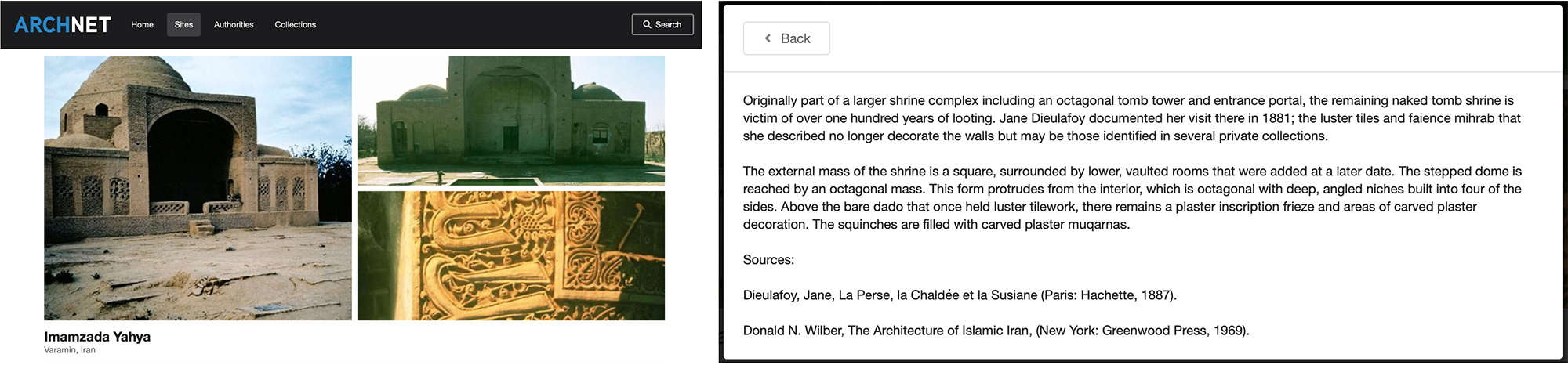

2002–4: Digital Space

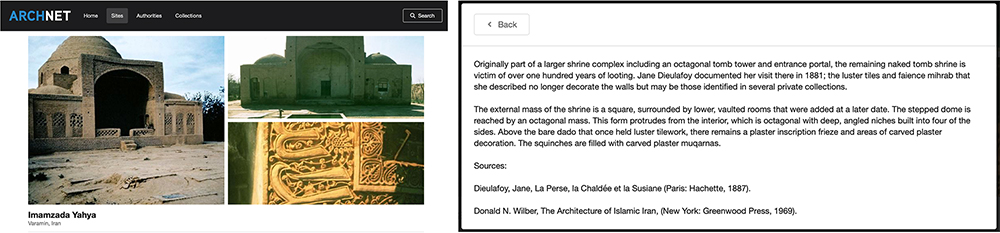

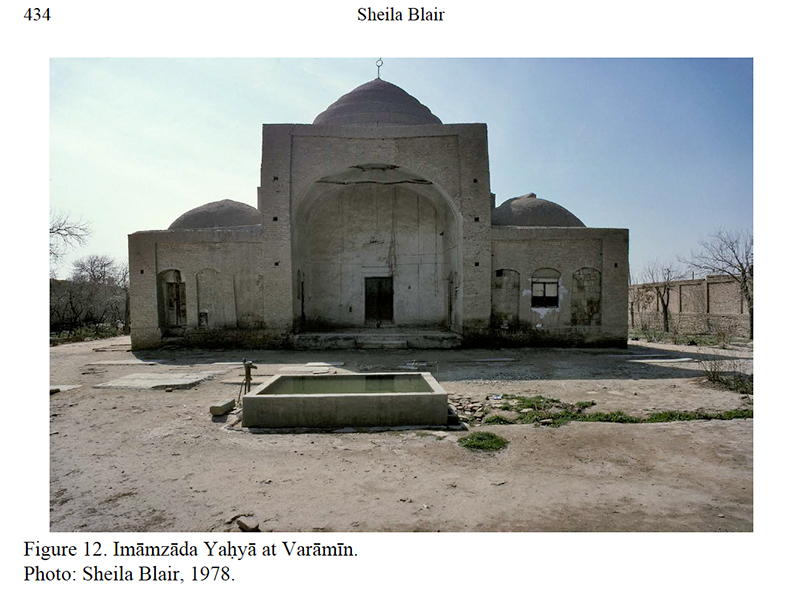

The rise of digital technologies in the early 2000s marks a turning point in the visibility and accessibility of architectural sites and museum collections across the globe. In 2002, the Aga Khan Trust for Culture and Massachusetts Institute of Technology launch Archnet, a free digital library with over 600,000 images dedicated to “the built environment of Muslim societies.” The Emamzadeh Yahya enters this digital library and is represented by three photographs: a view of the back (south) of the tomb probably taken in the 1950s by Baroness Marie-Thérèse Ullens de Schooten (d. 1989) (Photo Timeline, no. 18), a view of the front (north) of the tomb taken in 1978 by Sheila Blair (Photo Timeline, no. 35), and Blair’s detail of the stucco inscription inside the tomb. The accompany text describes the site as follows (fig. 241):

Originally part of a larger shrine complex including an octagonal tomb tower and entrance portal, the remaining naked tomb shrine is victim of over one hundred years of looting. Jane Dieulafoy documented her visit there in 1881; the luster tiles and faience mihrab that she described no longer decorate the walls but may be those identified in several private collections.

This description of the site as a “naked tomb” and “victim of over one hundred years of looting” paints a dismal picture, and the chosen photographs seem reinforce this image, showing it devoid of people, furnishings, and signs of use.237 This limited visual curation gives no indication that the shrine was very much in use during the 1950s to 1970s and comprehensively restored in the early 1980s (see the Photo Timeline).

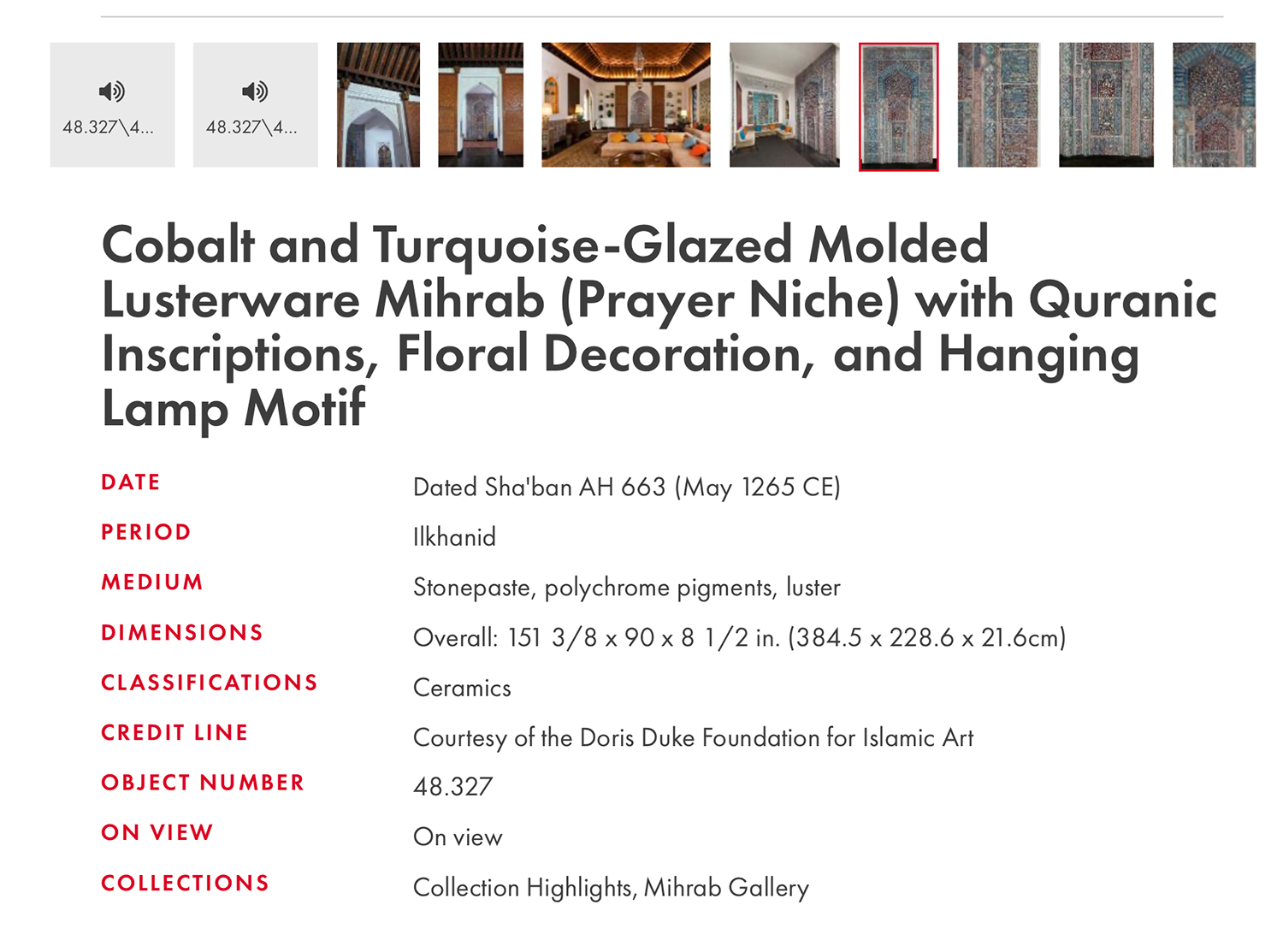

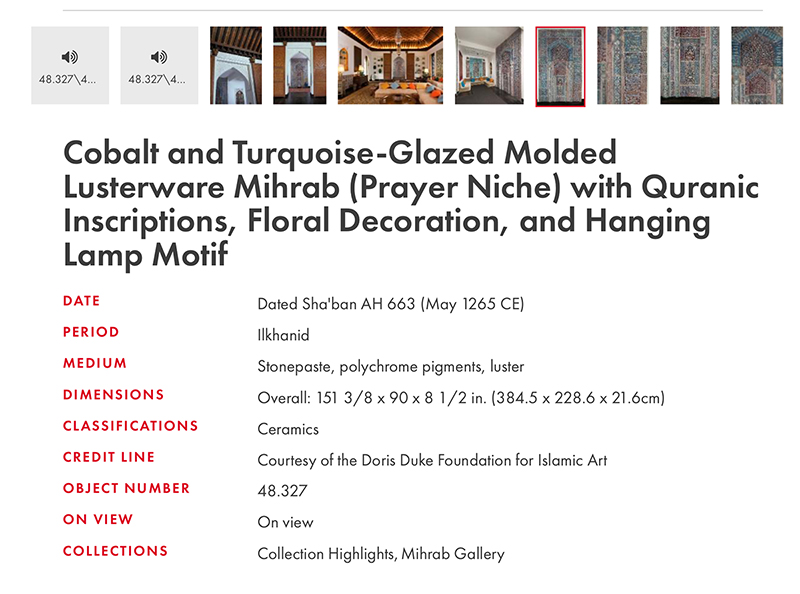

In 2004, Shangri La launches its collection online, and new color images of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab enter the digital space, enabling an appreciation of its polychromatic surfaces (fig. 242).238 The mihrab is now virtually accessible to anyone in the world with an internet connection and is represented by the museum’s accession number 48.327. Its online record shares typical museological and art historical date—its date, period, medium, and dimensions— and recitations of some of its Qur’anic verses contribute an audible dimension. The mihrab’s location in Shangri La is given (the Mihrab Room/Gallery), but its original home in the Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin is not provided.

The Archnet and Shangri La initiatives illustrate both the promises and pitfalls of digital presentation. While the Archnet records helps to increase the shrine’s visibility in international architecture circles, the visual presentation of the site is severely limited (just three photographs), and the accompanying text reinforces Eurocentric narratives of ruin and victimhood. The Shangri La record likewise allows the mihrab to be seen by more international audiences, and in color, but it is reduced to a museum ‘object,’ and its original architectural context is not acknowledged. International consumers of these digital presentations learn nothing about the shrine’s layered histories and present realities or the mihrab’s actual setting and function in the tomb of Yahya b. ʿAli.

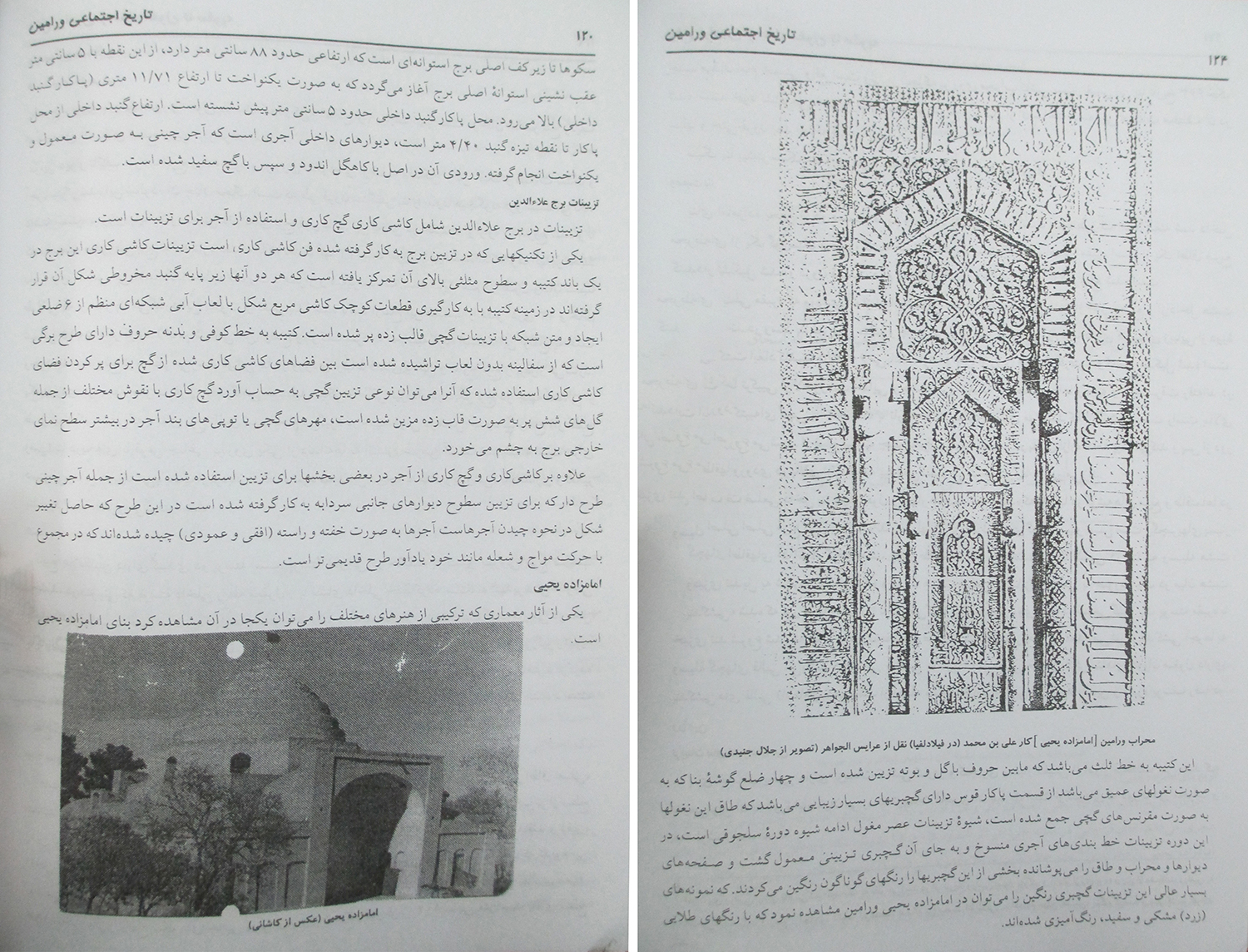

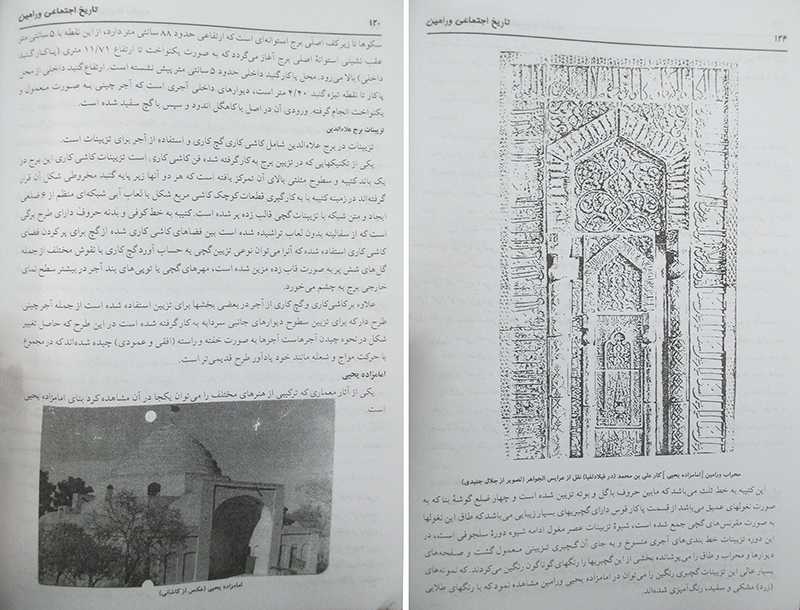

2003: Varamin

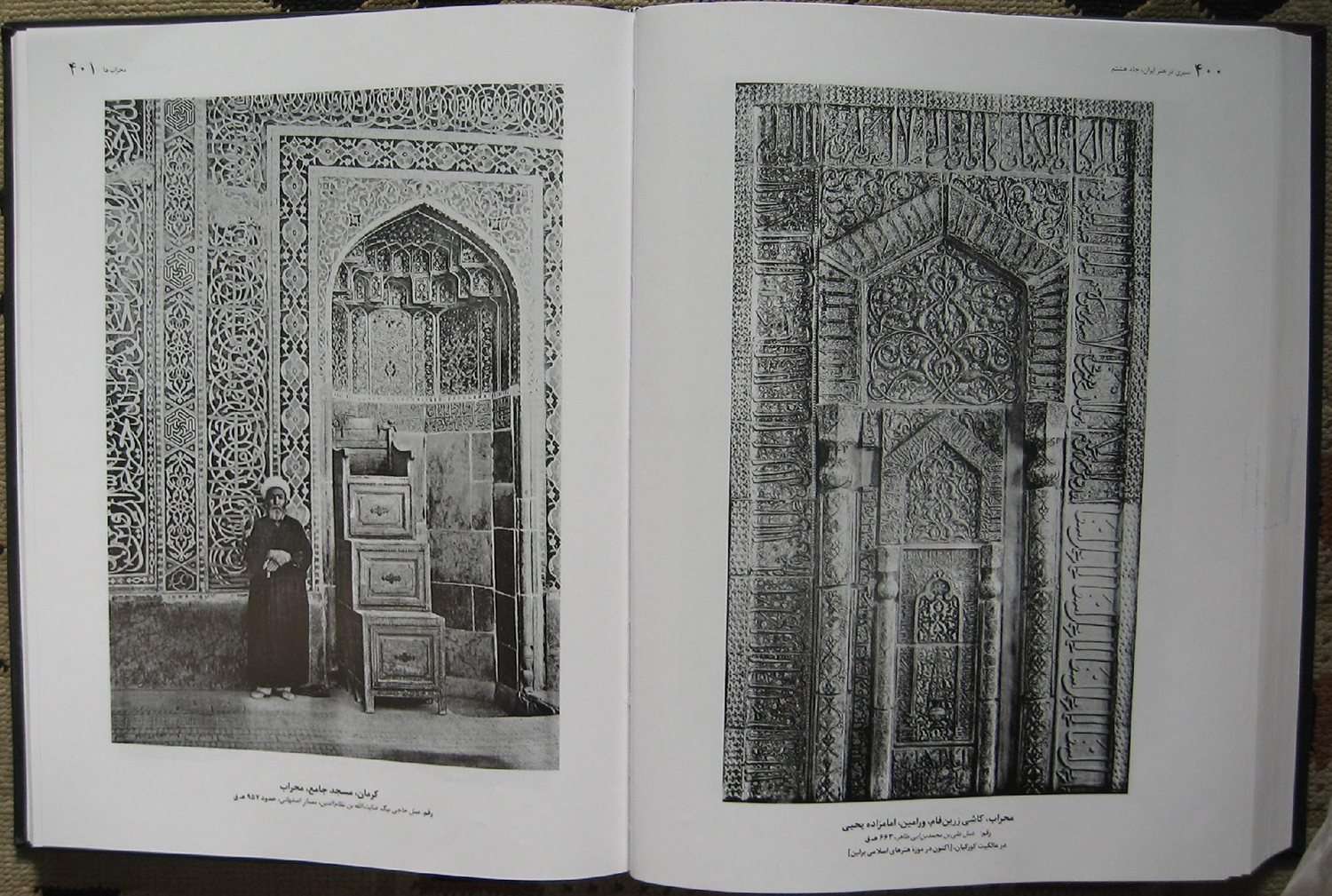

Varamini historian Mohammad Amini (featured in the Oral History) and Iranian archaeologist Homayun Rezvan publish a ten-page entry on the Emamzadeh Yahya in their survey of the social history of Varamin from its origins to the Pahlavi period. The entry compiles the then available information on the shrine’s history, including the biography of Yahya b. ʿAli and the tomb’s decoration, particularly its displaced luster tiles. A photograph of a luster star tile attributed to the tomb appears both within the entry and on the book’s cover (fig. 243). The authors also discuss and reproduce the mihrab, using the photograph taken in the Penn Museum in 1918. In different instances, they cite its location both as the Metropolitan (see 1948–49) and a museum in Philadelphia (موزه فیلادلفیا) (fig. 244, right).239 This inconsistency reflects the ongoing confusion about the mihrab’s whereabouts, despite its presence in Shangri La for over sixty years.

2008–9: Tehran

Seventy years after its first publication in English, A Survey of Persian Art (see 1938–39) is published in Persian under the supervision of Iranian translator and literary critic Sirous Parham (d. 2025). Pope’s chapter on pottery and tilemaking during the Islamic period is translated by archaeologist Fatemeh Karimi (d. 2023).240 The Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab is again reproduced using the photograph taken in the Penn Museum in 1918, and an addition to the original caption by the translator/editor states that the mihrab is now in the Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin (اکنون در موزه هنرهای اسلامی برلین) (fig. 245). This is the third time that the mihrab’s location is inaccurately published in Persian sources (see 1948–49 and 2003).

2010s: Varamin

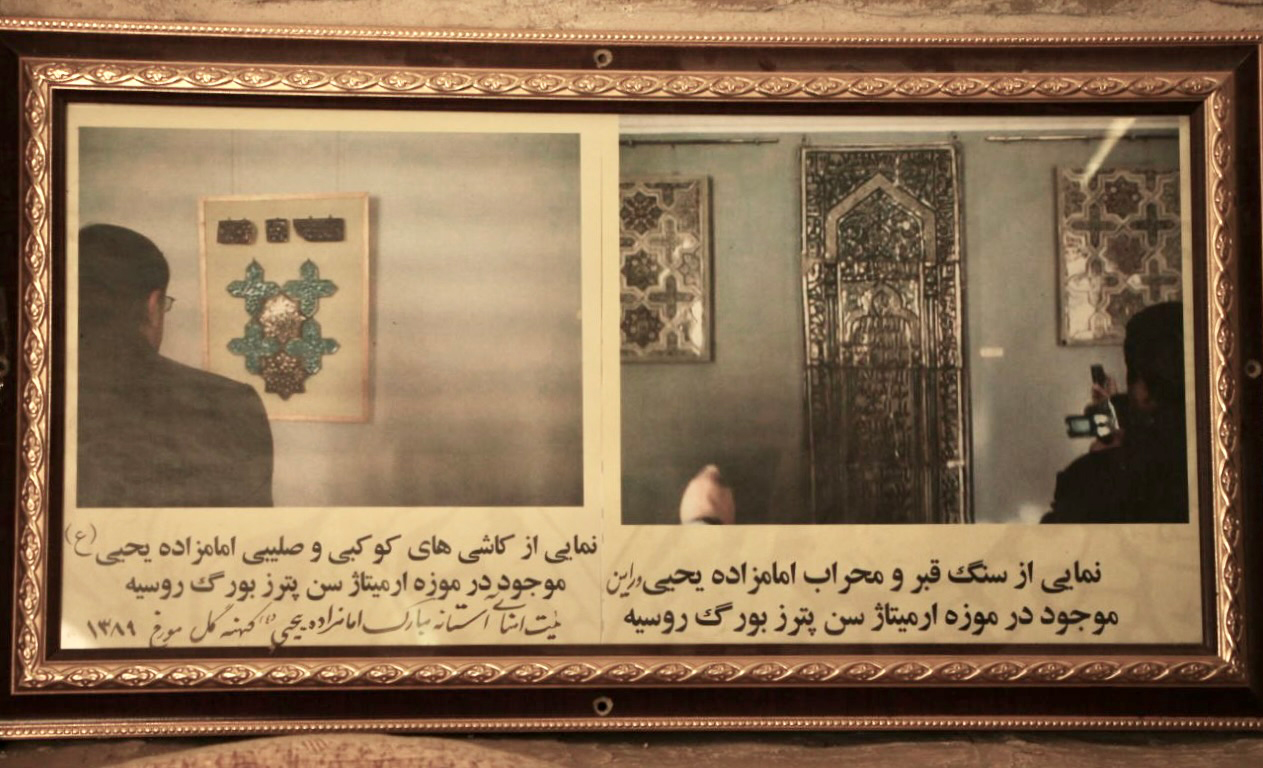

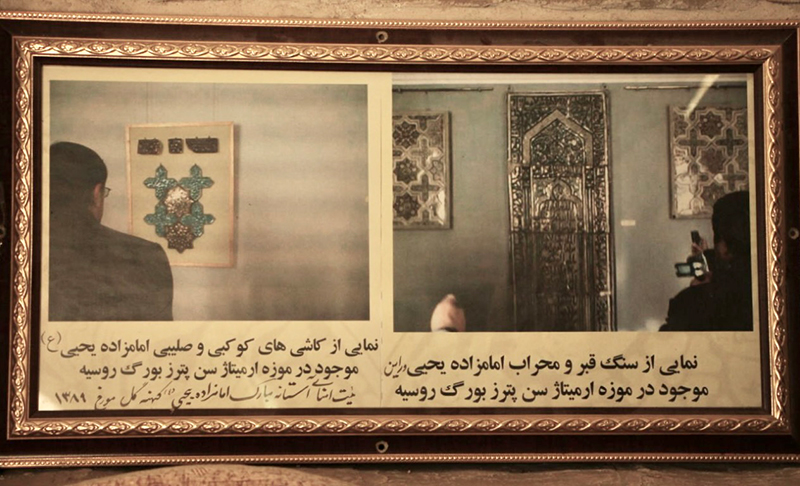

The mihrab void is decorated with a large genealogy of Emamzadeh Yahya flanked by a collage of images visible on either side of the gender-segregated prayer space (fig. 246). At the top are two prints originally published by Jane Dieulafoy in the 1880s: one showing a general view of the Emamzadeh Yahya complex and the other depicting the mihrab in the Emamzadeh Shah Hosayn, erroneously identifying it as the mihrab of the Emamzadeh Yahya, as in Farahvashi’s 1953 translation (fig. 247). These prints were borrowed from Alaoddin Azari’s article on the history and geography of Varamin published in 1368 Sh/1989, underscoring the cyclical repetition of the inaccurate 1953 caption.241 Below are two photographs taken in the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. While the one on the right shows the tombstone panel attributed to Yahya b. ʿAli’s cenotaph flanked by large stars and crosses from the tomb’s dado, the one on the left shows smaller tiles from a different site, incorrectly attributing them to the tomb.

The collage was apparently a gift to the shrine from a domestic guide, probably around 2010.242 A smaller iteration with only the Hermitage photographs carries an inscription by the shrine’s heyʾat-e Omanaʾ (Board of Trustees) dated 1389 Sh/2010, and the captured Hermitage displays can be pinpointed to between 2005–10 (fig. 248).243 The prominent display of the large collage in the mihrab void for at least five years (2013–18) suggests its significance to the shrine’s constituents and their desire to remember the tomb’s displaced tiles and maintain a connection to them. While this collage fostered important layers of memory and acknowledgment—for the original complex and for the tomb’s original tiles—it likely also inadvertently caused some confusion, particularly in how the tomb’s mihrab was seen and perceived. The collage’s confusions underscore how scholarly errors can circulate beyond print publication and academia and have an impact, in this case, entering the tomb itself and spreading among its users.

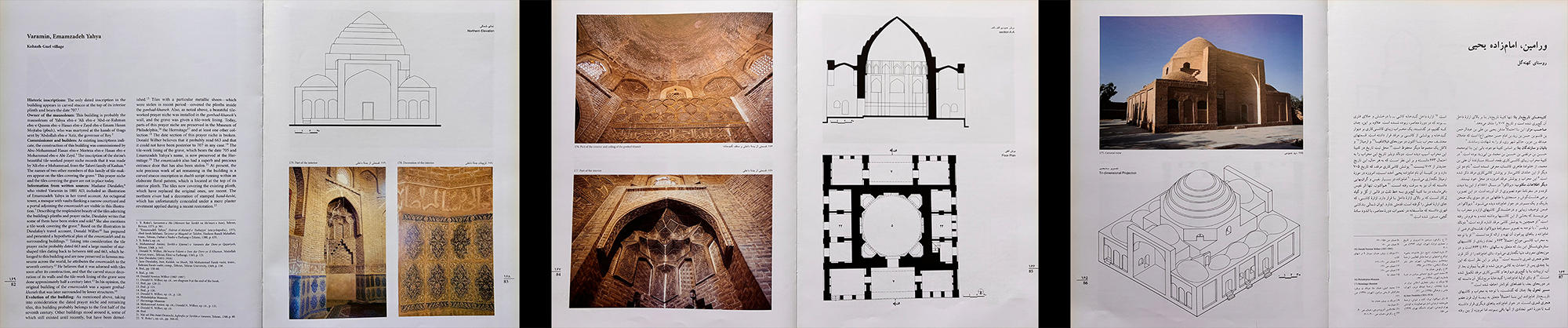

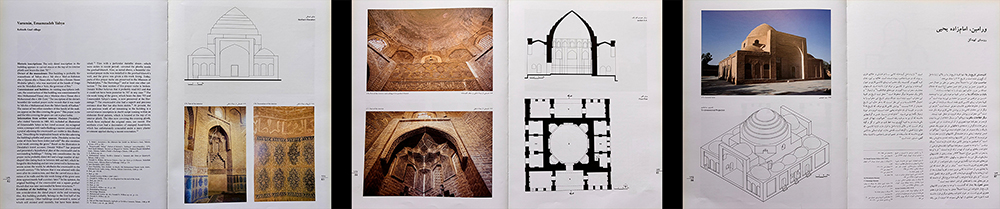

2010–14: Print Publication: Persian

In 2010, the Emamzadeh Yahya is included in Ganjnameh: Cyclopædia of Iranian Islamic Architecture, a twenty-volume series supervised by Iranian architectural historian Kambiz Haji-Qassemi that aims to provide high-quality color photographs, precise architectural drawings (site plans, elevations, façades, and isometric views), and concise historical descriptions of buildings in both Persian and English.244 Three volumes (11, 12, and 13) are dedicated to “Emamzadehs and Mausoleums” (امامزادهها و مقابر), and the Emamzadeh Yahya is one of 126 surveyed sites. Its entry includes four drawings and five photographs, and the quality of the visuals and precision of the text are much improved compared to some earlier publications in Persian (fig. 249). While the thefts of the tomb’s luster tiles and wooden door dated 971/1563 are mentioned in the text, the visual documentation appears to prioritize an idealized image of the tomb, showing passages of intact stucco and tilework rather than areas of major loss. Moreover, the mihrab is still listed as being in the “Philadelphia Museum,” despite its digital presence online since 2004. Noticeably absent in the visual curation are any signs of life or use, whether in the tomb proper or in the large courtyard-cemetery.

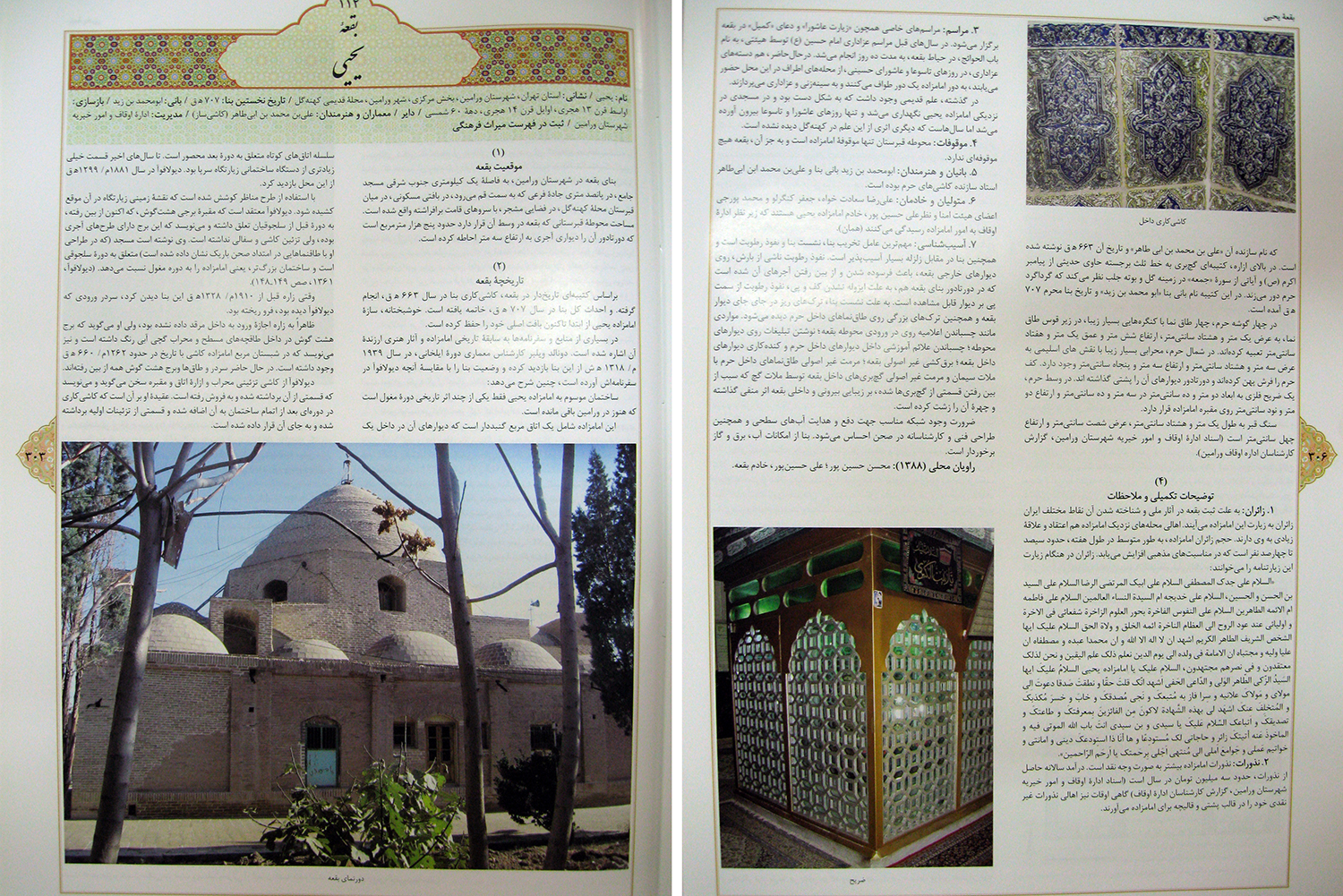

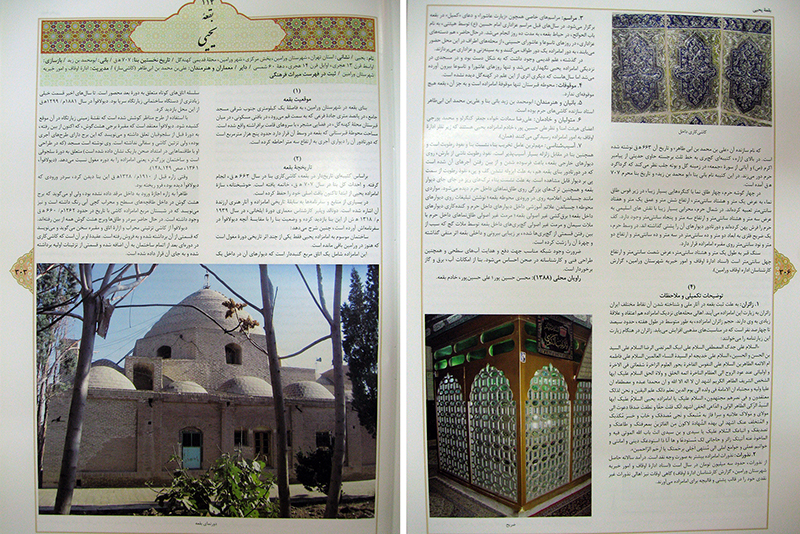

In the same year, the Emamzadeh Yahya also appears in another encyclopedic series, Shomārī az boqʿeh-hā, marqad-hā va mazār-hā-ye ostān-hā-ye Tehran va Alborz (A Catalogue of Shrines, Tombs, and Mausoleums in the Provinces of Tehran and Alborz), edited by Iranian politician and lawyer Hasan Habibi (d. 2013) and published by the Iranology Foundation (Bonyad-e Iranshenasi). The volume is dedicated to funerary architecture and focuses on five cities in Tehran province, including Varamin. Compared to the Ganjnameh entry, this one integrates historical background with details about restoration campaigns and also includes a section on the current condition of the site. More importantly, it provides extensive information about the lived experience of the shrine: the number of pilgrims, full text of the ziyaratnameh (pilgrimage prayer text), annual ceremonies, names of custodians, and even a damage analysis of the site. One of the three photographs depicts the most important ritual furnishing in the tomb, the zarih (screen enclosing the cenotaph of the saint) (fig. 250). This comprehensive documentation appears to be the result of oral history interviews conducted with the building’s guardians and regular users.

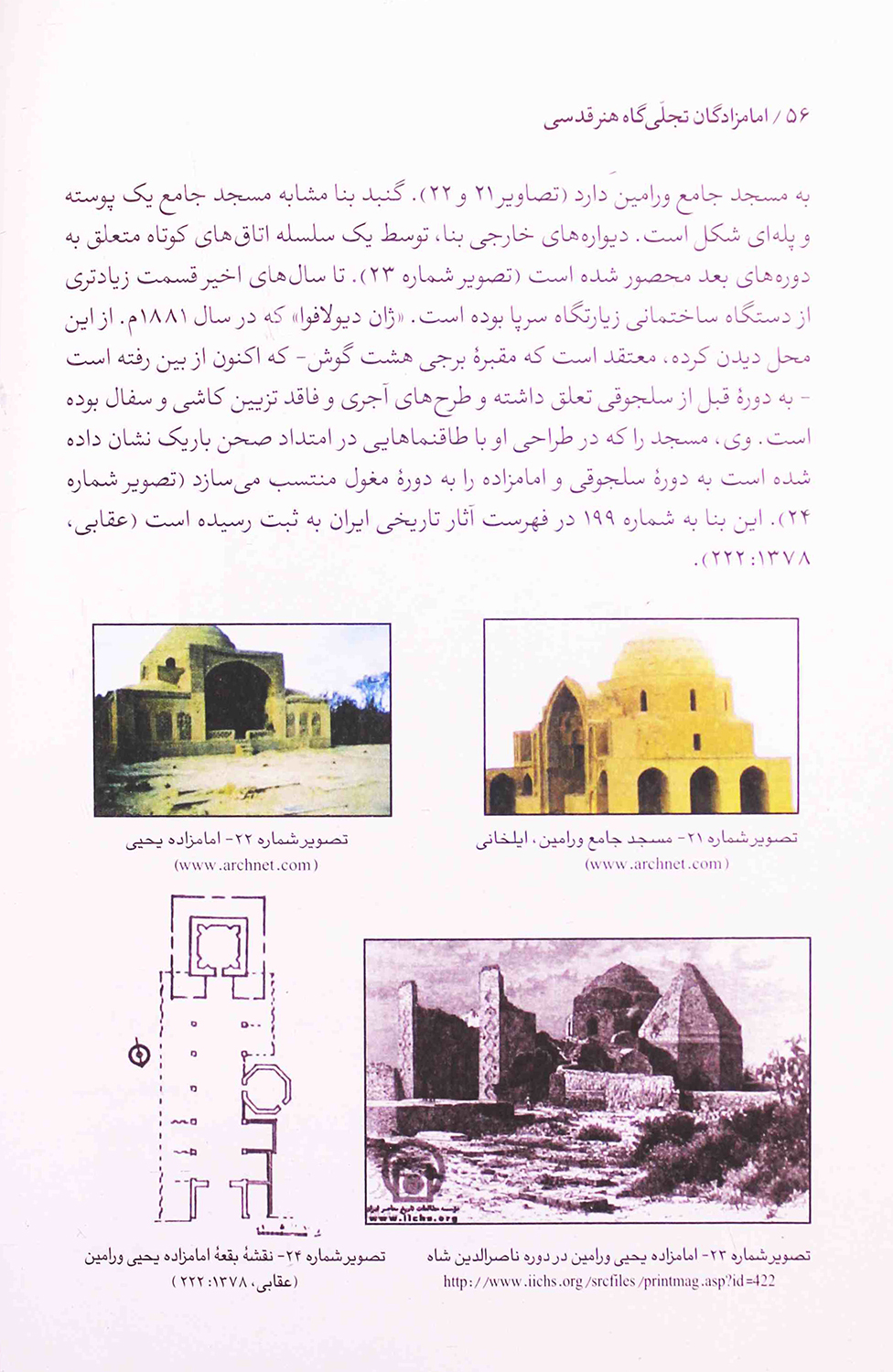

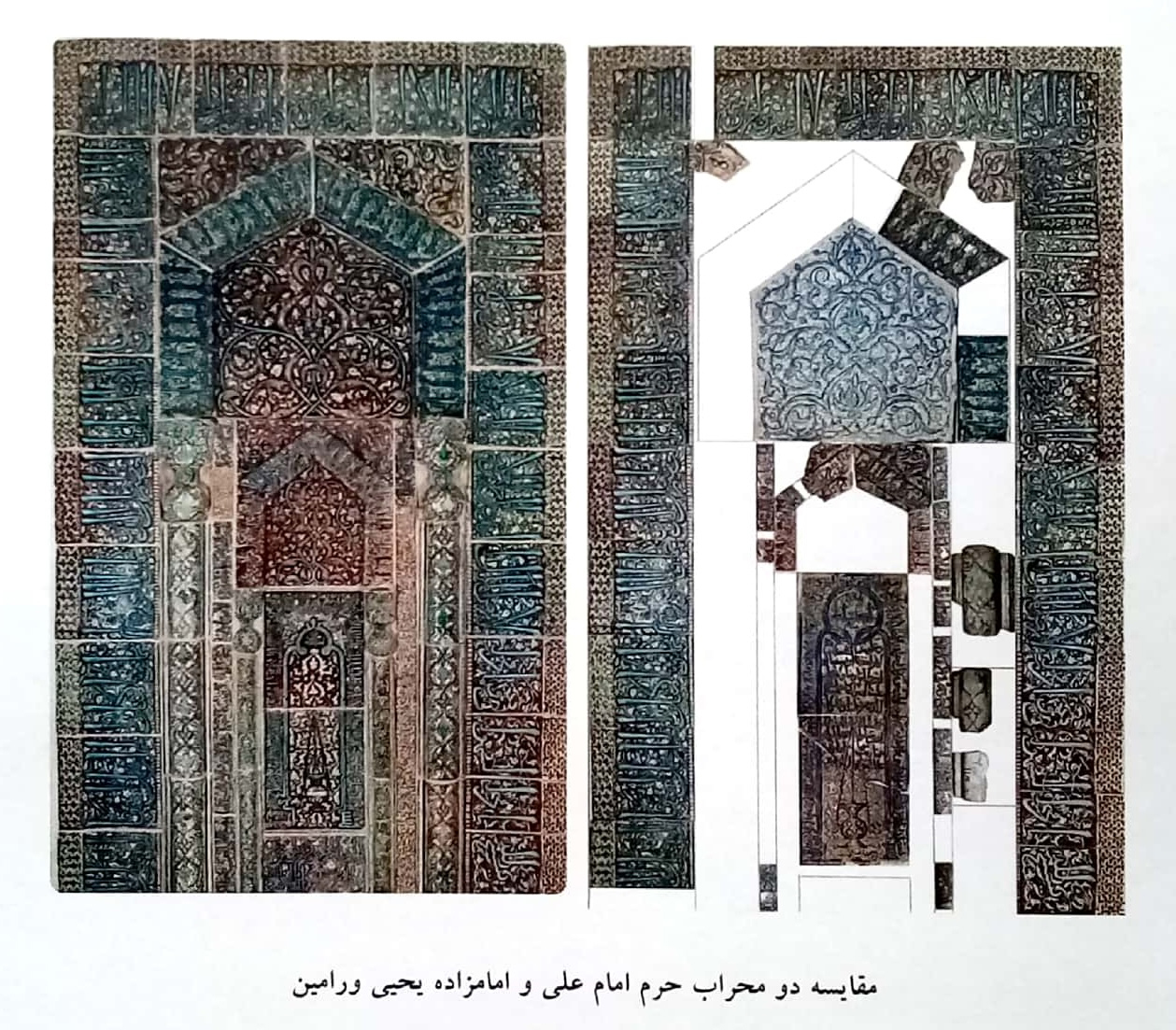

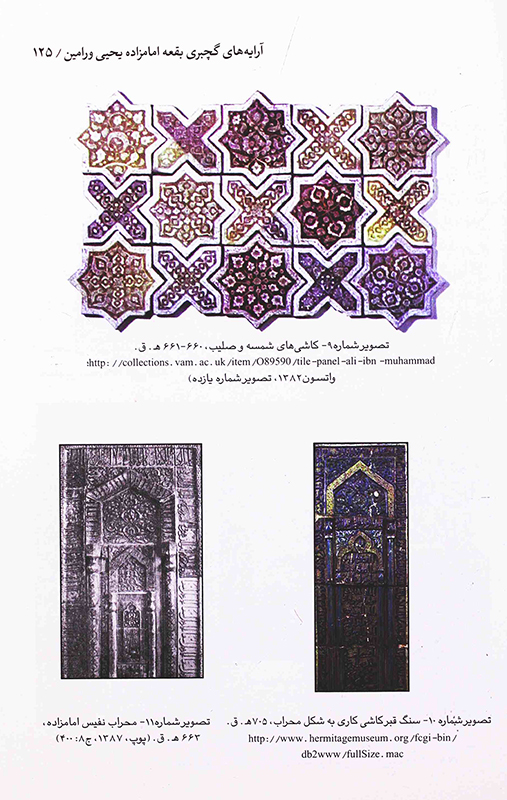

Attention to the Emamzadeh Yahya continues to grow in Persian-language scholarship, and it appears in two articles published in the proceedings of The First International Conference on Emamzadehs (نخستین کنگره بینالمللی امامزادگان), held in Esfahan in September 2013 and focused on the ornamentation of sacred shrines (بقاع متبرکه). In their stylistic comparison of decorative elements in the Emamzadeh Jaʿfar in Esfahan (map) and Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin, art historians Marzieh Parvaresh and Shadabeh Azizpour include images originally published by Jane Dieulafoy and Donald Wilber that continue to circulate widely among Iranian scholars, albeit a few degrees removed from the original texts (fig. 251). They also reproduce a photograph of the back of the tomb taken by Baroness Ullens de Schooten likely in the 1950s. This image’s inclusion on Archnet (see 2002–4) makes it readily accessible to researchers in Iran.

In their article on the stucco decoration of the Emamzadeh Yahya, art historians Bahareh Taghavi Nejad and Sedigheh Mirsalehian reproduce images of the mihrab, cenotaph cover, and a panel of luster star and cross tiles (fig. 252). While the last two images are taken from the Hermitage and V&A websites, the mihrab one is borrowed from the Persian translation of A Survey of Persian Art (see 2008–9), meaning the now very antiquated photograph taken in the Penn Museum in 1918. This suggests that Shangri La’s website—and by extension the mihrab’s presence in Hawai‘i—is not yet known to some scholars in Iran.

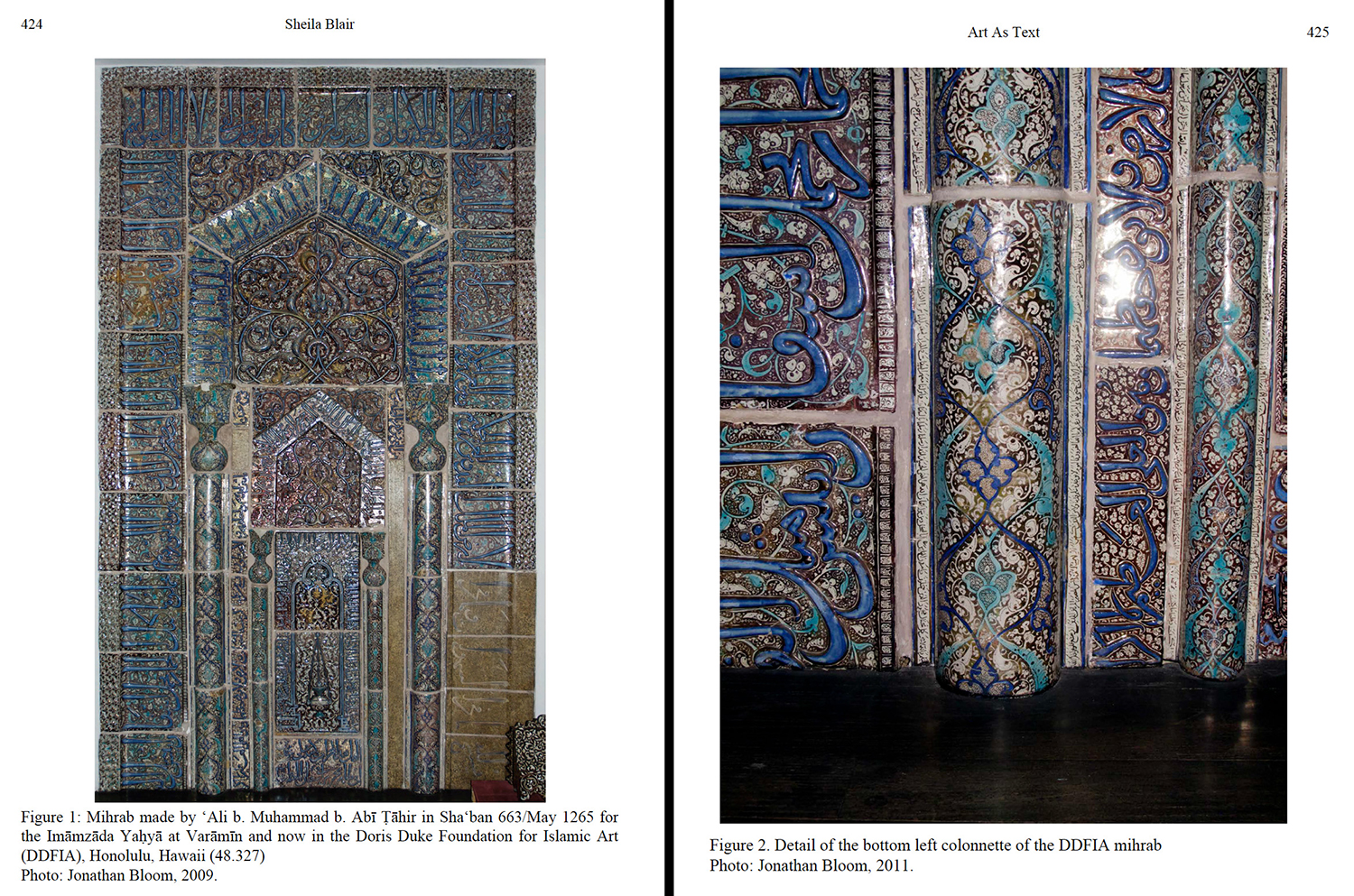

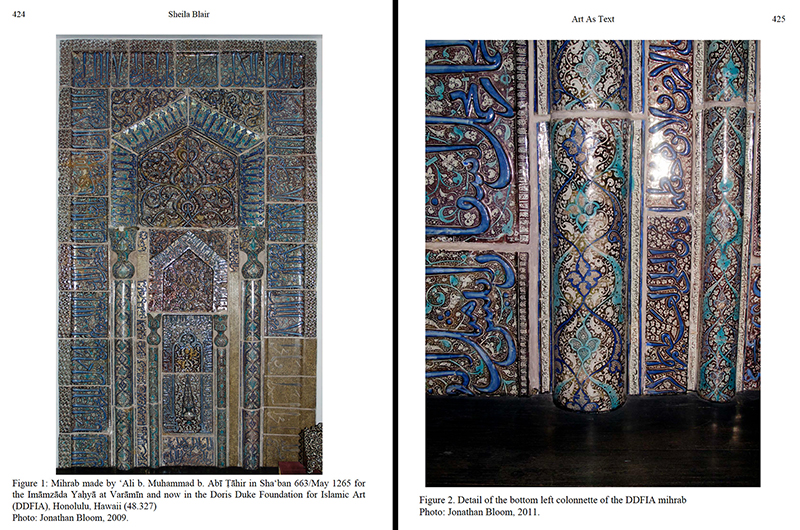

2014–16: Print Publication: English

In 2014, more than seventy years after its arrival at Shangri La, Canadian-American art historian Sheila Blair publishes the first detailed study of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab in English. Blair highlights some of the mihrab’s missing and jumbled tiles, contextualizes it in relation to five other surviving luster mihrabs, and reproduces many recent color photographs taken during her residencies and visits to Shangri La (2009, 2011, and 2015). She also publishes the view of the tomb that she took during her visit to Varamin in 1978, reproducing it above the print after Dieulafoy’s photograph and across from Wilber’s hypothetical plan (1955) (fig. 253).

In 2016, Blair publishes an article considering the broader historical context of Ilkhanid Varamin, the patron of the Emamzadeh Yahya, and why the shrine was built and elaborately decorated with luster tilework. The study argues for the shrine’s utility in writing the provincial history of Mongol Varamin, and the 1978 photograph of the north side of the tomb is again reproduced (fig. 255).

Between Blair’s two articles and the entry on the shrine on Archnet (see 2002–4), the 1978 photograph becomes the main way that the Emamzadeh Yahya is seen and recognized by many international researchers, especially those using English-language sources. For Persian-speaking audiences, Blair’s publications become a key reference for realizing that the mihrab is preserved in Honolulu, Hawai‘i in the Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art.

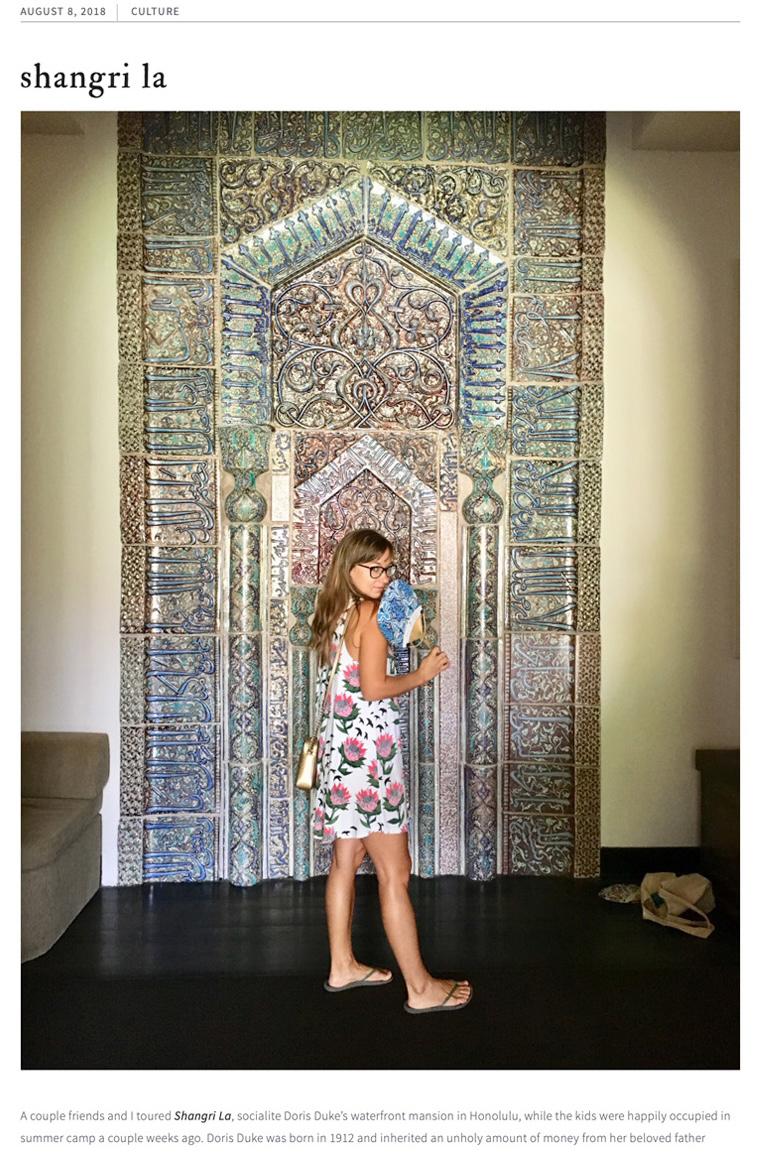

2018: The Museum: Denver, Honolulu, and London

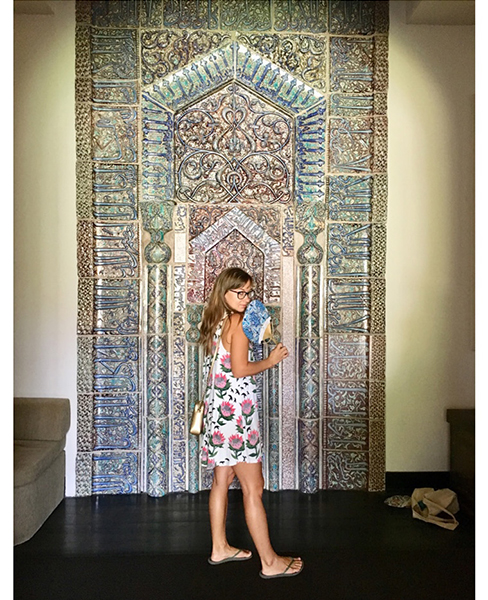

The mihrab’s border tile in the Denver Art Museum is exhibited in “Linking Asia: Art, Trade and Decoration” (17 December 2017–1 April 2018). The catalog maintains that the tile “likely once adorned the walls of a mosque” (fig. 256). Meanwhile, the mihrab continues to be a highlight of tours to Shangri La, and the lifting of a previous policy prohibiting photography means that visitors can pose for selfies and photographs (fig. 257). One visitor posts a photograph standing before the mihrab and writes the following:

An Australian on our tour asked if having the mihrab was offensive to Muslims or Middle Easterners. The tour guide said the museum is sensitive to that, but the usual reaction is one of happiness and acknowledgement that if it had remained in Iran it probably would have been destroyed.

The last comment seems to suggest that Iran’s cultural heritage is better off outside of the country, a presumption that diminishes its extensive museum system and fails to recognize that several luster mihrabs and many other architectural ensembles and invaluable works of art are preserved in Iranian museums. Moreover, it was during the First and Second World Wars that the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab faced some of its greatest risks, as well as during its many transports, installations, and deinstallations for exhibition in American and European museums.

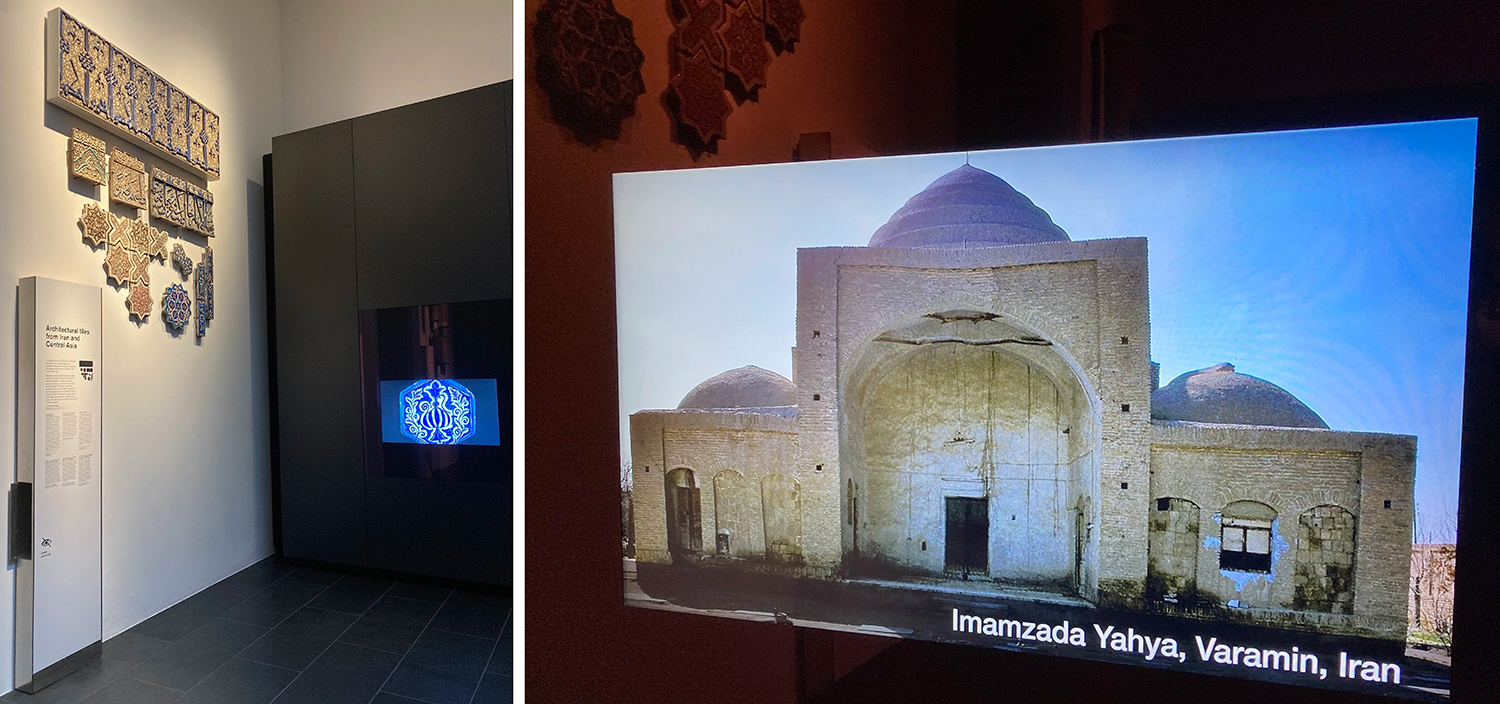

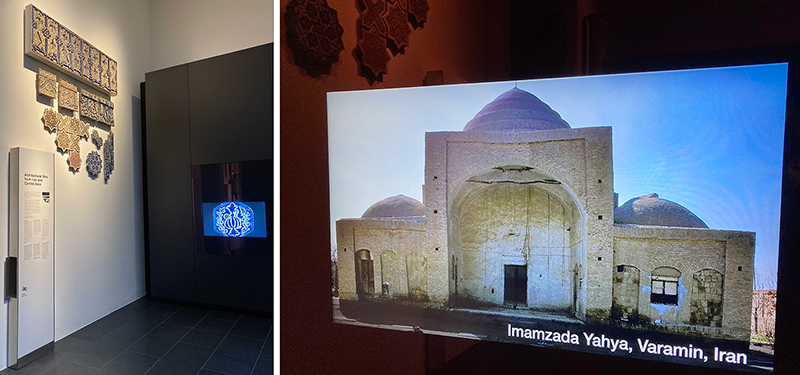

In October, the Emamzadeh Yahya’s luster tiles and the shrine appear in the British Museum’s renovated galleries of Islamic art.245 Star and cross tiles from the dado are mixed with tiles from other sites in a display entitled “Architectural Tiles from Iran and Central Asia,” and an adjacent monitor shows a video of photographs of some of the source buildings. The chosen photograph of the Emamzadeh Yahya is again Sheila Blair’s 1978 view of the tomb’s entrance (fig. 257). A longer film posted on the museum’s website, Tiles of the Islamic World, repeats this photograph with a fade of a single star tile over the entrance. Comparable animations follow of the luster tiles attributed to the Emamzadeh Jaʿfar at Damghan and the Shrine of ʿAbd al-Samad at Natanz. In all cases, the focus is on the exterior, and the true contexts of the tiles are not shown. In the case of the Natanz tomb, the space is like a frozen crime scene.

These three cases studies—Denver, Honolulu, and London—underscore the limited presentation and often misperception of the Emamzadeh Yahya and its luster tiles in international museums. A tile from the mihrab remains physically and conceptually isolated from the ensemble, the mihrab is presumed to be ‘safer’ on foreign soil and serves as an aesthetic backdrop for photography, and the shrine is represented through a single photograph taken forty years earlier.246

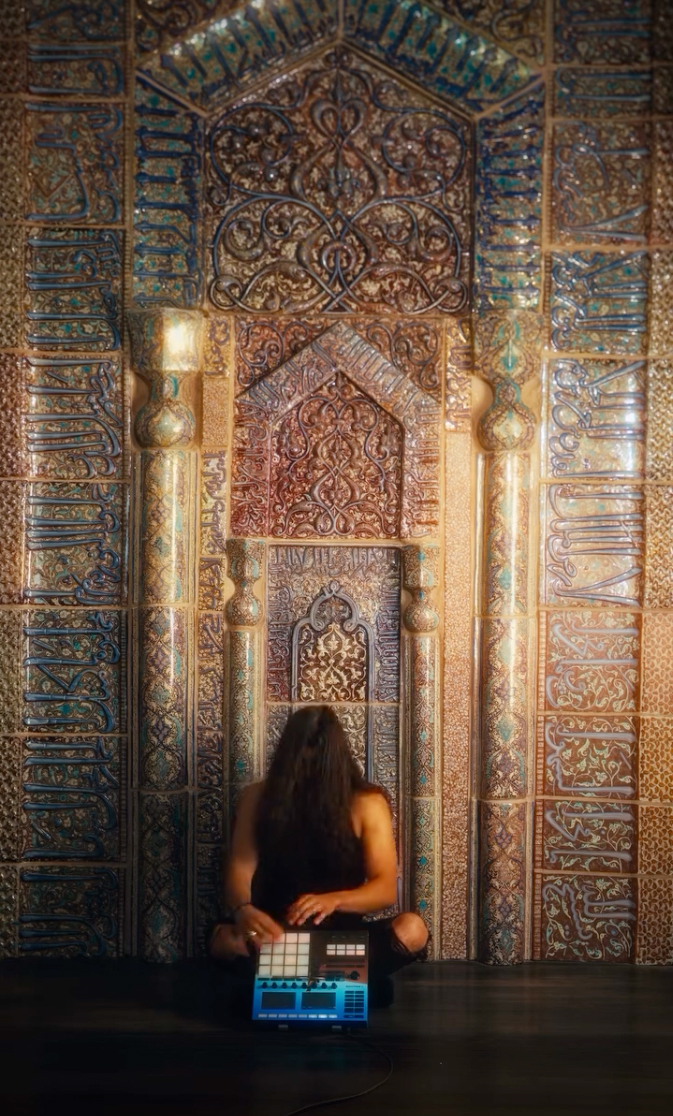

February 2018: Virtual Tour

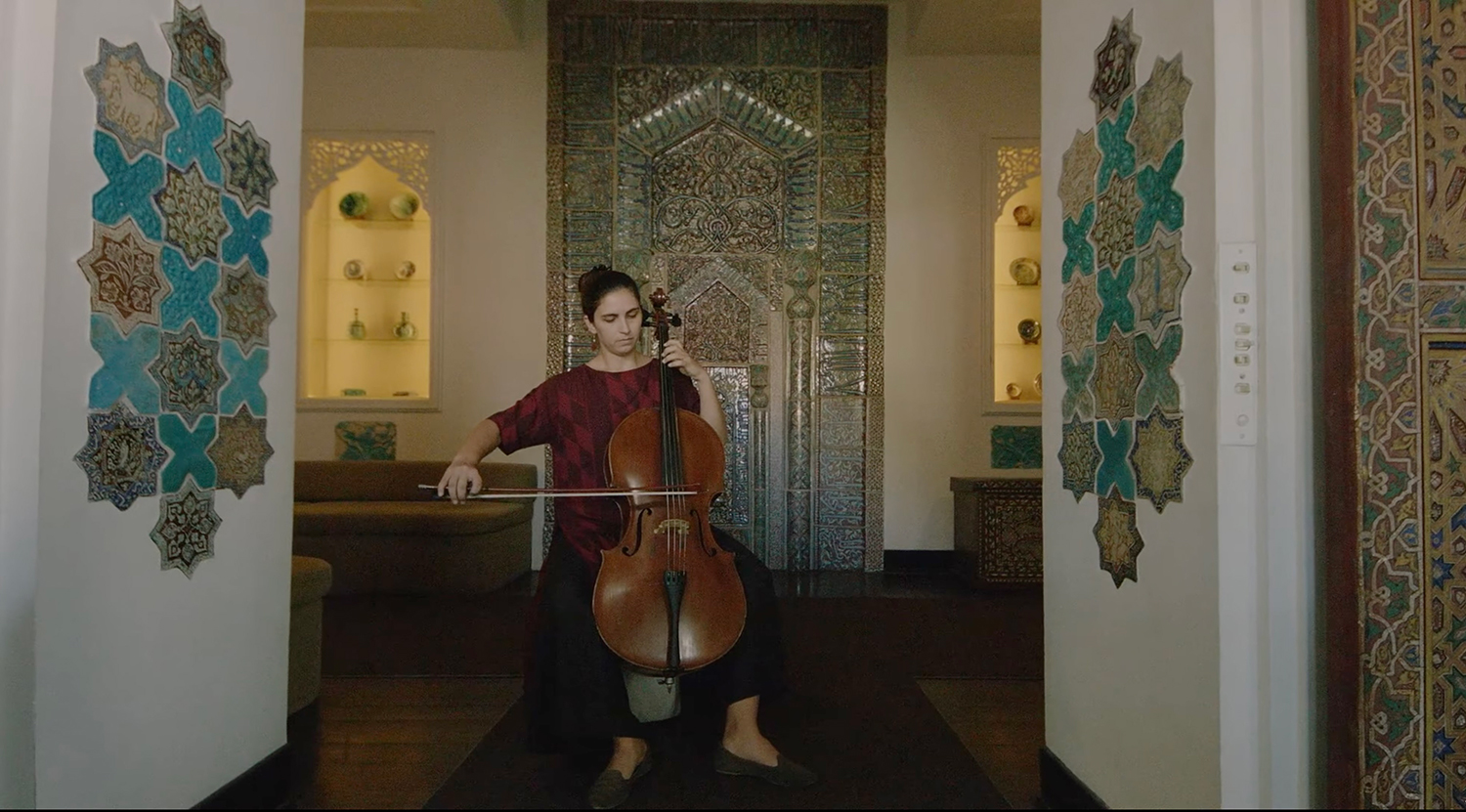

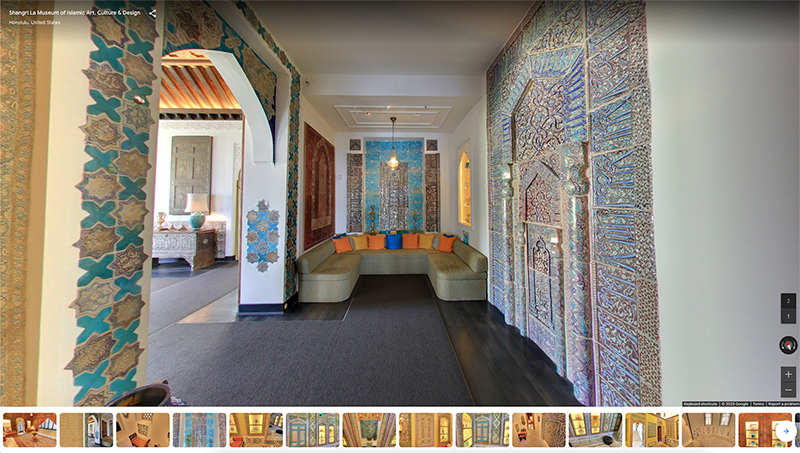

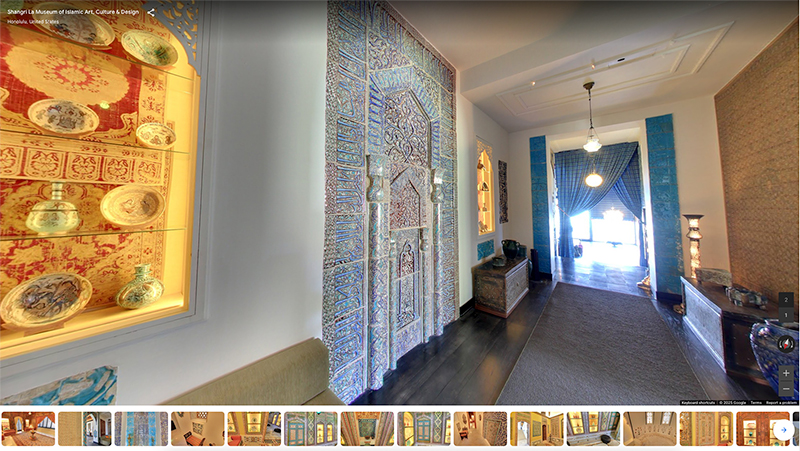

Shangri La partners with Google Arts and Culture to create a virtual tour. Given the museum’s remote location and Hawai‘i’s general inaccessibility, this digital initiative facilitates broader public engagement with the property and allows users with internet access to see the setting of the mihrab. One of the most striking aspects of the Mihrab Room, especially as experienced virtually, is the sheer number of medieval Persian tiles scattered throughout the space.

2018–22: Print Publication and Digital Resources

Images of the mihrab on Shangri La’s website gradually enter Persian-language scholarship on luster tiles. In 2018, art historians Farzane Farrokhfar and Mohammad Zohdi publish an article analyzing the composition of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab (fig. 261). In 2019, conservator Alireza Bahraman publishes a study on the highly fragmented luster mihrab of the al-Raʾs Mosque in Najaf (map). Drawing on the color image of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab, which closely resembles the Najaf one, he proposes a hypothetical reconstruction and attempts to reconnect the remaining fragments in storage at the Shrine of Emam ʿAli (fig. 262).

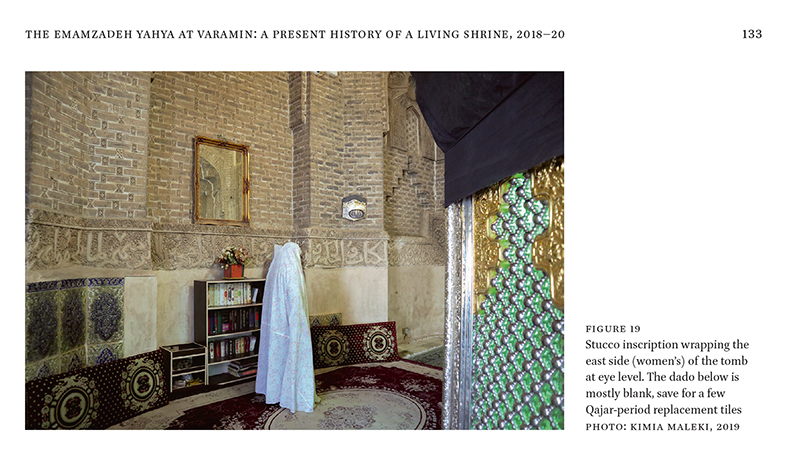

In late 2020, based on site visits in 2018 and 2019, American art historian Keelan Overton and Iranian art historian Kimia Maleki publish an article in which they consider aspects of the present life of the Emamzadeh Yahya complex. Attempting to balance existing academic perceptions and reproductions, the authors deliberately reproduce photographs showing the shrine’s current use, users, and ritual decorations and furnishings (figs. 263–264). An emphasis is placed on the mihrab void and the varied materials filling the space at the time, including the genealogy of Yahya b. ʿAli and the collage mixing prints after Dieulafoy and Hermitage photographs (see fig. 246). The article is published in Brill’s newly launched open-access Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World, meaning the images are widely available online.

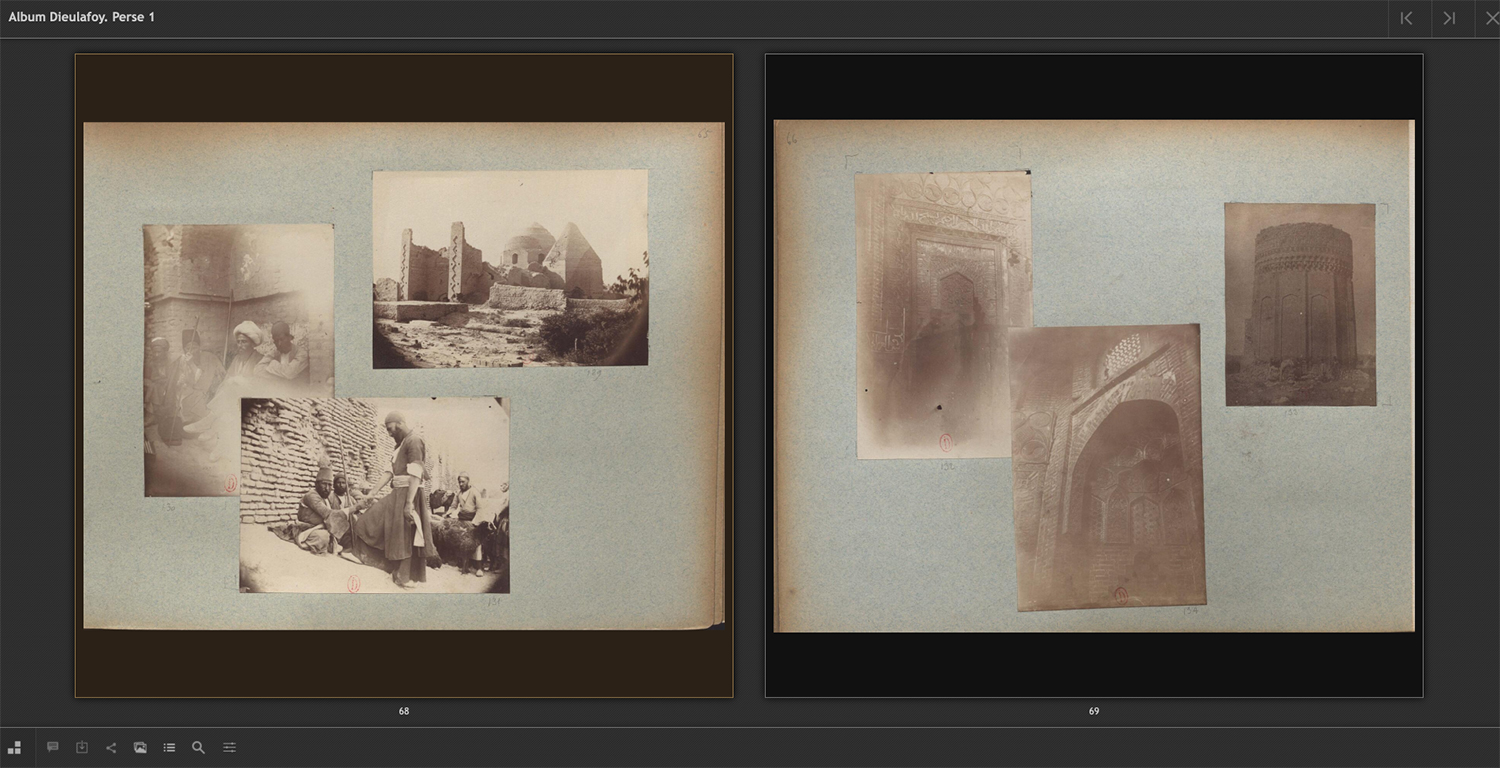

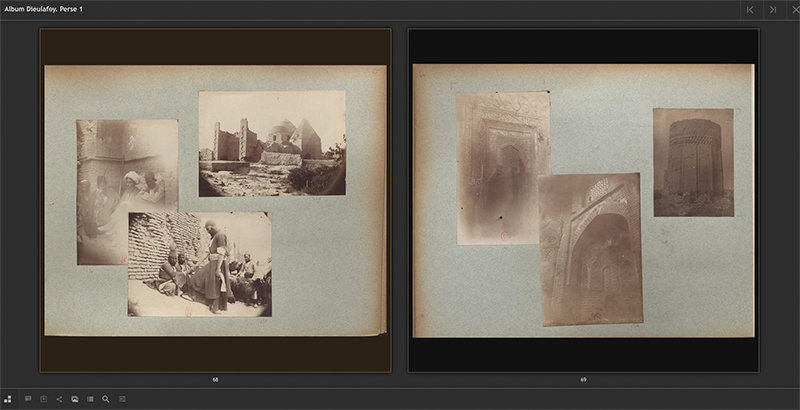

In the fall of 2021, the Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art (INHA) in Paris releases complete digitizations of Dieulafoy’s six photography albums (see this blog). As a result, anyone with an internet connection can now see her original photograph of the Emamzadeh Yahya complex, hitherto known only through its woodcut reproduction, as well as her unpublished photograph of the mihrab in situ. This a seminal moment in the public’s ability to re-see the complex before its major reconfiguration in the early 1900s and to re-see and re-contextualize the mihrab in the tomb.

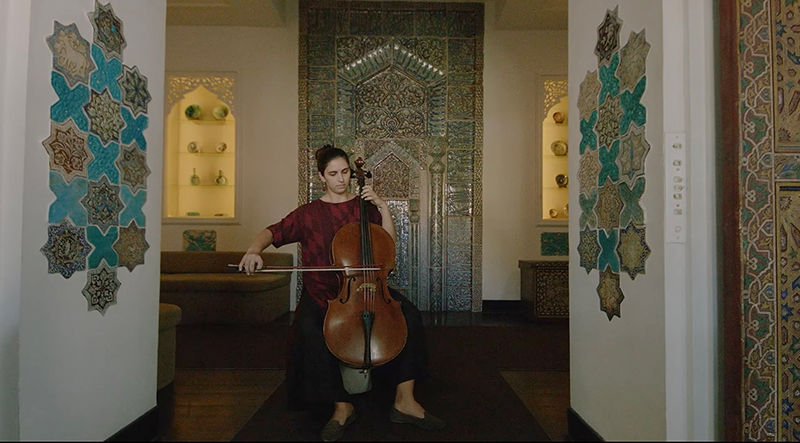

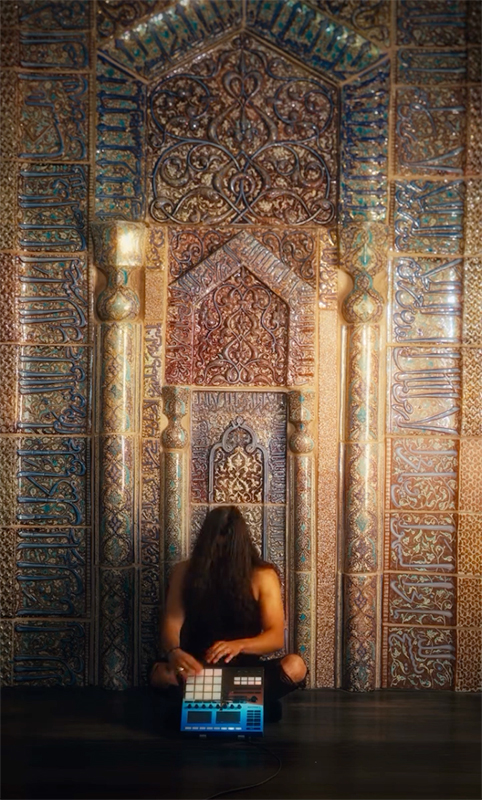

2021–24: Artistic Response/Performance

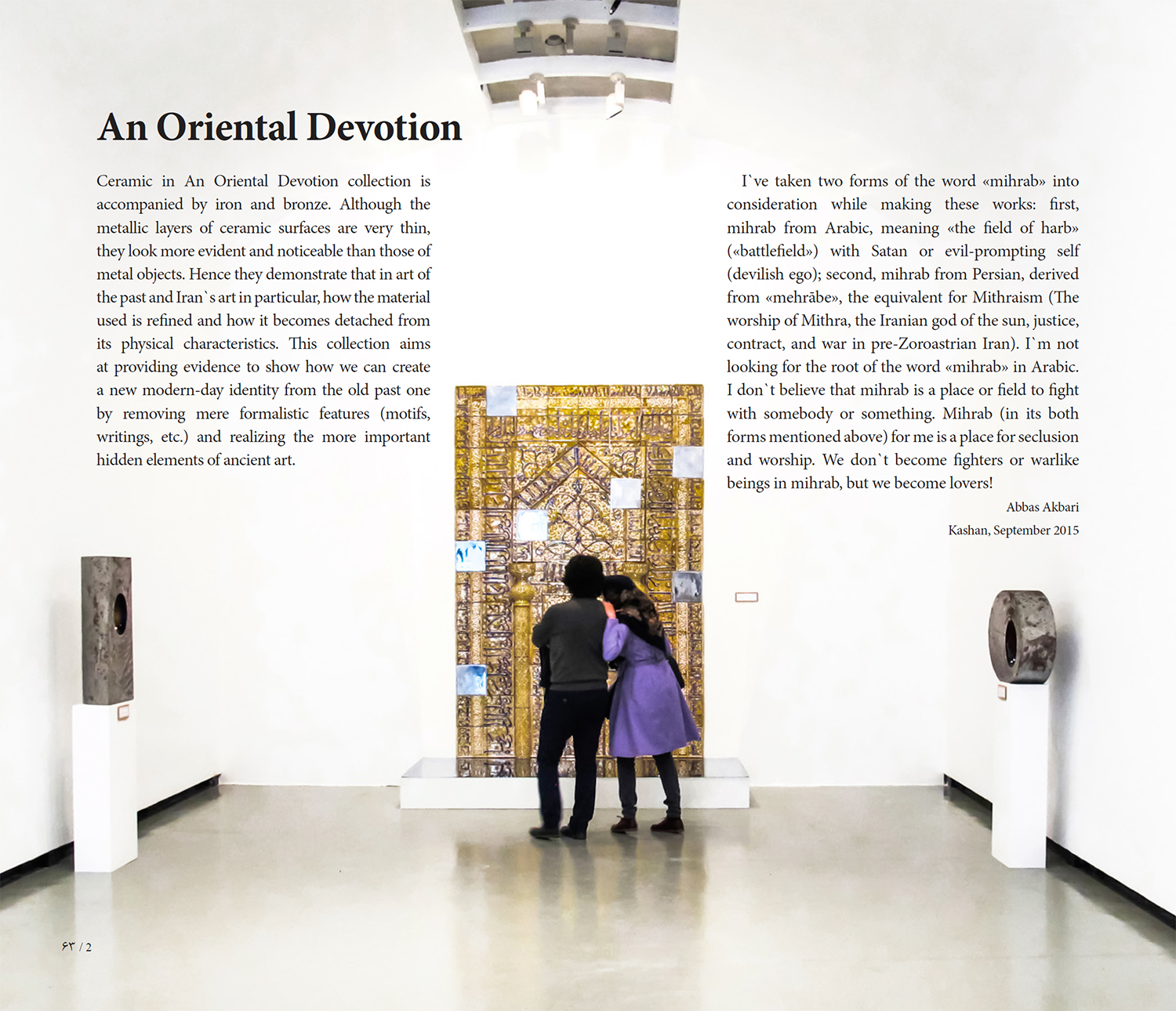

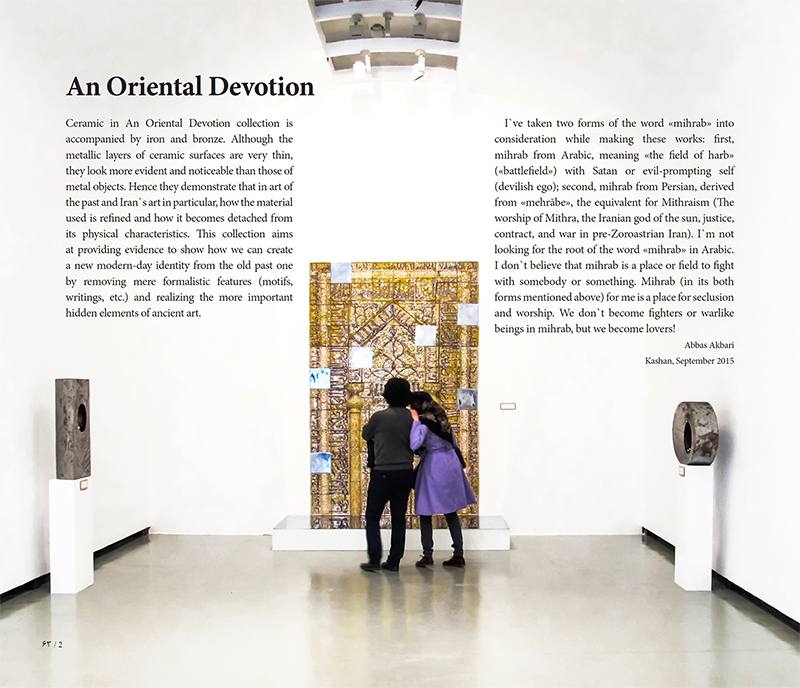

During the 2020s, several artists create resources and performances that increase the visibility of luster mihrabs. In 2021, Kashan-based Iranian potter-art historian Abbas Akbari produces “An Oriental Devotion,” a thirteen-minute film that opens with him walking into Kashan’s Masjed-e Meydan and pausing at the “vacant site of mihrab” in the sanctuary. The film then documents his making of a replica of the mosque’s mihrab—with some major creative interventions, including the use of iron—and installing it in Tehran’s Aun Art Gallery in 2015 (fig. 266).247 While Akbari films his works on view in the gallery, Dr. Ata Omidvar’s recites the azan, adding a resonant spiritual dimension to the film.

In his bilingual artist statement, Akbari reflects on the etymology and symbolic significance of the word mihrab, offering a personal interpretation that departs from conventional readings (fig. 267):

I’ve taken two forms of the word «mihrab» into consideration while making these works: first, mihrab from Arabic, meaning «the field of harb» («battlefield») with Satan or evil-prompting self (devilish ego); second, mihrab from Persian, derived from «mehrābe», the equivalent for Mithraism (The worship of Mithra, the Iranian god of the sun, justice, contract, and war in pre-Zoroastrian Iran). I’m not looking for the root of the word «mihrab» in Arabic. I don’t believe that mihrab is a place or field to fight with somebody or something. Mihrab (in its both forms mentioned above) for me is a place for seclusion and worship. We don’t become fighters or warlike beings in mihrab, but we become lovers!

In “An Oriental Devotion,” Akbari harnesses the medium of film to educate international audiences on Kashan and its ceramic traditions. The film shares a substantive amount of information in a dynamic and tangible way, literally walking viewers through Kashan, the mosque, and Akbari’s process of making luster tiles. This packaging of information is a breath of fresh air compared to art historical scholarship that preferences the printed word, is generally detached, and sometimes shows little concern for the actual making of art or experiencing of space. Perhaps most importantly, the film centers the Masjed-e Meydan in the opening frames, leaving no doubt about its existence or location and offering an important reminder of the resilience of sites long after the thefts of their luster tiles.