From Varamin to Honolulu: The Displacement, Commodification, and Aestheticization of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s Luster Mihrab, 1863–2025

Keelan Overton and Hossein Nakhaei

Contents:

- Introduction

- Chapter One (Displacement): 1863–1912

- Chapter Two (Commodification): 1912–35

- Chapter Three (Aestheticization): 1937–2025

- Conclusion and Bibliography

Chapter One (Displacement): 1863–1912

This chapter explores the mihrab’s documentation in Iran by Qajar officials and European visitors, its transport to Paris in 1900 by Mirza Hasan Khan Ashtiani Mostowfi al-Mamalek, and the related European art market for luster tiles.

Shaʿban 1279/January 1863: Varamin

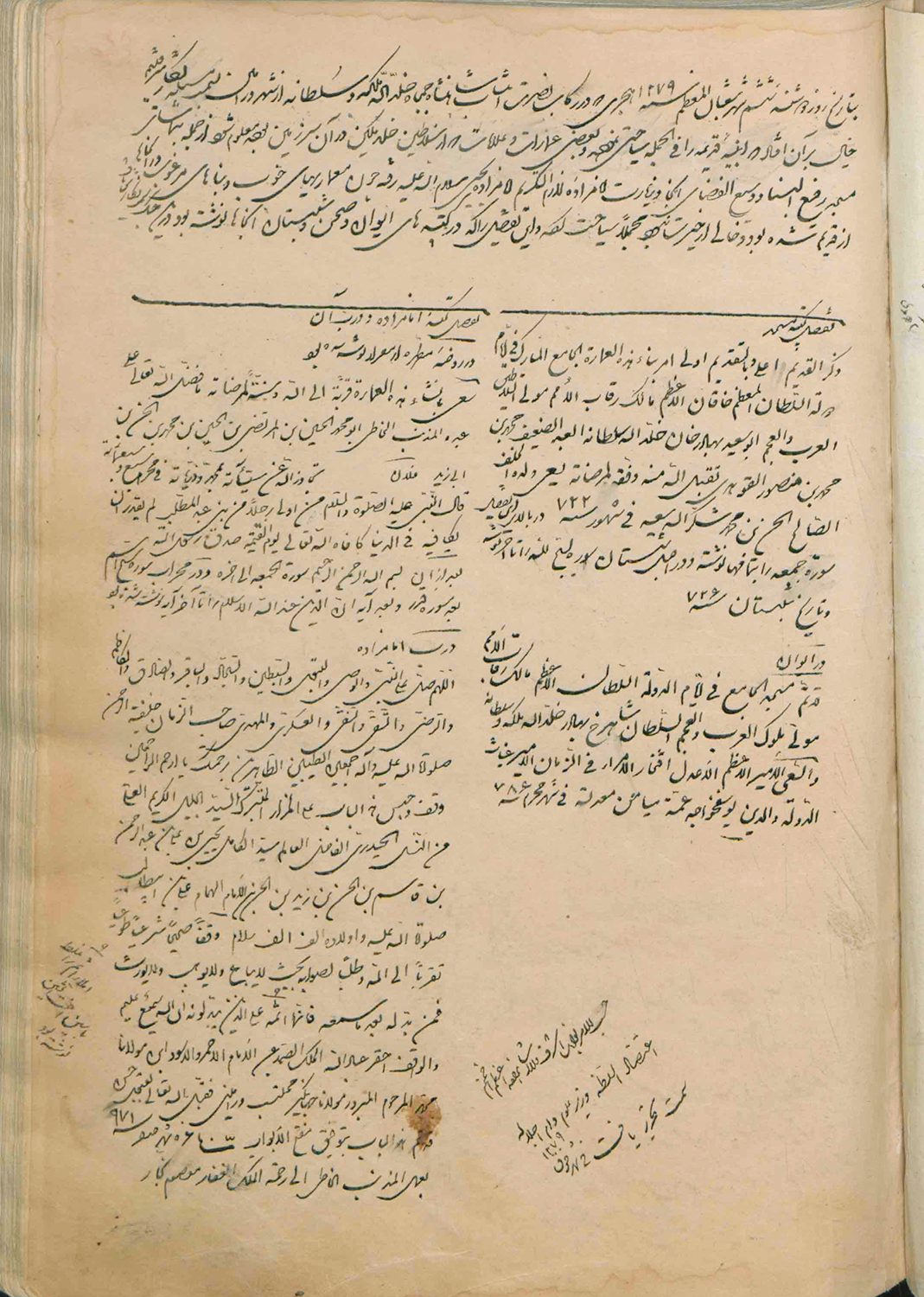

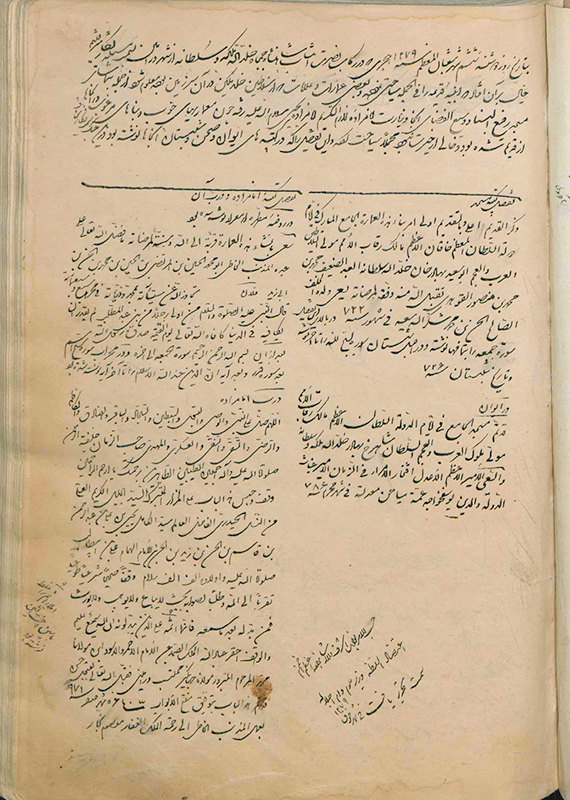

Naser al-Din Shah (r. 1848–96) and members of his court, including Prince ʿAliqoli Mirza Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh (d. 1880), the first minister of science (vazir-e ʿolum), visit Varamin (figs. 7–8). Among the sites mentioned by the shah in his diary (ruznameh-ye khaterat) are Qalʿeh Iraj, an immense fortification about two miles northeast of Varamin and the village’s central citadel (Narin Qalʿeh), the tomb tower of ʿAlaoddin, and the congregational mosque (masjed-e jameʿ) (see Architectural Heritage, nos. 1–2).3 The Emamzadeh Yahya is absent from the shah’s diary, but a series of notes ordered by Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh confirm that some members of the court did indeed visit the shrine. The word used to describe their visit is ‘ziyarat’ (زیارت امامزاده لازم التکریم امامزاده یحیی سلام الله علیه), confirming that the shrine was a living, sacred space and a pilgrimage destination (fig. 9).

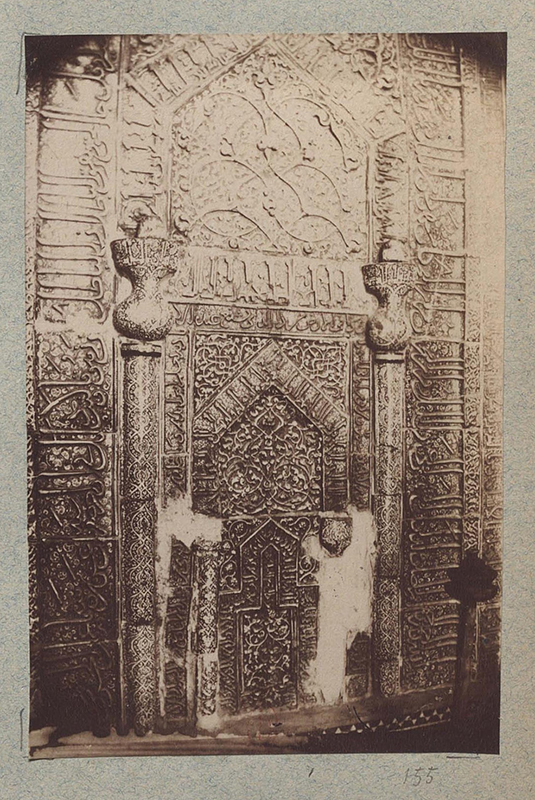

The section on the Emamzadeh Yahya in the field notes focuses on three inscribed architectural elements in the tomb: the stucco inscription wrapping the interior, the luster mihrab on the qibla wall (south), and the wooden entrance door (north). The mihrab section records three sets of large inscriptions: al-Jumuʿah (outermost border), al-Qadr (triangular hood of the inner niche), and al-ʿImran (surrounding the lamp of the inner niche). Many more Qur’anic inscriptions are present on the mihrab but are not recorded, including the lowermost central panel, which contains the date and the name of the potter and might not have been easily visible or accessible (see vid. 2, fig. 5). Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh seems to have been most interested in the saint’s biography and accordingly gravitated toward the tomb’s door, which bore an inscription recording Yahya’s genealogy.

At present, no photographs have been located from this royal visit to Varamin, but the delegation included Aqa Reza (d. 1890), who was soon appointed court photographer (akkasbashi). If photographs were taken at the shrine—and should they come to light—they will be very useful to ongoing scholarship.

1873: Vienna

Persia (now Iran) participates in its first world fair, the Weltausstellung (Universal Exhibition). Architects from Iran are involved in the construction of the pavilion, and Naser al-Din Shah, who is traveling to Europe for the first time, visits the event along with Prince ʿAliqoli Mirza Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh, the minister of science, and Mirza Hossein Khan Moshir al-Dowleh Sepahsalar, the prime minister (d. 1881).4 Examples of Persian natural resources and arts and crafts in different media are displayed in a bazaar-like interior in the Industriepalast (Palace of Industry) alongside goods from China and Romania (fig. 11).5

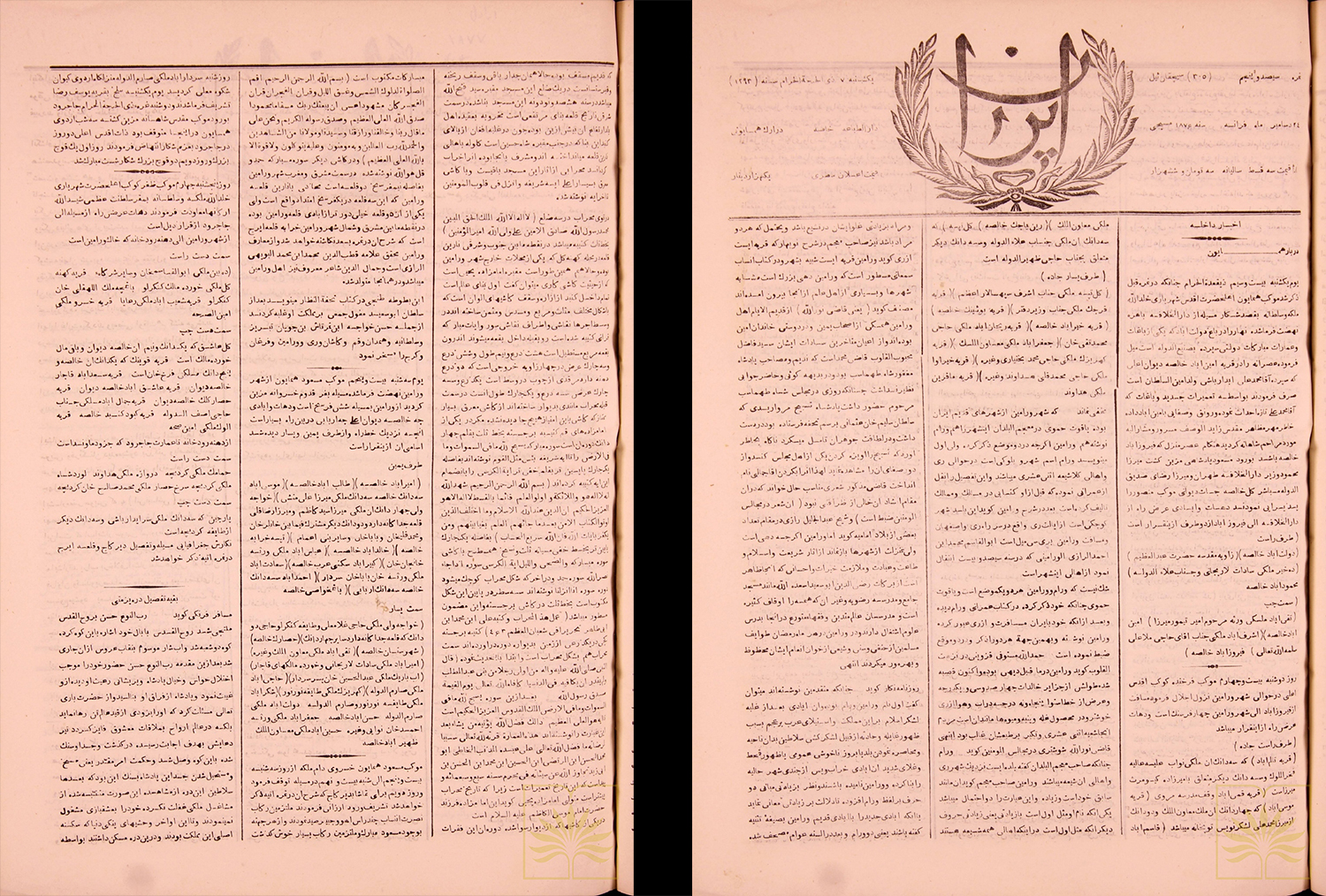

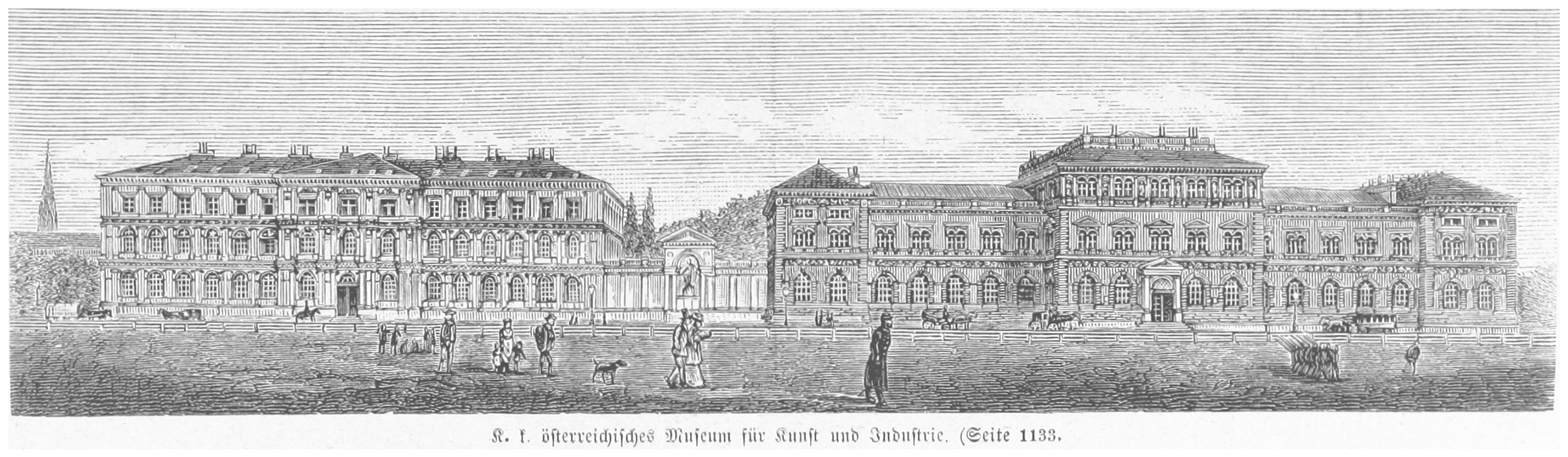

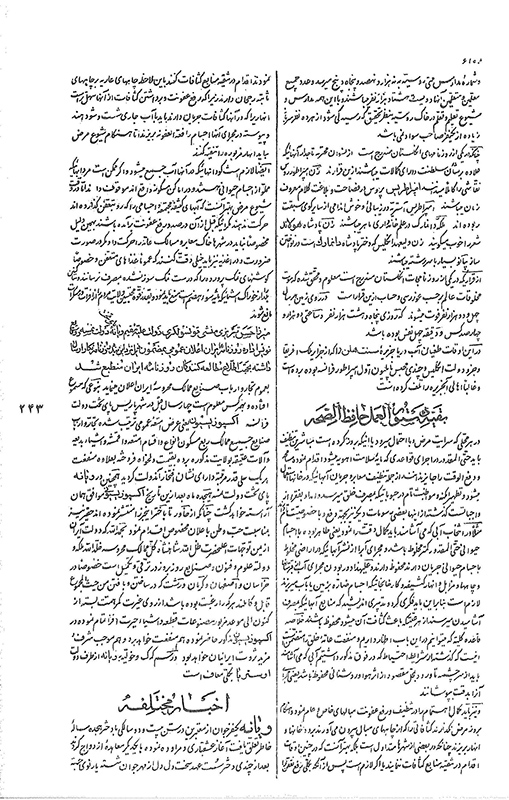

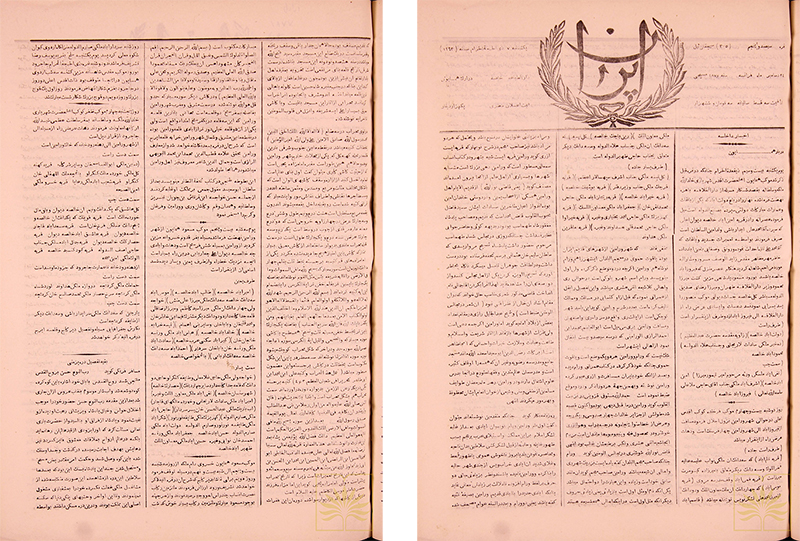

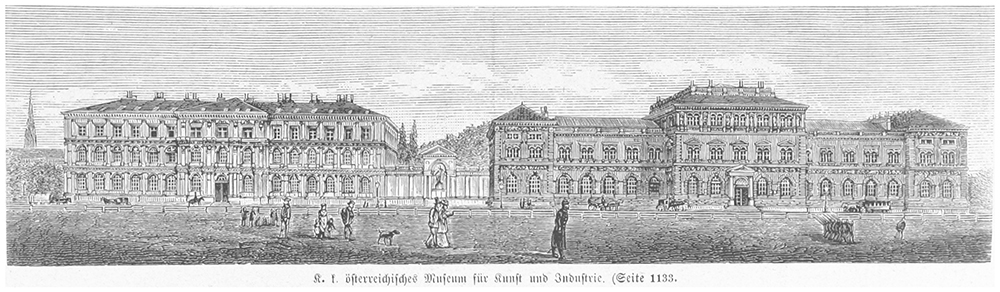

Prior to the event, Mirza Hasan Tabrizi, secretary of the Iranian consulate in Vienna, publishes two announcements in the official newspaper Iran. In the first, published eighteen months before the exhibition, he calls on merchants and craftsmen (تجار و ارباب صنایع) to prepare and bring artifacts, specimens, and wondrous objects (مصنوعات، قطعه و اشیای حیرتافزا), both to secure profit and to contribute to the honor and prosperity of the Iranians (fig. 12).6 One contributor who responds to this call is Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh (see 1863), who sends several manuscripts, including three volumes from the monumental Hamzehnameh created for the Mughal emperor Akbar (r. 1555–1605) (no. 458 in the catalogue). After the exhibition, the k. k. Österreichisches Museum für Kunst und Industrie (The Imperial Royal Austrian Museum of Art and Industry; today’s MAK) purchases sixty-one folios from this work (BI 8770).7

Although the catalog of the Persian section does not list luster tiles, they were likely included in, or at least exchanged around, the exhibition, making this one of the earliest contexts for their public consumption in Europe. It is also possible that they arrived too late to be included in the catalogue, and Naser al-Din Shah himself observes that most of the goods arrived late and some still had not arrived (at the time of his recording).8 MAK records indicate that at least thirteen luster tiles were purchased at the Weltausstellung in 1873 (for example, KE 2095).

April 1875: Vienna

On 16 April, the k. k. Österreichisches Museum für Kunst und Industrie (The Imperial Royal Austrian Museum of Art and Industry; today’s MAK) acquires a broken tile from the inner border of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab, which is still in situ in the tomb (fig. 13). The tile is part of an acquisition of twenty-nine tiles from “Fürst Urussoff” (Prince Urussoff), and the group also includes six luster tiles attributed to the dado of the tomb of Emamzadeh Yahya (five stars and one cross; KE 3570-13-18). The acquisition is funded by the Ministry for Trade (Handelsministerium), which suggests that the tiles be displayed as models (of design) and stipulates that they remain in the museum as property of the Ministry for Trade. The “Fürst Urussoff” in question might be Prince Vladimir Pavlovich Urusov (d. 1880), a Russian diplomat who served in Vienna as first secretary between at least June 1874 and January 1876. It is possible that he obtained the tiles during his diplomatic mission in Tehran prior to his transfer to Vienna.9

This case study confirms that individual tiles were removed from the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab while it was still in situ and decades before the majority of its tiles were taken to Paris in 1900. Much of this inner border was ultimately displaced from the mihrab (see vid. 2 and fig. 5).

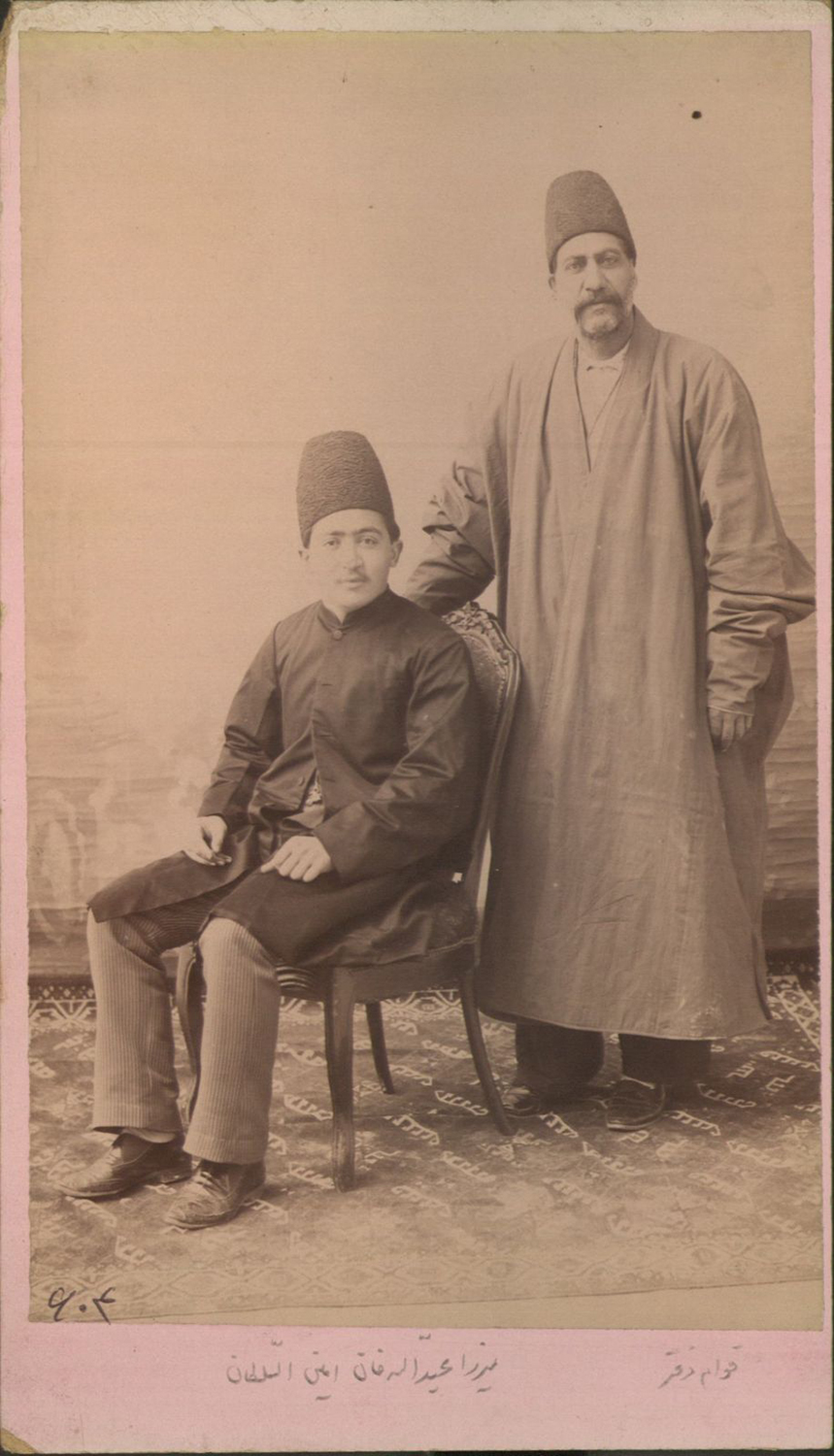

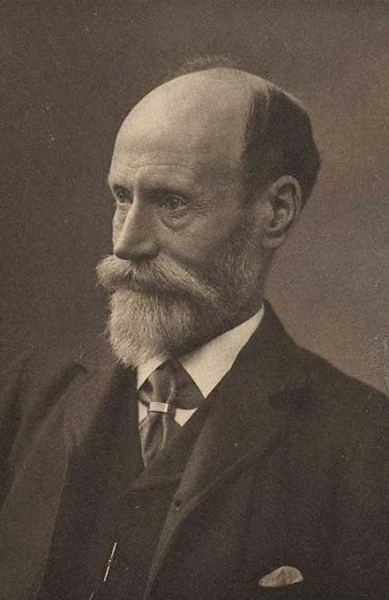

1875–76: Tehran

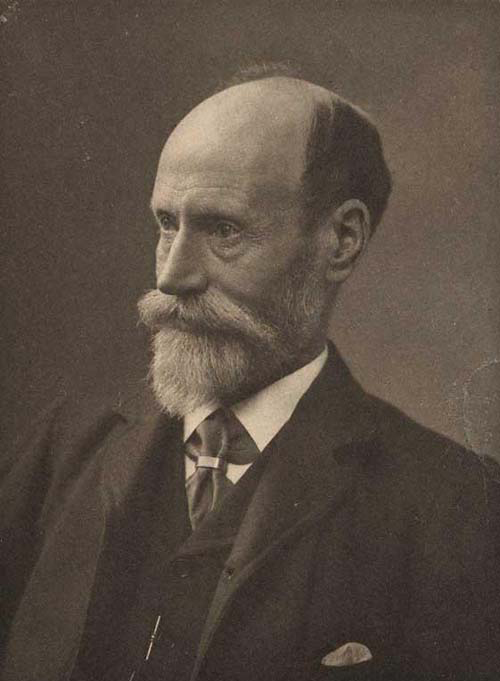

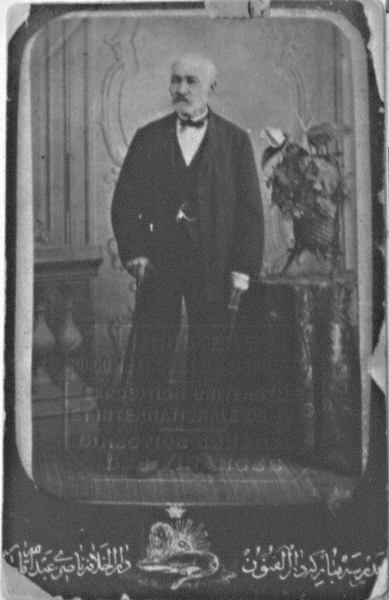

Major Robert Murdoch Smith (d. 1900), the director of the Persian Telegraph Company and a buying agent for the South Kensington Museum in London (later the Victoria and Albert Museum, or V&A), has a major break in his acquisitions for the museum (fig. 14).10 In January 1875, he meets Jules Richard (d. 1891), a Frenchman who had lived in Iran since 1844 and shifted among the roles of translator, collector, dealer, photographer, and professor at the Dar al-Fonun (Abode of Science, established 1852) (fig. 15).11 In his report no. 9 to the museum’s director Sir Francis Philip Cunliffe-Owen (d. 1894), Murdoch Smith describes seeing Richard’s collection:

I have recently examined in a cursory manner a very valuable collection of Persian articles belong to M. Richard, a French Mussulman who has been resident in Teheran. The collection comprises articles of about every class, and has been formed gradually in the course of nearly 30 years. Most of the objects are packed away in boxes but I am now getting them unpacked and a catalogue made. I have induced M. Richard to agree to my proposal to fix a price for each article, and at such prices to give the Museum the refusal of the whole or any portion of the collection. I propose to begin with the China & Fayence (vid. 3).

A few weeks later, Murdoch Smith sends the museum the catalogue of 296 pieces of “China” and 374 examples of “Persian Fayence.”12 By April, he is authorized to purchase the whole of Richard’s catalogued collection, over two thousand pieces, and the two men begin packing the boxes.13

Video 3. Turning the pages of Robert Murdoch Smith’s description of his first examination of Jules Richard’s collection in Tehran in January 1875. Report no. 9 from Robert Murdoch Smith, Telegraph Department of Persia, Teheran, to the Director (Sir Francis Philip Cunliffe-Owen), South Kensington Museum, London, 20 January 1875, 1–3. V&A Archive, MA/1/S2325. Video by Keelan Overton, 2024.

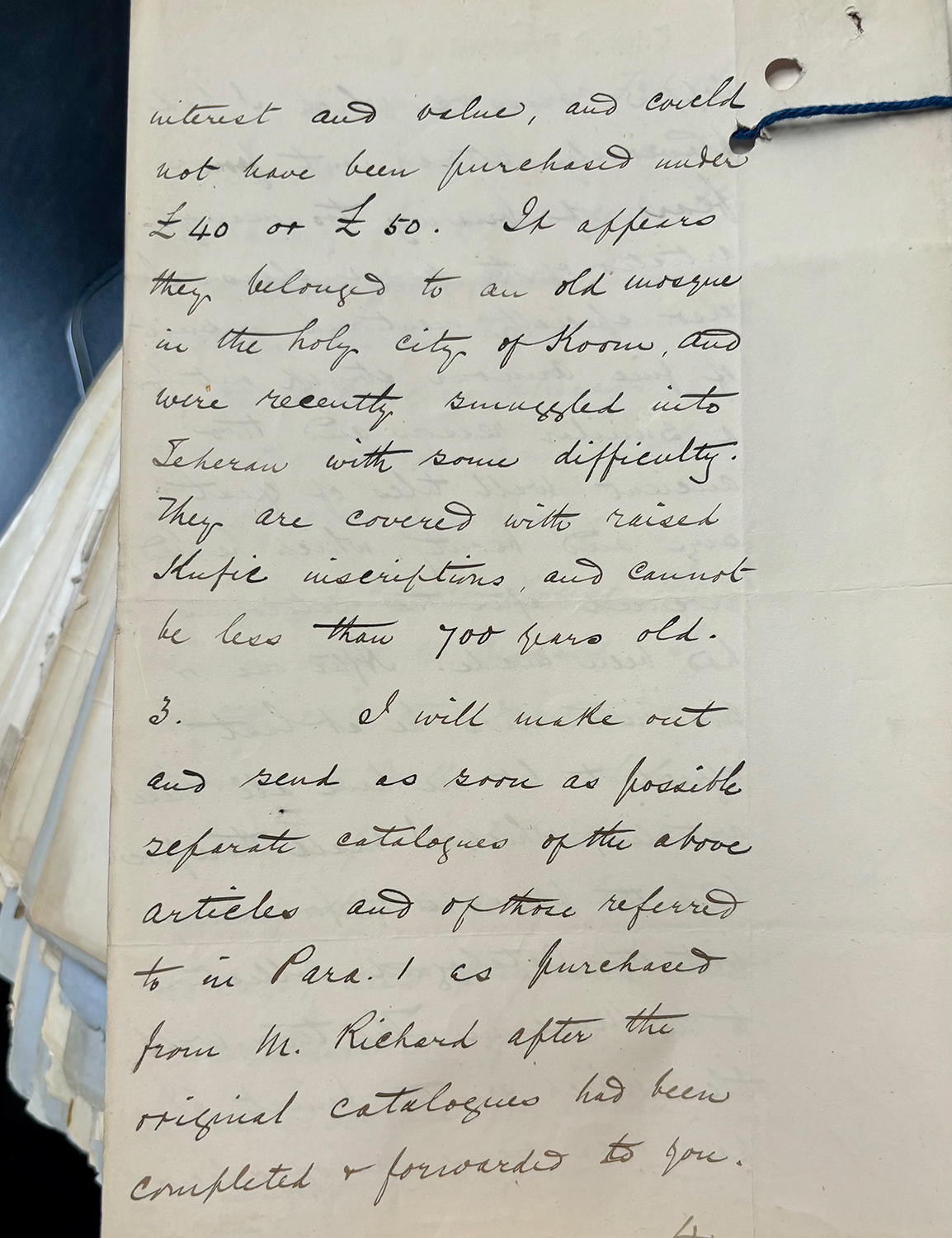

This first acquisition includes many luster star and cross tiles that can be attributed to the Emamzadeh Yahya, which Murdoch Smith simply describes as “from Verameen” (see Fuchsia Hart’s discussion in Handling Session). He is also exposed to luster tiles with problematic histories:

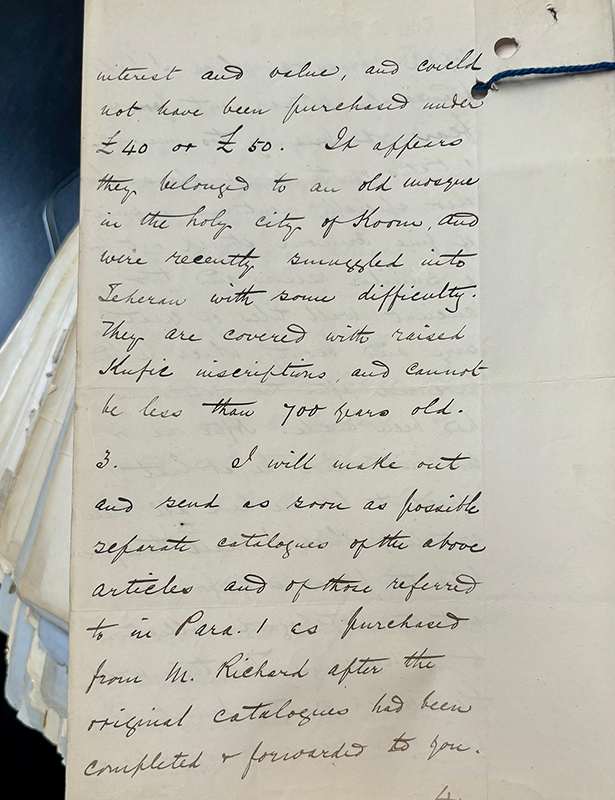

The two wall tiles, which are the finest I have ever seen, are of special interest and value, and could not have been purchased under £40 or £50. It appears they belonged to an old mosque in the holy city of Koom [Qom], and were recently smuggled into Teheran with some difficulty (fig. 16).

In report no. 16, Murdoch Smith describes how news of Richard’s sale to South Kensington seems to have spread throughout Tehran and encouraged other collectors, including Qajar officials and Europeans, to offer their possessions for sale. Murdoch Smith recommends that the museum take advantage of these circumstances and notes that the “Chancelier of the French Legation [Louis Jean-Baptiste Comte de Nicolas, d. 1875] has some very fine ancient wall tiles, which he might probably be induced to part with at a fair profit.”14 In his next report (no. 17), Murdoch Smith describes Nicolas’s tiles as very rare and increasingly hard to acquire, since most are found in mosques.15 Iranian “mollahs” had noticed the disappearance of such tiles, and Murdoch Smith anticipates that the government will take measures to protect religious sites (for a reproduction of this section of the report, see Luster Cabinet, fig. 2).

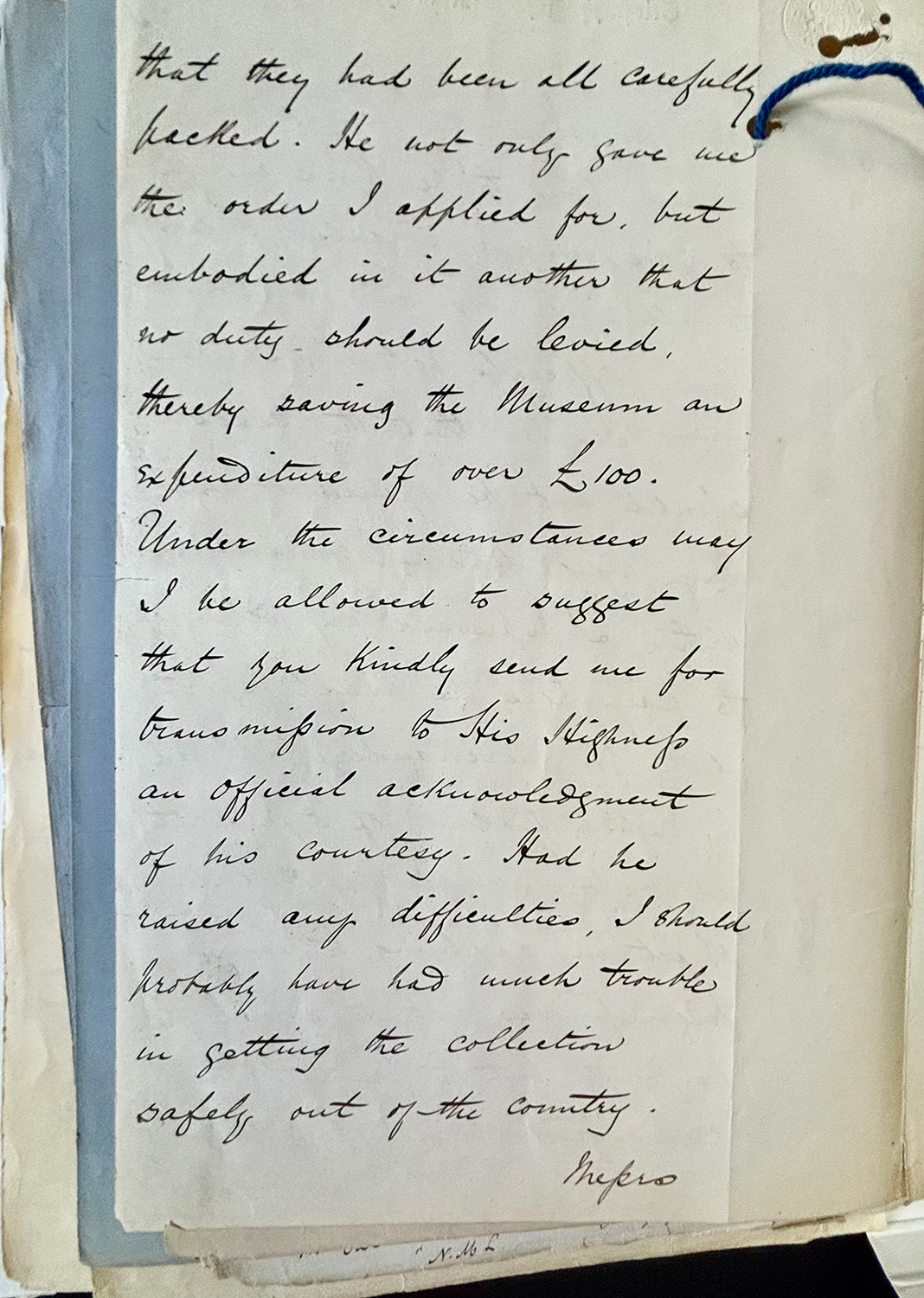

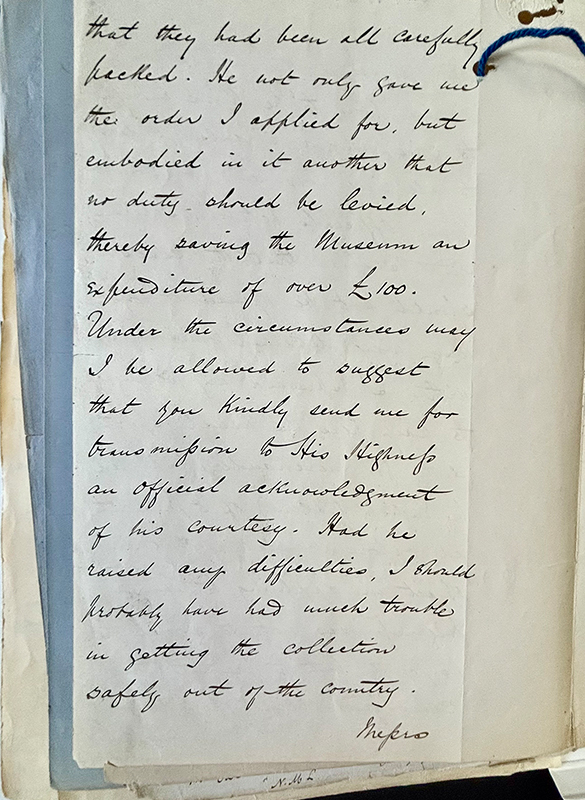

In early August (report no. 19), Murdoch Smith reports that the materials purchased from Richard and Nicolas have been packed into sixty-two cases and that he had asked “His Highness the Sipeh Salar Azem (Prime Minister)” (Mirza Hossein Khan Moshir al-Dowleh Sepahsalar, d. 1881) to order all governors and custom house officials along the long route from Tehran to Bushehr (map) not to open, detain, or interfere with the carefully packed cases (fig. 17). Sepahsalar not only issues this order but also waives the export duty (levy), saving the museum about £100. Murdoch Smith requests that the museum acknowledge this “courtesy,” because if Sepahsalar had caused any problems, the agent would have had trouble taking the crates safely out of the country (fig. 18). Four months later, Murdoch Smith repeats this reality and request:

Without such an order I hardly know how I could have got the semi-sacred contents of the cases out of the country in safety. May I therefore be allowed to suggest that another letter of thanks be forwarded to his Highness for his courtesy?16

On 1 September (report no. 22), Murdoch Smith explains why it will be difficult to obtain images of the tiles “taken” from “mosques:”

I fear it will be impossible to carry out your wish to get drawings of the mosques from which the ancient tiles were taken. The buildings in question are scattered over a great extent of [the] country almost without means of communication with Teheran. The mosques themselves being moreover absolutely closed to Europeans.17

In November (report no. 24), Smith writes that he has “lately purchased for £50 three very large tiles forming the complete tombstone of an Imām Zādeh, Hussein, the great grandson of Ali the son-in-law of Mohamed.”18 He describes them as “in a state of perfect preservation” and “very beautiful specimens” of luster and underscores that their age is authenticated by the inscribed genealogy of the saint. He then turns to their acquisition:

“It will be readily understood that such an object as this monument could not be easily or openly obtained. It was, I understand, removed from the shrine to which it belonged some years ago and hidden underground until an opportunity of smuggling it into Teheran could be found. Its presence here is quite unknown except to Mr. Richard, who got it for me, and to one or two Persians in his confidence.”19

Further down in the same report, Murdoch Smith refers to the large tile mentioned in report no. 15 (see fig. 16), which was also on its way to London and part of a tombstone set, specifically, the upper tile. On the other two tiles in the set, he writes: “Mr. Richard has lately been told that the two others which were wanting to complete the monument are hidden elsewhere near Tehran, and are only waiting a favourable chance of being brought into the town.”20 Murdoch Smith admits that early on he had not been too hopeful about obtaining any tiles “of great value” but that Richard had “considerably diminished” various difficulties, thanks to his “intimate relations with many of the mollahs,” which the agent attributes to his Persian name (Mirza Reza) and his being Muslim.21

Richard’s ability to move among identities—as a collector-dealer, Muslim convert, and Dar al-Fonun professor—highlights how European actors embedded themselves in Qajar institutional life to facilitate the acquisition of cultural materials. Murdoch Smith’s careful language and repeated emphasis on the obstacles involved in acquiring luster tiles from sacred sites reveal his awareness of risk and sensitivity. His clarification to the museum that religious buildings were “absolutely closed to Europeans” and his insistence that some “hidden” tiles could only surface under favorable circumstances reveal his underlying anxiety about the violating and precarious nature of such acquisitions.

In April 1876, many of the over two thousand ‘articles’ Murdoch Smith acquired in Iran are displayed in South Kensington’s new Persian Court, located in the North Cloister of the museum (see this plan). The galleries are heralded in the press as “a very important addition to the museum,” and Murdoch Smith is praised for assembling a collection “illustrating every section of Persian art and art industry, ancient and modern, and, as a whole, unrivaled in Europe.”22 Two small books are published, including Smith’s Persian Art (see 6:20 in this film), which likewise credits the buying agent as well as his main source:

The large portion of [the Persian collection] has been obtained by the assistance of Major M. Smith [Murdoch Smith]; who was fortunate also in securing for the museum a collection which had been formed by a French gentleman long resident in Persia, M. Richard [Jules Richard].23

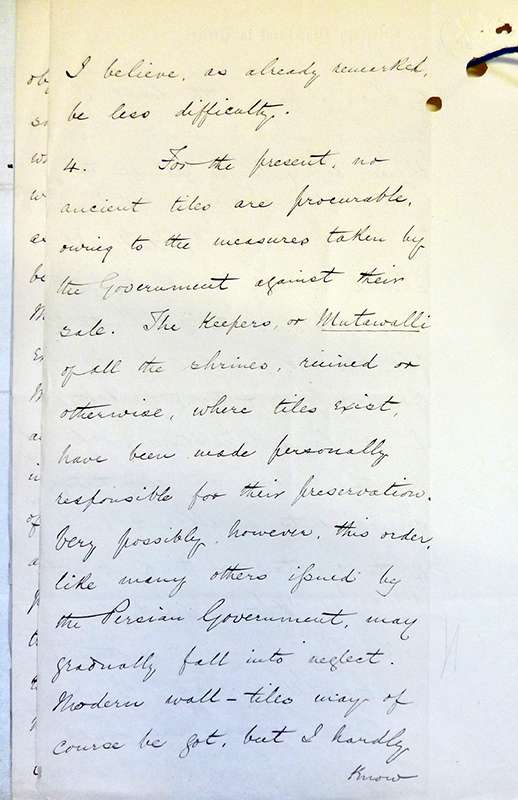

By September 1876, Murdoch Smith’s earlier premonition (June 1875) that the government would take steps to protect religious sites is realized. He reports:

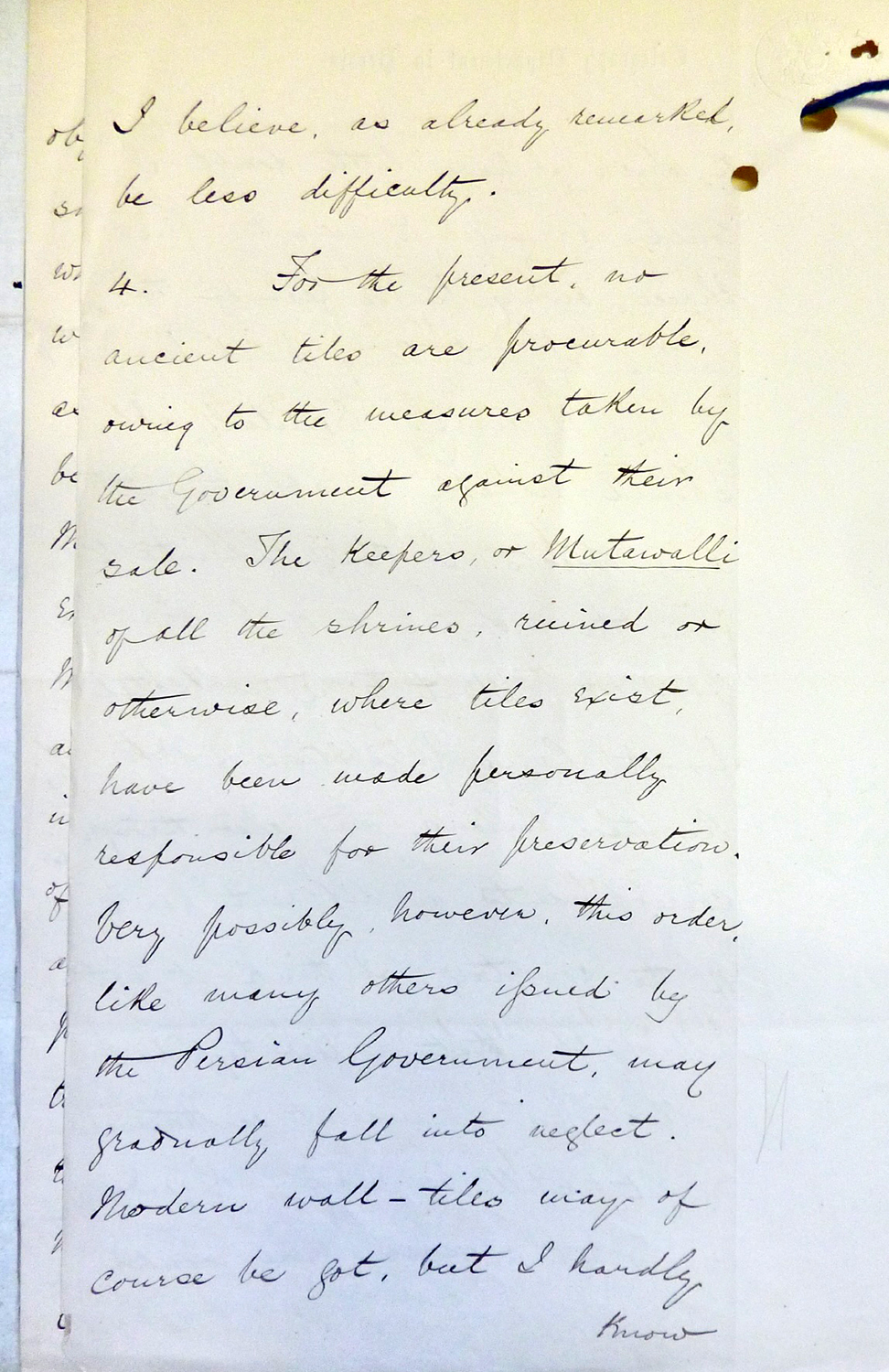

No more ancient tiles are procurable, owing to the measures taken by the Government against their sale. The keepers or Mutawalli [motavvali] of all the shrines, ruined or otherwise, where tiles exist, have been made personally responsible for their preservation (fig. 19).

Smith predicts that this “order” may “fall into neglect” and that “modern wall-tiles” may be available.24

The partnerships and sales among the South Kensington Museum, agent Murdoch Smith, collectors Richard and Nicolas, and Iranian officials like Sepahsalar marked a seminal moment in the history and historiography of Persian luster tilework. Large quantities of luster tiles were exported from Iran, and some were known by key actors in this network to belong to sacred buildings and to have been smuggled into Tehran. The most sacred feature of any tomb—the three-dimensional cenotaph—was particularly at risk of physical dismantling and conceptual isolation, and tombstone panels embedded into the upper surface of the cenotaph and often naming the deceased were isolated from the whole and marketed to museums as ostensibly complete ‘monuments.’ Soon after arriving in London, luster tiles were quickly displayed in the Persian Court, where, as Moya Carey has noted, they undoubtedly fueled further demand.25 The South Kensington display was a significant moment in British museology and set a precedent for arranging tiles from sacred sites alongside unrelated manuscripts, textiles, and ceramics, transforming devotional and architectural fragments into aesthetic specimens of “Persian art.”

Dhu al-Qaʾdah 1293/December 1876: Varamin

A second Qajar official, the historian-geographer-statesman Mohammad Hasan Khan Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh (d. 1896), visits the Emamzadeh Yahya and many other monuments in Varamin (fig. 20). Just twelve days after leaving the village, he publishes his detailed account in the newspaper Iran (fig. 21).

Unlike Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh in 1863, Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh carefully records most of the mihrab’s Qur’anic inscriptions. He also reads the panel at the bottom of the mihrab (see vid. 2), describing it as three lines (actually two) of sols (thuluth). He correctly records the signature of the potter but incorrectly reads the date as Shaʿban 463/۴۶۳ (the month is correct; the year is actually 663/۶۶۳) (fig. 12). Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh emphasizes the uniqueness of the tiles by noting that a comparable example “has never been seen except for in an emamzadeh in Qom” (هیچ جا دیده نشده مگر در یکی از امامزادههای قم).26 He may have been referring to the Emamzadeh ʿAli b. Jaʿfar, which also included a luster mihrab, and to which we will soon return (jump ahead to 1931).

Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh also reads the Qur’anic inscriptions on two star tiles that had become separated from the wall (از دیوار سوا شده), likely referring to luster stars interlocked with crosses in the dado.27 Their detachment from the wall makes sense, given that they were already being collected and purveyed in Tehran. Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh is conspicuously silent about these removals, raising questions about his indifference to, if not deliberate avoidance of, the ongoing thefts at the site. As the Chief of the Printing and Translation Bureau, he would have understood the reach and impact of his article. As a prominent official in the Qajar court, he was probably also aware of the ulama’s concerns about religious sites and the related government order in place by September 1876 (see fig. 19).

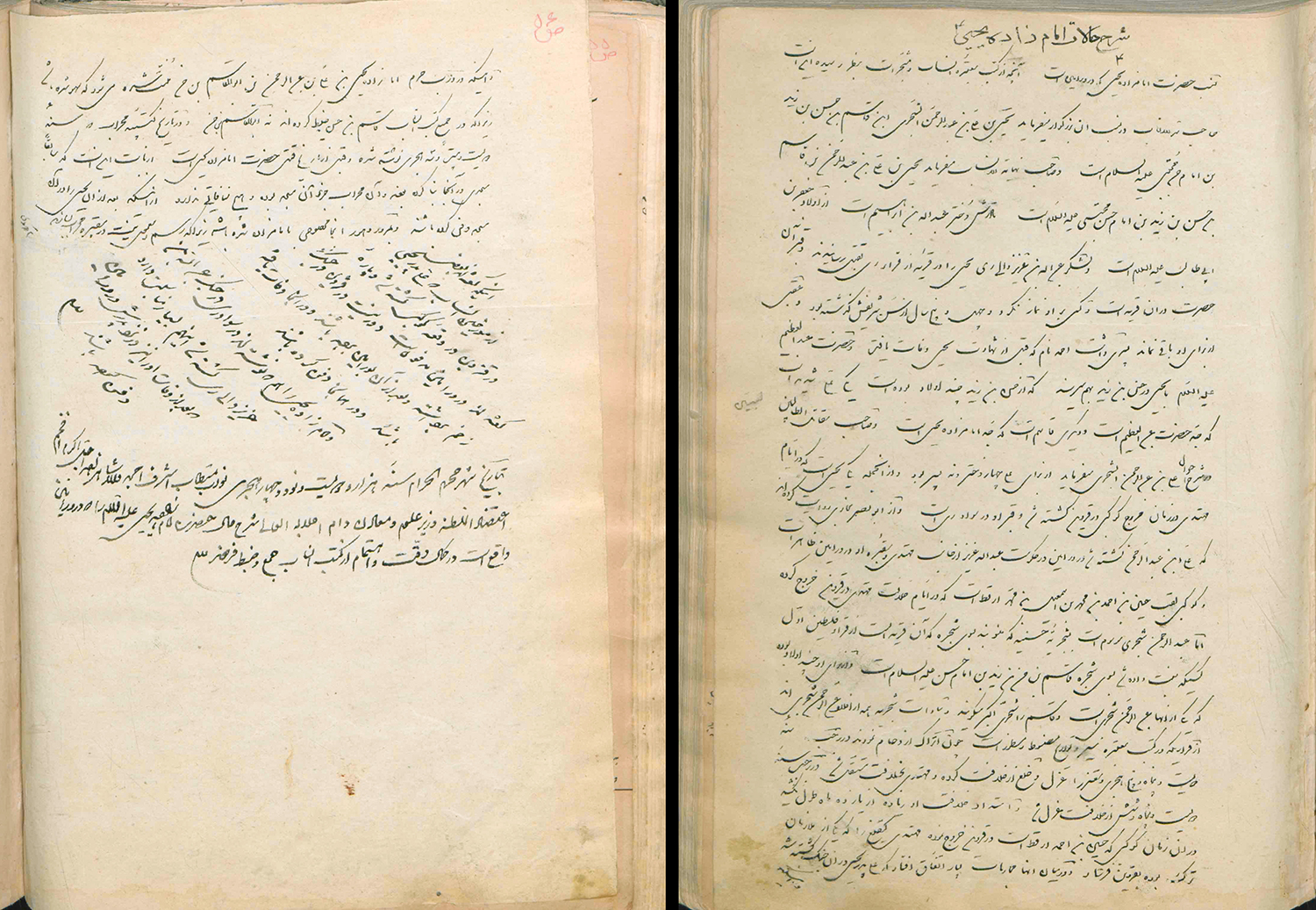

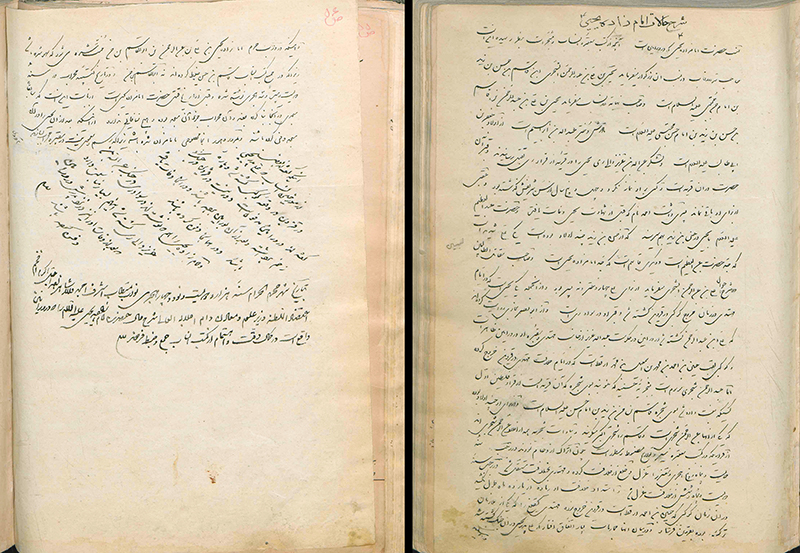

Moharram 1294/January 1877: Tehran

Just a month after Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh’s article is published in the newspaper Iran (see 1863), Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh compiles a two-page biography (sharh-e halat) of Yahya b. ʿAli (fig. 22).28 This biography includes some important comments on the mihrab. Once again, it is incorrectly dated, in this instance to 223/۲۲۳, four hundred years earlier than its actual date of 663/۶۶۳. The reader of the inscription might have confused the digit ۶ (6) for ۲ (2), or it could have been difficult to see the panel at the bottom of the ensemble due to poor lighting or obstruction. This perceived date of 223/837–38 predates Yahya b. ʿAli’s assassination of 255–56/869–70 by decades and prompts some hypotheses, including that the site was previously a mosque and only developed into an emamzadeh after Yahya’s burial. Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh justifies this reasoning by stating that mihrabs are uncommon in tombs, a surprisingly inaccurate statement.29

Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh’s focus on Yahya b. ʿAli himself presents an important contrast to contemporary European visitors, most of whom focus on the shrine’s luster tilework, some of which was already being taken and sold in Tehran (see 1875–76).

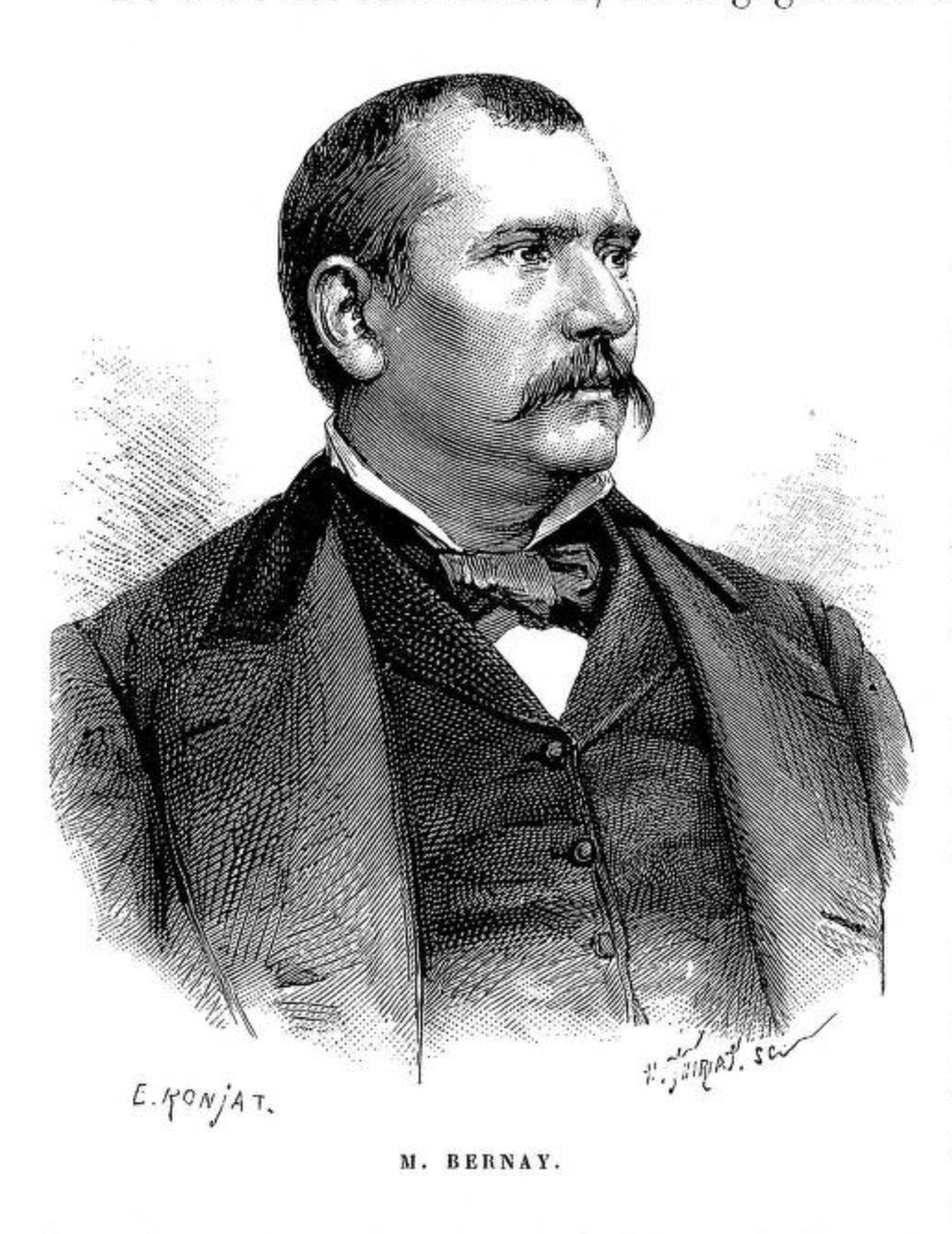

1878–80: Sèvres

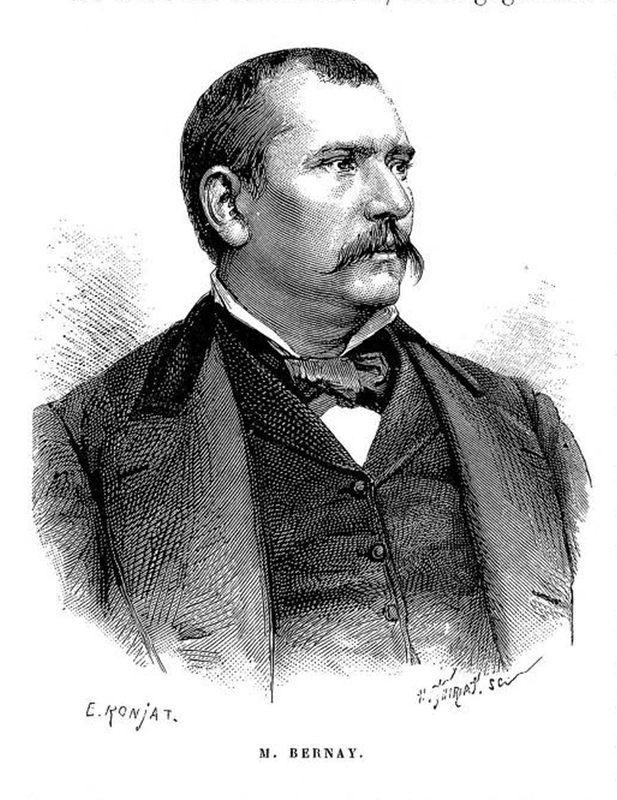

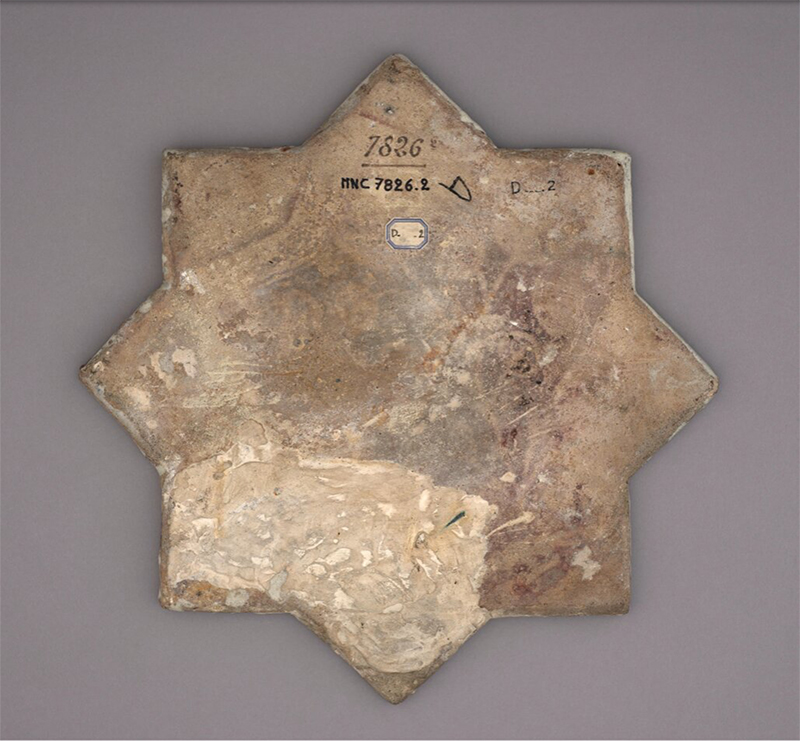

In May 1878, French diplomat Émile-Charles-Henri Bernay (d. 1908) sends a batch of seven star and cross tiles that can be attributed to the Emamzadeh Yahya to the National Museum of Ceramics in Sèvres (figs. 23–24). The tiles are assigned the number 7826, and a March 1880 note ascribed to Bernay in the museum’s inventory book records their provenance:

De l’intérieur de la mosquée de Véramine (ville fort ancienne à proximité de Ragès). Le tour est orné de caractères persans. Ce genre de plaques devient fort rare; il n’y a en Perse que quatre mosquées ayant à l’intérieur de ces plaques de revêtement. Un seul de ces monuments reste debout et à peu près intact; les autres sont en ruines; les plaques qui les ornaient ont été enlevées ou brisées. Ces mosquées datent d’un peu après l’invasion de la Perse par les arabes.30

From the interior of the mosque at Varamin (a very old city near Rey). The border is decorated with Persian characters [Arabic, from the Qur’an]. This type of tilework is becoming very rare; there are only four mosques in Persia that have such tilework inside. Only one of these monuments remains standing and more or less intact; the others are in ruins. The tiles that adorned them have been removed or broken. These mosques date from shortly after the Arab invasion of Persia.

Bernay’s work for Sèvres can be compared to Murdoch Smith’s role for South Kensington (see 1875–76). Both were based in Iran for other occupations (diplomacy for the French Legation and engineering and administration for the Persian Telegraph, respectively) and were then hired by museums to research ceramic technologies and acquire materials.31 Both also emphasized the rarity of luster tiles and described those likely from the Emamzadeh Yahya in generic terms as ‘from Varamin’ or ‘from a mosque in Varamin.’ The steady arrival of these tiles in France and Britain likely motivated subsequent European travelers to seek them out during their travels in Iran.

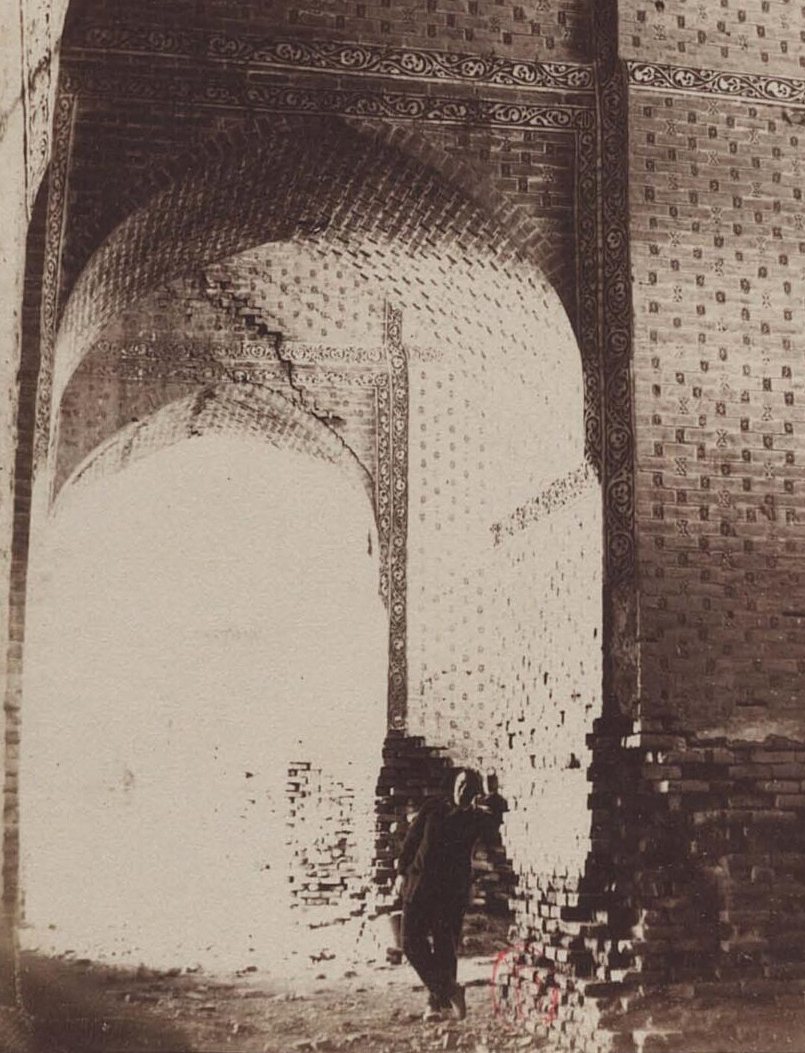

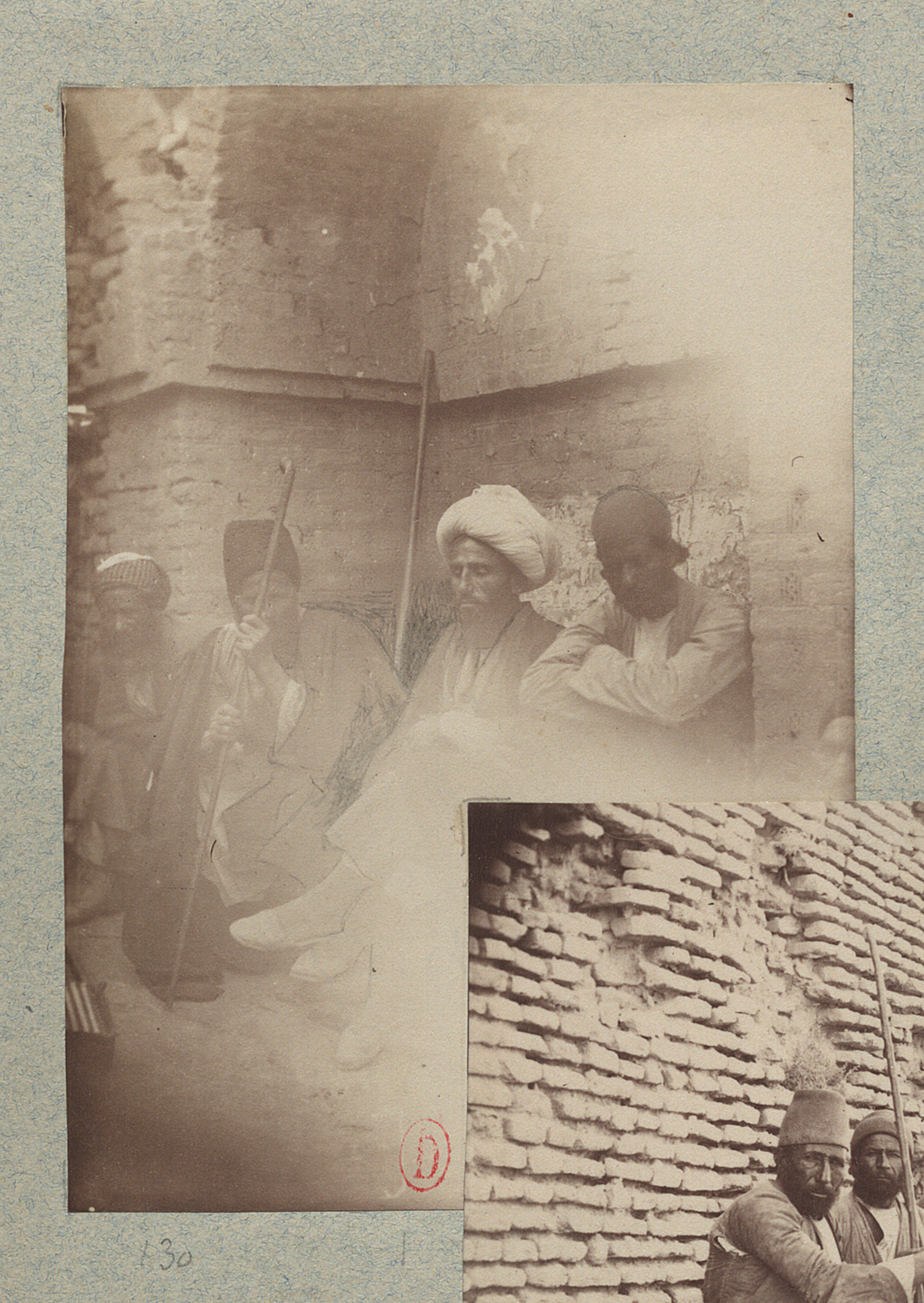

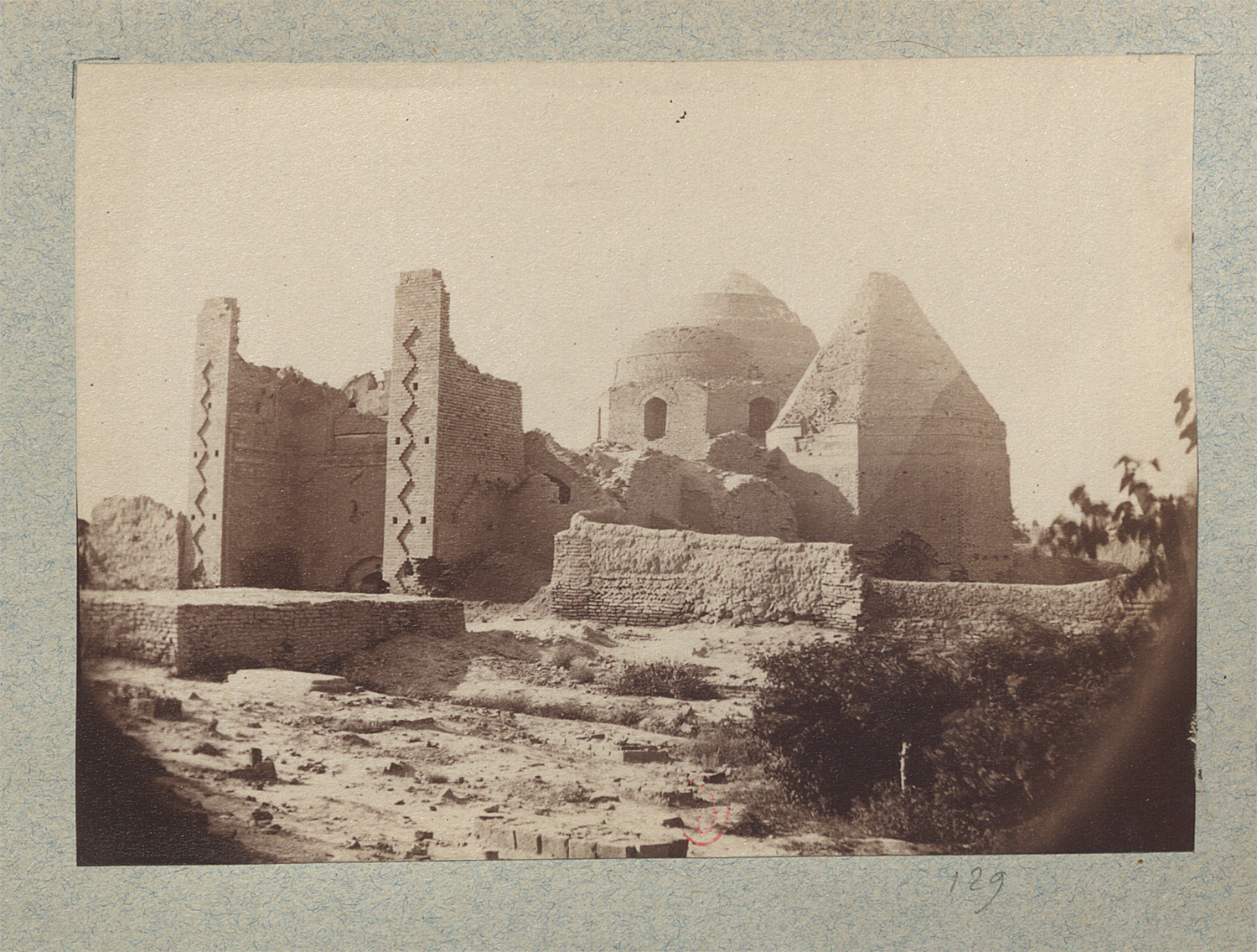

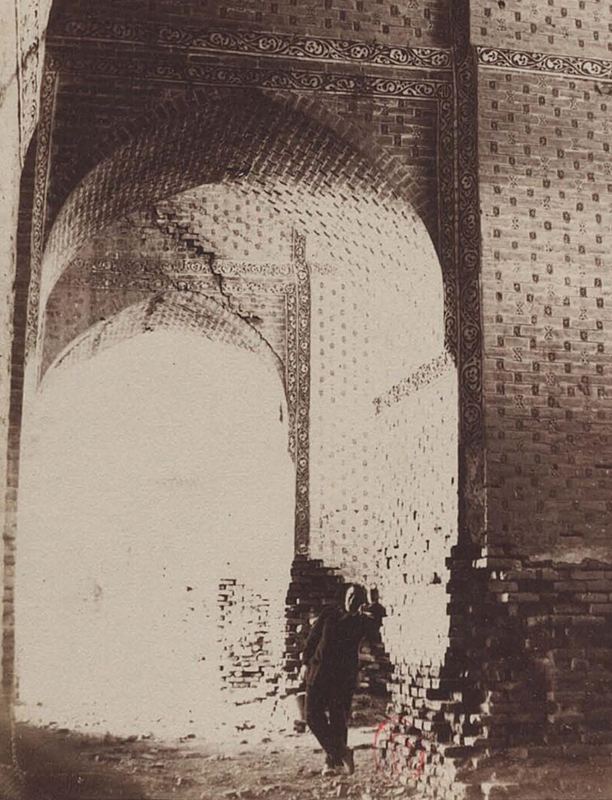

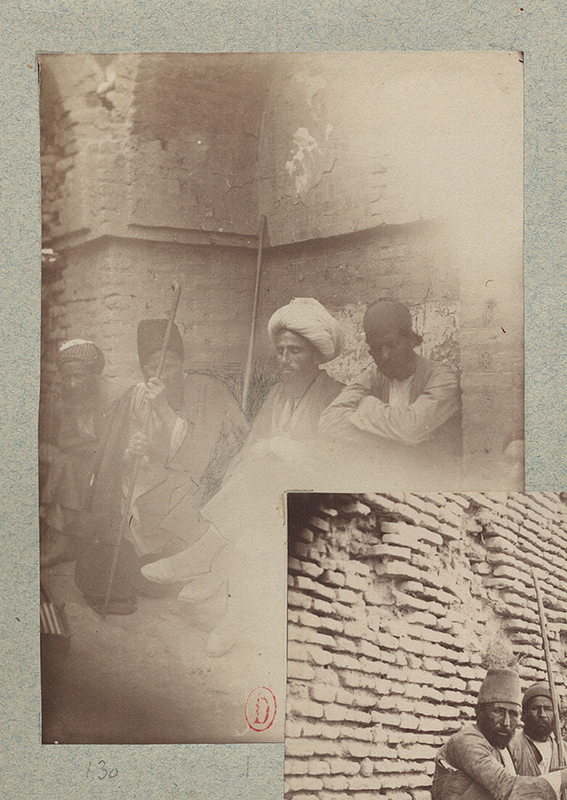

1881: Varamin and Kashan

French traveler and budding amateur photographer Jane Dieulafoy (d. 1916) visits Varamin during a year-long tour of Iran with her archaeologist husband Marcel (d. 1920) (fig. 25). The couple carries a letter from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs but are not part of an official expedition.32 On 7 June, they have a brief audience with Naser al-Din Shah in Tehran, and Jane photographs some children from his family. Upon arriving at the Emamzadeh Yahya eleven days later, the Dieulafoys are confronted by a “mollah” and “paysans armés de batons” (peasants armed with sticks), as described in her subsequent newspaper article (jump ahead to 1883).33 She photographs this group, describes their presence as a response to the recent “vols” (thefts) of the shrine’s tiles, and mentions a “loi commune” (common law) prohibiting Christians from entering such religious sanctuaries, which was perhaps tied to the government order described by Murdoch Smith in 1876 (fig. 26; see fig. 19). With the assistance of an order issued by Naser al-Din Shah, the couple enters the shrine, meaning that the shah’s permit seems to have overridden the site’s local protections.

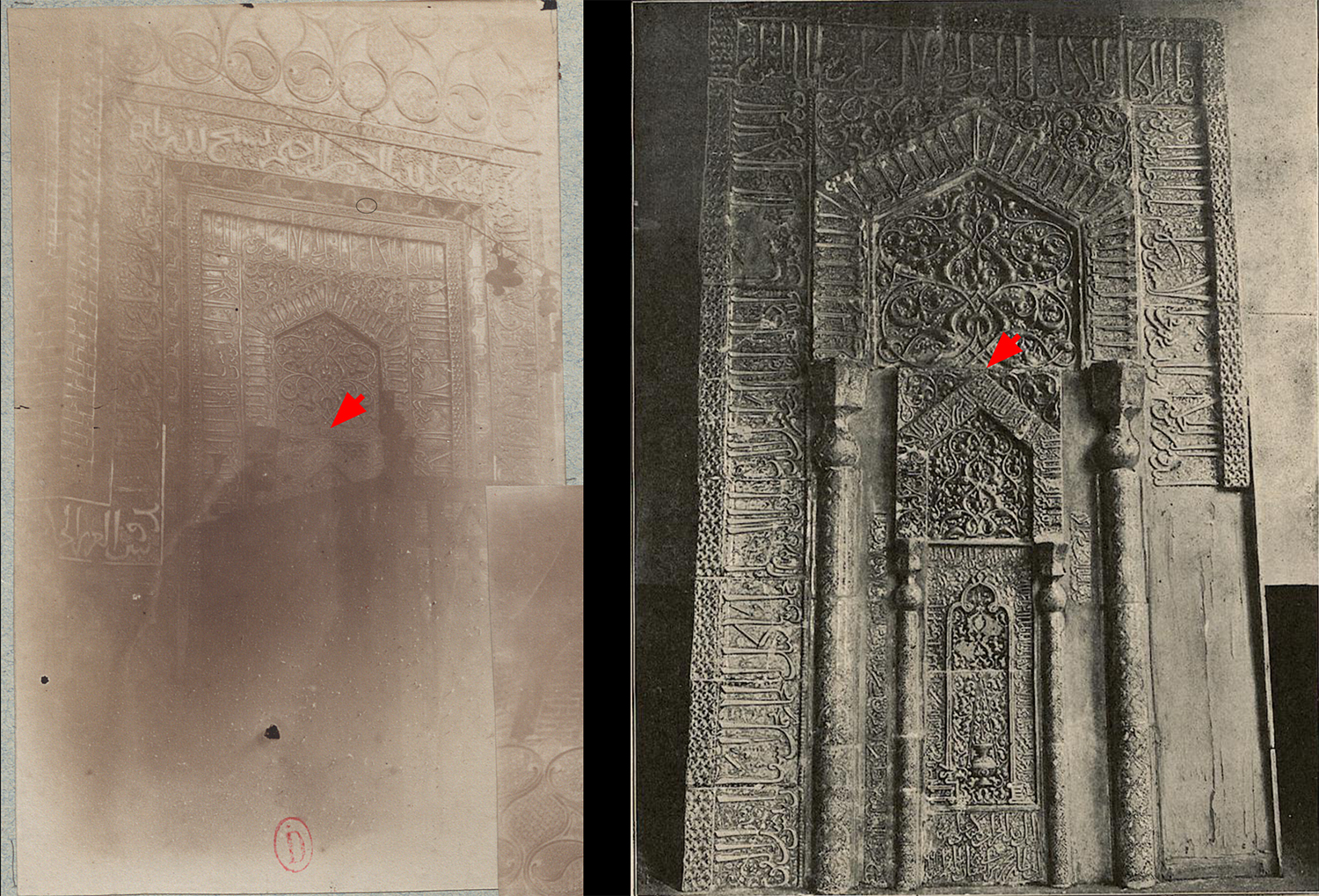

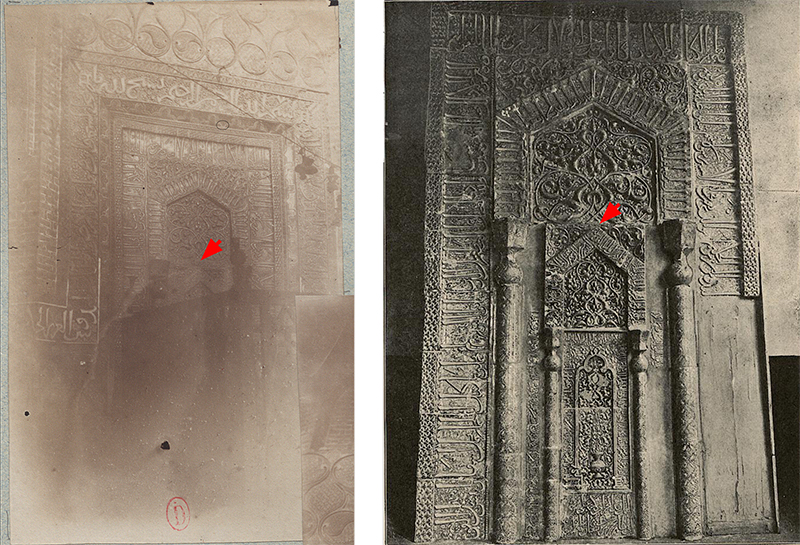

During her visit to the Emamzadeh Yahya, Dieulafoy takes four photographs, including a general view of the complex, which remained in its Ilkhanid-period configuration, and the only known image of the tomb’s luster mihrab in situ (figs. 27–28). The latter photograph is an invaluable record on four levels. First, it clarifies the mihrab’s relationship to surrounding architectural elements on the qebleh (qibla) wall. It was not only framed by the surviving stucco inscription dated Moharram 707/July 1307 (forty-two years after the mihrab’s date) but also two smaller borders, one of which was composed of luster half star and half cross tiles. Second, it documents the upper half of the mihrab in its original form. As we shall see, some of its over sixty tiles were soon removed, lost, or jumbled. Third, it shows the mihrab in relation to the wooden screen shielding the cenotaph, which Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh measured and described in 1876. Fourth and finally, the photograph captures some ritual objects and votives that confirm the tomb’s living sanctity despite the poor condition of some parts of the complex.

Shortly after visiting Varamin, Dieulafoy travels to Kashan and photographs a second luster mihrab in situ: the example dated Safar 623/February 1226 in the Masjed-e Meydan at Kashan (map) (fig. 29). The fate of this mihrab on the international art market would soon overlap with the Emamzadeh Yahya’s.

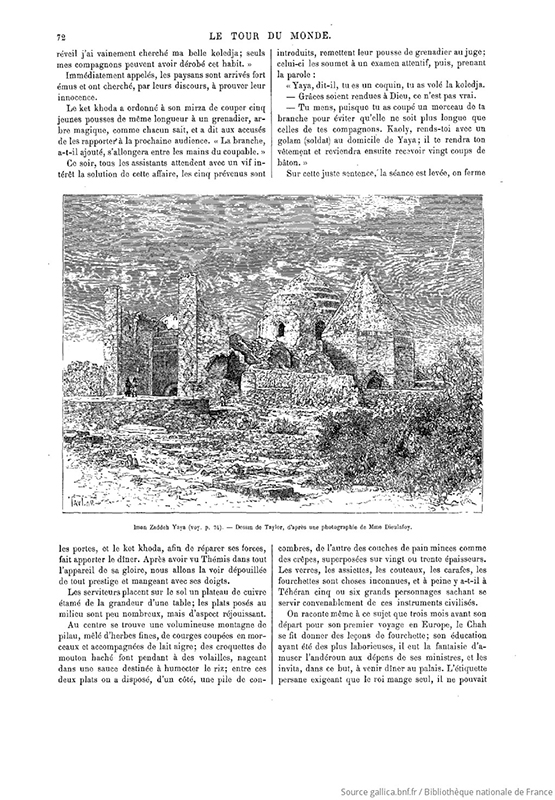

January 1883: Paris

Dieulafoy publishes the first of several articles about her Iran trip in the French newspaper Le Tour du monde. She describes “l’mam Zaddeh Yaya” as one of the most interesting monuments in the country and the only one that is closed and guarded. This is one of the earliest namings of the site in a public European forum. Unlike Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh and Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh before her, Dieulafoy does not read any inscriptions; instead, she focuses on the aesthetics of the tomb’s luster tilework, concluding: “Il n’est effectivement pas possible d’obtenir des émaux plus purs et plus brillants, des teintes plus égales, que ceux des revêtements de l’iman Zaddeh Yaya” (It is not possible to achieve enamels more pure and more brilliant, of even shades, than those of the Emamzadeh Yahya).34 She does not shy away from the removal of the tomb’s tilework and uses the terms ‘to steal’ and ‘theft’: “Quelques parties de ce revètement ont éte dérobées et vendues à Téhéran à des prix très élevés” (parts of this revetment has been stolen and sold in Tehran at high prices). Her use of the term ‘iman/m Zaddeh’ (emamzadeh) is also notable, given that earlier Europeans such as Bernay and Murdoch Smith had simply used the word ‘mosque.’ She describes the Emamzadeh Yahya variously as an ‘emamzadeh’ and a ‘mosque’ and seems to understand that the complex had various functions and a staggered evolution.

Dieulafoy’s article is accompanied by woodcuts after her 1881 photographs, but only ten of her twenty-nine photographs of Varamin are chosen for reproduction. Moreover, only two of the four of the Emamzadeh Yahya are included: her portrait of locals (see fig. 27) and general view of the site (see fig. 28), both with modifications made by the draftsmen (consider the lack of figures and additions). Dieulafoy’s important photograph of the mihrab in situ is notably excluded from reproduction. As a result, this important visual document remains hidden from public view until 2021, when her digitized photo albums are released online.

March–July 1885: London

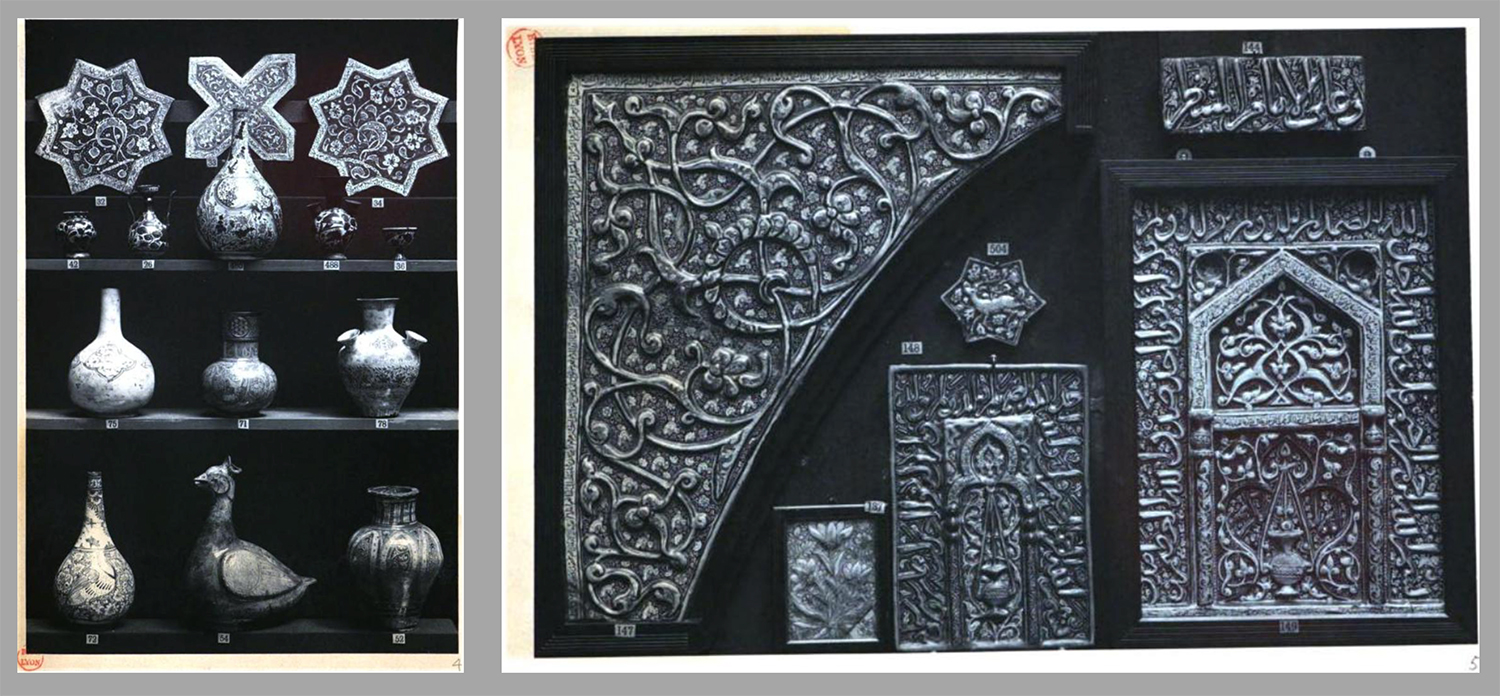

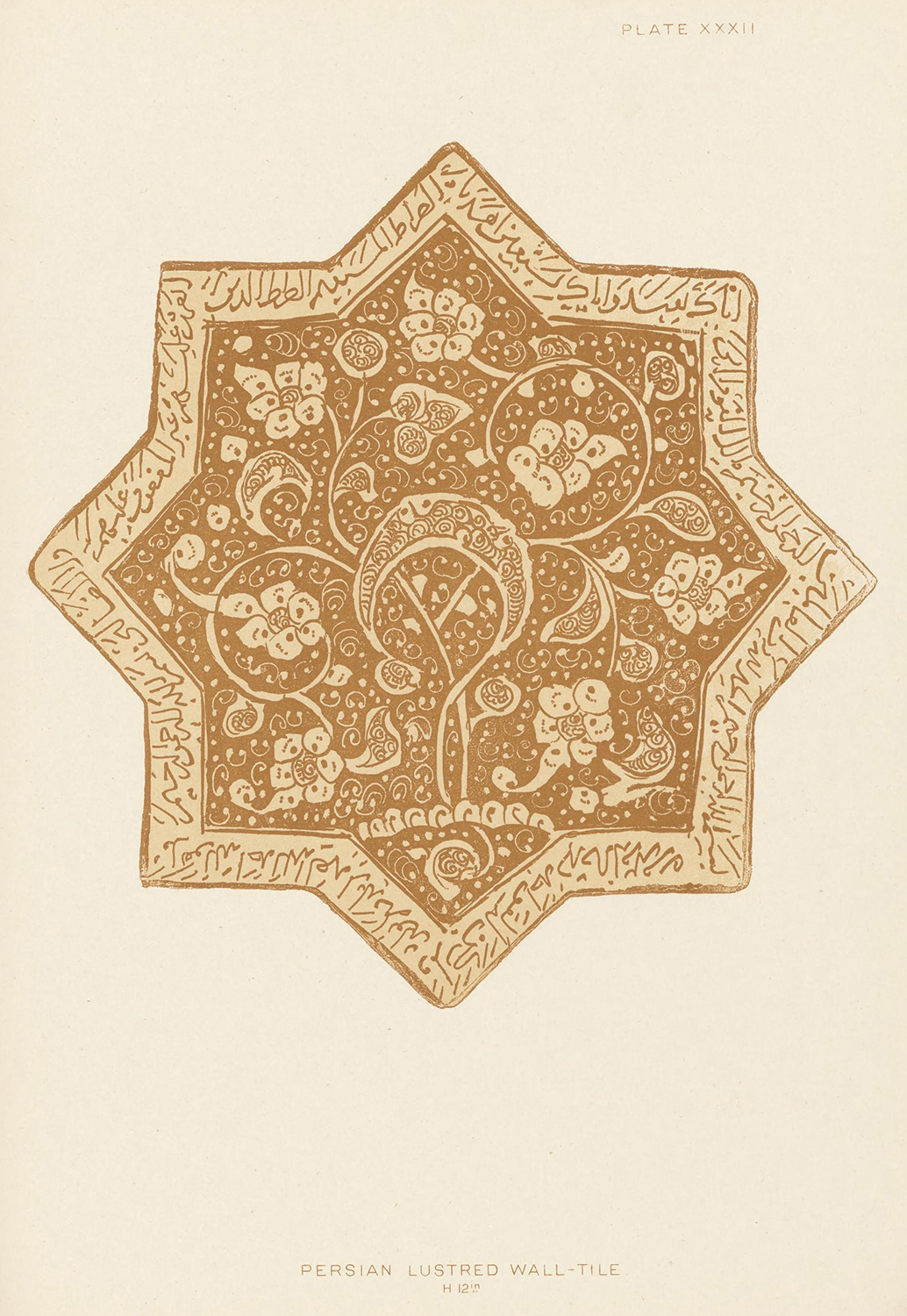

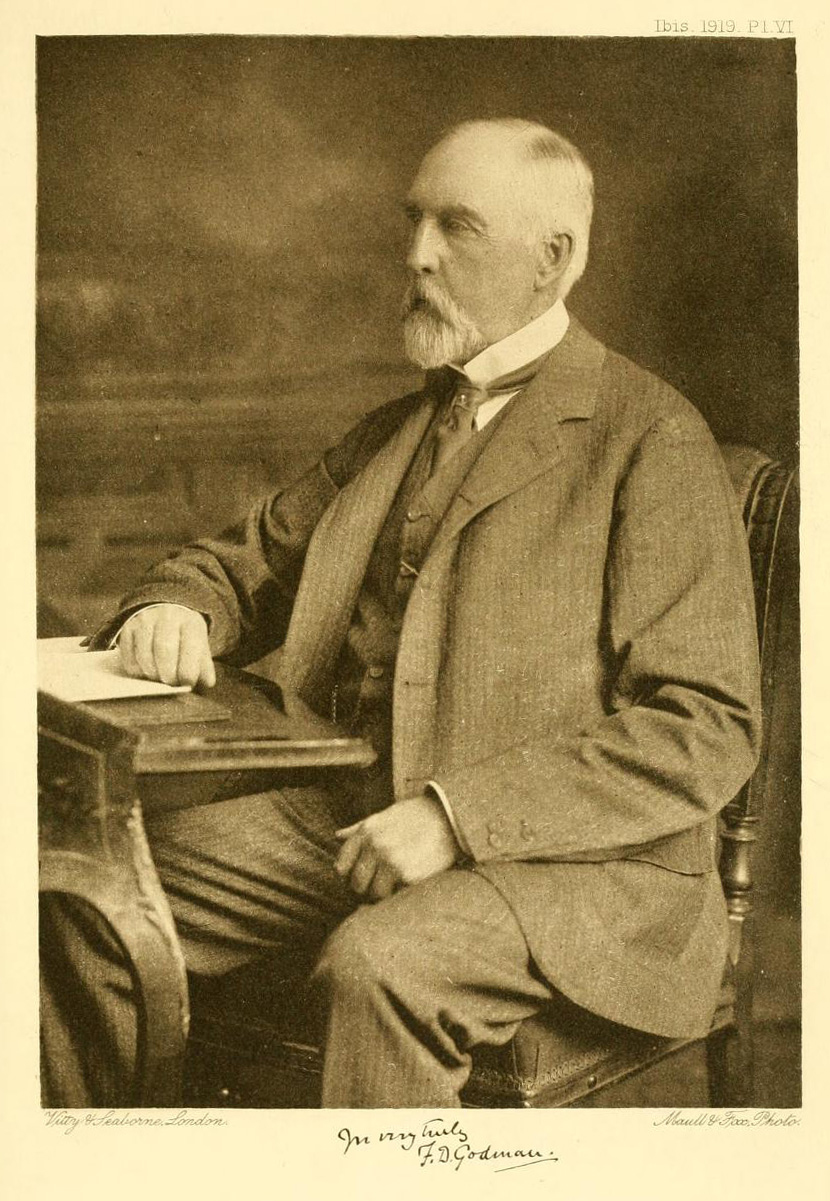

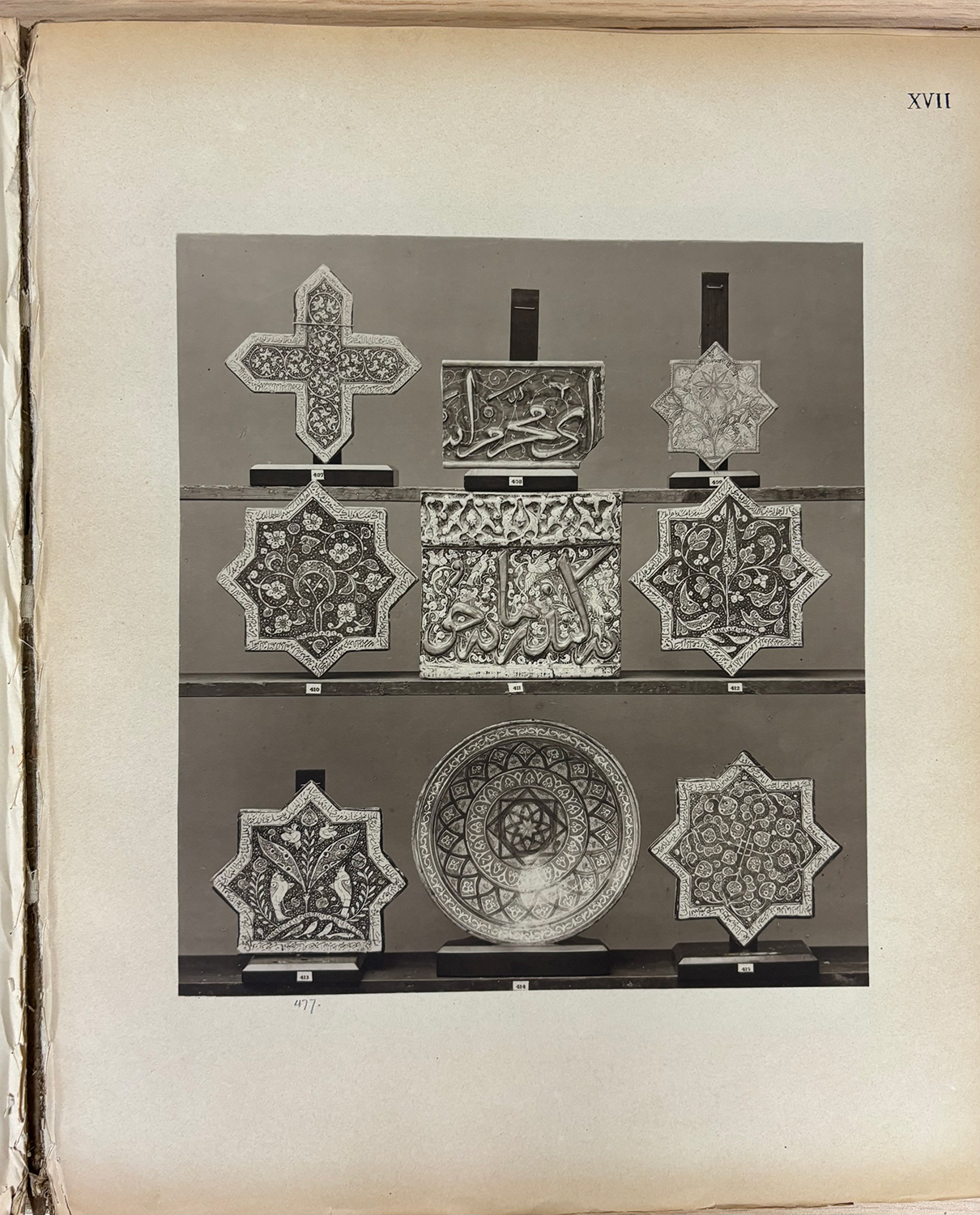

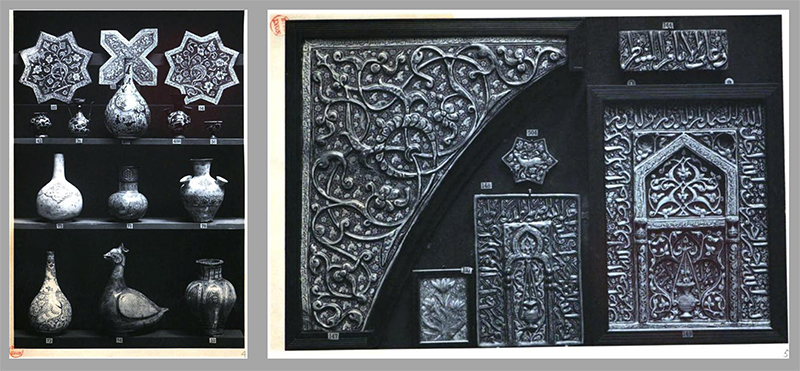

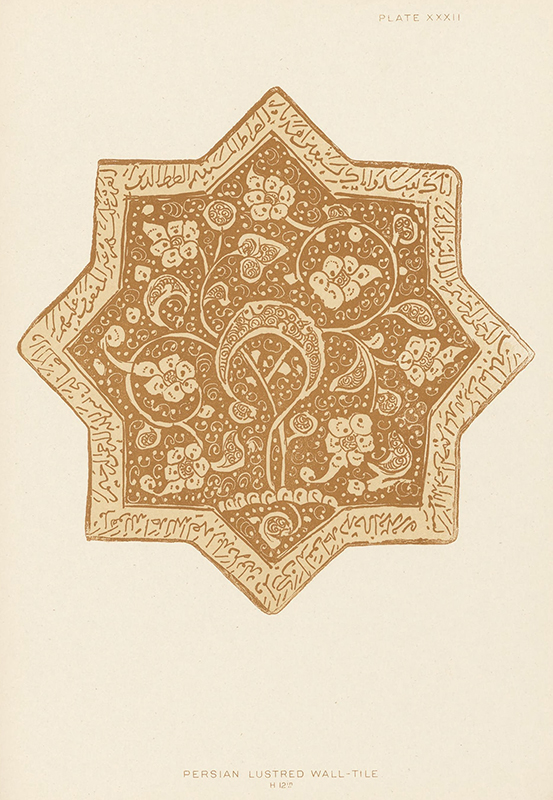

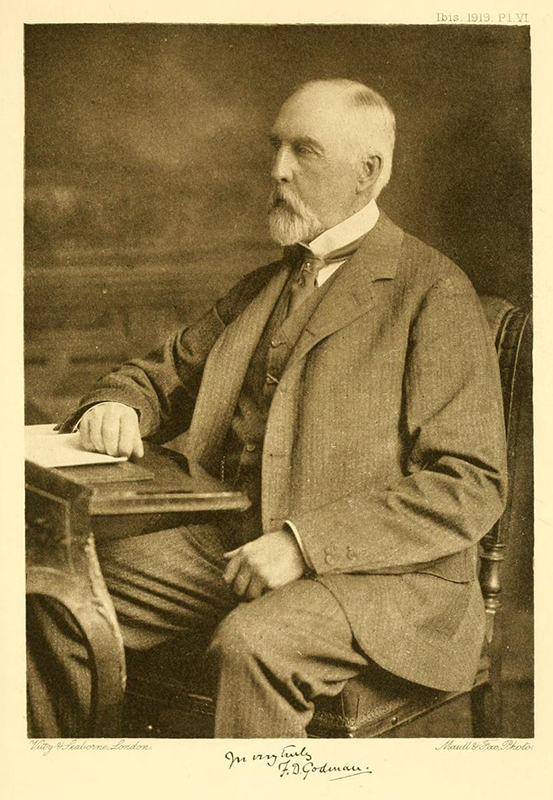

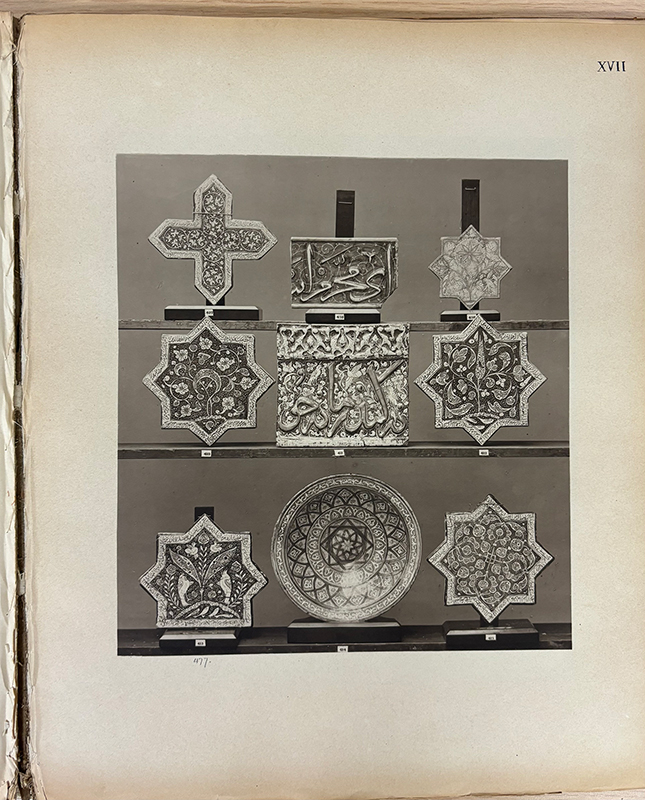

A four-month exhibition (18 March to 11 July) at the Burlington Fine Arts Club—a private gentleman’s club established in 1866 and located at 17 Saville Row in London (map)—is the first major exhibition of Persian art in Britain. The exhibition is spearheaded by English collector Charles Drury Edward Fortnum (d. 1899), has a high rate of visitation (4,198 visitors besides club members), and includes 606 loans from forty-one collectors, all of whom are members of the club and some of whom will become major figures in the collecting of Persian art.35 The exhibition includes a sizable number of Persian luster objects and tiles, including three tiles from the Emamzadeh Yahya’s dado, described simply as “Persian lustred wall tile” or “star tile” (fig. 31).36 The tiles are lent by English ornithologist and collector Frederick DuCane Godman (d. 1919) and praised by English painter Henry Wallis (d. 1916) for “the quality of the lustre and the severe grace of the designs.”37

The exhibition catalogue is available by preorder to members of the club and includes over thirty photographic plates of ‘objects’ with their catalogue numbers. Many plates show materials densely packed on shelves and walls, and luster tiles are often mixed with vessels. Single tiles once part of multi-tiled mihrabs, rectangular cenotaphs, and long friezes are framed alone, some literally in wooden frames and hung on the wall like paintings. All architectural context is lost in favor of the collectible trophy signifying the gentleman collectors’ supposed taste.

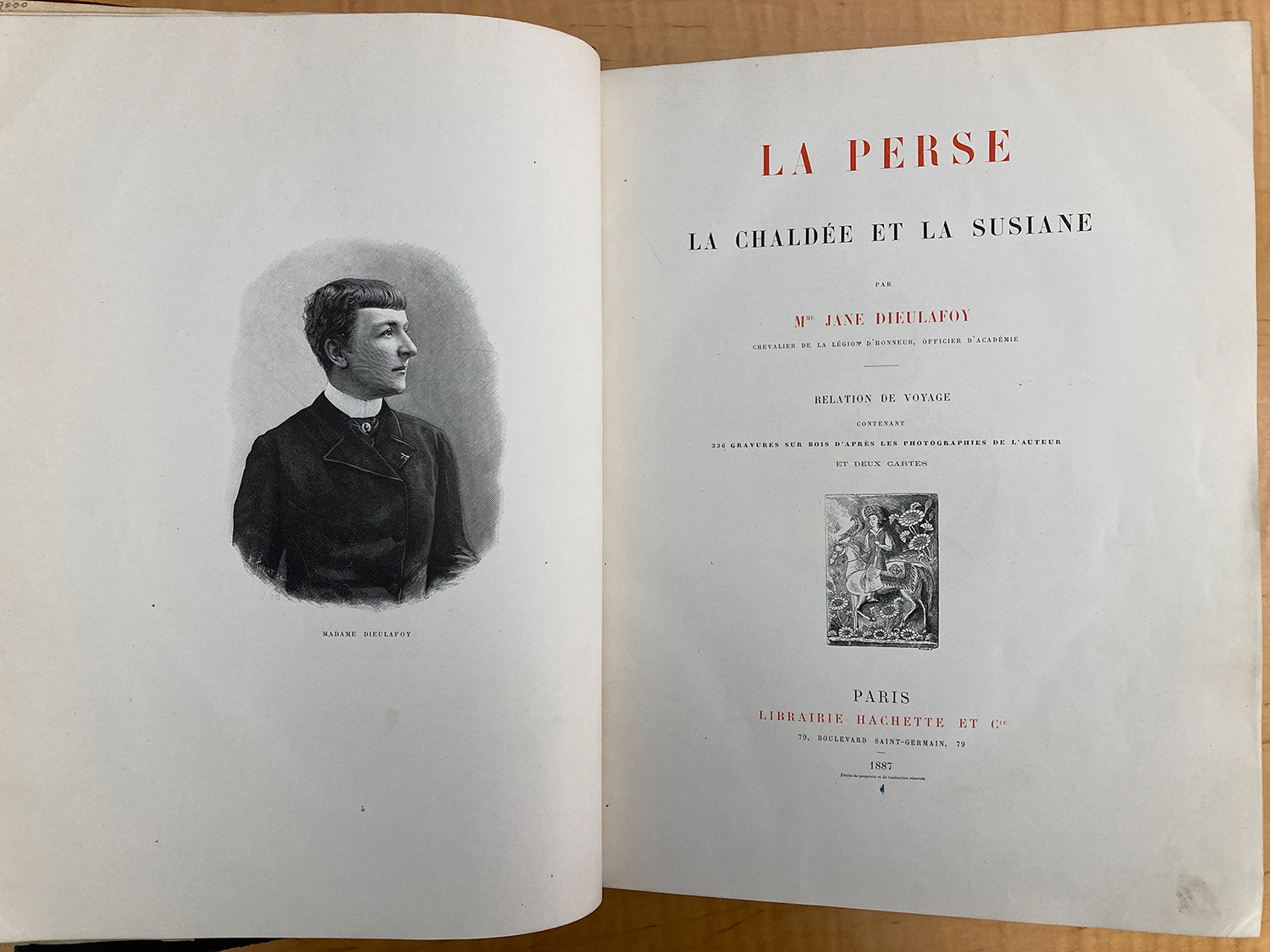

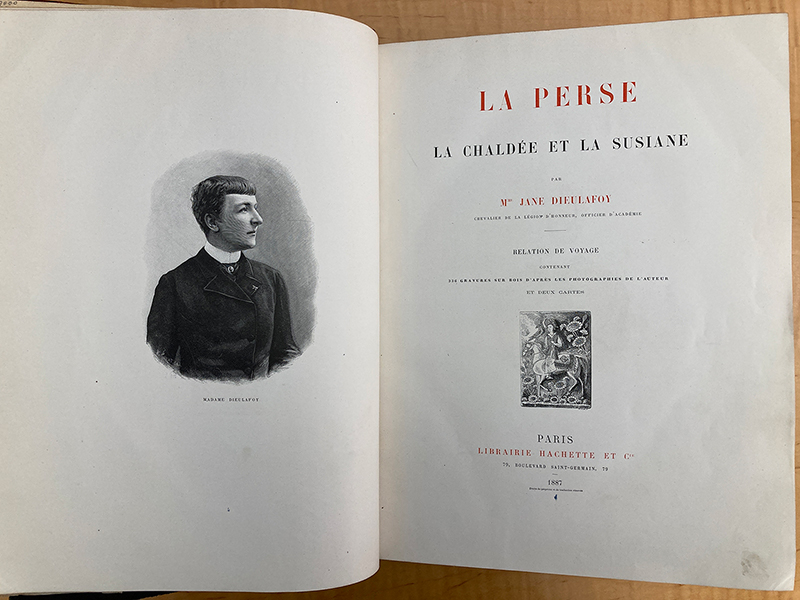

1887: Paris

Five years after her 1883 Le Tour articles, Dieulafoy publishes La Perse, la Chaldée et la Susiane, a lavish tome accessible only to a privileged few. The text and images in the Varamin section are very similar to those in the Le Tour article, but some small edits can be discerned. One example is Dieulafoy’s improved transliteration of the Emamzadeh Yahya: “Il n’est pas possible d’obtenir des émaux plus purs et plus brillants que ceux de l’imamzaddè Yaya.”38

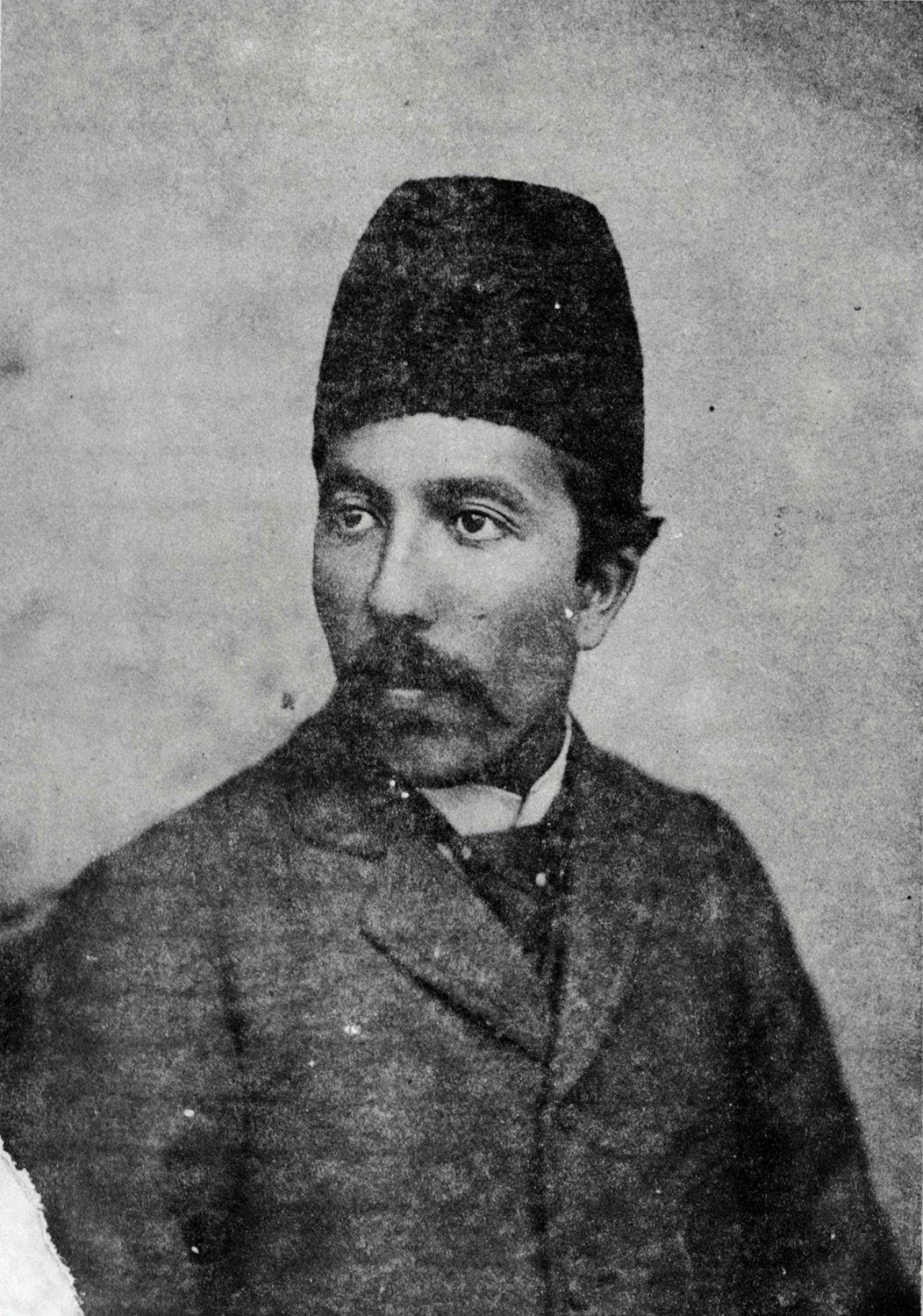

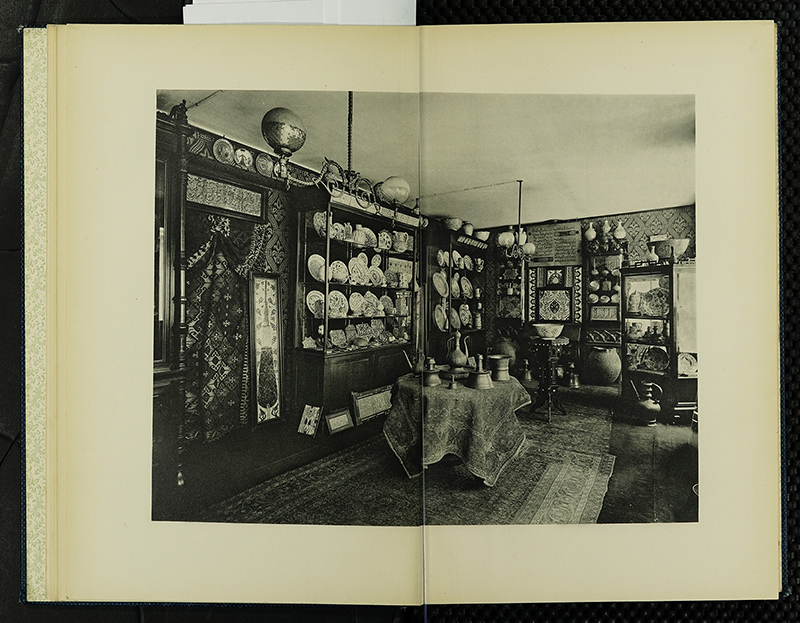

1880s: Tehran

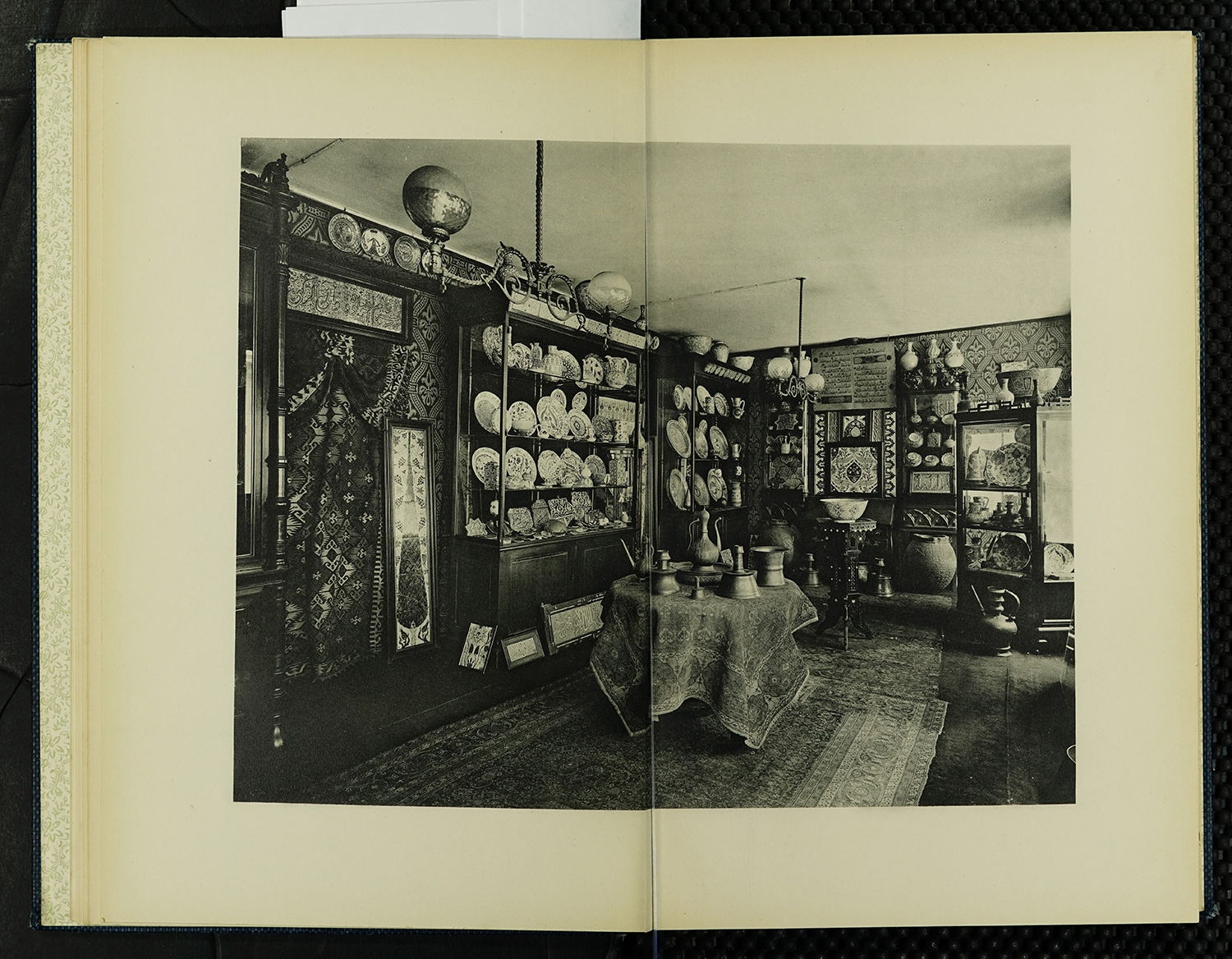

Antoine Sevruguin (d. 1933)—or a member of his studio—photographs a cabinet filled with many kinds of luster tiles and objects in Jules Richard’s (see fig. 15) Tehran house (fig. 33). Five tiles (three stars and two crosses) probably from the Emamzadeh Yahya are included in the cabinet and may have been recently removed from the tomb and transported to Tehran. This display presents a microcosm of Persian luster production between vessels and tiles and across many centuries (Ilkhanid to Qajar periods). It also represents the luster traditions of fifteenth- to sixteenth-century Spain (see the two large dishes at the top). The photograph is perhaps taken as a marketing device and used to draw more attention to Richard’s collection. He had already sold hundreds of luster pieces to the South Kensington Museum and would continue to diffuse his collection (for what we can locate today in this cabinet, see Luster Market).

1889: Vienna

On 23 March, the twenty-nine tiles acquired by the Imperial Royal Austrian Museum of Art and Industry in 1875, including the broken tile from the inner border of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab, officially enter the museum as part of an Übernahme (formal handover) from the Ministry for Trade (fig. 34).39 It is likely that the luster star and cross tiles attributed to the Emamzadeh Yahya had been exhibited a few years earlier (1884) in a ceramic exhibition at the Orientalischen (Oriental) Museum in Vienna.40 The mihrab’s broken tile does not appear to be listed in the catalogue and may not have been displayed. 41

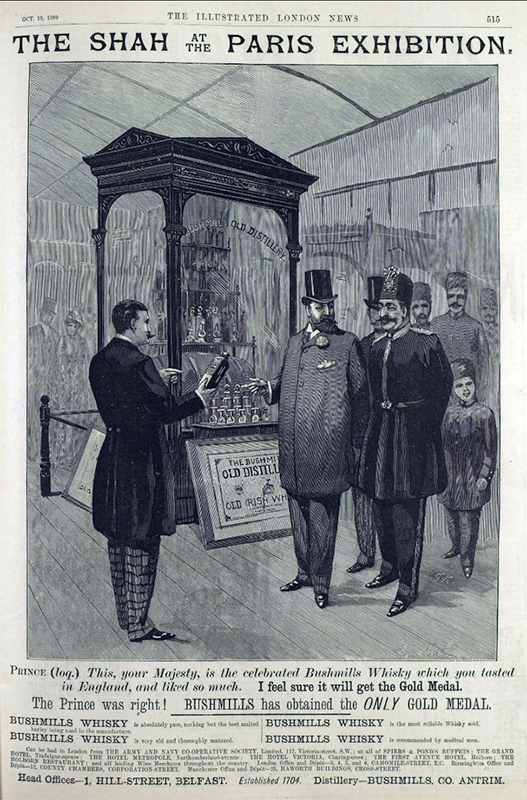

1889: Paris

The Exposition Universelle in Paris (6 May to 31 October) is a seminal node for the continued transfer and sale of luster ceramics and tiles. Naser al-Din Shah authorizes Frenchman E. Dorsy to organize the Persian pavilion and Jules Richard (see 1875–76), then seventy-three years old, and French composer Alfred Jean-Baptiste Lemaire (d. 1907) to display and sell their collections (fig. 35).42 According to a report by South Kensington’s agent Major Robert Murdoch Smith, Richard displays materials that he had previously exported from Iran and stored in Autrey-lès-Grays (Haute-Saône), his birthplace, for decades.43 Many individuals acquire works from Richard, including English collector Lindo Myers and, once again, Murdoch Smith.44

Naser al-Din attends the exhibition during his third trip to Europe and records his impressions in his diary (fig. 36). He describes seeing Richard at the exhibition and how the Frenchman had acquired “Iranian old stuff” (اسبابهای کهنه ایران)—including old tiles from shrines (کاشیهای کهنه امامزاده) and broken tiles excavated from Shahr-e Rey—from dealers and other Iranians or as gifts.45 The shah does not condemn the display of tiles from shrines and also estimates that Richard sold things for thirty times more than their acquisition price.

During his visit to the Louvre, Naser al-Din Shah meets Jane Dieulafoy once again (see 1881). The Dieulafoys had excavated Susa three years earlier (1885–86) and taken most of the finds to France, violating the agreement. As a result, the French were barred from the site and invited the shah to Paris to appease the relationship. The exhibition appears to have had the desired positive effect, at least for the French, as the shah withdrew his protest.46In his dairy, Naser al-Din Shah describes seeing the Susa materials in the Louvre (fig. 37):

امروز هم میخواستیم اسبابهای دلافوا را ببینیم که از شهر سوس که شوشتر باشد بیرون آورده است ببینیم. مادام دلافوا آمد جلو او را دیدم. . . خلاصه از یکی دو اتاق رد شده داخل اتاقی که اسبابهای دلافوا بود شدیم اگرچه اسباب زیادی نیاورده است ولی اینکه آورده است خوب است. صورت سربازهای دارا آورده، سنگهای بزرگ که آن وقت ستون عمارت دارا بوده و تمام را حجاری کرده بودند و شکل گاو داشت آورده بود و از این قبیل، خیلی چیزهای خوب بود همه را تماشا کردیم.

Today, we wanted to see the objects brought by Dieulafoy from the city of Suse, which is Shushtar. Madame Dieulafoy came forward, and I saw her . . . In short, after passing through one or two rooms, we entered the room where Dieulafoy’s objects were displayed. Although she did not bring many items, what she did bring was good. She had brought the statue of Darius’s soldiers, large stones that were once columns in Darius’s palace—fully carved and shaped like bulls—and similar items. There were many remarkable things, and we looked at them all.47

Naser al-Din Shah’s indifferent reaction to seeing Iran’s material culture on view in Paris is now often considered a sign of incompetence and disregard for the country’s cultural heritage. Just before he died in 1895, the shah once again granted France the right to excavate throughout Iran, including at Susa.

1894: London

Henry Wallis publishes an exclusive monograph (two hundred copies) of Frederick DuCane Godman’s luster tilework collection, illustrated with forty-two plates of chromolithographs (figs. 38–39). On the tiles’ provenance, Wallis writes:

It appears that perhaps all the wall-tiles forming the subject of the present illustrations have been brought to London by dealers in works of art. Either the dealers are ignorant of the provenance of the objects or they decline to give information on this point; in any case, it is difficult to obtain exact information as to the locality of the buildings to which they belonged. All that the present writer can assert with confidence is that some came from Veramin and others from Koum [Qom] and Natinz [Natanz].48

Wallis identifies twelve star and cross tiles measuring 12 inches (30.48 cm) as “Veramin tiles” and “well known to collectors” and later refers to their original location as the “mosque and monastery at Veramin.”49

December 1897: Varamin

German art historian Friedrich Sarre (d. 1945) visits Varamin and surveys its major monuments. Unlike Dieulafoy sixteen years earlier (1881), he is denied entry into the Emamzadeh Yahya but takes an important general photograph of the site. It will take over a decade for him to publish this view (jump ahead to 1910).

1899: Berlin

Friedrich Sarre displays his collection at the Museum of Applied Arts (now Gropius Bau) in Berlin (map). His collection includes many luster tiles acquired during his travels in Iran, some presented as single tiles and some as larger panels. The latter includes a panel of stars and crosses from the Emamzadeh Yahya, immediately distinguished by their large size.50

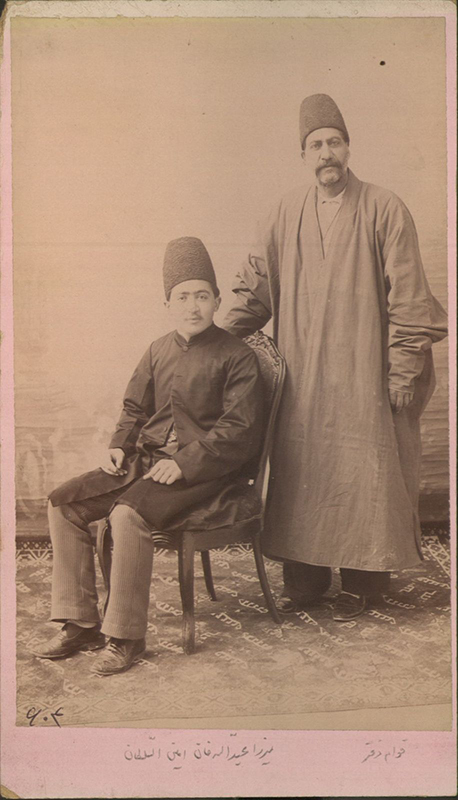

July 1900: Tehran to Paris: The Journey

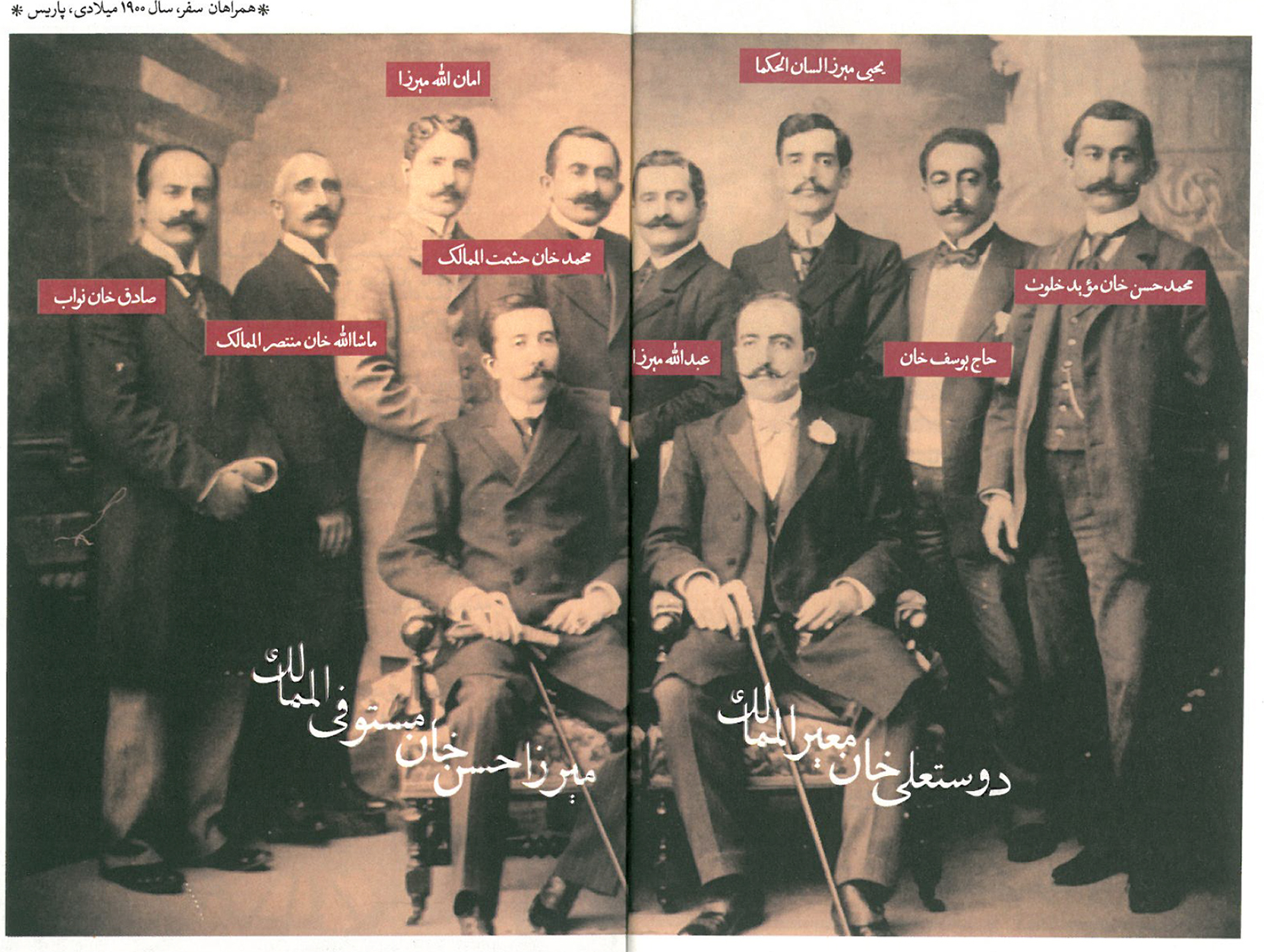

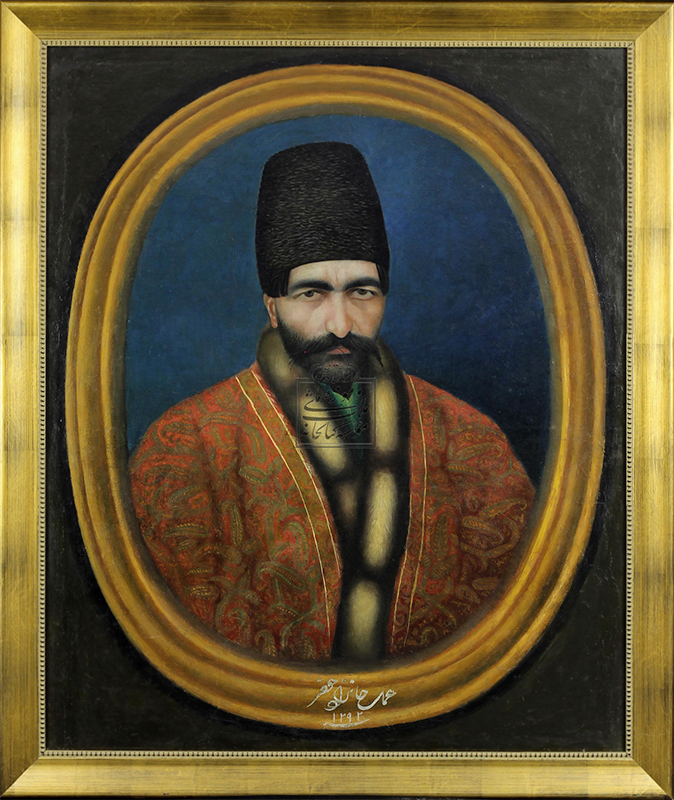

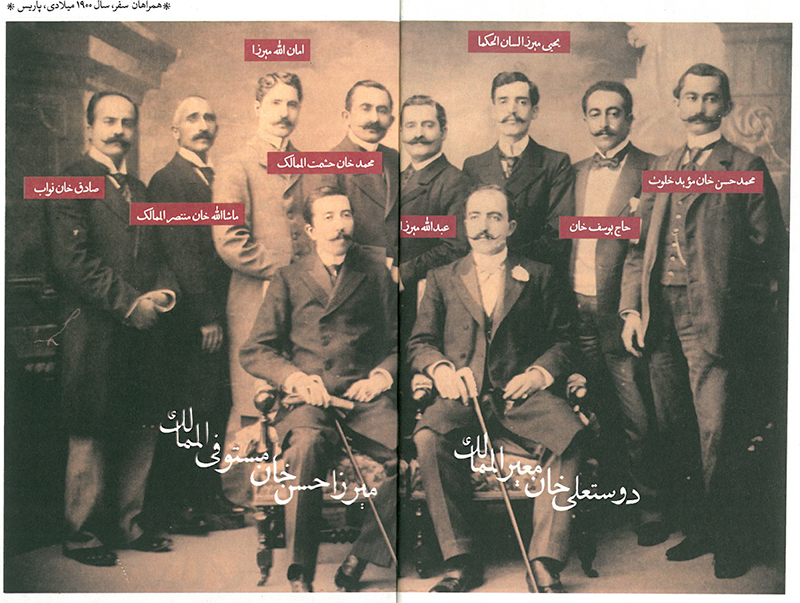

The Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab is shipped to Paris, likely via Tehran, among the belongings of Mirza Hasan Khan Ashtiani Mostowfi al-Mamalek, known as ‘Aqa’ (آقا), an honorific bestowed on his father, Mirza Yusof Ashtiani (d. 1886), by Naser al-Din Shah and that he inherited (fig. 42). This is the first trip abroad for the young Mirza Hasan Khan, who is twenty-six years old, and who travels to Paris by carriage, ship, and train via Baku, Tbilisi, Kiev, Warsaw, and Berlin.51 At the time, he does not hold an official position, but he had earlier served as the chief state accountant (Mostowfi al-Mamalek) under Naser al-Din Shah, a post he had also inherited from his father.52

Mirza Hasan Khan Ashtiani apparently hoped to exhibit and sell the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab at the Exposition Universelle, but it is not clear if it was transported with his caravan or shipped separately to Paris. In his memoir, he recounts feeling anxious about customs officers in Baku inspecting the group’s crates and relief when they let them pass without opening them:

آمدم بخوابم چون صبح سر دسته کشتی میرسد بادکوبه. باید زود بیدار شویم. حاضر باشیم ببینیم با عمله جات گمرک چه خواهیم کرد. . . کشتی رسید به بادکوبه، لنگر انداخت. عملهجات گمرک حاضر شدند و منظم بارها را آوردند بیرون. پیش از وقت بارها را خیلی از عملهجات گمرک بردند ولی برعکس کمال معقولیت را کردند هیچ یک از بارهای ما را باز نکردند، رد کردند.53

I went to sleep, since by morning the ship would reach Badkubeh [Baku]. We had to wake up early and be ready to see what we would do with the customs workers . . . The ship arrived in Badkubeh [Baku] and dropped anchor. The customs workers came and unloaded the crates in an orderly way. Earlier, many of the customs workers had taken away cargo, but, quite to the contrary, they acted with complete reasonableness: not a single one of our crates was opened—they let them pass.

It is currently unclear when and how the mihrab was removed from the Emamzadeh Yahya and entered Mostowfi al-Mamalek’s possession. We know it was in situ in 1881, but we also know that at least one tile from the ensemble was in Vienna by 1875, if not earlier. It is probable that individual pieces were taken from the mihrab while it was still in the tomb, thus coinciding with the removals of luster tiles from the dado and cenotaph. It is also possible that significant time had elapsed between the mihrab’s complete theft from the tomb and its shipment to Paris in 1900. In other words, it could have been stored in Iran for years. On the uncertainties and mysteries surrounding the Emamzadeh Yahya during this period, see our chronological history of the shrine.

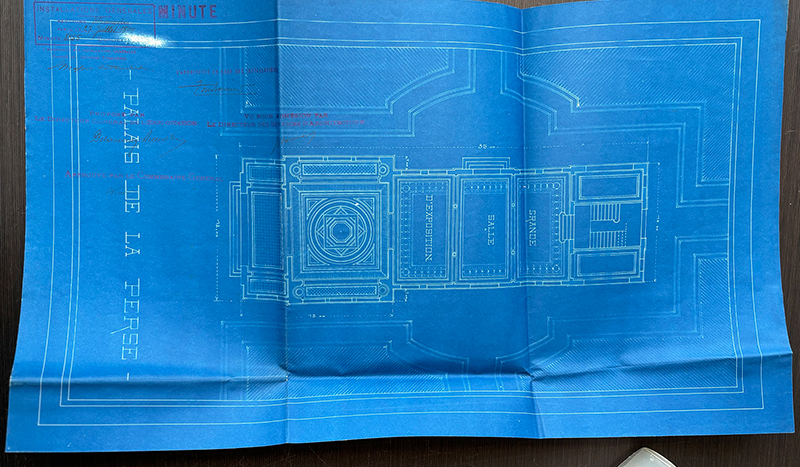

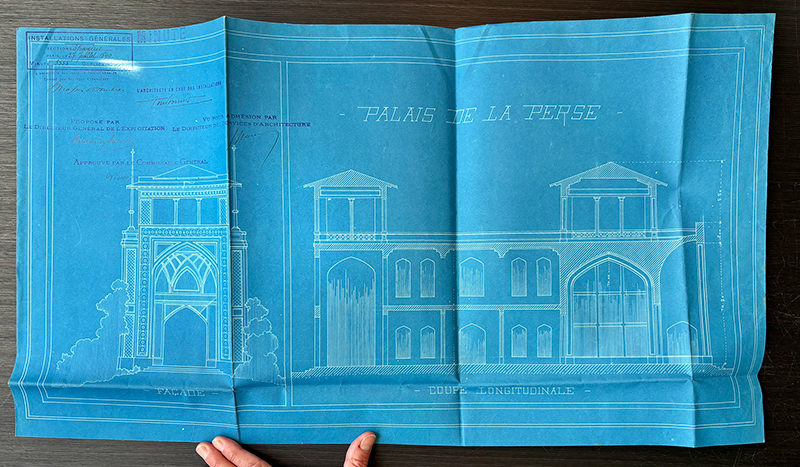

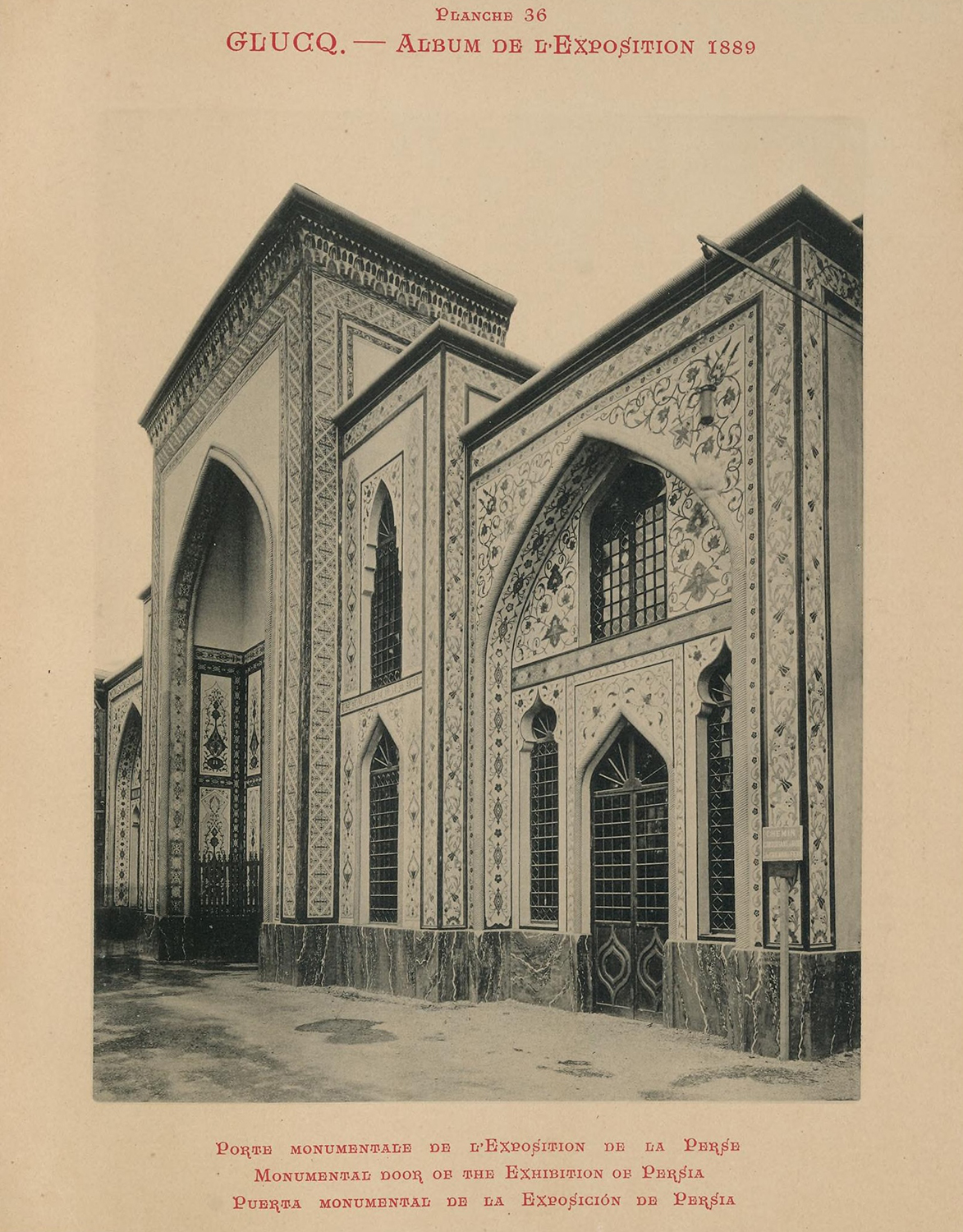

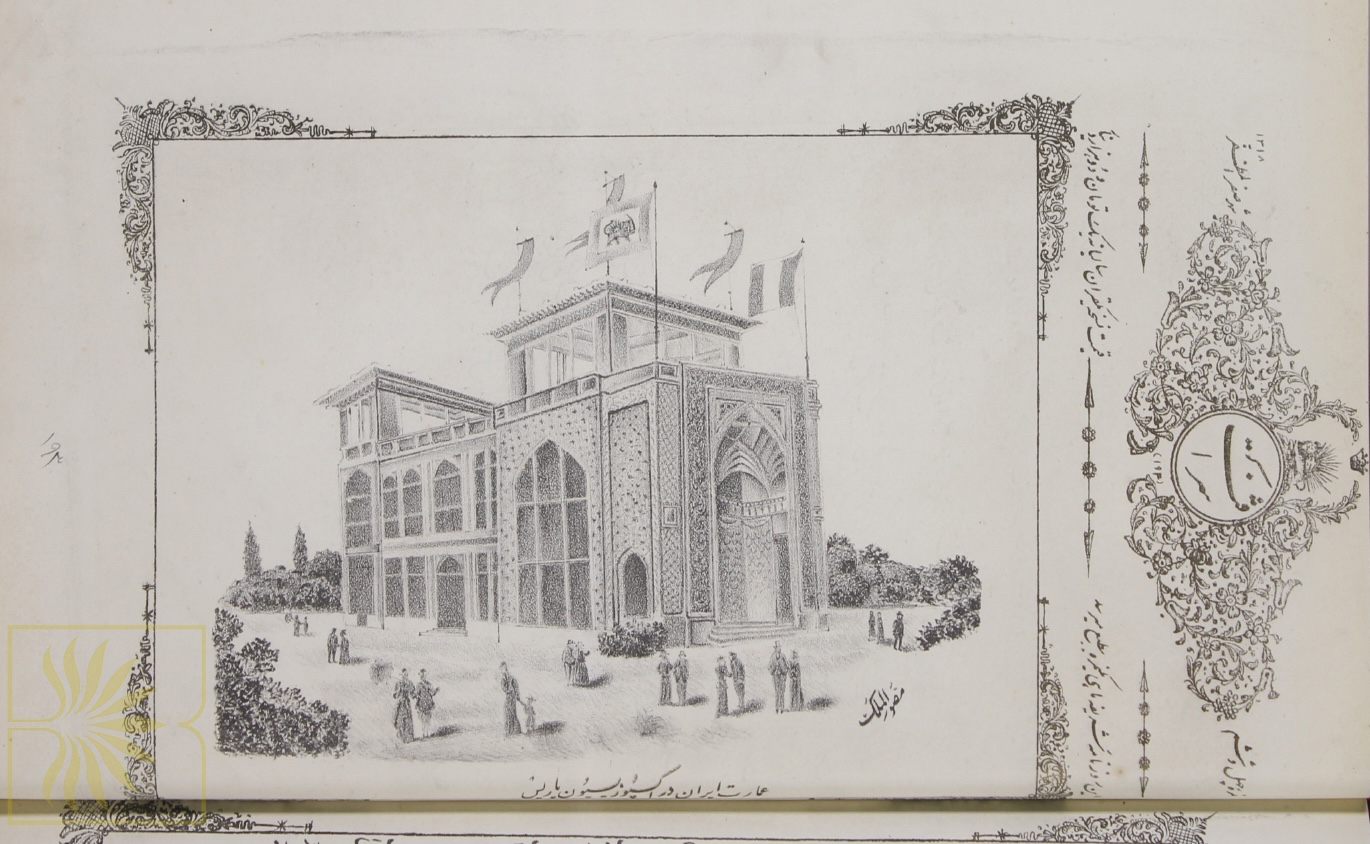

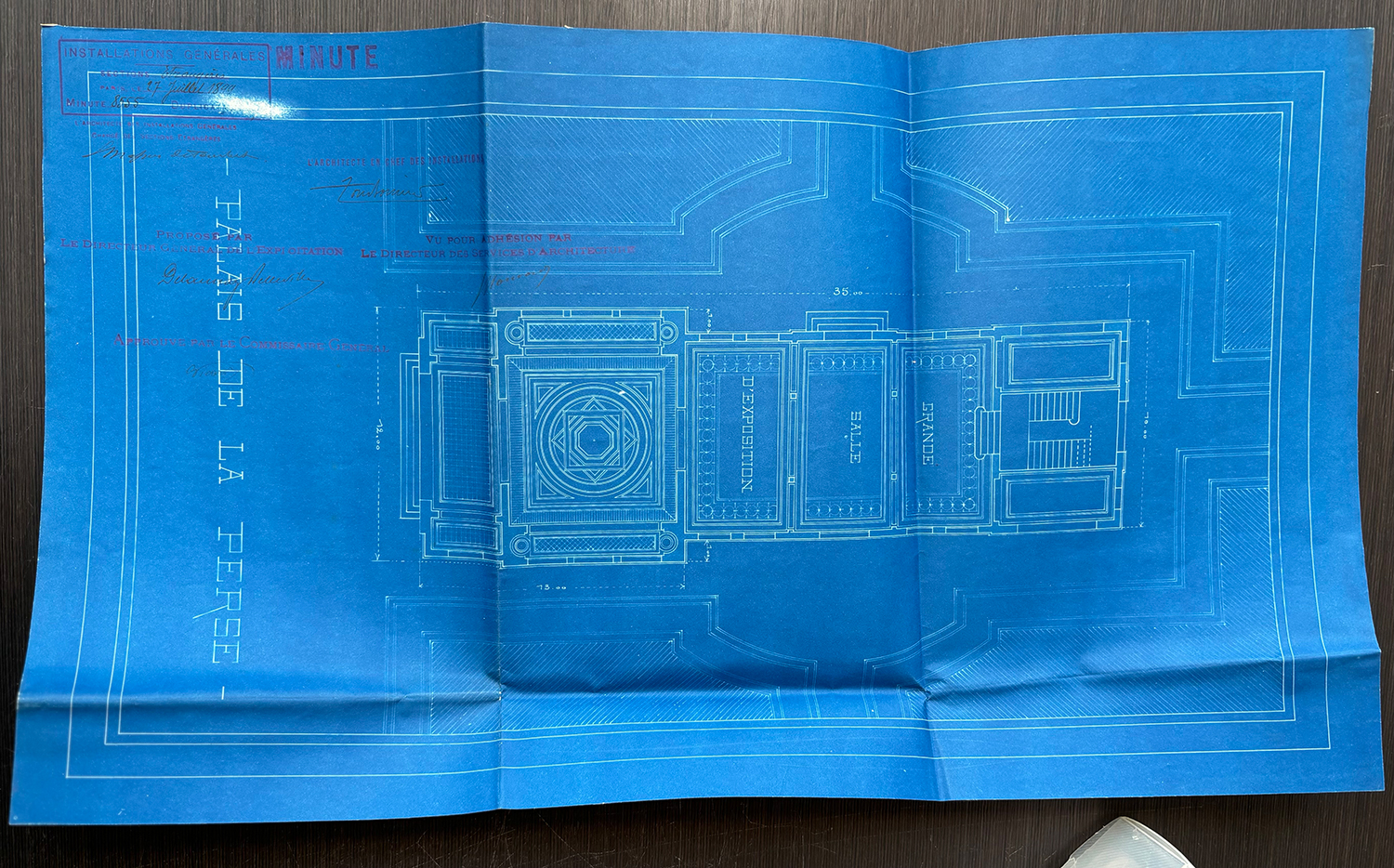

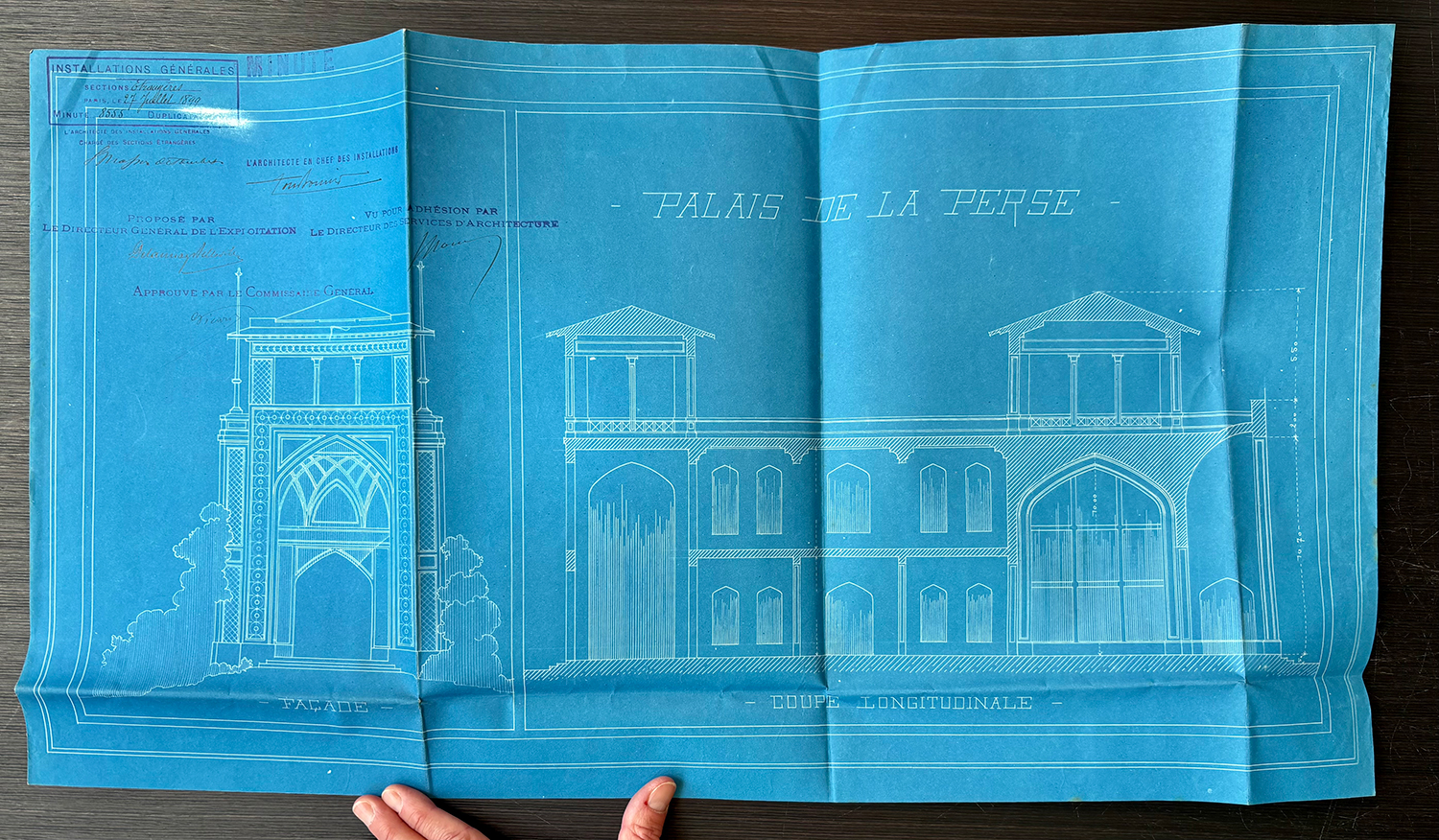

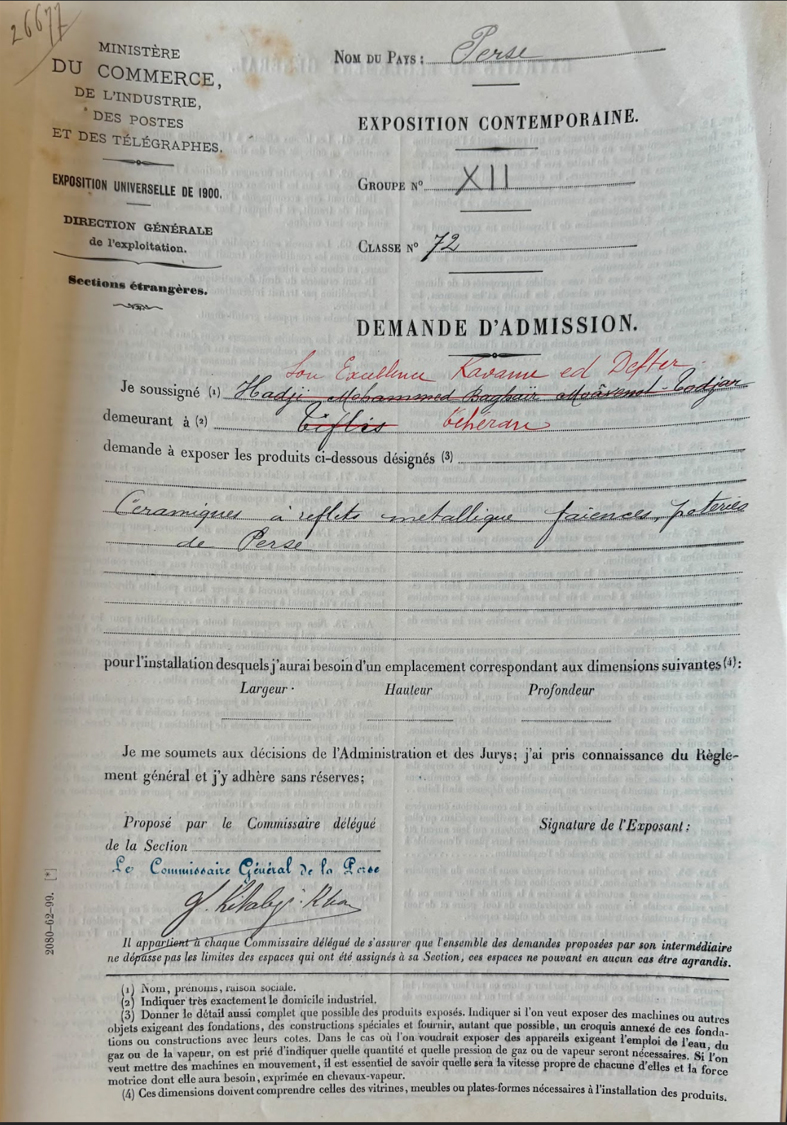

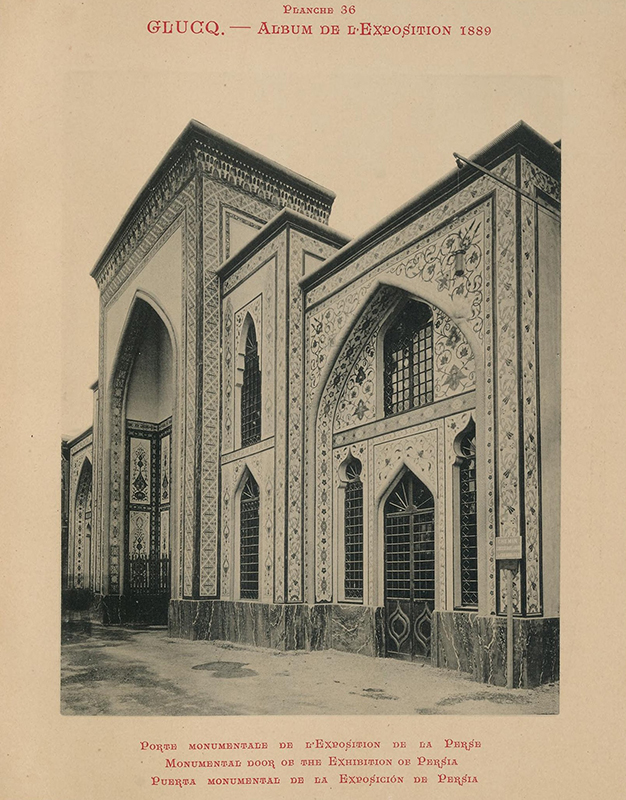

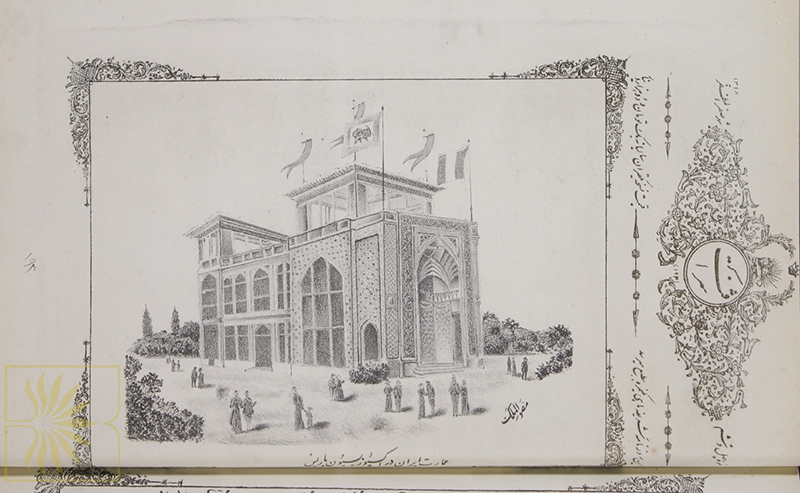

April–November 1900: Paris: The Exposition

The Persian pavilion is one of more than fifty pavilions representing forty-three ‘nations’ at the Exposition Universelle (fig. 43). It is designed by French architect Philippe Mériate under the supervision of General Antoine Kitabgi Khan (d. 1902), the General Commissioner for Persia, and said to reproduce “le Palais Medressyé Maderschachi,” in fact the Madreseh-ye Chahar Bagh in Esfahan (map).54 The multistoried, long building includes three rooms comprising the “grand salle d’exposition,” a theater, and several pillared terraces (figs. 44–45).

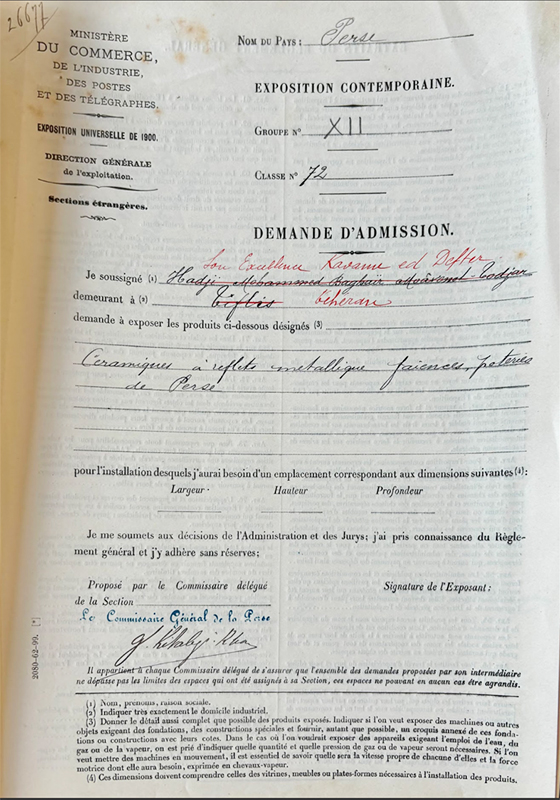

Individuals approved to show materials by application to the French Ministry of Commerce, Industry, Posts, and Telegraphs include Iranian officials like Mirza Hossein Khan Mostowfi Qavam Daftar and Hossein Quli Khan, photographer Antoine Sevruguin (see fig. 33), and dealers like Dikran Kelekian (d. 1951) (fig. 46).55 The Parisian dealer Clotilde Duffeuty, to whom we shall soon return, gives tours explaining the displays.

The Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab does not appear to have been exhibited, for had it been displayed, it would have garnered immense attention and been mentioned in one of the many accounts of the Persian pavilion (for example). Sarre will later record that he saw it in an unassembled state (“in noch nicht wieder aufgebautem Zustand”) in Paris in 1900, and Hagop Kevorkian will later maintain that Mozaffar al-Din Shah (r. 1896–1907) forbade Mostowfi al-Mamalek from displaying it (jump ahead to 1913).56

Mozaffar al-Din Shah visits the exposition in late July, during his first trip to Europe (fig. 47).57 At the Persian pavilion, he purchases some things like “un simple touriste” (a simple tourist) and awards some titles and medals to key individuals involved in the pavilion, including the dealer Kelekian.58 While in Paris, the shah holds meetings with French officials about Susa, which was then under the purview of French archaeologist Jacques de Morgan (d. 1924).59 Before he leaves the French capital, Mozaffar al-Din Shah signs the third Franco-Persian archaeological convention, which renders the French monopoly perpetual and grants all Susa finds to France.

September–November 1900: Paris to Iran: The Letters

During his journey to Paris, Mostowfi al-Mamalek is accompanied by several Qajar princes, including his brother-in-law Dust-ʿAli Khan, a member of the prominent Moʿayyer al-Mamalek family. The correspondence between these Qajar elites in Paris and their relatives back in Iran, namely Dust-Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek (d. 1912), Dust-ʿAli Khan’s father and Mirza Hasan Khan Ashtiani’s father-in-law, reveals how they spent considerable sums of money acquiring things on their trip, particularly at the Exposition Universelle, and how urgently they sought additional funds.60 One apparent source of financial support for this extravagant spending was the sale of valuables brought with them from Iran, notably pearls and tiles. A letter from Amanollah Mirza Jahanbani (d. 1912) to Dust-Mohammad Khan on 28 Jamadi al-Awwal 1318/23 September 1900 reflects on the uncertain prospects of selling pearls and tiles and expresses frustration over the lack of interested buyers:

به هر حال مرواریدها فروخته نشده، نه مال آقا [میرزا حسن خان مستوفی الممالک] و نه مال اعتصام السلطنه [دوستعلی خان معیرالممالک]. تا کاشیها با همه این هنگامهها چه کند. متاع قوام دفتر [میرزا حسین خان آشتیانی] چنانچه عرض شده است به حضور عالی هیچ خریدار ندارد مگر چند عدد کاشی که دارد خوب میخرند تا با ما چه کنند کاشیخرها. هنوز وقت را باید بگذرانیم.61

The pearls have not been sold—neither those belonging to Aqa [Mostowfi al-Mamalek] nor those of Eʿtesam al-Saltaneh [Dust-ʿAli Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek]. So let us see what becomes of the tiles [kashiha] amid all this commotion. The goods of Qavam Daftar [Mirza Hossein Khan Mostowfi], as has been previously mentioned, have found no buyers, except a few tiles that are being well received. Let us see what the tile-buyers [kashi-kharha] will do with us. For now, we must simply wait.

«تا با ما چه کنند کاشیخرها. هنوز وقت را باید بگذرانیم.»

(Let us see what the tile-buyers will do with us. For now, we must simply wait.)

Qavam Daftar was a member of Mozaffar al-Din Shah’s entourage and had previously served as Chief Accountant of the Royal Construction Bureau (مستوفی بناخانه) (fig. 49).62 His large collection of manuscripts, rugs, and tiles was shown at the Exposition Universelle (see fig. 47), attracted the attention of reporters, and was soon offered separately for sale (jump ahead to December 1900).63

In another letter to Dust-Mohammad Khan, Amanollah Mirza notes the arrival of the tiles in Paris and expresses uncertainty about how they should be stored. Although the letter is undated, its reference to the exposition suggests that it was written before the event concluded in November:

در خصوص کاشیها، امروز کاشیها وارد پاریس شد. هنوز مصمم نیستم که در کجا آنها را باید گذارد. به بعضی ملاحظات مصمم نشدهایم. تا دو روز دیگر ناچار به مابقی کاشیها را [؟] گذارد. از این مطالب و شهرتها خیلی دلتنگ شدم. اگر چه آشکار بود که این مطالب باید رخ بدهد.64

As for the tiles, they arrived in Paris today. I am still undecided about where to store them. Due to certain considerations, we have yet to come to a decision. In two days, the remaining tiles must be [?] stored. I became very upset by these reports and rumors [shohratha], even though it was clear that such things were bound to happen.

While the letters do not identify the tiles explicitly, they suggest that controversy surrounded them in Iran and likely among the Persian entourage in Paris. Unfortunately, a missing word in this part of the letter makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions, but if the tiles in question indeed belonged to the Emamzadeh Yahya’s luster mihrab, the rumors in question could refer to tensions between Mostowfi al-Mamalek and Mozaffar al-Din Shah, stemming from the former’s having taken them to Paris (jump ahead to 1913). These letters reveal that at least four Iranian elites—one back in Iran (Dust-Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek) and three members of the visiting Persian delegation (Qavam Daftar, Amanollah Mirza, and Mirza Hasan Khan Mostowfi al-Mamalek)—were aware of and/or directly involved in the attempted sale of tiles in Paris.

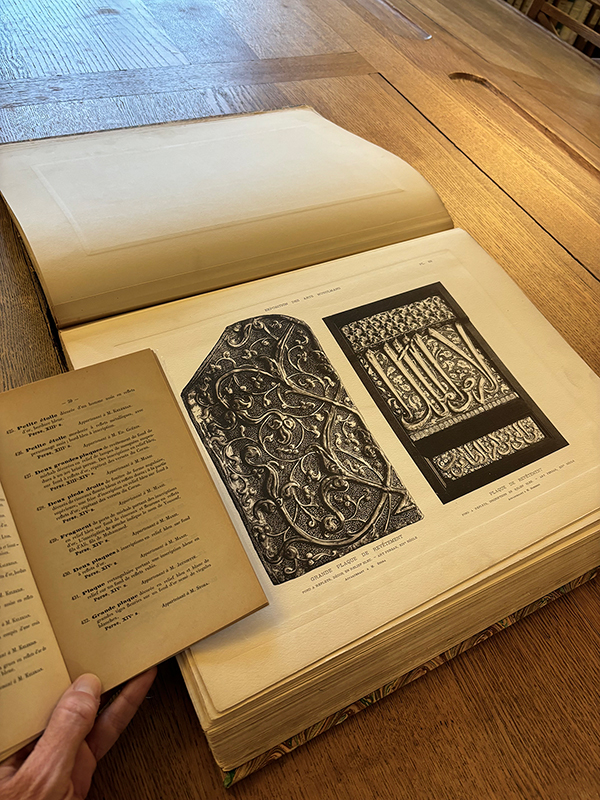

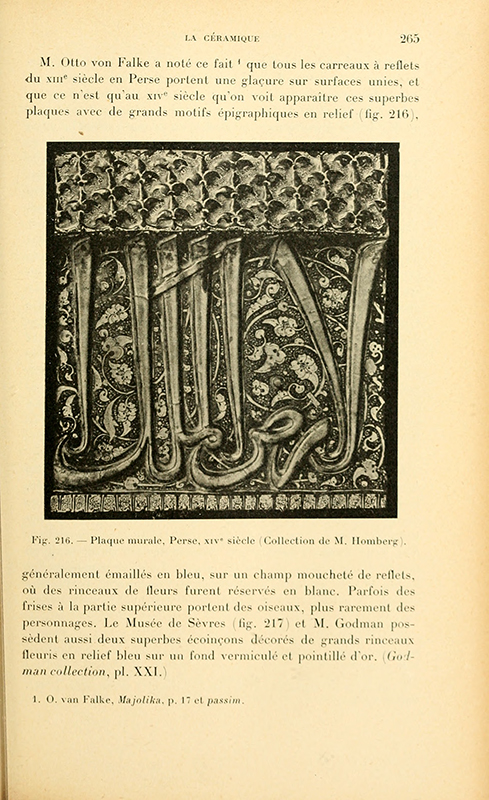

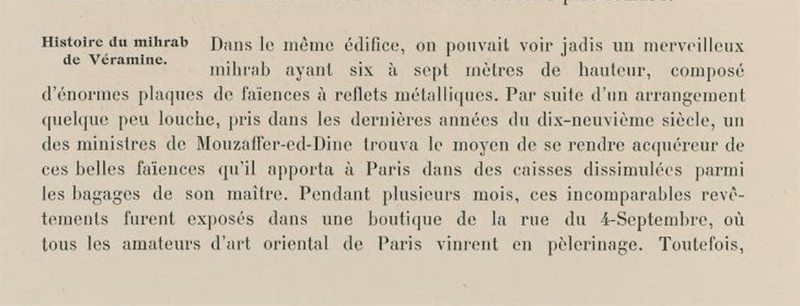

1900–1: Paris: The Related Sales and Displays

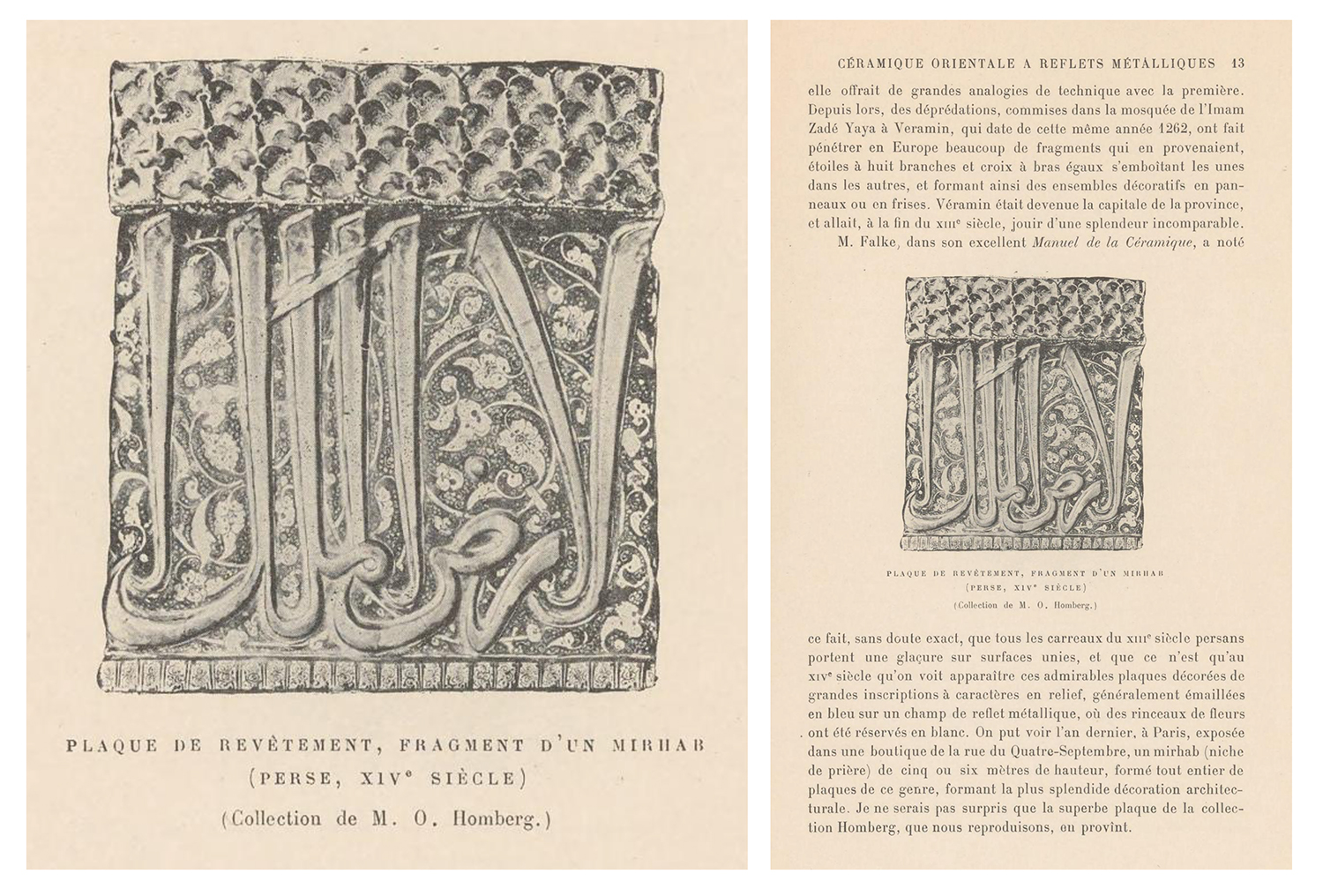

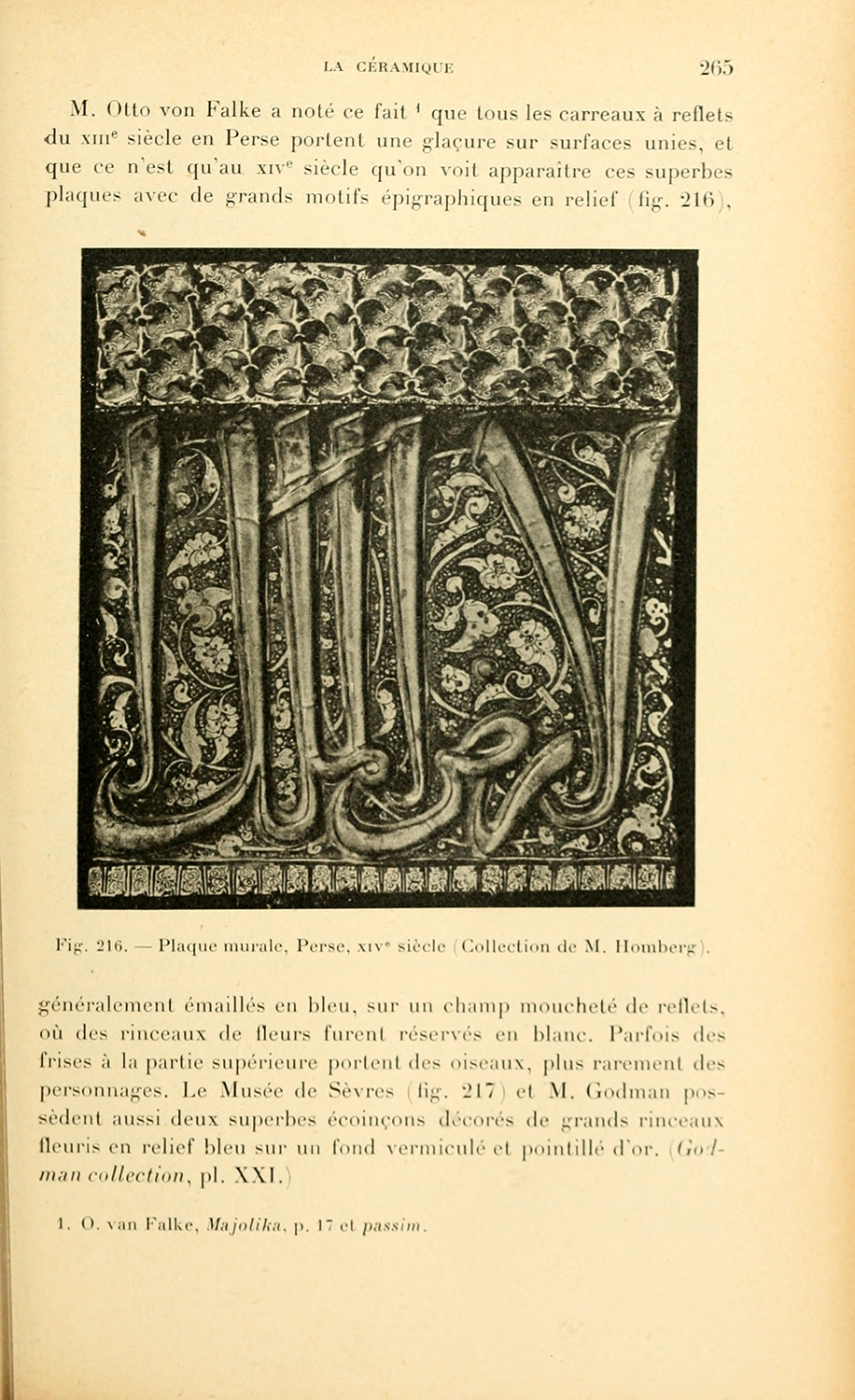

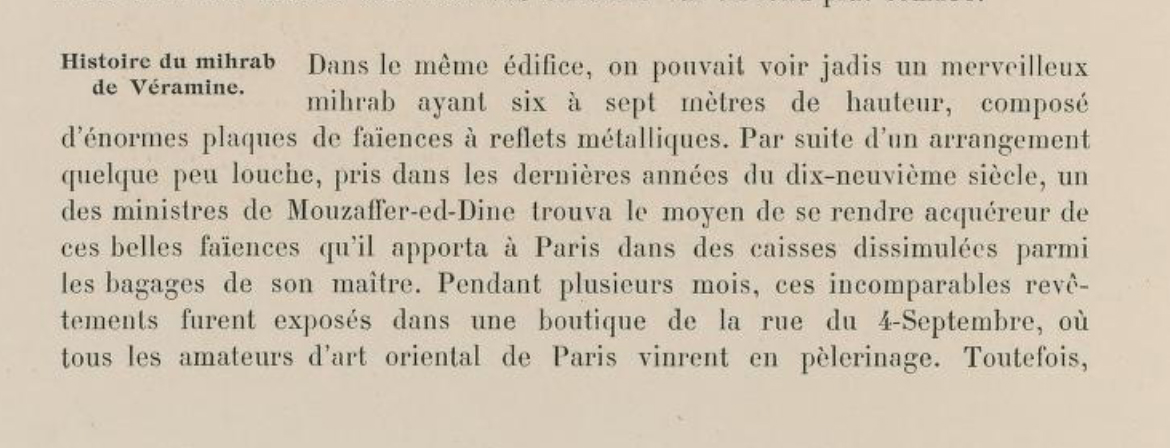

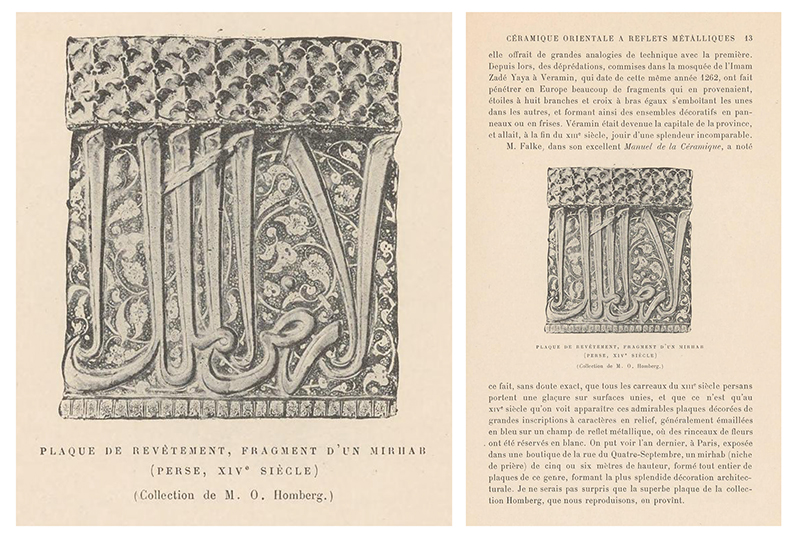

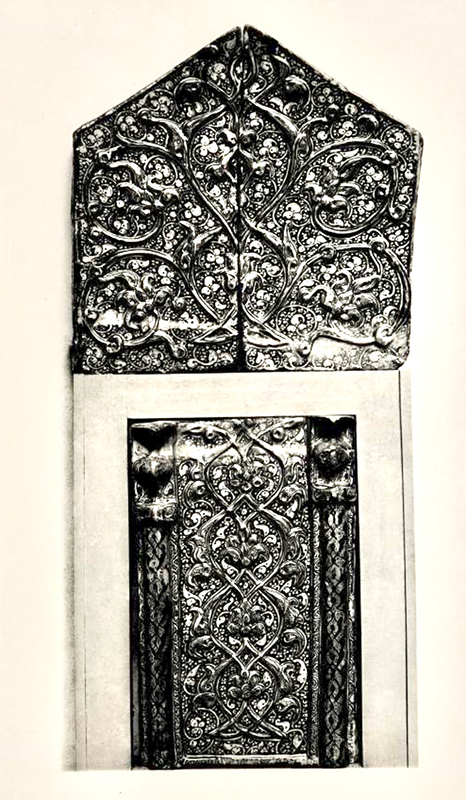

Apparently prohibited from inclusion in the Exposition Universelle, the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab is displayed in a boutique on the rue du 4 septembre (map), one of the new (1864–69) boulevards distinguishing Baron Haussmann’s (d. 1891) renovation (and destruction) of historical Paris. The earliest known mention of this display occurs in French art historian Gasteon Migeon’s (d. 1930) Céramique orientale, a short text on luster inspired by some of the Louvre’s recent acquisitions, including a thirteenth-century vase attributed to ‘Rhagés,’ or Rey. After summarizing some of the major sales and collectors of the day, Migeon describes how damage in “la mosquée de l’Imam Zadé Yahya” resulted in many of its tiles being brought to Europe, including star and cross tiles dated 1262.65

Below, Migeon reproduces a single luster tile belonging to French banker and collector Octave Marie Joseph Kérim Homberg Sr. (d. 1907) (fig. 50).66 He writes:

On peut voir l’an dernier, à Paris, exposée dans une boutique de la rue du Quatre-Septembre, un mirhab [sic] (niche de prière) de cinq ou six mètres de hauteur, formé tout entier de plaques de ce genre], formant la plus splendide décoration architecturale. Je ne serais pas surpris que la superbe plaque de la collection Homberg, que nous reproduisons, en provînt.67

Last year, in Paris, a mihrab (prayer niche) of five or six meters high was exhibited in a store on the rue du Quatre-Septembre, made entirely of panels of this kind [luster tilework], forming the most splendid architectural decoration. I would not be surprised if the superb panel from the Homberg collection, which we reproduce, came from it.

Migeon was correct. The tile Homberg possessed had been removed from the mihrab’s outer border of twenty-four tiles with the first five verses of sura al-Jumuʿah. Inscribed with two words from the first verse ([ا] لارض الملک ا[لقدوس]), the tile would have been the fourth example in the lower right. This was not the first tile isolated from the mihrab (recall Vienna 1875), but it is the first known publication of a displaced tile from the outer border. As we will see, it would not be the last.

The display of the mihrab on the rue du 4 Septembre (map) in 1900 appears to have been momentous. In his 1911 travelogue (jump ahead), Henry-René d’Allemagne (d. 1940) would record, “Tous les amateurs d’art oriental de Paris vinrent en pèlerinage” (all the amateurs of Oriental art in Paris went on pilgrimage [to see it]).68 A comparison of this act of so-called pilgrimage in 1900 Paris (by the Parisian connoisseur to see the displaced mihrab) to the act of ziyarat (pious visitation) to the Emamzadeh Yahya itself (by the Qajar delegation in 1863 and many pilgrims before and after) underscores the profound dissonance between the mihrab’s original architectural context and its reception in Paris.

The exact boutique in question remains unknown, but preliminary research suggests that it may have been that of Alfred Perret and Ernest Vibert, located at number 33 (map).69 Founded in 1875, this boutique was notable for its Chinese, Japanese, and ‘Oriental objets d’art’ and participated in the 1900 Exposition Universelle. A connection can also be made to Jane Dieulafoy. In February 1903, Perret and Vibert chairs were used in a performance of Andromaque (Andromache) starring Sarah Bernhardt (d. 1923) and held in Jane Dieulafoy’s salon, which was also decorated with replicas of glazed bricks from Susa (visible behind Bernhardt in this photograph). Perret and Vibert are known to have sold other forms of Persian tilework, including a cabinet with Qajar-period underglaze tilework. Considered all together, these circumstances suggest that Perret and Vibert might have been involved in the mihrab’s display in Paris in 1900.

At the end of December 1901, the collection of Qavam Daftar (“Gavame Defter”), the aforementioned member of the Persian delegation (see fig. 49), is offered for sale at Hôtel Drouot. The cover of the sales catalogue emphasizes that the collection was displayed in the Exposition Universelle and highlights an “importante plaque de revetment à reflets métalliques” (important luster tile). This sizable vertical tile (17.71 × 31.5 in.) is purchased by French dealer Maurice Stora (d. 1950) and was likely the left side of the central hood of a luster mihrab, underscoring that Iranian officials were also involved in the sale of tiles with problematic acquisition histories.70

May 1901: St. Petersburg

In May 1901, the Stieglitz Central School of Technical Drawing in St. Petersburg purchases another tile from the mihrab’s outer border (fig. 51). The tile is acquired from Parisian dealer Clotilde Duffeuty (d. 1934), who had given tours of the Persian pavilion at the Exposition Universelle and perhaps purchased the tile at the exposition or a related sale (fig. 52).71 In the Stieglitz inventory book, the tile is described as “Изразецъ съ металл. отблескомъ съ гробницы имама Зади-Яга из Верамина” (Russian orthography of the early twentieth century; Tile with metal[lic] reflection from tomb of imam Zadi-Yaga from Veramin).72 The shrine was therefore known, and we can assume that Duffeuty was aware that the tile came from the mihrab then in Paris.

The tile’s inscription (السموات و ما فی ا ) confirms that it preceded the example in Homberg’s possession and would have been the third in the sequence. It would take another thirty-five years (jump ahead to 1935) for this tile to be identified as part of the mihrab’s outer border and be conceptually reunited with the whole.

1901: London

Seven years after the publication of his Persian luster tile collection using chromolithographs (see 1894), English collector Frederick DuCane Godman publishes a larger catalogue of his entire ceramics collection. This tome is illustrated with photographic plates and facilitates a more detailed appreciation of the luster tiles, at least for those privileged enough to see the exclusive work “printed for private circulation only.”73 Godman devotes the entire second paragraph of his introduction to Jules Richard and notes that “a considerable addition was made in 1889 by the purchase of the Richard Collection in the Paris Exhibition of that Year.” This emphasis confirms that Richard’s collection continued to retain considerable prestige as an (the most?) esteemed provenance.74

Video 4. Turning the pages of The Godman Collection of Oriental and Spanish Pottery and Glass, 1865–1900, 1901. Video by Keelan Overton of the copy in the British Museum, June 2024.

The plates conform to existing trends of displaying luster tiles as singular isolated ‘objects’ (fig. 53 and vid. 4). Several star and cross tiles from the Emamzadeh Yahya are included and mounted to the wall or wooden bases, some with wires across their surfaces. All works are accompanied by a small number indicating when they entered the collection. The numbers of the Emamzadeh Yahya tiles range from the 160s to the early 400s, revealing that Godman bought these tiles over many years and had a sustained interest in them.75

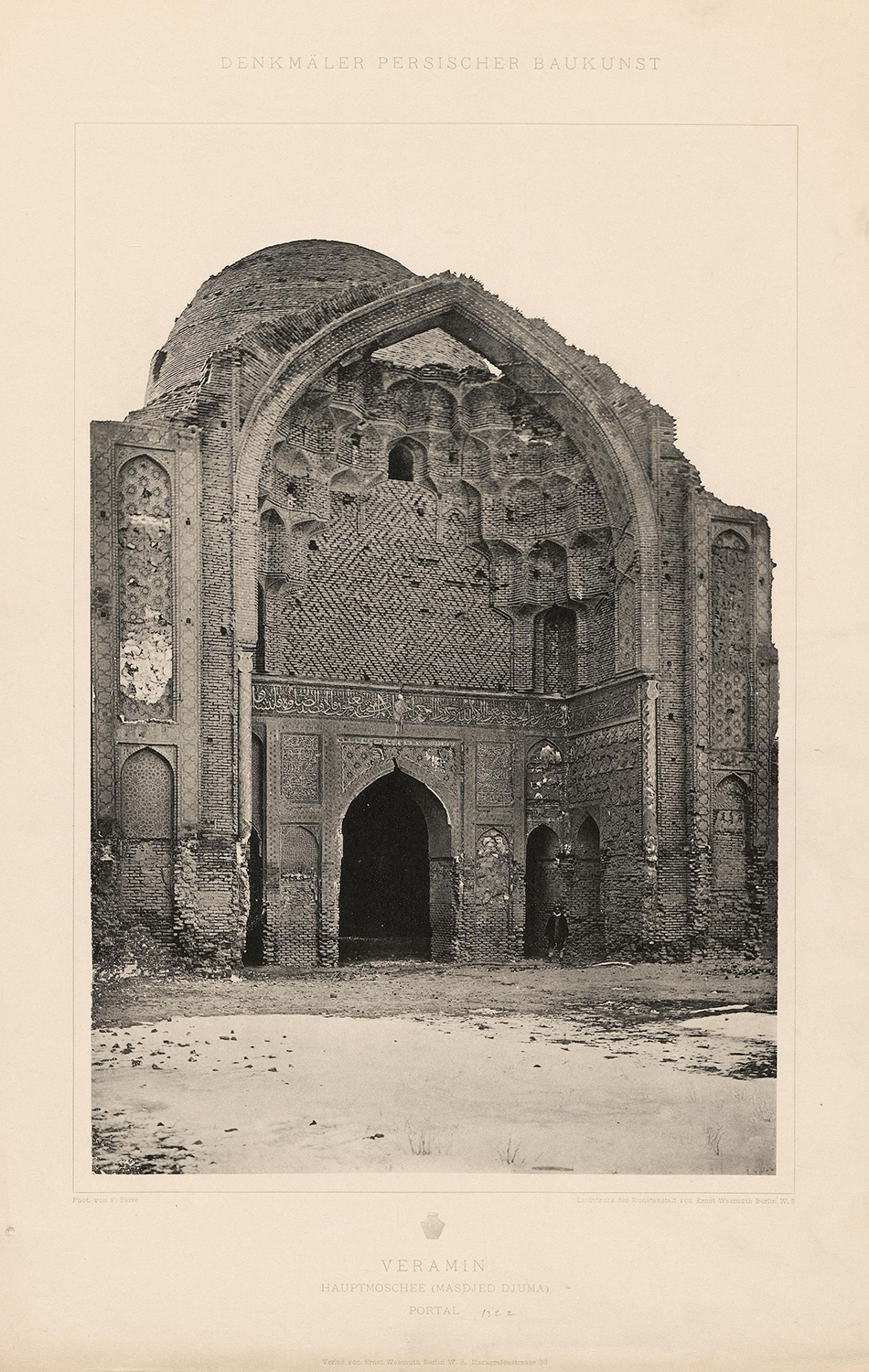

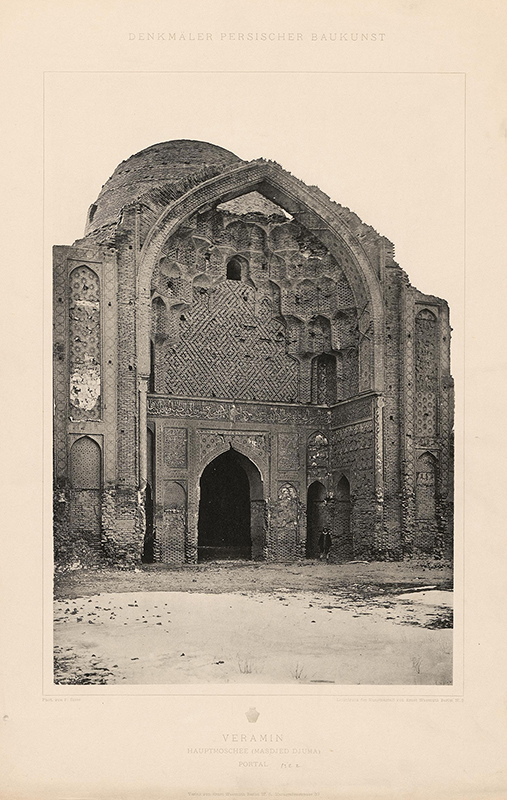

1901: Berlin

Friderich Sarre publishes many of his architectural photographs of Iran in the plate volume of Denkmäler Persischer Baukunst. He includes four images of Varamin’s Ilkhanid congregational mosque, located in central Varamin to the northwest of the Emamzadeh Yahya (map) (fig. 54). He also reproduces fragments of glazed and unglazed revetment in his collection and indicates one source as the congregational mosque (“der Hauptmoschee [Masdjed Djuma] in Veramin”). He must have taken these fragments from the unguarded and out of use mosque, which was then in severely deteriorated condition (see Architectural Heritage, no. 6).

The Emamzadeh Yahya is not published in the plate volume of the Denkmäler Persischer Baukunst, and it will take another decade for Sarre to publish on the shrine (jump ahead to 1910). In the meantime, the Emamzadeh Yahya’s luster mihrab will often be described as “from the mosque in Varamin,” perhaps misleading some to think it was from the city’s congregational mosque, which became better known (to some) due to Sarre’s publication.

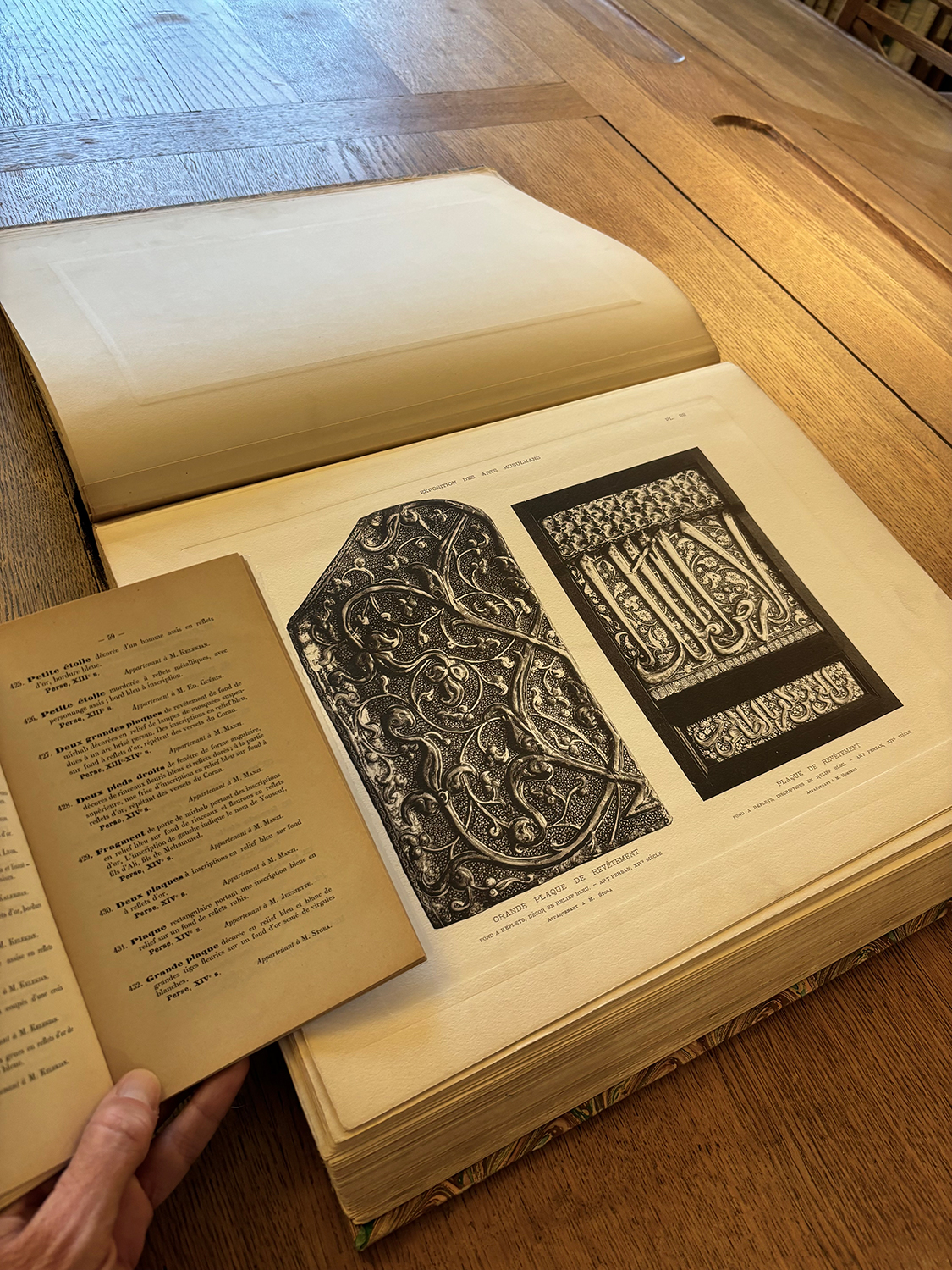

April–June 1903: Paris

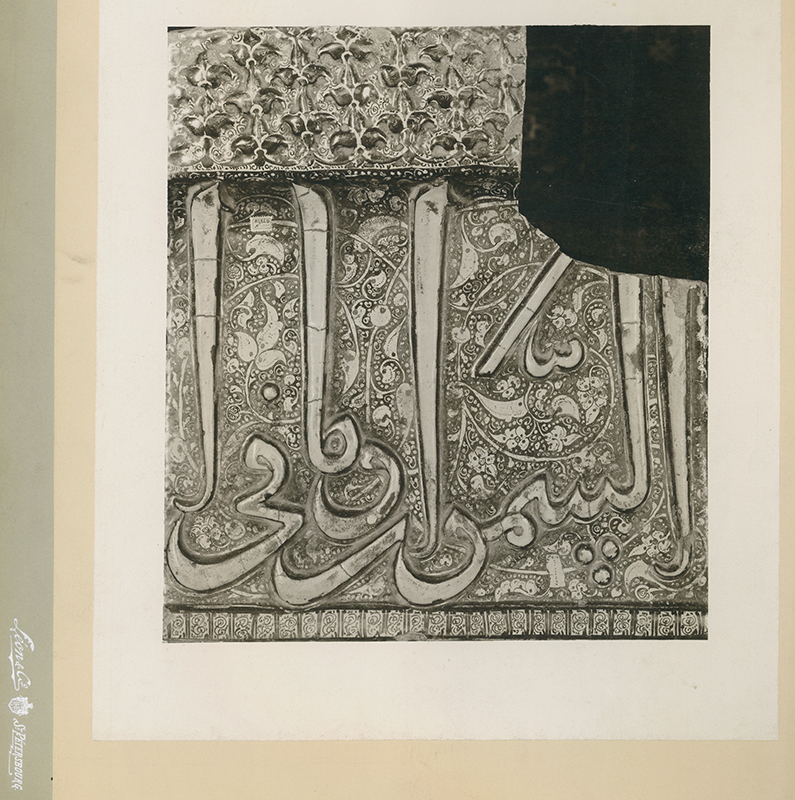

The mihrab’s border tile in Homberg’s possession is included in a deluxe publication reproducing the most important one hundred objects shown in the “Exposition des Arts Musulmans” (Exhibition of Muslim Art) at the Musée de Arts Décoratifs in May through June 1903 (fig. 55). The exhibition is held in the Marsan pavilion next to the Tuileries gardens and features over one thousand high-quality objects drawn from private collectors, all of whom are named on the opening pages of the much smaller handbook.76

The border tile is reproduced above another tile removed from the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab and in Homberg’s collection. This thin, rectangular tile inscribed with verses from sura al-Baqara (من الغی فمن یکفر بالطاغوت) was once part of the frame around the inner niche, like the smaller tile in Vienna by 1875 (for both in greater context, jump ahead to the Conclusion). Reproduced next to the two tiles from the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab is yet another tile taken from a dismantled luster mihrab: the left side of a central hood (arch). This “grande plaque” was in the possession of French dealer Maurice Stora and likely the large tile that he had acquired at the Qavam Daftar sale in 1900. The right side of this hood had been in the Musée National de Céramique de Sèvres since at least 1879.77

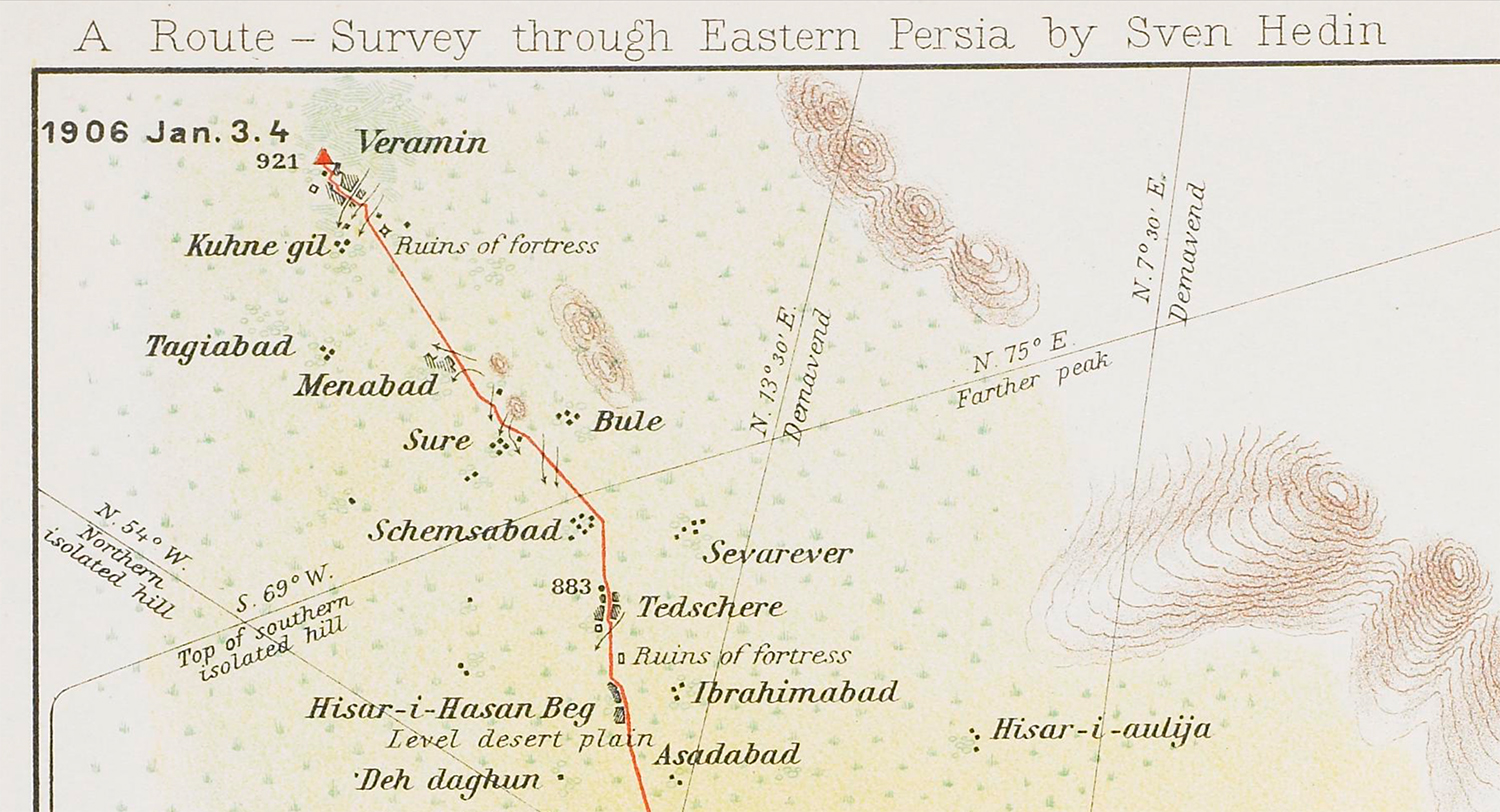

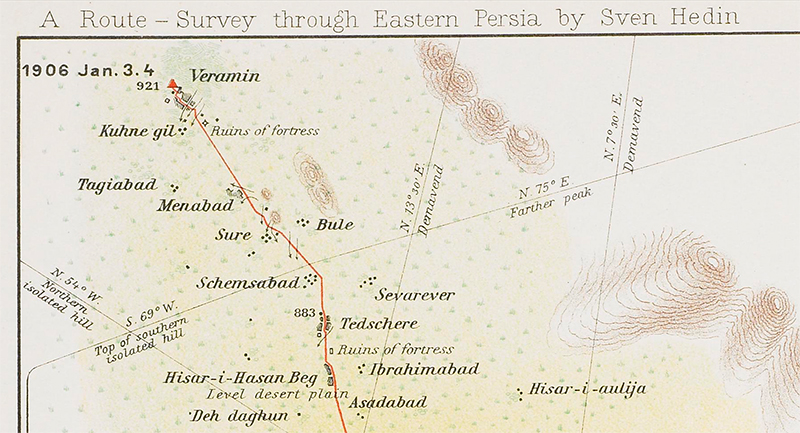

January 1906: Varamin

“Such plundering is a greater disgrace to the purchasers than stealing.”

Swedish geographer and explorer Sven Hedin (d. 1952) passes through Varamin during his third journey to map “Eastern Persia” and Tibet. On his map, he indicates “Kuhne gil” (Kohneh Gel) just south of “Veramin,” appropriately recording the former as its own distinct village (fig. 56). He also records some important points about the Emamzadeh Yahya: “In Kohne-gel, a village to the south, is Imamsadeh-Yahiya, a mosque mausoleum, from which a mushtehid [mojtahed] says that valuable tiles are stolen to be sold to Europeans in Tehran. Such plundering is a greater disgrace to the purchasers than stealing.”78

March 1906: Paris

Ottoman collector-dealer-author Hakky-Bey offers his collection for sale at Hôtel Drouot in Paris.79 This immense sale takes place over six days and includes over seven hundred lots. The first few days are devoted to ceramics, and the “faïences orientales” section includes fifty-one pieces (nos. 348–99), mostly luster tiles, or reflets métalliques. Their provenance is given as “Collection de professeur Richard, Exposition de 1889,” yet another allusion to Jules Richard’s esteemed collection (see also 1901: London). Some stars and crosses measuring 31 centimeters are likely from the Emamzadeh Yahya (for example, no. 356–57) and visible in the back of a photograph of Hakky-Bey’s collection reproduced in the catalogue (fig. 57).80

1907: Iran

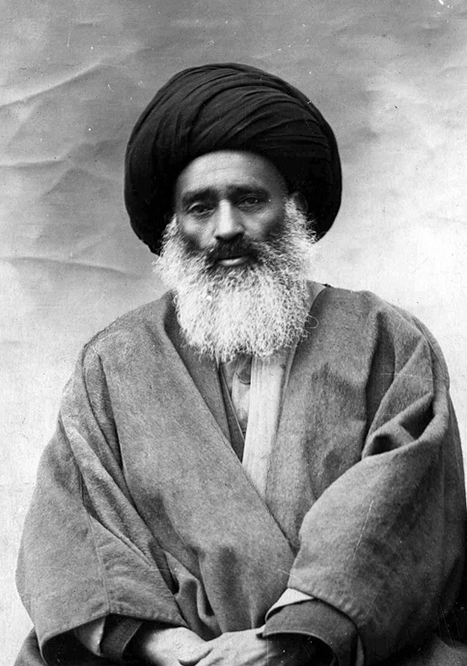

The death of Mozaffar al-Din Shah in 1907 appears to have had a major impact on the fate of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab. According to dealer Hagop Kevorkian, writing in 1913:

On the death of the Shah and the ultimate substitution of a constitutional regime, His Excellency Mostofy-ul-Memalik, having played an important role, was called to fill the post of Prime Minister at a most difficult moment, and the great Mushtahid (the religious authority) [mojtahed] who was the herald of the Constitution, in return for the services of Mostofy and his gifts of land which he bequeathed to the J[I]mamzades of Veramin, authorized him to dispose of the monument in question.81

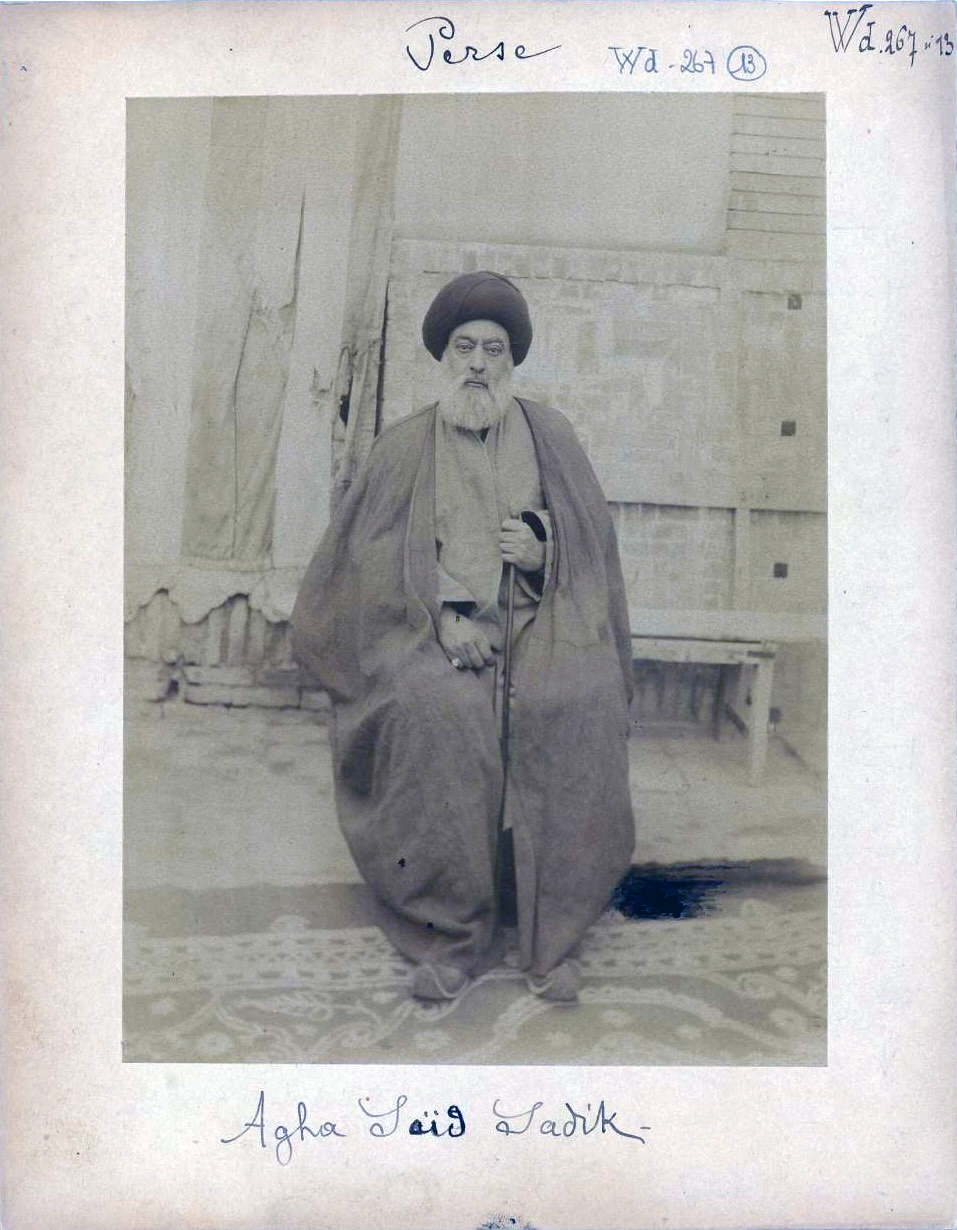

The Mowstofi al-Mamalek in question was Mirza Hasan Khan Ashtiani, who had been in Paris since 1900 and only returned to Iran after the death of Mozaffar al-Din Shah.82 The mojtahed in question could have been Seyyed Mohammad Tabataba’i (d. 1920), whose family was gifted land in Rey by Mirza Yusof Ashtiani Mowstofi al-Mamalek, the father of Mirza Hasan Khan, to build a tomb for his father in 1300/1882–83 (map) or Seyyed ʿAbdollah Behbahani (d. 1910) (figs. 58–59).83

1907: Paris

The fourth tile from the outer border of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab, which is still in Homberg’s collection, is reproduced for the third known time, in the second volume of a sizable manual on “art musulman” published by Gaston Migeon and Henri Saladin (fig. 60). The caption of the image makes no reference to the tile’s belonging to a larger ensemble (the mihrab) or to its original context (the Emamzadeh Yahya). The reproduction confirms that this single isolated tile had firmly entered the mainstream art historical narrative of so-called Islamic art.

A few pages later, a luster star from the tomb’s dado is also reproduced. This tile, along with four others, had entered the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (Museum of Art and Industry; map) in 1883 and been purchased in Esfahan from one Emmanuel Friedrich Adalbert du Vignau (d. 1901).84 If this provenance history is correct, it reveals that Esfahan was another place where the tomb’s tiles were sold (Tehran typically considered to be their main node of circulation in Iran).

1910–12: Berlin and Munich

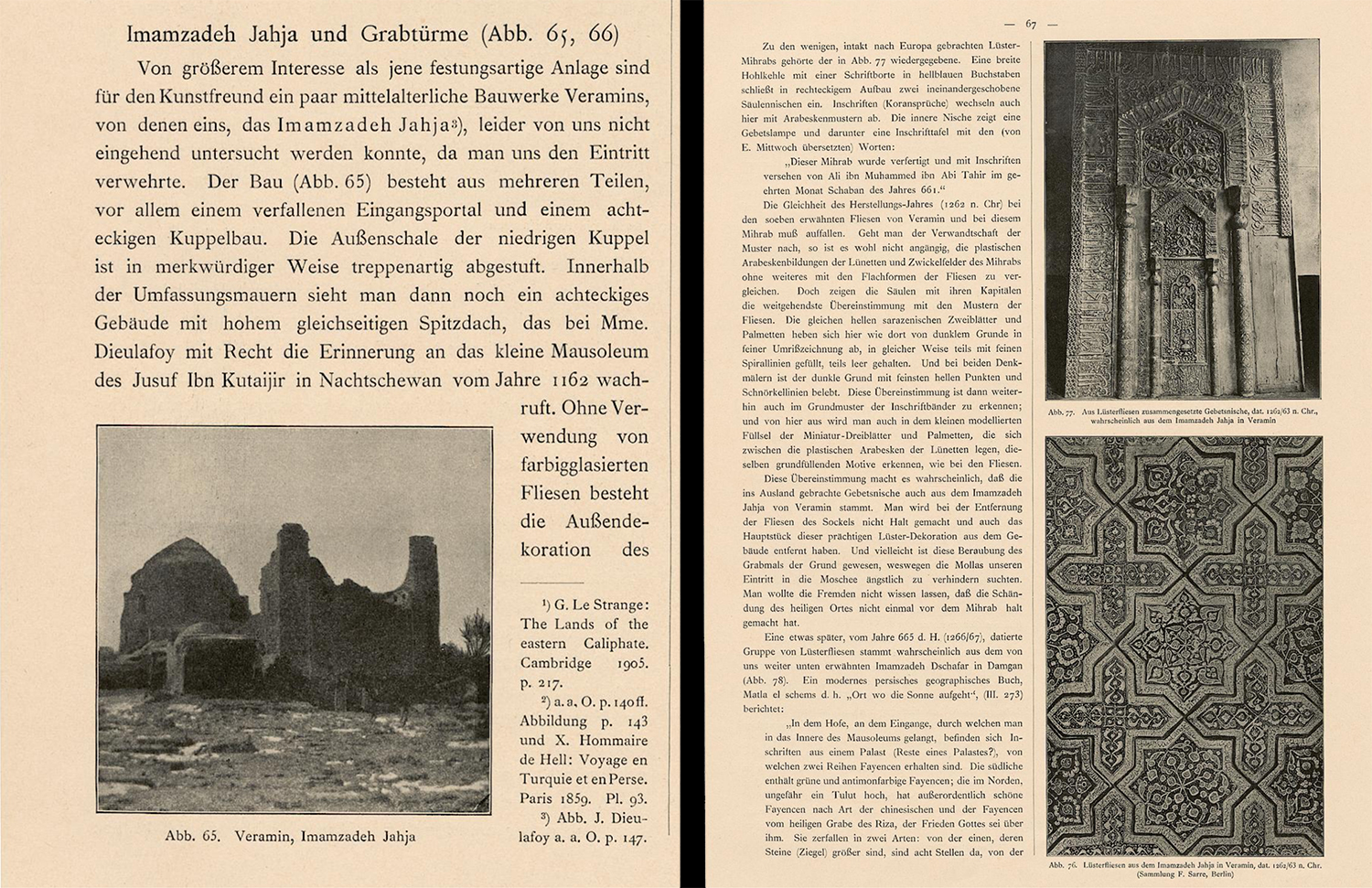

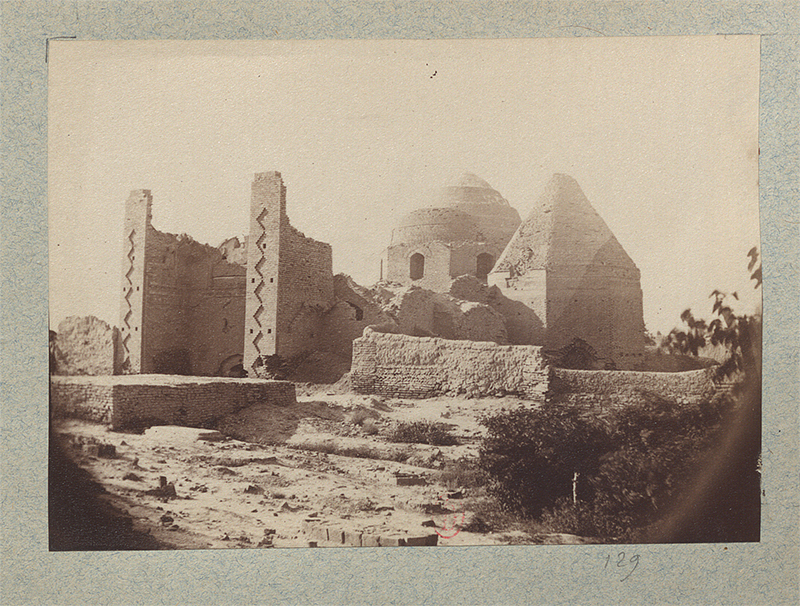

Thirteen years after his first visit to Varamin in 1897 (he also visited in fall 1899), Friedrich Sarre publishes his long-awaited textband of Denkmäler Persischer Baukunst, including his discussion of the Emamzadeh Yahya. The reproduced view of the complex is much darker and blurrier than Dieulafoy’s 1881 photograph but shows additional features on the northeast (fig. 61; see also Digital Tools). The conical tower is just visible through the entrance portal, and the east side of the tomb is unobstructed. Sarre identifies the site as the “Imamzada Jahja” and uses the words “imamzada,” “heiligen Ortes” (sacred place), and “mosquée” interchangeably.

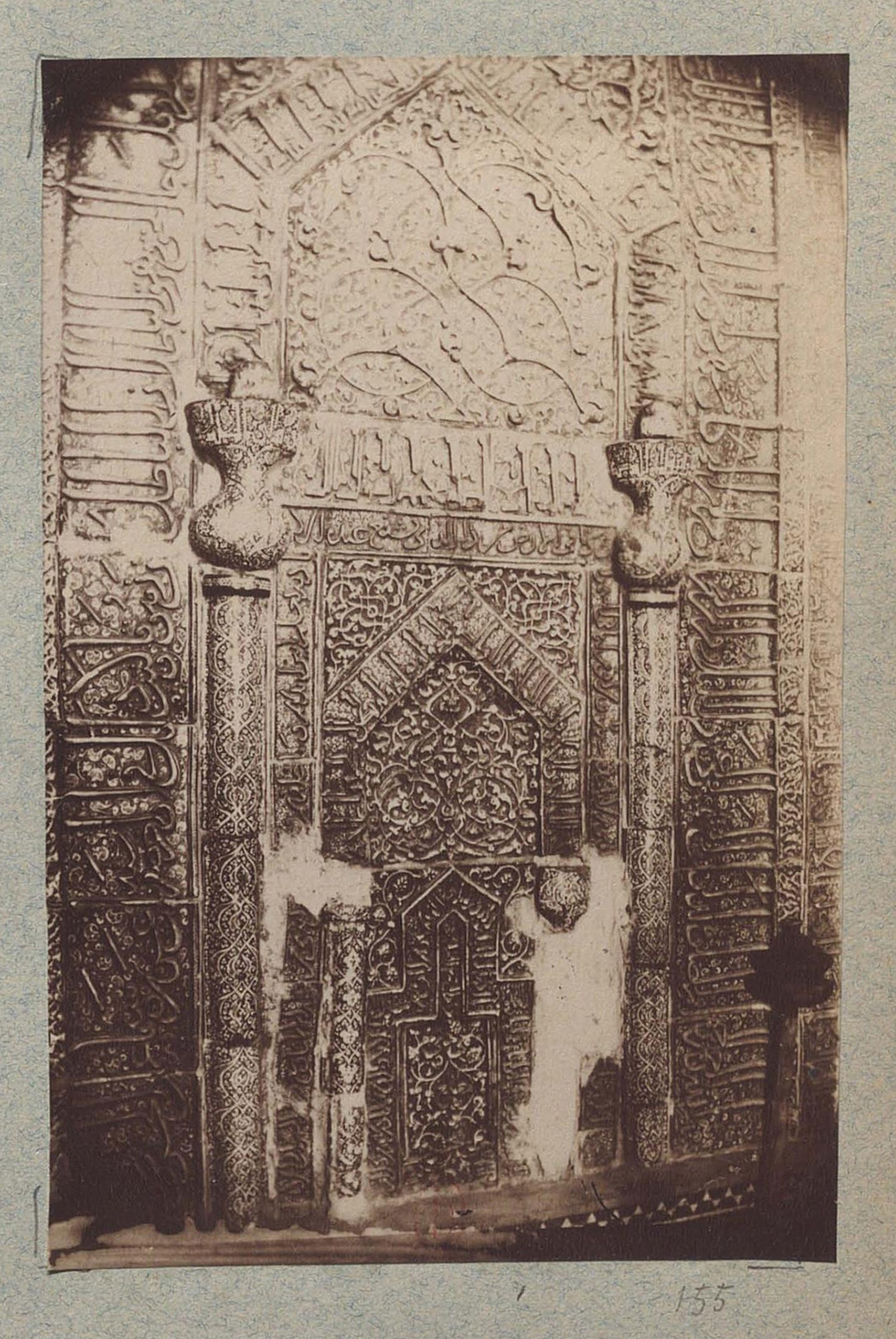

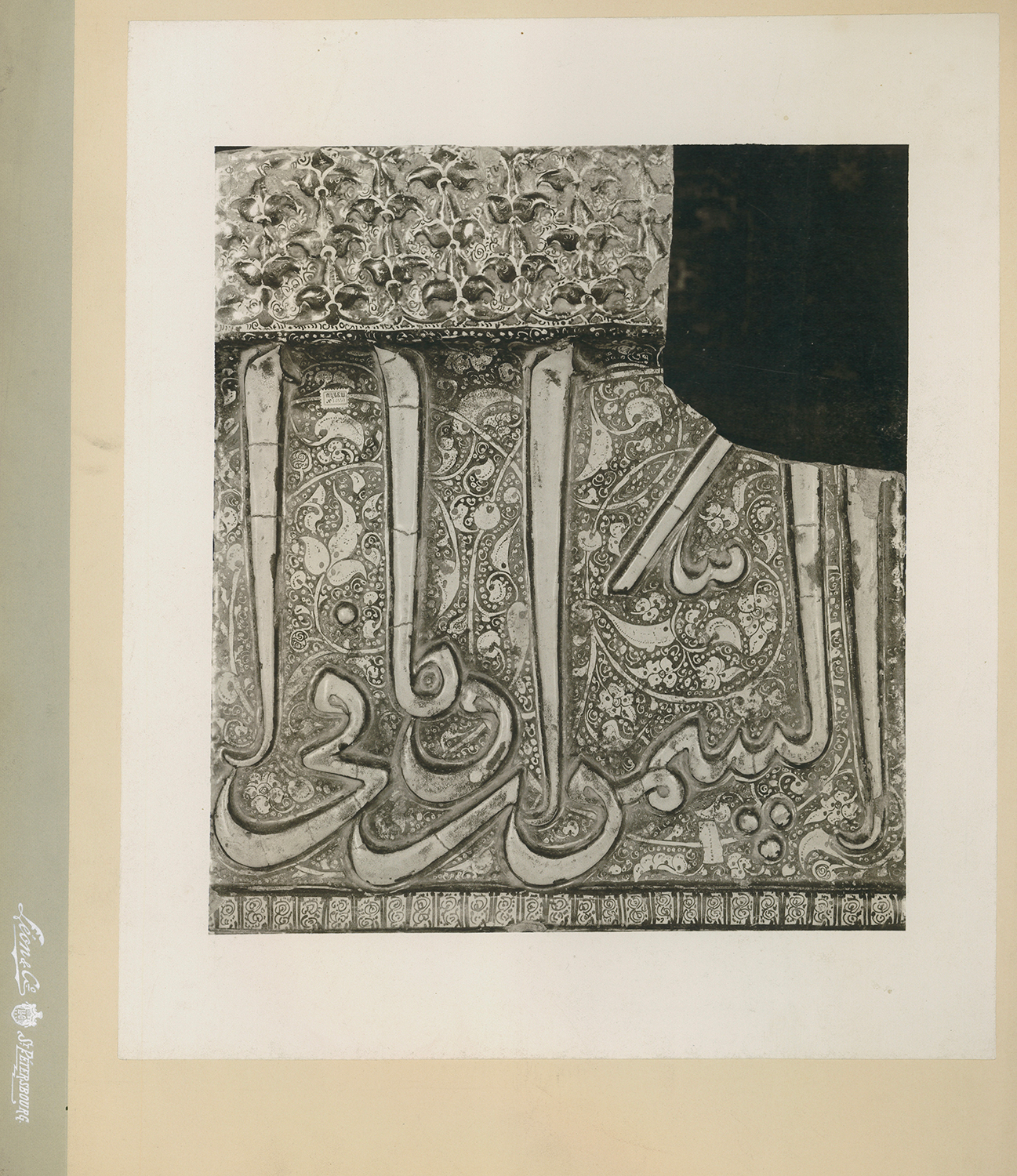

In his section on luster tilework, Sarre reproduces the mihrab for the first time in its displaced state (fig. 61). It is propped up against a plain wall and missing many tiles, including the border tiles from the lower right and the thinner rectangular tiles to the left and right of the inner niche (see 1875 and 1903). This band was once a continuous frame around the niche, and the removal of the upper horizonal row therefore resulted in the literal shrinking or shortening of the mihrab (fig. 62). According to the archives of the Museum of Islamic Art of Berlin, Sarre purchased this photograph from an amateur photographer, a reality confirmed by his later reference to this “mangelhaften amateur-photographie” (poor amateur photograph).85 It is possible that the photograph was taken in the boutique on the rue du 4 septembre, but we cannot be sure.

Below the mihrab in Denkmäler, Sarre reproduces a photograph of stars and crosses “aus dem Imamzadeh Jahya” (from the Emamzadeh Yahya) (see fig. 61). Based on formal similarities between the stars and crosses and the mihrab, Sarre attributes the latter to the Emamzadeh Yahya. He accurately gives the potter’s name but misreads the year as 661 (versus 663, ۶۶۳). Sarre acknowledges the tomb’s “Beraubung” (robbery) and suggests that this was why he was prohibited from entering the site: “Man wollte die Fremden nicht wissen lassen, daß die Schän dung des heiligen Ortes nicht einmal vor dem Mihrab halt gemacht hat” ([The mollahs] did not want to let strangers know that the desecration of the holy place did not even stop at the mihrab) (see fig. 61). While Sarre did much to advance understanding of the tomb and acknowledged its plunder, he also can be argued to have perpetuated the latter. The stars and tiles that he reproduced in Denkmäler were in his collection, had been displayed in 1899, and only later entered the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (State Museum of Berlin). At the time, it was not uncommon for scholars to double as collectors and even dealers.

In the summer of 1910, Sarre also curates the Ausstellung von Meisterwerken muhammedanischer Kunst (Exhibition of Masterpieces of Muhammedan Art) in Munich, the largest exhibition of Islamic art of the time. This seminal event includes over 3,500 artworks from 250 lenders and a hall devoted to commercial collections of Islamic art.86 One represented dealer is Armenian Hagop Kevorkian (d. 1962), who shows about forty things and is identified in the catalog as “Galerie d’Art Musulman (H. Kevorkien)” on the rue de Rivoli in Paris. One of his most important possessions at the time is a luster tombstone panel naming Khadijeh Khatun (a daughter of Emam Jaʿfar), dated 713/1313, and originally cladding the upper surface of her cenotaph, hence like a ‘cover.’ This tombstone panel (or cenotaph cover) is displayed in a section that attempts to trace the development of luster tilework and which also includes a panel of star and cross tiles from the Emamzadeh Yahya in Sarre’s collection (no. 1282), likely the one he showed in 1899 and reproduced in Denkmäler.

In his introduction to ceramics in the three-volume compendium to the Munich exhibition published two years later (1912), Sarre describes the tombstone panel of Khadijeh Khatun as “der fast vollständig erhaltene Lüstermihrab aus der Sammlung Kevorkian” (an almost completely preserved luster mihrab in the Kevorkian collection) and “von einem Grabmal in Kum in Persien” (from a tomb in Qom in Iran). This description not only magnifies the name of the dealer but also misidentifies the panel as a mihrab. It is unclear if Sarre read the panel’s inscriptions, and as we shall see, confusions between tombstone panels/cenotaph covers and mihrabs would persist.

Regarding luster mihrabs, Sarre concludes: “Die Kostbarkeit dieser Fliesen hat es mit sich gebracht, daß wohl die meisten Lüstermihrabs zerstört und, leider zumeist in einzelnen Stücken, ins Ausland verkauft worden sind” (Due to the great value of these tiles, most luster mihrabs were destroyed and, unfortunately, often sold abroad in fragments). Some luster mihrabs were ‘destroyed’ in the sense of being disassembled into parts and sold as individual units or tiles, including one reproduced in the 1912 publication (fig. 63). Others, like the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab, were exported abroad but kept relatively intact, as seen in Sarre’s own Denkmäler. It is difficult to say how many luster mihrabs were completely ‘destroyed’ in the sense of a total loss, and Sarre’s synopsis neglects to account for those in situ in Iran at the time, for example, in the Shrine of Emam Reza in Mashhad and Emamzadeh ʿAli b. Jaʿfar in Qom (jump ahead to 1931).

1911: Paris

French traveler and collector Henry-René d’Allemagne (d. 1950) includes a section called “Histoire du mihrab de Véramine” in his four-volume travelogue Du Khorassan au Pays des Backhtiaris, which doubles as a sales catalogue for some materials (figs. 64–65). He had visited Varamin in 1907 and describes it as a “verte oasis” (green oasis) populated with many birds and animals.87 It is unclear if he visited any monuments, but he certainly knew of the congregational mosque. In the preface to volume one, he reproduces Jules Laurens’s drawing of the upper half of the stucco mihrab in the congregational mosque, incorrectly captioning it as the “porte de la mosquée de Véramine” (gate of the mosque of Varamin).

In his section on the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab, d’Allemagne describes how, as a result of a somewhat shady arrangement, one of Mozaffar al-Din’s ministers had brought the mihrab, hidden in the shah’s luggage, to Paris at the end of the nineteenth century. No one was able to buy it, and it was repacked and stored in a stable in the Marbeuf quarter (map). Allemagne also mentions the mihrab's display in Paris for several months in a boutique (see 1900) and how "all the amateurs of Oriental art in Paris went on pilgrimage [to see it]." He hopes that it will enter a French museum:

Il serait à souhaiter que ces curieux spécimens de l’art persan entrassent dans un de nos musées, car, même dans les plus belles mosquées, de l’Iran, il ne subsiste plus d’ensemble aussi considérable dans un état de conservation pareil.88

It would be wonderful if these curious specimens of Persian art would enter one of our museums, for even in the most beautiful mosques of Iran, there is no longer any such considerable ensemble in such a state of preservation.

Although d’Allemagne does not name the minister who brought the mihrab to Paris, it was Mirza Hasan Khan Mostowfi al-Mamalek, in concert with his travel companions (see 1900).

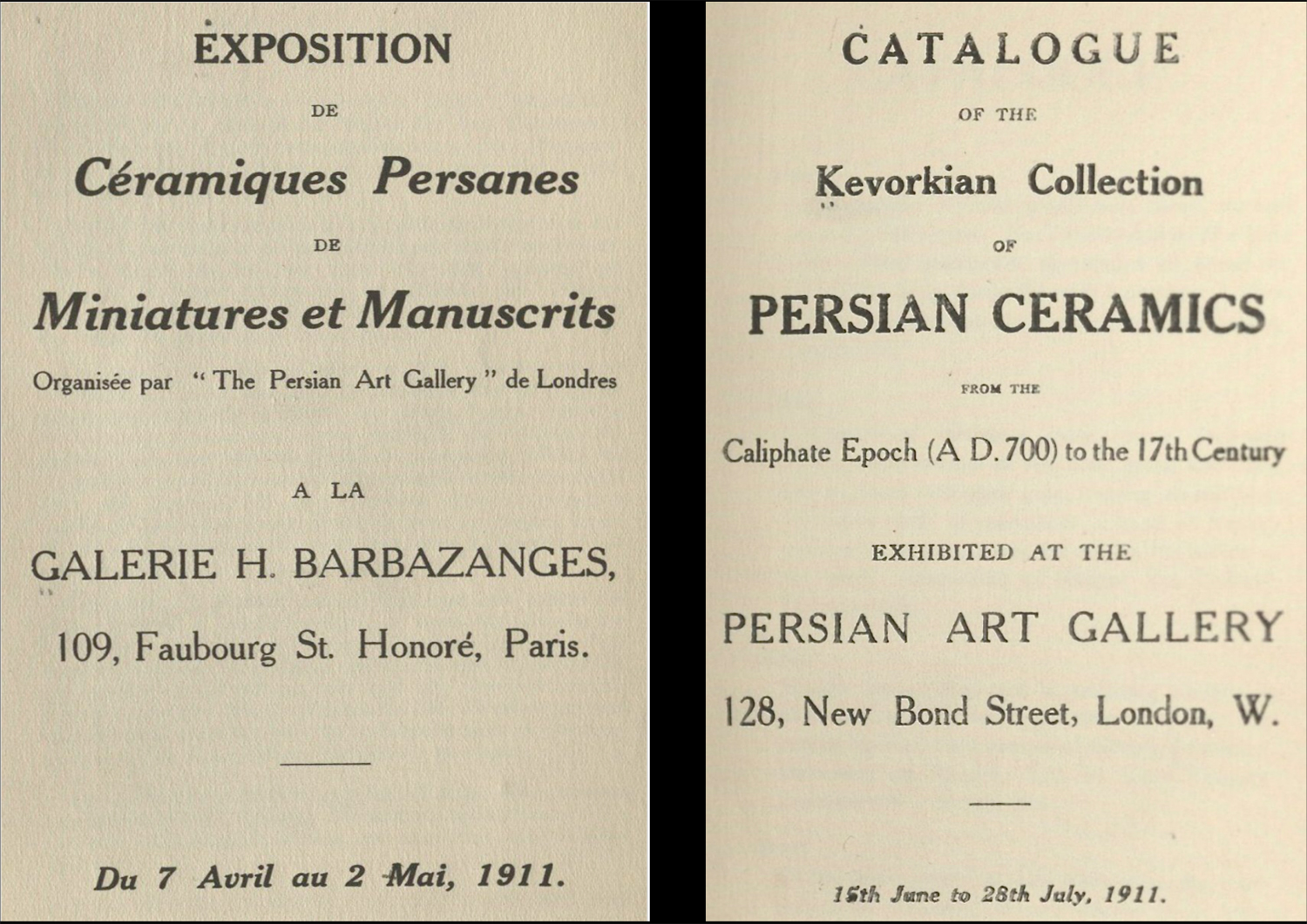

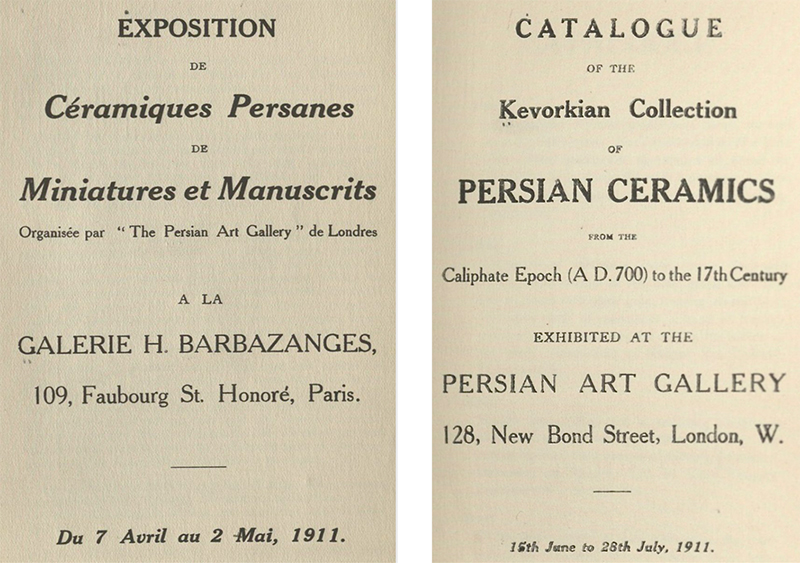

1911: Paris and London

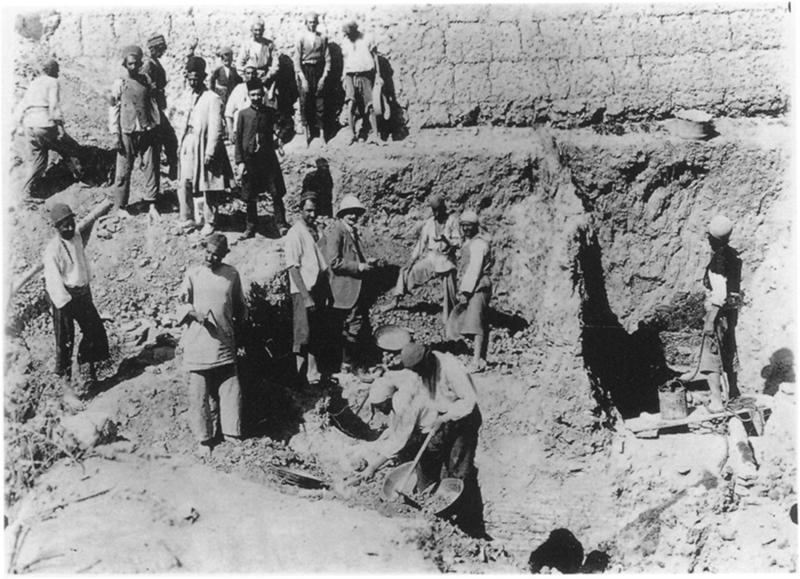

Dealer Hagop Kevorkian (d. 1962) organizes three exhibitions largely inspired by his recent excavations in Iran and ‘finds’ of ceramics and tiles (fig. 67). The first take place at Galerie H. Barbazanges at 109, rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré in Paris (map), the second at his own Persian Art Gallery at 128, New Bond Street in London (map), and the third again in Paris (fig. 68).89 The first exhibition includes over three hundred works of art divided almost equally between ceramics and manuscripts. The introduction of the catalogue comments on how “chercheurs infatigables” (inexhaustible researchers), “amateurs” (amateurs), and “pionniers” (pioneers) had been scouring the desert of central Iran, new treasures were emerging, and cities like Rhages (Rey), Hamadan, and Sultanabad were supposedly being revived as a result.90

The commercial digs led by Kevorkian and other European and Iranian dealers are criticized by some archaeologists and art historians of the time.91 Concurrent to Kevorkian’s first exhibition in Paris, French archaeologist and architect Henry Viollet (d. 1955) writes a letter to a French official emphasizing that Jacques de Morgan’s focus on Susa is resulting in neglect and pillaging elsewhere in the country, citing Kevorkian’s show as an example:

…laisse malheuresement de côté tout le rest qui est mis au pillage par les populations soudouyées par des agents étrangers, je n’en veux pour prevue que l’exposition actuellement ouverte Faubourg St Honoré de céramiques et miniatures persans en provenance de The Persian Art Gallery.

…unfortunately, leaving out all the rest [other archaeological sites], which is being pillaged by populations bribed by foreign agents. As evidence, I only have to point to the current exhibition on the rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré of Persian ceramics and miniatures from The Persian Art Gallery.92

In his Denkmäler Persischer Baukunst of a year earlier (1910), Sarre had said of Rey:

Die Schätzung, die diese Rhages-Ware in den letzten Jahren auf dem Kunstmarkt gewonnen hat, brachte es mit sich, daß jetzt der Boden der ehem’Alī gen Stadt darnach durchwühlt wird. Es ist zu hoffen, daß eine systematisch vorgenommene Untersuchung des Ruinenfeldes in nicht allzu langer Zeit diesem Raubwesen ein Ende macht.93

The esteem that this Rhages [Rey] ware has gained on the art market in recent years has meant that the soil of the former city is now being dug up for it. It is hoped that a systematic investigation of the ruins will soon put an end to this predatory activity.

Sarre’s critique invites reflection, because he was also collecting and displaying some dubious materials, including tiles from sacred sites like the Emamzadeh Yahya (see 1899).

In addition to excavated ceramics, Kevorkian’s exhibitions also include architectural tiles from sacred sites. In the first exhibition in Paris, a large tile dated 722/1322 is said to be a tomb ornament (“objet d’ornamentation de tombeau”).94 In the second exhibition in London, which focuses on 120 examples of Persian ceramics, it is described as a “mihrab tile” “discovered at Koum (the place where Persian rulers were buried).”95 The tile in question was the hood of an underglaze mihrab, raising many questions about its removal and export and the rest of the ensemble.96 The third exhibition also includes the tombstone panel from Khadijeh Khatun’s cenotaph (see 1910–12), and its comparatively long catalogue entry describes it as “trouvée à Koum” (found at Qom) and provides a French translation of its inscriptions, with the date incorrectly noted as 703 AH (vid. 5).97 The fate of this tombstone panel would soon intertwine with the Emamzadeh Yahya’s mihrab.98

Video 5. Turning the pages of Catalogue d’Exposition d’Art Musulman, Kevorkian’s third exhibition in 1911, held at the Galeries Henry Barbazanges in Paris from 3 November to 3 December. The video focuses on entry no. 50 devoted to the “pierre tombale” (tombstone panel). Video by Keelan Overton, 2024, of the copy in INHA, Paris.

1912: New York

Building on the momentum of his exhibitions in Paris and London, Kevorkian organizes an “Exhibition of Mohammedan Art” (17 January to 10 February) at the Folsom Galleries in New York in midtown Manhattan (map). The title page of the catalogue emphasizes that the exhibition comprises “a collection of early objects excavated under the supervision of H. Kevorkian.” In the introduction, Kevorkian notes that the exhibition mainly focuses on Persian materials unearthed during his recent digs:

The main interest of this exhibition, however, lies in the collection discovered in Central Persia; discoveries that brought to light a wealth of immense artistic significance and beauty, that taught us the lesson that we must look in the soil of Persia for the masterpieces of early Mohammedan art.99

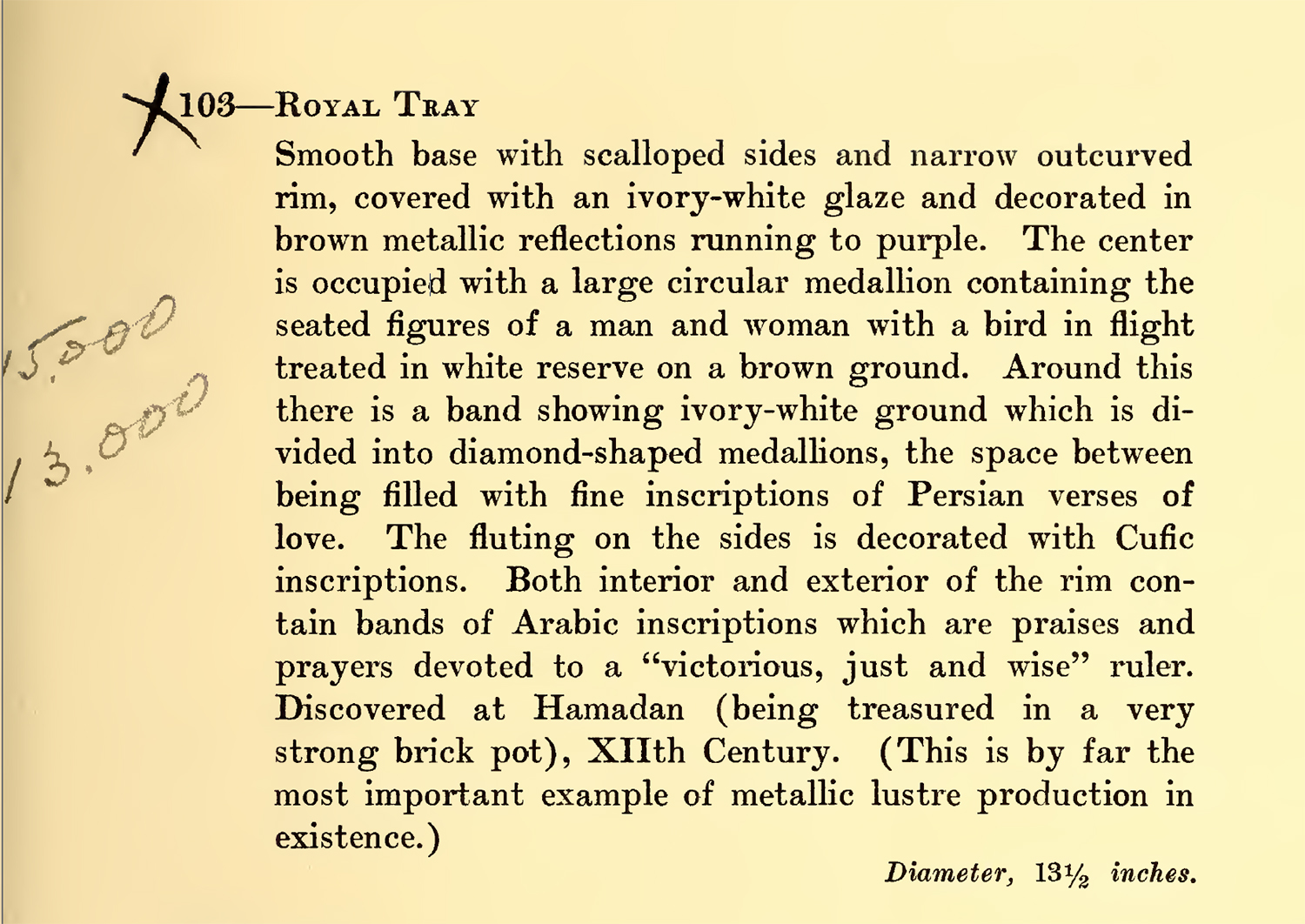

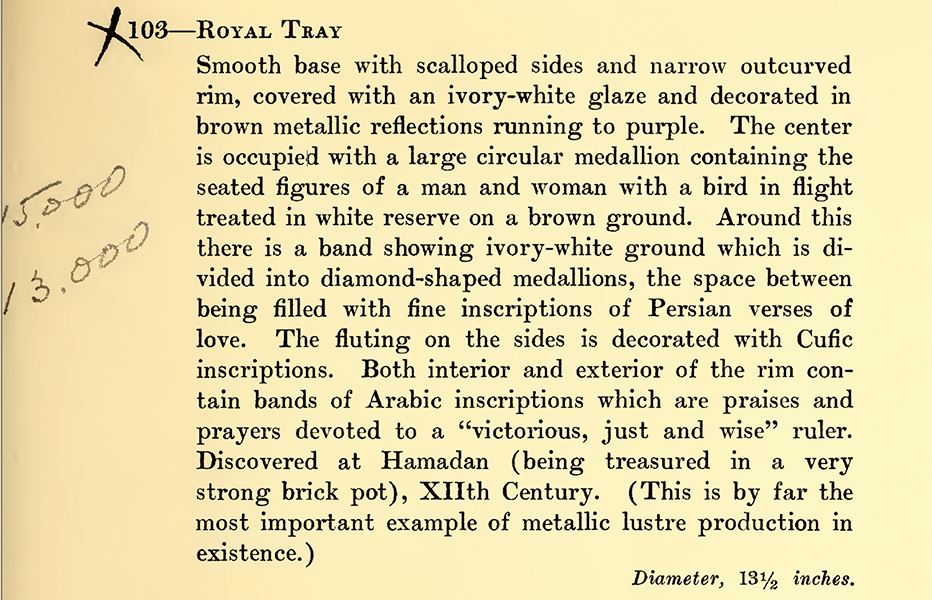

The New York exhibition-sale includes 288 lots, the first 123 of which are ceramic objects or tiles. One of the finest ceramic vessels is a “royal tray” said to be found in a brick pot in Hamadan and described by Kevorkian as “by far the most important example of metallic lustre production in existence” (fig. 69). Soon after the exhibition, American collector Isabella Stewart Gardner (d. 1924) purchases the dish for $10,000 (fig. 70).

Kevorkian continues to try to sell some of the luster tiles included in his 1911 exhibitions, including the three-tiled tombstone panel belonging to the cenotaph of Khadijeh Khatun (“one of the most important documents of early Islamic art in existence”) and the underglaze hood of a mihrab (“niche or mihrab tile”).100 The New York sale also includes a wooden door dated Ramadan 1000/June 1592, “in [a] perfect state of preservation,” and from the emamzadeh of one Qasem, son of Emam Musa.101 This door underscores an important point: luster tiles were not the only architectural elements being taken from Iranian shrines and sold in New York. Such was also the fate of the Emamzadeh Yahya’s Safavid-period wooden door, which was in place in 1863 and for sale in New York by 1915 (Checklist, no. 15).

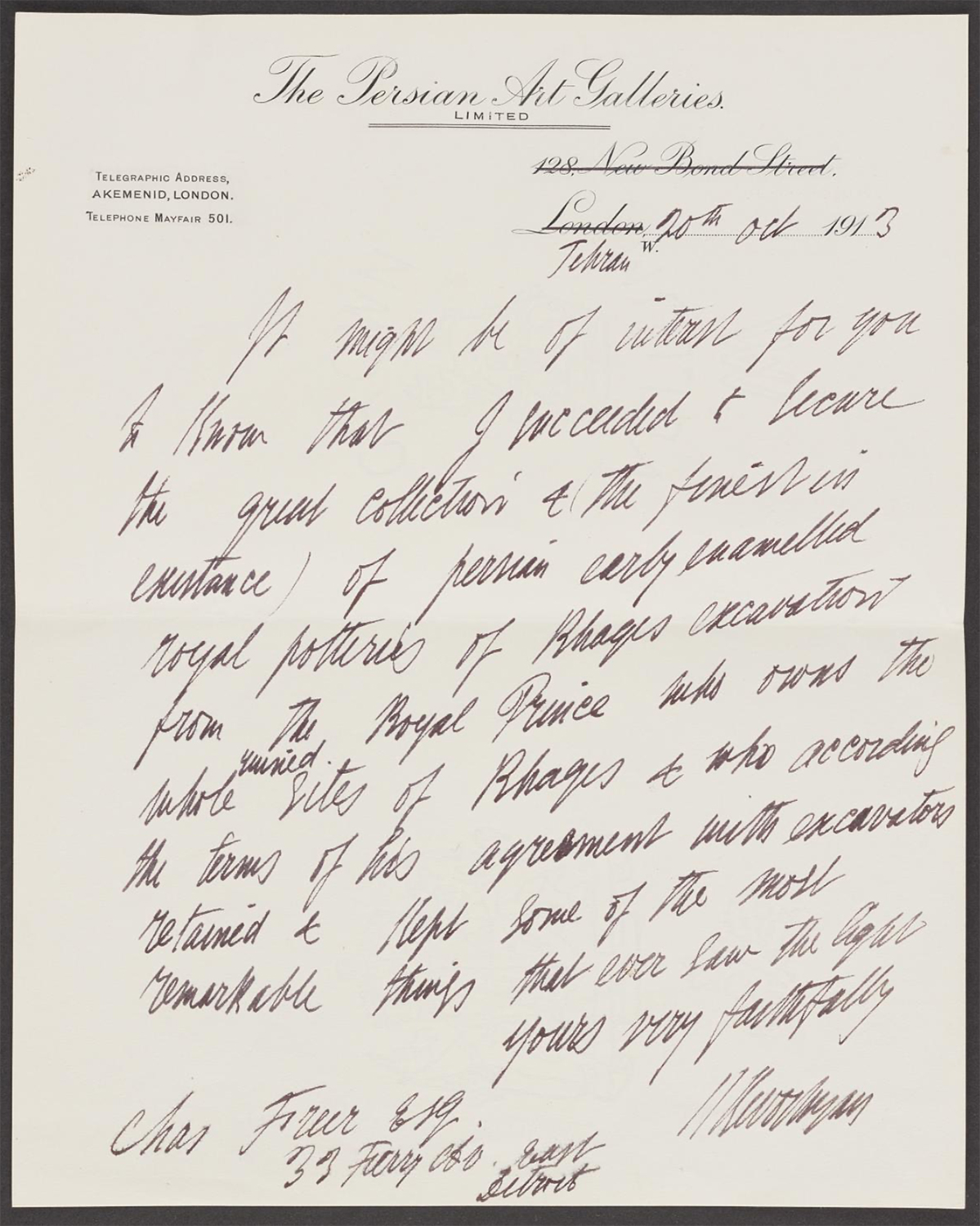

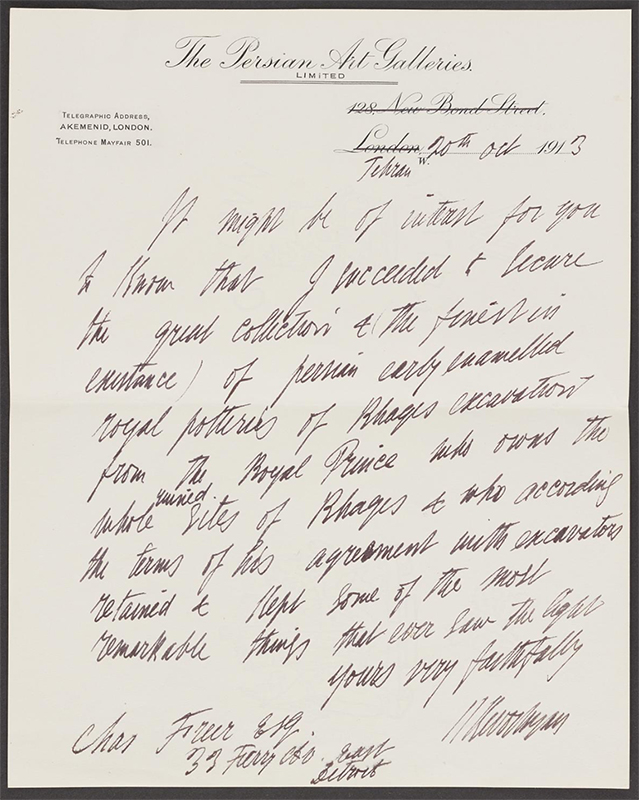

Kevorkian’s digging in Iran pre-dated scientific archaeology and raises questions about how cultural materials were extracted and exported and with whose approval and for whose benefit. In a letter written to American industrialist-collector Charles Lang Freer (d. 1919), to whom we will return in chapter 2, Kevorkian provides a sense of his networks and points of access (fig. 71):

It might be of interest for you to know that I succeeded to secure the great collection & (the finest in existence) of Persian early enamelled royal potteries of Rhages [Rey] excavations, from the royal prince who owns the whole ruined sites of Rhages & who according to the terms of his agreement with excavators retained & kept some of the most remarkable things that ever saw the light.

Kevorkian’s operations were not unique and occurred during a wave of unregulated excavation during France’s monopoly on archaeology issued by Mozaffar al-Din Shah in Paris in 1900.102 This monopoly was canceled in 1927 and followed by the ratification of the Antiquities Law (Qanun-e ʿAtiqat, قانون عتیقات). In 1931, the first scientific excavations took place at sites like Tapeh Hesar (under Erich F. Schmidt, d. 1964) and Persepolis (under Ernst Herzfeld, d. 1948). Some of these excavations were sponsored by American museums and universities, including the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, Penn Museum, and Metropolitan Museum of Art.103 The result, however regulated and scientific, still resulted in a substantial amount of Iran’s cultural heritage being exported to western museums.

Notes

- Naser al-Din Shah, Gozāresh-e shekārhā-ye Nāser al-Dīn Shāh-e Qājār, 137–39. ↩

- Special-Catalog der Ausstellung des Persischen Reiches, 147. ↩

- See the categories of “goods” in the contents (Inhalt) of the Special-Catalog der Ausstellung des Persischen Reiches, as well as Naser al-Din Shah, Rūznāme-ye khāṭerāt-e Naṣer al-Dīn Shāh dar safar-e avval-e farangestān, 299. For a plan of the exhibition published by Eduard Hallberger, see the Wien Museum, Vienna, 9581. ↩

- Mirza Hasan Tabrizi, “Akhbār-e khārejeh-ye qeyr-e rasmī,” 3; Mirza Hasan Tabrizi, “Akhbār-e mokhtalefeh,” 4. Thank you to Maryam Heydarkhani for bringing our attention to these newspaper articles. Her forthcoming article, entitled “Mirroring Persia’s Aura in the Vienna World’s Fair: Tracing Mediators, Planners and Architectural Features,” will discuss these sources in the broader context of the 1873 exhibition. We are grateful to Sina Soltani for his help in understanding the nuances of the text. ↩

- Special-Catalog der Ausstellung des Persischen Reiches, 145–46; Pokorny-Nagel, “Vieles ist erreicht aber noch mehr ist zu thun übrig,” 191–93; Fulco, “Displays of Islamic Art in Vienna and Paris,” 58. ↩

- Naser al-Din Shah, Rūznāme-ye khāṭerāt-e Naṣer al-Dīn Shāh dar safar-e avval-e farangestān, 299. ↩

- On Prince Urusov, see “Wien, 7. Juni,” 7 and “Nichtamtlicher Theil. Parlamentarisches,” 1. This acquisition is recorded in two reports: MAK Aktenarchiv MAK Archives Zl. 1875-235 and 1887-734. Thank you to MAK archivist Walther Merk for providing this information. ↩

- For some analyses of Murdoch Smith’s early acquisitions, see Helfgott, Ties that Bind, 125–43 (an assessment that was in some respects ahead of its time) and Carey, Persian Art, 87–119. ↩

- For some readings on Richard, see Mahdavi, “Rishār Khan;” Carey, Persian Art, 100–14; and Tahmasbpour, Nāṣer al-Dīn, shah-e akkās, 220–33. Figure 15 here is among the most plausible portraits of Jules Richard. For further discussion of portraits of him and photographs by him, see Luster Cabinet. ↩

- Report from Murdoch Smith to Cunliffe-Owen, no. 10, 1 February 1875, 2, V&A Museum Archive, MA/1/S2325. ↩

- Report no. 15 from Murdoch Smith to Cunliffe-Owen, 10 May 1875, 1, V&A Archive, MA/1/S2325. ↩

- Report no. 16 from Murdoch Smith to Cunliffe-Owen, 1 June 1875, 12–13, V&A Archive, MA/1/S2325. ↩

- Report no. 17 from Murdoch Smith to Cunliffe-Owen, 10 June 1875, V&A Archive, MA/1/S2325. ↩

- Report no. 26 from Murdoch Smith to Cunliffe-Owen, 28 December 1875, 3–4, V&A Archive, MA/1/S2325. Italics added. ↩

- Report no. 22 from Murdoch Smith to Cunliffe-Owen, 1 September 1875, 6–7, section 7, V&A Archive, MA/1/S2325. ↩

- Report no. 24 from Murdoch Smith to Cunliffe-Owen, 1 November 1875, 1–2, section 2, V&A Archive, MA/1/S2325. The tiles in question are V&A 1821A,B-1876, naming Hosayn b. Zayn al-ʿEbad ʿAli. For further discussion and images, see Carey, Persian Art, 102–5. ↩

- Report no. 24, 5–6, section 4. ↩

- Report no. 24, 7–8, section 7. ↩

- Report no. 24, 8–10, section 8. ↩

- “Fine Arts. Persian Art at South Kensington,” The Illustrated London News, 15 April 1876, 382. ↩

- Smith, Persian Art, frontmatter. ↩

- The government’s order has not yet been located, and our knowledge of it rests solely on Smith’s report, which is also analyzed in Helfgott, Ties That Bind, 130, and Carey, Persian Art, 105. It might be related to the “common law” described by Dieulafoy (jump ahead to 1881), which she describes as prohibiting Christians from entering religious sites. ↩

- “The Museum’s copious acquisitions of thirteenth- to fourteenth-century lustre tiles may have generated further demand (and even higher market prices) among wealthy art collectors, encouraged to follow the ostentatious example set in South Kensington’s Persian Court.” Carey, Persian Art, 114. ↩

- Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, Rasāʾel, 207. This is a 2012 compilation of some of Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh’s writings, including the Iran article in question. ↩

- Eʿtemad al-Saltaneh, Rasāʾel, 208. ↩

- For the biography’s dated colophon, see Nakhaei and Overton, “The Emamzadeh Yahya Through the Eyes of ʿAliqoli Mirza Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh,” slide 5. ↩

- Nakhaei and Overton, “The Emamzadeh Yahya Through the Eyes of ʿAliqoli Mirza Eʿtezad al-Saltaneh,” slide 3. ↩

- 7826, “Note de Mr. Bernay,” inventory book, fol. 60r–v, Musée national de Céramique at Sèvres. ↩

- Bernay lived in Iran for about thirty years, from 1863 to the end of the 1890s, and was posted for periods in Tabriz and Shiraz. In 1874, he sent a shipment of over three thousand luster tiles and fragments from Tehran to Paris, and in 1876, he began working for Sèvres. On 28 December 1885, Bernay was awarded the Legion of Honor. Thank you to Sèvres curator Delphine Miroudot for sharing information. See also Carey, Persian Art, 98–99. ↩

- Overton, “Jane Dieulafoy in Varamin.” After their first trip, which concluded with a quick visit to Susa, the Dieulafoys requested official permission to excavate Susa. Naser al-Din Shah granted permission in 1884, and the excavations unfolded over two seasons in 1885–86. The French ultimately violated the terms of the agreement, illegally taking most of the finds to Paris. See Nasiri-Moghaddam, “The First British and French Archaeological Investigations in Susa.” ↩

- Dieulafoy, “La Perse,” 74. ↩

- Dieulafoy, “La Perse,” 75. ↩

- Gadoin, Private Collections of Islamic Art, 80–81. For additional information on the club, see Pierson, Private Collecting, Exhibitions, and the Shaping of Art History. ↩

- Burlington Fine Arts Club, Illustrated Catalogue of Specimens of Persian and Arab Art, no. 32–34. One of the tiles (no. 33) is singled out for its date of Moharram 661/November 1262. In 1983, these tiles entered the British Museum: G. 454, G.455, and G.463. ↩

- Burlington Fine Arts Club, Illustrated Catalogue of Specimens of Persian and Arab Art, x. ↩

- Dieulafoy, La Perse, 149. Italics added. ↩

- Thank you to Mio Wakita, curator and head of the Asian collection at the MAK, for sharing this information. ↩

- Since the exhibition catalogue does not provide images or dimensions for the tiles, we cannot identify them with certainty. However, there is one luster star tile (no. 2379) with a floral pattern and an Arabic inscription dated 660/1262 that might correspond to one of the tiles. There are also other luster tiles listed that may or may not match the tiles from the Emamzadeh Yahya (see nos. 2380–2385). Orientalischen Museums, Katalog der Orientalisch-Keramischen Austellung, p. 182 in the digitization on HathiTrust. ↩

- The tile was displayed in the 1970s. See Österreichisches Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Kunst Des Islam, no. 99. ↩

- Lemaire served as the head of the court musicians in Tehran and taught at the Dar al-Fonun. In the 1880s, he commissioned tilework from ʿAli Mohammad Esfahani, including a fireplace surround dated 1302/1884–85 that was acquired by South Kensington (V&A, 510-1889). See Reiche and Voigt, “Technology of Production,” 506. ↩

- Carey, Persian Art, 168. ↩